Abstract

In grapevine, the MYB transcription factors play an important role in the flavonoid pathway. Here, a R2R3-MYB transcription factor, VvMYBC2L2, isolated from Vitis vinifera cultivar Yatomi Rose, may be involved in anthocyanin biosynthesis as a transcriptional repressor. VvMYBC2L2 was shown to be a nuclear protein. The gene was shown to be strongly expressed in root, flower and seed tissue, but weakly expressed during the fruit development in grapevine. Overexpressing the VvMYBC2L2 gene in tobacco resulted in a very marked decrease in petal anthocyanin concentration. Expression analysis of flavonoid biosynthesis structural genes revealed that chalcone synthase (CHS), dihydroflavonol 4-reductase (DFR), leucoanthocyanidin reductase (LAR) and UDP glucose flavonoid 3-O-glucosyl transferase (UFGT) were strongly down-regulated in the VvMYBC2L2-overexpressed tobacco. In addition, transcription of the regulatory genes AN1a and AN1b was completely suppressed in transgenic plants. These results suggested that VvMYBC2L2 plays a role as a negative regulator of anthocyanin biosynthesis.

Keywords: grapevine, anthocyanin, MYB transcription factor, repressor, flavonoid pathway

1. Introduction

Flavonoids (including flavonols, anthocyanins and proanthocyanidins) are important plant secondary metabolites, which play multi-biological roles in plants [1,2]. In grapevine, fruit skin color is mainly determined by the content and composition of anthocyanins which also contribute to wine organoleptic properties such as color, taste, bitterness and astringency [3,4]. As a consequence, it is valuable to understand the regulatory mechanism of flavonoid biosynthesis in grapevine.

The MYB family is one of the largest transcription factor families in higher plants, and it plays an important role in the flavonoid pathway. Based on the number of the highly repeat conserved domains (R), MYB proteins can be classified into four major types: 2R-MYB (R2R3-MYB), 3R-MYB (R1R2R3-MYB), 4R-MYB (R1R2R2R1), and MYB- related proteins (or 1R-MYB) [5,6]. Among these MYB proteins, many R2R3-MYB proteins have been shown to be involved in the regulation of proanthocyanin or anthocyanin biosynthesis as positive regulators. In apple, MdMYB1, MdMYB3, MdMYB9, MdMYB10 and MdMYB11 activated the expression of the anthocyanin biosynthesis structural genes [7,8,9,10]. In Arabidopsis, PRODUCTION ANTHOCYANIN PIGMENT1 (PAP1) and PAP2 induced the accumulation of anthocyanin in Arabidopsis and Nicotiana tabacum [11,12]. In grapevine, VlMYBA1-2, VlMYBA1-3, and VlMYBA2, three R2R3-MYB ranscription factors, isolated from Vitis labruscana promoted anthocyanin accumulation by controlling the expression of UFGT in the latest phases of fruit maturation [13]. On the other hand, the transcription factor VvMYB14 was implied in the regulation of the biosynthesis of the resveratrol phytoalexin in grapevine [14,15]. While two other MYBs, VvMYB5a and VvMYB5b, may indirectly activate anthocyanin synthesis through activation of upstream biosynthesis genes in grapevine [16,17]. In addition, other R2R3 MYB transcription factors regulating the flavonol pathway have been identified in grapevine, such as VvMYBPA2, VvMYBF1, and VvMYBPAR [18,19,20]. On the other hand, some R2R3 MYB proteins, acting as the repressors, also participate in the regulation of flavonoid biosynthesis [21,22,23,24]. In Arabidopsis, AtMYBL2 and AtMYB60 inhibit anthocyanin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis or Lactuca sativa plants [21,22]. The strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa) FaMYB1 gene repressed anthocyanin synthesis when it was expressed in tobacco [23], while in Chinese narcissus (Narcissus tazetta), NtMYB2 significantly reduced the accumulation of anthocyanins by activating the transcript levels of anthocyanin biosynthesis structural genes [24].

Repressors of the flavonoid pathway play a key role in moderating the extent and distribution of anthocyanin–derived pigments in plant tissues. However, knowledge about the negative regulation of proanthocyanin or anthocyanin biosynthesis is sparse. As a R2R3-MYB genes with the C2 repressor motif, VvMYBC2L2 was recently studied with respect to its temporal and spatial expression profile in grapevine, but its function in anthocyanin synthesis was not tested [25]. In this paper, we present the transcriptional and functional characterization of the VvMYBC2L2 gene. The bioinformatics analysis, subcellular localization expression pattern, and ectopic expression in tobacco suggest that VvMYBC2L2 functions as a transcriptional repressor of anthocyanin biosynthesis in grapevine.

