Abstract

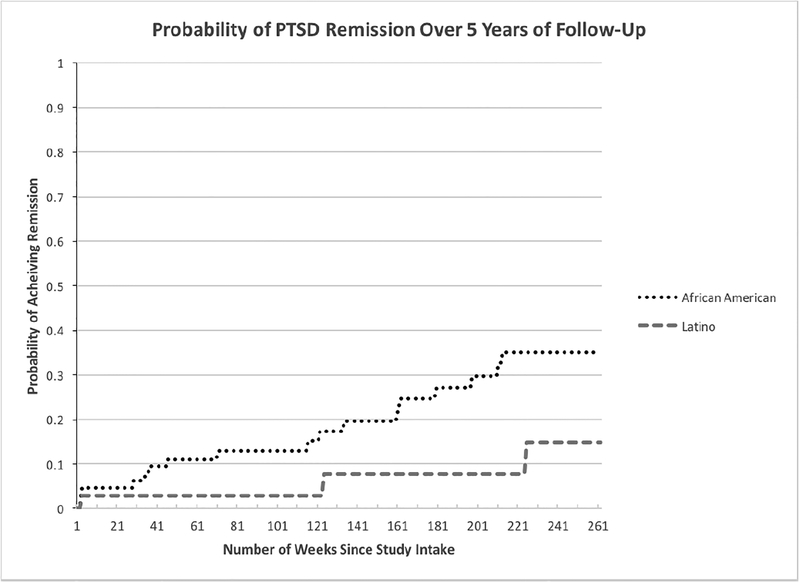

Research has suggested that African American and Latino adults may develop posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) at higher rates than White adults, and that the clinical course of PTSD in these minority groups is poor. One factor that may contribute to higher prevalence and poorer outcome in these groups are sociocultural factors and racial stressors, such as experiences with discrimination. To date, however, no research has explored the relationship between experiences with discrimination and risk for PTSD, and very little research has examined the course of illness for PTSD in African Americans and Latino samples. The present study examined these variables in the only longitudinal clinical sample of 139 Latino and 152 African American adults with anxiety disorders, the Harvard/Brown Anxiety Research Project – Phase II (HARP-II). Over 5 years of follow-up, remission rates for African Americans and Latinos with PTSD in this sample were 0.35 and 0.15 respectively, and reported frequency of experiences with discrimination significantly predicted PTSD diagnostic status in this sample, but did not predict any other anxiety or mood disorder. These findings demonstrate the chronic course of PTSD in African American and Latino adults, and highlight the important role that racial and ethnic discrimination may play in the development of PTSD among these populations. Implications for an increased focus on these sociocultural stressors in the assessment and treatment of PTSD in African American and Latino individuals are discussed.

Keywords: Post-traumatic stress disorder, longitudinal course, minority samples, African Americans, Latinos, discrimination, risk factors

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a serious and common mental illness with lifetime prevalence rates in the United States ranging from 3.4–17.7% (Breslau et al., 2004; Kessler et al., 1995), depending on sampling methods. The impact of the disorder on psychosocial functioning, quality of life, and other significant variables, such as suicidality, has been well documented (Sareen et al. 2007, Davidson, Hughes, Blaser, & George, 1991; Nepon, Belik, Bolton, & Sareen, 2010). Research examining the course of illness in PTSD has demonstrated its chronic nature. In the Harvard/Brown Anxiety Research Project (HARP), a prospective, longitudinal study of anxiety disorder course, the likelihood of full recovery from PTSD was 0.18 over a follow-up period of 5 years (Zlotnick et al., 1999), and 0.20 after 15 years of follow-up (Perez Benitez et al., 2012). Another report from the Primary Care Anxiety Project (PCAP), a prospective, longitudinal study of primary care patients with anxiety disorders using similar methodology as HARP, also found that the likelihood of full recovery from PTSD was 0.18 over a 2-year follow-up period (Zlotnick et al., 2004), and 0.38 at 5 year follow-up (Benitez et al, 2012). Although these studies highlight the chronic nature of PTSD, one key limitation to these studies is that both HARP and PCAP had very low rates of minority involvement; 97% of participants in HARP (Bruce et al., 2005) and 88% in PCAP (Francis et al., 2007) were non-Hispanic White, thus limiting our understanding of PTSD course in African American and Latino populations. To date, the limited available data on course of PTSD among minorities comes from the second phase of the HARP study (HARP-II), which specifically recruited large samples of African Americans and Latinos with anxiety disorders in order to help fill this gap in the literature (Weisberg, Beard, Dyck, & Keller, 2012). In a report on the 2-year course of PTSD in African Americans in HARP-II, Perez Benitez et al. (2014) found a rate of recovery in this sample of 0.10, demonstrating a chronic course of illness among this group. To date, no study has examined the prospective, longitudinal course of PTSD in a clinical sample of Latinos. While research on PTSD course in African Americans and Latinos is limited, somewhat more is known about the prevalence of PTSD in these groups.

Research examining PTSD prevalence in racial and ethnic minority samples has suggested that African Americans and Latino adults may develop PTSD at higher rates than White adults (Galea et al., 2004; Marshall, Schell, & Miles, 2009; Ortega & Rosenheck, 2000; Himle et al., 2009), though other findings have been mixed (Roberts, Gilman, Breslau, & Koenen, 2011; Asnaani, Richey, Dimaite, Hinton, & Hofmann, 2010). Additionally, research has also suggested that African Americans and Latinos may experience more severe PTSD symptoms (e.g., Ortega & Rosenheck, 2000; Roberts et al., 2011). A number of studies have offered evidence to help explain these racial and ethnic group differences in PTSD prevalence and severity, including socioeconomic factors that may limit their resources to cope with traumatic stressors (Roberts et al., 2011; Seng et al., 2011), increased exposure to assaultive violence (Roberts et al., 2011; Seng et al., 2011), stressors associated with displacement and immigration (Perez Benitez et al., 2014), cultural differences in emotional expression (Soto, Levenson, & Ebling, 2005), overrepresentation in poorer, disadvantaged, and higher crime communities (Cutrona et al., 2005), pervasive marginalization and “invisibility” (e.g., Franklin & Boyd-Franklin, 2000), higher rates of victim blaming following an assault (e.g., Dukes & Gaither, 2017), as well as increased rates of incarceration (Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2016), homelessness (U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, 2017), intimate partner violence (Catalano, 2012), and sex trafficking (Banks & Kyckelhahn, 2011). While these variables are likely influenced or moderated by structural factors affecting minorities in the United States, to date, very little research has attempted to directly assess the potential impact of perceived experiences with racism and discrimination in the development of PTSD in African Americans and Latinos.

Perceived discrimination has been defined as the perception or belief that one has been treated in a negative, aggressive, or unfair way by institutions and individuals, primarily as a function of personal characteristics, including race, ethnicity, skin color, gender, or other demographic factors (Williams & Mohammed, 2009). There has been very little research exploring the relationship between perceived discrimination experiences specific to minority groups and the developent of PTSD. However, perceived discrimination has been linked to poorer health outcomes (e.g., American Psychological Association, 2016), negative impacts on functioning and quality of life (see e.g., Lewis et al., 2015, for a review), and importantly, other forms of mental illness, suggesting its potential role as a risk factor for PTSD as well. For example, there is evidence that discrimination predicts increased depression symptoms after one year among African Americans (Brown et al., 2000), and was found to be associated with increased risk of mood and anxiety disorders among Latinos (Leong et al., 2013). While there have been very few studies specifically examining the association between perceived discrimination and PTSD diagnosis in clinical samples, some suggestive evidence of this relationship has been found in student and community samples, as well as studies of PTSD symptoms. In one study exploring perceived discrimination and PTSD symptoms in racial and ethnic minority groups, African Americans reported higher rates of perceived discrimination than Asians and Hispanics, and among those who reported perceived racism, were more likely to endorse lifetime PTSD than Asian Americans (Chou et al., 2012). A recent longitudinal study of a Hispanic/Latino college student sample who experienced racial/ethnic discrimination was found to be at increased risk for developing posttraumatic stress symptoms (PTSS; Cheng & Mallinckrodt, 2015). Further, in a Mexican-American adolescent sample, Flores et al. (2010) reported that racial and ethnic discrimination was also associated with worsening of posttraumatic stress symptoms, and another study employing a non-clinical sample revealed that perceived discrimination was significantly related to trauma-related symptoms in the Black and Asian-American undergraduate samples, but not in a White undergraduate sample after controlling for general life stressors (Pieterse et al., 2010). Thus, while some evidence exists to suggest that perceived discrimination may increase risk or exacerbate symptoms of PTSD and other forms of mental illness generally, no data has found perceived discrimination to be a unique predictor of PTSD diagnosis.

