Abstract

The aims of the current review were to compare the efficacy of monotherapy with bendroflumethiazide vs. indapamide on mortality, cardiovascular outcomes, blood pressure, need for intensification of treatment and treatment withdrawal. Two authors independently screened the results of a literature search, assessed the risk of bias and extracted relevant data. Randomized clinical trials of hypertensive patients of at least a 1‐year duration were included. When there was disagreement, a third reviewer was consulted. Risk ratio (RR) and mean differences were used as measures of effect. Two trials comparing bendroflumethiazide against placebo, one comparing indapamide with placebo and three of short duration directly comparing indapamide and Bendroflumethiazide, were included. No statistically significant difference was found between indapamide and bendroflumethiazide for all deaths [RR 0.82; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.57, 1.18], cardiovascular deaths (RR 0.82; 95% CI 0.55, 1.20), noncardiovascular deaths (0.81; 95% CI 0.54, 1.22), coronary events (RR 0.73; 95% CI 0.30, 1.79) or all cardiovascular events (RR 0.89; 95% CI 0.67, 1.18). Indapamide performed worse for stroke (RR 2.21; 95% CI 1.19, 4.11), even though a reduction in RR compared with placebo was observed in both groups. There was no statistically or clinically significant difference between indapamide and bendroflumethiazide in blood pressure reduction (mean absolute difference <1 mmHg). The present review highlights a lack of studies to answer the review question but also a lack of evidence of superiority of one drug over the other. Therefore, there is a clear need for new studies directly comparing the effect of these drugs on the outcomes of interest.

Keywords: bendroflumethiazide, cardiovascular, hypertension, indapamide, mortality, systematic review, thiazide diuretics

Introduction

High blood pressure (BP) is one of the most important preventable causes of premature cardiovascular morbidity and mortality worldwide. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that the global prevalence in adults aged 25 years and over is around 40%. Raised BP is estimated to cause 7.5 million deaths annually, about 12.8% of the total of all deaths. Moreover, hypertension increases the risk of developing coronary artery disease, stroke, heart failure, peripheral vascular disease, vision loss, chronic kidney disease, cognitive decline and early death 1. Treating hypertension reduces cardiovascular disease risk and the risk of death from cardiovascular causes 2. Thiazide diuretics are a class of antihypertensive medications launched in the 1950s and have long demonstrated effectiveness in reducing BP and the risk of cardiovascular events 3. A recent Cochrane systematic review of first‐line drugs for hypertension concluded that ʻlow‐dose thiazides should be the first‐choice drug in most patients with elevated blood pressureʼ due to the evidence of reduced mortality and morbidity such as stroke, heart attack and heart failure 4. Usually prescribed as first‐ or second‐line drugs, alone or combined with drugs from other classes 5, 6, diuretics are classified into thiazides and thiazide‐like diuretics 7. The most recent National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidelines for the management of hypertension published in 2011 8 and evidence updated in 2013 9 specified that if ʻ … a diuretic is requiredʼ, ʻ… a thiazide‐like diuretic, such as chlorthalidone (12.5–25 mg once daily) or indapamide (2.5 mg once daily)ʼ should be chosen … ʻin preference to a conventional thiazide diuretic such as bendroflumethiazide or hydrochlorothiazideʼ. However, there has been debate around whether these guidelines were supported by evidence 10. The existing systematic reviews and meta‐analyses have focused on the efficacy of blood‐pressure lowering 5, 11, 12, 13, 14 rather than long‐term outcomes 15, 16, 17.

The primary objective of the present review was to compare the efficacy of monotherapy with the thiazide diuretic bendroflumethiazide vs. the thiazide‐like diuretic indapamide as a first line in the treatment of primary hypertension on mortality and cardiovascular outcomes. The secondary objective was to compare the effect of these two monotherapies on secondary outcomes such as BP lowering, the need for intensification of treatment and medication discontinuation.

Methods

The protocol for the present review was registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) 18, registration number CRD42017067109. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐analyses (PRISMA) guidelines 19 were followed.

Literature search strategy

A literature search was performed from 2008 to April 2018 using the search strategy of Wright and Musini (2009) 4 and the NICE guidelines update 2013 9, modified to focus on indapamide and bendroflumethiazide. MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL (using NHS Education for Scotland's The Knowledge Network), the Cochrane Library [Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), Cochrane Methodology Register], Health Technology Assessment Database, ClinicalTrials.gov, EU Clinical Trials Register and Google Scholar were searched. In addition, two high‐impact peer‐reviewed journals that were appropriate for the review, the British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology and European Heart Journal, were hand searched for the past 5 years. References lists from the relevant published papers were also searched. to help to identify additional trials. Only publications in the English language were included.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Randomized controlled trials of adults with primary hypertension with at least one year of follow‐up were included. Studies reporting monotherapy with bendroflumethiazide or indapamide were included when the comparator group was either a placebo or another drug. Studies including supplemental medication with other drug classes as stepped‐care therapy could also be included. It was assumed that these supplemental drugs did not systematically interact to affect the occurrence of the outcomes studied.

Data extraction

Two reviewers independently screened the title and the abstract of each study meeting the inclusion criteria. If disagreements occurred between the two reviewers, a third reviewer was consulted. For eligible studies, data extraction was performed by two reviewers independently, using a specially designed data collection form. Disagreements were resolved after discussion with two other reviewers. The values of mean change from baseline in BP at the 1‐year follow‐up and the standard deviation were obtained from Wright and Musini (2009) 4. Authors of studies were contacted, when the required information was clearly available but not reported in the manuscript.

Outcomes

The primary outcomes considered were total mortality and cardiovascular outcomes such as stroke, myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure and cardiovascular death. The secondary outcomes were adverse events, need for intensification of treatment, withdrawals and BP lowering. Only published information was used.

Risk of bias in the included studies

The Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias 20 was used to assess quality in the included studies. The items of methodological quality assessed were: method used to randomize participants; whether randomization was completed in an appropriate and blinded manner; whether participants, providers, outcome assessors or a combination of these were blinded to the assigned therapy; whether the control group received a placebo or no treatment; the percentage of participants who did not complete follow‐up (drop‐outs); the percentage of participants not on assigned active or placebo therapy at study completion; and the selective reporting of outcomes. Two reviewers conducted the assessment independently. If disagreement occurred, a third reviewer was consulted. The results were compared with those reported by Musini et al. 14, 21.

Data analysis

Network meta‐analysis was conducted using STATA 15 for Windows (2017). All analyses were by intent‐to‐treat. Indirect comparisons were made using the indirect STATA command 22. Graphical tools 23 were used as appropriate. Evidence was graded using the approach of the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) 24 Working Group, using GRADEpro 25.

