Abstract

The detectability of target sounds embedded within noisy backgrounds is affected by the regularities that summarize acoustic sceneries. Previous studies suggested that the dynamic range of neurons in the inferior colliculus (IC) of anesthetized guinea pigs shifts toward the mean sound pressure level in irregular acoustic environments. Yet, it is unclear how this neuronal adaptation processes may influence the effectiveness of sounds as a masker, both behaviorally and in terms of neuronal encoding. To answer this question, we measured the neural response of IC neurons while macaque monkeys performed a Go/No-Go tone detection task. Macaques detected a 50-ms tone that was either simultaneously gated with a burst of noise or embedded within a continuous noise background, whose levels were randomly sampled (every 50 ms) from a probability distribution. The mean of the distribution matched the level of the gated burst of noise. Psychometric and IC neurometric thresholds to tones did not differ between the two masking conditions. However, the neuronal firing rate versus level function was significantly affected by the temporal characteristics of the noise masker. Simultaneously gated noise caused higher baseline responses and greater dynamic range compression compared with noise distribution. The slopes of psychometric and neurometric functions were significantly shallower for higher variance distributions, suggesting that neuronal sensitivity might change with the variability of the sound. Our results suggest that the adaptive response of IC neurons to sound regularities does not affect the effectiveness of the noise-masking signal, which remains invariant to surrounding noise amplitudes.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY Auditory neurons adapt to the statistics of sound levels in the acoustic scene. However, it is still unclear to what extent such adaptation influences the effectiveness of the stimulus as a masker. Our study represents the first attempt to investigate how the adaptation to the statistics of masking stimuli may be related to the effectiveness of masking, and to the single-unit encoding of the midbrain auditory neurons in behaving animals.

Keywords: behaving macaques, dynamic range compression, inferior colliculus, neuronal adaptation, sound statistics

INTRODUCTION

The detectability of target sounds embedded in noise is affected by the regularities that summarize complex acoustic environments (Bregman 1990). Natural acoustic scenes are characterized by stimuli that may vary over a wide range of sound levels over time. How do auditory neurons accurately encode the variety of changes that occur within acoustic images? A potential solution to this problem has been proposed in terms of an adaptive response of auditory neurons to the sound regularities that are most likely to be presented (e.g., Dean et al. 2005, 2008; Kvale and Schreiner 2004; Rabinowitz et al. 2013; Watkins and Barbour 2008; Wen et al. 2009). Such adaptation to the sound (noise) statistics (e.g., the mean or the variance of the noise levels) has been shown to cause a shift of the neuronal dynamic range toward the mean parameter, such that the neuronal response to a specific sound level in an irregular environment may differ from that elicited by the same stimulus in isolation.

Yet, it is unclear whether and how this adaptation process can influence the effectiveness of noise-masking signals with distinct temporal properties. Early physiological work in anesthetized animals suggested that broadband noise maskers caused similar dynamic range shifts in the responses of auditory nerve fibers, irrespective of whether noise was simultaneously gated with the tone or presented continuously (Costalupes et al. 1984). However, the two conditions were characterized by very different neuronal response magnitudes after adaptation to the statistics of the stimuli: in the simultaneously gated noise condition the response rate differences between levels that led to saturation and no response (baseline activity) were lower compared with those observed when the noise was on continuously. These results suggest that the temporal characteristics of the noise masker may affect the response profiles of neurons in the auditory nerve fibers and in the IC. The adaptation to frequent sounds might help the auditory system to maintain the neuronal sensitivity in face of masking, leading to a noise-invariant representation of sounds. It is also unclear if and how the temporal properties of the background sound environment surrounding the masked signal (i.e., the noise amplitudes preceding the masked signal) affect neuronal response to sounds. Does the adaptive response to stimulus regularities have an impact on behavioral accuracy in detection tasks? The lack of work conducted in behaving animals does not allow direct comparisons between the behavioral and the neurophysiological patterns of response. Thus, the perceptual consequences of this neuronal adaptation process are still unknown.

Here we report results of studies investigating how neuronal adaptation to the statistics of masking background noise may influence signal detection in behaving macaques, and how this affects the underlying neuronal correlates. It is well established that the IC is an important synaptic station in both ascending and descending auditory pathways (e.g., Casseday et al. 2002; Malmierca 2005). However, it is still unclear to what extent the adaptation of single neurons to the regularities of the noise environment might influence sound detection. Does the effectiveness of broadband noise maskers depend on the statistical regularities of the acoustic image? Our results indicate that the responses of IC neurons to tones are affected by the characteristics of the noise surrounding (preceding and following) the target. However, psychometric and IC neurometric thresholds to tones were not affected by the neuronal adaptation to backgrounds statistics. On the contrary, reaction times (RTs) were significantly longer when neurons adapted to the regularities of the background noise. Interestingly, the variability characterizing the auditory scene caused a significant change in the sensitivity with which auditory neurons encoded sounds.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The studies reported here were conducted using procedures approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee at the Vanderbilt University Medical Center, and are in strict compliance with the guidelines established by the National Institutes of Health for working with animals.

Subjects and Surgical Procedures

Two male monkeys (one Macaca mulatta and one Macaca radiata, 8 and 10 yr old, respectively, at the beginning of the study) were used as subjects in these studies. These macaques were subject to two surgical procedures conducted under anesthesia and using sterile procedure to prepare them for the experimental studies. During the first procedure, a plastic or titanium head holder (Crist Instruments, Hagerstown, MD) was implanted on the skull of the monkey by using 8-mm-long stainless-steel screws (Veterinary Orthopedic Implants, Buffalo Grove, IL) and bone cement (Zimmer Biomet, Warsaw, IN). The second surgery was to implant a recording chamber (Crist Instruments) on the head, around a craniotomy at a stereotactically guided location. The chamber was tilted laterally 20° and fit to the skull such that an electrode passing radially through the chamber would enter into the IC. Analgesics and, if necessary, antibiotics were provided before and after the surgical procedures under close veterinary supervision, and the macaques were monitored through recovery.

Apparatus and Stimuli

The apparatus has been described in detail earlier (Bohlen et al. 2014; Dylla et al. 2013). Experiments were conducted on trained macaques seated comfortably in an acrylic primate chair (audio chair, Crist Instruments) placed in a sound treated booth (model 1200, Industrial Acoustic, NY). The head of the monkey was fixed to the chair by means of the surgically implanted head holder and was located 90.1 cm from the speaker (SA1 speaker, Madisound, Middleton, WI), which could play a range of frequencies spanning between 0.05 and 40 kHz. A 1/4-in. probe microphone (model 378C01, PCB Piezotronics, Depew, NY) was employed to calibrate the speaker, and showed that sounds varied by ±3 dB or less from the sound level expected over that frequency range.

Experiments were controlled by using a computer running OpenEx software (System 3 TDT, Alachua, FL). The sampling rate used to generate the signals was 97.6 kHz. Tones were generated using the formula S(t) = A* Sin (2πft), where S(t) represents the signal, A indicates the amplitude and f the carrier frequency, respectively. Noise was generated using functions created by TDT. Each broadband noise token (N(t)) was a flat-spectrum noise (band-limited to 40 kHz) created by using the “Random” function in OpenEx. Noise levels in dB sound pressure level (SPL) spectrum level were computed by subtracting 10*log10 (bandwidth) from that overall level in dB SPL. Full description of the apparatus used to generate signals is extensively explained in previous work (Dylla et al. 2013).

Behavioral Task

Monkeys were trained to perform a reaction time lever release Go/No-Go task where a 50-ms tone (5-ms-rise/fall times) masked by noise had to be detected. Monkeys initiated the task by pressing a lever (single-axis Hall effect joystick, P3America, San Diego, CA). The lever state was sampled at a rate of 24.4 kHz, with a temporal resolution of ~40 µs. Each testing session was composed of either signal trials (with target tones presented) or catch trials (only noise was played). After a variable delay (400–1,400 ms), a tone was presented on 80% of the trials (signal trial). A correct response (hit, lever release) within 600 ms after the signal onset led to a positive reinforcement (fluid reward). There were no rewards and no penalties for not releasing the lever when the signal was presented (miss). On the remaining 20% of trials, no tone was played (catch trials). If the lever was released on catch trials (false alarm), a time-out penalty was assigned [tones were not presented for a variable temporal window (between 6 and 10 s)]. A correct nonrelease was not rewarded but was typically followed by a signal at a higher sound level on the next signal trial. Further details about this Go/No-Go task can be found in Dylla et al. (2013).

The method of constant stimuli was employed to measure detection thresholds. Tone levels were presented in a random sequence. The range of sounds played was centered on a chosen threshold value (within ±35 dB SPL), and the step size between tone levels was either 2.5 or 5 dB SPL. The tone frequency chosen in the psychophysical part of the study was 4,000 Hz, whereas the frequency used in the tasks performed during recordings always coincided with the characteristic frequency (CF) of the neurons isolated. In the psychophysical experimental section, monkeys generated, minimally, between 360 and 390 data points in total for each condition. During the electrophysiological experiments, the typical number of behavioral data points collected for each neuron was at least 195 per condition. The overall duration of each condition in an experimental session (stimulus run) was 11 min on average, depending on the number of tone repetitions and their step size. Tones were presented within different noise backgrounds as described below. Noise levels ranged from −20 to 50 dB SPL spectrum level.

