Abstract

Purpose

Teen readiness assessments may provide a developmental indicator of the transfer of responsibility for health self-management from caregivers to teens. Among urban adolescents with asthma, we aimed to describe teen readiness for talking with providers and identify how readiness relates to responsibility for asthma management, medication beliefs, and clinical outcomes

Methods

Teens and caregivers enrolled in the School-based Asthma Care for Teens trial in Rochester, NY completed in-home surveys. We classified Ready Teens as those reporting a score of 5 on both items of the Transition Readiness Assessment Questionnaire talking with providers subscale. We performed bivariate analyses to detect differences between Ready Teens and Other Teens in teen- and caregiver-reported responsibility, teen medication beliefs, and clinical outcomes (medication adherence over the past 2 weeks, and healthcare use over the past year).

Results

Among this sample of 251 adolescents (mean age: 13.4yrs.), 35% were classified as „Ready.‟ Ready Teens were more likely than Other Teens to want to use a controller medication independently (7.6 vs. 6.5 out of 10, P<0.01) and to have confidence in this ability (8.4 vs. 7.6 out of 10, P=0.02). Teens reported poor adherence (missed 52.9% of prescribed controller doses), with no differences in responsibility or clinical outcomes based on level of teen readiness for talking with providers.

Conclusions

In urban adolescents with poorly controlled asthma, a higher level of teen readiness for talking with providers is associated with higher perceptions of independence in medication taking, but does not appear to relate to clinical outcomes

Keywords: adolescents, transitions to adult care, asthma, self-management

Adolescents with chronic diseases are vulnerable during the transition from pediatric to adult care. This time is often complicated by unmet and changing health care needs as well as fragmented care [1,2], which result in worsened health outcomes [3]. While healthcare-system factors contribute [4], worsened outcomes in adolescents with chronic diseases are also related to increased teen autonomy paired with risky decision-making due to sensation-seeking behaviors and peer influences [5]. Despite these challenges, an adolescent’s intellectual maturity and tendency to respond to rewards and social cues makes this an ideal time to increase a motivated teen’s engagement in their care [5,6].

The period of healthcare transition may be particularly important for the 7 million pediatric patients diagnosed with asthma [7], since the transfer of responsibility for medication management from caregivers to children often starts before adolescence. By 11 years of age, children are already assuming half of the responsibility for daily asthma medication management [8]. Some caregivers expect children as young as 5 years old to manage medications [9,10]. An early transfer of responsibility from caregiver to youth, and caregiver/child disagreement over who is responsible, may be particularly common among urban youth with asthma [11] and contribute to higher disease morbidity. While child responsibility for asthma management increases with age [12–14], medication adherence drops considerably during teen years [12]. Using developmentally appropriate transition counseling [6,15], pediatricians may have an opportunity to facilitate safer shifts for health management tasks from caregiver to teen.

Teen and caregiver transition readiness assessments may help guide this transition counseling [15]; however, the task of identifying which teens are ready to accept responsibility for health-management is not well defined. The 20 questions of the Transition Readiness Assessment Questionnaire (TRAQ) serve to estimate teens’ perceptions of their readiness to self-manage five skill domains (managing medications, appointment keeping, tracking health issues, talking with providers, and managing daily activities), and have been validated in a sample of teens and young adults (ages 14–21 years) with special health care needs [16]. An adolescent’s level of readiness might be anticipated to positively affect outcomes [17], but the research to date is mixed on whether overall TRAQ and similar readiness scores are associated with improved clinical outcomes or transition success in youth with chronic conditions. van Staa et al. found that higher levels of transition readiness are associated with greater self-efficacy in managing medical care during inpatient encounters [18], but others did not observe associations between readiness and medication adherence or clinical outcomes [19].

Adolescents with asthma want to be active participants in conversations about self-management [20,21], and developmentally are more likely to develop effective conversational skills prior to executive planning and decision making skills [5]. The teen-provider relationship is associated with teens’ engagement in care [22], motivation to use asthma medications [23], asthma medication adherence [24], reduced symptoms, and improved quality of life [25]. Busy clinicians could feasibly use a two-item talking with providers sub-scale in practice to identify early adolescents with asthma who are ready to talk with health professionals. Therefore, we focus here on the “talking with providers” sub-scale from the TRAQ [16].

