Abstract

Background

We analyzed late fatal infections (LFI) in allogeneic stem cell transplant (HCT) recipients reported to the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research.

Methods

We analyzed the incidence, infection types and risk factors contributing to LFI in 10336 adult and 5088 pediatric subjects surviving ≥2 years after first HCT without relapse.

Results

Among 2245 adult and 377 pediatric subjects who died, infections were a primary or contributory cause of death in 687(31%) and 110(29%) subjects, respectively. At 12 years post-HCT cumulative incidence of LFIs was 6.4 % (95% confidence interval[CI]:5.8-7.0%) in adults as compared with 1.8% (95%CI:1.4-2.3%) in pediatric subjects, p<0.001. In adults, the two most significant risks for developing LFI were increasing age (20-39, 40-54 and ≥ 55 vs 18-19 years) with hazard ratio (HR) of 3.12 (95%CI:1.33-7.32), 3.86 (95%CI:1.66-8.95) and 5.49 (95%CI:2.32-12.99) and a history of chronic GVHD (cGVHD) with ongoing immunosuppression 2 years post-HCT as compared to no history of GVHD with HR 3.87 (95%CI:2.59-5.78), respectively. In pediatric subjects, the three most significant risks for developing LFI were a history of cGVHD with (HR 9.49, 95%CI:4.39-20.51) or without (HR 2.7,95%CI:1.05-7.43) ongoing immunosuppression 2 years post-HCT as compared to no history of GVHD, diagnosis of inherited abnormalities of erythrocyte function as compared to diagnosis of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) (HR 2.30, 95%CI:1.19-4.42) and age >10 years (HR 1.92, 95%CI:1.15-3.2).

Conclusion

This study emphasizes the importance of continued vigilance for late infections after HCT and support strategies aimed to decrease the risk of cGVHD.

Keywords: Hemopoietic cell transplant, infection, late fatal infection, adults, pediatrics

Introduction:

Late fatal infections (LFI) occurring ≥ 2 years after HCT still remain a significant contributing factor to mortality post-HCT[1]. However, there are limited data regarding the incidence of LFI, the types of infections responsible for death and recipient, disease, and HCT related risk factors associated with LFI in adult and pediatric patients surviving ≥ 2 years after HCT. Previous studies addressing LFI after HCT were limited by small sample size, response bias, inadequate follow-up and incomplete data reporting from transplant centers. In order to address this knowledge gap we performed a detailed analysis of LFI in HCT recipients reported to the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research (CIBMTR) including the incidence, types of infections and risk factors.

Methods:

Data source

CIBMTR includes a network of more than 450 transplant centers worldwide that contribute data on consecutive transplants performed at each center to a centralized registry. All patients are followed longitudinally until lost to follow-up or death. The quality of the data reported by all participating centers is monitored by computerized error checks, physician data review, and periodic on-site patient record audits.

Study design

The study population consisted of subjects with hematologic malignancies and nonmalignant conditions who underwent HCT between January 1, 1995 and December 31, 2011. To minimize selective reporting bias, patients were only selected from centers whose team follow-up completeness index was greater than or equal to 80% at 4 years (n=344 centers and 43,345 patients). Completeness index is defined as the ratio of total observed person-time to the potential person-time of follow-up[2]. Subjects who received stem cells from syngeneic donors or multiple donors (n=583) were excluded. About 57% (n=24,420) of patients were then excluded for death or relapse within 24 months of HCT. Subjects missing baseline, 100 day, or disease-specific forms (n=193) and without available consent (n=638) were excluded. Subjects with severe combined immunodeficiency, and other immune system disorders associated with incomplete immune reconstitution after HCT (n=1,017) were excluded from the analysis. Subjects with non-myeloma plasma cell disorders (n=7) were also excluded due to low numbers. Prior autologous HCT (n=759) was permitted for study inclusion. Subjects who were lost to follow-up (n=549) and subjects with missing survival data (n= 19) or cause of death data (n=495) were excluded from analysis. A total of 15,424 patients were included in the final study population, with 10,336 adult and 5,088 pediatric patients.

Statistical Analysis

Pediatric patients 0 to 17 years of age and adult patients aged 18 to 79 were analyzed separately because of differences in disease biology, pre-transplantation treatment, graft sources, conditioning regimens, overall post-transplant mortality and causes of post-transplant mortality. Relapse or second HCT > 2 years after initial HCT was reported in 1,263 adult (12%) and 297 (6%) pediatric subjects and these subjects were censored at the event. In multivariate analysis of pediatric population the one multiple myeloma patient under the age of 18 and 64 patients missing GVHD data were excluded.

