Abstract

To address controversy surrounding the most appropriate comparison group for mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI) research, mTBI patients 12–30 years of age were compared with an extracranial orthopedic injury (OI) patient group and an uninjured, typically developing (TD) participant group with comparable demographic backgrounds. Injured participants underwent subacute (within 96 h) and late (3 months) diffusion tensor imaging (DTI); TD controls underwent DTI once. Group differences in fractional anisotropy (FA) and mean diffusivity (MD) of commonly studied white matter tracts were assessed. For FA, subacute group differences occurred in the bilateral inferior frontal occipital fasciculus (IFOF) and right inferior longitudinal fasciculus (ILF), and for MD, differences were found in the total corpus callosum, right uncinate fasciculus, IFOF, ILF, and bilateral cingulum bundle (CB). In these analyses, differences (lower FA and higher MD) were generally observed between the mTBI and TD groups but not between the mTBI and OI groups. After a 3 month interval, groups significantly differed in left IFOF FA and in right IFOF and CB MD; the TD group had significantly higher FA and lower MD than both injury groups, which did not differ. There was one exception to this pattern, in which the OI group demonstrated significantly lower FA in the left ILF than the TD group, although neither group differed from the mTBI group. The mTBI and OI groups had generally similar longitudinal results. Findings suggest that different conclusions about group-level DTI analyses could be drawn, depending on the selected comparison group, highlighting the need for additional research in this area. Where possible, mTBI studies may benefit from the inclusion of both OI and TD controls.

Keywords: DTI, MRI, mTBI, OI

Introduction

Mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI) has an estimated incidence ranging from 1,700,000 to 3,000,000 in the United States, and accounts for >1% of all emergency department (ED) visits in the United States.1,2 Accurate diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers would facilitate clinical management and triage of patients at risk for persistent symptoms and disability. However, the lack of validated imaging biomarkers to diagnose mTBI and predict outcome represents a significant barrier to progress. Recent imaging studies have identified MRI-detectable hemorrhagic axonal injury,3 contusion, and altered structural organization of white matter (WM) on diffusion tensor imaging (DTI),4,5 which is a promising tool for diagnosis and prognosis. However, some advanced quantitative imaging techniques such as DTI lack the normative data necessary for both useful group comparison and more precision-based analysis of individuals. Further, despite general consensus around the importance of group comparability of demographic variables, including age, sex, education, and socioeconomic status (SES), in brain injury research,6–8 and evidence that these variables may be associated with risk for sustaining brain injury7,9 and traumatic injury in general,10,11 debate continues surrounding which comparison group is most appropriate for imaging studies in mTBI.

Comparison groups for mTBI imaging research

The most frequently reported group of comparison participants utilized in TBI literature are uninjured, healthy community residents with demographic features similar to those of the TBI sample.12 This group provides a good comparison against participants with TBI in the context of typical development (TD).13–15 However, some have argued that this comparison group does not account for TBI-related risk factors such as predisposing neurobehavioral characteristics11 or nonspecific effects of traumatic injury such as post-traumatic stress.16,17 For example, youth who sustain mTBI are more likely than TD youth to have premorbid behavioral difficulties such as attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and associated impulsivity.18 Additionally, factors that may influence cognitive and functional assessment in a subacute assessment interval, including stress, pain, and medication effects, are also not well accounted for in mTBI-related studies that use a TD comparison group. Finally, patients sustaining an mTBI may have a history of concussion and/or repetitive subconcussive head impacts associated with their activities. For example, an mTBI increases the risk of a repeat mTBI.19,20 These limitations have led many investigators to consider recruiting a group of participants with traumatic injury not involving the head as an alternate comparison.

Proponents of recruiting patients with orthopedic injury (OI) or other extracranial traumatic injury as a comparison group have justified this approach on the basis of several arguments. Some have suggested that using these populations permits control over nonspecific effects of traumatic injury, including post-traumatic stress, medical treatment, medication effects, and pain. There is also some indication that an OI comparison group can potentially control for assumed premorbid risk factors, including neurobehavioral characterisics.21–25 Specifically, developmental disorders such as ADHD can persist into adulthood, increase risk for traumatic injury, including TBI and OI, and are associated with aberrant structural connectivity of WM tracts measured by DTI.26–30 Moreover, traumatic extracranial injury can result in acute stress symptoms that are similar to those reported after TBI,17 and is also associated with outcomes that are more similar to those with TBI relative to TD children.31 Acute stress symptoms can be affected by the severity of injury, associated pain, witnessing injuries of others, and associated disability.17 OI may also result in medical procedures and interventions, including a prolonged initial hospitalization stay, and subsequent deleterious effects on social and academic functioning as a result of prolonged absences from school and work that can be comparable to that experienced by patients with TBI.32

Despite similarities in premorbid characteristics and exposure to traumatic stress among patients with TBI and OI, there are acknowledged limitations of using patients with OI as a comparison group in TBI studies. Premorbid social and behavioral difficulties among patients with TBI and OI may not be equitable.33 The extent to which children with TBI experience trauma may differ from what is experienced by children with OI.16 Additionally, the literature demonstrates an incomplete understanding of functional outcomes that are influenced by analgesic medications that are frequently prescribed for pain in patients with more severe extracranial injury.34 Consequently, some investigators have attempted to mitigate pain and analgesic medication effects through rigorus exclusion of patients with greater than mild extracranial injury according to the Abbreviated Injury Scale (AIS).35,36 Less understood is the possibility of occult brain injury in OI patients, which could obscure differences between groups in outcome measures and lead to an underestimation of the extent of injury to brain structure as well as neuropsychological impairment in patients with TBI, especially mTBI. Physiological mechanisms such as subsequent systemic inflammatory response might also result in brain structure and function changes in patients with OI or other extracranial injury.37 Lastly, differentiating effects of mTBI from OI on brain structure has been complicated by the relative dearth of mTBI studies that have included advanced imaging and more than one comparison group.

Current study aims

To better understand the impact of DTI-detectable group differences attributable to mTBI per se in the subacute (within 96 h) and late (3 months) post-injury intervals, we compared a group of adolescents and young adults who had sustained mTBI with both a comparison group of participants with OI (at the same intervals) and a group of TD participants with comparable demographic history (e.g., age, sex, education, and SES). The inclusion of the uninjured, TD group provided a developmental frame of reference for elucidating any post-injury differences in neural structure as the result of traumatic injury. Specifically, the current prospective, longitudinal study compared fractional anisotropy (FA) and mean diffusivity (MD) of commonly studied WM tracts across the groups. Reduced microstructural integrity (i.e., reduced FA and increased MD) was expected to occur in specified WM tracts in the mTBI group relative to the OI and TD groups, and also in the OI group when compared with the TD group.

Methods

Participants

Adolescents and young adults (n = 180) between the ages of 12 and 30 years (mean = 20.29, SD = 5.39) were recruited as part of a larger study.36,38,39 Patients who had sustained either an mTBI (n = 83) or OI (n = 61) were recruited from a consecutive series of admissions to EDs of three level 1 trauma centers in Houston, Texas—Texas Children's Hospital, Memorial-Hermann Hospital, and Ben Taub General Hospital—by study personnel according to a rotating schedule. The TD group (n = 36) was recruited from the community by advertising. To be included, participants had to be right handed as assessed by the Edinburgh Handedness Inventory40 to control for hemispheric asymmetry. Overall study exclusionary criteria for participants in all groups included (1) lack of fluency in English or Spanish, (2) pre-existing neurological disorder or severe psychiatric disorder (e.g., bipolar disorder, schizophrenia), (3) blood alcohol level >200 mg/dL at initial evaluation in the ED (when measured), or (4) previous hospitalization for brain injury. The neurobehavioral outcome data for the three groups are reported elsewhere.38

Patients in the mTBI and OI groups were generally screened and enrolled in the ED. However, to accommodate the schedules of the patients who were discharged from the ED, initial subacute assessments for most patients occurred within a target of 96 h post-injury. In rare circumstances, the post-injury interval exceeded this window, with the longest interval being 130 h in the mTBI group and 132 h in the OI group.

