Abstract

Nitrated lipids have been detected in vitro and in vivo, usually associated with a protective effect. While nitrated fatty acids have been widely studied, few studies reported the nitration and nitroxidation of the phospholipid classes phosphatidylcholine, and phosphatidylethanolamine. However, no information regarding nitrated and nitroxidized phosphatidylserine can be found in the literature. This work aims to identify and characterize the nitrated and nitroxidized derivatives of 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-3-glycero-phosphoserine (POPS), obtained after incubation with nitronium tetrafluoroborate, by liquid chromatography (LC) coupled to mass spectrometry (MS) and tandem MS (MS/MS). Several nitrated and nitroxidized products were identified, namely, nitro, nitroso, nitronitroso, and dinitro derivatives, as well as some nitroxidized species such as nitrosohydroxy, nitrohydroxy, and nitrohydroperoxy. The fragmentation pathways identified were structure-dependent and included the loss of HNO and HNO2 for nitroso and nitro derivatives, respectively. Combined losses of PS polar head group plus HNO or HNO2 and carboxylate anions of modified fatty acyl chain were also observed. The nitrated POPS also showed antiradical potential, demonstrated by the ability to scavenge the ABTS●+ and DPPH● radicals. Overall, this in vitro model of nitration based on LC-MS/MS provided additional insights into the nitrated and nitroxidized derivatives of PS and their fragmentation fingerprinting. This information is a valuable tool for targeted analysis of these modified PS in complex biological samples, to further explore the new clues on the antioxidant potential of nitrated POPS.

Keywords: lipidomic, nitration, nitroxidative stress, phosphatidylserine, tandem mass spectrometry, LC-MS

1. Introduction

Phosphatidylserine (PS) is a key phospholipid of the inner leaflet of the cell membranes, and it also participates in several signaling and biological processes, namely targeting and function of intracellular signaling proteins [1,2,3]. However, PS and also oxidized PS can be translocated to the outer leaflet and be exposed at the cell surface, in early stages of apoptosis, which is a well-known signaling of apoptotic cells [3,4,5]. Identification of oxidized PS in biological samples, as well as its biological role, has been the outcome of several studies that used mass spectrometry-based approaches, allowing to detected oxygenated PSs both in vitro and in vivo [6,7,8,9]. Depending on the oxidation product and the biological context, PS oxidation products are reported to have both anti and/or pro-inflammatory actions [10,11]. However, in physiological and pathological conditions, reactive nitrogen species are also responsible for the nitration and nitroxidation of biomolecules, including lipids. Several studies identified and quantified nitrated fatty acids in biological systems, based on advanced mass spectrometry strategies, allowing to pinpoint nitrated fatty acids as important signaling molecules in health and disease [12,13,14]. Phospholipid nitration has also been reported in few in vitro mimetic models of nitroxidative stress conditions using phospholipid standards of phosphatidylcholines (PCs) and phosphatidylethanolamines (PEs) [15,16]. Nitrated and nitroxidized derivatives of PCs and PEs were also identified in vivo, namely in cardiac mitochondria isolated from the heart of an animal model of type 1 diabetes mellitus [15], and in vitro, in cardiomyoblast H9c2 cells under starvation conditions [16]. Moreover, recently, it was reported the potential of nitrated 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine as antioxidant and anti-inflammatory agent [17]. In spite of the work done for PC and PE nitrated derivatives, there is a lack of knowledge regarding the identification of nitrated and nitroxidized derivatives of PS by mass spectrometry. This needs to be overcome since the identification of specific fragmentation pathways, and reporter ion of these modified PS, is essential to detect these modified lipids in biological samples and to screen their putative biological role. Driven by the lack of knowledge on phospholipid nitration, particularly on PS nitrated and nitroxidized products, in this study, 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoserine (POPS, PS16:0/18:1) was incubated with nitronium tetrafluoroborate (NO2BF4), and the new nitrated and nitroxidized products were studied by LC-MS approaches. Nitronium tetrafluoroborate is a salt of nitronium ion (NO2+) that is a well-known mimetic nitrating agent used in previous studies on phospholipid [15], and fatty acid nitration [12]. POPS was selected because it is one of the abundant PS molecular species detected in some cell types as keratinocytes [18], and tissues as intestinal and lung [19]. Additionally, oleic acid seems to be one of the targets of nitration [20] and nitro-oleic acid is considered a bioactive lipid with anti-inflammatory [21,22], and antioxidant properties [23]. Identification of nitrated/nitroxidized PS species was performed by electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS) and reversed-phase liquid chromatography (LC-MS). Nitrated and nitroxidized PS species were identified and structurally characterized by tandem mass spectrometry using higher collisional (HCD) and low collision-induced dissociation (CID) methods. The radical scavenging capacity of nitrated POPS against 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH●) and 2,2-azino-bis-3-ethylbenzthiazoline-6-sulphonic acid (ABTS●+) radicals were also evaluated.

2. Results and Discussion

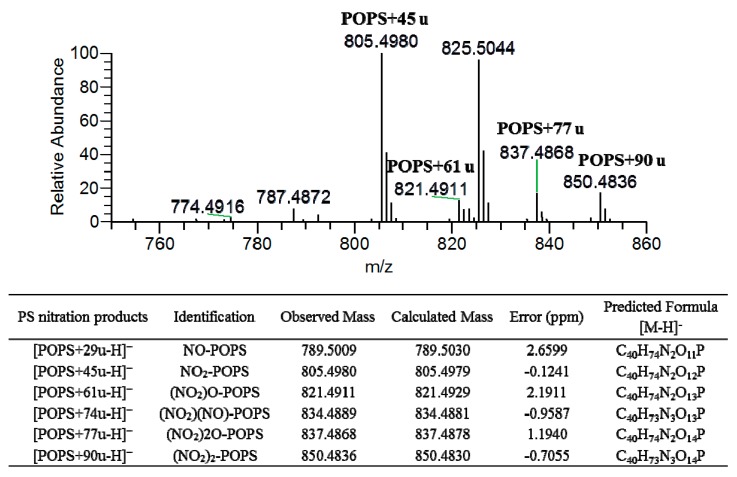

In this study, the nitration of POPS was induced in a mimetic system of nitration by incubation with nitronium tetrafluoroborate (NO2BF4). The reaction occurred in hydrophobic environments, mimicking the nitration that occurs in biological membranes [24], where reactive nitrogen species (RNS) easily diffuse and accumulate in the phospholipid bilayers [25,26,27]. NO2BF4, a salt of nitronium ion (NO2+), has been used to induce the nitration of phospholipids [15,16] and fatty acids [12]. It was previously reported that NO2BF4 is able to mimic the nitration induced by peroxynitrite and nitrite [28], and the nitrated lipids formed under these conditions were described to be similar to those identified in biological samples showing the same fragmentation pattern as nitrated lipids found in plasma and lipoproteins [28]. The formation of nitrated and nitroxidized products of POPS after reaction with NO2BF4 was monitored by ESI-MS in the negative-ion mode in a Q-Exactive Orbitrap (Figure 1). The nitrated and nitroxidized PS products were identified as [M − H]− ions, as summarized in Table 1. These products were assigned as nitroso (NO-PS, POPS + 29 u) at m/z 789.5009, the most abundant product nitro (NO2-PS, POPS + 45 u) at m/z 805.4980, dinitro ((NO2)2-PS, POPS + 90 u) at m/z 850.4836, and nitronitroso ((NO2)(NO)-PS, POPS + 74 u) derivatives at m/z 834.4889. Nitroxidized PSs, namely nitrohydroxy ((NO2)O-PS, POPS + 61 u) at m/z 821.4911, and nitrohydroperoxy ((NO2)2O-PS, POPS + 77 u) at m/z 837.4868 were also identified. These type of modifications have been reported in the previous studies of modifications of PCs and PEs by RNS [16]. The nitrated and nitroxidized PS derivatives were assigned based on the mass shift compared with the unmodified POPS, as well as the accurate mass measurement and elemental composition determination (Figure 1). Tandem mass spectra (Figure 2 and Table 1) were analyzed in order to pinpoint the specific fragmentation fingerprinting and the typical reporter ions of each modification. All the product ions displayed in Table 1 are coming from higher CID (HCD) fragmentation obtained in the high resolution Q-Exactive Orbitrap, which were also confirmed and assigned based on accurate mass measurement. MS/MS spectra were obtained using low CID and higher CID (HCD), respectively, using low-resolution Linear Ion Trap (LIT) and in a high-resolution Orbitrap mass spectrometers. The analysis in a LIT also allowed performing MSn experiments. Reversed-phase LC-MS and MS/MS experiments were also implemented in order to confirm the proposed assignments and to unveil the presence of possible isomeric structures.

