Summary

For nearly half a century, jobs have become increasingly characterized by employment insecurity. We examined the implications for sleep disturbance with cross-sectional data from the European Working Conditions Survey (2010). A group of 24,553 workers between the ages of 25 and 65 years in 31 European countries were asked to indicate whether they suffered from “insomnia or general sleep difficulties” in the past 12 months. We employed logistic regression to model the association between employment insecurity and sleep disturbance for all countries combined and each individual country. For all countries combined, employment insecurity increased the odds of reporting insomnia or general sleep difficulties in the past 12 months. Each unit increase in employment insecurity elevated the odds of sleep disturbance by approximately 47%. This finding was remarkably consistent across 27 of 31 European countries, including Albania, Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Turkey and UK. These results persisted with adjustments for age, gender, immigrant status, household size, partnership status, number of children, child care, elder care, education, earner status, precarious employment status, workplace sector, workplace tenure and workplace size. Employment insecurity was unrelated to sleep disturbance in four European countries: Malta, Poland, Portugal and Romania. Our research continues recent efforts to reveal the human costs associated with working in neoliberal postindustrial labour markets. Our analyses contribute to the external validity of previous research by exploring the impact of employment insecurity across European countries.

Keywords: insomnia, stress, work

1 |. INTRODUCTION

For nearly three decades following World War II, the standard of employment in Western countries included job security, competitive wages, health care and retirement benefits. Since the mid-1970s, however, we have witnessed the cumulative erosion of these standards across industrialized nations (Crowley, Tope, Chamberlain, & Hodson, 2010; Kalleberg, 2011; Rodgers & Rodgers, 1989). Largely incentivized by neoliberalism and globalization, jobs are now increasingly characterized by insecure contracts, low/stagnant wages and meagre benefits. Labour market scholars refer to these new employment conditions as “non-standard employment”, “flexible labour”, “precarious work”, “contingent work” and “insecure work” (Beard & Edwards, 1995; Bentolila & Saint-Paul, 1992; Connelly & Gallagher, 2004; Glavin, 2013; Kalleberg, 2011; Näswall & De Witte, 2003; Rodgers & Rodgers, 1989).

We currently know very little about the association between employment insecurity and sleep-related outcomes. Most studies linking employment and sleep examine differences between employment statuses and the impact of precise working conditions. Key findings from previous research suggest that unemployment, excessive demands, work–family conflict, hazardous conditions, night shifts, strained relations with co-workers and management, lack of control and general discomfort in the workplace are significant risk factors for a range of poor sleep outcomes, including difficulty falling asleep, waking frequently in the night, short sleep, insomnia and other chronic sleep problems (Basner et al., 2007; Berkman, Buxton, Ertel, & Okechukwu, 2010; Burgard & Ailshire, 2009; Crain et al., 2014; Grandner et al., 2010, 2015; Grandner, Hale, et al., 2012; Henry, McClellen, Rosenthal, Dedrick, & Gosdin, 2008; Hill, Burdette, & Hale, 2009; Krueger & Friedman, 2009; Li, Wing, Ho, & Fong, 2002; Nomura, Nakao, Takeuchi, & Yano, 2009; Paine, Gander, Harris, & Reid, 2004; Palmer et al., 2017; Patel, Grandner, Xie, Branas, & Gooneratne, 2010; Virtanen et al., 2008).

Although this body of work provides an important foundation, it is important for our research to reflect changing economies by focussing more on the role of employment insecurity within the population of workers. Our review of the literature revealed only a handful of studies focusing on employment insecurity and sleep. Research from at least five countries (Canada, South Korea, Sweden, UK and USA) has shown that anticipating a change in employment, the possibility of being terminated or laid off, uncertain prospects for advancement, dubious employability, feeling insecure in one’s job, and uncertainty with respect to earnings and scheduling are associated with poorer sleep quality and higher rates of insomnia, and other non-specific sleep problems (Burgard & Ailshire, 2009; Ferrie, Shipley, Marmot, Stansfeld, & Smith, 1998; Kim et al., 2011; Lewchuk, Clarke, & Wolff, 2008; Palmer et al., 2017; Park, Nakata, Swanson, & Chun, 2013; Virtanen, Janlert, & Hammarström, 2011).

