Abstract

Background

Despite a large body of studies have demonstrated the multifaceted behavior of high-density lipoproteins (HDLs) in several physiological and pathological processes, the levels of plasma HDL-cholesterol (HDL-C) that may be associated with endobronchial biopsy (EBB)-related bleeding have never been examined.

Methods

We conducted a single-center retrospective cohort study of 628 consecutive patients with primary lung cancer who had undergone EBB at a large tertiary hospital between January 2014 and February 2018. Patients were divided into the bleeding group and the non-bleeding group according to the bronchoscopy report. The association between HDL-C levels and EBB-induced bleeding was evaluated using the LASSO regression analysis, multiple regression analysis and smooth curve fitting adjusted for potential confounders.

Results

There was an inverse association of plasma HDL-C concentration with the incidence of EBB-induced bleeding as assessed by univariate analysis (P < 0.05). However, in piecewise linear regression analysis, a non-linear relationship with threshold saturation effects was observed between plasma HDL-C concentrations and EBB-induced bleeding. The incidence of EBB-induced bleeding decreased with HDL-C concentrations from 1.5 mmol/L up to 2.0 mmol/L (adjusted OR, 0.39; 95% CI, 0.20–0.74), but increased with HDL-C levels above the inflection point (HDL-C = 2.0 mmol/L).

Conclusions

There was a non-linear association between plasma HDL-C concentrations and the risk of EBB-induced bleeding in patients with lung cancer. The plasma level of HDL-C above 2.0 mmol/L or below 1.5 mmol/L may increase the risk of EBB-induced bleeding.

Keywords: High-density lipoprotein, Lung cancer, Endobronchial biopsy, Bleeding

Background

Bronchoscopy is often required in patients with lung cancer, especially in their histopathological diagnosis [1]. However, worthy of note, biopsy-induced bleeding is frequently encountered during bronchoscopy, and massive bleeding in the airway could be life-threatening [2, 3]. Endobronchial biopsy (EBB), one of the most widely used transbronchial biopsy modalities, has been used in the diagnosis of pulmonary disease for more than 40 years [4]. Reportedly, the incidence of EBB-induced bleeding is relatively high, even over 30.0% in patients with lung cancer [5].

With regard to risk factors for bleeding during bronchoscopy, mechanical ventilation, immunosuppressive state, thrombocytopenia or anti-platelet therapy, anti-coagulant drugs use, liver and kidney disorders, heart function failure, and severe pulmonary arterial hypertension were proposed by several studies [6–8]. Nevertheless, whether these factors are in reality associated with bleeding during EBB, remain controversial [9, 10]. On the other hand, most individuals who are subjected to EBB do not have the aforementioned factors in clinical practice.

High-density lipoproteins (HDLs), traditionally known for its multiple protective effects on cardiovascular diseases, such as anti-atherosclerotic, anti-oxidative, anti-inflammatory and immune-modulating [11, 12], has been found to be associated with some hemorrhagic diseases in recent years [13–15]. Since factors affecting the risk of EBB-induced bleeding remain unclear, we hypothesized that plasma HDL-C may be associated with EBB-induced bleeding and had the potential to be a biomarker for EBB-induced bleeding. Therefore, we conducted this study to explore the association of plasma HDL-C with EBB-induced bleeding risk in patients with lung cancer.

Methods

Study population

This retrospective cohort study was based on 628 consecutive lung cancer patients who underwent EBB between January 2014 and February 2018 at the Jinhua Hospital of Zhejiang University, Jinhua, China. All included patients met the following criteria: a. age ≧18 years; b. local exophytic lesions located in tracheobronchial; and c. pathological diagnosis of primary lung cancer. Patients with any of the following factor were excluded, including active bleeding, platelets count < 50 × 103/μl or continuous anti-platelet therapy, continuous anti-coagulant drug use, severe liver or kidney disorders, heart function failure, mechanical ventilation, and immunosuppressive state.

Patients were divided into two groups based on the biopsy results. Specifically, patients received hemostasis maneuvers during EBB were classified to the bleeding group (n = 232); whereas those who did not need hemostasis maneuvers or did not experience hemorrhage during EBB were classified to the non-bleeding group (n = 396). Hemostasis maneuvers during EBB included endobronchial perfusion using 4 °C physiological saline or/and diluted adrenalin (1:10000), and argon plasma coagulation application.

