Abstract

Epithelial barrier maintenance and regulation requires an intact perijunctional actomyosin ring underneath the cell–cell junctions. By searching for known factors affecting the actin cytoskeleton, we identified Krev interaction trapped protein 1 (KRIT1) as a major regulator for epithelial barrier function through multiple mechanisms. KRIT1 is expressed in both small intestinal and colonic epithelium, and KRIT1 knockdown in differentiated Caco-2 intestinal epithelium decreases epithelial barrier function and increases cation selectivity. KRIT1 knockdown abolished Rho-associated protein kinase–induced and myosin II motor inhibitor–induced barrier loss by limiting both small and large molecule permeability but did not affect myosin light chain kinase–induced increases in epithelial barrier function. These data suggest that KRIT1 participates in Rho-associated protein kinase– and myosin II motor–dependent (but not myosin light chain kinase–dependent) epithelial barrier regulation. KRIT1 knockdown exacerbated low-dose TNF-induced barrier loss, along with increased cleaved caspase-3 production. Both events are blocked by pan-caspase inhibition, indicating that KRIT1 regulates TNF-induced barrier loss through limiting epithelial apoptosis. These data indicate that KRIT1 controls epithelial barrier maintenance and regulation through multiple pathways, suggesting that KRIT1 mutation in cerebral cavernous malformation disease may alter epithelial function and affect human health.—Wang, Y., Li, Y., Zou, J., Polster, S. P., Lightle, R., Moore, T., Dimaano, M., He, T.-C., Weber, C. R., Awad, I. A., Shen, L. The cerebral cavernous malformation disease causing gene KRIT1 participates in intestinal epithelial barrier maintenance and regulation.

Keywords: actin cytoskeleton, tight junction, tumor necrosis factor

Throughout the body, epithelia and endothelia form barriers that separate tissue compartments (1–4). Intact barriers are critical to normal tissue function, and barrier disruption can contribute to diseases in multiple organ systems (1–5). Intercellular junctions play an essential role in barrier maintenance by forming connections between individual epithelial and endothelial cells. Previous research has identified multiple contributors to barrier function, including tight junctions and the underlying cytoskeleton (6–12). Tight junctions allow paracellular passage of molecules through at least 2 distinct pathways: the “pore” pathway has high capacity and selectively regulates small molecule permeability (radii: <4 Å), whereas the “leak” pathway has lower capacity and regulates passage of much larger molecules with radii up to at least 65 Å (13–17). Barrier dysfunction can also occur via large-sized, tight junction–independent, nonselective openings related to cell loss or ineffective healing (18–21). However, factors regulating these various pathways of barrier dysfunction remain poorly understood.

Building on the knowledge that an intact perijunctional actomyosin ring is important for epithelial barrier maintenance and regulation, we previously characterized coupling between the perijunctional actomyosin ring and the tight junction, particularly in intestinal epithelial cells (17, 22–24). We reasoned that additional actomyosin regulators could affect intestinal epithelial barrier function. Genes that cause cerebral cavernous malformation (CCM) disease could be such candidates. CCM is a disease of the CNS, characterized by formation of dilated microvessels with a compromised blood–brain barrier (25–27). Most patients with the hereditary form of the disease have loss-of-function mutations of one of the CCM disease–causing genes CCM1/ Krev interaction trapped protein 1 (KRIT1), CCM2, and CCM3/PDCD10 (programmed cell death protein 10) (28–33). Vascular hyperpermeability has been shown in vivo by using dynamic contrast-enhanced quantitative perfusion with MRI in patients with CCM gene mutations. This vascular hyperpermeability occurs even in brain regions far from the malformed vessels, suggesting that CCM gene mutations can affect the blood–brain barrier without causing vessel dilation (26, 27). Knockdown or knockout of these genes in endothelial cells increases RhoA and Rho-associated protein kinase (ROCK) activity, myosin light chain (MLC) phosphorylation, reorganizes perijunctional actin cytoskeleton, and decreases endothelial barrier function (34–36). ROCK inhibition corrects barrier defects in KRIT1-deficient endothelial cells and decreases CCM-like lesion formation in mice with Ccm gene mutations (36–38). These findings show that CCM proteins play a critical role in maintaining vascular endothelial barrier function and prevent pathogenic activation of the RhoA–ROCK–MLC signaling pathway. Furthermore, Krit1 heterozygous knockout increases Apc mutation–induced intestinal tumor formation in mice (39), suggesting that CCM genes could have a functional role in intestinal epithelium. However, it is not clear if KRIT1 can regulate epithelial function other than affecting β-catenin signaling.

The present article reports that KRIT1 is expressed in intestinal epithelium and affects epithelial barrier maintenance and regulation. KRIT1 knockdown decreases intestinal epithelial barrier function and increases selectivity for small cations, eliminates ROCK inhibition– and myosin II motor inhibition–induced barrier loss through a tight junction–dependent pathway, and exacerbates TNF-induced barrier loss through a tight junction–independent mechanism. These findings suggest that KRIT1 is required to maintain normal intestinal epithelial physiology and that loss of KRIT1 function may affect intestinal disease development.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Human and mouse samples

Use of human patient samples was approved by The University of Chicago Institutional Review Board. Mouse studies were performed under a protocol approved by The University of Chicago Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Caco-2 cell culture and treatment of monolayers

Caco-2BBe–derived clones were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 4.5 g/L d-glucose (Corning, Corning, NY, USA), 10% fetal bovine serum (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), and 15 mM HEPES (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and plated on Transwell supports (Corning), as previously described (12, 17, 40, 41). ML-7 (Selleck Chemicals, Houston, TX, USA), Y-27632 (ApexBio, Boston, MA, USA), blebbistatin (ApexBio), and staurosporine (ApexBio) treatment was performed bilaterally in culture medium. Treatment with latrunculin A (Cayman Chemicals, Ann Arbor, MI, USA) and jasplakinolide (Cayman Chemicals) was performed bilaterally in HBSS (23, 42). Before TNF treatment, monolayers were pretreated with interferon-γ (10 ng/ml; PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ, USA) basolaterally for 18–24 h to induce TNF receptor expression, as previously described (40). TNF (5–7.5 ng/ml; PeproTech) was then added to the basolateral media. To inhibit signaling pathways before TNF treatment, IFN-γ–primed monolayers were incubated with bilaterally added SP600125 (ApexBio), SB202190 (Tocris Bioscience, Minneapolis, MN, USA), PD325901 (ApexBio), BIX02189 (Selleck Chemicals), BAY11-7085 (ApexBio), zVAD-fmk (ApexBio), zDEVD-fmk (ApexBio), or zLEHD-fmk (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) for 1 h before basolateral treatment with TNF, along with replenished inhibitors.

KRIT1 knockdown and expression

β-galactosidase (5′-GTGCGTTGCTAGTACCAAC-3′) and KRIT1 (5′-GGTGGAATGTGATGAGATT-3′) targeting sequences and their complementing sequences were synthesized (Integrated DNA Technologies, Skokie, IL, USA), annealed, and individually inserted into the bidirectional small interfering RNA (siRNA)-expressing pSOHU vector containing a blasticidin-resistant cassette (43). These plasmids were stably transfected into SGLT1-expressing Caco-2BBe cells (12). Multiple knockdown and control clones were isolated. To generate inducible enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP)-KRIT1 plasmid, human KRIT1 (44) (a generous gift from Dr. D. Marchuk, Duke University, Durham, NC, USA) sequence was PCR amplified and inserted into a PiggyBac plasmid that contains a Tet-inducible EGFP–fusion protein expression cassette, a Tet3G expression cassette, and a hygromycin-resistant gene expression cassette (17). This plasmid was double-transfected with a PiggyBac transposase-expressing plasmid (System Biosciences, Palo Alto, CA, USA) into KRIT1 knockdown cells, and pooled stable clones were selected by hygromycin treatment of transfected cells.

Determination of barrier function

The current-clamp (Department of Bioengineering, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA, USA) approach was used to measure transepithelial resistance (TER), NaCl dilution potentials, and bi-ionic potentials of methylamine (MA+), ethylamine (EA+), tetramethylammonium (TMA+), tetraethylammonium (TEA+), and N-methyl-d-glucamine (NMDG+) were determined in cultured monolayers, as previously described (12, 17, 41). Permeabilities of Na+ (radius: 0.95 Å), MA+ (radius: 1.89 Å), EA+ (radius: 2.29 Å), TMA+ (radius: 2.75 Å), TEA+ (radius: 3.29 Å), NMDG+ (radius: 3.65 Å), and Cl− were determined by using reversal potentials, known ionic concentrations and activities, and the Goldman-Hodgkin-Katz equation. Absolute Na+ permeability was calculated by using the Kimizuka and Koketsu equation, as previously described (15, 17), allowing us to calculate the permeability of all other ions from their permeabilities relative to Na+. Relative permeabilities of cations to Cl− were also calculated. For staurosporine treatment, TER was measured by using the EVOM system (World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL, USA).

Proliferation assay

Eighty to ninety percent confluent Caco-2 cells from culturing flasks were trypsinized and diluted in complete culture medium. Cell numbers were counted by using a hemocytometer, and 3 × 105 cells were plated into 6-well plates. Individual wells were then trypsinized, diluted in complete culture medium, and then counted by using a hemocytometer in various time points after plating.

Immunoblotting

Monolayers were lysed and scraped from Transwell supports with nonreducing SDS sample buffer supplemented with a protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Thermo Fisher Scientific), subjected to SDS-PAGE (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA), and transferred to PVDF membrane (Bio-Rad), as previously described (17). Western blots were performed by incubating membranes with primary antibodies against KRIT1 (Abcam, Cambridge, United Kingdom), claudin-1 (Thermo Fisher Scientific), claudin-2 (Thermo Fisher Scientific), claudin-4 (Thermo Fisher Scientific), occludin (Thermo Fisher Scientific), zonula occludens (ZO)-1 (Thermo Fisher Scientific), E-cadherin (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA), VE-cadherin (Cell Signaling Technology), glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) (Thermo Fisher Scientific), phosphorylated MLC (Cell Signaling Technology), total MLC (Cell Signaling Technology), phosphorylated p42/44 ERK (Cell Signaling Technology), phosphorylated p38 (Cell Signaling Technology), phosphorylated JNK (Cell Signaling Technology), and bcl-2 (Cell Signaling Technology) followed by horseradish peroxidase–conjugated secondary antibodies (Cell Signaling Technology), as described elsewhere (17, 41). Protein was detected by chemiluminescence and imaged by using a Syngene PXi system (Syngene, Cambridge, United Kingdom). Densitometry was performed by using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA). For quantification, densitometry values were first normalized to GAPDH and E-cadherin and then to control monolayers.