Figure 1.

ESI-MS spectrum of POPS after nitration reaction acquired in the negative-ion mode in Q-Exactive Orbitrap. Assignments of nitrated and nitroxidized derivatives formed after reaction between NO2BF4 and POPS observed in the ESI-MS spectrum as [M − H]− ions were confirmed by mass accuracy. The calculated and observed mass, error, and formula of the nitrated and nitroxidized derivatives formed after reaction between NO2BF4 and POPS observed in the ESI-MS spectrum are also shown. Error (ppm) = (Observed m/z − Calculated m/z)/Calculated m/z) × 1 × 106.

Table 1.

Neutral losses and product ions observed in the ESI-MS/MS spectra acquired in the Q-Exactive Orbitrap mass spectrometer (HCD) of the nitrated and nitroxidized derivatives formed after reaction between NO2BF4 and POPS, with the proposed identification, calculated and observed mass, error, and formula. Error (ppm) = (Observed m/z − Calculated m/z)/Calculated m/z) × 1 × 106.

| Neutral Losses | Proposed Precursor Ion Identification | Calculated m/z | Observed m/z | Error (ppm) | Formula |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Precursor ion | [POPS + 29 u − H]− | 789.5030 | 789.5033 | 0.3800 | C40H74N2O11P |

| NO-POPS | |||||

| Product ions | |||||

| 87 u | -C3H5NO2 | 702.4701 | 702.4710 | 1.2812 | C37H69NO9P |

| -- | [NO-OA − H]− | 310.2382 | 310.2390 | 2.5787 | C18H32NO3 |

| -- | [(NO-OA) − HNO − H]− | 279.2324 | 279.2332 | 2.8650 | C18H31O2 |

| -- | R1COO− | 255.2324 | 255.2330 | 2.3508 | C16H31O2 |

| -- | C3H6O5P− | 152.9953 | 152.9948 | −3.2681 | C3H6O5P |

| Precursor ion | [POPS + 45 u − H]− | 805.4979 | 805.4986 | 0.8690 | C40H74N2O12P |

| NO2-POPS | |||||

| Product ions | |||||

| 47 u | -HNO2 | 758.4972 | 758.4982 | 1.3184 | C40H73NO10P |

| 87 u | -C3H5NO2 | 718.4659 | 718.4665 | 0.8351 | C37H69NO10P |

| 134 u (47 + 87) | -(C3H5NO2 + HNO2) | 671.4652 | 671.4659 | 1.0425 | C37H68O8P |

| -- | [NO2-OA − H]− | 326.2331 | 326.2339 | 2.3480 | C18H32NO4 |

| -- | [(NO2-OA) − HNO2 − H]− | 279.2324 | 279.2330 | 2.1487 | C18H31O2 |

| -- | R1COO− | 255.2324 | 255.2329 | 1.9590 | C16H31O2 |

| -- | C3H6O5P− | 152.9953 | 152.9948 | −3.2681 | C3H6O5P |

| Precursor ion | [POPS + 61 u − H]− | 821.4929 | 821.4940 | 1.3390 | C40H74N2O13P |

| (NO2)O-POPS | |||||

| Product ions | |||||

| 47 u | -HNO2 | 774.4921 | 774.4928 | 0.9038 | C40H73NO11P |

| 87 u | -C3H5NO2 | 734.4608 | 734.4620 | 1.6339 | C37H69NO11P |

| 134 u (47 + 87) | -(C3H5NO2 + HNO2) | 687.4601 | 687.4610 | 1.3092 | C37H68O9P |

| -- | [(NO2)O-OA − H]− | 342.2281 | 342.2287 | 1.7532 | C18H32NO5 |

| -- | [(NO2)O-OA) − HNO2 − H]− | 295.2273 | 295.2279 | 2.0323 | C18H31O3 |

| -- | R1COO− | 255.2324 | 255.2330 | 2.3508 | C16H31O2 |

| -- | C3H6O5P− | 152.9953 | 152.9948 | -3.2681 | C3H6O5P |

| Precursor ion | [POPS + 74 u − H]− | 834.4881 | 834.4883 | 0.2397 | C40H73N3O13P |

| (NO2)(NO)-POPS | |||||

| Product ions | |||||

| 87 u | -C3H5NO2 | 747.4561 | 747.4547 | −1.8730 | C37H68N2O11P |

| 134 u (47 + 87) | -(C3H5NO2 + HNO2) | 700.4553 | 700.4562 | 1.2849 | C37H67NO9P |

| -- | [(NO2)(NO)-OA − H]− | 355.2233 | 355.2255 | 6.1933 | C18H31N2O5 |

| -- | [(NO2)(NO)-OA) − HNO2 − H]− | 308.2226 | 308.2234 | 2.5955 | C18H30NO3 |

| -- | R1COO− | 255.2324 | 255.2329 | 1.9590 | C16H31O2 |

| -- | C3H6O5P− | 152.9953 | 152.9948 | −3.2681 | C3H6O5P |

| Precursor ion | [POPS + 77 u – H]− | 837.4878 | 837.4866 | −1.4329 | C40H74N2O14P |

| (NO2)2O-POPS | |||||

| Product ions | |||||

| 47 u | -HNO2 | 790.4870 | 790.4866 | −0.5060 | C40H73NO12P |

| 87 u | -C3H5NO2 | 750.4557 | 750.4569 | 1.5990 | C37H69NO12P |

| 134 u (47 + 87) | -(C3H5NO2 + HNO2) | 703.4550 | 703.4548 | −0.2843 | C37H68O10P |

| -- | [(NO2)2O-OA − H]− | 358.2230 | 358.2239 | 2.6129 | C18H32NO6 |

| -- | [(NO2)2O-OA) − O2 − H]− | 326.2331 | 326.2338 | 2.1457 | C18H32NO4 |

| -- | [(NO2)2O-OA) − HNO2 − H]− | 311.2222 | 311.2230 | 2.5705 | C18H31O4 |

| -- | R1COO− | 255.2324 | 255.2329 | 1.9590 | C16H31O2 |

| -- | C3H6O5P− | 152.9953 | 152.9948 | −3.2681 | C3H6O5P |

| Precursor ion | [POPS + 90 u − H]− | 850.4830 | 850.4835 | 0.5879 | C40H73N3O14P |

