Abstract

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of the most commonly diagnosed cancers, and it is characterized by genetic and epigenetic alterations, as well as by inflammatory cell infiltration among malignant and stromal cells. However, this dynamic infiltration can be influenced by the microenvironment to promote tumor proliferation, survival and metastasis or cancer inhibition. In particular, the cancer microenvironment metabolites can regulate the inflammatory cells to induce a chronic inflammatory response that can be a predisposing condition for CRC retention. In addition, some nutritional components might contribute to a chronic inflammatory condition by regulating various immune and inflammatory pathways. Besides that, diet strongly modulates the gut microbiota composition, which has a key role in maintaining gut homeostasis and is associated with the modulation of host inflammatory and immune responses. Therefore, diet has a fundamental role in CRC initiation, progression and prevention. In particular, functional foods such as probiotics, prebiotics and symbiotics can have a potentially positive effect on health beyond basic nutrition and have anti-inflammatory effects. In this review, we discuss the influence of diet on gut microbiota composition, focusing on its role on gut inflammation and immunity. Finally, we describe the potential benefits of using probiotics and prebiotics to modulate the host inflammatory response, as well as its application in CRC prevention and treatment.

Keywords: Colorectal cancer, Diet, Inflammation, Immune response, Gut microbiota

Core tip: The host immune system plays a central role in colorectal cancer prevention and development. However, the immune response is deeply influenced by gut microbiota composition, which in turn is modulated by host diet. Therefore, diet could be used as a strong ally to prevent colorectal cancer and to support its treatment.

INTRODUCTION

Inflammation consists of an innate system with cellular and humoral responses to an injury induced by foreign organisms, dead cells or physical irritants. The aim is to attempt to inactivate the primary triggers and to regenerate the injured tissues. As a response to those injuries, a multifactorial network of chemical signals initiates and amplifies the recruitment of leukocytes (neutrophils, monocytes, and eosinophils) to the damage sites[1]. Nevertheless, when unregulated, the inflammatory process can become chronic with a persistent production of growth factors, reactive oxygen (RO) and nitrogen species (NS) that interact with DNA. As result, permanent genomic alterations have been identified[2] that can lead to the development of diseases, such as obesity[3], diabetes[4], and different cancers[5,6].

Inflammation has been considered a predisposing condition for tumor development since 1863[7,8], and nowadays at least 20% of all cancers are considered to be a direct consequence of a chronic inflammatory process[9]. Besides that, many aspects of malignancy are affected by cancer-associated inflammation[10-12]. Chronic inflammation persistently promotes a pro-tumorigenic microenvironment, which is rich in cytokines, the primary players regulators of crosstalk between malignant cells and surrounding stromal cells[13].

Chronic inflammatory intestinal disorders, such as inflammatory bowel diseases (commonly known as IBD), including Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, are considered to be risk factors for colorectal cancer (CRC), as their initiation and progression are closely linked to the gene-environment and gene-gene interactions[14-17]. In this scenario, the inflammatory microenvironment is considered a crucial contributing factor to the development of CRC[5,10,18,19]. Even being one of the most studied human malignancies, CRC is still the third most common cancer worldwide with 140,250 new cases estimated in 2018[20]. CRC occurs more frequently in high-income countries[21] mostly in sporadic forms, with only 25% of the cases having a familial feature[22]. Furthermore, the immune system also plays an important role in antitumor resistance[23].

Since some nutritional components, such as saturated fats, refined carbohydrates, and red meat, may have pro-inflammatory properties, the World Cancer Research Foundation and the American Institute for Cancer Research consider diet to be one of the most important exogenous factors in CRC etiology[24-28]. In addition, epidemiological studies have demonstrated that diet-gene interactions can cause diverse somatic alterations known to be involved in gastrointestinal cancer development. These distinct alterations could be associated with the wide variation of CRC risk and progression, among different individuals[29]. Besides that, food and nutritional aspects have a major impact on the modulation of host gut microbiota (GM)[30-32], which in turn have a crucial symbiotic relationship with the host by regulating its physiology and immune system, making them important factors in health and disease.

In this review, we point out the main aspects of the CRC immunological scenario and the dietary impact on CRC-associated inflammation and GM modulation. Finally, we discuss the potential beneficial effects of probiotics and prebiotics to restore intestinal microbiota in CRC prevention and as a support to current anti-CRC treatments.

IMPACT OF DIETARY HABITS AND LIFESTYLE IN CRC

Nowadays, it is estimated that 30%-40% of different cancers are caused by food, nutrition and other lifestyle factors, which make cancer a somewhat preventable disease. Overwhelming epidemiological data suggest that dietary factors, particularly those that result in overweight and obesity, influence risk, morbidity and mortality in multiple cancers[33], especially CRC[29]. Because of this, the Department of Health and Human Services at the National Institutes of Health and The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality have attempted to implement lifestyle interventions among the population, aiming to highlight the importance of diet and healthy lifestyle for disease prevention, including cancer[34,35].

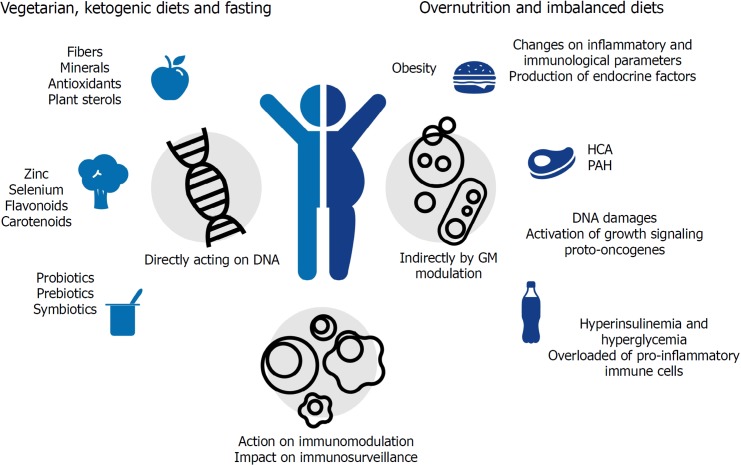

Although diet is considered an important source for mutagenic compounds (that may lead to tumor development)[36], distinct from other environmental factors such as ultraviolet (commonly known as UV) rays in melanoma (of which the role is cancer is well established), the association between diet and cancer might not be linear (Table 1). The link between nutrition and cancer can be muddled by other health-compromising factors such as smoking and alcohol consumption, sedentary lifestyle and exposure to environmental toxicants, all of which are well established risk factors for cancer development[37]. Thus, even if it is hard to ‘isolate’ dietary risk factors in epidemiological studies, animal models have irrefutably demonstrated the nutrition influences on cancer evolution[38]. Besides that, as demonstrated in Figure 1, diet components could act on cancer initiation and progression indirectly by increasing endocrine factor production, changing inflammatory and immunological parameters, or by changing the GM composition[37].

Table 1.

