Abstract

Background

Burnout has become endemic in medicine, across all specialties and levels of training. Grit, defined as “perseverance and passion for long‐term goals,” attempts to quantify the ability to maintain sustained effort throughout an extended length of time. Our objective is to assess burnout and well‐being and examine their relationship with the character trait, grit, in emergency medicine residents.

Methods

In Fall 2016, we conducted a multicenter cross‐sectional survey at five large, urban, academically affiliated emergency departments. Residents were invited to anonymously provide responses to three validated survey instruments; the Short Grit Scale, the Maslach Burnout Inventory, and the World Health Organization‐5 Well‐Being Index.

Results

A total of 222 residents completed the survey (response rate = 86%). A total of 173 residents (77.9%) met criteria for burnout and 107 residents (48.2%) met criteria for low well‐being. Residents meeting criteria for burnout and low well‐being had significantly lower mean grit scores than those that did not meet criteria. Residents with high grit scores had lower odds of experiencing burnout and low well‐being (odds ratio [OR] = 0.26, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.46–0.85; and [OR] = 0.33, 95% CI = 0.16–0.72, respectively). Residents with low grit scores were more likely to experience burnout and more likely to have low well‐being (OR = 6.17, 95% CI = 1.43–26.64; and OR = 2.76, 95% CI = 1.31–5.79, respectively).

Conclusion

A significant relationship exists between grit, burnout, and well‐being. Residents with high grit appear to be less likely to experience burnout and low well‐being while those with low grit are more likely to experience burnout and low well‐being.

Burnout is defined as a prolonged response to chronic emotional and interpersonal stressors on the job defined by three dimensions: emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and a sense of reduced personal accomplishment.1 It affects physicians at every level of training, from medical school to practicing clinicians. At the start of residency, well‐being measures in residents are consistent with findings in medical school.2, 3 However, after entering training, residents’ depression and burnout rates increase significantly compared to their peers.2, 3 Literature evaluating stress during medical education has been well documented with studies primarily focusing on negative factors such as depression, burnout, and bullying in an effort to determine overall well‐being.3 Burnout and fatigue have also been associated with undesirable patient‐care outcomes. Residents with high burnout scores were more likely to report making errors and providing a subsatisfactory level of patient care.4

Grit, a novel personality trait, is defined as “perseverance and passion for long‐term goals,” and attempts to quantify the ability of an individual to maintain sustained effort throughout an extended length of time.5 Grit has been found to be a superior predictor of success in several high‐stress, high‐achievement fields.5, 6 Prior work revealed that low grit was an accurate predictor of attrition in cadets at the United States Military Academy. In fact, grit was a superior predictor than measures of standard intelligence (test scores and intelligence quotient).5 Additionally, gritty adult learners reach higher educational achievements, and gritty teachers are more likely to retain their jobs and instill higher academic performance in students.5, 7 Grit and resilience have also been offered as a possible explanations for success in health professional students who succeed in the face of pressure.8

In medical education, higher grit scores correlated with higher performance in historically difficult courses (gross anatomy)9 and residents with below‐median grit were more than twice as likely to consider leaving surgical residency training.10 Furthermore, grit has also been shown to be related to resident wellness and burnout in surgical training. Grit was predictive of later psychological well‐being as measured by the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) and the Psychological General Well‐Being Scale.11

Grit appears to be an important personality characteristic that is key to success in high‐stress professions. However, burnout and depression also seem to plague these same high‐stress professions. With the growing concern for burnout and depression among physicians, evaluating factors that are related to the mental health and professional success is of utmost importance. Grit predicts success in part by promoting self‐control, thus allowing people to persist in repetitive, tedious, or frustrating behaviors that are necessary for success.12 Residency is an exhaustive and stressful time during medical training. Passion, perseverance, and resilience could play an important role protecting against burnout and depression in residency training. The objective of this study was to assess burnout and well‐being and to examine their relationship with the character trait grit in emergency medicine (EM) residents.

Methods

In Fall 2016, we performed a multicenter, cross‐sectional study of EM residents from five training programs accredited by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education and/or the American Osteopathic Association. The institutional review board at each institution approved the study.