Because sleep is an adaptive behaviour, researchers speculate that the subjective experience of employment insecurity, including personal concerns about job stability, job opportunities and financial returns, may undermine the ability of workers to initiate and/or maintain sleep through various physiological and emotional pathways (Burgard & Ailshire, 2009; Kim et al., 2011; Park et al., 2013; Virtanen et al., 2011). For example, anticipating unemployment or perceiving limited opportunities for advancement could elicit short-term feelings of annoyance, fear and hopelessness. These feelings could conceivably activate the stress response and trigger the release of stress hormones (epinephrine and cortisol) that promote mental and physiological arousal (McEwen, 1998; Sapolsky, 2004; Selye, 1978). When employment insecurity is experienced as a structural condition in one’s life, frequent bouts of emotional distress could eventually escalate to more serious psychiatric disorders (e.g. hostility, anxietyand depression).

In this study, we build on previous research by examining the association between employment insecurity and sleep disturbance across 31 European countries. In accordance with previous studies, we expect that employment insecurity will be positively associated with sleep disturbance.

2 |. METHODS

2.1 |. Data

The data for this study come from the 2010 European Working Conditions Survey (EWCS; https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/surveys/european-working-conditions-surveys/fifth-european-working-conditions-survey-2010). The EWCS employed multi-stage, stratified, random samples of Albania, Norway, Turkey and all 28 European Union member countries. The population included all employed residents of these countries who were 15 years or older (16 years or older in Norway, Spain and UK). Respondents were considered employed if they had worked for pay or profit for at least 1 hr in the week preceding the interview. This sampling design created a representative sample of the workforce in each country (Boeri, Lucifora, & Murphy, 2013). The average response rate across countries is 44.2%, ranging from 31.3% in Spain to 73.5% in Latvia (Parent-Thirion, Fernández Macías, Hurley, & Vermeylen, 2010). All surveys were administered face-to-face in the national language(s) of each country, outside of the workplace. Interviews lasted 44 min on average. To better isolate workers who have completed their educations, we limited our analytic sample to respondents between the ages of 25 and 65 years. This sample restriction included 24,553 workers from 31 countries.

2.2 |. Measures

Sleep disturbance is measured with a single item. Respondents were asked to indicate whether they suffered from “insomnia or general sleep difficulties” in the past 12 months. Responses to this item were dummy coded (1) yes and (0) no. This single item lacks reliability, but we believe it is a valid measure of sleep quality. Measures of self-reported sleep disturbance are consistent with clinical practise, as health professionals regularly identify sleep problems using patient reports of symptoms. Our measure is at least conceptually related to items from several established sleep inventories, including, for example, the Sleep Disorders Inventory (“Are you bothered by restless or fitful sleep?” “Do you usually have difficulty falling asleep at the beginning of the sleep period?”), the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (“Wake up in the middle of the night or early morning?”), and the Iowa Sleep Disturbances Inventory (“I have trouble staying asleep.” “I have trouble getting my sleep into a proper routine.”). In supplemental analyses (not shown), we confirmed the construct validity of our sleep disturbance measure through strong positive associations with self-reports of “overall fatigue” (odds ratio [OR] = 5.68, p < .001), “depression or anxiety” (OR = 6.70, p < .001), and “fair/bad/very bad” general health status (OR = 2.86, p < .001).

Employment insecurity is measured as the mean response to four items (α = 0.57). Items and component loadings are presented in Table 1. These items assess several dimensions of subjective employment insecurity, including experiences with contract insecurity (Item 1), financial insecurity (Item 2), mobility insecurity (Item 3), and organizational insecurity (Item 4). Component loadings were estimated using principal components analysis, specifying a minimum eigenvalue of 1.00, with varimax rotation. We observed a single component with an eigenvalue of 1.76. All component loadings exceeded 0.60. To account for mixed question formats and response categories, each employment insecurity item was standardized before indexing.

TABLE 1.