Summary of the main references that suggest that diet is harmful or protective to host health

| Pathways |

Ref. |

|

| Harmful | Protective | |

| High ratio saturated fat | [27,34,39,40] | |

| Obesity and cancer | [3,32,34,40,63] | |

| Meat intake | [29,39,41-44,123,124] | [32,45] |

| Alcohol intake | [41] | |

| Carbohydrate intake | [25,28,58] | [26,73] |

| Host microbiota and cancer | [65,87,100,133] | [70,72,100,105] |

| Probiotic and prebiotic supplementation | [69,93-96,98,99,101,102,104,106,107,110,111,116-119] | |

Figure 1.

Diet components can directly or indirectly act on cancer prevention or initiation/progression. Beneficial direct actions are exemplified by nutrients, which can directly protect cells from DNA damage and decrease oxidative stress. A harmful direct effect is exemplified by DNA damage, activation of growth signaling proto-oncogenes and changes in proinflammatory cytokines. Indirect beneficial and harmful effects are represented by the modulation of gut microbiota and obesity induction, respectively. HCA: Heterocyclic amines; PAH: Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon.

Direct effects of dietary components on cancer development could be represented by the strong correlation between CRC incidence and excessive consumption of fats and proteins (mainly of animal sources), processed meat, and substantial alcohol consumption (more than 30 g/d)[39-41]. People are more susceptible to develop CRC when they have an increased intake of heterocyclic amines. The main heterocyclic amines generated are 2-amino-1-methyl-6- phenyl-imidazo[4,5-b]pyridine (PhIP), 2-amino-3,8-dimethylimidazo[4,5-f]quinoxaline (MeIQx), and benzo[a]pyrene (Bap) a polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon, the first reported group of chemical carcinogens for human cells[42]. In contrast, a vegetarian diet seems to prevent cardiovascular diseases, type 2 diabetes and cancer[43], since fruits and vegetables contain antioxidants, which scavenge free radicals and prevent DNA damage[44]. Vegetarian diet also includes a variety of nutrients associated with reduced cancer risk[45]. These compounds can protect cells by affecting the bio-transformation/detoxification pathways (phases I and II), the cell signaling and endogenous antioxidant system[46]. Some micronutrients, such as zinc[47] and selenium[48], have been extensively studied and seem to have important roles in cancer prevention, whereas complex compounds such as carotenoids[49], flavonoids[50], curcumin and silymarin[51], resveratrol[52], folate[53] and total oligomeric flavonoids[54] show both direct activity against tumor cells and in vitro immunomodulatory effects.

In addition, nutrients such as glucose and amino acids increase tumor cell proliferation by activating growth signaling proto-oncogenes such as IGF1R, PI3K, and AKT. In this way, deprivation of nutrients and nutrient-responsive growth factors selectively kill high proliferative/resilient cancer cells by forcing their glycolytic asset toward an oxidative one. In fact, calorie restriction, defined as 30%-60% less of daily calorie requirement without malnutrition, is known to extend a healthy life span with anticancer effects, being particularly effective in reducing the incidence, mass, and metastasis of breast cancer (due to the profound metabolic reprogramming that builds up adaptive stress responses)[55]. Controlled fasting has also been demonstrated to be a promising adjuvant treatment in cancer therapy, mainly when associated with ketogenic diets that are low in carbohydrates and high in fats[56]. Moreover, short-term fasting exerts a beneficial impact on cancer immunosurveillance, as it induces regulatory T cell depletion, while an isocaloric diet with protein restriction has been demonstrated to induce an IRE1α-dependent unfolded protein response in cancer cells, increasing the number of cytotoxic CD8+ T cells (CTLs). The presence of CTLs in the tumor environment (tumor infiltrating lymphocytes) is considered a positive outcome of cancer treatment[55,57].

Diet can also indirectly contribute to cancer initiation and progression by favoring obesity through over-nutrition and imbalanced diets. Obesity is closely linked to chronic inflammation, a significant cancer risk factor. When in a hyperplastic and hypertrophic state, adipose tissue is overloaded with a variety of pro-inflammatory immune cells, including classically activated macrophages, natural killer (commonly known as NK) cells, mast cells, neutrophils, dendritic cells (commonly known as DCs), B cells, CTL and T helpers 1 (Th1) cells[58]. These cells release pro-inflammatory factors such as interferon-γ (IFN-γ), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin 1β (IL-1β), and interleukin 6 (IL-6), which lead to increased local and systemic inflammation and insulin resistance[33], becoming a strong promoter of tumor progression[59].

The presence of insulin-resistant cells results in hyperinsulinemia and hyperglycemia, two important tumor-promoting effects; in fact, high concentrations of insulin, glucose, and non-esterified fatty acid (NEFA) are strong promoters of cell survival, growth, and proliferation and exert similar effects on tumor progenitors. In addition, high glucose concentrations favor glycolytic cancer cell metabolism characterized by enhanced glucose consumption[33]. Moreover, during obesity, adipose tissue macrophages, which in healthy conditions are skewed towards the M2 anti-inflammatory phenotype, are directed to pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages[60]. The M1 macrophages produce tumor-promoting cytokines (e.g., TNF, IL-6, and IL-1b) and chemokines, such as Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) and Macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF)[61].

These data suggest that diet modulation could be used as a form of cancer chemoprevention in healthy individuals. In pharmacology, chemoprevention is used to describe the “use of pharmacological or natural agents that inhibits the development of invasive cancer either by blocking the DNA damage that initiates carcinogenesis or by arresting or reversing the progression of pre-malignant cells in which such damage has already occurred”[62].

Diet is also associated with the modulation of the gut microbiome that has a significant role in host metabolism, nutrition and physiological features (intestinal epithelial cell proliferation and differentiation, pH, function) as well as with the development of the immune system and protection against pathogens[63-65]. However, in addition to diet, the GM is influenced by numerous and incompletely elucidated factors, such as host genetics, gender, age, anthropometric parameters, health/disease condition, geographic and socio-economic factors, exhibiting a huge diversity among individuals[66]. In healthy conditions, the GM plays a key role in the maintenance of the host physiological condition by modulating the host’s immunity. The GM can influence neutrophil migration and function[67], as well as the differentiation of T cell subsets into Th1, Th2, and Th17 or regulatory T cells (Tregs)[68-70]. By fermenting non-digestible complex carbohydrates such as dietary fiber, these commensal bacteria can produce short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), which can cross the intestinal epithelium and reach the lamina propria, directly shaping mucosal immune responses[71].

SCFAs modulate the phenotype and function of numerous immunologically relevant cells, such as colonic epithelial cells, macrophages, neutrophils and DCs[72]. Moreover, upon butyrate (one of the most produced SCFAs) stimulation, the CD4+ effector T cells increase T-bet and IFN-γ expression, being able to exert either beneficial or detrimental effects on the mucosal immune system depending on its concentration and immunological milieu[73]. The presence of CTLs and IFN-γ-producing Th1 cells has been associated with prolonged survival[74,75], making some SCFAs, including butyrate, propionate, and acetate, potential therapeutic tools to modulate inflammatory responses[76,77], including for CRC treatment[78]. Nevertheless, it is important to consider that SCFAs interact with the receptor GPR43 of colonic Tregs, as well as act as histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors in mucosal peripheral Tregs, which under healthy conditions, helps to maintain intestinal immune homeostasis[79-81]. However, in the tumoral scenario (e.g., CRC), GPR43 can impair anti-tumor immunity, decreasing effector T cell proliferation[82].