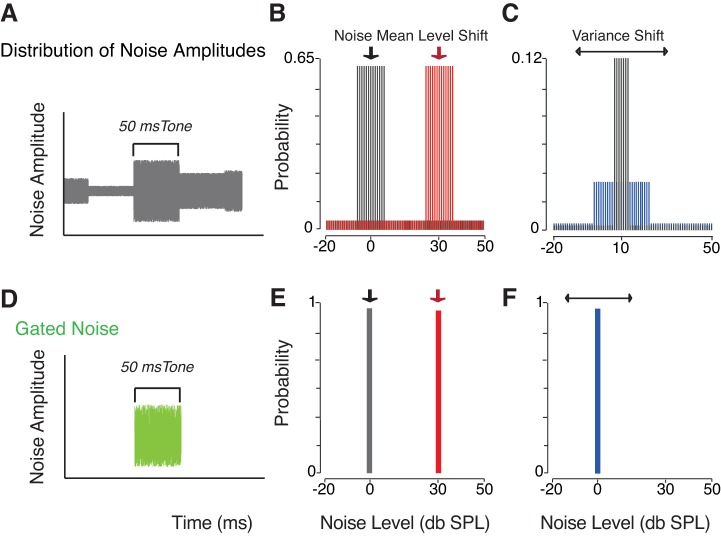

Psychophysical Experiments

The noise masker used was either continuous noise having a single amplitude (steady state), a burst of noise turned on and off simultaneously with the signal (simultaneously gated noise), or continuous noise background with levels drawn randomly (every 50 ms) from probability distributions (Fig. 1) similar to those designed by Dean et al. (2005). The noise distributions used were composed of high and low probability regions, and were characterized by specific statistical properties (i.e., the mean level or the variance of the high-probability region). The mean level of the noise distribution (defined as the centroid of the high-probability region) always matched the noise level used in the simultaneously gated noise condition, and was consistently used to mask the tone signal. In this part of the study, the centroid of the high-probability region was either 0, 10, 20, or 30 dB SPL spectrum level. Figure 1B shows two examples of distributions centered on 0 and 30 dB SPL spectrum level. The width of high-probability region (i.e., variance) was typically kept constant at 12 dB SPL (with the exception of the condition where the variance was manipulated). Detection thresholds measured when the background was composed of a distribution of noise amplitudes were compared with both those observed when a 50 ms burst of broadband noise was simultaneously gated with the tone (simultaneously gated noise), and to the thresholds measured in continuous (steady-state) noise. The relationship between the variability within the masker’s acoustic image and listeners’ performance was investigated by measuring threshold shifts to tones when the target was embedded in three noise distributions, each characterized by distinct widths (variance) of the high-probability regions. In this condition, noise amplitudes always had the same mean (10 dB SPL) and the variance was manipulated (6, 12, or 24 dB SPL) Fig. 1C shows two examples of distributions where the mean was constant while the variance was modified. The same range of noise levels was used for all the distributions designed in the present study, and spanned between −20 to 50 dB SPL spectrum level. In all the psychophysical conditions, tones (4,000 Hz) were masked by a noise level equal to the centroid of the high-probability region of the distributions (either 0, 10, 20, or 30 dB SPL).

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of the main stimulus paradigm. A: tone signal masked by a distribution of noise amplitudes that changed every 50 ms. The noise-time amplitude waveform is represented in gray. Tones were always played at the same noise amplitude for both the noise distribution and the gated noise conditions. B: examples of two distributions used to randomly sample noise amplitudes. The centroid of the high-probability region (i.e., mean) was shifted from 0 dB sound pressure level (SPL) (gray distribution) to 30 dB SPL (red distribution). C: examples of two distributions where the width of the high-probability region (i.e., variance) was manipulated, and the mean remained constant. The variance increased from 6 dB (gray distribution) to 24 dB SPL (blue distribution). The overall range of noise levels played did not vary. Details of the distributions used for each experimental condition are specified in the main text. D: gated noise condition. A 50-ms burst of noise (single noise amplitude represented in green) masked the tone. E: schematic example of two single noise amplitudes employed as a masker. F: the variance of the noise was always constant and equal to zero in the gated noise condition. Further details of the parameters used in both the psychophysical and the electrophysiological tests are summarized in materials and methods.

Neurophysiology

Recording methodology.

A glass-coated tungsten electrode (tip length ~7–10 μm, diameter ~5 μm; Alpha Omega Engineering, Alpharetta, GA) was placed in a 23-gallon stainless-steel guide tube and then advanced into the brain through a recording chamber. The first step was to lower manually the guide tube into the brain (~10 mm). Subsequently, a remotely controlled hydraulic micromanipulator (MO-97, Narishige, Hampstead, NY) was used to lower the electrode further into the brain and reach the IC. Bursts of noise were played as probe stimuli to determine proximity to the IC. Criteria to identify the IC were short latencies (≤20 ms), reliable nonhabituating responses (Nelson et al. 2009), and identification of presence in tonotopic gradient (e.g., Merzenich and Reid 1974). Single units were isolated using a range of tones played at a specific frequency (Davis 2002; Ramachandran et al. 1999). To isolate a unit, the percentage of interspike intervals of at least 700 μs was required to be greater than 95% (Nelson et al. 2009). A frequency response map (FRM) was computed to estimate the CF, that is, the frequency at which the neuron showed the lowest threshold of each isolated neuron and response type (after Ramachandran et al. 1999). Each FRM was expressed in terms of response of a single unit to tones as a function of frequency and sound level. The range of the frequencies used corresponded to 2 or 4 octaves around the estimated CF. The FRM was used to calculate the actual CF, which was typically not different from the estimated CF. The CF of the isolated neuron was subsequently used as the tone frequency also in the psychophysical and neurophysiological measurements. The raw waveform of the electrode signal and the waveform of spikes were sampled at 24.414 kHz and stored for offline analysis.

Electrophysiological study.

The behavioral task that the monkeys performed while neuronal activity was recorded from IC neurons was the same as the one outlined above. The only details that changed are explained in this section. Given that neurons could be held for a limited time, responses were sampled only with a noise level of 30 dB SPL spectrum level. Tones were always presented at the CF estimated for each single neuron. Neuronal responses of IC neurons to 50-ms tones were recorded when tone targets were either embedded in a distribution of noise amplitudes (mean 30 dB SPL spectrum level) or masked by bursts of noise (30 dB SPL spectrum level) that were simultaneously gated with the tone. For a few experimental sessions, the mean level of the distribution and the gated noise level were chosen to be 0 dB SPL spectrum level. Neuronal responses were also obtained when the variance of the distribution was either 6 or 24 dB SPL, while the means of these distributions were constant (mean level = 10 dB SPL spectrum level). As for the behavioral experiment, the overall duration of the stimulus run slightly changed depending on the number of repetitions for each tone level (typically 15) and their step size. However, the duration of each session was 11 min on average when tones were presented.

Behavioral Analysis

Signal detection theoretic methods (Green and Swets 1966; Macmillan and Creelman 2005) were employed to analyze behavioral data (see Dylla et al. 2013, for further details). The hit rates (H) and false alarm rates (F) for each tone level were estimated by using the following formula:

where z is the inverse of the normal distribution and converts hit rate and false alarm rate into normalized units of standard deviation (z-score, norminv in MATLAB) (Macmillan and Creelman 2005). The inverse z-transform ) converts a unique number of standard deviations of a standard normal distribution into a probability correct [pc(level), normcdf in MATLAB]. Psychometric functions were obtained by computing the pc for each tone level.

A Weibull cumulative distribution function (cdf) was used to fit the psychometric functions (see Britten et al. 1992; Palmer et al. 2007):

where level indicates the tone SPL, λ represents the threshold parameter of the function, and k corresponds to the slope. Parameters c and d represent the ceiling and floor saturation rates, respectively, and e is the base of natural logarithms (e = 2.71828). The SPL that corresponded to a fitted probability correct value of 0.76 (pcfit = 0.76) was calculated to be the detection threshold. The temporal delay between tone onset and lever release determined the RTs.

Neurophysiological Analysis

When necessary, a Bayesian spike-sorting algorithm (OpenSorter, TDT) was used to sort the neurophysiological data offline. Spikes occurring within the entire 200-ms tone duration in the FRMs were used to calculate the CF value. The computed CF value matched the estimated CF value more than 95% of the time.

In the neurophysiological experiments, on each trial the magnitude of response of each single neuron to the sound environment was calculated by cumulating the number of spikes evoked in response to the stimulus (burst of noise, tone embedded in noise, etc.). The behavioral accuracy predicted by the neuronal response was estimated by employing traditional receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis (e.g., Barlow et al. 1971; Britten et al. 1992; Palmer et al. 2007; Tolhurst et al. 1983). A distribution of response was generated for the neuronal response (total spike count evoked) to each tone level, including the condition when no signal was presented (catch trial condition). The two distributions of responses obtained for signal trials (at each SPL) and catch trials were compared with each other. Standard ROC analysis was used to estimate the neurometric probability that an ideal observer could discriminate between the two distinct conditions (Britten et al. 1992; Palmer et al. 2007). Each neurometric function (neurometric probability vs. tone level) was fitted with the Weibull cdf illustrated in the section Behavioral Analysis. The correlation between the magnitude of response of each neuron and the RTs was investigated by regressing the total spikes occurring within 50 ms of tone presentation against the RTs.

The rate level functions obtained when exploring the effects of mean sound level on detection were fit by using a modified form of the Naka-Rushton equation (Naka and Rushton 1966):

where Rmin and Rmax represent the minimum and maximum firing rate evoked by the tone in noise, respectively; x was the tone SPL, and x50 the SPL that corresponds to the “midpoint” (50% of the curve), where the firing rate is halfway between Rmin and Rmax. The parameter n indicates the steepness of the sigmoidal fit. For each neuron, the baseline activity (corresponding to the Rmin of the above function) obtained in the gated noise condition was compared with that recorded when the noise was composed of a distribution of amplitudes. For the units whose responses reached a saturation level, a relative rate compression of the rate level function was computed in both the gated and distribution (continuous noise) conditions by using the following equation:

where RminG and RmaxG are the minimum and maximum firing rates observed for tones in simultaneously gated noise bursts, and RminD and RmaxD correspond to the condition where tones were presented within a distribution of noise amplitudes.