Residents from both EM 1–3 and 1–4 U.S. training programs were invited to participate in an anonymous electronic questionnaire using the SurveyMonkey online survey tool. Participants were assigned a study number at random and sent reminder e‐mails on a weekly basis for 3 consecutive weeks. The survey contained three distinct assessments: the MBI, the World Health Organization‐5 (WHO‐5) Well‐Being Index and the Short Grit Scale (Grit‐s). Residents completed the MBI, a 22‐item rating scale designed to assess three aspects of the burnout syndrome: emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and lack of personal accomplishment. The MBI has well‐established discriminant and convergent validity, and three‐factor analysis has shown it to be invariant among different groups, including residents.13 The WHO‐5 Well‐Being Index scores are based on a maximum of 25, and scores below 13 suggest poor mental well‐being. It has been recently used in residents,14 and there is validity evidence from other groups.15 The Grit‐s is a validated, eight‐item questionnaire. It is scored on a 5‐point scale from 1 (not at all like me) to 5 (very much like me) with four questions being reverse scored. The summed score is then divided by 8 to give a final score. Higher scores indicate higher levels of grit.6 Analogous to Duckworth et al.,5 we defined high grit as having a grit score greater than 1 SD from the cohort mean and low grit as having a grit score less than 1 SD from the cohort mean.

All data were sent to a central location where individual surveys were coded and scored. Burnout was further dichotomized into yes/no, with overall burnout defined as meeting the MBI definitions of high emotional exhaustion, high depersonalization, and/or low personal accomplishment.16, 17, 18 Categorical variables were summarized using frequency and percentage and continuous variables were summarized using mean ± SD. Rates of burnout by PGY level, sex, and grit were compared using chi‐square test and an ANCOVA model was used to assess their relative contribution to the outcomes of interest. All tests were two‐sided and significance was defined as p < 0.05. All comparisons were performed using SAS version 9 (SAS Institute) and/or Stata version 15.1 (StatCorp).

Results

There were 258 eligible residents and a total of 222 residents completed the survey (response rate = 86%). Demographic characteristics and results on the assessment tools are reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

MBI, WHO‐5 Well‐being, and Grit Scoring Results in EM Residents

| Variable | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Total | 222 | |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 150 | 67.6 |

| Female | 70 | 31.5 |

| Other | 2 | 0.01 |

| PGY | ||

| 1 | 61 | 27.5 |

| 2 | 60 | 27.0 |

| 3 | 55 | 24.8 |

| 4 | 46 | 20.7 |

| Emotional exhaustion | ||

| High | 105 | 47.3 |

| Moderate | 79 | 35.6 |

| Low | 38 | 17.1 |

| Depersonalization | ||

| High | 137 | 61.7 |

| Moderate | 61 | 27.5 |

| Low | 24 | 10.8 |

| Personal accomplishment | ||

| High | 101 | 45.5 |

| Moderate | 62 | 27.9 |

| Low | 59 | 26.6 |

| Overall burnout | ||

| Yes | 165 | 74.3 |

| No | 57 | 25.7 |

| Low well‐being | ||

| Yes | 107 | 48.2 |

| No | 115 | 51.8 |

| Grit | ||

| High | 40 | 18.0 |

| Moderate | 144 | 64.9 |

| Low | 38 | 17.1 |

MBI = Maslach Burnout Inventory; WHO‐5 = World Health Organization‐5.

The mean (±SD) grit score was 3.57 (±0.54) in our cohort. Controlling for sex and program level, grit had significant inverse correlations with the emotional exhaustion (r = –0.28, p < 0.001) and depersonalization (r = –0.35, p < 0.001) dimensions of burnout and significant positive correlations with the personal accomplishment (r = 0.30, p < 0.001) dimension of burnout and the WHO‐5 Well‐Being Scale (r = 0.24, p < 0.001).

The grit score for PGY‐1 was significantly higher than that for PGY‐2 (p < 0.05); however, there were no other differences in mean grit scores between other PGY levels. There were no differences in mean grit score between males and females. Furthermore, the rates of high, moderate, and low grit scores did not differ by PGY level or sex (Table 2).

Table 2.