| (NO2)2-POPS | |||||

| Product ions | |||||

| 47 u | -HNO2 | 803.4823 | 803.4825 | 0.2489 | C40H72N2O12P |

| 87 u | -C3H5NO2 | 763.4510 | 763.4517 | 0.9300 | C37H68N2O12P |

| 134 u (47 + 87) | -(C3H5NO2 + HNO2) | 716.4503 | 716.4513 | 1.3958 | C37H67NO10P |

| 181 u (94 + 87) | -(C3H5NO2 + 2HNO2) | 669.4495 | 669.4505 | 1.4938 | C37H66O8P |

| -- | [(NO2)2-OA − H]− | 371.2182 | 371.2191 | 2.4245 | C18H31N2O6 |

| -- | [((NO2)2-OA) − HNO2 − H]− | 324.2175 | 324.2182 | 2.1590 | C18H30NO4 |

| -- | [((NO2)2-OA) − 2HNO2 2013 H]− | 277.2168 | 277.2174 | 2.1644 | C18H29O2 |

| -- | R1COO− | 255.2324 | 255.2329 | 1.9590 | C16H31O2 |

| -- | C3H6O5P− | 152.9953 | 152.9948 | −3.2681 | C3H6O5P |

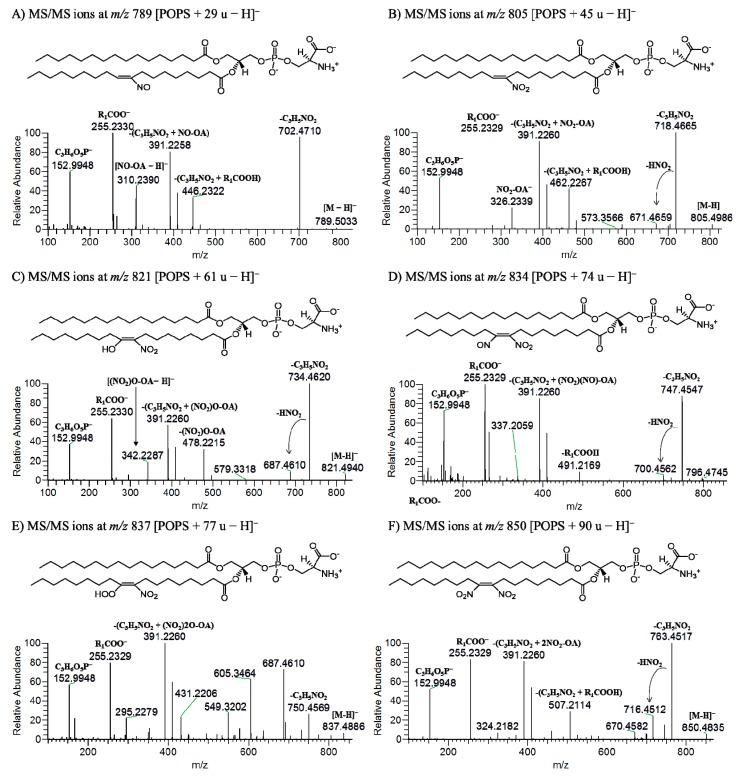

Figure 2.

ESI-MS/MS spectra obtained in Q-Exactive Orbitrap of [M − H]− ions of nitroso, nitrated and nitroxidized POPS at m/z 789.5009 ([POPS + 29 u − H]−) assigned as NO-POPS (A), at m/z 805.4980 ([POPS + 45 u − H]−) assigned as NO2-POPS (B), at m/z 821.4911 ([POPS + 61 u − H]−) assigned as (NO2)O-POPS (C), at m/z 834.4889 ([POPS + 74 u − H]−) assigned as (NO2)(NO)-POPS (D), at m/z 837.4868 ([POPS + 77 u − H]−) assigned as (NO2)2O-POPS (E), and at m/z 850.4836 ([POPS + 90 u − H]−) assigned as (NO2)2-POPS (F). One possible chemical structure of each deprotonated molecule is also proposed, with the nitro group located in C9, but other possibilities should be considered, namely the nitro group at C10, as reported for the nitration of oleic acid [12].

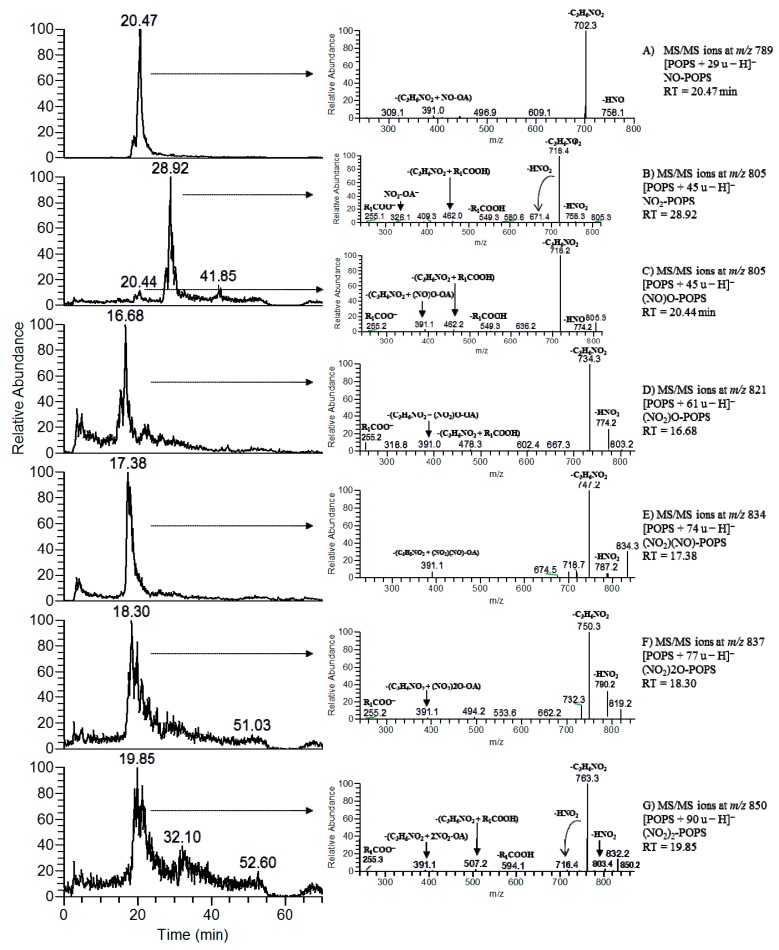

The nitroso derivative (NO-POPS) displayed a mass shift of plus 29 u in comparison with the native POPS. In the tandem mass spectrum (MS/MS) of the [M − H]− ion of NO-POPS at m/z 789.3, acquired in the LIT instrument, it was possible to observe the product ion at m/z 758.3, formed due to the loss of HNO, but no neutral loss of nitrous acid (HNO2) was observed (Figure S1A). Product ion identified as R2COO−, corresponding to the modified fatty acyl chain (NO-OA), were observed at m/z 310.2. The observed neutral loss of 87 u (ions at m/z 702.3) confirmed the presence of the serine polar head. The MS3 spectrum of the precursor ions at m/z 702.3 also showed the typical neutral loss of HNO (m/z 671.3) and the carboxylate anions of fatty acyl chain (m/z 310.2). It was not possible to observe the loss of HNO from the modified fatty acyl chain in both MS/MS and MS3 spectra. Tandem mass spectrum of the precursor ions at m/z 789.5033, acquired in the Orbitrap instrument, revealed the product ions formed by neutral loss of 87 at m/z 702.4701, the carboxylate anion of NO-OA at m/z 310.2382, and also the neutral loss of HNO from NO-OA at m/z 279.2324 (Figure 2A). After LC-MS analysis, the reconstructed ion chromatogram (RIC) of [NO-POPS − H]− showed only one peak, suggesting the presence of only one modified species (Figure 3A). The MS/MS spectrum obtained at the retention time (RT) of 20.47 min showed the neutral loss of HNO, confirming the presence of the nitroso derivative.

Figure 3.

Reconstructed ion chromatogram (RIC) and LC-MS/MS spectra (A–G) of nitrated and nitroxidized derivatives of POPS at m/z 789 identified as nitroso POPS (RT 20.47 min) (A), isobaric compounds at m/z 805 identified as nitro (RT 28.92) (B) and nitrosohydroxy POPS (20.44 min) (C), at m/z 821 identified as nitrohydroxy POPS (RT 16.68 min) (D), at m/z 834 identified as nitronitroso POPS (RT 17.38 min) (E), at m/z 837 identified as nitrohydroperoxy POPS (RT 18.30 min) (F), and at m/z 850 identified as dinitro POPS (RT 19.85 min) (G).