The following characteristics of the study participants were collected: age, sex, smoking (yes or no), lesions location (the trachea, left main bronchi, right main bronchi, and right middle bronchus were classified as central airways; whereas the left lobar bronchi and the right lobar bronchi were classified as peripheral bronchi), histological types of lung cancer (adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, small-cell lung carcinoma, and the other types), TNM stage (stage I and II was considered as early stage; stage III and IV was considered as advanced stage), and comorbidities, including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), coronary heart disease (CHD), hypertension, and diabetes mellitus. The following blood tests (performed on admission, prior to EBB) were collected: high density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), low density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), total cholesterol (TC), triglyceride, apolipoprotein E, apolipoprotein B, white blood cell counts, C-reactive protein (CRP), neutrophil counts, hemoglobin, platelet counts, prothrombin time (PT), activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), and aspartate aminotransferase (AST).

This study was approved by the ethics committee of Jinhua Hospital of Zhejiang University, Jinhua, China. All patients’ information was anonymous preceding the analysis, and the requirement for informed consent, therefore, was waived.

Biopsy procedures

All procedures were performed under general anesthesia. Propofol was used for induction (1.0 mg/kg) and maintenance (3.0–6.0 mg/kg/h), and remifentanil (5.0–10.0 μg/kg/h) was used for sedation and analgesia. During bronchoscopy, a laryngeal mask airway (Well Lead Medical Co., Ltd., Guangzhou, China) was used, and patients underwent transorally bronchoscopy. Bronchoscopy (BF-1 T60, Olympus Corp., Tokyo, Japan) procedures were performed on all patients by two experienced bronchoscopists. Three to five biopsies were generally performed at the same location of the endobronchial lesion by forceps biopsies [16]; however, in a small number of patients, we performed only one biopsy because lesions bled significantly following the first biopsy attempt.

Statistical analysis

Patients’ baseline characteristics were summarized. Age and blood test values were presented as median (Q1-Q3), and categorical variables were presented as a number and percentage. Unpaired t-tests (normal distribution) or Kruskal-Wallis rank sum test (non-normal distribution), Pearson chi-squared tests or the Fisher’s exact, were tested between two groups for comparison, when appropriate. The least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) regression method was employed to assess the strength of association between plasma HDL-C and EBB-induced bleeding. Multiple regression analysis was used to estimate the independent relationship between HDL-C levels and EBB-induced bleeding risk, with and without adjustment for potential confounders. We also used piecewise linear regression to test the threshold effect of HDL-C on EBB-induced bleeding together with a smoothing function. In this study, the adjusted criteria I included variables producing a change in the regression coefficient greater than 10% after introduction into the basic model or removing from the complete model (smoking, histological types, stage, triglyceride, PT, APTT and CRP); the screening criteria II included variables in criteria I, the regression coefficient of co-variable to dependent variable of P < 0.1 (lesions location and neutrophils), and judged by clinical significance (sex, age, and apolipoprotein E). All analyses were performed using R software (The R Foundation; https://www.r-project.org/). A value of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Of 628 consecutive patients, 232 (36.9, 95% confidence interval [CI], 33.2–40.7%) received hemostasis maneuvers following EBB (4 °C physiological saline or/and diluted adrenalin endobronchial perfusion, or argon plasma coagulation). No patient died of severe blood loss after a biopsy. Patients’ baseline characteristics and blood tests are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics and blood tests of the study participants

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Age (year), median (Q1-Q3) | 65 (59–70) |

| Male, n (%) | 487 (77.5) |

| Smoking, n (%) | 394 (62.7) |

| Biopsy bleeding, n (%) | 232 (36.9) |

| Location of lesion, n (%) | |

| Peripheral bronchi | 548 (87.3) |

| Central airway | 80 (12.7) |

| Stage, n (%) | |

| Early | 343 (54.6) |

| Advanced | 285 (45.4) |

| Histological types, n (%) | |

| Adenocarcinoma | 171 (27.2) |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 313 (49.8) |

