Abstract

Adherens junctions (AJs), together with tight junctions (TJs), form an apical junctional complex that regulates intestinal epithelial cell-to-cell adherence and barrier homeostasis. Within the AJ, membrane-bound E-cadherin binds β-catenin, which functions as an essential intracellular signaling molecule. We have previously identified a novel protein in the region of the apical junction complex, chloride channel protein-2 (ClC-2), that we have used to study TJ regulation. In this study, we investigated the possible effects of ClC-2 on the regulation of AJs in intestinal mucosal epithelial homeostasis and tumorigenicity. Mucosal homeostasis and junctional proteins were examined in wild-type (WT) and ClC-2 knockout (KO) mice as well as associated colonoids. Tumorigenicity and AJ-associated signaling were evaluated in a murine colitis-associated tumor model and in a colorectal cancer cell line (HT-29). Colonic tissues from ClC-2 KO mice had altered ultrastructural morphology of intercellular junctions with reduced colonocyte differentiation, whereas jejunal tissues had minimal changes. Colonic crypts from ClC-2 KO mice had significantly higher numbers of less-differentiated forms of colonoids compared with WT. Furthermore, the absence of ClC-2 resulted in redistribution of AJ proteins and increased β-catenin activity. Downregulation of ClC-2 in colorectal cells resulted in significant increases in proliferation associated with disruption of AJs. Colitis-associated tumors in ClC-2 KO mice were significantly increased, associated with β-catenin transcription factor activation. The absence of ClC-2 results in less differentiated colonic crypts and increased tumorigenicity associated with colitis via dysregulation of AJ proteins and activation of β-catenin-associated signaling.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY Disruption of adherens junctions in the absence of chloride channel protein-2 revealed critical functions of these junctional structures, including maintenance of colonic homeostasis and differentiation as well as driving tumorigenicity by regulating β-catenin signaling.

Keywords: adherens junction, chloride channel ClC-2, colonic homeostasis, colonic tumorigenicity, colonoids

INTRODUCTION

The gastrointestinal epithelium forms the body’s largest interface between biological compartments and allows for the absorption of nutrients while providing a physical barrier to the permeation of pathogens, toxins, and antigens from the luminal environment across the mucosa and ultimately in the circulatory system (17). The intestinal barrier is composed of epithelial cells linked by apical junctional complexes (AJCs), which are formed by tight junctions (TJs) and adherens junctions (AJs) that also establish apical-basal cell polarity (3, 12). The TJ is the most apical component of the AJC acting as a barrier (gate) to the paracellular pathway by regulating passive diffusion of solutes and macromolecules. The AJs, together with TJs, control epithelial cell-to-cell adherence, cell polarization, and barrier function and also play a vital role in the regulation of the actin cytoskeleton, intracellular signaling pathways, and epithelial transcription. The AJC components also have critical functions during intestinal crypt development and differentiation (12, 22).

The chloride channel protein-2 (ClC-2) is expressed in the plasma membranes of epithelial cells in many mammalian tissues (35). The physiological contribution of ClC-2 in the intestine is not completely understood. Recently, however, we have accumulated evidence of an integral role of ClC-2 in the regulation of intestinal barrier function by regulating TJ composition (27, 28), resulting in hastened resealing of the paracellular space in injured murine and porcine tissues (23, 29). For example, in previous studies, we have shown that ClC-2 knockout (KO) mice have retarded recovery of barrier function after small intestinal ischemic injury (29). We have also shown that ClC-2 KO mice are more susceptible to colitis (26) and that the ClC-2 agonist lubiprostone had a preventive effect against colitis associated with enhanced epithelial differentiation (18). Because of the importance of AJs in differentiation, related to β-catenin in particular, we began to question the role of ClC-2 in the regulation AJ stability during colonic homeostasis.

β-Catenin is an essential component of AJ stability at the membrane where it binds to E-cadherin (15, 21, 30). When β-catenin becomes detached from E-cadherin, it accumulates in the cytosol and enters the nucleus, where it interacts with T cell factor-1/lymphoid-enhancing factor-1 (TCF/LEF1) transcription factors to drive transcription of target genes such as axin2, cd44, c-Myc, Ephb2, and Ephb3 (7, 20). A recent study has shown that the β-catenin/E-cadherin complex is more highly expressed in the colon compared with the small intestine (15), suggesting that AJs are more critical to regulation of β-catenin-associated colonic homeostasis than previously recognized. Colonic homeostasis is disrupted in patients with inflammatory bowel disease, which in certain individuals leads to colitis-associated colorectal cancer (CAC). However, the mechanisms for CAC are poorly understood compared with sporadic colorectal cancer, which has a well-defined genetic etiology. Interestingly, abnormal β-catenin expression in the cytosol and nucleus is more prominently linked to E-cadherin in CAC than in sporadic colorectal cancer (1). In this study, we investigated the role of ClC-2 in the regulation of colonic homeostasis and tumorigenicity following experimental colitis. Our findings indicate that the absence of ClC-2 results in less differentiated colonic crypts and increased tumorigenicity following colitis via dysregulation of the AJ E-cadherin/β-catenin complex, associated with β-catenin-initiated TCF/LEF1 signaling activation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals and induction of colitis-associated colorectal tumor.

Studies were approved by the North Carolina State University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Breeding pairs of heterozygous mice (ClC-2+/−) were a kind gift of Dr. James E. Melvin (25) (University of Rochester, Rochester, NY) and bred in-house. ClC-2 KO and wild-type (WT) mice (8–16 wk age) were used in this study. The mice were given bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU, ip) 24 h before being euthanized and analyzed. Procedures for induction of colitis-associated tumors by administration of azoxymethane (AOM, A5486;, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and dextran sulfate sodium (DSS, 02160110; MP Biomedicals, Santa Ana, CA) are shown in Fig. 7A. In week 1, mice were injected with AOM (10 mg/kg ip). After 1 wk, 2% DSS was added to the autoclaved drinking water for 5 days followed by 16 days of regular water. This cycle was repeated two times. At the end of the experiments, the mice were given BrdU (ip) 2 h before being euthanized, and the colon was excised and macroscopically and microscopically inspected as previously described (2). Briefly, the colon was removed, flushed with PBS, and opened longitudinally. Gross tumor counts and measurements were conducted using images obtained with a Canon EOS Rebel T2i (Canon, Tokyo, Japan). Microscopic analysis was conducted by a veterinarian and confirmed by an experienced veterinary pathologist for dysplasia on hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained tissues (processed by the North Carolina State College of Veterinary histology laboratory). The term low-grade dysplasia (LGD) was used to refer to preinvasive pedunculated, sessile, or flat plaque-like lesions with simple glandular outlines, without loss of cellular polarity. The term high-grade dysplasia (HGD) was used to refer to adenomas with architectural complexity, increased cytological atypia, and loss of tumor cell polarity (4, 36).

Fig. 7.

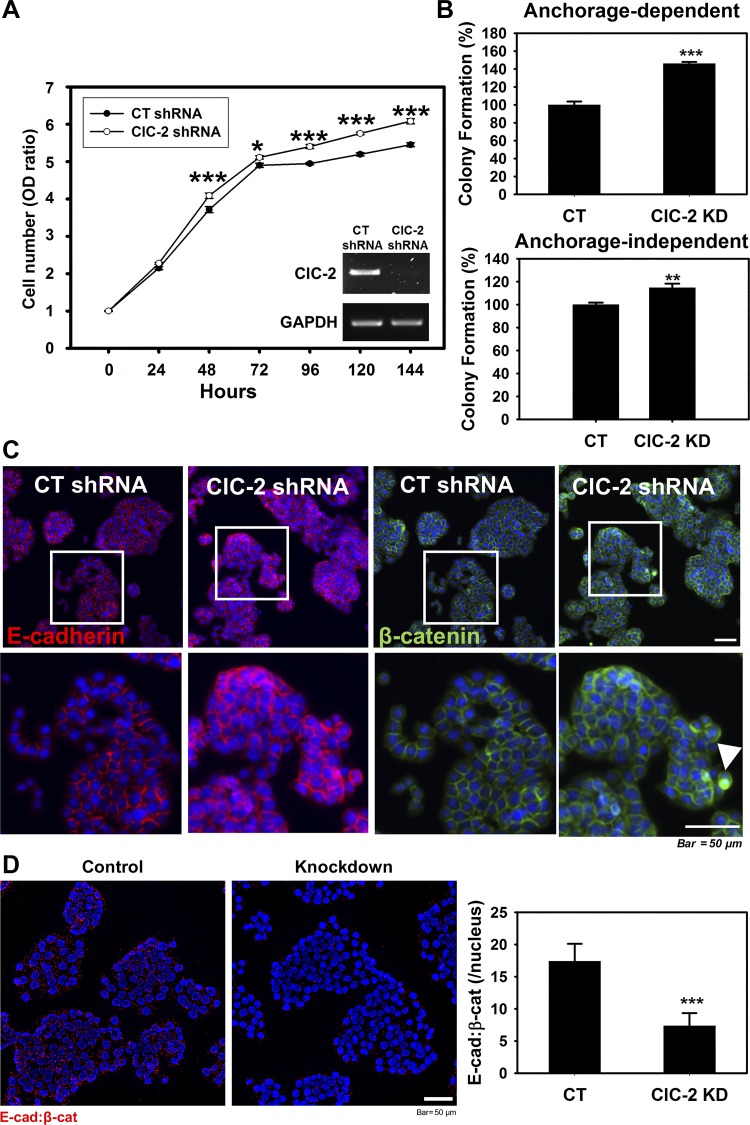

Absence of chloride channel protein-2 (ClC-2) resulted in increased in vitro tumorigenicity and disrupted adherens junctions (AJ) proteins in HT-29 colon cancer cells. A: equal numbers of control (CT) and ClC-2 short-hairpin RNA (shRNA) cells were plated on a 96-well plate. Cell proliferation was monitored with the cell counting kit-8 (CCK-8) assay at different time points. Downregulated ClC-2 significantly increased HT-29 cell proliferation. B: in vitro tumorigenicity of the CT and ClC-2 shRNA cells was determined by a colony formation assay assessing anchorage-dependent and -independent cell populations. The tumorigenicity of ClC-2 shRNA cells was significantly increased compared with CT cells. C: ClC-2 knockdown induced disruption of AJ proteins E-cadherin and β-catenin. Arrowhead, nuclear distribution of β-catenin. D: proximity ligation assay (PLA) showing the interaction (red dots) between E-cadherin and β-catenin in ClC-2 shRNA cells was significantly reduced compared with ClC-2 wild type (WT). Data are presented as means ± SE. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.01 vs. CT shRNA, Student’s t-test.