To test the covariance of neuronal activity and behavioral activity, we utilized the choice probability metric (Britten et al. 1996). Since very few false alarms were observed, we used trials that had at least three correct and/or three incorrect responses in the middle of the behavioral dynamic range. The trials at the same tone SPL were sorted by behavioral outcome (hit or miss). The responses for these outcomes were separated and a ROC analysis was performed to estimate the probability that an ideal observer would predict the behavioral outcome based on the response magnitude. When the responses on correct and incorrect trials were the same, the choice probability (CP) was 0.5. A CP significantly larger than 0.5 indicates that a larger response on correct trials was recorded compared with incorrect trials, whereas CP significantly smaller than 0.5 describes the opposite trend (larger response on incorrect trials compared to correct trials). When multiple values of CP were available for a single unit (at least three correct and incorrect responses were available at multiple sound levels), a grand average CP was estimated by combining choice probabilities across tone levels after ensuring that the averaging did not hide a trend. The significance of the CP was assessed by comparing the grand average CP with the distribution of a random CP obtained by a permutation test (after Tsunada et al. 2016).

RESULTS

The IC neuronal data presented in this paper were obtained by recording from the tonotopic region of the IC. The CF of the single units gradually increased as the electrode traveled ventromedially, consistently with previous studies (see Oliver and Huerta 1992 for a review.). The physiological signatures observed (short latency auditory responses, the tonotopic gradient, and the FRM types) suggested that neuronal responses were recorded from the central nucleus of the IC. The response properties of the neurons reported in this paper could be classified as type V or type I, according to the patterns of excitation and inhibition observed as a function of tone frequency and level (after Ramachandran et al. 1999). The results describing how signal detectability is affected by variations of the mean sound level are based on recordings from 84 IC single units of two monkeys (D, n = 53; E, n = 31). The response profiles of 42 IC neurons were measured and analyzed (D, n = 31; E, n = 11) in the condition where the width of the high-probability region of the noise distribution (variance) was manipulated. We have grouped the results across the response types because no discernible differences were observed. There was no selection of specific neurons for inclusion into the study; all the well-isolated units that were studied were used. The pattern of response of each IC neuron encountered was analyzed and reported in this study.

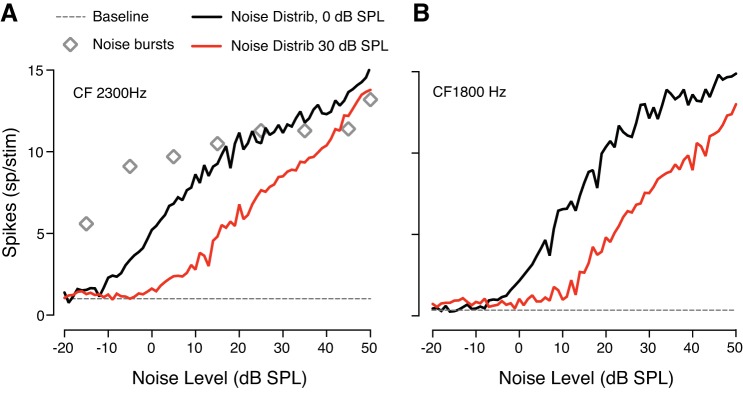

We initially conducted a preliminary experiment to replicate the results obtained in previous work (e.g., Dean at al. 2005), and to verify that responses of IC neurons in behaving macaques did adapt to noise levels when the acoustic stimulus was continuous noise with levels varying every 50 ms (as in Dean et al. 2005). Figure 2 shows the responses of two neurons with different CFs as a function of noise sound pressure levels (sampled from two different probability distributions centered on 0 and 30 dB SPL spectrum level). The neuronal dynamic range of both neurons shifted toward higher sound levels when the mean of the distribution was increased. To our knowledge, this is the first time that such adaptation mechanism has been shown in the IC of awake macaques. Open symbols (Fig. 2A) indicate the response of one neuron to bursts of noise as a function of noise SPL, and the dashed line shows the baseline response in absence of stimuli. Every neuron that we recorded from showed adaptation to the background sound level. These results suggest that neurons in the IC adapt to the mean SPL also in behaving macaques.

Fig. 2.

Responses of inferior colliculus (IC) units to two distributions of noise amplitudes [0 and 30 dB sound pressure level (SPL)]. Monkeys passively listed to band-limited white noise presented in absence of tone. Rate versus level functions adapt to the mean sound level also in awake, behaving subjects. A: firing rate for a neuron tuned to 2300 Hz. The black line shows neuronal response to a distribution of noise amplitudes centered on 0 dB SPL spectrum level. The red line represents the adapted response of the same neuron to a noise distribution with a mean level of 30 dB SPL spectrum level. Open symbols indicate the response of the same neuron to bursts of noise. The dashed line shows the baseline activity when no noise was played. B: response of an IC neuron with a characteristic frequency (CF) of 1800 Hz.

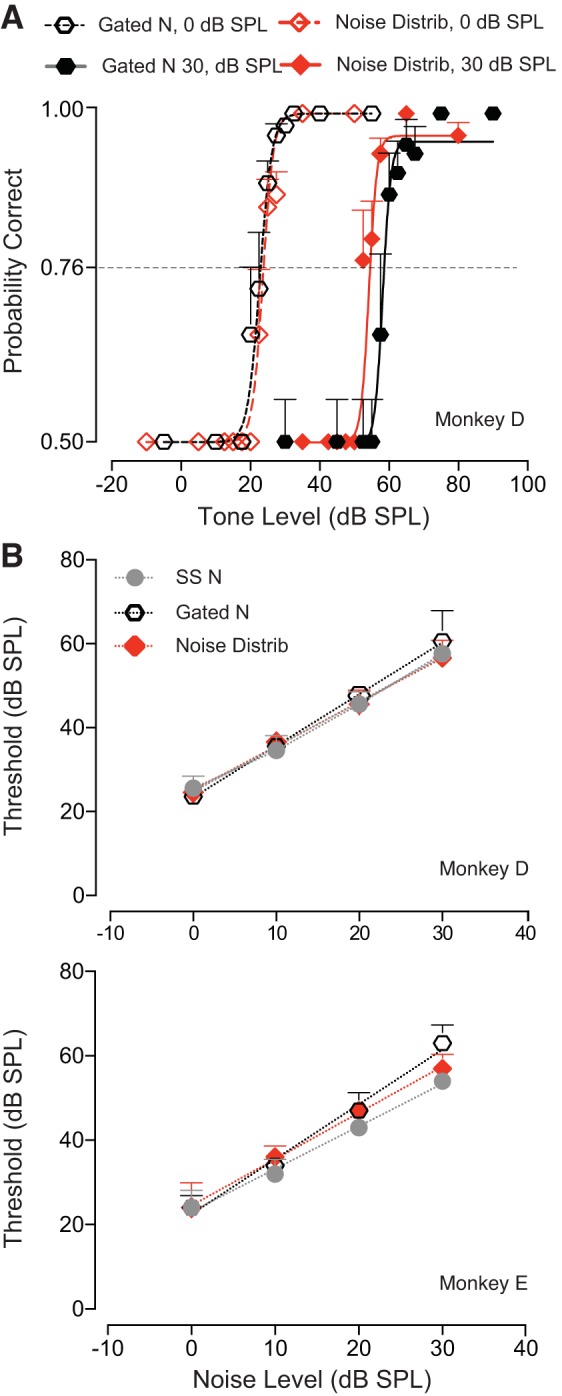

We also report the results of studies investigating the behavioral effects of such noise maskers in a tone detection task for the sessions in which no neurophysiological responses were measured. Behavioral performance was compared across three conditions where the signal-to-noise ratio was constant but the characteristics of the background noise varied (Fig. 3). Figure 3A shows examples of psychometric functions from monkey D. Detection thresholds increased as a function of the noise amplitude played. However, the behavioral performance was independent of the type of background noise used. Threshold shifts for gated noise (black symbols) and for the noise distributions (red symbols) were not significantly different from each other. Figure 3B summarizes the averaged thresholds for two monkeys. Behavioral performance appeared to be the same independently of the type of masking noise (steady-state noise, gated noise, or noise distribution). A two-way ANOVA confirmed that changes in the noise background characteristics did not lead to significant variations in thresholds [monkey D: F(2, 6) = 0.6316, P = 0.5637; monkey E: F(2, 6) = 2.967, P = 0.1271]. The behavioral performance was affected only by variations of the noise level used [monkey D: F(3, 6) = 295.5, P < 0.0001, monkey E: F(3, 6) = 127.4 P < 0.0001]. The variability between the two subjects was minimized given that the performance observed in the detection task was not significantly different between the two monkeys. A two-way ANOVA showed that detection thresholds were not significantly different between monkey D and monkey E for both the gated noise [gated noise threshold across subjects: F(1, 3) = 0.7714, P = 0.444] and the noise distribution [noise distribution thresholds across subjects: F(1, 3) = 2.455, P = 0.2152] conditions. As we have previously discussed, we did only observe a significant difference in detection thresholds when the noise level was varied (gated noise thresholds across subjects: F(3, 3) = 367.2, P = 0.0002; noise distribution across subjects: F(3, 3) = 841.7, P < 0.0001). These results are consistent with our recent study (Rocchi et al. 2017), showing no significant differences between tone detection thresholds with gated noise and continuous (steady-state) noise maskers.

Fig. 3.

Behavioral detection thresholds in the psychophysical tests. Effect of manipulating the mean of the distribution [either 0, 10, 20, or 30 dB sound pressure level (SPL)]. A: example of psychometric functions from monkey D. The symbols represent the data points, and the curve represents the Weibull function fit. The different colors indicate the type of noise used as masker, either gated noise (black symbols) or noise distribution (red symbols). B: averaged data for two monkeys (between 360 and 390 data points). Detection thresholds are plotted as a function of four noise levels. Data illustrates thresholds for different conditions. Three different noise types were presented: steady-state noise (gray symbols), gated noise (black symbols), and noise distribution (red symbols). Tone frequency was 4000 Hz. Error bars represent the 95% CI.