| SCLC | 111 (17.7) |

| Others | 33 (5.3) |

| Coexisting diseases, n (%) | |

| COPD | 42 (6.7) |

| Hypertension | 155 (24.7) |

| Diabetes | 32 (5.1) |

| CHD | 20 (3.2) |

| Blood tests, median (Q1-Q3) | |

| Triglyceride (mmol/L) | 1.0 (0.8–1.4) |

| TC (mmol/L) | 4.1 (3.5–4.8) |

| HDL-C (mmol/L) | 1.1 (0.9–1.3) |

| LDL-C (mmol/L) | 2.8 (2.3–3.3) |

| Apo E (mg/dL) | 3.6 (2.8–4.6) |

| Apo B (g/L) | 1.0 (0.8–1.2) |

| Homocysteine (μmol/L) | 13.2 (10.7–16.2) |

| WBC (× 109/L) | 6.8 (5.5–8.6) |

| Neutrophils (×109/L) | 4.6 (3.5–6.4) |

| Hemoglobin (g/L) | 128 (116–139) |

| Platelets (×109/L) | 224 (172–280) |

| CRP (mg/L) | 7.7 (1.4–31.1) |

| PT (S) | 13.0 (12.3–13.6) |

| APTT (S) | 35.1 (31.8–38.5) |

| ALT (IU/L) | 17.0 (12.0–25.0) |

| AST (IU/L) | 23.0 (19.0–28.0) |

SCLC Small-cell lung carcinoma; COPD Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CHD Coronary heart disease; TC Total cholesterol; HDL-C High density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C Low density lipoprotein cholesterol; Apo, apolipoprotein; WBC White blood cell; CRP C-reactive protein; PT Prothrombin time; APTT Activated partial thromboplastin time; ALT Alanine aminotransferase; AST Aspartate aminotransferase

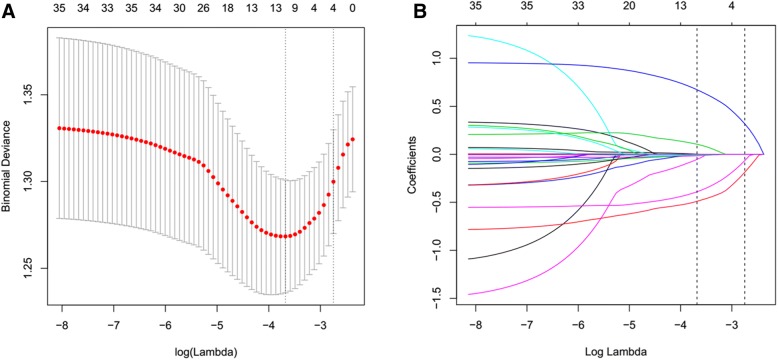

In univariate analysis, the plasma HDL-C concentrations were lower in the bleeding group compared to those in the non-bleeding group (Table 2, P < 0.05). In addition, lesions location, histological types, TNM stage of cancer, smoking, CRP, and APTT were associated with EBB-induced bleeding (Table 2). Based on non-zero coefficients in the LASSO regression analysis (Fig. 1), seven variables were filtered. These variables (coefficient) were HDL-C (− 0.0527), APTT (− 0.0146), neutrophils (0.0024), CRP (0.0015), lesion location (0.6728), TNM stage (− 0.3905) and histological types (− 0.4902), among which the absolute value of coefficient of HDL-C was the maximum in all blood variables, suggesting that HDL-C has a stronger association with EBB-induced bleeding.

Table 2.

Univariate analysis of possible influencing factors of the risk of EBB-induced bleeding

| Variables | EBB-induced Bleeding | |

|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P value | |

| Age (year) | 1.01 (0.99, 1.03) | 0.2029 |

| Sex | ||

| Female | Ref. | |

| Man | 1.33 (0.89, 1.98) | 0.1609 |

| Smoking | ||

| No | Ref. | |

| Yes | 1.45 (1.03, 2.04) | 0.0337 |

| Location of lesion | ||

| Central airway | Ref. | |

| Peripheral bronchi | 0.32 (0.20, 0.51) | < 0.0001 |

| Stage | ||

| Early | Ref. | |

| Advanced | 1.87 (1.35, 2.60) | 0.0002 |

| Histological type | ||

| Adenocarcinoma | Ref. | |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 2.63 (1.73, 4.01) | < 0.0001 |