Nitro (or nitroalkene) derivatives of PS displayed a mass shift of 45 u. The MS/MS spectra of the precursor ion at m/z 805.2 in LIT (Figure S1B) and m/z 805.4986 in Orbitrap (Figure 2B), showed ions formed due to the neutral loss of 87 u, at m/z 718.4665, arising from the loss of serine head group, the typical neutral loss of 47 u (-HNO2) at m/z 758.4982, the neutral loss of 134 u (combined neutral loss of 87 u + 47 u) at m/z 671.4659, and R2COO− product ions of modified oleic acid (NO2-OA at m/z 326.2339 and (NO2-OA)-HNO2 at m/z 279.2330). Comparing the MS/MS spectra obtained from low CID and HCD, the same product ions were observed, but the neutral loss of 134 u (combined loss of 87 u + 47 u) and the carboxylate anions [NO2-OA − H]− and [(NO2-OA) − HNO2 − H]− were more abundant in HCD MS/MS spectrum. These ions can be selectively used as reported ions and for neutral loss scanning in order to identify the NO2-PS in biological samples. Nevertheless, the MS3 data at of the product ion at m/z 805.2→m/z 718.3 (NO2-POPS − 87 u), acquired in the LIT (Figure S1B1), also showed product ion formed by the neutral loss of HNO2 at m/z 671.3, and the carboxylate anions of NO2-OA at m/z 326.1 and (NO2-OA) − HNO2 at m/z 279.2, confirming the presence of the nitro group. In the LC-MS experiment, the ions at m/z 805.2 eluted in two different peaks, a major one that eluted latter at RT of 28.9 min and that corresponded to NO2-POPS, and a minor one that eluted earlier at RT of 20.4 min, which was assigned as (NO)O-POPS, an isobaric and structural isomeric species of NO2-POPS. The LC-MS/MS spectrum of the ion at m/z 805.3, acquired at RT of 20.44 min (Figure 3C), showed ion formed due to the neutral loss of HNO at m/z 774.2, but no neutral loss of HNO2 was observed, indicating the presence of a nitroso derivative and confirming the proposed assignment. On the other hand, the LC-MS/MS spectrum obtained at RT of 28.92 min (Figure 3B) showed a product ion at m/z 758.3, corresponding to the neutral loss of HNO2, and thus confirming the presence of a nitro group and the presence of a nitro derivative (NO2-POPS). Therefore, modified species eluting at a RT of 20.44 min were assigned as nitrosohydroxy derivatives ((NO)O-POPS), as previously reported for nitrated and nitroxidized PC and PE [16]. Nevertheless, the nitro derivative of POPS is clearly present, with a higher relative abundance.

Other nitrated PS product with a mass shift of plus 74 u, identified at m/z 834.6 in LIT and m/z 834.4883 in Orbitrap instruments, was assigned as nitronitroso derivatives ((NO2)(NO)-POPS). The MS/MS spectra obtained in both instruments showed product ions corresponding to loss of serine polar head (neutral loss of 87 u), neutral loss of 47 u (-HNO2), neutral loss of 134 u (87 u + 47 u), the carboxylate anions of nitronitroso oleic acid ((NO2)(NO)-OA), and the neutral loss of HNO2 from (NO2)(NO)-OA (Figure 3D, Figure S2 A,A1). These ions eluted in one peak (RT of 17.38 min) and the LC-MS/MS spectrum showed the neutral loss of HNO2 (Figure 3E).

We also found a product formed due to the insertion of two nitro groups with a mass shift of plus 90 u (m/z 850.4835 in Orbitrap and m/z 850.3 in LIT). The MS/MS spectrum acquired in Orbitrap (Figure 2F) showed ions formed due to the loss of serine polar head (neutral loss of 87 u) at m/z 763.4517, neutral loss of HNO2 at m/z 803.4825, and neutral loss of serine polar head combined with the loss of one (134 u (neutral loss of 87 u + 47 u)) and two HNO2 molecules (181 u (neutral loss of 87 u + 94 u)) at m/z 716.4513 and 669.4505, respectively. These two consecutive neutral losses of HNO2 confirmed the presence of two nitro groups and hence the presence of a PS dinitro derivative. Carboxylate anions of dinitro oleic acid ((NO2)2-OA) were also detected at m/z 371.2191, together with product ions formed due to the neutral loss of one and two HNO2 from the (NO2)2-OA at m/z 324.2182 and 277.2174, respectively. MS/MS and MS3 spectra obtained in LIT also showed product ions formed by the two consecutive neutral losses of HNO2 and thus confirming the presence of the dinitro derivative (Figure S2B–B2). Major differences between MS/MS spectra from LIT and Orbitrap are related with the abundance of carboxylate anions of modified fatty acyl chain and product ions arising from combined losses of HNO2 and serine polar head, which are more abundant in the case of HCD, in opposition to ions arising from the loss of HNO2 that are present with higher abundance in CID. This modified PS eluted in one peak (RT of 19.85 min), and the LC-MS/MS spectrum showed the neutral loss of HNO2, confirming the presence of only one species (Figure 3G).

Nitrohydroxy (Figure 2C, Figure S3A–A3) and nitrohydroperoxy derivatives (Figure 2E, Figure S3B–B2) of POPS were also observed and characterized by tandem mass spectrometry. The typical fragmentation pathway of these species involves the neutral loss of serine polar head, the typical neutral loss of 47 u (HNO2), and the neutral loss of HNO2 combined with loss of serine head group. Carboxylate anions of modified oleic acid and product ions formed by neutral loss of HNO2 and O2 (only for nitrohydroperoxy derivative) from the modified oleic acid were also observed. Each derivative eluted in one peak (RT of 16.68 and 18.30 min, respectively) and their LC-MS/MS spectra also showed the neutral loss of HNO2.

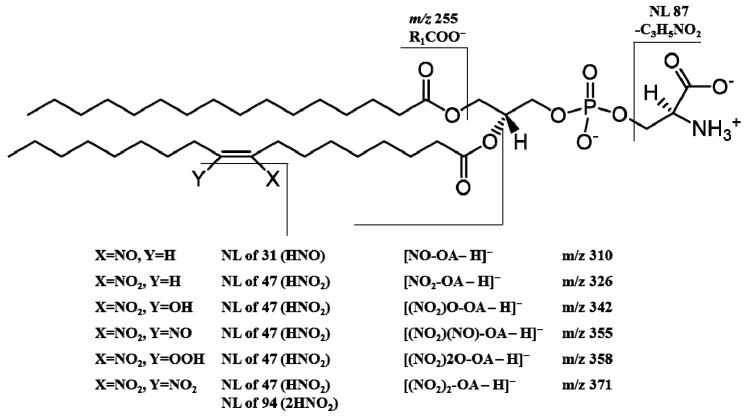

Comparing the information displayed in MS/MS data from CID and HCD, the major observed differences were related with different relative abundance of specific product ions. In general, the typical reporter ions for the identification of nitrated and nitroxidized POPS, that corresponds to the formation of product ions with higher m/z values, seems to be present in high relative abundance in MS/MS spectra from LIT, while low m/z reporter ions, namely the carboxylate anions correspondent to the modified fatty acyl chain, can be seen with a higher relative abundance in MS/MS spectra acquired in the Orbitrap. These variations are related to the different methods of ion activation during MS/MS experiments. It is well-.known that HCD (used in Orbitrap instruments) is able to enhance the yield of low molecular weight fragment ions due to the multiple collisions of both precursor and fragments ions with the gas molecules [29]. Thereby, it becomes essential to disclose the most relevant fragmentation pathways obtained when using different MS platforms and define the most useful neutral losses and reporter ions for accurate identification of these modified lipid species in complex biological matrices [30]. Since high-resolution instruments with Orbitrap technology that use as fragmentation method HCD are now being popular in lipidomic-based approaches, the detailed characterization of the fragmentation patterns of nitrated and nitroxidized PS becomes essential. The typical fragmentation profile provided with the mimetic model used in this study (summarized in Table 2 and Figure 4) can be used for the identification of these modified phospholipids in complex biological matrices, as already reported for mimetic models of nitration of PCs and PEs [15,16].

Table 2.

Typical neutral losses observed in tandem mass spectra of nitrated and nitroxidized derivatives of POPS.

| Mass Shift to Unmodified PS | Typical Neutral Losses in MS/MS | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Nitrated Derivatives | |||

| NO-PS | Nitroso | +29 u | −31 u (HNO) |

| NO2-PS | Nitro | +45 u | −47 u (HNO2) |

| (NO2)(NO)-PS | Nitronitroso | +74 u | −31 u (HNO); −47 u (HNO2) |

| (NO2)2-PS | Dinitro | +90 u | −47 u (HNO2); −94 u (2HNO2) |

| Nitroxidized Derivatives | |||

| (NO)O-PS | Nitrosohydroxy | +45 u | −31 u (HNO) |

| (NO2)O-PS | Nitrohydroxy | +61 u | −47 u (HNO2) |

| (NO2)2O-PS | Nitrohydroperoxy | +77 u | −47 u (HNO2); −32 u (O2) |

| Product Ions | Typical Modified Carboxylate Anions in MS/MS | ||

| [NO-OA − H]− | NO-PS | m/z 310.2 | |

| [(NO-OA) − HNO − H]− | m/z 279.2 | ||

| [NO2-OA − H]− | NO2-PS | m/z 326.2 | |

| [(NO2-OA) − HNO2 − H]− | m/z 279.2 | ||

| [(NO2)O-OA − H]− | (NO2)O-PS | m/z 342.2 | |

| [(NO2)O-OA) − HNO2 − H]− | m/z 295.2 | ||

| [(NO2)(NO)-OA − H]− | (NO2)(NO)-PS | m/z 355.2 | |

| [(NO2)(NO)-OA) − HNO2 − H]− | m/z 308.2 | ||

| [(NO2)2O-OA − H]− | (NO2)2O-PS | m/z 358.2 | |

| [((NO2)2O-OA) − O2 − H]− | m/z 326.2 | ||

| [((NO2)2O-OA) − HNO2 − H]− | m/z 311.2 | ||

| [(NO2)2-OA − H]− | (NO2)2-PS | m/z 371.2 | |

| [((NO2)2-OA) − HNO2 − H]− | m/z 324.2 | ||

| [((NO2)2-OA) − 2HNO2 − H]− | m/z 277.2 | ||

Figure 4.