While teen-provider communication is associated with positive health outcomes in teens with asthma [23–25], it is unclear whether teen readiness to talk with providers might correspond with increasing self-management responsibility, medication beliefs, adherence, or healthcare use. Among a population of urban adolescents with persistent asthma, our objectives were to 1) describe teen readiness for talking with providers; 2) identify whether teen readiness for talking with providers is associated with teen- and caregiver-reported responsibility for asthma management; and 3) examine associations between teen readiness to talk with providers and medication beliefs, medication adherence, and healthcare use. We hypothesized that teen readiness for talking with providers would be positively associated with teen responsibility, positive medication beliefs, and key clinical outcomes (including medication adherence and primary care use), and negatively associated with acute healthcare utilization (emergency department (ED) visits and hospitalization). We secondarily explored early teens’ readiness for managing daily activities outside of medical care, but did not analyze its associations with outcomes or examine the other three TRAQ domains.

Methods

Settings and participants

As part of the School-based Asthma Care for Teens (SB-ACT) study, we performed a cross-sectional analysis of data from baseline surveys completed by “urban” teens with persistent asthma (recruited from secondary schools within the city district in Rochester, NY). SB-ACT is an ongoing randomized controlled clinical trial designed to promote developmentally appropriate independence with asthma medication management in a school-based setting. A member of the SB-ACT team systematically screened caregivers of teens aged 12–16 years with a history of breathing problems identified on school medical history forms by phone for enrollment.

Teen/caregiver dyads were eligible for inclusion if the caregiver reported that the teen had physician-diagnosed asthma with persistent severity or poor control, according to the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) asthma management guideline criteria [26]. Exclusion criteria included an inability to speak and understand English, a lack of access to a working phone for follow-up surveys, the presence of significant medical conditions (cystic fibrosis, congenital heart disease, chronic lung disease, or intellectual disability), or foster care placement in which a legal guardian’s consent could not be obtained.

The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board at the University of Rochester Medical Center. Caregivers provided written informed consent and teens provided verbal (12 year olds) or written (13–16 year olds) assent. Members of the study team conducted baseline in-home surveys of the enrolled teens and their primary caregivers prior to their random assignment into the trial. This sub-analysis utilizes baseline data (prior to any intervention) for subjects who completed transition-related study measures during years 1–3 of the 5-year study (enrolled during the fall seasons of 2014–2016).

Study Measures

Demographic and health characteristics.

The baseline survey assessed demographic and health characteristics reported by teen participants, including child age, sex, race, ethnicity, depression (based on the Center for Epidemiologic Studies (CES) depression scale), and disease severity. Disease severity was determined according to NHLBI asthma guidelines [26] based on teen-reported frequency of rescue inhaler use, daytime or nighttime symptoms in the past four weeks, and frequency of asthma exacerbations requiring systemic corticosteroids in the past year. Baseline demographic information reported by caregivers included caregiver age, caregiver’s highest level of educational attainment, caregiver’s marital status, and child’s health insurance status.

Teen Transition Readiness.