| SCLC | 2.14 (1.27, 3.61) | 0.0043 |

| Others | 2.20 (1.00, 4.82) | 0.0488 |

| COPD | ||

| No | Ref. | |

| Yes | 1.05 (0.55, 2.01) | 0.8727 |

| Hypertension | ||

| No | Ref. | |

| Yes | 1.11 (0.76, 1.61) | 0.5995 |

| Diabetes | ||

| No | Ref. | |

| Yes | 0.89 (0.42, 1.88) | 0.7575 |

| CHD | ||

| No | Ref. | |

| Yes | 1.14 (0.46, 2.84) | 0.7736 |

| Triglyceride (mmol/L) | 0.80 (0.62, 1.04) | 0.1018 |

| TC (mmol/L) | 0.93 (0.78, 1.11) | 0.4113 |

| HDL-C (mmol/L) | 0.56 (0.34, 0.94) | 0.0270 |

| LDL-C (mmol/L) | 0.89 (0.71, 1.11) | 0.3031 |

| Apo E (mg/dL) | 0.91 (0.82, 1.02) | 0.1153 |

| Apo B (g/L) | 0.80 (0.45, 1.42) | 0.4421 |

| Homocysteine (μmol/L) | 1.00 (0.98, 1.02) | 0.8840 |

| WBC (×109/L) | 1.03 (0.98, 1.08) | 0.2477 |

| Neutrophils (×109/L) | 1.04 (0.99, 1.10) | 0.0937 |

| Hemoglobin (g/L) | 1.00 (0.99, 1.01) | 0.4135 |

| Platelets (×109/L) | 1.00 (1.00, 1.00) | 0.2392 |

| CRP (mg/L) | 1.01 (1.00, 1.01) | 0.0173 |

| PT (S) | 0.93 (0.84, 1.02) | 0.1220 |

| APTT (S) | 0.96 (0.94, 0.99) | 0.0180 |

| ALT (IU/L) | 1.00 (0.99, 1.01) | 0.8181 |

| AST (IU/L) | 1.00 (0.99, 1.01) | 0.9365 |

EBB endobronchial biopsy; SCLC small-cell lung carcinoma; COPD Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CHD coronary heart disease; TC total cholesterol; HDL-C high density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C low density lipoprotein cholesterol; Apo, apolipoprotein; WBC white blood cell; CRP C-reactive protein; PT prothrombin time; APTT activated partial thromboplastin time; ALT alanine aminotransferase; AST aspartate aminotransferase

Fig. 1.

The strength of association between variables with EBB-induced bleeding in the LASSO regression method. a Tuning variable (lambda) selection using 10-fold cross-validation in the LASSO regression. Dotted vertical lines were drawn at the optimal values based on the minimum criteria (left dotted line) and the 1-SE criteria (right dotted line). b A coefficient profile plot was produced against the log (lambda) sequence. In the current study, variables were filtered according to the minimum criteria (left dotted line), where optimal lambda resulted in 7 nonzero coefficients, including HDL-C (− 0.0527), APTT (− 0.0146), neutrophils (0.0024), CRP (0.0015), lesion location (0.6728), TNM stage (− 0.3905) and histological types (− 0.4902). SE = standard error

The association between plasma HDL-C and EBB-induced bleeding risk was shown in Table 3 after adjusting for smoking, histological type, stage of cancer, triglyceride, PT, APTT and CRP (adjust criterion I), or after adjusting for sex, age, smoking, location of lesion, histological type, stage of cancer, triglyceride, apolipoprotein E, PT, APTT, neutrophils and CRP (adjust criterion II). In piecewise analysis, we found that middle concentrations of HDL-C (1.5–2.0 mmol/L) associated with a decreased risk of EBB-induced bleeding when compared to lower concentrations (< 1.5 mmol/L) (odds ratio [OR], 0.39; 95% CI, 0.20–0.74; P < 0.05). However, higher concentrations of HDL-C (≧ 2.0 mmol/L) did not associate with a decreased incidence of EBB-induced bleeding (OR, 1.63; 95% CI, 0.51–5.22; P > 0.05).

Table 3.

Multivariate regression analysis of HDL-C with the risk of EBB-induced bleeding

| HDL-C (mmol/L) | EBB-induced bleeding OR (95% CI) P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-adjust | Adjust Ia | Adjust IIb | |

| < 1.5 | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| 1.5–2.0 | 0.35 (0.19, 0.64) 0.0007 | 0.38 (0.20, 0.71) 0.0026 | 0.39 (0.20, 0.74) 0.0042 |

| ≧2.0 | 1.55 (0.54, 4.48) 0.4187 | 1.95 (0.65, 5.88) 0.2339 | 1.63 (0.51, 5.22) 0.4107 |

aAdjust I adjust for: smoking, histological type, stage of cancer, triglyceride, PT, APTT and CRP

bAdjust II adjust for: sex, age, smoking, location of lesion, histological type, stage of cancer, triglyceride, apolipoprotein E, PT, APTT, neutrophils and CRP. EBB, endobronchial biopsy; HDL-C, high density lipoprotein cholesterol; PT, prothrombin time; APTT, activated partial thromboplastin time; CRP, C-reactive protein