Transmission electron microscopy.

Small intestinal and colonic tissues were excised, trimmed to 1 mm3, immediately placed in cold modified Karnovsky’s solution (2% paraformaldehyde, 2.5% glutaraldehyde), and held at 4°C. All samples were processed with three 30-min washes of cold 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer (pH 7.4) followed by postfixation for 1 h in 2% OsO4 in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer (pH 7.4), on ice and in the dark. Samples were then rinsed in three more changes of buffer as mentioned above, followed by dehydration in a graded ethanol series (30, 50, 70, 95, and 100% × 3 changes), warming to room temperature in 100% ethanol. Samples were infiltrated and embedded in Spurr’s resin (21230; Ladd Research, Williston, VT) and sectioned at 80 nm thickness on a Leica UC6rt ultramicrotome (Leica Microsystems, Buffalo Grove, IL). Sections were stained with 4% aqueous uranyl acetate and Reynold’s lead citrate and imaged with a JEOL JEM-1200EX transmission electron microscope (TEM; JEOL, Peabody MA). Images were captured using a Gatan ES1000 camera system using Digital Micrograph software (Gatan, Pleasanton, CA).

Immunohistochemical and Immunofluorescence analyses.

Measurements of crypts and villi were performed using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD). Briefly, 10–20 randomly selected colonic crypts were measured from each H&E-stained section to make n = 1. All measurements were performed in a blinded fashion. Immunohistochemistry for BrdU (proliferating cells, 1:40), carbonic anhydrase II (CAII; for mature colonocytes, 1:250), and chromogranin A (CgA; for enterochromaffin cells, 1:1,000) in murine intestinal tissues was performed by standard methods. Heat-activated antigen retrieval was performed in sodium citrate buffer (pH 6). Paraffin sections were deparaffinized and rehydrated. Endogenous peroxidase activity was quenched by incubation in 3% H2O2 in methanol for 10 min. After blocking in the Protein Block Serum-Free (X0909; DakoCytomation, Carpinteria, CA), the sections were incubated in primary antibodies as follows: rat anti-BrdU (ab6326; Abcam, Cambridge, MA), goat anti-CAII, and rabbit anti-CgA (20086; ImmunoStar, Hudson, WI). After washing, the EnVision system (DakoCytomation) was used to reveal the reaction. After being washed, slides were developed for 5 min with 3,3′-diaminobenzindine chromogen and counterstained with hematoxylin. Intact and correctly oriented crypts were randomly analyzed for BrdU-, CAII-, or CgA-positive cells among 10–20 crypts from each mouse to make n = 1. The results were calculated as the percentage of positive cells within the total number of crypt epithelial cells. WT and ClC-2 KO mice sections were incubated with Alcian blue solution (1% wt/vol Alcian blue, 8GX in 3% vol/vol acetic acid, pH 2.5) and washed with deionized water (diH2O). Sections were counterstained with nuclear fast red (0.1% wt/vol nuclear fast red, 5% wt/vol aluminum sulfate in diH2O). Slides were dehydrated and mounted. Goblet cell numbers were quantified from 10 to 20 randomly selected crypts from each mouse.

Intestinal tissue cryosections from WT and ClC-2 KO mice were fixed for 10 min with cold acetone at −20°C. HT-29 cells were fixed for 10 min with cold methanol at −20°C. Immunostaining was performed using primary antibodies, and Cy3- or FITC-conjugated anti-immunoglobulin G was used as a secondary antibody (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). After nuclear staining by DAPI (Invitrogen), slides were mounted in fluorescent mounting media (DakoCytomation) and examined with an Olympus IX83 Inverted Motorized Microscope with cellSens software (Olympus, Shinjuku, Tokyo, Japan). The following primary antibodies were used: E-cadherin (3195, 1:500) and β-catenin (8480, 1:250) (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, CO) and zonula occludens-1 (ZO-1, 61-7300, 1:250), occludin (33-1500, 1:50), and claudin-1 (51-9000, 1:500) (Invitrogen). Nuclear β-catenin was evaluated using ImageJ colocalization threshold to show the percentage of colocalized β-catenin (red) intensity in DAPI (blue)-stained nucleus.

Gel electrophoresis and Western blotting.

Small intestinal and colonic tissues from WT and ClC-2 KO mice were lysed in T-PER Tissue Protein Extraction Reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) and centrifuged. Supernatants were quantified with a BCA protein assay kit (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL). Proteins were separated on 4–12% Bis-Tris gels with XT MOPS SDS running buffer (both, Bio-Rad). After protein transfer to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane, the membranes were probed using anti-ClC-2 (1:200, ACL-002; Alomone Laboratories, Jerusalem, Israel) and anti-β-actin (1:20,000, ab8227; Abcam) antibodies. Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies were used (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX).

Real-time PCR.

Total RNA was isolated from colonic tissues from WT and ClC-2 KO mice or HT-29 cells using an RNeasy kit (74104; Qiagen, Vanlecia, CA) and quantified spectrophotometrically using NanoDrop 2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Equal amounts of RNA were used for complementary DNA synthesis (17088690, iScript cDNA Synthesis Kit; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). Real-time PCR was performed using iTaq Universal SYBR Green Supermix (1725120; Bio-Rad Laboratories), the Applied Biosystems QuantStudio 6 Flex Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosciences, Carlsbad, CA), and PCR primers obtained from Integrated DNA Technology (Coralville, IA) (Table1)

Table 1.

Real-time PCR primer design

| Gene | Accession No. | Forward Primer (5′→3′) | Reverse Primer (5′→3′) | Product Size, bp |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZO-1 | NM_009386.2 | GCCGCTAAGAGCACAGCAA | TCCCCACTCTGAAAATGAGGA | 134 |

| Ocln | NM_008756 | TTGAAAGTCCACCTCCTTACAGA | CCGGATAAAAAGAGTACGCTGG | 129 |

| Cldn1 | NM_016674 | AGCACCGGGCAGATACAGT | AGGAGTCGAAGACTTTGCACT | 90 |

| Cdh1 | NM_009864 | TCGGAAGACTCCCGATTCAAA | CGGACGAGGAAACTGGTCTC | 95 |

| Ctnnb1 | NM_001165902 | ATGGAGCCGGACAGAAAAGC | CTTGCCACTCAGGGAAGGA | 108 |

| Axin2 | NM_015732 | TGACTCTCCTTCCAGATCCCA | TGCCCACACTAGGCTGACA | 105 |

| Cd44 | NM_001039151 | TCGATTTGAATGTAACCTGCCG | CAGTCCGGGAGATACTGTAGC | 78 |

| c-Myc | BC138931.1 | ATGCCCCTCAACGTGAACTTC | GTCGCAGATGAAATAGGGCTG | 78 |

| Ephb2 | NM_010142 | GCCGTGGAAGAAACCCTGAT | GTTCATGTTCTCGTCGTAGCC | 111 |

| Ephb3 | NM_010143 | CATGGACACGAAATGGGTGAC | GCGGATAGGATTCATGGCTTCA | 103 |

| β-Actin | NM_007393 | GGCTGTATTCCCCTCCATCG | CCAGTTGGTAACAATGCCATGT | 154 |

ZO-1, zonula occludens-1.

In situ proximity ligation assay.

The DuoLink proximity ligation assay (PLA, A5486; Sigma-Aldrich) was used to detect interactions between E-cadherin and β-catenin. Intestinal tissue cryosections from WT and ClC-2 KO mice were fixed for 10 min with cold acetone at −20°C, and HT-29 cells were fixed for 10 min with cold methanol at −20°C. The tissues and cells were immunolabeled with the primary antibodies anti-E-cadherin (3195, 1:250) and anti-β-catenin (8480, 1:100) (Cell Signaling Technology). The secondary antibodies with attached PLA probes were supplied in the DuoLink kit. The PLA images were captured using an Olympus IX83 Inverted Motorized Microscope with cellSens software. Visualization of PLA dots within the crypt were quantified using ImageJ software and normalized by the number of nuclei.

Mouse colonic crypt isolation and colonoid culture.

Mouse colonic crypt isolation and 3-D crypt culture were performed using the IntestiCult system (06005; STEMCELL Technologies, Vancouver, BC, Canada) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, colonic tissues of ClC-2 WT and KO mice were dissected and washed several times in PBS. The colonic fragments were then incubated for 20 min with Gentle Cell Dissociation Reagent at room temperature. The crypts were then isolated through centrifugation, counted, and resuspended in a 50:50 mixture of Matrigel (356230; Corning, Corning, NY) and IntestiCult Organoid Growth Medium (complete media). A 50-µl droplet of the suspension was gently placed in the center of prewarmed 12-well culture plate wells, creating a dome containing 150 crypts/well. The domes were solidified at 37°C for 5 min, and the wells were then flooded with 750 µl of complete media. Morphological analyses and immunofluorescence (IF) assays were performed after days 0 and 6 using an Olympus IX83 Inverted Motorized Microscope and ImageJ. Each well was scanned with multiple depths of focus. Images were then used to determine the number of spheroids and buds. The growth of crypts was determined by calculating the number of colonoids growing on day 6 compared with the total number of crypts on day 0 and expressed as a percentage. Area was determined by drawing a freehand circumference using ImageJ software. The growth percentage and area were calculated using cellSens software.

Cell culture and transfection.

