Significance

Individual differences in HIV-1 control and progression to AIDS have been pinpointed to genetic variation in the HLA, coding for antigen-presenting molecules. However, our understanding of the corresponding antigens is still incomplete. Here we developed an approach that combines HLA genotypes and viral load data of HIV-infected individuals to screen the entire HIV-1 proteome for disease-relevant peptides. Our PepWAS approach identified a limited manageable core set of peptides, accounting for the entire variation in viral load previously associated with genetic variation in the HLA. This core set of disease-relevant antigens thus provides a functional link between HLA genetic variation and HIV-1 control, confirming several known antigens, but also prioritizing previously undescribed antigens as potential therapeutic targets.

Keywords: HLA, MHC, HIV-1, epitope prediction, antigen presentation

Abstract

Genetic variation in the peptide-binding groove of the highly polymorphic HLA class I molecules has repeatedly been associated with HIV-1 control and progression to AIDS, accounting for up to 12% of the variation in HIV-1 set point viral load (spVL). This suggests a key role in disease control for HLA presentation of HIV-1 epitopes to cytotoxic T cells. However, a comprehensive understanding of the relevant HLA-bound HIV epitopes is still elusive. Here we describe a peptidome-wide association study (PepWAS) approach that integrates HLA genotypes and spVL data from 6,311 HIV-infected patients to interrogate the entire HIV-1 proteome (3,252 unique peptides) for disease-relevant peptides. This PepWAS approach predicts a core set of epitopes associated with spVL, including known epitopes but also several previously uncharacterized disease-relevant peptides. More important, each patient presents only a small subset of these predicted core epitopes through their individual HLA-A and HLA-B variants. Eventually, the individual differences in these patient-specific epitope repertoires account for the variation in spVL that was previously associated with HLA genetic variation. PepWAS thus enables a comprehensive functional interpretation of the robust but little-understood association between HLA and HIV-1 control, prioritizing a short list of disease-associated epitopes for the development of targeted therapy.

HLA class I proteins are thought to play a critical role in immune recognition of HIV-1 by presenting endogenously processed viral peptides at the surface of infected cells to cytotoxic T cells to trigger destruction of the infected cells (1). Indeed, genetic variation in the HLA region has repeatedly been identified as the major genetic determinant of HIV-1 control in genome-wide association studies (2, 3). Most recently, McLaren et al. (4) fine-mapped the entire HLA’s association with HIV-1 control and disease progression to five independent amino acid residues in the peptide binding groove of the HLA-B and HLA-A molecules. These five residues alone accounted for 12.3% of the variation in viral load, suggesting a major role for specific HLA-presented viral epitopes in HIV-1 control. However, our understanding of the disease-relevant viral epitopes is still incomplete, hampered by the economically hardly feasible challenge of employing a full-factorial experimental assay to screen the entirety of the HIV-1 peptidome for binding by all relevant HLA alleles. Therefore, we developed a computational analysis approach that identifies and prioritizes disease-associated peptides based on individual HLA genotype and disease phenotype information. Our approach uses established computational algorithms to predict for each individual whether a given peptide is bound by the individual’s HLA variants, and then uses regression analysis on the disease phenotype (here the HIV set point viral load) to estimate whether the ability to bind the peptide is nonrandomly associated with the disease phenotype. This approach is analogous to a genetic association study, except that it incorporates one additional layer by translating genetic variation into functional variation (HLA variant-specific peptide binding). Importantly, this approach does not simply define all peptides bound by a risk HLA variant as risk peptides. Instead, for each peptide, it integrates the disease effect of all HLA variants that are able to bind the peptide, and thus estimates a peptide-specific association with disease. Because most peptides are bound by several HLA variants, integrating the effect of all binding HLA variants is essential (Fig. 1). For instance, a peptide can have no association with disease, even if it is bound by the highest-risk variant, simply because it is also bound by several other nonassociated (or even protective) variants. Ultimately, our approach identifies a list of peptides with varying associations to disease, which can directly inform therapy development by prioritizing global as well as patient-specific candidate epitopes. As a proof of concept, we analyze here a unique dataset of 6,311 individuals of European ancestry with chronic HIV-1 infection (SI Appendix, Table S1). Screening the entire HIV-1 peptidome for candidate epitopes, we identify a comprehensive list of peptides that explain the well-established association between HLA genetic variation and HIV-1 control, including several previously uncharacterized epitopes as candidates for targeted therapy.