2. Results

2.1. VvMYBC2L2 Sequence Analysis

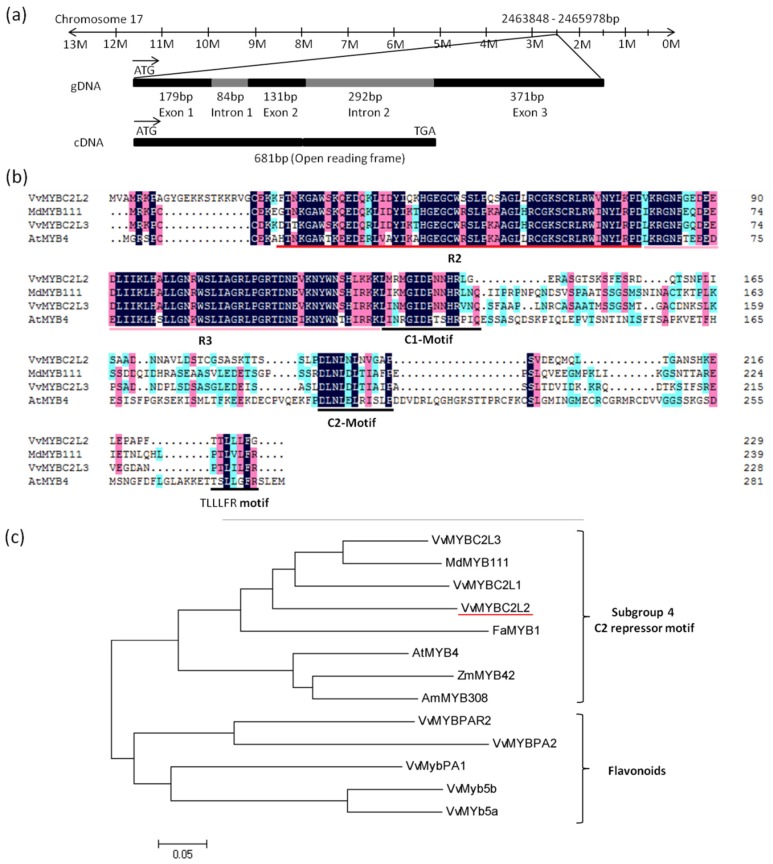

The 681bp coding sequence of VvMYBC2L2 was cloned from cDNA isolated from grapevine ‘Yatomi Rose’ flowers. It encodes a putative protein of 227 amino acids with a predicted protein molecular weight of 25.1 kDa (GenBank accession No. ACX50288). Chromosome location of the VvDRL1 sequence in the V. vinifera cv. Pinot Noir clone P40024 genome indicated that VvMYBC2L2 is mapped on chromosome 17, spanning 1057 bp, including 2 intron (84 bp and 292 bp) and 3 exon (179, 131, and 371 bp) (Figure 1a). Alignment of the VvMYBC2L2 protein with other MYB proteins showed that the VvMYBC2L2 contained a N-terminal R2R3-DNA binding domain of 108 amino acids (Position 21–128) with a motif, [D/E]Lx2[R/K]x3Lx6Lx3R, for interaction with a basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) protein [26] (Figure 1b). Like AtMYB4, VvMYBC2L2 also contained a C-terminal C2 motif (LN[D/E]L[G/S]), which is suggested to be involved in transcriptional repression [5,21]. In addition, a new motif TLLLFR at C-terminal was identified, which was part of the EAR repressor motif (Figure 1b). Due to the divergence in the C-terminal domains, members of R2R3 MYB proteins belong to different branches [27]. Phylogenetic tree indicated that VvMYBC2L2 belongs to subgroup 4 of R2R3 MYB family (Figure 1c). VvMYBC2L2 was closely related to VvMYBC2L1, VvMYBC2L3 and MdMYB111. Moreover, compared with other proteins, VvMYBC2L2 showed high homology with VvMYBC2L1 (57.4% similarity), VvMYBC2L3 (54.3% similarity) in grapevine, MdMYB111 (54.1% similarity) in apple and FaMYB1 (48.9% similarity) in strawberry. There results suggested that VvMYBC2L2 encodes a putative MYB transcriptional repressor in grapevine.

Figure 1.

Features of the predicted VvMYBC2L2 protein. (a) The genomic sequence of VvMYBC2L2. The 1057 bp gDNA of VvMYBC2L2 contains three exons and two introns. (b), Alignment of the deduced amino acid sequence of VvMYBC2L2 with other repressor R2R3-MYB proteins. R2 and R3 are the two repeats of the MYB DNA-binding domain. C1 motif, C2 motif and TLLLFR motif are also boxed at the C-terminus position. (c) Phylogenetic analysis of R2R3-MYB transcription factors. The phylogenetic tree was generated using the neighbor-joining method by the MEGA 5.0 software (Tokyo Metropolitan University, Hachioji, Tokyo, Japan) [28]. GenBank accession numbers are as follows: AtMYB4 (AF062860), AmMYB308 (P81393), FaMYB1 (AF401220), MdMYB111 (HM122615), VvMYBC2L1 (ABW34393), VvMYBC2L2 (ACX50288), VvMYBC2L3 (AIP98385), VvMYB5a (AAS68190), VvMYB5b (AAX51291), VvMYBPA1 (CAJ90831), VvMYBPA2 (ACK56131), VvMYBPAR2 (BAP39802).

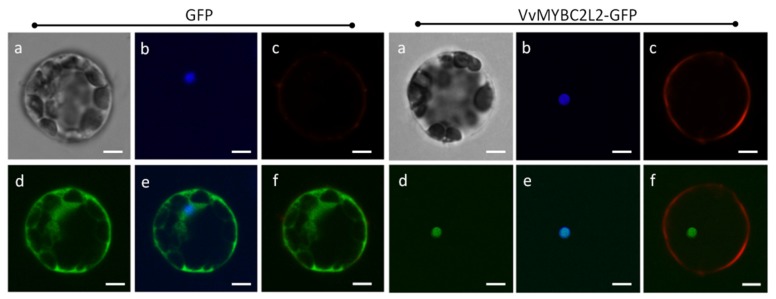

2.2. VvMYBC2L2 Is Localized to the Nucleus

Amino-acid sequence analysis indicated that VvMYBC2L2 contains a nuclear localization signal (NLS), KPDVKRGNFGEDEEDLIIKLHALLGNRWSLI (position 73–104) (http://nls-mapper.iab.keio.ac.jp/cgi-bin/NLS_Mapper_form.cgi). To confirm the subcellular localization of VvMYBC2L2, we created a construct harboring a VvMYBC2L2-GFP fusion gene. Figure 2 shows that the VvMYBC2L2 fused protein was exclusively localized in the nucleus, whereas the control GFP protein was distributed throughout the cytoplasm and cell wall. The results indicated that VvMYBC2L2 is localized to the nucleus.

Figure 2.

Subcellular localization of the VvMYBC2L2 protein. Transient expression of the VvMYBC2L2-GFP fusion protein was performed in A. thaliana mesophyll protoplasts. The fluorescent signal was detected by confocal laser-scanning microscopy. Bright field (a), DAPI (b), Dil (Lipophilic membrance dye) (c), GFP (d), GFP + DAPI merge (e), GFP + Dil merge (f). Bars correspond to 10 μm.