The HT-29 human colorectal cancer cell line was obtained from American Type Culture Collection (HTB-38; Manassas, VA). Persistent knockdown of clcn-2 gene expression using short-hairpin RNA (shRNA) was achieved by transfecting HT-29 cells with lentiviral particles encoding ClC-2 shRNA or control shRNA (catalog nos. sc-42379-V and sc-108080; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Selection of clones for stable expression of shRNA was performed using titrated concentrations of puromycin dihydrochloride (8 mg/ml for initial selection and 3 mg/ml for maintenance, 58-58-2; Invivogen, San Diego, CA). The confirmation of inhibition of ClC-2 expression was performed by reverse transcriptase-PCR, as described previously (27).

Cell proliferation assay.

HT-29 cells were seeded in 96-well culture plates at a density of 5,000 cells/well. Each day for six consecutive days, viable cells were evaluated with the cell counting kit-8 (CCK-8) assay (CK04-01; Dojindo) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. CCK-8 solution was added to the cells in 96-well plates, the plates were incubated at 37°C for 2 h, and the optical density of each well was read at 450 nm using a microplate reader (Bio-Tek, Winooski, VT).

Clonogenic assays.

For the anchorage-dependent clonogenic assay, 500 cells were plated in six-well plates and cultured for 2 wk. After colony formation, colonies were washed with PBS and fixed with 2 ml of 10% neutral buffered formalin solution for 15 min. Colonies were stained with 0.05% (wt/vol) crystal violet in diH2O for 30 min. The plates were washed with tap water and allowed to dry. The counting of the number of colonies was performed and automated using ImageJ software.

The anchorage-independent clonogenic assay was performed using CytoSelect 96-Well Cell Transformation Assay (CBA-130; Cell Biolabs, San Diego, CA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, prewarmed 25 µl of 2× DMEM containing 20% FBS and 25 µl of 1.2% agar solution were mixed and transferred to a well of 96-well plates and then incubated at 4°C for 30 min to the bottom agar layer to solidify. Single cell suspensions were prepared from HT-29 cell culture. Next, 25 µl of single cell suspensions containing the defined number of cells were mixed with 25 µl of 2× DMEM containing 20% FBS and 25 µl of 1.2% agar, and placed on the bottom agar layer. The top agar layers were immediately solidified at 4°C for 10 min to avoid false-positive signals derived from gravity-induced adjacent cells in the agar medium. After the addition of 100 µl of DMEM containing 10% FBS to each well, the plates were incubated for 14 days at 37°C and 5% CO2. The medium was changed every 2–3 days. Colonies were lysed and quantified with CyQuant GR dye using a fluorometer equipped with a 485/520 nm filter set (microplate reader; Bio-Tek).

Analysis of ClC-2 expression in patients with colorectal cancer.

For ClC-2 expression analysis in colorectal tumors, we applied two data sets {colon adenocarcinoma and rectum adenocarcinoma [The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA)]} using OASIS (Pfizer, New York, NY) followed the provider’s guidance. Microarray and RNA-Seq expression of ClC-2 were evaluated in both colon and rectum adenocarcinoma, respectively. Downloaded raw data were combined and plotted using Sigmaplot (SYSTAT Software, San Jose, CA).

Statistical analysis.

Differences between groups were tested with a Student’s t-test (continuous data) or Fisher’s exact test (distribution of data). All statistical analyses were performed by using IBM SPSS Statistics 22 (IBM, North Castle, NY). P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Data are presented as means ± SE. All authors had access to the study data and reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

RESULTS

The absence of ClC-2 alters ultrastructural morphology of intercellular junctions in colon but not small intestine.

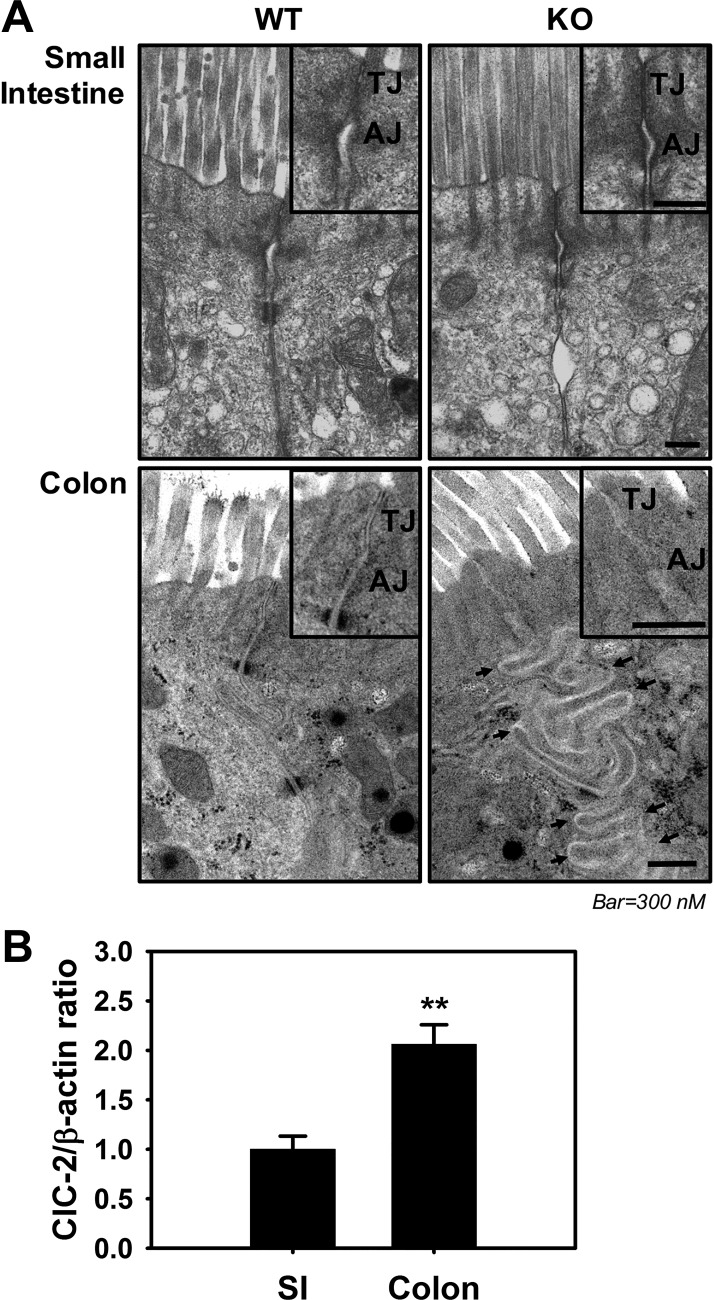

Our previous research in the small intestine demonstrated that the absence of ClC-2 resulted in slight alterations in apical junctional ultrastructure, including less well-defined lateral membranes and narrowed TJs (28). However, we had not previously investigated the role of ClC-2 in ultrastructural morphology of AJCs in the colon. In the colon, ClC-2 is a protein that has been shown to be principally expressed in the epithelium, and its function has been assessed using knockout mice in which there is a confirmed loss of ClC-2 in the epithelium (6, 26). To find out whether there were any ultrastructural changes in ClC-2 KO colon, we performed TEM analyses. These TEM analyses revealed apical-lateral membranes and junctional structures that were less well defined and poorly apposed in ClC-2 KO colon compared with well-defined closely apposed lateral membranes in WT colon. Of particular interest, ClC-2 KO colon showed markedly tortuous folding (Fig. 1A) of the epithelial lateral membranes compared with WT. In contrast, there were no such differences noted in the small intestine (Fig. 1A). Because of the distinct differences in colon compared with small intestine, the expression of ClC-2 was evaluated using Western blotting. This revealed that the expression of ClC-2 was indeed significantly increased in the colon compared with the small intestine (Fig. 1B). Collectively, these data indicated that the ClC-2 has more critical functions in regulation of colonic homeostasis than that of small intestine, possibly related to differences in expression.

Fig. 1.

Role of chloride channel protein-2 (ClC-2) in ultrastructural morphology of intercellular junctions in colon. A: to evaluate the role of ClC-2 in ultrastructural morphology of intercellular junctions, images were taken using a JEOL JEM-1200EX transmission electron microscope (TEM) and Gatan ES1000 camera system of intestines from ClC-2 wild-type (WT) and knockout (KO) mice. In small intestine (top), there is no dramatic morphological change between two groups compared with colon. In WT colon, tight junctions (TJs) and adherens junctions (AJs) appeared to be more electron dense and were more closely apposed compared with ClC-2 KO colon, in which TJs and AJs were less well defined and lateral epithelial membranes were tortuously folded (black arrows) (n = 2). B: mucosa from small intestine (SI) and colon were studied for expression of ClC-2 by Western blotting. Densitometry analysis was performed to quantify expression using β-actin as a loading control. Data are presented as means ± SE (n = 4). **P < 0.01 vs. WT, Student’s t-test.

Disruption of AJ proteins in ClC-2 KO colonic tissue results in elevated β-catenin nuclear distribution.

