Summary

Background

Results of small trials indicate that fluoxetine might improve functional outcomes after stroke. The FOCUS trial aimed to provide a precise estimate of these effects.

Methods

FOCUS was a pragmatic, multicentre, parallel group, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial done at 103 hospitals in the UK. Patients were eligible if they were aged 18 years or older, had a clinical stroke diagnosis, were enrolled and randomly assigned between 2 days and 15 days after onset, and had focal neurological deficits. Patients were randomly allocated fluoxetine 20 mg or matching placebo orally once daily for 6 months via a web-based system by use of a minimisation algorithm. The primary outcome was functional status, measured with the modified Rankin Scale (mRS), at 6 months. Patients, carers, health-care staff, and the trial team were masked to treatment allocation. Functional status was assessed at 6 months and 12 months after randomisation. Patients were analysed according to their treatment allocation. This trial is registered with the ISRCTN registry, number ISRCTN83290762.

Findings

Between Sept 10, 2012, and March 31, 2017, 3127 patients were recruited. 1564 patients were allocated fluoxetine and 1563 allocated placebo. mRS data at 6 months were available for 1553 (99·3%) patients in each treatment group. The distribution across mRS categories at 6 months was similar in the fluoxetine and placebo groups (common odds ratio adjusted for minimisation variables 0·951 [95% CI 0·839–1·079]; p=0·439). Patients allocated fluoxetine were less likely than those allocated placebo to develop new depression by 6 months (210 [13·43%] patients vs 269 [17·21%]; difference 3·78% [95% CI 1·26–6·30]; p=0·0033), but they had more bone fractures (45 [2·88%] vs 23 [1·47%]; difference 1·41% [95% CI 0·38–2·43]; p=0·0070). There were no significant differences in any other event at 6 or 12 months.

Interpretation

Fluoxetine 20 mg given daily for 6 months after acute stroke does not seem to improve functional outcomes. Although the treatment reduced the occurrence of depression, it increased the frequency of bone fractures. These results do not support the routine use of fluoxetine either for the prevention of post-stroke depression or to promote recovery of function.

Funding

UK Stroke Association and NIHR Health Technology Assessment Programme.

Introduction

Each year, stroke affects around 9 million people worldwide for the first time and results in long-term disability for around 6·5 million people.1 Fluoxetine, a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI), is used to treat depression and emotional lability after stroke. Many clinical and preclinical studies have suggested that SSRIs might improve outcomes after stroke through a range of mechanisms, which include enhancing neuroplasticity and promoting neurogenesis. In 2011, the results of the FLAME (FLuoxetine for motor recovery After acute ischaeMic strokE) trial indicated that fluoxetine enhanced motor recovery.2 In this double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial, 118 patients with ischaemic stroke and unilateral motor weakness, and a median National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score of 13, were randomly allocated between 5 and 10 days after stroke onset to receive fluoxetine 20 mg daily or placebo for 3 months. At day 90, the improvement from baseline in the Fugl-Meyer motor score was significantly greater in the fluoxetine group than in the placebo group. Additionally, the proportion of patients who were independent in daily living (with a modified Rankin Scale [mRS] score of 0–2) was significantly higher in the fluoxetine group than in the placebo group (26% vs 9%, p=0·015). More participants were free from depression at 3 months in the fluoxetine group than in the placebo group (93% vs 71%; p=0·002). A subsequent Cochrane systematic review3 of SSRIs for stroke recovery identified 52 randomised controlled trials of SSRIs versus controls (in 4060 patients), but no others tested the effect of fluoxetine on functional outcomes measured with the mRS. The findings of the Cochrane review suggested that SSRIs might reduce post-stroke disability, although this estimate was based on a meta-analysis done across various measures of function and greater effects were seen if studies with increased risk of bias were retained and patients with depression were included. Although promising, data from the FLAME trial and the Cochrane review were not sufficiently compelling to alter stroke treatment guidelines or to alleviate concerns that any possible benefits might be offset by serious adverse reactions.4

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

We searched the literature in July, 2018, using the same search strategy as that of a 2012 Cochrane review. In addition to the FLAME (FLuoxetine for motor recovery After acute ischaeMic strokE) trial we identified three other small, randomised, placebo-controlled trials of fluoxetine, which enrolled patients who did not have depression at recruitment and which reported the modified Rankin Scale (mRS) during follow-up. These three trials recruited a total of 154 patients and reported improvements in the mRS in those allocated fluoxetine, but two trials (n=122) did not publish their mRS data in a format that would facilitate a meta-analysis. The FLAME trial indicated that fluoxetine, when given to patients with a recent ischaemic stroke, a motor deficit, and a median National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) of 13, improved recovery in motor function as measured by the Fugl-Meyer motor score at about 3 months. In a published post-hoc analysis, the proportion of patients who were independent in daily living (mRS 0–2) was significantly higher in the fluoxetine group than in the placebo group (26% vs 9%, p=0·015). However, an ordinal analysis of the mRS data did not show a significant difference between groups (common odds ratio 1·501 [95% CI 0·757–2·974]; p=0·2446).

Added value of this study

The results of the Fluoxetine Or Control Under Supervision (FOCUS) trial suggest that fluoxetine 20 mg given orally daily for 6 months after acute stroke does not improve functional outcomes. Although the treatment might lead to a reduction in the occurrence of depression, it also seems to increase the frequency of bone fractures. These results do not support the routine use of fluoxetine either for prevention of post-stroke depression or to promote recovery of function.

Implications of all the available evidence

Ongoing trials might be able to confirm the external generalisability of these findings to different populations, and a planned individual patient data meta-analysis could clarify whether any subgroups might benefit from fluoxetine and provide more precise estimates of any harms.

The primary aim of the Fluoxetine Or Control Under Supervision (FOCUS) trial was to ascertain whether patients with a clinical stroke diagnosis would have improved functional outcomes with a 6-month course of fluoxetine compared with placebo. Important secondary aims were to identify any other benefits or harms and to assess whether any benefits persisted from the end of the treatment period to 12 months after stroke.

Methods

Study design and patients

FOCUS was a pragmatic, multicentre, parallel group, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial done at 103 hospitals in the UK. The protocol and statistical analysis plan were published before completion of follow-up.5, 6

Patients were eligible if they were aged 18 years or older; had a clinical diagnosis of acute stroke with brain imaging compatible with intracerebral haemorrhage or ischaemic stroke (including a normal brain scan); were randomly assigned between 2 days and 15 days after stroke onset; and had a persisting focal neurological deficit at the time of randomisation that was severe enough to warrant 6 months of treatment from the patient's or carer's perspective.

Patients were excluded if they had subarachnoid haemorrhage except where secondary to a primary intracerebral haemorrhage; they were unlikely to be available for follow-up for the following 12 months; they were unable to speak English and had no close family member available to help with follow-up; they had another life-threatening illness (eg, advanced cancer) that would make 12-month survival unlikely; they had a history of epileptic seizures; they had a history of allergy to fluoxetine; they had contraindications to fluoxetine, including hepatic impairment (alanine aminotransferase more than three times the upper normal limit) or renal impairment (creatinine >180 μmol/L); they were pregnant or breastfeeding, or women of childbearing age not taking contraception; they had a previous drug overdose or attempted suicide; they were already enrolled into a controlled trial of an investigational medicinal product; they had current or recent (within the last month) depression treated with an SSRI; or they were taking or had, in the past 5 weeks, taken medications that have a potentially serious interaction with fluoxetine.

Patients (or their carers or relatives if patients had mental incapacity) provided written informed consent.

We monitored the quality and integrity of the accumulating clinical data according to a protocol agreed with the study sponsors (the Academic and Clinical Central Office for Research and Development [ACCORD] representing the University of Edinburgh and NHS Lothian), which involved central statistical monitoring, supplemented by onsite monitoring and detailed source data verification in the coordinating centre and triggered visits when patterns in the data at a centre seemed anomalous. All FOCUS monitoring procedures were compliant with requirements of the study sponsors, the ethics committee and regulatory agencies, and they met all appropriate regulatory and good clinical practice requirements. All baseline data, inpatient data, and 6-month and 12-month outcome data were subject to verification checks built into the randomisation and data management system.

During recruitment, interim analyses of baseline and follow-up data were supplied, in strict confidence at least once every year, to the chairman of the data monitoring committee. In light of these analyses, the data monitoring committee advised the chairman of the trial steering committee whether, in their view, the randomised comparisons provided “proof beyond reasonable doubt” that for all, or some, patients the treatment was clearly indicated or contraindicated, and evidence that might reasonably be expected to materially influence future patient management.

The protocol was approved by the Scotland A Multicentre Research Ethics Committee (Dec 21, 2011). The study was jointly sponsored by the University of Edinburgh and NHS Lothian. The full protocol is available in the appendix.

Randomisation and masking

Patients were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to receive fluoxetine or placebo, by use of a centralised randomisation system. The clinician entered the patient's baseline data into a secure web-based randomisation system hosted by the University of Edinburgh. After the data were checked for completeness and consistency, the system generated a unique study identification number and a treatment pack number, which corresponded to either fluoxetine or placebo. A minimisation algorithm7 was used to achieve optimum balance between treatment groups for the following factors: delay since stroke onset (2–8 days vs 9–15 days), computer-generated prediction of 6-month outcome (probability of mRS8 0 to 2 was ≤0·15 vs >0·15 based on the six simple variable [SSV] model9), and presence of a motor deficit or aphasia (according to the NIHSS).10 The SSV model includes the patient's age; whether the patient is independent in activities of daily living before the stroke; whether they are living alone before the stroke; whether they are able to lift both arms off the bed; whether they are able to walk unassisted; whether they are able to talk, and whether they are not confused.9 The randomising clinicians in each centre had received training and certification in the application of the NIHSS. The system also incorporated an element of randomisation over and above the minimisation algorithm, so that it allocated patients to the treatment group that minimised the difference between groups with a probability of 0·8 rather than 1·0.7

Patients, their families, and the health-care team including the pharmacist, staff in the coordinating centre, and anyone involved in outcome assessments were all masked to treatment allocation by use of a placebo capsule that was visually identical to the fluoxetine capsules even when broken open. An emergency unblinding system was available but was designed so that those in the coordinating centre and those doing follow-up remained masked to treatment allocation.

