Abstract

Unfavourable intrauterine environmental factors increase the risk of delivery complications as well as postpartum developmental and behavioural problems in children and adolescents with ongoing effects into older age. Biomarker studies show that maternal stress and the use of alcohol and tobacco during pregnancy are associated with a higher intrauterine testosterone exposure of the child. The antenatal testosterone load, in turn, is a risk factor for lasting adverse health effects which extend into adulthood. A 15-week, mindfulness-oriented, app-based programme for the reduction of stress as well as for the reduction of alcohol and tobacco use in pregnant women is established. In the monocentre, prospective, controlled, and investigator-blinded MINDFUL/PMI (Maternal Health and Infant Development in the Follow-up after Pregnancy and a Mindfulness Intervention) study, pregnant women carry out the programme. Its effect on antenatal testosterone exposure of the child is examined by assessing the index/ring finger length ratio and other biomarkers in the 1-year-old children. In addition, the programmeʼs effects on self-regulation, the developmental status and the mental health of the children at the age of one year will be investigated. Additional aspects of the course of the pregnancy and delivery represent exploratory study objectives. This longitudinal study project is intended to improve the understanding of the impact of intrauterine environmental factors on early childhood development and health. Maternal stress as well as alcohol and tobacco use during pregnancy are modifiable factors and represent potential preventive targets.

Key words: pregnancy, stress, alcohol, tobacco, testosterone, 2D : 4D, index/ring finger length ratio, mindfulness

Zusammenfassung

Ungünstige intrauterine Umweltfaktoren erhöhen das Risiko für Geburtskomplikationen sowie postpartale Entwicklungs- und Verhaltensauffälligkeiten bei den Kindern und Jugendlichen mit permanenten Auswirkungen bis ins höhere Alter. Biomarkerstudien zeigen, dass mütterlicher Stress und Konsum von Alkohol und Tabak während der Schwangerschaft mit höherer intrauteriner Testosteronexposition des Kindes assoziiert sind. Die pränatale Testosteronlast ist wiederum ein Risikofaktor für anhaltende und bis ins Erwachsenenalter reichende Gesundheitsbeeinträchtigungen. Es wird ein 15-wöchiges, achtsamkeitsorientiertes, App-basiertes Programm zur Reduktion von Stress sowie zur Verminderung von Alkohol- und Tabakkonsum bei schwangeren Frauen etabliert. In der monozentrischen, prospektiven, kontrollierten und untersucherverblindeten MINDFUL/PMI (Maternal Health and Infant Development in the Follow-up after Pregnancy and a Mindfulness Intervention)-Studie führen schwangere Frauen das Programm durch. Dabei wird der Effekt auf die pränatale Testosteronexposition des Kindes untersucht, die mit dem Zeige-/Ringfingerlängenverhältnis und weiteren Biomarkern bei den 1-jährigen Kindern erhoben wird. Außerdem soll beforscht werden, wie sich das Programm auf die Selbstregulation, den Entwicklungstand und die psychische Gesundheit der Kinder im Alter von einem Jahr auswirkt. Weitere Aspekte des Schwangerschafts- und Geburtsverlaufs stellen explorative Studienziele dar. Dieses longitudinale Studienprojekt soll das Verständnis der Bedeutung intrauteriner Umweltfaktoren für die frühe kindliche Entwicklung und Gesundheit verbessern. Mütterlicher Stress sowie Alkohol- und Tabakkonsum während der Schwangerschaft sind modifizierbare Faktoren und stellen potenzielle präventive Ansatzpunkte dar.

Schlüsselwörter: Schwangerschaft, Stress, Alkohol, Tabak, Testosteron, 2D : 4D, Zeige-/Ringfingerlängenverhältnis, Achtsamkeit

Background

Maternal behaviour and environmental influences during early childhood development have lifelong effects on individual health and disease risks. The antenatal phase is of particular interest. Maternal stress as well as alcohol and tobacco use during pregnancy negatively affect the delivery as well as the development of newborns and children. It is even assumed that these antenatal developmental factors have a permanent impact on health. A better understanding of the relevant modifiable maternal factors is necessary for the successful establishment of new prevention strategies.

Stress, alcohol and tobacco during pregnancy

Six out of ten pregnant women, thus a considerable percentage, complain of relevant stress. Stress during pregnancy negatively affects both the pregnant woman and the unborn child 1 , 2 . Pregnant women, who report subjective stress, who are exposed to objective stressors or who have higher cortisol values, more often deliver preterm infants 3 and children with a lower birth weight 4 . Children of pregnant women with a high stress level also more often show emotional disorders and cognitive impairments 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 . Mindfulness training reduces stress; it is therefore consistent that mindfulness-oriented meditation training in women during pregnancy exerts a positive effect on several postpartum behavioural characteristics of the infants 10 . It is also interesting that a higher level of mindfulness in women during pregnancy is associated with a better self-regulation in the children 11 .

A rather considerable proportion of pregnant women consume alcohol and smoke tobacco with negative effects on childhood development. The children and adolescent survey (KIGGS), which is representative of Germany (2003 – 2006, 17 641 children and adolescents), shows that between 10 and 20% of pregnant women occasionally smoke and/or drink alcohol. There was even more frequent and higher alcohol consumption in 9.2% of pregnant women 12 . Current epidemiological studies support these high prevalence rates 13 . In addition to the complete picture of foetal alcohol syndrome, antenatal alcohol use also leads to less apparent but still very relevant problems, such as irritability, reduced adaptability, disinhibition, attention problems and hyperactivity in infancy, toddlerhood and childhood as well as to mental health problems and disorders in adolescence 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 . An impairment of foetal growth due to maternal tobacco smoking during pregnancy is undisputed 17 , 19 . Intrauterine nicotine exposure increases the risk of miscarriage and stillbirth, preterm birth, low birth weight, impaired childhood pulmonary function and attention deficit/hyperactivity symptoms 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 .