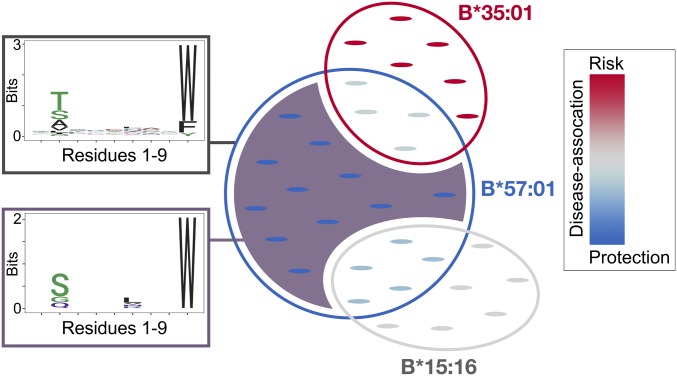

Fig. 1.

Schematic for determining peptide-specific associations through PepWAS. Disease-associated peptides are identified by integrating the different disease associations of the different HLA alleles that are predicted to bind them. Some peptides will only be bound by one HLA allele, thus drawing their disease association directly from the disease association of that allele (e.g., peptides in the purple shaded area, bound only by HLA-B*57:01). However, many peptides will be bound by several HLA alleles, which can have quite distinct, possibly even opposing, disease associations (e.g., peptides in overlap of B*57:01 and B*35:01). In this case, the disease association of the peptide derives from the disease associations of each of the binding HLA alleles, as well as their frequencies in the dataset. The PepWAS approach differentiates these distinct sets of peptides and identifies both specific peptides and epitope motifs with distinct disease association (e.g., distinct motif of purple-shaded peptides, corresponding to the dark purple cluster in Fig. 4). Circles depict repertoires of peptides (small pointed ovals) predicted to be bound by the given HLA allele. Overlap of circles defines sets of peptides bound by both HLA alleles. Color of circles and peptides depicts disease association of corresponding HLA alleles and peptides, respectively, from blue (protective) to red (risk). The number of peptides in this schematic does not correspond to the actual number of peptides observed for these HLA alleles. In reality, the overlap among HLA alleles is substantially more complex than depicted in this simplified schematic.

Results and Discussion

Our analyses are based on a large dataset of HIV-infected individuals (4) that includes both pretreatment level of set point viral load (spVL) as a correlate of disease progression (5) and imputed HLA genotypes (4-digit allele resolution). We focused on the two HLA loci (HLA-B and HLA-A) reported to have independent associations with HIV-1 control and disease progression (4). Potential HLA-bound peptides were identified using an established computational algorithm that is based on empirical training data (6) and integrates several complementary prediction methods in a consensus approach, outperforming comparable algorithms (6, 7). Such algorithms have been used in a wide spectrum of HLA-related studies ranging from vaccine design to cancer evolution and HIV disease genetics (8–10). Without a priori selection, we screened all possible 9mer HIV-1 peptides (n = 3,252) in a sliding window across the entire HIV-1 M group subtype B reference proteome (11) against all represented HLA-B and HLA-A alleles (344,712 HLA:peptide complexes), and identified 214 and 173 distinct HIV-1 peptides predicted to be bound by one or more of the represented HLA-B and HLA-A alleles, respectively.

To evaluate the significance of the predicted peptide repertoires, we interrogated several layers of empirical evidence (SI Appendix, Supporting Text). We observed an enrichment for previously known HIV-1 epitopes (SI Appendix, Fig. S1A) and a correlation between an HLA-B allele’s effect on viral load and the number of HIV-1 peptides it is predicted to bind (SI Appendix, Fig. S1B), and detected previously reported viral escape mutations (SI Appendix, Fig. S1C). After these independent layers of evidence that our analysis pipeline predicts disease-relevant binding of HLA to HIV-1 peptides, we subsequently refer to the entire predicted set of HLA-bound peptides as predicted epitopes, highlighting the point that not all of them have been experimentally validated.

