Abstract

Members of the neurotrophin family and in particular brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) regulate the response to rapid- and slow-acting chemical antidepressants and voluntary exercise. Recent work suggests that rapid-acting antidepressants that modulate N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor (NMDA-R) signaling (e.g. ketamine and GLYX-13) require expression of VGF (non-acronymic), the BDNF-inducible secreted neuronal protein and peptide precursor, for efficacy. In addition, the VGF-derived C-terminal peptide TLQP-62 (named by its 4 N-terminal amino acids and length) has antidepressant efficacy following icv or intra-hippocampal administration, in the forced swim test (FST). Similar to ketamine, the rapid antidepressant actions of TLQP-62 require BDNF expression, mTOR activation (rapamycin-sensitive), α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA) receptor activation (NBQX-sensitive), and are associated with GluR1 insertion. We review recent findings that identify a rapidly-induced autoregulatory feedback loop, which likely plays a critical role in sustained efficacy of rapid-acting antidepressants, depression-like behavior, and cognition, and requires VGF, its C-terminal peptide TLQP-62, BDNF/TrkB signaling, the mTOR pathway, and AMPA receptor activation and insertion.

Keywords: Antidepressant, Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF), Ketamine, Local Protein Synthesis, Major Depressive Disorder (MDD), VGF

Introduction

Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) modulates depression-like behavior and antidepressant efficacy: decreased BDNF levels are found in depressed patients (Karege et al. 2005; Shimizu et al. 2003), and BDNF infusion into the hippocampus or lateral ventricles produces antidepressant responses (Shirayama et al. 2002; Siuciak et al. 1997). Thus in the hippocampus, BDNF signaling modifies depressive behavior (Bjorkholm and Monteggia 2016; Jiang and Salton 2013). In addition, a coding sequence variant (Val66Met) in the human BDNF gene is associated with cognitive and behavioral deficits and childhood-onset mood disorder (Egan et al. 2003; Strauss et al. 2005). The functional impact of this BDNF polymorphism on depressive behavior and anxiety (Chen et al. 2006), and basic studies of BDNF sorting and release (Chen et al. 2005; Chen et al. 2004), demonstrate that altered trafficking and regulated secretion of BDNF drive behavioral outcomes. This and the association of ketamine’s antidepressant efficacy with a subject’s BDNF (Val/Met) genotype (Liu et al. 2012) suggest that local BDNF secretion regulates antidepressant responses.

BDNF regulates the expression of downstream genes, including robust induction of Vgf (non-acronymic, unrelated to VEGF), which encodes a neuropeptide precursor that is released via the regulated secretory pathway along with several VGF-derived peptides [reviewed in (Levi et al. 2004; Salton et al. 2000)]. Decreased VGF expression, resulting from germline or conditional Vgf gene ablation in mice, including targeted down-regulation in adult dorsal hippocampus (dHc), impacts depressive behavior, contextual fear, and hippocampal-dependent spatial memory (Bozdagi et al. 2008; Hahm et al. 1999; Hunsberger et al. 2007; Jiang et al. 2017; Lin et al. 2015). VGF C-terminal peptides AQEE-30 and TLQP-62 (named by the four N-terminal amino acids and length) have antidepressant efficacy (Hunsberger et al. 2007; Jiang et al. 2017; Li et al. 2017; Lin et al. 2014; Thakker-Varia et al. 2007), while TLQP-62 has also been shown to have pro-cognitive efficacy (Li et al. 2017; Lin et al. 2015). TLQP-62 functions via BDNF-dependent pathways (Bozdagi et al. 2008; Jiang et al. 2017; Lin et al. 2014; Lin et al. 2015), while the VGF1–617 proprotein plays a critical role in growth factor, hormone, and neurotransmitter storage in dense core vesicles (DCVs) and regulated secretion (Fargali et al. 2014; Stephens et al. 2017). Here we review recent findings that suggest dual requirements for BDNF and VGF (TLQP-62), perhaps synthesized and secreted locally at the synapse, in the response to rapid-acting antidepressant drugs like ketamine.