Schematic representation of major fragmentation pathways of nitrated POPS derivatives observed in negative-ion mode. A possible chemical structure of nitrated POPS with the nitro (NO2) and nitroso (NO) groups located in C9 is represented, but other possibilities should be considered, namely the nitro (NO2) and nitroso (NO) groups at C10, as reported for the nitration of oleic acid [12].

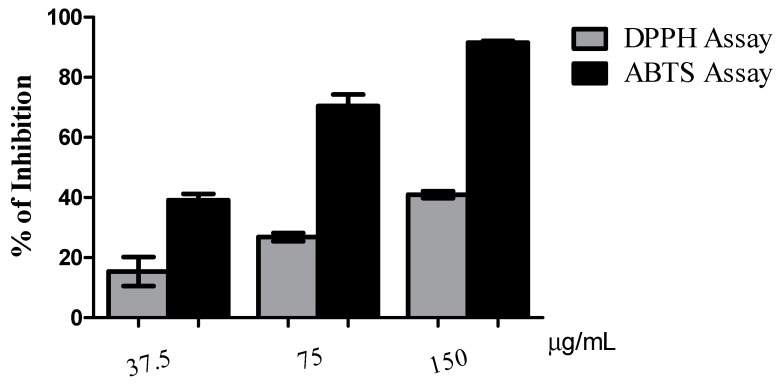

Previous results showed that nitrate POPC could have health protective effects as an antioxidant due to its capability of trapping harmful radicals [17], since it was able to scavenge the ABTS●+, DPPH●, and oxygen-derived radicals (ORAC assay), and protect against lipid peroxidation induced by the hydroxyl radical [17]. In this study, we have further evaluated the ability of non-modified POPS and nitrated POPS to trap radicals as H-atom donator and thus act as a scavenger of radicals, by performing experiments with DPPH● and ABTS●+ radicals. Both assays were performed using all the nitration reaction mixture of POPS.

To evaluate the antioxidant activity of nitrated POPS, the decrease of absorbance at 517 nm and 734 nm for DPPH● and ABTS●+ radicals, respectively, was measured and was expressed as the variation of the amount of both radicals (in percentage). The percentage of inhibition was calculated for each assay, and both DPPH● and ABTS●+ radicals were reduced in the presence of nitrated POPS (Figure 5). For non-modified POPS, only a slight decrease of absorbance was observed at 517 nm and 734 nm for DPPH● and ABTS●+ radicals, respectively, suggesting that non-modified POPS has lower potential as radical scavenger (Figure S4). This decrease was concentration-dependent, and the higher the amount of nitrated POPS, the higher the inhibition of DPPH● and ABTS●+ radicals, and therefore the lower the percentage of radicals remaining after the reaction time. For ABTS●+ assay, the IC50 value was 48.71 µg/mL and the TE of 429.35 µmol Trolox/ g of nitrated POPS. For DPPH● assay, we were not able to calculate the IC50 value since the percentage of inhibition was lower than 50%, and thus we calculated the IC25 value, which was 75.16 µg/mL while the TE value was 185.82 µmol Trolox/ g of nitrated POPS. These results suggest that nitrated POPS has higher reactivity and thus higher H-atom donating ability in the aqueous medium than in organic environments. This is in agreement with previous information that also states that NO2-FA decay faster in aqueous medium [31] than in hydrophobic environments as the biological membranes, where they are hydrophobically stabilized. This high reactivity of nitrated POPS in hydrophilic media can be related with its biological roles in physiologically relevant conditions, which can also occur via formation of other biologically relevant species [32]. Additionally, these results are similar with the ones reported for nitrated POPC in the same conditions, which is quite interesting because nitrated POPC was also reported with anti-inflammatory activity [17]. Nevertheless, the ability of nitrated POPS to quench the DPPH● and ABTS●+ radicals was higher when comparing with the data from nitrated POPC, which was demonstrated by the lower IC values and higher TE for nitrated POPS [17]. In the literature, it was reported that the primary amine moiety of PS could act as an electron donator rather than the tertiary amine moiety of PC, which allowed PS to be a more effective scavenger of lipid peroxyl radicals [33]. Also, it was reported that NO2 moiety of the NO2-OA accumulates near the phosphate group of phospholipid polar head, at the membrane-water interface. This accumulation shields the NO2 moiety from the hydrophobic environments, where NO2-FA exist in a stabilized form, making it more reactive [34]. Moreover, H-atom donating ability was previously described for NO2-FA [32]. The synergic relationship between PS polar head group, acting as an active electron donator, and NO2 moiety, acting as an H-atom donator, can be related with the apparent high antioxidant potential of nitrated POPS, when compared with nitrated POPC. The ability of nitrated PS to act as scavenger could be interesting at the biological level also due to the combination of different mechanisms of antioxidant (inter)actions. The anionic polar head group of PS can also display antioxidant actions through the ability of chelating iron ions and preventing the decomposition of hydroperoxides, reducing the lipid peroxidation chain reaction [35,36].

Figure 5.

Percentage of inhibition of DPPH● and ABTS●+ radicals remaining after 120 min of reaction in the presence of nitrated POPS at the three concentrations tested (37.5, 75 and 150 µg/mL in ethanol).

Altogether, the results gathered with this study highlight the need to keep up with the research in the field of phospholipid nitration, improving the detection of these species and contributing to the understanding of their biological roles.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Reagents/Chemicals

The 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-l-serine (POPS) standard was purchased from Avanti® Polar Lipids, Inc. (Alabaster, AL, USA) and used without further purification. Nitronium tetrafluoroborate (NO2BF4) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Madrid, Spain). Perchloric acid 70% was purchased from Panreac (Barcelona, Spain). Ammonium molybdate and sodium dihydrogen phosphate dehydrated (NaH2PO4·2H2O) were purchased from Riedel-de Haёn (Seelze, Germany). Ascorbic acid was purchased from VWR International (Leicestershire, UK). HPLC grade chloroform, methanol and acetonitrile were purchased from Fisher Scientific Ltd. (Leicestershire, UK). Milli-Q water was filtered through a 0.22-mm filter and obtained using a Milli-Q Millipore system (Synergy®, Millipore Corporation, Billerica, MA, USA).

3.2. Nitration of Phosphatidylserines

Phosphatidylserine nitration was carried out with nitronium tetrafluoroborate (NO2BF4), as previously described [15,16]. A solution of POPS (1 mg) in chloroform (1 mL) was prepared in an amber vial tube, and an excess of the solid NO2BF4 (≈1 mg) was added. The reaction mixture was incubated at room temperature for 1h, under orbital shaking at 750 rpm. After incubation, the mixture was transferred to a centrifuge glass tube, and the reaction was stopped by solvent extraction with Milli-Q water to hydrolyze unreacted NO2BF4 and/or to separate contaminating anions (such as nitrite (NO2−), nitrate (NO3−), and the tetrafluoroborate anion (BF4−)) from phospholipids [15,16,24]. The mixture was vortexed for 30 s and then centrifuged at room temperature at 2000 rpm for 10 min using a Mixtasel Centrifuge (Selecta, Barcelona, Spain). The organic layer containing the nitrated and nitroxidized derivatives of POPS was collected, evaporated under a nitrogen stream, and stored at −20 °C to be further quantified using a phosphorous assay [37], and analyzed by ESI-MS and reverse phase liquid chromatography coupled to ESI-MS (C5-RP-LC-MS) and MS/MS.