Results

Search results

The search resulted in 1878 publications (Figure 1). After the removal of duplicates and 1418 irrelevant papers, and having found an additional 26 papers by hand searching the references of published papers, 128 full‐text papers were considered further. The reasons for exclusion of 112 articles are shown in Figure 1. A total of 52 reviews, meta‐analyses, commentaries, editorial and protocols were found, and a further 60 articles contained information from 53 individual studies. The most common reason for study exclusion was duration of treatment (<1 year) (n = 22) followed by the use of combination therapy (n = 13) and studies not being trials of hypertension (n = 12). Other excluded studies were observational studies (n = 3), single‐arm trials (n = 3), studies that did not include bendroflumethiazide or indapamide (n = 5) and studies using any thiazide diuretic rather than specifically bendroflumethiazide (n = 4).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram

Three further studies [the Hypertension in the Very Elderly Trial (HYVET) pilot 26; Diuretics in the Management of Essential Hypertension (DIME) study 27 and Heart Attack Primary Prevention in Hypertension (HAPPHY) trial 28 were excluded because the participating centres within each study were given the choice of type of thiazide diuretics depending on drug availability, but the published manuscripts did not report the results by type of drug. When contacted, the authors or funders either did not reply, could not provide the information required or could not make the original datasets available for data analysis. Therefore, three studies reported in 17 papers were included in the present review 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44.

As no studies of a direct comparison between indapamide and bendroflumethiazide for long‐term outcome were found, we included three studies of short‐term follow‐up with BP as an outcome 45, 46, 47.

Description of the included studies and study participants

Two studies were conducted in the UK 29, 31 and one study was a multicentre clinical trial 39 (Table 1). They were published between 1973 and 2008. Study size ranged from 116 to 17 354 participants, and females comprised between 48% and 60%. Two studies included participants of mean age around 50–55 years, while in one study 39 the mean age of participants was 84 years. In two studies, participants were followed up annually for 5 years 31, 39 and one study followed the participants up to 18 months 27.

Table 1.

Description of the included studies and study participants

| First author/publication year/study name | Country | Study size | Follow‐upa | Age (years) | Sex N (%) females | Sponsorship |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Barraclough

1973 Cooperative randomized controlled trial |

UK | 116 | 6, 12, 18 months |

Mean Treatment group: men 54.4 women 55.7 Placebo: men 55.2 women 56.5 Range: 45–69 |

66 (57%) | Drugs were supplied by Glaxo Ltd, Merck Sharp and Dohme Ltd and Roche Products Ltd |

|

MRC Working Party

1985 MRC‐TMH |

UK | 17 354 | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 years |

Means: males: 51 (SD 8) females: 53 (SD 7) |

8306 (48%) |

Drugs were supplied by Duncan, Flockhart and Co Ltd, Imperial Chemical Industries Ltd, CIBA Laboratories and Merck Sharp & Dohme Ltd. Additional support was also provided by Imperial Chemical Industries Ltd and Merck Sharp and Dohme Ltd |

|

Beckett

2008 HYVET |

UK, France, Ireland, Finland, Belgium, Bulgaria, Romania, Poland, Russia, China, Australia, New Zealand, Tunisia | 3845 | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 years |

Mean 84 (SD 3) Range 80–105 |

2326 (60%) | Supported by grants from the British Heart Foundation and the Institut de Recherches Internationales Servier |

HYVET, Hypertension in the Very Elderly Trial; MRC‐TMH, Medical Research Council Therapy for Mild Hypertension study; SD, standard deviation

Follow‐up time when outcomes of interest were available

All studies had pharmaceutical industry sponsorship. Participants were recruited from a variety of sources, such as hospitals, primary care and surveys of random samples of the general population (Table 2). Mild, moderate and persistent hypertension were used as inclusion criteria, and there was variation in the method of BP measurement (Table 2). Two studies investigated bendroflumethiazide 29, 31 and one study investigated indapamide 37 (Table 3). All three trials used placebo as a comparison and one study also used propranolol 31. Doses of all medications varied, and one study 29 did not specify the dose. All studies permitted additional medication at the discretion of the physician or trial investigators (Table 3). Three short‐term outcome studies directly comparing indapamide and bendroflumethiazide are described in Appendix 4. They were conducted in 1981 45, 46 and 2006 47, each included fewer than 30 participants and the follow‐up was between 4 weeks and 16 weeks.

Table 2.

Description of studies by inclusion and exclusion criteria

| First author/publication years/study name | Population | Definition of hypertension | How baseline blood pressure was measured | Age inclusion criteria (years) | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Barraclough

1973 Cooperative randomized controlled trial |

Surveys of random samples of general population and hospital patients |

Diastolic BP 100–120 mmHg Two occasions separated by an interval of at least 2 weeks |

Garrow random zero sphygmomanometer after sitting for 5 min | 45–69 | Renal or cardiac failure or papilloedema; history of cerebrovascular accident or MI within the past 3 months; any serious or potentially fatal disease or disability that would prevent regular attendances or which contraindicated hypotensive therapy; receiving antihypertensive therapy; evidence that hypertension was secondary to a surgically remediable condition |

|

MRC Working Party

1985 MRC‐TMH |

General medical practice clinics |

DBP 90–109 mmHg and SBP <200 mmHg; Mean of 4 readings taken on 2 separate occasions and confirmed by the mean of 2 later readings |

Hawksley random zero sphygmomanometer and London School of Hygiene sphygmomanometer | 35–64 | Secondary hypertension; taking antihypertensive treatment; normally accepted indications for antihypertensive treatment (such as congestive cardiac failure present); MI or stroke within the previous 3 months; presence of angina, intermittent claudication, diabetes, gout, bronchial asthma, serious intercurrent disease, or pregnancy |

|

Beckett

2008 HYVET |

Patients |

Sustained SBP ≥160 mmHg during 2 months of placebo run‐in period; BP taken twice after sitting for 5 min and on the third visit and thereafter twice after standing for 2 min; mean of 2 sitting SBP readings taken on 2 separate occasions, 1 month apart, between 160 mmHg and 199 mmHg Standing SBP ≥140 mmHg |

Standard mercury sphygmomanometer or validated automatic device | ≥80 | Known accelerated hypertension, heart failure requiring treatment with diuretic or ACE inhibitor, renal failure (serum creatinine level >150 μmol l–1), haemorrhagic stroke in the previous 6 months, terminal illness, known secondary hypertension, gout, clinical diagnosis of dementia, contraindication to use of the trial medications (a serum potassium level of <3.5 mmol l–1 or >5.5 mmol l–1) and a requirement of nursing care, inability to stand up or walk |

ACE, angiotensin‐converting enzyme; BP, Blood pressure; DBP, diastolic BP; HYVET, Hypertension in the Very Elderly Trial; MI, myocardial infarction; MRC‐TMH, Medical Research Council Therapy for Mild Hypertension study; SBP, systolic BP

Table 3.

Description of interventions

| First author/ publication year/ study name | Indapamide | Bendroflumethiazide | Placebo | Propranolol | Additional treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Barraclough

1973 Cooperative randomized controlled trial |

– | Dose not specified | Calcium lactate | – | Bendrofluazide group: any combination with potassium supplement, methyldopa or debrisoquine (at discretion of physician) |

|

MRC Working Party

1985 MRC‐TMH |

‐ | 10 mg daily | Tablets that looked like bendrofluazide or tablets that looked like propranolol | 240 mg daily | Methyldopa or guanethidine was added if BP did not respond satisfactorily to the primary drug. If necessary, one of the primary trial drugs was used to supplement the other. Control patients whose BP rose to levels at which placebo treatment was judged unethical were transferred to the corresponding active drug. For BP >110 mmHg diastolic and >200 mmHg systolic in active treatment group, additional treatment used on discretion of physician |

|

Beckett

2008 HYVET |

1.5 mg sustained release daily | ‐ | Matching placebo | ‐ | At each visit (or at the discretion of the investigator), if needed to reach the target BP, perindopril (2 mg or 4 mg) or matching placebo could be added |

BP, blood pressure; HYVET, Hypertension in the Very Elderly Trial; MRC‐TMH, Medical Research Council Therapy for Mild Hypertension study

Definition of outcome

Table 4 shows the availability of data on primary and secondary outcomes. Two trials 31, 39 had all primary outcomes data available, but the cause of death was missing for two participants in the placebo group in Barraclough et al. 29 All studies reported withdrawals for medical reasons; however, the reported reasons differed between studies. For example, in the study by Barraclough et al. 29, participants in the placebo group with a diastolic BP >130 mmHg were withdrawn by design. There were insufficient data for other secondary outcomes, such as additional medication, but data on diastolic BP were reported in all studies and information on systolic BP was available in two studies 31, 39.