Role of BDNF and its Receptor TrkB in the Response to Rapid-Acting Antidepressants

BDNF, a member of the neurotrophin family, is widely synthesized in the CNS, in neurons and glia, where it regulates synaptic plasticity, and neuronal development and function (Park and Poo 2013; Parkhurst et al. 2013). BDNF actions are transduced through the high affinity tropomyosin receptor kinase B (TrkB) and through the low affinity p75 neurotrophin receptor. The critical role that BDNF/TrkB signaling plays in MDD and the efficacy of rapid-acting antidepressants has been recognized through association studies of patients with BDNF single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) (Egan et al. 2003; Strauss et al. 2005; Strauss et al. 2004), and through investigation of depression- and anxiety-like behaviors in BDNF-deficient animal models and their response to antidepressants [reviewed in (Bjorkholm and Monteggia 2016; Duman and Monteggia 2006; Jiang and Salton 2013; Krishnan and Nestler 2008)]. The best-characterized BDNF SNP located in the proBDNF region changes the encoded valine to methionine (Val66Met), which alters BDNF sorting and reduces activity-dependent regulated secretion, resulting in impaired cognition and mood disorders (Chen et al. 2005; Chen et al. 2006; Chen et al. 2004; Egan et al. 2003). Interestingly, knockin mouse models expressing variant human BDNF (Met66) have impaired working memory, increased anxiety and depression-like behavior, and reduced behavioral responses to conventional and rapid-acting antidepressants (Chen et al. 2006; Ghosal et al. 2018; Kato et al. 2017; Liu et al. 2012). Thus, BDNFMet/Met mice have decreased responses to long-term fluoxetine treatment in the open field and novelty-induced hypophagia tests (Chen et al. 2006), attenuated response to ketamine in the forced swim test (FST) (Liu et al. 2012), no significant response to GLYX-13 in the FST, novelty-suppressed feeding test (NSFT), and female urine-sniffing test (Kato et al. 2017), and lastly no significant responses to scopolamine in the FST or NSFT (Ghosal et al. 2018).

The rapid antidepressant effects of the ionotropic glutamatergic N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor blocker ketamine were shown to require BDNF and pathways downstream of its high-affinity receptor TrkB, and to require protein synthesis but not transcription, suggesting that BDNF may be locally translated in and secreted from dendrites (Autry et al. 2011; Lepack et al. 2016; Lepack et al. 2014; Lepack et al. 2015). Similar to ketamine, the antidepressant actions of GLYX-13, a novel glutamatergic compound and NMDA modulator with glycine-like partial agonist properties (Kato et al. 2017), and scopolamine, a nonselective muscarinic acetylcholine receptor antagonist (Ghosal et al. 2018), may also mechanistically depend on rapid desuppression of translation of select mRNAs (e.g. BDNF). Importantly, the antidepressant efficacies of scopolamine and GLYX-13, like ketamine, are blocked by inhibitors of mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) (Li et al. 2010; Liu et al. 2017; Voleti et al. 2013), and require activation of eukaryotic elongation factor 2 kinase (eEF2K) (Autry et al. 2011; Nosyreva et al. 2013). Local dendritic BDNF synthesis and secretion results at least in part from translation of the long 3’ untranslated region (UTR) BDNF mRNA isoform, which is transported to distal dendrites (An et al. 2008). Selective ablation of the long 3’UTR BDNF mRNA profoundly reduces activity-dependent BDNF secretion (An et al. 2008; Lau et al. 2010), impairs long-term potentiation (LTP) at dendritic synapses of hippocampal CA1 neurons (An et al. 2008) and GABA-dependent neurogenesis (Waterhouse et al. 2012), and results in hyperphagic obesity (Liao et al. 2012; Liao et al. 2015). Whether absence of the long 3’UTR BDNF mRNA also impacts depression-like behavior, antidepressant efficacy, and memory, as does the BDNF Val66Met SNP, remains to our knowledge unreported.

Contributions of the Secreted Protein and Peptide Precursor VGF to the Response to Rapid-Acting Antidepressants.