All study procedures were conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration, and approved by the institutional review boards of Baylor College of Medicine, Texas Children's Hospital, Memorial-Hermann Hospital, and Ben Taub General Hospital in Houston, Texas. Informed consent and assent (as appropriate) were obtained for each participant from the parent or other legally authorized representative (in the case of a minor) and/or from the participant.

mTBI group

Patients were included in the mTBI group if they had incurred an injury to the head from blunt trauma or acceleration/deceleration forces that resulted in one or more of the following: (1) observed or self-reported confusion, disorientation, or otherwise impaired consciousness; (2) loss of consciousness lasting <30 min; (3) post-concussion symptoms;41(4) Glasgow Coma Scale42,43 score of 13–15 on examination in one of the three EDs and without delayed neurological deterioration; and (5) a period of post-traumatic amnesia (PTA) <24 h as assessed by the Galveston Orientation and Amnesia Test (GOAT).44–46 Other eligibility criteria for the mTBI group were a normal (negative) CT scan of the head within 24 h after injury, and mild or no concomitant extracranial injury47 (i.e., Abbreviated Injury Score [AIS] score ≤2).48

OI group

Eligibility criteria for the OI group also included a mild injury (AIS ≤2) without external evidence or history of head trauma, or post-concussion symptoms.

All AIS ratings were made by AIS-certified research nurses based on detailed medical record review; head CT scans were reviewed by a board-certified neuroradiologist.

TD group

Individuals comprising the uninjured, TD group were recruited through community bulletins, advertisements, and word of mouth. Recruitment efforts were made to ensure that the TD group had distributions of age, sex, level of education, and SES level that were comparable with those of the traumatic injury groups.

MRI common data elements for imaging

Although presence of an intracranial abnormality on clinical CT performed in the ED was an exclusion criterion, all MRI data were also reviewed by a single board-certified neuroradiologist (J.V.H.) for incidental findings and trauma-related abnormalities using the standardized Intra-agency Imaging Common Data Elements for Traumatic Brain Injury.49 All tiers of data collection were used, including presence or absence of each feature as well as anatomic location, and lesion or abnormality volume estimates, where applicable. In coding the MRI data, high-resolution T1-weighted, gradient recalled echo (GRE), fluid attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR), and susceptibility weighted imaging (SWI) were utilized, as appropriate.

DTI

Participants in the mTBI and OI groups underwent DTI at a subacute (within 96 h) and later (3 months) post-injury period. Of the 83 patients with mTBI, 46 (55.4%) underwent DTI on both occasions; 39 of the 61 OI patients (63.9%) underwent DTI on both occasions. Participants in the TD group had DTI on a single occasion, according to the study design, as changes were not expected to occur across the 3 month interval.

Acquisition

DTI was performed on a Philips 3T scanner (Best, The Netherlands) using transverse multi-slice spin echo, single-shot, echo planar imaging sequences (6318.0 ms repetition time [TR], 51 ms echo time [TE], 2.0 mm slices, 0 mm gap, 224 mm field of view, and 2.0 × 2.0 × 2.0 mm voxel size, sensitivity encoding [SENSE] factor of 2). Diffusion was measured along 30 directions50 (number of b-value = 2, low b-value = 0 and high b-value = 1000 sec/mm2). To improve signal-to-noise ratio, two acquisitions were acquired and averaged.

Quality assurance and stability of the MRI scanner

All DTI data were evaluated for image quality assurance (QA). To ensure consistent scanner performance throughout this longitudinal study, QA was evaluated every morning. QA involved implementing the American College of Radiology (ACR) (http://www.acr.org/quality-safety/accreditation/mri) recommended QA program that measures signal-to-noise ratio, field uniformity, gradient linearity, image distortions, and ghosting using the vendor provided phantom. Any scans that had unacceptable image quality were deleted from further analysis and are not included in the current analyses.

Quantitative DTI fiber tractography analysis

All images were analyzed by experienced image analysts who were masked to group assignment. The Philips diffusion affine registration tool was used to remove shear and eddy current distortion and head motion prior to calculating FA maps with Philips fiber tracking 4.1V3 Beta 4 software.51 Regions of interest (ROIs) were drawn manually using published protocols.52–54 Selected ROIs for analysis were the total corpus callosum (total CC), right and left uncinate fasciculi (UF), right and left cingulum bundle (CB), right and left inferior longitudinal fasciculi (ILF), and right and left inferior frontal occipital fasciculi (IFOF). The tracts were selected based on their high reproducibility using tractographic techniques as well as their structural and functional significance to outcomes in mTBI. For example, disrupted interhemispheric transfer of information (total CC), and frontal-temporal UF, frontal-parietal CB, and long distance frontal-occipital IFOF connections that are associated with alterations of attention, episodic and working memory, cognitive processing speed, and cognitive control, and are commonly altered in mTBI.5

Mean FA and MD of each of the fiber tracts were extracted and analyzed. To examine intra-rater agreement, analysis of each ROI was performed twice for each participant; intra-class correlation coefficients exceeded 0.95 for all DTI metrics. Inter-rater agreement also exceeded 0.98 for measurement of each protocol by two raters and 10 participants per group.

Statistical analysis

Demographic characteristics and variables related to mechanism of injury for the mTBI and OI groups were compared using univariate analyses of variance (ANOVAs) for continuous variables and χ2 for categorical variables. Covariates were selected in preliminary analyses using the Akaike information criterion (AIC). Age, sex, SES (as measured by the Socioeconomic Composite Index [SCI)], and all two way interactions with group (mTBI, OI, TD) were included in initial models. However, none of the two way interactions, sex, or SCI effects, reached statistical significance for any of the regions, and were trimmed from the models (p values >0.010). Therefore, only age was included as a covariate in the final models. Preliminary analyses also indicated significant hemispheric differences in both DTI metrics (i.e., FA and MD) for many of the tracts (p values <0.045). Therefore, left and right WM ROIs were analyzed separately.

Separate analyses of covariance (ANCOVAs) (with covariate age) were used to examine differences between the groups (mTBI, OI, TD) on FA and MD measures of WM ROIs at the subacute (i.e., within 96 h) as well as at the late (i.e., 3 months) post-injury assessment. These cross-sectional analyses were examined prior to the evaluation of any longitudinal effects so that the injury groups (i.e., OI and mTBI) could be compared with the TD group. Longitudinal changes in FA and MD between the mTBI and OI groups in each WM region were subsequently examined using separate 2 (occasion: subacute, late) x 2 (group: mTBI, OI) repeated measures ANCOVAs, with age as a covariate.

Power of the current sample size for detecting small between-group effects was computed using G*Power 3.1 (hpower.hhu.de accessed February 18, 2018): power (1-ß) = 0.439 (critical F-value = 2.44) for detecting a small effect size (i.e., f = 0.20) between the mTBI and OI groups (n = 144, α = 0.05, with 1 covariate); power (1-ß) = 0.554 (critical F-value = 2.83) for detecting a small effect size (i.e., f = 0.20) between all three groups (n = 180, α = 0.05, with 1 covariate).