Next, we tested whether the patient-specific repertoire of predicted HIV-1 epitopes, defined by the number of peptides predicted to be bound by the specific HLA allele combination of the patient, was associated with spVL. For this, we ran a linear regression across the 6,311 HIV-1 patients, with spVL as dependent variable and the patient-specific number of bound peptides as predicting variable, together with other covariates (see Methods). We first focused on the effect of peptides bound by HLA-B, and used only the known CTL epitopes from the Los Alamos HIV Molecular Immunology Database (12), of which 80 were represented among the 214 predicted HLA-B bound epitopes. The individual number of these known CTL epitopes bound by patient-specific HLA-B variants accounted for only 1.8% of the individual variation in spVL (Fig. 2). To evaluate this association, we then included all predicted HLA-bound HIV-1 epitopes (n = 214) in the analysis, including the previously known CTL epitopes, as well as any other HLA-B-bound peptide from the HIV-1 proteome. Interestingly, the total number of all predicted HLA-B-bound epitopes per patient accounted for 5.3% variation in spVL (Fig. 2), suggesting that the Los Alamos CTL epitope dataset is not yet fully saturated with regard to disease-relevant peptides. However, the accounted variation was still lower than the 11.4% variation associated with genetic variation at HLA-B in previous genotype-based studies, suggesting that the total predicted epitope repertoire still included peptides irrelevant for the association between HLA and HIV-1. This is supported by a previous study, which showed that not all HLA-bound peptides are epitopes targeted by CD8+ T cells (13). We thus aimed to refine the repertoire of predicted HLA-bound HIV-1 epitopes further to comprise only disease-relevant epitopes. For this, we calculated the epitope-specific association with spVL by running a separate linear regression for each predicted epitope and recording R2 and β-coefficient as measures of the epitope’s effect on spVL. This is analogous to the approach of a genome-wide association study (GWAS), in which each genetic variant is tested for its association with a given trait, except that here we focus on functional protein variation (peptide binding by a patient’s HLA molecules) rather than genetic variation. Following this analogy, we term our approach peptidome-wide association study (PepWAS). Of 214 HIV-1 epitopes predicted to be bound by HLA-B, 132 accounted for nominal variation (adjusted R2 value > 0) in spVL, 74 of which were negatively and 58 positively associated with spVL (β-coefficients ranging from −0.1 to 0.77; SI Appendix, Table S2). Importantly, we do not require statistical significance at this point, as this is a candidate screen and we thus aim to minimize the number of false negatives. Subsequently, we designate the nominally associated epitopes as disease-associated predicted epitopes, even though their effects are not necessarily independent, as they were tested with separate regression models. An analogous investigation of peptide binding by HLA-A alleles revealed an additional 74 disease-associated epitopes (SI Appendix, Table S3).

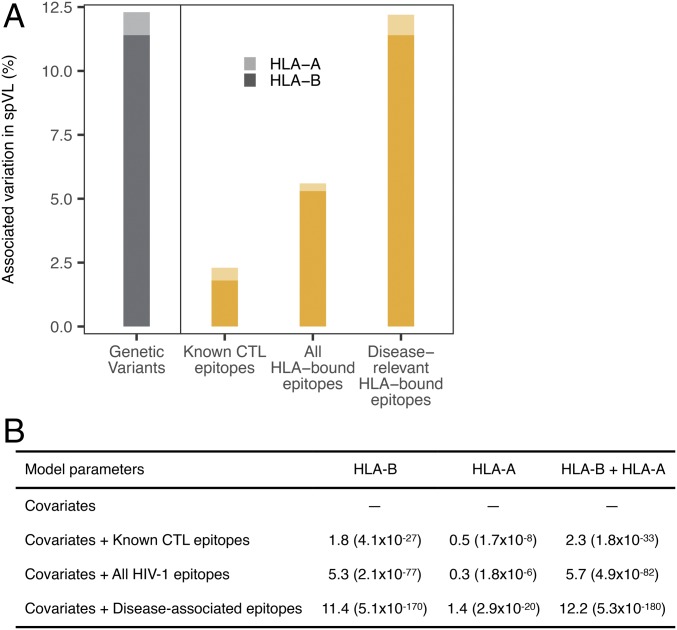

Fig. 2.

