Significance

Toxin–antitoxin (TA) systems are pairs of genes found throughout bacteria that function in DNA maintenance and bacterial survival. The toxins in these systems function by inactivating critical cell processes like protein synthesis. This work describes a TA system found in 17% of all sequenced bacteria. A high-resolution crystal structure and an array of biochemical tests revealed that this toxin targets an essential enzyme in nucleotide biosynthesis, a unique way in which TA systems can halt bacterial growth.

Keywords: toxin–antitoxin system, ADP-ribosylation, posttranslational modification

Abstract

Toxin–antitoxin (TA) systems interfere with essential cellular processes and are implicated in bacterial lifestyle adaptations such as persistence and the biofilm formation. Here, we present structural, biochemical, and functional data on an uncharacterized TA system, the COG5654–COG5642 pair. Bioinformatic analysis showed that this TA pair is found in 2,942 of the 16,286 distinct bacterial species in the RefSeq database. We solved a structure of the toxin bound to a fragment of the antitoxin to 1.50 Å. This structure suggested that the toxin is a mono-ADP-ribosyltransferase (mART). The toxin specifically modifies phosphoribosyl pyrophosphate synthetase (Prs), an essential enzyme in nucleotide biosynthesis conserved in all organisms. We propose renaming the toxin ParT for Prs ADP-ribosylating toxin and ParS for the cognate antitoxin. ParT is a unique example of an intracellular protein mART in bacteria and is the smallest known mART. This work demonstrates that TA systems can induce bacteriostasis through interference with nucleotide biosynthesis.

Our understanding of toxin–antitoxin (TA) systems has progressed significantly since their identification nearly 35 y ago. In the pioneering work, ccdAB was shown to enhance the stability of a mini-F plasmid in Escherichia coli by killing daughter cells lacking the plasmid and also established that the ccdA genetic element could provide an antidote for the postsegregational killing (PSK) of ccdB (1). An investigation into the E. coli R1 plasmid revealed a similar system hok/sok that also improved plasmid stability, where again one element, sok, could neutralize the PSK activity of the other, hok (2). Results such as these led to the hypothesis that the role of such genetic regions was to ensure the inheritance of plasmids during cell division. It was later discovered, however, that these systems resided not only in plasmids but also on bacterial chromosomes and that, while not conferring replicon stability, they may play an important role in regulating cell growth (3–5). Further investigations into bacterial TA systems have also implicated them in biofilm growth and persister formation. The toxin gene mqsR was first shown to be up-regulated in E. coli biofilms and later confirmed to promote biofilm formation through regulation of quorum sensing (6, 7). One of the most ubiquitous TA systems, hipBA, was the first to be implicated in persister formation; the well-characterized mutant hipA7 was shown to increase E. coli persistence up to 1,000-fold, due to a weakened interaction with its antitoxin (8). Various other toxins have also been implicated in biofilm and persister formation, including RelE, YafQ, and MazF (9). As the importance of biofilms and persisters in clinical settings grows, the study of TA systems provides an avenue for better understanding the mechanisms driving these processes, as well as a possible path to intervention.

Although most downstream effects of these toxins are generally similar (bacteriostasis or cell death), the methods by which these systems work are remarkably diverse. TA systems are broadly grouped into six classes, type I through VI, based on the nature of the TA interaction, although type I and II comprise most known TA systems and have been extensively studied. Type I toxins are typified by an RNA-level TA interaction, where an antisense RNA binds toxin mRNA to inhibit its translation. Type II TA systems function via protein–protein interactions, where binding of the antitoxin to the toxin inhibits its activity (10). Of the two earliest known TA systems mentioned above, hok/sok is an example of a type I system, while ccdAB is type II (11, 12). Upon translation, type I toxins are small, hydrophobic peptides that lead to cell lysis through disruption of the plasma membrane. Type II toxins, however, function through a variety of mechanisms. A large group of these are endoribonucleases that cleave RNA in either a ribosome-dependent or independent manner. The well-studied HigB, RelE, and MazF toxins, among many others, all fall into this group (13–15). Beyond these, however, there is much variation. HipA phosphorylates glutamyl-tRNA synthetase (GltX), inactivating it, while CcdB engages in gyrase-mediated double-stranded DNA cleavage (16, 17). Another toxin, FicT, also interferes with DNA gyrase, but rather by inactivation through adenylation (18). More recently, DarT was found to ADP-ribosylate single-stranded DNA (19). The continued discovery of new toxins like DarT emphasizes the role of TA systems in cell biology.

Type II TA systems are quite prevalent throughout bacterial genomes. In a comprehensive analysis by Makarova et al. (20) in 2009, of the 750 reference genomes searched, putative type II TA systems were found in 631, with on average 10 loci in each hit (6,797 total). The number of occurrences in a single genome can be much larger, however; the deadly pathogen Mycobacterium tuberculosis has over 88 TA loci in its genome, while the soil bacterium and plant symbiont Sinorhizobium meliloti contains an astounding 211 predicted type II loci (21, 22). Makarova et al. proposed the existence of 19 new putative type II TA pairs, including 12 new toxins and antitoxins, again highlighting the variety that exists within the type II class. To organize the rapidly increasing amount of data available, the TA database was created in 2010 and is an invaluable resource in parsing what we know about these systems (23).

Of the 19 predicted TA systems, one stood out to us in particular. The COG5654 (RES domain)-COG5642 TA family is one of five putative TA systems from this paper where both components were uncharacterized. We had encountered this pair in genome mining for natural products studied by our laboratory and were intrigued by how poorly understood it was considering how widespread it appeared to be; it was present in 250 of the 750 genomes analyzed by Makarova et al. Following its identification in 2009, we found only one study that examined the putative COG5654–COG5642 TA pair, a genetic study on S. meliloti. This organism has 211 putative TA loci as mentioned above, with roughly 100 of these on the organism’s two megaplasmids. The authors demonstrated through a series of genetic deletions that only four of these were actively functioning as TA systems, including a COG5654–COG5642 locus, which confirmed the hypothesis put forth in Makarova’s work (22).

Here, we report a detailed physiological, structural, and biochemical study of the COG5654–COG5642 TA system, starting with a computational approach that demonstrates its prevalence in bacterial genomes. We confirm that it functions as a TA system in E. coli, an organism with no native COG5654–COG5642 pairs, suggesting a target well-conserved in bacteria. We then report a high-resolution crystal structure of the protein complex, which includes the structure of an RES domain protein. Solving this structure allowed us to determine that the toxin is a mono-ADP-ribosyltransferase (mART). We further show, both in vivo and in vitro that the toxin ADP-ribosylates phosphoribosyl pyrophosphate synthetase (Prs), an essential enzyme involved in nucleotide biosynthesis. This report expands the set of bacteriostatic mechanisms employed by TA systems to include protein-modifying ADP-ribosylation.

Results

Sphingobium sp. YBL2 Bears Multiple COG5654–COG5642 TA Systems.

Our investigation into Sphingobium sp. YBL2 began when a genome-mining algorithm developed in-house for discovering new lasso peptide producers identified this organism as having two lasso peptide gene clusters of interest (24). It was immediately evident that one of these gene clusters differed from the expected architecture, containing within it genes encoding two hypothetical proteins, yblI and yblJ (Fig. 1A). A BLAST of these sequences revealed them to be a COG5654–COG5642 putative TA pair, first identified in a computational study in 2009 and later confirmed to function as a TA pair in S. meliloti (20, 22). To our knowledge, this is the last published work on this TA family.

