Abstract

Biologics are playing an increasingly significant role in the practice of modern medicine and surgery in general and orthopedics in particular. Cell-based approaches are among the most important and widely used modalities in orthopedic biologics, with mesenchymal stem cells and other multi/pluripotent cells undergoing evaluation in numerous preclinical and clinical studies. On the other hand, fully differentiated endothelial cells (ECs) have been found to perform critical roles in homeostasis of visceral tissues through production of an adaptive panel of so-called “angiocrine factors.” This newly discovered function of ECs renders them excellent candidates for novel approaches in cell-based biologics. Here, we present a review of the role of ECs and angiocrine factors in some visceral tissues, followed by an overview of current cell-based approaches and a discussion of the potential applications of ECs in soft tissue repair.

Keywords: endothelial cell, angiocrine factor, regeneration, tendon, ligament

Overview of the role of endothelial cells

The body’s microvasculature comprises an extensive network of capillary endothelial cells (ECs) that connects the arterioles to venules. This microvascular bed has historically been perceived as a passive conduit for delivering oxygen and nutrients, modulating local blood flow and blood coagulation, and regulating the transportation of cells, such as inflammatory cells.1,2 Recent work demonstrates that these cells also function to sustain the homeostasis of resident stem cells and to guide the regeneration and repair of adult organs without provoking fibrosis.3

Recent microanatomical observations have revealed a very consistent perivascular microstructure where epithelial, hematopoietic, mesenchymal, and neuronal cells, together with their corresponding stem and progenitor cells, reside in proximity to capillary ECs. Further genetic and biochemical studies have shown that ECs serve as a fertile, instructive niche that has important roles in homeostasis, metabolism, and directing organ regeneration.3,4 Tissue-specific ECs regulate these complex tasks by supplying the repopulating cells with stimulatory and inhibitory growth factors, morphogens, extracellular matrix components, and chemokines. These EC-derived paracrine factors are collectively known as angiocrine factors5,6 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Angiocrine factors

| Tissue | Angiocrine factors | Authors |

|---|---|---|

| Nonspecific | Angiopoietin 2 | Yancopoulos et al.102 |

| BMP2, BMP4 | Mathieu et al.103 | |

| CXCR4, SDF1 | Tachibana et al.104 | |

| DKK, MMP | Nolan et al.5 | |

| Endothelin-1, FGF, G-CSF, GM-CSF, IGF-1, IL-1, IL-6, IL-8, PDGF, TGF-β | Pirtskhalaishvili et al.105 | |

| FOXO1, FOXOX3A | Potente et al.106 | |

| Jagged-1, Jagged-2, Notch, TNF-α | Zeng et al.107 Fernandez et al.108 | |

| Lama-4, Laminin-1 | Lammert et al.109 Nikolova et al.110 | |

| NO | Koistinen et al.111 | |

| PEDF | Ramirez-Castillejo et al.112 | |

| PGF, VEGF-A, VEGF-B, VEGFR (follistatin-like 1) | Carmeliet et al.113 | |

| Wnt | Wang et al.41 | |

| Liver | Id1-HGF, Id1-Wnt2 | Ding et al.114 |

| Rspondin3 | Rocha et al.115 | |

| Lung | BMP4–NFATC1–thrombospondin-1 | Lee et al.116 |

| MMP14-mediated VEGFR ligand release | Rafii et al.43 |

Abbreviations: BMP, bone morphogenetic protein; CXCR4, chemokine receptor type 4; DKK, Dickkopf-related protein; FGF, fibroblast growth factor; FOXO, forkhead box O; G-CSF, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor; GM-CSF, granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor; HGF, hepatocyte growth factor; Id, inhibitor of differentiation; IGF-1, insulin-like growth factor-1; IL, interleukin; Lama-4, laminin subunit α4; MMP, matrix metalloproteinase; NFATc1, nuclear factor of activated T cells 1; NO, nitric oxide; PDGF, platelet-derived growth factor; PEDF, pigment epithelium–derived factor; PGF, placental growth factor; SDF-1, stromal cell–derived factor-1; TGF-β, transforming growth factor β; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor; VEGFR, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor; Wnt, wingless-type MMTV integration site family.

The term “angiocrine” emphasizes the biological significance of the instructive factors produced by the ECs that influence the homeostasis of healthy and malignant tissues.6 Angiocrine factors comprise secreted and membrane-bound inhibitory and stimulatory growth factors, trophogens, chemokines, cytokines, extracellular matrix components, exosomes, and other cellular products that are supplied by tissue-specific ECs to help regulate homeostatic and regenerative processes in a paracrine fashion. These factors also play roles in adaptive healing and fibrotic remodeling.7 Tissue-specific stem and progenitor cells are strategically positioned in close proximity to homotypic capillary ECs. This intimate cellular interaction facilitates the delivery of membrane-bound and soluble angiocrine factors from specialized ECs to the recipient cells, which are located on the basolateral surfaces of blood vessels. Tissue-resident parenchymal and stem cells regulate the activation state and response of ECs to regenerative stimuli through the production of angiogenic factors.3

Interest in what is known as the “microvascular niche” began in the mid-1990s with a series of bone marrow EC (BMEC) isolation and coculturing studies that proved the sufficiency of BMECs in maintaining hematopoietic stem cell engraftment, expansion, and differentiation.8,9 In the original studies, this was shown to occur in a fashion superior to that triggered by human umbilical vein ECs—a classical source of in vitro ECs. Later data showed that clonal expansion of stem cells while maintaining their multipotent phenotype was possible in a BMEC-rich milieu.10 The data supported the hypothesis that local microvascular niches of tissues produce optimal complements of soluble factors and signals, in terms of both concentration and temporal expression profile, to stimulate and support local stem cell expansion and differentiation.

In the setting of pathophysiological stress (e.g., exposure to ionizing radiation, chemical injury, or hypoxic conditions) or loss of tissue mass, defined angiocrine factors emanate from activated ECs. The activated ECs relay inflammatory and injuryinduced angiocrine signals to quiescent tissuespecific stem cells, which drives regeneration and enforces developmental set points to reestablish homeostatic conditions.3 Microvascular ECs therefore fulfill the criteria for “professional niche cells” that choreograph tissue regeneration by cradling and nurturing stem cells with physiological levels and proper stoichiometry of angiocrine factors.3

Tissue- and organ-specific capillary ECs are now being recognized as specialized cells that, through balanced physiological expression of angiocrine factors, maintain stem cells’ capacity for quiescence and self-renewal. Spatially and temporally coordinated production of angiocrine factors after organ injury initiates and completes organ regeneration. These findings raised the possibility that the inherent proregenerative potential of tissue-specific endothelium could be used therapeutically to orchestrate fibrosis-free healing; restore native, original microarchitecture; and reestablish homeostasis in numerous tissue types.3

Here, we discuss the role of ECs, current cell-based approaches, and the potential advantage of using ECs in soft tissue repair.

