Abstract

Objective

To measure the Medicaid undercount and analyze response error in the 2007‐2011 Current Population Survey Annual Social and Economic Supplement (CPS ASEC).

Data Sources/Study Setting

Medicaid Statistical Information System (MSIS) 2006‐2010 enrollment data linked to the 2007‐2011 CPS ASEC person records.

Study Design

By linking individuals across datasets, we analyze false‐negative error and false‐positive error in reports of Medicaid enrollment. We use regression analysis to identify factors associated with response error in the 2011 CPS ASEC.

Principal Findings

We find that the Medicaid undercount in the CPS ASEC ranged between 22 and 31% from 2007 to 2011. In 2011, the false‐negative rate was 40%, and 27% of Medicaid reports in CPS ASEC were false positives. False‐negative error is associated with the duration of enrollment in Medicaid, enrollment in Medicare and private insurance, and Medicaid enrollment in the survey year. False‐positive error is associated with enrollment in Medicare and shared Medicaid coverage in the household.

Conclusions

Survey estimates of Medicaid enrollment and estimates of the uninsured population are affected by both false‐positive response error and false‐negative response error, and these response errors are non‐random.

Keywords: administrative data, Medicaid undercount, record linkage, response error, uninsured

1. INTRODUCTION

Medicaid is an important part of our nation's safety net providing health insurance coverage to low‐income children and adults, people with disabilities, and the elderly. Touching the lives of many Americans, the program covered an estimated 72.5 million people in 2013.1 Administrative and survey data provide important information about Medicaid enrollees; however, accurately measuring Medicaid participation in surveys has proven difficult for decades. Dating to the 1990s, research has shown estimates of Medicaid coverage based on the Current Population Survey Annual Social and Economic Supplement (CPS ASEC) have consistently produced an undercount of beneficiaries compared to Medicaid enrollment records.2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 For instance, the 2000 CPS ASEC estimated 32% fewer Medicaid participants compared with Medicaid administrative records. This discrepancy between survey data and administrative records is known as the “Medicaid undercount.”

This issue has important policy implications because it affects estimates of the uninsured population. For instance, individuals undercounted in survey data for Medicaid are considered uninsured if they report no other insurance coverage. Accurate and reliable estimates of the uninsured population serve as the basis for public policy decisions and inform programs focused on expanding insurance coverage.9 Understanding the Medicaid undercount is increasingly important to assess survey estimates of the uninsured population especially given increased Medicaid enrollment following implementation of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA).

We contribute to the Medicaid undercount literature in several ways. First, we extend past work by measuring the Medicaid undercount in the 2007‐2011 CPS ASEC using 2006‐2010 Medicaid Statistical Information System (MSIS) data. Second, with substantially more linkages than previous research, we use linked 2011 CPS ASEC and 2010 MSIS data to evaluate two components of measurement error affecting the undercount: false‐negative error and false‐positive error (Figure S1). Some persons have Medicaid coverage but report no coverage in the CPS ASEC (false‐negative error), lowering survey estimates of Medicaid coverage. Some report Medicaid coverage in the CPS ASEC but cannot be linked to MSIS enrollment data (false‐positive error), increasing survey estimates of Medicaid coverage.

We examine two hypotheses related to how respondents interpret questions about health insurance on the CPS ASEC: Whether they interpret the question as asking about their current coverage status or if they have difficulty remembering past coverage, and whether respondents confuse different programs or only report certain forms of insurance. We also examine the effect of other household members’ insurance coverage and describe demographic and socioeconomic characteristics associated with response error. We then provide adjusted rates of Medicaid coverage and the uninsured correcting for survey response errors. We discuss possible reasons for differences between our estimates and previous research, and we discuss the implications of our findings for uninsured population estimates.

Following years of research, the 2014 CPS ASEC health insurance module was redesigned to address the most problematic features, some of which contributed to the persistent Medicaid undercount.10 The 2014 CPS ASEC asked respondents which months they were uninsured rather than whether they were uninsured at any point during the prior year. This question design aligns more closely with surveys such as the American Community Survey (ACS) and the National Health Interview Survey which ask about health insurance coverage at the time of the survey. Whereas the CPS ASEC has consistently produced a Medicaid undercount, the ACS has been shown to produce an overcount of Medicaid recipients.11

By focusing on the years preceding the CPS ASEC health insurance module redesign, our research will serve as a baseline for understanding resulting changes in survey response error for Medicaid reporting and changes in the Medicaid undercount in subsequent years under the redesigned health insurance module.

2. LITERATURE REVIEW

Discrepancies between Medicaid enrollment data and CPS ASEC estimates of Medicaid coverage were documented in the 1990s.2, 3 Using the 1990‐2000 CPS ASEC, Klerman et al4 evaluated matched CPS ASEC and Medi‐Cal data and found that 30% of adults and 25% of children did not report their Medicaid coverage.

In 2007, multiple institutions partnered on the SNACC Medicaid Undercount Project to better understand the national Medicaid undercount using linked 2000‐2005 CPS ASEC data and Medicaid enrollment data. * SNACC researchers12 determined that the CPS ASEC Medicaid undercount ranged between 31% and 38% from 2000 to 2005. They found reporting error, not editing and imputation procedures, was the main cause of the undercount, in particular false‐negative response error. SNACC researchers found that people in poverty were less likely to report false‐negative errors, and individuals enrolled in Medicaid longer were less likely to report false‐negative errors.

