Abstract

Treatment of severe traumatic brain injury (TBI) in the intensive care unit focuses on controlling intracranial pressure, ensuring sufficient cerebral perfusion, and monitoring for secondary injuries. However, there are limited prognostic tools and no biomarkers or tests of the evolving neuropathology. Metabolomics has the potential to be a powerful tool to indirectly monitor evolving dysfunctional metabolism. We compared metabolite levels in simultaneously collected arterial and jugular venous samples in acute TBI patients undergoing intensive care as well as in healthy control volunteers. Our results show that, first, many circulating metabolites are decreased in TBI patients compared with healthy controls days after injury; both proline and hydroxyproline were depleted by ≥60% compared with healthy controls, as was gluconate. Second, both arterial and jugular venous plasma metabolomic analysis separates TBI patients from healthy controls and shows that distinct combinations of metabolites are driving the group separation in the two blood types. Third, TBI patients under heavy sedation with pentobarbital at the time of blood collection were discernibly different from patients not receiving pentobarbital. These results highlight the importance of accounting for medications in metabolomics analysis. Jugular venous plasma metabolomics shows potential as a minimally invasive tool to identify and study dysfunctional cerebral metabolism after TBI.

Keywords: human, jugular venous blood, metabolomics, pentobarbital

Introduction

Treatment of severe traumatic brain injury (TBI) in the neurological intensive care unit (NeuroICU) focuses on controlling intracranial pressures (ICP), ensuring sufficient cerebral perfusion, and closely monitoring for signs of secondary injuries. The occurrence of secondary brain injury in the NeuroICU has been associated with acute dysfunctional cerebral homeostasis, excitotoxicity, inflammation, and, ultimately, poor long-term outcomes. Even for severe TBI patients who may stay in the NeuroICU for several weeks, our best prognostic indicators are age and admission characteristics,1,2 and no biomarkers exist to predict secondary injuries or response to treatment. The identification of biomarkers of specific dysfunctional disease processes would be particularly powerful in developing individualized medicine to help the brain recover and prevent further injury in the NeuroICU.

With the end goal of improving prognostication of long-term outcomes or secondary injuries, promising biochemical biomarkers have been identified in blood plasma collected early after TBI that significantly improve on clinical prognostic models alone.3–5 Circulating metabolites, proteins, and lipids are analyzed to characterize how cerebral and systemic homeostasis are changed by the injury and/or to characterize the ongoing disease process, including short- and long-term changes in cerebral metabolism. Quantifying brain-specific proteins or protein breakdown products systemically requires that these biomolecules are able to cross the blood–brain barrier (BBB). In contrast, metabolites are the reactants and products of biochemical reactions and participate in signaling between cells and organs throughout the body; although the origin of metabolites may not be attributed to the brain specifically, concentrations are not always dependent on the permeability of the BBB.

In severe TBI patients, high variability is expected, not only among patients and among injuries, but also over time, as the neuropathology evolves and NeuroICU treatments are given. An ideal biomarker would be able to isolate the injury biology and would change in response to disease evolution and/or treatment. We set out to explore to what degree the severe TBI metabolome after several days of NeuroICU care reflects biological processes associated with the injury as compared with medications and nutrition received. In addition to comparing the plasma metabolome from TBI patients and from healthy control (HC) volunteers, we compared the multivariate results among TBI patients receiving specific sedative medications (propofol, midazolam, or pentobarbital) and to the nutritional kilocalories received in the NeuroICU.

To that end, we conducted a prospective observational cohort study of blood plasma metabolite profiles in TBI patients. Liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LCMS) was used to compare arterial and jugular venous plasma metabolite profiles of 26 severe TBI patients to 6 HC. Univariate and multivariate analysis of 69 specific metabolites was performed to compare between groups, between arterial and jugular venous blood samples and, within the TBI population, among injury severity, sedative medications, enteral nutrition provisions, and 6 month outcomes. Linear modeling of multivariate results determined group separation, and the metabolite scalar projection along the axis of group separation was calculated to assess the level of contribution to group separation. We hypothesized that the blood plasma metabolome would discriminate severe TBI patients from HC volunteers; that arterial and jugular venous blood would generate different metabolomic fingerprints; and that jugular venous blood would be more reflective of the TBI neuropathology, discriminating favorable and poor 6 month outcomes.

Methods

TBI cohort

Consecutive patients consented to the UCLA Brain Injury Research Center (BIRC) study of moderate to severe TBI patients between 2010 and 2013 were included. Eligible patients were ≥18 years of age, were admitted within 24 h of a non-penetrating brain injury had post-resuscitation Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) scores ≤8 or deterioration to GCS ≤8 within 24 h of injury, and required mechanical ventilation and ICP monitoring. Patients with terminal illness, pre-existing neurological disorders, or spinal cord injury were excluded from the study. UCLA Medical Institutional Review Board for human research approved the protocol and informed consent was received from the patients' legal representatives. TBI patients were treated in accordance with the Brain Trauma Foundation and American Association of Neurological Surgeons (AANS)/Congress of Neurological Surgeons (CNS) TBI Guidelines. General management goals included maintenance of ICP <20 mm Hg and cerebral perfusion pressure (CPP) >60 mm Hg and were obtained using a standardized treatment protocol including head elevation, cerebrospinal fluid drainage, jugular venous monitoring, sedation, and more.6–8

Following consent, blood was drawn daily, subject to constraints including catheter removal or declining health status. Blood was collected in heparin-coated tubes and immediately placed on ice. After centrifugation, samples were stored at −80 °C until the time of analysis. Samples selected for the following analysis were the first blood sample collected to include both arterial and jugular venous blood. Neurological outcome was assessed at time of discharge and at 6 months post-injury by research staff using the Glasgow Outcome Scale extended (GOSe). Sedative medications at the time of blood draw were determined by reviewing patient charts. Enteral nutrition data were extracted from the UCLA BIRC database, and reflect the cumulative kilocalories delivered in the preceding 24 h.

HC subjects

Healthy volunteers were recruited with posted notices and Internet advertisements from UCLA and surrounding areas, and consented to participate in a lactate tracer infusion study, as described in the studies by Glenn and coworkers.8,9 Inclusion criteria for controls included no history of TBI, being weight stable for 6 months, not currently receiving medications, and having normal lung function. Control subjects had a jugular venous bulb catheter and radial arterial line placed ahead of the infusion study. In our analysis, arterial and jugular blood drawn prior to the tracer infusion study was included.