Role of endothelial cells in tissues

ECs in specific tissues work together, cross-talking with other cells in the organ. In this paragraph, ECs in bone marrow, liver, and lung are discussed as representative examples.

The bone marrow stromal environment consists of myriad cells, including fibroblasts, ECs, adipocytes, and osteoclasts, and a complex network of extracellular matrix within which hematopoiesis occurs. The importance of the interplay between the bone marrow stroma and bone marrow progenitors in enabling hematopoiesis has been well established for many decades.11–13 However, research has focused on the stem cell–stroma interaction, and for a period of time little was known about the stromal environment beyond the fact that it created the necessary microenvironment for successful hematopoietic self-renewal and differentiation. Traditional understanding of hematopoiesis thus tended to simplify marrow stroma as a singular supportive entity for the more important hematopoietic pathways, failing to acknowledge that the stroma is actually a dynamic and highly heterogeneous tissue that drives marrow function.

The specific importance of BMECs in the stem cell–stroma interaction remained largely unknown, as these cells were felt to play a minor role in the total mass of the marrow stroma. Focus on the BMEC as a central player in immunity and hematopoiesis rather than as a simple conduit allowing immune and hematopoietic cell adhesion and trafficking is a relatively new and burgeoning field and is currently a hotly contested area of research owing to the promises of regenerative medicine.

The three-dimensional (3D) structure of bone marrow vascular niches is complex, involving variations in capillary structure and permeability, which are in turn linked to various degrees of functional variation. For instance, arterial BMECs demonstrate low reactive oxygen species (ROS) permeability and are associated with highly quiescent hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs). In contrast, sinusoidal BMECs demonstrated high ROS permeability and are associated with actively differentiating HSPCs as well as acting as hot spots for leukocyte trafficking.13 In addition to phenotypic variability, ECs demonstrate phenotypic plasticity as well, as shown by the potential for in vitro conversion of mature ECs into hematopoietic progenitor cells14 and conversely by differentiation of bone marrow–derived mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) into ECs.15–17

Following studies that described BMECs came the discovery of BM-derived endothelial progenitor cells (BMEPCs).18–21 It is thought that the bone marrow contains not just ECs that form endothelial tissues but also endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs) that can be mobilized to the peripheral circulation and participate in distant neovascularization events. Studies on BMEPCs have since exploded as a result of their potential value in cellular transplantation. Early evidence has shown their potential to improve outcomes in tissue regeneration, including in cardiac ischemia,22–24 recurrent miscarriages due to placental vascular insufficiency,25 intracranial bleed,26 stroke,27–29 and traumatic brain injury30 and in repairing soft tissue defects.31 BMEC dysregulation has also been implicated in myelodysplastic syndrome,32 multiple myeloma,33 acute myeloid leukemia,34,35 and other animal cancer models19,36 and as a player in tumor neoangiogenesis. To date, there is little data on direct human transplantation of BMEPCs; thus far, clinical trials demonstrated no significant difference in EPC-treated end-stage limb ischemia37,38 and orthopedic nonunion.39 There remains much optimism for EPC-based cell therapy, derived from the bone marrow or otherwise, pending larger studies that show human clinical efficacy.

Liver sinusoidal ECs (LSECs) are unique ECs in both morphological and functional aspects. In liver organogenesis during embryogenesis, vasculogenic ECs are known to play a critical role in the early stage before the development of systemic circulation.40 LSECs produce specific angiocrine factors, including WNT2 and WNT9B, to modulate the proliferation of the hepatocytes that repopulate the liver.41 Under homeostatic conditions, the repopulating potential and zonation of hepatocytes are established by angiocrine factors from LSECs. Liver regeneration is a fundamental response to liver injury and involves sequential changes in gene expression, growth factor production, and morphologic structure. It also appears that LSECs have a dual role in controlling the regeneration of the liver and provoking tissue fibrosis. After an acute injury to the liver, the angiocrine factors promote fibrosisfreerepair.7 On the other hand, chronic injury to the liver leads to the upregulation of factors that shift the balance to angiocrine secretion of profibrotic transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1) and BMP2, leading to fibrosis.7 Thus, LSECs play an important role in governing the homeostasis and regeneration of pathological changes in the liver.

The lung alveoli are highly vascularized, with pulmonary capillary ECs (PCECs) lining all alveoli. Lung organogenesis during embryogenesis is influenced by the cross talk between alveolar epithelial cells (AECs) and mesenchymal cells. PCECs are required for lung regeneration after injury by producing specific angiocrine factors.42 Following lung injury, activation of PCECs then triggers upregulation of MMP-14, which leads to activation of the epidermal growth factor (EGF) receptor on AECs to enhance proliferation of AECs, resulting in neoalveologenesis.43

The potential role of engineered ECs in therapeutic approaches: endothelial cell activation by E4ORF1 transfection

Although ECs are quiescent and long-lived with an average half-life of years in vivo, when they are removed from blood vessels and cultured in vitro, they die quickly.44 Maintenance of primary ECs (PECs) in vitro requires the use of enriched EC growth medium that is supplemented with serum; proangiogenic factors, including vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-A, fibroblast growth factor (FGF)-2, EGF, and insulin-like growth factor; and EC growth supplement.45–47 Notably, deprivation of PECs for a few hours from these growth factors causes rapid cell death.44,48 Therefore, the use of PECs as feeder cells must be performed in the presence of EC growth medium, which artificially affects the growth of cocultivated stem and tumor cells, providing a major confounding variable in such studies.49 To overcome these difficulties, PECs have been immortalized with human telomerase reverse transcriptase or simian virus 40 large T and polyoma middle T oncogenes.50 However, activation of proliferative phospho-MAPK (pMAPK) signaling pathways in these cell lines has resulted in generation of dysregulated ECs that are either serum dependent or have acquired transformed phenotypes atypical of PECs. Furthermore, because of a high metabolic rate, immortalized PECs deprive the cocultured stem and tumor cells of nutrients, eventually resulting in cell death.

In the late 1990s, it was found that the adenovirus (Ad)–early region 4 (E4) gene complex maintains angiogenic properties of PECs by modulating the migration and apoptosis of PECs.51 The gene products encoded by Ad–E4 are essential for virus replication, modulating the cell cycle, apoptosis, and cell signaling.52 Ad–E4 products promote PEC survival through increasing Src kinase and PI3-kinase phosphorylation and by reducing caspase-3 activity.53 In fact, Ad–E4 mRNA contains seven ORFs, suggesting that E4 encodes at least six gene products (E4ORF1–E4ORF6/7). Among E4 ORFs, E4ORF1 primarily affects survival but not cell proliferation.54,55 It was further discovered that the adenoviral E4ORF1 gene product maintains long-term survival and facilitates organ-specific purification of PECs in serum/cytokine-free conditions while preserving their in vivo angiogenic potential for tubulogenesis and sprouting. The development of serum-free and xenobiotic-free coculture platforms by E4ORF1+ ECs enables researchers to molecularly “eavesdrop” on the cross talk between ECs and tissue-repopulating stem cells. This could uncover the pathways that regulate the expression of tissue-specific angiocrine factors that are transcriptionally and biophysically induced.