Items and principal component loadings for employment insecurity (n = 24,553)

| Items | Responses categories | Loadings |

|---|---|---|

| 1. I might lose my job in 6 months. |

(1) Strongly disagree – (5) Strongly agree |

0.63 |

| 2. Is your household able to make ends meet …? |

(1) Very easily – (6) With great difficulty |

0.67 |

| 3. My job offers good prospects. |

(1) Strongly agree – (5) Strongly disagree |

0.64 |

| 3. I feel at home in this organization |

(1) Strongly agree – (5) Strongly disagree |

0.71 |

Rotation (Varimax).

Bartlett’s test of sphericity (χ2 = 8,126.53, p < 0.001).

Eigenvalue (1.75).

Variance explained (43.90%).

Source: European Working Conditions Survey (2010).

Subsequent analyses control for background variables that may influence the association between employment insecurity and sleep disturbance. These variables include Age (in years), Gender (1 = female, 0 = male), Immigrant Status (1 = immigrant, 0 = non-immigrant), Household Size (count of people in the household), Partnership Status (1 = living with spouse/partner, 0 = otherwise), Number of Children (count of children in the household), Child Care (1 = cares for children at least once per week, 0 = otherwise), Elder Care (1 = cares for elderly/disabled relatives at least once per week, 0 = otherwise), Education (1 = pre-primacy education to 7 = second stage of tertiary education), Precarious Employment Status (1 = self-employed without regular pay or employed on a fixed-term contract for less than a year or is employed by a temporary agency or apprenticeship scheme or employed with no contract at all, 0 = standard employment), Workplace Sector (dummy variables for private sector, non-profit sector, joint public/private sector, with public sector serving as the reference category), Workplace Tenure (in years), Workplace Size (1 = 1 to 8 = 500 and over), Earner Status (1 = main contributor to household income, 0 = otherwise).

2.3 |. Statistical procedures

Table 2 provides descriptive statistics for our combined sample. In multivariate analyses, we employ binary logistic regression to model our dichotomous sleep disturbance measure. Tables 3 and 4 provide ORs and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the association between employment insecurity and sleep disturbance for all 31 countries combined and each individual country. In our analyses of all 31 countries combined, we employ robust standard errors clustered by country (Bryan & Jenkins, 2015). The ORs represent the estimated difference in the odds of reporting sleep disturbance for those who are 1 unit apart on employment insecurity, controlling or holding constant all background variables in the model. In our Results section, we convert ORs to percentage changes by subtracting 1 and then multiplying by 100 ([OR – 1]100). This conversion yields the percent change in the odds of sleep disturbance for those who are 1 unit apart on employment insecurity.

TABLE 2.

Descriptive statistics (n = 24,553)

| Range | Mean | Standard deviation |

Reliability | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sleep disturbance | 0–1 | 0.21 | ||

| Employment insecurity | −2.18–3.24 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.57 |

| Precarious employment | 0–1 | 0.16 | ||

| Public sector | 0–1 | 0.28 | ||

| Private sector | 0–1 | 0.66 | ||

| Public/private sector | 0–1 | 0.04 | ||

| Non-profit sector | 0–1 | 0.01 | ||

| Workplace tenure | 0–50 | 10.85 | 9.67 | |

| Workplace size | 1–8 | 4.03 | 1.91 | |

| Age (years) | 25–65 | 43.06 | 10.24 | |

| Female | 0–1 | 0.50 | ||

| Immigrant | 0–1 | 0.13 | ||

| Household size | 0–16 | 3.03 | 1.36 | |

| Partnership status | 0–1 | 0.73 | ||

| Number of children | 0–5 | 1.03 | 1.05 | |

| Child care provider | 0–1 | 0.55 | ||

| Elder care provider | 0–1 | 0.16 | ||

| Education | 1–7 | 4.40 | 1.30 | |

| Primary earner | 0–1 | 0.66 |

Source: European Working Conditions Survey (2010).

TABLE 3.