Mass spectrometry protocol

Plasma was thawed and prepared for analysis by deproteinization with methanol (Sigma Aldrich) followed by solvent removal. Prior to deproteinization of plasma, we added 5 nmol DL-Norvaline (Sigma Aldrich) to 20 μL plasma to serve as an internal standard. Metabolite relative concentrations were determined by mass spectrometry methods as previously published.10 LCMS was analyzed with an UltiMate 3000RSLC (Thermo Scientific) coupled to a Q Exactive mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific). The Q Exactive was run with polarity switching (+4.00 kV / −4.00 kV) in full scan mode with an m/z range of 70–1050. Separation was achieved using (A) 5 mM NH4AcO (pH 9.9), and (B) ACN. The gradient started with 15% (A) going to 90% (A) over 18 min, followed by an isocratic step for 9 min and reversal to the initial 15% (A) for 7 min. Metabolites were quantified with TraceFinder 3.3 (Thermo Scientific) using accurate mass measurements (≤3 ppm) and retention times established by running pure standards.

A total of six replicates of all arterial and jugular venous samples were analyzed by LCMS, totaling 378 samples. Plasma samples were prepared for mass spectrometry analysis in eight batches, separating replicates one through three from replicates four through six between analytical batches. Quality control samples, including a human lung adenocarcinoma cell line (A549, ATCC, Manassas, VA), were run in each batch. A total of 156 specific metabolites were assigned across all batches. Metabolites that were not detected in any one batch, in any one patient's samples, or in at least half of the samples, were removed from the analysis, leaving 76 metabolites. Metabolites were categorized using the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG),11 the Human Metabolome Database web site,12 and MetScape pathway-based networks.13 Seven metabolites were not products or reactants of human cellular metabolism and, instead, were products of microbial metabolism or phytochemicals; these were removed from the analysis, leaving 69 metabolites.

Batch effects were removed in R, version 3.4.0,14 using the multivariate integrative method (MINT), as implemented in the mixOmics package.15,16 Following batch correction of the full data set, metabolite concentrations were centered and unit-variance scaled prior to further analyses.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was conducted in R, version 3.4.0.14 A robust equivalent of the t test, the Yuen test, was used to compare between TBI and HC cohort demographics.17 Fisher's Exact Test was used to compare sex ratios. The dependent Yuen test modified was used to compare GCS and GOSe scores over time.

All univariate analyses were conducted on log-transformed relative metabolite levels. Univariate analysis of the 69 metabolites was accomplished by mixed-effects modeling with fixed effect of group (TBI or HC) and random effect of ID to account for replicate samples, analyzing arterial and jugular venous blood samples separately.18 All p values were corrected for multiple comparisons by the Benjamini–Hochberg method to control for a 5% false discovery rate. We considered the test results significant when the multiple comparison-adjusted p values were below a 0.05 threshold. We also performed univariate mixed-effects analysis to compare metabolite levels between injury severities (fixed effect GCS3 vs. GCS not 3, random effect ID) and between arterial and jugular venous samples (fixed effect blood, random effect ID). In the case of significant differences between arterial and jugular venous blood, post-hoc mixed-effects modeling was performed, including group and the group–blood interaction fixed effects, followed by model selection with multi-model inference. The best approximating model was chosen from all possible models by minimizing residuals and comparing Akaike information criteria (AIC).19 Finally, for analyzing the association between metabolite levels and enteral nutrition received, the percentage bend correlation coefficient was determined using the average of the log-transformed metabolite levels.

Multivariate analysis was performed on arterial and jugular venous blood data sets separately using the mixOmics package.15 Prior to multivariate analysis, each subjects' six replicate samples were averaged using the trimmed mean. Principal components analysis (PCA) was performed to compare the 69 metabolites quantified in each TBI (26) and HC (6) sample. Group separation in PC scores plots was defined as a significant difference among PC scores (p < 0.05) with linear modeling. Separation of PC scores based on characteristics of TBI patients, such as 6 month outcomes, injury severity, or medications received at the time of blood draw, were also defined as a significant difference between PC scores (either PC1 or PC2 p < 0.05) using linear modeling.

Metabolite contributions to separating between groups were assessed in two steps. First, the scalar projection of a metabolite loading on the axis connecting the average HC PC score from the average TBI score, with slope m, was calculated as follows.

|

Metabolites with larger scalar projections are considered to contribute more to group separation than those with smaller scalar projections. Second, the scalar offset of a metabolite from the axis with slope m and scalar projection sp was calculated as follows

|

which is proportional to the angle between vectors. The absolute value of the ratio between a metabolite's scalar projection and scalar offset increases as the scalar offset decreases. Therefore, the largest contributors have a large scalar projection and/or a small scalar offset with moderate scalar projection.

Results

The study cohort included 26 severe TBI patients and 6 HC subjects (Table 1). There were no significant differences in median age (TBI: 34 [IQR 22–50]; control: 34 [IQR 25– 42]; p = 0.84) or sex ratio (p = 1) between TBI and HC subjects. Injuries were characterized as severe by the post-resuscitation GCS, with a median of 3.9 (IQR 3.0–7.4]. GCS scores at the time of blood collection were not significantly different from the post-resuscitation GCS, with a median of 3.4 (IQR 3.0–6.0) (p = 0.56). Blood from TBI patients was collected at a median post-injury day (PID) of 4.5 (IQR 3.4 – 5.7).

Table 1.