The Current Study

HARP-II is the first prospective, observational longitudinal study of anxiety disorders to include large, targeted samples of African Americans and Latinos in addition to Whites, and allows for a unique opportunity to explore questions about course and the role of sociocultural experiences in the clinical presentation of psychiatric disorders among these minority groups.

The aims of the current study were to: 1) explore the 5-year clinical course of PTSD in African American and Latino adults, extending our previous 2-year findings in African Americans, and presenting the first prospective, longitudinal study of PTSD in Latinos; 2) to examine the relationship between perceived experiences with racial and ethnic discrimination and the presence of PTSD among African American and Latino adults, and; 3) to examine the association between perceived experiences with discrimination and overall functioning among these groups. Specifically, we predicted that the 5-year course of PTSD in these samples would be poor, providing needed evidence of chronicity in minority populations. Second, we predicted that frequency of perceived discrimination experiences would predict PTSD diagnostic status in a clinical sample, and we explored whether this relationship was unique to PTSD, or if perceived discrimination served as a general risk factor for many forms of anxiety and mood disorders. Finally, we predicted that frequency of perceived discrimination experiences would be inversely related to measures of psychosocial and clinical functioning.

Method

Data for this study were obtained from the African American and Latino samples of HARP-II, who had been diagnosed with anxiety disorders based on DSM-IV criteria (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). Some participants were recruited from referrals from site collaborators and associated treatment providers. Others were self-referred from ads on the internet and in newspapers. HARP-II was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Brown University and Butler Hospital. Prior to enrollment in the study, all participants provided written informed consent, and were compensated for their participation. Additional methological details are presented elsewhere (Weisberg, Beard, Dyck, & Keller, 2012).

Participants and Procedure

The total number of participants in the minority sample were 166 African Americans and 134 Latinos from the age of 18 or older drawn from the larger HARP-II sample, including 93 African Americans and 61 Latinos with a lifetime diagnosis of PTSD, who represent the focus of this study. Inclusion criteria for HARP-II included being diagnosed with one or more of the following index anxiety disorders: Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD), Social Anxiety Disorder (SAD), Panic Disorder (PD) and Panic Disorder with Agoraphobia (PDA), as assessed by the structured clinical interview for DSM-IV (SCID-IV; First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 1996). Participants were excluded from the study if they were diagnosed with schizophrenia, had an organic mental disorder, or were suffering from active psychosis. Participants completed in-person assessments at baseline, and in-person or telephone follow-up interviews at 6 months, 1 year, and then yearly up to 5 years post-intake.

Measures

Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis-I Disorders (SCID-IV; First et al., 1996).

The SCID was used to assess the lifetime and current history of axis-I disorders. It is a diagnostic, semi-structured, clinician administered interview, and was employed at intake. Inter-rater reliability of the SCID has been found to be good to very high (Cohen’s kappa .67 – .85) (Vazquez, Sandler, Interian, & Feldman, 2016; Ventura, Liberman, Green, Shaner, & Mintz, 1998) with excellent diagnostic accuracy. Alegria et al. (2009) found the SCID to have acceptable concordance rates with other diagnostic interviews in a Latino sample.

Longitudinal Interval Follow-Up Evaluation (LIFE; Keller et al., 1987).

The LIFE is an interview that is used to assess precise information on anxiety disorder symptoms, such as psychosocial functioning and treatment status, and is, furthermore, used during follow-up period to assess disorder course. To indicate the severity of psychiatric symptoms, the LIFE uses a 6-point psychiatric status rating (PSR) scale. A PSR of 1 indicates an asymptomatic patient, a PSR of 2 indicates that the patient has some mild symptoms, and a PSR of 3 and 4 indicates that the participant does not meet full DSM-IV criteria for the disorder but still shows notable symptoms and impairment to a mild or moderate degree. A PSR of 5 or 6 indicates that that patient meets full DSM-IV criteria for the disorder with either moderate or severe functional impairment. The LIFE uses a change point method to extract participants’ reports of symptom levels to relevant life events (e.g., holidays, birthdays), producing weekly ratings of psychiatric symptom severity. In the present study, recovery was defined as at least a period of eight weeks at a PSR of 1 or 2. Inter-rater reliability and long-term test-retest reliability on PSR ratings for LIFE have been found to be good to excellent for all anxiety disorders and MDD (Warshaw, Keller, & Stout, 1994) in HARP-I. Inter-rater agreement on PSR ratings in HARP-II was found to be 97% for SAD, 88% for GAD, 65% for PD and 87% for MDD. In addition, the LIFE is also used to gather information on global social adjustment, life satisfaction, and global assessment of functioning (GAF). Inter-rater reliability for these items has been found to be good, with intra-class correlation coefficients ranging from .59 to .91 (Keller et al., 1987).

Demographics questionnaire.

This measure, created for the current study, is used to obtain information on the participant’s self-reported race and ethnicity, as well as age, gender, employment, education, marital status, language fluency, sexual orientation, family composition, and income/economic support. With respect to ethnicity, participants are asked to self-identify as Hispanic or Latino or not, and with respect to race, participants are asked whether they identify as White or Caucasian, Black or African American, Asian, American Indian, Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, or Other. Finally, participants are asked to indicate which of the following they feel best describes them; Black or African American, Hispanic or Latino, Other, and Cannot Say/Cannot Decide with an option for the participant to provide their own descriptive terminology.

Everyday Discrimination Scale (EDS; Williams, Yu, Jackson, & Anderson, 1997; Williams & Mohammed, 2009).

The EDS is a nine-item scale that assesses perceptions of experiencing discrimination in one’s everyday life, and measures the frequency with which participants encounter the types of discrimination listed on a six-point Likert scale, ranging from “Never” to “Almost Every Day”. The EDS has shown good psychometric properties (Cronbach’s alpha = .79 for Latinos, .86 for African Americans; test-retest reliability = .70; Krieger et al., 2005), and has been used in several racial and ethnic populations in the U.S. and internationally (Williams et al., 2008). In the current study, a rater-administered version of the EDS was used which included 3 additional questions that ask participants directly about the degree to which they are disliked because of their race/ethnicity, how often they are treated unfairly due to their race/ethnicity overall, and how often they witness friends being treated unfairly because of their race/ethnicity (Krieger et al., 2005). This modification was employed in the National Latino and Asian American Study and has demonstrated good psychometric properties in minority samples (Alegria et al., 2004). Cronbach’s alpha for these 3 items in the current study was .86 for the African American sample, .81 for the Latino sample, and .84 for the combined sample. Data for this measure was available for a subset of the sample due to its late addition to the assessment battery (see Table 5).

Table 5.

Experiences with Everyday Discrimination Reported by Participants with PTSD.

| Total Sample (N = 60) |

African American (N = 32) |

Latino American (N = 28) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| You are treated with less courtesy than other people | ||||||