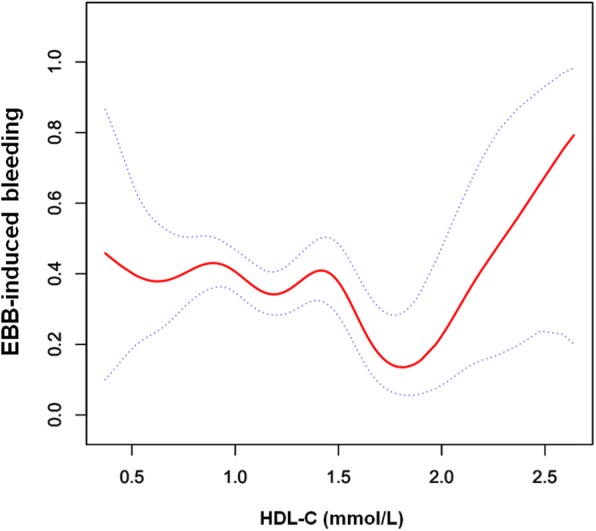

A non-linear relationship between plasma HDL-C levels and the risk of EBB-induced bleeding was observed in the smooth curve fitting (Fig. 2). Two threshold values (inflection point I = 1.4 mmol/L, and inflection point II = 1.9 mmol/L) were detected between plasma HDL-C levels and EBB-induced bleeding risk in two-piecewise linear regression analysis (Table 4).

Fig. 2.

A non-linear relationship with threshold effect between plasma HDL-C concentrations and EBB-induced bleeding risk in the smooth curve fitting after adjusting the potential confounding factors (sex, age, smoking, location of lesion, histological type, stage of cancer, triglyceride, apolipoprotein E, PT, APTT, neutrophils and CRP) is shown in the figure. Dotted lines represent the upper and lower 95% confidence intervals. EBB = endobronchial biopsy; HDL-C = high density lipoprotein cholesterol; PT = prothrombin time; APTT = activated partial thromboplastin time; CRP = C-reactive protein

Table 4.

Threshold effect analysis of HDL-C on EBB-induced bleeding using two-piecewise linear regression

| Inflection point of HDL-C (mmol/L) | EBB-induced Bleedinga | |

|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P value | |

| Inflection point I | ||

| < 1.4 | 1.03 (0.42, 2.51) | 0.9554 |

| > 1.4 | 0.02 (0.00, 0.41) | 0.0118 |

| Inflection point II | ||

| < 1.9 | 0.49 (0.25, 0.95) | 0.0343 |

| > 1.9 | 19.99 (0.85, 470.30) | 0.0631 |

aAdjust for: sex, age, smoking, location of lesion, histological type, stage of cancer, triglyceride, apolipoprotein E, PT, APTT, neutrophils and CRP. EBB, endobronchial biopsy; HDL-C, high density lipoprotein cholesterol; PT, prothrombin time; APTT, activated partial thromboplastin time; CRP, C-reactive protein

Discussion

Our findings showed a statistically significant non-linear association between HDL-C level and risk of bleeding during EBB. Specifically, in order to reduce the risk of EBB-induced bleeding, especially for massive bleeding, it may be helpful to maintain the concentrations of plasma HDL-C within 1.5–2.0 mmol/L prior to aggressive biopsies on endobronchial exophytic lesions in patients with lung cancer.

Bronchoscopy-related bleeding is a very common complication in clinical practice, especially when biopsies are performed. Of note, malignant lesions reportedly are more likely to bleed upon biopsy than benign mucosal lesions [17], and the incidence of massive hemorrhage increases following EBB [18]. In this scenario, a number of studies have been conducted and several risk factors that may be associated with bleeding during bronchoscopy have been proposed, such as immunosuppressive state, thrombocytopenia (< 50 × 103/μl), anti-platelet or anti-coagulant drugs use, severe liver and kidney disorders, heart function failure, severe pulmonary arterial hypertension, and lung transplant [6–8]. However, most of the aforementioned factors remain conflicting or lack supporting evidence [9, 10]. To our knowledge, there is still no effective indicator or biomarker available for predicting bleeding risk during bronchoscopy in clinical practice.

HDLs are heterogeneous lipoproteins involve in multiple physiological and pathological processes in the human body [19]. During the last few decades, most studies conducted have demonstrated HDL-C as a protective factor in cardiovascular disease [19]. In recent year, several studies revealed that HDL-C was associated with the risk of hemorrhage in some disorders, especially in intracranial hemorrhage [13, 20]. In this regard, several studies have shown that the risk of intracerebral hemorrhage significantly increased with decreasing HDL-C concentrations [14, 15]. However, in a meta-analysis of 1,430,141 participants from 23 prospective studies, the inverse relationship between intracerebral hemorrhage and HDL-C was pointed out by researchers [13]. Despite the fact that the relationship between HDL-C and the risk of intracerebral hemorrhage remains controversial, these studies, at least, have indicated that HDL-C may be associated with the risk of bleeding in some disorders.

