Abstract

Purpose:

To describe the process and preliminary qualitative development of a new symptom-based patient-reported outcome measure (PROM) intended to assess hemodialysis treatment-related physical symptoms.

Methods:

Experienced interviewers conducted concept elicitation and cognitive debriefing interviews with individuals receiving in-center hemodialysis in the United States. Concept elicitation interviews involved eliciting spontaneous reports of symptom experiences and probing to further explore and confirm concepts. We used patient-reported concepts to generate a preliminary symptom PROM. We conducted 3 rounds of cognitive debriefing interviews to evaluate symptom relevance, item interpretability, and draft item structure. We iteratively refined the measure based on cognitive interview findings.

Results:

Forty-two adults receiving in-center hemodialysis participated in the concept elicitation interviews. A total of 12 symptoms were reported by >10% of interviewees. We developed a 13-item initial draft instrument for testing in 3 rounds of cognitive interviews with an additional 52 hemodialysis patients. Participant responses and feedback during cognitive interviews led to changes in symptom descriptions, division of the single item “nausea/vomiting” into 2 distinct items, removal of daily activity interference items, addition of instructions, and clarification about the recall period, among other changes.

Conclusions:

Symptom Monitoring on Renal Replacement Therapy-Hemodialysis (SMaRRT-HD™) is a 14-item PROM intended for use in hemodialysis patents. SMaRRT-HD™ uses a single treatment recall period and a 5-point Likert scale to assess symptom severity. Qualitative interview data provide evidence of its content validity. SMaRRT-HD™ is undergoing additional testing to assess measurement properties and inform measure scoring.

Keywords: symptoms, hemodialysis, content validity, concept elicitation, cognitive debriefing interview, end-stage kidney disease, patient-reported outcome measure

INTRODUCTION

Over 400,000 individuals in the United States (U.S.) receive in-center maintenance hemodialysis for kidney failure.[1] These individuals have health outcomes and quality of life on par with patients with advanced cancer.[2] High symptom burdens contribute to poor health-related quality of life in the dialysis population.[2, 3] Patients receiving dialysis experience, on average, 11 symptoms, including fatigue, nausea, and cramping.[2, 4] Recent studies have found that patients receiving hemodialysis desire greater interaction with their health care providers about symptoms.[5, 6] Patients, along with other dialysis stakeholders, have identified symptom relief as a top priority and called for increased symptom focus in both research and clinical practice.[7, 8]

Despite the importance of symptoms to patients, patients often under-report symptoms,[6] and providers often under-detect them.[9] Routinely collecting standardized patient-reported symptoms would obviate the need for spontaneous reporting by patients and promote dialogue about symptoms with care teams. Among patients with advanced cancer, formalized symptom reporting has been found to improve communication and reduce healthcare utilization and mortality.[10] In addition to symptoms from kidney failure, the dialysis treatment itself likely contributes to patient symptoms. Tailored hemodialysis prescriptions may mitigate symptoms associated with fluid removal, dialysate electrolyte composition, and administered medications. However, lack of frequent, standardized symptom assessments limit investigation of associations between symptoms and treatment characteristics as well as symptom responsiveness to therapeutic interventions. In most U.S. dialysis clinics, systematic symptom data are captured using the Kidney Disease Quality of Life (KDQOL™) symptom subscale, a scale that evaluates symptoms over a 4-week period.[11] This recall period precludes the linkage of symptom reports to specific dialysis treatments. A patient-reported outcome measure (PROM) capturing symptoms with a shorter recall period would facilitate investigation of individualized approaches to symptom management.

To fill this measurement gap and unmet need, we sought to: 1) develop a relevant, content valid, dialysis-related symptom PROM, and 2) collect evidence that patients receiving outpatient hemodialysis can understand and validly use the PROM. We conducted the study in accordance with PROM development best practices,[12–14] performing both concept elicitation and cognitive debriefing interviews with patients receiving in-center hemodialysis.

METHODS

Overview

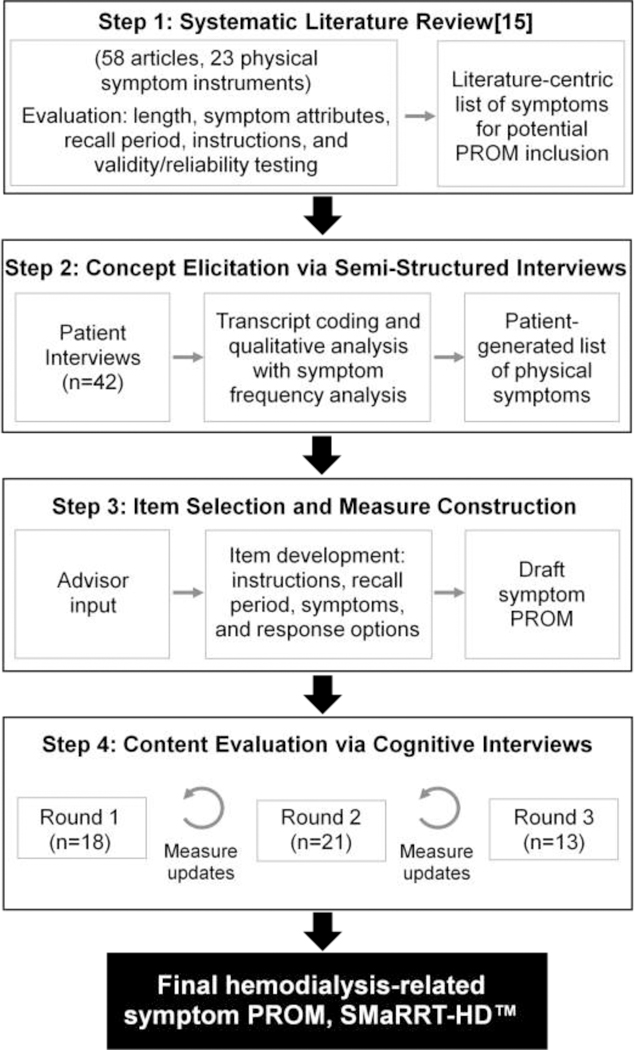

We followed a 4-step process in developing the hemodialysis symptom PROM: (1) literature review (previously reported[15]); (2) concept elicitation interviews; (3) item selection and draft measure construction; and (4) 3 rounds of cognitive debriefing interviews with intervening measure updates (Figure 1). Advisors, including nephrologists, psychometricians, and patients, provided input during the measure development process.

Figure 1.

Overall methodology schematic. PROM, patient-reported outcome measure; SMaRRT-HD™, Symptom Monitoring on Renal Replacement Therapy-Hemodialysis.