VGF was originally cloned based on its induction by neurotrophins, including nerve growth factor (NGF), BDNF, and others (Alder et al. 2003; Bonni et al. 1995; Levi et al. 1985; Salton et al. 1991), which stimulated investigation of its potential role in depression-like behavior and antidepressant efficacy. Interestingly, in hippocampus, VGF was identified as one of the most robustly regulated mRNAs by prolonged voluntary exercise, a potent antidepressant in rodents (Hunsberger et al. 2007). Concurrently, VGF regulation by learned helplessness and the forced swim test (FST) was shown (Thakker-Varia et al. 2007). These studies further identified antidepressant efficacy of VGF-derived C-terminal peptides TLQP-62 (Thakker-Varia et al. 2007) and AQEE-30 (Hunsberger et al. 2007), and a requirement for VGF expression in the antidepressant efficacy of exercise (Hunsberger et al. 2007). Subsequent reports have demonstrated a requirement for BDNF expression and BDNF/TrkB signaling in the antidepressant efficacy of TLQP-62 (Jiang et al. 2017; Li et al. 2017; Lin et al. 2014). Prolonged antidepressant efficacy of TLQP-62, measured in the FST three and six days after a single intra-hippocampal infusion (Thakker-Varia et al. 2007), or in the FST and TST, measured after 2 weeks of daily intra-hippocampal infusions (Lin et al. 2014), could result at least in part from TLQP-62-mediated stimulation of hippocampal progenitor proliferation (Thakker-Varia et al. 2014; Thakker-Varia et al. 2007). Rapid TLQP-62 antidepressant efficacy (30 min – 24 hr following intra-hippocampal delivery) in the FST (Jiang et al. 2017; Lin et al. 2014) has been shown, like the rapid-acting antidepressant ketamine, to require BDNF expression (Jiang et al. 2017; Lin et al. 2014), mTOR activity (rapamycin-sensitive) (Jiang et al. 2017), and glutamate receptor activity (NBQX-sensitive) (Jiang et al. 2017), suggesting a complementary, rapidly-initiated mechanism of action. Lastly, recent studies have revealed a critical role for the VGF1–617 proprotein in large dense core secretory vesicle (LDCV) biogenesis, in neuroendocrine adrenal medulla (Fargali et al. 2014) and in pancreatic beta cells, where it is required for glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (Stephens et al. 2017). Should VGF function similarly in the regulated secretory pathways of CNS neurons, altered VGF levels could also modulate activity-dependent BDNF release, and thus potentially depression-like behavior and antidepressant efficacy (Figure 1).

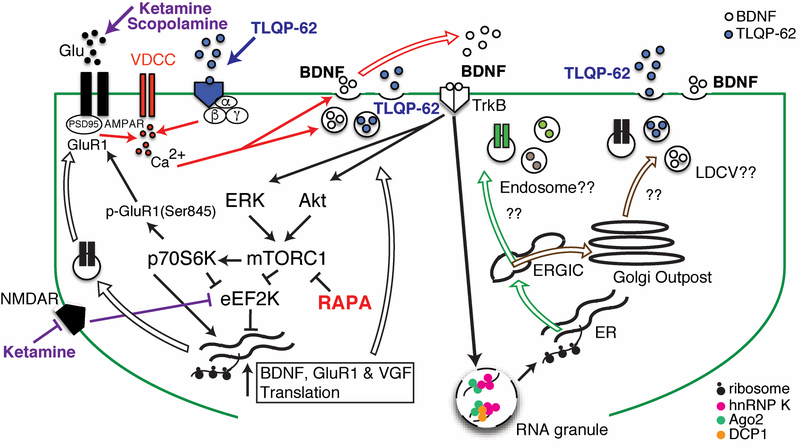

Figure 1. A VGF/BDNF/TrkB autoregulatory feedback loop stimulates synaptic plasticity changes in response to rapid-acting antidepressant treatment.

