Summary

N6-methyladenosine (m6A) was discovered 4 decades ago. However, the functions of m6A and the cellular machinery that regulates its changes have just been revealed in the last few years. m6A is an abundant internal mRNA modification on cellular RNA and is implicated in diverse cellular functions. Recent works have demonstrated the presence of m6A in the genomes of RNA viruses and transcripts of a DNA virus with either a proviral or antiviral role. Here, we first summarize what is known about the m6A “writers,” “erasers,” “readers,” and “antireaders” as well as the role of m6A in mRNA metabolism. We then review how the replications of numerous viruses are enhanced and restricted by m6A with emphasis on the oncogenic DNA virus, Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV), whose m6A epitranscriptome was recently mapped. In the context of KSHV, m6A and the reader protein YTHDF2 acts as an antiviral mechanism during viral lytic replication. During viral latency, KSHV alters m6A on genes that are implicated in cellular transformation and viral latency. Lastly, we discuss future studies that are important to further delineate the functions of m6A in KSHV latent and lytic replication and KSHV-induced oncogenesis.

Keywords: hepatitis C virus, HCV, human immunodeficiency virus, HIV, influenza A virus, IAV, Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus, KSHV, N6-methyladenosine, m6A, Zika virus, ZIKA

1 |. N6-METHYLADENOSINE STUDIES PRIOR TO NEXT GENERATION SEQUENCING

More than 100 posttranscriptional chemical modifications are present on RNA from all kingdoms of life. Most of these modifications are found on ribosomal RNA (rRNA) and transfer RNA (tRNA), which modulate their structures and functions, and hence translation, as they are accessory molecules in these processes.1 Messenger RNA (mRNA), which is primarily an information-bearing molecule, is also posttranscriptionally modified albeit with fewer types of modifications compared with other RNA species.1 Early studies on mRNA modifications revealed that N6-methyladenosine (m6A) was the most abundant internal modification on poly(A) RNA in hepatoma cells and mouse myeloma cells.2-4 m6A was subsequently detected in both adenovirus and influenza A virus (IAV) with an average of 3 m6A modifications per viral mRNA in IAV, a level that is similar to that of cellular m6A.5-7

Further studies in the 1970s to 1980s detected m6A in the RNA of human cancer cell lines, mouse white blood cells, bovine mRNA, mosquito cells, and in a variety of viruses that replicate in the nucleus such as herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1), Rous sarcoma virus (RSV), simian virus 40 (SV40), B77 avian sarcoma virus, and feline leukemia virus.3,4,8-28 These early studies showed that viral transcripts contain m6A levels similar to cellular RNA. Two studies mapped a cluster of 7 m6A bases on the src- and env-coding regions of RSV RNA at the single nucleotide level and revealed that each site was heterogeneously methylated, indicating different stoichiometries for each m6A site. These results suggested potential host-pathogen interactions that converge on viral RNA.9,18 It was also revealed that in cells infected by adenovirus, viral nuclear pre-mRNA had a higher level of m6A than viral cytoplasmic mRNA (2.5 vs 1.5 m6A bases/transcript), hinting that either m6A located in intronic regions is lost during splicing or m6A methylation of mRNA is a dynamic process.6,7 Since these early studies did not map m6A at the transcriptome-wide level, and no knowledge of the methyltransferases, demethylases, or m6A-binding proteins was available, the functions of m6A remained elusive for decades. Nevertheless, results of these studies have pointed to potential important roles of m6A in the life cycle of RNA and DNA viruses, which will be the focus of the current review.

2 |. NEXT GENERATION SEQUENCING UNRAVELS THE m6A EPITRANSCRIPTOME

Transcriptome-wide mapping of m6A was unavailable until N6-methyladenosine-sequencing (m6A-seq) was developed by 2 independent groups in 2012.29,30 In this technique, total RNA or poly(A)-selected RNA was isolated from cells and fragmented to approximately 100 nucleotides. Then, an m6A-specific antibody was used to pull down the fragmented RNA followed by deep sequencing of the immunoprecipitated and input fractions. m6A peaks on the transcripts were determined by comparing immunoprecipitated and input reads. Both studies found that m6A on cellular mRNA was enriched in the 3′ untranslated region (UTR) and with RRm6ACH motifs. As an epitranscriptomic mark, m6A was found on orthologous genes in both human and mouse cell lines.29 Analysis of methylated genes revealed enrichments of pathways related to RNA metabolism, transcriptional regulation, splicing, and developmental pathways.29,30 One difference between these two studies was that m6A was found to be enriched at the 5′UTR near the transcription start site in the Dominissini et al study but not in the Meyer et al study.29,30 This difference was attributed to different peak calling methods, but it could also be due to the limitation in m6A-seq, which is unable to distinguish m6A from another RNA modification, N6,2′-O-dimethyladenosine (m6Am), mostly found on the first few nucleotides of mRNA.29,31 Due to the resolution of m6A-seq, which is limited to 100 to 200 nucleotides, clusters of m6A within 200 nucleotides cannot be sufficiently resolved.

Since then, other techniques have been invented to overcome the limitations of m6A-seq (Table 1). One of them called photo-crosslinking-assisted m6A sequencing (PA-m6A-seq), which is involved with UV cross-linking the anti-m6A antibody to poly(A) RNA from cells grown in media containing the photoactivatable ribonucleosides, 4-thiouridine (4SU), or 6-thioguanosine (6SG), enhances the resolution to approximately 23 nucleotides.32 A few months later, a technique called m6A individual nucleotide resolution cross-linking and immuno-precipitation (miCLIP) was published, which enabled transcriptomewide mapping of m6A or m6Am at a single nucleotide resolution.33 This technique improved on previous techniques by UV cross-linking the anti-m6A antibody to RNA and then digesting all but a small part of the antibody in contact with the RNA using proteinase K. The remaining antibody fragment caused mutations during the preparation of a sequencing library, resulting in an antibody-dependent mutational signature or a truncation in sequencing reads close to m6A or m6Am sites. The truncations allow this technique to differentiate between m6A and m6Am. In contrast to m6A, m6Am is not found within the RRACH motif; instead, it is present around BCA motifs and mainly in the 5′UTR; thus, it is not able to generate the same mutational signature as m6A. Another technique, m6A level and isoform characterization sequencing (m6A-LAIC-seq), enables the quantification of the stoichiometry and identification of isoforms of methylated transcripts by using excess anti-m6A antibody to pull down full-length RNA.34 Deep sequencing of the pull down and flow-through fractions enables quantification of methylated vs unmethylated transcripts at the transcriptome-wide level, without site-specific mapping of m6A. They found diversity in m6A stoichiometry among different cell types and that methylation influences the choice of alternative polyadenylation sites. Another group capitalized on m6A's slight interference on A-T/A-U base pairing and developed a tiling microarray technique to detect m6A.35 Tiling RNA or DNA probes of 25 nucleotides in length complementary to the RNA sequences of interest was constructed and hybridized to the target RNA. This technique avoids the biases introduced by antibody-based techniques. However, it is less sensitive compared with the antibody-based techniques.

TABLE 1.