This study was approved by the University of North Carolina (NC) at Chapel Hill and University of Virginia (VA) Institutional Review Boards (studies 17–0038, 17–1252, and 19928). All participants provided informed consent. All study procedures were performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional review boards and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments.

Concept Elicitation Interviews

Participants

We recruited participants from 5 dialysis clinics located in NC and VA and national patient mailing lists. Individuals were eligible to participate if they were at least 18 years old, had received in-center hemodialysis for at least 6 months, and were English-speaking. We used purposeful sampling to capture individuals of varying ages, racial backgrounds, and length of time on hemodialysis. This approach promoted capture of diverse experiences and information-rich cases.[16, 17] Recruitment methods in NC and VA clinics included study informational signs and in-person recruitment by study personnel. We used informational emails to members of the Renal Support Network and End-Stage Renal Disease Network Patient Advisory Committees for Networks 2, 3, 14, 16, 17, and 18 to recruit individuals residing outside the Southeastern U.S.. All participants received $25 remuneration.

Interview Purpose and Procedures

We designed concept elicitation interviews to elicit treatment-related physical symptoms experienced by individuals receiving hemodialysis and inform PROM item selection. Additionally, we sought to characterize participant information technology usage and willingness to answer questions about symptoms by different modalities (e.g., paper, smartphone, and e-tablet). We developed a semi-structured interview guide based on literature review and team discussions. Two experienced interviewers (AD, JHN) conducted the interviews from February to October 2017. We stopped the interviews when no new treatment-related symptoms emerged after 3 consecutive interviews (data saturation).

Each participant self-reported demographic information and completed the eHealth Literacy Scale (eHEALS), a validated measure of eHealth literacy among individuals with chronic disease.[18] This 8-item questionnaire captures combined knowledge, comfort, and perceived skills at finding, evaluating, and applying electronic health information to health problems.[19, 20] Higher scores represent higher self-perceived eHealth literacy.

Item Selection and Instrument Construction

The study team then developed a draft symptom PROM during an item generation meeting which was subsequently finalized upon consensus with advisors. Literature review and concept elicitation interview findings informed wording, symptom selection, recall period, and response items for the draft PROM.

Cognitive Debriefing Interviews

After draft measure development, we performed 3 cognitive debriefing interview rounds to assess PROM comprehensibility, relevance, and completeness. Results from each round informed subsequent measure modifications.

Participants

We recruited cognitive debriefing interview participants from 4 dialysis clinics located in NC, Texas (TX), and Oregon (OR). Selection criteria were the same as those for concept elicitation interviews. We used purposeful sampling to capture individuals of varying ages, racial backgrounds, education levels, dialysis vintages, and symptom experiences.[16, 17] Recruitment methods included study informational signs, a recruitment letter, and in-person recruitment by study personnel. All participants received $20 remuneration. In accordance with expert recommendations, the target sample size was at least 10 participants per round.[13] We stopped recruitment for each round upon reaching data saturation.

Interview Goals and Procedures

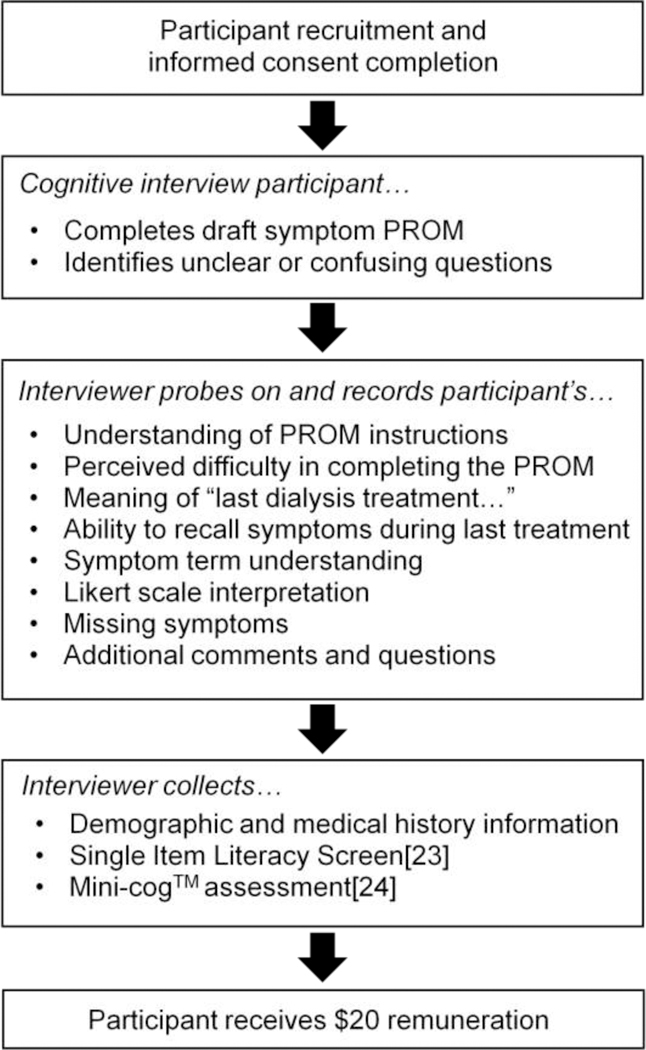

In-person cognitive debriefing interviews assessed participant understanding of the draft PROM questions and ability to provide valid responses reflecting their own symptom experiences. We performed 3 interview rounds with measure updates after each. We obtained feedback on symptoms, item wording, response options, recall period, and instructions through semi-structured interviews. Figure 2 provides an overview of interview flow and content. Experienced interviewers (AD,JHN) conducted the interviews using the think-aloud technique, a process in which participants verbalize their thoughts as they complete a task.[21] Participants completed the symptom PROM, marking items they found difficult to understand, and then the interviewer probed responses to further evaluate understanding.[22]

Figure 2.

Flow of cognitive debriefing interviews. PROM, patient-reported outcome measure.

Each participant self-reported demographic information. In interview rounds 2 and 3, participants answered the Single Item Literacy Screener (SILS) question and completed the Mini-Cog™. The SILS is a single item question intended to identify individuals who may need help with printed health-related materials. We categorized individuals with scores >2 as having limited reading ability.[23] The Mini-Cog™ is a 3-minute instrument to screen for cognitive impairment in older adults. It consists of a 3-item recall test for memory and a clock-drawing test for signs of neurological problems. We categorized individuals with scores <3 as having cognitive impairment.[24]

Analytic Approach

We audio-recorded and professionally transcribed each concept elicitation interview and entered the transcripts into ATLAS.ti software (Version 7, Berlin, Germany). We generated symptom saturation grids that included whether the participant reported the symptom spontaneously or by interviewer probe. We analyzed all data using summary statistics.