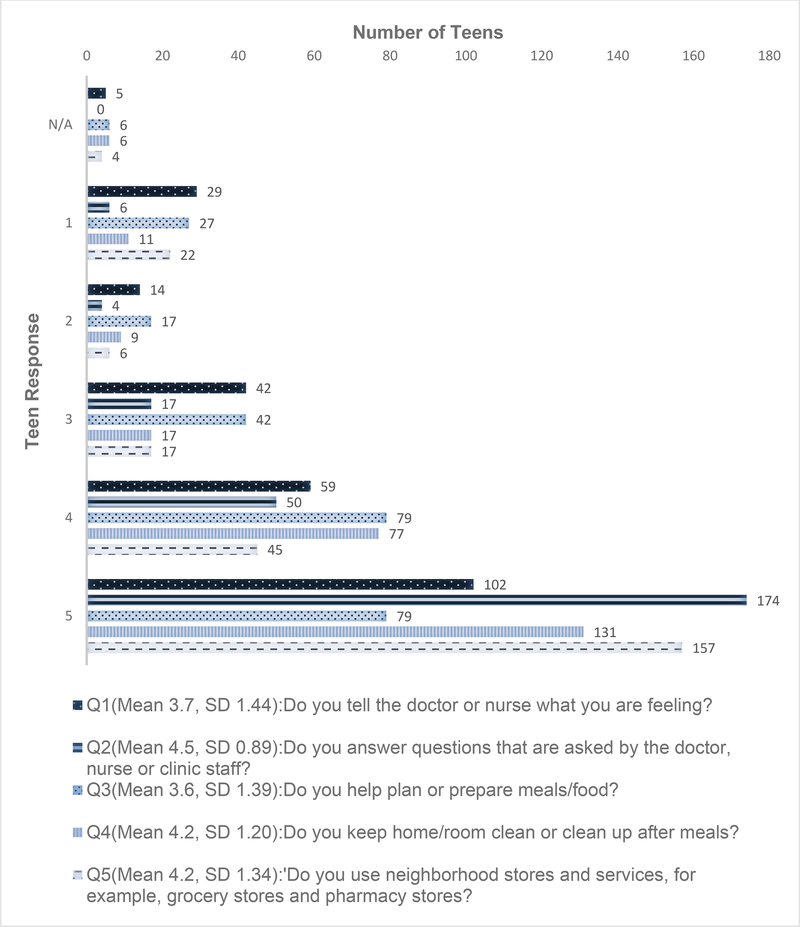

Teens answered questions (included in Figure 1) from the TRAQ [16], rating their readiness for “talking with providers” (Q1 and Q2) and “managing daily activities” (Q3, Q4, and Q5). Possible responses are scaled in 5 categories: “Yes, I always do this when I need to”=5, “Yes, I have started doing this”=4, “No, but I am learning to do this”=3, “No, but I want to learn”=2, “No, I do not know how”=1. Transition readiness assessment was not a primary goal of the SB-ACT study; therefore, we selected 2 sub-scales representing the most developmentally appropriate tasks for early teens in order to minimize participant burden. Both sub-scales had acceptable reliability in the original validation study [16]: “talking with providers” (α = 0.80) and “managing daily activities” (α = 0.67). We classified Ready Teens as those who reported a score of 5 on both “talking with providers” sub-scale items, focusing on the potential for teen-provider communication to be associated with outcomes.

Figure 1:

Teen Readiness for “Talking with Providers” and “Managing Daily Activities” in Urban Teens with Asthma (n = 251)

Responsibility Scale.

Teens and caregivers independently rated their own perceived level of responsibility for nine asthma management tasks on a scale adapted by investigators from similar previous assessments used in asthma [27] and type 1 diabetes [28,29]. Asthma management tasks assessed in this scale include: remembering to take asthma medications, getting an asthma medication so that it can be taken, deciding to take asthma medications as needed, getting asthma medication refills, having asthma medications available when away from home, avoiding asthma triggers, choosing to rest when wheezing, deciding to go to the emergency room, and talking to the doctor about asthma. Ratings for each task were scaled from 1 to 3 points: 1 point if the caregiver is responsible, 2 points if the caregiver and teen share equal responsibility, and 3 points if the teen is responsible. The sum score ranges from 9 points (caregiver responsible for all tasks) to 27 points (teen responsible for all tasks).

Teen Medication Beliefs.

Teens considered taking “a daily medication the way the doctor says on your own every day without a caregiver’s help.” Using 10-point Likert scales, teens rated their perception of the importance (“not at all important” to “extremely important”), their desire (“don’t want to take it at all” to “really want to take it”), and their confidence (“not at all sure” to “completely sure”) in independent daily medication use. Teens also rated their self-efficacy to confidently take daily controller medications “the way the doctor said” under 12 circumstances listed in Table 3 using a 10-point Likert scale ranging from “not at all sure” (1 point) to “completely sure” (10 points). Investigators adapted these survey items from similar studies of teen asthma medication use [30,31].

Table 3:

Comparison of Teen Readiness for Talking with Providers and Medication Beliefs

| Ready Teens | Other Teens | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 87 | n = 164 | ||

| In regards to your ability to take a daily medication the way the doctor says on your own every day without a caregiver’s help… | |||

| …how important do you think it is? | 8.7 (2.2) | 8.2 (2.3) | 0.06 |

| …how much do you want to do this? | 7.6 (2.7) | 6.5 (2.8) | < 0.01* |

| …how confident are you that you can? | 8.4 (2.3) | 7.6 (2.5) | 0.02* |

| How confident are you that you could take a daily medication the way the doctor said… | |||

| …Every day? | 8.0 (2.7) | 7.6 (2.7) | 0.24 |

| …When you don’t feel well? | 8.8 (2.1) | 7.5 (2.7) | < 0.01* |

| …When you are tired or sleepy? | 5.9 (3.3) | 4.5 (3.0) | < 0.01* |

| …When you don’t want to be told what to do? | 6.6 (3.5) | 5.6 (3.3) | 0.04* |

| …When you want to do something else? | 6.7 (3.2) | 5.6 (3.2) | 0.01* |

| …When you are in a bad mood? | 5.9 (3.6) | 4.8 (3.3) | 0.02* |

| …If your caregiver does not remind you? | 6.6 (3.3) | 5.6 (3.3) | 0.03* |

| …When you are in a rush? | 5.8 (3.3) | 4.9 (3.1) | 0.04* |

| …When you feel just fine? | 5.7 (3.5) | 5.2 (3.5) | 0.30 |

| …When your friends are around? | 7.7 (3.1) | 6.5 (3.3) | < 0.01* |

| …When you don’t feel like taking medicine? | 5.8 (3.4) | 4.5 (3.1) | < 0.01* |

| …When you’re around people you don’t know well? | 7.6 (3.3) | 6.1 (3.5) | < 0.01* |

| Sum for confidence scale items | 81.0 (26.1) | 68.4 (23.7) | < 0.01* |

| Cronbach α = 0.878 | |||

P-value < 0.05 is considered to be statistically significant.