Comparison of current m6A transcriptome-wide profiling techniques

| Technique | Description | Advantages | Disadvantages | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| m6A-seq | Immunoprecipitation of fragmented RNA with an anti-m6A antibody followed by deep sequencing. | High sensitivity, widely adopted. | Resolution at 100-200 nucleotides; Does not discriminate between m6A and m6Am; False positives due to nonspecific antibody interactions. |

Dominissini et al29 and Meyer et al30 |

| PA-m6A-seq | Cells grown in 4SU or 6SG followed by UV cross-linking of isolated RNA to an anti-m6A antibody. Mutations generated during library preparation offer improved resolution over m6A-seq. | Approximately 23 nucleotide resolution. | Incorporation of 4SU or 6SG requires live cells; Does not discriminate between m6A and m6Am; False positives due to nonspecific antibody interactions. |

Chen et al32 |

| miCLIP | UV cross-linking of an anti-m6A antibody to RNA during the immunoprecipitation step results in mutations or truncations during the preparation of sequencing library; Detecting precise location of m6A/m6Am. |

Single nucleotide resolution; Can distinguish between m6A and m6Am. |

Mutational signature is dependent on antibody type; False positives due to nonspecific antibody interactions. |

Linder et al33 |

| m6A-LAIC-seq | Full-length RNA is immunoprecipitated with excess anti-m6A antibody followed by sequencing of immunoprecipitated and flowthrough fractions. | Identifies stoichiometry of m6A and methylated vs unmethylated isoforms. | Since full-length transcripts are used, site-specific detection of m6A is not possible. | Molinie et al34 |

| Microarray | A tiling array of RNA/DNA probes of 25 nucleotides complementary to RNA of interest is generated. m6A disrupts A-T or A-U base pairing, resulting in weaker hybridization with the probe. | Free from nonspecific interactions of antibody-based methods. | Low sensitivity. | Li et al35 |

To date, m6A, which is cotranscriptionally added to nascent RNA,36,37 has been shown to affect alternative splicing by promoting exon inclusion or skipping in a splice factor-dependent manner,38,39 nuclear export,40 both cap-dependent and cap-independent translations,41,42 miRNA biogenesis and binding,43,44 and P body-mediated RNA degradation.45,46

Using the modern techniques outlined above, evidence of dynamic regulation of the m6A epitranscriptome has been shown during DNA damage,47 heat shock,42,48 response to interferon-γ, stem cell differentiation,49-52 spermatogenesis and oogenesis,40,53-56 yeast sporulation,57 circadian rhythm,58 and plant development.59-61 In the remaining parts of the review, we discuss the role of cellular m6A machinery and regulation of viral replication of RNA and DNA viruses by cellular m6A machinery.

3 |. CELLULAR m6A MACHINERY

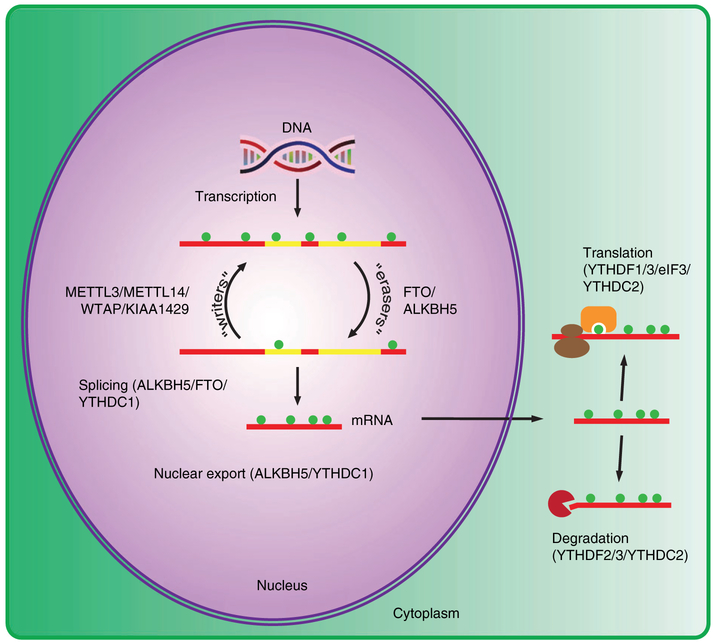

The cellular machinery driving the m6A dynamics can be divided into 4 main groups: methyltransferases or “writers,” demethylases or “erasers,” m6A-binding proteins or “readers,” and m6A-repelled proteins or “antireaders” (Figure 1). In humans, the m6A writer is a large, nearly 1 mega Dalton complex; however, only a few subunits have been identified to date—methyltransferase-like 3 (METTL3), methyltransferaselike 14 (METTL14), Wilms tumor 1–associating protein (WTAP), Vir-like m6A methyltransferase associated (KIAA1429), RNA-binding motif protein 15 (RBM15), and RNA-binding motif protein 15B (RBM15B).62-67 Of these subunits, METTL3 and METTL14 contain domains of methyltransferase, but only METTL3 is catalytically active. METTL14 forms a heterodimer with METTL3 and plays a role in substrate recognition.68,69 WTAP, KIAA1429, RBM15, and RBM15B function as regulatory subunits for this complex and are likely involved in the selective methylation of m6A sites.65,67 Knockdown of WTAP decreased the amount of METTL3 and METTL14 found in nuclear speckles, suggesting a possible role for WTAP in stabilizing the methyltransferase complex.66 Depletion of WTAP or KIAA1429 in the cell decreases the amount of m6A, and RBM15/RBM15B is required for methylation of the long noncoding RNA X inactive specific transcript (XIST).65-67 Since the RRACH motif is prevalent throughout the transcriptome, it is still not well understood how specificity for an m6A site is achieved in different physiological conditions. Under steady-state conditions, the methyltransferase complex is localized to the nucleus; however, METTL3 is also present in the cytoplasm of cancer cells and is associated with eIF3 to enhance translation.70 This demonstrates that the localization of METTL3 could be cell type or cell condition dependent and that it may have other functions in addition to its role as a methyltransferase.

FIGURE 1.

Cellular m6A machinery and their roles in mRNA metabolism. In steady-state cells, the methyltransferase complex (“writers”) and demethylases (“erasers”) are localized in the nucleus, which can affect splicing and nuclear export of mRNAs. The nuclear reader YTHDC1 has been implicated in both splicing and nuclear export. In the cytoplasm, YTHDF3 can recruit either YTHDF1 or YTHDF2 to promote translation or degradation of mRNA, respectively. YTHDC2 promotes both translation and degradation of mRNA

To date, 2 m6A “erasers” have been characterized. Fat mass and obesity associated (FTO) and AlkB homolog 5 (ALKBH5) are oxygen-, alpha-ketoglutarate-, and iron-dependent enzymes.40,71 Before its function as an “eraser” was known, a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) in the first intron of FTO was shown to be strongly correlated with obesity.72 Since it does not affect the protein coding sequence of FTO, the mechanism behind FTO's effect on obesity remains unknown.73 Recently, one SNP in the first FTO intron was shown to affect long-range DNA-DNA interactions in the promoter of Iroquois homeobox 3 (IRX3), resulting in the increase of IRX3 expression and an obesity phenotype.74 FTO deficiency in mouse models and humans resulted in growth retardation, malformations, metabolic changes, and abnormal neuronal signaling.75-77 After its role as a demethylase was elucidated, FTO was shown to affect global alternative splicing38 and to play a role in adipogenesis by regulating the alternative splicing of RUNX1 translocation partner 1 (RUNX1T1).78 Recently, it has been reported that FTO prefers demethylation of m6Am over m6A in vivo, leaving ALKBH5 as the sole m6A demethylase.79 Knockdown of ALKBH5 in HeLa cells accelerated mRNA export from the nucleus, and male ALKBH5-deficient mice were infertile due to aberrant spermatogenesis.40,80 In spermatocytes, ALKBH5 is essential for the correct splicing of the 3′UTR of transcripts.80 ALKBH5 also promotes the maintenance of glioblastoma stem-like cells by upregulating forkhead box M1 (FOXM1) expression.81 Another study found that ALKBH5 expression was induced during hypoxia, leading to increased Nanog homeobox (NANOG) expression in breast cancer stem cells.82