Long-term studies and antenatal testosterone exposure

Because of the long follow-up periods, there is only limited direct evidence to date as to which consequences for the child as a result of maternal stress, alcohol consumption and tobacco smoking during pregnancy persist into mid-adulthood and beyond. However, there are indirect indications that antenatal testosterone exposure is involved in lifelong health impairment due to maternal stress as well as alcohol and tobacco use during pregnancy. Biomarkers such as the index/ring finger length ratio (2D:4D ratio) are used to investigate the antenatal testosterone load. It is assumed that the 2D:4D ratio develops in utero and changes only little throughout the rest of life. A smaller 2D:4D ratio stands for a higher antenatal testosterone load and a larger 2D:4D ratio stands for a lower antenatal testosterone load 24 , 25 , 26 .

Our own studies as well as reports from independent groups of researchers suggest that maternal stress as well as alcohol and tobacco use during pregnancy lead to an increased intrauterine testosterone load of the child 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 . At the same time, it is known that elevated antenatal testosterone exposure is associated with illnesses throughout life. In the animal model, antenatal testosterone exposure causes brain changes which persist into adulthood and increases alcohol consumption 31 , 32 . It is therefore not surprising that a high antenatal testosterone load (recorded in humans using biomarkers, such as the 2D:4D ratio, among others) is associated with a whole range of impairments throughout life. These include, for example, a worse overall state of health 33 , behavioural problems in childhood 34 , aggression-induced injuries 35 , 36 , attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder 37 , video game addiction 38 , addictive use of social networks 39 , suicide 40 , 41 , 42 , autism 43 , 44 , prostate carcinoma 45 , primary brain tumours 46 as well as binge drinking and alcohol dependence 29 , 47 , 48 , 49 . Finally, there are initial indications that a smaller 2D:4D ratio as a surrogate marker for a higher antenatal testosterone exposure is also associated with a shorter life expectancy 41 , 49 .

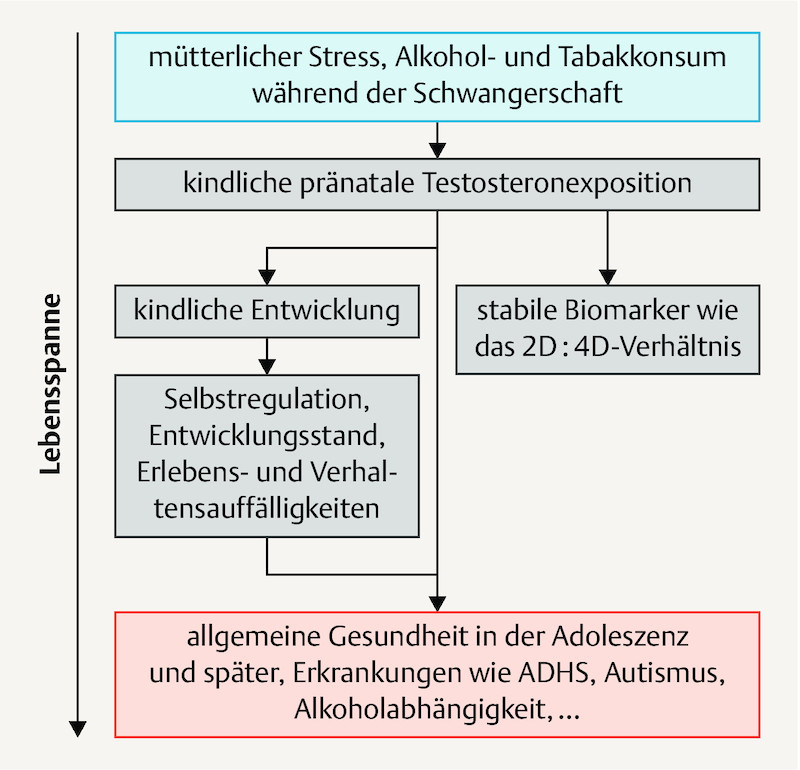

Model on the influence of maternal behaviour during pregnancy on the lifelong health of children

The associations described in the previous paragraphs indicate that maternal stress as well as alcohol and tobacco use during pregnancy increase testosterone exposure in children and thus influence the health of the children for life ( Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Research model on the influence of maternal behaviour during pregnancy on the lifelong health of children. 2D:4D ratio: index/ring finger length ratio.

For this model, there is the above reported indirect evidence. However, it remains unclear whether this involves causal relationships which are actually suitable for establishing preventive approaches. In addition, possible effect sizes of corresponding interventions on later health can only be presumed to date. Therefore, it is intended to conduct the prospective and controlled app-based MINDFUL/PMI (Maternal Health and Infant Development in the Follow-up after Pregnancy and a Mindfulness Intervention) study on mindfulness-oriented reduction of stress and alcohol and tobacco use during pregnancy with the goal of improving the health of mothers and children.

Mindfulness in pregnancy

Mindfulness is an effective method for reducing stress and alcohol and tobacco use. Corresponding training methods promote a mindful attitude, that is, being intentional and nonjudgmental in the present moment, for example. Some studies have already shown that mindfulness training and related methods are suitable for reducing the level of stress and anxiety in pregnancy, also with lasting effects 50 , 51 , 52 , 53 , and improving neonatal health 10 , 54 . A high level of mindfulness also correlates with less alcohol and tobacco use 55 and mindfulness-based methods reduce heavy use 56 . There is evidence of a high level of adherence to mindfulness methods in pregnant women 53 . To increase the availability of the mindfulness programme and to support training at home and integration into daily life, the mindfulness intervention will be established in the form of an app and its effect will be validated.