This diagram summarizes the dendritic signaling pathways (left side) and subcellular compartments (right side) that have been suggested to contribute to rapid antidepressant responses. Ketamine and scopolamine by stimulating a surge of glutamate release, GLYX-13 via NMDA-R modulation, and TLQP-62 via a yet to be identified receptor, trigger BDNF release, increase BDNF/TrkB signaling, regulate dissociation of RNA binding protein hnRNP K from specific mRNAs, and desuppress translation via mTOR and/or eEF2 pathways. Thus, rapid local synthesis and insertion of GluR1, and rapid local synthesis and secretion of VGF (TLQP-62) and BDNF, are increased, stimulating synaptic plasticity. Identified subcellular compartments in dendrites through which receptors for insertion and proteins for secretion are trafficked include the endoplasmic reticulum Golgi intermediate compartment (ERGIC). Vesicles budding from ERGIC that incorporate receptors with immature patterns of core glycosylation have been identified as endosomes. Large dense core secretory vesicles of the regulated secretory pathway, which could support protein processing (e.g. proBDNF to BDNF) remain to be identified. Abbreviations: LDCV, large dense core vesicle; Rapa, rapamycin; VDCC, voltage-dependent calcium channel.

Are Rapid, Local Protein Synthesis and Secretion Critically Required for Antidepressant Efficacy?

As described above, pathways that regulate rapid, local protein synthesis, particularly those controlled by the mTOR pathway and eEF2K that control translational efficiency, have been implicated in the efficacy of rapid-acting antidepressants. However simply increasing local synthesis of critical molecules at the synapse, including for example the neurotrophin BDNF and the AMPA receptor GluA1 subunit, is likely to be insufficient, as regulated secretion, protein sorting and processing, and/or posttranslational modification, are also required for secretory and membrane proteins to be fully active and properly localized. Are structural components that could be required for local LDCV biogenesis also synthesized at the synapse? Dendritic RNAseq analysis of hippocampal neuropil with subsequent bioinformatic filtering has identified a number of mRNAs that encode granin proteins (e.g. Vgf, Scg2, Scg3, Scg5, ChgB) (Cajigas et al. 2012), which are known to contribute to LDCV assembly, cargo sorting, and/or function (Bartolomucci et al. 2011). A recent study further shows that BDNF/TrkB signaling regulates the dissociation of RNA binding protein hnRNP K from specific mRNAs in hippocampal dendrites, including glutamate receptor mRNAs (e.g. GluA1 GluA2, and GluN1; Grik1,2,4,5; Gria1,2,3,4; Grin3a; Grm1,2,4,6; Grid1,2), several mRNAs encoding proteins that function in the secretory pathway (e.g. Vgf, Scg2, Scg3, and Chga), and Bdnf, Ntrk2 (TrkB), and Ntrk3 mRNAs (Leal et al. 2017). In addition, BDNF/TrkB signaling has been reported to induce the dissembling of the RNA granular structure found in/under dendritic spines, a subcellular structure that is enriched for translational silencing/repressing factors, including DCP1, Ago2 and other P-body components (Cougot et al. 2008; Zeitelhofer et al. 2008). Loss of P-body-like granular RNA structure may be accompanied by trapped mRNA release as shown in previous studies in neurons and other cell types, allowing for local activation of mRNA translation (Buchan 2014).

Growing evidence supports the existence of polyribosomes in dendritic spines with dynamic changes during associative fear learning (Jasinska et al. 2013; Ostroff et al. 2017). Rough endoplasmic reticulum (RER) and trans-Golgi-like compartments have also been identified in dendrites (Pierce et al. 2001), providing evidence for a satellite secretory pathway in spines. However, in general, mini-Golgi stacks or Golgi ‘outposts’ (GO) can be identified in only 20% of mature hippocampal neurons, tending to be more common in developing neurons and those that overexpress membrane proteins, while endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and ER-Golgi intermediate compartment (ERGIC) are found in all dendrites (Hanus and Ehlers 2016). Locally assembled immature or mature secretory vesicles have not been shown to bud from GOs, although Golgi-independent secretion of GluA1 from dendrites can occur via non-canonical trafficking through recycling endosomes (Bowen et al. 2017). In addition, immature, core-glycosylated GluA2-containing glutamate receptors have been identified on neuronal membranes (Hanus et al. 2016), suggesting that membrane receptors and/or secretory proteins, some locally synthesized, could be incompletely modified post-translationally and/or processed, but could still be inserted or released, and thus could have different functional properties and turnover rates compared to their mature forms.