Among the “reader” proteins, the YTH N6-methyladenosine RNA-binding protein family YTHDF1, YTHDF2, YTHDF3, YTHDC1, and YTHDC2 have been most well studied. YTHDF1 recruits the translation preinitiation complex to methylated transcripts to enhance translation41; YTHDF2 promotes the degradation of methylated transcripts by shuttling them to the CCR4-NOT complex and DCP1/2 in P bodies45,46; YTHDF3 facilitates translation or degradation of methylated transcripts by binding directly to YTHDF1 or YTHDF283,84; YTHDC1 regulates RNA splicing by competitively recruiting serine-and arginine-rich splicing factor 3 or 10 (SRSF3 or SRSF10) to mRNA and mediates nuclear export by interacting with nuclear RNA export factor 1 (NXF1)39,85; and YTHDC2 affects both translation and degradation of RNA by interacting with the 40-80S subunit and XRN1, respectively.55,86 Recently, 2 independent studies screened for additional “reader” proteins and characterized FMR1 as a sequence context-dependent m6A reader that promotes translation of methylated transcripts.87,88 Interestingly, a class of “antireader” proteins have been discovered where they preferentially bind to GGACU motifs in the absence of m6A.87,88 Two of these proteins, G3BP stress granule assembly factor 1 (G3BP1) and G3BP stress granule assembly factor 2 (G3BP2), are stress granule proteins that stabilize unmethylated transcripts.87,88

To date, numerous studies have revealed a role of m6A in viral replication by modulating the levels of “writers,” “erasers,” and “readers” in cells. As viruses hijack cellular pathways to favor their replication, it is not surprising that these proteins either promote or inhibit viral replication, depending on the virus or infected cell type. Conversely, it is also possible that the host cells use m6A and its associated proteins as an antiviral mechanism to restrict viral replication.

4 |. REGULATION OF REPLICATION OF RNA VIRUSES BY m6A

As intracellular parasites, viruses depend on cellular machinery for replication. Since the “writers” and “erasers” are found in the nucleus of resting cells, it is assumed that only viruses that replicate in the nucleus, eg, HIV, IAV, adenovirus, and HSV-1 can use m6A in their life cycle. Indeed, m6A was not detected on the genomes of RNA viruses that replicate in the cytoplasm such as vesicular stomatitis virus, reovirus, and vaccinia virus in studies done prior to next generation sequencing.89-91 However, a more recent work with hepatitis C virus (HCV) and liver cancer cell lines shows that the methylation machinery and the demethylase FTO are present in the cytoplasm.92

4.1 |. HIV

Three independent groups have characterized the involvement of m6A in HIV replication using CD4+ T cells, 293T cells, and HeLa cells.93-95 All 3 studies showed an enrichment of m6A at the 3′ UTR of HIV-genomic RNA, but two of the studies showed additional m6A sites throughout the viral genome.94,95 This discrepancy could be due to the different mapping techniques used. Kennedy et al used PA-m6A-seq, whereas the other 2 studies used m6A-seq. Cell line or HIV strain could also cause variations even though all 3 studies included CD4+ T cells. Two of these studies demonstrated a proviral role of m6A as knockdown of METTL3/METTL14 decreased viral replication while knockdown of ALKBH5 had the opposite effect.93,94 All 3 YTHDF proteins were shown to bind to HIV RNA and favor HIV replication.93,94 However, the study by Tirumuru et al showed that all 3 YTHDF proteins antagonize HIV replication.95 The reason for this discrepancy is unclear but could be attributed to the use of a genetically modified virus that contains a luciferase reporter in its genome. Lichinchi et al also characterized the function of 2 potential m6A sites within the Rev response element (RRE) of HIV. The presence of m6A on the RRE enhanced binding of Rev to viral RNA, facilitating export of viral RNA. However, m6A mapping done by the 2 other studies failed to identify these m6A sites on the RRE. It is possible that the plastic nature of the HIV genome may contribute to this discrepancy; however, the RRE is a relatively stable region of the HIV genome. If m6A is a positive regulator of HIV replication, it should be evolutionarily conserved in this polymorphic virus.

4.2 |. Flaviviruses

Two independent groups simultaneously published epitranscriptomic maps of m6A on flaviviral genomes and proposed m6A-related mechanisms that regulate the replication of Zika virus (ZIKV) and HCV.92,96 The m6A profiles in the genomes of the positive single-stranded flaviviruses such as HCV, Dengue virus, yellow fever virus, ZIKV, and West Nile virus are conserved.92 Knockdown of METTL3 or METTL14 in host cells enhanced the viral titers of HCV and ZIKV. Knockdown of FTO lowered the viral titers of both viruses, whereas knockdown of ALKBH5 had no effect on HCV viral production but lowered ZIKV viral titers in the supernatants. Since flaviviruses replicate in the cytoplasm, both studies presented evidence that the “writers” and “erasers” can be found in the cytoplasm of the host cells. Despite the different cellular functions of the YTHDF1, YTHDF2, and YTHDF3 “readers,” all of them negatively impact HCV and ZIKV replication. In the context of HCV, Gokhale et al mapped the binding sites of YTHDF1, YTHDF2, and YTHDF3 on the viral genome and showed that these proteins compete with HCV core protein for binding to regions on the Env gene to suppress packaging of viral RNA into new virions. This suppressive effect was hypothesized by Gokhale et al to be advantageous for HCV infection as a slower replication rate reflects chronic infection in the liver. The study by Lichinchi et al revealed 5′UTR hypermethylation of host transcripts after ZIKV infection. In addition, host immune-related transcripts were dynamically modified during ZIKV infection, indicating that m6A is involved in promoting an antiviral response. It is also possible that the virus usurps m6A machinery to suppress the host antiviral response by recruiting “writers” or “erasers” to specific cellular transcripts.96 In contrast to HIV, m6A negatively affects flavivirus replication by affecting viral packaging.

4.3 |. Influenza A virus

A work by Courtney et al showed that inhibition of methylation with 3-deazaadenosine (3DAA) and METTL3 knockout in A549 lung cancer cells decreased the replication of IAV by reducing both viral mRNA and protein levels.97 Contrary to YTHDF2's role in promoting RNA degradation, overexpression of YTHDF2 during IAV infection enhanced levels of viral mRNA, protein, and the release of infectious virions. It is possible that YTHDF2-mediated mRNA degradation decreases host antiviral gene transcripts, thus enhancing viral replication. Overexpression of YTHDF1 and YTHDF3 had no effect on IAV replication and viral production even though all 3 “readers” were found to bind to viral RNA. Using the photoactivatable ribonucleo-side-enhanced cross-linking and immunoprecipitation (PAR-CLIP) and PA-m6A-seq binding data of YTHDF1, YTHDF2, and YTHDF3, Courtney et al found numerous m6A sites on the negative sense vRNA and positive sense mRNA of IAV. They generated 2 mutant viruses by making silent mutations of m6A sites on the positive and negative sense RNAs of the hemagglutinin segment, respectively. However, they could not mutate all the m6A sites as some could introduce nonsynonymous mutations of the hemagglutinin protein. These two mutants had decreased levels of hemagglutinin protein, viral replication in culture, and IAV pathogenicity in a mouse infection model. The mechanism behind the positive effect of METTL3 or YTHDF2 on IAV replication remains unknown. The authors also investigated the possibility that methylation of viral RNAs might prevent the activation of innate immune sensors such as RIG-I or MDA5 but saw no additional activation of interferon-β when cells were infected with their mutant virions that carried fewer m6A sites. It is possible that YTHDF2 binding to viral RNAs sequesters it away from innate RNA immune sensors but no loss of function data was shown.

The function of YTHDC1 and YTHDC2 in the life cycle of RNA viruses has not been investigated so far. Since splicing is critical for HIV replication, it is likely that YTHDC1 could be involved in regulating this process to promote HIV replication, which would agree with the proviral role of m6A in the context of HIV. For flaviviruses, it is unclear if the nuclear “reader” YTHDC1 is present in the cytoplasm, but it is possible since the “writers” and “erasers” are involved in their cytoplasmic replicative cycles.

4.4 |. m6A in the life cycle of Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus

The role of m6A in the life cycles of RNA viruses has predominantly been investigated at the genomic RNA level in positive-stranded RNA viruses except for IAV, where both negative-stranded genomic RNA and positive-stranded mRNA have been investigated. DNA viruses such as Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV), which replicates in the nucleus using the host machinery, is likely to usurp m6A machinery to promote its replication.