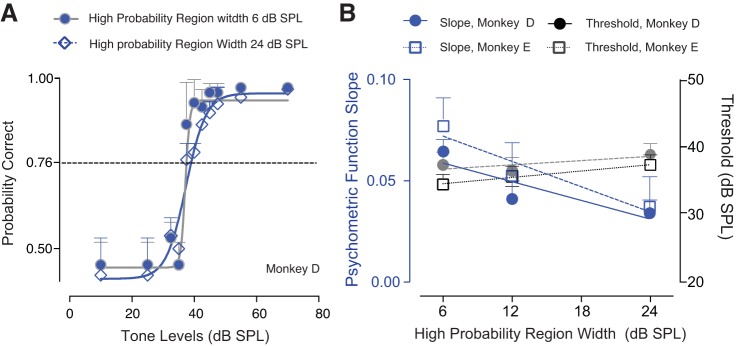

In a second set of behavioral experiments, we investigated how manipulating the variance of the distribution (the width of the high-probability region) could have an impact on the detection performance (Fig. 4). Figure 4A illustrates an example of two psychometric functions from monkey D obtained under these conditions. Thresholds to tones did not change as a function of the variance of the distribution. However, the slope of the psychometric function was shallower when the width of the high-probability region was relatively higher (24 dB, blue line), compared with when the width of the high-probability region of the noise distribution was relatively lower (6 dB, gray line). Averaged thresholds and slopes for two monkeys are summarized in Fig. 4B. A two-way ANOVA conducted on the overall data revealed that behavioral thresholds did not vary significantly as a function of the width of the high-probability region [F(2, 2) = 5.635, P = 0.1507]. No significant differences were observed across subjects [F(1, 2) = 8.335, P = 0.1020]. However, the slope of the psychometric function was significantly shallower when the variance of the noise distribution was higher [F(2, 2) = 50.96; P = 0.0192]. These results were consistent across monkeys [F(1, 2) = 9.474, P = 0.0913].

Fig. 4.

Behavioral detection thresholds in the psychophysical tests. Effect of changing the variance [the width of the high-probability region was either 6, 12, or 24 dB sound pressure level (SPL)]. A: example of two psychometric functions from monkey D. Closed symbols represent data when the variance of the noise distribution was 6 dB SPL; the open diamonds indicate a variance of 24 dB SPL. B: average psychometric function thresholds and slopes (between 360 and 390 data points) for two monkeys. Tone frequency was 4000 Hz. Error bars represent the 95% confidence interval.

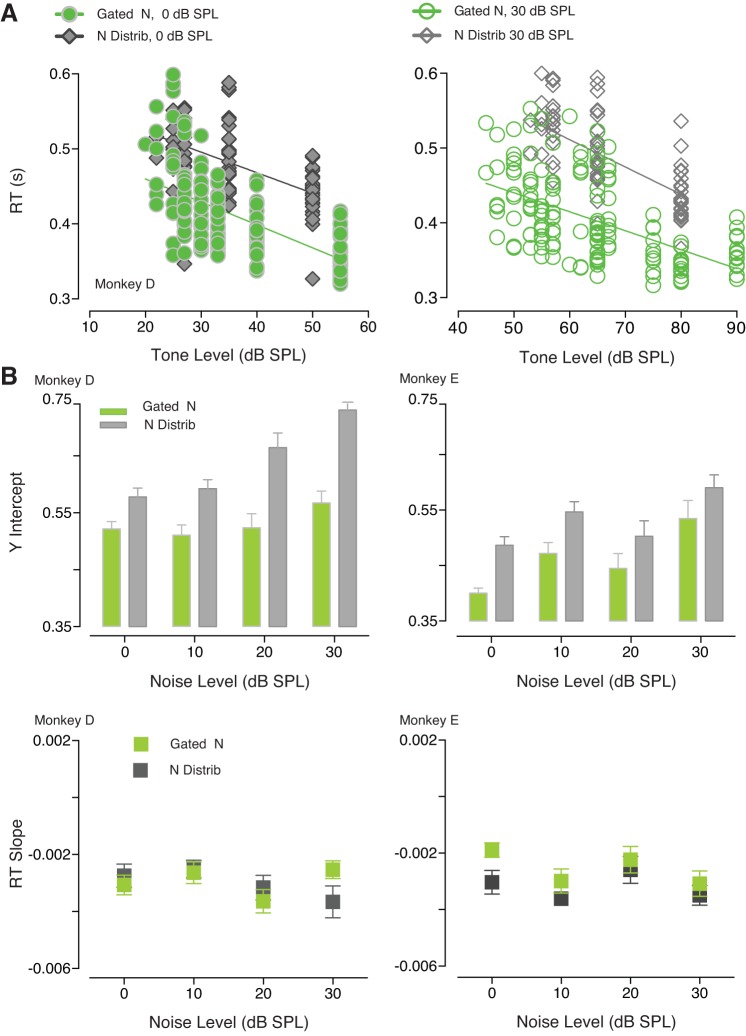

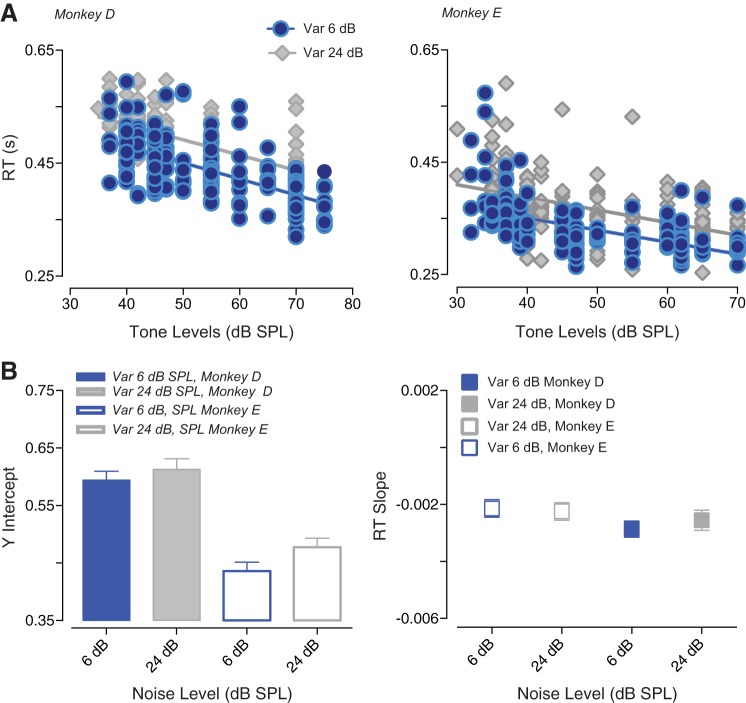

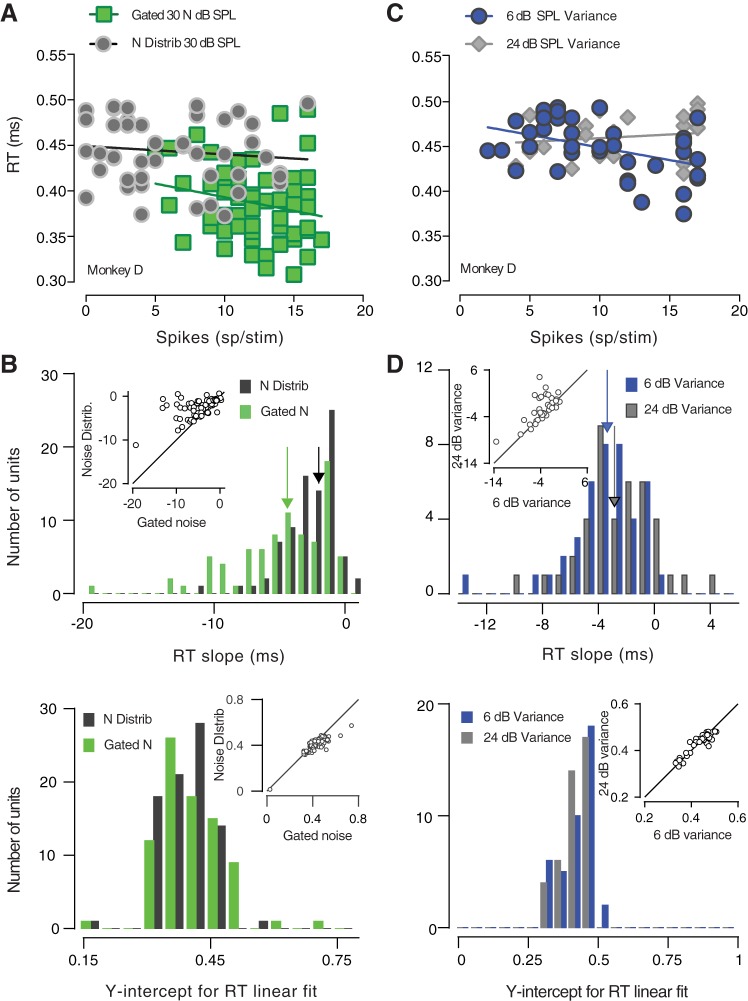

RT changes as a function of the noise background are shown in Fig. 5. Figure 5A shows differences in averaged RT (monkey D) depending on the type of noise presented (either gated noise or noise distribution) for two noise levels (0 and 30 dB SPL). RTs appeared to be shorter when tones were simultaneously gated with bursts of noise, compared with the condition where the signal was embedded in a distribution of noise amplitudes. Y-intercepts and RT slopes for all the noise levels are summarized in Fig. 5B. The y-intercept of the regression line was observed to be significantly lower for gated noise compared with noise distribution [monkey D: F(1, 3) = 19.64, P = 0.0213; monkey E: P = 0.025]. Variations in the noise level used caused a significant change in the y-intercept for one monkey [monkey D: F(3, 3) = 3.482, P = 0.1664; monkey E: P = 0.0047]. The RT slopes were not affected by the gating characteristics of the noise [monkey D: F(3, 3) = 0.8960, P = 0.5349; monkey E: F(3, 3) = 7.858, P = 0.0622]. Only for monkey E RT slopes were significantly steeper for low noise levels [monkey D: F(1, 3) = 0.01703, P = 0.9044; monkey E: F(1, 3) = 12.87, P = 0.0371]. The relationship between RTs and the characteristics of the background noise was explored also for the stimulus paradigm where we have investigated how the variability within the sound image affects tone detection. Figure 6A compares averaged RTs recorded when the width of the high-probability region was 6 dB SPL versus 24 dB SPL. RTs appeared to be shorter when the variability within the sound distribution was relatively low (6 dB SPL). However, a two-way ANOVA revealed that the y-intercept and the RT slope differences between the two conditions were not significant. The y-intercepts averaged across monkeys did not significantly change depending on the variance characterizing of the acoustic stimulus [F(1, 1) = 7.215; P = 0.2269]. The ANOVA only highlighted a difference between the two subjects [F(1, 1) = 173.2; P = 0.0483]. The RT slopes were not affected by the noise distribution [F(1, 1) = 1.331, P = 0.4546] or the variability across subjects [F(1, 1) = 1.841; P = 0.4043].