Binary logistic regression of sleep disturbance on employment insecurity and background factors

| All countries (n = 24,553) |

Albania (n = 524) |

Austria (n = 635) |

Belgium (n = 2,363) |

Bulgaria (n = 568) |

Croatia (n = 525) |

Cyprus (n = 726) |

Czech Republic (n = 460) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Employment insecurity | 1.47*** (1.38, 1.56) |

1.30* (1.01, 1.68) |

1.46** (1.12, 1.91) |

1.69*** (1.49, 1.91) |

1.66*** (1.29, 2.13) |

1.49** (1.13, 1.96) |

1.28* (1.02, 1.61) |

1.44* (1.06, 1.95) |

| Model χ2 | 832.39*** | 38.65** | 33.05 | 139.28*** | 71.51*** | 35.25* | 33.88** | 70.30*** |

|

Denmark (n = 700) |

Estonia (n = 613) |

Finland (n = 828) |

France (n = 1,947) |

Germany (n = 1,441) |

Greece (n = 483) |

Hungary (n = 610) |

Ireland (n = 591) |

|

| Employment insecurity | 1.52*** (1.20, 1.93) |

1.33** (1.07, 1.65) |

1.61*** (1.32, 1.95) |

1.43*** (1.28, 1.59) |

1.49*** (1.29, 1.73) |

2.04*** (1.42, 2.92) |

1.72*** (1.35, 2.17) |

1.82*** (1.31, 2.51) |

| Model χ2 | 60.92* | 35.78* | 51.61*** | 70.16*** | 97.79*** | 40.77** | 44.15** | 53.44*** |

Shown are ORs and 95% CIs.

p < 0.05.

p < 0.01.

p < 0.001 (two-tailed tests). All models control for age, gender, immigrant status, household size, partnership status, number of children, child care, elder care, education, earner status, employment sector, workplace size, precarious employment status and employment tenure. Our analyses for Albania and Croatia do not control for immigrant status because no respondents reported being an immigrant in those samples. All countries analyses employ robust standard errors clustered by country.

Source: European Working Conditions Survey (2010).

TABLE 4.

Binary logistic regression of sleep disturbance on employment insecurity and background factors

| Italy (n = 922) |

Latvia (n = 569) |

Lithuania (n = 673) |

Luxembourg (n = 592) |

Malta (n = 628) |

the Netherlands (n = 600) |

Norway (n = 822) |

Poland (n = 781) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Employment insecurity |

1.72*** (1.38, 2.17) |

1.39** (1.14, 1.71) |

1.72*** (1.40, 2.10) |

1.62*** (1.28, 2.05) |

1.22 (0.89, 1.67) |

1.68*** (1.24, 2.27) |

2.73*** (1.98, 3.75) |

1.28 (0.98, 1.65) |

| Model χ2 | 48.33*** | 38.04* | 58.32*** | 47.72** | 18.79 | 39.45* | 91.27*** | 37.32* |

| Portugal (n = 571) |

Romania (n = 479) |

Slovakia (n = 502) |

Slovenia (n = 1,056) |

Spain (n = 542) |

Sweden (n = 736) |

Turkey (n = 1,053) |

UK (n = 1,013) |

|

| Employment insecurity | 1.29 (0.97, 1.59) |

0.95 (0.70, 1.28) |

1.54** (1.13, 2.11) |

1.65*** (1.39, 1.95) |

1.66** (1.20, 2.29) |

1.49*** (1.19, 1.87) |

1.54*** (1.33, 1.79) |

1.61*** (1.33, 1.95) |

| Model χ2 | 60.29*** | 35.68* | 37.36* | 72.24*** | 42.33* | 57.86*** | 64.91*** | 63.62*** |

Shown are ORs and 95% CIs.

p < 0.05.

p < 0.01.

p < 0.001 (two-tailed tests). All models control for age, gender, immigrant status, household size, partnership status, number of children, child care, elder care, education, earner status, employment sector, workplace size, precarious employment status and employment tenure. Our analyses for Turkey do not control for immigrant status because no respondents reported being an immigrant in that sample. All countries analyses employ robust standard errors clustered by country.

Source: European Working Conditions Survey (2010).

3 |. RESULTS

3.1 |. Descriptive analyses

As shown in Table 2, approximately 21% of the combined sample reported sleep disturbance in the past 12 months. Although this estimate is consistent with previous epidemiological studies of general sleep disturbance (Grandner et al., 2010; Grandner, Martin, et al., 2012), we observed considerable variation across countries (not shown). The countries with the highest rates of sleep disturbance include Finland (33%), France (33%), Turkey (32%), Latvia (30%) and Lithuania (27%). The countries with the lowest rates of sleep disturbance include Malta (9%), Greece (11%), Ireland (11%), Norway (13%) and Spain (13%). The average respondent reported moderate levels of employment insecurity. Nearly 16% of the sample was employed in a precarious job, without a fixed- or long-term contract. With respect to workplace sector, most respondents were employed in the private sector (66%) or the public sector (28%). The mean workplace tenure was nearly 11 years. The mean workplace size was between 10 and 49 employees. The average age of the sample was approximately 43 years. The sample was evenly split between women and men. Only 13% of respondents identified as immigrants. The mean level of education for the sample was “secondary education”.