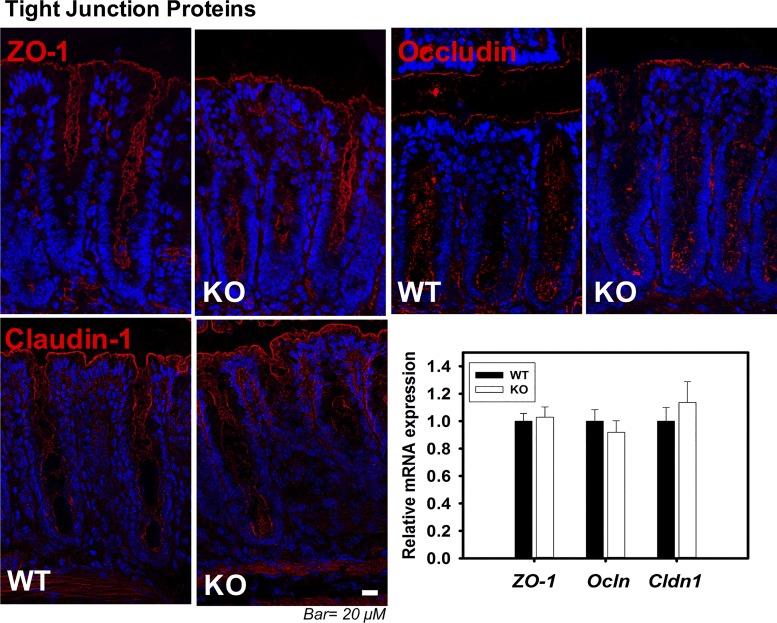

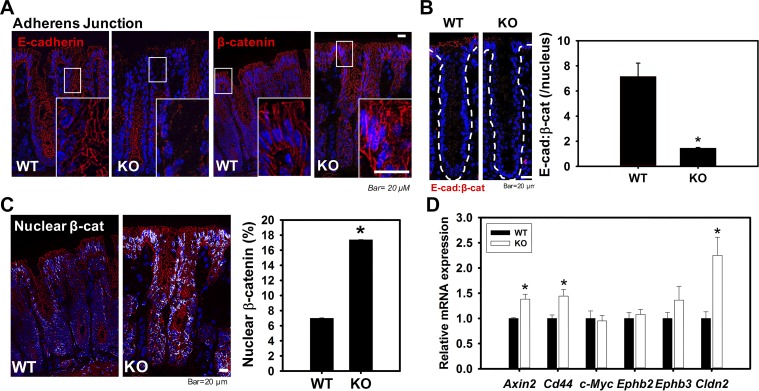

We have previously focused our attention principally on TJs in small intestine from ClC-2 KO mice (28). Therefore, we first evaluated expression and cellular localization of TJ proteins by qPCR and immunolocalization studies. There were no differences in total expression or distribution of TJ proteins (occludin, ZO-1, and claudin-1) in small intestine (data not shown) and colon (Fig. 2) when comparing ClC-2 KO mice with WT mice. Thus, we considered the possibility that AJ proteins may be disrupted, particularly in view of our TEM analyses, so we next evaluated the AJ proteins E-cadherin and β-catenin. qPCR and immunolocalization studies of AJ proteins in small intestine also showed no differences for E-cadherin or β-catenin (data not shown). However, E-cadherin and β-catenin in colon were markedly disrupted and internalized in ClC-2 KO mice compared with well-localized proteins within the membrane in WT mice (Fig. 3A) without alteration of mRNA expression between the two groups (data not shown). In WT colonic crypts, E-cadherin and β-catenin were observed by PLA to be in close association, and PLA dots were mainly observed at cell-to-cell contacts, indicating the presence of well-formed AJs. However, the presence of PLA dots was significantly reduced in colonic crypts from ClC-2 KO mice, showing that the absence of ClC-2 resulted in disorganization of AJs (Fig. 3B). Furthermore, nuclear β-catenin was evaluated using the ImageJ colocalization threshold technique, which revealed that nuclear β-catenin was significantly increased (P = 0.033) in ClC-2 KO colonic crypts compared with WT mice (Fig. 3C). Additionally, real-time PCR showed significant upregulation of TCF/LEF1 target genes, including Axin2 (P = 0.045), Cd44 (P = 0.023), and Cldn2 (P = 0.02) in ClC-2 KO mice compared with WT (Fig. 3D). Taken together, these data indicate that ClC-2 KO mice have disruption of AJ proteins, coupled with evidence of increased β-catenin signaling pathways.

Fig. 2.

Tight junction (TJ) proteins did not show alterations between chloride channel protein-2 (ClC-2) wild-type (WT) and knockout (KO) colon. Sections of colonic tissue of ClC-2 WT and KO mice were immunolabeled for zonula occludens-1 (ZO-1), occludin, and claudin-1 (red), and the nucleus (blue). Images were taken with an Olympus IX83 Inverted Motorized Microscope and were analyzed with cellSens software. Total RNA was extracted from colonic tissues, and real-time PCR was performed with the QuantStudio 6 Flex Real-Time PCR System. ClC-2 KO mice did not show alteration of TJ protein distribution or expression (n = 6).

Fig. 3.

Chloride channel protein-2 (ClC-2) knockout (KO) mice have shown disrupted adherens junctions (AJs) with nuclear localization of β-catenin in colon compared with wild-type (WT) mice. Sections of colonic tissue of ClC-2 WT and KO mice were immunolabeled for E-cadherin and β-catenin (red), and the nucleus (blue). A: ClC-2 KO colonic crypts showed dramatic disruptions of E-cadherin in upper crypts and elevated cytosolic and nuclear distribution of β-catenin. B: proximity ligation assay (PLA) showing the interaction (red dots) between E-cadherin and β-catenin in ClC-2 KO mouse colonic crypts was significantly reduced compared with ClC-2 WT. C: nuclear β-catenin was measured using ImageJ and showed significant elevations in ClC-2 KO colon (n = 6). D: mRNA from the colonic tissues of WT and KO mice were studied for expression of T cell factor-1/lymphoid-enhancing factor-1 (TCF/LEF1) target genes by real-time PCR. The TCF/LEF1 target genes (Axin2, Cd44, and Clcn2) were significantly increased in KO colonic tissues compared with WT. Data are presented as means ± SE (n = 5–6). *P < 0.05 vs. WT, Student’s t-test.

ClC-2 deficiency alters colonic crypt homeostasis.

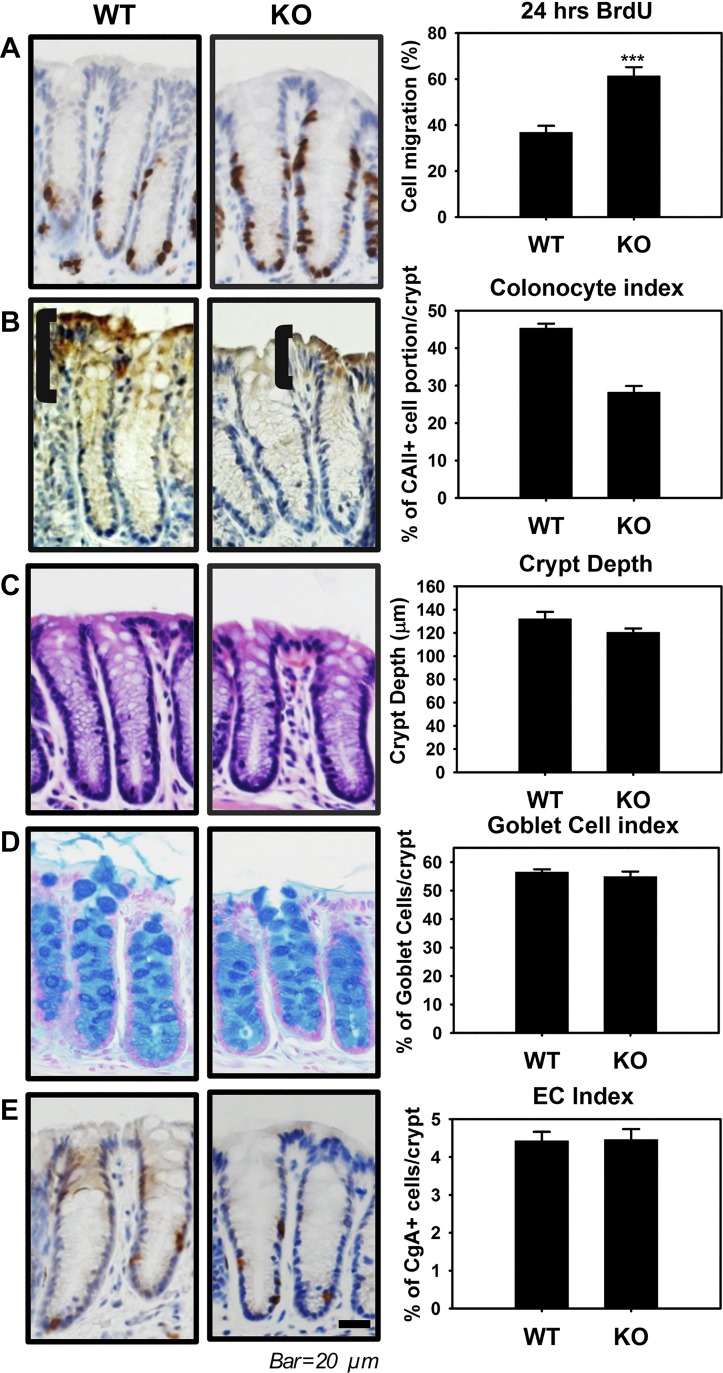

In a study by Hermiston and Gordon (13), chimeric mice that expressed dominant-negative cadherin in some intestinal epithelial cells were used to demonstrate that the disruption of AJs enhanced crypt-villus migration, suggesting that the AJ has a critical function in intestinal homeostasis. Because of dramatic alterations in AJs and nuclear localization of β-catenin in colonic crypts in ClC-2 KO mice, we also questioned whether this affected cellular migration and differentiation within the crypts. Therefore, we performed histological and immunohistochemical analyses using colonic tissues from ClC-2 WT and KO mice. Mice were given BrdU by intraperitoneal injection 24 h before tissue analysis. Immunohistochemical analyses revealed that the proportion of BrdU-positive cells per colonic crypts was significantly increased (P = 0.00040) in ClC-2 KO mice compared with WT mice, indicative of an increased epithelial turnover rate in the colonic crypts of ClC-2 KO mice (Fig. 4A). Additionally, CAII-positive colonocytes were significantly reduced (P = 0.000010) in ClC-2 KO mice compared with WT mice, indicative of reduced differentiation of colonocytes in ClC-2 KO mice (Fig. 4B). However, there were no differences in crypt depth (P = 0.99) and the relative number of enterochromaffin cells (EC, P = 0.93) and goblet cells (P = 0.50) in colonic epithelium when comparing the two genotypes of mice (Fig. 4, C, D, and E). Additionally, there were no differences in the same indexes of turnover rate and differentiation in the small intestine, including BrdU labeling, villus height, crypt depth, and the relative numbers of EC cells and goblet cells in ClC-2 KO mice compared with WT mice (data not shown). Collectively, these results indicate that ClC-2 has a fundamental role in the maintenance of colonic homeostasis, particularly of the mature surface enterocyte compartment, but not small intestinal homeostasis.

Fig. 4.