In any case, despite incompletely understood pathways of dendritic membrane protein insertion and secretory protein processing and release, use of mTOR-inhibitors (Li et al. 2010) or ablation of eukaryotic elongation factor 2 kinase (eEF2K) in knockout mice (Nosyreva et al. 2013) suggests that local translation is likely required for antidepressant efficacy. Ketamine has therefore been hypothesized to function by at least two independent, complementary mechanisms (Zanos and Gould 2018) including: (1) via NMDA-R blockade that triggers a burst of glutamate release, AMPA-R activation, BDNF release and TrkB activation, and an mTOR-mediated increase in local protein synthesis (Abdallah et al. 2015; Li et al. 2010), or (2) via suppression of spontaneous NMDA-R-mediated neurotransmission, which potentiates synaptic responses in hippocampal CA1, inhibits eEF2K activity and desuppresses BDNF translation (Autry et al. 2011; Bjorkholm and Monteggia 2016; Miller et al. 2014; Nosyreva et al. 2013).

Function of the VGF/BDNF/TrkB Autoregulatory Feedback Loop in Plasticity Associated with Depression-like Behavior and Memory.

Localized changes in synaptic plasticity that increase the activity of specific synapses and neural circuits occur in response to administration of rapid-acting antidepressants, including ketamine (Lepack et al. 2016; Lepack et al. 2014; Lepack et al. 2015), GLYX-13 (Kato et al. 2017; Liu et al. 2017), scopolamine (Ghosal et al. 2018), and the VGF peptide TLQP-62 (Jiang et al. 2017; Li et al. 2017; Lin et al. 2014). It has been proposed that these changes are regulated by local translation and activity-dependent release of BDNF (Leal et al. 2013; Santos et al. 2010; Waterhouse and Xu 2009), and by VGF and VGF-derived C-terminal neuropeptides (Jiang et al. 2017) (Figure 1). These recent studies suggest a model whereby paracrine and/or autocrine BDNF secretion, triggered by neuronal activity, including by a proposed glutamate surge in response to NMDA-R or M1-acetylcholine-R antagonism, increases BDNF/TrkB signaling in a self-reinforcing autoregulatory loop that could be required for the sustained efficacy of rapid-acting antidepressants. In addition to activity-dependent BDNF release, increased local translation of BDNF and possibly VGF, via increased mTOR activity and/or decreased eEF2K activity that leads to rapid desuppression of translation, would result in further BDNF, VGF and TLQP-62 secretion. BDNF via TrkB activation could then increase mTOR pathway activity, decrease eEF2K activity, resulting in increased AMPA receptor insertion (containing GluA1 and GluA2 subunits), and plasticity-related changes that lead to prolonged antidepressant effects, which can last for days or weeks.

Acknowledgements:

This mini-review summarizes, in part, findings presented at the 13th International Symposium on VIP, PACAP and Related Peptides, held Dec. 3–7, 2017, in Hong Kong and its satellite meeting, in Macau, China. Research in the authors’ laboratories is supported by grants from the NIH (SRS), Cure Alzheimer’s Fund (SRS), BrightFocus Foundation (SRS), and Sun Yat-Sen Memorial Hospital, Sun Yat-Sen University (WJL).