2.3. Transcript Profiles of VvMYBC2L2

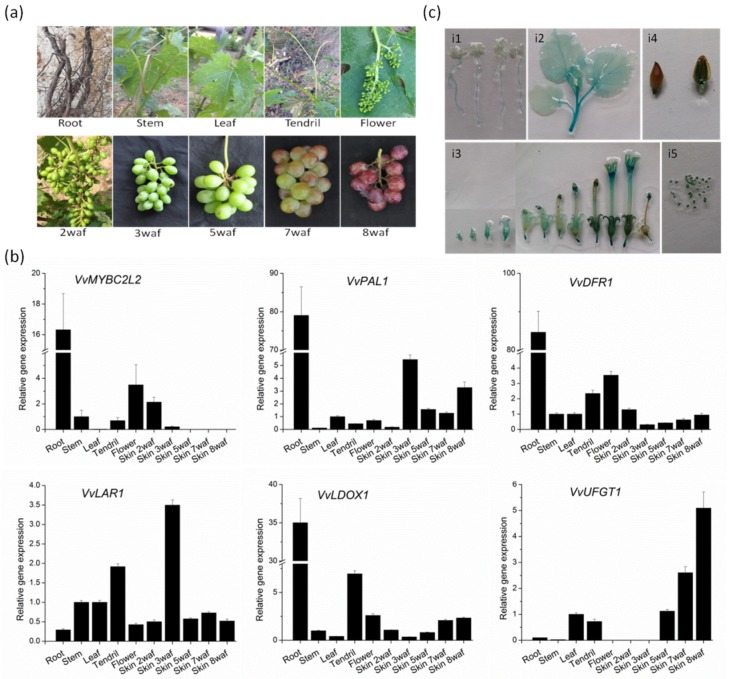

The expression pattern of VvMYBC2L2 in different tissues and organs was carried out in grapevine by RT-qPCR (Figure 3). In grapevine, the expression level of VvMYBC2L2 was highest in the root, similar to the expression levels of VvDRF1, VvPAL1 and VvLDOX1, but higher than that of VvLAR1 and VvUFGT1. In addition, VvMYBC2L2 was expressed at a higher level in the flower than in stems, leaves and tendrils, patterns similar to those of VvDFR1. A difference was that there was a greater transcript abundance in tendrils in VvLAR1, VvDOX1 and VvUFGT1 compared with VvMYBC2L2. In the developing fruit, the transcript abundance of VvMYBC2L2 in skins was highest at 2 weeks after flowering (WAF) and decreased thereafter, similar to the temporal variation in transcript abundance of VvPAL1 and VvLAR1. In contrast to these transcript profiles, the transcript abundances of VvDFR1, VvDOX1 and VvUFGT1 in grape skins were lowest at 2 WAF and increased thereafter, reaching the highest level in 8 WAF.

Figure 3.

Transcript abundance of grapevine genes associated with proanthocyanidin biosynthesis. (a) The different organs (roots, stems, leaves, tendrils and flowers) and berries during berry development of grapevine. Data points during skin development are showed as weeks after flowering (WAF). (b) The expression level of flavonoid-related biosynthetic genes. Transcript levels were measured by quantitative real-time PCR analysis and the expression data were normalized against the expression of VvActin, with the bar representing the mean of the three biological and three technical replicates SD. (c) GUS staining patterns for the VvMYBC2L2 promoter in tobacco plants. i1, 7 days old seedling; i2, leaves and stem at 8 weeks old; i3, flowers at the early, middle and late development period; i4, fruit; i5, seed.

We obtained the 1238-bp VvMYBC2L2 promoter from Yatomi Rose leaves. The cis-regulatory elements were predicted using the PlantCARE database (http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/plantcare/html/). In addition to some typical promoter elements, such as the TATA and CAAT boxes, many cis-acting elements associated with anthocyanin biosynthesis, such as the G-box, P-box, chs-CMA2a and chs-Unit 1 mL, were found in the VvMYBC2L2 promoter. The organ-based expression patterns under the control of VvMYBC2L2 promoter were monitored using GUS reporter gene activity in tobacco. In tobacco seedlings, GUS activities were high in roots and stems, but low in leaves (Figure 3ci1,ci2). In flowers, a high level of GUS expression was found in the calyx at the early stage of flowering, with even greater activity in anthers and stigmas (Figure 3ci3). In fruit, there was a very low level of GUS expression in the seed coat (Figure 3ci4), but high levels in the seed (Figure 3ci5).