Variation in viral load associated with predicted epitope repertoires bound by HLA-B and HLA-A. Among patients with HIV (n = 6,311), the proportion of variation (estimated as adjusted ΔR2) in spVL associated with the patient-specific number of predicted HLA-bound HIV-1 epitopes is shown separately for HLA-B and HLA-A, and for different epitope sets. (A) Previously, 11.4% and 0.9% of the variation in spVL had been associated with independent genetic variants in HLA-B and HLA-A, respectively (gray bars; data from ref. 4). Here we instead calculated the variation in spVL associated with individual HLA-bound HIV epitope repertoires (yellow bars), based on known CTL epitopes from Los Alamos HIV Molecular Immunology Database, all HLA-bound HIV epitopes, and only the disease-associated HIV epitopes (the latter corresponding to 99.2% of the variation previously associated with HLA genetic variation). (B) Variation (in percent) associated with different sets of predicted epitopes. P values (in parentheses) indicate the improvement over null model (covariates only: first five PCs and the cohort group). The number of disease-associated predicted epitopes is 132 for HLA-B, and 74 for HLA-A.

Having refined the predicted HIV-1 epitope repertoire to only disease-associated predicted epitopes, we then tested whether this subset accounted for a larger fraction of the variation in spVL than the total predicted HIV-1 epitope repertoire. Indeed, the patients’ ability to bind a smaller or larger fraction of the HLA-B-specific disease-associated predicted epitopes accounted for 11.4% of the variation in spVL (Fig. 2). Similarly, for HLA-A, the total number of predicted HIV-1 epitopes bound by individual HLA-A genotypes accounted for 0.3% of the variation, whereas disease-associated predicted epitopes accounted for 1.4% of the variation in spVL. On average, a patient’s HLA-B allele pair bound 16.2 ± 7 (SD) disease-associated predicted HIV-1 epitopes, whereas the HLA-A alleles bound significantly fewer (6.6 ± 6.5; Paired Wilcox rank sum test, P < 0.0001; SI Appendix, Fig. S6). This quantitative difference in peptide presentation might contribute to the stronger spVL-association of HLA-B compared with HLA-A, as a larger number of presented peptides should more likely lead to a more efficient CD8 T-cell response, as has indeed been observed for HLA-B compared with HLA-A (14). HLA-C-bound epitopes did not show any significant association with spVL, mirroring the lack of independent genetic associations for HLA-C in the latest GWAS (4). Predicted disease-associated epitopes of HLA-B and HLA-A together accounted for 12.2% of the variation in HIV-1 viral load, approximately corresponding to the 12.3% variation previously attributed to all independent genetic associations in the entire HLA (Fig. 2A).