Kincheloe et al9 reviewed research on the Medicaid undercount and false‐negative response error and identified several associated factors. Respondents enrolled in Medicaid may mistakenly report Medicare or another form of public or private coverage. Some respondents with dual Medicare and Medicaid coverage may only report having Medicare and not Medicaid. The scope of benefits and beneficiaries’ health status also affects the accuracy of survey reports of Medicaid coverage. Persons with only partial benefits may not report Medicaid coverage. Similarly, healthier persons not using health services often fail to report Medicaid coverage compared to less healthy persons more frequently seeking health care. Automatic enrollment in some states for those with income below poverty thresholds may also increase underreporting since persons automatically enrolled may be unaware they have Medicaid.

Klerman et al8 explored two explanations for understanding the Medicaid undercount in the CPS ASEC, the point‐in‐time versus recall conjectures. The point‐in‐time explanation suggests that respondents either disregard or do not understand insurance coverage question instructions asking respondents to report on the previous calendar year and instead report their current coverage. Cognitive testing of the CPS ASEC health insurance questions confirmed that some respondents focused on current coverage rather than the previous year.13 SNACC12 researchers also found that those enrolled in Medicaid when surveyed are less likely to report false negatives.

The recall conjecture argues that some respondents have difficulty keeping track of insurance coverage dates. Respondents cannot always recall whether they had Medicaid the previous year, particularly coverage early in the year. To explain the undercount, Klerman et al8 found more support for the recall than the point‐in‐time conjecture. Too few people have different Medicaid coverage status when interviewed than during the prior year to explain the undercount. Instead, the undercount is related to recency of Medicaid coverage with recent coverage yielding more accurate reports.

Respondents reporting for other household members may also contribute to reporting error. Cognitive testing revealed some respondents did not have accurate knowledge of other household members’ coverage, while others failed to include certain household members in their reports.13 Pascale, Roemer, and Resnick14 found support for a shared coverage hypothesis to explain response error in the 2001 CPS ASEC. In their analysis of matched CPS ASEC and MSIS data, respondents were most accurate reporting Medicaid coverage for other household members when the respondent and other household members shared coverage.

Most Medicaid undercount research has focused on false‐negative error rather than false‐positive error since it is a larger component of the undercount. SNACC12 researchers determined false‐positive reports result when persons incorrectly report having Medicaid, or when no linked MSIS record can be identified to verify the CPS ASEC report. The false‐positive error rate in the CPS ASEC for 2000‐2005 ranged between about 20% and 25% of all reports of Medicaid enrollment. Whereas false‐negative error resulted mostly from respondent reporting, a majority of false‐positive error resulted from CPS ASEC editing and imputation procedures, and about 40% resulted from respondent reporting. SNACC researchers found the rate of false positives higher among those in poverty compared to those not in poverty.

We expand on this rich literature and contribute to understanding the Medicaid undercount by updating Medicaid undercount numbers using 2007‐2011 CPS ASEC data. We link more MSIS cases to the CPS ASEC compared to previous research allowing us to more accurately measure and analyze false‐negative and false‐positive errors. Based on prior research, we answer three main research questions regarding response error. First, how is false‐negative reporting associated with the point‐in‐time and recall conjectures? Second, to what extent do program name confusion and selective reporting of health insurance affect false‐negative error and false‐positive response error? And third, how does shared Medicaid coverage in the household affect false‐negative error and false‐positive response error? We also describe demographic and socioeconomic characteristics associated with response error. These findings deepen our knowledge of Medicaid coverage and estimates of the uninsured population based on the CPS ASEC.

3. DATA AND METHODS

For our analysis, we use 2006‐2010 Medicaid administrative records and 2007‐2011 CPS ASEC survey data on health insurance coverage. For reference, the tables show 2000‐2005 Medicaid data and 2001‐2006 CPS ASEC data based on the SNACC12 Phase V Medicaid undercount report; however, discussion of the results focuses on our new years of analysis.

The CPS ASEC is a supplement that samples 98 000 households and collects additional data on poverty, migration, and work experience. Data on Medicaid enrollment are from the MSIS and are submitted electronically by states quarterly to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). The MSIS data contain information for Medicaid enrollees including number of days enrolled by month and Medicaid coverage type.

Several differences exist between the MSIS and CPS ASEC universes. States report MSIS data in fiscal quarters, each Medicaid enrollment record receives a MSIS case number, and multiple records may exist for persons with different case numbers across states. The CPS ASEC includes survey data with persons as the unit of analysis. The MSIS data include the institutionalized population, whereas the CPS ASEC sample does not include persons in institutionalized group quarters. † MSIS data include information on full and restricted benefits, but the CPS ASEC does not collect data on the level of Medicaid benefit eligibility. Finally, MSIS includes point‐in‐time data on enrollment while prior to the 2014 redesign, the CPS ASEC only collected retrospective information on health insurance coverage for the previous calendar year. ‡

We calculate raw and adjusted measures for the Medicaid undercount. The raw measures use the CPS ASEC and MSIS data universes without adjustments. We then adjust both datasets as outlined below to make them more comparable. We use raw and adjusted measures to evaluate the Medicaid undercount and adjusted measures to analyze false‐negative reporting and false‐positive reporting.

