SUMMARY

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) T2 relaxation time assesses non-invasively cartilage composition and can be used as early biomarker for knee osteoarthritis. Most knee cartilage segmentation techniques were primarily developed for volume measurements in DESS or SPGR sequences. For T2 quantifications, these segmentations need to be superimposed on T2 maps. However, given that these procedures are time consuming and require manual alignment, using them for analysis of T2 maps in large clinical trials like the Osteoarthritis Initiative (OAI) is challenging.

A novel direct segmentation technique (DST) for T2 maps was therefore developed. Using the DST, T2 measurements were performed and compared with those determined with an established segmentation superimposition technique (SST). MR images of five OAI participants were analysed with both techniques three times by one reader and five different images sets additionally with DST three times by two readers.

Segmentations and T2 measurements of one knee required on average 63 ± 3 min with DST (vs 302 ± 13 min for volume and T2 measurements with SST). Bland–Altman plots indicated good agreement between the two segmentation techniques, respectively the two readers. Reproducibility errors of both techniques (DST vs SST) were similar (P > 0.05) for whole knee cartilage mean T2 (1.46% vs 2.18%), laminar (up to 2.53% vs 3.19%) and texture analysis (up to 8.34% vs 9.45%). Inter-reader reproducibility errors of DST were higher for texture analysis (up to 15.59%) than for mean T2 (1.57%) and laminar analysis (up to 2.17%). Due to these results, the novel DST can be recommended for T2 measurements in large clinical trials like the OAI.

Keywords: Magnetic resonance imaging, Osteoarthritis, Cartilage, T2 relaxation time, Reproducibility

Short report

Subjects

A subset of 10 subjects of the Osteoarthritis Initiative (OAI) were included in this study. The OAI is an ongoing multi-centre, longitudinal, prospective observational cohort study, focussing primarily on knee osteoarthritis (OA). The study protocol, amendments, and informed consent documentation including analysis plans were reviewed and approved by the local institutional review boards. Data used in the preparation of this article were obtained from the OAI database, which is available for public access at http://www.oai.ucsf.edu/. The specific dataset used was the baseline image dataset 0.E.1. All subjects were randomly selected from the incidence cohort. These subjects were characterized by absence of symptomatic OA but risk factors for OA. The 10 subjects (five males, five females) were 52 ± 3 years old and had no radiographic OA (Kellgren–Lawrence score ≤ 1).

MR imaging

All subjects underwent 3T magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (Trio, Siemens, Erlangen, Germany) of the right knee using a standard knee coil. The following sequences were used in this study as described in the OAI MRI protocol1: a sagittal three-dimensional double echo in steady state (DESS) with water excitation, pulse repetition time of 16.3 ms, echo time (TE) of 4.7 ms, bandwidth of 185 Hz/pixel, in-plane spatial resolution of 0.365 mm × 0.456 mm (0.365 mm × 0.365 mm after reconstruction), and slice thickness of 0.7 mm and in addition a sagittal two-dimensional multislice multiecho spin-echo with pulse repetition time of 2,700 ms, seven TEs (10 ms, 20 ms, 30 ms, 40 ms, 50 ms, 60 ms, and 70 ms), bandwidth of 250 Hz/pixel, in-plane spatial resolution of 0.313 mm × 0.446 mm (0.313 mm × 0.313 mm after reconstruction), slice thickness of 3.0 mm, and 0.5 mm gap were used.

Image analysis

Images were transferred to a remote SUN workstation (Sun Microsystems, Mountain View, CA, USA) and T2 maps were created. Studies have suggested that excluding the first echo from a multiecho Carr-Purcell-Meiboom-Gill sequence minimizes error from stimulated echoes in calculated T2 values for cartilage2,3. Raya et al. showed that a fit to a noise-corrected exponential improves the accuracy and precision of cartilage T2 measure- ments4. Therefore T2 maps were calculated with custom-built software on a pixel-by-pixel basis skipping the first echo and using a noise-corrected exponential fitting. T2 measurements of the articular knee cartilage were performed in six distinct compartments, i.e., medial/lateral femur, medial/lateral tibia, trochlea and patella5.