Patient and Healthy Control Cohort Demographics

| Demographics | Injury description | At blood collection | Outcome | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ID | Age | Sex | Injury Mechanism | GCS post-res | Intubated | PID | GCS | Sedation Medications | GOSe at discharge | GOSe at 6 months |

| TBI-A | 25 | M | PVA | 3 | Yes | 5.5 | 3 | PTB | 3 | 7 |

| TBI-B | 27 | M | Fall | 3 | Yes | 4.2 | 3 | PTB | 1 | 1 |

| TBI-C | 17 | M | PVA | 8 | No | 5.7 | 3 | MDL | 2 | 4 |

| TBI-D | 60 | M | MVA | 3 | Yes | 4.5 | 3 | PTB | 2 | LTFU |

| TBI-E | 19 | M | Fall | 3 | Yes | 7.9 | 3 | PTB | 2 | 4 |

| TBI-F | 23 | M | Fall | 7 | Yes | 1.6 | 7 | MDL | 3 | 8 |

| TBI-G | 71 | F | PVA | 3 | Yes | 4.9 | 6 | 1 | 1 | |

| TBI-H | 68 | F | MVA | 5 | Yes | 4.6 | 6 | 1 | 1 | |

| TBI-I | 40 | M | MCA | 7 | Yes | 3.7 | 8 | PRF | 3 | 5 |

| TBI-J | 60 | M | BVA | 7 | Yes | 6.0 | 3 | PRF | 2 | 3 |

| TBI-K | 44 | M | Fall | 11 | Yes | 5.9 | 3 | PTB | 3 | 5 |

| TBI-L | 60 | M | Fall | 14 | No | 3.0 | 6 | PRF,MDL | 2 | 3 |

| TBI-M | 22 | M | Blunt | 5 | Yes | 2.5 | 3 | MDL | 4 | LTFU |

| TBI-N | 54 | M | Fall | 8 | No | 1.9 | 3 | 3 | 1 | |

| TBI-O | 18 | M | Fall | 3 | Yes | 4.0 | 3 | MDL | 3 | 4 |

| TBI-P | 47 | M | Blunt | 11 | No | 3.4 | 3 | PTB | 3 | 6 |

| TBI-Q | 41 | M | PVA | 3 | Yes | 4.5 | 6 | 2 | 2 | |

| TBI-R | 34 | M | Fall | 3 | Yes | 5.4 | 3 | MDL | 2 | 3 |

| TBI-S | 25 | F | MVA | 3 | Yes | 2.6 | 6 | MDL | 2 | 4 |

| TBI-T | 16 | M | MVA | 3 | Yes | 3.9 | 4 | MDL | 2 | 3 |

| TBI-U | 16 | F | MVA | 3 | Yes | 3.8 | 7 | 2 | 7 | |

| TBI-V | 27 | F | MVA | 3 | Yes | 5.4 | 6 | 2 | 2 | |

| TBI-W | 38 | F | Fall | 7 | Yes | 3.6 | 3 | PTB | 4 | 5 |

| TBI-X | 45 | M | MCA | 3 | Yes | 6.5 | 3 | PTB | 4 | 5 |

| TBI-Y | 37 | F | MVA | 3 | Yes | 8.1 | 10 | PRF | 4 | 5 |

| TBI-Z | 23 | M | PVA | 8 | Yes | 7.0 | 3 | PTB | 2 | 3 |

| HC-A | 33 | M | ||||||||

| HC-B | 24 | M | ||||||||

| HC-C | 19 | M | ||||||||

| HC-D | 51 | M | ||||||||

| HC-E | 39 | M | ||||||||

| HC-F | 37 | F | ||||||||

Demographics include sex and age at injury; traumatic brain injury (TBI) patient injury description, including injury mechanism, post-resuscitation Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS post-res), and intubation status at time of admission; timing and sedation at the time of blood collection, including post-injury day (PID), current GCS, and sedation medications received; and TBI patient outcomes, including Glasgow Outcome Scale extended (GOSe) scores at discharge and at 6 months post-injury follow-up. Two subjects were lost to follow up (LTFU).

Blunt, blunt head trauma; BVA, bicycle versus automobile; Fall, ground level fall; MCA, motorcycle accident; MVA, motor vehicle accident; PVA, pedestrian versus automobile; MDL, midazolam; PRF, propofol; PTB, pentobarbital.

Three patients died in the neuroICU, and the median GOSe at discharge was 2.2 (IQR 1.9–3.1). At 6 months post injury, median GOSe was 3.8 (IQR 2.3–5.1), with 2 of 26 TBI patients lost to follow-up after 6 months. For 21 TBI patients who survived the ICU and returned 6 months post injury, there was an average increase in the GOSe score of 1.6 (95% CI 1.1–2.1) (p < 0.001).

Univariate analyses

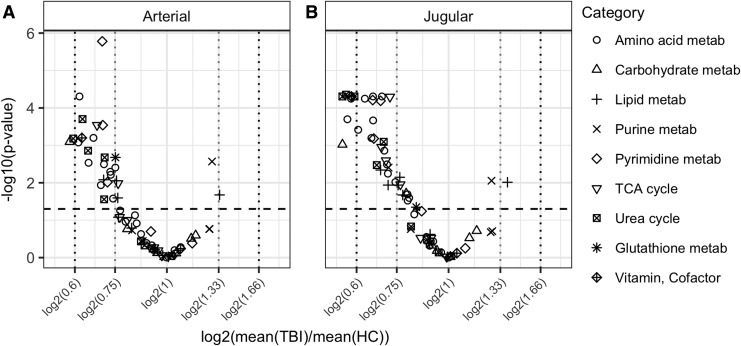

The majority of metabolites were at decreased concentrations in TBI blood compared with HC, as illustrated in Figure 1. In arterial plasma, two metabolites are ≤60% the concentration of HC (proline [Pro] and gluconate [GlcA]); in jugular blood, seven metabolites are ≤60% (asparagine [Asn], Pro, serine [Ser], hydroxyproline [Pro-OH], GlcA, niacinamide, and citrulline).

FIG. 1.

Visualization of changes in metabolites between groups by volcano plot in (A) arterial and (B) jugular venous blood. Volcano plots visualize the fold change between groups as a function of the significance level of the statistical test performed. Metabolites above the horizontal dashed line are considered to significantly change between groups (false discovery rate [FDR] adjusted p value <0.05). Vertical dotted lines indicate, from left to right, fold changes of 0.6, 0.75, 1.33, and 1.66.

Three of the 69 metabolites were significantly different between arterial and jugular venous blood. There was a net cerebral uptake of glucose-6-phosphate (G6P-F6P), as characterized by a significant decrease in jugular venous blood from arterial levels. There was a net cerebral release of xanthine and choline. The best models identified by multi-model inference showed that all models were improved by including additional fixed effects (Table 2). For xanthine, multi-model inference determined that the best model included blood–group interactions, which indicates that the HC group had negligible cerebral xanthine release (p = 0.78), whereas TBI cerebral xanthine release was significant (p = 0.050).

Table 2.

