Abstract

Given the demographic trends toward a considerably longer life expectancy, the percentage of elderly patients with prostate cancer will increase further in the upcoming decades. Therefore, the question arises, should patients ≥75 years old be offered radical prostatectomy and under which circumstances? For treatment decision-making, life expectancy is more important than biological age. As a result, a patient's health and mental status has to be determined and radical treatment should only be offered to those who are fit. As perioperative morbidity and mortality in these patients is increased relative to younger patients, patient selection according to comorbidities is a key issue that needs to be addressed. It is known from the literature that elderly men show notably worse tumor characteristics, leading to worse oncologic outcomes after treatment. Moreover, elderly patients also demonstrate worse postoperative recovery of continence and erectile function. As the absolute rates of both oncological and functional outcomes are still very reasonable in patients ≥75 years, a radical prostatectomy can be offered to highly selected and healthy elderly patients. Nevertheless, patients clearly need to be informed about the worse outcomes and higher perioperative risks compared to younger patients.

Keywords: age, functional outcome, oncological outcome, prostate cancer, radical prostatectomy

INTRODUCTION

Prostate cancer (PCa) is the most frequent cancer among males in developed countries and a leading cause of cancer deaths.1,2 Due to the increasing life expectancy of men worldwide, the percentage of elderly patients who are more likely to develop PCa will increase further within the next few decades. This will lead to an intensified discussion about age limits for radical treatment in patients with PCa.3,4 The recently updated International Society of Geriatric Oncology (SIOG) guidelines on PCa in men aged >70 years advise a mandatory health screening using the G-8 tool and mini-COG™,5,6 and to offer fit elderly men (e.g., with a G-8 of >14 points) the same treatment options as younger men, as patients should not be treated according to their biologic age but according to their individual health status.7 When considering elderly patients for radical prostatectomy (RP), life expectancy (LE), and perioperative morbidity and mortality, oncologic and functional outcomes are important factors to consider. Despite current studies reporting reasonable oncologic and functional outcomes, patients 75 years or older with PCa are still subject to undertreatment.8,9,10 The aim of this review is to summarize the literature on RP in men older than 75 years and to give an overview of the risks, benefits, and proper selection in this special cohort of patients.

A literature review was performed using PubMed and Medline databases. Electronic articles published ahead of print were also included. The search focused on articles in English and was completed using the following keywords: radical prostatectomy, elderly patients, outcomes, age, prostate cancer, and ≥75 years.

IMPORTANT SELECTION CRITERIA FOR RP IN THE ELDERLY PATIENTS

LE and the risk of dying from noncuratively treated PCa

Present guidelines for the treatment of PCa request a suitable remaining LE for patients undergoing RP, but do not have a certain age limit (European Association of Urology [EAU] guideline: LE >10 years; National Comprehensive Cancer Network [NCCN] guideline: LE 10-20 years depending on risk group; American Urological Association [AUA] guideline: a “reasonable” LE).11,12,13 Men aged 75 years in developed countries have an additional LE of 10 years,14,15,16 which increases to 15 years when looking at the top 25th percentile of the healthiest men.17 As a result, more elderly men are suitable for RP according to current guidelines. Thereby, a health screening in all patients >70 years old using the G-8 tool5 and mini-COGTM6 has been suggested.7 RP should only be offered to fit elderly men (e.g., with an G-8 score of >14 points). Screening with G-8 can also help to decide whether further Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (CGA) is indicated to identify potentially reversible conditions. Moreover, it is known that for poorly differentiated PCa, potentially curative therapy can lead to an increase not only in LE but also quality-adjusted LE in patients up to the age of 80 years.18 Rider et al.19 showed 10-year cancer-specific mortality (CSM) rates among men older than 75 years with intermediate- or high-risk PCa treated with noncurative intent to be 14.9% and 29.4%, respectively, while 10-year other cause mortality rates (OCM) constantly decreased to approximately 50% with lower Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI). Populations undergoing RP and noncurative treatment should still only be compared with great caution since patients above 75 years of age undergoing RP are a highly selected population.