Results

Demographic and injury characteristics

Demographic characteristics for each group are shown in Table 1. Groups were comparable in age, sex, race/ethnicity, and SES. The mTBI and OI groups underwent subacute phase neuroimaging at similar post-injury intervals (generally within 96 h). Of the 83 patients in the mTBI group, 44 (53.0%) underwent DTI on both the subacute and late (3 months post-injury) occasions; 39 of the 59 patients in the OI group (74.6%) were also imaged on both occasions. However, as anticipated, injuries sustained as a result of motor vehicle crashes occurred at a higher proportion in the mTBI group than in the OI group, consistent with our previous reports of patients recruited from the same EDs.39

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristic Data for Patients in the mTBI and OI Groups as Well as for the TD, Community Comparison Group

| mTBI (n = 83) | OI (n = 61) | TD (n = 36) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at injury (mean [SD] years) | 19.89 (5.30) | 20.31 (5.75) | - | 0.657 |

| Age at initial DTI (mean [SD] years) | 19.90 (5.30) | 20.31 (5.75) | 21.14 (4.99) | 0.513 |

| Socioeconomic status (mean [SD] z-score) | −0.11 (0.77) | −0.02 (0.80) | 0.22 (0.87) | 0.118 |

| Sex (n [% male]) | 56 (67.5) | 45 (73.8) | 21 (58.3) | 0.290 |

| Race (n [% white]) | 51 (61.4) | 36 (59.0) | 24 (66.7) | 0.825 |

| Ethnicity (n [% Hispanic]) | 31 (37.3) | 28 (45.9) | 12 (16.9) | 0.411 |

| Positive LOC (n [% positive]) | 60 (77) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | - |

| Mechanism of injury (n [% MVC]) | 39 (47.0) | 8 (13.1) | 0 (0) | <0.001 |

DTI, diffusion tensor imaging; LOC, loss of consciousness; MV, motor vehicle crash; mTBI, mild traumatic brain injury; OI, orthopedic injury; TD, typically developing.

Bold indicates significant group difference.

Summary of MRI common data elements imaging findings

Review of the common data elements (CDE) data confirmed the absence of any trauma-related pathology for all participants in the TD and OI groups, although, two participants in the OI group had mild atrophy at both baseline and follow-up imaging. For the mTBI group, none of the following trauma-related findings were observed: epidural hematoma, extra-axial hematoma, subdural hematoma, subarachnoid hemorrhage, gliosis, or edema. However, the following intracranial blood-related findings were present in a small number of individuals in the mTBI group: hemorrhagic shear injury (n = 3), contusion (n = 10), intraparenchymal hemorrhage (n = 5), and intraventricular hemorrhage (n = 1). In each of these cases, the estimated volume was <0.3 cm3. Ischemia was present in a single participant in the mTBI group. Evidence of non-intracranial injury was also evident in the mTBI group: subcutaneous hematoma (n = 4), cephalohematoma (n = 3), and laceration (n = 1). Interestingly, mild atrophy was also noted in eight of the participants in the mTBI group, which was present on both subacute and follow-up MRI.

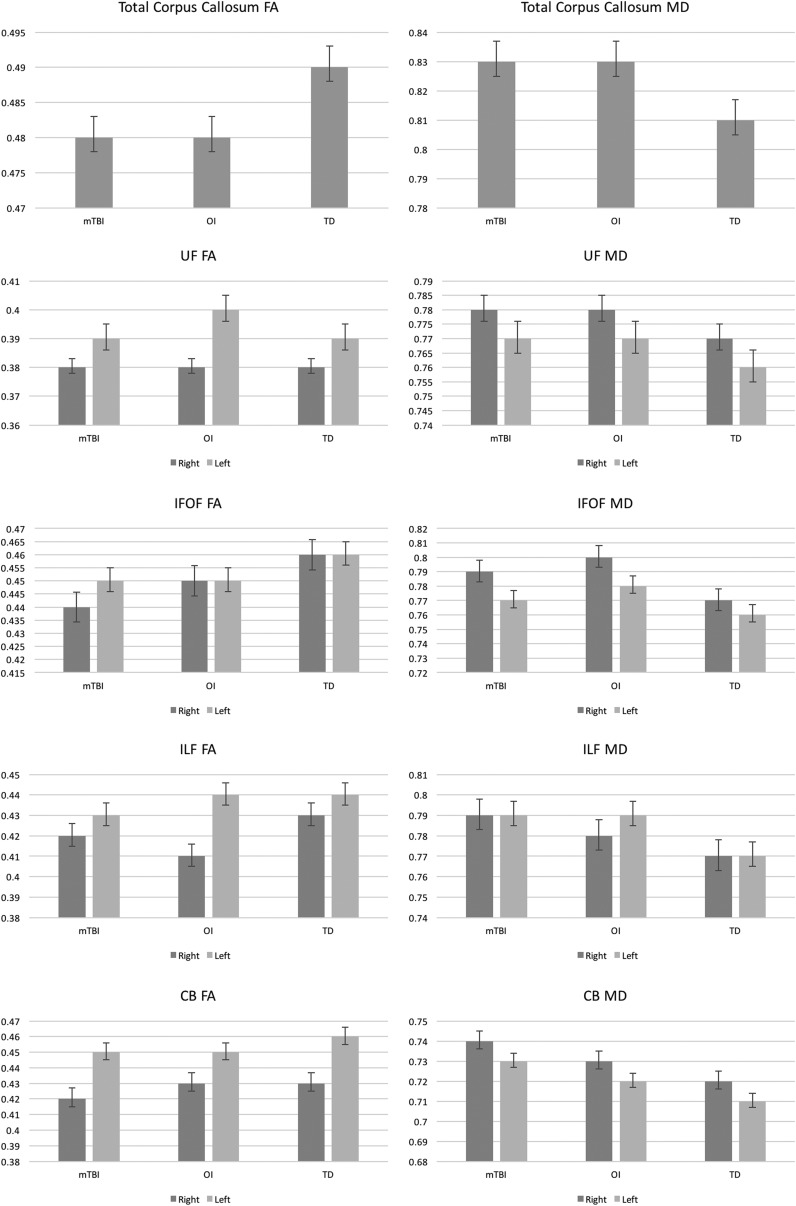

Subacute occasion: Group differences in DTI metrics

Average FA and MD values of the selected WM ROIs at the subacute (within 96 h post-injury) assessment for each group and ANCOVA statistics with covariate age are presented in Table 2, and depicted by the bar graphs in Figure 1, respectively.

Table 2.

Subacute Assessment (i.e., within 96 h Post-Injury) Descriptive Statistics and Cross-Sectional Differences between Groups, Controlling for Age, for Fractional Anisotropy (FA) and Mean Diffusivity (MD) Values of Each White Matter Region of Interest (ROI)

| Group | ANCOVA statistics | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mtbi (n = 83) | OI (n = 61) | TD (n = 36) | Main effect group | Covariate age | ||||||||

| ROI | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | F value | p value | F value | p value | Pairwise | |

| FA | ||||||||||||

| Total CC | 0.48 | 0.02 | 0.48 | 0.02 | 0.49 | 0.02 | 2.45 | 0.089 | 1.94 | 0.165 | mTBI, OI < TD | |

