Abstract

Pausing of RNA polymerase II (Pol II) during early transcription, mediated by the negative elongation factor (NELF) complex, allows cells to coordinate and appropriately respond to signals by modulating the rate of transcriptional pause release. Promoter proximal enrichment of Pol II occurs at uterine genes relevant to reproductive biology; thus, we hypothesized that pausing might impact endometrial response by coordinating hormonal signals involved in establishing and maintaining pregnancy. We deleted the NELF-B subunit in the mouse uterus using PgrCre (NELF-B UtcKO). Resulting females were infertile. Uterine response to the initial decidual stimulus of NELF-B UtcKO was similar to that of control mice; however, subsequent full decidual response was not observed. Cultured NELF-B UtcKO stromal cells exhibited perturbances in extracellular matrix components and also expressed elevated levels of the decidual prolactin Prl8a2, as well as altered levels of transcripts encoding enzymes involved in prostaglandin synthesis and metabolism. Because endometrial stromal cell decidualization is also critical to human reproductive health and fertility, we used small interfering to suppress NELF-B or NELF-E subunits in cultured human endometrial stromal cells, which inhibited decidualization, as reflected by the impaired induction of decidual markers PRL and IGFBP1. Overall, our study indicates NELF-mediated pausing is essential to coordinate endometrial responses and that disruption impairs uterine decidual development during pregnancy.—Hewitt, S. C., Li, R., Adams, N., Winuthayanon, W., Hamilton, K. J., Donoghue, L. J., Lierz, S. L., Garcia, M., Lydon, J. P., DeMayo, F. J., Adelman, K., Korach, K. S. Negative elongation factor is essential for endometrial function.

Keywords: uterus, NELF, Pol II pausing, decidualization

Pausing of RNA polymerase II (Pol II) during early transcriptional elongation is an important rate-limiting step in which an engaged transcription complex pauses near some transcription start sites (1, 2). The NELF complex mediates the pausing and is composed of 4 subunits (A, B, C/D, and E) (3). Cells are able to coordinate and appropriately respond to different signals by modulating the rate of pause release through recruitment of pTEF-b, which phosphorylates NELF and serine 2 of the Pol II amino terminal domain, leading to disassociation of the NELF complex and allowing RNA elongation (1). Phenotypes resulting from deletion of NELFA or NELFC/D in animal models have not yet been described. Reported preweaning lethality in a NELF-E deletion mouse model (4), and embryonic lethality of mice with disrupted pausing due to deletion of the NELF-B subunit emphasize the critical roles of this mechanism in biologic processes but also hinder study of postembryonic roles for this activity (5).

During pregnancy, the uterus responds to diverse signals that occur in critical temporal windows. The ovarian hormones estrogen (E2) and progesterone (P4) fluctuate as oocytes mature and are ovulated, fertilized in the oviduct, and then implanted in the uterine wall (6). All uterine cells contain estrogen receptor α (7), whereas the levels of progesterone receptor (PGR) vary in different uterine cell types according to the levels of E2 (6). Massive uterine tissue remodeling occurs during pregnancy to support the growing embryo and placenta (8). Uterine stromal cells undergo a process called decidualization that is driven by rising levels of ovarian hormones coupled with signals initiated by contact with the embryo as it interacts with and invades the uterine wall. These signals induce decidualization, a process by which stromal cells change from fibroblast-like cells to rounded cells via alterations in their extracellular matrix components; decidualized stromal cells secrete prolactins and synthesize prostaglandins. Perturbations in many of these key uterine functions are major contributors to pathologies, including leiomyoma, preeclampsia, endometriosis, endometrial hyperplasia, and cancer, that impact women’s health (6, 9). We previously performed Pol II chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing on estrogen-stimulated mouse uterine tissue and analyzed Pol II accumulation near transcription start sites (10). These data revealed promoter proximal enrichment of Pol II at a number of genes relevant to reproductive biology; thus, we hypothesized that transcriptional pausing might impact endometrial response to hormonal signals and endometrial remodeling during pregnancy.

Here we used a conditional knockout approach to disrupt the transcriptional pausing complex in uterine cells by deleting the NELF-B subunit using PgrCre (NELF-B UtcKO). Resulting females were infertile; therefore, we characterized the endometrial functions linked to hormonal actions that are critical for establishing and maintaining pregnancy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

PgrCre+ mice (11) were bred with mice with loxP sites flanking the first 4 exons of Nelfb (12). Breeding PgrCre+; Nelfb f/f × Nelfb f/− resulted in PgrCre+; Nelfb f/f or PgrCre+; Nelfb f/− females, called NELF-B UtcKO. NELF-B f/f and f/− females were used as controls and are called wild type (WT). Ear biopsies were sent to Transnetyx (Cordova, TN, USA) for genotyping.

Breeding trial to assess fertility

WT males were continuously bred with WT or NELF-B UtcKO females for 6 mo. Males were switched to the opposite genotype female 3 mo into the study. Average litters per dam and pups per litter were calculated.

Vaginal cytology and superovulation

Vaginal cytology was evaluated each morning for 12 d by washing the exterior of the vagina with 50 μl of normal saline, drying each sample on a glass slide, and staining with Giemsa. Slides were evaluated and assigned to the appropriate stage of the estrous cycle. For superovulation, females were injected with 3.25 IU of pregnant mare serum gonadotropin in the afternoon and then injected 48 h later with 2.2 IU of human chorionic gonadotropin. Oocytes were collected 16 h later from the bursa and counted.

Decidualization assay

Adult females (>10 wk old) were ovariectomized, rested for 10–14 d to clear ovarian hormones, and then treated daily for 3 d with E2 (100 ng in 100 µl sesame oil, s.c.). Two days after the last E2 injection, mice were treated daily with P4 (1 mg) + E2 (6.7 ng) in 100 µl sesame oil injected subcutaneously. On the third day of P4 + E2 injection, 6 h after the P4 + E2 treatment, 100 µl sesame oil was injected into the lumen of 1 uterine horn. Twenty hours or 3 d (72 h) later, uterine tissue was collected. Two hours before collection, mice were injected with EdU (2 mg/ml in PBS) to label DNA synthesis. Uterine horns were separated at the cervix and weighed. A piece was fixed in 10% formalin, and the remainder was snap frozen in liquid nitrogen for RNA analysis.

Hormone treatments

Ovariectomized females were injected with E2 (250 ng in 100 µl saline, i.p., for 24 h or 250 ng in 100 µl sesame oil, s.c., daily for 3 d). For the progesterone switch experiment, ovariectomized females were injected with E2 daily for 2 d (100 ng in 100 µl sesame oil, s.c.). They rested for 3 d and then injected with P4 (1 mg in 100 µl sesame oil, s.c., for 3 d and with P4 or P4 + 100 ng/ml E2 on the fourth day). Tissue was collected 18 h later. For 24-h E2 treatments and the progesterone switch experiment, mice were injected with EdU 2 h before tissues were collected. Luminal epithelial cell heights were measured on hematoxylin and eosin–stained sections using the measurement tool of the ImageJ software package (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA; https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/) by placing 3 markers of cell layer height in 5 different areas per section.