For patients with age ≥75 years with locally advanced tumors, cancer-specific mortality without curative treatment is even higher (up to 40% after 8 years).20 Nevertheless, some authors report that only 10% of men with high-risk PCa between 75 and 80 years of age and a CCI of 0 receive radical treatment despite a 52% probability of a 10-year LE.21 This undertreatment of elderly patients might be due in part to the fact that physicians frequently underestimate 10-year LE.22,23,24,25,26 Moreover, some urologists still avoid definitive treatment for localized PCa in elderly patients because of age alone.27,28 In an analysis of a large cohort of patients undergoing RP, after age, CCI was the factor with the strongest influence on OCM in elderly patients.29 Nevertheless, age alone should not be a contraindication for RP in patients 75 years or older, especially in men with high-risk disease and no other relevant comorbidities, as both LE and risk of death due to a noncuratively treated PCa are high in these patients. Therefore, an evaluation of LE by analyzing comorbidities (e.g., using CCI) should be mandatory when selecting elderly patients for surgery to identify particularly healthy individuals for RP.30,31,32

Tumor characteristics

It is known that elderly patients diagnosed with PCa show more aggressive and locally advanced tumors.27,28,33,34,35,36,37 Patients 75 years or older undergoing RP have high-risk disease in 25% of cases and nonorgan-confined tumor in up to 50% of cases in the final pathology.36 It is questionable if these advanced tumor characteristics in elderly patients are solely attributable to the natural history of PCa rather than to patient selection. Certainly, patients older than 75 years are less likely to undergo PSA testing and biopsy and will, also due to a higher risk of perioperative mortality and morbidity (see below), not routinely undergo RP in cases with a very low risk of disease progression. Radical treatment is often avoided in patients above the age of 75 years despite harboring high-risk disease.21

Perioperative morbidity and mortality

Perioperative morbidity and mortality was often identified as a potential reason against performing RP in elderly patients in the past.38 Alibhai et al.39 analyzed data from 11 010 men who underwent surgery in Ontario, Canada, between 1990 and 1999. Overall, the risk of death was 0.48% and the risk of complications within 30 days of RP was 20.4%. Nevertheless, although age was still associated with an increased risk of 30-day mortality and medical complications after controlling for comorbidities, the absolute numbers were still favorable in elderly patients (0.66% risk of death, 26.9% risk of complications for men aged 70–79 years). A similar study by Begg et al.40 assessing the perioperative morbidity and mortality rates among 11 522 men undergoing RP in the United States between 1992 and 1996 showed the risk of at least one postoperative complication to be 28%, 31%, and 35% and the risk of 30-day mortality to be 0.4%, 0.5%, and 0.9% for men aged 65–69 years, 70–74 years, and 75 years and older, respectively. An increase in 30-day mortality with increasing CCI was also seen (0.3%, 0.8% and 1.6% for CCI of 0, 1 and 2 or above, respectively). When comparing RP with external beam radiation therapy (EBRT), differences in perioperative mortality favoring EBRT increased with higher age and CCI. For example, in patients above 75 years, differences in 30-day (90-day) mortality between RP and EBRT ranged from 0.4% to 1.1% (2.1%–3.2%), depending on their CCI.41 However, both radiotherapy and androgen deprivation therapy have significant side effects, particularly in older men (gastrointestinal and genitourinary for radiation therapy, cardiovascular events for androgen deprivation therapy), which should not be underestimated in treatment decision making.42,43

Patients 75 years or older with higher CCI do have an increased risk of perioperative morbidity and mortality as compared to younger and healthier men and should be counselled about this fact prior to RP.