References

- Abdallah CG, Sanacora G, Duman RS, Krystal JH (2015) Ketamine and rapid-acting antidepressants: a window into a new neurobiology for mood disorder therapeutics Annu Rev Med 66:509–523 10.1146/annurev-med-053013-062946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alder J, Thakker-Varia S, Bangasser DA, Kuroiwa M, Plummer MR, Shors TJ, Black IB (2003) Brain-derived neurotrophic factor-induced gene expression reveals novel actions of VGF in hippocampal synaptic plasticity J Neurosci 23:10800–10808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An JJ et al. (2008) Distinct role of long 3’ UTR BDNF mRNA in spine morphology and synaptic plasticity in hippocampal neurons Cell 134:175–187 10.1016/j.cell.2008.05.045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Autry AE et al. (2011) NMDA receptor blockade at rest triggers rapid behavioural antidepressant responses Nature 475:91–95 10.1038/nature10130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartolomucci A, Possenti R, Mahata SK, Fischer-Colbrie R, Loh YP, Salton SR (2011) The extended granin family: structure, function, and biomedical implications Endocr Rev 32:755–797 10.1210/er.2010-0027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjorkholm C, Monteggia LM (2016) BDNF - a key transducer of antidepressant effects Neuropharmacology 102:72–79 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2015.10.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonni A, Ginty DD, Dudek H, Greenberg ME (1995) Serine 133-phosphorylated CREB induces transcription via a cooperative mechanism that may confer specificity to neurotrophin signals Mol Cell Neurosci 6:168–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen AB, Bourke AM, Hiester BG, Hanus C, Kennedy MJ (2017) Golgi-independent secretory trafficking through recycling endosomes in neuronal dendrites and spines Elife 6 10.7554/eLife.27362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bozdagi O et al. (2008) The neurotrophin-inducible gene Vgf regulates hippocampal function and behavior through a brain-derived neurotrophic factor-dependent mechanism J Neurosci 28:9857–9869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchan JR (2014) mRNP granules. Assembly, function, and connections with disease RNA Biol 11:1019–1030 10.4161/15476286.2014.972208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cajigas IJ, Tushev G, Will TJ, tom Dieck S, Fuerst N, Schuman EM (2012) The local transcriptome in the synaptic neuropil revealed by deep sequencing and high-resolution imaging Neuron 74:453–466 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.02.036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen ZY et al. (2005) Sortilin controls intracellular sorting of brain-derived neurotrophic factor to the regulated secretory pathway J Neurosci 25:6156–6166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen ZY et al. (2006) Genetic variant BDNF (Val66Met) polymorphism alters anxiety-related behavior Science 314:140–143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen ZY, Patel PD, Sant G, Meng CX, Teng KK, Hempstead BL, Lee FS (2004) Variant brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) (Met66) alters the intracellular trafficking and activity-dependent secretion of wild-type BDNF in neurosecretory cells and cortical neurons J Neurosci 24:4401–4411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cougot N, Bhattacharyya SN, Tapia-Arancibia L, Bordonne R, Filipowicz W, Bertrand E, Rage F (2008) Dendrites of mammalian neurons contain specialized P-body-like structures that respond to neuronal activation J Neurosci 28:13793–13804 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4155-08.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duman RS, Monteggia LM (2006) A neurotrophic model for stress-related mood disorders Biol Psychiatry 59:1116–1127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egan MF et al. (2003) The BDNF val66met polymorphism affects activity-dependent secretion of BDNF and human memory and hippocampal function Cell 112:257–269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fargali S et al. (2014) The granin VGF promotes genesis of secretory vesicles, and regulates circulating catecholamine levels and blood pressure FASEB J 28:2120–2133 10.1096/fj.13-239509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosal S, Bang E, Yue W, Hare BD, Lepack AE, Girgenti MJ, Duman RS (2018) Activity-Dependent Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor Release Is Required for the Rapid Antidepressant Actions of Scopolamine Biol Psychiatry 83:29–37 10.1016/j.biopsych.2017.06.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahm S et al. (1999) Targeted deletion of the Vgf gene indicates that the encoded secretory peptide precursor plays a novel role in the regulation of energy balance Neuron 23:537–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanus C, Ehlers MD (2016) Specialization of biosynthetic membrane trafficking for neuronal form and function Curr Opin Neurobiol 39:8–16 10.1016/j.conb.2016.