Mixed Effects Model Results for Glucose-6-Phosphate, Choline, and Xanthine

| Metabolite | Description | Estimate | 95% CI | t value (df) | p value | Model equation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose-6-Phosphate | β0 | Intercept | 1.16 | (0.98 – 1.34) | 12.7 (345) | <0.001 |  |

| β1 | Blood (J) | −0.09 | (−0.13 – −0.04) | −3.5 (345) | <0.001 | ||

| β2 | Group (TBI) | −0.23 | (−0.43 – −0.02) | −2.3 (30) | 0.029 | ||

| Choline | β0 | Intercept | 1.28 | (1.07 – 1.48) | 12.4 (345) | <0.001 |  |

| β1 | Blood (J) | 0.07 | (0.03 – 0.11) | 3.3 (345) | 0.001 | ||

| β2 | Group (TBI) | −0.30 | (−0.53 – −0.07) | −2.7 (30) | 0.012 | ||

| Xanthine | β0 | Intercept | 1.12 | (0.93 – 1.30) | 12.0 (344) | <0.001 |  |

| β1 | Blood (J) | −0.02 | (−0.15 – 0.11) | −0.3 (344) | 0.78 | ||

| β2 | Group (TBI) | −0.13 | (−0.34 – 0.08) | −1.3 (30) | 0.20 | ||

| β3 | Blood × Group | 0.14 | (0.00 – 0.28) | 2.0 (344) | 0.050 | ||

Each metabolite model includes the coefficient description (the intercept corresponds to healthy control arterial blood plasma), estimate, 95% confidence interval (95% CI), t value and degrees of freedom (df), and p value. The model equation determined by multi-model inference for each metabolite is presented.

TBI, traumatic brain injury; J, jugular venous blood.

There were no statistically significant differences between metabolite levels comparing TBI patients when grouped by injury severity (GCS post-resuscitation 3 or 4–15; data not shown) nor when grouped by outcome (GOSe at 6 months 1–4 or 5–8; data not shown). There were no significant changes between metabolites comparing TBI patients on propofol or midazolam with those not on those drugs. Glycerol was significantly decreased by 74% (p = 0.024) in patients receiving pentobarbital (TBI + PTB) compared with TBI patients not on pentobarbital. Only valine (Val) in jugular venous blood was significantly positively correlated with kilocalories received (rpb = 0.71, p < 0.001).

Unsupervised multivariate analysis

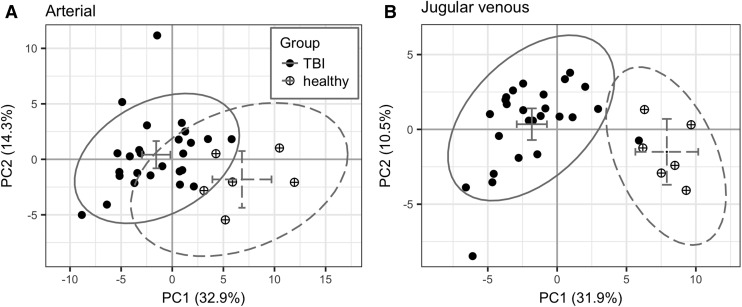

We performed exploratory analysis of the metabolite data with PCA on blood plasma metabolites to compare the PC scores of TBI and HC groups. Two principal components are presented in the results, modeling 47.2 and 42.4% of the total variance in arterial and jugular blood, respectively. Severely injured TBI patients separated from HC in arterial and jugular venous blood plasma on PC1 (p < 0.001) but not on PC2 (p = 0.12 for arterial, p = 0.13 for jugular venous blood plasma, Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Principal component scores plots for (A) arterial and (B) jugular venous blood plasma samples (closed circle = traumatic brain injury [TBI]; circle-plus = healthy controls [HC]). The 95% confidence ellipse and group averages are illustrated with solid and dotted gray lines for TBI and HC, respectively (horizontal and vertical error bars are the 95% confidence intervals for the group averages in PC1 and PC2, respectively).