Oncologic outcomes

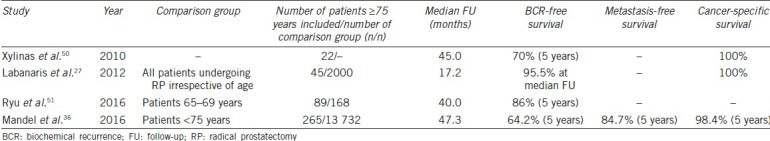

While the body of literature analyzing oncologic outcomes after RP in patients above the age of 65 and 70 years is large,34,44,45,46,47,48,49 only a few studies specifically focus on patients ≥75 years (Table 1).27,36,50,51 Due to small sample sizes and short follow-up in some studies, oncologic results (biochemical recurrence [BCR], metastasis-free and cancer-specific survival [CSS]) are incompletely reported with only limited comparability.

Table 1.

Oncologic outcome in patients ≥75 years undergoing radical prostatectomy

Labanaris et al.27 published results of 45 patients ≥75 years undergoing robotic-assisted laparoscopic RP. After a median follow-up of 17.2 months, no disease-specific deaths were recorded and 95.5% were free of biochemical progression. The reported oncological outcomes were limited by short median follow-up and small sample size. Another study by Xylinas et al.50 analyzed 22 patients who underwent laparoscopic RP with a median follow-up of 45.0 months. No patient died within the follow-up and 5-year BCR-free survival was around 70%. Ryu et al.51 published their results comparing 89 patients ≥75 years to 168 younger patients between 65 and 69 years with a median follow-up of 40.0 months. After 5 years, BCR-free survival in the group of elderly patients was approximately 86% and not statistically different to younger patients (approximately 87.5%). No information on metastasis-free survival and CSS was provided. The largest study to date analyzing the oncologic outcome of patients ≥75 years was published by our group. We compared 265 patients ≥75 years to 13 732 patients <75 years of age with a median follow-up of 47.3 months.36 Five-year BCR-free, metastasis-free survival, CSS, and overall survival (OS) rates were 64.2%, 84.7%, 98.4%, and 91.3% for the older group and 76.9%, 96.2%, 99.0%, and 96.2% for the younger patients, respectively. The lower 5-year BCR-free survival rates, especially compared to the data from Ryu et al.,51 can be attributed to the lower rate of organ-confined tumors in the cohort of patients ≥75 years of age in our study (54.2% vs 64.0%). In univariable analysis, older patients were more likely to develop BCR (HR: 1.74, P = 0.001) and metastases (HR: 3.14, P = 0.002).36 After adjusting for adverse tumor characteristics of older patents in multivariable analysis, the effect of age remained significant for both BCR (HR: 2.13, 95% CI: 1.53–2.95, P < 0.001) and metastases (HR: 1.91, 95% CI: 1.03–3.53, P = 0.040). Age at the time of RP did not influence CSS in univariable or multivariable regression (both P > 0.05).

Recently published data for men ≥75 years with initial conservative treatment for newly diagnosed localized PCa reported CSM rates after 15-year of 10%–27%, depending on Gleason score.52 Comparing these survival rates with the ones after RP, elderly patients might benefit from RP compared to conservative treatment, especially when harboring high-risk PCa despite their worse results after RP compared to younger patients.53 Therefore, from an oncologic standpoint, age alone should not be a contraindication for RP in carefully selected men ≥75 years. Good patient selection in elderly patients is currently already reflected by low other cause mortality in these patients in large RP series.29