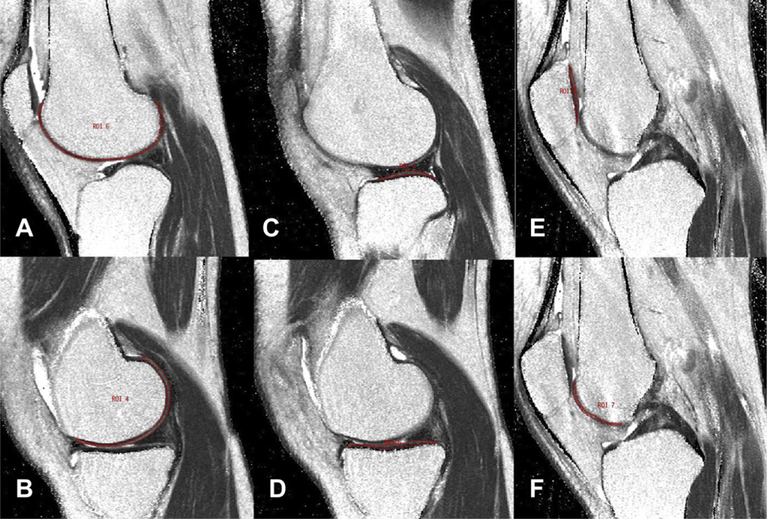

With the novel “direct segmentation technique” (abbreviated DST), segmentation of the cartilage was directly performed in the T2 maps. An interactive display language (IDL) routine was developed for the manual drawing of volumes of interest (VOI) delineating cartilage areas on the T2 maps (Fig. 1). In order to exclude both fluid and chemical shift artifacts from the VOI, a technique was used that allowed adjustment of the VOI simultaneously in the T2 map and first echo of the multiecho sequence by opening separate image panels at the same time with synchronized cursor, slice number and zoom. The DST was already used in a recent study for the patella compartment6.

Fig. 1.

Cartilage segmentation in T2 maps: contour of each compartment is marked in one representative slice, i.e., lateral femur (A), medial femur (B), lateral tibia (C), medial tibia (D), patella (E) and trochlea (F).

A custom-built IDL (Research Systems, Boulder, CO, USA) routine was used to calculate mean T2 values for each compartment after completed segmentation. Laminar analysis divided the segmented cartilage compartments in a superficial and a deep layer and corresponding mean T2 values were determined7,8. Texture analysis based on the grey level co-occurrence matrix (GLCM) was used to characterize the spatial distribution of cartilage T2 in each compartment8,9. GLCM were calculated slice-by-slice with an inter-pixel distance of one and orientations of 0°, 45°, 90° and 135°. According to previous studies8,9, the following texture parameters were obtained from the GLCM: contrast, dissimilarity, homogeneity, angular second moment (ASM), energy, entropy, mean, variance and correlation.

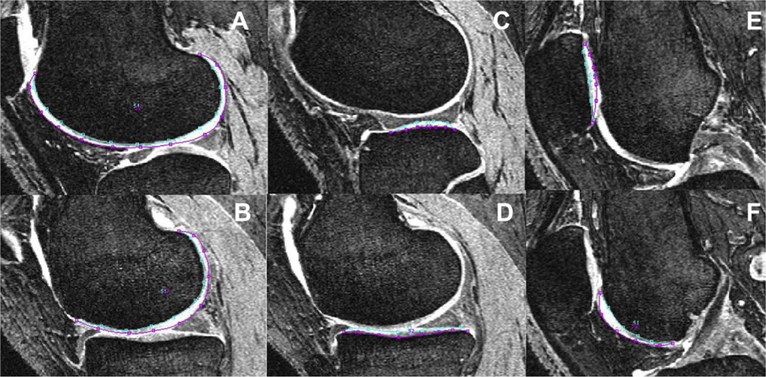

A semi-automatic segmentation technique, based on Bezier splines and edge detection, was primarily developed for cartilage volume and thickness measurements in DESS or SPGR sequences10,11. For T2 quantifications, T2 maps need to be registered on these sequences and cartilage segmentations need to be resampled and superimposed on the T2 maps. This so-called “segmentation superimposition technique” (abbreviated SST) was used in previous studies for T2 quantifications7–9. We considered SST as reference standard and performed segmentations additionally with SST in this study to compare the T2 measurements obtained with DST and SST. Using SST, cartilage segmentation was performed in the sagittal DESS images. Thus, the contour of each compartment was marked in all slices of the DESS sequences (Fig. 2). After registration and superimposition on the T2 maps, areas with partial volume effects due to fluid and with cartilage defects appeared as clusters with elevated values and were manually excluded from the respective VOI.