For the adjusted MSIS measure, we remove persons residing in institutional group quarters, aggregate the state MSIS data into one national file, and unduplicate by persons. We exclude enrollees reported in MSIS with only partial benefits (e.g, emergency services or family planning) or who are only covered through the State Children's Health Insurance Program (SCHIP). States’ SCHIP reporting in MSIS is not consistent for separate CHIP (S‐CHIP) programs and Medicaid expansion (M‐CHIP) programs thus making it problematic from an administrative records perspective. For the CPS ASEC‐adjusted measure, we exclude persons reported as covered only through SCHIP programs. These participants may not consider themselves to be covered by Medicaid in the same way as those with full benefits. SCHIP is also administered as a separate program from Medicaid in many states, and it is likely that many participating families are not aware of the difference.15

We evaluate false‐negative error and false‐positive error by linking individuals in the CPS ASEC to their MSIS record. In each dataset, individuals are assigned an anonymized unique person identifier called a Protected Identification Key (PIK) via probabilistic record linkage techniques.16, 17 Only observations with PIKs are linkable (Table S1). Therefore, CPS ASEC records with a PIK are re‐weighted to compensate for observations not assigned a PIK. Since there is bias in PIK assignment, the CPS ASEC weighting adjustment factors are calculated based on PIK rates by age group, relative poverty ratio, health insurance status, and whether health insurance status was imputed.

We use two logistic regression models to evaluate the characteristics of people who report false negatives and false positives in the 2011 CPS ASEC. The dependent variable for the false‐negative regression analysis is “1” if a person reported no Medicaid coverage in the CPS ASEC but was enrolled according to 2010 MSIS data. The dependent variable is “0” if the person reported Medicaid coverage and was enrolled in 2010 MSIS data with full benefits. In the false‐positive regression, the dependent variable is “1” if a person reports Medicaid coverage in the 2011 CPS ASEC, but according to 2010 MSIS, they are not receiving partial benefits, full benefits, or coverage through the SCHIP expansion program. The dependent variable is “0” if a person reports Medicaid coverage in the CPS ASEC and has full or partial benefits in MSIS data. Both analyses exclude imputed and edited survey responses since we are interested in the characteristics of persons who report their insurance status as opposed to those whose coverage is edited or imputed.

To address the point‐in‐time versus recall conjecture research question, we measure for whether the respondent was enrolled in MSIS data in 2011, the year the CPS ASEC was conducted. A higher likelihood of false‐positive reporting by newly enrolled respondents not enrolled during the previous calendar year would support the point‐in‐time hypothesis. For false‐negative reports, we measure whether the respondent was enrolled with full benefits in 2011, and for false‐positive reports, we measure whether the respondent was enrolled with full or partial benefits in 2011.

We assess the impact of recall issues on false‐negative error using a measure of Medicaid coverage duration, measured as the number of days a person is enrolled in Medicaid during 2010. We assess the impact of recall issues on false‐positive error by observing whether persons had Medicaid coverage in MSIS for 2009. For false‐positive error, the hypothesis predicts that people enrolled in Medicaid 2 years before the survey are more likely to report false positives.

One source of false‐positive error is the inability to link persons reporting Medicaid coverage with their MSIS enrollment data. A person may be correct in reporting coverage, but if the MSIS record has no PIK because it lacked necessary information for PIK assignment, the MSIS data cannot be linked to the survey data. For 2000‐2005, it was estimated that between 39.4 and 62.1% of false‐positive errors in the CPS ASEC were incorrectly identified as a consequence of unlinkable MSIS records.12 For 2010, that estimate drops to about 18% as a result of an increased PIK rate in MSIS. Regression results are interpreted in light of this caveat. In particular, false‐positive responses with coverage in 2009 and 2011 may be more likely to have an unlinkable MSIS record.

For our second research question, to account for possible confusion between Medicaid and other health insurance, both models measure CPS ASEC reports of enrollment in Medicare and any other type of insurance. To address our third research question on shared coverage, we measure whether anyone else in the household also had Medicaid enrollment data in MSIS.

We also describe demographic and socioeconomic factors associated with false‐negative error and false‐positive error. We include Hispanic origin, race, sex, age, education level, foreign‐born status, and logged household income in both models.

4. RESULTS

4.1. Medicaid undercount

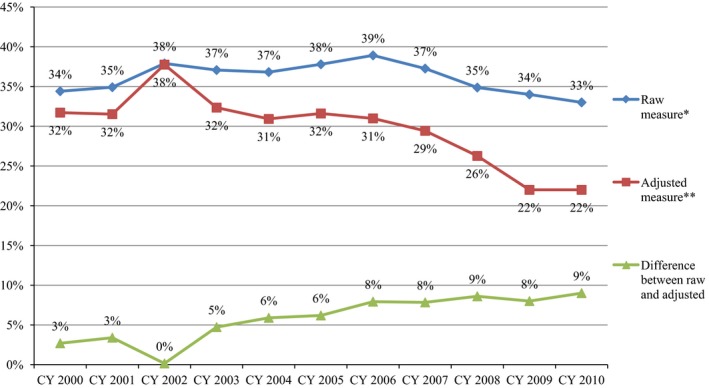

Figure 1 and Table 1 present results for measurement of the Medicaid undercount in the CPS ASEC. We include SNACC Medicaid undercount results for 2000‐2005 for comparison. The raw undercount measures ranged from 39% to 33% from 2006 to 2010, similar to previous years of analysis. The adjusted measure of the Medicaid undercount ranged from 31% to 22% from 2006 to 2010 with 2010 the lowest for the entire time series.