The role of the GM in CRC progression deserves special attention because there is a strong interaction between GM, the intestinal barrier and immune cells[83-85]. For example, increased epithelial permeability allows the translocation of bacteria, antigens and toxins from the lumen to the lamina propria into the blood stream, which may initiate both local and systemic immune responses[86]. These changes can modify inflammatory cell responses, requiring them to integrate signals (e.g., cytokines) with cues such as local oxygen concentrations and other metabolites, promoting epithelial cell damage that can lead to tumor development[6].

Clinical, epidemiological and experimental data have demonstrated that nutrition and foods have a central role in cancer onset because they can change the tumor risk, the diagnosis after the onset and the life quality after treatment, in addition to their ability to ameliorate the adverse effects of chemotherapy and radiotherapy[87,88]. “Functional foods” and “nutraceuticals” are foods or food components that supply health benefits beyond basic nutrition, like peptides and proteins, amino acids, polyunsaturated fatty acids, dietary fibers, oligosaccharides, vitamins, minerals, antioxidants, probiotics and prebiotics, oils and fatty acids, carbohydrates and fibers[89]. In particular, we have focused on the immune-modulating ability of probiotics and prebiotics, which make them a potential adjuvant therapy for anti-CRC treatments.

ADJUVANT ROLE OF PROBIOTICS AND PREBIOTICS IN CRC TREATMENTS

Probiotics are defined by the International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics (commonly known as ISAPP) as “live microorganisms that, when administered in adequate amounts, confer a health benefit on the host”[90]. They can have health-promoting effects, such as antimicrobial activities against gut pathogens, the ability to decrease blood cholesterol levels, reduce colitis and inflammation, regulate the host energy metabolism and modulate the immune system[91,92]. In the last years, the use of probiotics and prebiotics to control the onset/progression, or their application as adjuvant therapies in different diseases such as influenza[93], nonalcoholic fatty liver disease[94], pancreatitis[95], and Parkinson’s disease[96] has been deeply investigated. In addition, their use is also being considered as a potential anti-cancer alternative or adjuvant therapy[97], since pro/prebiotics can improve the safety of and decrease the side effects of cancer treatment (as demonstrated in several significant clinical trials)[98-100].

In addition to the direct role on GM modulation, probiotics present direct anti-cancer effects by inactivating carcinogens or mutagens, altering cell differentiation and by inducing immunomodulatory effects[101-103]. They increase immunostimulatory activities, improving gut barrier activity by secreting anti-carcinogenic and anti-oxidative molecules[104,105], and finally by activating mononuclear cells, lymphocytes and increasing immunoglobulin A production[106,107]. Probiotic administration also reduces the expression of certain Toll like receptors (TLRs), which increases epithelial barrier resistance[102], and activates phagocytes, which contribute to the maintenance of a vigilance state against tumor cells, especially in the early stages of progression[108].

The use of the Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG (LGG) strain decreased cellular proliferation and carcinogenesis, due to decreased β-catenin and Bcl-2 concentrations and increased p53 and Bax expression in rats. Moreover, this strain can reduce the levels of pro-inflammatory molecules such as COX-2 and NF-κB-p65[103]. However, the recent administration of a mix of Bifidobacterium spp and Lactobacillus spp (the two main strains studied as probiotics in CRC therapies)[109] induced the secretion of anti-inflammatory cytokines and up-regulation of Treg and Th2 response-related gene expression[110]. However, we, in agreement and supported by another study, hypothesize that Tregs can play protective roles prior to cancer initiation in “inflammation-prone” cancers, but after tumor establishment, the Tregs can be co-opted by tumors, assuming a pro-tumorigenic role. In this way, we think that the use of specific probiotics should be applied to prevent the early phases of CRC[111].

In CRC, probiotic administration (aiming to modulate the GM and immune response) has been proven to be a promising innovative approach to counteract CRC progression and increase chemotherapy effectiveness[112]. In an animal model, the administration of combined Bifidobacterium longum and Bifidobacterium breve improved cancer control, strongly reduced tumor development and increased the efficacy of a PD-L1 blocking antibody against cancers[113]. The administration of Lactobacillus lactis can reduce the concentration of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and catalase activity, decreasing tissue inflammation and colonic damage in a BALB/c mouse model. These data suggest that bacteria are capable of affecting inflammatory mediators such as cytokines[114]. However, the use of some bacterial strains as probiotics could have side effects. Lactobacillus acidophilus induces CXCR4 (stromal-derived factor-1 receptor) mRNA expression and reduces tumor growth by 50% in treated mice and induces CT-26 cancer cell apoptosis, showing a role in metastasis prevention; however, its administration also suppressed MHC-class I expression, which is crucial in cancer surveillance[115]. Due to the heterogeneous immunomodulatory roles of probiotics, we believe that a specific selection of bacterial strain is fundamental for probiotic effectiveness. For example, disease stage progression could be an important determining factor in the probiotic strain choice. Moreover, probiotic use in cancer patients generates concern due to the risk of infection and the transfer of antibiotic resistance. Nevertheless, randomized clinical trials have not reported a significant increase in the risk of adverse effects following probiotic supplementation compared to patients who received a placebo. Furthermore, probiotic supplementation has even been proven to be safe and beneficial in these patients[116].

As an adjuvant therapy to chemo/radiotherapy in CRC patients, some clinical assays have demonstrated that probiotics can be an efficacious treatment[117], as supplementation with Lactobacillus rhamnosus decreased the frequency of diarrhea, abdominal distress and dose reduction due to intestinal toxicity compared to patients who received a placebo[118]. A randomized clinical trial about the efficacy and tolerability of Lactobacillus rhamnosus in patients with radiation-induced diarrhea showed that patients who received probiotics had better fecal consistency and decreased bowel movements[119].

Furthermore, since diet is a crucial risk factor in CRC susceptibility[120-122], the administration of prebiotics (that favor specific changes in the composition and/or GM activity) could confer benefits upon host well-being and health[123]. Prebiotics are carbohydrates, principally oligosaccharides, including fructooligossacharides (FOS) xyloogliosaccharides (XOS), inulin, fructans, and galactogliosaccharides (GOS)[124,125]. They resist digestion in the human small intestine and reach the colon, where they become substrates to fermentation by the GM. Prebiotic administration inhibits aberrant crypt formation and SCFA production[126], reduces cecal pH[127] and has anti-carcinogenic effects on the presence of resistant starch, inulin and other oligo-fructans[128,129]. In addition, prebiotics have demonstrated anti-cancer properties by downregulating the expression levels of COX-2, iNOS, NF-kB, and gastrointestinal glutathione peroxidase by their bifidogenic effects and immunomodulatory roles. Finally, prebiotics are also able to modulate the GM by inhibiting pathogen multiplication and enhancing cell apoptosis[130-134].