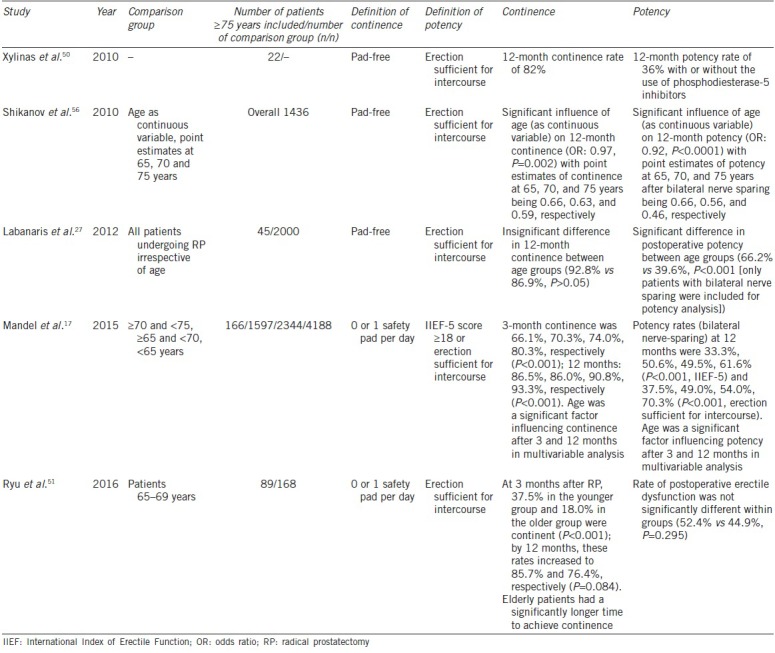

Functional outcomes

There is evidence in literature that increasing age is a risk factor for worse functional outcome after RP.17,27,33,34,50,51,54,55,56,57 An overview of studies reporting functional outcomes after RP in patients ≥75 years is depicted in Table 2. Most current studies defined continence as the use of no pads and an erection sufficient for intercourse as potent. Labanaris et al.27 reviewed the records of 2000 patients who underwent RP, in whom 45 patients were 75 years or older. While the authors showed no significant difference in achieving continence after 12 months (92.8% younger patients vs 86.9% elderly patients, P > 0.05), the difference between age groups in postoperative potency in men with bilateral nerve sparing (66.2% vs 39.6%, P < 0.001) was statistically significant. No multivariable analyses were performed. Xylinas et al.50 analyzed the functional outcomes of 22 men ≥75 years after RP and reported very similar rates (12-month continence rate of 82% and 12-month potency rate of 36% with or without the use of phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors). A comparison to functional outcomes of younger patients was not provided by the authors. Ryu et al.51 compared their results of 89 patients ≥75 years to 168 younger patients between 65 and 69 years. Continence was defined as the use of ≤1 safety pad per 24 h. At 3 months after RP, 37.5% of younger vs 18.0% of elderly patients were continent. After 12 months, the continence rates increased and were not significantly different between younger and older patients (85.7% vs 76.4%, P = 0.084). However, in multivariable analyses, older patients needed longer time to achieve continence after RP (P = 0.016). Concerning potency, the authors reported no significant difference in the rate of postoperative erectile dysfunction (ED) between the two groups (52.4% vs 44.9%, P = 0.295). In the largest cohort of patients ≥75 years so far, we analyzed the functional outcome of 166 patients ≥75 years and compared them to patients ≥70 and <75 years (n = 1597), ≥65 and <70 years (n = 2344), and <65 years (n = 4188).17 Similar to Ryu et al.,51 patients were considered continent if ≤1 safety pad per 24 h was used. After 3 and 12 months, elderly patients showed reasonable continence rates; nevertheless, these rates were lower compared to younger patients (3-month continence: 66.1%, 70.3%, 74.0%, and 80.3%, P < 0.001; 12-month continence: 86.5%, 86.0%, 90.8%, and 93.3%, P < 0.001; for patients ≥75, ≥70 and <75, ≥65 and <70, <65 years, respectively). The respective potency rates after 12 months in patients with bilateral nerve sparing procedure were 37.5%, 49.0%, 54.0%, and 70.3% (P < 0.001) if erection sufficient for intercourse was used as a definition for potency. If an international index of erectile function (IIEF-5) score ≥18 was used as the definition, 33.3%, 50.6%, 49.5%, and 61.6% (P < 0.001) achieved potency, respectively. Age was a significant factor influencing recovery of continence and potency after 3 and 12 months in multivariable analysis. Both continence and potency can further improve after the threshold of 12 months (up to 50% of patients who suffer from incontinence and 36% of patients with ED after 12 months recover within the next 24 months). Age remains a significant factor influencing late recovery of functional outcome.58

Table 2.