Procedures

Fluoxetine 20 mg or placebo were administered to patients orally once daily for 6 months. The study medication (active and placebo) was manufactured by Unichem (Goa, India), imported by Niche Generics Ltd (Hitchin, UK), purchased from Discovery Pharmaceuticals Ltd (Castle Donington, UK), and quality assured, packaged, labelled, and distributed by Sharp Clinical Services. Patients were supplied with 186 capsules and were prescribed the study medication (20 mg capsules of fluoxetine or placebo capsule) to be taken daily. If a patient was unable to swallow capsules and had an enteral feeding tube in place, the capsules were broken open and the contents put down the tube according to accepted methods.11 We measured adherence to the study medication by recording the date of the first and last dose taken, the number of missed doses while in hospital, capsule counts when unused capsules were returned, and estimated adherence at the 6-month follow-up. We recorded the reasons for stopping the study medication early. Our primary measure of adherence was the best estimate of the interval between the first and last dose based on all the information available. Therefore, for a particular patient a capsule count might lead us to modify the estimate of the timing of the last dose.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was functional status, measured with the mRS, at the 6-month follow-up. We used the simplified mRS questionnaire (smRSq) delivered by post.8, 12, 13 Among those without a complete postal questionnaire, a telephone interview was done for any further clarification, for completion of missing items, or for the whole questionnaire. Those doing telephone assessments (chief investigators or other staff at the coordinating centre) were trained in their use.

Secondary outcomes were survival at 6 and 12 months, functional status at 12 months (mRS), and health status with the Stroke Impact Scale (SIS; for each of nine domains on which the patient scores 0–100).14, 15, 16, 17, 18 Arm, hand, leg, and foot strength; hand function; mobility; communication and understanding; memory and think_ing; mood and emotions; daily activities; and participation in work, leisure, and social activities were assessed by a Likert scale. Overall rating of recovery was assessed on a visual analogue scale. Mood was assessed with the Mental Health Inventory (MHI-5).19, 20 Fatigue was measured on the Vitality subscale of SF36.21, 22 Health-related quality of life was measured with the EuroQoL-5 Dimensions-5 Levels (EQ5D-5L) to generate utilities.23 The following adverse events and safety outcomes were systematically recorded: recurrent stroke including ischaemic and haemorrhagic strokes, acute coronary syndromes, epileptic seizures, hyponatraemia (<125 mmol/L), upper gastrointestinal bleeding, other major bleeding (lower gastrointestinal, extracranial, subdural, extradural, and subarachnoid), poorly controlled diabetes including hyperglycaemia (>22 mmol/L) and symptomatic hypoglycaemia, falls resulting in injury, bone fractures, new depression (including a diagnosis made by their treating clinician and initiation of a new antidepressant prescription), and self-harm.

The recruiting hospitals monitored adherence, identified adverse events in hospital, and completed the follow-up form at hospital discharge or death in hospital. National coordinating centre staff followed up patients at 6 months and 12 months to measure the primary and secondary outcomes. Data on adverse events and medications were also collected from patients' general practitioners at 6 months and 12 months.

Our protocol stipulated that if patients developed depression that a clinician wished to treat with an antidepressant during the treatment period, then the clinician should continue the study medication and avoid the use of an SSRI if possible, and instead use either mirtazapine, trazadone, or a tricyclic antidepressant. We monitored the use of all antidepressants during follow-up.

Statistical analysis

We aimed to recruit at least 3000 patients. We estimated that this sample size would allow us to identify a treatment effect size of fluoxetine in the FOCUS trial that we thought would be important to patients and health and social care services. This effect size would also justify a 6-month course of treatment. FOCUS had 90% power to identify an increase in the proportion of patients with good outcomes (ie, mRS of 0–2) from 39·6% to 44·7% (ie, an absolute difference of 5·1 percentage points), based on an ordinal analysis expressed as a common odds ratio (OR) of 1·23.

The unmasked trial statistician (C Graham) prepared analyses of the accumulating data, which the data monitoring committee reviewed in strict confidence at least once a year. No other members of the trial team, trial steering committee, or patients had access to these analyses. Before recruitment was completed, and without input from the unmasked trial statistician or reference to the unblinded data, the trial steering committee prepared a detailed statistical analysis plan that was then published.6 For all primary analyses, including our primary analyses of adverse events and safety outcomes, we retained patients in the treatment group to which they were randomly allocated irrespective of the treatment they had actually received. We did a secondary safety analysis according to the treatment patients actually received rather than what they were randomly allocated (comparing those who received some fluoxetine in the first 6 months and those who received no fluoxetine).

Inevitably, some patients withdrew from the trial and were lost to follow-up. Some did not return follow-up questionnaires or left items blank. We excluded patients who had no follow-up data from the analyses, and did sensitivity analyses to assess the effect of these exclusions on the results.

For our primary outcome we did an ordinal analysis expressing the result as a common OR and 95% CI, where a common OR in favour of placebo is less than 1·0, adjusted with logistic regression for the variables in the minimisation algorithm. We did Cox proportional hazards modelling to analyse the effect of treatment on survival up to 12 months, also adjusting for variables included in our minimisation algorithm. We compared the frequency of outcome events by calculating the differences in proportions between treatment groups with their 95% CIs and p values. We present the median scores on the SIS, MHI-5, and the Vitality subscale of the SF36, and EQ5D-5L with the IQRs and p value derived by non-parametric methods (Mann-Whitney test). For all these scales, higher values represent better outcomes.

Prespecified subgroup analyses were the effect of treatment allocation on the primary outcome subdivided by key baseline variables described in our published statistical analysis plan,6 including the probability of being alive and independent (0·00 to ≤0·15 vs >0·15 to 1·00); delay from stroke onset to randomisation (2–8 days vs 9–15 days), motor deficit (present or absent) or aphasia (present or absent), pathological type of stroke (ischaemic vs haemorrhagic), and age (≤70 years vs >70 years); ability to consent for themselves (yes or no); whether or not mood was assessable at baseline, and whether the patient was or was not depressed at baseline. Subgroup analyses were done by observing the change in log-likelihood when the interaction between the treatment and the subgroup was added into a logistic regression model. Statistical analyses were done with SAS, version 9.2.

The study is registered with the ISRCTN registry, number ISRCTN83290762.

Role of the funding source

None of the funding organisations had any role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of this report, or the decision to publish. The corresponding author had full access to all data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Results

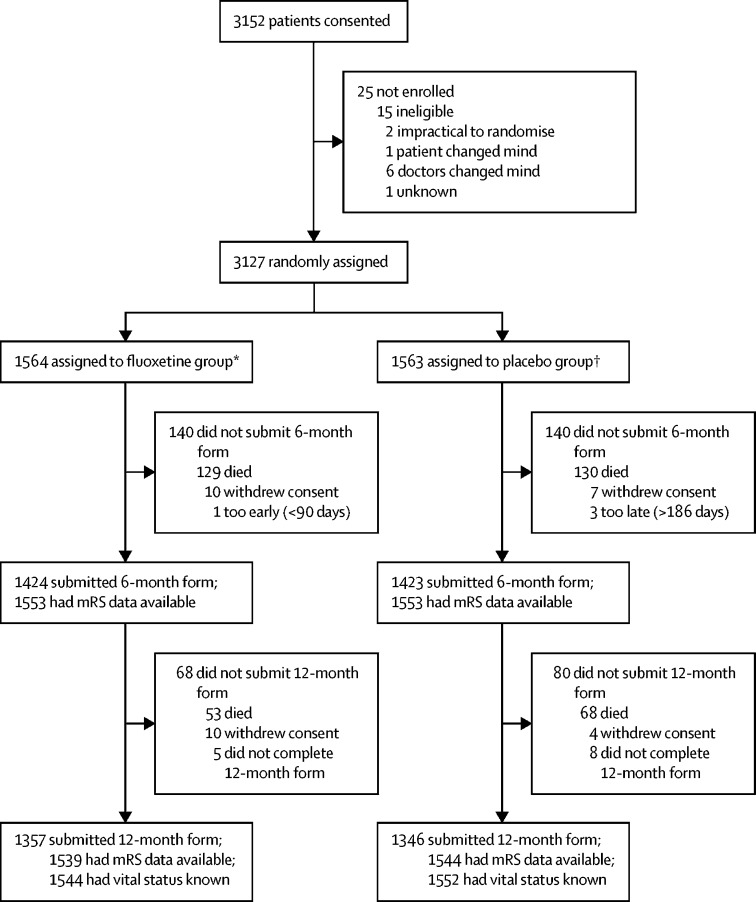

Between Sept 10, 2012, and March 31, 2017, 3152 patients consented and 3127 were enrolled. 25 patients were not enrolled; 15 were identified as ineligible between obtaining consent and randomisation and in nine cases the patients, their carer or family member, or their treating clinician changed their mind about participation in the trial (figure 1). Of the 3127 patients enrolled, 1564 were allocated fluoxetine and 1563 allocated placebo. 11 patients did not meet our eligibility criteria after randomisation: two in each group had a final diagnosis other than stroke, and seven others (three in the fluoxetine group and four in the placebo group) were identified as having exclusion criteria (eg, a history of epilepsy, self-harm, or some other contraindication to fluoxetine). Ineligible patients were retained in our intention-to-treat analyses. Baseline characteristics of the two treatment groups were well balanced (table 1) and were similar to those of unselected patients with stroke admitted to UK hospitals (appendix). 1393 (49%) of 2847 6-month follow-up assessments were obtained by postal questionnaire (693 in the fluoxetine group and 700 in the placebo group); the remainder required a telephone reminder or were completed by telephone interview (appendix). The emergency unblinding procedure was done in only three patients, all allocated fluoxetine (one at the request of a coroner, after the patient died, one for a suspected unexpected serious adverse reaction, and one because the responsible clinician felt that knowledge of the treatment would substantially alter their management of the patient).

Figure 1.