Probiotics work synergistically with prebiotics (symbiotic) to exert a beneficial impact on GM and on general intestinal health, which make them a potential therapeutic strategy in CRC. Lactobacillus and Bifidobacteria combined with prebiotics, such as oligofructose and inulin, have been shown to counteract tumor progression. A pro/prebiotic cocktail of Bifidobacterium infantum, Lactobacillus acidophilus, Bifidobacterium bifidum, maltodextrin (LBB) and oligofructose increased intestinal ZO-1, MUC2, TLR2 and occludin expression and reduced COX-2 and TLR4 expression in rats[102].

CONCLUSION

The manipulation of nutrients could have potential implications for both the prevention and the treatment of CRC, since it can affect a diverse range of mechanisms, such as cell signaling, apoptosis, and immune system regulation, other than the overlying influence on the gut microbiome.

Diet has a great ability to modulate the cellular responses to environmental stimuli, and a balanced nutritional regime can improve immune metabolism by enhancing the cytotoxic efficiency of CD8+ tumor infiltrating lymphocytes within the tumor mass, showing a potential role in improving cancer prognosis. Furthermore, diet can modulate the GM, and since the intestinal immune system is constantly exposed to numerous xenobiotic and endobiotic metabolites (which shape mucosal immune function and inflammation), the intestinal microbiome and the local immune system maintain the balance between mucosal tolerance and inflammation. In other words, GM manipulation should be a promising treatment to improve the outcomes of CRC.

The fine mechanisms by which dietary nutrients enhance anti-cancer effects of standard anticancer therapies have not been fully elucidated yet.

However, the actual scenario of poor prognosis for many cancer patients, in addition to the severe documented adverse events of current anti-cancer therapies suggest the crucial need to find complementary treatments that have limited patient toxicity and simultaneously enhance therapy responses in cancer versus normal cells. The data discussed in this review suggest that the investigation of probiotic/prebiotic application as coadjuvant anti-cancer treatments will yield interesting results; however, it is still necessary to plan different clinical trials to confirm these very promising results in humans.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Dr. Savannah Rowane Devente and Dr. Federico Boem for their corrections of English grammar and Dr. Cesare Manni who kindly drew the figure in the paper.

Footnotes

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Italy

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Peer-review started: November 5, 2018

First decision: December 12, 2018

Article in press: December 28, 2018

P- Reviewer: Li LJ, Tarantino G, Yu JS S- Editor: Ma RY L- Editor: Filipodia E- Editor: Yin SY

Contributor Information

Carolina Vieira De Almeida, Department of Surgery and Translational Medicine, University of Florence, Florence 50134, Italy.

Marcela Rodrigues de Camargo, Department of Surgery, Stomatology, Pathology and Radiology, Bauru School of Dentistry, São Paulo University, Bauru-Sao Paulo 17012901, Brazil.

Edda Russo, Department of Experimental and Clinical Medicine, University of Florence, Florence 50139, Italy.

Amedeo Amedei, Department of Experimental and Clinical Medicine, University of Florence and Department of Biomedicine, Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria Careggi (AOUC), Florence 50139, Italy. amedeo.amedei@unifi.it.