Table 4.

Availability of data on outcomes

| Outcome | First author/publication year/study name | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Barraclough 1973; Cooperative randomized controlled trial | MRC Working Party 1985; MRC‐TMH | Beckett 2008; HYVET | |

| Timing of outcome | 18 months | Mean 5.5 years | Median follow‐up 1.8 years |

| All deaths | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Cardiovascular deaths | Yes (cause of death was unknown for some of the participants) | Yes | Yes (death from fatal stroke, fatal myocardial infarction, fatal heart failure and sudden death) |

| Noncardiovascular deaths | Yes (cause of death was unknown for some of the participants) | Yes | Yes |

| Stroke | Not reported (assumed 0) | Yes (fatal or nonfatal) | Yes (fatal or nonfatal) |

| Myocardial infarction | Yes (fatal or nonfatal) | Yes (coronary events including sudden death thought to be due to a coronary cause, death known to be due to myocardial infarction, and nonfatal myocardial infarction) | Yes (fatal or nonfatal) |

| Other cardiovascular events |

Yes (pulmonary embolism; cardiac failure) |

Yes (other cardiovascular events, including deaths due to hypertension (ICD 400–404) and to rupture or dissection of an aortic aneurysm; death from any other cause) | Yes |

| Any cardiovascular events | Yes | Yes (not necessarily equal to the total of strokes plus coronary events because it also includes ʻother relevant deathsʼ and deaths due to other cardiovascular causes such as ruptured aneurysms) | Yes (any cardiovascular event was defined as death from cardiovascular causes or stroke, myocardial infarction, or heart failure) |

| Withdrawals for medical reasons a | Yes (participants from the control group with diastolic blood pressure >130 mmHg were withdrawn by design; geriatric hospital admission in the bendroflumethiazide group) | Yes (impaired glucose tolerance; gout; impotence, Raynaud's phenomenon; skin disorder; dyspnoea; lethargy; nausea, dizziness, headache; blood pressure at levels requiring change of treatment) | Yes (were withdrawn by investigator; had a protocol withdrawal event and no open follow‐up) |

| Withdrawals for nonmedical reasons | Yes (defaulted or noncooperative) | No | Yes (centres closed by data monitoring committee; had other administrative reasons; declined to participate; lost to follow‐up) |

| Additional medication | No additional medication in control group by design; all participants in the active group had additional medication | Not reported for placebo | Yes |

| Blood pressure | Yes | Yes | Yes |

ICD, International Classification of Diseases; MRC‐TMH, Medical Research Council Therapy for Mild Hypertension study

Not including primary outcomes

Risk of bias in the included studies

Table 5 shows the results of the assessment of risk of bias in each of the included studies. Two studies 29, 31 did not satisfy the criteria for blinding and data completeness, two studies 29, 39 were not free of selective reporting, one trial 29 had inadequate allocation concealment and in one study 39 random sequence generation was unclear. Appendix 5 shows results of the assessment of risk of bias in each of the three short‐term outcome studies directly comparing indapamide and bendroflumethiazide. All three studies had a high risk of bias.

Table 5.

Assessment of risk of bias

| First author/publication year/study name | Random sequence generation | Allocation concealment | Blinding of participants and personnel | Blinding of outcome assessment | Incomplete outcome data | Free from selective reporting | Other sources of bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Barraclough

1973 Cooperative randomized controlled trial |

+ | − | − | + | − | − | ? |

|

MRC Working Party

1985 MRC‐TMH |

+ | + | − | + | − | + | ? |

|

Beckett

2008 HYVET |

? | + | + | + | + | − | ? |

HYVET, Hypertension in the Very Elderly Trial; MRC‐TMH, Medical Research Council Therapy for Mild Hypertension study

Effects of interventions

Appendix 1 shows the data extracted for each outcome and effect of intervention for each study compared with placebo, and Appendix 2 shows a forest plot by outcome for each study. Appendix 3 illustrates the network pattern, and Appendix 1 presents the results of the indirect comparison of indapamide vs. bendroflumethiazide. There was no statistically significant difference between indapamide and bendroflumethiazide in all deaths [indirect risk ratio (RR) 0.82; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.57, 1.18], cardiovascular death (indirect RR 0.82; 95% CI 0.55, 1.20), noncardiovascular death (indirect RR 0.81; 95% CI 0.54, 1.22), coronary events (indirect RR 0.73; 95% CI 0.30, 1.79) or all cardiovascular events (indirect RR 0.89; 95% CI 0.67, 1.18). However, whereas indapamide showed a reduction in risk for these outcomes compared with placebo, bendroflumethiazide did not show a difference compared with placebo for these outcomes, except for all cardiovascular events combined (Appendices 1 and 2). Indapamide performed worse for the outcome of stroke and withdrawals for medical reasons (indirect RR 2.21; 95% CI 1.19, 4.11, and RR 1.23; 95% CI 1.07, 1.40, respectively). However, there was a reduction in RR compared with placebo in both of these groups, except for withdrawals for medical reasons in the indapamide group (RR 0.98; 95% CI 0.89, 1.07) (Appendices 1 and 2).

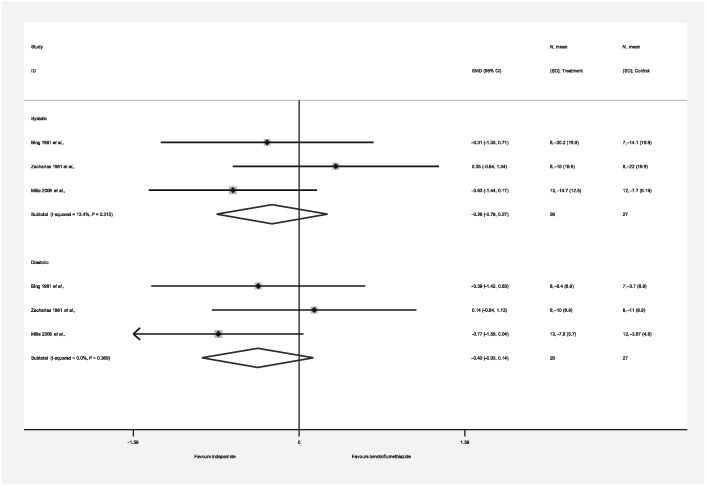

Significant long‐term reductions in BP from baseline, in comparison with placebo, were reported in all studies. There were no statistically or clinically significant differences between indapamide and bendroflumethiazide in systolic and diastolic BP (mean difference in reduction from baseline 0.94 mmHg; 95% CI –1.45, 2.25, and 0.88 mmHg; 95% CI –0.19, 1.95, respectively) (Appendices 1 and 2). Appendix 6 shows data extracted for systolic and diastolic BP for each study of the direct comparison between indapamide and bendroflumethiazide, and Appendix 7 shows a forest plot and summary effects. There was no statistically or clinically significant difference between indapamide and bendroflumethiazide in systolic and diastolic BP (mean difference –0.26 mmHg; 95% CI –0.79, 0.27, and –0.40 mmHg; 95% CI –0.93, 0.14, respectively) (Appendix 7).