Medication Adherence.

Teens who endorsed having a daily asthma controller medication were asked to report the number of controller medication doses that they missed in the past two weeks. They also reported the number of controller medication doses that they are supposed to take each day. This number was used to calculate the percentage of missed doses over the two week period.

Healthcare Use.

Teens reported their healthcare use over the past 12 months: the number of asthma-related outpatient visits, ED/urgent care visits, or inpatient hospitalizations.

Statistical analysis

We used descriptive statistics to describe transition readiness scores for the entire sample (n=251). We calculated the Cronbach α to assess reliability of the medication beliefs scale used in this study. We performed bivariate analyses using Chi Square and Fischer’s exact test to assess for associations between transition readiness for talking with providers and all other measures, including demographics, level of responsibility, medication beliefs, adherence, and healthcare use. We used the Spearman correlation statistic to compare teen and caregiver responsibility sum scores, and Mann-Whitney tests to compare responsibility sum scores between Ready and Other Teens. Multivariate regression analysis was performed to control for potential confounding demographic variables (teen age, teen depression, race, and caregiver education); however, reported associations were not changed (data not shown). Finally, we performed an additional sub-group analysis including teens who reported using a daily controller medication (n=151) to examine associations between readiness for talking with providers and medication beliefs or adherence.

Results

Participants

At the time of this analysis, 280 caregiver and teen dyads had completed the SBACT baseline survey (participation rate 79%). We did not administer transition-related measures to 29 subjects during year 1, and these were excluded. Hence this sample comprised 251 caregiver and teen dyads (90% of enrolled dyads). The mean age for teen participants was 13.4 years, and for caregivers was 40.4 years. A large majority of teen participants identified with a minority race/ethnicity (Black: 53%; Hispanic: 33%) and had public insurance (84%). All caregivers reported persistent asthma symptoms for their teens during screening for the study, but many teens (43%) reported recent intermittent symptoms. Just under two thirds (64%) of teens reported having a prescribed controller medication at baseline. Basic demographic factors (Table 1) did not differ significantly when teens prescribed a controller medication at baseline were compared to those without a controller (data not shown).

Table 1:

Comparison of baseline demographic factors in Ready Teens versus Other Teens (based on “Talking with Providers” subscale), n (%)

| Ready Teens | Other Teens | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| n=87 | n=164 | ||

| Teen Characteristics | p-value* | ||

| Mean Age (years) | 13.5 | 13.4 | 0.45 |

| Disease Severity | |||

| Mild Intermittent | 41 (48%) | 67 (41%) | 0.52 |

| Mild Persistent | 29 (34%) | 57 (35%) | |

| Moderate/Severe Persistent | 16 (18%) | 39 (24%) | |

| Prescribed Daily | |||

| Controller Medication | 53 (61%) | 107 (66%) | 0.49 |

| Teen Depression (CES+) | 19 (22%) | 53 (33%) | 0.11 |

| Sex (Male) | 54 (62%) | 82 (50%) | 0.08 |

| Race | |||

| White | 9 (10%) | 5 (3%) | 0.04* |

| Black | 47 (54%) | 87 (53%) | |

| Other | 31 (36%) | 72 (44%) | |

| Ethnicity (Hispanic) | 30 (35%) | 54 (33%) | 0.89 |

| Public Insurance | 73 (84%) | 137 (84%) | 0. 86 |

| Caregiver Characteristics | p-value* | ||

| Mean Age (years) | 41.4 | 40.0 | 0.16 |

| Any Training/Degree after HS | 46 (53%) | 61 (37%) | 0.02* |

| Married or has domestic partner | 27 (31%) | 38 (23%) | 0.23 |

P-value < 0.05 is considered to be statistically significant.

Transition Readiness

Teen responses to transition readiness questions varied (Figure 1). On average, teens achieved an overall mean score across both items on the readiness for talking with providers scale of 4.11 (SD 0.95). Using our definition of “readiness” as scoring a 5 on both sub-scale items, 35% (n=87) of teens in this sample reached readiness for talking with providers, and were defined as ‘Ready Teens’. On the managing daily activities scale, the overall mean score across all 3 items was slightly lower (4.0, SD 1.00), and few teens reached “readiness” by scoring a 5 on all three sub-scale items (19.5%, n=49). We analyzed associations between readiness and our demographic and outcome variables using only Ready Teens as defined by the talking with providers subscale.