Immunohistochemical staining, immunofluorescence staining, and microscopy

For immunohistochemical staining, human small intestinal and colon mucosal biopsy samples (with institutional review board approval) were deparaffinized, antigen retrieved, and stained with a polyclonal anti-KRIT1 antibody (MilliporeSigma, Burlington, MA, USA) followed by 3,3′-diaminobenzidine staining. Images were taken by using an upright diagnostic microscope (Leica Microsystems, Buffalo Grove, IL, USA) with an Axiocam colored digital camera (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging, Jena, Germany).

For immunofluorescent staining, monolayers were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde in PBS (23, 45). After blocking in 3% BSA and 0.05% saponin containing PBS, monolayers were incubated with anti–claudin-1, claudin-2, claudin-4, occludin, and ZO-1 antibodies (all Thermo Fisher Scientific), followed by species-specific donkey secondary antibody conjugated to DyLight 488 or DyLight 594 (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA, USA) along with Alexa Fluor 488 or 647 conjugated phalloidin to label F-actin (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and Hoechst 33342 to label nuclei (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and mounted in ProLong Gold (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Images were collected by using an automated inverted widefield epifluorescence microscope (Axiovert 200 M, with ×63 1.4 numerical aperture oil immersion objective; Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) with an ORCA-ER camera (Hamamatsu Photonics, Hamamatsu, Japan) driven by SlideBook (Intelligent Imaging Innovations, Denver, CO, USA). Z stacks were collected at 0.25-μm intervals and deconvolved within SlideBook. Images were then exported and processed in MetaMorph (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) for x-y and x-z presentations. To quantify apical membrane bulging, the z-distance between the top of the apical membrane, defined by apical F-actin staining, and the plane of tight junction, defined by ZO-1 staining, were measured in MetaMorph.

RNA isolation and quantitative RT-PCR

For RNA isolation, epithelial monolayers and three-dimensional cultured normal intestinal epithelial cells were first washed in PBS and then lysed in Trizol reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific). RNA was isolated according to the manufacturer’s protocol, digested with RNase free DNase I (Qiagen, Germantown, MD, USA), and purified by using RNeasy minicolumns (Qiagen). RNA concentration was determined by using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific), reverse transcribed (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA), and subjected to quantitative RT-PCR (Bio-Rad) using the following primers. Human GAPDH: forward 5′-CTTCACCACCATGGAGAAGGC-3′, reverse 5′-GGCATGGACTGTGGTCATGAG-3′; human E-cadherin (CDH1): forward 5′-ACCACCTCCACAGCCACCGT-3′, reverse 5′-GCCCACGCCAAAGTCCTCGG-3′; human KRIT1: forward 5′-TCCTAAACCACCCAGAAACGG-3′, reverse 5′-CAACAGAACGATATGACCCATCC-3′; human VE-cadherin (CDH5): forward; 5′-TTGGAACCAGATGCACATTGAT-3′, reverse 5′-TCTTGCGACTCACGCTTGAC-3′.

RT-PCR was performed by using SsoFast EvaGreen reagent (Bio-Rad) on a CFX96 instrument (Bio-Rad).

Statistical analysis

All data are presented as means ± sem unless otherwise specified. For comparison between 2 groups, Student’s t test was used to compare means. For comparison of multiple groups of samples, 1-way ANOVA analysis with a Tukey post hoc test was used. Paired or unpaired tests were used when appropriate. Statistical analyses were performed by using Excel (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA, USA) or GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA).

RESULTS

Expression of KRIT1 in intestinal epithelium

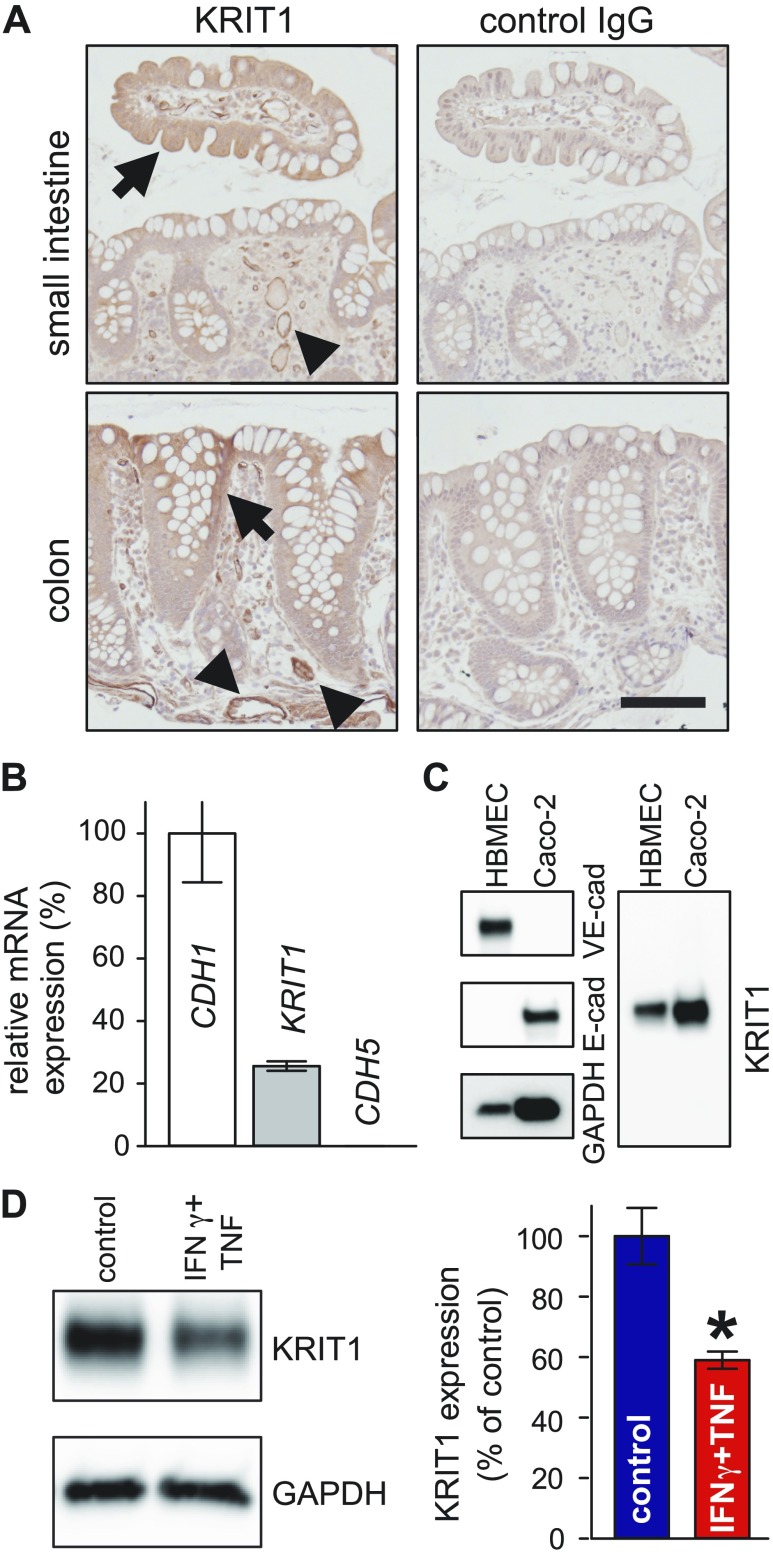

To determine if KRIT1 can have a functional role in intestinal epithelium, we first assessed its expression in the small intestine and colon. Immunohistochemical staining revealed that KRIT1 is diffusely expressed in both small intestinal and colonic epithelium (Fig. 1A). Quantitative RT-PCR using RNA from colonic spheroids derived from human subjects also showed that KRIT1 mRNA is expressed in intestinal epithelium (Fig. 1B), whereas VE-cadherin (CDH5), a gene known not to be expressed in intestinal epithelium, could not be detected. Western blots revealed that Caco-2 colonic epithelial cells express a single band of KRIT1, similar to KRIT1 expressed in human brain microvascular endothelial cells, indicating that KRIT1 is expressed in model intestinal epithelium (Fig. 1C). Similarly, protein and RNA analyses showed that KRIT1 is also expressed in mouse intestinal epithelium (Supplemental Fig. 1). Next, we tested if KRIT1 expression can be regulated by proinflammatory stimuli. Combined treatment of Caco-2 monolayers with proinflammatory cytokines IFN-γ and TNF reduced KRIT1 protein abundance (Fig. 1D). Taken together, KRIT1 is expressed in intestinal epithelium, and its expression can be regulated.

Figure 1 .

KRIT1 is expressed in intestinal epithelium. A) Immunohistochemical staining shows KRIT1 expression in small intestinal and colonic epithelium. Scale bar, 100 μm. Arrows: KRIT1 expression in epithelium. Arrowheads: KRIT1 expression in endothelium. B) Quantitative RT-PCR shows that KRIT1 mRNA is expressed in human colonic epithelial spheroids. CDH1 (E-cadherin) and CDH5 (VE-cadherin) are used as positive and negative controls for epithelial gene expression, respectively. C) Western blot show that KRIT1 is expressed in Caco-2 intestinal epithelial cells. Human brain microvascular endothelial cell (HBMEC) lysate was included as positive control for KRIT1. D) Western blot and quantification show that combined treatment of IFN-γ and TNF decreases KRIT1 protein abundance; n = 3 for each condition. *P ≤ 0.05.