| UF | ||||||||||||

| R | 0.38 | 0.02 | 0.38 | 0.02 | 0.38 | 0.02 | < 1.00 | 0.604 | <1.00 | 0.864 | - | |

| L | 0.39 | 0.02 | 0.40 | 0.02 | 0.39 | 0.02 | < 1.00 | 0.597 | < 1.00 | 0.727 | - | |

| IFOF | ||||||||||||

| R | 0.44 | 0.02 | 0.45 | 0.02 | 0.46 | 0.03 | 3.53 | 0.031 | 2.07 | 0.152 | mTBI, OI < TD | |

| L | 0.45 | 0.02 | 0.45 | 0.02 | 0.46 | 0.02 | 5.97 | 0.003 | < 1.00 | 0.945 | mTBI, OI < TD | |

| ILF | ||||||||||||

| R | 0.42 | 0.03 | 0.41 | 0.02 | 0.43 | 0.02 | 3.42 | 0.035 | < 1.00 | 0.704 | mTBI = OI mTBI = TD OI < TD |

|

| L | 0.43 | 0.03 | 0.44 | 0.03 | 0.44 | 0.02 | < 1.00 | 0.493 | < 1.00 | 0.953 | - | |

| CB | ||||||||||||

| R | 0.42 | 0.03 | 0.43 | 0.04 | 0.43 | 0.03 | < 1.00 | 0.760 | 3.23 | 0.074 | - | |

| L | 0.45 | 0.03 | 0.45 | 0.3 | 0.46 | 0.02 | < 1.00 | 0.608 | 6.27 | 0.013 | - | |

| MD | ||||||||||||

| Total CC | 0.83 | 0.03 | 0.83 | 0.03 | 0.81 | 0.03 | 3.22 | 0.042 | < 1.00 | 0.820 | mTBI, OI > TD | |

| UF | ||||||||||||

| R | 0.78 | 0.03 | 0.78 | 0.02 | 0.77 | 0.02 | 3.66 | 0.028 | 4.26 | 0.040 | mTBI, OI > TD | |

| L | 0.77 | 0.03 | 0.77 | 0.03 | 0.76 | 0.03 | 1.63 | 0.199 | 2.04 | 0.155 | - | |

| IFOF | ||||||||||||

| R | 0.79 | 0.04 | 0.80 | 0.04 | 0.77 | 0.04 | 5.88 | 0.003 | 2.99 | 0.086 | mTBI, OI > TD | |

| L | 0.77 | 0.03 | 0.78 | 0.04 | 0.76 | 0.03 | 2.50 | 0.085 | 2.44 | 0.120 | mTBI = OI mTBI = TD OI > TD |

|

| ILF | ||||||||||||

| R | 0.79 | 0.05 | 0.78 | 0.03 | 0.77 | 0.02 | 3.44 | 0.034 | 4.71 | 0.031 | mTBI, OI > TD | |

| L | 0.79 | 0.05 | 0.79 | 0.04 | 0.77 | 0.04 | 2.35 | 0.099 | 1.06 | 0.304 | mTBI, OI > TD | |

| CB | ||||||||||||

| R | 0.74 | 0.03 | 0.73 | 0.02 | 0.72 | 0.02 | 6.91 | 0.001 | 27.05 | < 0.001 | mTBI, OI > TD | |

| L | 0.73 | 0.02 | 0.72 | 0.02 | 0.71 | 0.02 | 3.46 | 0.034 | 14.95 | < 0.001 | mTBI, OI > TD | |

Bolded, statistically significant; p < 0.05; mTBI, mild traumatic brain injury; OI, orthopedic injury; TD, typically developing; FA, fractional anisotropy; MD, mean diffusivity; CC, corpus callosum; UF, uncinated fasciculus; IFOF, inferior frontal occipital fasciculus; ILF, inferior longitudinal fasciculus; CB, cingulum bundle.

FIG. 1.

Bar graphs illustrating the overall pattern of group differences whereby the injury groups (i.e., mild traumatic brain injury [mTBI] and orthopedic injury [OI]) did not differ statistically from each other, but differed significantly from the typically developing (TD) group at the subacute (i.e., ≤96 h) evaluation. FA, fractional anisotropy; MD, mean diffusivity; UF, uncinate fasciculi; IFOF, inferior frontal occipital fasciculi; ILF, inferior longitudinal fasciculi; CB, cingulum bundle.

Total CC

As indicated in Table 2, for the total CC, there was a marginally significant main effect of group on FA values (p = 0.089), and a significant main effect of group on MD values (p = 0.042), controlling for the nonsignificant covariate age (p ≥ 0.165). As reflected by Figure 1, post-hoc analyses indicated that the TD group tended toward greater FA than both the mTBI (ß = -0.008, p = 0.041) and the OI (ß = -0.008, p = 0.050), groups, which did not significantly differ (p = 0.992), controlling for age. The TD group also had significantly lower MD values than the mTBI (ß = 0.015, p = 0.022) and the OI (ß = 0.016, p = 0.022), group, which did not significantly differ (p = 0.893), controlling for age.

UF

The main effect of group failed to reach statistical significance on right and left FA as well as on left MD of the UF (Table 2). However, for right UF MD, the main effect of group (p = 0.028), and the covariate age (p = 0.040), were statistically significant. Post-hoc analyses indicated that the TD group had significantly lower MD values in the right UF than the mTBI (ß = 0.013, p = 0.009), and the OI (ß = 0.011, p = 0.031), group, which did not differ statistically (p = 0.665), controlling for age (Fig. 1).

IFOF

The main effect of group was significantly related to right (p = 0.031), and left (p = 0.003), IFOF FA and right IFOF MD (p = 0.003), and marginally related to left IFOF MD (p = 0.085), controlling for the covariate age (p ≥ 0.086) (Table 2). Post-hoc analyses (Fig. 1) indicated that the TD group had significantly greater FA in the right and left IFOF than the mTBI (right: ß = −0.014, p = 0.005; left: ß = 0.011, p = 0.030) and the OI (right: ß = −0.012, p = 0.005; left: ß = 0.017, p = 0.001) group, which did not significantly differ (p = 0.095), controlling for age. The TD group had significantly lower MD in the right IFOF than the mTBI (ß = 0.023, p = 0.003) and the OI (ß = 0.026, p = 0.002) group, which did not significantly differ (p = 0.697). However, whereas the mTBI group did not significantly differ from the OI (ß = −0.005, p = 0.345) or the TD (ß = 0.010, p = 0.126) group, the TD group had significantly reduced MD compared to the OI group (ß = −0.015, p = 0.02) (Fig. 1).

ILF

Although the main effect of group failed to reach statistical significance for left ILF FA and MD, there was a significant effect of group on right ILF FA (p = 0.035) and MD (p = 0.034), controlling for age (Table 2). Post-hoc analyses (Fig. 1) indicated that the mTBI group had right ILF FA values similar to those of the OI (ß = 0.006, p = 0.196) and the TD (ß = −0.009, p = 0.105) group, but that the OI group had significantly lower right ILF FA than the TD group (ß = −0.015, p = 0.010) (Fig. 1). However, the TD group had significantly higher right ILF MD values than the mTBI (ß = −0.019, p = 0.012) and the OI (ß = −0.017, p = 0.034) group, which did not significantly differ (ß = 0.002, p = 0.712), controlling for age.

CB

Although the main effect of group failed to reach statistical significance on right (p = 0.266) or left CB FA (p = 0.608) there was a significant main effect of group on right (p = 0.001) and left (p = 0.034) CB MD values, respectively, after controlling for the covariate age (Table 2). Post-hoc analyses (Fig. 1) indicated that the TD group had significantly reduced MD in the right and left CB compared with the mTBI (right: ß = −0.017, p < 0.001; left: ß = 0.010, p = 0.011) and the OI (right: ß = −0.012, p = 0.012; left: ß = 0.009, p = 0.035) group, which did not significantly differ (p ≥ 0.207).