Prevalence Rates of High, Moderate, and Low Grit by PGY Level and Sex in EM Residents

| High Grit | Moderate Grit | Low Grit | p‐value (chi‐square) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PGY | ||||

| 1 | 27.9 (17) | 62.3 (38) | 9.8 (6) | 0.19 |

| 2 | 11.7 (7) | 65.0 (39) | 23.3 (14) | |

| 3 | 14.5 (8) | 69.1 (38) | 16.4 (9) | |

| 4 | 17.4 (8) | 63.0 (29) | 19.6 (9) | |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 15.3 (23) | 66.0 (99) | 18.7 (28) | 0.35 |

| Female | 22.9 (16) | 62.9 (44) | 14.3 (10) | |

Data are reported as % (n).

High grit was defined as being 1 SD greater than the cohort mean and low grit was defined as being greater than 1 SD below the cohort mean. Moderate grit was defined as being less than 1 SD from the cohort mean.5

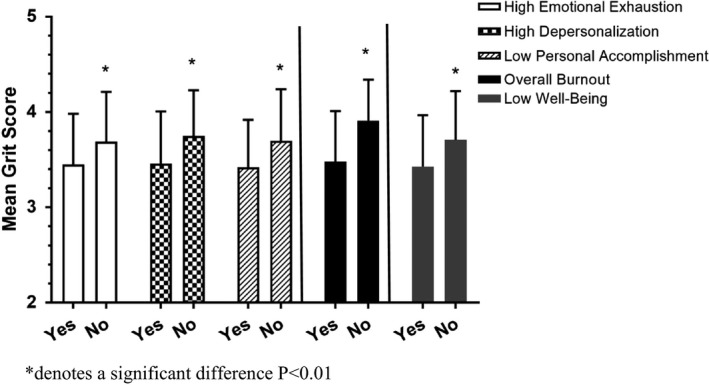

The mean grit score of residents who met criteria for burnout was significantly lower than residents who did not meet the criteria for burnout. Similarly, residents who met the criteria for low well‐being had a significantly lower mean grit score than residents who did not meet the criteria for low well‐being (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Mean grit scores in EM residents who meet the criteria for burnout and low well‐being (yes) compared to residents who do not meet the criteria for burnout and low well‐being (no). *p < 0.01.

To further evaluate this relationship, we compared the prevalence rates of burnout and well‐being by PGY level, sex, and grit. PGY level was associated with higher scores for emotional exhaustion; however, rates of depersonalization, low personal accomplishment, and low well‐being were not. While rates of low well‐being were significantly higher in female residents compared to males, there was no significant relationship between burnout and sex. All components of burnout and low well‐being differed significantly by grit level. Those with high grit had lower rates of burnout and low well‐being while residents with low grit had higher rates of burnout and low well‐being (Table 3).

Table 3.

Prevalence Rates of Burnout and Low Well‐being and Their Relationship With PGY Level, Sex, and Grit in EM Residents

| Emotional Exhaustion | Depersonalization | Personal Accomplishment | Overall Burnout | Low Well‐being | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % (n) | p‐value | % (n) | p‐value | % (n) | p‐value | % (n) | p‐value | % (n) | p‐value | |

| PGY | <0.01 | 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.05 | 0.09 | |||||

| 1 | 34.4 (21) | 54.1 (33) | 14.8 (9) | 63.9 (39) | 39.3 (24) | |||||

| 2 | 66.7 (40) | 70.0 (42) | 28.3 (17) | 81.7 (49) | 56.7 (34) | |||||

| 3 | 56.4 (31) | 72.7 (40) | 32.7 (18) | 87.3 (48) | 56.4 (31) | |||||

| 4 | 28.3 (13) | 47.8 (22) | 32.6 (15) | 63.0 (29) | 39.1 (18) | |||||

| Sex | 0.59 | 0.10 | 0.74 | 0.62 | <0.01 | |||||

| Male | 44.7 (67) | 64.7 (97) | 27.3 (41) | 75.5 (113) | 40.0 (60) | |||||

| Female | 53.2 (36) | 56.5 (39) | 24.6 (17) | 72.5 (50) | 69.6 (48) | |||||

| Grit | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | |||||

| High | 30.0 (12) | 47.5 (19) | 10 (4) | 50 (20) | 27.5 (11) | |||||

| Moderate | 47.9 (69) | 61.1 (88) | 24.3 (35) | 75.7 (109) | 48.6 (70) | |||||

| Low | 63.2 (24) | 78.9 (30) | 52.6 (20) | 94.7 (36) | 68.4 (26) | |||||

p‐values determined by chi‐square test.