During cognitive debriefing interviews, interviewers took detailed notes on standardized interview templates to facilitate full data capture. Interviewers entered notes, demographics, SILS, and Mini-Cog data into the Research Electronic Data Capture database (REDCap). We organized interview data by PROM question to evaluate question performance. We also examined field notes to understand sources of participants’ uncertainty. When evaluating comprehension, we gave more weight to items or sections where 3 or more participants expressed difficulty. We created overall summaries in table format. The study team collectively reviewed summaries and notes to confirm accurate data summation.

RESULTS

Participant Characteristics

We conducted concept elicitation interviews with 42 outpatient hemodialysis patients (60 approached, 11 declined, and 7 could not be scheduled). The average age of participants was 57 ± 13 years, 23 (55%) were female, and 23 (55%) were Black. Concept elicitation interview participants hailed from 9 U.S. states. Among the 41 interviewees completing the eHEALS, scores ranged from 8 to 40 with a mean score of 29 ± 9, suggesting, on average, modest comfort with finding, evaluating, and applying electronic health information to health problems. Four (10%) scored <15, suggesting poor eHealth literacy.

We conducted cognitive debriefing interviews with 52 outpatient hemodialysis patients from NC, TX, and OR (128 approached, 59 declined, 16 could not be scheduled, and 1 missed the scheduled interview). Cognitive interview participants were unique from concept elicitation interview participants. The average age of participants was 58 ± 12 years, 23 (44%) were female, 29 (56%) were Black, and 21 (40%) had education beyond high school. Of the 34 participants completing the SILS and Mini-Cog™, 8 (24%) displayed limited reading ability and 3 (9%) displayed cognitive impairment. Table 1 displays interview participant characteristics.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics.a

| Characteristic | Concept elicitation interview participants (n=42) |

Cognitive interview participants (n=52) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 57.3 ± 12.8; 58.5 [51.0, 67.3] |

58.5 ± 12.5; 61 [50.5, 69.5] |

| Female | 23 (54.8) | 23 (44.2) |

| Race | ||

| White | 15 (35.7) | 12 (23.1) |

| Black | 23 (54.8) | 29 (55.8) |

| Other | 4 (9.5) | 11 (21.2) |

| Hispanic ethnicity | --- | 9 (17.3) |

| Education | ||

| <High school | --- | 16 (30.8) |

| High school graduate | --- | 15 (28.8) |

| Some college | --- | 9 (17.3) |

| College graduate or more | --- | 12 (23.1) |

| Limited reading abilityb | --- | 8 (23.5) (n=34) |

| Cognitive impairment c | --- | 3 (9.1) (n=34) |

| eHEALS score | 28.5 ± 9.1; 32 [21.5–33]; (8,40) (n=41) |

--- |

| Diabetes | 17 (40.5) | |

| Heart failure | 14 (33.3) | |

| Hemodialysis vintage (years) | 7.2 ± 6.9; 4.5 [3.4, 9.0] |

8 ± 7.1; 6 [3.0, 10.0] |

| Location of dialysis clinic | ||

| North Carolina | 16 (38.1) | 18 (34.6) |

| Virginia | 15 (35.7) | --- |

| Connecticut | 3 (7.1) | --- |

| New York | 1 (2.4) | --- |

| New Jersey | 2 (4.8) | --- |

| Delaware | 1 (2.4) | --- |

| Texas | 1 (2.4) | 21 (40.4) |

| California | 2 (4.8) | --- |

| Oregon | --- | 13 (25.0) |

| Washington | 1 (2.4) | --- |

| In-person interview | 31 (73.8) | 52 (100.0) |

| Interview length (minutes) | 29.5 ± 12.0; 27.3 [20.1, 38.0] |

33.2 ± 11.1; 31 25.5, 37.0] |

All characteristics were self-reported. Values reported as n (%) or mean ± standard deviation; median [interquartile range].

Limited reading ability was defined by a SILS score >2.[23]

Cognitive impairment was defined as a Mini-Cog™ score <3.[24]

Abbreviations: SILS, Single Item Literacy Screener; eHEALS, eHealth Literacy Scale.

Symptom Item Selection

Literature review

We previously published the complete results of the systematic literature review.[15] The review yielded 23 PROMs containing 3 or more physical symptoms. Thirteen of the 23 PROMs were developed in patients receiving dialysis. Ten of the PROMs had been administered to dialysis patients but were developed in non-dialysis patients. The symptoms most commonly included in the PROMs were fatigue (81% of measures), cough or shortness of breath (71% of measures), poor appetite (67% of measures), and nausea and/or vomiting (67% of measures). Most measures considered a recall period of 2 to 4 weeks. Bother and severity were the most commonly assessed symptom attributes.[15]

Concept elicitation interviews: symptoms and symptom attributes

Of the 42 concept elicitation interview participants, 41 (98%) spontaneously reported at least one hemodialysis-related physical symptom. Table 2 provides representative quotations from interviewees. Table 3 displays the most commonly reported symptoms. The most common physical symptoms reported spontaneously (i.e., without interviewer probe) were cramping (50%), feeling fatigued after treatment (48%), lightheadedness (29%), restless legs (19%), and nausea (19%). The most common symptoms reported spontaneously or upon interviewer probe were cramping (69%), feeling fatigued after treatment (52%), lightheadedness (50%), thirst (43%), nausea (41%), and tingling (41%). Other symptoms meeting the threshold for inclusion were headache (31%), itching (26%), restless legs (24%), shortness of breath (21%), vomiting (19%), chest pain (19%), and heart palpitations (14%). Diarrhea (9%), swelling (7%), and confusion (5%) did not meet the inclusion threshold.

Table 2.