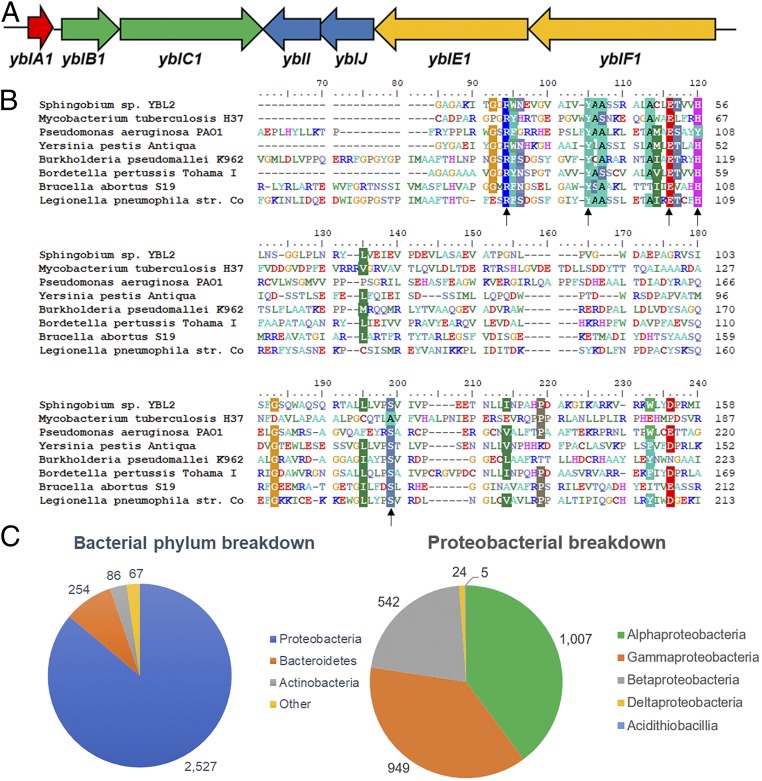

Fig. 1.

Bioinformatic analysis of the COG5654–COG5642 TA family. (A) Lasso peptide gene cluster containing the TA pair studied here (yblIJ). (B) Sequence similarity of the COG5654 toxin from Sphingobium sp. YBL2 and several bacterial pathogens. Residues with >70% similarity are shaded. Similarity is clustered around the strictly conserved Arg-31, Tyr-41, and Glu-52 residues. (C) Distribution of this TA family among bacterial phyla is shown at Left; Proteobacteria have by far the largest number of examples of this TA system. A further breakdown within Proteobacteria is shown at Right.

COG5654 toxins contain a roughly 150-aa RES domain, named for a highly conserved Arg-Glu-Ser motif. In addition, the domain also features two strongly conserved Tyr and His residues. An alignment of the Sphingobium sp. YBL2 toxin with homologs from various pathogens illustrates that outside of these and neighboring residues, there is little shared sequence similarity (Fig. 1B). The function of the RES domain is unknown, and a BLAST of these toxins offers no homologous proteins with known activities. COG5642 antitoxins meanwhile have a roughly 60-aa C-terminal domain of unknown function, DUF2384, which follows an N-terminal DNA binding domain. Antitoxins from type II TA modules generally have C-terminal toxin binding domains, making this a likely function of DUF2384 (25).

As Fig. 1B shows, COG5654 toxins appear in the genomes of many pathogenic bacteria. To better understand the prevalence of the COG5654–COG5642 system, we devised code (Dataset S1) that searched all Refseq genomes for genes encoding an RES domain protein downstream of a DUF2384 protein. The results of this search are summarized in Fig. 1C. Of the 108,787 bacterial Refseq genomes searched, there are 15,354 organisms that contain at least one copy of this TA family (14.1%) and 16,964 total instances. Some organisms contained many copies, with Spirosoma spitsbergense and Spirosoma luteum having 12 and 10, respectively. Sphingobium sp. YBL2 itself has five loci, three on its chromosome and two on plasmids. An alignment of the five toxins reveals high identity (45%) and similarity (53%) between two of the chromosomal toxins, but little between the remaining three, including the one we originally identified (SI Appendix, Table S1).

To avoid overrepresentation of bacteria with many strains characterized (e.g., M. tuberculosis or Bordetella pertussis), we consolidated each into a single species entry. After doing so, the TA family was found in 2,942 unique bacterial species of 16,826 (17.5%). Within these, we found the COG5654–COG5642 pair in 15 bacterial phyla, although it was by far the most abundant and overrepresented in Proteobacteria, occurring in 2,527 of 7,483 species (33.8%) (Table 1). The phyla also included Verrucomicrobia, Deinnococcus-Thermus, Spirochaetes, Planctomycetes, and Firmicutes, all of which were not observed earlier in Makarova et al. Within Bacteroidetes, we identified 254 species and noticed a remarkably high overrepresentation in the Chitinophagia, Cytophagia, and Sphingobacteriia classes, occurring in 27/33 (81.8%), 90/115 (78.3%), and 45/65 (69.2%) organisms, respectively. There were 86 Actinobacteria identified, including 55 Mycobacterial species. Curiously, of the 3,406 Firmicutes genomes, only a single instance (0.03%) of this TA family was found in Exiguobacterium sp. S17, which may warrant further investigation. Most Proteobacterial species were Alpha- (1,007/2,244, 44.9%), Beta- (542/1,167, 46.4%), and Gammaproteobacteria (949/3,617, 26.2%), with many from orders of known pathogens, such as Burkholderiales, Legionellales, and Pseudomonadales. A selected and full breakdown of the results can be found in SI Appendix, Table S2 and Dataset S2, respectively. The TA family was not observed in any archaeal genomes, in agreement with Makarova’s findings in 2009. The results of our search confirm that the COG5654–COG5642 system is widespread in bacteria, even more so than originally thought.

Table 1.

Breakdown of bacterial Phyla containing the COG5654–COG5642 TA family

| TA-bearing species | Unique species searched | Percentage, % | Phylum |

| 14 | 27 | 51.85 | Acidobacteria |

| 86 | 3,469 | 2.48 | Actinobacteria |

| 254 | 1,334 | 19.04 | Bacteroidetes |

| 1 | 8 | 12.50 | Balneolaeota |

| 6 | 17 | 35.29 | Chlorobi |

| 25 | 302 | 8.28 | Cyanobacteria |

| 11 | 62 | 17.74 | Deinococcus-Thermus |

| 1 | 3,406 | 0.03 | Firmicutes |

| 2 | 3 | 66.67 | Gemmatimonadetes |

| 1 | 1 | 100 | Tectomicrobia |

| 3 | 41 | 7.32 | Planctomycetes |

| 2,527 | 7,483 | 33.77 | Proteobacteria |

| 1 | 5 | 20 | Rhodothermaeota |

| 2 | 128 | 1.56 | Spirochaetes |

| 6 | 40 | 15 | Verrucomicrobia |

The COG5654–COG5642 Pair Functions as a TA System in E. coli.

To more easily study the COG5654–COG5642 TA pair, we moved the component genes from Sphingobium sp. YBL2 into E. coli. Although laboratory strains of E. coli harbor dozens of TA loci, the COG5654–COG5642 pair is not one of them, and thus, our first aim was to confirm that this system can still function in this nonnative organism (10, 25). The toxin was expressed from a low-copy pBAD33 plasmid (26), and upon induction, exerted a bacteriostatic effect as measured by OD600 (Fig. 2A). We also examined cell viability by colony forming unit (cfu) count. One hour after toxin induction, the cfu count had decreased dramatically, although it began to increase at 3 h (SI Appendix, Fig. S1). This is similar to what was observed with RelE, a well-known bacteriostatic toxin (27). Coexpression of the COG5642 antitoxin restored the normal growth phenotype, confirming that this nonnative TA system functions normally in E. coli (Fig. 2A).