Decidualization of primary hESC culture

Endometrial stromal cells were isolated from proliferative phase endometrial biopsies obtained from healthy volunteers of reproductive age with regular menstrual cycles and no history of gynecologic malignancy, according to a human subjects protocol approved by the Institutional Review Board of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences and cultured and transfected with small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) (On-TargetPlus SmartPool; Dharmacon, Lafayette, CO, USA) targeting NELF-B (siNELF-B) or NELF-E (siNELF-E) or with a nontargeting control (siNT) as previously described (13). Cells were treated with vehicle (V treatment) or 10 nM E2 (E1024; MilliporeSigma, Burlington, MA, USA), 1 μM medroxyprogesterone acetate (M1629; MilliporeSigma), and 100 μM 2’-O-dibutyryladenosine-3′, cAMP (D0627; MilliporeSigma) to induce decidualization [E2 + P4 + cAMP (EPC) treatment].

RT-PCR

RNA and cDNA were prepared from mouse uterine tissue as previously described (14). RNA was prepared from cultured mouse stromal cells or hESCs using 1 ml Trizol reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) with 250 µg/ml glycogen (MilliporeSigma) and used to synthesize cDNA as previously described (14). Mouse uterine cDNA was diluted 1:100, and hESC was diluted 1:10 for PCR analysis. Values were calculated relative to the control sample described in each figure; mouse uterine samples were normalized to Rpl7, and hESC was normalized to GAPDH. Sequences of primers are listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Primers used

| Gene | Primer, 5′–3′ |

|---|---|

| Human | |

| hBAD_246 F | AACCAGCAGCAGCCATCAT |

| hBAD_339 R | CATCCCTTCGTCGTCCTCC |

| GAPDH F | ATGGGGAAGGTGAAGGTCG |

| GAPDH R | GGGGTCATTGATGGCAACAATA |

| hIGFBP1_778 F | GGCTCTCCATGTCACCAACA |

| hIGFBP1_870 R | GTCTCCTGTGCCTTGGCTAA |

| hNELFB_251 F | GGACCTGAAGGAGACCCTGA |

| hNELFB_350 R | GGCTGACTGAAGAGATGGCA |

| NELFE_455 F | AGGCTTCAAGCGTTCTCGAA |

| NELFE_546 R | ATATGCTCCTCTGGAACGGC |

| hPRL_1066 R | GATGGAAGTCCCGACCAGAC |

| hPRL_962 F | GGAGCAAACCAAACGGCTTC |

| Mouse | |

| Bmp2 1435-1534 F | CTAGATCTGTACCGCAGGCA |

| Bmp2 R | CACGGCTTCTTCGTGATG |

| Wnt4 F | AGTGACAAGGGCATGCAGC |

| Wnt4 R | CATCCTGACCACTGGAAGCC |

| Prl8a2 272-345 F | TACCACAACCCATTCTCAGC |

| Prl8a2 R | GCAGTGATTTCTGGCTCTGA |

| Ccnb1 F | TTGTGTGCCCAAGAAGATGCT |

| Ccnb1 R | GTACATCTCCTCATATTTGCTTGCA |

| Ccnb2 F | ATGTCAACAAGCAGCCGAAAC |

| Ccnb2 R | GAGGACGATCCTTGGGAGCTA |

| Ccna2_1334 F | TACCTCAAAGCGCCACAACA |

| Ccna2_1430 R | GTGTCTCTGGTGGGTTGAGA |

| Mad2l1 F | TGGTAGTGTTCTCCGTTCGATCT |

| Mad2l1 R | GCAGGGTGATGCCTTGCT |

| Cdc2a F | GGACGAGAACGGCTTGGAT |

| Cdc2a R | GGCCATTTTGCCAGAGATTC |

| Mki67_474 F | CCTGTGAGGCTGAGACATGG |

| Mki67_566 R | TGTTGGCTTGCTTCCATCCT |

| Des_803 F | GCAGAATCGAATCCCTCAA |

| Des_853 R | AGCTCACGGATCTCCTCTTC |

| Krt18 F | CTTGCCGCCGATGACTTTA |

| Krt18 R | CCTTGCGGAGTCCATGGA |

| mCobra1F 1053-1072 F | TGGATCCCTGCCATAAGTTC |

| mCobra1R 1234-1215 R | CAGGGACAGTGTGTTGATGG |

| Lama4_4335 F | ACAAGCAGTACCACGATGGG |

| Lama4_4432 R | CTTCCCTCGAAGTCGGCTTT |

| Col11a1_3823 F | CCTGTTGGTGCTCCTGGAAT |

| Col11a1_3914 R | GCGCCCTCATCACCTTTTTG |

| Itgb2_1745 F | ATAACAGCCAAGTCTGCGGT |

| Itgb2_1853 R | GTGGTGGACCTCTGACACTG |

| Mmp19_942 F | AAACCTGGTCCCATGCCAAA |

| Mmp19_1045 R | ACAGTCCACACATAGTCGCC |

| Hsd11b2 F | GCTTCAAGACAGATGCAGTGACTAA |

| Hsd11b2 R | CTGGAGCAGCTCTCTAGGAATGTT |

| Ptgs2 F | AAGGCTCAAATATGATGTTTGCATT |

| Ptgs2 R | CCCAGGTCCTCGCTTATGATC |

| Edn1 F | TTCCCGTGATCTTCTCTCTGCT |

| Edn1 R | TCTGCTTGGCAGAAATTCCA |

| Rpl7 F | AGCTGGCCTTTGTCATCAGAA |

| Rpl7 R | GACGAAGGAGCTGCAGAACCT |

| Egr1_558 F | CCCTATGAGCACCTGACCAC |

| Egr1_652 R | CGAGTCGTTTGGCTGGGATA |

| Mad2l1 F | TGGTAGTGTTCTCCGTTCGATCT |

| Mad2l1 R | GCAGGGTGATGCCTTGCT |

| Ltf F | CAGCAGGATGTGATAGCCACAA |

| Ltf R | CACTGATCACACTTGCGCTTCT |

| Ramp3 F | GGAGCCACGTGTGACCTACTG |

| Ramp3 R | AGCCCACACTGGACACAGAAT |

| Nelfb DNA deleted allele primers | |

| LoxP 5′ F2 | ATTCGGCCAAACCTGCAGGAAGTA |

| LoxP 5′ R | TAACTTCCAAGACAGCCAGGCGTA |

| mIgfERE2 F | TTCCAGCCACCTCTCCACTTAC |

| mIgf1ERE2 R | CTGTGGAGCCATTGTTGGATCT |

Immunohistochemistry and EdU detection

Uterine tissue was embedded in paraffin and sectioned (4 µM) onto charged slides. Ki67 (550609; BD Pharmingen/BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) was detected as previously described (14), except blocking solution 10% normal horse serum (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA, USA) with 1% bovine serum albumin (MilliporeSigma) and 1% Blotto (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA) was used in place of 10% horse serum. EdU was detected using the Click-iT Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). NELF-B (ab16740, Rabbit Anti-Human Cobra1 pAb; Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA) and NELF-E (10705-1-AP, Rabbit Anti-Human RDBP pAb; Proteintech Group, Chicago, IL, USA) were detected after sections were deparaffinized and then decloaked in a Biocare Decloaking Chamber with Biocare Antigen Decloaking Buffer (Biocare Medical, Pacheco, CA, USA) and blocked with 5% H2O2. Sections were blocked with blocking solution (10% normal goat serum; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) with 1% bovine serum albumin (MilliporeSigma) and 1% Blotto (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and then incubated with antibody diluted in blocking solution (NELF-B 1:50; NELF-E 1:200). Subsequently, antibody was localized with biotinyl-anti-rabbit IgG (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) and extravidin peroxidase (MilliporeSigma) and Dako Products DAB (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). For detection of NELF-B on cytospins, a similar method was used, beginning at the decloaking step. For quantification, the Cell Count tool in ImageJ was used to count 100–200 luminal epithelial or stromal cells in a uterine section, and then to identify and count Ki67- or EdU-positive cells among those counted to calculate the percentage of positive cells.