Chloride channel protein-2 (ClC-2) knockout (KO) mice have altered colonic crypt differentiation. A: ClC-2 wild-type (WT) and KO mice were given bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU, ip) 24 h before being killed and analyzed (n = 6). The ratio of BrdU-positive cells in colonic crypts was significantly increased in ClC-2 KO mice compared with WT mice. B: immunohistochemistry (IHC) for carbonic anhydrase II (CAII) as a maker of mature colonic enterocytes. The brackets indicate the region of most highly expressed CAII in the crypts, with ClC-2 KO mice having less differentiated colonic enterocytes than WT mice. C: crypt depth in hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained colonic cross sections, showing no significant difference between WT and ClC-2 KO mice. D: the no. of goblet cells per crypt was quantified using Alcian blue staining and showed no significant differences between two groups. E: the ratio of enterochromaffin cells per crypt was quantified using chromogranin A (CgA) staining and showed no significant difference between two groups. Data are presented as means ± SE (n = 6). ***P < 0.001 vs. WT, Student’s t-test.

Colonoids from ClC-2 KO mice have disrupted AJs associated with evidence of reduced differentiation.

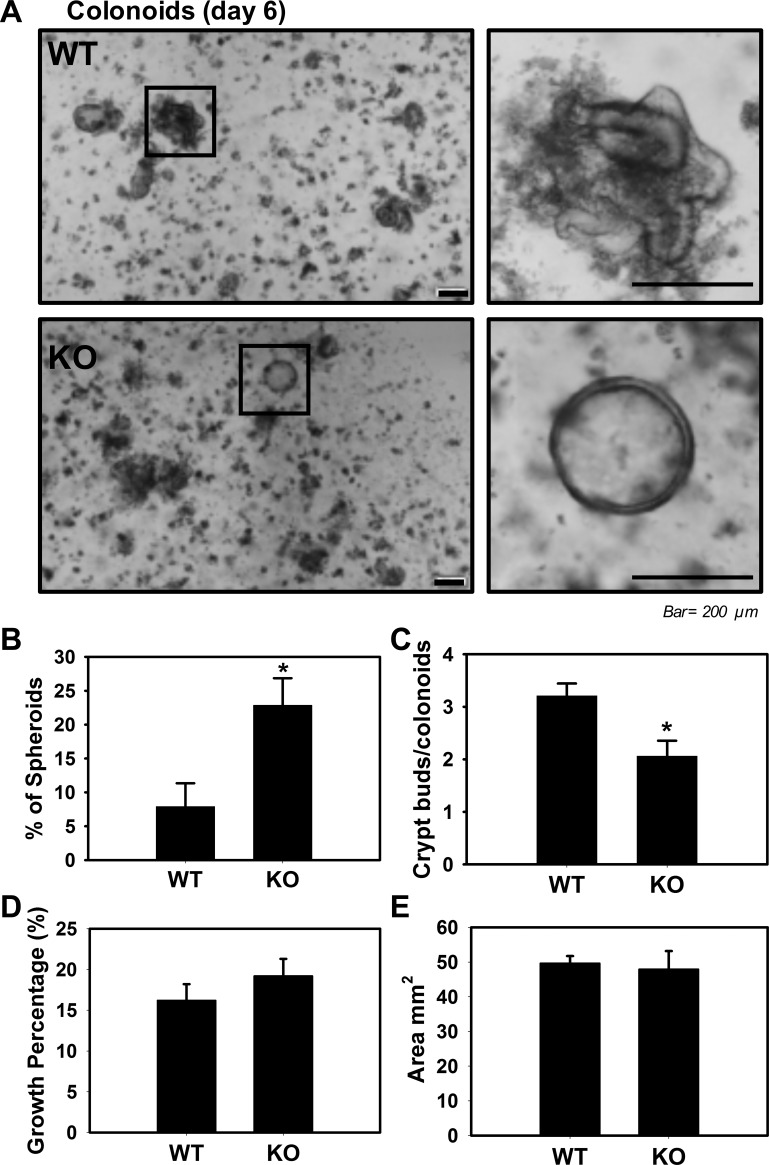

Because our ClC-2 KO murine model is not an intestinal epithelial-specific knockout model, we are unable to separate the role of ClC-2 in epithelial cells as opposed to subepithelial tissues. To overcome this limitation, and further examine crypt development in the absence of ClC-2, we used colonoid crypt culture techniques (31). Colonic crypts from ClC-2 WT mice formed well-differentiated colonoids with a pseudolumen, with relatively few poorly differentiated spheroids. In contrast, ClC-2 KO crypts from the colon formed significantly increased (P = 0.030) numbers of spheroids as opposed to crypt-like colonoids (Fig. 5, A and B). Furthermore, ClC-2 KO crypts from colon had reduced numbers of crypt buds compared with WT crypts (P = 0.022; Fig. 5C). However, the growth percentage and area of colonoids (both of which are surrogate measures of proliferation) from ClC-2 KO crypts were not significantly different compared with WT colonoids (Fig. 5, D and E). These results suggested that ClC-2 has a critical function in colonic crypt differentiation but not proliferation.

Fig. 5.

Chloride channel protein-2 (ClC-2) loss in intestinal crypts altered formation of colonoids. Colonoid cultures from colonic crypts of ClC-2 wild-type (WT) and knockout (KO) mice harvested to form spheroids and colonoids (n = 3). Representative photos were taken (A), and quantification of spheroids (B) and crypts buds (C) was analyzed at day 6 in culture. A and B: at day 6 postculture initiation, we observed a mixed phenotype of more spheroids from ClC-2 KO colonic crypts compared with crypt-like structures in ClC-2 WT. C: the no. of buds from ClC-2 KO colonoids was significantly reduced compared with WT colonoids. D: the efficiency of colonoids from ClC-2 KO crypts (growth percentage) was not different compared with WT. E: the surface area of the colonoids was measured and showed no significant difference between two groups. Data are presented as means ± SE (n = 3). *P < 0.05 vs. WT, Student’s t-test.

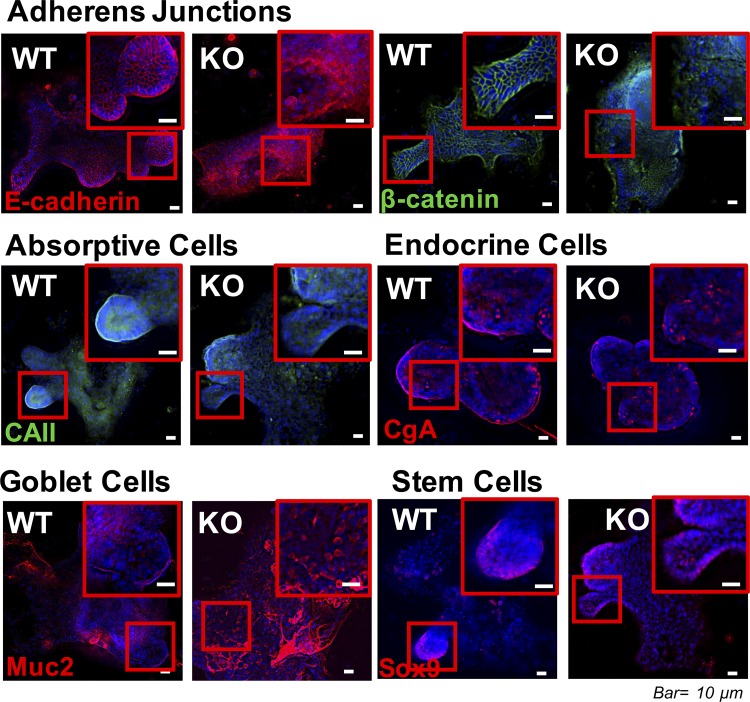

To further examine the role of ClC-2 in crypt differentiation, IF analyses of colonoids were performed. Colonoids from ClC-2 KO mice had marked disruption of E-cadherin and β-catenin compared with WT colonoids (Fig. 6). In addition, ClC-2 KO colonoids showed reduced expression of CAII in differentiated components of the colonoids compared with WT colonoids, as had been the case in native colonic tissues (Fig. 6). Interestingly, there were differences in goblet cell distribution in colonoids that had not been detected in native tissues. In particular, the number of goblet cells, as determined by Muc2 staining, was dramatically increased in ClC-2 KO colonoids (Fig. 6). However, evaluation of expression of the endocrine cell marker CgA and the stem cell marker Sox-9 did not reveal any differences between the two groups. These results indicated that intestinal epithelial ClC-2 has a critical role in colonic differentiation associated with regulation of AJ proteins.

Fig. 6.

Colonoids from chloride channel protein-2 (ClC-2) knockout (KO) mice had altered adherens junctions (AJ) protein distribution. Colonoids from ClC-2 wild-type (WT) and KO mice were immunolabeled for E-cadherin (red), β-catenin (green), carbonic anhydrase II (CAII, green), chromogranin A (CgA, red), Muc2 (red), and the nucleus (blue). ClC-2 KO mice had evidence of disruption of E-cadherin, elevated cytosolic and nuclear distribution of β-catenin, reduced carbonic anhydrase II (CAII), and increased Muc2.

ClC-2 knockdown in HT-29 cells increased proliferation and colony formation associated with disrupted adherens junctional proteins.

To investigate whether downregulation of the ClC-2 gene would increase colon proliferation and colony formation in vitro, we used human colon cells (HT-29) knocked down for ClC-2. We performed CCK-8 assays to determine the role of ClC-2 in proliferation using scrambled shRNA (CT shRNA)- and ClC-2 shRNA-transfected HT-29 cells. In the cell proliferation assay, the absorbance at 450 nm indicated that proliferation was significantly increased (P < 0.001) in the ClC-2 shRNA cells compared with the CT shRNA cells, indicating that cellular proliferation was promoted by the absence of ClC-2 (Fig. 7A). To investigate the ability of ClC-2 knockdown cells to induce colony formation, we studied anchorage-dependent colony formation and anchorage-independent embedded colony growth in soft agar. ClC-2 knockdown caused a marked elevation in the number of colonies of HT-29 cells in an anchorage-dependent (P = 0.000001) and -independent (P = 0.004) (Fig. 7B) manner. In IF studies, the ClC-2 shRNA cells also showed redistribution of the AJ proteins E-cadherin and β-catenin in the cytosol and nucleus (Fig. 7C). The presence of PLA dots, which indicated the presence of E-cadherin/β-catenin complexes, was significantly reduced in ClC-2 shRNA HT-29 cells compared with control cells (Fig. 7D), indicating redistribution of these proteins. These results indicated that the downregulation of ClC-2 increased proliferation and colony formation of human colorectal cells with redistributed AJ proteins.