The current knowledge in the realm of the effect of HDL on coagulation and clotting cascade remains lacking. Adiponectin, an adipose-derived cytokine, may partially explain the effect of HDL on coagulation. Several studies have demonstrated that, both in vitro and in vivo, HDL associates strongly with adiponectin [21–23]. Reportedly, adiponectin could affect platelet hyperactivity, hypercoagulability, and hypofibrinolysis [24–26]. It plays an anticoagulant role by increasing the expression of plasminogen activator inhibitor (PAI)-I both in human and in animal models [27–30]. Therefore, the effect of HDL on coagulation may be mediated partially through the suppressive effect of adiponectin on PAI-I production. In addition, HDL could modulate the function of vascular smooth muscle and platelets [31, 32].

The present study found that plasma HDL-C concentrations strongly associated with the incidence of EBB-induced bleeding in LASSO regression analysis, which is considered to surpass the approach of identifying variables based on the strength of their univariable association with the outcome, especially when there are a bunch of variables [33, 34]. This association still strengthened after controlling for potentially confounding variables (adjust I controlling for: smoking, histological type, stage of cancer, triglyceride, PT, APTT and CRP; adjust II controlling for: sex, age, smoking, location of lesion, histological type, stage of cancer, triglyceride, apolipoprotein E, PT, APTT, neutrophils and CRP) in in multiple regression analysis. There was a non-linear association between plasma HDL-C levels and EBB-induced bleeding risk. We further uncovered a piecewise effect of HDL-C concentrations against the risk of EBB-induced bleeding. Between 1.5–2.0 mmol/L, HDL-C was associated with lower bleeding risk, whereas higher (> 2.0 mmol/L) or lower (< 1.5 mmol/L) concentrations of HDL-C were associated with increased EBB-induced bleeding risk. This finding may increase our understanding of the novel role of HDL-C.

The current study is the first to reveal the relationship between plasma HDL-C levels and EBB-induced bleeding risk during bronchoscopy. However, several limitations of the present study are worth noting. First, although we had adjusted for potentially confounding factors, this study was inevitably subject to the limitations of the use of observational data. Second, a quantitative measurement of the volume of EBB-induced bleeding in our study was unavailable. It remains challenging to accurately measure bleeding during bronchoscopy [35]. Therefore, the grouping of biopsy bleeding may not be accurate in this study because we divided participants into a bleeding group or a non-bleeding group based only on whether they received hemostasis during EBB. Third, we only collected HDL-C concentrations at admission, and repeated measurements were unavailable in the retrospective data. Therefore, further validation in prospective studies is warranted. Despite these limitations, this study has notable clinical implications since no effective indicator for EBB-induced bleeding has been found to date.

Conclusions

This study revealed that plasma HDL-C levels are associated with EBB-induced bleeding risk in a non-linear pattern in patients with lung cancer, and the relative safe concentrations of plasma HDL-C on EBB bleeding may be 1.5–2.0 mmol/L. This finding highlights the importance of HDL-C concentrations on EBB and may have implications for bleeding risk assessment and risk modification prior to EBB. Future studies are needed to fully evaluate the effect of HDL-C on EBB-induced bleeding and investigate the underlying mechanisms.

Acknowledgements

We appreciate the help and support of all the participants involved in the study.

Funding

This study was supported by the Medical and Health Science and Technology Plan Project of Zhejiang Province (No. 2018RC079 to S. W.), the Youth Research Fund of Jinhua Hospital of Zhejiang University (No. JY2017205 to S. W.), the Science and Technology Key Project of Jinhua City (No. 20163011 to S. W.), and the Chinese Medicine Science and Technology project of Jinhua City (No. 2017jzk05 to S. W).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ALT

Alanine aminotransferase

- APC

Argon plasma coagulation

- APTT

Activated partial thromboplastin time

- AST

Aspartate aminotransferase

- CHD

Coronary heart disease

- CI

Confidence interval

- COPD

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- CRP

C-reactive protein

- EBB

Endobronchial biopsy

- HDL-C

High density lipoprotein cholesterol

- LASSO

The least absolute shrinkage and selection operator

- LDL-C

Low density lipoprotein cholesterol

- OR

Odds ratio

- PAI

Plasminogen activator inhibitor

- PT

Prothrombin time

- TC

Total cholesterol

- WBC

White blood cell

Authors’ contributions

S. W. contributed substantially to the study design, data analysis and interpretation, the writing of the manuscript, and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. J. Z. and X. L. contributed to data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, and manuscript revision.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the ethics committee of Jinhua Hospital of Zhejiang University. The requirement for informed consent was waived because the data were handled anonymously.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Saibin Wang, Phone: +86 579 82552278, Email: saibinwang@hotmail.com.