Culture of mouse uterine stroma cells

Females were mated overnight with B6D2F1/J males, and uterine tissue was collected in the afternoon from 4 dpc females (morning of plug detection = 0.5 dpc), slit longitudinally, minced into 3- to 5-mm pieces, and washed several times with HBSS (MilliporeSigma). Uteri (2 to 3 each) were then placed in a 50-ml tube with 5 ml of 6 mg/ml dispase (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and 25 mg/ml pancreatin (MilliporeSigma) made in HBSS. Tissue was incubated for 60 min on ice, followed by 60 min at room temperature and then 10 min at 37°C. HBSS (30 ml) with 10% FBS was added to each tube. Tissue was washed 2 times with 10 ml HBSS and moved to a 50-ml tube containing 0.5 mg/ml collagenase (MilliporeSigma) and incubated for 45 min at 37°C. Tubes were vortexed until turbid. HBSS (30 ml) + 10% FBS was added, and the suspension passed through a 70-µM filter (MACS Smart Strainer; Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA, USA). Cells were collected by centrifuging at 450 g for 10 min and washed twice in 10 ml HBSS, then resuspended in DMEM-F12 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) containing 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum. Cells (400,000) in 3 ml of media were seeded per well of a 6-well plate and allowed to attach for 1 to 2 h. Wells were then washed several times with HBSS to remove nonadherent cells, and fresh DMEM-F12 containing 2% stripped fetal calf serum supplemented with P (1 µM) and E (10 nM) (PE, decidual stimulus) or ethanol [vehicle (V)] was added. After 3 d, cells were collected with Trizol for RNA isolation for RT-PCR, or were trypsinized and collected on cytospins for immunohistochemistry, or were collected using protein lysis buffer for Western blots.

Western blots

Protein was isolated from whole uteri or from cultured mouse or human uterine stromal cells by homogenizing with a protein extraction buffer [50 mM Tris, pH 7.5; 150 mM NaCl; 1% Triton X-100; and 2.5 mg/ml deoxycholate containing aprotinin (20 µg/ml), leupeptin (20 µg/ml), PMSF (4 µg/ml), and phosphatse inhibitors 2 and 3, all from MilliporeSigma]. Pierce BCA assay was used to quantify proteins, which were separated on Nupage BisTris gels with MOPS running buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes using the iBlot apparatus (Thermo Fisher Scientific). NELF-B (ab16740 1:500; Abcam), NELF-E (10705-1-AP 1:1000; Proteintech), and bActin (1616R 1:5000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) proteins were detected after blocking in TBST (20 mM Tris, 140 mM NaCl, and 0.1% TWEEN 20) containing 5% Blotto (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and probing with primary antibodies, followed by near infrared labeled secondary antibodies (Li-Cor Biosciences, Lincoln, NE, USA), and detected using the Li-Cor Fc instrument with Image Studio software (v.5.2; Li-Cor Biosciences).

Evaluation of allele deletion

DNA was prepared from uterine tissue using the DNAEasy Kit (Qiagen, Germantown, MD, USA) and tested using primers that detect the loxP site that is deleted by Cre excision (LoxP 5′ F2, LoxP 5′ R) relative to a region of DNA outside the Nelfb locus (Igf ERE2).

Microarray

Cultured mouse uterine stromal cells were collected 24 h after hormone treatment, and RNA was isolated as described above and submitted to the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences Microarray Core Facility (Bethesda, MD, USA) and analyzed on the Affymetrix MTA Array (Thermo Fisher Scientific) with Transcriptome Analysis Console (TAC) software (Thermo Fisher Scientific. Microarray data were deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus (National Center for Biotechnology Information, Bethesda, MD, USA), accession number GSE122262.

RESULTS

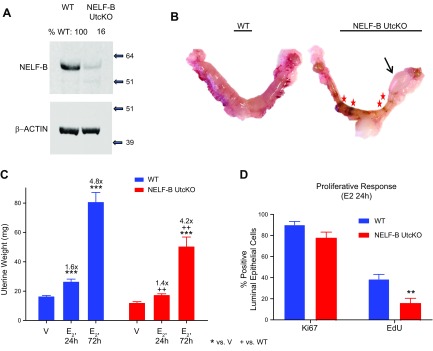

To evaluate potential biologic roles for transcriptional pausing in endometrial function, negative elongation factor B (NELF-B), a subunit of the 4-subunit NELF complex, was deleted using Pgr-Cre, which results in deletion of Exons 1–4 of Nelfb. Studies in cell culture models have indicated that knockdown or deletion of 1 NELF subunit can destabilize the other NELF subunits by making them vulnerable to proteolysis (15–17). Therefore, we evaluated the presence of both the NELF-B and NELF-E subunits in WT and NELF-B Uterine KO. NELF-B and NELF-E were detected throughout the endometrial tissue of the WT uterus (Supplemental Fig. S1A), in myometrial cells (outer layers), epithelial cells (lining the uterine lumen and glands), and stromal cells (between myometrial and stromal layers). Crossing the NELF-B f/f with PgrCre to generate NELF-B UtcKO decreased NELF-B and NELF-E in most mouse uterine cells. NELF-B and NELF-E were deleted in most stromal cells, with remaining NELF in epithelial cells (Supplemental Fig. S1A). Western blotting of uterine proteins, using the same NELF-B antibody that was used for IHC and binds to the N terminus of the NELF-B protein (Fig. 1A), revealed an NELF-B signal that is 16% of the amount seen in WT. The amount of undeleted Nelfb allele detected in uterine DNA was significantly decreased in NELF-B UtcKO (Supplemental Fig. S1B).

Figure 1 .

Effect of NELF-B deletion on uterine functions. A) Western blot of uterine protein homogenates from WT or NELF-B UtcKO uterine tissue for NELF-B or bACTIN as a loading control. The blots were quantified, and NELF-B signal normalized to bACTIN. NELF-B protein detected in the sample relative to WT is listed above each lane. B) Reproductive tract tissue at end of 6 mo of continuous breeding. Arrow indicates ballooning area. C) Mean ± sem uterine weights after treating ovariectomized WT or NELF-B UtcKO females with vehicle (V) or E2 for 24 or 72 h (h). Treatment of WT with E2 for 24 h (n = 9) or 72 h (n = 3) increased the uterine weight relative to WT V-treated controls (n = 6). Fold increases relative to V are shown above each bar. NELF-B UtcKO uteri treated with V (n = 5) weigh less than WT, but not significantly less (P = 0.17). Treatment of NELF-B UtcKO with E2 for 24 h (n = 7) increased the uterine weight, but not significantly (P = 0.8), whereas treatment with E2 for 72 h (n = 3) significantly increased the uterine weight; however, both E2 treatments at 24 and 72 h yielded a mean uterine weight less than that of WT. ***P < 0.001 vs. V, ++P < 0.01 vs. WT (2-way ANOVA with false discovery rate (FDR) posttest). D) Quantification of percent luminal epithelial cells that are positive for proliferative markers Ki67 (n = 6 WT and 6 NELF-B UtcKO) or EdU (n = 6 WT and 4 NELF-B UtcKO) after treating ovariectomized WT or NELF-B UtcKO females with E2 for 24 h. **P < 0.01 vs. WT (2-way ANOVA with FDR posttest).