Maternal health and “Foetal Programming”

“Foetal programming” refers to the imprinting of the foetus in the womb and in the perinatal period through various influences, resulting in the increased appearance of diseases in adolescence and adulthood, such as cardiovascular or metabolic diseases. There is some evidence that epigenetic mechanisms may play an important role here 57 . Children of mothers with preeclampsia have, for example, increased feeding problems, endocrine diseases and metabolic disorders 58 . Likewise, hyperemesis gravidarum can cause neurological developmental delays in the children 59 . In addition, illnesses during pregnancy also have a negative influence on the course of the delivery and post-delivery period. Depressive symptoms in the mother during pregnancy are associated, for example, with an increased rate of Caesarean sections and low birth weight 60 . The development of a hypertensive disease in pregnancy does not only present acute consequences during pregnancy for the mother and child. Following preeclampsia, mothers have an increased long-term risk for arterial hypertension, diabetes and cerebrovascular diseases 61 .

Therefore, in addition to the expected effect of mindfulness on stress and alcohol and tobacco use as well as depressive symptoms in pregnant women, effects on pregnancy, delivery and on epigenetic patterns are also to be investigated in the MINDFUL/PMI study. The use of mindfulness during pregnancy could offer a preventive approach for reducing perinatal and long-term morbidity.

Issue and study objective

Within the scope of the MINDFUL/PMI research project, a mindfulness-oriented app-based programme to reduce stress as well as to reduce alcohol and tobacco use in pregnant women is to be established and the effect of this programme is to be validated using the childhood antenatal testosterone load. The antenatal testosterone exposure will be assessed using the 2D:4D ratio and additional biomarkers in the 1-year-old children. It will also be investigated how the programme affects childrenʼs self-regulation, developmental status and mental health at the age of one year. Different aspects of the course of pregnancy and delivery represent additional exploratory study objectives.

This study is subproject 3 of the “IMAC-Mind” consortium supported by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) (“IMAC-Mind: Improving Mental Health and Reducing Addiction in Childhood and Adolescence through Mindfulness: Mechanisms, Prevention and Treatment, TP3: Reducing stress, alcohol and tobacco use in pregnant women to improve the childrenʼs later mental health”; BMBF funding code of subproject 01GL1745C). In accordance with the funding policy objectives of the BMBF initiative “ Gesund – ein Leben lang ” [Healthy – for life], in this study, a novel concept is being developed for use during the antenatal development phase with the intention of ongoing health promotion and prevention throughout life. Thus, the later risk of disease can already be decreased in the womb and the course can be set for a healthy life. This is an interdisciplinary project which extends over multiple phases of life.

MINDFUL/PMI Study: Summary of the Implementation of the Study

Study design

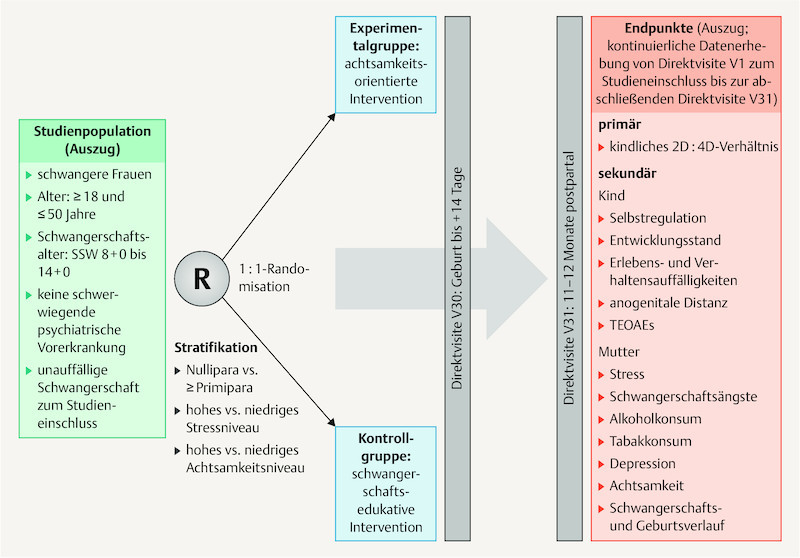

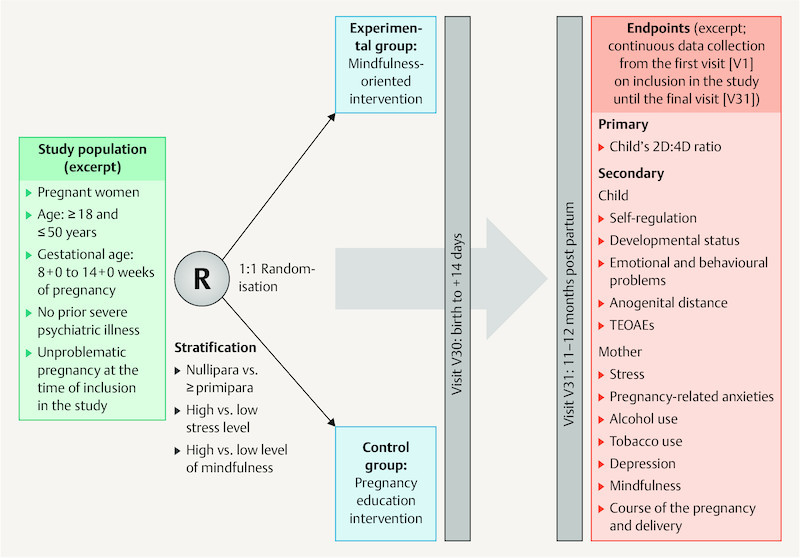

The MINDFUL/PMI study is a monocentre, prospective, controlled and investigator-blinded research project ( Fig. 2 ) at the Universitätsklinikum Erlangen (University Hospital Erlangen). It is planned that 312 pregnant women will participate. They will be randomised into the mindfulness-oriented experimental group or the pregnancy education control group; thus 156 pregnant women are planned for each group.