Late occasion: Group differences in DTI metrics

Average FA and MD values of the selected WM ROIs at the late (3 months) post-injury assessment for the groups with mTBI and OI, as well as the three-group ANCOVA statistics with covariate age are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Descriptive Statistics (for the mTBI and TD Groups) and Cross-Sectional Differences between Groups at the Late (i.e., at 3 Months Post-Injury) Assessment for Fractional Anisotropy (FA) and Mean Diffusivity (MD) Values of Each White Matter Region of Interest (ROI)

| Group | Statistics | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mtbi (n = 46) | OI (n = 39) | Main effect group | Covariate age | |||||||

| Region of interest | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | F value | p value | F value | p value | Pairwise | |

| FA | ||||||||||

| Total CC | 0.49 | 0.02 | 0.48 | 0.02 | 2.83 | 0.106 | < 1.00 | 0.925 | - | |

| UF | ||||||||||

| R | 0.38 | 0.02 | 0.38 | 0.02 | <1.00 | 0.970 | < 1.00 | 0.845 | - | |

| L | 0.40 | 0.02 | 0.40 | 0.02 | <1.00 | 0.654 | < 1.00 | 0.535 | - | |

| IFOF | ||||||||||

| R | 0.45 | 0.03 | 0.45 | 0.03 | 1.18 | 0.312 | 1.26 | 0.264 | - | |

| L | 0.46 | 0.02 | 0.45 | 0.02 | 3.39 | 0.037 | < 1.00 | 0.581 | mTBI = OI mTBI = TD OI < TD |

|

| ILF | ||||||||||

| R | 0.42 | 0.04 | 0.41 | 0.02 | 2.80 | 0.065 | < 1.00 | 0.854 | mTBI = OI mTBI = TD OI < TD |

|

| L | 0.43 | 0.03 | 0.43 | 0.02 | <1.00 | 0.555 | < 1.00 | 0.553 | - | |

| CB | ||||||||||

| R | 0.43 | 0.03 | 0.43 | 0.03 | <1.00 | 0.920 | 1.70 | 0.195 | - | |

| L | 0.46 | 0.02 | 0.45 | 0.03 | <1.00 | 0.389 | 7.70 | 0.006 | - | |

| MD | ||||||||||

| Total CC | 0.82 | 0.03 | 0.82 | 0.03 | 2.48 | 0.089 | < 1.00 | 0.518 | mTBI, OI > TD | |

| UF | ||||||||||

| R | 0.78 | 0.02 | 0.78 | 0.02 | 2.14 | 0.123 | 3.17 | 0.078 | - | |

| L | 0.77 | 0.03 | 0.76 | 0.02 | <1.00 | 0.426 | < 1.00 | 0.398 | - | |

| IFOF | ||||||||||

| R | 0.80 | 0.05 | 0.81 | 0.05 | 8.05 | 0.001 | 2.66 | 0.106 | mTBI, OI > TD | |

| L | 0.78 | 0.05 | 0.78 | 0.04 | 1.36 | 0.261 | 4.315 | 0.044 | - | |

| ILF | ||||||||||

| R | 0.79 | 0.07 | 0.78 | 0.03 | 2.23 | 0.113 | 3.83 | 0.053 | - | |

| L | 0.78 | 0.04 | 0.78 | 0.04 | <1.00 | 0.472 | < 1.00 | 0.810 | - | |

| CB | ||||||||||

| R | 0.74 | 0.03 | 0.74 | 0.03 | 7.07 | 0.001 | 22.61 | < 0.001 | mTBI, OI > TD | |

| L | 0.73 | 0.02 | 0.72 | 0.02 | 2.31 | 0.104 | 11.86 | 0.001 | - | |

Bolded, statistically significant; p < 0.05; mTBI, mild traumatic brain injury; OI, orthopedic injury; TD, typically developing; CC, corpus callosum; UF, uncinated fasciculus; IFOF, inferior frontal occipital fasciculus; ILF, inferior longitudinal fasciculus; CB, cingulum bundle.

For the late evaluation, the main effect of group failed to reach statistical significance for FA values of any of the WM ROIs, with the exception of left IFOF FA, controlling for the covariate age (Table 3). Post-hoc analyses indicated that the mTBI group was statistically similar to the OI (ß = 0.007, p = 0.179) and the TD (ß = −0.007, p = 0.171) group, whereas the OI group had significantly lower left IFOF FA than the TD group (ß = −0.014, p = 0.010) controlling for age (p = 0.581).

For the late evaluation, the main effect of group failed to reach statistical significance for MD values of any of the WM ROIs, with the exception of the marginal effect on total CC MD and the significant effect on MD values of the right IFOF and CB (Table 3). Post-hoc analyses indicated that the TD group had lower MD in total CC, right IFOF, and right CB than the mTBI (total CC: ß = −0.013, p = 0.053; right IFOF: ß = −0.033, p = 0.001; right CB: ß = −0.017, p = 0.001) and the OI (total CC: ß = −0.014, p = 0.053; right IFOF: ß = −0.038, p < 0.001; right CB: ß = −0.017, p = 0.002) group, respectively, which did not significantly differ (p ≥ 0.633), controlling for age.

Longitudinal differences between the groups with mTBI and OI

To determine significant changes in DTI metrics between the subacute and late assessments of the groups with mTBI and OI, separate two (occasion: subacute, late) x two (group: OI, mTBI) repeated measures ANCOVAs with covariate age were examined for each WM ROI. None of the within-subjects effects (occasion, occasion x age interaction, occasion x group interaction), the between-subjects effect of group, or the covariate age reached statistical significance (p values ≥0.100) on FA or MD values of any of the WM ROIs, controlling for covariate age, with the exception of right CB FA. There was a significant occasion x group interaction effect, F(1, 80) = 4.11, p = 0.046, on right CB FA values. However, the within-subject effects of occasion (F[1, 80] < 1.00, p = 0.962) and the occasion x age interaction (F[1, 80] < 1.00, p = 0.883), and the between-subjects effect of group (F[1, 80] <1.00, p = 0.990), and covariate age (F[1, 80] = 1.24, p = 0.268) failed to reach statistical significance. Follow-up analyses indicated that FA values of the right CB increased across occasions in the group with mTBI (subacute: mean = 0.425, SE = 0.005; follow-up: mean = 0.434, SE = 0.004) with the opposite pattern (i.e., of reduced values) observed in the OI group (subacute: mean = 0.432, SE = 0.005; follow-up: mean = 0.428, SE = 0.005), although groups did not significantly differ in right CB FA at either occasion (subacute: ß = −0.002, p = 0.660; follow-up: ß = 0.003, p = 0.702).

Discussion

The preponderance of studies on the outcome of mTBI have recruited healthy community residents as a comparison group. However, this approach introduces confounds of pre-injury risk factors including risk-taking behavior, substance abuse, ADHD, and other features that predispose to traumatic injury. Proponents of recruiting OI patients for comparison with mTBI samples have pointed to similarities in these predisposing risk factors in addition to the need to control for factors associated with post-traumatic stress, pain, medication, and other treatment factors.21–25 However, limitations of using OI patients for comparison with mTBI patients include the possibility of occult brain injury and the potential impact of post-injury systemic (e.g., inflammatory) responses. There is also the possibility that the cumulative effects of exposure to prior mTBI and/or repetitive, subconcussive head impacts can affect imaging findings in either mTBI or OI groups.20,55,56 To test the appropriateness of including OI comparisons in neuroimaging studies of mTBI, we evaluated WM integrity within 96 h (subacute) and 3 months (late) post-injury and in a typical, community comparison group. Taken together, subacute results supported a general pattern of group differences whereby FA was lower and MD was higher in both the mTBI and OI groups relative to uninjured controls in multiple WM regions, including the IFOF, ILF, CC, UF, and CB, with persistent main effects on left IFOF FA and right IFOF and CB MD, and marginal effects on the total corpus callosum at the 3 month follow-up. However, post-hoc testing of the group comparisons at the later assessment revealed significantly lower left IFOF FA in only the OI group relative to the TD group. Overall results indicated that both groups of patients with traumatic injuries, regardless of whether the injury resulted in brain injury per se, exhibited similarly altered subacute diffusion characteristics in WM regions compared with the uninjured comparison group, and that these differences generally persisted 3 months later.