We further examined grit by determining the odds of experiencing burnout and low well‐being for those meeting criteria for high and low grit scores. Residents with high grit scores were less likely to experience burnout and low well‐being (OR = 0.26, 95% CI = 0.46–0.85; and OR = 0.33, 95% CI = 0.16–0.72, respectively). Residents with low grit scores were more likely to experience burnout and low well‐being (OR = 7.67, 95% CI = 2.06–33.21; and OR = 2.76, 95% CI = 1.31–5.79, respectively).

Discussion

This is the first study to examine the character trait of grit and its association with burnout and well‐being in EM residents. We report a high level of burnout among residents that was not related to level of training or sex. The prevalence of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization were within the ranges documented in previously published studies.16 Our study participants reported a lower sense of personal accomplishments when compared to internal medical residents,16 but not as dramatic as findings reported in another cohort of EM residents.15 When we dichotomized burnout into yes/no, a method previously used in the literature,17, 18 the rate of burnout in EM residents was consistent with that in prior studies.16

We found the median grit score in EM residents to be higher than the median grit score in the general population.5 Resident grit was estimated to be was slightly lower than that reported in surgical residents10, 11, 19 but higher than that of attending physicians across multiple specialties.20 Notably, grit appears to predict burnout and psychological well‐being in EM residents. Residents that were experiencing burnout had significantly lower mean grit scores compared to those not experiencing burnout. This was true across all three subcategories of burnout as well as overall burnout. We also found that residents who screened positive for low well‐being had significantly lower mean grit scores. The prevalence of burnout and low well‐being were lower in residents with higher grit.

Our findings suggest that grit may be able to identify residents who are at greatest risk for burnout, low psychological well‐being, and depression. Unlike the MBI and WHO‐5, the short grit scale is easy to administer and short and does not contain any sensitive questions that residents may be hesitant to answer for program directors. Program directors could use the short grit scale to identify residents early on in training who may benefit from intervention to provide psychological support and improve resilience. Early intervention during training to improve perseverance and passion for long‐term goals could contribute to future professional success and may limit physician burnout.

Limitations

Our study had several limitations. This cross‐sectional study represents a snapshot in time. We can only report a correlation between the variables assessed. To date, there are no long‐term studies that follow grit over time during medical training. It is possible that grit may change over the course residency. In addition, the residency programs involved in the research represent a convenience sample. They are all located in the northeastern United States and therefore the generalizability of the findings may be limited. Although our response rate was high, it is possible that response bias contributed to our findings and that residents suffering with more severe burnout symptoms participated in the study. This was a self‐assessment survey, and while it was anonymous it may have suffered from reporter's response bias. Residents may have felt pressured to respond to sensitive questions with answers they felt their program director would believe is most appropriate. Finally, burnout and low well‐being have also been shown to be affected by other factors not controlled for in this study. Factors such as marital status, job satisfaction, level of professional autonomy, and anxiety levels have been shown to be related to rates of burnout.18, 19, 20

Grit may be an important character trait for residency directors to consider during the residency candidate selection process. While attrition is not prevalent in EM, high stress has led to one of the highest levels of burnout in the medical field. Gritty residents may be more resistant to burnout and low well‐being, which can be beneficial for both the program and the psychological health of the residents. However, applying Grit‐s as a screening tool has limitations. Self‐reported questionnaire measures of grit have never been validated outside the low‐stakes context of confidential research. In cases of a high‐stakes recruitment or selection process participants may misrepresent themselves. Robertson‐Kraft and Duckworth7 developed and evaluated an objective method to assess grit in teachers by examining extracurricular activities and work experiences. Higher objective grit scores were correlated with success at reaching tenure. This more objective method may be a useful way to evaluate grit on potential residency candidates and warrants further analysis.21

Conclusions

Burnout and low well‐being are prevalent in emergency medicine residents. We have identified a significant relationship between the character trait grit with resident burnout and well‐being. Emergency medicine residents with high grit appear less likely to experience burnout and low well‐being. Inversely, residents with low grit appear more likely to experience burnout and low well‐being.