Potential risk factors for late deaths from infections included age at HCT, sex, race, geographical region of the center, Karnofsky or Lansky performance score at HCT, disease, prior autologous HCT, CIBMTR disease risk index, time from diagnosis to HCT, human immunodeficiency virus (HI status, donor type, HLA match, stem-cell source, donor-recipient CMV status, conditioning regimen, dose of total-body irradiation (TBI), GVHD prophylaxis regimen, use of T-cell depletion, year of HCT, presence of fungal infections prior to HCT, and development of acute and chronic GVHD within the first 2 years after HCT. The effect of these covariates on mortality due to infection was analyzed by marginal Cox regression models which allow to adjust for clustering within center.

All potential risk factors were checked with time-dependent covariates to ensure that assumptions of proportionality were met. Backward elimination procedures were used to identify significant variables to include in the final model. Interactions between donor source and GVHD status at 2 years, as well as conditioning and GVHD status at 2 years were evaluated in the regression models for adult population. Similar assessment was not possible for the pediatric population due to low number of events in this cohort. A significance level of alpha = 0.05 was used. SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) was used for the analyses.

Results

Patient characteristics:

The final study population included 10,336 adult patients from 267 transplant centers and 5,088 pediatric patients from 202 centers. Patient, disease and transplant characteristics are shown in Table 1. The median age at transplant was 44 (range 18-79) years in adult patients and 9 (range <1-17) years in the pediatric cohort. The median follow-up intervals were 97 months (range, 24-251 months) and 100 months (range, 24-247 months) for adult and pediatric subjects, respectively.

Table 1.

Characteristics of study population - HCT recipients disease-free at least 24 months after transplant

| Population |

||

|---|---|---|

| Variable | Adult (≥ 18 age)Variable | Pediatric (< 18 age) |

| Number of patients, n | 10,336 | 5,088 |

| Number of centers, n | 267 | 202 |

| Median patient age at transplant (range), years | 44 (18-79) | 9 (<1-17) |

| Sex, n (%) | ||

| Male | 5888 (57) | 2898 (57) |

| Female | 4448 (43) | 2190 (43) |

| Performance score, n (%) | ||

| ≥90 | 7124 (69) | 4148 (82) |

| ≥90 | 2689 (26) | 750 (15) |

| Missing | <523 (5) | 190 (4) |

| Disease, n (%) | ||

| AML | 4134 (40) | 1162 (23) |

| ALL | 1363 (13) | 1607 (32) |

| Other leukemia | 574 (6) | 98 (2) |

| MDS | 865 (8) | 182 (4) |

| Other myeloproliferative neoplasms | 701 (7) | 252 (5) |

| Non- Hodgkin’s lymphoma | 1335 (13) | 94 (2) |

| Hodgkin’s lymphoma | 173 (2) | 13 (<1) |

| Multiple myeloma | 237 (2) | 1 (<1) |

| Severe aplastic anemia | 821 (8) | 826 (16) |

| Inherited abnormalities of erythrocyte diff/function | 133 (1) | 853 (17) |

| Median time from diagnosis to transplant, months (range) | 9 (<1-540) | 10 (<1-210) |

| Conditioning regimen, n (%) | ||

| Myeloablative | 6,807 (66) | 4,064 (80) |

| Reduced intensity/non-myeloablative | 3,339 (32) | 977 (19) |

| Missing | 190 (2) | 47 (1) |

| Graft source, n (%) | ||

| Bone marrow | 3,479 (34) | 3,395 (67) |

| Peripheral blood | 6,347 (61) | 553 (11) |

| Cord blood | 510 (5) | 1,140 (22) |

| Donor type, n (%) | ||

| HLA-identical sibling | 4,509 (44) | 2,003 (39) |

| Other relative | 290 (3) | 249 (5) |

| HLA-matched unrelated donor | 3,774 (37) | 1,042 (21) |

| HLA-mismatched unrelated donor | 984 (10) | 422 (8) |

| Unrelated donor missing HLA data | 269 (3) | 232 (5) |

| Cord Blood | 510 (5) | 1,140 (22) |

| History of acute GVHD (at 2 years of HCT), n (%) | ||

| No | 6668 (65) | 3509 (69) |

| Yes | 3559 (34) | 1522 (30) |

| Missing | 109 (1) | 57 (1) |

| Composite history of GVHD (before 2 year starting point) | ||

| No GVHD, n (%) | 3054 (30) | 2755 (54) |

| Acute only | 932 (9) | 696 (14) |

| Chronic GVHD, on immunosuppression at 2 years | 3325 (32) | 563 (11) |

| Chronic GVHD, off immunosuppression at 2 years | 1415 (14) | 566 (11) |

| Chronic GVHD, unknown immunosuppression status at 2 years | 1506 (15) | 444 (9) |

| Missing all GVHD data | 104 (1) | <64 (1) |

| Median follow-up of survivors (range), months | 97 (24-251) | 100 (24-247) |

Pre-transplant infections, graft sources and GVHD:

In 10,336 adult subjects, clinically significant fungal infections prior to HCT were reported in 884 (9%) subjects and 318 (3%) subjects were reported to be HIV seropositive. Graft sources included bone marrow (BM) in 3,479 (34%), granulocyte-colony stimulating factor mobilized peripheral blood stem cells (PBSC) in 6,347 (61%) and cord blood (CB) in 510 (5%) subjects respectively. Myeloablative and reduced intensity/non-myeloablative conditioning was used to 6,807 (66%) and 3,339 (32%) patients, respectively. A history of acute GVHD (aGVHD), limited, or extensive chronic GVHD (cGVHD) by 2 years of HCT was reported in 3,559 (34%), 1,315 (13%) and 4,912 (48%) subjects respectively.

In 5088 evaluable pediatric subjects, clinically significant fungal infections prior to HCT were reported in 418 (8%) patients and 75 (1.5%) patients were HIV seropositive. BM, granulocyte-colony stimulating factor mobilized PBSC and CB were reported as graft sources in 3,395 (67%), 553 (11%) and 1,140 (22%) subjects respectively. Myeloablative and reduced intensity/non-myeloablative conditioning was used to 4,064 (80%) and 997 (19%) pediatric patients, respectively. A history of acute GVHD (aGVHD), limited or extensive cGVHD within 2 years of HCT was reported in 1522 (30%), 109 (2%) and 858 (17%) patients respectively.

LFI in the context with other causes of death:

In the study population, 2245 (22%) adult subjects died from a variety of causes and 839 (37%) of deaths occurred in patients who had a post-HCT relapse or a second transplant (these patients were censored at that date). Of the remaining 1406 deaths, the leading primary causes of death were cGVHD (n=340, 24%), organ failure (n=335, 24%), and infection (n=311, 22%). Infection was reported as a contributing cause of death in 185 (13%) subjects. In the study population, 377 (7%) pediatric subjects died from a variety of causes, 151 (40%) of deaths occurred in patients who had a post-HCT relapse or a second transplant (these patients were censored at that date). Of the remaining 226 deaths, the leading causes of death were organ failure (n=48, 21%), subsequent malignancy (n=44, 19%), and GVHD (n=43, 19%). Infection was reported as a primary cause of death in 41 (18%) of deaths and contributory cause of death in 27 (12%).

Types of infections ≥ 2 years after HCT:

Types of infection as the cause of death in both adult and pediatric subjects are shown in Table 2. Bacterial infections were the most common primary or contributing causes of LFI after HCT for both adults and pediatric subjects. A substantial proportion of subjects in both adult and pediatric groups had unspecified infections or infections without a definitive reported pathogen.

Table 2.

Types of LFI in HCT recipients disease-free at least 24 months after transplant

| Adult | Pediatric | |

|---|---|---|

| Number of patients that died from infection* |

496 | 68 |

| Infection listed as the primary cause of death, n (%) | 311 | 41 |

| Bacterial | 108 (35) | 13 (32) |

| Viral | 29 (9) | 0 |

| Fungal | 35 (11) | 7 (17) |

| Protozoal | 1 (<1) | 0 |

| Unspecified | 116 (37) | 20 (49) |

| Multiple types reported | 22 (7) | 1 (2) |

| Infection listed as contributing cause of death, n (%) | 185 | 27 |

| Bacterial | 85 (46) | 10 (37) |

| Viral | 29 (16) | 5 (18) |

| Fungal | 20 (11) | 4 (15) |

| Protozoal | 0 | 0 |

| Unspecified | 49 (26) | 8 (30) |

| Multiple types reported | 2(1) | 0 |

Patients with relapse or second HCT occurring ≥ 2 years after HCT were censored at the event and excluded from this analysis

The risk of LFI ≥ 2 years after HCT:

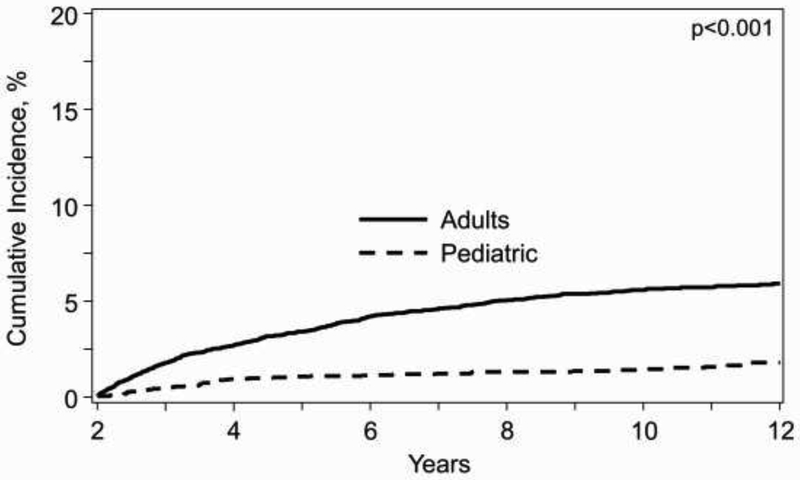

There was a continuous increase in the risk of LFI over time beyond 2 years after HCT. As shown in Figure 1, there was a progressive rise in cumulative incidence of LFI in adults after 2 years, rising from 1.8% at 3 years (95% confidence interval [CI] 1.5-2.0%), to 5.3% (95%CI 4.9-5.8%) at 8 years and 6.4% (95%CI 5.8-7.0%) at 12 years. In contrast, in children there was a significantly smaller increase of LFI over time, being 0.4% (95%CI 0.3-0.6%) at 3 years, 1.3% (95%CI 1.0-1.7%) at 8 years and 1.8% (95%CI 1.4-2.3%) at 12 years (p<0.001).

Figure 1.

Cumulative incidence of death from infection after 2 years of survival in adult and pediatric patients*

*Death from other cause considered competing risk and patients censored at relapse or second transplant

Risk factors for infectious death:

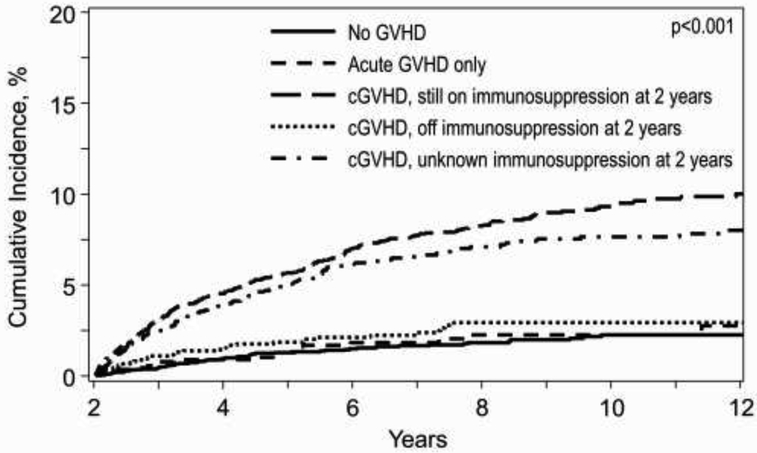

In adult subjects, age ≥20 years, receipt of MUD or MMUD HCT, and male sex were independently associated with an increased risk of LFI in multivariate analysis (Table 3). Older age cohorts were associated with incrementally higher LFI rates (Table 3). Subjects with a history of cGVHD with ongoing immunosuppression at 2 years post HCT had a significantly increased risk of LFI (HR=3.87; p<.0001) and higher cumulative incidence of LFI (p<.0001) as compared to subjects without any reported GVHD (Table 3 and Fig 2a). In contrast, there was no statistically significant increased risk of LFI in subjects with aGVHD (HR=1.09; p=0.7310) nor history of cGVHD without ongoing immunosuppression by 2 years post-HCT (HR=1.25; p=0.3610) (Table 3). Other factors, such as primary disease, Karnofsky performance score, race and ethnicity, disease diagnosis, prior autologous HCT, pre-existing fungal infections, HIV seropositivity, CIBMTR disease risk index, time from diagnosis to HCT, conditioning regimen intensity, use of TBI, graft source, use of ATG or alemtuzumab prior to HCT, donor/recipient CMV serostatus, geographical region and year of HCT, were not significantly associated with an increased risk for LFI.

Table 3.