Fig. 2.

Cartilage segmentation in DESS images: contour of each compartment is marked in one representative slice, i.e., lateral femur (A), medial femur (B), lateral tibia (C), medial tibia (D), patella (E) and trochlea (F).

One observer (TB) performed the segmentations and analyses for the MR images of five subjects with both segmentation techniques three times in different sessions. The time between the different readings and segmentations was more than 24 h. First segmentations and analyses of the five knees with SST were performed, followed by those with DST. Subsequently, the procedure was repeated a second and third time.

MR images of the five other study participants were segmented and analysed with DST by two readers (TB and CM-H) independently of each other three times to determine the operator-dependent error of DST (inter-reader variance). First segmentations and analyses of all five knees were performed, followed by a second and third course of segmentations and analyses.

Statistical analysis

Intra- and inter-reader reproducibility errors for T2 measurements of each compartment were calculated in absolute numbers as root mean square average of the errors for each knee and on percentage basis as the root mean square average of the single coefficients of variation per knee, according to Gluer et al.12.

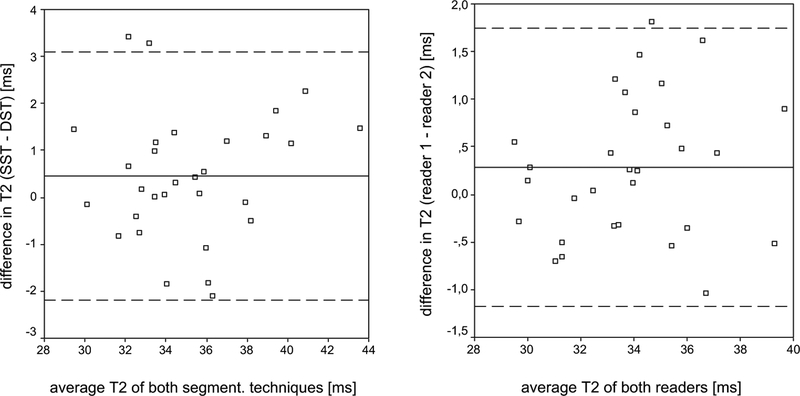

Bland–Altman plots were used to assess the agreement between the two segmentation techniques, respectively the two readers. For this purpose, means of T2 quantifications were calculated for the repeated measurements. Out of these average values, the difference and mean of the two segmentation techniques, respectively the two readers, were determined and for all compartments collectively plotted against each other. The average difference d and its standard deviation (SD) can be used to estimate the limits of agreement (d ± 1.96 × SD). If the limits of agreement are close enough to be not clinically important, segmentation techniques are interchangeable, respectively DST is not reader- dependent.

All statistical analyses were performed with Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA, USA) and SPSS (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and supervised by a biostatistician.

Comparison of DST vs SST

Segmentations and T2 measurements of one knee required on average 63 ± 3 min with DST vs 302 ± 13 min with SST.

The Bland–Altman plot indicated good agreement between the two segmentation techniques (Fig. 3). The two segmentation techniques showed an average difference of 0.45 ± 1.35 ms for mean T2 values. The reproducibility errors of T2 measurements for both techniques were not significantly different (P > 0.05) and are listed in Table Ia, combined and separately for each compartment. Averaged over all six compartments, DST and SST reproducibility errors were similar for mean T2 values (1.46% vs 2.18%). In absolute numbers, mean T2 errors amounted 0.49 ms vs 0.81 ms. The highest mean T2 error values for DST and SST were found in the medial tibia compartment (2.36% vs 3.39%, respectively 0.76 ms vs 1.39 ms).

Fig. 3.

Bland–Altman plots show good agreement between the two segmentation techniques, respectively the two readers for mean T2. The solid line indicates the mean difference of the segmentation techniques, respectively the two readers for mean T2. The dashed lines indicate mean difference ± 1.96 × SD.

Table I.