KSHV is the etiologic agent of Kaposi sarcoma, primary effusion lymphoma (PEL), multicentric Castleman disease, and KSHV-induced inflammatory cytokine syndrome (KICS).98-101 KSHV latently infects endothelial progenitor cells, B cells, and mesenchymal stem cells.98,102-107 Results of recent studies show that KS might originate from mesenchymal stem cells.103,105,107 During viral latency, a few viral genes and a cluster of miRNAs are expressed,108-112 which are essential for KSHV-induced cellular transformation.105,113,114 Like other herpesviruses, KSHV latently infected cells can be reactivated into a lytic life cycle, expressing viral lytic genes in a cascade manner in the order of immediate early, early, and late genes that culminates in virion production.115-117 Hence, KSHV lytic replication is a complex process regulated by multiple cellular processes, possibly including m6A and its related machinery.

Although most tumor cells are latently infected by KSHV in KS tumors, a small subset of them also undergo spontaneous lytic replication. These cells secrete viral cytokines such as viral interleukin-6 (vIL6) and induce proinflammatory and proangiogenic cytokines such as IL6, basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF), and oncostatin M.118-121 This cytokine milieu promotes the growth of KS cells via an autocrine and paracrine mechanism.118 Another lytic viral protein, KSHV G protein-coupled receptor (vGPCR), promotes the expression of VEGF to stimulate angiogenesis and survival.122,123 Hence, KSHV lytic replication in a small subset of tumor cells is a key contributor to local inflammation and angiogenesis, which are the features of KS tumors. Understanding the alterations of viral and cellular m6A modifications during KSHV latent and lytic infection could provide insights into the mechanism of KSHV-induced tumorigenesis.

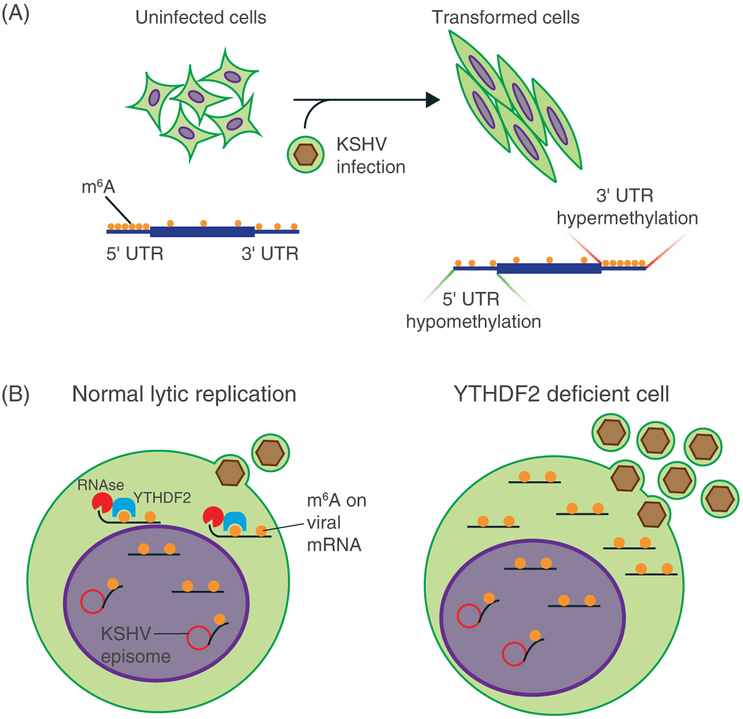

Using m6A-seq, we have mapped the KSHV m6A epitranscriptome during both viral latency in a variety of cell types, including primary cell lines. We have found that during latent infection, m6A is well conserved in KSHV transcripts across 5 cell lines and is predominantly found in the latent locus carrying latency-associated nuclear antigen (LANA), viral Fas-associated death domain (FADD)-like interleukin-1 betaconverting enzyme (FLICE)-inhibitory protein (vFLIP), and viral cyclin (vCyclin). The KSHV lytic epitranscriptome had widespread m6A methylation of viral genes. The lytic epitranscriptome was also well conserved between 2 models of lytic replication, KiSLK and BCBL1-R cells. The “reader” YTHDF2 was shown to suppress viral lytic replication by promoting the degradation of viral transcripts (Figure 2). Taken together, m6A is a novel viral restriction factor in the context of KSHV reactivation. Conflicting evidence was proposed by another study, which demonstrated a proviral role for m6A.124 It was found that knockdown of METTL3 and inhibition of the methyltransferase complex with 3DAA in BCBL1 cells decreased viral lytic replication, whereas knockdown of FTO modestly increased viral lytic replication. This study also presented evidence for a role of YTHDC1 in promoting splicing of KSHV replication transcription activator (RTA, ORF50), an immediate early gene required and sufficient to induce KSHV lytic replication. Using RNA-binding protein immunoprecipitation and quantitative reverse transcription PCR (RIP-RT-qPCR), they showed that four m6A peaks on the RTA transcript are bound by YTHDC1 and mutation of each of these peaks results in decreased RTA splicing. This observation was made by overexpressing the mutant RTA transcripts in 293T cells. In the context of whole virus and by inducing the expression of an exogenous RTA gene with doxycycline, we did not observe an effect on viral lytic replication in YTHDC1-deficient KiSLK cells.

FIGURE 2.

The role of m6A during KSHV-induced cellular transformation and KSHV lytic replication. A, In cells that are latently infected and transformed by KSHV, we observed 5′ UTR hypomethylation and 3′ UTR hypermethylation. B, During viral lytic replication, KSHV mRNAs contain high levels of m6A. The “reader” protein YTHDF2 binds to and promotes the degradation of viral mRNAs. In YTHDF2-deficient cells, we observed an increase in the half-life of viral transcripts and increased production of virions

During lytic replication, we observed 5′UTR hypermethylation and a slight 3′ hypomethylation in KiSLK cells, whereas in BCBL1-R cells, there was 5′UTR hypomethylation and 3′UTR hypermethylation. The differences between these 2 cell lines could be attributed to the stronger activity of KSHV host shutoff, the result of an exonuclease (SOX) in BCBL1-R cells. It is possible that SOX activity is influenced by m6A, but further studies are needed to confirm this hypothesis. In both cell models, hypermethylated and hypomethylated pathways are important for KSHV lytic replication, such as adipogenesis, protein kinase A signaling, ILK signaling, ERK/MAPK signaling, PI3K/AKT signaling, and integrin signaling. Since many of these pathways are known to mediate KSHV lytic replication, m6A might be an additional mechanism regulating KSHV lytic replication via modulating these pathways. We did not observe any significant effect of m6Am on viral lytic replication.

We characterized the effect of KSHV latent infection on the cellular epitranscriptome in 4 pairs of uninfected and latently infected cells. The number of methylated genes and the m6A motifs did not change dramatically after viral latent infection of all 4 types of cells; however, there was 5′UTR hypomethylation and 3′UTR hypermethylation in 3 of the 4 cell lines (Figure 2). The 5’UTR hypomethylated and 3’UTR hypermethylated pathways are involved in oncogenic/mitogenic signaling, epithelial-mesenchymal transition, cytoskeleton and extracellular signaling, endocytosis, loss of contact inhibition, remodeling of adherens junctions, and cellular adhesion/invasion, indicating that m6A might regulate KSHV latency and cellular transformation. These observations are consistent with results of several recent studies showing the involvement of m6A in numerous types of cancer.70,81,125,126 Hence, it can be speculated that KSHV might hijack the m6A machinery to promote viral latency and induce cellular transformation. Overall, our study has provided a valuable epitranscriptomic resource for studying KSHV life cycle and KSHV-induced cellular transformation and tumorigenesis.