The prosurvival effect of E4ORF1 is caused by activation of the PI3K–Akt signaling pathway. Inhibition of both mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) and nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) signaling was essential to completely abrogate the prosurvival effect afforded by the E4ORF1 gene. These results suggest that the E4ORF1 protein enhances the survival of PECs mainly by recruiting the PI3-kinase– Akt/mTOR and PI3-kinase–Akt/NF-κB pathways without oncogenic transformation, and, additionally, E4ORF1 activation of the FGF2/FGFR1 pathway might also contribute to the survival of PECs.49

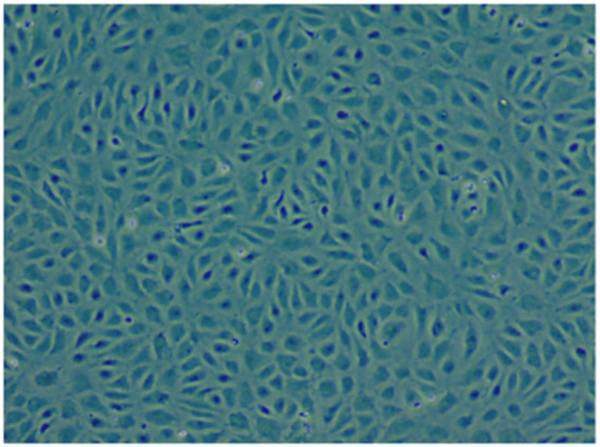

E4ORF1 is now commercially available (VeraVec ECs (VVECs), Angiocrine Bioscience; Fig. 1). Introduction of E4ORF1 allows ECs to survive and grow outside the body, secrete tissue-specific angiocrines at physiological levels, initiate the process of tissue regeneration, and expand ECs that maintain the phenotypic fidelity from different sources. VVECs can be prepared from any source of ECs (from different organs or from embryonic vessels and from human or animal vessels).50,56 In fact, Angiocrine Bioscience has prepared a VVEC library from different sources. VVECs are kept in a state of activity that simulates in vivo inductive angiogenesis, where injured tissues demand that vessels proliferate and produce angiocrine factors required for repair/regeneration. Additionally, so far VVECs have not demonstrated any malignant potential and could be adapted to comply with regulatory clinical guidelines. Thus, these engineered ECs provide an ideal platform for interrogating the angiocrine function of ECs in models of organ regeneration and for translating the proregenerative therapeutic potential of these cells to the clinical setting.10

Figure 1.

Human umbilical vein–activated endothelial cells.

A review of current cell-based approaches in soft tissue repair in orthopedics

Cell-based approaches have become increasingly popular as a means to augment healing in modern medicine and surgery. The number of available options is regularly increasing, and both physicians and investigators have a large number of cell types to choose from for research or therapeutic purposes. By definition, cell-based therapies involve injection/inoculation/implantation of living cellular elements into patients. Modern orthopedics, in particular, has been a thriving arena for various cell-based therapeutic options.

Cell sources used in orthobiologics include embryonic stem cells (ESCs), induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells, MSCs, EPCs, or differentiated cells.

Due to far-reaching ethical issues, the use of pluripotent stem cells derived from human embryos is heavily regulated, and therefore is not readily accessible for research and therapeutic purposes. In the United States, these cells can only be used through an U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved trial after a stringent review process.57 Of note, from a safety standpoint, a serious consideration is that ESC and iPS cells may harbor tumorigenic potential. It has been demonstrated that if these cells are injected in an undifferentiated state, they can potentially cause teratomas, and mice generated from iPS cells may show high rates of neoplasia.58,59

MSCs are by far the most widely used adult stem cells. Although bone marrow and adipose tissues are currently the most popular sources of MSCs because of less elaborate procurement methods, these cells can be obtained from almost all tissue types,60 including tendons and ligaments. Bone marrow– derived MSCs can differentiate into several types of connective tissue, including cartilage, bone, tendon, ligament, adipose, and muscle.61–63

All tissues aside from cartilage and cornea have blood vessels that provide nutrition. Furthermore, it has been reported that the vascular niche plays a crucial role in homeostasis, proliferation, and differentiation of intrinsic local stem cells during regeneration of tissue.7 Thus, neovascularization not only supplies nutrition but also improves the microenvironment for tissue regeneration. The EPCs, which are characterized by CD34 and CD133 expression, have been considered as a promising cell source for tissue regeneration. EPCs are able to differentiate into ECs and contribute to neovascularization.21 Furthermore, EPCs secrete angiocrine factors, such as VEGF, hepatocyte growth factor, platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), and monocyte chemotactic protein 1.64 EPCs have been evaluated for treatment of ischemic disease in animal models and clinical studies. More recent studies have provided early data to support the use of EPCs to enhance healing of tendon and ligament injury (Table 2). It has been reported that the transplantation of EPCs increased the expression of VEGF in the torn ligament and enhanced the vascularization and repair of ligament in rat medial collateral ligament injury models.65 Recently, Kawakami et al. reported that anterior cruciate ligament (ACL)-derived EPCs transduced with BMP2 accelerated graft–bone integration in a rat ACL reconstruction model.66

Table 2.

Preclinical studies of cell therapy in tendon and ligament injury

| Reference | Year | Animal | Repair model | Cell type | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tei et al.65 | 2008 | Rat | MCL | EPCs | Increased vascularity in the torn tendon. Better healing of the torn tendon. |

| Kawakami et al.66 | 2017 | Rat | ACLR | EPCs transduced with BMP2 | Greater failure force at graft-bone interface. Better histological appearance. |

| Gulotta et al. 73 | 2011 | Rat | RCT | BM-MSCs transduced with SCX | Greater biomechanical properties. More fibrocartilage tissue in the enthesis. |

| Degen et al.74 | 2016 | Athymic Rat | RCT | Human BM-MSCs | Better collagen orientation and fibrocartilage formation. Greater strength at the repair site. |

| Oh et al.76 | 2014 | Rabbit | RCT | ADSCs | Decreased fatty filtration in muscle after repaired tendon. Better microstructure of enthesis. |

| Mora et al.77 | 2014 | Rat | RCT | ADSCs | No improvement of biomechanical property. Less inflammation in the repair tissue. |

| Eliasberg et al.78 | 2017 | Immunodeficient mice | RCT | PSCs (from adipose tissue) | Decreased muscle atrophy after transection of tendon. |

| Ju et al.82 | 2008 | Rat | ACLR | SDSCs | Enhanced collagen fiber formation between graft and tunnel. No improvement of fibrocartilage formation. |

| Lee et al.84 | 2015 | Rat | PT | TDSCs | Better mechanical properties. Microstructure of the repaired tendon resembles the native tendon |

Abbreviations: ACLR, anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction; ADSCs, adipose-derived stem cells; BM, bone marrow; BMP, bone morphologic protein; EPCs, endothelial progenitor cells; MCL, medial collateral ligament; MSCs, mesenchymal stem cells; PSCs, perivascular stem cells; PT, patella tendon; SCX, scleraxis; SDSCs, synovium-derived stem cells; SSCT, subscapularis tendon; SST, supraspinatus tendon; RCT, rotator cuff tendon; TDSCs, tendon-derived stem/stromal cells.