References

- 1.Karin M, Clevers H. Reparative inflammation takes charge of tissue regeneration. Nature. 2016;529:307–315. doi: 10.1038/nature17039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maeda H, Akaike T. Nitric oxide and oxygen radicals in infection, inflammation, and cancer. Biochemistry (Mosc) 1998;63:854–865. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ellulu MS, Patimah I, Khaza’ai H, Rahmat A, Abed Y. Obesity and inflammation: the linking mechanism and the complications. Arch Med Sci. 2017;13:851–863. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2016.58928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wellen KE, Hotamisligil GS. Inflammation, stress, and diabetes. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:1111–1119. doi: 10.1172/JCI25102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grivennikov SI, Greten FR, Karin M. Immunity, inflammation, and cancer. Cell. 2010;140:883–899. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hobson-Gutierrez SA, Carmona-Fontaine C. The metabolic axis of macrophage and immune cell polarization. Dis Model Mech. 2018:11. doi: 10.1242/dmm.034462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Balkwill F, Mantovani A. Inflammation and cancer: back to Virchow? Lancet. 2001;357:539–545. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04046-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schmidt A, Weber OF. In memoriam of Rudolf virchow: a historical retrospective including aspects of inflammation, infection and neoplasia. Contrib Microbiol. 2006;13:1–15. doi: 10.1159/000092961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mantovani A, Allavena P, Sica A, Balkwill F. Cancer-related inflammation. Nature. 2008;454:436–444. doi: 10.1038/nature07205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Balkwill F, Charles KA, Mantovani A. Smoldering and polarized inflammation in the initiation and promotion of malignant disease. Cancer Cell. 2005;7:211–217. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DeNardo DG, Johansson M, Coussens LM. Immune cells as mediators of solid tumor metastasis. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2008;27:11–18. doi: 10.1007/s10555-007-9100-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Landskron G, De la Fuente M, Thuwajit P, Thuwajit C, Hermoso MA. Chronic inflammation and cytokines in the tumor microenvironment. J Immunol Res. 2014;2014:149185. doi: 10.1155/2014/149185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yi M, Xu J, Liu P, Chang GJ, Du XL, Hu CY, Song Y, He J, Ren Y, Wei Y, Yang J, Hunt KK, Li X. Comparative analysis of lifestyle factors, screening test use, and clinicopathologic features in association with survival among Asian Americans with colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer. 2013;108:1508–1514. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tung J, Politis CE, Chadder J, Han J, Niu J, Fung S, Rahal R, Earle CC. The north-south and east-west gradient in colorectal cancer risk: a look at the distribution of modifiable risk factors and incidence across Canada. Curr Oncol. 2018;25:231–235. doi: 10.3747/co.25.4071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Patel P, De P. Trends in colorectal cancer incidence and related lifestyle risk factors in 15-49-year-olds in Canada, 1969-2010. Cancer Epidemiol. 2016;42:90–100. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2016.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang X, Chan AT, Slattery ML, Chang-Claude J, Potter JD, Gallinger S, Caan B, Lampe JW, Newcomb PA, Zubair N, Hsu L, Schoen RE, Hoffmeister M, Brenner H, Le Marchand L, Peters U, White E. Influence of Smoking, Body Mass Index, and Other Factors on the Preventive Effect of Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs on Colorectal Cancer Risk. Cancer Res. 2018;78:4790–4799. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-18-0326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Feagins LA, Souza RF, Spechler SJ. Carcinogenesis in IBD: potential targets for the prevention of colorectal cancer. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;6:297–305. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2009.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lakatos PL, Lakatos L. Risk for colorectal cancer in ulcerative colitis: changes, causes and management strategies. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:3937–3947. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.3937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.American Cancer Society, Cancer Facts and Figures 2018. Atlanta: American Cancer Society, 2018 Accessed July 11, 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goldstein NS. Serrated pathway and APC (conventional)-type colorectal polyps: molecular-morphologic correlations, genetic pathways, and implications for classification. Am J Clin Pathol. 2006;125:146–153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carethers JM, Jung BH. Genetics and Genetic Biomarkers in Sporadic Colorectal Cancer. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:1177–1190.e3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.06.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grizzi F, Di Ieva A, Russo C, Frezza EE, Cobos E, Muzzio PC, Chiriva-Internati M. Cancer initiation and progression: an unsimplifiable complexity. Theor Biol Med Model. 2006;3:37. doi: 10.1186/1742-4682-3-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.World Cancer Research Fund, American Institute for Cancer Research. In: Food, Nutrition, Physical Activity, and the Prevention of Cancer: a Global Perspective. Washington DC: AICR, 2007; p1-537 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hardman WE. Diet components can suppress inflammation and reduce cancer risk. Nutr Res Pract. 2014;8:233–240. doi: 10.4162/nrp.2014.8.3.233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dumas JA, Bunn JY, Nickerson J, Crain KI, Ebenstein DB, Tarleton EK, Makarewicz J, Poynter ME, Kien CL. Dietary saturated fat and monounsaturated fat have reversible effects on brain function and the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines in young women. Metabolism. 2016;65:1582–1588. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2016.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.López-Alarcón M, Perichart-Perera O, Flores-Huerta S, Inda-Icaza P, Rodríguez-Cruz M, Armenta-Álvarez A, Bram-Falcón MT, Mayorga-Ochoa M. Excessive refined carbohydrates and scarce micronutrients intakes increase inflammatory mediators and insulin resistance in prepubertal and pubertal obese children independently of obesity. Mediators Inflamm. 2014;2014:849031. doi: 10.1155/2014/849031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Samraj AN, Pearce OM, Läubli H, Crittenden AN, Bergfeld AK, Banda K, Gregg CJ, Bingman AE, Secrest P, Diaz SL, Varki NM, Varki A. A red meat-derived glycan promotes inflammation and cancer progression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:542–547. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1417508112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bingham SA. Diet and colorectal cancer prevention. Biochem Soc Trans. 2000;28:12–16. doi: 10.1042/bst0280012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.De Filippo C, Cavalieri D, Di Paola M, Ramazzotti M, Poullet JB, Massart S, Collini S, Pieraccini G, Lionetti P. Impact of diet in shaping gut microbiota revealed by a comparative study in children from Europe and rural Africa. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:14691–14696. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005963107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kałużna-Czaplińska J, Gątarek P, Chartrand MS, Dadar M, Bjørklund G. Is there a relationship between intestinal microbiota, dietary compounds, and obesity? Trends Food Sci Technol. 2017;70:105–113. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li W, Dowd SE, Scurlock B, Acosta-Martinez V, Lyte M. Memory and learning behavior in mice is temporally associated with diet-induced alterations in gut bacteria. Physiol Behav. 2009;96:557–567. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2008.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Font-Burgada J, Sun B, Karin M. Obesity and Cancer: The Oil that Feeds the Flame. Cell Metab. 2016;23:48–62. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ammerman A, Lindquist C, Hersey J, Jackman AM, Gavin NI, Garces C, Lohr KN, Cary TS, Whitener BL. Efficacy of interventions to modify dietary behavior related to cancer risk. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Summ) 2000:1–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Theory at a glance: a guide for health promotion practice. 2nd ed. U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute, 2005; p1-64 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Branca F, Hanley AB, Pool-Zobel B, Verhagen H. Biomarkers in disease and health. Br J Nutr. 2001;86 Suppl 1:S55–S92. doi: 10.1079/bjn2001339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zitvogel L, Pietrocola F, Kroemer G. Nutrition, inflammation and cancer. Nat Immunol. 2017;18:843–850. doi: 10.1038/ni.3754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Deng T, Lyon CJ, Bergin S, Caligiuri MA, Hsueh WA. Obesity, Inflammation, and Cancer. Annu Rev Pathol. 2016;11:421–449. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-012615-044359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.American Cancer Society, Cancer Facts and Figures 2008. Atlanta: American Cancer Society, 2008 Accessed September 29, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Norat T, Lukanova A, Ferrari P, Riboli E. Meat consumption and colorectal cancer risk: dose-response meta-analysis of epidemiological studies. Int J Cancer. 2002;98:241–256. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ognjanovic S, Yamamoto J, Maskarinec G, Le Marchand L. NAT2, meat consumption and colorectal cancer incidence: an ecological study among 27 countries. Cancer Causes Control. 2006;17:1175–1182. doi: 10.1007/s10552-006-0061-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Butler LM, Sinha R, Millikan RC, Martin CF, Newman B, Gammon MD, Ammerman AS, Sandler RS. Heterocyclic amines, meat intake, and association with colon cancer in a population-based study. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157:434–445. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McEvoy CT, Temple N, Woodside JV. Vegetarian diets, low-meat diets and health: a review. Public Health Nutr. 2012;15:2287–2294. doi: 10.1017/S1368980012000936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Møller P, Loft S. Dietary antioxidants and beneficial effect on oxidatively damaged DNA. Free Radic Biol Med. 2006;41:388–415. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kelly JH Jr, Sabaté J. Nuts and coronary heart disease: an epidemiological perspective. Br J Nutr. 2006;96 Suppl 2:S61–S67. doi: 10.1017/bjn20061865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Collins AR, Azqueta A, Langie SA. Effects of micronutrients on DNA repair. Eur J Nutr. 2012;51:261–279. doi: 10.1007/s00394-012-0318-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ho E. Zinc deficiency, DNA damage and cancer risk. J Nutr Biochem. 2004;15:572–578. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2004.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jayaprakash V, Marshall JR. Selenium and other antioxidants for chemoprevention of gastrointestinal cancers. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2011;25:507–518. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2011.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Astley SB, Elliott RM, Archer DB, Southon S. Increased cellular carotenoid levels reduce the persistence of DNA single-strand breaks after oxidative challenge. Nutr Cancer. 2002;43:202–213. doi: 10.1207/S15327914NC432_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Aherne SA, O’Brien NM. Lack of effect of the flavonoids, myricetin, quercetin, and rutin, on repair of H2O2-induced DNA single-strand breaks in Caco-2, Hep G2, and V79 cells. Nutr Cancer. 2000;38:106–115. doi: 10.1207/S15327914NC381_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Niture SK, Velu CS, Smith QR, Bhat GJ, Srivenugopal KS. Increased expression of the MGMT repair protein mediated by cysteine prodrugs and chemopreventative natural products in human lymphocytes and tumor cell lines. Carcinogenesis. 2007;28:378–389. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgl155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gatz SA, Keimling M, Baumann C, Dörk T, Debatin KM, Fulda S, Wiesmüller L. Resveratrol modulates DNA double-strand break repair pathways in an ATM/ATR-p53- and -Nbs1-dependent manner. Carcinogenesis. 2008;29:519–527. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgm283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Williams JD, Jacobson MK. Photobiological implications of folate depletion and repletion in cultured human keratinocytes. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2010;99:49–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2010.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bouhlel I, Valenti K, Kilani S, Skandrani I, Ben Sghaier M, Mariotte AM, Dijoux-Franca MG, Ghedira K, Hininger-Favier I, Laporte F, Chekir-Ghedira L. Antimutagenic, antigenotoxic and antioxidant activities of Acacia salicina extracts (ASE) and modulation of cell gene expression by H2O2 and ASE treatment. Toxicol In Vitro. 2008;22:1264–1272. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2008.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lettieri-Barbato D, Aquilano K. Pushing the Limits of Cancer Therapy: The Nutrient Game. Front Oncol. 2018;8:148. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2018.00148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Allen BG, Bhatia SK, Anderson CM, Eichenberger-Gilmore JM, Sibenaller ZA, Mapuskar KA, Schoenfeld JD, Buatti JM, Spitz DR, Fath MA. Ketogenic diets as an adjuvant cancer therapy: History and potential mechanism. Redox Biol. 2014;2:963–970. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2014.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.De Almeida CV, Kaneno R and Amedei A. T Cells in Gastrointestinal Cancers: Role and Therapeutic Strategies. In: Frontiers in Anti-Cancer Drug Discovery, 8th ed [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ferrante AW Jr. The immune cells in adipose tissue. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2013;15 Suppl 3:34–38. doi: 10.1111/dom.12154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Grivennikov SI, Karin M. Inflammatory cytokines in cancer: tumour necrosis factor and interleukin 6 take the stage. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70 Suppl 1:i104–i108. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.140145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.McNelis JC, Olefsky JM. Macrophages, immunity, and metabolic disease. Immunity. 2014;41:36–48. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Weisberg SP, McCann D, Desai M, Rosenbaum M, Leibel RL, Ferrante AW Jr. Obesity is associated with macrophage accumulation in adipose tissue. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:1796–1808. doi: 10.1172/JCI19246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hong WK, Sporn MB. Recent advances in chemoprevention of cancer. Science. 1997;278:1073–1077. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5340.1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Guinane CM, Cotter PD. Role of the gut microbiota in health and chronic gastrointestinal disease: understanding a hidden metabolic organ. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2013;6:295–308. doi: 10.1177/1756283X13482996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Korecka A, Arulampalam V. The gut microbiome: scourge, sentinel or spectator? J Oral Microbiol. 2012:4. doi: 10.3402/jom.v4i0.9367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kurokawa K, Itoh T, Kuwahara T, Oshima K, Toh H, Toyoda A, Takami H, Morita H, Sharma VK, Srivastava TP, Taylor TD, Noguchi H, Mori H, Ogura Y, Ehrlich DS, Itoh K, Takagi T, Sakaki Y, Hayashi T, Hattori M. Comparative metagenomics revealed commonly enriched gene sets in human gut microbiomes. DNA Res. 2007;14:169–181. doi: 10.1093/dnares/dsm018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ardissone AN, de la Cruz DM, Davis-Richardson AG, Rechcigl KT, Li N, Drew JC, Murgas-Torrazza R, Sharma R, Hudak ML, Triplett EW, Neu J. Meconium microbiome analysis identifies bacteria correlated with premature birth. PLoS One. 2014;9:e90784. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0090784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Owaga E, Hsieh RH, Mugendi B, Masuku S, Shih CK, Chang JS. Th17 Cells as Potential Probiotic Therapeutic Targets in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2015;16:20841–20858. doi: 10.3390/ijms160920841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Francino MP. Early development of the gut microbiota and immune health. Pathogens. 2014;3:769–790. doi: 10.3390/pathogens3030769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hooper LV, Gordon JI. Commensal host-bacterial relationships in the gut. Science. 2001;292:1115–1118. doi: 10.1126/science.1058709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Belkaid Y, Hand TW. Role of the microbiota in immunity and inflammation. Cell. 2014;157:121–141. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Koh A, De Vadder F, Kovatcheva-Datchary P, Bäckhed F. From Dietary Fiber to Host Physiology: Short-Chain Fatty Acids as Key Bacterial Metabolites. Cell. 2016;165:1332–1345. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.05.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Luu M, Weigand K, Wedi F, Breidenbend C, Leister H, Pautz S, Adhikary T, Visekruna A. Regulation of the effector function of CD8+ T cells by gut microbiota-derived metabolite butyrate. Sci Rep. 2018;8:14430. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-32860-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kespohl M, Vachharajani N, Luu M, Harb H, Pautz S, Wolff S, Sillner N, Walker A, Schmitt-Kopplin P, Boettger T, Renz H, Offermanns S, Steinhoff U, Visekruna A. The Microbial Metabolite Butyrate Induces Expression of Th1-Associated Factors in CD4+ T Cells. Front Immunol. 2017;8:1036. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hirt C, Eppenberger-Castori S, Sconocchia G, Iezzi G, Tornillo L, Terracciano L, Spagnoli GC, Droeser RA. Colorectal carcinoma infiltration by myeloperoxidase-expressing neutrophil granulocytes is associated with favorable prognosis. Oncoimmunology. 2013;2:e25990. doi: 10.4161/onci.25990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Niccolai E, Cappello P, Taddei A, Ricci F, D’Elios MM, Benagiano M, Bechi P, Bencini L, Ringressi MN, Coratti A, Cianchi F, Bonello L, Di Celle PF, Prisco D, Novelli F, Amedei A. Peripheral ENO1-specific T cells mirror the intratumoral immune response and their presence is a potential prognostic factor for pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Int J Oncol. 2016;49:393–401. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2016.3524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Thorburn AN, Macia L, Mackay CR. Diet, metabolites, and “western-lifestyle” inflammatory diseases. Immunity. 2014;40:833–842. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Dorrestein PC, Mazmanian SK, Knight R. Finding the missing links among metabolites, microbes, and the host. Immunity. 2014;40:824–832. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Gomes SD, Oliveira CS, Azevedo-Silva J, Casanova M, Barreto J, Pereira H, Chaves S, Rodrigues L, Casal M, Corte-Real M, Baltazar F, Preto A. The Role of Diet Related Short-Chain Fatty Acids in Colorectal Cancer Metabolism and Survival: Prevention and Therapeutic Implications. Curr Med Chem. 2018 doi: 10.2174/0929867325666180530102050. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Smith PM, Howitt MR, Panikov N, Michaud M, Gallini CA, Bohlooly-Y M, Glickman JN, Garrett WS. The microbial metabolites, short-chain fatty acids, regulate colonic Treg cell homeostasis. Science. 2013;341:569–573. doi: 10.1126/science.1241165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Furusawa Y, Obata Y, Fukuda S, Endo TA, Nakato G, Takahashi D, Nakanishi Y, Uetake C, Kato K, Kato T, Takahashi M, Fukuda NN, Murakami S, Miyauchi E, Hino S, Atarashi K, Onawa S, Fujimura Y, Lockett T, Clarke JM, Topping DL, Tomita M, Hori S, Ohara O, Morita T, Koseki H, Kikuchi J, Honda K, Hase K, Ohno H. Commensal microbe-derived butyrate induces the differentiation of colonic regulatory T cells. Nature. 2013;504:446–450. doi: 10.1038/nature12721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Arpaia N, Campbell C, Fan X, Dikiy S, van der Veeken J, deRoos P, Liu H, Cross JR, Pfeffer K, Coffer PJ, Rudensky AY. Metabolites produced by commensal bacteria promote peripheral regulatory T-cell generation. Nature. 2013;504:451–455. doi: 10.1038/nature12726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sasada T, Kimura M, Yoshida Y, Kanai M, Takabayashi A. CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells in patients with gastrointestinal malignancies: possible involvement of regulatory T cells in disease progression. Cancer. 2003;98:1089–1099. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Takiishi T, Fenero CIM, Câmara NOS. Intestinal barrier and gut microbiota: Shaping our immune responses throughout life. Tissue Barriers. 2017;5:e1373208. doi: 10.1080/21688370.2017.1373208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Russo E, Taddei A, Ringressi MN, Ricci F, Amedei A. The interplay between the microbiome and the adaptive immune response in cancer development. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2016;9:594–605. doi: 10.1177/1756283X16635082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Russo E, Bacci G, Chiellini C, Fagorzi C, Niccolai E, Taddei A, Ricci F, Ringressi MN, Borrelli R, Melli F, Miloeva M, Bechi P, Mengoni A, Fani R, Amedei A. Preliminary Comparison of Oral and Intestinal Human Microbiota in Patients with Colorectal Cancer: A Pilot Study. Front Microbiol. 2018;8:2699. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.02699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Mu Q, Kirby J, Reilly CM, Luo XM. Leaky Gut As a Danger Signal for Autoimmune Diseases. Front Immunol. 2017;8:598. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Chen Z, Chen J, Collins R, Guo Y, Peto R, Wu F, Li L China Kadoorie Biobank (CKB) collaborative group. China Kadoorie Biobank of 0.5 million people: survey methods, baseline characteristics and long-term follow-up. Int J Epidemiol. 2011;40:1652–1666. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyr120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wu QJ, Yang Y, Vogtmann E, Wang J, Han LH, Li HL, Xiang YB. Cruciferous vegetables intake and the risk of colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:1079–1087. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.El Sohaimy SA. Functional Foods and Nutraceuticals-Modern Approach to Food Science. World Applied Sciences Journal. 2012;20:691–708. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Hill C, Guarner F, Reid G, Gibson GR, Merenstein DJ, Pot B, Morelli L, Canani RB, Flint HJ, Salminen S, Calder PC, Sanders ME. Expert consensus document. The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics consensus statement on the scope and appropriate use of the term probiotic. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;11:506–514. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2014.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Raman M, Ambalam P, Kondepudi KK, Pithva S, Kothari C, Patel AT, Purama RK, Dave JM, Vyas BR. Potential of probiotics, prebiotics and synbiotics for management of colorectal cancer. Gut Microbes. 2013;4:181–192. doi: 10.4161/gmic.23919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Liévin-Le Moal V, Servin AL. Anti-infective activities of lactobacillus strains in the human intestinal microbiota: from probiotics to gastrointestinal anti-infectious biotherapeutic agents. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2014;27:167–199. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00080-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Yeh TL, Shih PC, Liu SJ, Lin CH, Liu JM, Lei WT, Lin CY. The influence of prebiotic or probiotic supplementation on antibody titers after influenza vaccination: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2018;12:217–230. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S155110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Tarantino G, Finelli C. Systematic review on intervention with prebiotics/probiotics in patients with obesity-related nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Future Microbiol. 2015;10:889–902. doi: 10.2217/fmb.15.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Plaudis H, Pupelis G, Zeiza K, Boka V. Early low volume oral synbiotic/prebiotic supplemented enteral stimulation of the gut in patients with severe acute pancreatitis: a prospective feasibility study. Acta Chir Belg. 2012;112:131–138. doi: 10.1080/00015458.2012.11680811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Barichella M, Pacchetti C, Bolliri C, Cassani E, Iorio L, Pusani C, Pinelli G, Privitera G, Cesari I, Faierman SA, Caccialanza R, Pezzoli G, Cereda E. Probiotics and prebiotic fiber for constipation associated with Parkinson disease: An RCT. Neurology. 2016;87:1274–1280. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000003127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Hendler R, Zhang Y. Probiotics in the Treatment of Colorectal Cancer. Medicines (Basel) 2018:5. doi: 10.3390/medicines5030101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Russo E, Amedei A. The Role of the Microbiota in the Genesis of Gastrointestinal Cancers. In: Frontiers in Anti-Cancer Drug Discovery, 7th ed; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Mego M, Chovanec J, Vochyanova-Andrezalova I, Konkolovsky P, Mikulova M, Reckova M, Miskovska V, Bystricky B, Beniak J, Medvecova L, Lagin A, Svetlovska D, Spanik S, Zajac V, Mardiak J, Drgona L. Prevention of irinotecan induced diarrhea by probiotics: A randomized double blind, placebo controlled pilot study. Complement Ther Med. 2015;23:356–362. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2015.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Delia P, Sansotta G, Donato V, Frosina P, Messina G, De Renzis C, Famularo G. Use of probiotics for prevention of radiation-induced diarrhea. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:912–915. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i6.912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Gamallat Y, Meyiah A, Kuugbee ED, Hago AM, Chiwala G, Awadasseid A, Bamba D, Zhang X, Shang X, Luo F, Xin Y. Lactobacillus rhamnosus induced epithelial cell apoptosis, ameliorates inflammation and prevents colon cancer development in an animal model. Biomed Pharmacother. 2016;83:536–541. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2016.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Kuugbee ED, Shang X, Gamallat Y, Bamba D, Awadasseid A, Suliman MA, Zang S, Ma Y, Chiwala G, Xin Y, Shang D. Structural Change in Microbiota by a Probiotic Cocktail Enhances the Gut Barrier and Reduces Cancer via TLR2 Signaling in a Rat Model of Colon Cancer. Dig Dis Sci. 2016;61:2908–2920. doi: 10.1007/s10620-016-4238-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Manuzak JA, Hensley-McBain T, Zevin AS, Miller C, Cubas R, Agricola B, Gile J, Richert-Spuhler L, Patilea G, Estes JD, Langevin S, Reeves RK, Haddad EK, Klatt NR. Enhancement of Microbiota in Healthy Macaques Results in Beneficial Modulation of Mucosal and Systemic Immune Function. J Immunol. 2016;196:2401–2409. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1502470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Kahouli I, Tomaro-Duchesneau C, Prakash S. Probiotics in colorectal cancer (CRC) with emphasis on mechanisms of action and current perspectives. J Med Microbiol. 2013;62:1107–1123. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.048975-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Chong ES. A potential role of probiotics in colorectal cancer prevention: review of possible mechanisms of action. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2014;30:351–374. doi: 10.1007/s11274-013-1499-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Scientific concepts of functional foods in Europe. Consensus document. Br J Nutr. 1999;81 Suppl 1:S1–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Reig AD, Anesto J. Prebióticos y probióticos, una relación beneficiosa. Rev Cuba Aliment Nutr. 2002;16:63–68. [Google Scholar]