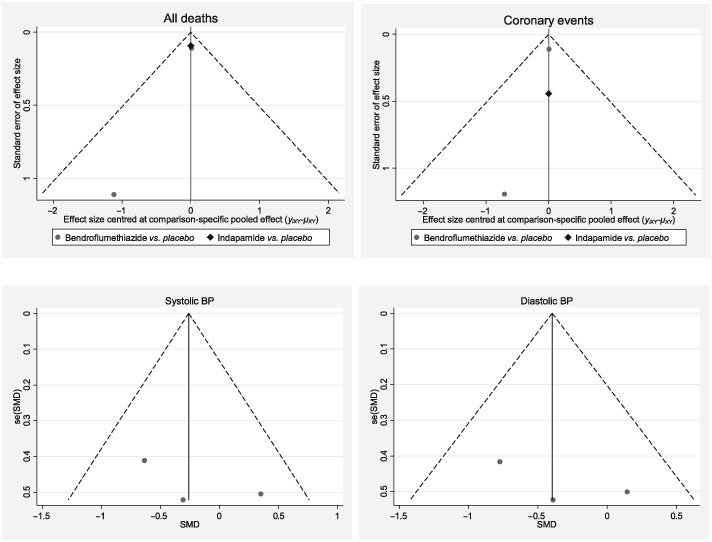

There were only three studies included in the meta‐analysis of long‐term outcomes, and three studies of short‐term BP reduction. Appendix 8 shows funnel plots for these studies. There did not appear to be any evidence of publication bias for short‐term outcomes as the figures for both types of BP were symmetrical. However, this was less clear in the case of indirect comparisons.

Overall evidence

Evidence was graded either as moderate or low (Tables 6 and 7).

Table 6.

Grading the evidence: primary outcomes

| Quality assessment | № of patients | Relative effect | Quality | Importance | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| № of studies | Study design | Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other considerations | Indapamide | Bendroflumethiazide | (95% CI) | ||

| All deaths (follow‐up: range 1.5–5.5 years) | |||||||||||

| 3 | Randomized trials | Not serious | Not serious | Very serious | Not serious | None | 1933 | 4355 | RR 0.82 (0.57, 1.18) | ⨁⨁◯◯ LOW | CRITICAL |

| Cardiovascular deaths (follow‐up: range 2–5.5 years) | |||||||||||

| 2 | Randomized trials | Not serious | Not serious | Very serious | Not serious | None | 1933 | 4297 | RR 0.82 (0.56, 1.20) | ⨁⨁◯◯ LOW | CRITICAL |

| Noncardiovascular deaths (follow‐up: range 2–5.5 years) | |||||||||||

| 2 | Randomized trials | Not serious | Not serious | Very serious | Not serious | None | 1933 | 4297 | RR 0.81 (0.54, 1.22) | ⨁⨁◯◯ LOW | CRITICAL |

| Stroke (follow‐up: range 2–5.5 years) | |||||||||||

| 2 | Randomized trials | Not serious | Not serious | Very serious | Not serious | None | 1933 | 4297 | RR 2.21 (1.19, 4.11) | ⨁⨁◯◯ LOW | CRITICAL |

| Coronary events (follow‐up: range 1.5–5.5 years) | |||||||||||

| 3 | Randomized trials | Not serious | Not serious | Very serious | Not serious | None | 1933 | 4355 | RR 0.73 (0.30, 1.79) | ⨁⨁◯◯ LOW | CRITICAL |

| All cardiovascular events (follow‐up: range 2–5.5 years) | |||||||||||

| 2 | Randomized trials | Not serious | Not serious | Very serious | Not serious | None | 1933 | 4297 | RR 0.89 (0.67, 1.18) | ⨁⨁◯◯ LOW | IMPORTANT |

CI, confidence interval; RR, risk ratio

Table 7.

Grading the evidence: secondary outcomes

| Quality assessment | № of patients | Absolute effect | Quality | Importance | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| № of studies | Study design | Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other considerations | Indapamide | Bendroflumethiazide | (95% CI) | ||

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) (follow‐up: 1 year) | |||||||||||

| 2 | Randomized trials | Not serious | Not serious | Serious | Not serious | None | 1933 | 4297 | 0.94 (−1.45, 2.25) | ⨁⨁⨁◯ MODERATE | CRITICAL |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) (follow‐up: 1 year) | |||||||||||

| 3 | Randomized trials | Not serious | Not serious | Serious | Not serious | None | 1933 | 4355 | 0.88 (−0.19, 1.95) | ⨁⨁⨁◯ MODERATE | CRITICAL |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) (follow‐up: range 12–24 weeks) | |||||||||||

| 3 | Randomized trials | Serious | Not serious | Not serious | Serious | None | 29 | 27 | −0.26 (−0.79, 0.27) | ⨁⨁◯◯ LOW | IMPORTANT |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) (follow‐up: range 12–24 weeks) | |||||||||||

| 3 | Randomized trials | Serious | Not serious | Not serious | Serious | None | 29 | 27 | −0.40 (−0.93, 0.14) | ⨁⨁◯◯ LOW | IMPORTANT |

CI, confidence interval

Discussion

Bendroflumethiazide and indapamide are the most frequently prescribed diuretics for hypertension treatment in the UK 48. This is the first systematic review directly to compare these agents. It demonstrates the lack of evidence on the comparative effectiveness of these drugs on mortality and cardiovascular outcomes such as stroke and myocardial infarction, as only three eligible studies were available for analysis of these long‐term outcomes, and none were studies of direct comparison. Three small studies of direct comparison were prone to bias, with low overall GRADE evidence.

A meta‐analysis of thiazide‐like diuretics vs. thiazide‐type diuretics which included 12 studies comparing indapamide or chlorthalidone vs. hydrochlorothiazide suggested that thiazide‐like diuretics further reduce both systolic and diastolic BP (mean −5.59 mmHg; 95% CI –5.69, −5.49, and –1.98; 95% CI –3.29, −0.66, respectively) 49.

A network meta‐analyses that aimed to summarize the evidence on the efficacy of antihypertensive therapies 16 included 42 clinical trials randomized to seven types of treatment. Treatments considered were placebo, untreated or usual care: low‐dose diuretics, β‐blockers, angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors; angiotensin II receptor blockers, calcium channel blockers and α‐blockers. The latter meta‐analysis showed that low‐dose diuretics were the most effective first‐line treatment for preventing the occurrence of cardiovascular disease morbidity and mortality compared with other treatments. However, the low‐dose diuretic therapies were usually the equivalent of 12.5–25 mg per day of chlorthalidone or hydrochlorothiazide.