We evaluated the fertility of the NELF-B UtcKO females by mating them with fertile males for 6 mo. WT females delivered an average of 4.4 litters with 6.05 pups per litter, whereas NELF-B UtcKO females did not deliver any (Table 2). Uterine tissue was collected and examined at the end of the 6-mo mating trial, and NELF-B UtcKO tissue appeared abnormal both grossly and histologically (Fig. 1B and Supplemental Fig. S2A). Age-matched uterine tissue collected from virgin NELF-B UtcKO females indicated most, but not all, of the abnormalities were breeding related (Supplemental Fig. S2B). Because Pgr-driven Cre activity also occurs in the adult ovary granulosa cells (11), and NELF-B is detected in ovarian cells (data not presented), ovary function was evaluated. Vaginal cytology of estrous cyclicity and superovulation of adult (26-wk-old) NELF-B UtcKO were assessed, and both were found to be comparable with those of WT littermates (Supplemental Fig. S3).

TABLE 2.

Fertility of females in 6-mo breeding trial

| Type | Litters/dam | Pups/litter |

|---|---|---|

| WT [f/f, (n = 5)] | 4.4 ± 0.4 | 6.05 ± 2.74a |

| NELF-B UtcKO (n = 5) | 0 | 0 |

Values are means ± sem.

Two litters were found dead and not counted, and are not included in this number.

Endometrial response to ovarian hormones is critical for successful pregnancy (6). Uterine tissue responses to E2 or P4 were next evaluated using 2 bioassays that allow evaluation of responses intrinsic to the uterine tissue separate from pregnancy. First, ovariectomized mice were treated with a single E2 injection, and uterine tissue was evaluated 24 h later for indications of growth responses. Alternatively, E2 was administered daily for 3 d and uterine tissue collected on the fourth day. E2 induced uterine growth, as evidenced by increased weight after 24 or 72 h (Fig. 1C and Supplemental Fig. S4A); in addition, E2 induced proliferation and DNA synthesis in epithelial cells as reflected by Ki67 detection and EdU incorporation (Fig. 1D and Supplemental Fig. S4B). E2 increased uterine weights of NELF-B UtcKO, but uteri were significantly smaller than WT controls (Fig. 1C). Following E2 treatments for 24 h, not all of the NELF-B UtcKO epithelial cells expressed Ki67 or showed EdU incorporation, leading to an overall lower percentage of luminal epithelial cells that were positive for the DNA synthesis incorporation indicator, EdU (Fig. 1D and Supplemental Fig. 4B). Another measure of mouse endometrial response to E2 is the height of the luminal epithelium. After 72 h of E2 treatment, WT uteri display a significantly greater increase in luminal epithelial cell height than NELF-B UtcKO (Supplemental Fig. S4A). Overall, NELF-B UtcKO respond appropriately to E2, but have a blunted growth response (epithelial cell hypertrophy and hypoplasia). Evaluation of Mad2l1, Ltf, and Ramp3, which are established E2-responsive uterine transcripts, by real-time PCR revealed no difference between WT and NELF-B UtcKO responses (Supplemental Fig. S4C). Ltf is selectively induced in epithelial cells (18), and Ramp3 in stromal cells (19), indicating both cell types are responding to E2.

Uterine PGR is primarily restricted to the epithelial cells of ovariectomized mice, and E2 decreases epithelial PGR and increases stromal PGR, allowing stromal cell to respond to rising postovulatory P4 and nidatory E2 (6). Mitosis of stromal cells and inhibition of epithelial cell proliferation are critical to embryonic implantation. Treating ovariectomized females with a course of E2 and P4 injections that mimics the implantation window leads to stromal cell proliferation, as reflected by EdU incorporation and Ki67-positive cells (Supplemental Fig. S5). Following this treatment, some NELF-B UtcKO uteri fail to respond appropriately, exhibit stromal cell response before E2 treatment, and fail to inhibit epithelial cell proliferation (Supplemental Fig. S5).

Stromal cell proliferation is critical to the decidual response, in which the stromal cells expand and differentiate into polyploid decidual cells during endometrial remodeling to support the implanting embryo, placenta formation, and establishment of blood supply (6). To directly evaluate the stromal cell response, we simulated artificial decidualization by treating ovariectomized females with E2 and P4 to mimic ovulation and implantation profiles and injecting inert oil into the lumen of 1 uterine horn to mimic interaction with embryos.

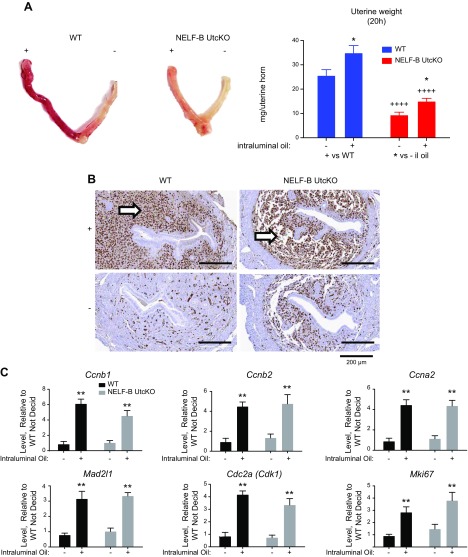

Examining responses 20 h after intraluminal oil infusion reveals an increased weight of the oil-infused uterine horn (Fig. 2A), independent of the presence of NELF-B. This suggests that the initial stromal cell response to the decidual stimulus was not disrupted by NELF-B deletion. Both NELF-B and NELF-E are detected throughout the cells of WT uteri (Supplemental Fig. S6), and both are decreased in most cells of NELF-B UtcKO uteri and remain in epithelial cells (Supplemental Fig. S6). Ki67 and EdU, indicators of stromal cell proliferation, were detected in samples from oil-infused uterine horns, regardless of NELF-B expression (Fig. 2B and Supplemental Fig. S6). Consistent with this observed response, uterine transcripts reflecting cell cycle activity (Cnnb1, Ccnb2, Ccna2, Mad2l1, Cdk1, Mki67) were similarly induced (Fig. 2C). NELF-B UtcKO uteri are nevertheless significantly smaller than WT (Fig. 2A).

Figure 2 .

Decidual response of NELF-B UtcKO is initiated. A) Decidual response visualized 20 h after intraluminal injection of inert oil into 1 uterine horn (as described in Materials and Methods) is apparent in both WT and NELF-B UtcKO mice as an increase in red color and weight of injected uterine horn (+) in comparison with the uninjected control horn (−). The weights of the NELF-B UtcKO are significantly smaller than WT. *P < 0.05 vs. −horn, ++++P < 0.0001 vs. WT (2-way ANOVA with FDR posttest; n = 4 to 5 samples/group). B) Histologic changes and Ki67-positive cells seen in WT and NELF-B UtcKO mice. Arrow indicates areas of proliferation. Scale bars, 200 μM. C) RT-PCR for indicators of cell cycle progression: Ccnb1, Ccnb2, Ccna2, Mad2l1, Cdc2a, Mki67, 20 h after oil injections, calculated relative to −WT; **P < 0.01 vs. −horn (2-way ANOVA with FDR posttest; n = 3–5 samples/group).