3.2 |. Multivariate analyses

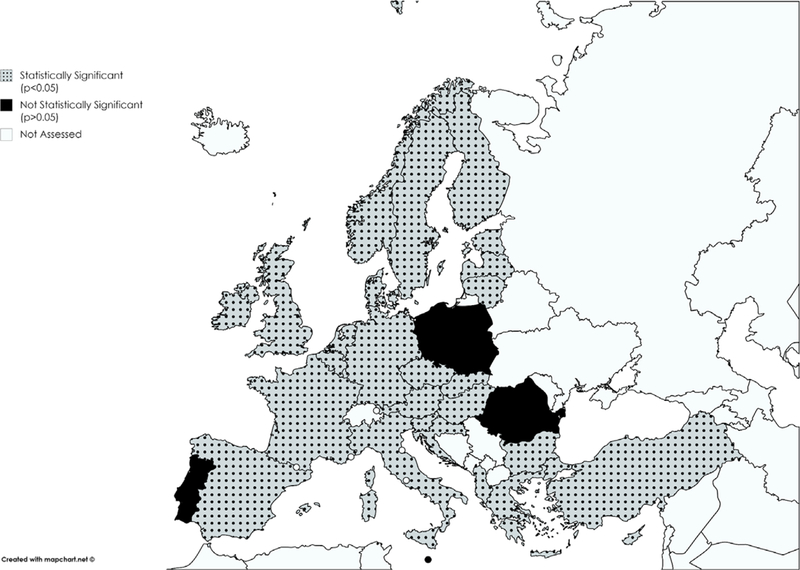

Tables 3 and 4 present our multivariate regression analyses. For all countries combined, employment insecurity increased the odds of reporting insomnia or general sleep difficulties in the past 12 months. More specifically, each unit increase in employment insecurity elevated the odds of sleep disturbance by approximately 47% ([1.47 – 1]100). This finding was remarkably consistent across 27 of 31 European countries, including Albania, Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Turkey and UK. These results persisted with adjustments for age, gender, immigrant status, household size, partnership status, number of children, child care, elder care, education, earner status, precarious employment status, workplace sector, workplace tenure and workplace size. Employment insecurity was unrelated to sleep disturbance in four European countries: Malta, Poland, Portugal and Romania. We were unable to control for immigrant status in our analyses for Albania, Croatia and Turkey because no respondents reported being an immigrant in those samples. Figure 1 provides a map of Europe to further illustrate our central findings.

FIGURE 1.

The association between employment insecurity and sleep disturbance.

Although we are not primarily concerned with our background variables, we observed several statistically significant (p < 0.05) patterns in our multivariate analyses (not shown). The odds of sleep disturbance were often higher for older adults and women. The age pattern was observed in Albania, Belgium, Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania and Spain. The gender pattern was observed in Czech Republic, Germany, Hungary, Italy, Latvia, Portugal, Romania, Slovakia and UK. The odds of sleep disturbance were often higher for respondents who reported providing child care and elder care. The child care pattern was observed in Croatia, Lithuania, Portugal, Romania, Slovenia and Sweden. The elder care pattern was observed in Albania, Belgium, Estonia, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland and Portugal. There was also some evidence that the odds of sleep disturbance were higher for immigrants in France, Germany, Greece and the Netherlands. Our findings for household size, partnership status, number of children, education, earner status, precarious employment status, workplace sector, workplace tenure and workplace size were characteristically mixed in sign or statistically insignificant (p > 0.05).