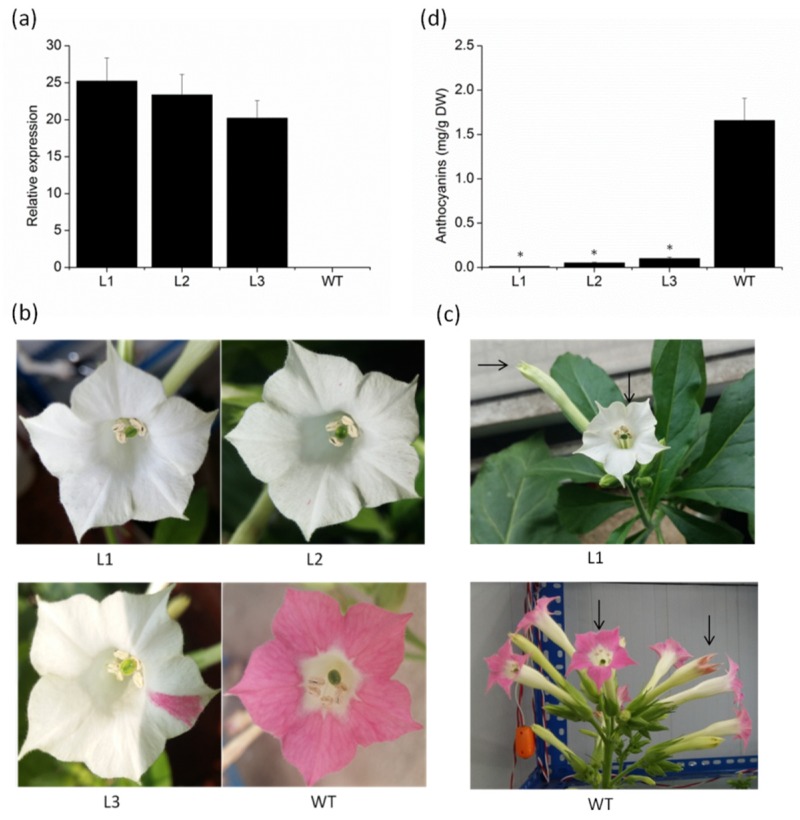

2.4. Overexpression of VvMYBC2L2 in Tobacco Represses the Pigmentation of Petals

To investigate whether the VvMYBC2L2 gene is involved in anthocyanin biosynthesis, we produced transgenic tobacco plants overexpressing VvMYBC2L2. Three T1 lines were chosen by qPCR analysis on the basis of different accumulation levels of VvMYBC2L2 transcripts (Figure 4a). There was no difference in apparent morphology, such as the size of leaves, plant height and fertilization capacity, between the wild-type and transgenic tobacco plants. However, there was a significant difference in flower color. Compared with the dark pink of the wild type plant, there was a prominent loss of petal pigmentation of petal in the VvMYBC2L2-overexpressing plants, ranging from white petals with pink dots or sectors to completely white petals (Figure 4b). To confirm that loss of color in the flower was the result of decreased synthesis of pigments derived from the flavonoid pathway, the total anthocyanin concentration in the flowers was determined. The total anthocyanin accumulation in transgenic tobacco petals was significantly decreased, showing a 94–99% decrease in anthocyanin concentration compared with that in the wild type (Figure 4c). These results suggest that VvMYBC2L2 negatively regulates anthocyanin biosynthesis.

Figure 4.

The phenotypes and anthocyanin concentrations of VvMYBC2L2-overexpressed transgenic tobacco flowers. (a) Expression levels of VvMYBC2L2 transcripts in wild-type (WT) and transgenic plants. L1, L2, L3 represent three transgenic tobacco lines. Bars represent mean ± SD. Transcript levels were measured by RT-PCR analysis and the expression data were normalized against the expression of NtActin. (b) Typical floral phenotypes of WT and transgenic plants. (c) The color of transgenic and WT tobacco flowers at different flower stages. (d) The anthocyanin concentrations in WT and transgenic petals. Anthocyanins were extracted with methanol containing 1% (v/v) hydrochloric acid, and the absorbance of the solution was measured with a UV-Visible Spectrophotometer. Bars represent mean ± SD. Significant differences from the WT were confirmed by ANOVA and Tukey’s test (* p < 0.05).

2.5. VvMYBC2L2-Regulated Flavonoid Biosynthetic Gene Expression in Tobacco Flowers

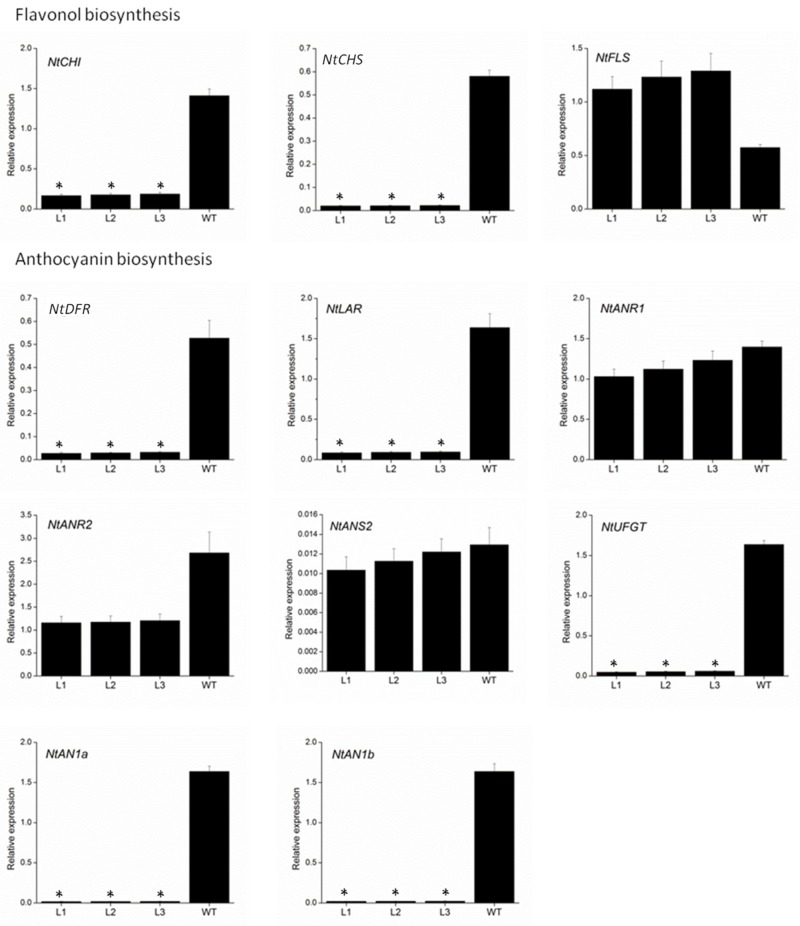

To further elucidate the mechanism underlying the loss of pigmentation in transgenic VvMYBC2L2-overexpressed tobacco flowers, we measured the expression level of genes involved in the flavonoid biosynthetic pathway by using qPCR (Figure 5). The genes selected were chalcone isomerase (NtCHI), NtCHS and flavonol synthase (NtFLS) from flavonol biosynthesis, and NtDFR, NtLAR, anthocyanidin reductase (NtNAR1 and NtANR2), anthocyanidin synthase (NtNAS2) and NtUFGT from anthocyanin biosynthesis. Of these nine structural genes, the expressions of seven, NtCHI, NtCHS, NtDFR, NtLAR, NtANR2, NtANS2 and NtUFGT, were down-regulated in transgenic tobacco petals compared with the wild type. In particular, the abundance of NtCHS, NtDFR, NtLAR and NtUFGT transcripts in transgenic tobacco showed remarkable reductions, namely 96.2–96.4%, 93.9–94.8%, 94.1–94.8% and 96.4–97.1% decreases, respectively, compared with the wild type. The transcript abundances of NtANR1 and NtNAS2 were weakly suppressed in the transgenic plants, with 11.8–26.3% and 5.6–20% reductions, respectively, compared with the wild type. On the other hand, overexpressing VvMYBC2L2 in tobacco plants enhanced the expression of NtFLS. In addition, as the regulatory genes, the transcript abundances of NtAN1a and NtAN1b were almost completely suppressed in the transgenic plants, with 98.8–98.9% and 98.6–98.8% reductions, respectively, compared with the wild type.