5 |. CONCLUSIONS AND PERSPECTIVES

We have only begun to understand how m6A regulates the life cycles of viruses. In large and complex viruses such as KSHV, it is possible that m6A on different viral transcripts mediate different functions, such as degradation, splicing, or translation. Assessing this at the global level as our study has done cannot tease apart these transcript-specific differences. Therefore, ablating methylation at specific sites on important viral transcripts such as LANA and RTA, for example, might provide more specific mechanisms on how m6A might regulate KSHV life cycle in future studies. Generation of point mutations in the context of whole viral genome by using the bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) technology could achieve this goal.127,128 Using the clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR-cas9) technology to mutate viral DNA is possible but difficult because of the high copy number of KSHV episomes per cell.

KSHV encodes an RNA-binding protein, mRNA transcript accumulation protein (MTA or ORF57), which has functions analogous to m6A such as splicing, transcript stability, and translation. MTA-binding sites on PAN RNA, vIL6, and ORF59 have stem-loop structures; the presence of m6A might destabilize stem-loop formation, affecting its accessibility to RNA-binding proteins.129-131 Therefore, it is possible that m6A might act as a repellent to MTA binding. Although this would be in contrast to m6A on HIV RRE, which favors binding of HIV Rev protein to its RNA, it remains possible particularly since m6A has both “reader” and “antireader” proteins.94

Targeting “writers” and “erasers” with small molecule inhibitors is a potential approach for antiviral therapies. Various studies have shown that 3DAA, an methyltransferase inhibitor, can reduce viral replication124,132,133; however, 3DAA also inhibits histone and DNA methylation.58 A more specific inhibitor of the “writers” is required to eliminate off target effects. Similarly, an inhibitor of the “erasers,” meclofenamic acid, could be used to inhibit HCV replication since m6A antagonizes its replication. Both KSHV- and HCV-induced tumors are dependent on a small subset of cells undergoing viral lytic replication. Hence, inhibition of the m6A machinery might have an antitumor effect.

Viruses have coevolved with the host cells. How viruses hijack the m6A machinery remains to be understood. For example, during HCV replication, the “writers” and “erasers” are relocalized to the cytoplasm. These changes can lead to alterations in the host m6A methylome during viral infection or latency as we have shown in the context of KSHV infection. Current literature lacks studies on the functions of m6A in host-pathogen interactions, which could be especially important for oncogenic viruses. The extent of m6A's role in cellular transformation during oncogenic virus infection/latency remains unknown.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was in part supported by grants from NIH (CA096512, CA124332, CA132637, CA177377, CA213275, DE025465, and CA197153) to S.-J. Gao.

Funding information

National Cancer Institute, Grant/Award Numbers: CA096512, CA124332, CA132637, CA177377, CA197153 and CA213275; National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, Grant/Award Number: DE025465; NIH, Grant/Award Numbers: CA197153, DE025465, CA213275, CA177377, CA132637, CA124332 and CA096512

Abbreviations used:

- 3DAA

3-deazaadenosine

- 4SU

4-thiouridine

- 6SG

6-thioguanosine

- ALKBH5

AlkB homolog 5

- BAC

bacterial artificial chromosome

- BCBL1-R

primary effusion lymphoma cell line

- bFGF

basic fibroblast growth factor

- CRISPR-Cas9

clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats

- FOXM1

forkhead box M1

- FTO

fat mass and obesity associated

- G3BP1

G3BP stress granule assembly factor 1

- G3BP2

G3BP stress granule assembly factor 2

- HCV

hepatitis C virus

- HIV

human immunodeficiency virus

- HSV-1

herpes simplex virus type 1

- IAV

influenza A virus

- IRX3

Iroquois homeobox 3

- KIAA1429

Vir-like m6A methyltransferase associated

- KICS

KSHV-induced inflammatory cytokine syndrome

- KiSLK

latently infected renal carcinoma cells

- KSHV

Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus

- LANA

Latency-associated nuclear antigen

- m6A

N6-methyladenosine

- m6A-LAIC-seq

m6A level and isoform characterization sequencing

- m6Am

N6,2′-O-dimethyladenosine

- METTL3

methyltransferase-like 3

- METTL14

methyltransferase-like 14

- miCLIP

individual nucleotide resolution cross-linking and immunoprecipitation

- mRNA

messenger RNA

- MSC

adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells

- MTA

mRNA transcript accumulation

- NANOG

Nanog homeobox

- NXF1

nuclear RNA export factor 1

- PA-m6A-seq

photo-cross-linking-assisted m6A sequencing

- PAR-CLIP

photoactivatable ribonucleoside-enhanced cross-linking and immunoprecipitation

- PEL

primary effusion lymphoma

- RBM15

RNA-binding motif protein 15

- RBM15B

RNA-binding motif protein 15B

- RIP-RT-qPCR

RNA-binding protein immunoprecipitation and quantitative reverse transcription PCR

- RRE

Rev response element

- rRNA

ribosomal RNA

- RSV

Rous sarcoma virus

- RTA

KSHV replication transcription activator

- RUNX1T1

RUNX1 translocation partner 1

- SOX

KSHV host shut off an exonuclease

- SNP

single nucleotide polymorphism

- SRSF3

serine-and arginine-rich splicing factor 3

- SRSF10

serine-and arginine-rich splicing factor 10

- SV40

simian virus 40

- tRNA

transfer RNA

- UTR

untranslated region

- vCyclin

viral cyclin

- vFLIP

KSHV Fas-associated death domain (FADD)-like interleukin-1 beta-converting enzyme (FLICE) inhibitory protein