Figure 1.

Medicaid undercount in CPS ASEC, 2000‐2010 [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Sources: SNACC Phase V (2010) for years 2000‐2005; authors’ computations for years 2006‐2010; CPS ASEC and MSIS. *The “Raw measure” uses both the CPS ASEC and MSIS data universes without adjustments to either data series. **The “Adjusted measure” includes adjustment made to both the CPS ASEC and MSIS data universes to make them more comparable.

Table 1.

Measuring the Medicaid undercount in the CPS ASEC

| CY 2000 | CY 2001 | CY 2002 | CY 2003 | CY 2004 | CY 2005 | CY 2006 | CY 2007 | CY 2008 | CY 2009 | CY 2010 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Undercount | |||||||||||

| Raw measurea | 34.4% | 34.9% | 37.9% | 37.1% | 36.8% | 37.8% | 38.9% | 37.3% | 34.9% | 33.9% | 33.2% |

| Adjusted measureb | 31.7% | 31.5% | 37.8% | 32.3% | 30.9% | 31.6% | 31.0% | 29.4% | 26.3% | 22.4% | 22.0% |

| Difference between raw and adjusted | 2.7% | 3.4% | 0.2% | 4.7% | 5.9% | 6.2% | 7.9% | 7.8% | 8.6% | 11.5% | 11.2% |

| MSIS enrollment | |||||||||||

| Raw total | 45 050 000 | 48 550 000 | 53 550 000 | 56 650 000 | 59 350 000 | 61 250 000 | 62 814 724 | 63 251 758 | 65 763 995 | 72 377 229 | 72 740 815 |

| Adjusted total | 38 150 000 | 40 450 000 | 45 950 000 | 45 600 000 | 47 700 000 | 49 200 000 | 48 791 594 | 48 813 182 | 50 520 559 | 53 813 902 | 55 576 733 |

| CPS enrollment | |||||||||||

| Raw total | 29 550 000 | 31 600 000 | 33 250 000 | 35 650 000 | 37 500 000 | 38 100 000 | 38 369 832 | 39 684 984 | 42 830 746 | 47 847 441 | 48 580 103 |

| Adjusted total | 26 050 000 | 27 700 000 | 28 600 000 | 30 850 000 | 32 950 000 | 33 650 000 | 33 673 128 | 34 450 753 | 37 249 946 | 41 755 208 | 43 348 345 |

Notes: Data for Calendar Years 2000‐2005 from SHADAC (2010). Numbers are rounded for 2000‐2005 according to SHADAC report.

The “Raw measure” uses both the CPS ASEC and MSIS data universes without adjustments to either data series.

The “Adjusted measure” includes adjustment made to both the CPS ASEC and MSIS data universes to make them more comparable.

The percent difference between raw and adjusted measures of the undercount increased over time reaching a high of 11.5% in 2009 and 11.2% in 2010. The statistically significant decline in the adjusted measure and corresponding increase in the gap between raw and adjusted measures likely result from more duplicate persons identified in MSIS data through improved PIK assignment (Table S1). There may also be an increased use of partial benefits relative to full benefits, and removing these lowers the adjusted undercount and increases the difference with the raw undercount.

4.2. Measurement error descriptives

Table 2 presents rates for false‐negative survey error. We show SNACC results from 2000‐2005 for comparison. For 2000‐2010, there were between 40% and 45% of false‐negative reports for Medicaid in the CPS ASEC. This declined from 45% in 2006 to 39% in 2009 and 40% in 2010. Only about 60% of CPS ASEC respondents linked to MSIS data correctly classified themselves as enrolled in Medicaid. The results indicate the persistence of false‐negative error in the CPS ASEC.

Table 2.

False‐negative survey errors for Medicaid reporting in the CPS ASEC

| CY 2000 | CY 2001 | CY 2002 | CY 2003 | CY 2004 | CY 2005 | CY 2006 | CY 2007 | CY 2008 | CY 2009 | CY 2010 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Correctly classified as enrolled | 19 090 000 | 20 550 000 | 21 350 000 | 23 270 000 | 24 380 000 | 24 830 000 | 23 800 091 | 24 538 855 | 26 397 133 | 29 522 452 | 29 746 502 |

| Incorrectly classified as not enrolled (false‐negative errors) | 14 360 000 | 15 450 000 | 17 250 000 | 17 680 000 | 18 870 000 | 18 670 000 | 19 271 550 | 18 942 205 | 18 616 298 | 18 699 087 | 20 135 208 |

| Percent enrolled who reported no enrollment | 42.9% | 42.9% | 44.7% | 43.2% | 43.6% | 42.9% | 44.7% | 43.6% | 41.4% | 38.8% | 40.4% |