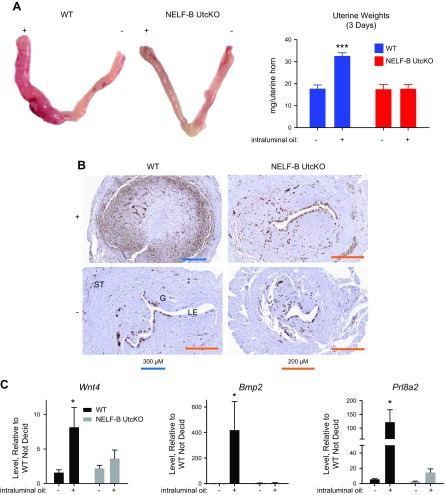

Three days after the intraluminal oil infusion, WT uteri exhibited a significant increase in uterine weight (Fig. 3A) when compared with a noninfused horn. In contrast, the NELF-B UtcKO uterus did not respond to the decidualization stimulus (Fig. 3A). Histologically, oil-infused WT uterine tissue shows indications of decidual development, with loss and displacement of luminal epithelia; appearance of large, rounded decidual cells; development of vascular structures; and positive proliferative markers at the margins of the developing decidua (Fig. 3B and Supplemental Fig. S7). Additionally, both NELF-B and NELF-E are detected in the decidualized WT uteri (Supplemental Fig. 7), as well as in NELF-B UtcKO epithelial cells. Oil-infused NELF-B UtcKO uteri appear similar to noninfused controls (Fig. 3B and Supplemental Fig. S7). Uterine RNA was used to assess the induction of decidual markers, Wnt4, Bmp2, and Prl8a2. All 3 were increased in WT oil-infused uterine horns, whereas NELF-B UtcKO uteri lacked a similar response (Fig. 3C).

Figure 3 .

Decidual response of NELF-B UtcKO is impaired. A) Decidual response visualized 3 d after intraluminal injection of inert oil into 1 uterine horn (as described in Materials and Methods) is apparent in WT mice as an increase in size and weight of injected uterine horn (+) in comparison with the uninjected control horn (−), whereas the response is not seen in NELF-B UtcKO mice. ***P < 0.001 vs. −horn (2-way ANOVA with FDR posttest; n = 3–5 samples/group). B) Histologic changes and Ki67-positive cells seen in WT and NELF-B UtcKO mice as described in text. LE, luminal epithelium; ST, stroma; G, gland. Arrow indicates region of proliferation. C) RT-PCR for decidual markers Wnt4, Bmp2, and Prl8a2 3 d after oil injection. *P < 0.05 vs. −horn (2-way ANOVA with FDR posttest; n = 3–5 samples/group).

Because the initial response of the uterine stromal cells was not impacted by NELF-B deletion, but development of decidual cells required NELF-B, we utilized an in vitro stromal cell culture model to examine responses intrinsic to the decidualizing cells. Stromal cells were isolated from 4 dpc uterine tissue and cultured with P4 and E2 to induce decidualization. Both WT and NELF-B UtcKO stroma cells attach and spread within the first day. By d 3 of culture, NELF-B UtcKO cells appear sparse and less elongated (Fig. 4A). To confirm the enrichment of stromal cells, RNA was evaluated for Des, a marker of stromal cells, and for the epithelial cell marker Krt18; both were detected in patterns indicating enrichment of respective cell populations relative to d 4 uterine tissue (Fig. 4B). The decidual marker Prl8a2 was induced by PE treatment in WT stromal cells (Fig. 4B). Interestingly, although decidualization failed to progress in the whole uterus, Prl8a2 was very highly expressed in the absence of NELF-B in isolated stromal cells (Fig. 4B). Additionally, the basal level of expression of Prl8a2 was greater than the induced level in the WT cells. Evaluation of Nelfb transcript (Fig. 4B) revealed its reduction in the NELF-B UtcKO cells; additionally, NELF-B protein was decreased in cultured NELF-B UtcKO stromal cells (Supplemental Fig. S8).

Figure 4 .

Decidualization of cultured mouse uterine stromal cells. A) Cultured NELF-B UtcKO uterine stromal cells do not effectively attach to culture dish. Phase contrast images of uterine stromal cells isolated from 4 dpc pregnant WT or NELF-B UtcKO mice, cultured for 3 d with progesterone and estrogen, are shown. Scale bars, 10 μM. B) Enrichment of decidual stromal cells RT-PCR of RNA prepared from 4 dpc whole uterus (UT) or from uterine stromal cells (SC) isolated from 4 dpc pregnant WT or NELF-B UtcKO mice, cultured for 3 d with progesterone and estrogen (PE), or vehicle (V). Des (stromal cell marker) and Keratin18 (Krt18, epithelial cell marker) were evaluated in PE-treated SC samples relative to RNA prepared from 4 dpc whole uterus (UT); WT UT = 1.0. Decidual prolactin, Prl8a2, or Nelfb levels relative to WT V = 1.0 (2-way ANOVA with FDR posttest; n = 3 samples/condition for cultured SC; n = 1 4-dpc uterus for UT). *P < 0.05 vs. UT, *P < 0.05 vs. V, +P < 0.05 vs. WT.

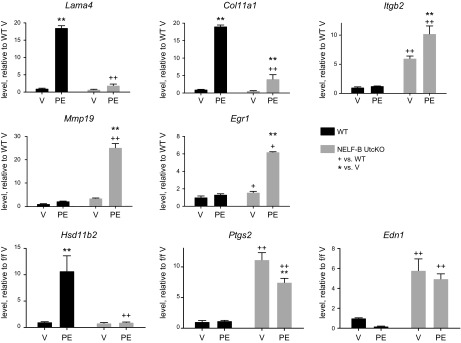

Next, we analyzed RNA from the d 1 decidualized cells by microarray. The differentially expressed genes [>2-fold, false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.05] were evaluated for enrichment of pathways (Table 3). Consistent with the observed morphologic differences, extracellular matrix (ECM) receptor interaction was significantly enriched. Col11a1 and Lama4 were decreased and Mmp19 and Itgb2 were increased in NELF-B UtcKO uterine stromal cells (Fig. 5). MMPs are involved in remodeling ECM (20), and laminins interact with collagen in the ECM and integrins on the cell surface (21); thus the changes in their levels may impact the ability of the NELF-B–deficient cells to deposit ECM and attain proper morphology.

TABLE 3.

Pathway enrichment of DEG from NELF-B UtcKO vs. WT microarray of uterine stromal cells, cultured for 24 h

| Pathway | Enrichment score | Enrichment P | Genes in pathway that are present (%) | NELF-B UtcKO vs. WT score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ECM-receptor interaction | 12.7157 | 3.00E−06 | 18.8235 | 3.70262 |

| DNA replication | 12.603 | 3.36E−06 | 29.4118 | 3.79416 |

| Purine metabolism | 10.882 | 1.88E−05 | 12.9213 | 3.57095 |

| Steroid biosynthesis | 10.8221 | 2.00E−05 | 36.8421 | 3.62401 |

| Cell cycle | 10.2318 | 3.60E−05 | 14.4 | 3.50764 |

| Biosynthesis of antibiotics | 10.0519 | 4.31E−05 | 11.7371 | 3.63459 |

| Focal adhesion | 9.65822 | 6.39E−05 | 11.7073 | 3.76059 |

| Amoebiasis | 9.63154 | 6.56E−05 | 14.2857 | 3.7452 |

| Terpenoid backbone biosynthesis | 7.83721 | 0.000395 | 28.5714 | 3.56586 |

| PI3K-Akt signaling pathway | 7.7382 | 0.000436 | 9.1954 | 3.57493 |

| Transcriptional misregulation in cancer | 7.71078 | 0.000448 | 11.236 | 3.51364 |

| p53 signaling pathway | 6.74893 | 0.001172 | 15.3846 | 3.65164 |

| Energy metabolism | 6.58006 | 0.001388 | 10.7784 | 3.5715 |

| Biosynthesis of unsaturated fatty acids | 6.39143 | 0.001676 | 22.2222 | 3.38081 |

| Pyrimidine metabolism | 6.38681 | 0.001684 | 12.5 | 3.65591 |

| Protein digestion and absorption | 6.35439 | 0.001739 | 13.0435 | 3.78477 |

| Cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction | 6.20078 | 0.002028 | 9.26641 | 3.39442 |

| Glutathione metabolism | 5.62921 | 0.003591 | 15.3846 | 3.936 |

| Fatty acid metabolism | 5.62921 | 0.003591 | 15.3846 | 3.39975 |

| Metabolic pathways | 5.43896 | 0.004344 | 6.47482 | 3.57297 |

| Central carbon metabolism in cancer | 5.15236 | 0.005786 | 13.2353 | 3.77421 |

| Cell adhesion molecules | 4.9246 | 0.007266 | 9.93377 | 3.42582 |

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG; https://www.genome.jp/kegg/kegg1.html) database was used.