Although the present review included only a limited number of studies, its strengths included having a predefined protocol and the fact that it followed current guidelines and statistical techniques. Every effort was made to find relevant studies, and multiple sources were searched. The search strategy was similar to those strategies used in a previous systematic review 4 and clinical guidelines update 9. To minimize potential errors, the selection of studies and data extraction were performed independently by two reviewers, and the data were also compared with those extracted in other systematic reviews 14, 21.

Nevertheless, there were several methodological limitations. We restricted our search to publications in the English language, which could potentially have influenced the results. However, in other countries, other types of thiazide, such as chlorthalidone, metolazone or hydrochlorothiazide, are mostly used 50, 51, 52, 53. Although one study 39 included in the present review was international, all of the other studies were conducted only in the UK 29, 31.

We formally evaluated publication bias, but the number of studies included in the present review was small. It is possible that some studies, especially earlier studies, were never published. We searched clinical trials registers, as well as databases of published literature, but were unable to find any further studies. Although three studies eligible for inclusion had the required data available, we could not get access to the original data and therefore could not include them in the present review.

There was substantial heterogeneity between the included studies. Firstly, hypertension was defined differently between the studies. For example, the HYVET study 39 considered systolic BP, whereas the others 29, 31 considered diastolic BP.

Studies also measured BP differently – that is, supine, sitting or standing, and clinic or monitoring at home; or as a one‐off measurement or average of measurements from several occasions.

Inclusion criteria were different between the studies. In the HYVET study 39, patients had been previously treated for hypertension but had suspended their treatment for at least 2 months prior to entry to the study, whereas in the other two trials 29, 31 the enrolled participants had not taken any medication for hypertension prior to enrolment.

Participants were recruited from various sources, such as the general population, medical practices and hospitals; therefore, it was difficult to judge the overall generalizability of the findings.

One study 29 had a follow‐up of 18 months, whereas two other studies had a long‐term follow‐up (over 5 years). However, the results of a 2‐year follow‐up were also available for the HYVET study 37, and of a 5.5‐year follow for the Medical Research Council Therapy for Mild Hypertension (MRC‐TMH) study 31. In addition, it was possible to estimate the BP results for a 1‐year follow up from the graphs published in all three papers. Dose information was not available in one study 29.

Another potential limitation was the fact that some of the trials included a thiazide combined with another drug. For example, in the HYVET study 39, at the 2‐year follow‐up, 73.4% of the active group received both indapamide and perindopril.

Outcome data were not always complete or were heterogeneous. For example, cause of death was missing for some participants in the study by Barraclough et al. 29. The latter study also withdrew controls with a diastolic BP >130 mmHg but not patients in the active group. There were different reasons for medical withdrawals, as well as inconsistent reports of nonmedical withdrawals, between studies. Additional medication was insufficiently reported to allow meaningful data analysis. One study 29 did not report data on systolic BP. Data for some parameters, such as standard deviation, were not always available, especially in the earlier studies, and therefore assumptions were made using baseline estimates or estimates from other studies. This could potentially have introduced bias to the overall estimates.

The quality of the included studies varied – for example, two trials (one long‐term 39 and one short‐term 47) were double blind. Two studies were large 31, 39, whereas the study by Barraclough et al. 29 and three studies of direct comparison were relatively small (fewer than 30 participants).

All long‐term studies and one short‐term study reported some form of pharmaceutical industry support. However, although it is widely agreed that it is important to know the provenance of funding for a study, it has been argued that the Cochrane risk of bias tool should not include funding source as a standard item 54. Conflicts of interest in industry‐funded trials are likely to manifest in selective reporting or a problematic choice of comparator. To counteract the former, we searched trial registers and, where possible, accessed study protocols. To counteract the latter, it has been suggested that network meta‐analysis can be used for head‐to‐head drug comparisons when placebo comparators have been used 54, and this was used in the present review.

There were several potential methodological problems associated with indirect comparisons 55. Although the combined sample size of the included studies was large, the number of studies available for the present review was small. Methods for estimating the effective number of trials and effective sample size have been proposed which take into account the trial count ratio 55. For a trial count ratio of 1:2 (e.g. in the present review, there were two studies of bendroflumethiazide and one study of indapamide), the indirect comparison would require six trials (ratio 2:4) to produce a precision equivalent to one head‐to‐head trial 56.

We did not combine indirect and direct evidence, as the direct evidence came from small short‐term trials reporting BP only, whereas the primary aim of the study was to compare long‐term cardiovascular outcomes. However, it was reassuring that both direct and indirect estimates of the drug effects on BP were similar. In addition, reduced BP seemed to stabilize after 1 year of follow‐up 31, 39.

We compared bendroflumethiazide and indapamide indirectly via placebo. The composition of the placebo was included in only one trial 29, whereas the other studies stated that placebo was essentially a ʻlook‐alikeʼ version of the active treatment. Although there were studies of direct comparisons of hydrochlorothiazide vs. indapamide and hydrochlorothiazide vs. placebo 4, 49, they were not included because these drugs are rarely used in the UK 48.

One of the requirements of an indirect meta‐analysis is that the population groups are comparable. Two studies in the present review involved participants below the age of 80 years 29, 31, and one study 39 was conducted in patients aged over 80 years. One might argue that these groups are not comparable. Is there any evidence of a differential action of these drugs in different age groups? A systematic review of pharmacotherapy for hypertension in adults aged 18–59 years 14 included seven studies and 17 327 participants, but the MRC‐TMH trial 31, which was also included in the current review, contributed 84% of the population considered. The review 14 demonstrated a small absolute effect in reducing cardiovascular mortality and morbidity, no reduction in all‐cause mortality or coronary events, and a lack of good evidence on withdrawal due to adverse events.

However, a systematic review of pharmacotherapy for hypertension in the elderly 21 included 15 trials and 24 055 participants aged ≥60 years with moderate to severe hypertension. It showed a reduction in all‐cause mortality and cardiovascular morbidity and mortality, but the decrease in all‐cause mortality was limited to persons aged 60–80 years. The process of grading the evidence is subjective, and the issue of grade inflation has been highlighted previously 57. In the present review, evidence was graded either as low or moderate, and grading was done by author consensus, to minimize potential overestimation.

Guidance for policy makers in interpreting indirect treatment comparisons and network meta‐analysis is available 58, 59; however, our results are unlikely to be used for clinical decision‐making owing to a deficiency of evidence.

In the present systematic review, we determined, from a small number of studies, that there is limited information on direct comparisons between indapamide and Bendroflumethiazide, and that the evidence of superiority of indapamide over bendroflumethiazide in long‐term outcomes is inconclusive. Therefore, there is a clear need for large clinical trials directly comparing these two drugs. In fact, there are two ongoing studies. The Bendroflumethiazide versus Indapamide for Primary Hypertension: Observational (BISON) 60 study within the Clinical Practice Research Datalink 61 is designed to compare the effect of bendroflumethiazide vs. indapamide on the risk of cardiovascular outcomes using real‐world data. The Evaluating Diuretics in Normal Care (EVIDENCE) study is a cluster‐randomized evaluation of hypertension prescribing policy in which primary care surgeries have their practice drug formularies randomized to either indapamide or bendroflumethiazide 62.

In summary, we found no good comparative effectiveness data on the two most commonly prescribed diuretics for hypertension in the UK.

Nomenclature of targets and ligands

Key ligands in this article are hyperlinked to corresponding entries in http://www.guidetopharmacology.org, the common portal for data from the IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 63.

Competing Interests

There are no competing interests to declare.