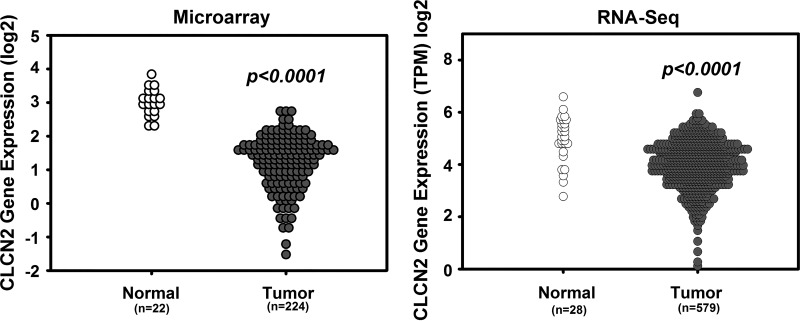

ClC-2 deficiency promotes the development of tumors with activation of TCF/LEF-1 target genes related to disruption of AJ proteins in a model of colitis-associated colorectal tumor formation.

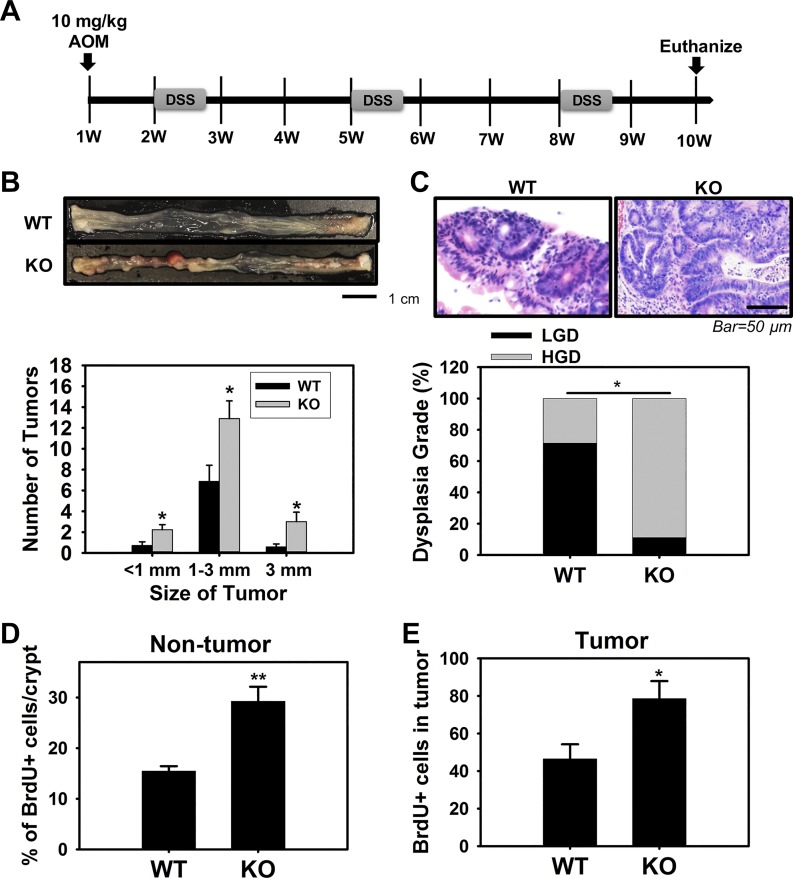

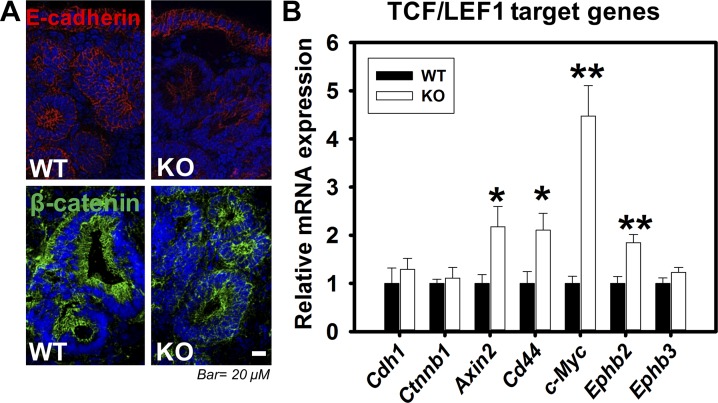

An analysis of ClC-2 (clcn2) expression in a human colorectal cancer cohort available through the National Institutes of Health TCGA using microarray and RNA-Seq data revealed that expression of ClC-2 was significantly reduced in colorectal tumor tissues compared with normal colorectal tissues (Fig. 8). These data indicated that ClC-2 may have critical functions in regulation of colorectal tumorigenicity. Thus, we further examined the role of ClC-2 in tumorigenicity in vivo using an AOM/DSS-induced colitis-associated colorectal tumor model in ClC-2 WT and KO mice (Fig. 9A). ClC-2 KO mice showed a significant elevation in the total number and size of colonic tumors compared with WT mice (Fig. 9B). In addition, ClC-2 KO mice showed significantly increased (P = 0.013) HGD compared with WT mice (Fig. 9C). Proliferation, as measured by immunohistochemical detection of BrdU, was significantly elevated in ClC-2 KO colon tumors (P = 0.026) compared with WT colon tumor (Fig. 9D). In addition, nontumor regions in ClC-2 KO colon showed significant increases (P = 0.0038) in the proliferation rate compared with that of WT mice (Fig. 9E). In further IF studies, ClC-2 KO tumor tissues had reduced E-cadherin expression and internalization of β-catenin compared with well-defined membrane localization in WT tumor tissues (Fig. 10A). Real-time PCR showed significant upregulation of TCF/LEF1 target genes, including Axin2 (P = 0.040), Cd44 (P = 0.026), c-Myc (P = 0.0060), and Ephb2 (P = 0.0080) in ClC-2 KO CAC models compared with WT tumors (Fig. 10B). These results indicate that ClC-2 KO is associated with disruption of AJ proteins and activation of TCF/LEF1 target genes, resulting in increased development of colorectal tumors after AOM/DSS exposure.

Fig. 8.

Gene expression profile of chloride channel protein-2 (ClC-2, clcn2) in colorectal cancer. Gene expression data using microarray and RNA-Seq retrieved from the National Institutes of Health Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) project. The expression of ClC-2 was significantly reduced compared with normal colorectal tissues.

Fig. 9.

Absence of chloride channel protein-2 (ClC-2) promoted the development of colitis-associated tumors. A: protocol used for the development of colitis-associated colorectal cancer (CAC) based on the coadministration of azoxymethane (AOM, 10 mg/kg ip at day 0) and dextran sulfate sodium (DSS, 2% in 3 cycles of 5 days each at weeks 2, 5, and 8). B: absence of ClC-2 significantly elevated tumor growth and size (n = 8–9 for each group). ClC-2 knockout (KO) mice showed a significant elevation in the total number and size of colon tumors compared with wild-type (WT) mice. C: tumors were analyzed for dysplasia grade [low-grade dysplasia (LGD) and high-grade dysplasia (HGD)] and quantified based on percent of tumors demonstrating each grade. ClC-2 KO mice showed significantly increased HGD compared with WT mice, using a Fisher’s exact test. D and E: the proportion of proliferating cells in nontumor and tumor regions, quantified using bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) staining, was significantly increased in the KO CAC mice compared with WT CAC mice. Data are presented as means ± SE. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 vs. WT, Student’s t-test.

Fig. 10.

Absence of chloride channel protein-2 (ClC-2) results in activation of T cell factor-1/lymphoid-enhancing factor-1 (TCF/LEF1) target genes with disrupted adherens junctions (AJs) in colitis-associated tumors. A: sections of colon tumors from wild-type (WT) and knockout (KO) colitis-associated colorectal cancer (CAC) mice were immunolabeled for E-cadherin and β-catenin. Membranous E-cadherin (red) and β-catenin (green) were dramatically reduced in tumor regions. B: mRNA from the tumors of WT and KO mice were studied for expression of AJ proteins and TCF/LEF1 target genes by real-time PCR. mRNA expression levels of E-cadherin (Cdh1) and β-catenin (Ctnnb1) were not altered in KO CAC mice vs. WT CAC mice. However, the TCF/LEF1 target genes (Axin2, Cd44, c-Myc, and Ephb2) were significantly increased in KO CAC tumor tissues. Data are presented as means ± SE. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 vs. WT, Student’s t-test.

DISCUSSION

Previously, we have demonstrated that ClC-2 has a critical role in TJ reassembly during recovery of barrier function in animal models of ischemic injury (23, 24, 29). However, our prior studies had focused on the role of ClC-2 in the TJ barrier of small intestine associated with jejunal and ileal ischemia. More recently, we have demonstrated that ClC-2 also has a critical function during colitis, with a study showing that pre- and posttreatment with the ClC-2 activator lubiprostone ameliorated the severity of colitis by stabilizing TJs (18, 26). In the present study, we were able to provide further evidence for the critical role of ClC-2 in colonic homeostasis, but, somewhat surprisingly, this was more related to regulation of AJs than TJs. This research was initiated by the intriguing finding of markedly tortuous lateral cellular membranes on TEM of the colonic epithelium of ClC-2 KO mice but not the small intestine. Interestingly, the expression of ClC-2 and the AJ proteins E-cadherin and β-catenin was significantly elevated in colonic tissues compared with the small intestine (15). These results led us to speculate that, regardless of effects on TJs, other junctional structures, particularly AJs, may be altered in the absence of ClC-2, particularly in the colon. We further postulated that this, in turn, may affect epithelial differentiation and tumorigenicity, since cells appeared to be loosely connected at the region of the AJC, despite the possible compensatory effect of interdigitation of the lateral cellular membranes. This proved to be the case. In particular, the breakdown of AJ structure in the colon in the absence of ClC-2 disrupted differentiation both in native tissues and colonoids and increased tumorigenicity in a murine model of colitis-associated colorectal cancer.