Trial profile

mRS=modified Rankin Scale. *1544 inpatients with discharge form; 20 recruited as outpatients. †1536 inpatients with discharge form; 27 recruited as outpatients.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics at randomisation by allocated treatment

| Fluoxetine (n=1564) | Placebo (n=1563) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| Women | 589 (38%) | 616 (39%) | |

| Men | 975 (62%) | 947 (61%) | |

| Age | |||

| Age ≤70 years | 666 (43%) | 664 (42%) | |

| Age >70 years | 898 (57%) | 899 (58%) | |

| Mean age, years | 71·2 (12·4) | 71·5 (12·1) | |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Asian | 30 (2%) | 31 (2%) | |

| Black | 35 (2%) | 29 (2%) | |

| Chinese | 0 (0%) | 1 (0%) | |

| White | 1495 (96%) | 1493 (96%) | |

| Other | 4 (0%) | 9 (1%) | |

| Marital status | |||

| Married | 879 (56%) | 846 (54%) | |

| Partner | 93 (6%) | 91 (6%) | |

| Divorced or separated | 109 (7%) | 100 (6%) | |

| Widowed | 337 (22%) | 354 (23%) | |

| Single | 124 (8%) | 150 (10%) | |

| Other | 22 (1%) | 22 (1%) | |

| Living arrangement | |||

| Living with someone else | 1057 (68%) | 1034 (66%) | |

| Lives alone | 485 (31%) | 516 (33%) | |

| Living in an institution | 10 (1%) | 4 (0%) | |

| Other | 12 (1%) | 9 (1%) | |

| Employment status | |||

| Full-time employment | 287 (18%) | 258 (17%) | |

| Part-time employment | 76 (5%) | 70 (4%) | |

| Retired | 1122 (72%) | 1134 (73%) | |

| Unemployed or disabled | 53 (3%) | 60 (4%) | |

| Other | 26 (2%) | 41 (3%) | |

| Independent before stroke | 1431 (92%) | 1435 (92%) | |

| Previous medical history | |||

| Coronary heart disease | 281 (18%) | 300 (19%) | |

| Ischaemic stroke or TIA | 274 (18%) | 294 (19%) | |

| Diabetes | 337 (22%) | 303 (19%) | |

| Hyponatraemia | 19 (1%) | 26 (2%) | |

| Intracranial bleed | 27 (2%) | 23 (1%) | |

| Upper gastrointestinal bleed | 25 (2%) | 26 (2%) | |

| Bone fractures | 241 (15%) | 256 (16%) | |

| Depression | 130 (8%) | 123 (8%) | |

| Stroke diagnosis | |||

| Non-stroke (final diagnosis) | 2 (0%) | 2 (0%) | |

| Ischaemic stroke | 1410 (90%) | 1406 (90%) | |

| Intracerebral haemorrhage | 154 (10%) | 157 (10%) | |

| OCSP classification of ischaemic strokes24 | |||

| Total anterior circulation infarct | 318 (20%) | 317 (20%) | |

| Partial anterior circulation infarct | 561 (36%) | 553 (35%) | |

| Lacunar infarct | 307 (20%) | 283 (18%) | |

| Posterior circulation infarct | 191 (12%) | 230 (15%) | |

| Uncertain | 33 (2%) | 23 (2%) | |

| Cause of stroke, modified TOAST classification25 | |||

| Large artery disease | 278 (18%) | 234 (15%) | |

| Small vessel disease | 252 (16%) | 218 (14%) | |

| Embolism from heart | 377 (24%) | 411 (26%) | |

| Another cause | 38 (2%) | 35 (2%) | |

| Unknown or uncertain | 465 (30%) | 508 (33%) | |

| Predictive variables | |||

| Able to walk at time of randomisation | 435 (28%) | 412 (26%) | |

| Able to lift both arms off bed | 924 (59%) | 935 (60%) | |

| Able to talk and not confused | 1166 (75%) | 1164 (74%) | |

| Predicted 6-month outcome based on SSV | |||

| Probability of being alive and independent | 0·28 (0·07–0·63) | 0·26 (0·07–0·63) | |

| 0·00 to ≤0·15 | 592 (38%) | 591 (38%) | |

| >0·15 to 1·00 | 972 (62%) | 972 (62%) | |

| Neurological deficits | |||

| NIHSS | 6 (3–11) | 6 (3–11) | |

| Presence of a motor deficit | 1361 (87%) | 1361 (87%) | |

| Presence of aphasia | 457 (29%) | 449 (29%) | |

| Depression at baseline | |||

| Current diagnosis of depression (patient or proxy reported) | 26 (2%) | 18 (1%) | |

| Taking a non-SSRI antidepressant | 65 (4%) | 77 (5%) | |

| Current mood, PHQ-226 | |||

| 2 yes responses | 81 (5%) | 60 (4%) | |

| 1 yes response | 136 (9%) | 130 (8%) | |

| 0 yes responses | 1347 (86%) | 1373 (88%) | |

| Delay (days) since stroke onset at randomisation | |||

| Mean delay | 6·9 (3·6) | 7·0 (3·6) | |

| 2–8 days | 1070 (68%) | 1072 (69%) | |

| 9–15 days | 494 (32%) | 491 (31%) | |

| Details of enrolment | |||

| Enrolled as a hospital inpatient (not outpatient clinic) | 1544 (99%) | 1536 (98%) | |

| Patient consented | 1136 (73%) | 1118 (72%) | |

| Proxy consented | 428 (27%) | 445 (28%) | |

Data are n (%), mean (SD), or median (IQR). TIA=transient ischaemic attack. OCSP=Oxfordshire Community Stroke Project. SSV=six simple variable. NIHSS=National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale. SSRI=selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor. PHQ-2=Patient Health Questionnaire 2.

The primary measure of adherence was the estimated duration of study medication (interval in days from first to last dose of study medication) based on all available data, including a capsule count, which was available in 398 (25%) of 1564 patients allocated fluoxetine, and 410 (26%) of 1563 allocated placebo. Patients returned a median of 32 capsules (IQR 10–135) in the fluoxetine group and 33 (11–139) in the placebo group. Our primary measure of adherence was available in 1417 (91%) patients in each group. The median duration of treatment was 185 days (IQR 149–186) in the fluoxetine group, and 183 days (136–186) in the placebo group. The median delay between randomisation and first dose was 0 days (IQR 0–1) in both treatment groups. 1519 (97%) patients in the fluoxetine group and 1494 (96%) in the placebo group received their first dose by day 2 after randomisation. The number and proportion of patients meeting our eligibility criteria and with different levels of adherence to the study medication are shown in the appendix. 143 (9%) patients in the fluoxetine group stopped the trial medication because of perceived adverse effects within the first 90 days compared with 122 (8%) in the placebo group. Around two-thirds of patients took the study medication for at least 150 days.

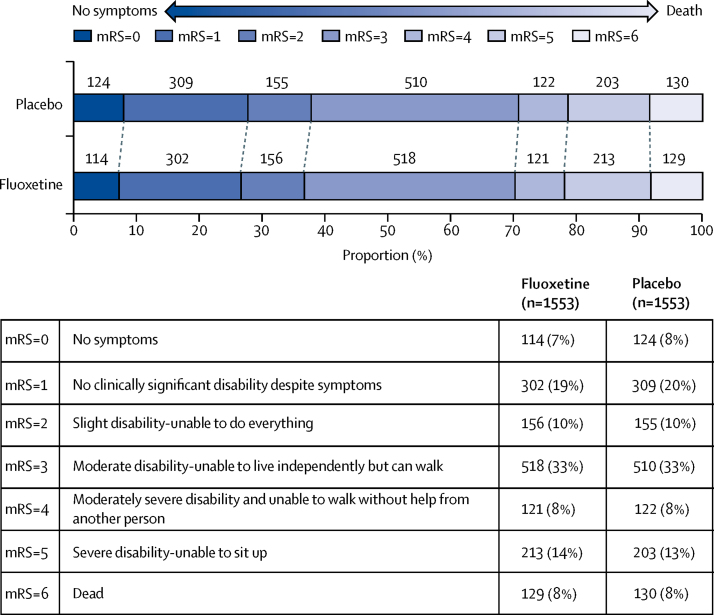

The primary outcome, an ordinal comparison of the distribution of patients across the mRS categories at 6 months, adjusted for variables included in the minimisation algorithm, was similar in the two groups (common OR 0·951 [95% CI 0·839–1·079]; p=0·439; figure 2). The unadjusted analysis provided similar results (common OR 0·961 [95% CI 0·848–1·089]; p=0·531). The ordinal analysis was done with the assumption of proportional odds, in the model of mRS by treatment. This assumption was found to hold in the score test for proportional odds assumption (p=0·9947). Comparison of the mRS dichotomised into 0–2 vs 3–6 similarly showed no significant difference between the groups (adjusted OR 0·955 [95% CI 0·812–1·123], p=0·576; unadjusted OR 0·957 [0·827–1·107], p=0·352).

Figure 2.

Primary outcome of disability on the modified Rankin Scale at 6 months by treatment group

Ordinal analysis of the modified Rankin Scale (mRS) adjusted with logistic regression for the variables included in our minimisation algorithm. 1553 patients had mRS data available in each group; 11 patients in the fluoxetine group and ten in the placebo group had missing mRS data. Common odds ratio 0·951 (95% CI 0·839–1·079), p=0·439; adjusted for baseline variables.

The results of our prespecified subgroup analyses are shown in the appendix. No significant interactions were observed between the prespecified subgroups and the effect of treatment on the primary outcome.

The appendix shows the effect of fluoxetine on our primary outcome in subgroups defined by the eligibility criteria and increasing degrees of adherence to the study medication; we did a series of prespecified per-protocol analyses, which sequentially excluded subgroups of patients who either did not meet our eligibility criteria or had incomplete adherence to the study medication.6 We did not observe greater benefit in patients with greater adherence.