4 |. DISCUSSION

In this study, we examined the association between employment insecurity and sleep disturbance in 31 European countries. In accordance with previous studies, we expected that employment insecurity would be positively associated with sleep disturbance. For the most part, this is what we found. For all countries combined and 27 individual European countries, employment insecurity increased the odds of reporting insomnia or general sleep difficulties in the past 12 months. Our results persisted with a range of adjustments for age, gender, immigrant status, household size, partnership status, number of children, child care, elder care, education, earner status, employment sector, workplace size, precarious employment status and employment tenure.

Our general findings confirm previous work conducted in Canada, South Korea, Sweden, UK and USA (Burgard & Ailshire, 2009; Ferrie et al., 1998; Kim et al., 2011; Lewchuk et al., 2008; Palmer et al., 2017; Park et al., 2013; Virtanen et al., 2011). Our results contribute to the external validity of these studies by confirming the positive association between employment insecurity and sleep disturbance in 23 other countries, including Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Slovakia, Slovenia and Turkey.

Our analyses should be considered within the context of three key limitations. Our first limitation is study design. Because our analyses are cross-sectional, no causal or temporal inferences can be made. Although we assume that employment insecurity can contribute to sleep disturbance, preexisting mental health issues could also lead workers to feel less secure in their jobs and to exhibit poorer sleep outcomes. Employment could lead to sleep disturbance through the mechanism of mental health (e.g. via anxiety symptoms). It is also plausible that employment insecurity could contribute to mental health issues through the mechanism of sleep, via disruption of the circadian rhythm. As a matter of construct validity, we observed that our measure of sleep disturbance was positively associated with self-ratings of “depression or anxiety”. Given our cross-sectional data, we cannot exclude these alternative models.

The question of mental health is complex. Self-ratings of depression/anxiety were explicitly excluded from our multivariate models because sleep and mental health are conceptually distinct causes of each other (Ford & Kamerow, 1989; Krystal, 2012; Roberts, Shema, Kaplan, & Strawbridge, 2000; Van Reeth et al., 2000). Krystal (2012:1,398) explains that “there is growing experimental evidence that the relationship between psychiatric disorders and sleep is complex and includes bidirectional causation”. If our focal associations were attenuated or even eliminated by controlling for mental health, it would be difficult to interpret these patterns in the absence of longitudinal data and a compelling theory about which comes first (sleep or mental health). We were also concerned about underestimating the association between employment insecurity and sleep disturbance. We are certain that our observed associations would be attenuated to some degree. As noted above, we would be unable to interpret the nature of the attenuation with our cross-sectional data. If mental health is serving as a mediator of the association between employment insecurity and sleep disturbance, we would grossly underestimate this association by adjusting for mental health. The key issue is whether our proposed conceptual model is at least theoretically viable. We argue that it is plausible for employment insecurity to undermine sleep without preexisting mental health issues. Our view is supported by the fact that the adults in our sample function well enough to be currently employed for pay in the community.

Our second limitation is our measurement of sleep disturbance. Although this measure demonstrated construct validity through strong associations with fatigue, mental health and physical health, single items are generally low in reliability. As a consequence, our analyses are likely to underestimate the association between employment insecurity and sleep disturbance.

Because the sleep measure is self-reported, responses are likely to reflect some unmeasured cultural differences. We addressed this issue by analysing each country individually, but more information is needed to establish how European workers construct and experience sleep-related issues.

Our third limitation is low response rates in several countries. Because low response rates contribute to sample bias, some of our estimates may not be generalizable to any specific population. While we are encouraged by the consistency of our results across European countries, additional research is needed to replicate work with more representative samples.

4.1 |. Conclusion

Although the veracity of our analyses is contingent upon replication using longitudinal data, more rigorous analytic strategies and established sleep measures that are more reliable and culturally informed, we provide consistent evidence of a positive association between employment insecurity and sleep disturbance across 27 European countries. Our research continues recent efforts to reveal the human costs associated with working in neoliberal postindustrial labour markets. Our analyses contribute to the external validity of previous research by exploring the impact of employment insecurity across European countries. More research is needed to explore previously unexamined countries and regions of the world. Future studies should address a range of questions. Does mental health mediate the association between employment insecurity and sleep disturbance? Do the adverse effects of employment insecurity vary by gender or age? Research along these lines would provide a more global and nuanced understanding of the ways in which employment insecurity might undermine sleep.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