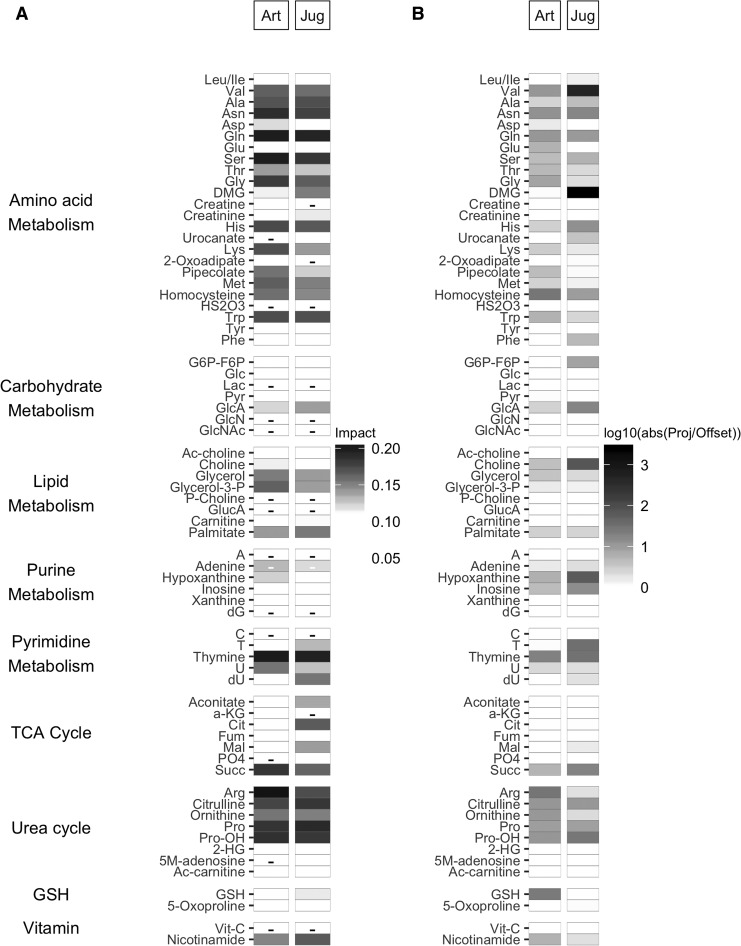

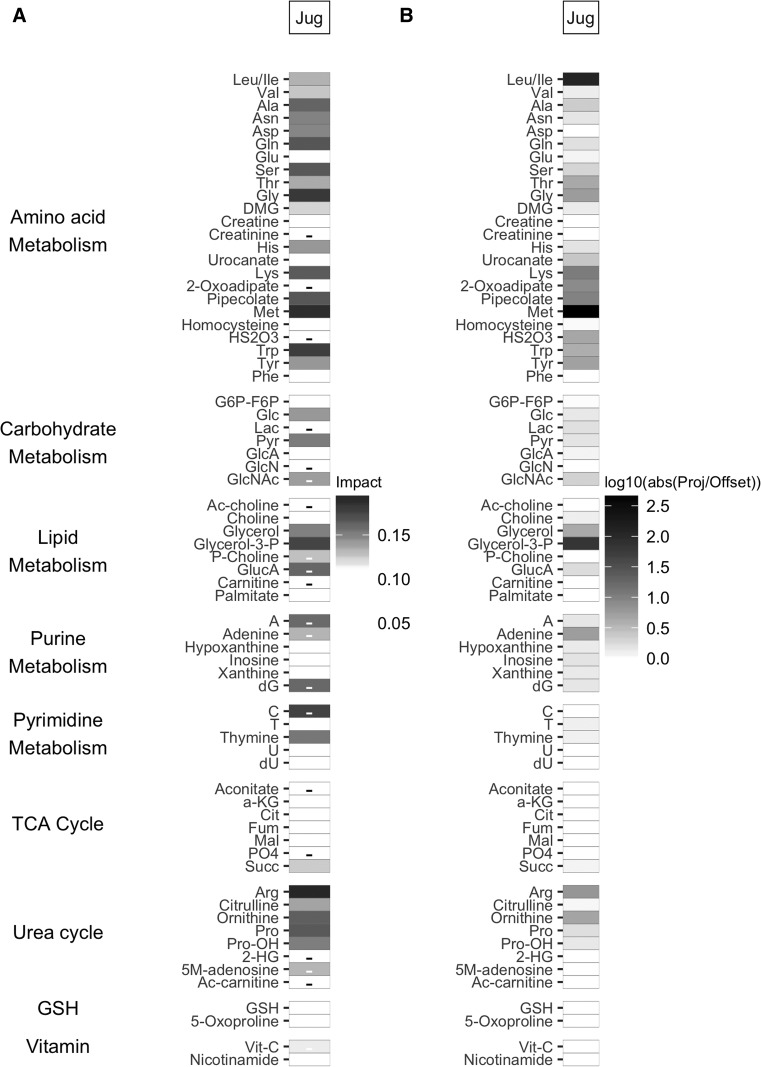

The relative contributions of metabolite loadings to group separation were evaluated by the scalar projection along the vector connecting the group PC score averages (line of slope −0.27 for arterial and −0.19 for jugular venous blood). The top seven metabolite loading scalar projections (Fig. 3) in arterial blood were amino acids Ser, glutamine (Gln), and Asn; amino acids involved in the urea cycle arginine (Arg), Pro, and Pro-OH; and pyrimidine thymine. In jugular venous blood, six of seven loadings were the same (Ser, Gln, Asn, Pro, Pro-OH, thymine) and included urea cycle amino acid citrulline rather than Arg. The quantity of negative scalar projections was less than that of positive scalar projections, and their strength was overall weaker. The patterns of scalar projections are similar between blood types; the patterns of ratios between the scalar projection and offset are less similar. The ratios between the scalar projection and offset reveal that Val and dimethylglycine (DMG) play an important role in jugular venous blood plasma, as they are both highly parallel to the axis separating the groups.

FIG. 3.

(A) Principal component loading scalar projection visualization for arterial (Art, left) and jugular venous (Jug, right) blood plasma samples. The shading of the tile plot is equal to the metabolite vector scalar projection; those metabolites with negative scalar projections (i.e., toward the traumatic brain injury [TBI] group) have a minus sign in the corresponding tile. (B) Principal component loadings ratio of scalar projection divided by offset for Art (left) and Jug venous (right) blood plasma samples. The shading of the tile plot corresponds to the base 10 logarithmic transform of the ratio of the scalar projection and the scalar offset.

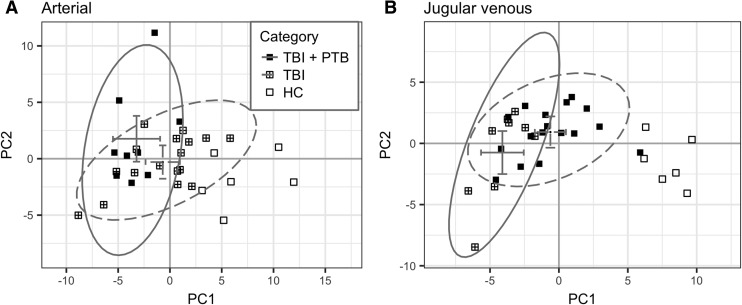

Unsupervised multivariate analysis did not separate between favorable and poor TBI patient 6 month outcomes or between patients based on post-resuscitation injury severity (GCS 3 or GCS 4–15). Of the three sedative medications analyzed, no separation was observed for either propofol or midazolam. There was significant separation between patients receiving pentobarbital at the time of blood collection and those not receiving pentobarbital in jugular venous blood plasma in PC1 (p < 0.001) but not in arterial blood. The axes separating TBI patients based on pentobarbital were rotated from the axes separating TBI and HC (Fig. 4) by 36 degrees. The metabolites with the largest scalar contribution toward TBI include Arg, Met, glycine (Gly), tryptophan (Trp), glycerol-3-P, and Gln (Fig. 5). The ratio between scalar projection and offset reveal that leucine and/or isoleucine (Leu/Ile), Met, and glycerol-3-P are highly parallel to the axis of separation. The metabolites with the largest scalar contribution toward the TBI + PTB group included cytidine (C) as well as some weaker contributions from other purine and pyrimidine metabolites.

FIG. 4.

Principal components scores plot for (A) arterial and (B) jugular venous blood plasma samples (closed square = traumatic brain injury [TBI] + pentobarbital [PTB]; square-plus = TBI; open square = healthy controls). The 95% confidence ellipse and group averages are illustrated with solid and dashed gray lines for TBI + PTB and TBI, respectively (horizontal and vertical error bars are the 95% confidence intervals for the group averages in PC1 and PC2, respectively).