Fig. 2.

Study design. The level of stress and mindfulness for stratification are recorded using the German versions of the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10) 62 and the Mindful Attention and Awareness Scale (MAAS) 63 . 2D:4D ratio: index/ring finger length ratio, TEOAEs: transient evoked otoacoustic emissions.

Study objective

The primary study objective is the comparison of the 2D:4D ratio in the children (as a marker for intrauterine testosterone exposure) between the two randomisation arms. In the women of the mindfulness-oriented experimental group, a larger 2D:4D ratio of the child at the age of 11 – 12 months (as the measured endpoint) is expected than in the pregnancy education control group. Table 1 shows an excerpt of secondary and exploratory study objectives.

Table 1 Secondary and exploratory study objectives (excerpt).

| TEOAEs: transient evoked otoacoustic emissions | |

| Secondary study objectives | In the mindfulness-oriented experimental group, in comparison to the pregnancy education control group, …

|

| Exploratory study objectives | It shall be demonstrated that participation in the mindfulness-oriented experimental group, in comparison to the pregnancy education control group, …

|

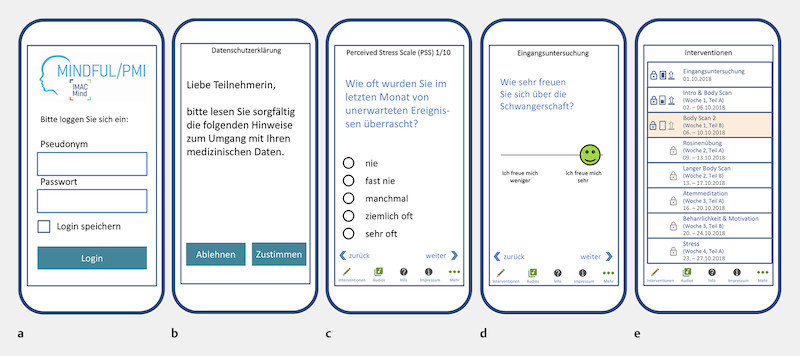

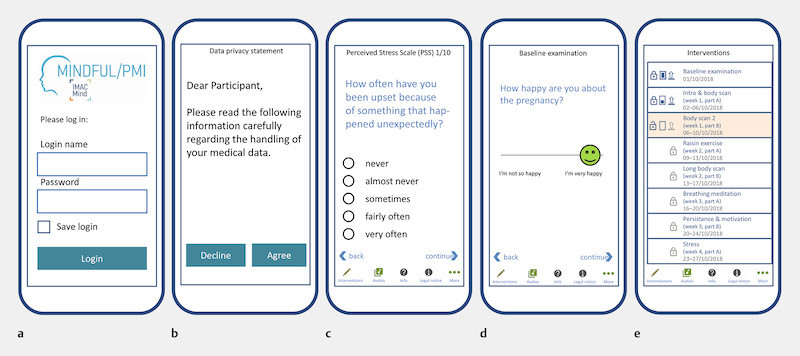

Randomisation

The pregnant women are randomised 1 : 1 into the following groups upon inclusion in the study following stratification (nullipara versus ≥ primipara, high level of stress versus low level of stress (German version of the Perceived Stress Scale [PSS-10] 62 ), high level of mindfulness versus low level of mindfulness (German version of the Mindful Attention and Awareness Scale [MAAS] 63 ) and participate in a programme consisting of app contents (see sample screenshots of the app in Fig. 3 ) and direct contacts. Table 2 shows the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Fig. 3.

Sample screenshots of the app. a Login page of the app, b Information on data privacy, c Example for recording stress via selection of categories with the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10) 62 , d Example of a query using a continuous scale, e Overview of the interventions and audio files to click on and open.

Table 2 Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

| 2D:4D ratio: index/ring finger length ratio | |

| Inclusion criteria | Pregnant women,

|

| Exclusion criteria |

|

Mindfulness-oriented experimental group: The participants receive access to our own custom-made app which was adapted to the needs of pregnant women, with mindfulness exercises based on the Mindfulness-Based-Stress-Reduction (MBSR) programme developed by Jon Kabat-Zinn in the 1980s/90s in Worcester (USA) 64 , 65 , 66 . In three direct contacts, the study subjects are introduced to the topic of mindfulness and receive additional coaching. Via the app, they participate approximately twice per week in an app-based visit during which the mindfulness exercises are taught via audio recordings. These average 10 minutes in length and provide psychoeducation in mindfulness and stress. The audio recordings can be replayed and listened to again. There are various mindful movement meditations, mindful sitting meditations and two body scans of different lengths. The psychoeducation involves mindful attitude in everyday life, the distinction between physical sensations, emotions and thoughts, the tendency of the mind to lose itself in thought and the use of breathing to direct attention to the present moment. The participants are to focus on the topic of mindfulness for 5 – 10 minutes, 2 – 7 times per week.