KRIT1 is required for proper epithelial barrier maintenance

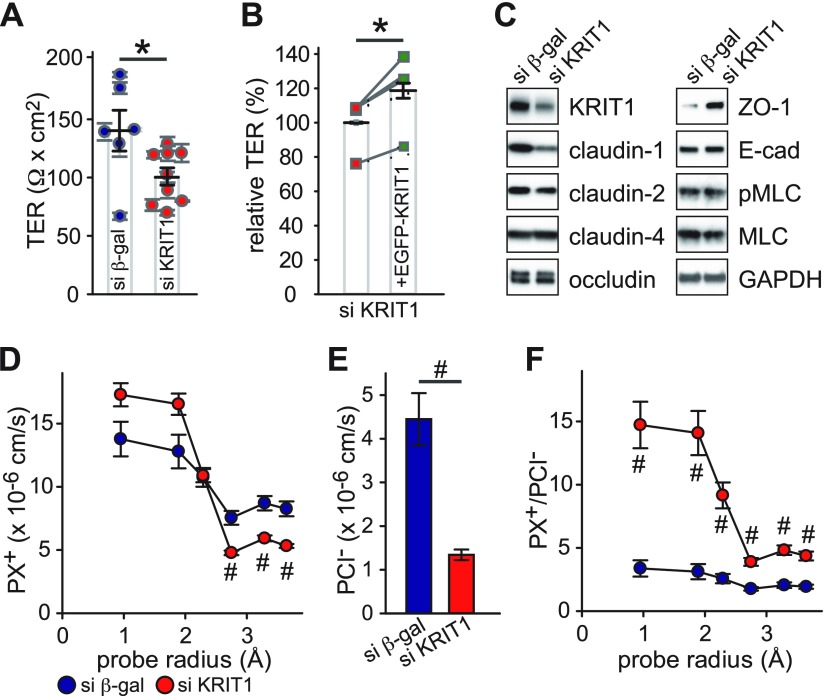

Having determined that KRIT1 is expressed in intestinal epithelium, and its expression can be decreased by proinflammatory cytokines, our goal was to understand how KRIT1 down-regulation may affect epithelial barrier function. Stable KRIT1 knockdown Caco-2BBe cell clones were generated by transfecting a KRIT1 targeting siRNA expressing plasmid. Caco-2BBe cell clones stably expressing anti–β-galactosidase siRNA were developed as control. Because KRIT1 loss compromises the vascular endothelial barrier, we tested KRIT1 knockdown’s effect on epithelial barrier function. Analysis of multiple independent clones revealed that KRIT1 knockdown monolayers have significantly lower TER, an electrophysiological measure of epithelial barrier function, relative to control monolayers (Fig. 2A); this finding suggests that KRIT1 knockdown compromises the epithelial barrier. This action was not accompanied by a change in the proliferation rate of KRIT1 knockdown cells (Supplemental Fig. 3). Expression of EGFP-KRIT1 fusion protein in KRIT1 knockdown monolayers increased TER (Fig. 2B), indicating that the effect of anti-KRIT1 siRNA on the epithelial barrier is specific.

Figure 2 .

KRIT1 knockdown decreases intestinal epithelial barrier function and affects ion permeability. A) TER of multiple control [si β-galactosidase (β-gal), 6 clones; blue circles] and KRIT1 knockdown (si KRIT1, 9 clones; red circles) clones. B) Relative TER of KRIT1 knockdown cells stably transfected with Tet-inducible EGFP-KRIT1 plasmid with (green squares) or without (red squares) doxycycline-induced EGFP-KRIT1 expression. Data from 3 independent experiments are shown. Data points from the same individual experiments are connected by gray lines. C) Western blot analysis of apical junctional complex–related protein expression. D–F) Bi-ionic potential measurements of monovalent cations and Cl− in control (2 clones, each with 2 independent experiments; blue circles) and KRIT1 knockdown clones (4 clones, each with 2 independent experiments; red circles). Absolute permeability of different-sized monovalent cations (D) Absolute permeability of Cl− (E) Relative permeability of monovalent cations to Cl− (F). *P ≤ 0.05, #P ≤ 0.01.

Because the tight junction is a major determinant of epithelial barrier function in intact epithelium, we tested if KRIT1 knockdown–caused epithelial barrier loss in Caco-2 monolayers is associated with altered tight junction protein expression. KRIT1 knockdown decreased claudin-1 (but not claudin-2 or claudin-4) expression, suggesting that KRIT1 regulates expression of selective members of the claudin family (Fig. 2C). KRIT1 knockdown increased ZO-1, but did not affect occludin, expression. Furthermore, the increased MLC phosphorylation reported in KRIT1 knockdown endothelial cells (35, 36) was not observed in KRIT1 knockdown Caco-2 epithelial monolayers. Immunofluorescent staining revealed decreased claudin-1 and increased ZO-1 intensity at apical cell–cell contact but no change in tight junction protein localization in KRIT1 knockdown monolayers (Supplemental Fig. 2A). In contrast to reported actin reorganization in KRIT1 knockdown endothelial cells (35, 36), actin cytoskeleton reorganization was not observed in the apical or basal region of KRIT1 knockdown Caco-2 cells (Supplemental Fig. 2B).

To define the mechanisms of KRIT1 knockdown–induced barrier dysfunction in more detail, we measured size- and charge-selectivity of KRIT1 knockdown monolayers. Bi-ionic potential measurements revealed that KRIT1 knockdown slightly increased small cation permeability (Na+ and MA+), decreased large cation permeability (TMA+, TEA+, and NMDG+) (Fig. 2D and Supplemental Fig. 4A), and decreased Cl− permeability (Fig. 2E and Supplemental Fig. 4B). The overall effect was increased relative permeability of both small and large cations to Cl−, with a more drastic increase in small cation permeability (Fig. 2F and Supplemental Fig. 4C).

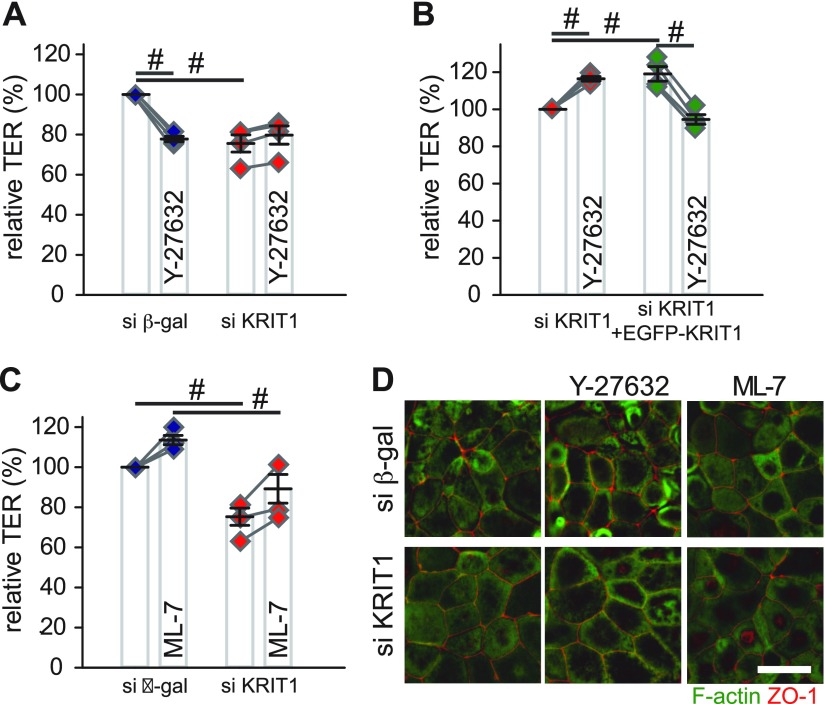

KRIT1 is required for ROCK-dependent barrier maintenance

Studies in endothelial cells suggest that loss of KRIT1 expression promotes ROCK activation, cytoskeleton reorganization, and loss of endothelial barrier function (35, 36). Although our Western blots of phosphorylated MLC and fluorescent microscopy of F-actin do not support the idea, they do not exclude the possibility that loss of KRIT1 affects epithelial barrier function through increasing Rho kinase activity. To test this theory, control and KRIT1 knockdown monolayers were treated with Y-27632, a ROCK inhibitor. Similar to previous studies on intestinal epithelial cells (46), ROCK inhibition decreased TER in control monolayers (Fig. 3A). However, no TER decrease was observed in Y-27632–treated KRIT1 knockdown monolayers (Fig. 3A and Supplemental Fig. 5A). Such loss of ROCK inhibition–induced barrier dysfunction in KRIT1 knockdown monolayers can be rescued by EGFP-KRIT1 expression (Fig. 3B and Supplemental Fig. 5B). In contrast, inhibiting myosin light chain kinase (MLCK), another regulator for MLC phosphorylation (12), equally increased TER in control and KRIT1 knockdown monolayers (Fig. 3C and Supplemental Fig. 5C), indicating that KRIT1 selectively affects ROCK-dependent epithelial barrier regulation. Y-27632 or ML-7–treated control and KRIT1 knockdown monolayers all had modest apical bulging, consistent with equivalent actomyosin ring relaxation in control and KRIT1 knockdown monolayers (Fig. 3D) (47).

Figure 3 .

KRIT1 controls ROCK-dependent, but not MLCK-dependent, intestinal epithelial barrier regulation. A) Relative TER of ROCK inhibitor Y-27632 (20 μM) treated control (blue diamonds) and KRIT1 knockdown (red diamonds) monolayers. Pooled results of 4 independent experiments are shown. Data points from the same individual experiments are connected by gray lines. B) Relative TER of Y-27632–treated (20 μM) KRIT1 knockdown monolayers stably transfected with Tet-inducible EGFP-KRIT1 plasmid with (green diamonds) or without (red diamonds) doxycycline-induced EGFP-KRIT1 expression. Results of 4 independent experiments are shown. Data points from the same individual experiments are connected by gray lines. C) Relative TER of MLCK inhibitor ML-7–treated (20 μM) control (blue diamonds) and KRIT1 knockdown (red diamonds) monolayers. Results of 4 independent experiments are shown. Data points from the same individual experiments are connected by gray lines. D) Immunofluorescent microscopy of apical F-actin (green) and ZO-1 (red) in control and KRIT1 knockdown monolayers. Scale bar, 10 μm. β-gal, β-galactosidase. #P ≤ 0.01.

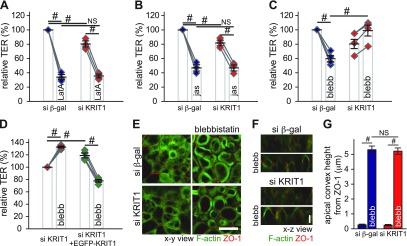

KRIT1 is required for myosin II motor–dependent barrier maintenance

The aforementioned experiments did not define at which level ROCK-dependent barrier maintenance is affected by KRIT1. ROCK can regulate epithelial barrier by modulating the perijunctional actomyosin ring through effects on MLC phosphorylation, which in turn increase myosin II motor activity (48, 49). Thus, we sought to understand the contribution of actomyosin components in ROCK inhibition–induced, and KRIT1-dependent, epithelial barrier regulation. The monomeric actin–binding compound latrunculin A and actin polymerization inducer jasplakinolide both decreased epithelial barrier function efficiently in control and KRIT1 knockdown monolayers (Fig. 4A, B), indicating that KRIT1 does not control actin disruption-induced barrier regulation (22, 23, 42). Similar to the effect of ROCK inhibition, inactivating the myosin II motor, a downstream effector of ROCK, by blebbistatin (50, 51) decreased TER in control monolayers. However, such inhibition failed to decrease TER in KRIT1 knockdown Caco-2 monolayers (Fig. 4C and Supplemental Fig. 5D), which can be rescued by EGFP-KRIT1 expression (Fig. 4D and Supplemental Fig. 5E). In contrast to TER change, blebbistatin caused similar bulging of the apical membrane in control and KRIT1 knockdown monolayers (Fig. 4E–G). This finding indicates that KRIT1 does not affect myosin II motor inhibition–induced apical actin reorganization and cell shape change in Caco-2 monolayers (47). Thus, KRIT1 selectively modulates ROCK-dependent epithelial barrier maintenance through affecting events downstream of myosin II motor activity.