| Almost Everyday | 5 | 8.33 | 2 | 6.25 | 3 | 10.71 |

| At Least Once a Week | 8 | 13.33 | 3 | 9.38 | 5 | 17.86 |

| A Few Times a Month | 12 | 20.00 | 8 | 25.00 | 4 | 14.29 |

| A Few Times a Year | 15 | 25.00 | 7 | 21.88 | 8 | 28.57 |

| Less Than Once a Year | 13 | 21.67 | 8 | 25.00 | 5 | 17.86 |

| Never | 7 | 11.67 | 4 | 12.50 | 3 | 10.71 |

| You are treated with less respect than other people | ||||||

| Almost Everyday | 5 | 8.33 | 2 | 6.25 | 3 | 10.71 |

| At Least Once a Week | 10 | 16.67 | 4 | 12.50 | 6 | 21.43 |

| A Few Times a Month | 15 | 25.00 | 8 | 25.00 | 7 | 25.00 |

| A Few Times a Year | 13 | 21.67 | 8 | 25.00 | 5 | 17.86 |

| Less Than Once a Year | 11 | 18.33 | 7 | 21.88 | 4 | 14.29 |

| Never | 6 | 10.00 | 3 | 9.38 | 3 | 10.71 |

| You receive poorer service than other people at restaurants or stores | ||||||

| Almost Everyday | 10 | 16.67 | 5 | 15.63 | 5 | 17.86 |

| At Least Once a Week | 19 | 31.67 | 9 | 28.13 | 10 | 35.71 |

| A Few Times a Month | 17 | 28.33 | 13 | 40.63 | 4 | 14.29 |

| A Few Times a Year | 9 | 15.00 | 2 | 6.25 | 7 | 25.00 |

| Less Than Once a Year | 4 | 6.67 | 3 | 9.38 | 1 | 3.57 |

| Never | 1 | 1.67 | 0 | 0.00 | 1 | 3.57 |

| People act as if they think you are not smart | ||||||

| Almost Everyday | 9 | 15.00 | 4 | 12.50 | 5 | 17.86 |

| At Least Once a Week | 12 | 20.00 | 5 | 15.63 | 7 | 25.00 |

| A Few Times a Month | 12 | 20.00 | 7 | 21.88 | 5 | 17.86 |

| A Few Times a Year | 12 | 20.00 | 5 | 15.63 | 7 | 25.00 |

| Less Than Once a Year | 7 | 11.67 | 4 | 12.50 | 3 | 10.71 |

| Never | 8 | 13.33 | 7 | 21.88 | 1 | 3.57 |

| People act as if they are afraid of you | ||||||

| Almost Everyday | 11 | 18.33 | 4 | 12.50 | 7 | 25.00 |

| At Least Once a Week | 12 | 20.00 | 6 | 18.75 | 6 | 21.43 |

| A Few Times a Month | 14 | 23.33 | 11 | 34.38 | 3 | 10.71 |

| A Few Times a Year | 9 | 15.00 | 3 | 9.38 | 6 | 21.43 |

| Less Than Once a Year | 7 | 11.67 | 5 | 15.63 | 2 | 7.14 |

| Never | 7 | 11.67 | 3 | 9.38 | 4 | 14.29 |

| People act as if they think you are dishonest | ||||||

| Almost Everyday | 11 | 18.33 | 5 | 15.63 | 6 | 21.43 |

| At Least Once a Week | 21 | 35.00 | 12 | 37.50 | 9 | 32.14 |

| A Few Times a Month | 13 | 21.67 | 7 | 21.88 | 6 | 21.43 |

| A Few Times a Year | 8 | 13.33 | 3 | 9.38 | 5 | 17.86 |

| Less Than Once a Year | 6 | 10.00 | 5 | 15.63 | 1 | 3.57 |

| Never | 1 | 1.67 | 0 | 0.00 | 1 | 3.57 |

| People act as if you are not as good as they are | ||||||

| Almost Everyday | 5 | 8.47 | 2 | 6.25 | 3 | 11.11 |

| At Least Once a Week | 12 | 20.34 | 6 | 18.75 | 6 | 22.22 |

| A Few Times a Month | 17 | 28.81 | 12 | 37.50 | 5 | 18.52 |

| A Few Times a Year | 11 | 18.64 | 4 | 12.50 | 7 | 25.93 |

| Less Than Once a Year | 8 | 13.56 | 4 | 12.50 | 4 | 14.81 |

| Never | 6 | 10.17 | 4 | 12.50 | 2 | 7.41 |

| You are called names or insulted | ||||||

| Almost Everyday | 15 | 25.00 | 8 | 25.00 | 7 | 25.00 |

| At Least Once a Week | 13 | 21.67 | 9 | 28.13 | 4 | 14.29 |

| A Few Times a Month | 16 | 26.67 | 9 | 28.13 | 7 | 25.00 |

| A Few Times a Year | 5 | 8.33 | 2 | 6.25 | 3 | 10.71 |

| Less Than Once a Year | 4 | 6.67 | 1 | 3.13 | 3 | 10.71 |

| Never | 7 | 11.67 | 3 | 9.38 | 4 | 14.29 |

| You are threatened or harassed | ||||||

| Almost Everyday | 15 | 25.42 | 8 | 25.00 | 7 | 25.93 |

| At Least Once a Week | 22 | 37.29 | 13 | 40.63 | 9 | 33.33 |

| A Few Times a Month | 12 | 20.34 | 6 | 18.75 | 6 | 22.22 |

| A Few Times a Year | 3 | 5.08 | 1 | 3.13 | 2 | 7.41 |

| Less Than Once a Year | 3 | 5.08 | 1 | 3.13 | 2 | 7.41 |

| Never | 4 | 6.78 | 3 | 9.38 | 1 | 3.70 |

| How often do people dislike you because you are of your racial or ethnic group? | ||||||

| Often | 7 | 11.67 | 5 | 15.63 | 2 | 7.14 |

| Sometimes | 22 | 36.67 | 10 | 31.25 | 12 | 42.86 |

| Rarely | 18 | 30.00 | 9 | 28.13 | 9 | 32.14 |

| Never | 13 | 21.67 | 8 | 25.00 | 5 | 17.86 |

| How often do people treat you unfairly because you are of your racial or ethnic group? | ||||||

| Often | 5 | 8.33 | 3 | 9.38 | 2 | 7.14 |

| Sometimes | 29 | 48.33 | 17 | 53.13 | 12 | 42.86 |

| Rarely | 18 | 30.00 | 8 | 25.00 | 10 | 35.71 |

| Never | 8 | 13.33 | 4 | 12.50 | 4 | 14.29 |

| How often have you seen friends treated unfairly because they are of your racial or ethnic group? | ||||||

| Often | 19 | 31.67 | 9 | 28.13 | 10 | 35.71 |

| Sometimes | 26 | 43.33 | 18 | 56.25 | 8 | 28.57 |

| Rarely | 11 | 18.33 | 5 | 15.63 | 6 | 21.43 |

| Never | 4 | 6.67 | 0 | 0.00 | 4 | 14.29 |

Notes. PTSD = Posttraumatic Stress Disorder.

Treatment history questionnaire.

This measure is used to assess each participant’s psychiatric treatment history, for example type and frequency of treatments received. This measure has been shown to have high inter-rater reliability (Keller et al., 1987). Reliability coefficients were nearly perfect (kappas ranged from .91 – 1.00) for all treatment modalities except atypical antidepressants with kappas in the range of .66 – .86, which is still indicative of good to substantial agreement (Landis & Koch, 1977).

Rater Training and Supervision

Assessors with a bachelor’s or master’s degree in psychology, or another related field, conducted the interviews. The interviewers undergo a comprehensive training program, beginning with watching training tapes as well as studying instruments. They then participate in 1–2 day didactic sessions and analyze videos of experienced interviewers conducting interviews. The next stage in the training program is for new interviewers to directly observe experienced interviewers. Later, they conduct their own interviews under direct observation by training supervisors as well as being video or audio-recorded for close analysis by training supervisors. New interviewers are certified to collect data independently only after they have conducted at least three interviews wherein they are observed by training supervisors that have judged them as competent. Even after obtaining certification, all clinical interviews are still closely supervised. At a weekly meeting, each diagnosis for each case enrolled in the study are reviewed by HARP-II clinical staff. Ratings from each interviewer are monitored by the training supervisor that provides feedback from periodic video or audio recordings.

Statistical Analyses

Data were analyzed using SPSS Version 20.0. Frequencies, percentages, and/or means and standard deviations were calculated for all descriptive variables. Kaplan-Meier life tables and standard survival analysis techniques were used, and data for participants who were lost to follow-up were censored. A statistical comparison of survival rates was performed to examine the possible role of key demographic and treatment variables in probability of PTSD remission. Binary logistic regression was conducted to test perceived discrimination experiences as predictors of PTSD diagnostic status, and correlations were conducted to examine the relationship between perceived discrimination experiences and functioning.

Results

Demographic, Clinical, and Functional Characteristics

Demographics of the African American and Latino PTSD samples are presented in Table 1, clinical characteristics and treatment utilization data are presented in Table 2, functional characteristics are presented in Table 3, and types of traumatic events reported by participants with PTSD are presented in Table 4.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Participants with PTSD at Intake.

| Variable | Total Sample (N = 154) |

African American (N = 93) |

Latino American (N = 61) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 40 | 25.97 | 27 | 29.03 | 13 | 21.31 |

| Female | 114 | 74.03 | 66 | 70.97 | 48 | 78.69 |

| Marital Status | ||||||

| Single | 86 | 55.84 | 59 | 63.44 | 27 | 44.26 |

| Married | 17 | 11.04 | 8 | 8.60 | 9 | 14.75 |

| Widowed | 6 | 3.90 | 2 | 2.15 | 4 | 6.56 |

| Divorced/Separated | 45 | 29.22 | 24 | 25.81 | 21 | 34.43 |

| Education | ||||||

| High School or Less | 71 | 46.10 | 40 | 43.01 | 31 | 50.82 |

| Some College or More | 83 | 53.90 | 53 | 56.99 | 30 | 49.18 |

| Employment | ||||||

| Employed | 40 | 25.97 | 24 | 25.81 | 16 | 26.23 |

| Unemployed | 114 | 74.03 | 69 | 74.19 | 45 | 73.77 |

| Disability Status | ||||||

| Physical Disability | 36 | 23.38 | 27 | 29.03 | 9 | 14.75 |

| Psychiatric Disability | 55 | 35.71 | 34 | 36.56 | 21 | 34.43 |

| Annual Income | ||||||

| <$5,000/year | 20 | 12.99 | 17 | 18.28 | 3 | 4.92 |

| $5,000 - $19,999 | 65 | 42.21 | 38 | 40.86 | 27 | 44.26 |

| $20,000 - $34,999 | 24 | 15.58 | 13 | 13.98 | 11 | 18.03 |

| $35,000 - $49,999 | 8 | 5.19 | 6 | 6.45 | 2 | 3.28 |

| $50,000 - $64,999 | 6 | 3.90 | 2 | 2.15 | 4 | 6.56 |

| $65,000 - $89,999 | 2 | 1.30 | 2 | 2.15 | 0 | 0.00 |

| $90,000 - $119,999 | 1 | 0.65 | 1 | 1.08 | 0 | 0.00 |

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| Age at Intake | 40.60 | 10.60 | 41.86 | 10.77 | 38.67 | 10.13 |

Notes. PTSD = Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Annual Income data are missing for 28 participants. Disability Status indicates that the participant is receiving disability benefits.