Figure 5.

Quantitative analyses of transcript levels of flavonoid-related biosynthetic and regulatory genes in petals of wild-type and transgenic tobacco. The expression data were normalized against the expression of NtActin. Bars represent mean ± SD. Significant difference from the WT was confirmed by ANOVA and Tukey’s test (* p < 0.05).

Taken together, these results indicated that VvMYBC2L2 functions as a repressor of anthocyanin biosynthesis.

3. Discussion

In grapevine, 108 R2R3-MYB transcription factors have been identified from the genome of the PN40024 genotype of Vitis vinifera cv. Pinot Noir, which play an important role in the flavonoid pathway [29]. In this work, we reported the isolation and characterization of a R2R3-MYB transcription factor, named VvMYBC2L2. VvMYBC2L2 belongs to subgroup 4 of the R2R3-MYB family (Figure 1b). The members of this group, such as AtMYB4, MdMYB111 and VvMYBC2L3, all contain the C2 motif, which functions in transcriptional repression [30]. There was also a putative TLLLFR-type repressor motif at the C-terminnus of VvMYBC2L2, which was also found in the flavonoid repressor AtMYBL2 [21]. Compared with other R2R3 MYB proteins, VvMYBC2L2 has strong similarities with VvMYBC2L3, MdMYB111 and FaMYB1 which negatively regulate the flavonoid pathway [23,25,31]. These results suggested that VvMYBC2L2 may play a role as an active transcriptional repressor of flavonoid biosynthesis in grapevine.

In grape vine ’Corvina’, MYBC2L2 showed very low expression levels in almost all organs including the berry and seed [25]. However, VvMYBC2L2 showed unique spatiotemporal specificity among anthocyanin regulators in grapevine ’Yatomi Rose’. Abundant transcripts were detected in roots and flowers, with particularly high expression in berry skins, reaching maximum levels at the pre-veraison stages (2 WAF) and decreasing thereafter during berry development. The same expression profile was shown by VvLAR1 and VvPAL1, implying that VvMYBC2L2 was involved in the flavonoid pathway. Most of the other structural genes of the flavonoid biosynthesis pathway, such as VvDFR1 and VvDLOX1, showed a different trendwith the transcript abundance being higher at flowering and during early berry development, then declining after flowering, and increasing again at véraison (Figure 3). In particular, VvUFGT1 showed an expression pattern opposite to that of VvMYBC2L2, highly induced in the skin after veraison. UFGT is a key enzyme, catalyzing the final step of the anthocyanin biosynthesis pathway [32]. These findings suggested that VvMYBC2L2 may have a role as a negative regulator of anthocyanin synthesis in grapevine.

By means of heterologous expression in tobacco, we confirmed the regulatory function of VvMYBC2L2 in anthocyanin synthesis. Constitutive expression of VvMYBC2L2 repressed the accumulation of anthocyanins in transgenic tobacco flowers, but did not change the phenotype during vegetative development. VvMYBC2L1 and VvMYB4-like transgenic tobacco plants also showed the loss of pigments in the flower petals [33]. Similar results were obtained in genes from other species, including FaMYB1 [23], AtMYB60 [34], GtMYBIR1, and GtMYBIR2 [35]. These results support the role of VvMYBC2L2 as a flavonoid repressor.

Expression analyses also confirmed that overexpression of VvMTBC2L2 causes drastic down-regulation of flavonoid-related genes, with NtCHS, NtDFR, NtLAR and NtUFGT transcripts all being notably suppressed. CHS is the first key enzyme in flavonoid biosynthesis, catalyzing condensation of p-coumaroyl-coenzyme A and malonyl-CoA to form chalcone. In dahlias, suppression of CHS resulted in white flowers [36], while, in Petunia hybrid, constitutive expression of an ‘anti-sense’ CHS gene inhibits flower pigmentation [37]. DFR participates in anthocyanin biosynthesis by catalyzing the conversion of dihydroflavonol to leucoanthocyanidins. Constitutive expression of the Vitis bellula gene VbDFR increased anthocyanin accumulation in tobacco [38], while, over-expression of the grapevine transcription factor genes carrying the C2-motif repressor, VvMYBC2L1 and VvMYBC2L3, significantly decreased the transcript level of DFR in Petunia hybrida [25]. UFGT is involved in glycosylation of anthocyanidins to form anthocyanins, and was specific induced in red cultivars of V. vinifera but not white cultivars. In Chinese narcissus, NtMYB2 negatively regulated anthocyanin biosynthesis by down-regulating expression of the flavonoid genes, particularly UFGT [24]. Analysis indicated that suppression of specific flavonoid biosynthetic genes could repress the accumulation of anthocyanins. The decrease in floral pigmentation when VvMYBC2L2 was expressed in tobacco might be achieved by regulating these flavonoid biosynthetic genes. Moreover, the transcript levels of the regulatory genes, NtAN1a and NtAN1b-in VvMYBC2L2-overexpressed transgenic tobacco plants were also sharply reduced. NtAN1a and NtAN1b, two members of the basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) transcription factor family, positively regulate the anthocyanin pathway in tobacco flowers [39]. It is reported that combinatorial interactions between MYB and bHLH transcription factors within the MBW (MYB-bHLH-WD40) complex are crucial for the regulation of the flavonoid pathway. VvMYBC2L2 possessed the bHLH-interacting signature in the R3 repeat (Figure 1b), so we speculated that VvMYBC2L2 might negatively regulate the flavonoid pathway through the participation of the MBW complex.