The lack of observed differences in DTI metrics between the mTBI and OI groups was unexpected. Despite the presence of minor trauma-related pathology in a minority of the participants in the mTBI group, the groups did not differ in FA or MD for any of the tracts measured. In contrast, both injury groups exhibited alteration of quantitative diffusion values within WM tracts compared with the uninjured, TD adolescents and young adults who were recruited from the community. It may be that trauma-related issues obscure or confound differences that are attributable to brain injury itself. It is also possible that methods to decrease variability in measurement and increase the sensitivity of neuroimaging to change will be necessary to better discern the effects of brain injury.

Although differences in demographic and risk factors has been a potential concern in some previous studies in the literature, we note that extensive care was taken during recruitment to ensure that groups were comparable in all demographic characteristics (as detailed in the Methods), including age, sex, race/ethnicity, and SES. Additionally, our prospective study included consistent post-injury intervals for the OI and mTBI groups to address differences that have been cited in other studies. Finally, to mitigate potential confounds related to pain and medication effects, we limited recruitment of OI patients to those who had sustained a mild injury, and we used this criterion for mTBI patients who had a concomitant extracranial injury. This criterion excluded patients with more severe polytrauma, which can be complicated by hypotension and even transient alteration of consciousness.57 Therefore, it is possible that the similarity in WM integrity between the mTBI and OI groups relative to the TD control group reflects these inherent, premorbid factors as opposed to frank changes or alterations caused by injury.

The mechanisms underlying the altered DTI metrics in the mTBI and OI groups are not entirely clear. Animal models and neuropathological studies implicate traumatic axonal injury as the major mechanism of increased MD during the 1st week after mTBI.5 However, cytotoxic edema has also been suggested, especially in studies reporting elevated FA in subacute mTBI.58 It is also largely unclear how systemic responses to traumatic extracranial injury influence brain structure and function, and whether mechanisms such as inflammation may play a role in both OI and mTBI. Recent experimental studies have documented increased peripheral and central inflammatory responses and greater structural and functional deficits in animal models when there is concomitant brain and extracranial injury, even when TBI severity and force are controlled.59–61 These findings suggest that concomitant extracranial injury may contribute to additional secondary injury process in polytrauma situations.62 Limited data in patients with concomitant brain and peripheral injury also reflect an increased risk of motality and functional deficit when severe extracranial injury co-presents with mild or moderate TBI.37 However, understanding of the potential impact of more mild extracranial injury, particularly in the absence of brain injury, remains incomplete and warrants further study.

With regard to imaging in particular, longitudinal DTI data in mTBI studies have provided some support for the inference that elevated MD is related to the injury as it resolves, at least partially, by 3 months.5 However, the mechanism for elevated MD in the current sample of patients with OI is less apparent. Wilde and coworkers found no difference in DTI values at 26 h compared with 3 months after injury in their OI comparison group, which included similar injury characteristics, but was composed of a different sample, which argues against an acute injury mechanism.39 However, no uninjured group was recruited, thus precluding identification of aberrant DTI findings in the patients with OI.

The extent to which mTBI and OI groups in the current sample exhibited MD and FA anomalies between the subacute and 3 month post-injury evaluations was also generally similar. One exception included higher FA values in the cingulum at 3 months post-injury relative to the subacute assessment in the mTBI group, with the opposite pattern observed in the OI patients, although it is noteworthy that no differences between these injury groups were noted at either assessment. These findings suggest the possisbility that the neural mechanisms contributing to WM anomalies in patients with OI differ from those in patients with mTBI. Although screening for the presence of pre-injury neurological or severe psychiatric disorder was performed and was an exclusion criterion for all groups, as was prior hospitalization for TBI, we cannot exclude the possibility of more subtle developmental conditions that were undiagnosed in the OI group. Although we excluded mTBI and OI patients with a history of hospitalization for TBI, it is possible that some of the participants sustained repeated subconcussive brain injuries that did not result in hospitalization. A recent DTI study of adolescent football players reported pre-post season differences on DTI in athletes who were not concussed.56 A limitation of the present study is that we did not collect information on exposure to contact sports or other situations associated with repeated head impacts.

The parent project of this study focused on adolescents and young adults because of the dynamic prefrontal and cerebral WM maturation associated with cognitive and behavioral development in this age range.63 Moreover, adolescents and young adults also have a high incidence of mTBI, which is thought to be attributed in part to risky behavior caused by incomplete maturation of prefrontal cortex.63 Accordingly, this maturational issue provides a rationale for careful consideration of differences between comparison groups when considering designs of studies in TBI that involve imaging.

Conclusion and Future Directions

Our findings suggest that selection of a comparison group may contribute to the inconsistency of DTI-based findings previously reported in the literature; it is possible that studies utilizing a TD comparison group may have yielded different conclusions if an OI comparison group had been utilized. However, the selection of one comparison group versus another is likely to remain somewhat controversial,19 as the current results highlight that the use of each has some advanatges and limitations. It is possible that the similarity in WM integrity between the mTBI and OI groups relative to the TD control group reflects inherent, premorbid factors that are associated with increased risk for injury as opposed to frank changes or alterations caused by injury. As noted, the contribution of prior exposure to subconcussive head impacts may have been contributory to the DTI findings in both trauma groups. Further prospective research would aid in teasing apart these effects. Alternatively, current results could also suggest that the patients with OI may incur some degree of alteration of WM consistent with those observed in mTBI.

As previously proposed, OI patients may be similar to mTBI patients in premorbid characteristics, post-traumatic stress,24,25 and the influences of pain and analgesic medication, which may depress cognitive function and inflate post-concussion symptom report.36 Additionally, participation in certain activities (e.g., contact sport, risky recreational actvities) related to the cause of the index injury may elevate risk for injury in general; past or concurrent occult brain injury in OI groups could lead to an underestimation of mTBI-related changes in brain connectivity and cognitive dysfunction. Alternatively, the effects of extracranial injury (e.g., systemic inflammation, metabolic changes, fat emboli) may have systemic effects that could impact DTI-measured changes in the brain and associated cognitive outcome.36 Although some experimental models of brain injury may allow more detailed understanding of the contributions of brain injury versus extracranial injury versus the combination, this may prove more difficult in clinical situations in which the force applied to one part of the body (either the head or the body) does not occur in isolation; for example, force sufficient to break a bone, as in a fall or collision, is unlikely to avoid jostling the brain, even in the absence of a frank concussion.

The selection of an optimal control group for any cohort with mild TBI, including military TBI and sports-related concussion, in which orthopedic injury and polytrauma are also common, may largely depend on the question being addressed. However, thoughtful consideration should be given to demographic factors that may influence measures of brain structure and function, predisposing risk factors for TBI, history of subconcussive or concussive events preceding the index injury and exposure to contact or collision sports,20 and situational factors that may influence structure or function (pain, medication effects, sleep deprivation). If an OI group is to be used, thorough screening for occult brain injury may be necessary by screening for post-traumatic amnesia, alteration of consciousness, and post-concussive symptoms. An alternative to an OI comparison group may be the use of “best friend controls” as this approach may mitigate differences in demographics and risk-taking behavior to some degree.19 As proposed in our previous study,38 recruitment of two control groups—patients with orthopedic injuries and healthy uninjured individuals—has the advantages of controlling for risk factors and post-traumatic effects of injury, and also providing a comparison with TD, uninjured participants.