Finally, differentiated cells, such as tenocytes, chondrocytes, and tissue-specific ECs, are fully differentiated and are being increasingly considered for cell-based studies, since using differentiated cells would carry less risk of teratoma formation and fewer ethical concerns.

When it comes to actual application of a cellbased biologic, selection of an effective delivery technique is a crucial step to consider. Currently, there is no consensus about the ideal carrier construct, as few clinical data are available for cellbased approaches in tendon repair.59 However, two major delivery categories are direct injection of a cell suspension alone and implantation of cells that are placed in a matrix carrier vehicle. The majority of studies on tendons have used some form of a scaffold—gel suspensions, 3D scaffolds of solid tissue, or combinations thereof—for local delivery of cells,59 with the fibrin sealant being the most widely used gel scaffold.67,68 Other scaffolds included collagen gel,69 gel–collagen sponge composites,70 and decellularized slices of tendon.71

MSCs have been a focus of intense in vitro and preclinical/animal research. Their ability to differentiate into specific lineages, including a tenogenic lineage, makes them a promising cell source for tendon and tendon-to-bone repair. Bone marrow was first described as a viable source of MSCs (BMMSCs) in 1970 by Friedenstein et al.72 Bone marrow is the standard and most common source of autologous MSCs with the ability to biologically augment various tendon healing sites. Gulotta et al. demonstrated that allogeneic BM-MSCs transduced with the gene for scleraxis (SCX) improved tendon healing in a rat rotator cuff model, as shown by histological and biomechanical analysis.73 They showed that SCX led to a significance increase in the strength of repair and the amount of fibrocartilage at 4 weeks. Recently, human BM-MSCs have been transplanted in an athymic rat rotator cuff tendon repair model.74 Fibrocartilage formation, collagen orientation, and biomechanical strength were improved 2weeks after transplantation. Another important source of multipotent stem cells is adipose tissue (adipose-derived stem cells (ADSCs)). Zuk et al. showed a favorable potential for augmenting rotator cuff repair with ADSCs.75 Oh et al. were among the first to report the use of injected ADSCs in a rabbit subscapularis rotator cuff repair model and found better healing properties and histologically decreased fatty infiltration of the muscle.76 Mora et al. used ADSCs with a collagen carrier in a rat supraspinatus repair model and demonstrated no improvement in the biomechanical properties of the tendon-to-bone healing, but the ADSC group showed less inflammation based on histologic analysis of the healing tissue.77 Eliasberg et al. found that perivascular stem cells, including both pericytes characterized as CD146+ CD34− CD45− CD31− and adventitial cells characterized as CD146− CD34+ CD45− CD31− obtained from human adipose tissue, decreased muscle atrophy in an immunodeficient mouse rotator cuff repair model.78

Synovial-derived MSCs (SDMCs) appear to have better chondrogenic and proliferation potential compared with bone marrow, adipose, and muscle-derived cells79 and have been reported to improve articular cartilage and meniscus healing.80,81 Therefore, they could be a desirable cell source for tendon and ligament restoration. Ju et al. implanted SDMCs into the graft–bone interface and found acceleration of collagen fiber formation.82 Tendon-derived stem cells (TDSCs) have been identified as an additional cell population in tendons and can be considered another source of MSCs. The multipotency of TDSCs were also characterized in torn human rotator cuff tendons.83 Interestingly, a rare CD146+ tendon-resident stem cell population was identified in a rat patellar tendon. Subsequent to enrichment by connective tissue growth factor (CTGF), these cells demonstrated tenogenic differentiation.84 Application of these cells in a patellar tendon repair model successfully led to tendon regeneration and functional restoration. Ligament-derived stem cells (LDSCs) are another emerging cell source. LDSCs were originally identified in the periodontal ligament,85 with more recent literature showing LDSCs obtained from intraarticular ligaments.86 Despite promising results from these studies on MSCs, the potential risk of tumorigenesis and gene mutation should be considered.

Potential advantage of endothelial cells in cell-based approaches for soft tissue repair in orthopedics

Major challenges to reestablish microarchitecture of native orthopedic soft tissue include the identification of the optimal healing factors, timing of delivery of these healing factors, and application of these factors to the site of repair through the use of scaffolds. As an example, regeneration of the native tendon–bone interface requires the complex and incompletely understood combination of cell- and scaffold-based approaches to successfully recreate this complex interface. In addition, it is known that mechanical factors are vital to the proper development of the tendon–bone interface—known as the enthesis87–89—a parameter that is especially difficult to control. The need for multiple biological factors and mechanical influences in combination with the specific composition, function, and mechanical properties of fibrocartilaginous enthuses makes it extremely difficult to recreate this native construct.90,91

As we move forward in our quest to provide patients with better surgical outcomes, clinicians and investigators find themselves more interested in “regeneration,” which implies restoration of native structures, rather than “repair,” which suggests filling the gap in a tissue with a qualitatively and/or quantitatively better scar. Since regenerative and developmental processes have a lot in common,92 modification of the reparative processes into a regenerative process presents a significant challenge.

Attempts to augment the repair strength have historically focused on restoration of the original microarchitecture or production of a more robust fibrotic tissue. A denser, larger scar will impart more strength to the repaired enthesis but does not provide the construct with the desirable material properties, including capability to handle repeated stress. This means that promotion of healing by inducing a larger, thicker scar will not necessarily culminate in better clinical outcomes, especially in the long term. Application of biologics has been an active area of research to explore strategies to direct the tendon-to-bone repair process along one or both of the abovementioned fates. Modern biologics have mainly concentrated on delivery of active molecules, such as various growth factors, including TGF-β3,93,94 cellular structures, or a combination thereof.