We would like to thank the staff of the Robertson Trust Medical Library at the University of Dundee for help with retrieval of publications for this review. We also acknowledge the NHS Education for Scotland's The Knowledge Network for access to their database.

Appendix 1.

Results by type of outcome

| Number of events by type of outcome | Barraclough et al. 1973 cooperative randomized controlled trial | MRC working party 1985 MRC‐TMH | Beckett et al. 2008 HYVET study | Indirect comparison indapamide vs. bendroflumethiazide | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment group | Bendroflumethiazide N = 58 | Placebo N = 58 | RR (95% CI)a | Bendroflumethiazide N = 4297 | Placebo N = 8654 | RR (95% CI)a | Indapamide N = 1933 | Placebo N = 1912 | RR (95% CI)a | RR (95% CI)a |

| All deaths | 1 | 3 | 0.33 (0.04, 3.11) | 128 | 253 | 1.02 (0.82, 1.26) | 196 | 235 | 0.82 (0.69, 0.99) | 0.82 (0.57, 1.18) |

| Cardiovascular deaths | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 69 | 139 | 0.99 (0.75, 1.33) | 99 | 121 | 0.81 (0.63, 1.05) | 0.82 (0.56, 1.20) |

| Noncardiovascular deaths | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 59 | 114 | 1.04 (0.76, 1.42) | 97 | 114 | 0.84 (0.65, 1.10) | 0.81 (0.54, 1.22) |

| Stroke | 0 | 0 | ‐ | 18 | 109 | 0.33 (0.20, 0.55) | 51 | 69 | 0.73 (0.51, 1.04) | 2.21 (1.19, 4.11) |

| Coronary events | 1 | 2 | 0.5 (0.05, 5.36) | 119 | 234 | 1.02 (0.82, 1.27) | 9 | 12 | 0.74 (0.31, 1.76) | 0.73 (0.30, 1.79) |

| All cardiovascular events | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 140 | 352 | 0.80 (0.66, 0.97) | 138 | 193 | 0.71 (0.57, 0.87) | 0.89 (0.67, 1.18) |

| Withdrawals for medical reasons | 1 | 9 | 0.11 (0.01, 0.85) | 481 | 1215 | 0.80 (0.72, 0.88) | 4 | 5 | 0.79 (0.21, 2.94) | ‐ |

| Withdrawals for nonmedical reasons | 10 | 9 | 1.11 (0.49, 2.53) | 0 | 0 | – | 647 | 656 | 0.98 (0.89, 1.07) | ‐ |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg d | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | −25.2 (16.1)b | −13 (17.9)b | −12.20 (−13.00, −11.40)c | −25.7 (16.5)b | −13.9 (18.9)b | −11.80 (−13.47, −10.13)c | 0.94 (−1.45, 2.25)c |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg d | −20 (9.9)b | −5 (12)b | −15.00 (−21.61, −8.39)c | −12 (9.9)b | −6 (12)b | −6.00 (−6.51, −5.49)c | −11.8 (10.3)b | −6.6 (10.9)b | −5.20 (−6.20, −4.20)c | 0.88 (−0.19, 1.95)a |

CI, confidence interval; HYVET, Hypertension in the Very Elderly Trial; MRC, Medical Research Council; MRC‐TMH, MRC Therapy for Mild Hypertension study; RR, relative risk; SD, standard deviation

Unless otherwise specified

Mean (SD)

Mean difference (95% CI)

Change from baseline

Appendix 2.

Forest plots for long‐term outcomes

BP, blood pressure; CI, confidence interval; HYVET, Hypertension in the Very Elderly Trial; MRC‐TMH, Medical Research Council Therapy for Mild Hypertension study; MI, myocardial infarction; RR, risk ratio

Appendix 3.

Network pattern

Appendix 4.

Description of studies of direct comparison between indapamide and bendroflumethiazide (short‐term outcome)

| Study characteristic | First author/publication yeara | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Bing 1981 | Zacharias 1981 | Milia 2006 | |

| Population d | Hospital (hypertension clinic) | No information | Cerebrovascular clinic |

| Inclusion criteria | Mild essential hypertension (defined as diastolic BP ≥95 mmHg) | Patients treated with atenolol 100 mg day–1 or 200 mg day–1 as their sole antihypertensive therapy for at least 8 weeks | Ambulant patients with first‐ever minor hemispheric ischaemic stroke or transient ischaemic attack with or without hypertension status |

| Exclusion criteria | Clinical gout, abnormal renal function (judged by blood urea and serum creatinine) | Cardiac, renal or hepatic failure, known sensitivity to thiazide diuretics or pregnant | Significant poststroke disability (Barthel score <70), comorbidity or contraindication to antihypertensive treatment; pre‐existing moderate to severe renal impairment (serum creatinine >200 mmol l–1) or with ≥50% stenosis of either carotid artery, BP >180/100 mmHg |

| Definition of hypertension | Mild essential hypertension (DBP ≥95 mmHg) | Hypertension not adequately controlled on atenolol alone | No information |

| How BP was measured | Auscultatory method; supine and upright position | Hawksley random zero sphygmomanometer; supine and upright position | Critikon Dinamap equipment (mean of three measurements); supine position |

| Sponsorship | Servier Laboratories | No information | No information |

| Follow‐up | 16 weeks on single drug, followed by 16 weeks of combined therapy (indapamide + bendroflumethiazide) | 12 weeks | 28 days |

| Age (years) | 32–64 | No information | 68.8 ± 10.6 |

| Sex N (%) females | 10 (50) | 9 (53) | 13 (50) |

| Indapamide | 2.5 mg daily | 2.5 mg + placebo–bendroflumethiazide 5 mg | 2.5 mg daily |

| Bendroflumethiazide | 5.0 mg daily | 5 mg + placebo–indapamide 2.5 mg | 2.5 mg daily |

| Study size | 20 | 17 | 26 |

| Indapamide | 10 | No information | 13 |

| Bendroflumethiazide | 10 | No information | 13 |

BP, blood pressure; DBP, diastolic BP

All studies were conducted in the UK

Appendix 5.

Assessment of risk of bias

| First author/publication year | Random sequence generation | Allocation concealment | Blinding of participants and personnel | Blinding of outcome assessment | Incomplete outcome data | Free from selective reporting | Other sources of bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bing 1981 | − | − | − | − | − | − | ? |

| Zacharias 1981 | − | + | − | − | − | − | ? |

| Milia P 2006 | − | − | + | − | − | − | ? |

Appendix 6.