Acknowledgments

Support for this research was provided by the National Institutes of Health (NIH)/National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) (P01 NS056202, PI: Douglas Smith, M.D.), US Army Medical Research and Materiel Command (USAMRMC) (PT13078, PI: Geoff Manley, M.D.), and TBI Endpoints Development grant W81XWH-14-2-0176 (PI: Geoff Manley, M.D., Ph.D.). We thank the participants and their family members for their participation in this study. We also thank the anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments and suggestions in revising the manuscript.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1. Whiteneck G.G., Gerhart K.A., and Cusick C.P. (2004). Identifying environmental factors that influence the outcomes of people with traumatic brain injury. J. Head Trauma Rehabil. 19, 191–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Boake C., McCauley S.R., Levin H.S., Pedroza C., Contant C.F., Song J.X., Brown S.A., Goodman H., Brundage S.I., and Diaz-Marchan P.J. (2005). Diagnostic criteria for postconcussional syndrome after mild to moderate traumatic brain injury. J. Neuropsychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 17, 350–356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ezaki Y., Tsutsumi K., Morikawa M., and Nagata I. (2006). Role of diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging in diffuse axonal injury. Acta Radiol. 47, 733–740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bigler E.D. (2015). Neuropathology of mild traumatic brain injury: correlation to neurocognitive and neurobehavioral findings., in: Brain Neurotrauma: Molecular, Neuropsychological, and Rehabilitation Aspects. Kobeissy F.H. (ed.). CRC Press/Taylor & Francis: Boca Raton, FL: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Shenton M.E., Hamoda H.M., Schneiderman J.S., Bouix S., Pasternak O., Rathi Y., Vu M.-A., Purohit M.P., Helmer K., Koerte I., Lin A.P., Westin C.-F., Kikinis R., Kubicki M., Stern R.A., and Zafonte R. (2012). A review of magnetic resonance imaging and diffusion tensor imaging findings in mild traumatic brain injury. Brain Imaging Behav. 6, 137–192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Selassie A.W., Zaloshnja E., Langlois J.A., Miller T., Jones P., and Steiner C. (2008). Incidence of long-term disability following traumatic brain injury hospitalization, United States, 2003: J. Head Trauma Rehabil. 23, 123–131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Yates P.J. (2006). An epidemiological study of head injuries in a UK population attending an emergency department. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 77, 699–701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wintermark M., Coombs L., Druzgal T.J., Field A.S., Filippi C.G., Hicks R., Horton R., Lui Y.W., Law M., Mukherjee P., Norbash A., Riedy G., Sanelli P.C., Stone J.R., Sze G., Tilkin M., Whitlow C.T., Wilde E.A., York G., Provenzale J.M., and American College of Radiology Head Injury Institute (2015). Traumatic brain injury imaging research roadmap. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 36, E12–23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Selassie A.W., Pickelsimer E.E., Frazier L., and Ferguson P.L. (2004). The effect of insurance status, race, and gender on ED disposition of persons with traumatic brain injury. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 22, 465–473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Collins J.G. (1990). Types of injuries by selected characteristics. Vital Health Stat. 10, 1–68 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Stancin T., Taylor H.G., Thompson G.H., Wade S., Drotar D., and Yeates K.O. (1998). Acute psychosocial impact of pediatric orthopedic trauma with and without accompanying brain injuries. J. Trauma 45, 1031–1038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Catroppa C., Godfrey C., Rosenfeld J.V., Hearps S.S.J.C., and Anderson V.A. (2012). Functional recovery ten years after pediatric traumatic brain injury: outcomes and predictors. J. Neurotrauma 29, 2539–2547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bazarian J.J., McClung J., Shah M.N., Cheng Y.T., Flesher W., and Kraus J. (2005). Mild traumatic brain injury in the United States, 1998–2000. Brain Inj. 19, 85–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Langlois J.A., Rutland-Brown W., and Wald M.M. (2006). The epidemiology and impact of traumatic brain injury: a brief overview. J. Head Trauma Rehabil. 21, 375–378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rutland-Brown W., Langlois J.A., Thomas K.E., and Xi Y.L. (2006). Incidence of traumatic brain injury in the United States, 2003. J. Head Trauma Rehabil. 21, 544–548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Basson M.D., Guinn J.E., McElligott J., Vitale R., Brown W., and Fielding L.P. (1991). Behavioral disturbances in children after trauma. J. Trauma 31, 1363–1368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hajek C.A., Yeates K.O., Gerry Taylor H., Bangert B., Dietrich A., Nuss K.E., Rusin J., and Wright M. (2010). Relationships among post-concussive symptoms and symptoms of PTSD in children following mild traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj. 24, 100–109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gerring J.P., Brady K.D., Chen A., Vasa R., Grados M., Bandeen-Roche K.J., Bryan R.N., and Denckla M.B. (1998). Premorbid prevalence of ADHD and development of secondary ADHD after closed head injury. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 37, 647–654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bodien Y.G., McCrea M., Dikmen S., Temkin N., Boase K., Machamer J., Taylor S.R., Sherer M., Levin H., Kramer J.H., Corrigan J.D., McAllister T.W., Whyte J., Manley G.T., Giacino J.T., and the TRACK-TBI Investigators. (2018). Optimizing outcome assessment in multicenter TBI Trials: Perspectives from TRACK-TBI and the TBI Endpoints Development Initiative. J. Head Trauma Rehabil. 33, 147–157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sollmann N., Echlin P.S., Schultz V., Viher P.V., Lyall A.E., Tripodis Y., Kaufmann D., Hartl E., Kinzel P., Forwell L.A., Johnson A.M., Skopelja E.N., Lepage C., Bouix S., Pasternak O., Lin A.P., Shenton M.E., and Koerte I.K. (2018). Sex differences in white matter alterations following repetitive subconcussive head impacts in collegiate ice hockey players. NeuroImage Clin. 17, 642–649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Holbrook T.L., Hoyt D.B., Coimbra R., Potenza B., Sise M., and Anderson J.P. (2005). Long-term posttraumatic stress disorder persists after major trauma in adolescents: new data on risk factors and functional outcome. J. Trauma 58, 764–771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Delaney-Black V., Covington C., Ondersma S.J., Nordstrom-Klee B., Templin T., Ager J., Janisse J., and Sokol R.J. (2002). Violence exposure, trauma, and IQ and/or reading deficits among urban children. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 156, 280–285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Daviss W.B., Mooney D., Racusin R., Ford J.D., Fleischer A., and McHugo G.J. (2000). Predicting posttraumatic stress after hospitalization for pediatric injury. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 39, 576–583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Meares S., Shores E.A., Taylor A.J., Batchelor J., Bryant R.A., Baguley I.J., Chapman J., Gurka J., and Marosszeky J.E. (2011). The prospective course of postconcussion syndrome: the role of mild traumatic brain injury. Neuropsychology 25, 454–465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ponsford J., Cameron P., Fitzgerald M., Grant M., Mikocka-Walus A., and Schönberger M. (2012). Predictors of postconcussive symptoms 3 months after mild traumatic brain injury. Neuropsychology 26, 304–313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Heim L.R., Bader M., Edut S., Rachmany L., Baratz-Goldstein R., Lin R., Elpaz A., Qubty D., Bikovski L., Rubovitch V., Schreiber S., and Pick C.G. (2017). The invisibility of mild traumatic brain injury: impaired cognitive performance as a silent symptom. J. Neurotrauma 34, 2518–2528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bruce B., Kirkland S., and Waschbusch D. (2007). The relationship between childhood behaviour disorders and unintentional injury events. Paediatr. Child Health 12, 749–754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ozer K., Gillani S., Williams A., and Hak D.J. (2010). Psychiatric risk factors in pediatric hand fractures. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 30, 324–327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Schwebel D.C., and Gaines J. (2007). Pediatric unintentional injury: behavioral risk factors and implications for prevention. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 28, 245–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Uslu M., Uslu R., Eksioglu F., and Ozen N.E. (2007). Children with fractures show higher levels of impulsive-hyperactive behavior. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 460, 192–195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Babikian T., Satz P., Zaucha K., Light R., Lewis R.S., and Asarnow R.F. (2011). The UCLA longitudinal study of neurocognitive outcomes following mild pediatric traumatic brain injury. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 17, 886–895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Gorman S., Barnes M.A., Swank P.R., Prasad M., and Ewing-Cobbs L. (2012). The effects of pediatric traumatic brain injury on verbal and visual-spatial working memory. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 18, 29–38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Loder R.T., Warschausky S., Schwartz E.M., Hensinger R.N., and Greenfield M.L. (1995). The psychosocial characteristics of children with fractures. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 15, 41–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Borsook D. (2012). Neurological diseases and pain. Brain 135, 320–344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Gennarelli T.A., and Wodzin E. (2006). AIS 2005: A contemporary injury scale. Injury 37, 1083–1091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. McCauley S.R., Wilde E.A., Barnes A., Hanten G., Hunter J.V., Levin H.S., and Smith D.H. (2014). Patterns of early emotional and neuropsychological sequelae after mild traumatic brain injury. J. Neurotrauma 31, 914–925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. McDonald S.J., Sun M., Agoston D.V., and Shultz S.R. (2016). The effect of concomitant peripheral injury on traumatic brain injury pathobiology and outcome. J. Neuroinflammation 13, 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Rabinowitz A.R., Li X., McCauley S.R., Wilde E.A., Barnes A., Hanten G., Mendez D., McCarthy J.J., and Levin H.S. (2015). Prevalence and predictors of poor recovery from mild traumatic brain injury. J. Neurotrauma 32, 1488–1496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wilde E.A., Li X., Hunter J.V., Narayana P.A., Hasan K., Biekman B., Swank P., Robertson C., Miller E., McCauley S.R., Chu Z.D., Faber J., McCarthy J., and Levin H.S. (2016). Loss of consciousness is related to white matter injury in mild traumatic brain injury. J. Neurotrauma 33, 2000–2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Oldfield R.C. (1971). The assessment and analysis of handedness: the Edinburgh inventory. Neuropsychologia 9, 97–113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control (2003). Report to Congress on Mild Traumatic Brain Injury in the United States: Steps to Prevent a Serious Public Health Problem. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [Google Scholar]