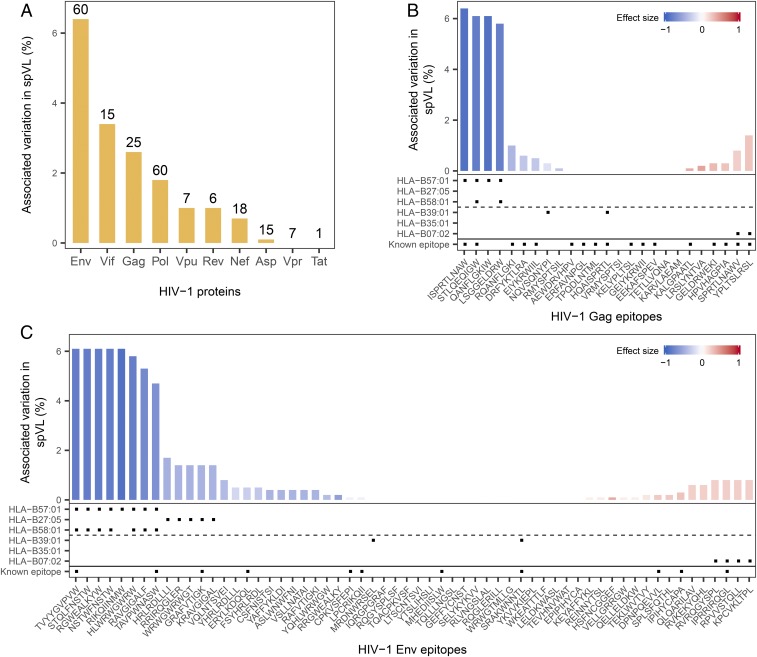

Interestingly, the Env protein showed the largest number of disease-associated predicted epitopes, with both positive and negative effects. Among the HLA-B–specific disease-associated predicted epitopes, Env-derived epitopes alone accounted for 6.4% of variation in spVL, the highest among all HIV-1 proteins (Fig. 3A). In addition to already-known Env-derived CD8+ T-cell targeted epitopes associated with lower viral load and disease control [e.g., RIKQIINMW, HRLRDLLLI (13), ERYLKDQQL (15)], our analysis revealed previously undescribed HLA–epitope complexes (e.g., B*57:01-STQLFNSTW, B*57:01-NSTWFNSTW, or B*57:01-RGWEALKYW) showing strong associations with lower viral load (Fig. 3C). The potential importance of the predicted Env epitopes is quite surprising, as the high genetic variability of the Env protein across different HIV-1 isolates suggests that the virus could readily evolve escape variants in this protein. However, a previous study has already established that sequence conservation alone is not a reliable predictor of protective epitopes, instead highlighting structural conservation as the more important feature (13). More intriguingly, we found that the protective Env epitopes predicted through our PepWAS approach are significantly enriched for residues that are associated with broadly neutralizing antibodies (odds ratio = 1.5, P = 0.036, SI Appendix, Fig. S7), suggesting that they represent parts of the Env protein that can be efficiently targeted in antibody therapy, as well as in HLA-mediated CTL response.

Fig. 3.

Protein- and epitope-specific association with viral load. (A) Percentage of variation in spVL associated with all predicted epitopes of a given HIV-1 protein. Absolute number of predicted HLA-B-bound epitopes per protein is shown above the bars. (B and C) Predicted HLA-B-bound epitopes accounted for varied levels of variation in spVL. Height of the bar represents the fraction of variation in spVL associated with each epitope, whereas the color reflects each epitope’s effect on spVL, ranging from protection (blue) to risk (red). Note that epitope effects are estimated separately, and are thus not independent. Gag (B) and Env (C) proteins are shown as representative examples, together with information on predicted binding for three protective and three risk HLA-B alleles highlighted in a recent review (24) and whether peptides are known epitopes in Los Alamos HIV database. All other HIV-1 proteins are shown in SI Appendix, Fig. S8.

Notably, several of the represented HLA alleles were predicted to bind both negatively and positively disease-associated epitopes (SI Appendix, Tables S4 and S5), that is, epitopes bound by the same HLA allele did not necessarily have the same effect on viral load. This can be explained by the fact that a given epitope can be bound by several different HLA alleles with very distinct disease association (see schematic in Fig. 1). This is also in agreement with a previous study showing that viral control is mediated by specific immunogenic epitopes that could be restricted by HLA alleles other than already known ones (13).