Secondary outcomes at 6 months are shown in table 2 and adverse events at 6 months shown in table 3. Patients allocated fluoxetine were less likely than those allocated placebo to be diagnosed with new depression at 6 months (210 [13·43%] patients vs 269 [17·21%]; difference in proportions 3·78% [95% CI 1·26–6·30]; p=0·0033) and had better mood measured on MHI-5 at the 6-month follow-up (median 76 [IQR 60–88] vs 72 [56–88]; p=0·0100). Those allocated fluoxetine had an increased risk of bone fractures compared with those allocated placebo (45 [2·88%] patients vs 23 [1·47%]; difference in proportions 1·41% [95% CI 0·38–2·43]; p=0·0070). There were no significant differences in any other secondary outcomes at 6 months, including any of the nine domains of the SIS, the Vitality subscale of SF36, and EQ5D-5L (table 2) or other recorded adverse reactions (table 3). The appendix shows the progress through the trial for patients who received any fluoxetine and those who received no fluoxetine by 6 months. Adverse events and safety outcomes in patients who received any fluoxetine within the first 6 months and those who received no fluoxetine, irrespective of the group to which they were allocated, are shown in the appendix.

Table 2.

Secondary outcomes at 6 months by allocated treatment

| Fluoxetine | Placebo | p value* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SIS | ||||

| Strength | 56·25 (31·25–81·25) | 62·50 (37·50–81·25) | 0·7008 | |

| Hand ability | 45·00 (0·00–90·00) | 50·00 (0·00–90·00) | 0·4824 | |

| Mobility | 63·89 (36·11–86·11) | 63·89 (33·33–88·89) | 0·5486 | |

| Motor† | 54·86 (27·31–83·33) | 56·78 (28·75–82·64) | 0·5125 | |

| Daily activities | 62·50 (37·50–90·00) | 65·00 (35·00–90·00) | 0·6235 | |

| Physical function‡ | 56·77 (30·38–84·31) | 58·82 (30·56–84·10) | 0·5154 | |

| Memory | 82·14 (57·14–96·43) | 82·14 (57·14–96·43) | 0·3070 | |

| Communication | 89·29 (67·86–100) | 92·86 (71·43–100·0) | 0·1919 | |

| Emotion | 75·00 (58·33–88·89) | 75·00 (58·33–88·89) | 0·4687 | |

| Participation | 62·50 (37·50–87·50) | 65·63 (40·63–87·50) | 0·2595 | |

| Recovery (VAS) | 60·00 (40·00–80·00) | 60·00 (40·00–80·00) | 0·9820 | |

| Vitality | 56·25 (37·50–75·00) | 56·25 (43·75–75·00) | 0·6726 | |

| MHI-5 | 76·00 (60·00–88·00) | 72·00 (56·00–88·00) | 0·0100 | |

| EQ5D-5L | 0·56 (0·21–0·74) | 0·56 (0·19–0·75) | 0·5866 | |

Data were only available for those who survived and who completed sufficient questions to derive a score. The number of patients with missing scores was similar in the two treatment groups. The number of survivors with missing data across both treatment groups varied from 16 for EQ5D-5L and Mobility to 71 for Emotion. Data are median (IQR). EQ5D-5L=EuroQoL-5 Dimensions-5 Levels (where 1 indicates perfect health, and <0=worse than death). VAS=visual analogue scale. MHI-5=Mental Health Inventory 5 (where higher scores are better). SIS=Stroke Impact Scale (where higher scores are better).

Mann-Whitney test.

Mean of the Strength, Hand ability, and Mobility domains.

Mean of the Strength, Hand ability, Mobility, and Daily activities domains.

Table 3.

Adverse events at 6 months by treatment group

| Fluoxetine (n=1564) | Placebo (n=1563) | Difference (95% CI) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any stroke | 56 (3·58%) | 64 (4·09%) | −0·51% (−1·90 to 0·80) | 0·4543 |

| All thrombotic events | 78 (4·99%) | 92 (5·89%) | −0·90% (−2·49 to 0·69) | 0·2677 |

| Ischaemic stroke | 43 (2·75%) | 45 (2·88%) | −0·13% (−1·30 to 1·00) | 0·8264 |

| Other thrombotic events | 20 (1·28%) | 27 (1·73%) | −0·45% (−1·30 to 0·40) | 0·3025 |

| Acute coronary events | 15 (0·96%) | 23 (1·47%) | −0·51% (−1·28 to 0·26) | 0·1910 |

| All bleeding events | 41 (2·62%) | 38 (2·43%) | 0·19% (−0·91 to 1·29) | 0·7346 |

| Haemorrhagic stroke | 7 (0·45%) | 9 (0·58%) | −0·13% (−0·60 to 0·37) | 0·6153 |

| Upper gastrointestinal bleed | 21 (1·34%) | 16 (1·02%) | 0·32% (−0·44 to 1·08) | 0·4094 |

| Other major bleeds | 13 (0·83%) | 14 (0·90%) | −0·06% (−0·71 to 0·58) | 0·8454 |

| Epileptic seizures | 58 (3·71%) | 40 (2·56%) | 1·15% (−0·07 to 2·37) | 0·0651 |

| Fall with injury | 120 (7·67%) | 94 (6·01%) | 1·66% (−0·11 to 3·43) | 0·0663 |

| Fractured bone | 45 (2·88%) | 23 (1·47%) | 1·41% (0·38 to 2·43) | 0·0070 |

| Hyponatraemia <125 mmol/L | 22 (1·41%) | 14 (0·90%) | 0·51% (−0·24 to 1·26) | 0·1805 |

| Hyperglycaemia | 23 (1·47%) | 16 (1·02%) | 0·45% (−0·33 to 1·22) | 0·2602 |

| Symptomatic hypoglycaemia | 23 (1·47%) | 13 (0·83%) | 0·64% (−0·11 to 1·39) | 0·0940 |

| New depression | 210 (13·43%) | 269 (17·21%) | −3·78% (−6·30 to −1·26) | 0·0033 |

| New antidepressant | 280 (17·90%) | 357 (22·84%) | −4·94% (−7·76 to −2·12) | 0·0006 |

| Attempted or actual suicide | 3 (0·19%) | 2 (0·13%) | 0·06% (−0·02 to 0·34) | 0·6550 |

Data are n (%), unless otherwise stated.

The appendix shows secondary outcomes at 12 months. The difference in MHI-5 at 6 months was not sustained at 12 months, and the difference between the two treatment groups in the cumulative number of patients diagnosed with new depression over 12 months was no longer significant. More patients had been started on antidepressants in the placebo group than in the fluoxetine group, but some were started on antidepressants for indications other than depression. There were no significant differences between treatment groups in any other secondary outcomes at 12 months, including survival (hazard ratio 0·929 [95% CI 0·756–1·141]; p=0·4819; appendix).

We assessed the effect of treatment among the subgroup with motor deficit at baseline (n=2702) but found no evidence of an effect on the mRS (common OR 0·919 [95% CI 0·803–1·051]; p=0·2172) or on motor score based on the mean of SIS Strength, Hand, and Mobility domains (fluoxetine median 48·43 [IQR 24·98–78·84] vs placebo 52·66 [25·28–77·22]; p=0·4714). Additionally, in patients with aphasia at baseline and an SIS communication domain score available at 6 months (n=894) we found no difference in median SIS communication domain scores (fluoxetine 64·29 [IQR 32·14–89·29] vs placebo 64·29 [35·71–89·29]; p=0·4971).

Discussion

The results of the FOCUS trial show that fluoxetine 20 mg given daily for 6 months after an acute stroke does not significantly improve patients' functional outcome or survival at 6 and 12 months. However, fluoxetine decreased the occurrence of depression and increased bone fractures at 6 months.

The strengths of the study, supporting the internal validity of the results, are that bias was minimised by central randomisation without any prospect of foreknowledge; patients, carers, and outcome assessment were masked (with only three episodes of unmasking); there were few losses to follow-up (<1%), and prespecified intention-to-treat analyses were done. The small difference in the numbers of patients stopping the trial medication for perceived adverse effects suggests that unmasking because of adverse effects was unlikely to have had a significant effect on our results. In any case, expectation bias would normally be expected to bias the result in favour of active treatment. Random error was also minimised by the large sample size and high rates of follow-up, which provided greater statistical power than in previous similar trials. The external validity of the results, at least for the UK stroke population, is supported by the large number of participating hospitals throughout the UK. Compared with unselected patients with stroke admitted to UK hospitals (appendix), there were few differences in the baseline characteristics of patients enrolled in the FOCUS trial.27, 28 Patients enrolled in FOCUS had slightly more severe strokes than unselected patients (NIHSS 6 vs 4), which probably reflected inclusion criteria that required patients to have a neurological deficit persisting at the time of enrolment. Also, 60% of enrolled patients were men compared with a UK average of 50%—an unexplained but common observation in stroke trials.29 Enrolled patients were slightly younger than the UK average (71 years vs 77 years), which might partly explain the male preponderance, with older women being under-represented. Many studies included in the previously published systematic review of randomised controlled trials of fluoxetine were from China, whereas non-white patients comprised less than 5% of those recruited in FOCUS. The ongoing AFFINITY trial is recruiting in Vietnam and will include a larger proportion of Asian patients.5

The validity of our results is also supported by the observed reduction in the occurrence of new post-stroke depression at 6 months with fluoxetine, which is consistent with its known antidepressant effects and the results of the FLAME trial. A previous systematic review of five randomised controlled trials (two of fluoxetine, two of sertraline, and one of escitalopram), including FLAME, in patients with stroke and no depression tested whether SSRIs prevented the development of post-stroke depression.30 In a pooled analysis, 23 (9·3%) of 248 patients treated with an SSRI developed post-stroke depression compared with 59 (24·4%) of 242 treated with a placebo (OR 0·37 [95% CI 0·22–0·61]; p=0·001). The rate of depression in the placebo groups of these trials was much higher than that in FOCUS, which might have reflected the characteristics of the patients (as they tended to have had more severe strokes than those enrolled in FOCUS) or the different methods of diagnosing depression. Although this observation is consistent with our findings in terms of the direction (but not the magnitude) of treatment effect, it does not take into account the possible excess risk of adverse effects (such as bone fractures), which might offset any benefits of reducing the frequency of post-stroke depression.