- vGPCR

KSHV G protein-coupled receptor

- vIL6

viral interleukin-6

- WTAP

Wilms tumor 1-associating protein

- XIST

X inactive specific transcript

- YTHDC1

YTH domain containing 1

- YTHDC2

YTH domain containing 2

- YTHDF1,

YTH N6-methyladenosine RNA-binding protein 1

- YTHDF2

YTH N6-methyladenosine RNA-binding protein 2

- YTHDF3

YTH N6-methyladenosine RNA-binding protein 3

- ZIKV

Zika virus

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no competing interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Boccaletto P, Machnicka MA, Purta E, et al. MODOMICS: a database of RNA modification pathways. 2017 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adams JM, Cory S. Modified nucleosides and bizarre 5′-termini in mouse myeloma mRNA. Nature. 1975;255(5503):28–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Desrosiers R, Friderici K, Rottman F. Identification of methylated nucleosides in messenger RNA from Novikoff hepatoma cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1974;71(10):3971–3975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Desrosiers RC, Friderici KH, Rottman FM. Characterization of Novikoff hepatoma mRNA methylation and heterogeneity in the methylated 5′ terminus. Biochemistry. 1975;14(20):4367–4374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krug RM, Morgan MA, Shatkin AJ. Influenza viral mRNA contains internal N6-methyladenosine and 5′-terminal 7-methylguanosine in cap structures. J Virol. 1976;20(1):45–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sommer S, Salditt-Georgieff M, Bachenheimer S, et al. The methylation of adenovirus-specific nuclear and cytoplasmic RNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1976;3(3):749–765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moss B, Koczot F. Sequence of methylated nucleotides at the 5′- terminus of adenovirus-specific RNA. J Virol. 1976;17(2):385–392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aloni Y, Dhar R, Khoury G. Methylation of nuclear simian virus 40 RNAs. J Virol. 1979;32(1):52–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beemon K, Keith J. Localization of N6-methyladenosine in the Rous sarcoma virus genome. J Mol Biol. 1977;113(1):165–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Canaani D, Kahana C, Lavi S, Groner Y. Identification and mapping of N6-methyladenosine containing sequences in simian virus 40 RNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1979;6(8):2879–2899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dimock K, Stoltzfus CM. Sequence specificity of internal methylation in B77 avian sarcoma virus RNA subunits. Biochemistry. 1977;16(3): 471–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dimock K, Stolzfus CM. Cycloleucine blocks 5′-terminal and internal methylations of avian sarcoma virus genome RNA. Biochemistry. 1978;17(17):3627–3632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Finkel D, Groner Y. Methylations of adenosine residues (m6A) in pre- mRNA are important for formation of late simian virus 40 mRNAs. Virology. 1983;131(2):409–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Furuichi Y, Shatkin AJ, Stavnezer E, Bishop JM. Blocked, methylated 5′-terminal sequence in avian sarcoma virus RNA. Nature. 1975; 257(5527):618–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hashimoto SI, Green M. Multiple methylated cap sequences in adenovirus type 2 early mRNA. J Virol. 1976;20(2):425–435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Horowitz S, Horowitz A, Nilsen TW, Munns TW, Rottman FM. Mapping of N6-methyladenosine residues in bovine prolactin mRNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1984;81(18):5667–5671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.HsuChen CC, Dubin DT. Methylated constituents of Aedes albopictus poly (A)-containing messenger RNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1977; 4(8):2671–2682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kane SE, Beemon K. Precise localization of m6A in Rous sarcoma virus RNA reveals clustering of methylation sites: implications for RNA processing. Mol Cell Biol. 1985;5(9):2298–2306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lavi S, Shatkin AJ. Methylated simian virus 40-specific RNA from nuclei and cytoplasm of infected BSC-1 cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1975; 72(6):2012–2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lavi U, Fernandez-Munoz R, Darnell JE Jr. Content of N-6 methyl adenylic acid in heterogeneous nuclear and messenger RNA of HeLa cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1977;4(1):63–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moss B, Gershowitz A, Stringer JR, Holland LE, Wagner EK. 5′-Terminal and internal methylated nucleosides in herpes simplex virus type 1 mRNA. J Virol. 1977;23(2):234–239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Narayan P, Ayers DF, Rottman FM, Maroney PA, Nilsen TW Unequal distribution of N6-methyladenosine in influenza virus mRNAs. Mol Cell Biol. 1987;7(4):1572–1575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Narayan P, Ludwiczak RL, Goodwin EC, Rottman FM. Context effects on N6-adenosine methylation sites in prolactin mRNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22(3):419–426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stoltzfus CM, Dimock K. Evidence of methylation of B77 avian sarcoma virus genome RNA subunits. J Virol. 1976;18(2):586–595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thomason AR, Brian DA, Velicer LF, Rottman FM. Methylation of high-molecular-weight subunit RNA of feline leukemia virus. J Virol. 1976;20(1):123–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wei CM, Gershowitz A, Moss B. Methylated nucleotides block 5′ terminus of HeLa cell messenger RNA. Cell. 1975;4(4):379–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wei CM, Gershowitz A, Moss B. 5′-Terminal and internal methylated nucleotide sequences in HeLa cell mRNA. Biochemistry. 1976; 15(2):397–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wei CM, Moss B. Nucleotide sequences at the N6-methyladenosine sites of HeLa cell messenger ribonucleic acid. Biochemistry. 1977; 16(8):1672–1676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dominissini D, Moshitch-Moshkovitz S, Schwartz S, et al. Topology of the human and mouse m6A RNA methylomes revealed by m6A-seq. Nature. 2012;485(7397):201–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meyer KD, Saletore Y, Zumbo P, Elemento O, Mason CE, Jaffrey SR. Comprehensive analysis of mRNA methylation reveals enrichment in 3′ UTRs and near stop codons. Cell. 2012;149(7):1635–1646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saletore Y, Meyer K, Korlach J, Vilfan ID, Jaffrey S, Mason CE. The birth of the epitranscriptome: deciphering the function of RNA modifications. Genome Biol. 2012;13(10):175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen K, Lu Z, Wang X, et al. High-resolution N6-methyladenosine (m6A) map using photo-crosslinking-assisted m6A sequencing. Angewandte Chemie. 2015;54(5):1587–1590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Linder B, Grozhik AV, Olarerin-George AO, Meydan C, Mason CE, Jaffrey SR. Single-nucleotide-resolution mapping of m6A and m6Am throughout the transcriptome. Nat Methods. 2015;12(8):767–772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Molinie B, Wang J, Lim KS, et al. m6A-LAIC-seq reveals the census and complexity of the m6A epitranscriptome. Nat Methods. 2016;13(8):692–698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li Y, Wang Y, Zhang Z, Zamudio AV, Zhao JC. Genome-wide detection of high abundance N6-methyladenosine sites by microarray. RNA. 2015;21(8):1511–1518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ke S, Pandya-Jones A, Saito Y, et al. m6A mRNA modifications are deposited in nascent pre-mRNA and are not required for splicing but do specify cytoplasmic turnover. Genes Dev. 2017;31(10):990–1006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Slobodin B, Han R, Calderone V, et al. Transcription impacts the efficiency of mRNA translation via co-transcriptional N6-adenosine methylation. Cell. 2017;169(2):326, e312–337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bartosovic M, Molares HC, Gregorova P, Hrossova D, Kudla G, Vanacova S. N6-methyladenosine demethylase FTO targets pre- mRNAs and regulates alternative splicing and 3′-end processing. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45(19):11356–11370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xiao W, Adhikari S, Dahal U, et al. Nuclear m6A reader YTHDC1 regulates mRNA splicing. Mol Cell. 2016;61(4):507–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zheng G, Dahl JA, Niu Y, et al. ALKBH5 is a mammalian RNA demethylase that impacts RNA metabolism and mouse fertility. Mol Cell. 2013;49(1):18–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang X, Zhao BS, Roundtree IA, et al. N6-methyladenosine modulates messenger RNA translation efficiency. Cell. 2015;161(6):1388–1399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Meyer KD, Patil DP, Zhou J, et al. 5′ UTR m6A promotes cap-independent translation. Cell. 2015;163(4):999–1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Alarcon CR, Lee H, Goodarzi H, Halberg N, Tavazoie SF. N6-methyladenosine marks primary microRNAs for processing. Nature. 2015;519(7544):482–485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen T, Hao YJ, Zhang Y, et al. m6A RNA methylation is regulated by microRNAs and promotes reprogramming to pluripotency. Cell Stem Cell. 2015;16(3):289–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Du H, Zhao Y, He J, et al. YTHDF2 destabilizes m6A-containing RNA through direct recruitment of the CCR4-NOT deadenylase complex. Nat Commun. 2016;7:12626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang X, Lu Z, Gomez A, et al. N6-methyladenosine-dependent regulation of messenger RNA stability. Nature. 2014;505(7481):117–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Xiang Y, Laurent B, Hsu CH, et al. RNA m6A methylation regulates the ultraviolet-induced DNA damage response. Nature. 