FIG. 5.

(A) Principal component loading scalar projection visualization for jugular venous blood plasma samples between traumatic brain injury (TBI) + pentobarbital (PTB) and TBI groups. The shading of the tile plot is equal to the metabolite vector scalar projection; those metabolites with negative scalar projections (toward the TBI + PTB group) have a minus sign in the corresponding tile. (B) Principal component loadings ratio of scalar projection divided by offset for jugular venous blood plasma samples between TBI + PTB and TBI groups. The shading of the tile plot corresponds to the base 10 logarithmic transform of the ratio of the scalar projection and the scalar offset.

Discussion

Multiple comparison corrected univariate and multivariate analysis of 69 identified metabolites in human blood revealed: (1) persistent depletion of circulating metabolites days after TBI, including urea cycle metabolites and key proteinogenic amino acids; (2) separation between healthy and TBI subjects in both arterial and jugular venous blood, showing altered amino acid metabolism as the driving force distinguishing groups; and (3) discrimination between TBI patients receiving pentobarbital and those not in the metabolome of jugular venous blood. This report is the first metabolomics analysis to focus on the acute injury period after severe TBI, a median of 4.5 days post-injury, and to include both arterial and jugular venous blood plasma in the analysis. This work explores the power of metabolomics to identify deleterious cerebral biochemical processes that continue and/or evolve over time, that exist in the context of systemic stresses and trauma, and that are altered by medications delivered as a part of the patient's care. Careful study of such confounders is required to advance metabolomics toward aiding individualized care.

First, circulating metabolite concentrations tend to be significantly lower in TBI patients in the acute period following injury. We found that key amino acids were depleted by ≥60% compared with HC. Key components of extracellular matrix remodeling, Pro and Pro-OH, were depleted in TBI plasma, which is consistent with results reported in severe TBI samples collected within 24 h of the injury,4,20 and demonstrates the prolonged nature of post-TBI metabolic dysfunction, cellular repair, and muscle catabolism. Pro and Pro-OH together make up 25% of collagen residues, the most abundant protein in the body, and are considered nutritionally essential following injury, being used to produce Arg and Gly.21,22 Increased Pro oxidase activity, a mitochondrial inner membrane enzyme catalyzing the transfer of electrons from Pro, has been shown to be especially important when nutrients and energy substrates are depleted. GlcA was significantly decreased in both arterial and jugular venous blood (53% and 54%, respectively). GlcA has been shown to have antioxidative properties to protect plasma proteins from peroxynitrite-induced damage.23 D-gluconic acid metabolism feeds into the pentose phosphate pathway,24 which has been shown to be upregulated after TBI.25,26 A reduced metabolite concentration reflects increased demand and/or decreased production; metabolite turnover or flux, which can be measured with stable isotope labeled tracer studies, is required to characterize the metabolic dysfunction leading to reduced levels of circulating metabolites.

During this period of critical care, the body is highly catabolic, breaking down lean muscle mass to provide energy substrates to vital organs.27,28 This supports the concept that decreased amino acid concentrations in our cohort of critically ill TBI patients reflects both increased production and increased use. There was no evident association between the persistent depletion of these key amino acids and the rate of enteral nutrition provisions, with the exception of a positive correlation between jugular venous plasma Val and enteral kilocalories received. PCA scores and enteral nutrition rates were not significantly correlated. Further study of the mechanisms of dysfunctional metabolism may reveal therapeutic benefits to the augmentation of key circulating metabolites caused by the cerebral energy crisis ongoing after injury, recruiting all possible mechanisms to generate energy, restore homeostasis, and repair cellular damage.

Second, metabolomic analysis separates TBI from HC subjects in both arterial and jugular venous blood plasma. We elected to explore identified metabolites rather than including all LCMS features in an untargeted fashion to aid in biological interpretability. One limitation of this method is that hundreds of features were narrowed to the 69 metabolites included in our analysis. We were also interested in comparing simultaneously collected arterial and jugular venous blood. To assess the variability introduced at sample preparation and between analytical batches, we replicated all samples six times and prepared replicates in two separate batches. Following batch correction, the intra-batch average distance decreased from a median of 5.7 to 1.1, and all but one set of sample replicates were indistinguishable among batches. We used the metabolite trimmed mean of the six replicate samples for multivariate analysis. Further, the univariate and multivariate analytic results were stable when alternative batch correction methods were employed (specifically the LIMMA and ComBat algorithms, results not shown).

Pentobarbital intravenous infusions had a discernible impact on unsupervised metabolomic analysis, and demonstrates the importance of accounting for medications in human metabolomics studies. The axes separating TBI patients receiving pentobarbital and those not was 36 degrees rotated from the TBI-HC axis in jugular venous blood, indicating that the drug effect is not orthogonal to the group effect, and there was overlap of the 95% confidence ellipses, consistent with the overlap of the group PC scores. Pentobarbital infusion reduces intracranial pressure by suppressing brain metabolic demand, resulting in reduced cerebral blood flow and blood volume; 9 of the 26 TBI patients were receiving pentobarbital. Although only glycerol was significantly reduced in univariate comparisons between the TBI and TBI + PTB groups, our results suggest that the drug changes the overall pattern of circulating metabolites. No clear group separation occurred for the other sedatives investigated here: propofol and midazolam. Injury severity groups, categorized as GCS 3 or GCS 4–15, and 6 month outcome groups, categorized as poor or favorable, overlapped when overlaid on PCA plots.

Although separation between groups was evident in both arterial and jugular venous PCA, jugular venous blood had very small overlap between the 95% confidence ellipses (Fig. 2). The patterns of loading scalar projections between blood types are largely similar (Fig. 3), with large contributions to group separation from the urea cycle, the primary nitrogen recycling and disposal pathway; from amino acid metabolism, including Gln, Ser, and Asn; and from the pyrimidine thymine. The relative angle between the axis of group separation and metabolite vectors identifies metabolites with loadings close to parallel to group separation. Arterial and jugular venous patterns of the metabolite's ratio of scalar projection and offsets are more clearly different from one another than the scalar projections. Metabolites with a large ratio between the scalar projection and offset in jugular venous plasma were DMG and Val. DMG is produced when choline is metabolized to serve as a methyl donor when converting homocysteine to methionine. Altered methionine metabolism in TBI patients has been suggested to influence the pathology in the injured brain,29 and evidence that altered patterns persist for days after injury suggests that further study of altered amino acid metabolic pathways is needed.