More specifically, the present study showed that only the AJ proteins E-cadherin and β-catenin were disrupted in ClC-2 KO colonic crypts, based on results from immunofluorescence and in situ PLA, without a concurrent disruption of TJ proteins. These findings strongly suggested that the aforementioned changes in lateral intercellular membrane induced by loss of ClC-2 on TEM are principally related to disruption of AJs. The disruption of AJs was directly related to an increased epithelial turnover rate and reduced colonocyte differentiation, based on the results of the 24-h BrdU assay and immunohistochemistry analyses of the mature epithelial cell marker CAII. However, although BrdU-positive cells were increased in the ClC-2 KO colonic crypt, there was no difference in crypt depth, which is also a surrogate marker for proliferation of crypts. Thus, we postulated that apoptosis would be increased in the ClC-2 KO colonic crypts, but there was no difference in apoptosis between WT and ClC-2 KO mice evaluated by staining for cleaved caspase-3 (data not shown). Therefore, the absence of ClC-2 increased the population of proliferating cells without overly inducing crypt hyperplasia and apoptosis, indicating increased proliferation and delayed differentiation in ClC-2 KO colonic crypts (an increase in the length of the zone of transit-amplifying cells in other words). Further evidence for a critical role of ClC-2 (and by inference AJs) in colonocyte differentiation was developed using colonoid culture, in which ClC-2 KO colonic crypts developed less differentiated spheroids and a reduced number of buds compared with WT colonic crypts. Immunofluorescence analyses of colonoids also showed reduced CAII, which indicated a reduction in differentiation, as was the case in native tissues. However, the reduction in differentiation between native tissues and colonoids had some distinct differences. For instance, the number of goblet cells in colonic tissues from ClC-2 KO mice was not altered compared with WT mice, whereas the goblet cell marker Muc2 was significantly increased in ClC-2 KO colonoids. Secretion of chloride via chloride channels, including ClC-2, is often accompanied by secretion of mucus from goblet cells (11, 19). Thus, the increased number of goblet cells in colonoids but not in native tissues may be a compensatory effect caused by reduced mature colonocytes and therefore reduced chloride secretion, which is somehow not revealed in the normal in vivo environment.

As far as proliferation, there was no difference in SOX9 expression in ClC-2 KO colonoids, as a marker for stem cells, and no difference in crypt depth, as a marker for crypt proliferation, in ClC-2 KO native tissues, suggesting that the effects of ClC-2 on AJs and differentiation were not associated with changes in stem cell proliferation. As additional support for this premise, there were also no differences in the efficiency of colonic crypt development into colonoids and the percentage growth and area of KO and WT colonoids (as surrogate markers of proliferation). Furthermore, the component proteins of AJs, E-cadherin and β-catenin, were significantly more localized to the cytosol and nucleus in ClC-2 KO native tissues, associated with a significantly reduced interaction of E-cadherin and β-catenin based on PLA data. However, these changes were confined principally to the upper differentiated colonocyte compartment of ClC-2 KO crypts, a region where ClC-2 was also most strongly expressed (6, 26). Additional data showed no evidence of similar effects in small intestine. Taken together, the data suggest that ClC-2 regulates crypt differentiation, principally in the colon rather than the small intestine, and this appears to occur through changes in AJ stability that prevents nuclear localization of β-catenin.

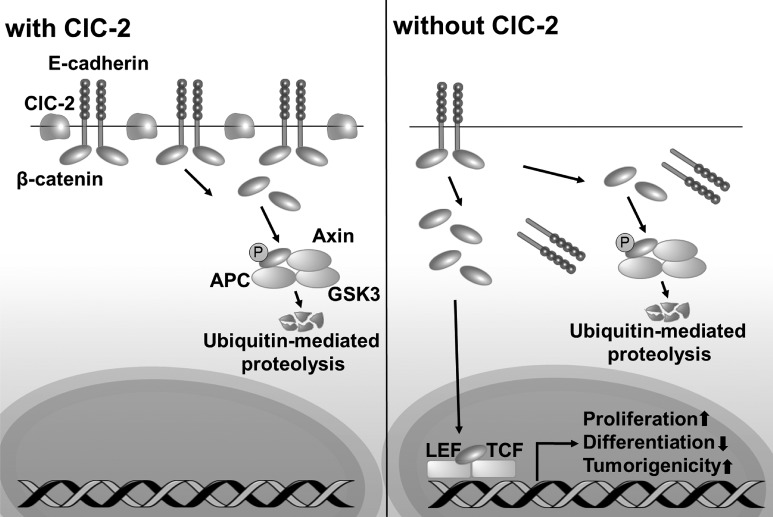

The role of AJ proteins E-cadherin, α-catenin, β-catenin, and p120-catenin in colonic normal development and tumorigenicity has been studied using various model systems (10, 32–34). Most of the previous studies have used genetic deletion (e.g., E-cadherin), which had significant limitations, including lethality. Alternatively, in the present study, ClC-2 KO mouse colon had evidence of disruption of the AJ proteins E-cadherin and β-catenin and associated alterations in colonic homeostasis without evidence of clinical symptoms or changes in gross colonic morphology. We were therefore able to further investigate the role of disrupted AJs in tumorigenicity, and we did this using the AOM/DSS exposure model. This model revealed that ClC-2 KO mice developed a greater tumor burden and more pathological evidence for tumor progression compared with WT mice. We were also able to demonstrate that this increased tumorigenicity in ClC-2 KO mice was primarily caused by disruption of AJ proteins. For example, in studies to localize AJ proteins in colorectal tumors, membrane-bound β-catenin was intensely reduced, although it was difficult to discern whether or not there was an increase in β-catenin in the nucleus because of the different tumor stages that were detected and excessive disruption of tissue architecture throughout these tissues. Nonetheless, several studies have also shown that loss of membrane-bound E-cadherin and β-catenin is closely associated with a poorer prognosis in colorectal cancer patients (1, 5, 37). In addition, we have evidence that the absence of ClC-2 along with disruption of AJs promote colitis-associated tumorigenicity through increased activation of TCF/LEF1 target genes. Although the loss of ClC-2 dramatically increased the tumorigenicity in the AOM/DSS model, the alteration of normal colonic proliferation was limited. In the normal colonic crypts, increased cytosolic β-catenin can be readily degraded by destruction complexes, resulting in relatively little β-catenin translocating in the nucleus to increase activation of TCF/LEF1 target genes (Fig. 11). However, because AOM/DSS treatment induced aberrant protein expression of APC (a key component of the destruction complex) plus mutations of β-catenin (8), we can infer that the loss of ClC-2 promoted elevation of Wnt signaling to further increase tumorigenicity.

Fig. 11.

Chloride channel protein-2 (ClC-2) has a critical function in regulation of colonic homeostasis and tumorigenicity via regulation of the stability of adherens junctions (AJs). In normal colonic mucosa, ClC-2 is associated with stability of AJ proteins to maintain colonic homeostasis. In the absence of ClC-2, colonic epithelial cells have disrupted AJ proteins E-cadherin, with internalization of β-catenin to the cytosol and subsequently the nucleus. Increased nuclear β-catenin results in alteration of colonic homeostasis and increased tumorigenicity associated with increased transcription of T cell factor-1/lymphoid-enhancing factor-1 (TCF/LEF1) target genes.

Although we previously found that deletion or activation of ClC-2 altered the TJ barrier in intestinal injury models, including ischemia/reperfusion and DSS-induced colitis, the TJ proteins were interestingly not altered in normal colonic mucosa. However, the AJs were dramatically disrupted in normal colonic crypts, indicating that the AJs are more closely associated with ClC-2 in regulation of colonic homeostasis. Although it is difficult to clearly identify the mechanisms by which ClC-2 regulates the AJ proteins, we are interested in several mechanisms that we would like to further study. Our previous study showed that ClC-2-mediated intestinal chloride secretion restores TER in ischemia-injured intestine (23) and that secretion via ClC-2 is closely associated Ca2+ homeostasis (9). Because the assembly of E-cadherin is Ca2+ dependent, the regulation of Ca2+ homeostasis by chloride secretion is an interesting possible mechanism. Alternatively, ClC-2 may be directly involved in regulation of AJ stability. In glial cells, the abundance of ClC-2 and its subcellular location are dependent on the cell adhesion molecule GlialCAM, which physically binds ClC-2 (14, 16). Thus, ClC-2 may also physically interact with E-cadherin to regulate the AJs in the intestine.

In conclusion, the present data demonstrate that knockout of ClC-2 resulted in disruption of AJ proteins, with a possible compensatory response of interdigitation of the lateral epithelial membranes, as seen on TEM. These findings enabled us to further explore the role of AJs in colonic crypt differentiation and tumorigenicity (Fig. 11). As far as differentiation, nuclear localization of β-catenin resulted in reduced differentiation of mature colonocytes, but not other cell types. Of further interest, these effects were not seen in the small intestine, indicating an increased importance of ClC-2 AJ regulation in the colon. Our studies also highlighted the potential for progression of colitis-associated cancer in the presence of unstable AJs. Our studies may also point to potential clinical uses of ClC-2 as a prognostic marker or as a target for therapy in patients with inflammatory bowel disease at risk of the associated colorectal cancer.