Table 2.

Clinical Characteristics and Treatment History of Participants with PTSD at Intake.

| Variable | Total Sample (N = 154) |

African American (N = 93) |

Latino American (N = 61) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| HARP-II Index Disorders Current at Intake | ||||||

| Generalized Anxiety Disorder | 77 | 50.00 | 47 | 50.54 | 30 | 49.18 |

| Panic Disorder with Agoraphobia | 74 | 48.05 | 48 | 51.61 | 26 | 42.62 |

| Panic Disorder without Agoraphobia | 12 | 7.79 | 7 | 7.53 | 5 | 8.20 |

| Social Anxiety Disorder | 76 | 49.35 | 46 | 49.46 | 30 | 49.18 |

| Other Comorbid Disorders Current at Intake | ||||||

| Specific Phobia | 73 | 47.40 | 45 | 48.39 | 28 | 45.90 |

| Anxiety NOS | 3 | 1.95 | 2 | 2.15 | 1 | 1.64 |

| Obsessive Compulsive Disorder | 48 | 31.17 | 26 | 27.96 | 22 | 36.07 |

| Major Depressive Disorder | 91 | 59.09 | 50 | 53.76 | 41 | 67.21 |

| Any Mood Disorder | 98 | 63.64 | 54 | 58.06 | 44 | 72.13 |

| Any Eating Disorder | 11 | 7.14 | 3 | 3.23 | 8 | 13.11 |

| Alcohol Abuse | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 |

| Alcohol Dependence | 7 | 4.55 | 5 | 5.38 | 2 | 3.28 |

| Drug Abuse | 1 | 0.65 | 0 | 0.00 | 1 | 1.64 |

| Drug Dependence | 8 | 5.19 | 6 | 6.45 | 2 | 3.28 |

| Lifetime Treatment Utilization | ||||||

| Individual Therapy | 134 | 87.01 | 81 | 87.10 | 53 | 86.89 |

| Group Therapy | 63 | 40.91 | 42 | 45.16 | 21 | 34.43 |

| Family Therapy | 34 | 22.08 | 18 | 19.35 | 16 | 26.23 |

| Medication | 125 | 81.17 | 72 | 77.42 | 53 | 86.89 |

| Self-help | 55 | 35.71 | 39 | 41.94 | 16 | 26.23 |

| Day Treatment | 31 | 20.13 | 19 | 20.43 | 12 | 19.67 |

| Inpatient | 70 | 45.45 | 44 | 47.31 | 26 | 42.62 |

| Residential | 43 | 27.92 | 26 | 27.96 | 17 | 27.87 |

| Treatment Utilization Current at Intake | ||||||

| Individual Therapy | 67 | 43.51 | 38 | 40.86 | 29 | 47.54 |

| Group Therapy | 17 | 11.04 | 8 | 8.60 | 9 | 14.75 |

| Family Therapy | 3 | 1.95 | 0 | 0.00 | 3 | 4.92 |

| Medication | 84 | 54.55 | 43 | 46.24 | 41 | 67.21 |

| Self-help | 27 | 17.53 | 23 | 24.73 | 4 | 6.56 |

| Day Treatment | 3 | 1.95 | 2 | 2.15 | 1 | 1.64 |

| Inpatient | 3 | 1.95 | 1 | 1.08 | 2 | 3.28 |

| Residential | 8 | 5.19 | 5 | 5.38 | 3 | 4.92 |

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| Age of PTSD Onset | 17.84 | 12.36 | 18.17 | 12.74 | 17.33 | 11.84 |

| Number of Lifetime Axis-I Comorbid Disorders | 5.89 | 1.68 | 5.94 | 1.72 | 5.82 | 1.63 |

| Number of Comorbid Axis-I Disorders Current at Intake | 3.97 | 1.66 | 3.92 | 1.69 | 4.05 | 1.63 |

Notes. PTSD = Posttraumatic Stress Disorder.

Table 3.

Functional Characteristics of Participants with PTSD at Intake.

| Total Sample (N = 150) |

African American (N = 93) |

Latino American (N = 57) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Global Social Adjustment | ||||||

| Very Good | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 |

| Good | 5 | 3.33 | 5 | 5.38 | 0 | 0.00 |

| Fair | 28 | 18.67 | 17 | 18.28 | 11 | 19.30 |

| Poor | 74 | 49.33 | 51 | 54.84 | 23 | 40.35 |

| Very Poor | 43 | 28.67 | 20 | 21.51 | 23 | 40.35 |

| Overall Life Satisfaction | ||||||

| Very Good | 2 | 1.33 | 1 | 1.08 | 1 | 1.75 |

| Good | 15 | 10.00 | 11 | 11.83 | 4 | 7.02 |

| Fair | 78 | 52.00 | 51 | 54.84 | 27 | 47.37 |

| Poor | 46 | 30.67 | 23 | 24.73 | 23 | 40.35 |

| Very Poor | 9 | 6.00 | 7 | 7.53 | 2 | 3.51 |

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| Global Assessment of Functioning | 48.49 | 6.73 | 48.72 | 6.90 | 48.11 | 6.47 |

Notes. PTSD = Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Data were missing for 4 Latino participants for Global Social Adjustment, Overall Life Satisfaction, and GAF.

Table 4.

PTSD-Associated Traumatic Events Reported by Participants.

| Total Sample (N = 154) |

African American (N = 93) |

Latino American (N = 61) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Military Combat/Service in a War Zone | 3 | 1.95 | 3 | 3.23 | 0 | 0.00 |

| Serious Accident (car, work, etc.) | 4 | 2.60 | 4 | 4.30 | 0 | 0.00 |

| Unwanted Sexual Contact | 23 | 14.94 | 14 | 15.05 | 9 | 14.75 |

| Rape (Forced Sexual Intercourse) | 51 | 33.12 | 31 | 33.33 | 20 | 32.79 |

| Attack/Assault with a Weapon | 24 | 15.58 | 11 | 11.83 | 13 | 21.31 |

| Attack/Assault without a weapon | 22 | 14.29 | 9 | 9.68 | 13 | 21.31 |

| Other Situations Where Feared Death or Serious Injury May Occur | 3 | 1.95 | 3 | 3.23 | 0 | 0.00 |

| Seeing Someone Seriously Injured or Violently Killed | 22 | 14.29 | 17 | 18.28 | 5 | 8.20 |

| Other Extraordinary Stressful Situation/Event | 2 | 1.30 | 1 | 1.08 | 1 | 1.64 |

Notes. PTSD = Posttraumatic Stress Disorder.

Clinical Course of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

Course of PTSD in African Americans.

Kaplan-Meier survival estimates showed that African American participants with PTSD had a 0.35 probability of achieving full recovery from their intake episode during 5 years of follow-up (N = 64). Comparisons of survival rates found a significant difference between those African Americans with PTSD who were employed vs. those who were unemployed, χ2 (1) 4.00, p < .045, such that those participants who were currently employed at intake experienced a remission rate of 0.75, compared to those unemployed at intake, who remitted at a rate of 0.25. A significant difference in remission rates for PTSD among African Americans was also found for income, χ2 (1) 6.53 p < .011, with a remission rate for those earning less than $20,000 per year of 0.23, compared to those earning greater than $20,000 per year (0.76 remission rate). No significant differences in survival rates were found for receiving any mental health treatment at intake (yes/no), χ2 (1) 0.49, p =.486, or education level (at least high school vs. greater than high school; χ2 (1) 0.04, p =.844).

Course of PTSD in Latinos.

Kaplan-Meier survival estimates showed that Latino American participants with PTSD had a 0.15 probability of achieving full recovery from their intake episode during 5 years of follow-up (N= 35). Comparisons of survival rates found no significant differences in remission rates between those Latinos with PTSD for employment, χ2 (1) 0.00, p = .955, income, χ2 (1) 0.03 p = .867, receiving any mental health treatment at intake (yes/no), χ2 (1) 0.12, p =.731, or education, χ2 (1) 0.62, p =.432.