2017;543(7646):573–576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhou J, Wan J, Gao X, Zhang X, Jaffrey SR, Qian SB. Dynamic m6A mRNA methylation directs translational control of heat shock response. Nature. 2015;526(7574):591–594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Batista PJ, Molinie B, Wang J, et al. m6A RNA modification controls cell fate transition in mammalian embryonic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;15(6):707–719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Geula S, Moshitch-Moshkovitz S, Dominissini D, et al. Stem cells. m6A mRNA methylation facilitates resolution of naive pluripotency toward differentiation. Science. 2015;347(6225):1002–1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang Y, Li Y, Toth JI, Petroski MD, Zhang Z, Zhao JC. N6- methyladenosine modification destabilizes developmental regulators in embryonic stem cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2014;16(2):191–198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yoon KJ, Ringeling FR, Vissers C, et al. Temporal control of mammalian cortical neurogenesis by m6A methylation. Cell. 2017;171(4):877, e817–889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Qi ST, Ma JY, Wang ZB, Guo L, Hou Y, Sun QY. N6-methyladenosine sequencing highlights the involvement of mRNA methylation in oocyte meiotic maturation and embryo development by regulating translation in Xenopus laevis. J Biol Chem. 2016;291(44):23020–23026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ivanova I, Much C, Di Giacomo M, et al. The RNA m6A reader YTHDF2 is essential for the post-transcriptional regulation of the maternal transcriptome and oocyte competence. Molecular cell. 2017;67(6):1059, e1054–1067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hsu PJ, Zhu Y, Ma H, et al. Ythdc2 is an N6-methyladenosine binding protein that regulates mammalian spermatogenesis. Cell Res. 2017;27(9):1115–1127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Xu K, Yang Y, Feng GH, et al. Mettl3-mediated m6A regulates sper- matogonial differentiation and meiosis initiation. Cell Res. 2017;27(9):1100–1114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schwartz S, Agarwala SD, Mumbach MR, et al. High-resolution mapping reveals a conserved, widespread, dynamic mRNA methylation program in yeast meiosis. Cell. 2013;155(6):1409–1421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fustin JM, Doi M, Yamaguchi Y, et al. RNA-methylation-dependent RNA processing controls the speed of the circadian clock. Cell. 2013;155(4):793–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Li Y, Wang X, Li C, Hu S, Yu J, Song S. Transcriptome-wide N6- methyladenosine profiling of rice callus and leaf reveals the presence of tissue-specific competitors involved in selective mRNA modification. RNA Biol. 2014;11(9):1180–1188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Luo GZ, MacQueen A, Zheng G, et al. Unique features of the m6A methylome in Arabidopsis thaliana. Nat Commun. 2014;5:5630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shen L, Liang Z, Gu X, et al. N6-methyladenosine RNA modification regulates shoot stem cell fate in Arabidopsis. Dev Cell. 2016;38(2):186–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bokar JA, Rath-Shambaugh ME, Ludwiczak R, Narayan P, Rottman F. Characterization and partial purification of mRNA N6-adenosine methyltransferase from HeLa cell nuclei. Internal mRNA methylation requires a multisubunit complex. J Biol Chem. 1994;269(26):17697–17704. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bokar JA, Shambaugh ME, Polayes D, Matera AG, Rottman FM. Purification and cDNA cloning of the AdoMet-binding subunit of the human mRNA (N6-adenosine)-methyltransferase. RNA. 1997;3(11):1233–1247. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Liu J, Yue Y, Han D, et al. A METTL3-METTL14 complex mediates mammalian nuclear RNA N6-adenosine methylation. Nat Chem Biol. 2014;10(2):93–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Patil DP, Chen CK, Pickering BF, et al. m6A RNA methylation Promotes XIST-mediated transcriptional repression. Nature. 2016;537(7620):369–373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ping XL, Sun BF, Wang L, et al. Mammalian WTAP is a regulatory subunit of the RNA N6-methyladenosine methyltransferase. Cell Res. 2014;24(2):177–189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Schwartz S, Mumbach MR, Jovanovic M, et al. Perturbation of m6A writers reveals two distinct classes of mRNA methylation at internal and 5′ sites. Cell Rep. 2014;8(1):284–296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wang P, Doxtader KA, Nam Y. Structural basis for cooperative function of Mettl3 and Mettl14 methyltransferases. Mol Cell. 2016;63(2):306–317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wang X, Feng J, Xue Y, et al. Structural basis of N6-adenosine methylation by the METTL3-METTL14 complex. Nature. 2016;534(7608):575–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lin S, Choe J, Du P, Triboulet R, Gregory RI. The m6A methyltransferase METTL3 promotes translation in human cancer cells. Mol Cell. 2016;62(3):335–345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Jia G, Fu Y, Zhao X, et al. N6-methyladenosine in nuclear RNA is a major substrate of the obesity-associated FTO. Nat Chem Biol. 2011;7(12):885–887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lindgren CM, Heid IM, Randall JC, et al. Genome-wide association scan meta-analysis identifies three loci influencing adiposity and fat distribution. PLoS Genet. 2009;5(6):e1000508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Loos RJ, Yeo GS. The bigger picture of FTO: the first GWAS-identi- fied obesity gene. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2014;10(1):51–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Smemo S, Tena JJ, Kim KH, et al. Obesity-associated variants within FTO form long-range functional connections with IRX3. Nature. 2014;507(7492):371–375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hess ME, Hess S, Meyer KD, et al. The fat mass and obesity associated gene (Fto) regulates activity of the dopaminergic midbrain circuitry. Nat Neurosci. 2013;16(8):1042–1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Fischer J, Koch L, Emmerling C, et al. Inactivation of the Fto gene protects from obesity. Nature. 2009;458(7240):894–898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Boissel S, Reish O, Proulx K, et al. Loss-of-function mutation in the dioxygenase-encoding FTO gene causes severe growth retardation and multiple malformations. Am J Hum Genet. 2009;85(1):106–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zhao X, Yang Y, Sun BF, et al. FTO-dependent demethylation of N6- methyladenosine regulates mRNA splicing and is required for adipo- genesis. Cell Res. 2014;24(12):1403–1419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Mauer J, Luo X, Blanjoie A, et al. Reversible methylation of m6Am in the 5′ cap controls mRNA stability. Nature. 2017;541(7637):371–375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Tang C, Klukovich R, Peng H, et al. ALKBH5-dependent m6A demethylation controls splicing and stability of long 3′-UTR mRNAs in male germ cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Zhang S, Zhao BS, Zhou A, et al. m6A demethylase ALKBH5 maintains tumorigenicity of glioblastoma stem-like cells by sustaining FOXM1 expression and cell proliferation program. Cancer cell. 2017;31(4):591, e596–606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Zhang C, Samanta D, Lu H, et al. Hypoxia induces the breast cancer stem cell phenotype by HIF-dependent and ALKBH5-mediated m6A-demethylation of NANOG mRNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113(14):E2047–E2056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Li A, Chen YS, Ping XL, et al. Cytoplasmic m6A reader YTHDF3 promotes mRNA translation. Cell Res. 2017;27(3):444–447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Shi H, Wang X, Lu Z, et al. YTHDF3 facilitates translation and decay of N6-methyladenosine-modified RNA. Cell Res. 2017;27(3):315–328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Roundtree IA, Luo GZ, Zhang Z, et al. YTHDC1 mediates nuclear export of N6-methyladenosine methylated mRNAs. Elife. 2017;6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Wojtas MN, Pandey RR, Mendel M, Homolka D, Sachidanandam R, Pillai RS. Regulation of m6A transcripts by the 3′-->5′ RNA helicase YTHDC2 is essential for a successful meiotic program in the mammalian germline. Mol Cell. 2017;68(2):374–387. e312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Edupuganti RR, Geiger S, Lindeboom RGH, et al. N6-methyladenosine (m6A) recruits and repels proteins to regulate mRNA homeostasis. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2017;24(10):870–878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Arguello AE, DeLiberto AN, Kleiner RE. RNA chemical proteomics reveals the N6-methyladenosine (m6A)-regulated protein-RNA inter- actome. J Am Chem Soc. 2017;139(48):17249–17252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Abraham G, Rhodes DP, Banerjee AK. The 5′ terminal structure of the methylated mRNA synthesized in vitro by vesicular stomatitis virus. Cell. 1975;5(1):51–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Furuichi Y, Morgan M, Muthukrishnan S, Shatkin AJ. Reovirus messenger RNA contains a methylated, blocked 5′-terminal structure: m-7G(5′)ppp(5′)G-MpCp. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1975; 72(1):362–366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Wei CM, Moss B. Methylated nucleotides block 5′-terminus of vaccinia virus messenger RNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1975; 72(1):318–322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Gokhale NS, McIntyre ABR, McFadden MJ, et al. N6-methyladenosine in flaviviridae viral RNA genomes regulates infection. Cell Host Microbe. 