Functional outcome in patients ≥75 years undergoing radical prostatectomy

Although absolute chances for recovery of continence and potency in patients ≥75 years at RP are reasonable, older age has a significant adverse effect. As ED becomes less important to patients with increasing age, and baseline ED is very common in patients ≥75 years without RP (up to 77%), the comparably low rates of potency after RP in patients ≥75 years may not be seen as a too strong argument against surgery.59,60 Nevertheless, elderly patients clearly need to be informed about the increased risk of incontinence and ED after RP.

CONCLUSIONS

Biological age ≥75 years alone should not be a strict contraindication for RP, as patients currently aged 75 years have an LE of >10 years and show reasonable functional and oncologic outcomes. However, a health screening in all elderly patients before RP is mandatory. Elderly patients with PCa harbor notably worse tumor characteristics. Older patients, particularly those with high-risk PCa, still benefit from radical treatment. Importantly, these patients need to be informed about the worse functional outcomes compared to younger patients. Moreover, perioperative morbidity and mortality is increased in elderly patients, so patient selection according to comorbidities is an important issue that needs to be addressed. Under these circumstances, RP in well-selected patients ≥75 years remains a feasible management option.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

PM drafted the manuscript and reviewed literature. TC, FKC, and HH edited the manuscript. DT drafted the manuscript, edited the manuscript, and supervised the whole work. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

COMPETING INTERESTS

All authors declare no competing interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.WHO, IARC. GLOBACON 2012: Estimated Cancer Incidence, Mortality, and Prevalence Worldwide in 2012. [Last accessed on 2017 Apr 01]. Available from: http://www.globocan.iarc.fr/Pages/ fact_sheets_cancer.aspx .

- 2.Arnold M, Karim-Kos HE, Coebergh JW, Byrnes G, Antilla A, et al. Recent trends in incidence of five common cancers in 26 European countries since 1988: analysis of the European cancer observatory. Eur J Concer. 2015;51:1164–87. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2013.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Statistisches Bundesamt, Bevölkerung Deutschlands bis 2060 – 12. Koordinierte Bevölkerungsvorausberechnung. (Federal Statistical Office, Population of Germany up to 2060 – 12. Coordinated Population Pre-Calculation. Federal Statistical Office. 2009. [Last accessed on 2017 Apr 01]. Available from: https://www.destatis.de/DE/ Publikationen/Thematisch/Bevoelkerung/VorausberechnungBevoelkerung/ BevoelkerungDeutschland2060Presse5124204099004.pdf?__ blob=publicationFile . [Article in German]