(a) RMS (root mean square) and absolute reproducibility errors for the two segmentation techniques DST and SST. (b) Inter-reader reproducibility errors of DST. Error values are displayed for each compartment (LF: Lateral Femur, LT: Lateral Tibia, MF: Medial Femur, MT: Medial Tibia, PAT: Patella, TRO: Trochlea) and averaged over all compartments

| Mean | LF | LT | MF | MT | PAT | TRO | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (a): DST vs SST | |||||||

| Mean T2 RMS error DST [%] | 1.46 | 1.52 | 1.02 | 1.18 | 2.36 | 1.19 | 1.50 |

| Mean T2 RMS error SST [%] | 2.18 | 1.08 | 2.57 | 1.46 | 3.39 | 2.32 | 2.25 |

| Mean T2 absolute error DST [ms] | 0.49 | 0.53 | 0.34 | 0.44 | 0.76 | 0.38 | 0.51 |

| Mean T2 absolute error SST [ms] | 0.81 | 0.38 | 0.86 | 0.63 | 1.39 | 0.79 | 0.82 |

| Superficial layer mean T2 RMS error DST [%] | 1.81 | 1.24 | 2.01 | 1.21 | 3.48 | 1.50 | 1.42 |

| Superficial layer mean T2 RMS error SST [%] | 2.58 | 1.37 | 3.76 | 1.05 | 5.73 | 2.26 | 1.28 |

| Superficial layer mean T2 absolute error DST [ms] | 0.64 | 0.46 | 0.69 | 0.47 | 1.24 | 0.50 | 0.50 |

| Superficial layer mean T2 absolute error SST [ms] | 0.91 | 0.49 | 1.37 | 0.41 | 1.90 | 0.82 | 0.47 |

| Deep layer mean T2 RMS error DST [%] | 2.53 | 2.77 | 1.92 | 1.71 | 3.62 | 2.14 | 3.03 |

| Deep layer mean T2 RMS error SST [%] | 3.19 | 2.39 | 2.82 | 2.38 | 3.53 | 3.75 | 4.26 |

| Deep layer mean T2 absolute error DST [ms] | 0.83 | 0.94 | 0.62 | 0.63 | 1.13 | 0.65 | 1.05 |

| Deep layer mean T2 absolute error SST [ms] | 1.31 | 0.84 | 0.87 | 1.13 | 2.03 | 1.39 | 1.58 |

| Contrast 0° RMS error DST [%] | 7.26 | 7.74 | 6.89 | 3.21 | 11.54 | 8.13 | 6.05 |

| Contrast 0° RMS error SST [%] | 9.53 | 4.59 | 14.56 | 5.21 | 15.60 | 11.35 | 5.89 |

| Dissimilarity 0° RMS error DST [%] | 2.41 | 2.65 | 2.10 | 1.76 | 4.19 | 2.19 | 1.54 |

| Dissimilarity 0° RMS error SST [%] | 3.58 | 1.87 | 5.09 | 1.74 | 5.64 | 4.58 | 2.56 |

| Homogeneity 0° RMS error DST [%] | 3.23 | 2.90 | 3.22 | 5.27 | 3.30 | 1.72 | 2.97 |

| Homogeneity 0° RMS error SST [%] | 2.61 | 1.45 | 3.66 | 2.21 | 3.78 | 1.92 | 2.64 |

| ASM 0° RMS error DST [%] | 8.34 | 7.92 | 6.87 | 9.78 | 8.45 | 4.89 | 12.13 |

| ASM 0° RMS error SST [%] | 9.45 | 4.43 | 16.81 | 5.77 | 9.33 | 9.68 | 10.70 |

| Energy 0° RMS error DST [%] | 3.89 | 3.74 | 3.29 | 4.68 | 3.83 | 2.45 | 5.35 |

| Energy 0° RMS error SST [%] | 3.85 | 1.92 | 6.50 | 2.52 | 4.62 | 3.88 | 3.66 |

| Entropy 0° RMS error DST [%] | 0.79 | 0.83 | 0.65 | 0.41 | 1.20 | 0.68 | 0.94 |

| Entropy 0° RMS error SST [%] | 1.01 | 0.46 | 1.39 | 0.57 | 1.35 | 1.22 | 1.09 |