3.3. Phosphorous Measurement-Phospholipid Quantification

The total amount of nitrated and nitroxidized products of POPS recovered after extraction was quantified with the phosphorus assay, as previously described by Bartlett and Lewis [37], with modifications. Briefly, 125 µL of perchloric acid (70% m/v) was added to 10 µL of nitrated POPS (stock-solution was dissolved in 1 mL of CHCl3). The solution was dried under a nitrogen stream before the addition of perchloric acid. The nitrated POPS was then incubated for 1 h at 180 °C in the heating block (Stuart®, London, UK). Afterward, 825 µL of H2O, 125 µL of 2.5% ammonium molybdate (m/v; 2.5 g of NaMoO4·H2O in 100 mL of Milli-Q H2O) and 10% ascorbic acid (m/v; 0.1 g in 1 mL Milli-Q H2O) were added with homogenization in a vortex mixer after each addition. Then, the nitrated POPS was incubated for 10 min at 100 °C in a water bath. Standards from 0.1 to 2 µg of phosphate (NaH2PO4·2H2O, 100 μg of phosphorus per mL) underwent the same sample treatment, with the exception of the heating block phase. A volume of 200 µL of each standard and nitrated POPS were added to the 96-well multiwell plate, and the absorbance was measured at 797 nm in a Multiskan GO Microplate Spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Hudson, NH, USA)). The amount of phosphorus was calculated by linear regression analysis. The amount of nitrated POPS was directly calculated by multiplying the amount of phosphorus by 25.

3.4. Mass Spectrometry Conditions

Analysis of nitrated and nitroxidized products of POPS was carried out in a negative-ion mode in an LXQ linear ion trap (LIT) mass spectrometer (ThermoFinnigan, San Jose, CA, USA), as previously described [15,16]. Nitrated POPS (aliquot of 4 µg), dissolved in methanol (2:100, v/v), were introduced through direct infusion, and the ESI conditions were as follows: flow rate of 8 µL min-1; electrospray voltage of 4.7 kV; capillary temperature of 275 °C and the sheath gas flow of 8 units. An isolation width of 1 Da was used with a 30 ms activation time for MS/MS experiments. Full scan MS spectra and MS/MS spectra were acquired with a 50 ms and 200 ms maximum ion injection time, respectively. Low energy CID-MS/MS experiments were conducted using normalized collision energyTM, between 20 and 30 (arbitrary units) for MS/MS. Data acquisition and results treatment were carried out with an Xcalibur Data System (version 2.0, ThermoFinnigan, San Jose, CA, USA).

High-mass-resolving ESI-MS used for the accurate mass measurements and HCD-MS/MS experiments were conducted in a Q-Exactive® hybrid quadrupole Orbitrap® mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Bremen, Germany). The instrument was operated in the negative-ion mode, with a spray voltage at 2.7 kV, and interfaced with a HESI II ion source. Nitrated POPS were diluted from of 1 mg mL−1 stock solutions (in chloroform) using MeOH to a final concentration of 4 µg mL−1. The analysis were performed through direct infusion of the prepared solutions at a flow rate of 12 µL min−1 into the ESI source, and the operating conditions were as follows: Sheath gas (nitrogen) flow rate 5 (arbitrary units); auxiliary gas (nitrogen) 1 (arbitrary units); capillary temperature 250 °C, and S-lens RF level 50. The acquisition method was set with a full scan and resolution of 70,000, the m/z ranges were set to 100–1500 in negative and positive ion mode during full-scan experiments. The automatic gain control (AGC) target was set at 3 × 106 and the maximum injection time (IT) was 250 ms. MS spectra were acquired during 30 s. The Q-Exactive system was tuned and calibrated using peaks of known mass from a calibration solution (Thermo Scientific, San Jose, CA, USA) to achieve a mass accuracy of <5 ppm RMS. Spectra were analyzed using the acquisition software XCalibur ver. 3.0 (Thermo Scientific). In order to obtain the product ion spectra of the nitrated derivatives of POPS and PLPS during ESI-MS experiments, the selected precursor ions were isolated by the quadrupole and sent to the higher-energy collision dissociation (HCD) cell for fragmentation via the C-trap. In the MS/MS mode, the mass resolution of the Orbitrap analyzer was set at 70,000, AGC target 3 × 106, maximum IT 250 ms, isolation window 1.0 m/z, and normalized collision energy (NCE) was 25 (arbitrary units). Nitrogen was also used as collision gas. All experiments were repeated at least three times on different days.

3.5. Reverse Phase High-Performance Liquid Chromatography/Tandem Mass Spectrometry

The nitrated and nitroxidized products of POPS were separated and identified by HPLC-ESI-MS and characterized by HPLC-ESI-MS/MS, as previously described [16]. These experiments were performed on a Waters Alliance 2690 HPLC system (Mildford, MA, USA) coupled online to the LXQ linear ion trap (LIT) mass spectrometer (ThermoFinnigan, San Jose, CA, USA). An aliquot of 60 μg of each nitrated mixture (previously dissolved in chloroform, transferred to an Eppendorf tube and dried under a nitrogen stream) was diluted in 40% of mobile phase B (30 μL), and then filtered using a PVDF Millex-GV syringe filter with a 0.22 µm pore size (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). Volumes of 5 μL of each diluted and filtered nitrated mixture were introduced into a Discovery Bio Wide Pore C5 column (15 cm × 0.5 mm, 5 μm particle size; Supelco, Bellefonte, PA, USA), using a flow rate of 16 μL min-1. The mobile phase A consisted of water with 5% acetonitrile and 0.1% formic acid. The mobile phase B consisted of acetonitrile, with 0.1% formic acid. The mobile phase gradient was programmed as follows: initial conditions were 40% of B; 0–35 min, linear increase gradient to 60% of B; 35–45 min linear increase gradient to 100% of B held in isocratic mode for 10 min; 55–60 min linear gradient to 40% of B in order to brought back to the mobile phase to the initial conditions and held in isocratic mode for 5 min allowing to equilibrate the column until the next injection. The flow was then redirected to the LIT mass spectrometer using a homemade flow-splitter. The LIT mass spectrometer was operated both in the positive and the negative ion modes. Typical ESI conditions were as follows: Electrospray voltage of 4.7 kV in the negative-ion mode and 5 kV in the positive-ion mode; capillary temperature, 275 °C; and sheath gas (nitrogen) flow of 25 (arbitrary units). To obtain the product-ion spectra of the major components during LC experiments, cycles consisting of one full scan mass spectrum (m/z 100–1700), and three data-dependent MS/MS scans were repeated continuously throughout the experiments with the following dynamic exclusion settings: repeat count 3; repeat duration 30 s; exclusion duration 45 s. An isolation with of 0.5 Da was used with a 30 ms activation time for MS/MS experiments using helium as the collision gas. The normalized collision energy was 27 (arbitrary units). Data acquisition and processing were carried out on an Xcalibur data system (version 2.0).