- 4.Zlotta AR, Egawa S, Pushkar D, Govorov A, Kimura T, et al. Prevalence of prostate cancer on autopsy: cross-sectional study on unscreened Caucasian and Asian men. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105:1050–8. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djt151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bellera CA, Rainfray M, Mathoulin-Pélissier S, Mertens C, Delva F, et al. Screening older cancer patients: first evaluation of the G-8 geriatric screening tool. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:2166–72. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Borson S, Scanlan JM, Chen P, Ganguli M. The Mini-Cog as a screen for dementia: validation in a population-based sample. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51:1451–4. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51465.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Droz JP, Albrand G, Gillessen S, Hughes S, Mottet N, et al. Management of prostate cancer in elderly patients: recommendations of a task force of the international society of geriatric oncology. Eur Urol. 2017;72:521–31. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2016.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lunardi P, Ploussard G, Grosclaude P, Roumiguié M, Soulié M, et al. Current impact of age and comorbidity assessment on prostate cancer treatment choice and over/undertreatment risk. World J Urol. 2017;35:587–93. doi: 10.1007/s00345-016-1900-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bubolz T, Wasson JH, Lu-Yao G, Barry MJ. Treatments for prostate cancer in older men: 1984-1997. Urology. 2001;58:977–82. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(01)01434-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Houterman S, Janssen-Heijnen ML, Hendrikx AJ, Berg HA, Coebergh JW. Impact of comorbidity on treatment and prognosis of prostate cancer patients: A population-based study. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2006;58:60–7. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2005.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mottet N, Bellmunt J, Bolla M, Briers E, Cumberbatch MG, et al. EAU-ESTRO-SIOG guidelines on prostate cancer. Part 1: screening, diagnosis, and local treatment with curative intent. Eur Urol. 2017;71:618–29. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2016.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mohler JL, Kantoff PW, Armstrong AJ, Bahnson RR, Cohen M, et al. Prostate cancer, version 2.2014. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2014;12:686–718. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2014.0072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thompson I, Thrasher JB, Aus G, Burnett AL, Canby-Hagino ED, et al. Guideline for the management of clinically localized prostate cancer: 2007 update. J Urol. 2007;177:2106–31. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Statistisches Bundesamt, Bevölkerung und Erwerbstätigkeit: Natürliche Bevölkerungsbewegung 2012. Federal Statistical Office, Population and Employment: Natural Population Movement 2012. [Last accessed on 2017 Apr 01]. Available from: https://www. destatis.de/DE/Publikationen/Thematisch/Bevoelkerung/Bevoelkerungsbewegung/ Bevoelkerungsbewegung2010110127004.pdf?__blob=publicationFile . Article in German.

- 15.Eurostat. Europe in Figures – Eurostat Yearbook 2014. [Last accessed on 2017 Apr 01]. Available from: http://www. ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Europe_in_figures_-_Eurostat_ yearbook .

- 16.U.S. Census Bureau Statistical Abstract of the United States. Births, Deaths, Marriages, and Divorces 2012. [Last accessed on 2017Apr 01]. Available from: https://www.census.gov/ prod/2011pubs/12statab/vitstat.pdf .