REFERENCES

- Basner M, Fomberstein KM, Razavi FM, Banks S, William JH, Rosa RR, & Dinges DF (2007). American time use survey: Sleep time and its relationship to waking activities. Sleep, 30(9), 1085–1095. 10.1093/sleep/30.9.1085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beard KM, & Edwards JR (1995). Employees at risk: Contingent work and the psychological experience of contingent workers. Journal of Organizational Behavior (1986–1998), 109, 109–126. [Google Scholar]

- Bentolila S, & Saint-Paul G (1992). The macroeconomic impact of flexible labor contracts, with an application to Spain. European Economic Review, 36(5), 1013–1047. 10.1016/0014-2921(92)90043-V [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berkman LF, Buxton O, Ertel K, & Okechukwu C (2010). Managers’ practices related to work–family balance predict employee cardiovascular risk and sleep duration in extended care settings. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 15(3), 316–329. 10.1037/a0019721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boeri T, Lucifora C, & Murphy KJ (Eds) (2013). Executive remuneration and employee performance-related pay: A transatlantic perspective Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bryan ML, & Jenkins SP (2015). Multilevel modelling of country effects: A cautionary tale. European Sociological Review, 32(1), 3–22. 10.1093/esr/jcv059 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burgard SA, & Ailshire JA (2009). Putting work to bed: Stressful experiences on the job and sleep quality. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 50(4), 476–492. 10.1177/002214650905000407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connelly CE, & Gallagher DG (2004). Emerging trends in contingent work research. Journal of Management, 30(6), 959–983. 10.1016/j.jm.2004.06.008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crain TL, Hammer LB, Bodner T, Kossek EE, Moen P, Lilienthal R, & Buxton OM (2014). Work–family conflict, family-supportive supervisor behaviors (FSSB), and sleep outcomes. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 19(2), 155–167. 10.1037/a0036010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowley M, Tope D, Chamberlain LJ, & Hodson R (2010). Neo-Taylorism at work: Occupational change in the post-Fordist era. Social Problems, 57(3), 421–447. 10.1525/sp.2010.57.3.421 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrie JE, Shipley MJ, Marmot MG, Stansfeld S, & Smith GD (1998). The health effects of major organisational change and job insecurity. Social Science & Medicine, 46(2), 243–254. 10.1016/S0277-9536(97)00158-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford DE, & Kamerow DB (1989). Epidemiologic study of sleep disturbances and psychiatric disorders: An opportunity for prevention? JAMA, 262(11), 1479–1484. 10.1001/jama.1989.03430110069030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glavin P (2013). The impact of job insecurity and job degradation on the sense of personal control. Work and Occupations, 40(2), 115–142. 10.1177/0730888413481031 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grandner MA, Hale L, Jackson N, Patel NP, Gooneratne NS, & Troxel WM (2012). Perceived racial discrimination as an independent predictor of sleep disturbance and daytime fatigue. Behavioral Sleep Medicine, 10(4), 235–249. 10.1080/15402002.2012.654548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grandner MA, Jackson NJ, Izci-Balserak B, Gallagher RA, Murray-Bachmann R, Williams NJ, … Jean-Louis G. (2015). Social and behavioral determinants of perceived insufficient sleep. Frontiers in Neurology, 6, 112 10.3389/fneur.2015.00112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grandner MA, Martin JL, Patel NP, Jackson NJ, Gehrman PR, Pien G, … Gooneratne NS (2012). Age and sleep disturbances among American men and women: Data from the US Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Sleep, 35(3), 395–406. 10.5665/sleep.1704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grandner MA, Patel NP, Gehrman PR, Xie D, Sha D, Weaver T, & Gooneratne N (2010). Who gets the best sleep? Ethnic and socioeconomic factors related to sleep complaints. Sleep Medicine, 11 (5), 470–478. 10.1016/j.sleep.2009.10.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry D, McClellen D, Rosenthal L, Dedrick D, & Gosdin M (2008). Is sleep really for sissies? Understanding the role of work in insomnia in the US. Social Science & Medicine, 66(3), 715–726. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill TD, Burdette AM, & Hale L (2009). Neighborhood disorder, sleep quality, and psychological distress: Testing a model of structural amplification. Health & Place, 15(4), 1006–1013. 10.1016/j.healthplace.2009.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalleberg AL (2011). Good jobs, bad jobs: The rise of polarized and precarious employment in the United States, 1970’s to 2000’s New York: Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Kim HC, Kim BK, Min KB, Min JY, Hwang SH, & Park SG (2011). Association between job stress and insomnia in Korean workers. Journal of Occupational Health, 53(3), 164–174. 10.1539/joh.10-0032-OA [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger PM, & Friedman EM (2009). Sleep duration in the United States: A cross-sectional population-based study. American Journal of Epidemiology, 169(9), 1052–1063. 10.1093/aje/kwp023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krystal AD (2012). Psychiatric disorders and sleep. Neurologic Clinics, 30(4), 1389–1413. 10.1016/j.ncl.2012.08.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewchuk W, Clarke M, & De Wolff A (2008). Working without commitments: Precarious employment and health. Work, Employment and Society, 22(3), 387–406. 10.1177/0950017008093477 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li RHY, Wing YK, Ho SC, & Fong SYY (2002). Gender differences in insomnia – a study in the Hong Kong Chinese population. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 53(1), 601–609. 10.1016/S0022-3999(02)00437-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen BS (1998). Protective and damaging effects of stress mediators. New England Journal of Medicine, 338(3), 171–179. 10.1056/NEJM199801153380307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Näswall K, & De Witte H (2003). Who feels insecure in Europe? Predicting job insecurity from background variables. Economic and Industrial Democracy, 24(2), 189–215. 10.1177/0143831X03024002003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nomura K, Nakao M, Takeuchi T, & Yano E (2009). Associations of insomnia with job strain, control, and support among male Japanese workers. Sleep Medicine, 10(6), 626–629. 10.1016/j.sleep.2008.06.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paine SJ, Gander PH, Harris R, & Reid P (2004). Who reports insomnia? Relationships with age, sex, ethnicity, and socioeconomic deprivation. Sleep, 27(6), 1163–1169. 10.1093/sleep/27.6.1163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer KT, D’Angelo S, Harris EC, Linaker C, Sayer AA, Gale CR, … Walker-Bone K (2017). Sleep disturbance and the older worker: Findings from the Health and Employment after Fifty study. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health, 43(2), 136–145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parent-Thirion A, Fernández Macías E, Hurley J, & Vermeylen G (2010). Fifth European Working Conditions Survey, technical report Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities. [Google Scholar]