Figure 4 .

KRIT1 is required for myosin II contraction–induced epithelial barrier regulation. A) TER of the monomeric actin–binding drug latrunculin A (LatA; 0.5 μM) treated control (blue diamonds) and KRIT1 knockdown monolayers (red diamonds). Results of 3 independent experiments are shown. Data points from the same individual experiments are connected by gray lines. B) TER of actin polymerization inducer jasplakinolide (jas; 2 μM) treated control (blue diamonds) and KRIT1 knockdown monolayers. Results of 3 independent experiments are shown. Data points from the same individual experiments are connected by gray lines. C) TER of myosin II motor inhibitor blebbistatin (blebb; 50 μM) treated control (blue diamonds) and KRIT1 knockdown (red diamonds) monolayers. Results of 4 independent experiments are shown. Data points from the same individual experiments are connected by gray lines. D) Relative TER of blebbistatin (blebb; 50 μM) treated KRIT1 knockdown monolayers stably transfected with Tet-inducible EGFP-KRIT1 plasmid with (green diamonds) or without (red diamonds) doxycycline-induced EGFP-KRIT1 expression. Results of 4 independent experiments are shown. Data points from the same individual experiments are connect by gray lines. E, F) Immunofluorescent microscopy of apical F-actin (green) and ZO-1 (red) in control and KRIT1 knockdown monolayers. X-y presentation. Scale bar, 10 μm (E). X-z presentation. Scale bar, 5 μm (F). G) Quantification of distance between the tip of the apical actin cytoskeleton and the plane of the tight junction, as marked by ZO-1. Sixty cells from multiple fields were measured for each condition. β-gal, β-galactosidase; NS, not significant (P > 0.05). #P ≤ 0.01.

KRIT1 affects ROCK/myosin II motor–dependent regulation of small and large ion permeability

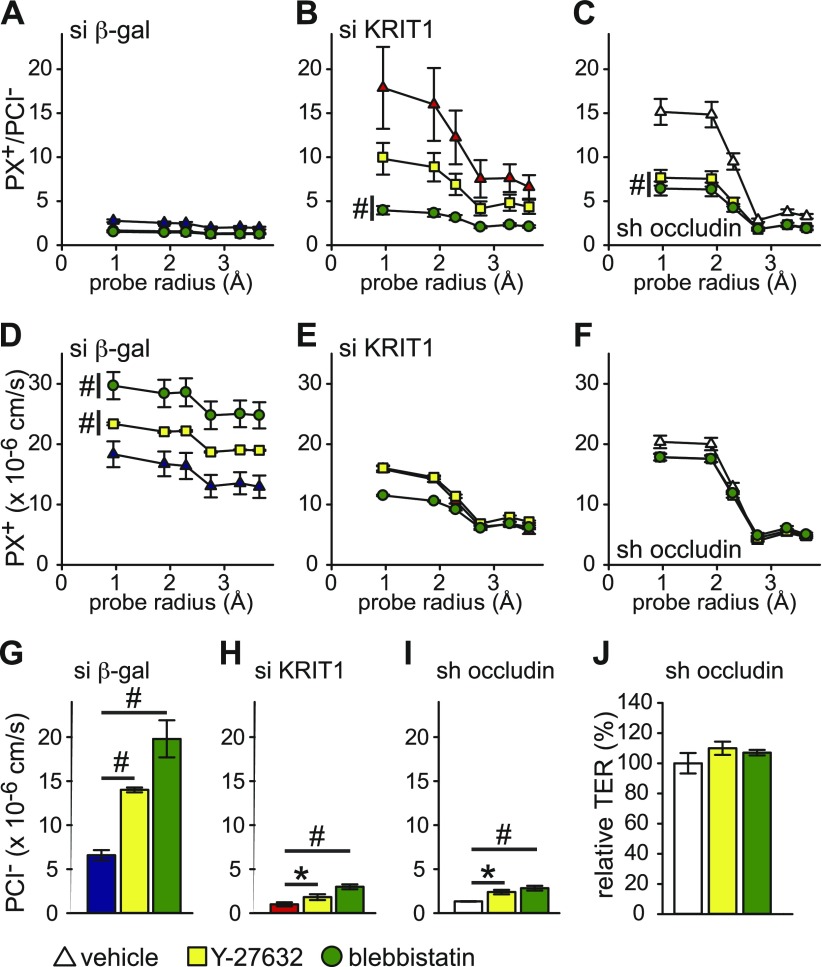

The preceding data suggest that KRIT1 affects the ROCK/myosin II motor pathway of barrier maintenance. We next tested if KRIT1 affects this pathway in a size- and charge-selective manner. In control monolayers, Y-27632 and blebbistatin increased the permeability of small and large cations in a near size nonselective manner, along with increased permeability to Cl−, indicating that ROCK and myosin II motor control a charge- and size-nonselective pathway of barrier regulation (Fig. 5A, D, G and Supplemental Fig. 6A, D, G). In KRIT1 knockdown monolayers, although permeability to cations remained largely unchanged, Cl− permeability still increased significantly, similar to the changes in control monolayers, despite decreased baseline permeability to Cl− (Fig. 5E, H and Supplemental Fig. 6E, H). This action decreased relative permeability of cations to Cl− (Fig. 5B and Supplemental Fig. 6B). Because the transmembrane tight junction protein occludin maintains epithelial barrier and limits tight junction leak pathway permeability (17), we measured Y-27632- and blebbistatin–induced size- and charge-selective permeability change in occludin knockdown monolayers. The KRIT1 knockdown-driven permeability change was similar to what was observed in occludin knockdown monolayers (Fig. 5C, F, I and Supplemental Fig. 6C, F, I), and occludin knockdown monolayers also failed to decrease TER after ROCK or myosin II motor inhibition (Fig. 5J). These data indicate that both KRIT1 and occludin are required for ROCK-dependent and myosin II motor–dependent barrier regulation and that KRIT1 selectively participates in the ROCK/myosin II motor pathway–regulated cation, but not anion, permeability.

Figure 5 .

ROCK/myosin II motor–dependent regulation of tight junction leak pathway requires KRIT1 and occludin. A–C) Relative permeability of different-sized cations to Cl− of Y-27632 (20 μM; yellow squares) or blebbistatin (50 μM; green circles) treated control (A; blue triangles), KRIT1 knockdown (B; red triangles), and occludin knockdown (C; white triangles) monolayers. D–F) Absolute permeability of different-sized cations of Y-27632 (20 μM; yellow squares) or blebbistatin (50 μM; green circles) treated control (D; blue triangles), KRIT1 knockdown (E; red triangles), and occludin knockdown (F; white triangles) monolayers. G–I) Absolute permeability of Cl− n Y-27632 (20 μM; yellow bars) or blebbistatin (50 μM; green bars) treated control (G; blue bar), KRIT1 knockdown (H; red bar), and occludin knockdown (I; white bar) monolayers. J) Relative TER of Y-27632 (20 μM; yellow bar) or blebbistatin (50 μM; green bar) treated occludin knockdown monolayers (white bar). Quadruplicate samples for each condition were analyzed in A–J. β-gal, β-galactosidase. *P ≤ 0.05, #P ≤ 0.01.