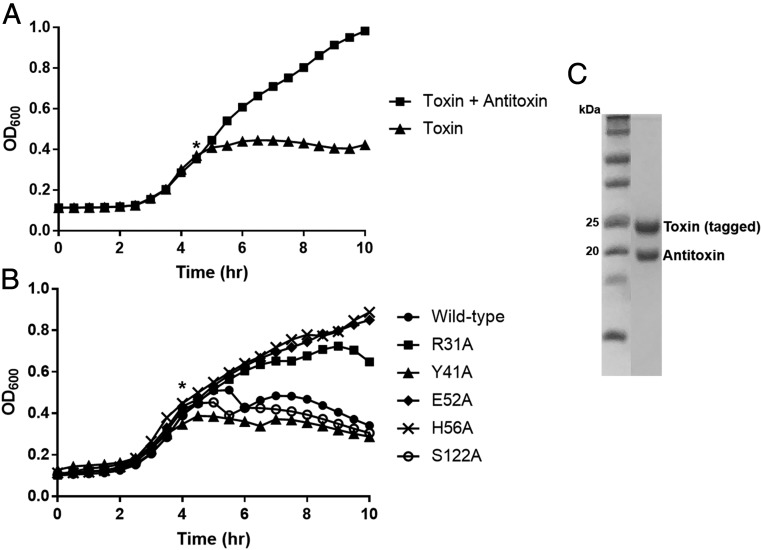

Fig. 2.

Heterologous expression in E. coli of the Sphingobium sp. YBL2 COG5654–COG5642 TA system. (A) Growth curves showing the effect of toxin expression with and without antitoxin induction 30 min prior. The toxin exerts a bacteriostatic effect that is prevented by antitoxin coexpression. (B) Growth curves of toxin variants with alanine substitutions for five highly conserved amino acids. R31A, E52A, and H56A variants are all nontoxic. Asterisks in A and B indicate the timepoint of induction of toxin. (C) SDS/PAGE gel from a native purification of N-terminally His-tagged toxin coexpressed with untagged antitoxin. Its interaction with the toxin results in copurification despite the lack of a His tag.

We then performed an alanine scan on the highly conserved residues of the RES domain described in the previous section. Substitution of alanine for Arg-31, Glu-52, and His-56 resulted in the elimination of the toxic phenotype (Fig. 2B). Conversely, substitution of alanine for Tyr-41 and Ser-122 had no effect on toxicity (Fig. 2B). While this is surprising in both cases, it is less so for Ser-122, where the change is more conservative. Indeed, the alignment from Fig. 1B reveals that the corresponding amino acid in M. tuberculosis is itself alanine. We subsequently examined the mildly conserved Ser-21, 44, and 45 to exhaust candidates for the namesake serine in the “RES” domain, but these substitutions also had no effect on toxicity (SI Appendix, Fig. S2).

To confirm that the loss of toxicity of the R31A, E52A, and H56A toxins was not driven by low expression, we cloned these variants into high-copy pQE80 vectors. The R31A toxin expressed at a high level as judged by SDS/PAGE and no growth defect was observed, while the E52A toxin recovered the toxic phenotype, likely due to the increased copy number of pQE80 relative to pBAD33 (SI Appendix, Fig. S3) (28). Neither the wild-type nor the H56A toxin could be cloned into pQE80. This suggests that there is still residual toxicity of the H56A variant due to leaky expression. Taken together, these results indicate that while Glu-52 and His-56 play a role in toxicity, Arg-31 is of paramount importance.

Crystallography Reveals Structural Similarity to mARTs.

With no reasonable starting point for elucidating the function of the COG5654 toxin, we instead set our sights on determining its structure, hoping to later infer its activity from this result. Because the wild-type toxin can only be made at a high level when expressed alongside the cognate antitoxin, we set out to crystallize the protein complex first. For easily controlled coexpression, we cloned toxin and antitoxin into a pRSFduet vector. The complex was expressed for 3 h at 37 °C before native purification, with typical yields of >5 mg/L. In our experimental setup, although only the toxin bears an affinity tag, the untagged antitoxin copurifies due to strong protein–protein interactions characteristic of TA systems (Fig. 2C) (29, 30). Furthermore, the proteins elute as a single peak during size exclusion chromatography, with a retention time indicating a 2:2 stoichiometry (a TA dimer) (SI Appendix, Fig. S4).

This purified TA complex had a solubility limit of 1 mg/mL and was unsuitable for crystallization. The general understanding of TA systems is that the antitoxin is inherently less stable than the toxin, demonstrated previously in vitro by the selective total degradation by trypsin of the VapB antitoxin from a folded VapBC complex (10, 31). We adapted this procedure for our system and observed by LC/MS that even after overnight trypsin treatment, a 72-aa C-terminal antitoxin fragment was intact despite the existence of multiple possible cut sites (SI Appendix, Fig. S5). This, we hypothesized, was due to extensive TA contacts making the remaining sites inaccessible. We constructed a series of antitoxin truncations that left the C-terminal portion intact and found that even the shortest antitoxin fragment we tested (amino acids 99–159) could bind and neutralize toxin when coexpressed (SI Appendix, Fig. S6). Upon trypsin digestion, the toxin lost only its two most C-terminal amino acids. This trypsin-treated complex exhibited solubility greater than 10 mg/mL and showed promise in crystal screening.

The trypsin-digested toxin contains only a single methionine (Met) residue. To increase Met content for selenomethionine (SeMet) substitution and single-wavelength anomalous dispersion (SAD), we used a L48M toxin variant, which we confirmed retained toxicity (SI Appendix, Fig. S7). We successfully crystallized the trypsin-treated SeMet-substituted L48M TA complex and determined its structure to 1.55 Å using SAD (PDB ID code: 6D0I). The complex crystallized in the P1 space group with unit cell dimensions of 41.98 Å, 51.32 Å, and 57.94 Å. From this, we subsequently determined the structure of the trypsin-treated wild-type complex to 1.50 Å (PDB ID code: 6D0H; Fig. 3A). A full description of data collection and refinement parameters can be found in SI Appendix, Table S3. The complex crystallizes as a dimer, where the C terminus of each antitoxin is buried in a putative toxin active site cleft housing all five highly conserved residues discussed above (Fig. 3B).

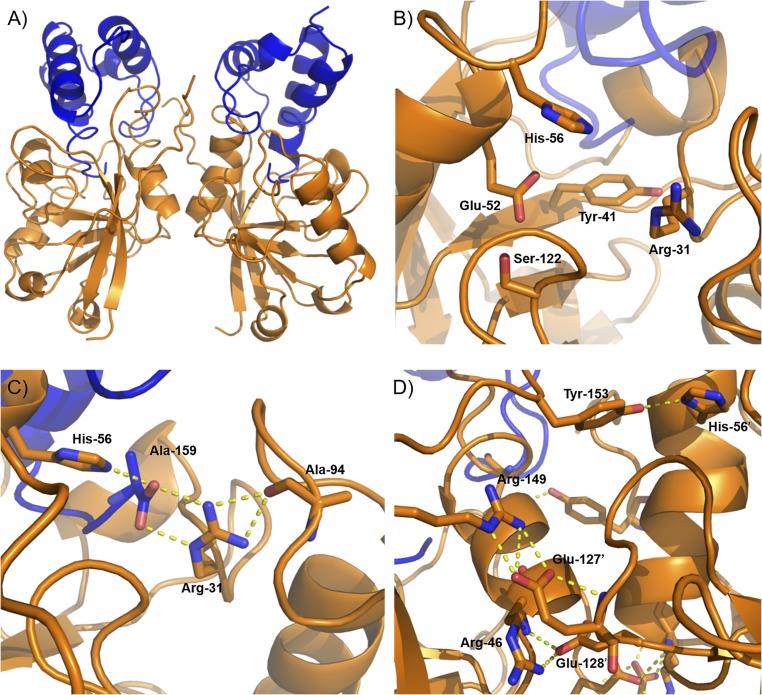

Fig. 3.

Crystal structure of the trypsin-treated TA complex. (A) Overall structure of the TA dimer (toxin, orange; antitoxin, blue) determined to 1.50-Å resolution. (B) Close-up of the putative active site. The five highly conserved residues examined in the alanine scan are highlighted. (C) Bonding network of the critical toxin His-56 and Arg-31. The arginine sidechain forms salt bridges with the C-terminal carboxyl of the antitoxin, which establishes a rotamer that also results in hydrogen bonding with the toxin’s own Ala-94. (D) Structure of the toxin-toxin interface. Shown are the intersubunit salt bridges between Arg-46 and Glu-128′ and Arg-149 and Glu-127′, as well as hydrogen bonding between Tyr-153 and the functionally important His-56′.