| Mean 0° RMS error DST [%] | 1.13 | 1.12 | 0.88 | 1.25 | 1.55 | 0.88 | 1.08 |

| Mean 0° RMS error SST [%] | 1.49 | 0.87 | 1.84 | 1.12 | 1.81 | 1.36 | 1.97 |

| Variance 0° RMS error DST [%] | 5.57 | 6.12 | 4.53 | 3.10 | 8.96 | 6.34 | 4.39 |

| Variance 0° RMS error SST [%] | 7.77 | 4.69 | 10.66 | 3.34 | 10.58 | 10.19 | 7.18 |

| Correlation 0° RMS error DST [%] | 2.53 | 2.55 | 2.17 | 1.57 | 4.66 | 2.10 | 2.11 |

| Correlation 0° RMS error SST [%] | 3.36 | 1.59 | 2.95 | 2.89 | 5.73 | 4.03 | 2.95 |

| (b): Inter-reader reproducibility of DST | |||||||

| Mean T2 RMS error [%] | 1.57 | 1.39 | 1.86 | 1.63 | 1.45 | 1.22 | 1.85 |

| Mean T2 absolute error [ms] | 0.53 | 0.48 | 0.60 | 0.60 | 0.49 | 0.40 | 0.62 |

| Superficial layer mean T2 RMS error [%] | 2.02 | 1.45 | 2.17 | 2.12 | 2.75 | 1.61 | 2.04 |

| Superficial layer mean T2 absolute error [ms] | 0.72 | 0.52 | 0.74 | 0.83 | 0.95 | 0.56 | 0.70 |

| Deep layer mean T2 RMS error [%] | 2.17 | 2.07 | 2.74 | 1.85 | 2.56 | 1.59 | 2.19 |

| Deep layer mean T2 absolute error [ms] | 0.69 | 0.67 | 0.85 | 0.65 | 0.79 | 0.47 | 0.74 |

| Contrast 0° RMS error [%] | 4.89 | 4.01 | 8.02 | 3.70 | 4.49 | 4.68 | 4.46 |

| Dissimilarity 0° RMS error [%] | 2.28 | 1.89 | 3.80 | 1.77 | 1.81 | 2.41 | 2.03 |

| Homogeneity 0° RMS error [%] | 4.68 | 3.97 | 6.38 | 5.69 | 4.56 | 4.38 | 3.07 |

| ASM 0° RMS error [%] | 15.59 | 8.80 | 15.92 | 22.88 | 14.73 | 16.54 | 14.65 |

| Energy 0° RMS error [%] | 6.54 | 4.29 | 6.28 | 8.72 | 6.43 | 6.98 | 6.56 |

| Entropy 0° RMS error [%] | 1.42 | 1.18 | 1.64 | 1.52 | 1.18 | 1.38 | 1.62 |

| Mean 0° RMS error [%] | 1.77 | 1.39 | 1.87 | 2.23 | 1.63 | 1.86 | 1.65 |

| Variance 0° RMS error [%] | 4.03 | 2.34 | 6.59 | 2.55 | 3.83 | 4.23 | 4.62 |

| Correlation 0° RMS error [%] | 2.55 | 2.16 | 3.76 | 2.41 | 2.64 | 2.35 | 1.98 |

Printed in bold: highest error value in each line.

DST and SST errors for laminar analysis were higher in the deep cartilage layer (2.53% vs 3.19%) than in the superficial cartilage layer (1.81% vs 2.58%). Highest absolute error values for laminar analysis using DST and SST were observed in the medial tibia compartment (1.24 ms vs 1.90 ms for the superficial cartilage layer and 1.13 ms vs 2.03 ms for deep cartilage layer). Texture parameters entropy and mean showed the lowest reproducibility errors of all texture parameters for DST and SST (0.79% vs 1.01%, respectively 1.13% vs 1.49%), while contrast and ASM had the highest reproducibility errors (7.26% vs 9.53%, respectively 8.34% vs 9.45%). Similar to mean T2 and laminar analysis, highest error values were mostly found in the medial tibia compartment.

Inter-reader variance for DST

Inter-reader comparison did not show significantly different durations for segmentations and T2 measurements of one knee with DST: reader 1 (TB) required 62 ± 3 min and reader 2 (CM-H) 61 ±3 min (P> 0.05).