A comparision of survival curves between the African American and Latino samples with PTSD revealed no significant differences in probability of recovery between the two groups over 5 years of follow-up (χ2 (1) 3.55, p =.060; see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Cumulative Probability Estimates of Recovery from PTSD Over 5 Years of Follow-Up.

Experiences With Discrimination: PTSD Status and Functioning

A summary of perceived discrimination reported on the EDS is presented in Table 5 for the African American and Latino samples. The most frequently reported experiences with discrimination in the African American PTSD sample were seeing friends treated unfairly because they are of your racial/ethnic group sometimes (56.25%), personally being treated unfairly because of race/ethnicity sometimes (53.13%), and being threatened or harassed, with 40.63% reporting experiencing this at least once a week. In the Latino sample, the most frequently reported discrimination experiences were being disliked because of your race/ethnicity sometimes (42.86%), being treated unfairly because of race/ethnicity sometimes (42.86%), and receiving poorer service than others in restaurants and stores at least once a week (35.71%).

To test the hypothesis that experiences with racial and ethnic discrimination may predict PTSD status, binary logistic regressions were conducted with PTSD diagnostic status as the binary criterion variable (yes/no), and available participant reports of the 12 types of discrimination experiences assessed on the EDS as predictors. In the whole sample (with and without PTSD), logistic regression analyses revealed that experiences with discrimination significantly predicted a PTSD diagnosis, but did not significantly predict any other anxiety or mood disorder (overall model χ2 (12) = 37.40, −2 log likelihood = 117.72, Cox and Snell R2 = .284, Nagelkerke R2 = .379, p < .001, overall correct classification rate = 77.7%), demonstrating that between 28.4% and 37.9% of the variance in PTSD diagnostic status could be explained by discrimination experiences. In the African American sample specifically, significant predictors of PTSD status included being called names and/or insulted (b = −0.84, Wald χ2 (1) = 4.46,p < .035; odds ratio = 0.43, 95% CI = 0.20 − 0.94, being threatened or harassed (b = 1.52, Wald χ2 (1) = 7.16, p < .007; odds ratio = 4.55, 95% CI = 1.50 – 13.80), and witnessing friends treated unfairly because they are of your racial or ethnic group (b = −1.99, Wald χ2 (1) = 10.75, p < .001; odds ratio = 0.14, 95% CI = 0.04 – 0.45). In the Latino sample, being treated as though you were not as smart as others because of your ethnicity was a significant predictor of PTSD status (b = −1.52, Wald χ2 (1) = 7.00, p < .008; odds ratio = 0.22, 95% CI = 0.07 – 0.68).

In addition to the role that experiences with discrimination may play as a risk factor for the development of PTSD, these experiences may also be related to other dimensions of functioning. To test this, correlations between frequency of discrimination experiences and Global Social Adjustment (GSA), Overall Life Satisfaction (OLS), GAF, and lifetime and current rates of comorbidity were conducted. Overall, several significant correlations supported our prediction that perceived discrimination experiences would be associated with poorer functioning (see Tables 6 and 7). In the African American sample, for example, a number of strong relationships between the frequency of experiences with discrimination and domains of functioning were found, including higher number of comorbid disorders related to the frequency of being treated with less courtesy because of your race (r = .432, p < .01) and people thinking you are not as smart as they are (r = .475, p < .01); poorer OLS related to people thinking you are not as good as they are (r = .437, p < .01) and others being afraid of you (r = .346, p < .01); and lower GSA related to others thinking you are not as good as they are (r = .333, p < .01). Similarly in the Latino sample, many significant relationships were found, including poorer OLS being strongly related to people thinking you are not as good as they are (r = .443, p < .01), being threatened and harassed (r = .398, p < .01), and being treated with less courtesy (r = .417, p < .01); lower GAF scores and the frequency of receiving poorer service (r = .501, p < .01), and others being afraid of you and number of comorbid disorders (r = .617, p < .01).

Table 6.

Correlations Between Everyday Experiences with Discrimination and Functioning in the African American Sample.

| Variable | Global Social Adjustment | Overall Life Satisfaction | Global Assessment of Functioning | Number of Comorbid Diagnoses (Lifetime) | Number of Comorbid Diagnose (Current) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Treated with less courtesy | .260* | .190 | −.262* | .340** | .432** |

| 2. Treated with less respect | .268* | .228 | −.274* | .386** | .396** |

| 3. Received poorer service | .111 | .203 | −.150 | .202 | .326** |

| 4. They think you are not as smart | .260* | .316* | −.210 | .340** | .475** |

| 5. They are afraid of you | .212 | .346** | −.181 | .264* | .230 |

| 6. They think you are dishonest | .073 | .155 | −.060 | .249* | .134 |

| 7. You are not as good as they are | .333** | .437** | −.283* | .311* | .422** |

| 8. You are called names or insulted | .268* | .222 | −.173 | .227 | .304* |

| 9. You are threatened or harassed | .141 | .097 | −.090 | .191 | .081 |

| 10. How often do people dislike you? | −.283* | −.126 | .213 | −.215 | −.328** |

| 11. How often are you treated unfairly? | −.243 | −.198 | .110 | −.094 | −.219 |

| 12. How often are friends treated unfairly? | −.230 | −.125 | .197 | −.277* | −.153 |

Notes.

= p < .0.05,

= p < .0.01.

Higher scores on Global Social Adjustment and Life Satisfaction indicate poorer functioning in these domains. Higher scores on Everyday Experiences with Discrimination items 1–9 indicate more frequent discrimination experiences, higher scores on items 10–12 indicate less frequent experiences.

Table 7.

Correlations Between Everyday Experiences with Discrimination and Functioning in the Latino Sample.

| Variable | Global Social Adjustment | Overall Life Satisfaction | Global Assessment of Functioning | Number of Comorbid Diagnoses (Lifetime) | Number of Comorbid Diagnose (Current) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Treated with less courtesy | .241 | .417** | −.360* | .322* | .364** |

| 2. Treated with less respect | .175 | .391** | −.331* | .235 | .259 |

| 3. Received poorer service | .342* | .278 | −.501** | .402** | .485** |

| 4. They think you are not as smart | .241 | .306* | −.313* | .340* | .440** |

| 5. They are afraid of you | .357* | .116 | −.451** | .522** | .617** |

| 6. They think you are Dishonest | .219 | .357* | −.305* | .246 | .213 |

| 7. You are not as good as they are | .368* | .443** | −.361* | .293* | .408** |

| 8. You are called names or insulted | .305* | .361* | −.434** | .260 | .341* |

| 9. You are threatened or harassed | .314* | .398** | −.347* | .301* | .355** |

| 10. How often do people dislike you? | −.373* | −.350* | .418** | −.255 | −.270 |

| 11. How often are you treated unfairly? | −.330* | −.362* | .387* | −.281* | −.417** |

| 12. How often are friends treated unfairly? | −.248 | −.304 | .367* | −.168 | −.279* |

Notes.

= p < .0.05,

= p < .0.01.

Higher scores on Global Social Adjustment and Life Satisfaction indicate poorer functioning in these domains. Higher scores on Everyday Experiences with Discrimination items 1–9 indicate more frequent discrimination experiences, higher scores on items 10–12 indicate less frequent experiences.

Discussion

The aims of the current study were to present longitudinal course findings in PTSD in a sample of African Americans and Latinos, as well as to explore the relationship between perceived experiences with discrimination and PTSD diagnostic status and functioning in a well characterized clinical sample of adults with PTSD. The HARP-II study is the first prospective, observational study on the course of PTSD among African Americans and Latinos with anxiety disorders, and therefore represents a unique and important step toward an improved understanding of these factors in underrepresented populations. Overall, our predictions were supported by the available data, providing evidence to support the need for additional research at the intersection of race, ethnicity, discrimination, and trauma in minorities.