- 108.Delcenserie V, Martel D, Lamoureux M, Amiot J, Boutin Y, Roy D. Immunomodulatory effects of probiotics in the intestinal tract. Curr Issues Mol Biol. 2008;10:37–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Ambalam P, Raman M, Purama RK, Doble M. Probiotics, prebiotics and colorectal cancer prevention. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2016;30:119–131. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2016.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Salehipour Z, Haghmorad D, Sankian M, Rastin M, Nosratabadi R, Soltan Dallal MM, Tabasi N, Khazaee M, Nasiraii LR, Mahmoudi M. Bifidobacterium animalis in combination with human origin of Lactobacillus plantarum ameliorate neuroinflammation in experimental model of multiple sclerosis by altering CD4+ T cell subset balance. Biomed Pharmacother. 2017;95:1535–1548. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2017.08.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Niccolai E, Ricci F, Russo E, Nannini G, Emmi G, Taddei A, Ringressi MN, Melli F, Miloeva M, Cianchi F, Bechi P, Prisco D, Amedei A. The Different Functional Distribution of “Not Effector” T Cells (Treg/Tnull) in Colorectal Cancer. Front Immunol. 2017;8:1900. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Pandey KR, Naik SR, Vakil BV. Probiotics, prebiotics and synbiotics- a review. J Food Sci Technol. 2015;52:7577–7587. doi: 10.1007/s13197-015-1921-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Sivan A, Corrales L, Hubert N, Williams JB, Aquino-Michaels K, Earley ZM, Benyamin FW, Lei YM, Jabri B, Alegre ML, Chang EB, Gajewski TF. Commensal Bifidobacterium promotes antitumor immunity and facilitates anti-PD-L1 efficacy. Science. 2015;350:1084–1089. doi: 10.1126/science.aac4255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.de Moreno de LeBlanc A, Matar C, Perdigón G. The application of probiotics in cancer. Br J Nutr. 2007;98 Suppl 1:S105–S110. doi: 10.1017/S0007114507839602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Chen CC, Lin WC, Kong MS, Shi HN, Walker WA, Lin CY, Huang CT, Lin YC, Jung SM, Lin TY. Oral inoculation of probiotics Lactobacillus acidophilus NCFM suppresses tumour growth both in segmental orthotopic colon cancer and extra-intestinal tissue. Br J Nutr. 2012;107:1623–1634. doi: 10.1017/S0007114511004934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Mego M, Holec V, Drgona L, Hainova K, Ciernikova S, Zajac V. Probiotic bacteria in cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy and radiation therapy. Complement Ther Med. 2013;21:712–723. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2013.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Wang YH, Yao N, Wei KK, Jiang L, Hanif S, Wang ZX, Pei CX. The efficacy and safety of probiotics for prevention of chemoradiotherapy-induced diarrhea in people with abdominal and pelvic cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2016;70:1246–1253. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2016.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Osterlund P, Ruotsalainen T, Korpela R, Saxelin M, Ollus A, Valta P, Kouri M, Elomaa I, Joensuu H. Lactobacillus supplementation for diarrhoea related to chemotherapy of colorectal cancer: a randomised study. Br J Cancer. 2007;97:1028–1034. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Urbancsek H, Kazar T, Mezes I, Neumann K. Results of a double-blind, randomized study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of Antibiophilus in patients with radiation-induced diarrhoea. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2001;13:391–396. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200104000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Kane KF, Langman MJ, Williams GR. Antiproliferative responses to two human colon cancer cell lines to vitamin D3 are differently modified by 9-cis-retinoic acid. Cancer Res. 1996;56:623–632. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Muscat JE, Wynder EL. The consumption of well-done red meat and the risk of colorectal cancer. Am J Public Health. 1994;84:856–858. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.5.856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Le Marchand L, Hankin JH, Wilkens LR, Pierce LM, Franke A, Kolonel LN, Seifried A, Custer LJ, Chang W, Lum-Jones A, Donlon T. Combined effects of well-done red meat, smoking, and rapid N-acetyltransferase 2 and CYP1A2 phenotypes in increasing colorectal cancer risk. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2001;10:1259–1266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Roberfroid M. Prebiotics: the concept revisited. J Nutr. 2007;137:830S–837S. doi: 10.1093/jn/137.3.830S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Gibson GR, Probert HM, Loo JV, Rastall RA, Roberfroid MB. Dietary modulation of the human colonic microbiota: updating the concept of prebiotics. Nutr Res Rev. 2004;17:259–275. doi: 10.1079/NRR200479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Bruno-Barcena JM, Azcarate-Peril MA. Galacto-oligosaccharides and Colorectal Cancer: Feeding our Intestinal Probiome. J Funct Foods. 2015;12:92–108. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2014.10.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Femia AP, Luceri C, Dolara P, Giannini A, Biggeri A, Salvadori M, Clune Y, Collins KJ, Paglierani M, Caderni G. Antitumorigenic activity of the prebiotic inulin enriched with oligofructose in combination with the probiotics Lactobacillus rhamnosus and Bifidobacterium lactis on azoxymethane-induced colon carcinogenesis in rats. Carcinogenesis. 2002;23:1953–1960. doi: 10.1093/carcin/23.11.1953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Rowland IR, Rumney CJ, Coutts JT, Lievense LC. Effect of Bifidobacterium longum and inulin on gut bacterial metabolism and carcinogen-induced aberrant crypt foci in rats. Carcinogenesis. 1998;19:281–285. doi: 10.1093/carcin/19.2.281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Aachary AA, Prapulla SG. Xylooligosaccharides (XOS) as an emerging prebiotic: microbial synthesis, utilization, structural characterization, bioactive properties, and applications. Comp Rev Food Sci Food Saf. 2011;10:2e16. [Google Scholar]