- 17.Mandel P, Graefen M, Michl U, Huland H, Tilki D. The effect of age on functional outcomes after radical prostatectomy. Urol Oncol. 2015;33:e11–8. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2015.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alibhai SM, Naglie G, Nam R, Trachtenberg J, Krahn MD. Do older men benefit from curative therapy of localized prostate cancer? J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:3318–27. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.09.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rider JR, Sandin F, Andrén O, Wiklund P, Hugosson J, et al. Long-term outcomes among noncuratively treated men according to prostate cancer risk category in a nationwide, population-based study. Eur Urol. 2013;63:88–96. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Akre O, Garmo H, Adolfsson J, Lambe M, Bratt O, et al. Mortality among men with locally advanced prostate cancer managed with noncurative intent: a nationwide study in PCBaSe Sweden. Eur Urol. 2011;60:554–63. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2011.05.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bratt O, Folkvaljon Y, Hjälm Eriksson M, Akre O, Carlsson S, et al. Undertreatment in men in their seventies with high-risk nonmetastic prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2015;68:53–8. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leung KM, Hopman WM, Kawakami J. Challenging the 10-year rule: the accuracy of patient life expectancy predictions by physicians in relation to prostate cancer management. Can Urol Assoc J. 2012;6:367–73. doi: 10.5489/cuaj.11161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sammon JD, Abdollah F, D’Amico A, Gettman M, Haese A, et al. Predicting life expectancy in men diagnosed with prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2015;68:756–65. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2015.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hamilton AS, Fleming ST, Wang D, Goodman M, Wu XC, et al. Clinical and demographic factors associated with receipt of non guideline-concordant initial therapy for nonmetastatic prostate cancer. Am J Clin Oncol. 2016;39:55–63. doi: 10.1097/COC.0000000000000017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Walz J, Gallina A, Perrotte P, Jeldres C, Trinh QD, et al. Clinicians are poor raters of life-expectancy before radical prostatectomy or definitive radiotherapy for localized prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2007;100:1254–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2007.07130.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boehm K, Dell’Oglio P, Tian Z, Capitanio U, Chun FK, et al. Comorbidity and age cannot explain variation in life expectancy associated with treatment of non-metastatic prostate cancer. World J Urol. 2017:35: 1031–6. doi: 10.1007/s00345-016-1963-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Labanaris A, Witt J, Zugor V. Robotic-assisted radical prostatectomy in men ≥75 years of age.surgical, oncological and functional outcomes. Anticancer Res. 2012;35:2085–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Everaerts W, Van Rij S, Reeves F, Costello A. Radical treatment of localised prostate cancer in the elderly. BJU Int. 2015;116:847–52. doi: 10.1111/bju.13128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boehm K, Larcher A, Tian Z, Mandel P, Schiffmann J, et al. Low other cause mortality rates reflect good patient selection in patients with prostate cancer treated with radical prostatectomy. J Urol. 2016;196:82–8. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2016.01.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Froehner M, Koch R, Propping S, Liebeheim D, Hübler M, et al. Level of education and mortality after radical prostatectomy. Asian J Androl. 2017;18:173–7. doi: 10.4103/1008-682X.178487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Froehner M, Koch R, Heberling U, Novotny V, Hübler M, et al. An easily applicable single condition-based mortality index for patients undergoing radical prostatectomy or radical cystectomy. Urol Oncol. 2017;35:e17–32. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2016.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Froehner M, Koch R, Hübler M, Zastrow S, Wirth MP. Predicting competing mortality in patients undergoing radical prostatectomy aged 70 yr or older. Eur Urol. 2017;71:710–3. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2016.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Greco KA, Meeks JJ, Wu S, Nadler RB. Robot-assisted radical prostatectomy in men aged ≥70 years. BJU Int. 2009;104:1492–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2009.08718.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kunz I, Musch M, Roggenbuck U, Klevecka V, Kroepfl D. Tumour characteristics, oncological and functional outcomes in patients aged ≥70 years undergoing radical prostatectomy. BJU Int. 2013;111:E24–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2012.11368.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huland H, Graefen M. Changing trends in surgical management of prostate cancer: The end of overtreatment? Eur Urol. 2015;68:175–8. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2015.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mandel P, Kriegmair MC, Kamphake JK, Chun FK, Graefen M, et al. Tumor characteristics and oncologic outcome after radical prostatectomy in men 75 years old or older. J Urol. 2016;196:89–94. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2016.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brassell SA, Rice KR, Parker PM, Chen Y, Farrell JS, et al. Prostate cancer in men 70 years old or older, indolent or aggressive: clinicopathological analysis and outcomes. J Urol. 2011;185:132–7. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lu-Yao GL, McLerran D, Wasson J, Wennberg JE. An assessment of radical prostatectomy: time trends, geographic variation, and outcomes. JAMA. 1993;269:2633–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.269.20.2633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Alibhai SM, Leach M, Tomlinson G, Krahn MD, Fleshner N, et al. 30-day mortality and major complications after radical prostatectomy: influence of age and comorbidity. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:1525–32. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Begg CB, Riedel ER, Bach PB, Kattan MW, Schrag D, et al. Variations in morbidity after radical prostatectomy. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1138–44. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa011788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hansen J, Gandaglia G, Bianchi M, Sun M, Rink M, et al. Re-assessment of 30-, 60- and 90-day mortality rates in non-metastatic prostate cancer patients treated either with radical prostatectomy or radiation therapy. Can Urol Assoc J. 2014;8:E75–80. doi: 10.5489/cuaj.749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Saigal CS, Gore JL, Krupski TL, Hanley J, Schonlau M, et al. Androgen deprivation therapy increases cardiovascular morbidity in men with prostate cancer. Cancer. 2007;110:1493–500. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sanda MG, Dunn RL, Michalski J, Sandler HM, Northouse L, et al. Quality of life and satisfaction with outcome among prostate-cancer survivors. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1250–61. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa074311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Siddiqui SA, Sengupta S, Slezak JM, Bergstralh EJ, Leibovich BC, et al. Impact of patient age at treatment on outcome following radical retropubic prostatectomy for prostate cancer. J Urol. 2006;175:952–7. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)00339-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Magheli A, Rais-Bahrami S, Humphreys EB, Peck HJ, Trock BJ, et al. Impact of patient age on biochemical recurrence rates following radical prostatectomy. J Urol. 2007;178:1933–8. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Malaeb BS, Rashid HH, Lotan Y, Khoddami SM, Shariat SF, et al. Prostate cancer disease-free survival after radical retropubic prostatectomy in patients older than 70 years compared to younger cohorts. Urol Oncol. 2007;25:291–7. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2006.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pfitzenmaier J, Pahernik S, Buse S, Haferkamp A, Djakovic N, et al. Survival in prostate cancer patients ≥70 years after radical prostatectomy and comparison to younger patients. World J Urol. 2009;27:637–42. doi: 10.1007/s00345-009-0414-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pierorazio PM, Humphreys E, Walsh PC, Partin AW, Han M. Radical prostatectomy in older men: survival outcomes in septuagenarians and octogenarians. BJU Int. 2010;106:791–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2010.09239.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tang P, Chen H, Uhlman M, Lin YR, Deng XR, et al. A nomogram based on age, prostate-specific antigen level, prostate volume and digital rectal examination for predicting risk of prostate cancer. Asian J Androl. 2013;15:129–33. doi: 10.1038/aja.2012.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xylinas E, Ploussard G, Paul A, Gillion N, Vordos D, et al. Laparoscopic radical prostatectomy in the elderly (>75 years old): oncological and functional results. Prog Urol. 2010;20:116–20. doi: 10.1016/j.purol.2009.08.037. Article in French. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ryu JH, Kim YB, Jung TY, Kim SI, Byun SS, et al. Radical prostatectomy in korean men aged 75-year or older: safety and efficacy in comparison with patients aged 65-69 years. J Korean Med Sci. 2016;31:957–62. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2016.31.6.957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lu-Yao GL, Albertsen PC, Moore DF, Lin Y, DiPaola RS, et al. Fifteen-year outcomes following conservative management among men aged 65 years or older with localized prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2015;68:805–11. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2015.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fung C, Dale W, Mohile SG. Mohile Prostate cancer in the elderly patient. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:2523–30. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.55.1531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kundu SD, Roehl KA, Eggener SE, Antenor JA, Han M, et al. Potency, continence and complications in 3,477 consecutive radical retropubic prostatectomies. J Urol. 2004;172:2227–31. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000145222.94455.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Catalona WJ, Carvalhal GF, Mager DE, Smith DS. Potency, continence and complication rates in 1,870 consecutive radical retropubic prostatectomies. J Urol. 1999;162:433–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shikanov S, Desai V, Razmaria A, Zagaja GP, Shalhav AL. Robotic radical prostatectomy for elderly patients: probability of achieving continence and potency 1 year after surgery. J Urol. 2010;183:1803–7. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Basto MY, Vidyasagar C, te Marvelde L, Freeborn H, Birch E, et al. Early urinary continence recovery after robot-assisted radical prostatectomy in older Australian men. BJU Int. 2014;114(Suppl 1):29–33. doi: 10.1111/bju.12800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mandel P, Preisser F, Graefen M, Steuber T, Salomon G, et al. High chance of late recovery of urinary and erectile function beyond 12 months after radical prostatectomy. Eur Urol. 2017;71:848–50. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2016.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Corona G, Lee DM, Forti G, O’Connor DB, Maggi M, et al. Age-related changes in general and sexual health in middle-aged and older men: results from the European male ageing study (EMAS) J Sex Med. 2010;7:1362–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01601.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Saigal CS, Wessells H, Pace J, Schonlau M, Wilt TJ, et al. Predictors and prevalence of erectile dysfunction in a racially diverse population. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:207–12. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.2.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]