Pregnancy education control group: The participants in the pregnancy education control group receive also access to a custom-made app. This provides them with audio files with information on pregnancy, delivery, the post-delivery period and breastfeeding, at the same frequency and duration as well as with the same layout as in the mindfulness-oriented experimental group (audio recordings lasting an average of 10 minutes approximately twice per week). Three direct contacts also take place in the control group. General information on the development of the embryo and foetus at certain time points in the pregnancy as well as on the Mutterpass (pregnancy record), the regular examinations as part of antenatal care, on diseases of pregnancy and the additional possible examinations (such as first trimester screening, cfDNA, organ screening, oral glucose tolerance test, screening for Group B streptococci) is given. In addition, the topics of nutrition, sports and habits when travelling are addressed and the fields of mode of delivery and pain therapy during delivery are explained. Finally, information on breastfeeding and the post-delivery period is provided.

Entire duration of the study

The entire duration of the study comprises the preparation phase with a start in the first quarter of 2016, the active study phase with inclusion of pregnant women expected as of the fourth quarter of 2018 until the second quarter of 2020, the active study phase with the examination of the children from the first quarter of 2020 until the fourth quarter of 2021 and the data analysis, evaluation and post-processing in the fourth quarter of 2021 and the first quarter of 2022.

Individual course of the study and measurement methods

The study consists of a 15-week programme part with three direct visits during pregnancy and two postpartum direct visits to record the study endpoints. These are known as visits V1, V15, V29, V30 and V31 ( Table 3 ). In addition, the participants in the mindfulness-oriented experimental group are offered mindfulness exercises as part of the app approximately twice weekly. These are to be performed by the participants 2 – 7 times per week. The participants of the pregnancy education control group similarly receive information about pregnancy and delivery via the app approximately twice per week. The visits A2 to A14 and A16 to A28 provided via the app take place between V1 and V15 and between V15 and V29. The participants in the mindfulness-oriented experimental group are asked every week via the app how long they exercised mindfulness in the prior week. In addition, the heart rate variability is measured in a subgroup of the pregnant women each week using a smartphone camera app 67 .

Table 3 Study procedures (excerpt).

| Visits | Screening | V1 | V15 | V29 | V30 | V31 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time | Day 1 (8th-14th WOP) | Day 53 ± 7 days | Day 105 ± 7 days | Delivery to + 14 days | 11 – 12 months post partum | |

| The table shows the direct visits V1, V15, V29, V30 and V31 with an excerpt of the study procedures and the planned survey instruments. Mother: Stress: German version of the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10) 62 ; alcohol use: adapted version of the Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (AUDIT-C) 68 and nicotine use: adapted version of a smoking questionnaire from the Robert Koch Institute Berlin 69 , in addition, Timeline Followback survey modified for pregnancy 70 ; mindfulness: German version of the Mindful Attention and Awareness Scale (MAAS) 63 ; depression: German version of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) 71 , 72 ; pregnancy-related anxieties: Pregnancy-Related Anxiety Questionnaire (PRAQ-R2) 73 . Child: Self-regulation: Infant Behavior Questionnaire Revised (IBQ-R) 74 , 75 ; developmental status: Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development – Third Edition 76 ; emotional and behavioural problems: Child-Behavior Checklist (CBCL 1.5 – 5.0) 77 . WOP: week of pregnancy | ||||||

| Inclusion/exclusion criteria | X | X | ||||

| Written informed consent | X | |||||

| Randomisation | X | |||||

| Recording of | ||||||

|

X | |||||

|

X | X | X | X | X | |

|

X | X | X | X | X | |

|

X | X | X | X | X | |

|

X | X | ||||

|

X | X | X | |||

| Direct intervention | X | X | X | |||

| Measurement of ethyl glucuronide in hair and meconium | X | X | ||||

| Blood sample – mother | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Measurement of cotinine/cortisol in maternal hair | X | X | ||||

| Sampling of placental tissue and umbilical cord blood | X | |||||

| Oral mucosa swab in the child | X | X | ||||

| Biomarker for prenatal testosterone exposure | X | X | ||||

| Maternal microbiome (stool sample) | X | |||||

| Self-regulation, developmental status and emotional and behavioural problems of the child | X | |||||

Statistical considerations and sample size calculation

The primary endpoint, the 2D:4D ratio, is evaluated using a multiple linear regression model with the predictors of study arm, sex of the child (female, male) and further predictors. The sex of the child is taken into account since differences between boys and girls are expected. Study participants with missing target variable values are excluded. Missing predictor values are imputed based on the available values of the other study participants. The analysis of the secondary study objectives is performed analogously. There are no interim analyses planned.

Assuming a standardised group difference of Cohenʼs d = 0.35 for the primary endpoint, the sample size estimate yields 260 study participants (significance level 0.05, power 0.80). A presumed failure rate of 15% yields a final sample size of 312 participants. It is expected that the mindfulness-oriented experimental group, in comparison to the pregnancy education control group, will reach a Cohenʼs d = 0.40 for self-regulation in children (secondary study objective). In this case, the statistical power for the secondary study objective is 89%.

Ethical aspects and trial registration

The study project has been approved by the Ethics Committee of the Friedrich-Alexander University Erlangen-Nürnberg (FAU) (application number: 58_18 B). The study is conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (2013 in Fortaleza, Brazil, revised edition) and the ICH-GCP guidelines (German Register of Clinical Trials; www.drks.de ; DRKS00014920).

Acknowledgements

With the public funded research project IMAC-Mind: Improving Mental Health and Reducing Addiction in Childhood and Adolescence through Mindfulness: Mechanisms, Prevention and Treatment (2018 – 2022, 01GL1745C), the Federal Ministry of Education and Research contributes to improving the prevention and treatment of children and adolescents with substance use disorders and associated mental disorders. The project coordination is realised by the German Center of Addiction Research in Childhood and Adolescence at the University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf. For more information please visit our homepage www.IMAC-Mind.de . In addition, we thank interActive Systems GmbH, Berlin, for permission to publish the sample app screenshots.