- 129.Birt DF, Boylston T, Hendrich S, Jane JL, Hollis J, Li L, McClelland J, Moore S, Phillips GJ, Rowling M, Schalinske K, Scott MP, Whitley EM. Resistant starch: promise for improving human health. Adv Nutr. 2013;4:587–601. doi: 10.3945/an.113.004325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Wijnands MV, Schoterman HC, Bruijntjes JB, Hollanders VM, Woutersen RA. Effect of dietary galacto-oligosaccharides on azoxymethane-induced aberrant crypt foci and colorectal cancer in Fischer 344 rats. Carcinogenesis. 2001;22:127–132. doi: 10.1093/carcin/22.1.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Hsu CK, Liao JW, Chung YC, Hsieh CP, Chan YC. Xylooligosaccharides and fructooligosaccharides affect the intestinal microbiota and precancerous colonic lesion development in rats. J Nutr. 2004;134:1523–1528. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.6.1523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Bauer-Marinovic M, Florian S, Müller-Schmehl K, Glatt H, Jacobasch G. Dietary resistant starch type 3 prevents tumor induction by 1,2-dimethylhydrazine and alters proliferation, apoptosis and dedifferentiation in rat colon. Carcinogenesis. 2006;27:1849–1859. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgl025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Gourineni VP, Verghese M, Boateng J, Shackelford L, Bhat NK, Walker LT. Combinational Effects of Prebiotics and Soybean against Azoxymethane-Induced Colon Cancer In Vivo. J Nutr Metab. 2011;2011:868197. doi: 10.1155/2011/868197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Hijova E, Szabadosova V, Strojny L, Bomba A. Changes chemopreventive markers in colorectal cancer development after inulin supplementation. Bratisl Lek Listy. 2014;115:76–79. doi: 10.4149/bll_2014_016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]