The observed 1·4% absolute excess risk of bone fractures at 6 months with fluoxetine in FOCUS is also consistent with previous reports from large case-control and cohort studies.31 The magnitude of the increased risk in previous observational studies tended to be greater than in FOCUS, but this difference might be attributable to the inherent confounding by treatment indication in observational studies. The rates of serious adverse reactions to fluoxetine referred to in the summary of product characteristics, which we included as secondary outcomes in this trial (eg, epileptic seizures, falls, hyponatraemia, uncontrolled diabetes, and upper gastrointestinal bleeding), were higher in the fluoxetine group than in the placebo group, but the absolute differences were small and not significant. Despite concerns about the effects of fluoxetine on platelet function and interactions with antiplatelet and anticoagulant medications, we observed no effect on bleeding or thrombotic adverse events.

The main limitation of FOCUS was the moderate adherence to the trial medication, which might have led us to under-estimate any treatment effect. However, adherence measured in FOCUS was superior to that reported in routine clinical practice, and did not differ substantially between the treatment groups.32 Differences in adherence between the fluoxetine and placebo groups were more likely if reduced adherence resulted from possible adverse reactions or perceived change (or no change) in patients' conditions. We repeated the analysis of our primary outcome after sequentially excluding patients with different reasons for, and different degrees of, adherence. Such per-protocol analyses can increase the risk of bias, usually in favour of the active treatment. However, our analyses (shown in the appendix) did not show any increased benefit from fluoxetine in patients with greater adherence.

Our use of the smRSq as the primary outcome measure could be perceived as a limitation. However, the smRSq is a valid, reliable, and patient-centred measure of functional outcome, thus ensuring our results are relevant to patients and their families.8, 12, 13 Additionally, local, face-to-face assessments of outcomes might be more prone to unmasking than those done through postal and telephone follow-up because of patients reporting adverse effects of trial medication. We used patient-reported outcomes, the Patient Health Questionnaire 2 (PHQ-2) at baseline and the smRSq, MHI-5, and SIS motor score at follow-up by postal and telephone questionnaires. Other limitations of FOCUS include the absence of a standardised psychiatric assessment at baseline or follow-up and absence of a structured neurological examination during follow-up, which were impractical to include in this large, pragmatic, multicentre trial.

We cannot definitively exclude an effect of fluoxetine on a directly measured neurological deficit—such as the Fugl-Meyer motor score, which was measured in the FLAME trial. However, we have shown that a resulting improvement in functional status measured with the mRS or SIS is unlikely.

Other trials of similar design to FOCUS, but with smaller recruitment targets, are ongoing.5, 6 These studies should allow us to confirm the effects of fluoxetine on post-stroke depression and bone fractures, and provide more precise estimates of the benefits and harms of early fluoxetine, to guide its use in patients with stroke and perhaps other older people with comorbidities. These ongoing trials will also establish the external validity of the FOCUS trial in stroke populations with different ethnic groups and health-care backgrounds—for example, with different intensities of physical rehabilitation.

In summary, the results of the FOCUS trial show that fluoxetine 20 mg given daily for 6 months after an acute stroke did not influence patients' functional outcomes but did decrease the occurrence of depression and increase the occurrence of bone fractures. These results do not support the routine use of fluoxetine either for the prevention of post-stroke depression or to promote recovery of function. Ongoing trials and a planned individual patient data meta-analysis are needed to confirm or refute a more modest benefit, either overall or in particular subgroups, and to provide more precise estimates of any harms.

Data sharing

The study protocol and statistical analysis plan have been published.5, 6 A fully anonymised trial dataset with individual participant data and a data dictionary will be made available to other researchers after the publication of the full trial report in the Health Technology Assessment journal in 2019. Requests should first be directed to Martin Dennis (Co-Chief Investigator). Written proposals will be assessed by the FOCUS trial team and a decision made about the appropriateness of the use of data. A data sharing agreement will be put in place before any data will be shared.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

The start-up phase of the FOCUS trial was funded by the UK Stroke Association (TSA 2011101) and the main phase funded by the NIHR Health Technology Assessment Programme (project number 13/04/30). The views and opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the NIHR Health Technology Assessment Programme. Recruitment and follow-up was supported by the NIHR-funded UK Stroke Research Network and the Scottish Stroke Research Network, which was supported by NHS Research Scotland (NRS).

Contributors

MD was Co-Chief Investigator, participated in the steering committee, was involved in the design of the trial, and collected, verified, and analysed data and drafted this report. JF participated in the steering committee, was involved in the design of the trial, and analysed health economic data. CG participated in the steering committee, was involved in the design of the trial, wrote the first draft of the statistical analysis plan, and verified and analysed data. MH was involved in the trial design and helped conduct relevant systematic reviews. GJH was involved in the trial design and helped conduct relevant systematic reviews. AH was involved in the trial design and advised on the management of depression within the trial. SL was involved in the trial design and advised on the statistical analysis plan. EL was involved in the design of the trial. PS chaired the steering committee of the initial phase. GM was Co-Chief Investigator, participated in the steering committee, was involved in the design of the trial and data collection, and coordinated the systematic review of the randomised controlled trials. All members of the writing committee listed here have commented on the analyses and drafts of this report and have seen and approved the final version of the report.

Writing group of the FOCUS Trial Collaboration

Martin Dennis (Chair), John Forbes, Catriona Graham, Maree Hackett, Graeme J Hankey, Allan House, Stephanie Lewis, Erik Lundström, Peter Sandercock, Gillian Mead.

Declaration of interests

We declare no competing interests.

Contributor Information

FOCUS Trial Collaboration:

Martin Dennis, Gillian Mead, John Forbes, Catriona Graham, Maree Hackett, Graeme J Hankey, Allan House, Stephanie Lewis, Erik Lundström, Peter Sandercock, Karen Innes, Carol Williams, Jonathan Drever, Aileen Mcgrath, Ann Deary, Ruth Fraser, Rosemary Anderson, Pauli Walker, David Perry, Connor Mcgill, David Buchanan, Yvonne Chun, Lynn Dinsmore, Emma Maschauer, Amanda Barugh, Shadia Mikhail, Gordon Blair, Ingrid Hoeritzauer, Maggie Scott, Greig Fraser, Katherine Lawrence, Alison Shaw, Judith Williamson, David Burgess, Malcolm Macleod, Dan Morales, Frank Sullivan, Marian Brady, Ray French, Frederike Van Wijck, Caroline Watkins, Fiona Proudfoot, Joanna Skwarski, Diane Mcgowan, Rachael Murphy, Seona Burgess, William Rutherford, Katrina Mccormick, Ruaridh Buchan, Allan Macraild, Ruth Paulton, Adnan Fazal, Pat Taylor, Ruwan Parakramawansha, Neil Hunter, Jack Perry, John Bamford, Dean Waugh, Emelda Veraque, Caroline Bedford, Mary Kambafwile, Luis Idrovo, Linetty Makawa, Paula Smalley, Marc Randall, Tharani Thirugnana-Chandran, Ahamad Hassan, Richard Vowden, Joanne Jackson, Ajay Bhalla, Anthony Rudd, Chi Kai Tam, Jonathan Birns, Charlotte Gibbs, Leonie Lee Carbon, Elizabeth Cattermole, Katherine Marks, Angela Cape, Lisa Hurley, Sagal Kullane, Nigel Smyth, Charlotte Eglinton, Jennifer Wilson, Elio Giallombardo, Angela Frith, Paul Reidy, Matthew Pitt, Lucy Sykes, Deborah Dellafera, Victoria Croome, Lauriane Kerwood, Mirea Hancevic, Christina Narh, Carley Merritt, John Duffy, Duncan Cooke, Juliet Willson, Ali Ali, Aaizza Naqvi, Christine Kamara, Helen Bowler, Simon Bell, Tracy Jackson, Kirsty Harkness, Kathy Stocks, Suzanna Duty, Clare Doyle, Geoffrey Dunn, Keith Endean, Fiona Claydon, Emma Richards, Jo Howe, Ralf Lindert, Arshad Majid, Katy Dakin, Ahmad Maatouk, Luke Barron, Madana Meegada, Pratap Rana, Anand Nair, Christine Brighouse-Johnson, Jill Greig, Myint Kyu, Sanjeev Prasad, Matthew Robinson, Irfan Alam, Belinda Mclean, Lindsay Greenhalgh, Zenab Ahmed, Christine Roffe, Susan Brammer, Carole Beardmore, Kay Finney, Adrian Barry, Paul Hollinshead, Jeanette Grocott, Holly Maguire, Indira Natarajan, Jayan Chembala, Ranjan Sanyal, Sue Lijko, Nenette Abano, Alda Remegoso, Phillip Ferdinand, Stephanie Stevens, Resti Varquez, Chelsea Causley, Adrian Butler, Philip Whitmore, Caroline Stephen, Racquel Carpio, Joanne Hiden, Girish Muddegowda, Hayley Denic, Jane Sword, Ross Curwen, Martin James, Paul Mudd, Fiona Hall, Julie Cageao, Samantha Keenan, Caroline Roughan, Hayley Kingwell, Anthony Hemsley, Christoph Lohan, Sue Davenport, Angela Bowring, Tamika Chapter, Max Hough, David Strain, Karin Gupwell, Keniesha Miller, Anita Goff, Ellie Cusack, Shirley Todd, Rebecca Partridge, Georgiana Jennings, Kevin Thorpe, Jacquelyn Stephenson, Kelly Littlewood, Mark Barber, Fiona Brodie, Steven Marshall, Derek Esson, Irene Coburn, Caroline Mcinnes, Fiona Ross, Emma Bowie, Heather Barcroft, Victoria Withers, Laura Miller, Paul Willcoxson, Michelle Donninson, Richard Evans, Di Daniel, John Coyle, Michael Keeling, Peter Wanklyn, Mark Elliott, John Wightman, Elizabeth Iveson, Natasha Dyer, Anne-Marie Porteous, Monica Haritakis, Mandy Ward, Lucy Doughty, Lisa Carr, Mark O Neill, Cosmas Anazodo, Paul Wood, Poppy Cottrell, Cheryl Donne, Romina Rodriguez, Ruhail Mir, Jax Westmoreland, Judith Bell, Christopher Emms, Lorraine Wright, Pearl Clark Brown, Elizabeth Bamford, Andrew Stanners, Mike Carpenter, Prabal Datta, Richard Davey, Ann Needle, Marjorie Jane Eastwood, Fathima Zeena Razik, Imran Ghouri, Gavin Bateman, Judy Archer, Venkatesh Balasubramanian, Richard Bowers, Julie Ball, Louise Benton, Linda Jackson, Julie Ellam, Kate Norton, Paul Guyler, Terry Dowling, Sharon Tysoe, Paula Harman, Ashish Kundu, Ololade Omodunbi, Thayalini Loganathan, Stuart Chandler, Shanas Noor, Anwer Siddiqui, Amber Siddiqui, Swapna Kunhunny, Devesh Sinha, Martin Sheppard, Sindhu Rashmi, Elena France, Rajalakshmi Orath Prabakaran, Laura Wilson, Amiirah Ropun, Shyam Kelavkar, Kheng Xiong Ng, Lucy Kamuriwo, Sweni Shah, David Mangion, Camen Constantin, Luigi De Michele Hock, Anne Hardwick, Jayne Borley, Skarlet Markova, Kimberley Netherton, Tara Lawrence, Jo Fletcher, Rebecca Spencer, Helen Palmer, Claire Cullen, Dolores Hamill, Ramesh Durairaj, Zoe Mellor, Tanya Fluskey, Diane Wood, Alison Keeling, Victoria Hankin, Jennifer Peters, Daniela Shackcloth, Thant Hlaing, Rebecca Tangney, Jordan Ewing, Melanie Harrison, Sarah Stevenson, Victoria Sutton, Mohamed Soliman, Julia Hindle, Elizabeth Watson, Claire Hewitt, Jayne Borley, Susie Butler, Ibrahim Wahishi, Sarwat Arif, Amy Fields, Jagdish Sharma, Rose Brown, Caroline Taylor, Sarah Bell, Simon Leach, Chris Patterson, Sophia Khan, Helen Wilson, Joanne Price, Hawraman Ramadan, Stuart Maguire, Ruth Bellfield, Michaela Hooley, Umair Hamid, Waqar Gaba, Robina Ghulam, Leslie Masters, Outi Quinn, Lakshmanan Sekaran, Margaret Tate, Niaz Mohammed, Kiranjit Bharaj, Frances Justin, Rajan Pattni, Lanka Alwis, Sakthivel Sethuraman, Rianne Robinson, Lianne Eldridge, Susan Mintias, Meena Chauhan, Chi-Kai Tam, Jeremias Palmones, Clare Holmes, Lucy Belle Guthrie, Mairead Osborn, Lindsay Ball, Sarah Caine, Amy Steele, Peter Murphy, Nikki Devitt, Jayne Leonard, Ronak Patel, Ian Penwarden, Emily Dodd, Amy Holloway, Pauline Baker, Samantha Clarke, Sandra Williams, Lindsey Dow, Roland Wynn-Williams, James Kennedy, Rachel Teal, Ursula Schulz, Gary Ford, Philip Mathieson, Ian Reckless, Ana Deveciana, Paige Mccann, Gillian Cluckie, Geoffrey Howell, Jonathan Ayer, Barry Moynihan, Rita Ghatala, Brian Clarke, Geoffrey Cloud, Bhavini Patel, Usman Khan, Nia Al-Samarrai, Sarah Trippier, Neha Chopra, Temi Adedoyin, Fran Watson, Val Jones, Liqun Zhang, Lillian Choy, Rebecca Williams, Natasha Clarke, Adrian Blight, Kate Kennedy, Alice Dainty, Johann Selvarajah, Dheeraj Kalladka, Bharath Cheripelli, Wilma Smith, Fiona Moreton, Angela Welch, Xuya Huang, Elizabeth Douglas, Audrey Lush, Nicola Day, Salwa El Tawil, Karen Montgomery, Helen Hamilton, Doreen Ritchie, Sankaranarayanan Ramachandra, Kirsty Mcleish, Kamy Thavanesan, Sathyabama Loganathan, Josh Roberts, Chantel Cox, Sarah Orr, Alison Hogan, Divya Tiwari, Gail Hann, Barbara Longland, Owen David, Jo Bell, Catherine Ovington, Emily Rogers, Rachel Bower, Marketa Keltos, David Cohen, Joseph Devine, Lankantha Alwis, Lucy Southworth, Laura Burgess, Matilda Lang, Bhavna Badiani, Fenglin Guo, Anne Oshodi, Emmanuelle Owoyele, Norah Epie, Anette David, Mushiya Mpelembue, Rajaram Bathula, Mudhar Abdul-Saheb, Angela Chamberlain, Varthi Sudkeo, Khalid Rashed, Diane Wood, Barbara Williams-Yesson, Joanne Board, Sarah De Bruijn, Clare Buckley, Sarah Board, Joanna Allison, Elizabeth Keeling, Tracey Duckett, Dave Donaldson, Carinna Vickers, Claire Barron, Linda Balian, Jodhi Wilson, Adam Edwards, Timothy England, Amanda Hedstrom, Elizabeth Bedford, Margaret Harper, Elina Melikyan, Wendy Abbott, Kashmira Subramanian, Marie Goldsworthy, Meena Srinivasan, Angela Yeomans, Denise Donaldson, Frances Hurford, Riquella Chapman, Sana Shahzad, Owen David, Nicki Motherwell, Louise Tonks, Rachel Young, Usman Ghani, Indranil Mukherjee, Dipankar Dutta, Mudhar Obaid, Pauline Brown, Fiona Davis, Deborah Ward, Jennifer Turfrey, Bethan Cartwright, Bilal Topia, Judith Spurway, Kayleigh Collins, Rehana Bakawala, Chloe Hughes, Susan Oconnell, Linda Hill, Kausik Chatterjee, Tim Webster, Syed Haider, Pamela Rushworth, Fiona Macleod, Arumugam Nallasivan, Charlotte Perkins, Edel Burns, Sandra Leason, Tom Carter, Samantha Seagrave, Eman Sami, Lisa Armstrong, Syed Naseem Naqvi, Muhammad Hassan, Sharron Parkinson, Samantha Mawer, Gillian Darnbrook, Carl Booth, Brigid Hairsine, Matthew Smith, Sue Williamson, Fiona Farquhar, Bernard Esisi, Tim Cassidy, Gavin Mankin, Beverley Mcclelland, Maria Bokhari, David Sproates, Elliot Epstein, Steve Hurdowar, Ruth Blackburn, Nazran Sukhdeep, Saika Razak, Khalid Osman, Amina Hashmi, Natasha Upton, Frances Harrington, Gillian Courtauld, Christine Schofield, Linda Lucas, Katja Adie, Kirsty Bond, Abhijit Mate, Jo Skewes, Ali James, Carolyn Brodie, Matthew Johnson, Linda Allsop, Emma Driver, Karina Harris, Mark Drake, Sam Ellis, Bev Maund, Emma Thomas, Kimberley Moore, Matthew Burn, Adam Hamilton, Shageetha Mahalingam, Amulya Misra, Farrah Reid, Adrienne Benford, Derek Hilton, Lorraine Hazell, Keziah Ofori, Anne Louise Thomas, Moncy Mathew, Sonia Dayal, Iona Burn, Kenneth Fotherby, Karla Jennings-Preece, Angela Willberry, Debbie Morgan, Donna Butler, Gurminder Sahota, Kelly Kauldhar, Nasar Ahmad, Angela Stevens, Saugata Das, David Bruce, Yogish Pai, Khin Nyo, Lynsey Stephenson, Richard Nendick, Gill Rogers, Mahesh Dhakal, Sofia Dima, Ellen Brown, Susan Clayton, Penny Gamble, Muhammad Naeem, Rachel Hayman, Rachel Burnip, Philip Earnshaw, David Hargroves, Barbara Ransom, Hannah Rudenko, Ibrahim Balogun, Kirsty Griffiths, Kim Mears, Tom Webb, Linda Cowie, Tessa Hammond, Audrey Thomson, Daniela Ceccarelli, Navraj Chattha, Eva Beranova, Anna Verrion, Andrew Gillian, Natasha Schumacher, Anna Bahk, Susannah Walker, Vera Cvoro, Katrina Mccormick, Nicola Chapman, Susan Pound, Rebecca Cain, Sean Mcauley, Mandy Couser, Maria Simpson, Athan Tachtatzis, Khalil Ullah, Don Sims, Rachael Jones, Jonathan Smith, Rebecca Tongue, Mark Willmot, Claire Sutton, Edward Littleton, Jattinder Khaira, Susan Maiden, James Cunningham, Carole Green, Yin-May Chin, Michelle Bates, Katherine Ahlquist, Ingrid Kane, Joanna Breeds, Tenesa Sargent, Laura Latter, Alexandra Pitt Ford, Nicola Gainsborough, Tom Levett, Philip Thompson, Emma Barbon, Angela Dunne, Simon Hervey, Suzanne Ragab, Tracy Sandell, Christine Dickson, Judith Dube, Sharon Power, Nick Evans, Beverley Wadams, Savina Elitova, Beth Aubrey, Tatiana Garcia, James Mcilmoyle, Carol Jeffs, Christina Dickinson, Anis Ahmed, Sanjeev Kumar, Julie Frudd, Charlotte Armer, Andrew Potter, Stacey Donaldson, Joanne Howard, Kirsty Jones, Saikat Dhar, David Collas, Saul Sundayi, Lynn Denham, Deepali Oza, Elaine Walker, James Cunningham, Mohit