| Source of enrollment status among false‐negative errors | |||||||||||

| Reported | 11 030 000 | 11 960 000 | 13 240 000 | 13 730 000 | 13 980 000 | 14 350 000 | 14 903 989 | 14 899 526 | 14 542 359 | 14 666 776 | 14 632 048 |

| Imputed | 3 340 000 | 3 500 000 | 4 000 000 | 3 900 000 | 4 880 000 | 4 320 000 | 4 367 561 | 4 042 679 | 4 073 939 | 4 032 311 | 5 503 160 |

| Percent of false negatives that were reported (not imputed) | 76.8% | 77.4% | 76.8% | 77.9% | 74.1% | 76.9% | 77.3% | 78.7% | 78.1% | 78.4% | 72.7% |

| “Other Insurance” status of false‐negative population: | |||||||||||

| Insured | 8 600 000 | 9 190 000 | 10 370 000 | 10 580 000 | 11 170 000 | 10 870 000 | 11 534 054 | 11 663 882 | 11 458 087 | 11 247 313 | 12 084 859 |

| Uninsured | 5 760 000 | 6 260 000 | 6 880 000 | 7 100 000 | 7 700 000 | 7 800 000 | 7 737 495 | 7 278 323 | 7 158 211 | 7 451 773 | 8 050 349 |

| Percent false negatives who are uninsured | 40.1% | 40.5% | 39.9% | 40.2% | 40.8% | 41.8% | 40.1% | 38.4% | 38.5% | 39.9% | 40.0% |

Notes: Enrollment status is edited only to assign enrollment, not to take it away, so it never causes false‐negative errors.

Re‐weighted data for Calendar Years 2000‐2005 from SHADAC (2010). Numbers are rounded for 2000‐2005 according to SHADAC report.

Consistent with previous research, for 2006‐2009, the majority of Medicaid false‐negative reports in the CPS ASEC resulted from reported insurance status (between 73% and 79%) while the remainder resulted from data imputation procedures. Among the false negatives, about 60% reported having other insurance coverage. Conversely, about 40% of the Medicaid false negatives (8 million in 2010) erroneously contributed to estimates of the uninsured.

Table 3 presents results for the CPS ASEC false‐positive respondents. The false‐positive error rate for 2000‐2010 ranged from 2.6% to 4.7%. Among all CPS ASEC records with a PIK not matched to MSIS records, 3% to 5% reported Medicaid coverage in the survey. Of all Medicaid reports between 2000 and 2010, between 21% and 27% were identified as false‐positive errors. While false‐negative error mostly resulted from respondent reporting, about 60% of false positives resulted from edit and imputation procedures. CPS ASEC health insurance edits are intended to improve response accuracy by using other interview information to assign edited values. Medicaid coverage can only be assigned through edits; it cannot be taken away. Compared to individual edits, imputations are intended to improve better survey estimates overall. Future research should disentangle these different processes.

Table 3.

Medicaid false‐positive survey errors for Medicaid reporting in the CPS ASEC

| CY 2000 | CY 2001 | CY 2002 | CY 2003 | CY 2004 | CY 2005 | CY 2006 | CY 2007 | CY 2008 | CY 2009 | CY 2010 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linkable records not in MSIS | 244 050 000 | 243 600 000 | 242 900 000 | 241 750 000 | 243 650 000 | 245 250 000 | 248 313 514 | 250 089 263 | 250 486 590 | 249 528 631 | 249 691 437 |

| CPS adjusted enrollment | 26 050 000 | 27 700 000 | 28 600 000 | 30 850 000 | 32 950 000 | 33 650 000 | 33 673 128 | 34 450 753 | 37 249 946 | 41 755 208 | 43 348 345 |

| Total false‐positive errors | 6 460 000 | 6 420 000 | 6 200 000 | 6 380 000 | 7 460 000 | 7 680 000 | 8 664 802 | 8 494 168 | 9 101 359 | 10 167 982 | 11 618 694 |

| False‐positive error rate | 2.6% | 2.6% | 2.6% | 2.6% | 3.1% | 3.1% | 3.5% | 3.4% | 3.6% | 4.1% | 4.7% |

| Percent reporting enrolled but do not have MSIS enrollment data | 24.8% | 23.2% | 21.7% | 20.7% | 22.6% | 22.8% | 25.7% | 24.7% | 24.4% | 24.4% | 26.8% |

| Source of enrollment status among false‐positive errors: | |||||||||||

| Reported | 2 460 000 | 2 740 000 | 2 400 000 | 2 540 000 | 2 500 000 | 2 640 000 | 3 286 602 | 3 427 260 | 3 472 635 | 3 901 083 | 4 411 684 |

| Imputed | 2 560 000 | 2 520 000 | 2 480 000 | 2 520 000 | 3 140 000 | 3 060 000 | 3 231 220 | 2 873 591 | 3 155 255 | 3 715 733 | 4 475 359 |

| Edited | 1 420 000 | 1 160 000 | 1 320 000 | 1 320 000 | 1 840 000 | 1 980 000 | 2 146 980 | 2 193 317 | 2 473 469 | 2 551 166 | 2 731 651 |

| Reported, % | 38.2% | 42.7% | 38.7% | 39.8% | 33.4% | 34.4% | 37.9% | 40.3% | 38.2% | 38.4% | 38.0% |

| Imputed, % | 39.8% | 39.3% | 40.0% | 39.5% | 42.0% | 39.8% | 37.3% | 33.8% | 34.7% | 36.5% | 38.5% |

| Edited, % | 22.0% | 18.1% | 21.3% | 20.7% | 24.6% | 25.8% | 24.8% | 25.8% | 27.2% | 25.1% | 23.5% |

Notes: Data for calendar years 2000‐2005 from SHADAC (2010). Numbers are rounded for 2000‐2005 according to SHADAC report.