KRIT1 loss exacerbates TNF-induced epithelial barrier dysfunction and apoptosis

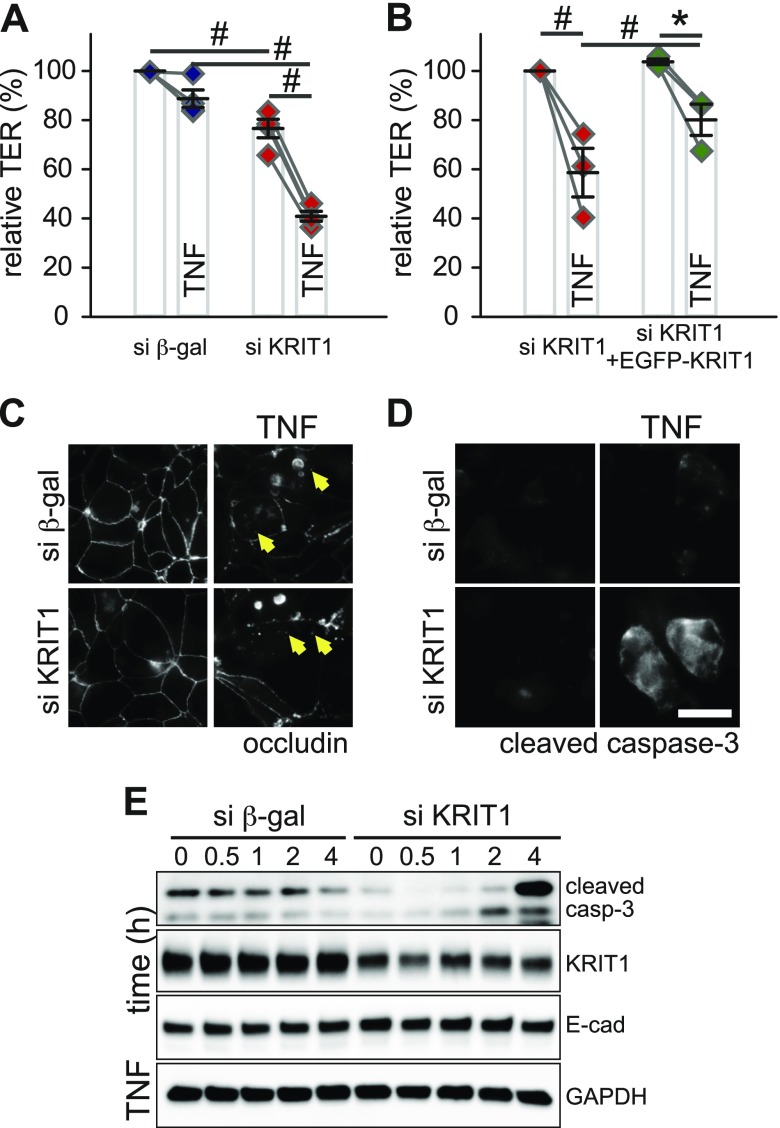

The proinflammatory cytokine TNF decreases intestinal epithelial barrier function and increases leak pathway permeability through an MLCK-dependent pathway (17, 40). Our aforementioned data show that KRIT1 participates in myosin-dependent epithelial barrier regulation, suggesting a potential role for KRIT1 in TNF-induced barrier regulation. To test this possibility, we treated control and KRIT1 knockdown monolayers with TNF. Although this treatment caused a significant TER decrease in control and KRIT1 knockdown monolayers, TER loss was more pronounced in KRIT1 knockdown monolayers (Fig. 6A and Supplemental Fig. 7A). This phenotype can be reversed by EGFP-KRIT1expression in KRIT1 knockdown monolayers (Fig. 6B and Supplemental Fig. 7B). These data suggest that KRIT1 knockdown exacerbates TNF-induced barrier dysfunction. Occludin internalization, which is often associated with TNF-induced tight junction regulation (17, 52, 53), was similar in both control and KRIT1 knockdown monolayers (Fig. 6C). Because TNF can also affect epithelial barrier function through inducing apoptosis (54), we next measured TNF-induced apoptosis in KRIT1 knockdown monolayers. TNF-treated KRIT1 knockdown monolayers had an increased number of cleaved caspase-3–positive cells (Fig. 6D). Consistent with this finding, TNF treatment caused more pronounced accumulation of cleaved caspase-3 in KRIT1 knockdown monolayers relative to control monolayers (Fig. 6E and Supplemental Fig. 7C, D), indicating that TNF induces more severe apoptosis in KRIT1 knockdown monolayers. This effect is not caused by a general increase in apoptosis sensitivity in KRIT1 knockdown monolayers, as a widely used apoptosis inducer (i.e., the pan-protein kinase inhibitor staurosporine) did not cause more severe epithelial barrier loss in KRIT1 knockdown monolayers (Supplemental Fig. 8). These data suggest that KRIT1 knockdown selectively enhances TNF-induced barrier loss and apoptosis.

Figure 6 .

KRIT1 limits TNF-induced epithelial barrier loss. A) Relative TER of TNF-treated (7.5 ng/ml) control (blue diamonds) and KRIT1 knockdown (red diamonds) monolayers. All monolayers were pretreated with IFN-γ for 16–24 h to induce TNF receptor expression. Pooled results of 4 independent experiments are shown. Data points from the same individual experiments are connected by gray lines. B) Relative TER of TNF-treated KRIT1 knockdown cells stably transfected with Tet-inducible EGFP-KRIT1 plasmid with (green diamonds) or without (red diamonds) doxycycline-induced EGFP-KRIT1 expression. All monolayers were pretreated with IFN-γ for 16–24 h to induce TNF receptor expression. Results of 3 independent experiments are shown. Data points from the same individual experiments are connected by gray lines. C, D) Immunofluorescent microscopy of occludin (C) and cleaved caspase-3 (D) in control and KRIT1 knockdown monolayers. Arrows show internalized occludin containing vesicles. Scale bar, 10 μm. E) Western blot analysis of cleaved caspase-3 in TNF-treated control and KRIT1 knockdown monolayers. Blots for GAPDH and E-cadherin are included as loading control. β-gal, β-galactosidase. *P ≤ 0.05, #P ≤ 0.01.

KRIT1 knockdown enhances TNF-induced apoptosis to exacerbate epithelial barrier dysfunction

We next examined how KRIT1 knockdown may enhance TNF-induced barrier loss by testing the contribution of TNF-activated signaling pathways. Pharmacologic inhibition of JNK (SP600125), p38 (SB202190), ERK1/2 (PD0325901), ERK5 (BIX02189), or NFκB (BAY 11–7085) pathways all failed to limit the exacerbated TNF-induced barrier loss in KRIT1 knockdown monolayers (Supplemental Fig. 9A–C), indicating these pathways are not critical mediators of this effect. Furthermore, Western blot showed that there was no exacerbated production of phosphorylated p38, JNK, or ERK after TNF treatment in KRIT1 knockdown monolayers relative to control monolayers, particularly in early time points (Supplemental Fig. 9D).

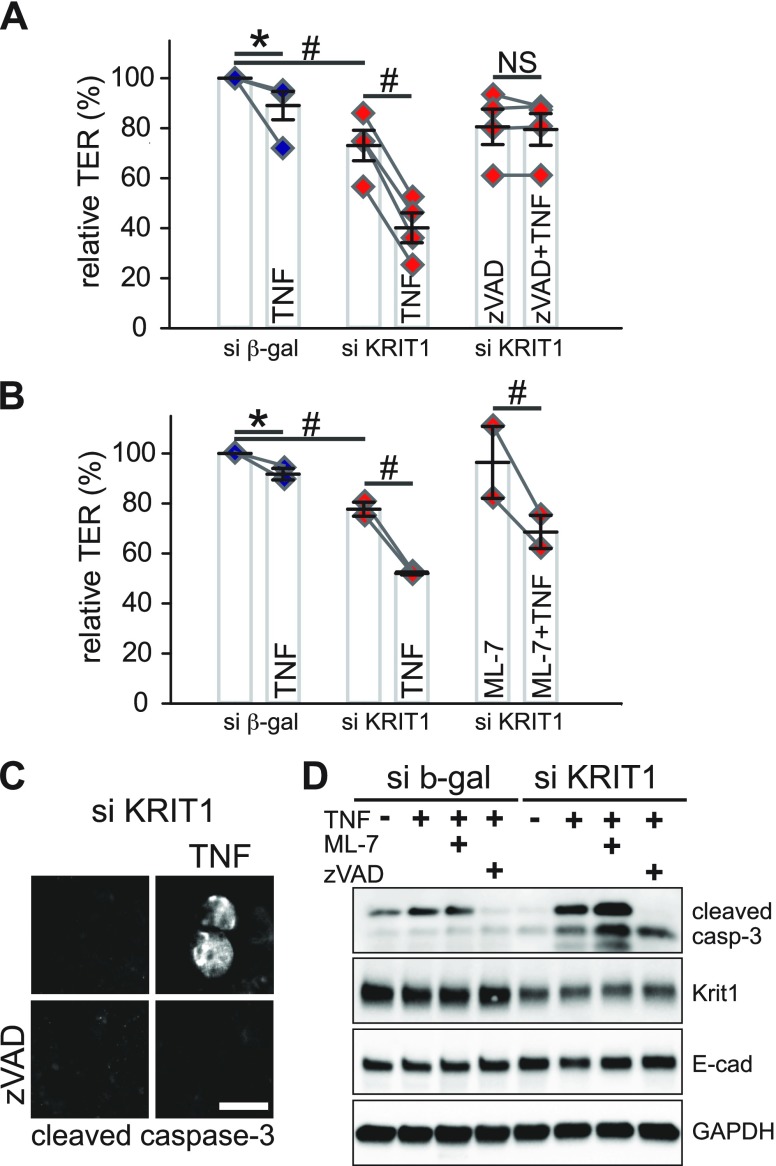

It is known that TNF can regulate intestinal epithelial barrier through the following: 1) MLCK-mediated MLC phosphorylation and perijunctional actomyosin ring contraction; and 2) apoptosis-induced cell loss (19, 40, 54–56). We therefore dissected contributions of these pathways. Although the MLCK inhibitor ML-7 failed to inhibit TNF-induced barrier loss in KRIT1 knockdown monolayers, the pan-caspase inhibitor zVAD-fmk completely blocked TNF-induced barrier loss in KRIT1 knockdown monolayers (Fig. 7A, B and Supplemental Fig. 10A, B). This action is associated with a decreased number of cleaved caspase-3–positive cells and TNF-induced appearance of cleaved caspase-3 in zVAD-fmk–treated KRIT1 knockdown monolayers (Fig. 7C, D). These data suggest that KRIT1 limits TNF-induced barrier dysfunction by controlling apoptosis. This process requires more than a single caspase, as inhibition of caspase-3/-7 or caspase-9 alone failed to inhibit TNF-induced barrier defects in KRIT1 knockdown monolayers (Supplemental Fig. 10C). Western blots also suggest that altered antiapoptotic protein bcl-2 expression is not a major driving force for TNF-induced apoptosis in KRIT1 knockdown monolayers (Supplemental Fig. 9D).

Figure 7 .

KRIT1 loss exacerbates TNF-induced barrier dysfunction through enhancing apoptosis. A, B) Relative TER of TNF-treated (7.5 ng/ml) monolayers in the presence of pan-caspase inhibitor zVAD-fmk (A; 50 μM, 4 independent experiments) or MLCK inhibitor ML-7 (B; 20 μM, 2 independent experiments). All monolayers were pretreated with IFN-γ for 16–24 h to induce TNF receptor expression. Data points from the same individual experiments are connected by gray lines. C) Immunofluorescent microscopy of cleaved caspase-3 in KRIT1 knockdown monolayers with or without zVAD-fmk treatment. Scale bar, 10 μm. D) Western blot of cleaved caspase-3 in TNF-treated control and knockdown monolayers treated with ML-7 or zVAD-fmk. GAPDH and E-cadherin blots are included as loading control. β-gal, β-galactosidase; NS, not significant (P > 0.05). *P ≤ 0.05, #P ≤ 0.01.

DISCUSSION

Our experiments identify a role for KRIT1 in the regulation of intestinal epithelial barrier function. KRIT1 is expressed in the intestinal epithelium (Fig. 1) and affects the epithelial barrier in multiple ways. Our study using KRIT1 knockdown intestinal epithelial cells showed that loss of KRIT1 does the following: 1) increases tight junction permeability (Fig. 2); 2) eliminates myosin relaxation–induced intestinal barrier loss by failing to open the tight junction leak pathway for cations (Figs. 3–5); and 3) increases TNF-induced apoptosis and tight junction–independent barrier loss (Figs. 6 and 7).

Our data show that KRIT1 knockdown increases the relative permeability of small cations, including Na+ and MA+, to Cl−. In contrast, relative permeability of large cations to Cl−, including TMA+, TEA+, and NMDG+, increased to a lesser degree (Fig. 2 and Supplemental Fig. 4). This action is accompanied by decreased Cl− permeability, decreased permeability of large cations, and marginally increased small cation permeability. These changes are associated with decreased expression of claudin-1 and increased expression of ZO-1 in KRIT1 knockdown monolayers (Fig. 2C and Supplemental Fig. 2A). These protein expression changes are consistent with TER and ion permeability changes, as it is known that claudin-1 elevates TER and that ZO-1 limits large molecule permeability (16, 57, 58). This is not likely related to epithelial cell proliferation, as both control and KRIT1 knockdown cells proliferate similarly (Supplemental Fig. 3).