Several angiocrine factors have been examined for their effect on tendon or ligament healing. VEGF stimulates both angiogenesis and vasculogenesis. Exogenous VEGF injection to a repair site improves the biomechanical properties of repaired Achilles tendon in rat.95 On the other hand, it was reported that graft strength and laxity in the VEGF treatment group were inferior to the control group.96 PDGF-BB stimulates matrix synthesis and cell division. PDGF-BB administration has been reported to enhance tendon healing in a rat rotator cuff repair model.97 There are many reports showing a positive effect of FGF2 (basic FGF) on tendon healing.98 A principal challenge to the use of those growth factors and cytokines is identification of optimal delivery vehicles that will localize the factor to the repair site for a sufficient length of time and in the appropriate dose.99 More importantly, healing is a highly complex process requiring the coordinated actions of many cytokines and signaling molecules, and thus application of a single exogenous cytokine is a limited approach.

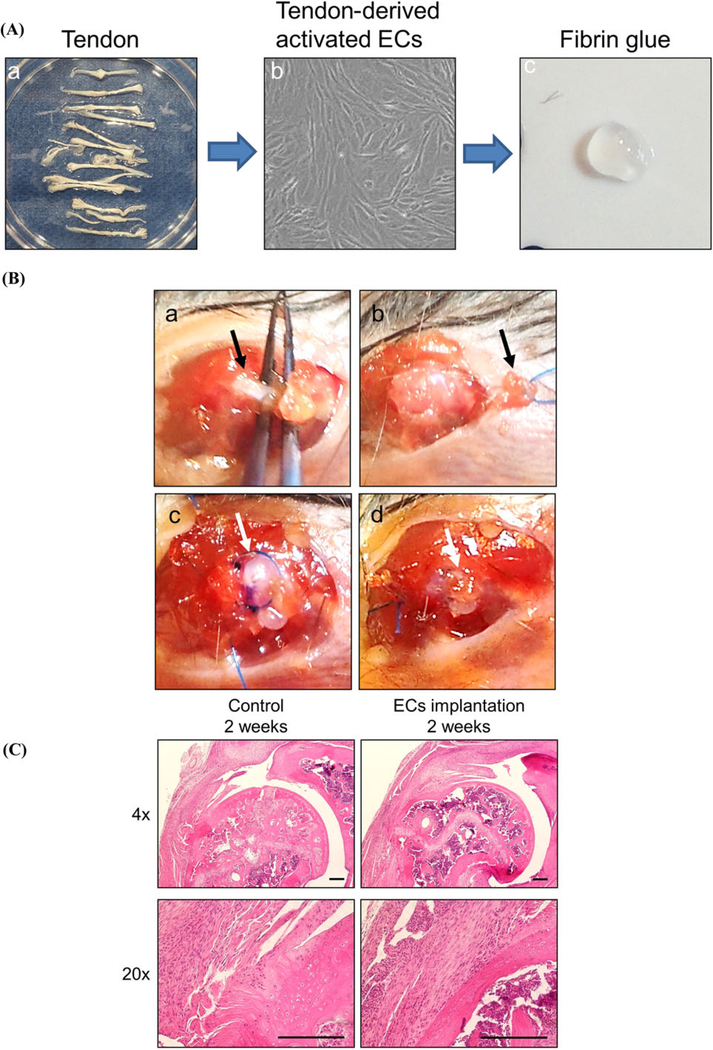

Given the intricacy of regenerative mechanisms and many poorly or incompletely understood processes, it simply appears that application of factor X or cell Y is not enough to arrange the entire orchestra and, therefore, there is a need for a different approach. Previous studies have demonstrated the potential for ECs to act as an intelligent source of this trigger in visceral tissues.7,42 However, to date there have been no reported data on the effect of ECs on tendon and ligament healing. We are currently evaluating the effect of tendon-derived activated ECs (VeraVec cells; Fig. 2A) on tendon healing using a mouse rotator cuff repair model (Fig. 2B), with encouraging early results (Fig. 2C).100 We are currently working to elucidate the underlying cellular and molecular mechanisms through cell tracking and gene expression analysis.

Figure 2.

(A) Tendon-derived activated endothelial cells. Tendons were harvested (a) and isolated to create tendon-derived activated ECs. A total of 100,000 cells were suspended in 5 μL fibrin glue (c). (B) Transplantation of tendon-derived activated ECs in murine rotator cuff tendon repair model. Rotator cuff tendon (indicated by black arrow) was isolated (a). After suture placement in the tendon, the tendon was then detached from the humerus (b). After passing sutures through bone tunnels, fibrin glue beads (indicated by white arrow) containing cells were transplanted to the repair site, followed by suture tying. (C) Histological evaluation with hematoxylin and eosin staining of a murine supraspinatus tendon repair model. The EC implantation group showed superior tendon-to-bone healing at 2 weeks after the operation compared with the control group, which showed no cell implantation. Scale bar indicates 200 μm.

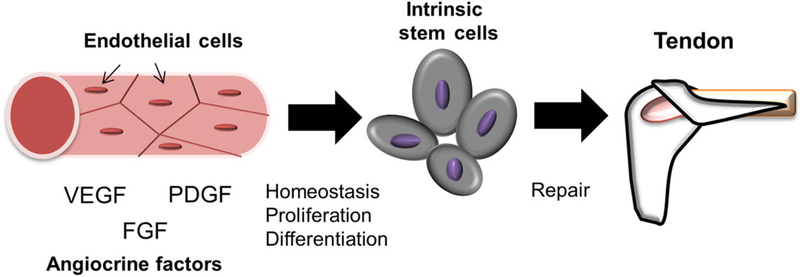

Currently, many researchers focus more on stem cells than fully differentiated cells, but the advantages of a differentiated EC would be less risk of teratoma formation and possibly fewer ethical concerns compared with stem cells. Because ECs are known to secrete angiocrine factors in tissues with specialized function, it has been suggested that they could be a viable cell source for implantation. Accordingly, the possibility to trigger regenerative cellular and molecular pathways in the native cell populations, notably the quiescent stem cell niche, without the need to know what and when active molecules are needed sounds appealing. It has been reported that tissue-specific ECs are a source of developmental cues for hepatic40 and pancreatic tissues.101 Later, it was found that local ECs were also a source of regenerative signals in fully developed tissues.7,42 Subsequent investigations further elucidated that angiocrine factors play critical roles in repair and regeneration of adult lung and liver in a tissue-specific fashion. These discoveries suggest that tissue-specific ECs are a promising new approach to cell-based biologic treatment of tendon and ligament healing (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

ECs contribute to homeostasis, development, and regeneration of soft tissues by supporting intrinsic stem cells via a paracrine effect produced by numerous angiocrine factors. Recent and ongoing work indicates that ECs are a promising candidate as a cell source for the treatment of tendon and ligament injury.