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanus C et al. (2016) Unconventional secretory processing diversifies neuronal ion channel properties Elife 5 10.7554/eLife.20609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunsberger JG, Newton SS, Bennett AH, Duman CH, Russell DS, Salton SR, Duman RS (2007) Antidepressant actions of the exercise-regulated gene VGF Nat Med 13:1476–1482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jasinska M, Siucinska E, Jasek E, Litwin JA, Pyza E, Kossut M (2013) Fear learning increases the number of polyribosomes associated with excitatory and inhibitory synapses in the barrel cortex PLoS One 8:e54301 10.1371/journal.pone.0054301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang C et al. (2017) VGF function in depression and antidepressant efficacy Mol Psychiatry in press [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang C, Salton SR (2013) The Role of Neurotrophins in Major Depressive Disorder Transl Neurosci 4:46–58 10.2478/s13380-013-0103-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karege F, Vaudan G, Schwald M, Perroud N, La Harpe R (2005) Neurotrophin levels in postmortem brains of suicide victims and the effects of antemortem diagnosis and psychotropic drugs Brain Res Mol Brain Res 136:29–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato T, Fogaca MV, Deyama S, Li XY, Fukumoto K, Duman RS (2017) BDNF release and signaling are required for the antidepressant actions of GLYX-13 Mol Psychiatry 10.1038/mp.2017.220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan V, Nestler EJ (2008) The molecular neurobiology of depression Nature 455:894–902 10.1038/nature07455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau AG et al. (2010) Distinct 3’UTRs differentially regulate activity-dependent translation of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107:15945–15950 10.1073/pnas.1002929107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leal G et al. (2017) The RNA-Binding Protein hnRNP K Mediates the Effect of BDNF on Dendritic mRNA Metabolism and Regulates Synaptic NMDA Receptors in Hippocampal Neurons eNeuro 4 10.1523/ENEURO.0268-17.2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leal G, Comprido D, Duarte CB (2013) BDNF-induced local protein synthesis and synaptic plasticity Neuropharmacology 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lepack AE, Bang E, Lee B, Dwyer JM, Duman RS (2016) Fast-acting antidepressants rapidly stimulate ERK signaling and BDNF release in primary neuronal cultures Neuropharmacology 111:242–252 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2016.09.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lepack AE, Fuchikami M, Dwyer JM, Banasr M, Duman RS (2014) BDNF release is required for the behavioral actions of ketamine Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 18 10.1093/ijnp/pyu033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lepack AE, Fuchikami M, Dwyer JM, Banasr M, Duman RS (2015) BDNF release is required for the behavioral actions of ketamine Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 18 10.1093/ijnp/pyu033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levi A, Eldridge JD, Paterson BM (1985) Molecular cloning of a gene sequence regulated by nerve growth factor Science 229:393–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levi A, Ferri GL, Watson E, Possenti R, Salton SR (2004) Processing, distribution and function of VGF, a neuronal and endocrine peptide precursor Cell Mol Neurobiol 24:517–533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C et al. (2017) Neuropeptide VGF C-Terminal Peptide TLQP-62 Alleviates Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Memory Deficits and Anxiety-like and Depression-like Behaviors in Mice: The Role of BDNF/TrkB Signaling ACS Chem Neurosci 8:2005–2018 10.1021/acschemneuro.7b00154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li N et al. (2010) mTOR-dependent synapse formation underlies the rapid antidepressant effects of NMDA antagonists Science 329:959–964 10.1126/science.1190287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao GY, An JJ, Gharami K, Waterhouse EG, Vanevski F, Jones KR, Xu B (2012) Dendritically targeted Bdnf mRNA is essential for energy balance and response to leptin Nat Med 18:564–571 10.1038/nm.2687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao GY et al. (2015) Brain-derived neurotrophic factor is required for axonal growth of selective groups of neurons in the arcuate nucleus Mol Metab 4:471–482 10.1016/j.molmet.2015.03.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin P et al. (2014) The VGF-derived peptide TLQP62 produces antidepressant-like effects in mice via the BDNF/TrkB/CREB signaling pathway Pharmacol Biochem Behav 120:140–148 10.1016/j.pbb.2014.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin WJ, Jiang C, Sadahiro M, Bozdagi O, Vulchanova L, Alberini CM, Salton SR (2015) VGF and its C-terminal peptide TLQP-62 regulate memory formation in hippocampus via a BDNF-dependent mechanism J Neurosci 35:10343–10356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu RJ et al. (2017) GLYX-13 Produces Rapid Antidepressant Responses with Key Synaptic and Behavioral Effects Distinct from Ketamine Neuropsychopharmacology 42:1231–1242 10.1038/npp.2016.202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu RJ, Lee FS, Li XY, Bambico F, Duman RS, Aghajanian GK (2012) Brain-derived neurotrophic factor Val66Met allele impairs basal and ketamine-stimulated synaptogenesis in prefrontal cortex Biol Psychiatry 71:996–1005 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.09.