Fig. 5.

Reaction times (RTs) to tones as a function of tone levels for the two noise conditions. A: averaged RTs for monkey D. In panel at left, RTs recorded when 0 dB sound pressure level (SPL) bursts of noise were presented (green symbols) versus RTs observed when the noise masker consisted of a distribution of noise amplitudes (gray symbols). In panel at right, RTs are shown for noise levels of 30 dB SPL. B: summary of y-intercepts and RT slopes for both monkeys. Error bars represent the 95% confidence interval.

Fig. 6.

Reaction times (RTs) as a function of tone levels for two different variances (widths of the high-probability region). A: averaged data for two monkeys. Blue symbols show RTs for 6-dB variance, and gray symbols show RTs for 24-dB variance. B: summary of y-intercepts and RT slopes for both monkeys. Error bars represent the 95% confidence interval.

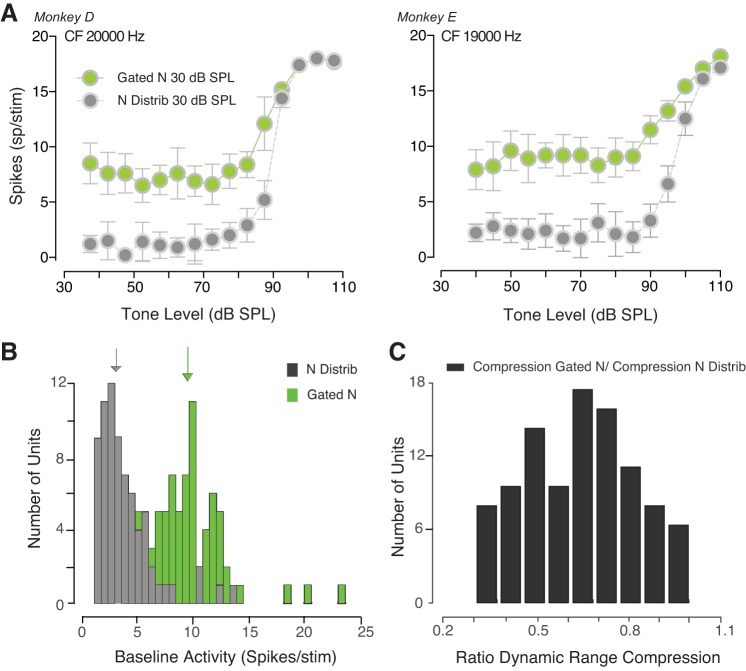

After having shown the relationship between behavioral sound detectability and the regularities within the acoustic scene, we explored the neuronal encoding of tones in two kinds of noise maskers. We measured the responses of IC neurons to different noise backgrounds (gated noise vs. noise distribution) in behaving monkeys. Figure 7A shows the rate versus level functions for two IC neurons. Although the signal-to-noise ratio was constant across conditions, a higher baseline activity was observed when the noise masker was simultaneously gated with the tone (green circles), compared with when noise background was continuous and was composed of a distribution of levels (gray circles). This result is consistent with findings of Costalupes et al. (1984) in the auditory nerve. Figure 7B summarizes the baseline activity under the two conditions for 84 neurons. The median of the baseline rate distribution shifted toward a lower number of spikes when noise background was similar to that used by Dean et al. (2005) (with levels drawn from a distribution), compared with when gated noise with a steady level was presented. A Wilcoxon sign-rank test confirmed that the baseline activity was significantly higher for the simultaneously gated noise condition (z = 7.8760, P < 0.0001). The relative rate compression was measured for the neurons whose activity reached a saturation level (Fig. 7C). Changes in the noise background caused a compression of the dynamic range when the noise masker was simultaneously gated with the signal compared with the condition where noise background was composed of a distribution of amplitudes. The median rate compression was 0.6566 across the entire set of units, and all units showed rate compression. This result suggests that the range of rates evoked by the simultaneously gated noise was smaller than that evoked by continuous noise. We explored the correlation between the ratio of the dynamic range compression and the frequency used. The slope of the regression model was not significantly different from zero (F = 3.023; P = 0.0871), suggesting that the frequency at which tones are played does not affect adaptation.

Fig. 7.

The neuronal firing rate adapts to the statistical properties of the noise background. A: inferior colliculus (IC) responses of two neurons from two monkeys. For each unit, spikes per tone stimulus (over a temporal window of 50 ms) are shown when the mean noise level was 30 dB sound pressure level (SPL). The responses to tones in continuous noise with levels varying every 50 ms are illustrated as gray symbols along with the responses of the same unit to tones in simultaneously gated noise (green symbols). B: distributions of baseline activity for the gated noise (green histogram) and the noise distribution (gray histogram) conditions. C: histogram shows the rate of the masker-induced dynamic range compression that occurred when the background noise was gated with the tones versus when continuous amplitudes of noise were sampled form a distribution. Tone frequency coincided with the characteristic frequency (CF) of each neuron.

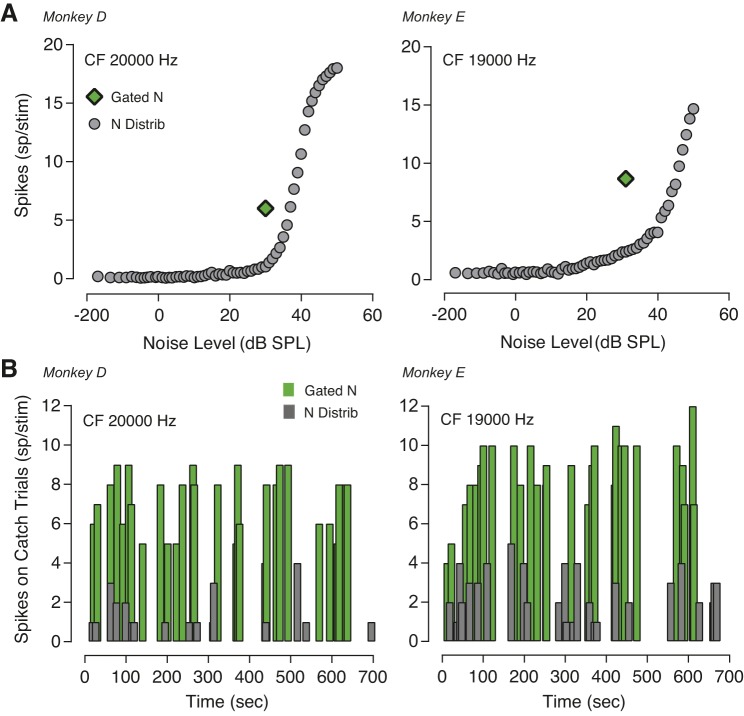

Figure 8 illustrates how nonspecific auditory responses to gated noise contributed to the neuronal dynamic range compression. The top row shows the response magnitude of two neurons (same units shown in Fig. 7A) to 30 dB SPL gated noise and to the noise levels of the distribution in absence of tones. Neuronal adaptation occurred also when only noise was played. Responses of these two IC units to catch trials (only 30 dB SPL spectrum level noise) over time are summarized in Fig. 8B. IC responses to catch trials did not vary as a function of time after the onset of the block.

Fig. 8.

Inferior colliculus (IC) neurons adapt to the characteristic of noise background also in absence of tones. A: neuronal firing rate for catch trials. Response of two IC neurons to noise background when only trials with no tones were played. Neurons show a different pattern of response for the same noise amplitude of 30 dB sound pressure level (SPL) depending on whether the masker was a burst of noise (gated condition, green symbol) or a continuous sequence of noise amplitudes (noise distribution, gray symbols). B: neuronal adaptation to catch trials (only 30 dB SPL noise was presented) did not vary over time.

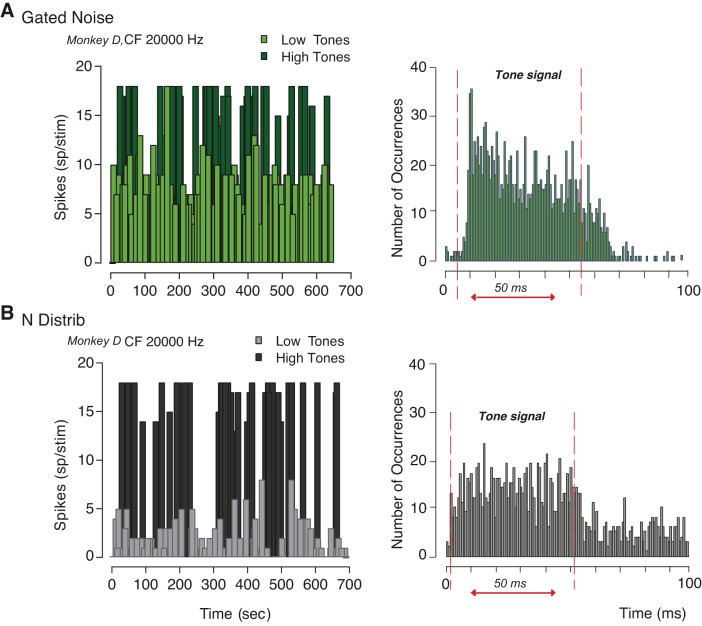

Figure 9 shows neuronal response to tones in noise over time (panels at left) and the peristimulus time histograms (panels at right) for a neuron with a CF of 20,000 Hz (same cell shown in Fig. 7A). IC responses to both low and high sound level tones did not significantly change with time after the onset of the block. The same effect was observed for both simultaneously gated noise (Fig. 9A) and distribution noise (Fig. 9B). However, the peristimulus time histogram (PSTH) for the two conditions showed differences in the time course of the response between the gated and the noise distribution backgrounds. For the simultaneously gated noise condition, we observed strong phasic and tonic components in the PSTH, whereas the responses to the distribution of noise amplitudes are characterized by a diminished phasic component. The Wilcoxon rank-sum test revealed a significant difference between the gated noise and the noise distribution conditions within 0–20 ms poststimulus-onset temporal window (z = 3.5974, P < 0.0001). Although adaptation was observed also for the tonic component, the pattern of response across the two conditions did not significantly differ between 20 and 50 ms after the stimulus onset (z = 1.1174, P < 0.2638). These results are consistent with the effects of a continuous masker in the case of the noise distribution, and the pronounced onset in the simultaneously gated masker case.