Conclusions

Fully differentiated ECs regulate proliferation and differentiation of the quiescent stem cell niche in visceral tissues, a process mediated through production of angiocrine factors and facilitated by a juxtaposed microanatomy. This discovery indicates that ECs hold great potential as a novel approach in cell-based biologics. The most important theoretical advantage of using ECs in biologics is the possibility of simulating and harnessing physiologic interactions between the stem cell niche and ECs to regenerate native microstructures. This phenomenon is particularly needed in biomechanically active orthopedic soft tissues, where restoration of the original microarchitecture is of utmost importance.

Acknowledgment

The authors acknowledge with thanks the important data provided by Daniel J. Nolan, Ph.D.

Footnotes

Competing interests

Scott A. Rodeo is a consultant with Angiocrine Bioscience. The other authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Carmeliet P & Jain RK. 2011. Molecular mechanisms and clinical applications of angiogenesis. Nature 473: 298–307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ghesquiere B et al. 2014. Metabolism of stromal and immune cells in health and disease. Nature 511: 167–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rafii S, Butler JM & Ding BS. 2016. Angiocrine functions of organ-specific endothelial cells. Nature 529: 316–325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Butler JM et al. 2010. Endothelial cells are essential for the self-renewal and repopulation of Notch-dependent hematopoietic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell 6: 251–264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nolan DJ et al. 2013. Molecular signatures of tissue-specific microvascular endothelial cell heterogeneity in organ maintenance and regeneration. Dev. Cell 26: 204–219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Butler JM, Kobayashi H & Rafii S. 2010. Instructive role of the vascular niche in promoting tumour growth and tissue repair by angiocrine factors. Nat. Rev. Cancer 10: 138–146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ding BS et al. 2014. Divergent angiocrine signals from vascular niche balance liver regeneration and fibrosis. Nature 505: 97–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rafii S et al. 1994Isolation and characterization of human bone marrow microvascular endothelial cells: hematopoietic progenitor cell adhesion. Blood 84: 10–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rafii S et al. 1995. Human bone marrow microvascular endothelial cells support long-term proliferation and differentiation of myeloid and megakaryocytic progenitors. Blood 86: 3353–3363. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gori JL et al. 2017. Endothelial cells promote expansion of long-term engrafting marrow hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells in primates. Stem Cells Transl. Med 6: 864–876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dexter TM, Allen TD & Lajtha LG. 1977. Conditions controlling the proliferation of haemopoietic stem cells in vitro. J. Cell. Physiol 91: 335–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deryugina EI & Muller-Sieburg CE. 1993. Stromal cells in long-term cultures: keys to the elucidation of hematopoietic development? Crit. Rev. Immunol 13: 115–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Itkin T et al. 2016. Distinct bone marrow blood vessels differentially regulate haematopoiesis. Nature 532: 323–328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lis R et al. 2017. Conversion of adult endothelium to immunocompetent haematopoietic stem cells. Nature 545: 439–445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang Q et al. 2016. Method for in vitro differentiation of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells into endothelial progenitor cells and vascular endothelial cells. Mol. Med. Rep 14: 5551–5555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Allameh A, Jazayeri M & Adelipour M. 2016. In vivo vascularization of endothelial cells derived from bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells in SCID mouse model. Cell J. 18: 179–188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ikhapoh IA, Pelham CJ & Agrawal DK. 2015. Atherogenic cytokines regulate VEGF-A-induced differentiation of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells into endothelial cells. Stem Cells Int. 2015: 498328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lyden D et al. 2001. Impaired recruitment of bone marrow-derived endothelial and hematopoietic precursor cells blocks tumor angiogenesis and growth. Nat. Med 7: 1194–1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Skelton WP 3rd & Skelton NK. 1991. Alzheimer’s disease. Recognizing and treating a frustrating condition. Postgrad. Med 90: 33–34, 37–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Takahashi T et al. 1999. Ischemia- and cytokine-induced mobilization of bone marrow-derived endothelial progenitor cells for neovascularization. Nat. Med 5: 434–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Asahara T et al. 1999. Bone marrow origin of endothelial progenitor cells responsible for postnatal vasculogenesis in physiological and pathological neovascularization. Circ. Res 85: 221–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yue Y et al. 2017. Interleukin-10 deficiency impairs reparative properties of bone marrow-derived endothelial progenitor cell exosome function. Tissue Eng. Part A 23: 1241–1250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jian KT et al. 2015. Time course effect of hypoxia on bone marrow-derived endothelial progenitor cells and their effects on left ventricular function after transplanted into acute myocardial ischemia rat. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci 19: 1043–1054. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ikutomi M et al. 2015. Diverse contribution of bone marrow-derived late-outgrowth endothelial progenitor cells to vascular repair under pulmonary arterial hypertension and arterial neointimal formation. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol 86: 121–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kanki K et al. 2016. Bone marrow-derived endothelial progenitor cells reduce recurrent miscarriage in gestation. Cell Transplant 25: 2187–2197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang R et al. 2017. The therapeutic value of bone marrow-derived endothelial progenitor cell transplantation after intracerebral hemorrhage in rats. Front. Neurol 8: 174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bai YY et al. 2015. Bone marrow endothelial progenitor cell transplantation after ischemic stroke: an investigation into its possible mechanism. CNS Neurosci. Ther 21: 877–886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Garbuzova-Davis S et al. 2017. Intravenously transplanted human bone marrow endothelial progenitor cells engraft within brain capillaries, preserve mitochondrial morphology, and display pinocytotic activity toward blood-brain barrier repair in ischemic stroke rats. Stem Cells 35: 1246–1258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang Z et al. 2015. Bone marrow stromal cell transplantation through tail vein injection promotes angiogenesis and vascular endothelial growth factor expression in cerebral infarct area in rats. Cytotherapy 17: 1200–1212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Park E et al. 2017. Bone-marrow-derived endothelial progenitor cell treatment in a model of lateral fluid percussion injury in rats: evaluation of acute and subacute outcome measures. J. Neurotrauma 34: 2801–2811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen C et al. 2017. Transplantation of amniotic scaffold seeded mesenchymal stem cells and/or endothelial progenitor cells from bone marrow to efficiently repair 3-cm circumferential urethral defect in model dogs. Tissue Eng. Part A 10.1089/ten.TEA.2016.0518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Invernizzi R et al. 2017. Vascular endothelial growth factor overexpression in myelodysplastic syndrome bone marrow cells: biological and clinical implications. Leuk. Lymphoma 58: 1711–1720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lamanuzzi A et al. 2016. Role of erythropoietin in the angiogenic activity of bone marrow endothelial cells of MGUS and multiple myeloma patients. Oncotarget 7: 14510–14521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bosse RC et al. 2016. Chemosensitizing AML cells by targeting bone marrow endothelial cells. Exp. Hematol 44: 363–377e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pizzo