We used PDBePISA to analyze the interactions between TA complex subunits (32). The surface area of the TA interface is 1,369.6 Å2 with an average ΔiG (free energy gain on interface formation, excluding hydrogen bonds and salt bridges) of −13.7 kcal/mol, indicating a strong affinity between the two proteins. Extensive hydrogen bonding occurs between 13 antitoxin and 14 toxin residues. Interestingly, salt bridging occurs between the C-terminal carboxyl of the antitoxin and both the His-56 and critical Arg-31 of the toxin (Fig. 3C). This interaction places Arg-31 in a conformer directed away from the active site, also engaging it in hydrogen bonding with the toxin Ala-94 backbone oxygen. The strength of the TA interface is illustrated experimentally by urea-induced dissociation, where purified TA complex required incubation in 6 M urea to separate the component proteins (SI Appendix, Fig. S8).

A significant interface also exists between the two toxin subunits, with an interfacial surface area of 762.2 Å2 and ΔiG of −7.1 kcal/mol. The network of hydrogen bonding is less extensive, but notably there is an interaction between the highly conserved His-56 of one toxin subunit and Tyr-153 of the other (Fig. 3D). Salt bridging between the toxin subunits occurs at Glu-127 and Glu-128 of one subunit and Arg-46 and Arg-149 of the other (Fig. 3D). To determine if these salt bridges are necessary for toxicity, we constructed a series of mutations at the two glutamate residues. Single mutations to alanine had little effect on toxicity, but a double mutation to even sterically similar glutamines rendered the protein nontoxic (SI Appendix, Fig. S9). Thus, although a single pair of salt bridges can be disrupted, the presence of at least one is critical for interfacial integrity and proper function. This strongly supports the idea of the toxin working as a dimer in vivo. Lastly, there is no discernable interface between the two antitoxin fragment subunits, suggesting these two exclusively interact with the toxins they bind.

Following the elucidation of the complex structure, we employed the DALI structural similarity server to determine if any similarity to known proteins existed (33). The top result from this search was the catalytic domain of diphtheria toxin from Corynebacterium diphtheriae, which had a Z-score of 7.0 and rmsd of 3.0 Å, indicating some structural similarity despite only 11% sequence identity (SI Appendix, Fig. S10). Diphtheria toxin is a secreted mART capable of cleaving NAD+ into nicotinamide and ADP-ribose. It transfers the latter to a posttranslationally modified histidine, diphthamide, in eukaryotic elongation factor-2 (EF-2), which inhibits protein synthesis (34). Other mARTs such as cholix toxin from Vibrio cholerae and exotoxin A from Pseudomonas aeruginosa also exhibited strong Z-scores (SI Appendix, Table S4) (35, 36), and we hypothesized based on these results that the COG5654 toxin is also a mART. Of note, the results also contain several poly-ADP-ribosyltransferases (pARTs) including tankyrase-1 and -2, although these generally have lower Z-scores than the mARTs (Dataset S3).

Phosphoribosyl Pyrophosphate Synthetase Is a Putative Toxin Target.

To test for mART activity, we required an isolated toxin sample. As described in the previous section, this could not be achieved by a trypsin digestion due to the strong interactions between toxin and antitoxin. A typical procedure for toxin isolation for many TA families involves complex denaturation, toxin repurification, and refolding by dialysis (16, 29, 30). We adapted this method for our system, noting that the toxin would only successfully refold when arginine was present in the dialysis buffer (37). When dialysis was complete, arginine could then be removed without causing toxin aggregation.

As a first test of mART activity, we incubated 1 µM toxin with 1 mM NAD+. mARTs such as diphtheria toxin and iota toxin from Clostridium perfringens have been shown to exhibit weak NADase activity in the absence of a protein target (38–40). We observed not only a decrease in NAD+ and increase in free ADP-ribose, but also the appearance of an ADP-ribosylated toxin (SI Appendix, Fig. S11). A tryptic digest revealed that this modification occurred on a single peptide that contains the important Glu-52 and His-56 residues (SI Appendix, Fig. S11C). Although we are unsure of its significance for this system, auto–ADP-ribosylation is a known regulatory mechanism for several mARTs and may serve a similar function here, regulating toxin activity once disassociated from antitoxin in vivo (41, 42). We repeated this reaction using the inactive R31A toxin variant and observed that after 3 h, toxin ADP-ribosylation had greatly decreased relative to the wild type (SI Appendix, Fig. S12), supporting the idea that the loss of toxicity of the R31A toxin is a result of a loss of transferase activity. The reactions were also carried out with wild-type toxin using an NADP+ substrate, and we observed similar levels of glycohydrolase activity and automodification as for NAD+ (SI Appendix, Fig. S13A). This result was surprising as mARTs generally show high specificity toward NAD+.

Encouraged by these results, we sought to identify a cellular substrate for the toxin. We hypothesized based on toxin self–ADP-ribosylation that the target was a protein and not a nucleic acid as was recently observed with DarT (19). Here, we employed a pulldown where cell lysates from toxin-expressing cultures were incubated with macro domain protein AF1521 from Archaeoglobus fulgidus and subject to His-tag affinity purification. Macro domain proteins such as AF1521 have been used previously to isolate ADP-ribosylated proteins from complex mixtures such as cell lysates (43, 44). Several proteins were pulled down via this technique, and all were identified after an in-gel tryptic digest, followed by LC/MS and Mascot peptide mass fingerprinting (SI Appendix, Fig. S14). These proteins, YfbG, GlmS, and EF-Tu, are all common contaminants associated with His-tag affinity purifications (45, 46). We were intrigued, however, by the last protein we identified, phosphoribose pyrophosphate synthetase (Prs), which is not a known affinity purification contaminant. Prs is a homohexameric protein encoded by the essential prs gene, which is found in both bacteria and eukaryotes and strictly conserved in all nonparasitic organisms (47). Prs catalyzes the conversion of ribose 5-phosphate to phosphoribose pyrophosphate, a precursor in the synthesis of nucleotides, histidine and tryptophan, NAD+, and NADP+ (48). Its critical position in metabolism and strong conservation across a range of organisms make it a logical target for cellular toxins.

The COG5654 Toxin ADP-ribosylates Prs in Vitro.

We next sought to reconstitute Prs ADP-ribosylation in vitro. Reactions of 10 µM Prs, 5 µM toxin, and 10 mM NAD+ were set up at 37 °C, and the products were analyzed by LC/MS at 3 h and 20 h. After 3 h, about one-third of the Prs was ADP-ribosylated (Fig. 4A). Although most of the modified Prs was singly ADP-ribosylated (∼25% of the total), a small amount of Prs had acquired a second ADP-ribose. When the reaction was run for 20 h, the amount of ADP-ribosylated Prs had increased, with roughly equal amounts of unmodified, singly modified, and doubly modified Prs present (Fig. 4A).

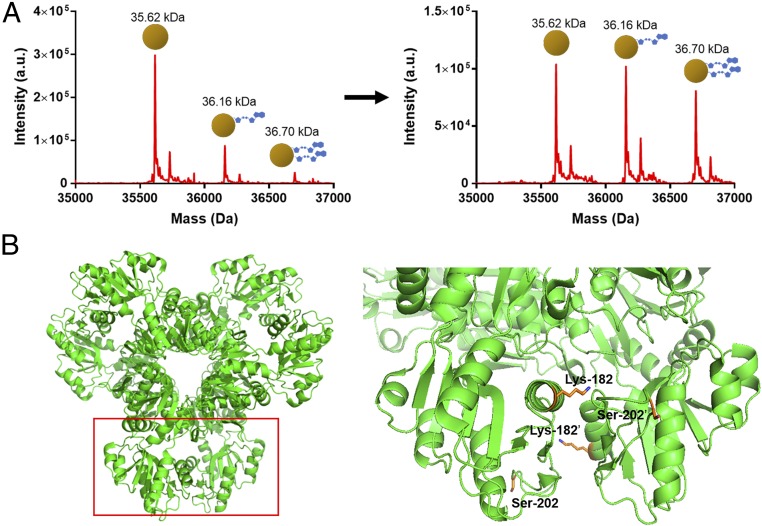

Fig. 4.