Our experiments further show that KRIT1 participates in myosin II–mediated barrier regulation. In intestinal epithelium, both ROCK inhibition and myosin II motor inhibition decrease epithelial barrier function and increase permeability to small and large cations and the anion Cl−, suggesting that ROCK/myosin II motor–mediated tension at the perijunctional actomyosin ring maintains the epithelial barrier through limiting leak pathway permeability (Figs. 3–5 and Supplemental Figs. 4–6). KRIT1 knockdown is able to eliminate both ROCK inhibition–induced and myosin II motor inhibition–induced barrier loss and increases in cation permeability but not able to affect ROCK inhibition– and myosin II motor inhibition–induced Cl− permeability increases. This appears to be specific, as neither myosin II motor inhibition–induced myosin heavy chain IIA and IIB accumulation at the apical cell–cell contact site (data not shown) nor myosin II motor inhibition–induced apical membrane bulging (Fig. 4) is affected by KRIT1 knockdown. This suggests that KRIT1 affects the ROCK/myosin II motor pathway of barrier regulation at a level downstream of myosin II motor activity. Because the perijunctional actomyosin ring can directly couple with the ZO family of tight junction proteins ZO-1, -2, -3, and occludin (16, 59, 60), and occludin knockdown also failed to decrease barrier function and increase cation permeability after ROCK or myosin II motor inhibition (Fig. 5), it is likely that KRIT1 affects the ROCK/myosin II motor pathway of barrier regulation at a level downstream of myosin II motor activity and upstream of the function of transmembrane tight junction proteins. However, the exact site for KRIT1 to affect ROCK/myosin II motor–dependent barrier regulation must be defined in future studies.

Our study found that although ROCK or myosin II motor inhibition failed to increase cation permeability in KRIT1 knockdown monolayers, MLCK inhibition was able to increase epithelial barrier function in both control and KRIT1 knockdown monolayers (Figs. 3–5 and Supplemental Figs. 4–6). This finding seems to be contradictory to the knowledge that ROCK and MLCK can both increase MLC phosphorylation, which implies that ROCK and MLCK inhibition should exert similar effects on epithelial barrier function. However, increasing evidence suggests that MLCK and ROCK have different effects on actomyosin-associated epithelial function. During Ca2+ depletion–induced apical junctional complex disassembly, both ROCK inhibition by Y-27632 and myosin II motor inhibition by blebbistatin can limit the process, whereas MLCK inhibition by ML-7 cannot do so in intestinal epithelium (50, 61). During recovery from ATP depletion, ROCK inhibition was able to limit increased MLC phosphorylation, whereas MLCK inhibition failed to do so in model renal epithelium (62). Furthermore, inhibiting ROCK or myosin II motor, but not MLCK, can enhance lumen formation in three-dimensional cultured epithelial cells (63). One of our previous studies using intestinal epithelium also found that although myosin II motor inhibition decreases the mobility of both EGFP–ZO-1 and EGFP–β-actin at apical junctions, as assessed by fluorescent recovery after photobleaching experiments, MLCK inhibition does not affect the mobile fraction of EGFP–ZO-1 or EGFP–β-actin (22). The current study data show that ROCK inhibition and myosin II motor inhibition both increase leak pathway permeability (Fig. 5A, D, G and Supplemental Fig. 6A, D, G), whereas MLCK inhibition selectively decreases pore pathway permeability (data not shown). Our current findings that ROCK and myosin II motor require KRIT1 to regulate epithelial barrier function while MLCK regulates epithelial barrier in a KRIT1-independent manner further enhance the view that the ROCK and myosin II motor–dependent barrier regulation pathway is distinct from the MLCK-dependent pathway, despite the fact that they all affect actomyosin function (Figs. 3–5 and Supplemental Figs. 4–6).

KRIT1 affects TNF-induced barrier regulation in a different fashion. Although low-dose TNF can decrease epithelial barrier function through activating MLCK-mediated tight junction regulation (40, 55), MLCK inhibition cannot prevent TNF-induced barrier loss in KRIT1 knockdown cells (Fig. 7 and Supplemental Fig. 10). Inhibitor studies also show that JNK, ERK1/2, p38, ERK5 MAP kinases and NFκB activation are likely not driving forces for KRIT1 knockdown to affect TNF-induced barrier loss (Supplemental Fig. 9). Western blot and immunofluorescent staining both showed that TNF-treated KRIT1 knockdown monolayers have increased cleaved caspase-3 relative to TNF-treated control monolayers, suggesting that KRIT1 knockdown increases sensitivity to TNF-induced apoptosis in intestinal epithelial cells (Fig. 6 and Supplemental Fig. 7). Electrophysiologic studies further show that pan-caspase inhibition completely prevented TNF-induced barrier loss in KRIT1 knockdown monolayers (Fig. 7 and Supplemental Fig.10). These data suggest that KRIT1 regulates TNF-induced barrier loss by affecting apoptosis. In contrast to pan-caspase inhibitors, inhibitors of individual caspases, including caspase-3, -7, -8, and -9 (Supplemental Fig. 10), failed to prevent TNF-induced excessive barrier loss in KRIT1 knockdown monolayers. This outcome indicates that TNF is able to induce excessive barrier loss through alternative caspase-activating pathways in KRIT1 knockdown monolayers. In contrast to TNF, apoptosis induced by staurosporine does not cause more severe epithelial barrier loss in KRIT1 knockdown monolayers (Supplemental Fig. 8), indicating that KRIT1 does not globally affect apoptosis sensitivity. These studies excluded multiple mechanisms for KRIT1 to regulate TNF-induced apoptosis but did not define the exact point that KRIT1 intersects with TNF-induced signaling to affect apoptosis and barrier function. This topic warrants additional investigation in the future.

Although our experiments found that KRIT1 can regulate the intestinal epithelial barrier and previous studies showed that KRIT1 affects the endothelial barrier (27, 35, 36, 64, 65), some major differences exist between these cell types. In endothelial cells, KRIT1 knockdown increases MLC phosphorylation, disrupts apical F-actin organization, and induces stress fiber formation (35, 36). However, these changes were not observed in the intestinal epithelium. Although KRIT1 knockdown compromises both the epithelial and endothelial barrier, they do so through different mechanisms. Barrier loss in KRIT1-deficient endothelial cells is ROCK dependent, as it can be reversed by ROCK inhibition (35, 36). In contrast, barrier loss caused by KRIT1 knockdown in intestinal epithelial cells cannot be reversed by ROCK inhibition (Fig. 3 and Supplemental Fig. 5). Such differences may be explained by unique cytoskeletal regulation pathways in epithelial and endothelial cells, and distinctive apical junctional complex protein expression in these cell types. KRIT1 also differentially affect TNF-induced barrier dysfunction in epithelial cells and endothelial cells: although we observed that KRIT1 loss exacerbated TNF-induced barrier loss in intestinal epithelial cells in vitro (Fig. 6), KRIT1 heterozygous knockout blocks TNF injection–induced arteriole and venule permeability increases in vivo (64, 65). The underlying mechanisms for such differences between the epithelium and endothelium also need to be determined.

The current study opens new avenues to understanding barrier maintenance and regulation in both epithelial and endothelial cells. Much effort is needed to define pathways used by KRIT1 and associated proteins to regulate the epithelial barrier and other epithelial functions and to identify common and epithelial-specific KRIT1-binding partners. Furthermore, how KRIT1 may affect functions of other types of epithelia, including renal and pulmonary epithelia, and how mutations of KRIT1 may affect epithelial-associated diseases, remain to be seen. With the data presented here and a previous finding that KRIT1 affects β-catenin signaling (39), particular emphasis should be given to understanding the role of epithelial KRIT1 in inflammatory diseases and cancer.

In summary, we report that the CCM disease–related protein KRIT1 is expressed in intestinal epithelium and affects barrier function through tight junction–dependent and –independent mechanisms. These changes may influence intestinal epithelial function, mucosal homeostasis, and gut disease pathogenesis.

Supplementary Material

This article includes supplemental data. Please visit http://www.fasebj.org to obtain this information.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank The University of Chicago Integrated Light Microscopy Core for assistance with imaging; Candace Chan and The University of Chicago Digestive Research Core Center for enteroid culture; Douglas Marchuk (Duke University, Durham, NC, USA) for providing KRIT1 encoding plasmid; Wenli Dai, Pan Li, Yuehua Wei, and Qing Wu (all from The University of Chicago) for technical support and critical reading of the manuscript; and Ying Cao (The University of Chicago) for advice on biostatistical analyses. This research was supported, in part, by the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Grants K01DK092381 (to L.S.) and P30DK042086 (to L.S., through The University of Chicago Digestive Disease Research Core Center Pilot and Feasibility Award Program); the Pilot Award from the Safadi Program of Excellence in Clinical and Translational Neuroscience at The University of Chicago (to L.S.); National Natural Science Foundation of China Grant 81400008 (to J.Z.); and the Dempsey Research Award from the American Association of Neurological Surgeons (to S.P.P.). L.S. also received partial support from the Judy and Bill Davis Fund in Neurovascular Surgery Research at The University of Chicago Medicine. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Glossary

- CCM

cerebral cavernous malformation

- EA

ethylamine

- EGFP

enhanced green fluorescent protein

- GAPDH

glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- KRIT1

Krev interaction trapped protein 1

- MA

methylamine

- MLC

myosin light chain

- MLCK

myosin light chain kinase

- NMDG

N-methyl-d-glucamine

- ROCK

Rho-associated protein kinase

- siRNA

small interfering RNA

- TEA

tetraethylammonium

- TER

transepithelial resistance

- TMA

tetramethylammonium

- ZO

zonula occludens

Footnotes

This article includes supplemental data. Please visit http://www.fasebj.org to obtain this information.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