RJ et al. 2016. Phenotypic, genotypic, and functional characterization of normal and acute myeloid leukemia-derived marrow endothelial cells. Exp. Hematol 44: 378–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bonfim-Silva R et al. 2017. Bone marrow-derived cells are recruited by the melanoma tumor with endothelial cells contributing to tumor vasculature. Clin. Transl. Oncol 19: 125–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Teraa M et al. 2015. Effect of repetitive intra-arterial infusion of bone marrow mononuclear cells in patients with no-option limb ischemia: the randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled Rejuvenating Endothelial Progenitor Cells via Transcutaneous Intra-arterial Supplementation (JUVENTAS) trial. Circulation 131: 851–860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kawamoto A et al. 2009. Intramuscular transplantation of G-CSF-mobilized CD34(+) cells in patients with critical limb ischemia: a phase I/IIa, multicenter, single-blinded, dose-escalation clinical trial. Stem Cells 27: 2857–2864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kuroda R et al. 2014. Local transplantation of granulocyte colony stimulating factor-mobilized CD34+ cells for patients with femoral and tibial nonunion: pilot clinical trial. Stem Cells Transl. Med 3: 128–134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Matsumoto K et al. 2001. Liver organogenesis promoted by endothelial cells prior to vascular function. Science 294: 559–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang B et al. 2015. Self-renewing diploid Axin2(+) cells fuel homeostatic renewal of the liver. Nature 524: 180–185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ding BS et al. 2011. Endothelial-derived angiocrine signals induce and sustain regenerative lung alveolarization. Cell 147: 539–553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rafii S et al. 2015. Platelet-derived SDF-1 primes the pulmonary capillary vascular niche to drive lung alveolar regeneration. Nat. Cell Biol 17: 123–136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hase M et al. 1994. Classification of signals for blocking apoptosis in vascular endothelial cells.J.Biochem 116:905–909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gimbrone MA Jr., Cotran RS & Folkman J. 1974. Human vascular endothelial cells in culture. Growth and DNA synthesis. J. Cell Biol 60: 673–684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brindle NP 1993. Growth factors in endothelial regeneration. Cardiovasc. Res 27: 1162–1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gospodarowicz D et al. 1976. Clonal growth of bovine vascular endothelial cells: fibroblast growth factor as a survival agent. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 73: 4120–4124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Araki S et al. 1990. Apoptosis of vascular endothelial cells by fibroblast growth factor deprivation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 168: 1194–1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Seandel M et al. 2008. Generation of a functional and durable vascular niche by the adenoviral E4ORF1 gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105: 19288–19293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kobayashi H et al. 2010. Angiocrine factors from Aktactivated endothelial cells balance self-renewal and differentiation of haematopoietic stem cells. Nat. Cell Biol 12: 1046–1056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ramalingam R et al. 1999. E1(−)E4(+) adenoviral gene transfer vectors function as a “pro-life” signal to promote survival of primary human endothelial cells. Blood 93: 2936–2944. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tauber B & Dobner T. 2001. Molecular regulation and biological function of adenovirus early genes: the E4 ORFs. Gene 278: 1–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhang F et al. 2004. Adenovirus E4 gene promotes selective endothelial cell survival and angiogenesis via activation of the vascular endothelial-cadherin/Akt signaling pathway. J. Biol. Chem 279: 11760–11766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chung SH et al. 2007. A new crucial protein interaction element that targets the adenovirus E4-ORF1 oncoprotein to membrane vesicles. J. Virol 81: 4787–4797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.O’Shea C et al. 2005. Adenoviral proteins mimic nutrient/growth signals to activate the mTOR pathway for viral replication. EMBO J. 24: 1211–1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Westerweel PE et al. 2013. Impaired endothelial progenitor cell mobilization and dysfunctional bone marrow stroma in diabetes mellitus. PLoS One 8: e60357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bongso A & Lee E. 2010. Stem Cells: From Bench to Bedside. Singapore: World Scientific Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rodolfa K, Di Giorgio FP & Sullivan S. 2007. Defined reprogramming: a vehicle for changing the differentiated state. Differentiation 75: 577–579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schmitt A et al. 2012. Application of stem cells in orthopedics. Stem Cells Int. 2012: 394962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.da Silva Meirelles L, Chagastelles PC & Nardi NB. 2006. Mesenchymal stem cells reside in virtually all post-natal organs and tissues. J. Cell Sci 119: 2204–2213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Caplan AI 2009. New era of cell-based orthopedic therapies. Tissue Eng. Part B Rev 15: 195–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Murray IR et al. 2014. Recent insights into the identity of mesenchymal stem cells: implications for orthopaedic applications. Bone Joint J. 96-B: 291–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Petrou IG et al. 2014. Cell therapies for tendons: old cell choice for modern innovation. Swiss Med. Wkly. 144: w13989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kamei N et al. 2010. Lnk deletion reinforces the function of bone marrow progenitors in promoting neovascularization and astrogliosis following spinal cord injury. Stem Cells 28: 365–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tei K et al. 2008. Administrations of peripheral blood CD34-positive cells contribute to medial collateral ligament healing via vasculogenesis. Stem Cells 26: 819–830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kawakami Y et al. 2017. Anterior cruciate ligament-derived stem cells transduced with BMP2 accelerate graft-bone integration after ACL reconstruction. Am. J. Sports Med. 45: 584–597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gulotta LV et al. 2009. Application of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells in a rotator cuff repair model. Am. J. Sports Med 37: 2126–2133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chong AK et al. 2007. Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells influence early tendon-healing in a rabbit achilles tendon model. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am 89: 74–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Awad HA et al. 2003. Repair of patellar tendon injuries using a cell–collagen composite.J.Orthop.Res 21:420–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Juncosa-Melvin N et al. 2006. The effect of autologous mesenchymal stem cells on the biomechanics and histology of gel–collagen sponge constructs used for rabbit patellar tendon repair. Tissue Eng. 12: 369–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Omae H et al. 2012. Engineered tendon with decellularized xenotendon slices and bone marrow stromal cells: an in vivo animal study. J. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med 6: 238–244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Friedenstein AJ, Chailakhjan RK & Lalykina KS. 1970. The development of fibroblast colonies in monolayer cultures of guinea-pig bone marrow and spleen cells. Cell Tissue Kinet. 3: 393–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gulotta LV & Rodeo SA. 2011. Emerging ideas: evaluation of stem cells genetically modified with scleraxis to improve rotator cuff healing. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res 469: 2977–2980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Degen RM et al. 2016. The effect of purified human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells on rotator cuff tendon healing in an athymic rat. Arthroscopy 32: 2435–2443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zuk PA et al. 2002. Human adipose tissue is a source of multipotent stem cells. Mol. Biol. Cell 13: 4279–4295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Oh JH et al. 2014. 