Figure 5 .

Altered expression of extracellular matrix and prostaglandin synthesis components. RT-PCR of RNA prepared from uterine stromal cells isolated from 4 dpc pregnant WT or NELF-B UtcKO mice and cultured for 3 d with progesterone and estrogen (PE) or vehicle (V) are shown. Laminin α4 (Lama4), collagen, type XI, α1, (Col11a1) integrin β2 (Itgb2), and matrix metallopeptidase 19 (Mmp19) were evaluated; WT V = 1.0. **P < 0.01 vs. V, ++P < 0.01 vs. WT (2-way ANOVA with FDR posttest; n = 3 samples/group). Hsd11b2, Ptgs2, and Edn1 were evaluated. WT V = 1.0. **P < 0.01 vs. V, ++P < 0.01 vs. WT (2-way ANOVA with FDR posttest; n = 3 samples/group).

A second enriched function of interest is steroid biosynthesis. Induction of Hsd11b2 during decidualization of the stromal cells, which inactivates corticosterone, is lost in NELF-B–deficient stromal cells (Fig. 5). Hsd11b2 is also linked to prostaglandin synthesis, and other factors in prostaglandin signaling are altered in NELF-B–deficient stromal cells. Edn1, which facilitates arachidonic acid release from phospholipids, and Ptgs2, which synthesizes prostaglandin H2, are both increased (Fig. 5). Additionally, Egr1, a transcription factor that interferes with decidual progression (22), is overexpressed in PE-stimulated NELF-B UtcKO cells.

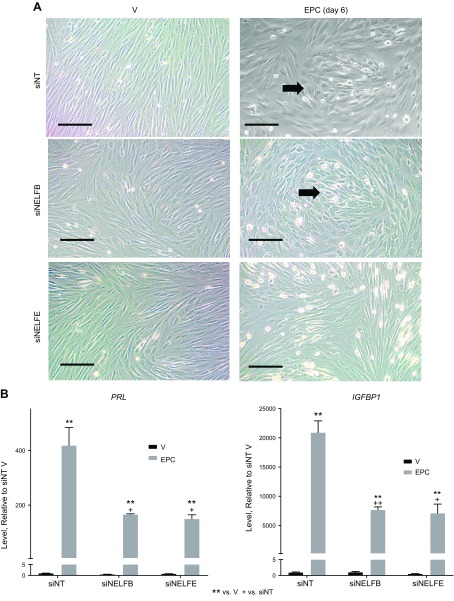

Decidualization of endometrial stromal cells is critical to human fertility and is also driven by hormonal signals. Perturbations in hormone response are linked to diseases including endometriosis and infertility (23). To evaluate whether our mouse study, which indicated an essential role of NELF in decidualization, was applicable to human uterine function, we utilized a well-characterized in vitro system in which cultured hESCs are treated with EPC to induce their decidualization (23). Using siRNA to decrease NELF-B did not alter the appearance of decidualized cells; however, siNELF-E–treated cells did not attain the rounded “cobblestone-like” appearance of decidualized cells (Fig. 6A). Evaluation of expression of decidual markers, prolactin (PRL) and IGFBP1, indicated increased expression following treatment of siNT cells (Fig. 6B) but significantly blunted levels of induction in siNELF-B or siNELF-E cells (Supplemental Fig. S9A). Expression of WNT4 was induced by decidualization, and its induction was decreased by siNELF-E (Supplemental Fig. S9A). NELF-B or NELF-E transcripts were decreased by the decidualization treatment and were further decreased by their respective siRNAs (Supplemental Fig. S9A). In addition, siNELF-B decreased NELF-B and NELF-E protein to 12% of the amount in siNT samples (Supplemental Fig. S9B). Similarly, siNELF-E decreased NELF-E and NELF-B protein to 26–29% of the amount in siNT samples (Supplemental Fig. S9B). This phenomenon has been previously reported and demonstrates that NELF subunits stabilize each other (24). BAD transcript was evaluated as an indicator of cell survival to ensure decreasing NELF complex impacted decidual response and not cell viability. BAD transcript was similarly expressed regardless of NELF status (Supplemental Fig. S9A).

Figure 6 .

Suppressing NELF inhibits decidualization of cultured human endometrial stromal cells. A) Phase contrast images of cultured human endometrial stromal cells transfected with siRNA (siNT, nontargeting control, siNELF-B, or siNELF-E) and cultured for 6 d with vehicle (V) or EPC. Decidualized cells change shape from elongated to rounded (arrows). Scale bars, 20 μM. B) Induction of decidualization transcripts is reduced when NELF is decreased. RT-PCR of RNA prepared from cultured human endometrial stromal cells transfected with siRNA (siNT, nontargeting control, siNELF-B or siNELF-E) and cultured for 6 d with V or EPC. siNT V = 1.0. **P < 0.01 vs. V, +P < 0.05 vs. siNT (2-way ANOVA with FDR posttest; n = 3 samples/group).

DISCUSSION

Initially, we hypothesized that NELF complex–mediated Pol II transcriptional pausing would impact uterine E2 responsiveness. However, disruption of NELF-B subunit expression had minimal impact on E2 response, in terms of transcription. We did observe a small but significant attenuation of uterine growth, which is consistent with observations of impaired growth of NELF-B KO embryonic fibroblast cells (25). We did note remaining NELF-B and NELF-E protein in uterine epithelial cells. This is unexpected, considering Pgr-driven Cre activity is consistently seen in uterine epithelial cells (11). The impact of NELF-B deletion on uterine growth was observed following E2 stimulation (Fig. 1C, D and Supplemental Fig. S4) and also after the initiation of decidual response, in both the oil infused and the nonstimulated horns (Fig. 2A). Although the uterine tissue does show indications of cellular proliferation in both these studies, qualitatively the stromal cells appear fewer in number (Fig. 2B and Supplemental Fig. S4B).

Disruption of uterine Nelfb leads to female infertility as a result of impaired decidual response. Studies designed to focus on the uterine decidual response of NELF-B UtcKO females indicated an initial response to the hormonal (P4 and E2) and physical (intraluminal oil) stimuli, suggesting initiation of decidual response does not require NELF-mediated activities. Subsequent full development of decidual tissue was lost, suggesting NELF complex is required later in the decidualization process. Therefore, perhaps the role of NELF is in setting up responses to signals needed subsequent to the initial processes that initiate pregnancy. Using cultured mouse and human uterine stromal cells, we confirmed an impact of NELF on the decidual response. However, in the case of the mouse uterine cells, Nelfb deletion led to overexpression, rather than impairment of induction, of the decidual marker Prl8a2. Although this differs from our observations in the whole uterus, it does indicate an alteration of transcriptional control and altered cellular differentiation. Additionally, cultured NELF-B UtcKO mouse stromal cells had altered extracellular matrix components, weakening their attachment to the culture dish.