An average difference of 0.29 ± 0.74 ms for mean T2 values was computed for the two readers with DST. The Bland–Altman plot indicated good agreement between the two readers (Fig. 1). Reader 1 obtained on average slightly higher mean T2 values than reader 2. However, differences were not statistically significant (P > 0.05). Inter-reader reproducibility errors for T2 measurements using DST are listed in Table Ib, combined and separately for each compartment. Averaged over all six compartments, inter-reader reproducibility error for mean T2 amounted 1.57%, respectively 0.53 ms.

Higher error values were obtained for laminar analysis with 2.02% (0.72 ms) in the superficial cartilage layer and 2.17% (0.69 ms) in the deep cartilage layer. Entropy and mean showed the best inter-reader reproducibility of all texture analysis parameters (1.42%, respectively 1.77%), whereas ASM had the worst reproducibility (15.59%).

Future application of the novel segmentation technique

T2 relaxation time mapping is sensitive to a wide range of water interactions in tissue and in particular depends on the content, orientation and anisotropy of collagen. This parameter was therefore included in the OAI MR protocol and will allow thorough investigation of T2 in relation to prevalence and evolution of cartilage degeneration and OA6. Most knee cartilage segmentation techniques used for T2 quantifications were primarily developed for cartilage volume measurements. The superimposition of the segmentations on T2 maps is time consuming due to manual alignment to avoid contamination with joint fluid and bone. This segmentation procedure is challenging for researchers who evaluate exclusively T2 relaxation times and makes analysis of large datasets not feasible. We presented a novel DST for T2 measurements. Given the good agreement of DST and SST in the Bland–Altman plots, DST can be recommended for T2 measurements in large clinical trials like the OAI. In this study, we used this technique not only for mean T2 but also for laminar and texture analysis and found good reproducibilities.

To date, very limited data are available regarding the reproducibility of mean T2 measurements in cartilage13,14. Koff et al. segmented manually patellar cartilage in the first, respectively last echo of a multiecho sequence14. They reported intra-reader (inter-reader) reproducibility errors of 1.9% (3.3%) for mean T2 measurements. Their intra-reader (inter-reader) reproducibility errors for superficial, intermediate and deep cartilage layer amounted up to 3.1% (5.0%). We obtained similar error values for mean T2 and laminar analysis in our study. Glaser et al. examined the reproducibility of T2 relaxation time measurements in the patella of 10 human healthy volunteers and used a SST analogue technique13. They calculated a precision error of 3–7% for mean T2 and of 6–29% for superficial, intermediate and deep cartilage layer mean T2. These error values are higher compared to our study. However, they used imaging at 1.5T compared to 3T in our study and also calculated their reproducibility errors from seven replicate scans.

To the best of our knowledge, no reproducibility errors have been published for texture analysis of T2 relaxation time maps. Texture analysis showed promising results8,9 and we observed acceptable reproducibility errors for most texture parameters in our study. The reproducibility errors for ASM were elevated compared to those of the other texture parameters due to the nature of the equation that defines ASM. ASM is calculated by squaring the probability that two pixels are neighbouring, and summing these squared probabilities over all pixels. Therefore reproducibility errors for ASM can be higher compared to e.g., entropy, which is not defined by an exponent.

Reproducibility was not determined in replicate scans, which is a limitation of this study. This reproducibility is expected to be higher, but replicate scans were not available from the OAI dataset at the time of this study. Given that numerous future research projects will be based on the longitudinal OAI cohort study with 4,796 participants, a preliminary assessment of the reproducibility of the T2 measurements is desperately needed. This study takes the first step to critically evaluate these, future studies need to address the reproducibility of replicate scans. Further limitations such as scanner calibration of the different centres are addressed in the OAI MRI quality assurance process15.

Given the advances in imaging and the new techniques, while manual and semi-manual segmentation may not be novel, the context in using these techniques in this setting is a novel approach. One of the major shortcomings of T2 techniques is a compartment specific segmentation. So far techniques have been very time consuming, which makes development of segmentation techniques that requires less time very important.

In conclusion, fast cartilage segmentation techniques are key to clinically apply T2 measurements. We developed a novel fast knee cartilage segmentation technique for T2 measurements that can be recommended for large clinical trials like the OAI.

Acknowledgement

We thank statistician Petra Heinrich (Institut für Medizinische Statistik und Epidemiologie, Technische Universität München) for her advisory function in the statistical analysis.