GRANTS

This research was supported by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Pilot and Feasibility Grant P30-DK-034987 (to Y. Jin).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Y.J. and A.T.B. conceived and designed research; Y.J. and D.R.I. performed experiments; Y.J., D.R.I., and S.T.M. analyzed data; Y.J., D.R.I., S.T.M., and A.T.B. interpreted results of experiments; Y.J. and D.R.I. prepared figures; Y.J. drafted manuscript; Y.J., S.T.M., and A.T.B. edited and revised manuscript; Y.J., D.R.I., S.T.M., and A.T.B. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. John Cullen, North Carolina State University, for advice on evaluation of mucosal pathology. We also thank Laboratory Animal Resources and the Histopathology Laboratory, North Carolina State University, for technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aust DE, Terdiman JP, Willenbucher RF, Chew K, Ferrell L, Florendo C, Molinaro-Clark A, Baretton GB, Lohrs U, Waldman FM. Altered distribution of beta-catenin, and its binding proteins E-cadherin and APC, in ulcerative colitis-related colorectal cancers. Mod Pathol 14: 29–39, 2001. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3880253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barrett CW, Singh K, Motley AK, Lintel MK, Matafonova E, Bradley AM, Ning W, Poindexter SV, Parang B, Reddy VK, Chaturvedi R, Fingleton BM, Washington MK, Wilson KT, Davies SS, Hill KE, Burk RF, Williams CS. Dietary selenium deficiency exacerbates DSS-induced epithelial injury and AOM/DSS-induced tumorigenesis. PLoS One 8: e67845, 2013. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blikslager AT, Moeser AJ, Gookin JL, Jones SL, Odle J. Restoration of barrier function in injured intestinal mucosa. Physiol Rev 87: 545–564, 2007. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00012.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boivin GP, Washington K, Yang K, Ward JM, Pretlow TP, Russell R, Besselsen DG, Godfrey VL, Doetschman T, Dove WF, Pitot HC, Halberg RB, Itzkowitz SH, Groden J, Coffey RJ. Pathology of mouse models of intestinal cancer: consensus report and recommendations. Gastroenterology 124: 762–777, 2003. doi: 10.1053/gast.2003.50094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bruun J, Kolberg M, Nesland JM, Svindland A, Nesbakken A, Lothe RA. Prognostic significance of β-catenin, E-cadherin, and SOX9 in colorectal cancer: results from a large population-representative series. Front Oncol 4: 118, 2014. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2014.00118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Catalán MA, Flores CA, González-Begne M, Zhang Y, Sepúlveda FV, Melvin JE. Severe defects in absorptive ion transport in distal colons of mice that lack ClC-2 channels. Gastroenterology 142: 346–354, 2012. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.10.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clevers H. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in development and disease. Cell 127: 469–480, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Robertis M, Massi E, Poeta ML, Carotti S, Morini S, Cecchetelli L, Signori E, Fazio VM. The AOM/DSS murine model for the study of colon carcinogenesis: From pathways to diagnosis and therapy studies. J Carcinog 10: 9, 2011. doi: 10.4103/1477-3163.78279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fernandes-Rosa FL, Daniil G, Orozco IJ, Göppner C, El Zein R, Jain V, Boulkroun S, Jeunemaitre X, Amar L, Lefebvre H, Schwarzmayr T, Strom TM, Jentsch TJ, Zennaro MC. A gain-of-function mutation in the CLCN2 chloride channel gene causes primary aldosteronism. Nat Genet 50: 355–361, 2018. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0053-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fevr T, Robine S, Louvard D, Huelsken J. Wnt/beta-catenin is essential for intestinal homeostasis and maintenance of intestinal stem cells. Mol Cell Biol 27: 7551–7559, 2007. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01034-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frizzell RA, Hanrahan JW. Physiology of epithelial chloride and fluid secretion. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2: a009563, 2012. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a009563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gehren AS, Rocha MR, de Souza WF, Morgado-Díaz JA. Alterations of the apical junctional complex and actin cytoskeleton and their role in colorectal cancer progression. Tissue Barriers 3: e1017688, 2015. doi: 10.1080/21688370.2015.1017688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hermiston ML, Gordon JI. In vivo analysis of cadherin function in the mouse intestinal epithelium: essential roles in adhesion, maintenance of differentiation, and regulation of programmed cell death. J Cell Biol 129: 489–506, 1995. doi: 10.1083/jcb.129.2.489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoegg-Beiler MB, Sirisi S, Orozco IJ, Ferrer I, Hohensee S, Auberson M, Gödde K, Vilches C, de Heredia ML, Nunes V, Estévez R, Jentsch TJ. Disrupting MLC1 and GlialCAM and ClC-2 interactions in leukodystrophy entails glial chloride channel dysfunction. Nat Commun 5: 3475, 2014. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huels DJ, Ridgway RA, Radulescu S, Leushacke M, Campbell AD, Biswas S, Leedham S, Serra S, Chetty R, Moreaux G, Parry L, Matthews J, Song F, Hedley A, Kalna G, Ceteci F, Reed KR, Meniel VS, Maguire A, Doyle B, Söderberg O, Barker N, Watson A, Larue L, Clarke AR, Sansom OJ. E-cadherin can limit the transforming properties of activating β-catenin mutations. EMBO J 34: 2321–2333, 2015. doi: 10.15252/embj.201591739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jeworutzki E, López-Hernández T, Capdevila-Nortes X, Sirisi S, Bengtsson L, Montolio M, Zifarelli G, Arnedo T, Müller CS, Schulte U, Nunes V, Martínez A, Jentsch TJ, Gasull X, Pusch M, Estévez R. GlialCAM, a protein defective in a leukodystrophy, serves as a ClC-2 Cl(-) channel auxiliary subunit. Neuron 73: 951–961, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.12.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jin Y, Blikslager AT. ClC-2 regulation of intestinal barrier function: Translation of basic science to therapeutic target. Tissue Barriers 3: e1105906, 2015. doi: 10.1080/21688370.2015.1105906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jin Y, Pridgeon T, Blikslager A. Pharmaceutical activation or genetic absence of ClC-2 alters tight junctions during experimental colitis” has been reviewed and accepted for publication in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Inflamm Bowel Dis 21: 2747–2757, 2015. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim YS, Ho SB. Intestinal goblet cells and mucins in health and disease: recent insights and progress. Curr Gastroenterol Rep 12: 319–330, 2010. doi: 10.1007/s11894-010-0131-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. Lessons from hereditary colorectal cancer. Cell 87: 159–170, 1996. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81333-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matheson J, Bühnemann C, Carter EJ, Barnes D, Hoppe HJ, Hughes J, Cobbold S, Harper J, Morreau H, Surakhy M, Hassan AB. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition and nuclear β-catenin induced by conditional intestinal disruption of Cdh1 with Apc is E-cadherin EC1 domain dependent. Oncotarget 7: 69883–69902, 2016. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.11513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matter K, Aijaz S, Tsapara A, Balda MS. Mammalian tight junctions in the regulation of epithelial differentiation and proliferation. Curr Opin Cell Biol 17: 453–458, 2005. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2005.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moeser AJ, Haskell MM, Shifflett DE, Little D, Schultz BD, Blikslager AT. ClC-2 chloride secretion mediates prostaglandin-induced recovery of barrier function in ischemia-injured porcine ileum. Gastroenterology 127: 802–815, 2004. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moeser AJ, Nighot PK, Engelke KJ, Ueno R, Blikslager AT. Recovery of mucosal barrier function in ischemic porcine ileum and colon is stimulated by a novel agonist of the ClC-2 chloride channel, lubiprostone. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 292: G647–G656, 2007. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00183.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nehrke K, Arreola J, Nguyen HV, Pilato J, Richardson L, Okunade G, Baggs R, Shull GE, Melvin JE. Loss of hyperpolarization-activated Cl(-) current in salivary acinar cells from Clcn2 knockout mice. J Biol Chem 277: 23604–23611, 2002. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202900200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nighot P, Young K, Nighot M, Rawat M, Sung EJ, Maharshak N, Plevy SE, Ma T, Blikslager A. Chloride channel ClC-2 is a key factor in the development of DSS-induced murine colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis 19: 2867–2877, 2013. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0b013e3182a82ae9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nighot PK, Blikslager AT. Chloride channel ClC-2 modulates tight junction barrier function via intracellular trafficking of occludin. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 302: C178–C187, 2012. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00072.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nighot PK, Blikslager AT. ClC-2 regulates mucosal barrier function associated with structural changes to the villus and epithelial tight junction. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 299: G449–G456, 2010. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00520.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nighot PK, Moeser AJ, Ryan KA, Ghashghaei T, Blikslager AT. ClC-2 is required for rapid restoration of epithelial tight junctions in ischemic-injured murine jejunum. Exp Cell Res 315: 110–118, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2008.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Orsulic S, Huber O, Aberle H, Arnold S, Kemler R. E-cadherin binding prevents beta-catenin nuclear localization and beta-catenin/LEF-1-mediated transactivation. J Cell Sci 112: 1237–1245, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sato T, Vries RG, Snippert HJ, van de Wetering M, Barker N, Stange DE, van Es JH, Abo A, Kujala P, Peters PJ, Clevers H. Single Lgr5 stem cells build crypt-villus structures in vitro without a mesenchymal niche. Nature 459: 262–265, 2009. doi: 10.1038/nature07935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schneider MR, Dahlhoff M, Horst D, Hirschi B, Trülzsch K, Müller-Höcker J, Vogelmann R, Allgäuer M, Gerhard M, Steininger S, Wolf E, Kolligs FT. A key role for E-cadherin in intestinal homeostasis and Paneth cell maturation. PLoS One 5: e14325, 2010. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shibata H, Takano H, Ito M, Shioya H, Hirota M, Matsumoto H, Kakudo Y, Ishioka C, Akiyama T, Kanegae Y, Saito I, Noda T. Alpha-catenin is essential in intestinal adenoma formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 18199–18204, 2007. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705730104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Smalley-Freed WG, Efimov A, Burnett PE, Short SP, Davis MA, Gumucio DL, Washington MK, Coffey RJ, Reynolds AB. p120-catenin is essential for maintenance of barrier function and intestinal homeostasis in mice. J Clin Invest 120: 1824–1835, 2010. doi: 10.1172/JCI41414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stauber T, Weinert S, Jentsch TJ. Cell biology and physiology of CLC chloride channels and transporters. Compr Physiol 2: 1701–1744, 2012. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c110038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Washington MK, Powell AE, Sullivan R, Sundberg JP, Wright N, Coffey RJ, Dove WF. Pathology of rodent models of intestinal cancer: progress report and recommendations. Gastroenterology 144: 705–717, 2013. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.01.067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang S, Wang Z, Shan J, Yu X, Li L, Lei R, Lin D, Guan S, Wang X. Nuclear expression and/or reduced membranous expression of β-catenin correlate with poor prognosis in colorectal carcinoma: A meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 95: e5546, 2016. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000005546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]