3.6. DPPH● Assay

A microplate DPPH● method was used, as previously described [17,38]. DPPH● method was tested for non-modified POPS or nitrated POPS. A stock solution of DPPH● in ethanol (250 µmol/L) was prepared and diluted to obtain a working solution with an absorbance values of 0.9 measured at 517 nm, obtained using an UV-Vis spectrophotometer (Multiskan GO 1.00.38, Thermo Scientific) controlled by SkanIT software version 3.2 (Thermo Scientific™). In order to evaluate the stability of the radical upon reaction time, the absorbance of DPPH● in the absence of antioxidant species (blank) was monitored at 517 nm every 5 min after the beginning of the reaction at room temperature, providing an absorbance decrease of 5% after 120 min. For evaluation of radical scavenging potential, 150 µL of Trolox standard solutions (between 5 and 75 µmol/L in ethanol) and non-modified POPS or nitrated POPS (75, 150 and 300 µg/mL in ethanol) were placed in each well of the 96-Well flat-bottom UV transparent microplates, followed by addition of 150 µL of DPPH● in ethanol. The DPPH● scavenging activity of standards and samples was monitored at 517 nm every 5 min after the beginning of reaction during 120 min, at room temperature. The experiments were performed in triplicate. The antioxidant activity of the tested samples, expressed as a percentage of inhibition of DPPH● radical, was calculated (60 and 120 min) using the following equation:

| % inhibition = (AbsDPPH● − Abssample)/AbsDPPH●) × 100 | (1) |

The IC25 values (concentration of sample that induces a reduction of 25% in the initial DPPH● radical) after 120 min of reaction were calculated by linear regression from the concentration of sample versus percentage of inhibition. The results were also expressed as Trolox equivalent (TE, µmol Trolox/ g of sample). The equation used was:

| TE = IC25 Trolox (µmol/L) × 1000/IC25 of sample (µg/mL) | (2) |

3.7. ABTS●+ Assay

A microplate ABTS●+ method was used, as previously described [17,39]. The ABTS●+ method was tested for non-modified POPS or nitrated POPS. The ABTS●+ radical cation solution was prepared by mixing equal volumes of an ABTS stock solution (7 mmol/L in water) with potassium persulfate (2.45 mmol/L in water). This mixture was kept for 12–16 h at room temperature in the dark and further diluted in acetate buffer (pH 4.6, 50 mmol/L) in order to achieve an absorbance value of 0.9 at 734 nm, acquired using an UV-Vis spectrophotometer (Multiskan GO 1.00.38, Thermo Scientific, Hudson, NH, USA) controlled by SkanIT software version 3.2 (Thermo Scientific™). In order to evaluate the stability of the radical upon reaction time, the absorbance of ABTS●+ in the absence of antioxidant species (blank) was monitored, and the absorbance decrease observed was 5% after 120 min of reaction. For evaluation of radical scavenging potential, 150 µL of Trolox standard solutions (between 5 and 75 µmol/L in ethanol) and non-modified POPS or nitrated POPS (75, 150, and 300 µg/mL in ethanol) were added to the 96-Well flat-bottom UV transparent microplates, followed by addition of 150 µL of ABTS●+ solution. The ABTS●+ scavenging activity of standards and samples was monitored at 734 nm every 5 min after the beginning of reaction during 120 min at room temperature. The experiments were performed in triplicate. The antioxidant activity of the tested samples expressed as a percentage of inhibition of ABTS●+ radical was calculated at specific time-points (60 and 120 min) using the following equation:

| % inhibition = ((AbsABTS●+ − Abssample)/AbsABTS●+) × 100 | (3) |

The IC50 values (concentration of sample that induces the reduction of ABTS●+ radical to 50%) after 120 min of reaction were calculated by linear regression from the concentration of sample versus percentage of inhibition. The results were also expressed as Trolox equivalent (TE, µmol Trolox/g of sample). The equation used was:

| TE = IC50 Trolox (µmol/L) × 1000/IC50 of sample (µg/mL) | (4) |

4. Conclusions

Liquid chromatography coupled with the tandem mass spectrometry experiments performed in this study allowed to perform a broad characterization of the fragmentation profile of nitrated and nitroxidized derivatives of POPS. The information gathered on the typical neutral loss for each modification will be useful for lipidomic-targeted analysis of these nitrated and nitroxidized PS products in complex biological samples. Nevertheless, the confirmation of the final structure should be further accomplished by using complementary infrared and nuclear magnetic resonance analysis. Moreover, this study has identified the potential biological role of nitrated POPS, namely as a scavenging agent. Therefore, the present study contributes to the ongoing effort concerning not only the identification of nitrated phospholipids but also their potential biological roles in biological systems. Nevertheless, further research in this field is needed to provide new data on phospholipid nitration and particularly nitrated phosphatidylserine in biological conditions, and its relevance both in physiological and pathological conditions.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online, Figure S1: ESI-MS/MS spectra obtained in Linear Ion Trap of the [M − H]− ions at m/z 789.3 corresponding to [POPS + 29 u − H]− (A), and at m/z 805.2 corresponding to [POPS + 45 u − H]− (B). MS3 of ions at m/z 702.3 (A1) and m/z 718.3 (B1) that correspond, respectively, to [POPS + 29 u − 87 u − H]− and [POPS + 45 u − 87 u − H]− were also shown., Figure S2: ESI-MS/MS spectra obtained in Linear Ion Trap of [M − H]− ions at m/z 834.6 corresponding to [POPS + 74 u − H]– (A), and at m/z 850.3 corresponding to [POPS + 90 u − H]– (B). MS3 of ions at m/z 747.3 (A1) assigned as [POPS + 74 u − 87 u − H]–, at m/z 763.3 (B1) that correspond to [POPS + 90 u – 87 u – H]–, and at m/z 803.1 attributed to [POPS + 90 u − HNO2 − H]− were also shown., Figure S3: ESI-MS/MS spectra obtained in Linear Ion Trap of [M − H]− ions at m/z 821.4 corresponding to [POPS + 61 u − H]– (A), and at m/z 837.3 corresponding to [POPS + 77 u − H]– (B). MS3 of ions at m/z 734.3 (A1) assigned as [POPS + 61 u − 87 u − H]–, and at m/z 750.3 (B1) assigned as [POPS + 77 u − 87 u − H]– were also shown, Figure S4: Percentage of inhibition of DPPH● and ABTS●+ radicals obtained in the presence of non-modified POPS (37.5, 75 and 150 µg/mL) after 120 min of reaction.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization of the research work was performed by B.N., T.M., and M.d.R.D.; Methodology including sample preparation, extraction protocols, acquisition of (LC)MS and (LC)MS/MS data were performed by B.N. and T.M.; P.D. and T.M. optimized the LC–MS conditions used and supervised the acquisition of (LC)MS and (LC)MS/MS data; Writing-Original Draft Preparation was performed by B.N., T.M. and M.d.R.D.; P.D. and M.M.O. co-wrote the paper; T.M. and M.d.R.D. coordinated all the experiments and data analyses. All authors contributed to the Writing-Review & Editing of the manuscript.

Funding

Thanks are due to University of Aveiro, Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia and Ministério da Educação e Ciência (FCT/MEC), European Union, QREN, COMPETE for the financial support to the QOPNA research Unit (FCT UID/QUI/00062/2013), and Centre for Environmental and Marine Studies (CESAM) (UID/AMB/50017/2013), and also to the Portuguese Mass Spectrometry Network (LISBOA-01-0145-FEDER-402-022125) through national funds and where applicable co-financed by the FEDER, within the PT2020 Partnership Agreement. Tânia Melo (BPD/UI51/5388/2017) is grateful to FCT for her grant.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Sample Availability: Samples of the compounds are not available from the authors.

References

- 1.Vance J.E. Phosphatidylserine and phosphatidylethanolamine in mammalian cells: Two metabolically related aminophospholipids. J. Lipid Res. 2008;49:1377–1387. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R700020-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yeung T., Gilbert G.E., Shi J., Silvius J., Kapus A., Grinstein S. Membrane Phosphatidylserine Regulates Surface Charge and Protein Localization. Science. 2008;319:210–213. doi: 10.1126/science.1152066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vance J.E., Tasseva G. Formation and function of phosphatidylserine and phosphatidylethanolamine in mammalian cells. Biochim. Biophys Acta. BBA-Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids. 2013;1831:543–554. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2012.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leventis P.A., Grinstein S. The Distribution and Function of Phosphatidylserine in Cellular Membranes. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 2010;39:407–427. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.093008.131234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Balasubramanian K., Mirnikjoo B., Schroit A.J. Regulated Externalization of Phosphatidylserine at the Cell Surface: Implications for Apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:18357–18564. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700202200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maciel E., Silva R.N., Simões C., Domingues P., Domingues M.R.M. Structural Characterization of Oxidized Glycerophosphatidylserine: Evidence of Polar Head Oxidation. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2011;22:1804–1814. doi: 10.1007/s13361-011-0194-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maciel E., Neves B.M., Santinha D., Reis A., Domingues P. Detection of phosphatidylserine with a modified polar head group in human keratinocytes exposed to the radical generator AAPH. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2014;548:38–45. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2014.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maciel E., Faria R., Santinha D., Domingues M.R.M., Domingues P. Evaluation of oxidation and glyco-oxidation of 1-palmitoyl-2-arachidonoyl-phosphatidylserine by LC–MS/MS. J. Chromatogr. B. 2013;929:76–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2013.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Melo T., Videira R.A., André S., Maciel E., Francisco C.S., Domingues M.R.M. Tacrine and its analogues impair mitochondrial function and bioenergetics: A lipidomic analysis in rat brain: Effects on non-synaptic brain mitochondria. J. Neurochem. 2012;120:998–1013. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07636.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Matsura T. Oxidized Phosphatidylserine: Production and Bioactivities. Yonago Acta Med. 2014;57:119–127. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Silva R.N., Silva A.C., Maciel E., Simões C. Evaluation of the capacity of oxidized phosphatidylserines to induce the expression of cytokines in monocytes and dendritic cells. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2012;525:9–15. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2012.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Milic I., Griesser E., Vemula V., Ieda N., Nakagawa H., Miyata N. Profiling and relative quantification of multiply nitrated and oxidized fatty acids. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2015;407:5587–5602. doi: 10.1007/s00216-015-8766-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schoeman J.C., Harms A.C., Weeghel M., Berger R., Vreeken R.J., Hankemeier T. Development and application of a UHPLC–MS/MS metabolomics based comprehensive systemic and tissue-specific screening method for inflammatory, oxidative and nitrosative stress. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2018;410:2551–2568. doi: 10.1007/s00216-018-0912-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsikas D., Zoerner A.A., Mitschke A., Gutzki F.M. Nitro-fatty Acids Occur in Human Plasma in the Picomolar Range: A Targeted Nitro-lipidomics GC–MS/MS Study. Lipids. 2009;44:855–865. doi: 10.1007/s11745-009-3332-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Melo T., Domingues P., Ferreira R., Milic I., Fedorova M., Santos S.M., Domingues M.R.M. Recent Advances on Mass Spectrometry Analysis of Nitrated Phospholipids. Anal. Chem. 2016;88:2622–2629. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.5b03407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Melo T., Domingues P., Ribeiro R.T.M., Girão H., Segundo M.A., Domingues M.R.M. Characterization of phospholipid nitroxidation by LC-MS in biomimetic models and in H9c2 Myoblast using a lipidomic approach. Free Radi.c Biol. Med. 2017;106:219–227. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2017.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Melo T., Marques S.S., Ferreira I., Cruz M.T., Domingues P., Domingues M.R.M. New Insights into the Anti-Inflammatory and Antioxidant Properties of Nitrated Phospholipids. Lipids. 2018;53:117–131. doi: 10.1002/lipd.12007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Santinha D.R., Luísa D.M., Neves B.M., Maciel E., Martins J., Helguero L. Prospective phospholipid markers for skin sensitization prediction in keratinocytes: A phospholipidomic approach. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2013;533:33–41. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2013.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tyurina Y.Y., Tyurin V.A., Kapralova V.I., Wasserloos K., Mosher M. Oxidative Lipidomics of γ-Radiation-Induced Lung Injury: Mass Spectrometric Characterization of Cardiolipin and Phosphatidylserine Peroxidation. Radiat. Res. 2011;175:610–621. doi: 10.1667/RR2297.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tsikas D., Zoerner A.A., Jordan J. Oxidized and nitrated oleic acid in biological systems: Analysis by GC–MS/MS and LC–MS/MS, and biological significance. Biochim. Biophys Acta. BBA-Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids. 2011;1811:694–705. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2011.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kühn B., Brat C., Fettel J., Hellmuth N., Maucher I.V., Bulut U. Anti-inflammatory nitro-fatty acids suppress tumor growth by triggering mitochondrial dysfunction and activation of the intrinsic apoptotic pathway in colorectal cancer cells. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2018;155:48–60. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2018.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reddy A.T., Lakshmi S.P., Dornadula S., Pinni S., Rampa D.R., Reddy R.C. The Nitrated Fatty Acid 10-Nitro-Oleate Attenuates Allergic Airway Disease. J. Immunol. 2013;191:2053–2063. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1300730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nie H., Xue X., Liu G., Guan G., Liu H., Sun L. Nitro-oleic acid ameliorates oxygen and glucose deprivation/re-oxygenation triggered oxidative stress in renal tubular cells via activation of Nrf2 and suppression of NADPH oxidase. Free Radic. Res. 2016;50:1200–1213. doi: 10.1080/10715762.2016.1225955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chakravartula S.V.S., Balazy M. Characterization of nitro arachidonic acid and nitro linoleic acid by mass spectrometry. Anal. Lett. 2012;45:2412–2424. doi: 10.1080/00032719.2012.693558. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu X., Miller M.J.S., Joshi M.S., Thomas D.D., Lancaster J.R. Accelerated reaction of nitric oxide with O2 within the hydrophobic interior of biological membranes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:2175–2179. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.5.2175. PMCID: PMC19287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thomas D.D., Liu X., Kantrow S.P., Lancaster J.R. The biological lifetime of nitric oxide: Implications for the perivascular dynamics of NO and O2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:355–360. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.1.355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Denicola A., Batthyány C., Lissi E., Freeman B.A., Rubbo H., Radi R. Diffusion of Nitric Oxide into Low Density Lipoprotein. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:932–936. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106589200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lima E.S., Di Mascio P., Abdalla D.S. Cholesteryl nitrolinoleate, a nitrated lipid present in human blood plasma and lipoproteins. J. Lipid Res. 2003;44:1660–1666. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M200467-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Olsen J.V., Schwartz J.C., Griep-Raming J., Nielsen M.L., Damoc E., Denisov E. A Dual Pressure Linear Ion Trap Orbitrap Instrument with Very High Sequencing Speed. Mol. Cell Proteom. 2008;8:2759–2769. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M900375-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cao X., Cai X., Mo W. Comparing the fragmentation reactions of protonated cyclic indolyl α-amino esters in quadrupole/orbitrap and quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometers. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2018;32:543–551. doi: 10.1002/rcm.8063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lima É.S., Bonini M.G., Augusto O., Barbeiro H.V., Souza H.P., Abdalla D.S.P. Nitrated lipids decompose to nitric oxide and lipid radicals and cause vasorelaxation. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2005;39:532–539. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Manini P., Capelli L., Reale S., Arzillo M., Crescenzi O., Napolitano A. Chemistry of Nitrated Lipids: Remarkable Instability of 9-Nitrolinoleic Acid in Neutral Aqueous Medium and a Novel Nitronitrate Ester Product by Concurrent Autoxidation/Nitric Oxide-Release Pathways. J. Org. Chem. 2008;73:7517–7525. doi: 10.1021/jo801364v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lambelet P., Saucy F., Löliger J. Radical Exchange Reactions between Vitamin E, Vitamin C and Phospholipids in Autoxidizing Polyunsaturated Lipids. Free Radic Res. 1994;20:1–10. doi: 10.3109/10715769409145621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Franz J., Bereau T., Pannwitt S., Anbazhagan V., Lehr A., Nubbemeyer U. Nitrated Fatty Acids Modulate the Physical Properties of Model Membranes and the Structure of Transmembrane Proteins. Chem.-Eur. J. 2017;23:9690–9697. doi: 10.1002/chem.201702041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dacaranhe C.D., Terao J. A unique antioxidant activity of phosphatidylserine on iron-induced lipid peroxidation of phospholipid bilayers. Lipids. 2001;36:1105–1110. doi: 10.1007/s11745-001-0820-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yoshida K., Terao J., Suzuki T., Takama K. Inhibitory effect of phosphatidylserine on iron-dependent lipid peroxidation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1991;179:1077–8101. doi: 10.1016/0006-291X(91)91929-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bartlett E.M., Lewis D.H. Spectrophotometric determination of phosphate esters in the presence and absence of orthophosphate. Anal. Biochem. 1970;36:159–167. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(70)90343-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Magalhães L.M., Segundo M.A., Reis S., Lima J.L. Automatic method for determination of total antioxidant capacity using 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl assay. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2006;558:310–318. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2005.11.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Magalhães L.M., Barreiros L., Maia M.A., Reis S., Segundo M.A. Rapid assessment of endpoint antioxidant capacity of red wines through microchemical methods using a kinetic matching approach. Talanta. 2012;97:473–483. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2012.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.