Associations with Perceived Responsibility

Overall, caregivers rated their teens as less independent in their asthma management than teens rated themselves (average sum score for Teens=18.2 vs Caregivers=14.9, p=.002). This remained true for the subgroup of Ready Teens (mean score for Teens=18.6, vs Caregivers=15.2, p=0.01), and there was a similar trend among Other Teens (mean sum score for Teens=18.0, vs Caregivers=14.7, p=0.07). However, Ready Teens and Other Teens did not significantly differ regardless of whether the responsibility score was reported by the caregivers or the teens (Table 2).

Table 2:

Teen- and Caregiver-reported Responsibility, and Associations with Teen Readiness for Talking with Providers

| Responsibility Sum Scores Mean (SD) | Caregiver report | Teen report | Spearman rho Correlation Coefficient | P-value (between reporting groups) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Sum | 14.9 (3.1) | 18.2 (3.2) | 0.191 | 0.002* |

| Ready teens | 15.2 (2.9) | 18.6 (3.2) | 0.271 | 0.01* |

| Other teens | 14.7 (3.1) | 18.0 (3.3) | 0.143 | 0.07 |

| P-value (within informant type) | 0.21 | 0.29 | --- | --- |

Associations with Teen Medication Beliefs

When asked about taking daily medications “on your own every day without a caregiver’s help,” Ready Teens were more likely than Other Teens to report wanting to and being confident they could do so. There was also a nonsignificant trend for Ready Teens to more often report that this was important (Table 3).

Ready Teens reported higher self-efficacy than Other Teens in taking daily controller medications “the way the doctor said,” on both the overall scale and for most individual items (Table 3). A sum score of this 12-item medication beliefs scale demonstrated high reliability within this sample (Cronbach α = 0.878).

When we limited our analysis to only include teens who reported currently having a prescription for a daily controller medication (n=151), these associations between readiness for talking with providers and medication beliefs remained significant (data not shown).

Associations with Medication Adherence

All teens who identified having a prescribed controller medication at baseline (n=151) reported missing a high number of medication doses over 2 weeks (mean 12.5 doses missed, SD 10.9, 52.9% of total prescribed doses). Ready Teens (n=50) reported taking more prescribed doses in the past 2 weeks than Other Teens (n=101), though this difference was not significant (54.6% vs 43.6% of total prescribed doses, p = 0.15).

Associations with Healthcare Use

Ready Teens and Other Teens did not differ in their healthcare use over the past 12 months, including the number of outpatient visits for asthma care (2.0 (SD=3.3) vs 1.5 visits (SD=3.6), p=0.28) or for any reason (4.6 (SD 5.8) vs 4.1 visits (SD 5.4), p=0.43). Both groups of teens recalled a similar number of asthma-related ED visits (0.4 (SD 1.0) vs 0.5 (SD 1.2), p=0.32), urgent care visits (0.2 (SD 0.7) vs 0.3 (SD 1.0), p=0.61), and hospitalizations (0.1 (SD 0.7) vs 0.1 (SD 0.4), p=0.71). A similar percentage of Ready (27.6%) and Other (29.9%) Teens reported any ED, urgent care, or hospital use (p=0.77).

Discussion

The TRAQ could be useful in providing structure for pediatricians’ counseling to urban adolescents and their caregivers about gradual and safe shifts in self-management responsibility prior to transferring to adult care. Typical adolescent development and the importance of teen-provider communication in asthma care both support an initial emphasis on teens’ abilities to manage conversation with providers before focusing on other executive planning and decision making tasks. In this study, we aimed to describe teen readiness in early teens aged 12–16 years, close to the age recommended for initiating transition planning [15]. We found that almost all early teens were not ready to manage daily activities (80.5%), and a majority (65%) did not endorse readiness in talking with providers, meaning that only 1/3 of urban teens with persistent asthma always answer questions and talk to the doctor or nurse when needed. Ready Teens, as defined using the talking with providers sub-scale, were not perceived by their caregivers or by themselves as being more responsible for asthma self-care than Other Teens. Ready Teens were more confident in their ability to take daily medications independently when compared to Other Teens, however they did not report significantly higher medication adherence or differences in asthma related healthcare use. Hence, while readiness to talk with providers is necessary for transitioning responsibility, it may not be sufficient during early adolescence to make an impact on health behaviors or outcomes.