Specifically, we predicted that the course of PTSD in the current sample would be poor, and survival analyses revealed 5-year remission rates of 0.38 and 0.10 in African Americans and Latinos, respectively, demonstrating that the vast majority of these individuals remained chronically ill during the follow-up period. These findings are especially interesting in light of the high rates of treatment utilization reported in the current sample, with 54.55% of African Americans and 67.21% of Latinos receiving current treatment at study intake, and a lifetime treatment utilization rate of 94.81% for the whole sample. Previous studies examining PTSD in African American and Latino samples have suggested that poorer prognosis and greater symptom severity may be due to treatment underutilization (Alegria et al., 2002; Vega, Kolody, Aguilar-Gaxiola, & Catalano, 1999; Wang et al., 2005; Roberts et al., 2011), however, in the current sample, probability of recovery was low despite relatively high treatment utilization rates. The current study did not, however, assess quality of that treatment, nor did we collect data on the race and ethnicity of treatment providers – key factors that may be related to recovery rates. For African Americans, employment and income predicted recovery from PTSD, indicating that socioeconomic factors may be directly involved in maintaining the disorder, possibly by limiting access to quality mental health care or exacerbating the severity of mental illness, with unemployment and low income adding additional stressors that impact resilience. Furthermore, a chronic course of illness despite high rates of treatment utilization illustrates the importance of exploring additional factors unique to the experiences of African Americans and Latinos that may help to elucidate variables above and beyond access to care that can explain these poor outcomes. For example, Latinos endorse more stigmatizing attitudes toward mental illness than other groups (Corrigan & Watson, 2007), encounter stressors related to cultural adaptation, immigration, and language barriers (Perez-Benitez et al., 2014), and exhibit differences in emotional expression (Soto, Levenson, & Ebling, 2005), all of which may contribute to poor recovery. Examining the ways in which the sociocultural experiences of minority populations may exacerbate PTSD symptoms will likely prove to be a promising avenue for further study. Our findings speak to the urgent need to develop culturally competent trauma treatments adapted to take sociocultural factors into account, as the availability and empirical evidence for such interventions for trauma are very limited (Sue, Zane, Nagayama Hall, & Berger, 2009; Brown, 2008), although a growing number of important models for accomplishing such adaptations have been proposed (e.g., Zayfert, 2008; Comas-Diaz, 2006).

We also explored the relationship between perceived experiences with discrimination and PTSD diagnostic status, as well as psychosocial and clinical functioning. As predicted, frequency of experiences with discrimination was significantly correlated with social adjustment (GSA), quality of life (OLS), overall functioning (GAF), and comorbidity rates, indicating the substantial, cumulative impact that incidents of discrimination can have on one’s wellbeing. Logisic regression analyses found that perceived discrimination uniquely predicted PTSD diagnostic status, and no other anxiety or mood disorder. Although causality cannot be determined in the current sample, this finding nonetheless suggests that discrimination experiences may be a possible risk factor for the development of PTSD, therefore we recommend that careful consideration and assessment of broader sociocultural stressors should be an integral component of the diagnostic assessment and treatment process. It is also important to highlight the high frequency with which participants reported experiences with discrimination in the current study, with substantial proportions (i.e., up to 56.25% in the African American sample) indicating that they have encountered these experiences on a weekly basis. This finding underscores the on-going nature of discrimination in the lives of African American and Latino adults, and points to the potential negative impact on PTSD recovery as a result of these on-going stressors. Understanding the ways in which perceived discrimination may be impacting one’s risk for the development and maintenance of PTSD can lead to the incorporation of culturally sensitive treatment strategies that may incrementally improve outcome and functioning in African American and Latino patients.

Another potential implication of this finding is that for some African American and Latino individuals, experiences with discrimination may be traumatic in-and-of themselves. Trauma is described in the current version of the DSM as “exposure to actual or threatened death, serious injury, or sexual violence” (APA, 2013, pp. 271, Criterion A). There has been a considerable debate in the literature on what constitutes trauma (Boals & Schuettler, 2009; Gold, Marx, Soler-Baillo, & Sloan, 2005; Long et al., 2008) and creating a general definition has proven difficult (Weathers & Keane, 2007). The key characteristic of a traumatic event in the context of PTSD seems to be a perception of imminent threat toward life (Long et al., 2008; Weathers & Keane, 2007). However, a number of studies have demonstrated that experiences that do not strictly meet Criterion A can, nevertheless, result in post-traumatic stress symptoms (PTSS) or even a full diagnosis of PTSD. Some researchers have described experiences of racism, discrimination, rejection, or ridicule as constituting a form of trauma (Carter, 2007). Such models suggest that individuals can develop PTSS in response to discrimination and interpersonal trauma, even though such experiences do not directly conform to current DSM definitions of trauma. Therefore, future research and revision to the DSM should consider the utility of incorporating these experiences into the conceptualization of trauma, and by extension, diagnostic considerations for PTSD.

This line of research raises the question of whether other kinds of experiences can directly lead to PTSD. Racial and ethnic discrimination can involve being rejected or ridiculed, and being threatened or experiencing violence or other kinds of harm. This is particularly relevant in the current study, where a high percentage of participants reported a high frequency of such negative social interactions. According to Bryant-Davis and Ocampo (2005), racist incidents are, at minimum, a form of emotional abuse and can be traumatic. A recent meta-analysis examining perceived racism and mental health among African Americans concluded that reactions to these experiences are very similar to common trauma reactions, with individuals developing significant psychological and physical consequences (Pieterse, Todd, Neville, & Carter, 2012). Related research has shown similar patterns across other minority groups, including Latino, Asian, American Indian, and Biracial individuals (Carter & Forsyth, 2010). Racial and cultural microaggressions are also considered discriminatory events that trigger negative memories of past personal or group traumatic experiences and are experienced as threatening (Helms et al, 2012), and could help to explain the chronic course of PTSD in the current study despite high rates of treatment, as unexamined factors such as racism and ethnoviolence are precisely the ones that disproportionality affect racial or ethnic groups of color or of nondominant cultural statuses (Helms et al, 2012). Research has indeed demonstrated the link between racial microagressions and mental health symptoms, including anxiety and depression (Nadal, Griffin, Wong, Hamit, & Rasmus, 2014). There is, therefore, a pressing need to determine whether discrimination is a risk factor for PTSD in minority populations, how it may increase vulnerability to trauma or exacerbate its impact, and whether these experiences can be considered as a trauma that can result in PTSD or PTSD-like symptoms in-and-of themselves for minority individuals. This is especially important given the high frequency of discrimination experiences reported in the current sample, potentially amounting to continual re-exposure and re-traumatization. The results of the present study point to this possibility, however, much additional research is needed to support these hypotheses. Future studies must carefully assess trauma history in a way that would include discrimination experiences, including an assessment of violence and other acts toward minority populations which have the potential to be racially motivated, as this added dimension could possibly moderate the impact of the trauma. This issue is particularly relevant given the recent rise in hate crimes reported by the U.S. Department of Justice (Federal Bureau of Investigation, 2017), which indicated a 5% increase in 2016 from 2015, and a 10% rise from 2014, with African Americans targeted in nearly half of these incidents. These numbers underscore the importance of assessing such experiences in minority populations, especially because these statisics may be underrepresentative, as many hate crimes go unreported (Harlow, 2005). These documented incidents help to indirectly validate the high rates of perceived discrimination reported by minorites, suggesting the need for clinicians to recognize the reality of their experience, and avoid focusing solely on altering patient perceptions of discrimination. This systemic rise in racially motivated hate crimes, coupled with the high rates of experiences with discrimination reported in the current sample, suggest the possibility that hypervigilance for such negative social experiences may hold a degree of survival value for members of minority groups, thus contributing to the maintenance of hypervigilance as a symptom of PTSD.

While a substantial proportion of the sample did not experience remission from PTSD during follow-up, it is important to also understand why some participants did, in fact, recover during this period. Just as sociocultural variables may serve as a risk factor for the development and maintenance of PTSD, for some individuals, sociocultural factors may provide a source of resilience. For example, previous research has suggested that strength of cultural identity and connection to one’s racial and ethnic community may serve as protective factors against psychological distress (Goodstein & Ponterotto, 1997; Rowley, Sellers, Chavous, & Smith, 1998; Sellers, Caldwell, Shmeelk-Cone, & Zimmerman, 2003). Future research should therefore focus not only on reducing the negative impact of experiences with discrimination, but should also focus on building upon an individual’s sociocultural strengths in order to improve treatment outcome.

The current study had a number of strengths, as well as important limitations. Due to the naturalistic, observational nature of the study, manipulation of variables that could possibly affect the course of these disorders was not possible. For example, treatment was not controlled in any way, and because treatment was not provided by study personnel, quality could not be assessed. Moreover, this study was not epidemiological in nature, but rather was a targeted convenience sample, and therefore the results may not be generalizable to all African Americans and Latinos. Although the sample size was modest, a larger sample would further increase the generalizability of the findings. Importantly, missing data for some variables, including perceived discrimination, is an important limitation of the current study. Additionally, large scale psychometric studies examining the reliability and validity for some of our measures in minority samples is unfortunately not available, and needs to be addressed in future research. Future research would also benefit from an exploration of stressors directly associated with immigration and acculturation. Although not measured in the current study, it is likely that issues related to cultural and geographic displacement are relevant to understanding discrimination and PTSD vulnerability, and careful analysis of these factors is warranted, including qualitative methods and examination of immigrant narratives to explore the link between these experiences and mental health. Indeed, qualitative methodology and narrative-driven research is likely to provide an important complement to quantitative research in the future, as the assessment of perceived racism and discrimination may be difficult to adequately capture via quantitative methods alone. A culturally competent research approach to studying diverse populations that integrates participants in the research process may significantly contribute to a better understating of the complexities involved in elucidating the impact of experience with racism and discrimination in the course of PTSD in Latinos and African Americans. There has been an effort to use participatory action research, for example, in the study of traumatic experiences such as sexual assaults in Latinas using culturally competent recruitment and data-collection procedures that facilitate participation and disclosure (Ahrens, Isas, & Viveros, 2011), and it is likely that applying such methods to the study of racism and discrimination in future trauma research will yield valuable insights.