In vitro ADP-ribosylation of E. coli Prs. (A) ESI mass spectrometry of the reaction of Prs (10 µM) with toxin (5 µM) and NAD+ (10 mM). After 3 h, conversion to a singly ADP-ribosylated Prs is ∼25%, with a doubly ADP-ribosylated peak beginning to appear. At 20 h, ∼65% of the Prs is ADP-ribosylated, with ∼35% singly modified and ∼30% doubly modified. (B) Crystal structure of the E. coli Prs hexamer (PDB ID code 4S2U). The ADP-ribosylated residues identified by LC/MS2, Lys-182 and Ser-202, are shown in gray. The Lys-182 sidechain is directed toward the Prs active site, while Ser-202 is located on a catalytic flexible loop.

Holding the concentration of Prs constant, we also performed in vitro reactions at lower toxin (1 µM) and/or NAD+ (1 mM) concentrations. This concentration of NAD+ is below the physiological level in E. coli (49). We were interested in both how this would affect the rate of reaction, as well as if these conditions would still drive the formation of doubly ADP-ribosylated Prs. After 3 h, about 10–15% of Prs had been ADP-ribosylated (down from ∼33%) and little to no doubly modified Prs was present. Additionally, the effect was independent of whether toxin or NAD+ (or both) concentration had been lowered (SI Appendix, Fig. S15). By increasing the reaction time to 20 h, singly modified peaks doubled in size, now accounting for ∼25% of total Prs. As with high toxin and NAD+ concentration, doubly modified species showed the most increase from 3 h to 20 h, now present at roughly the same amount as singly modified Prs. This longer time course suggests that the additional modification is not merely a function of high reactant concentration. Also of note, we observed that the extent of toxin auto–ADP-ribosylation decreased in the presence of Prs, supporting the idea that self–ADP-ribosylation may be a form of regulation in the absence of target (SI Appendix, Fig. S16). Collectively, this data shows that the toxin can ADP-ribosylate Prs twice, a surprising result given that mARTs generally ADP-ribosylate only a single amino acid on their target.

To confirm that these Prs modifications are not occurring nonspecifically, we used higher energy collision dissociation (HCD) LC/MS2 to analyze tryptic digests of the in vitro reactions (50). Analysis with Scaffold proteomics software revealed that the majority of ADP-ribosylation occurred at either Lys-182 or Ser-202 of the E. coli Prs, showing that these modifications are specific (Fig. 4B and SI Appendix, Fig. S17). Lys-182 is conserved among many bacterial Prs and has been shown to participate in ATP binding, placing it at the Prs active site (51). The Prs from Sphingobium sp. YBL2 has an aspartic acid (also a mART target) at this position, which is also present in M. tuberculosis and other bacteria, as well as in all three human Prs isozymes (51). A mutation of this residue to histidine in human isozyme one has been implicated in dysregulation in patients with Prs superactivity, suggesting that an ADP-ribose modification could also critically alter Prs in bacteria (52). Ser-202 shows some conservation but, to our knowledge, is not critical for catalytic activity or regulation. It is, however, part of a flexible loop involved in catalysis (53), and its modification could prevent this region from entering a productive conformation. Although the corresponding valine in Sphingobium sp. YBL2 Prs cannot be ADP-ribosylated, a targetable threonine is adjacent. Further investigation into these modifications is necessary, both to determine if one is a preferred substrate and what effect the modification has on Prs activity. Although we wished to repeat these reactions with the Sphingobium sp. YBL2 Prs, the protein expressed poorly in E. coli and coeluted with large quantities of GroEL (SI Appendix, Fig. S18). Based on the toxin’s activity, we propose to rename the RES domain family of toxins to ParT (Prs ADP-ribosylating toxin) and the corresponding antitoxin family to ParS.

Noting ParT’s ability to cleave NADP+, we also attempted to modify Prs with this substrate, but no pADP-ribosylation could be detected (SI Appendix, Fig. S13B). This agrees with what is typically observed for mARTs and demonstrates that here, although there may be some relaxed specificity for glycohydrolysis, transferase activity still requires the traditional NAD+ substrate.

An Inactive Prs Variant Attenuates the ParT-Induced Growth Defect.

To confirm that ParT targets Prs in vivo, we planned to supplement Prs on a plasmid. An analogous experiment with HipA demonstrated that overexpression of its target, GltX, allowed for recovery of normal cell growth (16). It is known, however, that Prs hyperactivity is toxic to human cells (54), and indeed, we observed a growth defect in E. coli when overexpressing the wild-type protein, making direct supplementation of Prs impossible (SI Appendix, Fig. S19A). To overcome this issue, we instead supplied an inactive H131A variant of E. coli Prs, which alters a histidine involved in binding the γ-phosphate of the ATP substrate (55, 56). As expected, overexpression of this H131A Prs caused no negative effects on cell growth (SI Appendix, Fig. S19B). Supplying an inactive Prs is not ideal, but we reasoned that the overexpressed protein could at act as a decoy, with ParT targeting the abundant inactive Prs rather than the productive native enzyme. Although eventually the native Prs would also get modified, we believed this should at least attenuate ParT toxicity.

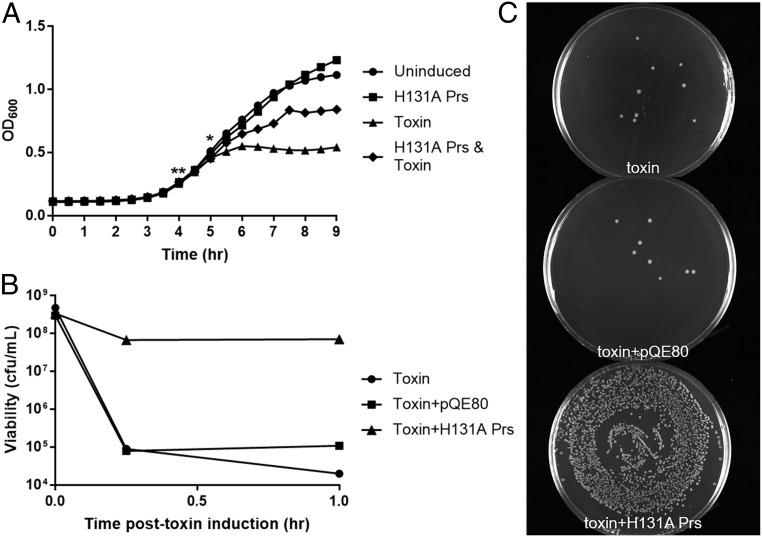

We expressed H131A Prs for 1 h before ParT induction. Rather than the immediate growth arrest that is seen in cultures expressing only ParT, cultures also expressing H131A Prs continued to grow following toxin induction (Fig. 5A). Although growth is slower than in ParT-uninduced cultures, final OD600 is considerably higher in H131A Prs coexpressing cultures than in those expressing the toxin alone (Fig. 5A). This result agrees with our hypothesis that although H131A Prs can mitigate toxicity, it cannot completely overcome it. A similar effect was observed in cultures expressing H131A Prs for only 30 min before ParT induction, but to a lesser degree.

Fig. 5.