2013 Neer Award: effect of the adipose-derived stem cell for the improvement of fatty degeneration and rotator cuff healing in rabbit model. J. Shoulder Elbow Surg 23: 445–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Valencia Mora M et al. 2014. Application of adipose tissue-derived stem cells in a rat rotator cuff repair model. Injury 45(Suppl. 4): S22–S27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Eliasberg CD et al. 2017. Perivascular stem cells diminish muscle atrophy following massive rotator cuff tears in a small animal model. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am 99: 331–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sakaguchi Y et al. 2005. Comparison of human stem cells derived from various mesenchymal tissues: superiority of synovium as a cell source. Arthritis Rheum. 52: 2521–2529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Nakagawa Y et al. 2015. Synovial mesenchymal stem cells promote healing after meniscal repair in microminipigs. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 23: 1007–1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sekiya I et al. 2015. Arthroscopic transplantation of synovial stem cells improves clinical outcomes in knees with cartilage defects. Clin. Orthop. Relat 473: 2316–2326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ju Y-J et al. 2008. Synovial mesenchymal stem cells accelerate early remodeling of tendon–bone healing. Cell Tissue Res. 332: 469–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Nagura I et al. 2016. Characterization of progenitor cells derived from torn human rotator cuff tendons by gene expression patterns of chondrogenesis, osteogenesis, and adipogenesis. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 11: 40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lee CH et al. 2015. Harnessing endogenous stem/ progenitor cells for tendon regeneration. J. Clin. Invest 125: 2690–2701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Seo B-M et al. 2004. Investigation of multipotent postnatal stem cells from human periodontal ligament. Lancet 364: 149–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Cheng M-T et al. 2010. Comparison of potentials between stem cells isolated from human anterior cruciate ligament and bone marrow for ligament tissue engineering. Tissue Eng. Part A 16: 2237–2253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Schweitzer R et al. 2001. Analysis of the tendon cell fate using Scleraxis, aspecific marker for tendons and ligaments. Development 128: 3855–3866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Thomopoulos S et al. 2007. Decreased muscle loading delays maturation of the tendon enthesis during postnatal development. J. Orthop. Res 25: 1154–1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Schwartz AG et al. 2013. Muscle loading is necessary for the formation of a functional tendon enthesis. Bone 55: 44–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Thomopoulos S, Genin GM & Galatz LM. 2010. The development and morphogenesis of the tendon-to-bone insertion—what development can teach us about healing. J. Musculoskelet. Neuronal. Interact 10: 35–45. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Apostolakos J et al. 2014. The enthesis: a review of the tendon-to-bone insertion. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J. 4: 333–342. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Nourissat G, Berenbaum F & Duprez D. 2015. Tendon injury: from biology to tendon repair. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol 11: 223–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Angeline ME & Rodeo SA. 2012. Biologics in the management of rotator cuff surgery. Clin. Sports Med 31: 645–663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kovacevic D et al. 2011. Calcium–phosphate matrix with or without TGF-beta3 improves tendon-bone healing after rotator cuff repair. Am. J. Sports Med. 39: 811–819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Zhang F et al. 2003. Effect of vascular endothelial growth factor on rat Achilles tendon healing. Plast. Reconstr. Surg 112: 1613–1619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Yoshikawa T et al. 2006. Effects of local administration of vascular endothelial growth factor on mechanical characteristics of the semitendinosus tendon graft after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction in sheep. Am. J. Sports Med 34: 1918–1925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kovacevic D et al. 2015. rhPDGF-BB promotes early healing in a rat rotator cuff repair model. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 473: 1644–1654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Ide J et al. 2009. The effect of a local application of fibroblast growth factor-2 on tendon-to-bone remodeling in rats with acute injury and repair of the supraspinatus tendon. J. Shoulder Elbow Surg 18: 391–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Rodeo SA 2016. Biologic approaches in sports medicine: potential, perils, and paths forward. Am. J. Sports Med 44: 1657–1659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Lebaschi AH et al. 2017. Murine supraspinatus tendon detachment and repair model augmented with tendonderived, activated endothelial cells: a new concept in biologic enhancement of tendon-to-bone healing. Orthop. J. Sports Med. 5(7 Suppl. 6). 10.1177/2325967117S00444. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Lammert E, Cleaver O & Melton D. 2001. Induction of pancreatic differentiation by signals from blood vessels. Science 294: 564–567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Yancopoulos GD et al. 2000. Vascular-specific growth factors and blood vessel formation. Nature 407: 242–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Mathieu C et al. 2008. Endothelial cell-derived bone morphogenetic proteins control proliferation of neural stem/progenitor cells. Mol. Cell. Neurosci 38: 569–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Tachibana K et al. 1998. The chemokine receptor CXCR4 is essential for vascularization of the gastrointestinal tract. Nature 393: 591–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Pirtskhalaishvili G & Nelson JB. 2000. Endothelium-derived factors as paracrine mediators of prostate cancer progression. Prostate 44: 77–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Potente M et al. 2005. Involvement of Foxo transcription factors in angiogenesis and postnatal neovascularization. J. Clin. Investig 115: 2382–2392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Zeng Q et al. 2005. Crosstalk between tumor and endothelial cells promotes tumor angiogenesis by MAPK activation of Notch signaling. Cancer cell 8: 13–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Fernandez L et al. 2008. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha and endothelial cells modulate Notch signaling in the bone marrow microenvironment during inflammation. Exp. Hematol 36: 545–558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Lammert E, Cleaver O & Melton D. 2003. Role of endothelial cells in early pancreas and liver development. Mech. Dev 120: 59–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Nikolova G, Strilic B & Lammert E. 2007. The vascular niche and its basement membrane. Trends Cell Bio 17: 19–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Koistinen P et al. 2001. Regulation of the acute myeloid leukemia cell line OCI/AML-2 by endothelial nitric oxide synthase under the control of a vascular endothelial growth factor signaling system. Leukemia 15: 1433–1441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Ramirez-Castillejo C et al. 2006. Pigment epithelium-derived factor is a niche signal for neural stem cell renewal. Nat. Neurosci. 9: 331–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Carmeliet P & Collen D. 2000. Molecular basis of angiogenesis. Role of VEGF and VE-cadherin. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci 902: 249–262; discussion 262–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Ding BS et al. 2010. Inductive angiocrine signals from sinusoidal endothelium are required for liver regeneration. Nature 468: 310–315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Rocha AS et al. 2015. The angiocrine factor rspondin3 is a key determinant of liver zonation. Cell Reports 13: 1757–1764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Lee JH et al. 2014. Lung stem cell differentiation in mice directed by endothelial cells via a BMP4-NFATc1-thrombospondin-1 axis. Cell 156: 440–455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]