This is the first metabolomics analysis of jugular venous blood in TBI patients; jugular venous blood is routinely used to assess cerebral metabolism through jugular venous oximetry. Blood exiting cerebral circulation predominantly drains through the internal jugular vein, and metabolite concentrations reflect the global balance between cerebral uptake and release. Notably, patients receiving pentobarbital intravenously at the time of blood draw tended to have smaller PC scores (Fig. 4B) in jugular venous blood, but only glycerol was found to be significantly reduced by univariate methods. Lactate, glutamate, and aspartate were found to be at significantly reduced levels in cerebral extracellular fluid for patients in a pentobarbital coma,30 and our findings highlight how circulating metabolites are impacted. The metabolites with large scalar projections and large ratios of scalar projection to offset include Met, glycerol-3-P, Arg, Trp, and Leu/Ile. In contrast to the comparison between TBI and HC groups, there are considerably large negative scalar projections (cytidine, for example) that would favor the TBI + PTB group, but interpretation is difficult, because the scalar projections to offset ratios are small.

Two limitations of these results are the relatively low number of subjects compared with the metabolites measured, and the lack of a critically ill control population; our results are consistent with many of the fold changes between traumatic orthopedic injured patients and severe TBI reported in supplementary table in the study by Orešič and coworkers,4 and consistent with the fold changes reported by Dash and coworkers.29,31,32 A strength of our results is that each blood sample quantified and analyzed had six separate replicates, prepared and run in two separate batches.

The use of MS-based metabolomics to analyze both arterial and jugular venous blood has not previously been reported; however, simultaneous measurement of metabolite levels in arterial and jugular venous blood has been utilized in studying post-TBI cerebral metabolism for decades. Univariate analysis of arterial and jugular venous differences demonstrated that xanthine trended toward cerebral release in the TBI group, without discernible changes between blood types in HC. Evidence of increased extracellular xanthine during jugular venous oxygen desaturations has been demonstrated in the cerebral microdialysate of severe TBI patients.33 The average arterial minus the average jugular venous levels for almost 20% of TBI patients (n = 5) did not follow the trend of xanthine release. Xanthine had very limited impact on group separation, and it may be beneficial to proceed to target specific metabolites with high sensitivity when conducting arterial–venous comparisons of metabolite concentrations, as suggested in the one published example of metabolomics applied across the forearm muscle vascular flow.34

Blood plasma metabolomics shows potential as a biomarker of injury biology to study dysfunctional cerebral biochemical processes. As has been previously published for patients in the first 24 h post-injury, our results show that alterations to arginine, proline, and methionine metabolism continue days after injury. The cerebral impact of prolonged depletion of key amino acids in TBI patients, in spite of enteral nutrition provision, is unknown. Finally, accounting for medications in metabolomics studies should be encouraged in TBI critical care.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the nursing and research staff at the Ronald Reagan UCLA Medical Center neurological intensive care unit. This material is based on work supported by the UCLA Brain Injury Research Center and National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant number P01NS058489.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1. MRC CRASH Trial Collaborators, Perel P., Arango M., Clayton T., Edwards P., Komolafe E., Poccock S., Roberts I., Shakur H., Steyerberg E., and Yutthakasemsunt S. (2008). Predicting outcome after traumatic brain injury: practical prognostic models based on large cohort of international patients. BMJ 336, 425–429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Steyerberg E.W., Mushkudiani N., Perel P., Butcher I., Lu J., McHugh G.S., Murray G.D., Marmarou A., Roberts I., Habbema J.D.F., and Maas A.I.R. (2008). Predicting outcome after traumatic brain injury: development and international validation of prognostic scores based on admission characteristics. PLoS Med. 5, e165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Czeiter E., Mondello S., Kovacs N., Sandor J., Gabrielli A., Schmid K., Tortella F., Wang R.L., K.K.W. Hayes Barzo, P., Ezer E., Doczi T., and Buki A. (2012). Brain injury biomarkers may improve the predictive power of the IMPACT outcome calculator. J. Neurotrauma 29, 1770–1778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Orešič M., Posti J.P., Kamstrup-Nielsen M.H., Takala R.S.K., Lingsma H.F., Mattila I., Jantti S., Katila A.J., Carpenter K.L.H., Ala-Seppala H., Kyllonen A., Maanpaa H.-R., Tallus J., Coles J.P., Heino I., Frantzen J., Hutchinson P.J., Menon D.K., Tenovuo O., and Hyotylainen T. (2016). Human Serum metabolites associate with severity and patient outcomes in traumatic brain Injury. EBioMedicine 12, 118–126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mondello S., Akinyi L., Buki A., Robicsek S., Gabrielli A., Tepas J., Papa L., Brophy G.M., Tortella F., Hayes R.L., and Wang K.K. (2012). Clinical utility of serum levels of ubiquitin c-terminal hydrolase as a biomarker for severe traumatic brain injury. Neurosurgery 70, 666–675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Vespa P., McArthur D., Stein N., Huang S.-C., Shao W., Filippou M., Etchepare M., Glenn T., and Hovda D. (2012). Tight glycemic control increases metabolic distress in traumatic brain injury: a randomized controlled within-subjects trial. Crit. Care Med. 40, 1923–1929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Vespa P., Miller C., McArthur D., Eliseo M., Etchepare M., Hirt D., Glenn T., Martin N., and Hovda D. (2007). Nonconvulsive electrographic seizures after traumatic brain injury result in a delayed, prolonged increase in intracranial pressure and metabolic crisis. Crit. Care Med. 35, 2830–2836 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Glenn T.C., Martin N.A., Horning M.A., McArthur D.L., Hovda D.A., Vespa P.M., and Brooks G.A. (2015). Lactate: brain fuel in human traumatic brain injury. A comparison to normal healthy control subjects. J. Neurotrauma 32, 820–832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Glenn T.C., Martin N.A., McArthur D.L., Vespa P.M., Horning M.A., Johnson M.L., and Brooks G.A. (2015). Endogenous nutritive support following traumatic brain injury: peripheral lactate production for glucose supply via gluconeogenesis. J. Neurotrauma 32, 811–819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Thai M., Graham N.A., Braas D., Nehil M., Komisopoulou E., Kurdistani S.K., McCormick F., Graeber T.G., and Christofk H.R. (2014). Adenovirus E4ORF1-induced MYC activation promotes host cell anabolic glucose metabolism and virus replication. Cell Metab. 19, 694–701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kanehisa M., and Goto S. (2000). KEGG: Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 27–30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wishart D., Tzur D., Knox C., Eisner R., Guo A., Young N., Cheng D., Jewell K., Arndt D., Sawhney S., Fung C., Nikolai L., Lewis M., Coutouly M., Forsythe I., Tang P., Shrivastava S., Jeroncic K., Stothard P., Amegbey G., Block D., Hau D., Wagner J., Miniaci J., Clements M., Gebremedhin M., Guo N., Zhang Y., Duggan G., Macinnis G., Weljie A., Dowlatabadi R., Bamforth F., Clive D., Greiner R., Marrie T., Sykes B., Vogel H., and Querengesser L. (2007). HMDB: the Human Metabolome Database. Nucleic Acids Res. 35, D521–D526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Karnovsky A., Weymouth T., Hull T., Tarcea V., Scardoni G., Laudanna C., Sartor M., Stringer K., Jagadish H., Burant C., Athey B., and Omenn G. (2012). Metscape 2 bioinformatics tool for the analysis and visualization of metabolomics and gene expression data. Bioinformatics 28, 373–380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. R Core Team. (2013). R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna [Google Scholar]