Coexpression of ParT with an inactive Prs variant suppresses ParT toxicity. (A) Growth curves of cells coexpressing H131A Prs and ParT. H131A Prs was induced at 4 h (**) and toxin induced 1 h later (*). Cultures that accumulated H131A Prs showed a marked increase in OD600 following toxin induction. (B) Cell viability as measured by cfu count. Within 15 min, cfu count drops dramatically (∼10,000-fold) when cultures express only ParT. In contrast, cultures allowed to accumulate H131A Prs show only mildly decreased viability (∼10-fold). (C) Cfu count 15 min after toxin induction. Cultures were diluted 10,000-fold before 100 µL was plated on LB supplemented with the appropriate antibiotics and grown overnight at 37 °C.

To rule out the other proteins identified in the macro domain pulldown as purely contaminants and not possible ParT targets, we repeated this coexpression with EF-Tu in place of Prs. We chose EF-Tu because of its association with multiple other posttranslational modifications, including phosphorylation, methylation, and acetylation (57–59). Unlike in the case of Prs, expression of EF-Tu for 1 h before ParT induction led to a phenotype that was indistinguishable from cultures expressing ParT only (SI Appendix, Fig. S20). This result strongly suggests that EF-Tu is not a target of ParT.

To confirm that the change in OD600 observed in cultures coexpressing toxin and H131A Prs was not due to cell morphology changes or effects unrelated to ParT, we also examined cell viability. Cfu counts were taken immediately before ParT induction, as well as 15 min and 1 h after induction. Within 15 min, the viability of E. coli expressing only ParT had fallen drastically by four orders of magnitude (Fig. 5 B and C). Cultures that had been expressing H131A Prs before ParT induction showed a single order of magnitude decrease in cell viability, markedly better than ParT-only cells. This result strongly agrees with the growth data and confirms that the increased cell density is due to improved viability caused by the presence of H131A Prs.

Discussion

Here, we provide biochemical and structural insights into the nature of the COG5654–COG5642 TA system, identifying the toxin as a mART that targets the essential metabolic enzyme Prs. We have thus renamed the toxin parT and the cognate antitoxin parS. We determined a high-resolution crystal structure of the ParST complex, which revealed that the complex crystalizes as a dimer (Fig. 3A). Disruption of the dimeric interface between the toxins leads to a loss of the toxic phenotype (SI Appendix, Fig. S9), illustrating that ParT is a mART that functions as an obligate dimer. The C terminus of each ParS antitoxin is buried in the active site cleft of the cognate toxin, forming a salt bridge with both His-56 and Arg-31 of ParT. Among mARTs, this is an example with a high-affinity inhibitor that directly binds the mART active site.

Although a BLAST of ParT reveals sequence similarity only to other RES domain proteins, a DALI search revealed multiple mARTs with similarities in secondary structure, including exotoxins such as diphtheria, cholera, and pertussis toxins (Dataset S3). However, key differences emerge between ParT and these known bacterial mARTs, making it a unique addition to this family of enzymes. First, the exotoxins are all secreted and have eukaryote-specific targets. ParT, however, acts in the cytoplasm of its producing cells and its target, Prs, is conserved among all free-living organisms. The secretion of mART exotoxins is accomplished with an N-terminal signaling sequence, while uptake into eukaryotic cells is mediated in most cases through a distinct recognition domain. This is not the case for ParT, however, which is comprised solely of the catalytic RES domain. In this sense, ParT is most like C3 bacterial mARTs, which are also single-domain proteins, although they retain an N-terminal signal sequence (60). Furthermore, despite the similar domain architecture, C3 toxins (∼25 kDa) are substantially larger than ParT (∼18 kDa) and a structural alignment reveals little similarity. To our knowledge, ParT is the smallest example of a mART and, thus, may represent a mART that appeared early in evolution.

The catalytic motif of ParT bears a resemblance to both diphtheria toxin-like (DT) and cholera toxin-like (CT) mART motifs but is distinct from both. The defining DT HYE motif features two highly conserved tyrosines, a histidine, and glutamate, all critical for toxicity (60). ParT and other RES domain proteins include each of these residues in their active site, with the Glu and His residues important for toxin function (Fig. 2B). ParT also contains one conserved Tyr residue, but it is not critical for toxicity (Fig. 2B). The HYE motif of DT lacks an arginine residue comparable to the critical Arg-31 residue in ParT (Figs. 2B and 3B), highlighting the differences between these two mART active sites. The CT RSE motif is defined by a critical arginine, an STS sequence, and an (E/N)XE sequence (60). Despite being almost identical in name to the RES domain in ParT, there are minimal similarities between these active sites besides the critical arginine residue. Current structural and biochemical data on the mechanism of mART exotoxins suggests that mART active sites stabilize the cation formed upon glycohydrolysis of NAD+ (36, 61, 62). Given that the ParT active site differs from both of the canonical mART active sites, it is an attractive target for further mechanistic analysis of the ADP-ribosyltransferase reaction.

Recently, the DarT toxin was shown to ADP-ribosylate thymidines on single-stranded DNA, establishing nucleotidyl ADP-ribosylation as yet another bacteriostatic mechanism of the diverse type II toxins (19). In contrast, our work demonstrates that type II toxins can also be protein mARTs. Intracellular protein mARTs in bacteria are exceptionally rare, with the only prior example a nitrogenase mART from Rhodospirillum rubrum (63). ParT exerts its bacteriostatic effect via modification of a cellular target, Prs. This represents an essential cellular function, nucleotide biosynthesis, targeted by TA systems. Further distinguishing the ParST system from DarTG is that ParS exhibits toxin neutralization via a protein–protein interaction, rather than the modification-reversing activity of ADP-ribosyl glycohydrolase DarG. While the structure of DarG was determined, there is no structure of DarT to compare with the ParT structure. Furthermore, DarT and ParT share little sequence similarity and DarT is 230 aa compared with the much smaller ParT (161 aa). A recent review article postulated that additional TA systems could harbor mARTs that modify proteins (64). Our work here bears out that prediction and shows that this type of TA system is exceptionally widespread across bacteria.

Methods

Plasmid Construction.

All cloning was performed in E. coli XL1 Blue cells. Genes encoding toxin and antitoxin were amplified from the genome of Sphingobium sp. YBL2. The organism was a gift from Xin Yan’s laboratory at Nanjing Agriculture University, Nanjing, China. Antitoxin was cloned into high copy pQE80-L, and toxin was cloned into low copy pBAD33. For coexpression, the proteins were cloned into pRSF-duet. Macro domain AF1521 as well as E. coli and Sphingobium sp. YBL2 Prs were cloned into pQE80-L. Mutations were introduced using PCR site-directed mutagenesis. A full list of primers and plasmids used in this study can be found in SI Appendix, Tables S5 and S6.

COG5654–COG5642 Genome Search.

The code used to search for COG5654–COG5642 TA pairs can be found in Dataset S1 in SI Appendix.

Protein Expression and Purification.

All His-tagged protein expression was induced in midlog phase BL21(DE3) E. coli (ΔslyD) and carried out for 3 h at 37 °C. Proteins were purified via Ni-NTA native affinity purification according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Qiagen). For toxin isolation, TA complex was first purified as described above. The complex was dissociated in 6 M urea, and denatured toxin was repurified by Ni-NTA affinity purification. Arginine was then added to a final concentration of 200 mM, and the sample was dialyzed against TBS supplemented with 200 mM arginine using a Slide-alyzer cassette (GE) followed by buffer exchange into TBS.

Growth Curves.

Growth curves were measured using a Synergy 4 plate reader (Biotek). In isolated toxin expression, expression was induced at the beginning of exponential phase by the addition of arabinose. In coexpressions with other proteins, the nontoxic protein was induced 1 h before the toxin. Expressions were carried out for at least 4 h.

Trypsin Digestion of Native TA Complex.

Trypsin digestion was carried out with sequencing grade modified trypsin according to the manufacturer’s protocol without a denaturation step (Promega). The digested complex was analyzed by SDS/PAGE and LC/MS to determine the extent of degradation (LC: Agilent 1260 Infinity with Zorbax 300SB-C18 column, MS: Agilent 3560 Accurate-Mass qTOF).