- Park JB, Nakata A, Swanson NG, & Chun H (2013). Organizational factors associated with work-related sleep problems in a nationally representative sample of Korean workers. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health, 86(2), 211–222. 10.1007/s00420-012-0759-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel NP, Grandner MA, Xie D, Branas CC, & Gooneratne N (2010). “Sleep disparity” in the population: Poor sleep quality is strongly associated with poverty and ethnicity. BMC Public Health, 10 (1), 475 10.1186/1471-2458-10-475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts RE, Shema SJ, Kaplan GA, & Strawbridge WJ (2000). Sleep complaints and depression in an aging cohort: A prospective perspective. American Journal of Psychiatry, 157(1), 81–88. 10.1176/ajp.157.1.81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers J, & Rodgers J (1989). Precarious jobs in labour market regulation: The growth of atypical employment in Western Europe Geneva: International Institute for Labour Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Sapolsky RM (2004). Why zebras don’t get ulcers New York: Times Books. [Google Scholar]

- Selye H (1978). The stress of life New York: McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Van Reeth O, Weibel L, Spiegel K, Leproult R, Dugovic C, & Maccari S (2000). Physiology of sleep (review)–interactions between stress and sleep: From basic research to clinical situations. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 4(2), 201–219. 10.1053/smrv.1999.0097 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Virtanen P, Janlert U, & Hammarström A (2011). Exposure to temporary employment and job insecurity: A longitudinal study of the health effects. Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 68(8), 570–574. 10.1136/oem.2010.054890 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Virtanen P, Vahtera J, Broms U, Sillanmäki L, Kivimäki M, & Koskenvuo M (2008). Employment trajectory as determinant of change in health-related lifestyle: The prospective HeSSup study. European Journal of Public Health, 18(5), 504–508. 10.1093/eurpub/ckn037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]