Despite the limitations of the current study, however, this investigation is the first of its kind to present unique course and discrimination data in a clinical sample of African Americans and Latinos, and thus represents an important contribution to our understanding of anxiety disorders in minority populations. Additional strengths of this study include the prospective design, extensive clinical interviews with good psychometric properties and well- trained assessors, and the use of a well-established longitudinal methodology.

The current findings demonstrate the chronic course of PTSD in African American and Latino adults, and highlight the potentially important role that perceived racial and ethnic discrimination may play in the development of PTSD among these populations. Future research exploring these relationships is likely to yield important advances in our understanding of risk and resilience among minority populations, as well as advances in interventions that can more effectively treat PTSD in these individuals.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from the National Institute of Mental Health, Bethesda, MD (R01MH51415, Keller, PI; K23MH080942, Perez Benitez, PI). Dr. Weisberg is an employee of the Veterans Health Administration. The opinions expressed in this work are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the funders, institutions, the Department of Veterans Affairs, or the US Government.

Biographies

Nicholas J. Sibrava

Andri S. Bjornsson

A. Carlos I. Pérez Benítez

Ethan Moitra

Risa B. Weisberg

Martin B. Keller

References

- Ahrens CE, Isas L, & Viveros M (2011). Enhancing Latinas’ participation in research on sexual assault: Cultural considerations in the design and implementation of research in the Latino community. Violence Against Women, 17(2), 177–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alegría M, Canino G, Rios R, Vera M, Calderon J, Rusch D, & Ortega AN (2002). Mental health care for Latinos: Inequalities in use of specialty mental health services among Latinos, African Americans, and non-Latino Whites. Psychiatric Services, 53, 1547–1555. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.53.12.1547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alegría M, Shrout PE, Torres M, Lewis-Fernández RL, Abelson J, Powell M, … Canino G (2009). Lessons learned from the clinical reappraisal study of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview with Latinos. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 18, 84–95. doi: 10.1002/mpr.280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alegría M, Vila D, Woo M, Canino G, Takeuchi D, Vera M, … Shrout P (2004). Cultural relevance and equivalence in the NLAAS instrument: integrating etic and emic in the development of cross-cultural measures for a psychiatric epidemiology and services study of Latinos. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 13(4), 270–288. DOI: 10.1002/mpr.181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th edition Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association (2016). Stress in America: The impact of discrimination. Stress in America Survey. [Google Scholar]

- Asnaani A, Richey JA, Dimaite R, Hinton DE, & Hofmann SG (2010). A cross-ethnic comparison of lifetime prevalence rates of anxiety disorders. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 198, 551–555. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181ea169f [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association (2000). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Text-Revision (4th ed.). Washington, DC: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Banks D, & Kyckelhahn T (2011). Characteristics of Suspected Human Trafficking Incidents, 2008–2010. Special report prepared for the Bureau of Justice Statistics, U.S. Department of Justice. (Report No. NCJ 233732). Retreived April 10, 2018, from https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/cshti0810.pdf

- Benítez CIP, Zlotnick C, Stout RL, Lou F, Dyck I,Weisberg R, Keller M (2012). A 5-year longitudinal study of posttraumatic stress disorder in primary care patients. Psychopathology, 45, 286–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boals A, & Schuettler D (2009). PTSD symptoms in response to traumatic and non-traumatic events: The role of respondent perception and A2 criterion. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 23(4), 458–462. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2008.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau J, Peterson EL, Poisson LM, Schultz LR, Lucia VC (2004). Estimating post-traumatic stress disorder in the community: Lifetime perspective and the impact of typical traumatic events. Pscyhological Medicine, 34, 889–898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce SE, Yonkers KA, Otto MW, Eisen JL, Weisberg RB, Pagano M, … Keller MK (2005). Influence of psychiatric comorbidity on recovery and recurrence in generalized anxiety disorder, social phobia, and panic disorder: A 12-year prospective study. American Journal of Psychiatry, 162, 1179–1187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown LS (2008). Cultural competence in trauma therapy: Beyond the flashback. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Brown TN, Williams DR, Jackson JS, Neighbors HW, Torres M, Sellers SL, et al. (2000). Being black and feeling blue: The mental health consequences of racial discrimination. Race and Society, 2, 117–131. doi: 10.1016/S1090-9524(00)00010-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant-Davis T, & Ocampo C (2005). Racist incident-based trauma. The Counseling Psychologist, 33(4), 479–500. doi: 10.1177/0011000005276465 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bureau of Justice Statistics. Imprisonment rate of sentenced state and federal prisoners per 100,000 U.S. residents, by sex, race, Hispanic origin, and age, December 31, 2016. Generated using the Corrections Statistical Analysis Tool at www.bjs.gov, generated April 13, 2018.

- Carter RT (2007). Racism and psychological and emotional injury: Recognizing and assessing race-based traumatic stress. The Counseling Psychologist, 35, 13–105. [Google Scholar]

- Carter RT, & Forsyth J (2010). Reactions to racial discrimination: Emotional stress and help-seeking behaviors. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 2(3), 183–191. 10.1037/a0020102 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Catalano S (2012). Intimate partner violence, 1993–2010. Special report prepared for the Bureau of Justice Statistics, U.S. Department of Justice. (Report No. NCJ 239203). Retreived April 10, 2018, from https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/ipv9310.pdf

- Cheng H, & Mallinckrodt B (2015). Racial/ethnic discrimination, posttraumatic stress symptoms, and alcohol problems in a longitudinal study of Hispanic/Latino college students. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 62(1), 38–49. doi: 10.1037/cou0000052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou T, Asnaani A, & Hofmann SG (2012). Perception of racial discrimination and psychopathology across three U.S. ethnic minority groups. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 18(1), 74–81. doi: 10.1037/a0025432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comas-Díaz L (2006). Latino healing: The integration of ethnic psychology into psychotherapy. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 43(4), 436–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan PW, & Watson AC (2007). The stigma of psychiatric disorders and the gender, ethnicity, and education of the perceiver. Community Mental Health Journal, 43, 439–458. doi: 10.1007/s10597-007-9084-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutrona CE, Russell DW, Brown PA, Clark LA, Hessling RM, Gardner KA (2005). Neighborhood context, personality, and stressful life events as predictors of depression among African American women. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 114, 3–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson JR, Hughes D, Blazer DG, & George LK (1991). Post-traumatic stress disorder in the community: An epidemiological study. Psychological Medicine, 21, 713–721. doi: 10.1017/S0033291700022352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dukes KN, & Gaither SE (2017). Black racial stereotypes and victim blaming: Implications for media coverage and criminal proceedings in cases of police violence against racial and ethnic minorities. Journal of Social Issues, 73 (4), 789–807. [Google Scholar]

- Federal Bureau of Investigation (2017). Hate Crime Statistics, 2016. Retreived January 16, 2018, from https://ucr.fbi.gov/hate-crime/2016.