Bhandari, Sissy Ispoglou, Rachel Evans, Kamel Sharobeem, Elaine Walton, Steven Shanu, Anne Hayes, Jennifer Howard-Brown, Steven Billingham, Nic Weir, Vanessa Pressly, Emma Wood, Lucy Sykes, Gabriella Howard, Holly Burton, Pam Crawford, Shuna Egerton, Sue Evans, Jasmine Hakkak, Janet Andrews, Rebecca Lampard, Christopher Allen, Ashleigh Walters, Rasha Said, James Richard Marigold, Sau-Mon Tsang, Robyn Creeden, Chloe Cox, Simon Smith, Imogen Gartrell, Fiona Smith, Colin Jenkins, Joanna Pryor, Andrew Hedges, Fiona Price, Linda Moseley, Lily Mercer, Claire Hughes, Diane Mcgowan, Abul Azim, Julie White, Milena Krasinska-Chavez, Shaun Chaplin, James Curtis, Deepwant Singh, Javed Imam, Anne Nicolson, Sajid Alam, Simon Whitworth, Lisa Wood, Elizabeth Warburton, Siobhan Kelly, Joanne Mcgee, Hugh Markus, Denish Chandrasena, Derek Hayden, Juliana Sesay, Helen Hayhoe, Mark Bolton, Jane Macdonald, Jenny Mitchell, Charlotte Farron, Elaine Amis, Diana Day, Ainsley Culbert, Ailene Espanol, Niamh Hannon, Dominic Handley, Sarah Finlay, Sarah Crisp, Lynne Whitehead, Jobbin Francis, Janice Oconnell, Emily Osborne, Rod Beard, Ramesh Krishnamurthy, Langanani Mokoena, Naweed Sattar, Min Myint, Michelle Edwards, Andrew Smith, Paul Corrigan, Anthony Byrne, Joanne Blackburn, Caroline Mcghee, Amanda Smart, Malcolm Macleod, Fiona Donaldson, Claire Copeland, Jill Wilson, Rhona Scott, Paul Fitzsimmons, Paula Lopez, Mark Wilkinson, Aravindakshan Manoj, Penelope Cox, Leona Trainor, Glyn Fletcher, Lisa Denny, Karen Kavanagh, Hannah Allsop, Hedley Emsley, Sulaiman Sultan, Alison Mcloughlin, Benjamin Walmsley, Louise Hough, Shakeel Ahmed, Donna Doyle, Bindu Gregary, Sonia Raj, Kirubananthan Nagaratnam, Neelima Mannava, Nyla Haque, Norma Shields, Kate Preston, Geraldine Mason, Kirsty Short, Gemma Lumsdale, Giulia Uitenbosch, Ugnius Sukys, Stacey Valentine, David Jarrett, Kerry Dodsworth, Mary Wands, Nisa Khan, Jane Tandy, Catrin Watkinson, Wendy Golding, Rebecca Butler, Max Williams, Yasmin Davies, Keith Yip, Claire James, Anne Suttling, Aditya Maney, Giles Edward Gamble, Adam Hague, Bethan Charles, Sujata Blane, Beatriz Duran, Caroline Lambert, Katherine Stagg, Robert Whiting, Jane E Homan, Sarah Brown, Malik Hussain, Miriam Harvey, Libby Graham, Leanne Foote, Catherine Lane, Liz (Joan) Kemp, Joy Rowe, Helen Durman, Jayne Foot, Lucy Brotherton, Nicholas Hunt, Corinne Pawley, Alison Whitcher, Patrick Sutton, Susan Mcdonald, Denys Pak, Alison Wiltshire, Jennifer Jagger, Anthony K Metcalf, Gail Louise Healey, Joyce Balami, Clare Marie Self, Melissa Crofts, Annie Chakrabarti, Chit Hmu, Garth Ravenhill, Charmaine Grimmer, Thandar Soe, Jocelyn Keshet-Price, Margaret Langley, Ian Potter, Pui-Lin Tam, Mary Joan Macleod, Patricia Cooper, Michael Christie, Janice Irvine, Faye Annison, David Christie, Celia Meneses, Amber Johnson, Anu Joyson, Sandra Nelson, Vicky Taylor, John Reid, Rebecca Clarke, Jacqueline Furnace, Heather Gow, Youssif Abousleiman, Tania Beadling, Sally Collins, Stuart Jones, Jessica Purcell, Samantha Bloom, Shelly Goshawk, Marcial Landicho, Sivatharshini Sangaralingham, Yasmin Begum, Sherree Mutton, Elangovan Munuswamy Vaiyapuri, Jane Allen, Jemma Lowe, Martin Hughes, Ivan Wiggam, Sarah Cuddy, Suzanne Tauro, Brian Wells, Azlisham Mohd Nor, Charlotte Eglinton, Nicola Persad, Maggie Kalita, Stuart Weatherby, Claire Brown, Adrian Pace, Daniel Lashley, Mike Marner, Marie Weinling, Natasha Wilmshurst, Darren Waugh, Anna Mucha, Alex Shah, John Baker, Jacqueline Westcott, Richard Cowan, Evangelos Vasileiadis, Samira Mumani, Anthea Parry, Cathy Mason, Melinda Holden, Katerina Petrides, Tomoko Nishiyama, Hina Mehta, Manju Krishnan, Dacey Lynne, Lisa Thomas, Connor Lynda, Catherine Hughes, Clare Clements, Rhys Williams, Tal Anjum, Storton Sharon, Susan Tucker, Paul Jones, Deanne Colwill, Helen Thompson Jones, Dinesh Chadha, Mark Fairweather, Deborah Walstow, Rosanna Fong, Stuart Johnston, Christine Almadenboyle, Sarah Ross, Shona Carson, Priya Nair, Emily Tenbruck, Mairi Stirling, Aparna Pusalkar, Hannah Beadle, Kelly Chan, Puneet Dangri, Asaipillai Asokanathan, Anita Rana, Sunita Gohil, Mark Massyn, Prabhu Aruldoss, Angela Cook, Karen Crabtree, Sura Dabbagh, Toby Black, Caroline Clarke, Denise Mead, Ruth Fennelly, Alpha Anthony, Linda Nardone, Victoria Dimartino, Michele Tribbeck, David Broughton, Dinesh Tryambake, Lynn Dixon, Agnieszka Skotnicka, Jane Thompson, Sarah Whitehouse, Andrew Sigsworth, Jason Wong, Arunkumar Annamalai, Julie Pagan, Brendan Affley, Caroline Sunderland, Lynda Goldenberg, Atif Khan, Peter Wilkinson, Raad Nari, Lucy Abbott, Emma Young, Amritpal Shakhon, Sally Lock, Jack Stewart, Rita Pereira, Margaret Dsouza, Sally Dunn, Anne-Marie Mckenna, Nina Cron, Michelle Kidd, Grace Hull, Kerry Bunworth, Graham Drummond, Karim Mahawish, Nicola Hayes, Lynne Connell, Jennifer Simpson, Helen Penney, Shuja Punekar, Joanne Nevinson, William Wareing, Jacqueline Ward, Richard Greenwood, Duncan Austin, Azra Banaras, Carolin Hogan, Thomas Corbett, Nnebuife Oji, Emma Elliott, Maria Brezitski, Nathalie Passeron, Laura Howaniec, Caroline Watchurst, Krishna Patel, Renuka Erande, Rahi Shah, Nabarun Sengupta, Maria Metiu, Celia Gonzalez, Sarah Funnell, Jordi Margalef, Gillian Peters, Indra Chadbourn, Ramachandran Sivakumar, Rajesh Saksena, Jane Ketley-O'donel, Richard Needle, Elaine Chinery, Alison Wright, Sue Cook, Joseph Ngeh, Harald Proeschel, Paige Cook, Pauline Ashcroft, Simon Sharpe, Stephanie Jones, Damian Jenkinson, Deborah Kelly, Holly Bray, Gunaratnam Gunathilagan, Kirsty Griffiths, Kim Mears, Andrew Gillian, Sally Jones, Sorrell Tilbey, Saidu Abubakar, Eva Beranova, Joseph Vassallo, Dee Leonard, Lucy Orrell, Aziz Hasan, Asif Khan, Sulmaaz Qamar, Susan Graham, Emma Hewitt, Jennifer Awolesi, Muhammad Haque, Alissa Kent, Elizabeth Bradshaw, Martin Cooper, Inez Wynter, Anoja Rajapakse, Joumana Janbieh, Abu M Nasar, Lynne Wade, Linda Otter, Steve Haigh, Jamie-Rae Burgoyne, Rebecca Boulton, Andrew Boulton, Rayessa Rayessa, Emma Clarkson, Horne Rhian, Amy Fleming, Kim Mitchelson, Vicki Lowthorpe, Ahmed Abdul-Hamid, Phil Jones, Claire Duggan, Abigail Hynes, Emma Nurse, Syed Abid Raza, Sarah Jones, Udaya Pallikona, Bleddyn Edwards, Geraint Morgan, Kirsty Dennett, Helen Tench, Ronda Loosley, Toby Trugeon-Smith, Rhian Jones, Richard Williams, Donna Robson, Sunanda Mavinamane, Sanjeevi Meenakshisundaram, Lalitha Ranga, Sharon Dealing, Andrew Hill, Margaret Hargreaves, Tom Smith, Julie Bate, Linda Harrison, Ramanathan Kirthivasan, Emma Cannon, Joanne Topliffe, Rebecca Keskeys, Sarah Williams, Fiona Mcneela, Frances Cairns, Thomas James, Amanda Lyle, Sheela Shah, George Zachariah, Lauren Fergey, Susan Smolen, Lucy Cooper, Elizabeth Bohannan, Siddiq Omer, Sageet Amlani, Nadia Hunter, Melissa Hawkes-Blackburn, Giosue Gulli, Alice Peacocke, Justine Amero, Maria Burova, Ottilia Speirs, Steph Levy, Lynda Francis, Susan Holland, Sean Brotheridge, Helen Lyon, Christine Hare, Samantha Jackson, Lorraine Stephenson, Samer Al Hussayni, James Featherstone, Agness Bwalya, Arun Singh, M N Goorah, Jamie Walford, Angela Bell, Christine Kelly, Darren Rusk, Deborah Sutton, Farzana Patel, Stephen Duberley, Kathryn Hayes, Lorraine Hunt, Ahmed El Nour, Poppy Cottrell, Jax Westmoreland, Sacha Honour, Chloe Box, Paul Wood, Monica Haritakis, Simon Dyer, Lynne Brown, Kerry Elliott, Emma Temlett, John Paterson, Rosie Furness, Shelli Young, Enoch Orugun, Chris Brewer, Sarah Thornthwaite, Hannah Crowther, Rachel Glover, Moe Sein, Kashif Haque, Elspeth Gibson, Sam Wong, Karen Rotchell, Karen Burton, Lisa Brookes, Linda Bailey, Dee Leonard, Chris Lindley, Abbi Murray, Karen Waltho, Maureen Holland, Pradeep Kumar, Purnima Harlekar, Laura Booth, Charlotte Culmsee, Jade Drew, Mohammad Khan, Nicola Mackenzie, Carmel Thomas, Jane Ritchie, James Barker, Michael Haley, Donna Cotterill, Lynne Lane, Christine Little, Dawn Simmons, Glenn Saunders, Harvey Dymond, Sarah Kidd, Rachel Warinton, Yara Neves-Silva, Branimir Nevajda, Michael Villaruel, Udayaraj Umasankar, Seema Patel, Anna Man, Natasha Christmas, Ravi Rangasamy, Richard Ladner, Georgina Butt, Wilson Alvares, Narasimha Gadi, Michael Power, Belinda Wroath, Kevin Dynan, David Wilson, Sarah Crothers, Catherine Leonard, Samantha Hagan, Geraldine Douris, Djamil Vahidassr, Alastair Thompson, Brian Gallen, Shirley Mckenna, Collette Edwards, Clare Mcgoldrick, Murdi Bhattad, Khalil Kawafi, Deborah Morse, Patricia Jacob, Lisa Turner, Narayanamoorti Saravanan, Linda Johnson, Sadie Humphrey, Robert Namushi, Ramesh Patel, Jemma Mclaughlin, Paul Omahony, Esther Osikominu, Chukwuka Orefo, Chisha Mcdonald, Val Jones, Esther Makanju, Tabindah Khan, Grace Appiatse, Helena Stone, Martia Augustin, Alicia Wardale, Maqsud Salehin, Duncan Bailey, Luciano Garcia-Alen, Latheef Kalathil, Sarah Tinsley, Taya Jones, Kelly Amor, Andrew Ritchings, Emma Margerum, Jane Horton, Richard Miller, Nireekshana Gautam, Julie Meir, Amaryl Jones, Janet Putteril, Mirella Lepore, Esther Makanju, Rachel Gallifent, Laura-Louise Arundell, Catherine Mcredmond, Alicia Goulding, Vivek Nadarajan, Julia Laurence, Su Fung Lo, Sabina Melander, Paul Nicholas, Elizabeth Woodford, Gillian Mckenzie, Vietland Le, Jacolene Crause, Robert Luder, Maneesh Bhargava, Rahi Shah, Girish Bhome, Venetia V Johnson, Dara Chesser, Hayley Bridger, Elodie Murali, Jon Scott, Susan Morrison, Amy Burns, Julie Graham, Madeline Duffy, Khalid Ali, Tenesa Sargent, Emma Pitcher, Jane Gaylard, Julie Newman, Sunil Punnoose, Sarah Besley, Kirtan Purohit, Amy Rees, Mark Davy, Osman Chohan, Muhammad Fozan Khan, Rachel Walker, Vicky Murray, Charlotte Bent, Susan Oakley, Adrian Blight, Cassilda Peixoto, Suzanne Jones, Gaybrielle Livingstone, Fiona Butler, Sally Bradfield, Laura Gordon, Jenneke Schmit, Anika Wijewardane, Tineke Edmunds, Rebecca Wills, Catherine Medcalf, Lucia Argandona, Larissa Cuenoud, Hanna Hassan, Esther Erumere, Aidan Ocallaghan, Patrick Gompertz, Ozlem Redjep, Grace Auld, Laura Howaniec, Anna Song, Tillana Tarkas, Hashim Kabash, and Rumbi Hungwe