Patient descriptions of hemodialysis-related symptoms.

| Symptom | Quotationsa |

|---|---|

| Cramping | “If you get cramps, oh my gosh, it’s like a huge Charley horse, you know, and you can’t get up and move. It’s just the worst pain, the worst pain…how do you say this nicely? They’re God awful, you know.” “[Cramps] feel like ripping my tendons apart, it’s like it is breaking my ankle.” “[Cramps] feel like an exorcism of my toes.” |

| Nausea or upset stomach | “It’s like something’s caught in my throat, and it’s just, -- it’ll pass after a while, but I got to get rid of it.” “I need to get something up even though I haven’t had anything to eat.” |

| Vomiting or throwing up | “When my food all come back up.” “Losing your cookies.” |

| Dizziness or lightheadedness | “[Lightheadedness] feels like you’re drunk with no control. It’s not good.” “[Lightheadedness] feels like you’ve bumped your head into the wall, and it takes a couple minutes to get your bearings again.” |

| Racing heart or heart palpitations | “…heart beats outside my shirt.” “…heart thumping or skipping.” |

| Shortness of breath | “…like I’m breathing, and I can’t catch it. Give me oxygen to help and I’ll get OK.” “You just want to get a deep breath, and you can’t, and you’re frustrated. It frustrates you, and you just sit there, and kind of talk to yourself, and kind of calm down. It will be OK once you actually get that deep breath in.” |

| Thirst or dry mouth | “…like you’ve been in the desert.” “…an absolute need to drink.” |

| Headache | “They’re very painful, and they move around. Sometimes on the front of the head, sometimes on the side. It seems to always start during dialysis…toward the end. When you have one of those boogers, you don’t feel like doing anything.” “Someone’s pushing on your head. Sometimes front, sometimes back.” |

| Itching | “Oh my God, itching. It itches to a point where it feels like it’s deep in your skin, and you can’t get to it.” “…like always having wisps of hair in your face” “It’s painful…I scratch till I bleed.” |

|

Restless legs or difficulty keeping legs still |

“I got to get up and move around. My legs want to move, and I can’t keep them still. You get little twinges, and you just have to keep stretching and moving.” “You want to calm down your legs all the way down to the bone.” |

|

Tingling or feelings of pins and needles |

“Like some insects or creepy crawlies in your body.” “My fingers get numb.” |

| Post-dialysis fatigue | “Usually I can walk into dialysis fine, but when I leave I have to have a walker because it’s just too much to carry my bag. It wipes me out.” “Tiredness is a big part of [dialysis] for all of us, I think. [Dialysis] just zaps your energy level. You just don’t have hardly any energy.” |

Table 3.

Most frequently reported hemodialysis-related symptoms during concept elicitation interviews (N=42).a

| Symptoms | Spontaneous report | Spontaneous or probed report |

|---|---|---|

| Cramping | 21 (50.0) | 29 (69.0) |

| Feeling washed out | 20 (47.6) | 22 (52.4) |

| Lightheadedness | 12 (28.6) | 21 (50.0) |

| Restless legs | 8 (19.0) | 10 (23.8) |

| Nausea | 8 (19.0) | 17 (40.5) |

| Vomiting | 5 (11.9) | 8 (19.0) |

| Headache | 5 (11.9) | 13 (31.0) |

| Tingling | 7 (16.7) | 17 (40.5) |

| Thirst | 2 (4.8) | 18 (42.9) |

| Shortness of breath | 2 (4.8) | 9 (21.4) |

| Chest pain | 2 (4.8) | 8 (19.0) |

| Heart palpitations | 1 (2.4) | 6 (14.3) |

| Itching | 1 (2.4) | 11 (26.2) |

Values reported as n (%). Most frequently reported symptoms means those symptoms reported spontaneously or by probe in >10% of interviews.

Interview participants described substantial life interference from symptoms with impact on social relationships, financial stability, and quality of life. We previously published a comprehensive qualitative analysis of these interviews.[6] Participants identified degree of life interference and symptom severity as the most important symptom attributes to measure. Interview participants also described treatment-to-treatment variation in symptoms, reporting that the unpredictability of symptoms rendered planning events on dialysis days to be challenging, noting “…some treatments seem to be worse than others…”

Concept elicitation interviews: technology usage and symptom reporting willingness

Table 4 displays patient-reported information technology utilization and preference for symptom reporting modality. Of the 42 interview participants, 24 (57%) used a smartphone, 15 (36%) used a mobile telephone without internet access, and 3 (7%) did not use any mobile telephone. Of the 24 smartphone users, 15 (63%) used apps. All participants described willingness to report symptoms to their care teams, with 28 (67%) reporting willingness to do so via smartphone or e-tablet without assistance, and 42 (100%) reporting willingness to do so by e-tablet with assistance. All participants reported that symptom PROM completion every treatment would be too burdensome. Most participants expressed willingness to report symptoms weekly but stressed the importance of timely clinician follow-up. Others recognized that ability and/or interest in PROM completion might be contingent upon health status. One participant stated, “…gosh, it kind of depends on how you’re feeling.”

Table 4.

Patient information technology utilization and preference for symptom reporting modality from concept elicitation interviews (N=42).a

| Characteristic | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Cell phone use | |

| Mobile phone (no internet) | 15 (35.7) |

| Smartphone | 24 (57.2) |

| No Mobile phone | 3 (7.1) |

| Text message useb | 26 (66.7) (n=39) |

| Smartphone app usec | 15 (62.5) (n=24) |

| Health app usec | 7 (30.4) (n=23) |

| Willing to report symptoms | 42 (100.0) |

| Willing to report symptoms via paper questionnaired | 30 (71.4) (n=33) |

| Willing to report symptoms via e-tablet or smartphone app without assistance | 28 (66.7) |

| Willing to report symptoms via e-tablet with assistance | 42 (100.0) |

Values reported as n (%) or mean ± standard deviation; median [interquartile range]; (range).

Among individuals reporting mobile or smartphone use.

Among individuals reporting smartphone use.

Of the 9 individuals not willing to report symptoms via paper questionnaire, 7 were willing to report symptoms by e-tablet or smartphone app.

Measure Drafting

Harmonized concepts from the systematic literature review and concept elicitation interviews informed initial PROM drafting. To balance symptom capture and measure burden, we selected the most frequently reported symptoms (threshold: >10% of participants) for PROM inclusion. Because some patients have significant symptoms that did not reach the 10% threshold, we added one item where the patient can write-in a symptom. Literature review findings supported our item selection. We chose to assess the symptom attributes of severity (6-point Likert scale) and interference with daily activities (5-point Likert scale) based on concept elicitation findings. Due to treatment-to-treatment symptom variability, we selected a look-back period of a single treatment to avoid recall bias and facilitate linkage of symptoms to a specific treatment. Finally, to capture fatigue or “wash-out” after treatment, we used the previously validated “time to recovery” question. The question asks “How long does it take you to recover from a dialysis session?” Existing data support this question’s interpretability, test-retest reliability, convergent and divergent validity, and sensitivity to change.[25] To maintain look-back period consistency throughout the measure, we altered the question to: “After your last dialysis treatment, how long did it take you to recover?”

Evaluation and Refinement of the Preliminary Symptom PROM

Table 5 displays a summary of cognitive debriefing interview results and associated PROM updates.

Table 5.