Fig. 9.

Example of inferior colliculus (IC) neuronal responses as function of time. A: spiking activity for both low tones and high tones (left) and peristimulus time histogram (right) when the masker was gated with the signal. The threshold for low-high tones corresponded to the tone level at which the rate level function started to increase from its baseline. B: neuronal response of the same neuron to tones (both low and high) within a distribution of noise amplitudes as function of time (left). The peristimulus time histogram is shown (right) in the same format as A. Neuronal adaptation was observed when low tones were played and was largely induced by the phasic component of the stimulus.

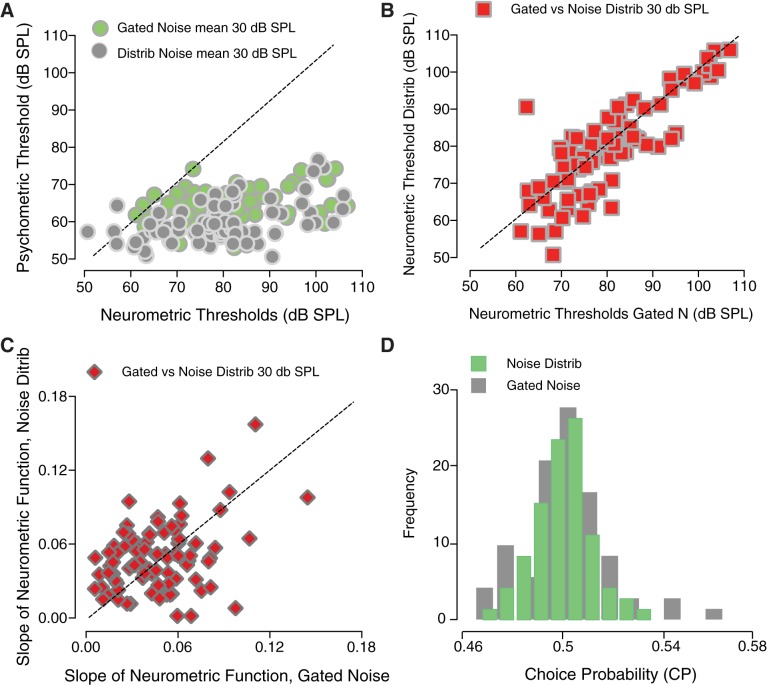

The comparison between psychometric function parameters and neurometric parameters of IC single units is shown in Fig. 10. For each unit, the psychometric threshold obtained during recording is plotted against the individual neurometric threshold (Fig. 10A). This set of data outlines results obtained when tones were embedded in continuous noise with varying amplitudes (gray symbols) versus the condition where bursts of simultaneously gated noise (green symbols). A Wilcoxon sign-rank test showed that neurometric thresholds were significantly higher than psychometric thresholds for both the gated noise (z = −7.7827, P < 0.0001) and the noise distribution (z = −7.7427, P < 0.0001) conditions. This finding suggested that neurometric and psychometric performance did not match when listeners were required to detect 50-ms tones embedded in noise.

Fig. 10.

Relationship between behavioral and neurophysiological responses. A: psychometric thresholds versus neurometric thresholds for distribution noise with a mean of 30 dB sound pressure level (SPL) (gray symbols) and simultaneously gated noise at 30 dB SPL spectrum level (green symbols). B: neurometric thresholds (red squares) obtained in continuous distribution noise versus simultaneously gated noise as a function of noise level. C: neurometric slopes (red diamonds) in continuous distribution noise are plotted against those obtained in gated noise. D: histograms of choice probability (CP). CPs are shown for gated noise (green) and noise distribution (gray) backgrounds. The tone frequency used for behavioral testing always coincided with the characteristic frequency of each neuron.

Consistently with the behavioral results discussed earlier, the Wilcoxon sign-rank test showed that neurometric threshold shifts induced by changes in the noise level (Fig. 10B) were not significantly different depending on whether the masker was a continuous background noise (with varied levels drawn from a distribution) or a burst of noise simultaneously gated with the tone (z = −1.6163, P = 0.1060). The slopes of the neurometric functions (Fig. 10C) did not differ across conditions, suggesting that changes in the mean noise SPL do not cause variations in the neuronal sensitivity (z = 0.8216, P = 0.4113). The histograms of CP (Fig. 10D) show that CP was centered around 0.5, with a majority of the cases (n = 80/84) being not significantly different from 0.5. At the population level, the CP was not significantly different from 0.5, indicating that neuronal responses on correct and incorrect trials were not significantly different (permutation test, P = 0.21) between masking conditions for a 50-ms tone. CP also did not vary as a function of neuronal adaptation.

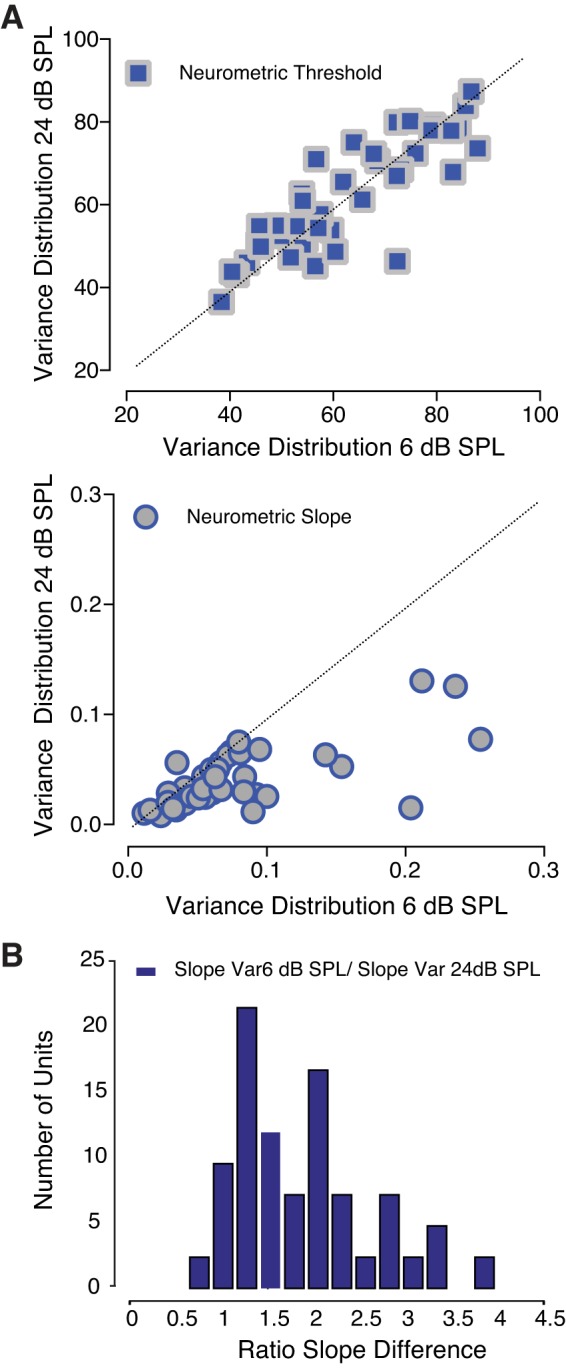

To assess whether or not changes in the variability of the acoustic scene determine variations in the responsiveness of IC neurons, we compared neurometric performance across two different variance conditions (Fig. 11). Thresholds to tones measured for two high-probability region widths (24 and 6 dB) are summarized in Fig. 11A. Figure 11B illustrates the ratio slope difference between the condition with high noise variance (24 dB SPL) and the condition characterized by a relatively low noise variability (6 dB SPL). Neuronal threshold performance did not significantly change depending on the variability characterizing the acoustic stimulus presented (z = −0.2981, P = 0.7656). However, the slope of the neurometric functions did vary as a function of the high-probability region’s width. Slopes were significantly steeper (z = 5.3953, P < 0.0001) when the variability of the noise distribution was relatively low (6 dB SPL). These results are consistent with the behavioral findings presented earlier in this study.

Fig. 11.

Neuronal responses to changes within the variance of the distribution. A: neurometric thresholds were independent of the width of the distribution high-probability region (blue squares). The slope of the neurometric function (gray circles) was significantly higher when the variance of the distribution was relatively low [6 dB sound pressure level (SPL)]. B: histogram shows the ratio of the slope differences between the two conditions.

We also investigated the relationship between the neuronal activity and the RTs. RTs were regressed against spike counts recorded when either the gating condition or the variance of the SPLs was varied (Fig. 12). Figure 12A shows an example of the relationship between RTs and spike counts for one unit. The slopes of the RTs versus spike count appeared to be steeper when noise was gated with the signal (green line) compared with when tones were presented within a distribution of noise amplitudes (gray line). RT slopes and y-intercepts for all the neurons measured in the simultaneously gated masker condition are summarized in Fig. 12B, top and bottom, respectively. The RT slopes observed when noise was gated were significantly steeper than RT slopes with continuous distribution noise (z = 6.1383, P < 0.0001). The median of the RT slopes distributions for gated noise (green histogram) shifted toward higher values, compared with noise distribution (black histogram). Although the effect did not seem to be strong, the y-intercepts were significantly different across the two conditions (z = 3.9817, P = 0.00006). Figure 12C illustrates an example of RTs regressed against spike counts from one neuron when the variance of the high-probability region of the noise distribution was manipulated. The slope of the RT was steeper when the variance of the noise distribution was relatively low (6 dB SPL, represented by a blue line). A Wilcoxon sign-rank test revealed that RT slopes were significantly steeper when the variance of the noise distribution was 6 dB SPL (blue histogram), compared with the condition where the high-probability region width was 24 dB SPL (z = 2.7149, P = 0.0066). However, no significant difference was observed between the two conditions in terms of y-intercepts (z = 0.5064, P = 0.6126).