Multivariate analysis of factors associated with late fatal infections in the adult population N=10,336)

| Variable | N | HR (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| 18-19 | 498 | 1.00 | <.0001* |

| 20-39 | 3849 | 3.12 (1.33, 7.32) | 0.0089 |

| 40-54 | 3730 | 3.86 (1.66, 8.95) | 0.0017 |

| 55+ | 2259 | 5.49 (2.32, 12.99) | 0.0001 |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 5888 | 1.00 | 0.0168 |

| Female | 4448 | 0.79 (0.65, 0.96) | |

| Donor | |||

| Matched sibling | 4509 | 1.00 | <.0001* |

| Other relative | 290 | 1.04 (0.56, 1.92) | 0.9067 |

| Matched unrelated | 3774 | 1.65 (1.34, 2.05) | <.0001 |

| Mismatched unrelated | 984 | 1.88 (1.35, 2.62) | 0.0002 |

| Unrelated, match unknown | 269 | 1.60 (0.99, 2.59) | 0.0563 |

| Cord blood | 510 | 0.80 (0.37, 1.74) | 0.5778 |

| History of GVHD within 2 years of HCT | |||

| None | 3052 | 1.00 | <.0001* |

| Acute GVHD only | 932 | 1.09 (0.67, 1.76) | 0.7310 |

| Chronic GVHD, immunosuppression at 2 years | 3325 | 3.87 (2.59, 5.78) | <.0001 |

| Chronic GVHD, off immunosuppression by 2 years | 1415 | 1.25 (0.77, 2.02) | 0.3610 |

| Chronic GVHD, unknown immunosuppression at 2 years | 1506 | 4.14 (2.82, 6.09) | <.0001 |

| Missing | 106 | 4.90 (2.61, 9.17) | <.0001 |

Overall p-value.

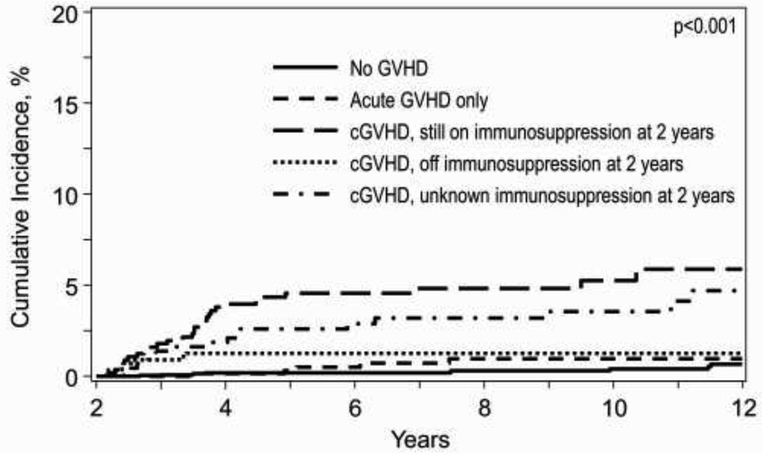

Figure 2.

a. Cumulative incidence of LFI in adults based on history of GVHD*

b. Cumulative incidence of LFI in pediatric based on history of GVHD*

*Death from other cause considered competing risk and patients censored at relapse or second transplant

In pediatric subjects, age ≥10 years, receipt of MUD or MMUD HCT, and inherited abnormalities of erythrocyte function (AEF) were independently associated with an increased risk of LFI (Table 4). In contrast, severe aplastic anemia (SAA) was associated with a decreased LFI risk in multivariate analysis. Compared to patients without any reported GVHD, a history of cGVHD with ongoing immunosuppression at 2 years of HCT (HR=9.49, p<0.0001) and a history of cGVHD without ongoing immunosuppression by 2 years of HCT (HR=2.79; p=.0395), but not history of aGVHD (HR=2.07; p=0.16), were significantly associated with a significantly increased risk of LFI (Table 4) and higher cumulative incidence of LFI (p<0.001) (Fig 2b). Karnofsky/Lansky performance score, race and ethnicity, sex, prior autologous HCT, pre-existing fungal infections, HIV seropositivity, CIBMTR disease risk index, time from diagnosis to HCT, conditioning regimen intensity, graft source, use of TBI, ATG or alemtuzumab prior to HCT, donor/recipient CMV serostatus, geographical region and year of HCT were factors that did not increase the risk of LFI.

Table 4.

Multivariate analysis of factors associated with late fatal infections in in pediatric population (N=5,053)

| Variable | N | HR (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| 0-9 | 2885 | 1.00 | 0.0122 |

| 10-17 | 2138 | 1.92 (1.15, 3.2) | |

| Donor | |||

| Matched sibling | 1980 | 1.00 | 0.0216* |

| Other relative | 246 | 1.24 (0.41, 3.73) | 0.6986 |

| Matched unrelated | 1025 | 1.98 (1.02, 3.86) | 0.0440 |

| Mismatched unrelated | 418 | 3.51 (1.73, 7.08) | 0.0005 |

| Unrelated, match unknown | 231 | 1.60 (0.57, 4.46) | 0.3711 |

| Cord blood | 1123 | 1.38 (0.70, 2.75) | 0.3554 |

| History of GVHD within 2 years of HCT | |||

| None | 2755 | 1.00 | <.0001* |

| Acute GVHD only | 696 | 2.07 (0.75, 5.72) | 0.1600 |

| Chronic GVHD, immunosuppression. at 2 years | 562 | 9.49 (4.39, 20.51) | <.0001 |