Key cognitive interview findings with instrument updates and rationale (N=52).

| Content area | Instrument wording | Cognitive interview findings | Instrument update |

|---|---|---|---|

| Round 1 (n= 18) | |||

| Instructions | Nonea | Participants suggested adding instructions. | Added “Please respond to each statement by marking one box per row” at beginning of instrument. |

| Symptoms (n=13)b | |||

| Overall | Participants generally understood the symptoms with the following exceptions. |

--- | |

| Feel restless | Participants did not understand the term “feel restless” and suggested adding language that is more descriptive. |

Changed to “restless legs or difficulty keeping legs still” for clarification. |

|

| Nausea and/or vomiting | Participants reported experiencing nausea without vomiting and vice versa. Some participants did not understand the terms “nausea” and “vomiting” |

Split single item into two items to increase specificity. Added “or upset stomach” to nausea item and “or throwing up” to vomiting item. |

|

| Thirst | Some participants interpreted “thirst” as present only when the sensation was severe enough to prompt drinking. Participants described a continuum of related symptoms (e.g. dry mouth) that were related but not severe enough to prompt drinking. |

Added “or dry mouth” to thirst item to broaden concept. |

|

| Self-report symptom | Some participants did not understand the term “self-report”. |

Changed to “Other (write-in)” to improve comprehension. |

|

| Symptom attribute(s) | Severity Interference with daily activities |

All participants understood the terms “severity” and “interference with daily activities.” |

No change to severity. Removed interference with daily activities based on burden assessment (see below). |

| Likert scale(s) | Severity: 6-point (none, mild, some moderate, severe, very) Daily activity interference: 5- point (not at all, a little bit, somewhat, quite a bit, very much) |

Some participants had difficulty distinguishing between “some” and “moderate” severity. |

Changed severity to 5-point scale by removing “some” category. |

| Recall period | Most recent dialysis treatment | Many participants interpreted “most recent” as a general timeframe. Many participants reported symptoms in general rather than symptoms during the most recent (single) treatment. |

Changed to “last dialysis treatment” to clarify intended recall period. |

| Burden | 12 symptoms (including self- report); time to recovery question; 2 attributes |

Participants felt that severity and interference with daily life were redundant and added unnecessary length to the instrument. |

Removed interference with daily activities assessment to decrease instrument burden. |

| Round 2 (n=21) | |||

| Instructions | Please respond to each statement by marking one box per row. |

Participants understood the instructions, but suggested adding reinforcing language about intended recall period (see below). |

Added: “We are interested in the symptoms you had during your last dialysis treatment. Respond only based on your last treatment |

| Symptoms (n=14)b | |||

| Overall | All participants understood all symptoms. | No change | |

| Restless legs or difficulty keeping legs still |

All participants understood the updated term. | No change | |

| Nausea or upset stomach | All participants understood the updated term. | No change | |

| Vomiting or throwing up | All participants understood the updated term. | No change | |

| Thirst or dry mouth | All participants understood the updated term. | No change | |

| Other (write-in) | All participants understood the updated term. | No change | |

| Symptom attribute | Severity | All participants understood the symptom attribute assessment. |

No change |

| Likert scale | 5-point (none, mild, moderate, severe, very severe) |

All participants displayed good understanding of the 5-point gradation scale. |

No change |

| Recall period | Last dialysis treatment | Some participants overlooked the recall period, “During your last dialysis treatment” (listed once at the top of the symptom list) and reported symptoms “in general” rather than symptoms during the last dialysis treatment. Many participants suggested repeating the intended recall period with each symptom. Some participants suggested adding information about the recall period to the instructions in addition to repeating the recall period with each symptom. |

Added: “During your last dialysis treatment, did you have…” to each symptom item. Added: “We are interested in the symptoms you had during your last dialysis treatment. Respond only based on your last treatment.” |

| Burden | 13 symptoms (including self- report); time to recovery question; 1 attribute |

All participants felt the instrument length was reasonable. |

No change |

| Round 3 (n=13) | |||

| Instructions | Please respond to each statement by marking one box per row. We are interested in the symptoms you had during your last dialysis treatment. Respond only based on your last treatment. |

All participants understood the directions. | No change |

| Symptoms (n=14)b | |||

| Overall | All participants understood all symptoms. | No change | |

| Symptom attribute | Severity | All participants understood the symptom attribute assessment. |

No change |

| Likert scale | 5-point (none, mild, moderate, severe, very severe) |

All participants displayed good understanding of the 5-point gradation scale. |

No change |

| Recall period | Last dialysis treatment (listed on every symptom row) |

All participants responded to questions using the intended recall period. |

No change |

| Burden | 13 symptoms (including self- report); time to recovery question; 1 attribute |

No change | |

No introductory instructions beyond question stems

Total symptom number includes a “write-in” symptom and the time to recovery question. Symptoms listed are those where participants had questions or expressed confusion.

Round one cognitive interviews

All round 1 cognitive interview participants expressed at least some difficulty with the symptom PROM. Difficulties arose with comprehension of instructions, 4 of the 12 symptom items, symptom gradation scaling, and measure burden. Of the 18 round 1 interview participants, 13 (72%) suggested adding an instructions section to the beginning of the measure. One individual suggested, “Say ‘check one box’ or somethin’.”

Most participants displayed good understanding of the 12 symptom items, but 9 (50%) had difficulty with the item “feel restless”, 4 (22%) had difficulty with the item “nausea/vomiting”, and 5 (28%) had difficulty with the term “self-report.” Upon interviewer probing, 8 (44%) reported experiencing nausea without vomiting or vice versa, and only 4 (22%) reported experiencing the 2 symptoms simultaneously. Also upon probing, some participants answering “none” to the “thirst” item reported related symptoms such as “dry” or “cotton” mouth. These participants described marking “none” because their dry mouth sensation did not require drinking fluid to satiate, rather hard candy or food. All participants displayed good understanding of the symptom attributes of severity and interference with daily activities. However, 2 (11%) had difficulty distinguishing “some” from “mild” or “moderate” when grading symptom experiences.

Of the 18 participants, 10 (56%) interpreted the recall period of “most recent hemodialysis treatment” as a general timeframe, answering symptom questions based on their overall symptom experiences rather than their last treatment. Participants suggested changing the reference timeframe to “last treatment” to improve comprehension. In general, participants did not find the PROM overly burdensome, but reported that inclusion of both symptom severity and interference with daily activities was redundant due to perceived similar meanings. Participants recommended dropping the interference scale for the sake of brevity. Participants displayed good understanding of the time to recovery question, describing recovery as: “get yourself back together and normal” and “when you can do what you need to be doing.”