Results for short‐term blood pressure (studies of direct comparison)

| Study characteristic | First author/publication year | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Bing 1981 | Zacharias 1981 | Milia 2006 | |

| 16‐week follow‐up | 12‐week follow‐up | ||

| Group size (per protocol) | |||

| Indapamide | 8 | Assumed 8 | 13 |

| Bendroflumethiazide | 7 | Assumed 8 | 12 |

| Withdrawals for medical reasons | |||

| Indapamide | 1 (dizziness) | 1 (at 20 weeks due to depression) | 0 |

| Bendroflumethiazide | 3 (1 dizziness; 2 uncontrolled hypertension) | 0 | 1 (viral illness) |

| Withdrawals for nonmedical reasons | |||

| Indapamide | 1 (failed to complete the study) | 0 | 0 |

| Bendroflumethiazide | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Systolic blood pressure, supine (mmHg) | |||

| Indapamide | |||

| Baseline mean (SD) | No information | 172 | 145 (15.5) |

| Mean change from baseline (SD) | −20.2 (19.9) | −15a | −14.7 (12.5) |

| Bendroflumethiazide | |||

| Baseline mean (SD) | No information | 181 | 134.8 (19.3) |

| Mean change from baseline (SD) | −14.1 (19.9) | −22a | −7.7 (9.16) |

| Diastolic blood pressure, supine (mmHg) | |||

| Indapamide | |||

| Baseline mean (SD) | No information | 101 | 78.3 (7.4) |

| Mean change from baseline (SD) | −6.4 (6.9)a | −10 | −7.8 (5.7)a |

| Bendroflumethiazide | |||

| Baseline mean (SD) | No information | 104 | 73.4 (10.4) |

| Mean change from baseline (SD) | −3.7 (6.9)a | −11 | −3.67 (4.9)a |

| Authors’ conclusion | Indapamide produced a significant but equivalent fall in blood pressure to that observed with bendroflumethiazide | Both drugs produced a similar, modest improvement in blood pressure | Both diuretics reduced blood pressure to a similar and significant degree |

SD, standard deviation

Estimated from information in the paper

Appendix 7.

Forest plot (short‐term outcome, studies of direct comparison)

CI, confidence interval; ID, identification; SD, standard deviation; SMD, Standardized Mean Difference

Appendix 8.

Funnel plots for long‐term outcomes (all deaths and coronary events) and short‐term outcomes (blood pressure)

BP, blood pressure; SMD, Standardized Mean Difference; se, standard error

Macfarlane, T. V. , Pigazzani, F. , Flynn, R. W. V. , and MacDonald, T. M. (2019) The effect of indapamide vs. bendroflumethiazide for primary hypertension: a systematic review. Br J Clin Pharmacol, 85: 285–303. 10.1111/bcp.13787.

References

- 1. World Health Organization. Global Health Observatory (GHO) data. Available at http://www.who.int/gho/ncd/risk_factors/blood_pressure_prevalence_text/en/ (last accessed 18 September 2017).

- 2. Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo JL Jr, et al The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: the JNC 7 report. JAMA 2003; 28: 2560–2572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ernst ME, Moser M. Use of diuretics in patients with hypertension. N Engl J Med 2009; 361: 2153–2164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wright JM, Musini VM. First‐line drugs for hypertension. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009; 4: CD001841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Garjón J, Saiz LC, Azparren A, Elizondo JJ, Gaminde I, Ariz MJ, et al First‐line combination therapy versus first‐line monotherapy for primary hypertension. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017; 1: CD010316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sheppard JP, Schwartz CL, Tucker KL, McManus RJ. Modern management and diagnosis of hypertension in the United Kingdom: home care and self‐care. Ann Glob Health 2016; 82: 274–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tamargo J, Segura J, Ruilope LM. Diuretics in the treatment of hypertension. Part 1: thiazide and thiazide‐like diuretics. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2014; 15: 527–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) . Hypertension in adults: diagnosis and management. Clinical guideline August 2011. Available at https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg127 (last accessed 13 April 2017).

- 9. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) . Hypertension: evidence update March 2013. A summary of selected new evidence relevant to NICE clinical guideline 127 ‘clinical management of primary hypertension in adults’; 2011. Evidence update 32. March 2013. Available at https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg127/evidence/evidence-update-248584429.%20Accessed%202017(last accessed 13 April 2017).

- 10. Brown MJ, Cruickshank JK, Macdonald TM. Navigating the shoals in hypertension: discovery and guidance. BMJ 2012; 344: d8218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Musini VM, Nazer M, Bassett K, Wright JM. Blood pressure‐lowering efficacy of monotherapy with thiazide diuretics for primary hypertension. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014; 5: CD003824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Peterzan MA, Hardy R, Chaturvedi N, Hughes AD. Meta‐analysis of dose‐response relationships for hydrochlorothiazide, chlorthalidone, and bendroflumethiazide on blood pressure, serum potassium, and urate. Hypertension 2012; 59: 1104–1109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Weiss J, Freeman M, Low A, Fu R, Kerfoot A, Paynter R, et al Benefits and harms of intensive blood pressure treatment in adults aged 60 years or older: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Ann Intern Med 2017; 166: 419–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Musini VM, Gueyffier F, Puil L, Salzwedel DM, Wright JM. Pharmacotherapy for hypertension in adults aged 18 to 59 years. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017; 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pahor M, Psaty BM, Alderman MH, Applegate WB, Williamson JD, Cavazzini C, et al Health outcomes associated with calcium antagonists compared with other first‐line antihypertensive therapies: a meta‐analysis of randomised controlled trials. Lancet 2000; 356: 1949–1954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Psaty BM, Lumley T, Furberg CD, Schellenbaum G, Pahor M, Alderman MH, et al Health outcomes associated with various antihypertensive therapies used as first‐line agents: a network meta‐analysis. JAMA 2003; 289: 2534–2544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Taverny G, Mimouni Y, LeDigarcher A, Chevalier P, Thijs L, Wright JM, et al Antihypertensive pharmacotherapy for prevention of sudden cardiac death in hypertensive individuals. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016; 3: CD011745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. NHS National Institute for Health Research. PROSPERO . International prospective register of systematic reviews. Available at https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/ (last accessed 14 November 2018).

- 19. The preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta‐analyses (PRISMA) statement. Available at http://prisma‐statement.org/ (last accessed 11 August 2017).

- 20. Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, Jüni P, Moher D, Oxman AD, et al The Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2011; 343: d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Musini VM, Tejani AM, Bassett K, Wright JM. Pharmacotherapy for hypertension in the elderly. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009; 4: CD000028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Miladinovic B, Chaimani A, Hozo I, Djulbegovic B. Indirect treatment comparison. Stata J 2014; 14: 76–78. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chaimani A, Higgins JPT, Mavridis D, Spyridonos P, Salanti G. Graphical tools for network meta‐analysis in STATA. PLoS One 2013; 8: e76654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Schünemann H, Brożek J, Guyatt G, Oxman A. (eds.). Handbook for grading the quality of evidence and the strength of recommendations using the GRADE approach. Updated October 2013. Available at https://gdt.gradepro.org/app/handbook/handbook.html (last accessed 14 November 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 25. GRADEpro GDT: GRADEpro guideline development tool [software]. McMaster University, 2015 (developed by Evidence Prime, Inc.). Available at https://gradepro.org/ (last accessed 14 November 2018).