L. Shen conceived and coordinated the study, designed, performed, and analyzed experiments, interpreted data, and drafted the paper; Y. Wang, Y. Li, J. Zou, and C. R. Weber designed, performed, and analyzed experiments, and drafted the paper; S. P. Polster, R. Lightle, T. Moore, and M. Dimaano performed and analyzed experiments and edited the paper; T.-C. He provided key experimental tools and materials, interpreted data, and edited the paper; and I. A. Awad conceived the study, interpreted data, and edited the paper; and all authors reviewed results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Balda, M. S., Matter, K. (2016) Tight junctions as regulators of tissue remodelling. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 42, 94–101 10.1016/j.ceb.2016.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chow, B. W., Gu, C. (2015) The molecular constituents of the blood-brain barrier. Trends Neurosci. 38, 598–608 10.1016/j.tins.2015.08.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Komarova, Y., Malik, A. B. (2010) Regulation of endothelial permeability via paracellular and transcellular transport pathways. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 72, 463–493 10.1146/annurev-physiol-021909-135833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buckley, A., Turner, J. R. (2018) Cell biology of tight junction barrier regulation and mucosal disease. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 10, a029314 10.1101/cshperspect.a029314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schumann, M., Siegmund, B., Schulzke, J. D., Fromm, M. (2017) Celiac disease: role of the epithelial barrier. Cell. Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 3, 150–162 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2016.12.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meza, I., Sabanero, M., Stefani, E., Cereijido, M. (1982) Occluding junctions in MDCK cells: modulation of transepithelial permeability by the cytoskeleton. J. Cell. Biochem. 18, 407–421 10.1002/jcb.1982.240180403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bentzel, C. J., Hainau, B., Edelman, A., Anagnostopoulos, T., Benedetti, E. L. (1976) Effect of plant cytokinins on microfilaments and tight junction permeability. Nature 264, 666–668 10.1038/264666a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duffey, M. E., Hainau, B., Ho, S., Bentzel, C. J. (1981) Regulation of epithelial tight junction permeability by cyclic AMP. Nature 294, 451–453 10.1038/294451a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Furuse, M., Hirase, T., Itoh, M., Nagafuchi, A., Yonemura, S., Tsukita, S., Tsukita, S. (1993) Occludin: a novel integral membrane protein localizing at tight junctions. J. Cell Biol. 123, 1777–1788 10.1083/jcb.123.6.1777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Furuse, M., Fujita, K., Hiiragi, T., Fujimoto, K., Tsukita, S. (1998) Claudin-1 and -2: novel integral membrane proteins localizing at tight junctions with no sequence similarity to occludin. J. Cell Biol. 141, 1539–1550 10.1083/jcb.141.7.1539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hecht, G., Pestic, L., Nikcevic, G., Koutsouris, A., Tripuraneni, J., Lorimer, D. D., Nowak, G., Guerriero, V., Jr., Elson, E. L., Lanerolle, P. D. (1996) Expression of the catalytic domain of myosin light chain kinase increases paracellular permeability. Am. J. Physiol. 271, C1678–C1684 10.1152/ajpcell.1996.271.5.C1678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Turner, J. R., Rill, B. K., Carlson, S. L., Carnes, D., Kerner, R., Mrsny, R. J., Madara, J. L. (1997) Physiological regulation of epithelial tight junctions is associated with myosin light-chain phosphorylation. Am. J. Physiol. 273, C1378–C1385 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.273.4.C1378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shen, L., Weber, C. R., Raleigh, D. R., Yu, D., Turner, J. R. (2011) Tight junction pore and leak pathways: a dynamic duo. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 73, 283–309 10.1146/annurev-physiol-012110-142150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van Itallie, C. M., Holmes, J., Bridges, A., Gookin, J. L., Coccaro, M. R., Proctor, W., Colegio, O. R., Anderson, J. M. (2008) The density of small tight junction pores varies among cell types and is increased by expression of claudin-2. J. Cell Sci. 121, 298–305 10.1242/jcs.021485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yu, A. S., Cheng, M. H., Angelow, S., Günzel, D., Kanzawa, S. A., Schneeberger, E. E., Fromm, M., Coalson, R. D. (2009) Molecular basis for cation selectivity in claudin-2-based paracellular pores: identification of an electrostatic interaction site. J. Gen. Physiol. 133, 111–127 10.1085/jgp.200810154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Van Itallie, C. M., Fanning, A. S., Bridges, A., Anderson, J. M. (2009) ZO-1 stabilizes the tight junction solute barrier through coupling to the perijunctional cytoskeleton. Mol. Biol. Cell 20, 3930–3940 10.1091/mbc.e09-04-0320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buschmann, M. M., Shen, L., Rajapakse, H., Raleigh, D. R., Wang, Y., Wang, Y., Lingaraju, A., Zha, J., Abbott, E., McAuley, E. M., Breskin, L. A., Wu, L., Anderson, K., Turner, J. R., Weber, C. R. (2013) Occludin OCEL-domain interactions are required for maintenance and regulation of the tight junction barrier to macromolecular flux. Mol. Biol. Cell 24, 3056–3068 10.1091/mbc.e12-09-0688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gitter, A. H., Wullstein, F., Fromm, M., Schulzke, J. D. (2001) Epithelial barrier defects in ulcerative colitis: characterization and quantification by electrophysiological imaging. Gastroenterology 121, 1320–1328 10.1053/gast.2001.29694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schulzke, J. D., Bojarski, C., Zeissig, S., Heller, F., Gitter, A. H., Fromm, M. (2006) Disrupted barrier function through epithelial cell apoptosis. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1072, 288–299 10.1196/annals.1326.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Williams, J. M., Duckworth, C. A., Burkitt, M. D., Watson, A. J., Campbell, B. J., Pritchard, D. M. (2015) Epithelial cell shedding and barrier function: a matter of life and death at the small intestinal villus tip. Vet. Pathol. 52, 445–455 10.1177/0300985814559404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marchiando, A. M., Shen, L., Graham, W. V., Edelblum, K. L., Duckworth, C. A., Guan, Y., Montrose, M. H., Turner, J. R., Watson, A. J. (2011) The epithelial barrier is maintained by in vivo tight junction expansion during pathologic intestinal epithelial shedding. Gastroenterol. 140, 1208– 1218.e1–e2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yu, D., Marchiando, A. M., Weber, C. R., Raleigh, D. R., Wang, Y., Shen, L., Turner, J. R. (2010) MLCK-dependent exchange and actin binding region-dependent anchoring of ZO-1 regulate tight junction barrier function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107, 8237–8241 10.1073/pnas.0908869107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shen, L., Turner, J. R. (2005) Actin depolymerization disrupts tight junctions via caveolae-mediated endocytosis. Mol. Biol. Cell 16, 3919–3936 10.1091/mbc.e04-12-1089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shen, L., Black, E. D., Witkowski, E. D., Lencer, W. I., Guerriero, V., Schneeberger, E. E., Turner, J. R. (2006) Myosin light chain phosphorylation regulates barrier function by remodeling tight junction structure. J. Cell Sci. 119, 2095–2106 10.1242/jcs.02915 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Akers, A., Al-Shahi Salman, R., A Awad, I., Dahlem, K., Flemming, K., Hart, B., Kim, H., Jusue-Torres, I., Kondziolka, D., Lee, C., Morrison, L., Rigamonti, D., Rebeiz, T., Tournier-Lasserve, E., Waggoner, D., Whitehead, K. (2017) Synopsis of guidelines for the clinical management of cerebral cavernous malformations: consensus recommendations based on systematic literature review by the Angioma Alliance Scientific Advisory Board Clinical Experts Panel. Neurosurgery 80, 665–680 10.1093/neuros/nyx091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Girard, R., Fam, M. D., Zeineddine, H. A., Tan, H., Mikati, A. G., Shi, C., Jesselson, M., Shenkar, R., Wu, M., Cao, Y., Hobson, N., Larsson, H. B., Christoforidis, G. A., Awad, I. A. (2017) Vascular permeability and iron deposition biomarkers in longitudinal follow-up of cerebral cavernous malformations. J. Neurosurg. 127, 102–110 10.3171/2016.5.JNS16687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mikati, A. G., Khanna, O., Zhang, L., Girard, R., Shenkar, R., Guo, X., Shah, A., Larsson, H. B., Tan, H., Li, L., Wishnoff, M. S., Shi, C., Christoforidis, G. A., Awad, I. A. (2015) Vascular permeability in cerebral cavernous malformations. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 35, 1632–1639 10.1038/jcbfm.2015.98 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Laberge-le Couteulx, S., Jung, H. H., Labauge, P., Houtteville, J. P., Lescoat, C., Cecillon, M., Marechal, E., Joutel, A., Bach, J. F., Tournier-Lasserve, E. (1999) Truncating mutations in CCM1, encoding KRIT1, cause hereditary cavernous angiomas. Nat. Genet. 23, 189–193 10.1038/13815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sahoo, T., Johnson, E. W., Thomas, J. W., Kuehl, P. M., Jones, T. L., Dokken, C. G., Touchman, J. W., Gallione, C. J., Lee-Lin, S. Q., Kosofsky, B., Kurth, J. H., Louis, D. N., Mettler, G., Morrison, L., Gil-Nagel, A., Rich, S. S., Zabramski, J. M., Boguski, M. S., Green, E. D., Marchuk, D. A. (1999) Mutations in the gene encoding KRIT1, a Krev-1/rap1a binding protein, cause cerebral cavernous malformations (CCM1). Hum. Mol. Genet. 8, 2325–2333 10.1093/hmg/8.12.2325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bergametti, F., Denier, C., Labauge, P., Arnoult, M., Boetto, S., Clanet, M., Coubes, P., Echenne, B., Ibrahim, R., Irthum, B., Jacquet, G., Lonjon, M., Moreau, J. J., Neau, J. P., Parker, F., Tremoulet, M., Tournier-Lasserve, E.; Société Française de Neurochirurgie . (2005) Mutations within the programmed cell death 10 gene cause cerebral cavernous malformations. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 76, 42–51 10.1086/426952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Denier, C., Goutagny, S., Labauge, P., Krivosic, V., Arnoult, M., Cousin, A., Benabid, A. L., Comoy, J., Frerebeau, P., Gilbert, B., Houtteville, J. P., Jan, M., Lapierre, F., Loiseau, H., Menei, P., Mercier, P., Moreau, J. J., Nivelon-Chevallier, A., Parker, F., Redondo, A. M., Scarabin, J. M., Tremoulet, M., Zerah, M., Maciazek, J., Tournier-Lasserve, E.; Société Française de Neurochirurgie . (2004) Mutations within the MGC4607 gene cause cerebral cavernous malformations. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 74, 326–337 10.1086/381718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liquori, C. L., Berg, M. J., Siegel, A. M., Huang, E., Zawistowski, J. S., Stoffer, T., Verlaan, D., Balogun, F., Hughes, L., Leedom, T. P., Plummer, N. W., Cannella, M., Maglione, V., Squitieri, F., Johnson, E. W., Rouleau, G. A., Ptacek, L., Marchuk, D. A. (2003) Mutations in a gene encoding a novel protein containing a phosphotyrosine-binding domain cause type 2 cerebral cavernous malformations. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 73, 1459–1464 10.1086/380314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guclu, B., Ozturk, A. K., Pricola, K. L., Bilguvar, K., Shin, D., O’Roak, B. J., Gunel, M. (2005) Mutations in apoptosis-related gene, PDCD10, cause cerebral cavernous malformation 3. Neurosurgery 57, 1008–1013 10.1227/01.NEU.0000180811.56157.E1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Whitehead, K. J., Chan, A. C., Navankasattusas, S., Koh, W., London, N. R., Ling, J., Mayo, A. H., Drakos, S. G., Jones, C. A., Zhu, W., Marchuk, D. A., Davis, G. E., Li, D. Y. (2009) The cerebral cavernous malformation signaling pathway promotes vascular integrity via Rho GTPases [published correction appears in Nat. Med. 2009;15(4):462]. Nat. Med. 15, 177–184 10.1038/nm.1911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stockton, R. A., Shenkar, R., Awad, I. A., Ginsberg, M. H. (2010) Cerebral cavernous malformations proteins inhibit Rho kinase to stabilize vascular integrity. J. Exp. Med. 207, 881–896 10.1084/jem.20091258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Borikova, A. L., Dibble, C. F., Sciaky, N., Welch, C. M., Abell, A. N., Bencharit, S., Johnson, G. L. (2010) Rho kinase inhibition rescues the endothelial cell cerebral cavernous malformation phenotype. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 11760–11764 10.1074/jbc.C109.097220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McDonald, D. A., Shi, C., Shenkar, R., Stockton, R. A., Liu, F., Ginsberg, M. H., Marchuk, D. A., Awad, I. A. (2012) Fasudil decreases lesion burden in a murine model of cerebral cavernous malformation disease. Stroke 43, 571–574 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.625467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shenkar, R., Shi, C., Austin, C., Moore, T., Lightle, R., Cao, Y., Zhang, L., Wu, M., Zeineddine, H. A., Girard, R., McDonald, D. A., Rorrer, A., Gallione, C., Pytel, P., Liao, J. K., Marchuk, D. A., Awad, I. A. (2017) RhoA kinase inhibition with Fasudil versus Simvastatin in Murine models of cerebral cavernous malformations. Stroke 48, 187–194 10.1161/STROKEAHA.116.015013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Glading, A. J., Ginsberg, M. H. (2010) Rap1 and its effector KRIT1/CCM1 regulate beta-catenin signaling. Dis. Model. Mech. 3, 73–83 10.1242/dmm.003293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang, F., Graham, W. V., Wang, Y., Witkowski, E. D., Schwarz, B. T., Turner, J. R. (2005) Interferon-gamma and tumor necrosis factor-alpha synergize to induce intestinal epithelial barrier dysfunction by up-regulating myosin light chain kinase expression. Am. J. Pathol. 166, 409–419 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62264-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Weber, C. R., Raleigh, D. R., Su, L., Shen, L., Sullivan, E. A., Wang, Y., Turner, J. R. (2010) Epithelial myosin light chain kinase activation induces mucosal interleukin-13 expression to alter tight junction ion selectivity. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 12037–12046 10.1074/jbc.M109.064808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shen, L., Weber, C. R., Turner, J. R. (2008) The tight junction protein complex undergoes rapid and continuous molecular remodeling at steady state. J. Cell Biol. 181, 683–695 10.1083/jcb.200711165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Deng, F., Chen, X., Liao, Z., Yan, Z., Wang, Z., Deng, Y., Zhang, Q., Zhang, Z., Ye, J., Qiao, M., Li, R., Denduluri, S., Wang, J., Wei, Q., Li, M., Geng, N., Zhao, L., Zhou, G., Zhang, P., Luu, H. H., Haydon, R. C., Reid, R. R., Yang, T., He, T. C. (2014) A simplified and versatile system for the simultaneous expression of multiple siRNAs in mammalian cells using Gibson DNA Assembly. PLoS One 9, e113064 10.1371/journal.pone.0113064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zawistowski, J. S., Serebriiskii, I. G., Lee, M. F., Golemis, E. A., Marchuk, D. A. (2002) KRIT1 association with the integrin-binding protein ICAP-1: a new direction in the elucidation of cerebral cavernous malformations (CCM1) pathogenesis. Hum. Mol. Genet. 11, 389–396 10.1093/hmg/11.4.389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Raleigh, D. R., Boe, D. M., Yu, D., Weber, C. R., Marchiando, A. M., Bradford, E. M., Wang, Y., Wu, L., Schneeberger, E. E., Shen, L., Turner, J. R. (2011) Occludin S408 phosphorylation regulates tight junction protein interactions and barrier function. J. Cell Biol. 193, 565–582 10.1083/jcb.201010065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Walsh, S. V., Hopkins, A. M., Chen, J., Narumiya, S., Parkos, C. A., Nusrat, A. (2001) Rho kinase regulates tight junction function and is necessary for tight junction assembly in polarized intestinal epithelia. Gastroenterology 121, 566–579 10.1053/gast.2001.27060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Capaldo, C. T., Macara, I. G. (2007) Depletion of E-cadherin disrupts establishment but not maintenance of cell junctions in Madin-Darby canine kidney epithelial cells. Mol. Biol. Cell 18, 189–200 10.1091/mbc.e06-05-0471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shewan, A. M., Maddugoda, M., Kraemer, A., Stehbens, S. J., Verma, S., Kovacs, E. M., Yap, A. S. (2005) Myosin 2 is a key Rho kinase target necessary for the local concentration of E-cadherin at cell-cell contacts. Mol. Biol. Cell 16, 4531–4542 10.1091/mbc.e05-04-0330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ivanov, A. I., McCall, I. C., Parkos, C. A., Nusrat, A. (2004) Role for actin filament turnover and a myosin II motor in cytoskeleton-driven disassembly of the epithelial apical junctional complex. Mol. Biol. Cell 15, 2639–2651 10.1091/mbc.e04-02-0163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Straight, A. F., Cheung, A., Limouze, J., Chen, I., Westwood, N. J., Sellers, J. R., Mitchison, T. J. (2003) Dissecting temporal and spatial control of cytokinesis with a myosin II Inhibitor. Science 299, 1743–1747 10.1126/science.1081412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Allingham, J. S., Smith, R., Rayment, I. (2005) The structural basis of blebbistatin inhibition and specificity for myosin II. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 12, 378–379 10.1038/nsmb908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Clayburgh, D. R., Barrett, T. A., Tang, Y., Meddings, J. B., Van Eldik, L. J., Watterson, D. M., Clarke, L. L., Mrsny, R. J., Turner, J. R. (2005) Epithelial myosin light chain kinase-dependent barrier dysfunction mediates T cell activation-induced diarrhea in vivo. J. Clin. Invest. 115, 2702–2715 10.1172/JCI24970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Marchiando, A. M., Shen, L., Graham, W. V., Weber, C. R., Schwarz, B. T., Austin II, J. R., Raleigh, D. R., Guan, Y., Watson, A. J., Montrose, M. H., Turner, J. R. (2010) Caveolin-1-dependent occludin endocytosis is required for TNF-induced tight junction regulation in vivo. J. Cell Biol. 189, 111–126 10.1083/jcb.200902153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gitter, A. H., Bendfeldt, K., Schulzke, J. D., Fromm, M. (2000) Leaks in the epithelial barrier caused by spontaneous and TNF-alpha-induced single-cell apoptosis. FASEB J. 14, 1749–1753 10.1096/fj.99-0898com [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zolotarevsky, Y., Hecht, G., Koutsouris, A., Gonzalez, D. E., Quan, C., Tom, J., Mrsny, R. J., Turner, J. R. (2002) A membrane-permeant peptide that inhibits MLC kinase restores barrier function in in vitro models of intestinal disease. Gastroenterology 123, 163–172; correction: 1412 10.1053/gast.2002.34235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schmitz, H., Fromm, M., Bentzel, C. J., Scholz, P., Detjen, K., Mankertz, J., Bode, H., Epple, H. J., Riecken, E. O., Schulzke, J. D. (1999) Tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNFalpha) regulates the epithelial barrier in the human intestinal cell line HT-29/B6. J. Cell Sci. 112, 137–146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Inai, T., Kobayashi, J., Shibata, Y. (1999) Claudin-1 contributes to the epithelial barrier function in MDCK cells. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 78, 849–855 10.1016/S0171-9335(99)80086-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.McCarthy, K. M., Francis, S. A., McCormack, J. M., Lai, J., Rogers, R. A., Skare, I. B., Lynch, R. D., Schneeberger, E. E. (2000) Inducible expression of claudin-1-myc but not occludin-VSV-G results in aberrant tight junction strand formation in MDCK cells. J. Cell Sci. 113, 3387–3398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fanning, A. S., Jameson, B. J., Jesaitis, L. A., Anderson, J. M. (1998) The tight junction protein ZO-1 establishes a link between the transmembrane protein occludin and the actin cytoskeleton. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 29745–29753 10.1074/jbc.273.45.29745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wittchen, E. S., Haskins, J., Stevenson, B. R. (1999) Protein interactions at the tight junction. Actin has multiple binding partners, and ZO-1 forms independent complexes with ZO-2 and ZO-3. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 35179–35185 10.1074/jbc.274.49.35179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Samarin, S. N., Ivanov, A. I., Flatau, G., Parkos, C. A., Nusrat, A. (2007) Rho/Rho-associated kinase-II signaling mediates disassembly of epithelial apical junctions. Mol. Biol. Cell 18, 3429–3439 10.1091/mbc.e07-04-0315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sutton, T. A., Mang, H. E., Atkinson, S. J. (2001) Rho-kinase regulates myosin II activation in MDCK cells during recovery after ATP depletion. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 281, F810–F818 10.1152/ajprenal.2001.281.5.F810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Imai, M., Furusawa, K., Mizutani, T., Kawabata, K., Haga, H. (2015) Three-dimensional morphogenesis of MDCK cells induced by cellular contractile forces on a viscous substrate. Sci. Rep. 5, 14208 10.1038/srep14208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Corr, M., Lerman, I., Keubel, J. M., Ronacher, L., Misra, R., Lund, F., Sarelius, I. H., Glading, A. J. (2012) Decreased Krev interaction-trapped 1 expression leads to increased vascular permeability and modifies inflammatory responses in vivo. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 32, 2702–2710 10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.300115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Goitre, L., DiStefano, P. V., Moglia, A., Nobiletti, N., Baldini, E., Trabalzini, L., Keubel, J., Trapani, E., Shuvaev, V. V., Muzykantov, V. R., Sarelius, I. H., Retta, S. F., Glading, A. J. (2017) Up-regulation of NADPH oxidase-mediated redox signaling contributes to the loss of barrier function in KRIT1 deficient endothelium. Sci. Rep. 7, 8296 10.1038/s41598-017-08373-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.