Participant responses led to PROM refinements aimed at increasing clarity and decreasing burden. Specifically, we: 1) added instructions to provide guidance; 2) updated “feel restless” to “restless legs or difficulty keeping legs still” to improve understanding; 3) split “nausea and/or vomiting” into two items to increase specificity; 4) expanded “thirst” to “thirst or dry mouth” to broaden the concept captured; 5) replaced “self-report symptom” with “other (write-in)” to improve comprehension; 6) removed the symptom attribute of interference with daily activities to reduce burden; 7) decreased response options in the severity Likert scale from 6 to 5; and 8) altered recall period description from “most recent treatment” to “last treatment” to increase clarity.

Round two cognitive interviews

We conducted a second round of cognitive interviews with 21 patients to assess the updated PROM. Participant responses during round 2 interviews supported the selection of symptoms and wording changes made in round 1. All participants displayed good understanding of all symptoms including the “other (write-in)” option and time to recovery question. Participants showed improved understanding of the recall period. However, 9 (43%) still responded to the symptom questions “in general.” Upon interviewer probing, 21 (100%) were able to describe symptoms from their last treatment. To emphasize the intended recall period of “last treatment”, 5 (24%) suggested adding reinforcing text to the instructions.

Following round 2 interviews, we made the following PROM refinements to improve comprehension: 1) added “We are interested in the symptoms you had during your last dialysis treatment. Respond only based on your last treatment”; and 2) included the stem, “During your last dialysis treatment, did you have…” with each symptom item.

Round three cognitive interviews

We conducted a third round of cognitive interviews to assess the updated PROM. Round 3 participants confirmed relevance of the included symptoms, expressed no difficulty with comprehension of the items or response options, and reported symptoms based on the intended recall period. Of the 13 round 3 participants, 5 (38%) noted, without probing, that the instructions oriented them to symptoms during their “last treatment.” Several added that they would have been tempted to respond “in general” without the additional reinforcing instructions.

Assessment of burden and overall rating of the instrument

During cognitive interview rounds 2 and 3, participants rated the difficulty of completing the symptom PROM. Of the 34 participants, 17 (50%) rated the PROM very easy, and 15 (44%) rated the PROM easy. Participants described the measure as comprehensive with one noting, “It covers everything and does not feel too long like some of the other surveys we take.” Others commented: “easy,” “short and sweet,” “no big deal,” and “I wish more surveys were like this.”

Most participants thought that the PROM would help dialysis care teams better understand patient symptoms, viewing it as a communication tool. One participant said, “[clinic personnel] would be more aware of what we go through.” Several participants pointed out the importance of administering the PROM repeatedly over time due to symptom fluctuations.

The resultant hemodialysis-related symptom PROM, Symptom Monitoring on Renal Replacement Therapy-Hemodialysis (SMaRRT-HD™), is a 14-item instrument that measures 13 symptoms (12 specific + 1 write-in) with 5-point severity Likert scales (none, mild, moderate, severe, very severe) and dialysis recovery time with a single, previously validated open-ended response question. The measure specifies a recall period of the “last dialysis treatment” for each item.

DISCUSSION

Given the importance of symptoms to patients, frequent under-appreciation of symptoms by providers, and lack of standardized symptom data collection tools, there is a need for a succinct PROM capturing dialysis-related symptoms. We designed SMaRRT-HD™ to assess the most important hemodialysis-related physical symptoms based on evidence from a systematic literature review and patient interviews. Cognitive debriefing interviews yielded evidence that patients understand and are able to complete SMaRRT-HD™ as intended.

SMaRRT-HD™ addresses a measurement gap in hemodialysis research and practice. Despite the substantial impact of symptoms on health-related quality of life among individuals on dialysis, there are few proven treatment strategies to alleviate symptoms. Some symptoms may be related to the hemodialysis procedure itself, rendering them attractive targets for intervention. For example, cramping may occur when fluid removal rates exceed vascular refill rates. Nausea, lightheadedness, and cramping, among other symptoms, may occur with acute blood pressure drops. Despite the plausible associations between symptoms and the dialysis treatment, existing data are inconclusive.[26–28] Inconsistent research findings may, in part, stem from treatment-to-treatment symptom fluctuations and insufficient symptom data measurement. Existing symptom PROMs do not capture the treatment level symptom data necessary to support the systematic study of the associations between symptoms and treatment features such as dialysate composition, rates of fluid removal, and blood pressure variation. The most commonly administered symptom PROM, the KDQOL™ symptom subscale, relies on a 4-week recall period, rendering it impossible to link symptoms to specific treatment characteristics.[11, 29, 30] Furthermore, the KDQOL™ is administered relatively infrequently, often only annually among prevalent patients. The Dialysis Symptom Index (DSI) assesses bother of 30 physical and mood symptoms with a recall period of one week.[31] To-date, the instrument has only been used in research settings. Similar to the KDQOL™, the DSI recall period of one week (3 treatments) precludes linkage of symptoms to individual treatment characteristics. Moreover, the 30-item DSI is lengthy, raising concern about burden if it were to be administered on a weekly or bi-weekly basis. The modified Edmonton Symptom Assessment (ESA), another physical and mood symptom checklist developed for dialysis patients, evaluates symptom severity on a scale of 0–10 at the present time.[32] However, the modified ESA omits common treatment-related symptoms such as cramping and restless legs.

SMaRRT-HD™ is a succinct symptom PROM that assesses physical symptoms from a single dialysis treatment. We selected the symptoms for inclusion based on reporting frequency in concept elicitation interviews. Our literature review supported these symptoms. We chose to focus on physical symptoms to capture symptoms most plausibly related to the dialysis treatment and most likely to fluctuate on a treatment-to-treatment basis. To limit measure burden, we set a 10% reporting frequency threshold for symptom inclusion. This approach resulted in the inclusion of 12 specific symptoms and additional write-in symptoms. Reassuringly, the included symptoms were consistent with existing data,[2, 33] and no missing symptoms were identified during cognitive interviews. Two-thirds of concept elicitation interviewees reported fatigue after dialysis treatments. This is consistent with other reports concluding that 60–97% of individuals on dialysis experience fatigue.[7, 34, 35] There is no universally accepted definition of fatigue in chronic illness, and a recent review of fatigue measures suggests that fatigue among dialysis patients may have up to 11 dimensions.[36] Given the complexity of fatigue and our interest in capturing treatment-related symptoms, we included the previously validated time-to-recovery question in our measure.

We selected a recall period of “last dialysis treatment” to facilitate linkage of symptoms to treatment-level data and limit influence from factors known to affect symptom reporting (e.g., symptom intensity and proximity to report).[37, 38] Cognitive interview participants displayed excellent ability to recall symptoms from the prior treatment. Among in-center hemodialysis patients, the “last dialysis treatment” recall period may range 48 to 72 hours depending on the weekday of assessment. We intend for the measure to be administered at the beginning of a dialysis treatment, with a recall to the previous treatment. This approach facilitates assessment of symptoms and dialysis recovery time from the same treatment. We developed SMaRRT-HD™ with the intention of converting the validated paper measure to an e-tablet measure to support integration of symptom data into the electronic health record. While only two-thirds of concept elicitation interviewees expressed willingness to use an e-tablet for symptom reporting without assistance, all expressed interest in using an e-tablet with assistance or after training.