- 26. Bulpitt CJ, Beckett NS, Cooke J, Dumitrascu DL, Gil‐Extremera B, Nachev C, et al Hypertension in the very elderly trial working group. Results of the pilot study for the hypertension in the very elderly trial. J Hypertens 2003; 21: 2409–2417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ueda S, Morimoto T, Ando S, Takishita S, Kawano Y, Shimamoto K, et al A randomised controlled trial for the evaluation of risk for type 2 diabetes in hypertensive patients receiving thiazide diuretics: Diuretics in the Management of Essential Hypertension (DIME) study. BMJ Open 2014; 4: e004576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wilhelmsen L, Berglund G, Elmfeldt D, Fitzsimons T, Holzgreve H, Hosie J, et al Beta‐blockers versus diuretics in hypertensive men: main results from the HAPPHY trial. J Hypertens 1987; 5: 561–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Barraclough M, Bainton D, Cochrane AL, Joy MD, Mac Gregor GA, Foley TH, et al Control of moderately raised blood pressure. Report of a co‐operative randomized controlled trial. Br Med J 1973; 3: 434–436. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Peart S. Results of MRC (UK) trial of drug therapy for mild hypertension. Clin Invest Med 1987; 10: 16–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Medical Research Council Working Party . MRC trial of treatment of mild hypertension: principal results. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1985; 291: 97–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Peart WS, Barnes GR, Broughton P. Adverse reactions to bendrofluazide and propranolol for the treatment of mild hypertension. Report of Medical Research Council Working Party on Mild to Moderate Hypertension. Lancet 1981; 2: 539–543. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Coronary heart disease in Medical Research Council trial of mild hypertension. Medical Research Council Working Party on Mild Hypertension. Br Heart J 1988; 59: 364–338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Course of blood pressure in mild hypertension after withdrawal of long term antihypertensive treatment. Medical Research Council Working Party on Mild Hypertension. BMJ 1986; 293: 988–992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Randomised controlled trial of treatment of mild hypertension: design and pilot trial. Report of the Medical Research Council Working Party on Mild to Moderate Hypertension. BMJ 1977; 1: 1437–1440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Stroke and coronary heart disease in mild hypertension: risk factors and the value of treatment. Medical Research Council Working Party on Mild Hypertension. BMJ 1988; 296: 1565–1570. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Miall WE, Brennan PJ, Mann AH. Medical Research Council's treatment trial for mild hypertension: an interim report. Clin Sci Mol Med Suppl 1976; 3: 563s–565s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Greenberg G. Comparison of the antihypertensive efficacy and adverse reactions to two doses of bendrofluazide and hydrochlorothiazide and the effect of potassium supplementation on the hypotensive action of bendrofluazide: substudies of the Medical Research Council's trials of treatment of mild hypertension: Medical Research Council Working Party. J Clin Pharmacol 1987; 27: 271–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Beckett NS, Peters R, Fletcher AE, Staessen JA, Liu L, Dumitrascu D, et al Treatment of hypertension in patients 80 years of age or older. N Engl J Med 2008; 358: 1887–1898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bulpitt C, Fletcher A, Beckett N, Coope J, Gil‐Extremera B, Forette F, et al Hypertension in the Very Elderly Trial (HYVET) protocol for main trial. Drugs Aging 2001; 18: 151–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Beckett N, Peters R, Leonetti G, Duggan J, Fagard R, Thijs L, et al Subgroup and per‐protocol analyses from the Hypertension in the Very Elderly Trial. J Hypertens 2014; 32: 1478–1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Beckett NS, Connor M, Sadler JD, Fletcher AE, Bulpitt CJ. Orthostatic fall in blood pressure in the very elderly hypertensive: results from the Hypertension in the Very Elderly Trial (HYVET) – pilot. J Hum Hypertens 1999; 13: 839–840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Bulpitt CJ, Fletcher AE, Amery A, Coope J, Evans JG, Lightowlers S, et al The Hypertension in the Very Elderly Trial (HYVET). J Hum Hypertens 1994; 8: 631–632. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Bulpitt CJ, Fletcher AE, Amery A, Coope J, Evans JG, Lightowlers S, et al The Hypertension in the Very Elderly Trial (HYVET). Rationale, methodology and comparison with previous trials. Drugs Aging 1994; 5: 171–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Bing RF, Russell GI, Swales JD, Thurston H. Indapamide and bendrofluazide: a comparison in the management of essential hypertension. Br J Clin Pharmacol 1981; 12: 883–886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Zacharias FJ. A comparative study of the efficacy of indapamide and bendrofluazide given in combination with atenolol. Postgrad Med J 1981; 57 (Suppl. 2): 51–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Milia P, Muir S, Alem M, Lees K, Walters M. Comparison of the effect of diuretics on carotid blood flow in stroke patients. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 2006; 47: 446–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. EBM DataLab, University of Oxford, 2018. Available at https://openprescribing.net/ (last accessed 2 September 2018).

- 49. Liang W, Ma H, Cao L, Yan W, Yang J. Comparison of thiazide‐like diuretics versus thiazide‐type diuretics: a meta‐analysis. J Cell Mol Med 2017; 21: 2634–2642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Leung AA, Daskalopoulou SS, Dasgupta K, McBrien K, Butalia S, Zarnke KB, et al Hypertension Canada's 2017 guidelines for diagnosis, risk assessment, prevention, and treatment of hypertension in adults. Can J Cardiol 2017; 33: 557–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, Casey DE Jr, Collins KJ, Dennison Himmelfarb C, et al ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on clinical practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017; pii: S0735–1097(17)41519–1. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Liu LS. Writing group of 2010 Chinese Guidelines for the Management of Hypertension: 2010 Chinese guidelines for the management of hypertension. Chin J Cardiol 2011; 39: 579–615. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Lurbe E, Agabiti‐Rosei E, Cruickshank K, Dominiczak A, Erdine S, Hirth A, et al European Society of Hypertension guidelines for the management of high blood pressure in children and adolescents. J Hypertens 2016; 34: 1887–1920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Sterne JAC. Why the Cochrane risk of bias tool should not include funding source as a standard item [editorial]. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013; 12 10.1002/14651858.ED000076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Song F, Loke YK, Walsh T, Glenny AM, Eastwood AJ, Altman DG. Methodological problems in the use of indirect comparisons for evaluating healthcare interventions: survey of published systematic reviews. BMJ 2009; 338: b1147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Thorlund K, Mills EJ. Sample size and power considerations in network meta‐analysis. Syst Rev 2012; 1: 41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Donaldson JH, Gray M. Systematic review of grading practice: is there evidence of grade inflation? Nurse Educ Pract 2012; 12: 101–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Jansen JP, Fleurence R, Devine B, Itzler R, Barrett A, Hawkins N, et al Interpreting indirect treatment comparisons and network meta‐analysis for health‐care decision making: report of the ISPOR task force on indirect treatment comparisons good research practices: part 1. Value Health 2011; 14: 417–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Jansen JP, Trikalinos T, Cappelleri JC, Daw J, Andes S, Eldessouki R, et al Indirect treatment comparison/network meta‐analysis study questionnaire to assess relevance and credibility to inform health care decision making: an ISPOR‐AMCP‐NPC good practice task force report. Value Health 2014; 17: 157–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. The European Network of Centres for Pharmacoepidemiology and Pharmacovigilance (ENCePP®). Available at http://www.encepp.eu/encepp/viewResource.htm?id=25524 (last accessed 14 November 2018).

- 61. Clinical Practice Research Datalink. Available at https://www.cprd.com/home/ (last accessed 14 November 2018).

- 62. Evaluating Diuretics in Normal Care (EVIDENCE) – a cluster randomised evaluation of hypertension prescribing policy. Available at http://www.isrctn.com/ISRCTN46635087 (last accessed 16 April 2018).

- 63. Harding SD, Sharman JL, Faccenda E, Southan C, Pawson AJ, Ireland S, et al The IUPHAR/BPS guide to pharmacology in 2018: updates and expansion to encompass the new guide to immunopharmacology. Nucl Acids Res 2018; 46: D1091‐D1106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]