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, & Williams JBW (1996). Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis-I Disorders - Patient Edition (SCID-I/PI, Version 2.0). New York: Biometrics Research Department. [Google Scholar]

- Flores E, Tschann JM, Dimas JM, Pasch LA, & de Groat CL (2010). Perceived racial/ethnic discrimination, posttraumatic stress symptoms, and health risk behaviors among Mexican American adolescents. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 57(3), 264–273. doi: 10.1037/a0020026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis JL, Weisberg RB, Dyck IR, Culpepper L, Smith K, Edelen MO, … Keller ML (2007). Characteristics and course of panic disorder and panic disorder with agoraphobia in primary care patients. Primary Care Companion, Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 9, 173–179. PMCID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin AJ, & Boyd-Franklin N (2000). Invisibility Syndrome: A clinical model of the effects of racism on African-American males. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 70, 33–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galea S, Vlahov D, Tracy M, Hooer DR, Resnick H, & Kilpatrick D (2004). Hispanic ethnicity and post-traumatic stress disorder after a disaster: Evidence from a general population survey after September 11, 2001. Annals of Epidemiology, 14, 520–531. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2004.01006.44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold SD, Marx BP, Soler-Baillo JM, & Sloan DM (2005). Is life stress more traumatic than traumatic stress? Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 19(6), 687–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodstein R, & Ponterotto JG (1997). Racial and ethnic identity: Their relationship and their contribution to self-esteem. Journal of Black Psychology, 23, 275–292. [Google Scholar]

- Harlow CW (2005). Hate crime reported by victims and police. Special report prepared for the Bureau of Justice Statistics, U.S. Department of Justice. (Report No. NCJ 209911). Retreived Jan 16, 2018, from https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/hcrvp.pdf

- Helms JE, Nicolas G, & Green CE (2012). Racism and ethnoviolence as trauma: Enhancing professional and research training. Traumatology, 18(1), 65–74. [Google Scholar]

- Himle JA, Baser RE, Taylor RJ, Campbell RD, Jackson JS (2009). Anxiety disorders among African Americans, Blacks of Caribbean descent, and non-Hispanic Whites in the United States. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 23, 578–590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller MB, Lavori PW, Friedman B, Nielsen E, Endicott J, McDonald-Scott P, … Andreasen NO (1987). The Longitudinal Interval Follow-up Evaluation: A comprehensive method for assessing outcome in prospective longitudinal studies. Archives of General Psychiatry, 44, 540–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E, Hughes M, Nelson CB (1995). Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry, 52, 1048–1060. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950240066012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger N, Smith K, Naishadham D, Hartman C, & Barbeau EM (2005). Experiences of discrimination: validity and reliability of a self-report measure for population health research on racism and health. Social Science and Medicine, 61, 1576–1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landis JR & Koch GG (1977). The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics, 33(1), 159–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leong F, Park YS, & Kalibatseva Z (2013). Disentangling immigrant status in mental health: Psychological protective and risk factors among Latino and Asian American immigrants. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 83(2–3), 361–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis TT, Cogburn CD, & Williams DR (2015). Self-reported experiences of discrimination and health: Scientific advances, ongoing controversies and emerging issues. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 11, 407–440. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032814-112728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long ME, Elhai JD, Schweinle A, Gray MJ, Grubaugh AL, & Frueh BC (2008). Differences in posttraumatic stress disorder diagnostic rates and symptom severity between Criterion A1 and non-Criterion A1 stressors. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 22(7), 1255–1263. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2008.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall GN, Schell TL, & Miles JN (2009). Ethnic differences in posttraumatic distress: Hispanics’symptoms differ in kind and degree. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 77, 1169–1178. doi: 10.1037/a0017721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadal KL, Griffin KE, Wong Y, Hamit S, & Rasmus M (2014). The impact of racial microagressions on mental health: Counseling implications for clients of color. Journal of Counseling and Development, 92, 57–66. [Google Scholar]

- Nepon J, Belik SL, Bolton J, & Sareen J (2010). The relationship between anxiety disorders and suicide attempts: Findings from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Depression and Anxiety, 27, 791–798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortega AN, & Rosenheck R (2000). Posttraumatic stress disorder among Hispanic Vietnam veterans. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 157, 615–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez Benítez CI, Sibrava NJ, Kohn-Wood L, Bjornsson AS, Zlotnick C, Weisberg R, & Keller MB (2014). Posttraumatic stress disorder in African Americans: A two year follow-up study. Psychiatry Research, 220, 376–383. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2014.07.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez Benítez CI, Sibrava NJ, Zlotnick C, Weisberg R, & Keller MB (2014). Differences between Latino individuals with posttraumatic stress disorder and those with other anxiety disorders. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 6, 345–352. doi: 10.1037/a0034328 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez Benítez CI, Zlotnick C, Dyck I, Stout R, Angert E, Weisberg R, Keller M (2012). Predictors of the long-term course of comorbid PTSD: A naturalistic prospective study. International Journal of Psychiatry in Clinical Practice, 3, 232–237. 10.3109/13651501.2012.667113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pieterse AL, Carter RT, Evans SA, & Walter RA (2010). An exploratory examination of the associations among racial and ethnic discrimination, racial climate, and trauma-related symptoms in a college student population. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 57(3), 255–263. doi: 10.1037/a0020040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pieterse AL, Todd NH, Neville HA, & Carter RT (2012). Perceived racism and mental health among Black American adults: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 59(1), 1–9. DOI: 10.1037/a0026208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts AL, Gilman SE, Breslau J, Breslau N, & Koenen KC (2011). Race/ethnic differences in exposure to traumatic events, development of post-traumatic stress disorder, and treatment-seeking for post-traumatic stress disorder in the United States. Psychological Medicine, 41, 71–83. doi: 10.1017/S0033291710000401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowley S, Sellers RM, Chavous TM, & Smith MA (1998). The relationship between racial identity and self-esteem in African American college and high school students. Journal of Social and Personality Psychology, 74, 715–724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sareen J, Cox BJ, Stein MB, Afifi TO, Fleet C, & Asmundson GJ (2007). Physical and mental comorbidity, disability, and suicidal behaivor associated with posttraumatic stress diorder in a large community sample. Psychosomatic Medicine, 69, 242–248. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31803146d8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellers RM, Caldwell CH, Shmeelk-Cone KH, & Zimmerman MA (2003). Racial identity, racial discrimination, perceived stress, and psychological distress among African American young adults. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 43, 302–317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seng JS, Kohn-Wood LP, McPherson MD, Sperlich M (2011). Disparity in posttraumatic stress disorder diagnosis among African American pregnant women. Archives of Womens Mental Health, 14, 295–306. doi: 10.1007/s00737-011-0218-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soto JA, Levenson RW, & Ebling R (2005). Cultures of moderation and expression: Emotional experience, behavior, and physiology in Chinese Americans and Mexican Americans. Emotion, 5, 154–165.doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.5.2.154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sue S, Zane N, Nagayama Hall GC, & Berger LK (2009). The case for cultural competency in psychotherapeutic interventions. Annual Review of Psychology, 60, 525–548. 10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United States Department of Housing and Urban Development. (2017). The annual homeless assessment report to Congress. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Dept. of Housing and Urban Development, Office of Community Planning and Development. [Google Scholar]

- Vazquez K, Sandler J, Interian A, & Feldman FM (2016). Emotionally triggered asthma and its relationship to panic disorder, ataques de nervios, and asthma-related death of a loved one in Latino adults. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 93, 76–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2016.11.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vega WA, Kolody B, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, & Catalano R (1999). Gaps in service utilization by Mexican Americans with mental health problems. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 156, 928–934. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.6.928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ventura J, Liberman RP, Green MF, Shaner A, & Mintz J (1998). Training and quality assurance with the structured clinical interview for DSM-IV (SCID-I/P). Psychiatry Research, 79, 163–173. doi: 10.1016/S0165-1781(98)00038-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang PS, Lane M, Olfson M, Pincus HA, Wells KB, & Kessler RC (2005). Twelve-month use of mental health services in the United States: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62, 629–640. doi: 10.1001/archpsych.62.6.629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warshaw MG, Keller MB, & Stout RL (1994). Reliability and validity of the Longitudinal Interval Follow-up Evaluation for assessing outcome of anxiety disorders. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 28, 531–545. PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weathers FW, & Keane TM (2007). The Criterion A problem revisited: Controversies and challenges in defining and measuring psychological trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 20(2), 107–121. DOI: 10.1002/jts.20210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisberg R, Beard C, Dyck I, & Keller MB (2012). The Harvard/Brown Anxiety Research Project – phase II (HARP-II): Rationale, methods, and features of the sample at intake. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 26, 532–543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams D, Gonzalez H, Williams S, Mohammed S, Moomal H, Stein D. (2008). Perceived discrimination, race, and health in South Africa. Soc Sci & Medicine, 67, 441–452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, & Mohammed SA (2009). Discrimination and racial disparities in health: Evidence and needed research. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 32, 20–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Yu Y, Jackson J, & Anderson N (1997). Racial differences in physical and mental health: Socioeconomic status, stress, and discrimination. Journal of Health Psychology, 2(3), 335–351. doi: 10.1177/135910539700200305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zayfert C (2008). Culturally competent treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder in clinical practice: An ideographic, transcultural approach. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 15(1), 68–73. [Google Scholar]

- Zlotnick C, Rodriguez BF, Weisberg RB Bruce SE, Spencer MA, Culpepper L, Keller MB (2004). Chronicity in posttraumatic stress disorder and predictors of the course of posttraumatic stress disorder among primary care patients. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 192, 153–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zlotnick C, Warshaw M, Shea MT, Allsworth J, Pearlstein T, & Keller MB (1999). Chronicity in posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and predictors of course of comorbid PTSD in patients with anxiety disorders. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 12, 89–100. doi: 10.1023/A:1024746316245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]