Danksagung

Mit der Förderung des Forschungsverbundes IMAC-Mind: Verbesserung der psychischen Gesundheit und Verringerung von Suchtgefahr im Kindes- und Jugendalter durch Achtsamkeit: Mechanismen, Prävention und Behandlung (2018 – 2022; 01GL1745C) leistet das Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung einen Beitrag, die Prävention und therapeutische Versorgung von Kindern und Jugendlichen mit Suchtstörungen und weiteren damit verbundenen psychischen Störungen zu verbessern. Die Projektkoordination erfolgt durch das Deutsche Zentrum für Suchtfragen des Kindes- und Jugendalters am Universitätsklinikum Hamburg-Eppendorf. Für ausführliche Informationen siehe www.IMAC-Mind.de . Außerdem danken wir der Firma interActive Systems GmbH, Berlin, für die Erlaubnis zur Publikation der exemplarischen Screenshots der App.

Conflict of Interest/Interessenkonflikt The authors quote some of their own publications on which this work and the idea of the study are based./ Die Autoren zitieren einige eigene Publikationen, die dieser Arbeit und der Studienidee zugrunde liegen.

The authors contributed equally.

Die Autoren haben gleichermaßen beigetragen.

References/Literatur

- 1.Stone S L, Diop H, Declercq E. Stressful events during pregnancy and postpartum depressive symptoms. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2015;24:384–393. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2014.4857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stein A, Pearson R M, Goodman S H. Effects of perinatal mental disorders on the fetus and child. Lancet. 2014;384:1800–1819. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61277-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lilliecreutz C, Larén J, Sydsjö G. Effect of maternal stress during pregnancy on the risk for preterm birth. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016;16:5. doi: 10.1186/s12884-015-0775-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baibazarova E, van de Beek C, Cohen-Kettenis P T. Influence of prenatal maternal stress, maternal plasma cortisol and cortisol in the amniotic fluid on birth outcomes and child temperament at 3 months. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2013;38:907–915. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2012.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Glover V. Prenatal stress and its effects on the fetus and the child: possible underlying biological mechanisms. Adv Neurobiol. 2015;10:269–283. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-1372-5_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Talge N M, Neal C, Glover V. Antenatal maternal stress and long-term effects on child neurodevelopment: how and why? J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2007;48:245–261. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01714.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davis E P, Glynn L M, Schetter C D. Prenatal exposure to maternal depression and cortisol influences infant temperament. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;46:737–746. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e318047b775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nolvi S, Karlsson L, Bridgett D J. Maternal prenatal stress and infant emotional reactivity six months postpartum. J Affect Disord. 2016;199:163–170. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huizink A C, de Medina P GR, Mulder E JH. Psychological measures of prenatal stress as predictors of infant temperament. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002;41:1078–1085. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200209000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chan K P. Prenatal meditation influences infant behaviors. Infant Behav Dev. 2014;37:556–561. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2014.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van den Heuvel M I, Johannes M A, Henrichs J. Maternal mindfulness during pregnancy and infant socio-emotional development and temperament: the mediating role of maternal anxiety. Early Hum Dev. 2015;91:103–108. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2014.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bergmann K E, Bergmann R L, Ellert U. Perinatale Einflussfaktoren auf die spätere Gesundheit. Bundesgesundheitsbl Gesundheitsforsch Gesundheitsschutz. 2007;50:670–676. doi: 10.1007/s00103-007-0228-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Popova S, Lange S, Probst C. Estimation of national, regional, and global prevalence of alcohol use during pregnancy and fetal alcohol syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2017;5:e290–e299. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30021-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alvik A, Torgersen A M, Aalen O O. Binge alcohol exposure once a week in early pregnancy predicts temperament and sleeping problems in the infant. Early Hum Dev. 2011;87:827–833. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2011.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nulman I, Rovet J, Kennedy D. Binge alcohol consumption by non-alcohol-dependent women during pregnancy affects child behaviour, but not general intellectual functioning; a prospective controlled study. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2004;7:173–181. doi: 10.1007/s00737-004-0055-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burger P H, Goecke T W, Fasching P A. [How does maternal alcohol consumption during pregnancy affect the development of attention deficit/hyperactivity syndrome in the child] Fortschr Neurol Psychiatr. 2011;79:500–506. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1273360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Polańska K, Jurewicz J, Hanke W. Smoking and alcohol drinking during pregnancy as the risk factors for poor child neurodevelopment – a review of epidemiological studies. Int J Occup Med Environ Health. 2015;28:419–443. doi: 10.13075/ijomeh.1896.00424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Flak A L, Su S, Bertrand J. The association of mild, moderate, and binge prenatal alcohol exposure and child neuropsychological outcomes: a meta-analysis. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2014;38:214–226. doi: 10.1111/acer.12214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abraham M, Alramadhan S, Iniguez C. A systematic review of maternal smoking during pregnancy and fetal measurements with meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0170946. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0170946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McEvoy C T, Spindel E R. Pulmonary effects of maternal smoking on the fetus and child: effects on lung development, respiratory morbidities, and life long lung health. Paediatr Respir Rev. 2017;21:27–33. doi: 10.1016/j.prrv.2016.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Holz N E, Boecker R, Baumeister S. Effect of prenatal exposure to tobacco smoke on inhibitory control: neuroimaging results from a 25-year prospective study. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71:786–796. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brook J S, Brook D W, Whiteman M. The influence of maternal smoking during pregnancy on the toddlerʼs negativity. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2000;154:381–385. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.154.4.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wiebe S A, Fang H, Johnson C. Determining the impact of prenatal tobacco exposure on self-regulation at 6 months. Dev Psychol. 2014;50:1746–1756. doi: 10.1037/a0035904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Berenbaum S A, Bryk K K, Nowak N. Fingers as a marker of prenatal androgen exposure. Endocrinology. 2009;150:5119–5124. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-0774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zheng Z, Cohn M J. Developmental basis of sexually dimorphic digit ratios. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:16289–16294. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1108312108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Talarovičová A, Kršková L, Blažeková J. Testosterone enhancement during pregnancy influences the 2D:4D ratio and open field motor activity of rat siblings in adulthood. Horm Behav. 2009;55:235–239. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2008.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lilley T, Laaksonen T, Huitu O. Maternal corticosterone but not testosterone level is associated with the ratio of second-to-fourth digit length (2D:4D) in field vole offspring (Microtus agrestis) Physiol Behav. 2010;99:433–437. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2009.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rizwan S, Manning J T, Brabin B J. Maternal smoking during pregnancy and possible effects of in utero testosterone: evidence from the 2D:4D finger length ratio. Early Hum Dev. 2007;83:87–90. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2006.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lenz B, Mühle C, Braun B. Prenatal and adult androgen activities in alcohol dependence. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2017;136:96–107. doi: 10.1111/acps.12725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barrett E S, Swan S H. Stress and androgen activity during fetal development. Endocrinology. 2015;156:3435–3441. doi: 10.1210/en.2015-1335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huber S E, Zoicas I, Reichel M. Prenatal androgen receptor activation determines adult alcohol and water drinking in a sex-specific way. Addict Biol. 2018;23:904–920. doi: 10.1111/adb.12540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brown E CZ, Steadman C J, Lee T M. Sex differences and effects of prenatal exposure to excess testosterone on ventral tegmental area dopamine neurons in adult sheep. Eur J Neurosci. 2015;41:1157–1166. doi: 10.1111/ejn.12871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rapoza K A. Does life stress moderate/mediate the relationship between finger length ratio (2D4D), depression and physical health? Pers Indiv Differ. 2017;113:74–80. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Eichler A, Heinrich H, Moll G H. Digit ratio (2D:4D) and behavioral symptoms in primary-school aged boys. Early Hum Dev. 2018;119:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2018.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Joyce C W, Kelly J C, Chan J C. Second to fourth digit ratio confirms aggressive tendencies in patients with boxers fractures. Injury. 2013;44:1636–1639. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2013.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.OʼBriain D E, Dawson P H, Kelly J C. Assessment of the 2D:4D ratio in aggression-related injuries in children attending a paediatric emergency department. Ir J Med Sci. 2017;186:441–445. doi: 10.1007/s11845-016-1524-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Martel M M, Gobrogge K L, Breedlove S M. Masculinized finger-length ratios of boys, but not girls, are associated with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Behav Neurosci. 2008;122:273–281. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.122.2.273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kornhuber J, Zenses E M, Lenz B. Low 2D:4D values are associated with video game addiction. PLoS One. 2013;8:e79539. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0079539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bouna-Pyrrou P, Mühle C, Kornhuber J. Internet gaming disorder, social network disorder and laterality: handedness relates to pathological use of social networks. J Neural Transm (Vienna) 2015;122:1187–1196. doi: 10.1007/s00702-014-1361-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lenz B, Thiem D, Bouna-Pyrrou P. Low digit ratio (2D:4D) in male suicide victims. J Neural Transm (Vienna) 2016;123:1499–1503. doi: 10.1007/s00702-016-1608-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lenz B, Kornhuber J. Cross-national gender variations of digit ratio (2D:4D) correlate with life expectancy, suicide rate, and other causes of death. J Neural Transm (Vienna) 2018;125:239–246. doi: 10.1007/s00702-017-1815-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lenz B, Röther M, Bouna-Pyrrou P. The androgen model of suicide completion. Prog Neurobiol. 2018 doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2018.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.et al. . Masuya Y, Okamoto Y, Inohara K. Sex-different abnormalities in the right second to fourth digit ratio in Japanese individuals with autism spectrum disorders. Mol Autism. 2015;6:34. doi: 10.1186/s13229-015-0028-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Al-Zaid F S, Alhader A A, Al-Ayadhi L Y. The second to fourth digit ratio (2D:4D) in Saudi boys with autism: A potential screening tool. Early Hum Dev. 2015;91:413–415. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2015.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mendes P HC, Martelli D RB, de Melo Costa S. Comparison of digit ratio (2D:4D) between Brazilian men with and without prostate cancer. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2016;19:107–110. doi: 10.1038/pcan.2015.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bunevicius A, Tamasauskas S, Deltuva V P. Digit ratio (2D:4D) in primary brain tumor patients: A case-control study. Early Hum Dev. 2016;103:205–208. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2016.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Han C, Bae H, Lee Y S. The ratio of 2nd to 4th digit length in Korean alcohol-dependent patients. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci. 2016;14:148–152. doi: 10.9758/cpn.2016.14.2.148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kornhuber J, Erhard G, Lenz B. Low digit ratio 2D:4D in alcohol dependent patients. PLoS One. 2011;6:e19332. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lenz B, Bouna-Pyrrou P, Mühle C. Low digit ratio (2D:4D) and late pubertal onset indicate prenatal hyperandrogenziation in alcohol binge drinking. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2018;86:370–378. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2018.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dunn C, Hanieh E, Roberts R. Mindful pregnancy and childbirth: effects of a mindfulness-based intervention on womenʼs psychological distress and well-being in the perinatal period. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2012;15:139–143. doi: 10.1007/s00737-012-0264-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Muthukrishnan S, Jain R, Kohli S. Effect of mindfulness meditation on perceived stress scores and autonomic function tests of pregnant Indian women. J Clin Diagn Res. 2016;10:CC05–CC08. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2016/16463.7679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Guardino C M, Dunkel Schetter C, Bower J E. Randomised controlled pilot trial of mindfulness training for stress reduction during pregnancy. Psychol Health. 2014;29:334–349. doi: 10.1080/08870446.2013.852670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Goodman J H, Guarino A, Chenausky K. CALM Pregnancy: results of a pilot study of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for perinatal anxiety. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2014;17:373–387. doi: 10.1007/s00737-013-0402-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zilcha-Mano S, Langer E. Mindful attention to variability intervention and successful pregnancy outcomes. J Clin Psychol. 2016;72:897–907. doi: 10.1002/jclp.22294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Karyadi K A, VanderVeen J D, Cyders M A. A meta-analysis of the relationship between trait mindfulness and substance use behaviors. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;143:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cavicchioli M, Movalli M, Maffei C. The clinical efficacy of mindfulness-based treatments for alcohol and drugs use disorders: a meta-analytic review of randomized and nonrandomized controlled trials. Eur Addict Res. 2018;24:137–162. doi: 10.1159/000490762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Arabin B, Baschat A A. Pregnancy: an underutilized window of opportunity to improve long-term maternal and infant health-an appeal for continuous family care and interdisciplinary communication. Front Pediatr. 2017;5:69. doi: 10.3389/fped.2017.00069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wu C S, Nohr E A, Bech B H. Health of children born to mothers who had preeclampsia: a population-based cohort study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;201:2690–2.69E12. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.06.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fejzo M S, Magtira A, Schoenberg F P. Neurodevelopmental delay in children exposed in utero to hyperemesis gravidarum. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2015;189:79–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2015.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bartel S, Costa S D, Kropf S. Pregnancy outcomes in maternal neuropsychiatric illness and substance abuse. Geburtsh Frauenheilk. 2017;77:1189–1199. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-120920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Auger N, Fraser W D, Schnitzer M. Recurrent pre-eclampsia and subsequent cardiovascular risk. Heart. 2017;103:235–243. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2016-309671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Klein E M, Brähler E, Dreier M. The German version of the Perceived Stress Scale – psychometric characteristics in a representative German community sample. BMC Psychiatry. 2016;16:159. doi: 10.1186/s12888-016-0875-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Michalak J, Heidenreich T, Ströhle G. German version of the Mindful Attention and Awareness Scale (MAAS) – psychometric features of a mindfulness questionnaire. Z Klin Psychol Psychother. 2008;37:200–208. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kabat-Zinn J. An outpatient program in behavioral medicine for chronic pain patients based on the practice of mindfulness meditation: theoretical considerations and preliminary results. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1982;4:33–47. doi: 10.1016/0163-8343(82)90026-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kabat-Zinn J, Lipworth L, Burney R. The clinical use of mindfulness meditation for the self-regulation of chronic pain. J Behav Med. 1985;8:163–190. doi: 10.1007/BF00845519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kabat-Zinn J, Massion A O, Kristeller J. Effectiveness of a meditation-based stress reduction program in the treatment of anxiety disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 1992;149:936–943. doi: 10.1176/ajp.149.7.936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Plews D J, Scott B, Altini M. Comparison of heart-rate-variability recording with smartphone photoplethysmography, polar H7 chest strap, and electrocardiography. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2017;12:1324–1328. doi: 10.1123/ijspp.2016-0668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.McDonell MB et al. for the Ambulatory Care Quality Improvement Project (ACQUIP) . Bush K, Kivlahan D R. The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions (AUDIT-C): an effective brief screening test for problem drinking. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:1789–1795. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.16.1789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Latza U, Hoffmann E, Terschüren C. Berlin: Robert Koch-Institut; 2005. Erhebung, Quantifizierung und Analyse der Rauchexposition in epidemiologischen Studien. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sobell L C, Brown J, Leo G I. The reliability of the Alcohol Timeline Followback when administered by telephone and by computer. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1996;42:49–54. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(96)01263-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cox J L, Chapman G, Murray D. Validation of the Edinburgh postnatal depression scale (EPDS) in non-postnatal women. J Affect Disord. 1996;39:185–189. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(96)00008-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bergant A M, Nguyen T, Heim K. [German language version and validation of the Edinburgh postnatal depression scale] Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 1998;123:35–40. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1023895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Huizink A C, Delforterie M J, Scheinin N M. Adaption of pregnancy anxiety questionnaire-revised for all pregnant women regardless of parity: PRAQ-R2. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2016;19:125–132. doi: 10.1007/s00737-015-0531-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gartstein M A, Rothbart M K. Studying infant temperament via the Revised Infant Behavior Questionnaire. Infant Behav Dev. 2003;26:64–86. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Vonderlin E, Ropeter A, Pauen S. Assessment of temperament with the Infant Behavior Questionnaire Revised (IBQ-R) – the psychometric properties of a German version. Z Kinder-Jugendpsychiatr Psychother. 2012;40:307–314. doi: 10.1024/1422-4917/a000187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bayley N. Frankfurt a. M.: Pearson Assessment & Information GmbH; 2014. Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development – Third Edition. German adaptation: Reuner G, Rosenkranz J. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Achenbach T M, Ruffle T M. The Child Behavior Checklist and related forms for assessing behavioral/emotional problems and competencies. Pediatr Rev. 2000;21:265–271. doi: 10.1542/pir.21-8-265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]