| Chronic GVHD, off immunosuppression by 2 years | 566 | 2.79 (1.05, 7.43) | 0.0395 |

| Chronic GVHD, unknown immunosuppression at 2 years | 444 | 9.68 (4.38, 20.51) | <.0001 |

| Disease | |||

| AML | 1146 | 1.00 | 0.0027* |

| ALL | 1588 | 0.85 (0.47,1.52) | 0.5719 |

| Other Leukemia MDS | 96 | 1.56 (0.38, 6.46) | 0.5428 |

| Other myeloproliferative neoplasms | 179 | 0.62 (0.14, 2.71) | 0.5222 |

| Lymphoma | 247 | 0.88 (0.30, 2.55) | 0.8064 |

| SAA | 104 | 1.11 (0.24, 5.02) | 0.8965 |

| AEF | 817 | 0.22 (0.05, 0.94) | 0.0409 |

| 846 | 2.30 (1.19, 4.42) | 0.0129 |

Overall p-value.

Identified pathogens causing death:

There were 195 adults, who had identified pathogens listed as a primary cause of death, including bacterial infections in 108 (55%), viral infections in 29 (16%), fungal infections in 35 (18%) and multiple infections in 22 (11%) subjects. Among these infections vaccine preventable infections were in 13 (7%) subjects (S. pneumoniae, influenza, hepatitis B) and drug preventable were in 1 (0.5%) subject (Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia). In the pediatric cohort, pathogens as a primary cause of death were identified in 21 subjects, which included bacterial infections in 13 (62%), fungal infections in 7 (33%) and multiple infections in 1 (5%) subjects. Among these infections vaccine preventable infections were listed in 2 (10%) subjects (S. pneumoniae) and drug preventable were in 3 (15%) subjects (Candida species, Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia).

Discussion:

In this study, we performed an analysis of LFI on the largest group of HCT survivors with long-term follow-up reported to date. Because disease relapse and relapse-directed interventions significantly increase risk of severe infections, we censored patients with relapse or second HCT occurring after 2 years after initial HCT to analyze the impact of other less known factors on LFI in long term survivors. This is the first analysis where LFI were evaluated separately in adult and pediatric subjects and where the impact of both GVHD and immunosuppression of LFI was estimated.

While the cumulative incidence of LFI was low in HCT recipients, it contributed to one third of all deaths occurring at least 2 years after HCT in both pediatric and adult subjects. Older age, HCT from unrelated donors, male gender, and history of cGVHD with ongoing immunosuppression at 2 years were associated with an increased risk of LFI in adult patients. This is the first comprehensive analysis of LFI in a large cohort of pediatric patients. Despite differences in primary diseases, intensity of conditioning regimens, graft sources, the lower incidence and severity of cGVHD and a lower late mortality rate as compared to adult patients, LFI in pediatric patients, similarly to adult patients, contributed to a third of all deaths ≥ 2 years post HCT. Age ≥10 years, history of cGVHD either with or without ongoing immunosuppression at 2 years of HCT and AEF were associated with an increased risk of LFI in pediatric subjects. A significantly reduced risk of LFI in pediatric patients with SAA requires further studies, it could be speculated that patients with SAA predominantly receive bone marrow transplants from sibling donors, which is associated with lower risk of cGVHD as compared to other donor sources [3]. In our study pediatric patients with SAA had significantly lower incidence of cGVHD at 2 years post-HCT as compared with AML patients (22% vs 34%, p<0.0001)