Fig. 12.

Relationship between reaction times (RTs) and inferior colliculus (IC) neuronal spike counts. A: example of RTs plotted as a function of one unit’s spikes. The RT slope was steeper when the noise masker was gated with the tone. Neuronal adaptation was correlated with RTs. B: summary of RT slopes and intercepts for the entire set of neurons. Both the slope and the intercept were significantly different across the two conditions. C: example of RTs regressed against the spike counts of one unit. The RT slope appeared to be steeper when the variance was low. D: summary of RT slopes and intercepts for the entire set of neurons. Although the effect was weak, RT slopes were significantly higher when the variance of the distribution was 6 dB sound pressure level (SPL). Changes in the variance did not significantly affect the y-intercept.

DISCUSSION

The present study aimed to investigate to what extent sound detectability is affected by neuronal adaptation to noise statistics, and how the perceptual implications of this process relate to the underlying neuronal mechanisms in behaving macaques. We measured the responses of well-isolated single units in the IC of two macaques while these subjects detected sounds embedded in different noise contexts (Fig. 1). The first step taken was to replicate the results obtained in previous studies (e.g., Dean at al. 2005) that showed the adaptive properties of IC neurons to the mean sound level. Our results confirmed that the dynamic range of IC neurons shifts toward the sound levels more likely to be present (mean of the high-probability region) also in awake, behaving macaques (Fig. 2). Although this dynamic range shift has been reported in several studies (Kvale and Schreiner 2004; Dean et al. 2005; Dean et al. 2008; Wen et al. 2009; Watkins and Barbour 2008; Rabinowitz et al. 2013), it is still unknown how adaptation to the properties of the noise background may affect the effectiveness of the noise as a masker. Modeling studies suggested that the adaptation to sound level statistics is purely a characteristic of power law properties in the inner hair cell to auditory nerve fiber synapse, and it is generated mainly by the long-term sound presentation (Zilany and Carney 2010). Our study investigated whether or not neuronal adaptation to noise statistics leads to a noise level and gating invariant response of IC neurons to tones. Behavioral and physiological responses to target signals embedded within noise backgrounds characterized by different temporal characteristics were compared. Do the noise amplitudes surrounding (preceding or following) the noise-masking signal affect neuronal and behavioral response to tones?

Classic studies (e.g., Smith and Zwislocki 1975; Harris and Dallos 1979) have investigated short-term adaptation in the auditory nerve by employing a brief tone preceded by an adapting tone. However, this paradigm does not allow one to test neuronal responses in a more naturalistic environment where sound levels vary rapidly and continuously. Costalupes et al. (1984) showed that the shift in the firing rate of auditory nerve fibers of anesthetized cats did not significantly differ depending on whether the masker was composed of bursts of noise or consisted of continuous noise with a single mean level. Subsequently, Rees and Palmer (1988) reported similar results recording from IC neurons of guinea pigs. Recent work (Rocchi et al. 2017) has shown that psychometric detection thresholds in macaques did not significantly vary depending on whether a 200-ms tone is masked by either simultaneously gated noise or continuous steady-state noise. The present study investigates whether the noise background surrounding target sounds may affect sound detection and the underlying neuronal mechanisms. Given that the mean sound level (as well as the onsets and offsets of different noise maskers) always coincided across the two conditions tested here (gated noise vs. noise distribution), differences in the behavioral and in the neurophysiological responses could be explained in terms of exposure to noise amplitudes surrounding the masked signal. We could hypothesize that if the dynamic range adapted to the entire (overall) range of noise levels, a significant change in the rate level function of single units would be observed to encode the variety of sounds within an acoustic image. On the contrary, if neuronal activity merely adapted to the mean of the sound levels, we would expect IC neurons to respond to tones independently of whether the background noise was gated with the signal or continuous.

Our findings confirmed that tone detection thresholds were raised when noise level was increased (Fig. 3). However, the type of the noise masker used in the detection task did not significantly affect tone thresholds. Detection performance was invariant to the characteristics of the noise (either continuous steady state, gated, or continuous with levels sampled form a probability distribution). Early psychophysical studies (e.g., Leshowitz and Cudahy 1975; Zwicker and Fastl 1972) suggested that gated noise leads to larger masking effects with respect to steady-state noise. However, this discrepancy might be due to differences in the stimuli used (e.g., stimulus duration). Consistently with Rocchi et al. (2017), our results suggest that behavioral detection threshold shifts did not vary as a function of the characteristics of the noise surrounding the signal.

Dahmen et al. (2010) investigated how auditory spatial processes lead to adaptation depending on the variance of the distribution of the input interaural level differences, showing that the variability within the auditory scene affects perceptual and neurophysiological sensitivity. However, the lack of work concerning how changes within the sound variance can affect sound detection leaves this research subject still uncovered. Our results on tone detection are consistent with the findings outlined by Dahmen et al. (2010), showing that the steepness of the psychometric function during detection depends on the width of the high-probability region of the distribution of noise levels (Fig. 4). The change in the sensitivity of the encoding process did not affect detection thresholds.

Previous studies have found that RTs decreased as the tone SPL was increased (e.g., Dylla et al. 2013). To our knowledge, this is the first study where the temporal characteristics of the noise preceding the masked signal have been shown to cause a significant difference in RTs (Fig. 5). The results presented in this paper show that RTs are shorter when the signal was simultaneously gated with the noise, compared with when the noise background was continuous and composed of randomly varying noise levels (Fig. 5). The y-intercepts of the RT regression line was significantly lower for gated noise. One possibility is that the strong contrast between the signal and the background in the gated noise condition led to faster RTs, compared with the noise distribution condition where sustained noise caused a much smaller signal-noise contrast. Moreover, despite the reaction time difference, detection thresholds did not differ between conditions, suggesting that tone detection was not effectively easier when the signal was simultaneously gated with the noise. A similar finding was observed for the stimulus variance. RTs appeared to be shorter (Fig. 6) for a relatively small high-probability region width (6 dB SPL). However, this effect was weaker and it was significant only for one monkey.

The IC represents a crucial location for investigating how the auditory system encodes disparate noise amplitudes, since it is the first site across the ascending pathways where neurons show tuned rate responses to the frequency of sinusoidally amplitude-modulated sounds (e.g., Carney et al. 2015; Krishna and Semple 2000; Langner and Schreiner 1988). The neuronal correlates of sound detection as a function of different noise backgrounds (gated noise vs. noise distribution) are summarized in Fig. 7. Simultaneously gated noise caused significantly higher baseline responses and higher relative rate compression of the rate level function compared with the noise distribution condition. Although the mean sound level was constant across the two conditions tested, the rate responses of IC neurons significantly changed depending on the noise amplitudes surrounding the masked signal. IC neurons adapted to the overall properties of the auditory scene, not only to the mean of the distribution. This adaptation mechanism was observed also for nonspecific auditory responses (Fig. 8). The pattern of response of IC neurons to catch trials (only noise 30 dB SPL was played) largely resembled that described in the presence of a tone target. However, further work will be conducted to elucidate how IC responses to auditory scenes change depending on the presence/absence of a tone target. Here we have also preliminary investigated the temporal properties of the adaptation mechanisms discussed in this study. Our results highlighted that adaptation was largely induced by the phasic component of the stimulus (Fig. 9). The sustained neuronal activation caused by the continuous noise background significantly reduced the strength of IC responses within the signal-onset temporal window. Interestingly, although neuronal response for both low and high sound levels did not vary over time (Fig. 9), adaptation to the background noise amplitudes was observed only when relatively low tone levels were played.

Psychometric thresholds were significantly lower compared with neurometric thresholds (Fig. 10A), suggesting one of two possibilities: 1) the threshold is determined by the most sensitive neurons, the lower envelope principle; or 2) that further signal integration might occur at higher sites of the auditory pathways. This integration might not happen at the level of the primary cortex, given the lack of threshold correspondence and the CP observed for neurons in the primary auditory cortex of monkeys detecting tones in noisy backgrounds (Christison-Lagay et al. 2017). These experiments have been conducted only with 50-ms stimuli. The discrepancy between neurometric and psychometric thresholds could be potentially reduced by using longer stimuli. Although neuronal adaptation to the background noise led to significant changes in the response of IC neurons to tones, neurometric thresholds were not significantly affected by this adaptation process. Both neurometric thresholds (Fig. 10B) and neurometric slopes (Fig. 10C) did not vary depending on the characteristics of the noise presented before and after the masked signal. The relationship between single-neuron activity and sound detection on a trial-by-trial basis can be also summarized in terms of CP (e.g., Britten et al. 1992; Tolhurst et al. 1983). Figure 10D shows that the variability characterizing the behavioral response did not correlate with the variability within IC neuronal activity for the noise backgrounds used. Thus, the CP distributions were both centered around 0.5. The compression observed in the neuronal responses to tones as a function of noise background suggests that IC neurons adapt first to the overall background properties to subsequently preserve the same accuracy in encoding signals masked by different types of noise.