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.GBD 2015 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet. 2016;388:1545–1602. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31678-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chollet F, Tardy J, Albucher JF. Fluoxetine for motor recovery after acute ischaemic stroke (FLAME): a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2011;10:123–130. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70314-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mead GE, Hsieh CF, Lee R. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) for stroke recovery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;11 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009286.pub2. CD009286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schambra H, O'Dell MW. Should this patient with ischemic stroke receive fluoxetine? PM R. 2015;7:1294–1299. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2015.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mead G, Hackett ML, Lundstrom E, Murray V, Hankey GJ, Dennis M. The FOCUS, AFFINITY and EFFECTS trials studying the effect(s) of fluoxetine in patients with a recent stroke: a study protocol for three multicentre randomised controlled trials. Trials. 2015;16:369. doi: 10.1186/s13063-015-0864-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Graham C, Lewis S, Forbes J. The FOCUS, AFFINITY and EFFECTS trials studying the effect(s) of fluoxetine in patients with a recent stroke: statistical and health economic analysis plan for the trials and for the individual patient data meta-analysis. Trials. 2017;18:627. doi: 10.1186/s13063-017-2385-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Altman DG, Bland JM. Treatment allocation by minimisation. BMJ. 2005;330:843. doi: 10.1136/bmj.330.7495.843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bruno A, Shah N, Lin C. Improving modified Rankin scale assessment with a simplified questionnaire. Stroke. 2010;41:1048–1050. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.571562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Counsell C, Dennis M, McDowall M, Warlow C. Predicting outcome after acute stroke: development and validation of new models. Stroke. 2002;33:1041–1047. doi: 10.1161/hs0402.105909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke rt-PA Stroke Study Group Tissue plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1581–1587. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199512143332401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.White R, Bradnam V. 2nd edn. Pharmaceutical Press; London: 2010. Handbook of drug administration via enteral feeding tubes. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bruno A, Akinwuntan AE, Lin C. Simplified modified Rankin scale questionnaire: reproducibility over the telephone and validation with quality of life. Stroke. 2011;42:2276–2279. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.613273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dennis M, Mead G, Doubal F, Graham C. Determining the modified Rankin score after stroke by postal and telephone questionnaires. Stroke. 2012;43:851–853. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.639708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Duncan PW, Wallace D, Lai SM, Johnson D, Embretson S, Laster LJ. The stroke impact scale version 2.0: evaluation of reliability, validity and sensitivity to change. Stroke. 1999;30:2131–2140. doi: 10.1161/01.str.30.10.2131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Duncan PW, Bode R, Min Lai S, Perera S, Glycine Antagonist in Neuroprotection Americans Investigators Rasch analysis of a new stroke specific outcome scale: the Stroke Impact Scale. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2003;84:950–963. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(03)00035-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Duncan P, Reker D, Horner R. Performance of a mail-administered version of a stroke specific outcome measure, the Stroke Impact Scale. Clin Rehabil. 2002;16:493–505. doi: 10.1191/0269215502cr510oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Duncan P, Reker D, Kwon S. Measuring stroke impact with the stroke impact scale: telephone versus mail administration in veterans with stroke. Med Care. 2005;43:507–515. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000160421.42858.de. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kwon S, Duncan P, Studenski S, Perera S, Lai SM, Reker D. Measuring stroke impact with SIS: construct validity of SIS telephone administration. Qual Life Res. 2006;15:367–376. doi: 10.1007/s11136-005-2292-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoeymans N, Garssen AA, Westert GP, Verhaak PF. Measuring mental health of the Dutch population: a comparison of the GHQ-12 and the MHI-5. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2004;2:23. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-2-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McCabe CJ, Thomas KJ, Brazier JE, Coleman P. Measuring the mental health status of a population: a comparison of the GHQ-12 and the SF-36 (MHI-5) Br J Psychiatry. 1996;169:516–521. doi: 10.1192/bjp.169.4.516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mead GE, Lynch J, Greig CA, Young A, Lewis SJ, Sharpe M. Evaluation of fatigue scales in stroke. Stroke. 2007;38:2090–2095. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.106.478941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mead GE, Graham C, Dorman P, on behalf of UK Collaborators of IST Fatigue after stroke: baseline predictors and influence on survival. Analysis of data from UK Patients Recruited in the International Stroke Trial. PLoS One. 2011;6:e16988. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Herdman M, Gudex C, Lloyd A. Development and preliminary testing of the new five-level version of EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L) Qual Life Res. 2011;20:1727–1736. doi: 10.1007/s11136-011-9903-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bamford J, Sandercock P, Dennis MS, Burn J, Warlow C. Classification and natural history of clinically identifiable subtypes of cerebral infarction. Lancet. 1991;337:1521–1526. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)93206-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Adams HP, Jr, Bendixen BH, Kappelle LJ. Classification of subtype of acute ischemic stroke. Definitions for use in a multicenter clinical trial. TOAST. Trial of ORG 10172 in acute stroke treatment. Stroke. 1993;24:35–41. doi: 10.1161/01.str.24.1.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Whooley MA, Avins AL, Miranda J, Browner WS. Case-finding instruments for depression. Two questions are as good as many. J Gen Intern Med. 1997;12:439–445. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1997.00076.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bray B D, Cloud GC, James MA. Weekly variation in health-care quality by day and time of admission: a nationwide, registry-based, prospective cohort study of acute stroke care. Lancet. 2016;388:170–177. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30443-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.NHS National Services Scotland Scottish Stroke Improvement Programme. 2017 report. https://www.strokeaudit.scot.nhs.uk/Downloads/docs/2017-07-11-SCCA-Report.pdf

- 29.Tsivgoulis G, Katsanos AH, Caso V. Under-representation of women in stroke randomized controlled trials: inadvertent selection bias leading to suboptimal conclusions. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2017;10:241–244. doi: 10.1177/1756285617699588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Salter KL, Foley NC, Zhu L, Jutai JW, Teasell RW. Prevention of poststroke depression: does prophylactic pharmacotherapy work? J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2013;22:1243–1251. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2012.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wadhwa R, Kumar M, Talegaonkar S, Vohora D. Serotonin reuptake inhibitors and bone health: a review of clinical studies and plausible mechanisms. Osteoporosis Sarcopenia. 2017;3:75–81. doi: 10.1016/j.afos.2017.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sansone RA, Sansone LA. Antidepressant adherence: are patients taking their medications? Innov Clin Neurosci. 2012;9:41–46. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The study protocol and statistical analysis plan have been published.5, 6 A fully anonymised trial dataset with individual participant data and a data dictionary will be made available to other researchers after the publication of the full trial report in the Health Technology Assessment journal in 2019. Requests should first be directed to Martin Dennis (Co-Chief Investigator). Written proposals will be assessed by the FOCUS trial team and a decision made about the appropriateness of the use of data. A data sharing agreement will be put in place before any data will be shared.