- 15. Le Cao K.-A., Rohart F., Gonzalez I., and Dejean S. (2016). mixOmics: Omics Data Integration Project. R package version 6.1.1. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=mixOmics (last accessed August8, 2018)

- 16. Rohart F., Eslami A., Matigian N., Bougeard S., and Le Cao K.-A. (2017). MINT: a multivariate integrative method to identify reproducible molecular signatures across independent experiments and platforms. BMC Bioinformatics 18, 128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wilcox R. (2012). Introduction to Robust Estimation and Hypothesis Testing, 3rd ed. Academic Press: Waltham, MA [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pinheiro J., Bates D., DebRoy S., Sarkar D., and R Core Team. (2013). nlme: Linear and Nonlinear Mixed Effects Models. R package version 3.1-137 https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=nime (last accessed August8, 2018)

- 19. Burnham K.P., and Anderson D.R. (2002). Model Selection and Multimodel Inference: A Practical Information-Theoretic Approach, 2nd ed. Springer: New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jeter C., Hergenroeder G., Ward N., Moore A., and Dash P. (2012). Human traumatic brain injury alters circulating L-arginine and its metabolite levels: possible link to cerebral blood flow, extracellular matrix remodeling, and energy status. J. Neurotrauma 29, 119–127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Phang J.M., Liu W., and Zabirnyk O. (2010). Proline metabolism and microenvironmental stress. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 30, 441–463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Morris C.R., Hamilton-Reeves J., Martindale R.G., Sarav M., and Ochoa Gautier J.B. (2017). Acquired amino acid deficiencies: a focus on arginine and glutamine. Nutr. Clin. Pract. 32, 30S-47S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kolodziejczyk J., Saluk-Juszczak J., and Wachowicz B. (2011). In vitro study of the antioxidative properties of the glucose derivatives against oxidation of plasma components. J. Physiol. Biochem. 67, 175–183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rohatgi N., Gudmundsson S., and Rolfsson O. (2015). Kinetic analysis of gluconate phosphorylation by human gluconokinase using isothermal titration calorimetry. FEBS Lett. 589, 3548–3555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Dusick J., Glenn T., Lee W., Vespa P., Kelly D., Lee S., Hovda D., and Martin N. (2007). Increased pentose phosphate pathway flux after clinical traumatic brain injury: a [1,2-13C2]glucose labeling study in humans. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 27, 1593–1602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bartnik B., Sutton R., Fukushima M., Harris N., Hovda D., and Lee S. (2005). Upregulation of pentose phosphate pathway and preservation of tricarboxylic acid cycle flux after experimental brain injury. J. Neurotrauma 22, 1052–1065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Preiser J.-C., van Zanten A., Berger M., Biolo G., Casaer M., Doig G., Griffiths R., Heyland D., Hiesmayr M., Iapichino G., Laviano A., Pichard C., Singer P., Van den Berghe G., Wernerman J., Wischmeyer P., and Vincent J.-L. (2015). Metabolic and nutritional support of critically ill patients: consensus and controversies. Crit. Care 19, 35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wischmeyer P.E., and San-Millan I. (2015). Winning the war against ICU-acquired weakness: new innovations in nutrition and exercise physiology. Crit. Care 19, Suppl. 3, S6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Dash P.K., Hergenroeder G.W., Jeter C.B., Choi H.A., Kobori N., and Moore A.N. (2016). Traumatic brain injury alters methionine metabolism: implications for pathophysiology. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 10, 36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Goodman J., Valadka A., Gopinath S., Uzura M., and Robertson C. (1999). Extracellular lactate and glucose alterations in the brain after head injury measured by microdialysis. Crit. Care Med. 27, 1965–1973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Jeter C., Hergenroeder G., Ward N., Moore A., and Dash P. (2013). Human mild traumatic brain injury decreases circulating branched-chain amino acid and their metabolite levels. J. Neurotrauma 30, 671–679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Jeter C., Hergenroeder G., Ward N., Moore A., and Dash P. (2012). Human Traumatic Brain injury alters circulating L-Arginine and its metabolite levels: possible link to cerebral blood flow, extracellular matrix remodeling, and energy status. J. Neurotrauma 29, 119–127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bell M.J., Robertson C.S., Kochanek P.M., Goodman J.C., Gopinath S.P., Carcillo J.A., Clark R.S., Marion D.W., Mi Z., and Jackson E.K. (2001). Interstitial brain adenosine and xanthine increase during jugular venous oxygen desaturations in humans after traumatic brain injury. Crit. Care Med. 29, 399–404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ivanisevic J., Elias D., Deguchi H., Averell P.M., Kurczy M., Johnson C.H., Tautenhahn R., Zhu Z., Watrous J., Jain M., Griffin J., Patti G.J., and Suiuzdak G. (2015). Arteriovenous blood metabolomics: a readout of intra-tissue metabostasis. Sci. Rep. 5, 12757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]