We developed SMaRRT-HD™ for use in both clinical practice and research. Consistent with prior reports, participants desired more interaction with their providers around symptoms.[5, 6] Many participants indicated that SMaRRT-HD™ responses would be useful for their care teams. For instance, in clinical practice, this PROM may facilitate conversations about symptoms between patients and dialysis care technicians, nurses, and medical providers. This is particularly important given our previously reported findings that patients often under-report their symptoms.[6] Symptom data collection via SMaRRT-HD™ will also enable systematic investigation of the associations between physical symptoms and aspects of the dialysis treatment. Such research is essential to advance therapeutic interventions for symptom alleviation.

Strengths of this research include the size and heterogeneous nature of the interview sample. We recruited patients from various sources including academic-affiliated institutions and community-based practices in diverse U.S. regions. The sample size (n=94) was large for this study type. Study limitations include recruitment of English-speaking participants only. Individuals from different cultural or ethnic backgrounds may prioritize and report different symptoms and/or interpret symptom terminology differently.[39–41] Measure translation and subsequent content validation studies are needed to inform symptom PROMs in other languages. Second, symptom reports among concept elicitation interview participants vs. non-participants may differ, and we are unable to account for this potential bias. Third, we excluded children and individuals receiving home hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis. Symptoms likely differ in these distinct populations and merit dedicated study and measure development. Fourth, to limit burden and support more frequent PROM administration, we included one item per symptom. Single items are more vulnerable to random measurement errors and unknown biases in meaning and interpretation.[42]

SMaRRT-HD™ is a content valid dialysis-related, physical symptom PROM for adults receiving outpatient maintenance hemodialysis. Next steps in SMaRRT-HD™ development involve evaluation of psychometric properties, development of measure scoring, and conversion to an e-tablet-based application with integration into the electronic health record.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank all study participants for sharing their experiences and perspectives on hemodialysis-related symptoms and the symptom measure. The authors also thank Dr. Emaad Abdel-Rahman and research liaisons, Lisa Johnson and Nino McHedlishvili, for their help in facilitating concept elicitation interviews at the University of Virginia. Finally, the authors thank the advisors who contributed to measure development: Derek Forfang, Lori Hartwell, Robert Kossmann, Mahesh Krishnan, Francesca Tentori, and David Thissen.

COMPLIANCE WITH ETHICAL STANDARDS

Funding: This work was supported by an unrestricted, investigator-initiated research grant (A17-1082) from Renal Research Institute (RRI), a subsidiary of Fresenius Medical Care (FMC), North America. RRI played no role in study design; collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; writing the report; or the decision to submit the report for publication. Dr. Flythe is supported by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases of the National Institute of Health Grant K23 DK109401.

Dr. Flythe has received investigator-initiated research funding from the Renal Research Institute, a subsidiary of Fresenius Medical Care, North America. In the past 2 years, Dr. Flythe has received consulting fees from Fresenius Medical Care, North America and speaking honoraria from American Renal Associates, American Society of Nephrology, Baxter, National Kidney Foundation, and multiple universities. Dr. Dalrymple and Ms Wingard are employees of Fresenius Medical Care, North America and have performance share-options/stock-options.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: Miss Dorough, Mrs. Narendra and Dr. DeWalt declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethics Approval: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (17-0038 and 17-1252) and the University of Virginia (19928)