Jingcheng Zhang, Email: zjc1983@126.com.

Xiaodong Lu, Phone: +86 579 82552083, Email: xiaodongau@126.com.

References

- 1.Rivera MP, Mehta AC, Wahidi MM. Establishing the diagnosis of lung cancer: diagnosis and management of lung cancer, 3rd ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2013;143:e142S–e165S. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-2353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Herth FJF. Bronchoscopy and bleeding risk. Eur Respir Rev. 2017;26:170052. doi: 10.1183/16000617.0052-2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chinsky K. Bleeding risk and bronchoscopy: in search of the evidence in evidence-based medicine. Chest. 2005;127:1875–1877. doi: 10.1378/chest.127.6.1875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fallon J, Medford ARL. Endobronchial and transbronchial biopsy experience: a United Kingdom survey. Thorac Cancer. 2017;8:291–295. doi: 10.1111/1759-7714.12439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang S, Ye Q, Tu J, Song Y. The location, histological type and stage of lung cancer are associated with bleeding during endobronchial biopsy. Cancer Manag Res. 2018;10:1251–1257. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S164315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Herth FJ, Becker HD, Ern A. Aspirin does not increase bleeding complications after transbronchial biopsy. Chest. 2002;122:1461–1464. doi: 10.1378/chest.122.4.1461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Diette GB, Wiener CM, White P., Jr The higher risk of bleeding in lung transplant recipients from bronchoscopy is independent of traditional bleeding risks: results of a prospective cohort study. Chest. 1999;115:397–402. doi: 10.1378/chest.115.2.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brickey DA, Lawlor DP. Transbronchial biopsy in the presence of profound elevation of the international normalized ratio. Chest. 1999;115:1667–1671. doi: 10.1378/chest.115.6.1667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carr IM, Koegelenberg CF, von Groote-Bidlingmaier F, Mowlana A, Silos K, Haverman T, Diacona AH, Bolligeret CT. Blood loss during flexible bronchoscopy: a prospective observational study. Respiration. 2012;84:312–318. doi: 10.1159/000339507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zahreddine I, Atassi K, Fuhrman C. Impact of prior biological assessment of coagulation on the hemorrhagic risk of fiberoptic bronchoscopy. Rev Mal Respir. 2003;20:341–346. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Otocka-Kmiecik A, Mikhailidis DP, Nicholls SJ, Davidson M, Rysz J, Dysfunctional BM. HDL: a novel important diagnostic and therapeutic target in cardiovascular disease? Prog Lipid Res. 2012;51:314–324. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2012.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Catapano AL, Pirillo A, Bonacina F, Norata GD. HDL in innate and adaptive immunity. Cardiovasc Res. 2014;103:372–383. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvu150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang X, Dong Y, Qi X, Huang C, Hou L. Cholesterol levels and risk of hemorrhagic stroke: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Stroke. 2013;44:1833–1839. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.001326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang X, Li S, Bai Y, Fan X, Sun K, Wang J, Hui R. Inverse association of plasma level of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol with intracerebral hemorrhage. J Lipid Res. 2011;52:1747–1754. doi: 10.1194/jlr.P008755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang Y, Tuomilehto J, Jousilahti P, Wang Y, Antikainen R, Hu G. Total and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and stroke risk. Stroke. 2012;43:1768–1774. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.646778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rivera MP, Detterbeck F, Mehta AC. Diagnosis of lung cancer: the guidelines. Chest. 2003;123:129S–136S. doi: 10.1378/chest.123.1_suppl.129S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ozgül MA, Turna A, Yildiz P, Ertan E, Kahraman S, Yilmaz V. Risk factors and recurrence patterns in 203 patients with hemoptysis. Tuberk Toraks. 2006;54:243–248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jin F, Mu D, Chu D, Fu E, Xie Y, Liu T. Severe complications of bronchoscopy. Respiration. 2008;76:429–433. doi: 10.1159/000151656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pirro M, Ricciuti B, Rader DJ, Catapano AL, Sahebkar A, Banach M. High density lipoprotein cholesterol and cancer: marker or causative? Prog Lipid Res. 2018;71:54–69. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2018.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chang JJ, Katsanos AH, Khorchid Y, Dillard K, Kerro A, Burgess LG, Goyal N, Alexandrov AW, Alexandrov AV, Tsivgoulis G. Higher low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels are associated with decreased mortality in patients with intracerebral hemorrhage. Atherosclerosis. 2018;269:14–20. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2017.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cnop M, Havel PJ, Utzschneider KM, Carr DB, Sinha MK, Boyko EJ, Retzlaff BM, Knopp RH, Brunzell JD, Kahn SE. Relationship of adiponectin to body fat distribution, insulin sensitivity and plasma lipoproteins: evidence for independent roles of age and sex. Diabetologia. 2003;46:459–469. doi: 10.1007/s00125-003-1074-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weiss R, Otvos JD, Flyvbjerg A, Miserez AR, Frystyk J, Sinnreich R, Kark JD. Adiponectin and lipoprotein particle size. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:1317–1319. doi: 10.2337/dc09-0084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ocak N, Dirican M, Ersoy A, Sarandol E. Adiponectin, leptin, nitric oxide, and C-reactive protein levels in kidney transplant recipients: comparison with the hemodialysis and chronic renal failure. Ren Fail. 2016;38:1639–1646. doi: 10.1080/0886022X.2016.1229965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Darvall KA, Sam RC, Silverman SH, Bradbury AW, Adam DJ. Obesity and thrombosis. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2007;33:223–233. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2006.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim CK, Cho DH, Lee KS, Lee DK, Park CW, Kim WG, Lee SJ, Ha KS, Goo Taeg O, Kwon YG, et al. Ginseng berry extract prevents atherogenesis via anti-inflammatory action by upregulating phase II gene expression. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2012;490301:2012. doi: 10.1155/2012/490301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eriksson M, Johnson O, Boman K, Hallmans G, Hellsten G, Nilsson TK, Soderberg S. Improved fibrinolytic activity during exercise may be an effect of the adipocyte-derived hormones leptin and adiponectin. Thromb Res. 2008;122:701–708. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2008.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hoo RL, Chow WS, Yau MH, Xu A, Tso AW, Tse HF, Fong CH, Tam S, Chan L, Lam KS. Adiponectin mediates the suppressive effect of rosiglitazone on plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 production. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:2777–2782. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.152462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lowe GD, Danesh J, Lewington S, Walker M, Lennon L, Thomson A, Rumley A, Whincup PH. Tissue plasminogen activator antigen and coronary heart disease: prospective study and meta-analysis. Eur Heart J. 2004;25:252–259. doi: 10.1016/j.ehj.2003.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goldberg RB, Temprosa M, Mele L, Orchard T, Mather K, Bray G, Horton E, Kitabchi A, Krakoff J, Marcovina S, et al. Change in adiponectin explains most of the change in HDL particles induced by lifestyle intervention but not metformin treatment in the diabetes prevention program. Metabolism. 2016;65:764–775. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2015.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Raiko JR, Oikonen M, Wendelin-Saarenhovi M, Siitonen N, Kähönen M, Lehtimäki T, Viikari J, Jula A, Loo BM, Huupponen R, et al. Plasminogen activator inhitor-1 associates with cardiovascular risk factors in healthy young adults in the cardiovascular risk in young Finns study. Atherosclerosis. 2012;224:208–212. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2012.06.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Naqvi TZ, Shah PK, Ivey PA, Molloy MD, Thomas AM, Panicker S, Ahmed A, Cercek B, Kaul S. Evidence that high-density lipoprotein cholesterol is an independent predictor of acute plateletdependent thrombus formation. Am J Cardiol. 1999;84:1011–1017. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9149(99)00489-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mineo C, Shaul PW. Novel biological functions of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol. Circ Res. 2012;111:1079–1090. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.258673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huang YQ, Liang CH, He L, Tian J, Liang CS, Chen X, Ma ZL, Liu ZY. Development and validation of a radiomics nomogram for preoperative prediction of lymph node metastasis in colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:2157–2164. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.65.9128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tibshirani R. The lasso method for variable selection in the cox model. Stat Med. 1997;16:385–395. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0258(19970228)16:4<385::AID-SIM380>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schumann C, Hetzel M, Babiak AJ, Hetzel J, Merk T, Wibmer T, Lepper PM, Krüger S. Endobronchial tumor debulking with a flexible cryoprobe for immediate treatment of malignant stenosis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;139:997–1000. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2009.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.