The OAI is a public–private partnership comprised of five contracts (N01-AR-2–2258; N01-AR-2–2259; N01-AR-2–2260; N01-AR-2–2261; N01-AR-2–2262) funded by the National Institutes of Health, a branch of the Department of Health and Human Services, and conducted by the OAI Study Investigators. Private funding partners include Merck Research Laboratories; Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation, GlaxoSmithKline; and Pfizer, Inc. Private sector funding for the OAI is managed by the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health. This manuscript was prepared using an OAI public use dataset and does not necessarily reflect the opinions or views of the OAI investigators, the NIH, or the private funding partners.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

No conflict of interest for any authors (Christoph Stehling, Thomas Baum, Christina Mueller-Hoecker, Hans Liebl, Julio Carballido-Gamio, Gabby B. Joseph, Sharmila Majumdar, Thomas M. Link).

References

- 1.Peterfy CG, Schneider E, Nevitt M. The osteoarthritis initiative: report on the design rationale for the magnetic resonance imaging protocol for the knee. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2008;16(12):1433–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith HE, Mosher TJ, Dardzinski BJ, Collins BG, Collins CM, Yang QX, et al. Spatial variation in cartilage T2 of the knee. J Magn Reson Imaging 2001;14(1):50–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maier CF, Tan SG, Hariharan H, Potter HG. T2 quantitation of articular cartilage at 1.5 T. J Magn Reson Imaging 2003;17(3): 358–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Raya JG, Dietrich O, Horng A, Weber J, Reiser MF, Glaser C. T2 measurement in articular cartilage: impact of the fitting method on accuracy and precision at low SNR. Magn Reson Med 2010;63(1):181–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eckstein F, Ateshian G, Burgkart R, Burstein D, Cicuttini F, Dardzinski B, et al. Proposal for a nomenclature for magnetic resonance imaging based measures of articular cartilage in osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2006;14(10):974–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stehling C, Liebl H, Krug R, Lane NE, Nevitt MC, Lynch J, et al. Patellar cartilage: T2 values and morphologic abnormalities at 3.0-T MR imaging in relation to physical activity in asymptomatic subjects from the osteoarthritis initiative. Radiology 2010;254(2):509–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carballido-Gamio J, Blumenkrantz G, Lynch JA, Link TM, Majumdar S. Longitudinal analysis of MRI T(2) knee cartilage laminar organization in a subset of patients from the osteoarthritis initiative. Magn Reson Med 2010;63(2): 465–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carballido-Gamio J, Stahl R, Blumenkrantz G, Romero A, Majumdar S, Link TM. Spatial analysis of magnetic resonance T1rho and T2 relaxation times improves classification between subjects with and without osteoarthritis. Med Phys 2009;36(9):4059–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blumenkrantz G, Stahl R, Carballido-Gamio J, Zhao S, Lu Y, Munoz T, et al. The feasibility of characterizing the spatial distribution of cartilage T(2) using texture analysis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2008;16(5):584–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carballido-Gamio J, Bauer J, Lee KY, Krause S, Majumdar S. Combined image processing techniques for characterization of MRI cartilage of the knee. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc 2005;3:3043–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carballido-Gamio J, Bauer JS, Stahl R, Lee KY, Krause S, Link TM, et al. Inter-subject comparison of MRI knee cartilage thickness. Med Image Anal 2008;12(2):120–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gluer CC, Blake G, Lu Y, Blunt BA, Jergas M, Genant HK. Accurate assessment of precision errors: how to measure the reproducibility of bone densitometry techniques. Osteoporos Int 1995;5(4):262–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Glaser C, Mendlik T, Dinges J, Weber J, Stahl R, Trumm C, et al. Global and regional reproducibility of T2 relaxation time measurements in human patellar cartilage. Magn Reson Med 2006;56(3):527–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koff MF, Parratte S, Amrami KK, Kaufman KR. Examiner repeatability of patellar cartilage T2 values. Magn Reson Imaging 2009;27(1):131–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schneider E, NessAiver M, White D, Purdy D, Martin L, Fanella L, et al. The osteoarthritis initiative (OAI) magnetic resonance imaging quality assurance methods and results. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2008;16(9):994–1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]