AEM Education and Training 2019;3:14–19

Presented at the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine Annual Meeting, Orlando, FL, May 16–19, 2017; and the Council of Emergency Medicine Residency Directors Academic Assembly, Ft. Lauderdale, FL, April 27–30, 2017.

The authors have no relevant financial information or potential conflicts to disclose.

Author Contributions: AD and TG—study concept and design; AD, TG, MH, and TP—acquisition of the data; AD and TG—analysis and interpretation of the data; AD—drafting of the manuscript; AD, TG, MH, and TP—critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; AD and TG—statistical expertise; AD, TG, MH, and TP—administrative, technical, or material support; and TG—study supervision.

References

- 1. Maslach C, Schaufeli WB, Leiter MP. Job burnout. Annu Rev Psychol 2001;52:397–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. American Medical Association . ACGME Seeks to Transform Residency to Foster Wellness. Available at: https://wire.ama-assn.org/education/acgme-seeks-transform-residency-foster-wellness. Accessed Sep 1, 2018.

- 3. Hurst C, Kahan D, Ruetalo M, et al. A year in transition: a qualitative study examining the trajectory of first year residents' well‐being. BMC Med Educ. 2013;13:96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Block L, Wu AW, Feldman L, Yeh HC, Desai SV. Residency schedule, burnout and patient care among first‐year residents. Postgrad Med J 2013;89:495–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Duckworth AL, Peterson C, Matthews MD, Kelly DR. Grit: perseverance and passion for long‐term goals. J Pers Soc Psychol 2007;92:1087–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Duckworth AL, Quinn PD. Development and validation of the short grit scale (grit‐s). J Pers Assess 2009;91:166–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Robertson‐Kraft C, Duckworth AL. True grit: trait‐level perseverance and passion for long‐term goals predicts effectiveness and retention among novice teachers. Teach Coll Rec (1970). 2014;116:http://www.tcrecord.org.ezproxy.med.cornell.edu/Content.asp?ContentId=17352. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Stoffel JM, Cain J. Review of grit and resilience literature within health professional education. AM J Pharm Educ 2018;82:124–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fillmore E, Helfenbein R. Medical student grit and performance in gross anatomy: what are the relationships. FASEB J 2015;29:Abstract 689.6. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Burkhart R, Tholey R, Guinto D, Yeo C, Chojnacki K. Grit: a marker of residents at risk for attrition? Surgery 2014;155:1014–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Salles A, Cohen G, Mueller C. The relationship between grit and resident well‐being. Am J Surg 2014;207:251–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Duckworth AL, Kirby TA, Tsukayama E, Berstein H, Ericsson KA. Deliberate practice spells success why grittier competitors triumph at the National Spelling Bee. Soc Psychol Pers Sci 2011;2:174–81. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rafferty JP, Lemkau JP, Purdy RR, Rudisill JR. Validity of the Maslach Burnout Inventory for family practice physicians. J Clin Psychol 1986;42:488–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kassam A, Horton J, Shoimer I, Patten S. Predictors of well‐being in resident physicians: a descriptive and psychometric study. J Grad Med Educ 2015;7:70–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Henkel V, Mergl R, Kohnen R, Allgaier AK, Moller HJ, Hegerl U. Use of brief depression screening tools in primary care: consideration of heterogeneity in performance in different patient groups. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2004;26:190–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Prins JT, Gazendam‐Donofrio SM, Tubben BJ, vander Heijden FM, van de Wiel HB, Hoekstra‐Weebers JE. Burnout in medical residents: a review. Med Educ 2007;41:788–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kimo Takayesu JK, Ramoska EA, Clark TR, et al. Factors associated with burnout during emergency medicine residency. Acad Emerg Med 2014;21:1031–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kuhn G, Goldberg R, Compton S. Tolerance for uncertainty, burnout, and satisfaction with the career of emergency medicine. Ann Emerg Med 2009;54:106–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Walker A, Hines J, Brecknell J. Survival of the grittiest? Consultant surgeons are significantly grittier than their junior trainees. J Surg Educ 2016;4:730–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Dyrbye LN, Burke SE, Hardeman RR, et al. Association of clinical specialty with symptoms of burnout and career choice regret among US resident physicians. JAMA 2018;320:1114–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Shih AF, Maroongroge S. The importance of grit in medical training. J Grad Med Educ 2017;9:399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]