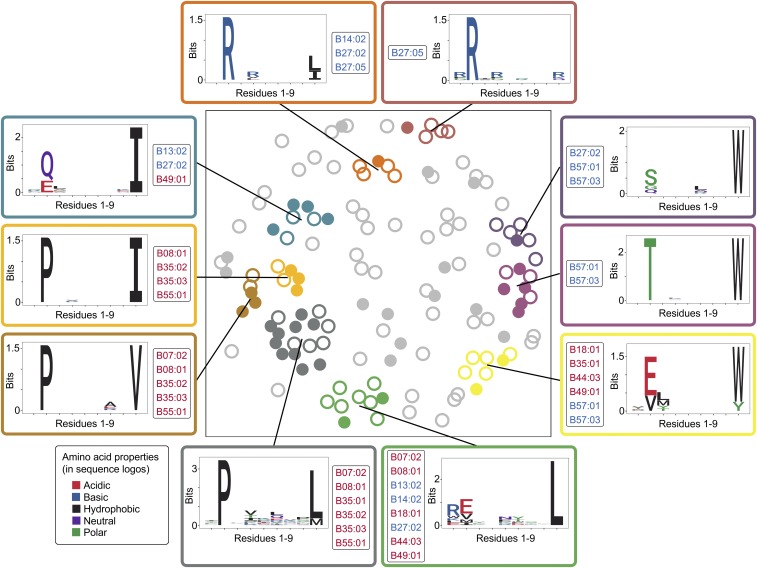

HLA molecule variants are known to bind peptide repertoires with distinct anchor motifs, based on the composition of their peptide-binding groove (16). This entailed the possibility that our PepWAS approach is merely identifying distinct groups of peptides per HLA variant, thus translating the known HLA variant-specific effect on viral load into peptide group-specific effects. Although still helpful in guiding epitope research, this would provide only limited knowledge gain compared with the HLA allele-specific associations known from previous work (4). To test for this possibility, we performed a cluster analysis on the predicted disease-associated epitopes bound by HLA-B (n = 132) and analyzed cluster-specific motifs and HLA allele binding patterns. Intriguingly, among the 10 most dominant epitope clusters, each exhibiting a distinct peptide motif, nine were defined by multiple HLA-B alleles (Fig. 4), some of them even belonging to different supertypes (SI Appendix, Table S7). All these clusters included both previously described and undescribed epitopes, and three of them were defined by both risk- and protection-conferring alleles. Furthermore, all HLA variants bound peptides of multiple dominant clusters (e.g., B*57:01 is associated with three dominant clusters, each showing a distinct peptide motif, but all showing a strong preference for amino acid “W” at anchor position 9; Fig. 4). Overall, the cluster analysis shows that our PepWAS approach identifies groups of peptides with distinct motifs that are different from HLA variant-specific binding motifs (see also schematic in Fig. 1). In general, the 24 disease-associated epitopes predicted to be bound by HLA-B*57:01 (but some of these also by other alleles) accounted for the highest level of variation in spVL, even though they derived from five different HIV-1 proteins (Fig. 3 B and C and SI Appendix, Fig. S8). One of these epitopes, the well-characterized HIV-1 Gag epitope ISPRTLNAW (belonging to the dark purple cluster in Fig. 4), slightly exceeded the effect of all other epitopes (Fig. 3B), in concordance with experimental evidence (17). Other HLA-B alleles, including the B*08, B*44, and B*51 types, were also included in our dataset, and their predicted epitope repertoires roughly followed their disease association known from previous studies (SI Appendix, Fig. S1B; allele-specific associations and number of bound peptides are given in SI Appendix, Table S4).

Fig. 4.

Clusters of disease-associated epitopes. Nonmetric multidimensional scaling was used to visualize the pairwise distance between predicted HLA-B-bound disease-associated epitopes, which revealed 10 dominant clusters. Each circle represents an HLA-B-bound disease-associated epitope (n = 132). Filled circles represent known CTL epitopes from the Los Alamos HIV Molecular Immunology Database (n = 45), whereas open circles represent previously uncharacterized disease-associated predicted epitopes. Cluster-specific motif and HIV-1 associated HLA-B alleles (n = 16) binding the cluster’s epitopes are shown. The coloring of the allele names indicates disease association of the specific alleles.

Mechanistically, a negative association between predicted HIV-1 epitopes and viral load is intuitive and likely results from the peptides’ immunodominant role in CTL response and their escape mutations, leading to significant fitness costs for the virus. However, a number of the predicted HIV-1 epitopes exhibited a positive association with viral load, indicating that they confer lower disease protection relative to the bulk of the peptides. They likely represent peptide variants that fail to elicit an efficient CTL response or can readily mutate with negligible fitness effects, thus allowing viral escape from HLA presentation at no cost for the virus. Indeed, the most risk-associated predicted Vpu epitope, IPIVAIVAL (SI Appendix, Fig. S8F; belonging to the largest, gray cluster in Fig. 4), includes an anchor residue that exhibits significant variation in primary HIV-1 clones and is involved in mediating immune-evasion through down-regulation of HLA-C (18), whose high expression has been implicated in HIV control (19). The lack of significant associations between predicted HLA-C bound epitopes and viral load in our analysis might indicate that previously observed viral control associated with HLA-C is not mediated through specific peptide presentation of HLA-C. However, more research is required to fully understand the role of HLA-C in viral control (18).

So far, our analysis was based on the HIV-1 genome reference sequence. Although widely used for research, focusing on this sequence accession may restrict our findings. We thus repeated the entire analysis using the HIV-1 proteome consensus sequence from the Los Alamos database, which incorporates major variation across different HIV-1 strains. The results remained qualitatively the same (SI Appendix, Fig. S9 and Table S8). However, HIV is well known to exhibit substantial within-host evolution (20, 21), and it is easily conceivable that the ability of a patient’s HLA variants to bind HIV epitopes is significantly affected by genetic variation in the patient’s HIV population (22). We therefore also analyzed patient-specific autologous HIV-1 sequence information, which was available for a small subset of patients, covering eight of the 10 HIV-1 proteins (SI Appendix, Table S6). For four of the eight proteins (Gag, Pol, Vif, and Nef), we found that the proportion of variation in spVL associated with HLA-bound epitope repertoires changed when predicting epitopes from autologous sequences instead of from the reference sequence. In all four cases, the variation associated with predicted autologous epitopes was higher than when using their homologs from the reference sequence (SI Appendix, Table S6), suggesting that our PepWAS approach might be able to explain more variation in spVL than a standard GWAS if autologous sequences were available for a larger fraction of infected individuals.