Several previous studies demonstrate that long lasting impairment of the immune system can lead to increased risk of late infections after HCT [4-6], Increasing age at HCT is associated with impaired recovery of the CD4+ T cells following HCT leading to an increased risk of opportunistic infections[7] and decreased response to vaccination[8]. One of the first published analyses of late infection after HCT included 89 patients with aplastic anemia (AA) and acute leukemia who survived ≥ 6 months after allogeneic or syngeneic HCT[9]. In that study conducted decades ago, bacterial infections of respiratory tract, skin and bacteremia represented more than half of all reported infections and 9% of the patients died from infectious complications. Chronic GVHD was the only variable significantly associated with increased risk for late infections[9]. The incidence and risk factors of late infections were retrospectively evaluated in a larger study, which included 196 recipients with AA, CML, and AML who received HCT from matched related donors with a median follow-up of 8 years [10]. Late severe bacterial infections were the most frequent infections with an 8-year cumulative incidence of 15% and development of extensive chronic GVHD were found to be risk factors for development of these infections[10]. A large single center retrospective study focused on long-term survival of 389 HCT recipients surviving disease free at one year after HCT found that late infections, chronic GVHD and relapsed disease were the top 3 causes of mortality beyond first year of HCT[11]. Patients with cGVHD requiring immunosuppression at 1-year after HCT had significantly higher mortality as compared to patients who were not on immunosuppression, however, the role of infections in patients who died from cGVHD is not reported in this study[11]. Even in long-term survivors, who have survived ≥ 5 years after HCT, life expectancy continues to be lower than expected due to increased non-relapse mortality, including infections, which were the third most common cause of mortality and constituted 12% of all deaths [12]. In a large single center study, which included 429 HCT recipients who received myeloablative conditioning and who were alive and free of their original disease for≥ 2-year post HCT, 16% patients developed recurrent respiratory tract infections, 1% had recurrent urinary tract infections and only one patient developed pulmonary aspergillosis [13]. The largest reported study to date focusing on late complications of HCT included 10,632 patients who were alive and disease free at 2 years after receiving myeloablative conditioning (MAC) HCT for AML, ALL, MDS and lymphoma [1]. In that study late deaths remained higher than expected for each disease when compared with age, sex, and nationality-matched general population. Deaths as a result of infection, which included only those infections that occurred without active GVHD or ongoing GVHD therapy varied from 4% to 17% of all deaths depending on disease diagnosis at transplant and length of post-transplant follow-up. In our study, the risk of LFI was not increased in cord blood recipients compared to sibling donor recipients but was in unrelated donor transplants. We hypothesize that the increased risk of LFI in unrelated donor transplants, but not in cord blood transplants in both pediatric and adult recipients, is associated with increased incidence and or severity of cGVHD in these patients

In our study an increased risk of LFI in long-term survivors after HCT was associated with older age and history of cGVHD, which adversely impact immune reconstitution for many years after HCT. Despite the introduction of novel antimicrobial therapies to the clinic and the development of supportive care guidelines, the year of HCT had no significant impact on the risk of LFI in our study. Therefore, stronger emphasis on post HCT vaccinations, avoidance of infectious exposures, and increased awareness of primary providers of the possibility of LFI and infection control should be advocated in long-term survivors after HCT. HCT survivors themselves should be educated about increased risk of LFI and instructed to promptly alert healthcare provides if they develop symptoms suggestive of LFI. We showed that pediatric patients with inherited AEF had an increased risk of LFI. In our study 21% of these patients had sickle cell disease (SCD). Previously Gluckman et al. reported similar observation of increased fatal infections in patients with SCD post-HCT[14]. Although data on prior splenectomy or functional hyposplenism was not available for these patients, an increased risk of LFI suggests increased importance of prolonged antimicrobial prophylaxis and vaccination in this group of patients. Vaccine and drug preventable LFI were low in our study, which may suggest that majority of transplant centers included in our study were following protocols for post-HCT vaccinations and antimicrobial prophylaxis.

Our study has several limitations. Despite our strong emphasis on completeness of data reporting some important information was not available for analysis. Although the study was adjusted for center effect, several data elements related to center practices such as vaccination schedules, use of antimicrobials for prophylaxis and therapy on LFI were not collected and were not evaluated in our study. While most reports contained the category of infection (bacterial, viral, fungal), the majority of specific causative pathogens were not captured in the reporting forms. Rates of preventable infections are underestimated in the current analysis due to large number of unspecified infections for both adult and pediatric subjects. Detailed information is lacking on activity of cGVHD and therapy with systemic immunosuppression at the time of development of LFI.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that in both adult and pediatric HCT recipients surviving 2-years post-HCT late fatal infection (LFI) contributed to one third of all deaths. This emphasizes the importance of continued long-term monitoring for infections, and the education of primary health care teams to decrease risk of LFI in long- term HCT recipients. Future studies should examine data on immune reconstitution, immunoglobulin levels, vaccinations and post-vaccination titers.

Highlights.