In the mouse, embryos implant on 4.5 dpc; initially stromal cell proliferation occurs, followed by stromal cell transformation into polyploid decidual cells surrounding the implanted embryo at implantation sites, apparent by 6–8 dpc (26, 27). When we experimentally induce decidualization, the intraluminal oil injection is designed to mimic embryo apposition and attachment to the uterine lumen before implantation (4 dpc). The response we observe 20 h after oil infusion mirrors the proliferation that occurs at 5 dpc; this response still occurred when Nelfb was absent, but the overall size of the uterine tissue was smaller than WT (Fig. 2A). Later, 72 h after oil infusion, the weight of the unstimulated horn of the NELF-B UtcKO increased and matched that of the WT (Fig. 3A). This suggests that NELF-B is not required for the initiation of decidual response, but that the full growth response is delayed. Underdeveloped implantation sites form after transfer of embryos to pseudopregnant NELF-B UtcKO females (data not presented), consistent with initiation of uterine response, and impaired stromal cell growth. NELF-B UtcKO mouse uterine stroma cells cultured outside the organ exhibit enhanced decidual marker expression, suggesting that the NELF complex may control the rate of decidualization. We noted a decrease in both Nelfb and Nelfe transcripts in cultured mouse and hESCs as a result of the decidualization-inducing treatments (PE for mouse cells, EPC for hESCs). This shows that lowering NELF is part of the process leading to decidualization, so that perhaps NELF slows the rate of decidual progression. However, when we further decreased or disrupted NELF using Cre deletion in mouse cells or siRNA in hESCs, decidualization was impaired, which supports a role for NELF in balancing the progression and timing of the decidual processes, highlighting an essential role of transcriptional pausing as a mechanism that impacts optimal reproduction.

To indicate possible underlying effects of NELF disruption that impact uterine stromal cell function, we compared genes impacted in our cultured mouse uterine cells to the Knockdown Atlas of the Nextbio Correlation Engine. The analysis revealed a positive correlation between differentially expressed genes (DEG) in Nelfb KO vs. WT mouse embryonic fibroblast cells. DEG common to both uterine stromal cell and embryonic fibroblast datasets indicate genes that are targets of the NELF complex, with the increased DEG normally repressed by NELF, and decreased DEG being NELF–induced targets. Interestingly, included in DEG that are increased by Nelfb disruption are 4 members of the Histone H1 cluster (Hist1h1c, Hist1h2bc, Hist1h2be, and Hist1h4i) and Brd2, all involved in chromatin structure. In general, cellular differentiation involves extensive chromatin remodeling (28); perhaps, then, alteration in levels of these chromatin structure components could contribute to cessation of decidual differentiation, by interfering with needed chromatin structures following NELF disruption. Also increased is Egr1, a transcription factor that inhibits decidualization of uterine stromal cells (22), suggesting a role for NELF in controlling the level of EGR1 during the decidual process. Egr1 overexpression in NELF-B UtcKO calls was validated by RT-PCR in mouse uterine stromal cells cultured for 3 d (Fig. 5). Conversely, Nelfb disruption decreases expression of Mad2l1, which is involved in cell cycle progression, in both MEFs and uterine stromal cells, consistent with decreases in cell proliferation observed following disruption of NELF. Similarly, several components of the extracellular matrix (Col1a1, Col6a1, Fbn1, P4ha2) are decreased in both embryonic fibroblasts and uterine stromal cells following deletion of Nelfb, consistent with our observation of reduced adherence of uterine stromal cells.

In summary, our findings indicate a previously unrevealed role for NELF-dependent transcriptional pausing in endometrial function. Using 2 model systems, we have demonstrated the importance of NELF in coordinating endometrial responses essential for successful reproduction. Because endometrial dysfunctions underlie conditions including endometriosis, endometrial cancer, and infertility, which impact women’s health, our findings revealing a role for transcriptional pausing in endometrial function have the potential to advance our mechanistic understanding of these pathologies.

Supplementary Material

This article includes supplemental data. Please visit http://www.fasebj.org to obtain this information.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Drs. Karina Rodriguez and Ru-Pin Alicia Chi [both from the U.S. National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIH/NIEHS)] for critically reading the manuscript. The authors thank the NIH, NIEHS Histology Core for processing of tissue samples, and the NIEHS Microarray Core for analysis of samples. The expert surgical and animal care of the NIEHS Comparative Medicine Branch is greatly appreciated. This research was supported, in part, by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, (NIEHS Grant 1Z1AE5070065 to K.S.K). The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Glossary

- BAD

BCL2-associated agonist of cell death

- Bmp

bone morphogenetic protein

- Ccn

Cyclin

- Cdk

cyclin-dependent kinase

- Col

collagen

- DEG

differentially expressed gene

- Des

Desmin

- ECM

extracellular matrix

- Edn

endothelin

- EPC

E2 + P4 + cAMP

- FDR

false discovery rate

- GAPDH

glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- hESC

human endometrial stromal cells

- Hsd

hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase

- IGFBP

insulin-like growth factor binding protein

- Itg

integrin

- Krt

keratin

- Lama

laminin

- Mad2l

MAD2 mitotic arrest deficient-like

- Mki67

monoclonal antibody Ki 67

- Mmp

matrix metallopeptidase

- NELF

negative elongation factor

- NELF-B UtcKO

NELF-B uterine conditional knockout

- P4

progesterone

- PGR

progesterone receptor

- PolII

RNA polymerase II

- PRL

prolactin

- Ptgs2

prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 2

- siNELF

small interfering RNA targeting NELF

- siNT

small interfering RNA with nontargeting control

- siRNA

small interfering RNA

- Wnt

wingless-type MMTV integration site family

- WT

wild type

Footnotes

This article includes supplemental data. Please visit http://www.fasebj.org to obtain this information.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