PepWAS relies on computational algorithms for the prediction of binding affinities between HLA variants and peptides, and is thus inherently limited by their accuracy and specificity. For instance, the empirical data used to train currently established HLA class I algorithms contains mainly 9mer peptides, even though HLA class I molecules can occasionally bind slightly shorter or longer peptides. Such peptides might therefore be missed by current prediction algorithms. However, the current setup does, in fact, identify 9mer cores of larger known epitopes. For instance, the protective 9mer Gag epitope STLQEQIGW predicted here resides within the previously described 10mer Gag epitope TW10 (Fig. 3B). Furthermore, this limitation is likely to be alleviated as more training data are becoming available.

Overall, our findings reveal a functional basis of the robustly established association between HLA genes and HIV-1 infection outcome. We show that both quantity and quality of HLA-bound HIV epitopes contribute to controlling a patient’s viral load. Our data also suggest a more important role for Env protein-derived epitopes than previously thought. Ultimately, our PepWAS approach of combining computational HLA-specific epitope prediction with disease phenotype validation provides a promising avenue for identification and prioritization of disease-relevant epitopes. As such, it complements existing empirical essays for the development of targeted therapy. It is noteworthy that by involving a functional layer (peptide binding), the PepWAS approach enables the detection of disease-relevant properties that are shared among several genetic variants (overlap in peptide binding among HLA alleles). Such shared properties would be undetectable by GWAS because of its focus on distinct genetic variants instead of function, and should therefore lead to higher sensitivity in the PepWAS approach compared with GWAS. Furthermore, the PepWAS approach allows us to account for individual variation in the pathogen proteome if autologous sequence information is available, potentially further increasing sensitivity. As such, it may be applied to any HLA-associated complex disease.

Materials and Methods

For detailed information on materials and methods used, see SI Appendix, Supporting Methods.

Samples and Genotype Data.

We analyzed HLA genotype data and spVL measurements of 6,311 subjects chronically infected with HIV-1. The original data and thorough quality check are described in detail in McLaren et al. (4) and explained briefly in SI Appendix, Supporting Methods.

HLA Binding Affinity for HIV-1 Epitopes.

We used the National Center for Biotechnology Information accession NC_001802.1 as the reference sequence for the HIV-1 proteome (M group subtype B). The algorithm NetMHCcons-1.1 was used to predict HLA allele-specific binding affinities for all 9mer peptides generated from the entire HIV-1 proteome, applying the default affinity rank threshold for strongly bound peptides (rank < 0.5).

Association with Viral Load.

The association of an allele or a peptide with viral load (spVL) was calculated using a linear regression model corrected for population covariates following McLaren et al. (4). Covariates included the first five principle components of SNP variation and the cohort identity [all adopted from McLaren et al. (4)]. Variation in viral load attributable to a given variable (allele or epitope) was calculated as the difference between adjusted-R2 values of the model with variable and covariates and the model with covariates only, following McLaren et al. (4). The variable’s regression coefficient was used as the measure of its effect on viral load.

Clustering of HLA-B-Specific Predicted Epitopes.

Position-associated entropy was calculated for all HLA-B-bound disease-associated epitopes (n = 132) and used for visualization in a nonmetric multidimensional scaling plot, as well as for density-based clustering.

HLA Binding of Peptides from Autologous HIV-1 Sequences.