SeMet Protein Expression and Purification.

Overnight cultures were used to inoculate M9 minimal media supplemented with 50 mg/L selenomethionine and 40 mg/L of all amino acids except for methionine. Cultures were grown to early log phase, at which point a solution of Ile, Leu, Val, Lys, Phe, and Thr (10 mg/mL each) was added to suppress Met biosynthesis. After 20 min, protein expression was induced. Expression, purification, and trypsin digestion of the complex were all carried out as described above.

Protein Crystallization.

A 10 mg/mL solution of trypsin-digested TA complex was subject to screening using a Phoenix crystallization robot (Art Robbins). On scaleup, crystals were grown at 20 °C using the sitting-drop vapor diffusion method. Drops were 1.5 µL:1 µL protein solution:MPD precipitant solution (0.1 M sodium acetate trihydrate, 10 vol% MPD, pH 5.0). Crystals typically reached maximum size in 2 wk, were harvested, and dipped in cryoprotectant (MPD solution and 10% glycerol) before vitrification. SeMet-substituted L48M TA complex was crystallized using identical methods. Data for SeMet L48M TA complex was collected at the Brookhaven National Laboratory National Synchrotron Light Source II, and phasing was determined using SAD. The SeMet L48M TA structure was used to solve the wild-type TA complex, with data collected in the Princeton macromolecular crystallography core facility with a Rigaku Micromax-007HF X-ray generator and Dectris Pilatus 3R 300K area detector.

Macro Domain Pulldown and Prs Identification.

E. coli expressing toxin for 1 h were harvested and lysed by sonication. Separately, His-tagged macro domain protein was incubated with Ni-NTA slurry to saturate the resin and reduce nonspecific binding. The macro domain-slurry mixture was then incubated with the toxin-induced lysate for 2 h at room temperature before purification. The elutions were analyzed by SDS/PAGE and subject to an in-gel trypsin digest according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Digests were analyzed by LC/MS against the MASCOT protein database.

In Vitro ADP–Ribosylation.

Reactions were performed in TBS at 37 °C. Prs concentration was held constant at 10 µM, while NAD(P)+ concentration was varied between 1 mM and 10 mM and toxin between 1 µM and 5 µM. Samples were taken after 3 h, and the reactions continued overnight (20 h total). For intact protein analysis, samples were injected directly onto the Agilent LC/MS system described above. Trypsin-digested samples were used to determine the modification sites using a coupled Easy 1200 UPLC and Fusion LUMOS mass spectrometer at the Princeton University core facility.

Cell Viability (Cfu Count).