Consistent with previous work (Dahmen et al. 2010), the response of IC neurons was affected by the variance of the high-probability region of the noise distribution (Fig. 11). The slope of IC neurometric functions was observed to be significantly shallower when the variance was increased from 6 to 24 dB SPL, suggesting that neuronal sensitivity might change as a function of the variability within the acoustic scene. However, the neurometric thresholds were invariant to changes within the sound variance. We could hypothesize that the auditory system employs this adaptive computation to maintain the flexibility to encode a relatively wide range of sound levels. Neuronal adaptation to statistics observed in auditory neurons may occur to enable the auditory system to encode noise-invariant sounds. The brain might preserve the representation of salient sounds (which often coincide with the most frequent sounds) regardless of the masking noise. Neuronal mechanisms in the auditory system might resemble the contrast gain control observed across the visual pathways (e.g., Heeger 1992; Shapley and Victor 1978, 1981). The gain of each neuron in the auditory cortex may depend on the sound frequencies contrast within the receptive field of each neuron (Rabinowitz et al. 2012). If this is true, neurometric thresholds should not vary when the statistical properties of the acoustic image change. Such a hypotheses is consistent with the data outlined in this paper. However, further evidence would be required to establish a link between the present results and the noise-invariance hypothesis. RTs were significantly longer when IC neurons adapted to the continuous noise amplitudes (Fig. 12). The slopes of the RT regression lines versus spike counts were significantly steeper when the masker was composed of gated noise (Fig. 12B). A small but significant effect was found also in terms of the y-intercept that appeared to be lower for gated noise. A similar, although weaker, effect was observed when the variance of the distribution was manipulated. The RT slopes were significantly steeper when the variability of the noise amplitudes was relatively small (Fig. 12, C and D). Our results indicate that behavioral detection performance is affected by IC neuronal adaptation to the noise statistics (which occurs when noise is composed of a distribution of noise amplitudes) only in terms of RTs.

The results presented in this study suggest that neuronal adaptation to background sound statistics do not reduce the effectiveness of the masking noise in terms of thresholds. However, the response magnitude of IC neurons is decreased as a consequence of adaptation. The mean of the SPLs within the acoustic environment might not be the dominant factor in the neuronal adaptation process. We have shown that IC neurons adapt to the overall noise amplitude distribution during a detection task when the mean sound level is constant.

GRANTS

The studies described in this report, and the authors, were supported by National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders Grant R01 DC-011092 (to R. Ramachandran).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

F.R. performed experiments; F.R. and R.R. analyzed data; F.R. and R.R. interpreted results of experiments; F.R. prepared figures; F.R. drafted manuscript; F.R. and R.R. edited and revised manuscript; F.R. and R.R. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge Mary Feurtado for help with surgical procedures, Maggie Dylla for help with animal training, and Bruce and Roger Williams for help with construction of equipment.

REFERENCES

- Barlow HB, Levick WR, Yoon M. Responses to single quanta of light in retinal ganglion cells of the cat. Vision Res 11, Suppl 3: 87–101, 1971. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(71)90033-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohlen P, Dylla M, Timms C, Ramachandran R. Detection of modulated tones in modulated noise by non-human primates. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol 15: 801–821, 2014. doi: 10.1007/s10162-014-0467-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bregman AS. Auditory Scene Analysis: The Perceptual Organization of Sound. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Britten KH, Newsome WT, Shadlen MN, Celebrini S, Movshon JA. A relationship between behavioral choice and the visual responses of neurons in macaque MT. Vis Neurosci 13: 87–100, 1996. doi: 10.1017/S095252380000715X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britten KH, Shadlen MN, Newsome WT, Movshon JA. The analysis of visual motion: a comparison of neuronal and psychophysical performance. J Neurosci 12: 4745–4765, 1992. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-12-04745.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carney LH, Li T, McDonough JM. Speech coding in the brain: representation of vowel formants by midbrain neurons tuned to sound fluctuations. eNeuro 2: ENEURO-0004–15, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casseday JH, Fremouw T, Covey E. The inferior colliculus: a hub for the central auditory system. In: Integrative Functions in the Mammalian Auditory Pathway, edited by Oertel D, Fay RR, Popper AN. New York: Springer, 2002, p. 238–318. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4757-3654-0_7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Christison-Lagay KL, Bennur S, Cohen YE. Contribution of spiking activity in the primary auditory cortex to detection in noise. J Neurophysiol 118: 3118–3131, 2017. doi: 10.1152/jn.00521.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costalupes JA, Young ED, Gibson DJ. Effects of continuous noise backgrounds on rate response of auditory nerve fibers in cat. J Neurophysiol 51: 1326–1344, 1984. doi: 10.1152/jn.1984.51.6.1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahmen JC, Keating P, Nodal FR, Schulz AL, King AJ. Adaptation to stimulus statistics in the perception and neural representation of auditory space. Neuron 66: 937–948, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis KA. Evidence of a functionally segregated pathway from dorsal cochlear nucleus to inferior colliculus. J Neurophysiol 87: 1824–1835, 2002. doi: 10.1152/jn.00769.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean I, Harper NS, McAlpine D. Neural population coding of sound level adapts to stimulus statistics. Nat Neurosci 8: 1684–1689, 2005. doi: 10.1038/nn1541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean I, Robinson BL, Harper NS, McAlpine D. Rapid neural adaptation to sound level statistics. J Neurosci 28: 6430–6438, 2008. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0470-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dylla M, Hrnicek A, Rice C, Ramachandran R. Detection of tones and their modification by noise in nonhuman primates. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol 14: 547–560, 2013. doi: 10.1007/s10162-013-0384-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green DM, Swets JA. Signal Detection Theory and Psychophysics. Huntingdon, NY: Krieger, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Harris DM, Dallos P. Forward masking of auditory nerve fiber responses. J Neurophysiol 42: 1083–1107, 1979. doi: 10.1152/jn.1979.42.4.1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heeger DJ. Normalization of cell responses in cat striate cortex. Vis Neurosci 9: 181–197, 1992. doi: 10.1017/S0952523800009640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishna BS, Semple MN. Auditory temporal processing: responses to sinusoidally amplitude-modulated tones in the inferior colliculus. J Neurophysiol 84: 255–273, 2000. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.84.1.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kvale MN, Schreiner CE. Short-term adaptation of auditory receptive fields to dynamic stimuli. J Neurophysiol 91: 604–612, 2004. doi: 10.1152/jn.00484.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langner G, Schreiner CE. Periodicity coding in the inferior colliculus of the cat. I. Neuronal mechanisms. J Neurophysiol 60: 1799–1822, 1988. doi: 10.1152/jn.1988.60.6.1799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leshowitz B, Cudahy E. Masking patterns for continuous and gated sinusoids. J Acoust Soc Am 58: 235–242, 1975. doi: 10.1121/1.380652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macmillan NA, Creelman CD. Detection Theory: A User’s Guide (2nd ed.). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Malmierca MS. The inferior colliculus: a center for convergence of ascending and descending auditory information. Neuroembryology Aging 3: 215–229, 2005. doi: 10.1159/000096799. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Merzenich MM, Reid MD. Representation of the cochlea within the inferior colliculus of the cat. Brain Res 77: 397–415, 1974. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(74)90630-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naka KI, Rushton WA. S-potentials from colour units in the retina of fish (Cyprinidae). J Physiol 185: 536–555, 1966. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1966.sp008001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson PC, Smith ZM, Young ED. Wide-dynamic-range forward suppression in marmoset inferior colliculus neurons is generated centrally and accounts for perceptual masking. J Neurosci 29: 2553–2562, 2009. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5359-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver DL, Huerta MF. Inferior and superior colliculi. In The Mammalian Auditory Pathway: Neuroanatomy, edited by Webster DB, Popper AN, Fay RR,. New York: Springer, 1992, p. 168–221. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4612-4416-5_5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer C, Cheng SY, Seidemann E. Linking neuronal and behavioral performance in a reaction-time visual detection task. J Neurosci 27: 8122–8137, 2007. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1940-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabinowitz NC, Willmore BDB, King AJ, Schnupp JWH. Constructing noise-invariant representations of sound in the auditory pathway. PLoS Biol 11: e1001710, 2013. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabinowitz NC, Willmore BDB, Schnupp JWH, King AJ. Spectrotemporal contrast kernels for neurons in primary auditory cortex. J Neurosci 32: 11271–11284, 2012. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1715-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramachandran R, Davis KA, May BJ. Single-unit responses in the inferior colliculus of decerebrate cats. I. Classification based on frequency response maps. J Neurophysiol 82: 152–163, 1999. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.82.1.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rees A, Palmer AR. Rate-intensity functions and their modification by broadband noise for neurons in the guinea pig inferior colliculus. J Acoust Soc Am 83: 1488–1498, 1988. doi: 10.1121/1.395904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocchi F, Dylla ME, Bohlen PA, Ramachandran R. Spatial and temporal disparity in signals and maskers affects signal detection in non-human primates. Hear Res 344: 1–12, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2016.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapley RM, Victor JD. The effect of contrast on the transfer properties of cat retinal ganglion cells. J Physiol 285: 275–298, 1978. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1978.sp012571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapley RM, Victor JD. How the contrast gain control modifies the frequency responses of cat retinal ganglion cells. J Physiol 318: 161–179, 1981. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1981.sp013856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith RL, Zwislocki JJ. Short-term adaptation and incremental responses of single auditory-nerve fibers. Biol Cybern 17: 169–182, 1975. doi: 10.1007/BF00364166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolhurst DJ, Movshon JA, Dean AF. The statistical reliability of signals in single neurons in cat and monkey visual cortex. Vision Res 23: 775–785, 1983. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(83)90200-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsunada J, Liu AS, Gold JI, Cohen YE. Causal contribution of primate auditory cortex to auditory perceptual decision-making. Nat Neurosci 19: 135–142, 2016. [Erratum in Nat Nerurosci 19: 642, 2016.] doi: 10.1038/nn.4195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins PV, Barbour DL. Specialized neuronal adaptation for preserving input sensitivity. Nat Neurosci 11: 1259–1261, 2008. doi: 10.1038/nn.2201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen B, Wang GI, Dean I, Delgutte B. Dynamic range adaptation to sound level statistics in the auditory nerve. J Neurosci 29: 13797–13808, 2009. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5610-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zilany MS, Carney LH. Power-law dynamics in an auditory-nerve model can account for neural adaptation to sound-level statistics. J Neurosci 30: 10380–10390, 2010. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0647-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zwicker E, Fastl H. On the development of the critical band. J Acoust Soc Am 52, 2B: 699–702, 1972. doi: 10.1121/1.1913161. [DOI] [Google Scholar]