Informed Consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Saran R, Robinson B, Abbott KC, Agodoa LY, Albertus P, Ayanian J, et al. : U.S. Renal Data System 2016 annual data report: Epidemiology of kidney disease in the United States. Am J Kidney Dis 69[Suppl 1]: A7–A8, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abdel-Kader K, Unruh ML, Weisbord SD: Symptom burden, depression, and quality of life in chronic and end-stage kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2009, 4(6):1057–1064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Merkus MP, Jager KJ, Dekker FW, de Haan RJ, Boeschoten EW, Krediet RT: Physical symptoms and quality of life in patients on chronic dialysis: results of The Netherlands Cooperative Study on Adequacy of Dialysis (NECOSAD). Nephrol Dial Transplant 1999, 14(5):1163–1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weisbord SD, Fried LF, Arnold RM, Fine MJ, Levenson DJ, Peterson RA, Switzer GE: Prevalence, severity, and importance of physical and emotional symptoms in chronic hemodialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol 2005, 16(8):2487–2494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cox KJ, Parshall MB, Hernandez SH, Parvez SZ, Unruh ML: Symptoms among patients receiving in-center hemodialysis: A qualitative study. Hemodial Int 2017, 21(4):524–533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Flythe JE, Dorough A, Narendra JH, Forfang D, Hartwell L, Abdel-Rahman E: Perspectives on symptom experiences and symptom reporting among individuals on hemodialysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2018. April 16 Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Evangelidis N, Tong A, Manns B, Hemmelgarn B, Wheeler DC, Tugwell P, Crowe S, Harris T, Van Biesen W, Winkelmayer WC et al. : Developing a Set of Core Outcomes for Trials in Hemodialysis: An International Delphi Survey. Am J Kidney Dis 2017, 70(4):464–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Manns B, Hemmelgarn B, Lillie E, Dip SC, Cyr A, Gladish M, Large C, Silverman H, Toth B, Wolfs W et al. : Setting research priorities for patients on or nearing dialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2014, 9(10):1813–1821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weisbord SD, Fried LF, Mor MK, Resnick AL, Unruh ML, Palevsky PM, Levenson DJ, Cooksey SH, Fine MJ, Kimmel PL et al. : Renal provider recognition of symptoms in patients on maintenance hemodialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2007, 2(5):960–967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Basch E, Deal AM, Kris MG, Scher HI, Hudis CA, Sabbatini P, Rogak L, Bennett AV, Dueck AC, Atkinson TM et al. : Symptom Monitoring With Patient-Reported Outcomes During Routine Cancer Treatment: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Clin Oncol 2016, 34(6):557–565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peipert JD, Bentler PM, Klicko K, Hays RD: Psychometric Properties of the Kidney Disease Quality of Life 36-Item Short-Form Survey (KDQOL-36) in the United States. Am J Kidney Dis 2018, 71(4):461–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Patrick DL, Burke LB, Gwaltney CJ, Leidy NK, Martin ML, Molsen E, Ring L: Content validity--establishing and reporting the evidence in newly developed patient-reported outcomes (PRO) instruments for medical product evaluation: ISPOR PRO good research practices task force report: part 1--eliciting concepts for a new PRO instrument. Value Health 2011, 14(8):967–977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Patrick DL, Burke LB, Gwaltney CJ, Leidy NK, Martin ML, Molsen E, Ring L: Content validity--establishing and reporting the evidence in newly developed patient-reported outcomes (PRO) instruments for medical product evaluation: ISPOR PRO Good Research Practices Task Force report: part 2--assessing respondent understanding. Value Health 2011, 14(8):978–988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services FaDA, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER), Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER), Center for Devices and Radiological Health (CDRH). Guidance for Industry Patient Reported Outcome Measures: Use in Medical Product Development to Support Labeling Claims Silver Spring, MD: U.S. Food and Drug Administration; 2009. December 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Flythe JE, Powell JD, Poulton CJ, Westreich KD, Handler L, Reeve BB, Carey TS: Patient-Reported Outcome Instruments for Physical Symptoms Among Patients Receiving Maintenance Dialysis: A Systematic Review. Am J Kidney Dis 2015, 66(6):1033–1046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sandelowski M: Combining qualitative and quantitative sampling, data collection, and analysis techniques in mixed-method studies. Res Nurs Health 2000, 23(3):246–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patton M: Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods, 4th edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paige SR, Krieger JL, Stellefson M, Alber JM: eHealth literacy in chronic disease patients: An item response theory analysis of the eHealth literacy scale (eHEALS). Patient Educ Couns 2016, 100(2):320–326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Norman CD, Skinner HA: eHEALS: The eHealth Literacy Scale. J Med Internet Res 2006, 8(4):e27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Norman CD, Skinner HA: eHealth Literacy: Essential Skills for Consumer Health in a Networked World. J Med Internet Res 2006, 8(2):e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ericsson KA, Simon HA: Verbal reports as data. Psychological Review 1980, 87:215–251. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Willis GB: Cognitive interviewing: A tool for improving questionnaire design Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morris NS, MacLean CD, Chew LD, Littenberg B: The Single Item Literacy Screener: evaluation of a brief instrument to identify limited reading ability. BMC Fam Pract 2006, 7:21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Borson S, Scanlan JM, Chen P, Ganguli M: The Mini-Cog as a screen for dementia: validation in a population-based sample. J Am Geriatr Soc 2003, 51(10):1451–1454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lindsay RM, Heidenheim PA, Nesrallah G, Garg AX, Suri R, Centre DHSGLHS: Minutes to recovery after a hemodialysis session: a simple health-related quality of life question that is reliable, valid, and sensitive to change. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2006, 1(5):952–959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Davison SN, Jhangri GS, Johnson JA: Longitudinal validation of a modified Edmonton symptom assessment system (ESAS) in haemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2006, 21(11):3189–3195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Virga G, Mastrosimone S, Amici G, Munaretto G, Gastaldon F, Bonadonna A: Symptoms in hemodialysis patients and their relationship with biochemical and demographic parameters. Int J Artif Organs 1998, 21(12):788–793. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Scherer JS, Combs SA, Brennan F: Sleep Disorders, Restless Legs Syndrome, and Uremic Pruritus: Diagnosis and Treatment of Common Symptoms in Dialysis Patients. Am J Kidney Dis 2017, 69(1):117–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hays RD, Kallich JD, Mapes DL, Coons SJ, Carter WB: Development of the kidney disease quality of life (KDQOL) instrument. Qual Life Res 1994, 3(5):329–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rao S, Carter WB, Mapes DL, Kallich JD, Kamberg CJ, Spritzer KL, Hays RD: Development of subscales from the symptoms/problems and effects of kidney disease scales of the kidney disease quality of life instrument. Clin Ther 2000, 22(9):1099–1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weisbord SD, Fried LF, Arnold RM, Rotondi AJ, Fine MJ, Levenson DJ, Switzer GE: Development of a symptom assessment instrument for chronic hemodialysis patients: the Dialysis Symptom Index. J Pain Symptom Manage 2004, 27(3):226–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Davison SN, Jhangri GS, Johnson JA: Cross-sectional validity of a modified Edmonton symptom assessment system in dialysis patients: a simple assessment of symptom burden. Kidney Int 2006, 69(9):1621–1625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Flythe JE, Hilliard T, Castillo G, Ikeler K, Orazi J, Abdel-Rahman E, Pai AB, Rivara MB, St Peter WL, Weisbord SD et al. : Symptom Prioritization among Adults Receiving In-Center Hemodialysis: A Mixed Methods Study. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2018, 13(5):735–745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tong A, Manns B, Hemmelgarn B, Wheeler DC, Evangelidis N, Tugwell P, Crowe S, Van Biesen W, Winkelmayer WC, O’Donoghue D et al. : Establishing Core Outcome Domains in Hemodialysis: Report of the Standardized Outcomes in Nephrology-Hemodialysis (SONG-HD) Consensus Workshop. Am J Kidney Dis 2017, 69(1):97–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jhamb M, Liang K, Yabes J, Steel JL, Dew MA, Shah N, Unruh M: Prevalence and correlates of fatigue in chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal disease: are sleep disorders a key to understanding fatigue? Am J Nephrol 2013, 38(6):489–495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ju A, Unruh ML, Davison SN, Dapueto J, Dew MA, Fluck R, Germain M, Jassal SV, Obrador G, O’Donoghue D et al. : Patient-Reported Outcome Measures for Fatigue in Patients on Hemodialysis: A Systematic Review. Am J Kidney Dis 2018, 71(3):327–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gedney JJ, Logan H, Baron RS: Predictors of short-term and long-term memory of sensory and affective dimensions of pain. J Pain 2003, 4(2):47–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brodie EE, Niven CA: Remembering an everyday pain: the role of knowledge and experience in the recall of the quality of dysmenorrhoea. Pain 2000, 84(1):89–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lavin R, Park J: A characterization of pain in racially and ethnically diverse older adults: a review of the literature. J Appl Gerontol 2014, 33(3):258–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bagayogo IP, Interian A, Escobar JI: Transcultural aspects of somatic symptoms in the context of depressive disorders. Adv Psychosom Med 2013, 33:64–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Koffman J, Morgan M, Edmonds P, Speck P, Higginson I: Cultural meanings of pain: a qualitative study of Black Caribbean and White British patients with advanced cancer. Palliat Med 2008, 22(4):350–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hoeppner BB, Kelly JF, Urbanoski KA, Slaymaker V: Comparative utility of a single-item versus multiple-item measure of self-efficacy in predicting relapse among young adults. J Subst Abuse Treat 2011, 41(3):305–312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]