We analyzed autologous HIV-1 sequences from Bartha et al. (23). Autologous sequences were available for eight of 10 HIV-1 proteins (only Gp41 segment for Env), and only for a small subset of patients in our cohorts (SI Appendix, Table S6).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Patient and HIV sequence data were collected and generously provided by the International Collaboration for the Genomics of HIV. This project was supported by the Emmy Noether Programme of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) (Grant LE 2593/3-1 to T.L.L.). Furthermore, this project has been funded in whole or in part with federal funds from the Frederick National Laboratory for Cancer Research, under Contract HHSN261200800001E. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the US Government. This research was also supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, Frederick National Lab, Center for Cancer Research.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission. D.D.H. is a guest editor invited by the Editorial Board.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1812548116/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Goulder PJR, Walker BD. HIV and HLA class I: An evolving relationship. Immunity. 2012;37:426–440. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fellay J, et al. A whole-genome association study of major determinants for host control of HIV-1. Science. 2007;317:944–947. doi: 10.1126/science.1143767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pereyra F, et al. The major genetic determinants of HIV-1 control affect HLA class I peptide presentation. Science. 2010;330:1551–1557. doi: 10.1126/science.1195271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McLaren PJ, et al. Polymorphisms of large effect explain the majority of the host genetic contribution to variation of HIV-1 virus load. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:14658–14663. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1514867112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mellors JW, et al. Prognosis in HIV-1 infection predicted by the quantity of virus in plasma. Science. 1996;272:1167–1170, and erratum (1997) 275:14. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5265.1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Karosiene E, Lundegaard C, Lund O, Nielsen M. NetMHCcons: A consensus method for the major histocompatibility complex class I predictions. Immunogenetics. 2012;64:177–186. doi: 10.1007/s00251-011-0579-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang H, Lundegaard C, Nielsen M. Pan-specific MHC class I predictors: A benchmark of HLA class I pan-specific prediction methods. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:83–89. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rooney MS, Shukla SA, Wu CJ, Getz G, Hacohen N. Molecular and genetic properties of tumors associated with local immune cytolytic activity. Cell. 2015;160:48–61. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.12.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Strønen E, et al. Targeting of cancer neoantigens with donor-derived T cell receptor repertoires. Science. 2016;352:1337–1341. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf2288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Košmrlj A, et al. Effects of thymic selection of the T-cell repertoire on HLA class I-associated control of HIV infection. Nature. 2010;465:350–354. doi: 10.1038/nature08997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martoglio B, Graf R, Dobberstein B. Signal peptide fragments of preprolactin and HIV-1 p-gp160 interact with calmodulin. EMBO J. 1997;16:6636–6645. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.22.6636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yusim K, et al. HIV Molecular Immunology. Los Alamos National Laboratory Theoretical Biology and Biophysics; Los Alamos, NM: 2009. pp. 3–24. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pereyra F, et al. HIV control is mediated in part by CD8+ T-cell targeting of specific epitopes. J Virol. 2014;88:12937–12948. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01004-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kiepiela P, et al. Dominant influence of HLA-B in mediating the potential co-evolution of HIV and HLA. Nature. 2004;432:769–775. doi: 10.1038/nature03113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Borrow P, Lewicki H, Hahn BH, Shaw GM, Oldstone MBA. Virus-specific CD8+ cytotoxic T-lymphocyte activity associated with control of viremia in primary human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. J Virol. 1994;68:6103–6110. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.9.6103-6110.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Falk K, Rötzschke O, Stevanović S, Jung G, Rammensee HG. Allele-specific motifs revealed by sequencing of self-peptides eluted from MHC molecules. Nature. 1991;351:290–296. doi: 10.1038/351290a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Llano A, Williams A, Olvera A, Silva-Arrieta S, Brander C. Best-characterized HIV-1 CTL epitopes: The 2013 update. HIV Mol Immunol. 2013;2013:3–25. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Apps R, et al. HIV-1 Vpu mediates HLA-C downregulation. Cell Host Microbe. 2016;19:686–695. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2016.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thomas R, et al. HLA-C cell surface expression and control of HIV/AIDS correlate with a variant upstream of HLA-C. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1290–1294. doi: 10.1038/ng.486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cotton LA, et al. Genotypic and functional impact of HIV-1 adaptation to its host population during the North American epidemic. PLoS Genet. 2014;10:e1004295. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li G, et al. An integrated map of HIV genome-wide variation from a population perspective. Retrovirology. 2015;12:18. doi: 10.1186/s12977-015-0148-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kawashima Y, et al. Adaptation of HIV-1 to human leukocyte antigen class I. Nature. 2009;458:641–645. doi: 10.1038/nature07746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bartha I, et al. A genome-to-genome analysis of associations between human genetic variation, HIV-1 sequence diversity, and viral control. eLife. 2013;2:e01123. doi: 10.7554/eLife.01123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McLaren PJ, Carrington M. The impact of host genetic variation on infection with HIV-1. Nat Immunol. 2015;16:577–583. doi: 10.1038/ni.3147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.