In summary, we confirmed that the VvMYBC2L2 gene plays a role as a negative regulator in anthocyanin biosynthesis in grapevine. To date, negative regulation of anthocyanin biosynthesis in plants is largely unknown, our findings will provide a new insight into such regulatory mechanisms.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Material and Growth Conditions

Vitis vinifera cv. Yatomi Rose (Red table grape cultivar) was grown in the grape germplasm resource orchard of Shandong Institute of Pomology, Taian, Shandong, China. Samples collected from roots, stems and leaves were taken from grapevine plants (Vitis vinifera cv. Yatomi Rose) and samples collected from flowers were collected 2 days before flowering (Pre-capfall pollinization period). Samples taken from fruits corresponded to the fruits skin removed from fruits at different developmental stages: 2, 3, 5, 7 and 8 weeks after flowering (WAF). Three biological replicates were collected from three different plants. All collected samples were frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C. Tobacco plants (Nicotiana tabacum cv. NC89 and Nicotian benthamiana) were grown in vitro on MS medium under a 16/18 h photoperiod at 25 °C.

4.2. Isolation of the VvMYBC2L2 Promoter Sequence

DNA from the grapevine leaves was extracted using the CTAB method. Based on the grapevine genome sequence, we designed the primers with the forward primer 5′-TACCACCGGAAAAGTACAATACCATCT-3′ and reverse primer 5′-GGCGATAGAGAAAGACCGTAGAG AG-3′ (Table S1). Promoter amplification was performed using the PrimerSTAR GXL DNA Polymerase (Takara, Dalian, China) with the PCR reactions: 2min at 94 °C, 30 cycles of 30 s at 94 °C, 30 s at 56 °C, 1.5 min at 72 °C, then 10 min at 72 °C. The PCR fragment was cloned into pMD18T vector (Takara) and the colonies were sequenced by Sangon Biotechnology Company (Shanghai, China).

4.3. RNA Isolation and Expression Analysis

Total RNA from the grapevine was extracted using the method described by Reid et al. [40]. The integrity of extracted RNA was checked on 1% agarose gels to ensure that the 28S and 18S were clear without tailing and that the 28S:18S ratio was 2:1. The RNA concentration was determined using an Ultramicro Spectrophotometer (P-330-31, Implen, Munich, Germany). The cDNA first strand was synthesized from 1 µg total RNA using the PrimerScriptTM II 1st Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Takara). Quantitative RT-PCR was run on IQ5 real time PCR cycler (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA) with SYBR® Green I dye. Reactions were the following thermal profile: 3 min at 94 °C, 40 cycles of 5 s at 94 °C, 30 s at 58 °C. The relative mRNA rations were calculated as 2−ΔΔCT [41]. The transcript levels of target genes were normalized against VvActin for the grape samples and NtActin for Nicotiana samples [40,42]. The data are presented as the mean value of three biological replicates.

4.4. Subcellular Location of the VvMYBC2L2

The coding region of VvMYBC2L2 without the termination codon was amplified using the PrimerSTAR GXL DNA Polymerase (Takara, Shiga, Japan) with the forward primer 5′-GGTCTAGAATGG TTGCAATGAGGAAGCCTGCAG-3′ and reverse primer 5′-GGGGTACCTCCAAAAAGAAGTAGA GTTGTAAAG-3′. Reaction was the following thermal profile: 2 min at 94 °C, 30 cycles of 30 s at 94 °C, 30 s at 56 °C, 1 min at 72 °C, then 10 min at 72 °C. The resulting fragments were digested with XbaI and KpnI and then cloned into the vector pBI221-GFP to generate pBI221-VvMYBC2L2-GFP constructs. The polyethylene glycol-mediated transfection of A. thaliana mesophyll protoplasts was conducted according to previously described protocols [43]. The location of the fusion protein was observed 16 h after transformation using a confocal microscope (LSM510; Carl Zeiss Thornwood, New York, NY, USA).

4.5. Construct Assembly and Plant Transformation

The coding sequence of VvMYBC2L2 was amplified by PCR. The resulting fragment were digested by Sall and Sacl and sub-cloned into vector pRI101-AN. The 1229-bp promoter of VvMYBC2L2 was inserted into the vector pCAMIA1391z to generate the construct VvMYBC2L2pro:GUS. These constructs were transferred into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101 by electrofusion. The transformation of the leaf discs and the regeneration of the transgenic tobacco plants were carried out according to the protocol described by Horsch et al. [44]. Transgenic plants were selected on MS medium with kanamycin (100 mg·L−1) or hygromycin (25 mg·L−1) added. T1 generation tobacco plants were used for further analysis.

4.6. Determination of Total Anthocyanin Content Concentration

The total anthocyanin concentration in tobacco flowers was determined as previously described [45]. The fresh flower were ground in liquid nitrogen and extracted with methanol (containing 1% HCl). The absorbance of supernatants was determined at 530 nm and 657 nm using a UV-Visible Spectrophotometer (UV2600, Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). The concentration of anthocyanin was determined using the following equation: (A530 − 0.25 × A657) × FW−1. All samples were measured in triplicate and as three independent biological replicates.

4.7. Histochemical GUS Analysis

Histochemical GUS analysis was performed according to the method of Jefferson et al. with minor modifications [46]. The samples were put into acetone (90%) for 20–30 min at 4 °C, and rinsed in wash buffer for 30 min at 4 °C, and then immersed in GUS staining solution and a vacuum applied until the samples sunk. After incubation at 37 °C overnight, the samples were washed with 70% ethanol until the chlorophyll had faded completely. The GUS staining solution (100 mM NaH2PO4, 100 mM Na2HPO4, 10 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM K3Fe(CN)3, 0.5 mM K4Fe(CN)4, Triton-X 0.1%, X-GLuc 0.5mg·L−1, pH 7.0) was stored at −20 °C.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online, Table S1: Sequence of the primers in the experiment for qPCR.

Author Contributions

B.L. and X.C. designed the study. Z.Z. performed the experiments and manuscript preparation. G.L. carried out the expression of the flavonoid biosynthesis genes. L.L., Q.Z. and Z.H. participated in the transformation with the VvMYBC2L2 gene and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Shandong Major Science and Technology Project (Grant No. 2016ZDJS10A01), Shandong Forestry Science and Technology Innovation Project (Grant No. LYCX03-2018-13), China’s Post-doctoral Science Foundation (Grant No. 2016M592231) and Henan Natural Science Foundation (Grant No. 182300410031).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Sample Availability: Not available.