In both adult and pediatric HCT recipients surviving 2-years post-HCT late fatal infection (LFI) contributed to one third of all deaths

In adults, age ≥20 years, receipt of matched or mismatched unrelated donor (MUD or MMUD) HCT, and male sex were associated with an increased risk of LFI

In pediatric subjects, age ≥10 years, receipt of MUD or MMUD HCT, and inherited abnormalities of erythrocyte function (AEF) were associated with an increased risk of LFI

Acknowledgements:

The CIBMTR is supported primarily by Public Health Service Grant/Cooperative Agreement 5U24CA076518 from the National Cancer Institute (NCI), the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID); a Grant/Cooperative Agreement 4U10HL069294 from NHLBI and NCI; a contract HHSH250201200016C with Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA/DHHS); two Grants N00014-17-1-2388 and N0014-17-1-2850 from the Office of Naval Research; and grants from *Actinium Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; * Amgen, Inc.; *Amneal Biosciences; *Angiocrine Bioscience, Inc.; Anonymous donation to the Medical College of Wisconsin; Astellas Pharma US; Atara Biotherapeutics, Inc.; Be the Match Foundation; *bluebird bio, Inc.; *Bristol Myers Squibb Oncology; *Celgene Corporation; Cerus Corporation; *Chimerix, Inc.; Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center; Gamida Cell Ltd.; Gilead Sciences, Inc.; HistoGenetics, Inc.; Immucor; *Incyte Corporation; Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC; *Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Juno Therapeutics; Karyopharm Therapeutics, Inc.; Kite Pharma, Inc.; Medac, GmbH; MedImmune; The Medical College of Wisconsin; *Mediware; *Merck & Co, Inc.; *Mesoblast; MesoScale Diagnostics, Inc.; Millennium, the Takeda Oncology Co.; *Miltenyi Biotec, Inc.; National Marrow Donor Program; *Neovii Biotech NA, Inc.; Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co, Ltd. – Japan; PCORI; *Pfizer, Inc; *Pharmacyclics, LLC; PIRCHE AG; *Sanofi Genzyme; *Seattle Genetics; Shire; Spectrum Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; St. Baldrick’s Foundation; *Sunesis Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Swedish Orphan Biovitrum, Inc.; Takeda Oncology; Telomere Diagnostics, Inc.; and University of Minnesota. The views expressed in this article do not reflect the official policy or position of the National Institute of Health, the Department of the Navy, the Department of Defense, Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) or any other agency of the U.S. Government.

Footnotes

Corporate member

Disclosure of Conflicts of Interest: Authors disclosed no relevant conflict of interest

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Wingard JR, Majhail NS, Brazauskas R, et al. Long-term survival and late deaths after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. J Clin Oncol 2011;29(16):2230–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clark TG, Altman DG, De Stavola BL. Quantification of the completeness of follow-up. Lancet 2002;359(9314):1309–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yagasaki H, Takahashi Y, Hama A, et al. Comparison of matched-sibling donor BMT and unrelated donor BMT in children and adolescent with acquired severe aplastic anemia. Bone Marrow Transplant 2010;45(10):1508–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Antin JH. Immune reconstitution: the major barrier to successful stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2005;11(2 Suppl 2):43–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Storek J, Dawson MA, Storer B, et al. Immune reconstitution after allogeneic marrow transplantation compared with blood stem cell transplantation. Blood 2001;97(11):3380–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Storek J, Joseph A, Espino G, et al. Immunity of patients surviving 20 to 30 years after allogeneic or syngeneic bone marrow transplantation. Blood 2001;98(13):3505–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Small TN, Papadopoulos EB, Boulad F, et al. Comparison of immune reconstitution after unrelated and related T-cell-depleted bone marrow transplantation: effect of patient age and donor leukocyte infusions. Blood 1999;93(2):467–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roux E, Dumont-Girard F, Starobinski M, et al. Recovery of immune reactivity after T-cell-depleted bone marrow transplantation depends on thymic activity. Blood 2000;96(6):2299–303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Atkinson K, Storb R, Prentice RL, et al. Analysis of late infections in 89 long-term survivors of bone marrow transplantation. Blood 1979;53(4):720–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Robin M, Porcher R, De Castro Araujo R, et al. Risk factors for late infections after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation from a matched related donor. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2007;13(11):1304–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Solh MM, Bashey A, Solomon SR, et al. Long term survival among patients who are disease free at 1-year post allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation: a single center analysis of 389 consecutive patients. Bone Marrow Transplant 2018; 10.1038/s41409-017-0076-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martin PJ, Counts GW Jr., Appelbaum FR, et al. Life expectancy in patients surviving more than 5 years after hematopoietic cell transplantation. J Clin Oncol 2010;28(6):1011–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abou-Mourad YR, Lau BC, Barnett MJ, et al. Long-term outcome after allo-SCT: close follow-up on a large cohort treated with myeloablative regimens. Bone Marrow Transplant 2010;45(2):295–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gluckman E, Cappelli B, Bernaudin F, et al. Sickle cell disease: an international survey of results of HLA-identical sibling hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood 2017;129(11):1548–1556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]