Not surprisingly, mean transition readiness scores in our sample were slightly lower than those of the population sampled in the original TRAQ study (talking with providers: 4.11 vs. 4.43, managing daily activities: 4.00 vs 4.07), which included a sample of older teens (ages 14–18 years) [16]. Ready Teens were more likely than Other Teens to identify as white and were more likely to have a caregiver who completed any education after high school, similar to findings among youth with other chronic conditions revealing disparities in the development of transition readiness among teens [32,33]. Ready Teens did not differ from Other Teens in terms of disease severity.

Most caregivers and teens in this sample reported sharing responsibility for health care management tasks. Caregivers and teens perceived significant differences in the overall level of teen responsibility for chronic medication management, yet their reports of responsibility did not differ based on teen-reported readiness for talking with providers. Teens, caregivers and clinicians often disagree in their estimates of a youth’s level of readiness [34,35]; it is unknown if caregiver perceptions of teen readiness would be more or less reliable in predicting responsibility than teen perceptions. However, the lack of any association between responsibility and teen readiness suggests that the transition of responsibility for healthcare tasks may occur regardless of teens’ readiness for talking with providers.

Readiness for talking with providers was positively associated with teen beliefs about taking daily medications independently. Self-efficacy is a key precursor to using needed medications consistently, and previous studies have shown that fostering trusting relationships with youth may help to facilitate medication adherence during the teen years [23,24]. A school age child’s documented silence and lack of participation during healthcare visits may stem from a clinician’s failure to develop a therapeutic alliance [36]. When faced with teens who are reluctant to talk with providers, pediatricians should strive to clarify a teen’s expectations for health self-management, and engage them when possible. Young urban teens with asthma and their caregivers report a desire to set goals to transition responsibility for health management tasks, as well as a need for guided support in facilitating these transitions [20,21]. During visits, alone time between pediatricians and teens might help to foster direct conversations about health management.

In this study, however, among teens who reported prescribed controller medications, the teens who reported being ready to talk with providers did not have higher medication adherence compared to the Other Teens. Adherence among teens using controller medications was low (<50%). Medication responsibility within dyads of caregivers and teens with persistent asthma is not associated with knowledge about inhaled therapies [37]. Thus clinician-led transition planning needs to incorporate not only counseling to clarify teen goals for self-care and caregiver oversight of self-management tasks [38], but also enhanced medication education for early teens with asthma as well as their parents.

One limitation of this study may be its reliance on teen self-report for all outcome measures. Objective data to validate outcomes were not available due to the community-based recruitment and assessment strategy in the SB-ACT study; however, teens have been shown to reliably report on their asthma and healthcare use [39]. Social desirability bias may explain associations between readiness for talking with providers, and other medication belief scales [40]. Our analysis of medication adherence was limited to a subset of our sample who reported having a controller medication. This study did not ask all readiness questions from the full validated TRAQ tool. Future research might examine how transition readiness progresses across adolescence, how additional TRAQ domains relate to one another and health outcomes, as well as how caregivers’ perspectives compare to youth responses. Additionally, observed teen interactions with providers during visits should be compared to their self-perceived readiness for talking with providers, especially in light of known adjustments of teen behavior in response to social cues.

In summary, readiness for talking with providers in young teens is associated with their beliefs about using medications independently. Our findings indicate that maximum scores on the TRAQ talking with providers sub-scale are not a sufficient indicator of teen ability to successfully undertake health management tasks. Pediatric clinicians should use readiness assessments to guide conversations with teens and families about transition planning, but use caution in relying on self-reported readiness for talking with providers as a sufficient indicator of a teen’s ability to assume responsibility for important health behaviors. Becoming ready for adult responsibilities in self-management of asthma care is a complex process which likely progresses unevenly in different domains of behavior, consistent with typical adolescent development. Further research is needed to determine the best methods to assess and support developmentally appropriate transitions for teens with asthma.

Implications and Contribution:

Readiness for talking with providers is associated with greater perceived medication independence among urban youth with asthma, but not with increased teen responsibility or adherence. Readiness assessments support transition counseling; however, pediatricians should hesitate before interpreting this measure as a sufficient indicator of teens’ abilities to self-manage asthma care.

Acknowledgments:

Funding: This work was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute at the National Institutes of Health (Grant number R18 HL116244); the University of Rochester Pediatric Primary Care Training Program National Research Service Award (Grant number T32HP12002–28-00). Neither funding source had a role in the study design, collection, analysis or interpretation of the data, writing the manuscript, or the decision to submit the article for publication.

Abbreviations:

- TRAQ

Transition Readiness Assessment Questionnaire

- ED

Emergency department

- SB-ACT

School-based Asthma Care for Teens

- NHLBI

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute

- SD

Standard deviation

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest/Disclosure Statement:

All coauthors confirm that there are no known conflicts of interest associated with this publication and there has been no significant financial support for this work that could have influenced its outcome. We confirm that the manuscript has been read and approved by all named authors and that there are no other persons who satisfied the criteria for authorship but are not listed. We further confirm that the order of authors listed in the manuscript has been approved by all of us.