4.3. Regression results

Table 4 shows logistic regression results modeling false‐negative reports of Medicaid coverage in the CPS ASEC. Of the weighted sample, 42% are coded as false negatives, and 58% correctly reported Medicaid coverage.

Table 4.

Weighted logistic regression results: survey response error in 2011 CPS ASEC

| Variables | False‐negative response | False‐positive response |

|---|---|---|

| Odds ratios | Odds ratios | |

| Demographic and socioeconomic characteristics | ||

| Hispanic origin (not Hispanic omitted) | 1.34*** | 2.30*** |

| Race (White alone omitted) | ||

| Black alone | 1.21** | 1.35 |

| American Indian or Alaska Native alone | 1.34 | 1.87 |

| Asian alone | 1.35* | 2.60** |

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander alone | 1.63 | 6.26** |

| Two or more races | 0.84 | 0.74 |

| Female (Male omitted) | 0.86** | 0.71* |

| Age (18‐24 omitted) | ||

| 25‐44 | 0.94 | 1.19 |

| 45‐64 | 0.71*** | 1.60* |

| 65+ | 1.30* | 2.06* |

| Education (less than high school omitted) | ||

| High school degree | 1.33*** | 1.30 |

| Some college | 1.19* | 1.21 |

| Bachelor's degree | 1.43** | 1.19 |

| Graduate degree | 1.33 | 2.83* |

| Foreign born (U.S. born omitted) | 1.27** | 0.80 |

| Insurance coverage | ||

| Reported Medicare coverage | 1.50*** | 0.71 |

| Reported enrolled in another insurance program | 5.88*** | 0.63* |

| Number of days enrolled in Medicaid in 2010 (1‐60 omitted) | ||

| 61‐180 | 0.55*** | |

| 181‐364 | 0.29*** | |

| All year | 0.20*** | |

| Enrolled in Medicaid in previous year (2009) | 0.02*** | |

| Enrolled in Medicaid in survey year (2011) | 0.39*** | 0.04*** |

| Household variables | ||

| Shared coverage | 1.01 | 0.38*** |

| Logged household income | 0.96*** | 1.06* |

| −2 log likelihood | 24 839 027 | 12 883 186 |

| Weighted N | 18 202 244 | 13 974 634 |

*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001.

Source: 2011 CPS ASEC, MSIS administrative records.

We find support for both point‐in‐time and recall conjectures. Medicaid enrollment in the survey year is associated with a lower likelihood of a false‐negative report, supporting the point‐in‐time conjecture that some report their Medicaid status at the time of interview rather than the previous year. Longer Medicaid enrollment is associated with lower odds of a false‐negative report, supporting the recall conjecture. Compared to those enrolled 60 days or fewer, those enrolled the entire year were least likely to provide false‐negative responses (80% lower odds).

We also find support that people may be confusing Medicaid with Medicare and other insurance programs, or their dual‐enrollment is leading them not to report Medicaid. Reporting some other form of insurance makes a person nearly six times as likely to provide a false‐negative report. Reporting Medicare is associated with about 50% higher odds of a false‐negative response. We did not find evidence that shared Medicaid coverage in the household is associated with false‐negative reporting error. The odds ratio is close to 1 and not significant.

Hispanics have about 34% higher odds of a false‐negative Medicaid report compared to non‐Hispanics. For race, persons reported in the CPS ASEC as either Black alone or Asian alone have a greater likelihood of a false‐negative response compared to persons reported as White alone. Odds ratios are not significant for other race groups. §

Fewer women than men report false negatives. Compared to persons aged 18‐24, persons aged 45‐64 are less likely to have false‐negative reports, and persons aged 65 and over are more likely to report a false negative. ¶ This finding can be understood in the context of the higher odds of reporting a false‐negative response when also reporting Medicare given that age and Medicare eligibility are highly correlated with most of those over age 65 enrolled in Medicare. There is no statistical difference in reporting a false negative between those aged 25‐44 and persons aged 18 to 24. Foreign born is associated with a greater likelihood of a false‐negative Medicaid response.

Relative to those with less than a high school diploma, persons with a high school degree, some college, or a bachelor's degree are more likely to give false‐negative Medicaid reports. However, persons with a graduate degree are not statistically different from those without a high school diploma. Persons with higher family incomes are less likely to give false‐negative reports than persons with lower family incomes.

Next, we discuss regression results on false‐positive reporting (Table 4). Of the weighted sample, about 16% are coded as false‐positive reports without Medicaid enrollment, and about 84% are coded as having Medicaid enrollment in MSIS.

Among those reporting Medicaid coverage, those also reporting Medicare coverage are no more or less likely to give false‐positive reports. However, those reporting other forms of insurance are less likely to give false‐positive reports than those who do not. Persons enrolled in Medicaid in the previous year and persons enrolled in Medicaid in the survey year were less likely to have false‐positive reports (90% lower odds).