- 42. Teasdale G., and Jennett B. (1974). Assessment of coma and impaired consciousness. A practical scale. Lancet 2, 81–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Teasdale G., Maas A., Lecky F., Manley G., Stocchetti N., and Murray G. (2014). The Glasgow Coma Scale at 40 years: standing the test of time. Lancet Neurol. 13, 844–854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Levin H.S., O'Donnell V.M., and Grossman R.G. (1979). The Galveston orientation and amnesia test: A practical scale to assess cognition after head injury. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 167, 675–684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Carroll L.J., Cassidy J.D., Peloso P.M., Borg J., von Holst H., Holm L., Paniak C., Pépin M., and WHO Collaborating Centre Task Force on Mild Traumatic Brain Injury (2004). Prognosis for mild traumatic brain injury: results of the WHO Collaborating Centre Task Force on Mild Traumatic Brain Injury. J. Rehabil. Med. 43 Suppl, 84–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Levin H.S., O'Donnell V.M., and Grossman R.G. (1979). The Galveston Orientation and Amnesia Test. A practical scale to assess cognition after head injury. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 167, 675–684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Greenspan L., McLellan B.A., and Greig H. (1985). Abbreviated Injury Scale and Injury Severity Score: a scoring chart. J. Trauma 25, 60–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Committee on Injury Scaling (1998). Abbreviated Injury Scale. Association for the Advancement of Automotive Medicine: Arlington Heights, IL [Google Scholar]

- 49. Duhaime A.-C., Gean A.D., Haacke E.M., Hicks R., Wintermark M., Mukherjee P., Brody D., Latour L., Riedy G., and Common Data Elements Neuroimaging Working Group Members, Pediatric Working Group Members (2010). Common data elements in radiologic imaging of traumatic brain injury. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 91, 1661–1666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Jones D.K., Horsfield M.A., and Simmons A. (1999). Optimal strategies for measuring diffusion in anisotropic systems by magnetic resonance imaging. Magn. Reson. Med. 42, 515–525 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Netsch T., and van Muiswinkel A. (2004). Quantitative evaluation of image-based distortion correction in diffusion tensor imaging. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 23, 789–798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Wilde E.A., McCauley S.R., Chu Z., Hunter J.V., Bigler E.D., Yallampalli R., Wang Z.J., Hanten G., Li X., Ramos M.A., Sabir S.H., Vasquez A.C., Menefee D., and Levin H.S. (2009). Diffusion tensor imaging of hemispheric asymmetries in the developing brain. J. Clin. Exp. Neuropsychol. 31, 205–218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Bigler E.D., McCauley S.R., Wu T.C., Yallampalli R., Shah S., MacLeod M., Chu Z., Hunter J.V., Clifton G.L., Levin H.S., and Wilde E.A. (2010). The temporal stem in traumatic brain injury: preliminary findings. Brain Imaging Behav. 4, 270–282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Wilde E.A., Chu Z., Bigler E.D., Hunter J.V., Fearing M.A., Hanten G., Newsome M.R., Scheibel R.S., Li X., and Levin H.S. (2006). Diffusion tensor imaging in the corpus callosum in children after moderate to severe traumatic brain injury. J. Neurotrauma 23, 1412–1426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. McAllister T.W., Ford J.C., Flashman L.A., Maerlender A., Greenwald R.M., Beckwith J.G., Bolander R.P., Tosteson T.D., Turco J.H., Raman R., and Jain S. (2014). Effect of head impacts on diffusivity measures in a cohort of collegiate contact sport athletes. Neurology 82, 63–69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Davenport E.M., Whitlow C.T., Urban J.E., Espeland M.A., Jung Y., Rosenbaum D.A., Gioia G.A., Powers A.K., Stitzel J.D., and Maldjian J.A. (2014). Abnormal white matter integrity related to head impact exposure in a season of high school varsity football. J. Neurotrauma 31, 1617–1624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Xydakis M.S., Mulligan L.P., Smith A.B., Olsen C.H., Lyon D.M., and Belluscio L. (2015). Olfactory impairment and traumatic brain injury in blast-injured combat troops: A cohort study. Neurology 84, 1559–1567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Bigler E.D., and Maxwell W.L. (2012). Neuropathology of mild traumatic brain injury: relationship to neuroimaging findings. Brain Imaging Behav. 6, 108–136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Shultz S.R., Sun M., Wright D.K., Brady R.D., Liu S., Beynon S., Schmidt S.F., Kaye A.H., Hamilton J.A., O'Brien T.J., Grills B.L., and McDonald S.J. (2015). Tibial fracture exacerbates traumatic brain injury outcomes and neuroinflammation in a novel mouse model of multitrauma. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 35, 1339–1347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Yang L., Guo Y., Wen D., Yang L., Chen Y., Zhang G., and Fan Z. (2016). Bone fracture enhances trauma brain injury. Scand. J. Immunol. 83, 26–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Weckbach S., Hohmann C., Braumueller S., Denk S., Klohs B., Stahel P.F., Gebhard F., Huber-Lang M.S., and Perl M. (2013). Inflammatory and apoptotic alterations in serum and injured tissue after experimental polytrauma in mice: distinct early response compared with single trauma or “double-hit” injury. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 74, 489–498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Sun M., McDonald S.J., Brady R.D., O'Brien T.J., and Shultz S.R. (2018). The influence of immunological stressors on traumatic brain injury. Brain. Behav. Immun. 69, 618–628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Shaw P., Greenstein D., Lerch J., Clasen L., Lenroot R., Gogtay N., Evans A., Rapoport J., and Giedd J. (2006). Intellectual ability and cortical development in children and adolescents. Nature 440, 676–679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]