We confirm that we have given due consideration to the protection of intellectual property associated with this work and that there are no impediments to publication, including the timing of publication, with respect to intellectual property. In so doing we confirm that we have followed the regulations of our institutions concerning intellectual property. The work described has not been published previously, except in the form of the abstracts listed below. It is not under consideration for publication elsewhere, and if accepted, it will not be published elsewhere including electronically in the same form, in English or in any other language, without the written consent of the copyright-holder. We further confirm that any aspect of the work covered in this manuscript that has involved either experimental animals or human patients has been conducted with the ethical approval of all relevant bodies and that such approvals are acknowledged within the manuscript.

We understand that the Corresponding Author is the sole contact for the Editorial process (including Editorial Manager and direct communications with the office). She is responsible for communicating with the other authors about progress, submissions of revisions and final approval of proofs. We confirm that we have provided a current, correct email address which is accessible by the Corresponding Author and which has been configured to accept email from Marybeth_Jones@URMC.Rochester.edu.

Previous presentations:

Jones M, Frey S, Riekert K, Fagnano M, Halterman J. Transition Readiness in Youth with Asthma: Associations with Disease Self-Management. Pediatric Academic Societies (PAS) Meeting, Baltimore, MD, May 2016.

Jones M, Frey S, Riekert K, Fagnano M, Halterman J. Transition Readiness in Youth with Asthma: Associations with Disease Self-Management. APA Region II/III Meeting, New York, NY, March 2016.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Shaw TM, Delaet DE. Transition of adolescents to young adulthood for vulnerable populations. Pediatr Rev. 2010;31(12):497–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tuchman L, Slap G, Britto M. Transition to adult care: Experiences and expectations of adolescents with a chronic illness. Child Care Health Dev. 2008;34(5):557–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nakhla M, Daneman D, To T, et al. Transition to adult care for youths with diabetes mellitus: Findings from a universal health care system. Pediatrics. 2009;124(6):e1134–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lotstein DS, Ghandour R, Cash A, et al. Planning for health care transitions: Results from the 2005–2006 National Survey of Children With Special Health Care Needs. Pediatric2s. 2009. January;123(1):e145–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grootens-Wiegers P, Hein IM, van den Broek JM, de Vries MC. Medical decisionmaking in children and adolescents: developmental and neuroscientific aspects. BMC Pediatrics. 2017;17:120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.American Academy of Pediatrics; American Academy of Family Physicians; American College of Physicians-American Society of Internal Medicine. A consensus statement on health care transitions for young adults with special health care needs. Pediatrics. 2002;110:1304–1306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Akinbami LJ, Moorman JE, Bailey C, et al. Trends in asthma prevalence, health care use, and mortality in the United States, 2001–2010. NCHS Data Brief. 2012;(94)(94):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Orrell-Valente JK, Jarlsberg LG, Hill LG, Cabana MD. At what age do children start taking daily asthma medicines on their own? Pediatrics. 2008;122(6):e1186–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Winkelstein ML, Huss K, Butz A, et al. Factors associated with medication selfadministration in children with asthma. Clin Pediatr. 2000;39(6):337–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yinusa-Nyahkoon LS, Cohn ES, Cortes DE, Bokhour BG. Ecological barriers and social forces in childhood asthma management: Examining routines of African American families living in the inner city. J Asthma. 2010;47(7):701–710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Greenley RN, Josie KL, Drotar D. Perceived involvement in condition management among inner-city youth with asthma and their primary caregivers. J Asthma. 2006;43(9):687–693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McQuaid EL, Kopel SJ, Klein RB, Fritz GK. Medication adherence in pediatric asthma: Reasoning, responsibility, and behavior. J Pediatr Psychol. 2003;28(5):323–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Munzenberger P, Secord E, Thomas R. Relationship between patient, caregiver, and asthma characteristics, responsibility for management, and indicators of asthma control within an urban clinic. J Asthma. 2010;47(1):41–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Walders N, Drotar D, Kercsmar C. The allocation of family responsibility for asthma management tasks in African-American adolescents. J Asthma. 2000;37(1):89–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cooley WC, Sagerman PJ, Transitions Clinical Report Authoring Group, et al. Supporting the health care transition from adolescence to adulthood in the medical home. Pediatrics. 2011;128(1):182–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wood DL, Sawicki GS, Miller MD, et al. The transition readiness assessment questionnaire (TRAQ): Its factor structure, reliability, and validity. Acad Pediatr. 2014;14(4):415–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bender BG. Overcoming barriers to nonadherence in asthma treatment. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002;109(6 Suppl): S554–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van Staa A, van der Stege HA, Jedeloo S, et al. Readiness to transfer to adult care of adolescents with chronic conditions: Exploration of associated factors. J Adolesc Health. 2011;48(3):295–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fredericks EM, Dore-Stites D, Well A, et al. Assessment of transition readiness skills and adherence in pediatric liver transplant recipients. Pediatr Transplant. 2010;14(8):944–953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gibson-Scipio W, Krouse HJ. Goals, beliefs, and concerns of urban caregivers of middle and older adolescents with asthma. J Asthma. 2013;50(3):242–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gibson-Scipio W, Gourdin D, Krouse HJ. Asthma Self-Management Goals, Beliefs and Behaviors of Urban African American Adolescents Prior to Transitioning to Adult Health Care. J Pediatr Nurs. 2015;30(6):e53–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wolf MS, Wilson EA, Rapp DN, et al. Literacy and learning in health care. Pediatrics. 2009. November;124 Suppl 3:S275–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Young HN, Len-Rios ME, Brown R, et al. How does patient-provider communication influence adherence to asthma medications? Patient Educ Couns. 2017. April;100(4):696–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ahmad A, Sorensen K. Enabling and hindering factors influencing adherence to asthma treatment among adolescents: A systematic literature review. J Asthma. 2016. October;53(8):862–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carpenter DM, Ayala GX, Williams DM, et al. The relationship between patientprovider communication and quality of life for children with asthma and their caregivers. J Asthma. 2013. September;50(7):791–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Banasiak NC. Childhood asthma practice guideline part three: Update of the 2007 national guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of asthma. J Pediatr Health Care. 2009;23(1):59–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wade SL, Islam S, Holden G, et al. Division of responsibility for asthma management tasks between caregivers and children in the inner city. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 1999;20(2):93–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vesco AT, Anderson BJ, Laffel LM, et al. Responsibility sharing between adolescents with type 1 diabetes and their caregivers: Importance of adolescent perceptions on diabetes management and control. J Pediatr Psychol. 2010;35(10):1168–1177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Anderson BJ, Auslander WF, Jung KC, et al. Assessing family sharing of diabetes responsibilities. J Pediatr Psychol. 1990;15(4):477–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Riekert KA, Borrelli B, Bilderback A, Rand CS. The development of a motivational interviewing intervention to promote medication adherence among inner-city, AfricanAmerican adolescents with asthma. Patient Educ Counc. 2011;82(1):117–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Halterman JS, Riekert K, Bayer A, et al. A pilot study to enhance preventive asthma care among urban adolescents with asthma. J Asthma. 2011;48(5):523–530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Javalkar K, Johnson M, Kshirsagar AV, et al. Ecological factors predict transition Readiness/Self-management in youth with chronic conditions. J Adolesc Health. 2016;58(1):40–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fenton N, Ferris M, Ko Z, et al. The relationship of health care transition readiness to disease-related characteristics, psychosocial factors, and health care outcomes: Preliminary findings in adolescents with chronic kidney disease. J Pediatr Rehab Med 2015;8(1):13–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Knapp C, Huang IC, Hinojosa M, et al. Assessing the congruence of transition preparedness as reported by parents and their adolescents with special health care needs. Matern Child Health J. 2013;17(2):352–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sawicki GS, Kelemen S, Weitzman ER. Ready, set, stop: Mismatch between selfcare beliefs, transition readiness skills, and transition planning among adolescents, young adults, and parents. Clin Pediatr. 2014;53(11):1062–1068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Polk S, Horwitz R, Longway S, et al. Surveillance or Engagement: Children’s Conflicts During Health Maintenance Visits. Academic Pediatrics. 2017;17(7):739–746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Frey SM, Jones MR, Goldstein N, et al. Knowledge of Inhaled Therapy and Responsibility for Asthma Management Among Young Teens With Uncontrolled Persistent Asthma. Acad Pediatr. 2018. April;18(3):317–323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Beacham BL, Deatrick JA. Health care autonomy in children with chronic conditions: Implications for self-care and family management. Nurs Clin North Am. 2013;48(2):305317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Houle CR, Joseph CL, Caldwell CH, et al. Congruence between urban adolescent and caregiver responses to questions about the adolescent’s asthma. J Urban Health. 2011. February;88(1):30–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Logan DE, Claar RL, Scharff L. Social desirability response bias and self-report of psychological distress in pediatric chronic pain patients. Pain. 2008;136(3):366–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]