S. C. Hewitt, R. Li, N. Adams, and K. S. Korach designed research; S. C. Hewitt, K. J. Hamilton, and S. L. Lierz analyzed data; S. C. Hewitt, R. Li, N. Adams, W. Winuthayanon, K. J. Hamilton, L. J. Donoghue, S. L. Lierz, and M. Garcia performed research; S. C. Hewitt wrote the manuscript; and J. P. Lydon, F. J. DeMayo, and K. Adelman contributed new reagents.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adelman, K., Lis, J. T. (2012) Promoter-proximal pausing of RNA polymerase II: emerging roles in metazoans. Nat. Rev. Genet. 13, 720–731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu, X., Kraus, W. L., Bai, X. (2015) Ready, pause, go: regulation of RNA polymerase II pausing and release by cellular signaling pathways. Trends Biochem. Sci. 40, 516–525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yamaguchi, Y., Shibata, H., Handa, H. (2013) Transcription elongation factors DSIF and NELF: promoter-proximal pausing and beyond. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1829, 98–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dickinson, M. E., Flenniken, A. M., Ji, X., Teboul, L., Wong, M. D., White, J. K., Meehan, T. F., Weninger, W. J., Westerberg, H., Adissu, H., Baker, C. N., Bower, L., Brown, J. M., Caddle, L. B., Chiani, F., Clary, D., Cleak, J., Daly, M. J., Denegre, J. M., Doe, B., Dolan, M. E., Edie, S. M., Fuchs, H., Gailus-Durner, V., Galli, A., Gambadoro, A., Gallegos, J., Guo, S., Horner, N. R., Hsu, C. W., Johnson, S. J., Kalaga, S., Keith, L. C., Lanoue, L., Lawson, T. N., Lek, M., Mark, M., Marschall, S., Mason, J., McElwee, M. L., Newbigging, S., Nutter, L. M., Peterson, K. A., Ramirez-Solis, R., Rowland, D. J., Ryder, E., Samocha, K. E., Seavitt, J. R., Selloum, M., Szoke-Kovacs, Z., Tamura, M., Trainor, A. G., Tudose, I., Wakana, S., Warren, J., Wendling, O., West, D. B., Wong, L., Yoshiki, A., MacArthur, D. G., Tocchini-Valentini, G. P., Gao, X., Flicek, P., Bradley, A., Skarnes, W. C., Justice, M. J., Parkinson, H. E., Moore, M., Wells, S., Braun, R. E., Svenson, K. L., de Angelis, M. H., Herault, Y., Mohun, T., Mallon, A. M., Henkelman, R. M., Brown, S. D., Adams, D. J., Lloyd, K. C., McKerlie, C., Beaudet, A. L., Bućan, M., Murray, S. A.; International Mouse Phenotyping Consortium ; Jackson Laboratory ; Infrastructure Nationale PHENOMIN, Institut Clinique de la Souris (ICS) ; Charles River Laboratories ; MRC Harwell ; Toronto Centre for Phenogenomics ; Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute ; RIKEN BioResource Center . (2016) High-throughput discovery of novel developmental phenotypes. Nature 537, 508–514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Amleh, A., Nair, S. J., Sun, J., Sutherland, A., Hasty, P., Li, R. (2009) Mouse cofactor of BRCA1 (Cobra1) is required for early embryogenesis. PLoS One 4, e5034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adams, N. R., DeMayo, F. J. (2015) The role of steroid hormone receptors in the establishment of pregnancy in rodents. In Regulation of Implantation and Establishment of Pregnancy in Mammals: Tribute to 45 Year Anniversary of Roger V. Short’s Maternal Recognition of Pregnancy (Geisert, R. D., and Bazer, F. W., eds.), Vol. 216, pp. 27–50, Springer International Publishing, Basel, Switzerland: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hewitt, S. C., Korach, K. S. (2018) Estrogen Receptors: New Directions in the New Millennium. Endocr. Revi. 39, 664–675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ramathal, C. Y., Bagchi, I. C., Taylor, R. N., Bagchi, M. K. (2010) Endometrial decidualization: of mice and men. Semin. Reprod. Med. 28, 17–26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patel, B., Elguero, S., Thakore, S., Dahoud, W., Bedaiwy, M., Mesiano, S. (2015) Role of nuclear progesterone receptor isoforms in uterine pathophysiology. Hum. Reprod. Update 21, 155– 173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hewitt, S. C., Li, L., Grimm, S. A., Chen, Y., Liu, L., Li, Y., Bushel, P. R., Fargo, D., Korach, K. S. (2012) Research resource: whole-genome estrogen receptor α binding in mouse uterine tissue revealed by ChIP-seq. Mol. Endocrinol. 26, 887– 898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Soyal, S. M., Mukherjee, A., Lee, K. Y., Li, J., Li, H., DeMayo, F. J., Lydon, J. P. (2005) Cre-mediated recombination in cell lineages that express the progesterone receptor. Genesis 41, 58–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gupte, R., Muse, G. W., Chinenov, Y., Adelman, K., Rogatsky, I. (2013) Glucocorticoid receptor represses proinflammatory genes at distinct steps of the transcription cycle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110, 14616–14621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Adams, N. R., Vasquez, Y. M., Mo, Q., Gibbons, W., Kovanci, E., DeMayo, F. J. (2017) WNK lysine deficient protein kinase 1 regulates human endometrial stromal cell decidualization, proliferation, and migration in part through mitogen-activated protein kinase 7. Biol. Reprod. 97, 400–412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hewitt, S. C., Winuthayanon, W., Pockette, B., Kerns, R. T., Foley, J. F., Flagler, N., Ney, E., Suksamrarn, A., Piyachaturawat, P., Bushel, P. R., Korach, K. S. (2015) Development of phenotypic and transcriptional biomarkers to evaluate relative activity of potentially estrogenic chemicals in ovariectomized mice. Environ. Health Perspect. 123, 344–352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Narita, T., Yung, T. M., Yamamoto, J., Tsuboi, Y., Tanabe, H., Tanaka, K., Yamaguchi, Y., Handa, H. (2007) NELF interacts with CBC and participates in 3′ end processing of replication-dependent histone mRNAs. Mol. Cell 26, 349–365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sun, J., Watkins, G., Blair, A. L., Moskaluk, C., Ghosh, S., Jiang, W. G., Li, R. (2008) Deregulation of cofactor of BRCA1 expression in breast cancer cells. J. Cell. Biochem. 103, 1798–1807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sun, J., Pan, H., Lei, C., Yuan, B., Nair, S. J., April, C., Parameswaran, B., Klotzle, B., Fan, J. B., Ruan, J., Li, R. (2011) Genetic and genomic analyses of RNA polymerase II-pausing factor in regulation of mammalian transcription and cell growth. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 36248–36257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Teng, C. T. (2002) Lactoferrin gene expression and regulation: an overview. Biochem. Cell Biol. 80, 7–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Watanabe, H., Takahashi, E., Kobayashi, M., Goto, M., Krust, A., Chambon, P., Iguchi, T. (2006) The estrogen-responsive adrenomedullin and receptor-modifying protein 3 gene identified by DNA microarray analysis are directly regulated by estrogen receptor. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 36, 81–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McEwan, M., Lins, R. J., Munro, S. K., Vincent, Z. L., Ponnampalam, A. P., Mitchell, M. D. (2009) Cytokine regulation during the formation of the fetal-maternal interface: focus on cell-cell adhesion and remodelling of the extra-cellular matrix. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 20, 241–249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mouw, J. K., Ou, G., Weaver, V. M. (2014) Extracellular matrix assembly: a multiscale deconstruction. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 15, 771–785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kommagani, R., Szwarc, M. M., Vasquez, Y. M., Peavey, M. C., Mazur, E. C., Gibbons, W. E., Lanz, R. B., DeMayo, F. J., Lydon, J. P. (2016) The promyelocytic leukemia zinc finger transcription factor is critical for human endometrial stromal cell decidualization. PLoS Genet. 12, e1005937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gellersen, B., Brosens, J. J. (2014) Cyclic decidualization of the human endometrium in reproductive health and failure. Endocr. Rev. 35, 851–905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sun, J., Li, R. (2010) Human negative elongation factor activates transcription and regulates alternative transcription initiation. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 6443–6452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Williams, L. H., Fromm, G., Gokey, N. G., Henriques, T., Muse, G. W., Burkholder, A., Fargo, D. C., Hu, G., Adelman, K. (2015) Pausing of RNA polymerase II regulates mammalian developmental potential through control of signaling networks. Mol. Cell 58, 311–322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cha, J. M., Dey, S. K. (2015) Reflections on rodent implantation. Adv. Anat. Embryol. Cell Biol. 216, 69–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cha, J., Sun, X., Dey, S. K. (2012) Mechanisms of implantation: strategies for successful pregnancy. Nat. Med. 18, 1754–1767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li, E. (2002) Chromatin modification and epigenetic reprogramming in mammalian development. Nat. Rev. Genet. 3, 662–673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.