Cells transformed with toxin, toxin and blank pQE80-L, or toxin and H131A Prs were grown to the beginning of log phase, at which point nontoxic proteins were allowed to express for 1 h before toxin expression was then induced. Samples of culture were taken immediately before toxin induction, as well as 15 min and 1 h after induction. These were serial diluted in LB and plated on LB with the appropriate antibiotics. Plates were incubated overnight at 37 °C and colonies were counted manually the next day.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Tharan Srikumar of the Princeton University Mass Spectrometry Facility for assistance with HCD LC/MS2 experiments, the staff of beamline AMX at the National Synchrotron Light Source II for assistance with data collection, and Jordan Ash of Ryan Adams’ laboratory at Princeton University for assistance with writing and implementing code for the ParST genome search. Funding was provided in part by NIH Grant GM107036 (to A.J.L.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: The atomic coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, www.wwpdb.org (PDB ID codes 6D0I and 6D0H).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1814633116/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Ogura T, Hiraga S. Mini-F plasmid genes that couple host cell division to plasmid proliferation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1983;80:4784–4788. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.15.4784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gerdes K, Rasmussen PB, Molin S. Unique type of plasmid maintenance function: Postsegregational killing of plasmid-free cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:3116–3120. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.10.3116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gerdes K, et al. Mechanism of postsegregational killing by the hok gene product of the parB system of plasmid R1 and its homology with the relF gene product of the E. coli relB operon. EMBO J. 1986;5:2023–2029. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1986.tb04459.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Masuda Y, Miyakawa K, Nishimura Y, Ohtsubo E. chpA and chpB, Escherichia coli chromosomal homologs of the pem locus responsible for stable maintenance of plasmid R100. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:6850–6856. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.21.6850-6856.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aizenman E, Engelberg-Kulka H, Glaser G. An Escherichia coli chromosomal “addiction module” regulated by guanosine [corrected] 3′,5′-bispyrophosphate: A model for programmed bacterial cell death. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:6059–6063. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.12.6059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.González Barrios AF, et al. Autoinducer 2 controls biofilm formation in Escherichia coli through a novel motility quorum-sensing regulator (MqsR, B3022) J Bacteriol. 2006;188:305–316. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.1.305-316.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ren D, Bedzyk LA, Thomas SM, Ye RW, Wood TK. Gene expression in Escherichia coli biofilms. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2004;64:515–524. doi: 10.1007/s00253-003-1517-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Korch SB, Henderson TA, Hill TM. Characterization of the hipA7 allele of Escherichia coli and evidence that high persistence is governed by (p)ppGpp synthesis. Mol Microbiol. 2003;50:1199–1213. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03779.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang X, Wood TK. Toxin-antitoxin systems influence biofilm and persister cell formation and the general stress response. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2011;77:5577–5583. doi: 10.1128/AEM.05068-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Page R, Peti W. Toxin-antitoxin systems in bacterial growth arrest and persistence. Nat Chem Biol. 2016;12:208–214. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thisted T, Sørensen NS, Wagner EG, Gerdes K. Mechanism of post-segregational killing: Sok antisense RNA interacts with Hok mRNA via its 5′-end single-stranded leader and competes with the 3′-end of Hok mRNA for binding to the mok translational initiation region. EMBO J. 1994;13:1960–1968. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06465.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bahassi EM, et al. Interactions of CcdB with DNA gyrase. Inactivation of Gyra, poisoning of the gyrase-DNA complex, and the antidote action of CcdA. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:10936–10944. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.16.10936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hurley JM, Woychik NA. Bacterial toxin HigB associates with ribosomes and mediates translation-dependent mRNA cleavage at A-rich sites. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:18605–18613. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.008763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang Y, et al. MazF cleaves cellular mRNAs specifically at ACA to block protein synthesis in Escherichia coli. Mol Cell. 2003;12:913–923. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00402-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pedersen K, et al. The bacterial toxin RelE displays codon-specific cleavage of mRNAs in the ribosomal A site. Cell. 2003;112:131–140. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01248-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Germain E, Castro-Roa D, Zenkin N, Gerdes K. Molecular mechanism of bacterial persistence by HipA. Mol Cell. 2013;52:248–254. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.08.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bernard P, Couturier M. Cell killing by the F plasmid CcdB protein involves poisoning of DNA-topoisomerase II complexes. J Mol Biol. 1992;226:735–745. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90629-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harms A, et al. Adenylylation of gyrase and topo IV by FicT toxins disrupts bacterial DNA topology. Cell Rep. 2015;12:1497–1507. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.07.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jankevicius G, Ariza A, Ahel M, Ahel I. The toxin-antitoxin system DarTG catalyzes reversible ADP-ribosylation of DNA. Mol Cell. 2016;64:1109–1116. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Makarova KS, Wolf YI, Koonin EV. Comprehensive comparative-genomic analysis of type 2 toxin-antitoxin systems and related mobile stress response systems in prokaryotes. Biol Direct. 2009;4:19. doi: 10.1186/1745-6150-4-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ramage HR, Connolly LE, Cox JS. Comprehensive functional analysis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis toxin-antitoxin systems: Implications for pathogenesis, stress responses, and evolution. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000767. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Milunovic B, diCenzo GC, Morton RA, Finan TM. Cell growth inhibition upon deletion of four toxin-antitoxin loci from the megaplasmids of Sinorhizobium meliloti. J Bacteriol. 2014;196:811–824. doi: 10.1128/JB.01104-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shao Y, et al. TADB: A web-based resource for type 2 toxin-antitoxin loci in bacteria and archaea. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:D606–D611. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maksimov MO, Pelczer I, Link AJ. Precursor-centric genome-mining approach for lasso peptide discovery. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:15223–15228. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1208978109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yamaguchi Y, Park J-H, Inouye M. Toxin-antitoxin systems in bacteria and archaea. Annu Rev Genet. 2011;45:61–79. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-110410-132412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guzman LM, Belin D, Carson MJ, Beckwith J. Tight regulation, modulation, and high-level expression by vectors containing the arabinose PBAD promoter. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:4121–4130. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.14.4121-4130.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gotfredsen M, Gerdes K. The Escherichia coli relBE genes belong to a new toxin-antitoxin gene family. Mol Microbiol. 1998;29:1065–1076. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00993.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rosano GL, Ceccarelli EA. Recombinant protein expression in Escherichia coli: Advances and challenges. Front Microbiol. 2014;5:172. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Prysak MH, et al. Bacterial toxin YafQ is an endoribonuclease that associates with the ribosome and blocks translation elongation through sequence-specific and frame-dependent mRNA cleavage. Mol Microbiol. 2009;71:1071–1087. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06572.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang J, Zhang Y, Inouye M. Characterization of the interactions within the mazEF addiction module of Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:32300–32306. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304767200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McKenzie JL, et al. Determination of ribonuclease sequence-specificity using pentaprobes and mass spectrometry. RNA. 2012;18:1267–1278. doi: 10.1261/rna.031229.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Krissinel E, Henrick K. Inference of macromolecular assemblies from crystalline state. J Mol Biol. 2007;372:774–797. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Holm L, Kääriäinen S, Rosenström P, Schenkel A. Searching protein structure databases with DaliLite v.3. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:2780–2781. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Van Ness BG, Howard JB, Bodley JW. ADP-ribosylation of elongation factor 2 by diphtheria toxin. Isolation and properties of the novel ribosyl-amino acid and its hydrolysis products. J Biol Chem. 1980;255:10717–10720. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jørgensen R, et al. Cholix toxin, a novel ADP-ribosylating factor from Vibrio cholerae. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:10671–10678. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M710008200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jørgensen R, et al. Exotoxin A-eEF2 complex structure indicates ADP-ribosylation by ribosome mimicry. Nature. 2005;436:979–984. doi: 10.1038/nature03871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tsumoto K, et al. Role of arginine in protein refolding, solubilization, and purification. Biotechnol Prog. 2004;20:1301–1308. doi: 10.1021/bp0498793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tsuge H, et al. Crystal structure and site-directed mutagenesis of enzymatic components from Clostridium perfringens iota-toxin. J Mol Biol. 2003;325:471–483. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)01247-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nagahama M, Sakaguchi Y, Kobayashi K, Ochi S, Sakurai J. Characterization of the enzymatic component of Clostridium perfringens iota-toxin. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:2096–2103. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.8.2096-2103.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kandel J, Collier RJ, Chung DW. Interaction of fragment A from diphtheria toxin with nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide. J Biol Chem. 1974;249:2088–2097. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Picchianti M, et al. Auto ADP-ribosylation of NarE, a Neisseria meningitidis ADP-ribosyltransferase, regulates its catalytic activities. FASEB J. 2013;27:4723–4730. doi: 10.1096/fj.13-229955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Weng B, Thompson WC, Kim H-J, Levine RL, Moss J. Modification of the ADP-ribosyltransferase and NAD glycohydrolase activities of a mammalian transferase (ADP-ribosyltransferase 5) by auto-ADP-ribosylation. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:31797–31803. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.45.31797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Karras GI, et al. The macro domain is an ADP-ribose binding module. EMBO J. 2005;24:1911–1920. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dani N, et al. Combining affinity purification by ADP-ribose-binding macro domains with mass spectrometry to define the mammalian ADP-ribosyl proteome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:4243–4248. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900066106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bolanos-Garcia VM, Davies OR. Structural analysis and classification of native proteins from E. coli commonly co-purified by immobilised metal affinity chromatography. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1760:1304–1313. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2006.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Robichon C, Luo J, Causey TB, Benner JS, Samuelson JC. Engineering Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) derivative strains to minimize E. coli protein contamination after purification by immobilized metal affinity chromatography. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2011;77:4634–4646. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00119-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hove-Jensen B, et al. Phosphoribosyl diphosphate (PRPP): Biosynthesis, enzymology, utilization, and metabolic significance. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2016;81:e00040. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00040-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hove-Jensen B, Harlow KW, King CJ, Switzer RL. Phosphoribosylpyrophosphate synthetase of Escherichia coli. Properties of the purified enzyme and primary structure of the prs gene. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:6765–6771. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bennett BD, et al. Absolute metabolite concentrations and implied enzyme active site occupancy in Escherichia coli. Nat Chem Biol. 2009;5:593–599. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bilan V, Leutert M, Nanni P, Panse C, Hottiger MO. Combining higher-energy collision dissociation and electron-transfer/higher-energy collision dissociation fragmentation in a product-dependent manner confidently assigns proteomewide ADP-ribose acceptor sites. Anal Chem. 2017;89:1523–1530. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.6b03365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hilden I, Hove-Jensen B, Harlow KW. Inactivation of Escherichia coli phosphoribosylpyrophosphate synthetase by the 2′,3′-dialdehyde derivative of ATP. Identification of active site lysines. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:20730–20736. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.35.20730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Roessler BJ, et al. Human X-linked phosphoribosylpyrophosphate synthetase superactivity is associated with distinct point mutations in the PRPS1 gene. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:26476–26481. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hove-Jensen B, Bentsen A-KK, Harlow KW. Catalytic residues Lys197 and Arg199 of Bacillus subtilis phosphoribosyl diphosphate synthase. Alanine-scanning mutagenesis of the flexible catalytic loop. FEBS J. 2005;272:3631–3639. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.04785.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Becker MA, Taylor W, Smith PR, Ahmed M. Overexpression of the normal phosphoribosylpyrophosphate synthetase 1 isoform underlies catalytic superactivity of human phosphoribosylpyrophosphate synthetase. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:19894–19899. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.33.19894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Timofeev VI, et al. Three-dimensional structure of phosphoribosyl pyrophosphate synthetase from E. coli at 2.71 Å resolution. Crystallogr Rep. 2016;61:44–54. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Harlow KW, Switzer RL. Chemical modification of Salmonella typhimurium phosphoribosylpyrophosphate synthetase with 5′-(p-fluorosulfonylbenzoyl)adenosine. Identification of an active site histidine. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:5487–5493. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ames GF, Niakido K. In vivo methylation of prokaryotic elongation factor Tu. J Biol Chem. 1979;254:9947–9950. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lippmann C, et al. Prokaryotic elongation factor Tu is phosphorylated in vivo. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:601–607. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Arai K, et al. Primary structure of elongation factor Tu from Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1980;77:1326–1330. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.3.1326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Simon NC, Aktories K, Barbieri JT. Novel bacterial ADP-ribosylating toxins: Structure and function. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2014;12:599–611. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tsurumura T, et al. Arginine ADP-ribosylation mechanism based on structural snapshots of iota-toxin and actin complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:4267–4272. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1217227110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tsuge H, et al. Structural basis of actin recognition and arginine ADP-ribosylation by Clostridium perfringens ι-toxin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:7399–7404. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801215105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pope MR, Murrell SA, Ludden PW. Covalent modification of the iron protein of nitrogenase from Rhodospirillum rubrum by adenosine diphosphoribosylation of a specific arginine residue. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:3173–3177. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.10.3173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lüscher B, et al. ADP-ribosylation, a multifaceted posttranslational modification involved in the control of cell physiology in health and disease. Chem Rev. 2018;118:1092–1136. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.