When Medicaid coverage is shared in the household, the respondent is less likely to give a false‐positive report. False‐positive reports are more likely when the respondent is the only one reporting Medicaid coverage in the household.

Hispanics are twice as likely as non‐Hispanics to have false‐positive reports. For race, relative to those reporting White alone, persons reporting Asian alone or Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander alone have a higher likelihood of a false‐positive report with approximately three and six times greater odds, respectively. **

Similar to results on false negatives, among persons who report Medicaid coverage in the CPS ASEC, women are less likely than men to give a false‐positive response with about 29% lower odds. Persons aged 45‐64 are about 60% more likely to give false‐positive reports, and persons aged 65 and older are twice as likely compared to persons age 18‐24. In contrast to the false‐negative results, there is no foreign‐born effect. Persons with a graduate degree are more likely to provide a false‐positive response compared to persons with less than a high school degree, though the results are not significant for other education levels. And as logged family income increases, so does the likelihood of false‐positive reports.

4.4. Adjusted insurance rates

When respondents incorrectly report they do not have Medicaid coverage, they lower estimates of Medicaid coverage, whereas false‐positive reports of Medicaid coverage may incorrectly add to Medicaid enrollment estimates. When we adjust the Medicaid coverage rates accounting for false‐negative Medicaid reporting and false‐positive Medicaid reporting, the estimated Medicaid coverage rate increases from 15.9% to 18.7%. Recall, however, a small proportion of false positives may appear as such because the corresponding MSIS enrollment data could not be linked to the CPS ASEC response, so this adjustment is an estimate, and the actual coverage rate may be higher.

When respondents report false negatives for Medicaid and also do not have any other form of government or private insurance, then those persons incorrectly increase the uninsured population. For the 2011 CPS ASEC, 8.1 million persons were incorrectly classified as uninsured (Table S2). Conversely, persons who report only Medicaid coverage when no enrollment data support that response may incorrectly reduce the uninsured population. For the 2011 CPS ASEC, this amounted to an upward bound of 5.8 million persons not included in the count of the uninsured. Similarly adjusting the 2011 CPS ASEC estimate of the uninsured population, the percent uninsured declines from 16.3% to 15.6%. However, some who report false positives for Medicaid may have health insurance but report the wrong type of coverage. For example, some enrolled in SCHIP programs may incorrectly report Medicaid coverage. Others may only appear to be false positives because their MSIS data could not be linked to the CPS ASEC. The adjusted estimated uninsured rate may actually be lower than calculated.

5. CONCLUSION

The Medicaid undercount measured from 2000 to 2005 persists when analyzing 2006‐2010. Based on the regression analysis presented here, false‐negative and false‐positive reporting errors are not randomly distributed across persons in the CPS ASEC. We found evidence to support both the point‐in‐time and recall conjectures with both processes affecting false‐negative reporting which suggests that these are related processes rather than competing explanations. Respondents with a longer duration of coverage and those currently enrolled are both less likely to be false negatives, and we would expect to see an overlap between these two factors. Enrollment in Medicaid in the survey year and the duration of Medicaid enrollment in the previous calendar year both lower the likelihood of false‐negative reports. We also found effects of enrollment in other insurance programs on response error. We found evidence to support the shared coverage hypothesis for false‐positive responses but not for false‐negative response error; however, the latter may be related to our different operationalization of shared coverage from Pascale, Roemer, and Resnick.14 Future research should explore shared coverage related to overlapping coverage and whether the respondent is reporting for dependent children. We also find evidence of variation in false‐negative and false‐positive survey response errors according to race and ethnicity, age, sex, education, and foreign‐born status. Additional research is needed to examine more closely these relationships.

Future work should investigate the utility of MSIS administrative records for assisting CPS ASEC editing and imputation procedures. This could facilitate reductions in response error and increased confidence in CPS ASEC estimates of Medicaid coverage. However, this would require more timely delivery and processing of Medicaid enrollment data.

The CPS ASEC is an important survey instrument providing important insights to the U.S. population. Given that the Medicaid undercount in the CPS ASEC has persisted over time, this suggests the importance of appropriate steps to align more closely survey estimates of Medicaid coverage with administrative record totals from Medicaid enrollment data. Survey error reduces accuracy of estimates of Medicaid coverage, other coverage, and the uninsured population.

To achieve more accurate estimates of insurance coverage, the Census Bureau has regularly conducted research and testing on question design for health insurance in the CPS ASEC. Beginning in 2014, the CPS ASEC asks respondents which months they were uninsured rather than whether they were uninsured at any point during the prior year.10 This redesign will likely reduce response error to the health insurance question and improve estimates of the Medicaid covered population and yield improved estimates of the uninsured population.18 Future analysis on the Medicaid undercount and survey response error will compare the Medicaid undercount and response error preceding the redesign with the post‐redesign CPS ASEC. We expect response error and the Medicaid undercount to decline compared to the results we have presented here. We will also measure any changes to the Medicaid undercount in the years since Medicaid expansion under the ACA to determine the extent to which Medicaid expansion may shape response error and CPS ASEC estimates of Medicaid enrollment and the uninsured. Together, this will further our understanding of survey estimates of health insurance coverage and the uninsured.