References

- 1.Winkel-Shirley B. Flavonoid biosynthesis. A colorful model for genetics, biochemistry, cell biology, and biotechnology. Plant Physiol. 2001;126:485–493. doi: 10.1104/pp.126.2.485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nabavi S., Samec D., Tomczyk M., Milella L., Russo D., Habtemariam S., Suntar I., Rastrelli L., Daglia M., Xiao J., et al. Flavonoid biosynthetic pathways in plants: versatile targets for metabolic engineering. Biotechnol. Adv. 2019:37. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2018.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Soares S., Brandao E., Mateus N., de Freitas V. Sensorial properties of red wine polyphenols: astringency and bitterness. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017;57:937–948. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2014.946468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li S.Y., Duan C.Q. Astringency, bitterness and color changes in dry red wines before and during oak barrel aging: An updated phenolic perspective review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2018:1–28. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2018.1431762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dubos C., Stracke R., Grotewold E., Weisshaar B., Martin C., Lepiniec L. MYB transcription factors in Arabidopsis. Trends Plant Sci. 2010;15:573–581. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2010.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martin C., Paz-Ares J. MYB transcription factors in plants. Trends Genet. 1997;13:67–73. doi: 10.1016/S0168-9525(96)10049-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.An X.H., Tian Y., Chen K.Q., Liu X.J., Liu D.D., Xie X.B., Cheng C.G., Cong P.H., Hao Y.J. MdMYB9 and MdMYB11 are involved in the regulation of the JA-induced biosynthesis of anthocyanin and proanthocyanidin in apples. Plant Cell Physiol. 2015;56:650–662. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcu205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Espley R.V., Hellens R.P., Putterill J., Stevenson D.E., Kutty-Amma S., Allan A.C. Red colouration in apple fruit is due to the activity of the MYB transcription factor, MdMYB10. Plant J. 2007;49:414–427. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02964.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hu D.G., Sun C.H., Ma Q.J., You C.X., Cheng L., Hao Y.J. MdMYB1 regulates anthocyanin and malate accumulation by directly facilitating their transport into vacuoles in apples. Plant Physiol. 2016;170:1315–1330. doi: 10.1104/pp.15.01333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vimolmangkang S., Han Y., Wei G., Korban S.S. An apple MYB transcription factor, MdMYB3, is involved in regulation of anthocyanin biosynthesis and flower development. BMC Plant Biol. 2013;13:176. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-13-176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gonzalez A., Zhao M., Leavitt J.M., Lloyd A.M. Regulation of the anthocyanin biosynthetic pathway by the TTG1/bHLH/Myb transcriptional complex in Arabidopsis seedlings. Plant. J. 2008;53:814–827. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03373.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Teng S., Keurentjes J., Bentsink L., Koornneef M., Smeekens S. Sucrose-specific induction of anthocyanin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis requires the MYB75/PAP1 gene. Plant Physiol. 2005;139:1840–1852. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.066688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cutanda-Perez M.C., Ageorges A., Gomez C., Vialet S., Terrier N., Romieu C., Torregrosa L. Ectopic expression of VlmybA1 in grapevine activates a narrow set of genes involved in anthocyanin synthesis and transport. Plant Mol. Biol. 2009;69:633–648. doi: 10.1007/s11103-008-9446-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jeandet P., Clément C., Cordelier S. Regulation of resveratrol biosynthesis in grapevine: new approaches for disease resistance? J. Exp. Bot. 2019:70. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ery446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jiang J., Xi H., Dai Z., Lecourieux F., Yuan L., Liu X., Patra B., Wei Y., Li S., Wang L. VvWRKY8 negatively regulates VvSTS through direct interaction with VvMYB14 to balance resveratrol biosynthesis in grapevine. J. Exp. Bot. 2019:70. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ery401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deluc L., Barrieu F., Marchive C., Lauvergeat V., Decendit A., Richard T., Carde J.P., Merillon J.M., Hamdi S. Characterization of a grapevine R2R3-MYB transcription factor that regulates the phenylpropanoid pathway. Plant Physiol. 2006;140:499–511. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.067231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deluc L., Bogs J., Walker A.R., Ferrier T., Decendit A., Merillon J.M., Robinson S.P., Barrieu F. The transcription factor VvMYB5b contributes to the regulation of anthocyanin and proanthocyanidin biosynthesis in developing grape berries. Plant Physiol. 2008;147:2041–2053. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.118919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Terrier N., Torregrosa L., Ageorges A., Vialet S., Verries C., Cheynier V., Romieu C. Ectopic expression of VvMybPA2 promotes proanthocyanidin biosynthesis in grapevine and suggests additional targets in the pathway. Plant Physiol. 2009;149:1028–1041. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.131862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Czemmel S., Stracke R., Weisshaar B., Cordon N., Harris N.N., Walker A.R., Robinson S.P., Bogs J. The grapevine R2R3-MYB transcription factor VvMYBF1 regulates flavonol synthesis in developing grape berries. Plant Physiol. 2009;151:1513–1530. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.142059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koyama K., Numata M., Nakajima I., Goto-Yamamoto N., Matsumura H., Tanaka N. Functional characterization of a new grapevine MYB transcription factor and regulation of proanthocyanidin biosynthesis in grapes. J. Exp. Bot. 2014;65:4433–4449. doi: 10.1093/jxb/eru213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matsui K., Umemura Y., Ohme-Takagi M. AtMYBL2, a protein with a single MYB domain, acts as a negative regulator of anthocyanin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2008;55:954–967. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03565.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Galbiati M., Matus J.T., Francia P., Rusconi F., Canon P., Medina C., Conti L., Cominelli E., Tonelli C., Arce-Johnson P. The grapevine guard cell-related VvMYB60 transcription factor is involved in the regulation of stomatal activity and is differentially expressed in response to ABA and osmotic stress. BMC Plan. Biol. 2011;11 doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-11-142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aharoni A., De Vos C.H., Wein M., Sun Z., Greco R., Kroon A., Mol J.N., O’Connell A.P. The strawberry FaMYB1 transcription factor suppresses anthocyanin and flavonol accumulation in transgenic tobacco. Plant J. 2001;28:319–332. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2001.01154.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Anwar M., Wang G., Wu J., Waheed S., Allan A.C., Zeng L. Ectopic overexpression of a novel R2R3-MYB, NtMYB2 from Chinese narcissus represses anthocyanin biosynthesis in tobacco. Molecules. 2018;23 doi: 10.3390/molecules23040781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cavallini E., Matus J.T., Finezzo L., Zenoni S., Loyola R., Guzzo F., Schlechter R., Ageorges A., Arce-Johnson P., Tornielli G.B. The phenylpropanoid pathway is controlled at different branches by a set of R2R3-MYB C2 repressors in grapevine. Plant Physiol. 2015;167:1448–1470. doi: 10.1104/pp.114.256172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zimmermann I.M., Heim M.A., Weisshaar B., Uhrig J.F. Comprehensive identification of Arabidopsis thaliana MYB transcription factors interacting with R/B-like BHLH proteins. Plant J. 2004;40:22–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02183.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rabinowicz P.D., Braun E.L., Wolfe A.D., Bowen B., Grotewold E. Maize R2R3 Myb genes: sequence analysis reveals amplification in the higher plants. Genetics. 1999;153:427–444. doi: 10.1093/genetics/153.1.427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tamura K., Peterson D., Peterson N., Stecher G., Nei M., Kumar S. MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2011;28:2731–2739. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Czemmel S., Heppel S.C., Bogs J. R2R3 MYB transcription factors: key regulators of the flavonoid biosynthetic pathway in grapevine. Protoplasma. 2012;249:109–118. doi: 10.1007/s00709-012-0380-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kagale S., Links M.G., Rozwadowski K. Genome-wide analysis of ethylene-responsive element binding factor-associated amphiphilic repression motif-containing transcriptional regulators in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2010;152:1109–1134. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.151704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen K.Q., Zhao X.Y., An X.H., Tian Y., Liu D.D., You C.X., Hao Y.J. MdHIR proteins repress anthocyanin accumulation by interacting with the MdJAZ2 protein to inhibit its degradation in apples. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:44484. doi: 10.1038/srep44484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vogt T. Phenylpropanoid biosynthesis. Mol. Plant. 2010;3:2–20. doi: 10.1093/mp/ssp106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Perez-Diaz J.R., Perez-Diaz J., Madrid-Espinoza J., Gonzalez-Villanueva E., Moreno Y., Ruiz-Lara S. New member of the R2R3-MYB transcription factors family in grapevine suppresses the anthocyanin accumulation in the flowers of transgenic tobacco. Plant. Mol. Biol. 2016;90:63–76. doi: 10.1007/s11103-015-0394-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Park J.S., Kim J.B., Cho K.J., Cheon C.I., Sung M.K., Choung M.G., Roh K.H. Arabidopsis R2R3-MYB transcription factor AtMYB60 functions as a transcriptional repressor of anthocyanin biosynthesis in lettuce (Lactuca sativa) Plant Cell Rep. 2008;27:985–994. doi: 10.1007/s00299-008-0521-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nakatsuka T., Yamada E., Saito M., Fujita K., Nishihara M. Heterologous expression of gentian MYB1R transcription factors suppresses anthocyanin pigmentation in tobacco flowers. Plant. cell rep. 2013;32:1925–1937. doi: 10.1007/s00299-013-1504-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ohno S., Hosokawa M., Kojima M., Kitamura Y., Hoshino A., Tatsuzawa F., Doi M., Yazawa S. Simultaneous post-transcriptional gene silencing of two different chalcone synthase genes resulting in pure white flowers in the octoploid dahlia. Planta. 2011;234:945–958. doi: 10.1007/s00425-011-1456-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Van der Krol A.R., Lenting P.E., Veenstra J., van der Meer I.M., Koes R.E., Gerats A.G.M., Mol J.N.M., Stuitje A.R. An anti-sense chalcone synthase gene in transgenic plants inhibits flower pigmentation. Nature. 1988:866–869. doi: 10.1038/333866a0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhu Y., Peng Q., Li K., Xie D.Y. Molecular cloning and functional characterization of a dihydroflavonol 4-Reductase from Vitis bellula. Molecules. 2018;23:861. doi: 10.3390/molecules23040861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bai Y., Pattanaik S., Patra B., Werkman J.R., Xie C.H., Yuan L. Flavonoid-related basic helix-loop-helix regulators, NtAn1a and NtAn1b, of tobacco have originated from two ancestors and are functionally active. Planta. 2011;234:363–375. doi: 10.1007/s00425-011-1407-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reid K.E., Olsson N., Schlosser J., Peng F., Lund S.T. An optimized grapevine RNA isolation procedure and statistical determination of reference genes for real-time RT-PCR during berry development. BMC Plant Biol. 2006;6:27. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-6-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Livak K.J., Schmittgen T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gutha L.R., Casassa L.F., Harbertson J.F., Naidu R.A. Modulation of flavonoid biosynthetic pathway genes and anthocyanins due to virus infection in grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.) leaves. BMC Plant Biol. 2010;10 doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-10-187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yoo S.D., Cho Y.H., Sheen J. Arabidopsis mesophyll protoplasts: a versatile cell system for transient gene expression analysis. Nat. Protoc. 2007;2:1565–1572. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Horsch R.B., Fry J.E., Hoffmann N.L., Eichholtz D., Rogers S.G., Fraley R.T. A simple and general method for transferring genes into plants. Science. 1985;227:1229–1231. doi: 10.1126/science.227.4691.1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Huang W., Khaldun A.B., Chen J., Zhang C., Lv H., Yuan L., Wang Y. A R2R3-MYB transcription factor regulates the flavonol biosynthetic pathway in a traditional chinese medicinal plant, pimedium sagittatum. Front. Plant Sci. 2016;7:1089. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.01089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jefferson R.A., Kavanagh T.A., Bevan M.W. GUS fusions: beta-glucuronidase as a sensitive and versatile gene fusion marker in higher plants. EMBO J. 1987;6:3901–3907. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb02730.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.