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller OH, Yang L, Wang CC, Hargroder EA, Zhang Y, Delpire E, Hall BJ (2014) GluN2B-containing NMDA receptors regulate depression-like behavior and are critical for the rapid antidepressant actions of ketamine Elife 3:e03581 10.7554/eLife.03581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nosyreva E, Szabla K, Autry AE, Ryazanov AG, Monteggia LM, Kavalali ET (2013) Acute suppression of spontaneous neurotransmission drives synaptic potentiation J Neurosci 33:6990–7002 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4998-12.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostroff LE, Botsford B, Gindina S, Cowansage KK, LeDoux JE, Klann E, Hoeffer C (2017) Accumulation of Polyribosomes in Dendritic Spine Heads, But Not Bases and Necks, during Memory Consolidation Depends on Cap-Dependent Translation Initiation J Neurosci 37:1862–1872 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3301-16.2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park H, Poo MM (2013) Neurotrophin regulation of neural circuit development and function Nat Rev Neurosci 14:7–23 10.1038/nrn3379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkhurst CN et al. (2013) Microglia promote learning-dependent synapse formation through brain-derived neurotrophic factor Cell 155:1596–1609 10.1016/j.cell.2013.11.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce JP, Mayer T, McCarthy JB (2001) Evidence for a satellite secretory pathway in neuronal dendritic spines Curr Biol 11:351–355 doi:S0960-9822(01)00077-X [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salton SR, Ferri GL, Hahm S, Snyder SE, Wilson AJ, Possenti R, Levi A (2000) VGF: a novel role for this neuronal and neuroendocrine polypeptide in the regulation of energy balance Front Neuroendocrinol 21:199–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salton SR, Fischberg DJ, Dong KW (1991) Structure of the gene encoding VGF, a nervous system-specific mRNA that is rapidly and selectively induced by nerve growth factor in PC12 cells Mol Cell Biol 11:2335–2349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos AR, Comprido D, Duarte CB (2010) Regulation of local translation at the synapse by BDNF Prog Neurobiol 92:505–516 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2010.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu E et al. (2003) Alterations of serum levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) in depressed patients with or without antidepressants Biol Psychiatry 54:70–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirayama Y, Chen AC, Nakagawa S, Russell DS, Duman RS (2002) Brain-derived neurotrophic factor produces antidepressant effects in behavioral models of depression J Neurosci 22:3251–3261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siuciak JA, Lewis DR, Wiegand SJ, Lindsay RM (1997) Antidepressant-like effect of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) Pharmacol Biochem Behav 56:131–137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens SB, Edwards RJ, Sadahiro M, Lin WJ, Jiang C, Salton SR, Newgard CB (2017) The Prohormone VGF Regulates beta Cell Function via Insulin Secretory Granule Biogenesis Cell Rep 20:2480–2489 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.08.050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss J et al. (2005) Brain-derived neurotrophic factor variants are associated with childhood-onset mood disorder: confirmation in a Hungarian sample Mol Psychiatry 10:861–867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss J et al. (2004) Association study of brain-derived neurotrophic factor in adults with a history of childhood onset mood disorder Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet 131B:16–19 10.1002/ajmg.b.30041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thakker-Varia S et al. (2014) VGF (TLQP-62)-induced neurogenesis targets early phase neural progenitor cells in the adult hippocampus and requires glutamate and BDNF signaling Stem Cell Res 12:762–777 10.1016/j.scr.2014.03.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thakker-Varia S et al. (2007) The neuropeptide VGF produces antidepressant-like behavioral effects and enhances proliferation in the hippocampus J Neurosci 27:12156–12167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voleti B et al. (2013) Scopolamine rapidly increases mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 signaling, synaptogenesis, and antidepressant behavioral responses Biol Psychiatry 74:742–749 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.04.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waterhouse EG et al. (2012) BDNF promotes differentiation and maturation of adult-born neurons through GABAergic transmission J Neurosci 32:14318–14330 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0709-12.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waterhouse EG, Xu B (2009) New insights into the role of brain-derived neurotrophic factor in synaptic plasticity Mol Cell Neurosci 42:81–89 10.1016/j.mcn.2009.06.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanos P, Gould TD (2018) Mechanisms of ketamine action as an antidepressant Mol Psychiatry 10.1038/mp.2017.255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeitelhofer M et al. (2008) Dynamic interaction between P-bodies and transport ribonucleoprotein particles in dendrites of mature hippocampal neurons J Neurosci 28:7555–7562 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0104-08.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]