2016;20(5):654–665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kennedy EM, Bogerd HP, Kornepati AV, et al. Posttranscriptional m6A editing of HIV-1 mRNAs enhances viral gene expression. Cell Host Microbe. 2016;19(5):675–685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Lichinchi G, Gao S, Saletore Y, et al. Dynamics of the human and viral m6A RNA methylomes during HIV-1 infection of T cells. Nature Microbiology. 2016;1(4):16011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Tirumuru N, Zhao BS, Lu W, Lu Z, He C, Wu L. N6-methyladenosine of HIV-1 RNA regulates viral infection and HIV-1 Gag protein expression. Elife. 2016;5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Lichinchi G, Zhao BS, Wu Y, et al. Dynamics of human and viral RNA methylation during Zika virus infection. Cell Host Microbe. 2016;20(5):666–673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Courtney DG, Kennedy EM, Dumm RE, et al. Epitranscriptomic enhancement of influenza A virus gene expression and replication. Cell Host Microbe. 2017;22(3):377–386. e375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Cesarman E, Chang Y, Moore PS, Said JW, Knowles DM. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-like DNA sequences in AIDS-related body-cavity-based lymphomas. N Engl J Med. 1995;332(18):1186–1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Chang Y, Cesarman E, Pessin MS, et al. Identification of herpesviruslike DNA sequences in AIDS-associated Kaposi's sarcoma. Science. 1994;266(5192):1865–1869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Soulier J, Grollet L, Oksenhendler E, et al. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-like DNA sequences in multicentric Castleman’s disease. Blood. 1995;86(4):1276–1280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Uldrick TS, Wang V, O’Mahony D, et al. An interleukin-6-related systemic inflammatory syndrome in patients co-infected with Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus and HIV but without multicentric Castleman disease. Clin Infect Diseases : Off Publ Infect Diseases Soc America. 2010;51(3):350–358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Carroll PA, Brazeau E, Lagunoff M. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus infection of blood endothelial cells induces lymphatic differentiation. Virology. 2004;328(1):7–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Li Y, Zhong C, Liu D, et al. Evidence for Kaposi's sarcoma originating from mesenchymal stem cell through KSHV-induced mesenchymal- to-endothelial transition. Cancer Res. 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Hong YK, Foreman K, Shin JW, et al. Lymphatic reprogramming of blood vascular endothelium by Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. Nat Genet. 2004;36(7):683–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Jones T, Ye F, Bedolla R, et al. Direct and efficient cellular transformation of primary rat mesenchymal precursor cells by KSHV. J Clin Invest. 2012;122(3):1076–1081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Wang HW, Trotter MW, Lagos D, et al. Kaposi sarcoma herpesvirus- induced cellular reprogramming contributes to the lymphatic endothelial gene expression in Kaposi sarcoma. Nat Genet. 2004;36(7):687–693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Lee MS, Yuan H, Jeon H, et al. Human mesenchymal stem cells of diverse origins support persistent infection with Kaposi's sarcoma- associated herpesvirus and manifest distinct angiogenic, invasive, and transforming phenotypes. MBio. 2016;7(1):e02109–02115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Cai X, Lu S, Zhang Z, Gonzalez CM, Damania B, Cullen BR. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus expresses an array of viral microRNAs in latently infected cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005; 102(15):5570–5575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Pfeffer S, Sewer A, Lagos-Quintana M, et al. Identification of microRNAs of the herpesvirus family. Nat Methods. 2005; 2(4):269–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Sarid R, Flore O, Bohenzky RA, Chang Y, Moore PS. Transcription mapping of the Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (human herpesvirus 8) genome in a body cavity-based lymphoma cell line (BC-1). J Virol. 1998;72(2):1005–1012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Staskus KA, Zhong W, Gebhard K, et al. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus gene expression in endothelial (spindle) tumor cells. J Virol. 1997;71(1):715–719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Zhong W, Wang H, Herndier B, Ganem D. Restricted expression of Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (human herpesvirus 8) genes in Kaposi sarcoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93(13):6641–6646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Moody R, Zhu Y, Huang Y, et al. KSHV microRNAs mediate cellular transformation and tumorigenesis by redundantly targeting cell growth and survival pathways. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9(12):e1003857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Zhu Y, Ramos da Silva S, He M, et al. An oncogenic virus promotes cell survival and cellular transformation by suppressing glycolysis. PLoS Pathog. 2016;12(5):e1005648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Jenner RG, Alba MM, Boshoff C, Kellam P. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus latent and lytic gene expression as revealed by DNA arrays. J Virol. 2001;75(2):891–902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Renne R, Zhong W, Herndier B, et al. Lytic growth of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (human herpesvirus 8) in culture. Nat Med. 1996;2(3):342–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Sun R, Lin SF, Staskus K, et al. Kinetics of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus gene expression. J Virol. 1999;73(3):2232–2242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Ensoli B, Sturzl M. Kaposi's sarcoma: a result of the interplay among inflammatory cytokines, angiogenic factors and viral agents. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 1998;9(1):63–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Grundhoff A, Ganem D. Inefficient establishment of KSHV latency suggests an additional role for continued lytic replication in Kaposi sarcoma pathogenesis. J Clin Invest. 2004;113(1):124–136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Liu C, Okruzhnov Y, Li H, Nicholas J. Human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8)- encoded cytokines induce expression of and autocrine signaling by vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in HHV-8-infected primary-effusion lymphoma cell lines and mediate VEGF-independent antiapoptotic effects. J Virol. 2001;75(22):10933–10940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Miles SA, Martinez-Maza O, Rezai A, et al. Oncostatin M as a potent mitogen for AIDS-Kaposi's sarcoma-derived cells. Science. 1992;255(5050):1432–1434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Bais C, Santomasso B, Coso O, et al. G-protein-coupled receptor of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus is a viral oncogene and angiogenesis activator. Nature. 1998;391(6662):86–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Masood R, Cai J, Zheng T, Smith DL, Naidu Y, Gill PS. Vascular endothelial growth factor/vascular permeability factor is an autocrine growth factor for AIDS-Kaposi sarcoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94(3):979–984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Ye F, Chen ER, Nilsen TW. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus utilizes and manipulates RNA N6-adenosine methylation to promote lytic replication. J Virol. 2017;91(16):e00466–e00417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Li Z, Weng H, Su R, et al. FTO plays an oncogenic role in acute myeloid leukemia as a N6-methyladenosine RNA demethylase. Cancer Cell. 2017;31(1):127–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Ma JZ, Yang F, Zhou CC, et al. METTL14 suppresses the metastatic potential of hepatocellular carcinoma by modulating N6- methyladenosine-dependent primary microRNA processing. Hepatology. 2017;65(2):529–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Brulois KF, Chang H, Lee AS, et al. Construction and manipulation of a new Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus bacterial artificial chromosome clone. J Virol. 2012;86(18):9708–9720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Zhou FC, Zhang YJ, Deng JH, et al. Efficient infection by a recombinant Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus cloned in a bacterial artificial chromosome: application for genetic analysis. J Virol. 2002;76(12):6185–6196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Massimelli MJ, Majerciak V, Kang JG, Liewehr DJ, Steinberg SM, Zheng ZM. Multiple regions of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus ORF59 RNA are required for its expression mediated by viral ORF57 and cellular RBM15. Virus. 2015;7(2):496–510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Sei E, Conrad NK. Delineation of a core RNA element required for Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus ORF57 binding and activity. Virology. 2011;419(2):107–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Liu N, Dai Q, Zheng G, He C, Parisien M, Pan T. N(6)-methyladenosine-dependent RNA structural switches regulate RNA-protein interactions. Nature 2015; 518(7540): 560–564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Bader JP, Brown NR, Chiang PK, Cantoni GL. 3-Deazaadenosine, an inhibitor of adenosylhomocysteine hydrolase, inhibits reproduction of Rous sarcoma virus and transformation of chick embryo cells. Virology. 1978;89(2):494–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Stoltzfus CM, Montgomery JA. Selective inhibition of avian sarcoma virus protein synthesis in 3-deazaadenosine-treated infected chicken embryo fibroblasts. J Virol. 1981;38(1):173–183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]