Supporting information

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Joint Acknowledgment/Disclosure Statement: This research was conducted under the employment of the U.S. Census Bureau. This article is released to inform interested parties of research and to encourage discussion. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the U.S. Census Bureau. The information in this article has been approved for release by the Disclosure Review Board.

Noon JM, Fernandez LE, Porter SR. Response error and the Medicaid undercount in the current population survey. Health Serv Res. 2019;54:34–43. 10.1111/1475-6773.13058

ENDNOTES

*Researchers from the University of Minnesota's State Health Access Data Assistance Center, CMS, Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, National Center for Health Statistics, Administration for Healthcare Research and Quality, and the Census Bureau partnered to research the CPS ASEC Medicaid undercount. The project was named the SNACC Medicaid Undercount Project to represent collaborating agencies. SNACC reports can be retrieved from: https://www.census.gov/did/www/snacc/

†CPS ASEC includes Armed Forces personnel and families in civilian housing or on military bases.

‡The 2011 CPS ASEC asked about Medicaid coverage during the past calendar year, “At any time in 2010, (was/were) (you/anyone in this household) covered by Medicaid?” If “yes,” the questionnaire asks who was covered.

§Using another year, regression results for Asian alone were not significant. Because of a small number of observations this result may not be robust.

¶We exclude minors because of the education variable.

**Regression results differed for different years suggesting they may not be robust because of few observations.

REFERENCES

- 1. Burwell SM. 2014. Actuarial report on the financial outlook for Medicaid. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; 2014. https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/financing-and-reimbursement/downloads/medicaid-actuarial-report-2014.pdf. Accessed August 7, 2018.

- 2. Lewis CH, Elwood M, Czajka J. Counting the Uninsured: A Review of the Literature. Washington, DC: The Urban Institute; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Card D, Hildreth AKG, Shore‐Sheppard LD. The measurement of Medicaid coverage in the SIPP. J Bus Econ Stat. 2004;22(4):410‐420. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Klerman JA, Ringel JS, Roth B. Under‐Reporting of Medicaid and Welfare in the Current Population Survey. Santa Monica, CA: RAND; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Call KT, Davidson G, Davern M, Blewett LA, Nyman R. The Medicaid undercount and bias to estimates of uninsurance: new estimates and existing evidence. Health Serv Res. 2008;43(3):901‐914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Davern M, Call KT, Ziegenfuss J, Davidson G, Beebe TJ, Blewett LA. Validating health insurance coverage survey estimates: a comparison between self‐reported coverage and administrative data records. Public Opin Q. 2008;72(2):241‐259. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Davern M, Klerman JA, Baugh DK, Call KT, Greenberg GD. An examination of the Medicaid undercount in the Current Population Survey: preliminary results from record linking. Health Serv Res. 2009;44(3):965‐987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Klerman JA, Davern M, Call KT, Lynch V, Ringel JD. Understanding the Current Population Survey's insurance estimates and the Medicaid “undercount”. Health Aff. 2009;28(6):991‐1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kincheloe J, Brown ER, Frates J, Call KT, Yen W, Watkins J. Can we trust population surveys to count Medicaid enrollees and the uninsured? Health Aff. 2006;25(4):1163‐1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pascale J, Boudreaux M, King R. Understanding the new Current Population Survey health insurance questions. Health Serv Res. 2016;51(1):240‐261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Boudreaux MH, Call KT, Turner J, Fried B, O'Hara B. Measurement error in public health insurance reporting in the American Community Survey: evidence from record linkage. Health Serv Res. 2015;50(6):1973‐1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. SNACC Phase V . Phase V Research Results: Extending the Phase II Analysis of Discrepancies between the National Medicaid Statistical Information System (MSIS) and the Current Population Survey (CPS) Annual Social and Economic Supplement (ASEC) from Calendar Years 2000‐2001 to Calendar Years 2002‐2005. Minneapolis, MN: State Health Access Data Assistance Center; 2010. http://www.shadac.org/publications/snacc-phase-v-report. Accessed August 7, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pascale J. Measuring health insurance in the U.S. Statistical Research Division Research Report Series, Survey Methodology #2007‐11. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pascale J, Roemer MI, Resnick DM. Medicaid underreporting in the CPS: results from a record check study. Public Opin Q. 2009;73(3):497‐520. [Google Scholar]

- 15. SNACC Phase II . Phase II Research Results: Examining Discrepancies between the National Medicaid Statistical Information System (MSIS) and the Current Population Survey (CPS) Annual Social and Economic Supplement (ASEC). Minneapolis, MN: State Health Access Data Assistance Center; 2008. http://www.census.gov/did/www/snacc/docs/SNACC_Phase_II_Full_Report.pdf. Accessed August 7, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fellegi IP, Sunter AB. A theory for record linkage. J Am Stat Assoc. 1969;64:1183‐1210. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wagner D, Layne M. The person identification validation system (PVS): applying the Center for Administrative Records Research and Applications’ (CARRA) record linkage software. Center for Administrative Records Research and Applications Working Paper #2014‐01. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Brault M, Medalia C, O'Hara B, Rodean J, Steinweg A. Changing the CPS health insurance questions and the implications on the uninsured rate: redesign and production estimates. SEHSD Working Paper 2014‐16. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau; 2014. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials