Reactivation of latent VZV in humans can result in serious neurological complications. VZV-specific cell-mediated immunity is critical for the maintenance of latency. Similar to VZV in humans, SVV causes varicella in monkeys, establishes latency in ganglia, and reactivates to produce shingles. Here, we show that depletion of CD4 T cells in rhesus macaques results in SVV reactivation, with virus antigens found in zoster rash and SVV DNA and antigens found in lungs, lymph nodes, and ganglia. These results suggest the critical role of CD4 T cell immunity in controlling varicella virus latency.

KEYWORDS: CD4 T cell depletion, animal model, simian varicella virus reactivation

ABSTRACT

Rhesus macaques intrabronchially inoculated with simian varicella virus (SVV), the counterpart of human varicella-zoster virus (VZV), developed primary infection with viremia and rash, which resolved upon clearance of viremia, followed by the establishment of latency. To assess the role of CD4 T cell immunity in reactivation, monkeys were treated with a single 50-mg/kg dose of a humanized monoclonal anti-CD4 antibody; within 1 week, circulating CD4 T cells were reduced from 40 to 60% to 5 to 30% of the total T cell population and remained low for 2 months. Very low viremia was seen only in some of the treated monkeys. Zoster rash developed after 7 days in the monkey with the most extensive CD4 T cell depletion (5%) and in all other monkeys at 10 to 49 days posttreatment, with recurrent zoster in one treated monkey. SVV DNA was detected in the lung from two of five monkeys, in bronchial lymph nodes from one of the five monkeys, and in ganglia from at least two dermatomes in three of five monkeys. Immunofluorescence analysis of skin rash, lungs, lymph nodes, and ganglia revealed SVV ORF63 protein at the following sites: sweat glands in skin; type II cells in lung alveoli, macrophages, and dendritic cells in lymph nodes; and the neuronal cytoplasm of ganglia. Detection of SVV antigen in multiple tissues upon CD4 T cell depletion and virus reactivation suggests a critical role for CD4 T cell immunity in controlling varicella virus latency.

IMPORTANCE Reactivation of latent VZV in humans can result in serious neurological complications. VZV-specific cell-mediated immunity is critical for the maintenance of latency. Similar to VZV in humans, SVV causes varicella in monkeys, establishes latency in ganglia, and reactivates to produce shingles. Here, we show that depletion of CD4 T cells in rhesus macaques results in SVV reactivation, with virus antigens found in zoster rash and SVV DNA and antigens found in lungs, lymph nodes, and ganglia. These results suggest the critical role of CD4 T cell immunity in controlling varicella virus latency.

INTRODUCTION

Varicella-zoster virus (VZV) causes chickenpox (varicella) in children, becomes latent in ganglia, and reactivates decades later to produce shingles (zoster) in the elderly due to the decline of VZV-specific T cells important in maintaining virus latency (1). Reactivation of latent VZV is associated with serious neurological complications, including postherpetic neuralgia (the most common cause of suicide in the elderly), characterized by the persistence of pain for more than 3 months after zoster (2). VZV reactivation can result in vasculopathy (3) and giant cell arteritis, which causes primary systemic vasculitis, leading to blindness and stroke, and other multisystem diseases that can occur without rash (4–6). Persistent inflammation, with the predominance of T cells and macrophages, is seen for months after zoster in arteries of patients with vasculopathy (7). Significant inflammation is also seen in colon biopsy specimens from zoster patients with pseudo-obstruction (8). Zoster-associated lymphadenitis has also been reported (9). Lastly, zoster occurs in 8 to 18% of renal transplant recipients who receive immunosuppressive therapy (10, 11). Zoster occurs at significantly higher rates in HIV-infected individuals (12). A higher incidence of reactivation is associated with low CD4 counts, with an incidence three times higher in HIV-infected individuals with a CD4 count of <200 cells/μl than in those with a CD4 count of >500 cells/μl (13). Furthermore, VZV-specific T cell responses in subjects with CD4 counts less than 100 are generally undetectable (14).

VZV infects only humans. Inoculation of VZV into small animals, including mice (15), guinea pigs (16–19), and rats (20, 21), does not mimic all the features of primary VZV infection or latency seen in humans, although virus DNA can be found in ganglia. Inoculation of monkeys with VZV produces immune responses without clinical symptoms and does not establish latency in ganglia (22, 23). Importantly, VZV cannot be reactivated in any of these models. We and others have shown that simian varicella virus (SVV) infection produces chickenpox in monkeys, which parallels VZV infection in humans (24–26). Depletion of CD4 T cells during primary SVV infection in rhesus macaques led to higher viremia and disseminated varicella (27). Monkeys latently infected with SVV and immunosuppressed using a combination of radiation, tacrolimus, and prednisone developed zoster, with robust proinflammatory and decreased anti-inflammatory responses in serum just before zoster rash (28, 29). At the time of zoster in immunosuppressed monkeys, SVV antigens were detected in the skin, lungs, and ganglia, although only a limited amount of DNA was seen in blood. SVV antigens were detected in macrophages and dendritic cells in lymph nodes. The presence of SVV in lymph nodes, as verified by quantitative PCR detection of SVV DNA, may reflect SVV infection of these cells in lymph nodes or the presentation of viral antigens to T cells to induce an immune response against SVV or both (30). Recently, Arnold et al. (31) demonstrated subclinical SVV reactivation in rhesus macaques thymectomized and depleted in CD4 and CD8 T cells. Here, we induced clinical SVV reactivation in rhesus macaques through CD4 depletion and analyzed multiple tissues for virus antigens.

RESULTS

Primary SVV infection in rhesus macaques and establishment of latency.

Five Indian rhesus macaques, intratracheally inoculated with wild-type SVV, developed wide-spread varicella skin rash at 7 days postinoculation (dpi), which continued until 28 dpi (Fig. 1 [see also Fig. 3A] and Tables 1 and 2) but resolved thereafter in all monkeys. Varicella rash was most pronounced in monkey JF07 by 9 dpi. At 7 dpi, moderate viremia, ranging from 2 to 73 copies of SVV DNA in 500 ng of total DNA, was seen in monkeys JF07, IE31, IT30, and JF03 (Table 3). Viremia was cleared by 14 dpi in IT30 and IT37, by 21 dpi in JF03, and by 183 dpi in JF07 and IE31. The different levels of viremia might reflect differences in antiviral immune responses. The two male monkeys JF07 and IE31 developed a severe varicella rash earlier than the female monkeys IT30 and IT37. Furthermore, viremia was higher in male monkeys JF07 and IE31, suggesting a role of the sex of the monkeys in the extent of acute SVV infection. Neutralization assays to measure SVV-specific antibody levels showed that all monkeys were SVV seropositive by 46 dpi, with high antibody levels (1:160 and >1:320) (Table 4).

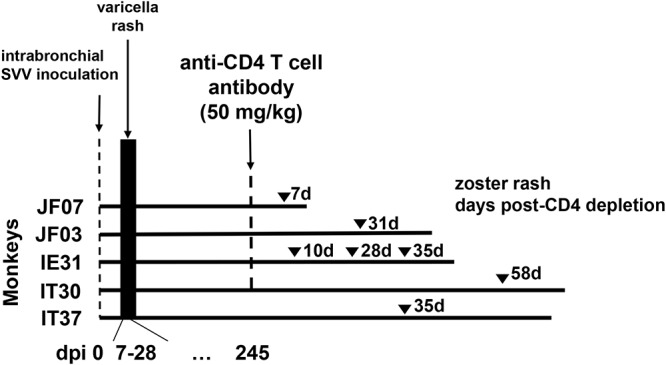

FIG 1.

Experimental design. Five rhesus macaques (JF07, JF03, IE31, IT30, and IT37) were inoculated intrabronchially with SVV (105 PFU). All monkeys developed varicella rash 7 to 14 days after inoculation. Eight months (245 days) later, four of the monkeys (JF07, JF03, IE31, and IT30) were treated intravenously with 50 mg/kg of anti-CD4 antibody; monkey IT37 was left untreated. Seven days after CD4 depletion, monkey JF07 developed zoster rash. Monkey JF03 developed zoster 28 days after CD4 depletion, while monkey IE31 developed zoster 10, 28, and 35 days after CD4 depletion. Monkey IT30 developed zoster 49 days after CD4 depletion. Monkey IT37 developed zoster 38 days after the CD4 depletion treatment in the other 4 monkeys. Monkeys JF07, JF03, IE31, IT30, and IT37 were euthanized 9, 16, 15, 35, and 33 days, respectively, after the last episode of zoster, and tissues were collected for analysis.

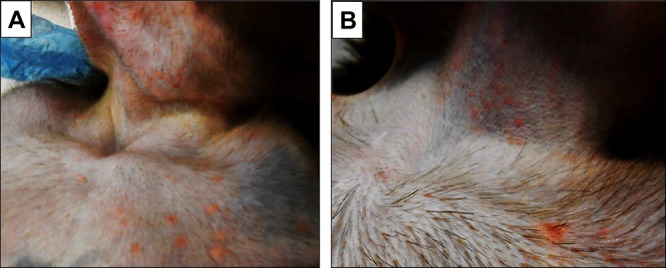

FIG 3.

Skin rash after varicella and zoster in the same monkey. Skin rash was seen in the upper thorax and chin 9 days after SVV inoculation (primary infection) (A) and in the upper thorax and neck 35 days after CD4 depletion (zoster) (B) in monkey IE31.

TABLE 1.

Ages, sex, and weights of Indian rhesus macaques

| Monkey | Age (yr) | Sex | Wt (kg) |

|---|---|---|---|

| JF07 | 3.0 | M | 5.2 |

| JF03 | 3.0 | M | 4.6 |

| IE31 | 4.9 | M | 7.2 |

| IT30 | 6.1 | F | 5.5 |

| IT37 | 5.2 | F | 6.0 |

TABLE 2.

Varicella rash after SVV inoculationa

| Monkey | Rash score at various times postinoculation |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 dpi | 4 dpi | 7 dpi | 9 dpi | 11 dpi | 14 dpi | 21 dpi | 28 dpi | 46 dpi | 64 dpi | |

| JF07 | – | – | ++ | ++++ | ++++ | +++ | ++ | + | – | – |

| JF03 | – | – | + | ++ | ++ | + | + | – | – | – |

| IE31 | – | – | – | ++++ | ++ | + | + | – | – | – |

| IT30 | – | – | + | ++ | ++ | + | + | – | – | – |

| IT37 | – | – | – | ++ | +++ | ++ | + | – | – | – |

Rash key: –, no rash seen; +, 1 to 5 lesions; ++, 6 to 20 lesions; +++, 21 to 50; ++++, >50 lesions.

TABLE 3.

Viremia after SVV inoculation

| Monkey | Mean SVV ORF61 DNA copy no./500 ng of DNA ± SD at various times postinoculation |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7 dpi | 9 dpi | 14 dpi | 21 dpi | 46 dpi | 183 dpi | |

| JF07 | 73 ± 5.50 | 74 ± 22.34 | 79 ± 17.40 | 7 ± 2.43 | 20 ± 8.81 | 0 |

| JF03 | 2 ± 2.20 | 0 | 1 ± 2.48 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| IE31 | 52 ± 38.13 | 19 ± 7.58 | 3 ± 1.51 | 0 | 3 ± 2.35 | 0 |

| IT30 | 12 ± 11.21 | 5 ± 6.27 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| IT37 | NAa | 3 ± 1.75 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

NA, sample not available.

TABLE 4.

Neutralizing antibody response to SVV infection and CD4 depletion in rhesus macaques

| Monkey | Anti-SVV antibody titera |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary infection |

CD4 depletion and SVV reactivation |

Necropsy (dpix) | ||||||||

| Prebleed | 46 dpi | 179 dpi | Prebleed | 7 dpix | 42 dpix | 49 dpix | 58 dpix | 77 dpix | ||

| JF07 | <1:10 | >1:320 | >1:320 | 1:160 | >1:320 | NA | NA | NA | NA | >1:320 (7) |

| JF03 | <1:10 | 1:320 | >1:320 | 1:320 | >1:320 | >1:320 | NA | NA | NA | >1:320 (45) |

| IE31 | <1:10 | >1:320 | >1:320 | >1:320 | >1:320 | 1:320 | NA | NA | NA | >1:320 (50) |

| IT30 | <1:10 | >1:320 | >1:320 | >1:320 | >1:320 | >1:320 | >1:320 | >1:320 | >1:320 | >1:320 (84) |

| IT37b | <1:10 | 1:160 | 1:160 | 1:80 | 1:160 | 1:80 | 80 | 40 | ND | 1:160 (77) |

Anti-SVV antibody titers are expressed as the serum dilution that neutralized at least 80% of SVV plaques compared to control cultures. dpi, days postinoculation; dpix, days after CD4 depletion; NA, not applicable since the monkey was euthanized; ND, not determined.

Not CD4 depleted.

CD4 T cell depletion and SVV reactivation.

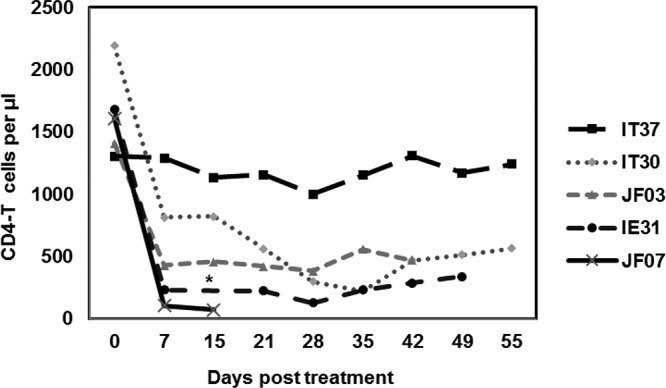

After SVV infection and virus clearance, monkeys JF07, JF03, IE31, and IT30 were treated at 245 dpi once intravenously with 50 mg/kg of anti-CD4 antibody; monkey IT37 was left untreated (Fig. 1). Before treatment, CD4 T cell levels were within normal range (1,200 to 2,200 CD4 T cells/µl) (Fig. 2). 1 week after treatment, CD4 T cell levels were substantially reduced (108 to 815 CD4 T cells/µl) and remained low throughout the experiment in all treated monkeys; the levels in the untreated monkey IT37 remained in normal range (1,200 CD4 T cells/µl). At 15 days after CD4 depletion (dpix), CD4 T cells decreased to 73 cells/µl in monkey JF07, which had developed zoster rash in the left upper arm at 7 dpix (Fig. 1). After confirmation of zoster by immunohistochemical detection of SVV antigens in biopsied skin rash (data not shown), monkey JF07 was euthanized 9 days later, and the lungs, lymph nodes, and ganglia were collected for analysis. Zoster lesions were also observed at 31 dpix in the right upper arm and midabdomen of monkey JF03, which was euthanized 16 days after zoster, and tissues were harvested for analysis. In monkey IE31, multiple episodes of zoster rash were observed, with the first in the right forearm at 10 dpix, which resolved over 5 days; a second new rash in the upper thorax at 28 dpix, which resolved over 3 days; and a possible third rash or an extension of the rash from 28 dpix on the right neck at 35 dpix, which resolved over 7 days. The monkey was euthanized 15 days after zoster. As in monkey JF07, occurrence of zoster in monkey IE31 coincided with the strong reduction in CD4 T cell levels (Fig. 2 and 3B). Monkey IT30 showed zoster rash in the left upper thorax and shoulder at 58 dpix.

FIG 2.

Reduction in CD4 T lymphocyte levels after treatment of latently infected rhesus macaques with anti-CD4 antibodies. Blood samples collected between 0 and 55 days after CD4 depletion were used for analysis. Absolute numbers of CD4 T cells/µl in peripheral blood were plotted against the days posttreatment for all rhesus macaques latently infected with SVV. *, The sample from monkey IE31 at 15 dpix was not available.

The untreated monkey IT37, pair housed with IT30, also developed zoster rash in the lateral abdomen, at 38 dpix. This reactivation was possibly due to the declined SVV-specific antibody levels (Table 4) in addition to possible reduction in virus-specific cellular immune response, known to produce zoster. Areas of skin associated with zoster rash in monkey JF03 was biopsied and analyzed by immunofluorescence using rabbit polyclonal antibodies raised against peptides specific for SVV ORF63 to confirm the presence of SVV antigens. SVV ORF63 protein was detected in sweat glands (Fig. 4). Monkeys IT30 and IT37 were euthanized at 26 and 33 days, respectively, after the appearance of zoster rash.

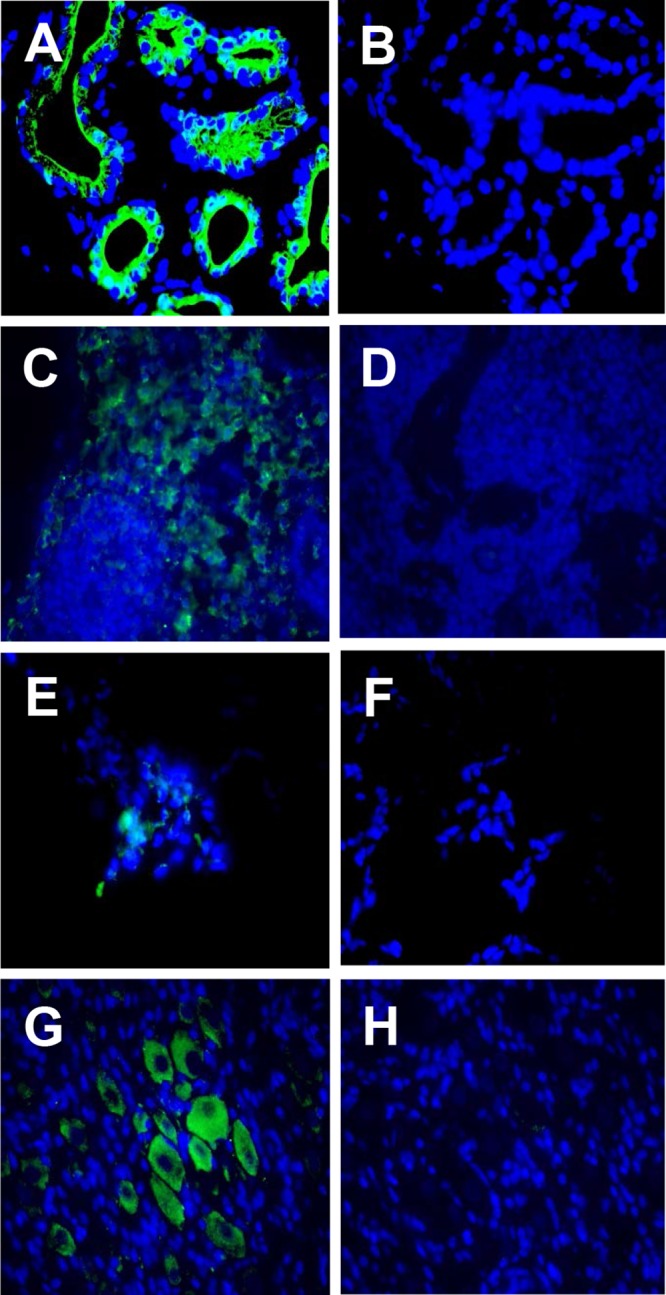

FIG 4.

Detection of SVV antigens in tissues of monkeys after SVV reactivation after CD4 depletion. Paraformaldehyde-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue sections were analyzed by immunofluorescence. (A) In monkey JF03, SVV ORF63 protein was found in the sweat glands in skin with zoster rash using rabbit polyclonal antibodies specific for SVV ORF63 peptides. SVV glycoproteins gH and gL were detected using rabbit polyclonal antibodies raised against peptides specific for these glycoproteins in the medulla of axillary lymph nodes from monkey IE31 (C), in the lung alveoli of monkey JF07 (E), and in the cytoplasm of neurons in thoracic ganglia from monkey JF07 (G). No staining was seen in the respective adjacent sections when preimmune rabbit serum was substituted for anti-SVV antibody (B, D, F, and H). Donkey Alexa Fluor 488-tagged anti-rabbit IgG(H+L) antibody was used as a secondary antibody and visualized at 385 nm. DAPI (4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole) staining shows the nuclei of cells. Magnification, ×600.

Low-level SVV DNA in blood after CD4 T cell depletion.

DNA extracted from blood samples collected after treatment with anti-CD4 T cell antibody was analyzed by real-time qPCR for sequences specific for SVV ORF61 (Table 5). Each sample was analyzed in triplicate, and the number of copies was calculated as an average of three measurements (± the standard deviations [SD]). The sensitivity of our real-time qPCR was one to five copies/μg of DNA (32). Blood samples from monkey JF07 obtained before CD4 depletion contained three copies of SVV DNA/500 ng of total DNA in the absence skin rash (Table 5), suggesting low-level virus persistence. However, none of the other monkeys had SVV DNA in their blood at the time of CD4 depletion. SVV DNA was not detected in any of the blood samples from monkey JF03 after CD4 depletion, including at 28 dpix, when it developed zoster, and at 35 and 42 dpix. Blood samples taken at 7, 14, 22, 35, and 50 dpix from monkey IE31 contained low copy numbers of SVV DNA, with skin rash coinciding with the low copy number only at 35 dpix. Thus, unlike primary infection (Table 3), viremia was minimal or absent in monkeys after immunosuppression. It is interesting that both of the monkeys (JF07 and IE31) in which SVV DNA was detected in blood samples after CD4 depletion were males. As mentioned before, the sex of the monkeys might have played a role in SVV reactivation from latency.

TABLE 5.

Viremia after CD4 depletion

| Monkey | Mean SVV ORF61 DNA copy no./500 ng ± the SD at various times after CD4 depletiona |

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 dpix | 7 dpix | 14 dpix | 22 dpix | 28 dpix | 35 dpix | 42 dpix | 49 dpix | 50 dpix | 58 dpix | 63 dpix | 70 dpix | 77 dpix | 83 dpix | |

| JF07 | 3 ± 0.62 | 0 | 0 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| JF03 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| IE31 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 ± 1.78 | 0 | 5 ± 1.20 | 0 | 0 | 6 ± 2.05 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| IT30 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ND | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| IT37 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ND | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ND |

NA, not applicable (since the monkey was euthanized); ND, sample not available; dpix, days after CD4 depletion.

Detection of SVV DNA in ganglia, lungs, and lymph nodes from rhesus macaques after zoster.

Ganglia from the side of the neuraxis opposite to those used for immunofluorescence analysis were used for DNA extraction and analyzed by real-time qPCR for SVV ORF61-specific sequences (Table 6). Ganglia from each of the dermatomes were pooled for analysis. SVV DNA was detected in four of five ganglion samples from monkey JF07, which was not surprising since this monkey had the most extensive viremia during primary infection (Table 3), as well as the most extensive CD4 depletion, and was the first to develop zoster. Monkey JF03 revealed SVV DNA only in thoracic and lumbar ganglia, consistent with the location of zoster rash in the upper arm and midabdomen. In monkey IE31, which had multiple episodes of zoster, SVV DNA was detected in three of five ganglia, with the highest copy number in cervical ganglia, consistent with zoster rash in the upper parts of the body. No SVV DNA was detected in any of the ganglia from monkeys IT30 and IT37 despite zoster rash, possibly due to the extremely low viremia in these monkeys during primary infection (Table 3). As noted before, SVV DNA was detected in multiple ganglia from monkeys JF07 and IE31, both of which were males, suggesting a role of the sex of the monkeys in the establishment of SVV latency.

TABLE 6.

Detection SVV DNA in ganglia of monkeys after SVV reactivation

| Monkey | Mean SVV ORF61 DNA copy no./500 ng ± the SD from ganglia |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trigeminal | Cervical | Thoracic | Lumbar | Sacral | |

| JF07 | 273 ± 55.70 | 43 ± 13.61 | 0 | 70 ± 33.58 | 14 ± 4.61 |

| JF03 | 0 | 0 | 5 ± 2.48 | 7 ± 9.91 | 0 |

| IE31 | 0 | 119 ± 19.55 | 3 ± 3.13 | 0 | 26 ± 5.35 |

| IT30 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| IT37 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

qPCR analysis of lung samples from each of the monkeys revealed DNA sequences specific for SVV ORF61 in lungs from monkeys JF07 (376 ± 48.64 copies/500 ng of DNA) and JF03 (26 ± 12.35 copies/500 ng of DNA) but not in lungs from the other three monkeys (Table 7). Analysis of lymph nodes from each monkey revealed SVV DNA only in the bronchial lymph node from monkey IE31 (Table 8).

TABLE 7.

Detection of SVV DNA in lungs of monkeys after zoster

| Monkey | SVV ORF61 DNA copy no./500 ng ± the SD |

|---|---|

| JF07 | 376 ± 48.64 |

| JF03 | 26 ± 12.35 |

| IE31 | 0 |

| IT30 | 0 |

| IT37 | 0 |

TABLE 8.

Detection of SVV DNA in lymph nodes of monkeys after zoster

| Monkey | SVV ORF61 DNA copy no./500 ng ± the SD in lymph nodea |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Axillary | Inguinal | Submandibular | Bronchial | |

| JF07 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| JF03 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| IE31 | 0 | 0 | ND | 13 ± 4.58 |

| IT30 | 0 | ND | ND | ND |

| IT37 | ND | 0 | 0 | ND |

ND, not determined.

SVV antigens in multiple tissues after zoster.

Immunofluorescence analysis at the time of zoster revealed SVV IE63 protein in sweat glands of monkey JF03 (Fig. 4A) and in skin from all other monkeys (data not shown). SVV IE63 was also detected in the epidermis and hair follicles in some of the monkeys after CD4 depletion (data not shown). SVV glycoproteins gH and gL were detected in the medulla of the axillary lymph nodes of monkey IE31 (Fig. 4C). In all five monkeys, the SVV glycoprotein and IE63 protein were detected in multiple lymph nodes (data not shown), some of which were associated with corresponding dermatomal areas of rash. Although SVV antigens were found in lymph nodes from all monkeys, the number of antigen-positive areas within each lymph node was sparse, and the number of SVV antigen-positive cells detected in different monkeys was variable. SVV IE63 protein was detected in the lung alveoli of monkey JF07 (Fig. 4E). Although SVV antigens were detected in the lungs from all monkeys (data not shown), similar to our earlier observations (30), the number of antigen-positive cells in lungs was substantially less than in lymph nodes. SVV glycoproteins gH and gL were detected mostly in the cytoplasm of neurons and, less frequently, in nonneuronal cells in thoracic ganglia from monkey JF07 (Fig. 4G). Although SVV antigens were seen in ganglia from all monkeys, the number of antigen-positive areas was lower than in lymph nodes. In all tissues, multiple sections were repeatedly analyzed using both SVV IE63 and gH/gL antibodies to confirm the presence of SVV antigens.

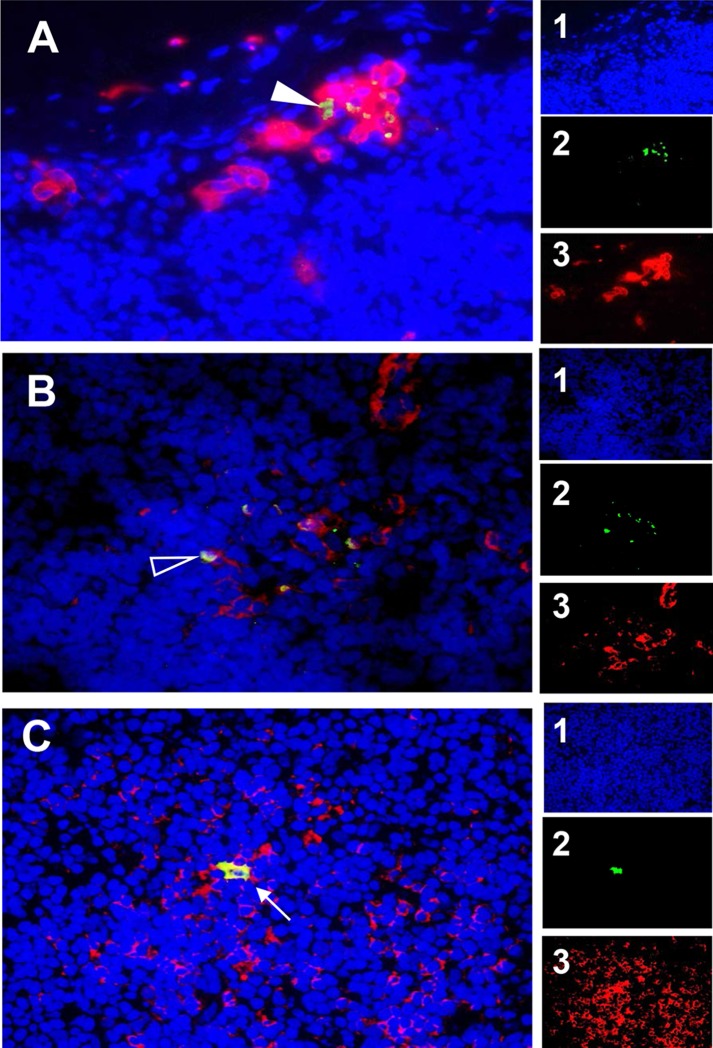

Detection of SVV antigens in macrophage, dendritic cells, and CD4 T cells in lymph nodes of rhesus macaques after reactivation.

Immunofluorescence analysis of multiple lymph nodes from all monkeys revealed colocalization of SVV antigens in macrophages, dendritic cells, and CD4 T cells. As expected, the number of CD4-positive T cells was substantially fewer in all CD4 T cell-depleted monkeys but not in untreated monkey IT37 (data not shown). Figure 5A shows an area of axillary lymph node from monkey IE31 in which SVV IE63 protein colocalized in macrophages. Colocalization of SVV IE63 protein in dendritic cells in the bronchial lymph node from monkey IE31 (Fig. 5B) and in CD4 T cells in monkey IT37 (Fig. 5C) was also observed. SVV gH and gL proteins were also detected in the same lymph nodes that contained SVV IE63 protein (Fig. 4C). Isotype control did not reveal any staining (data not shown). Consistent with our earlier observations (30), SVV antigens colocalized more often in macrophages than in any other cells, and no SVV antigens were detected in lymph nodes from latently infected or SVV-seronegative monkeys. SVV antigen was found in multiple lymph nodes in all monkeys, only some of which were associated with areas of rash.

FIG 5.

Detection of SVV ORF63 protein in macrophages, dendritic cells, and CD4 T cells in the lymph nodes of rhesus macaques. Paraformaldehyde-fixed, paraffin-embedded sections of axillary (A) and bronchial (B) lymph nodes from monkey IE31 and in axillary lymph node from monkey IT37 (C) were analyzed by immunofluorescence using rabbit polyclonal antibody specific for SVV ORF63 protein and mouse anti-human CD163 (macrophage) antibody (A), mouse anti-human CD123 (dendritic cells) antibody (B), or mouse anti-human CD4 T cell antibody (C). Donkey Alexa Fluor 488-tagged anti-rabbit IgG(H+L) antibody and goat Alexa Fluor 594-tagged anti-mouse IgG(H+L) antibody were used as secondary antibodies. Nuclei were stained with DAPI and visualized at 358 nm. The colocalization of SVV IE63 in macrophages (filled arrowhead), dendritic cells (open arrowhead), and CD4 T cells (arrow) is indicated. Images of individual channels are presented in panels A1 to 3, B1 to 3, and C1 to 3. Magnification, ×600.

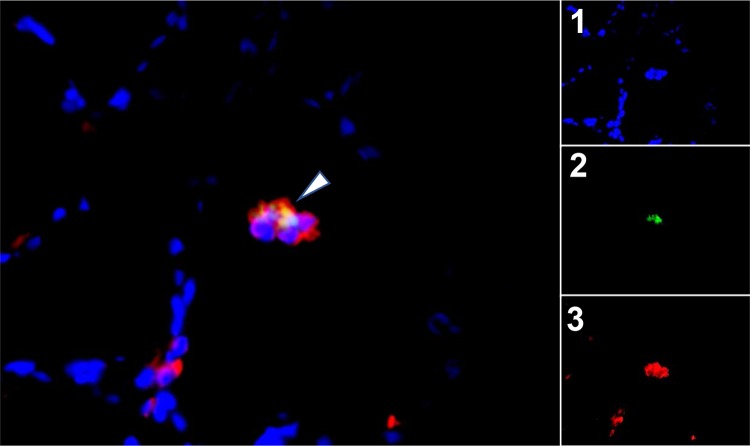

Detection of SVV antigens in type II cells in lungs from rhesus macaques after zoster.

Immunofluorescence analysis of lung sections from all monkeys for the presence SVV antigens revealed SVV IE 63 protein in type II alveolar epithelial cells (AECII) (Fig. 6). Isotype control did not reveal any staining (data not shown). Immunohistochemical analysis of multiple lung sections confirmed the detection of SVV antigens in AEC type II cells of all monkeys (data not shown). As seen in Fig. 6, the detection of SVV ORF63 protein was in isolated areas. Therefore, we attribute the lack of detection of SVV DNA in some of the monkeys (Table 7) to sampling.

FIG 6.

Detection of SVV ORF63 protein in epithelial type II cells within the alveolar surface. Paraformaldehyde-fixed, paraffin-embedded sections of lung from monkey JF07 were analyzed by immunofluorescence using rabbit polyclonal antibody specific for SVV IE63 protein and mouse monoclonal antibody specific for ABCA3 protein. SVV ORF63 protein colocalized with ABCA3 protein in the alveolar surface (arrowhead). The fluorescence-tagged secondary antibodies are as described in the legend to Fig. 5. DAPI staining shows the nuclei of cells. Images of individual channels are presented in panels 1 to 3. Magnification, ×600.

Together, our results indicate low-level SVV viremia after reactivation in latently infected rhesus macaques depleted of CD4 T cells and show that detection of SVV DNA in ganglia correlates with the dermatomal location of zoster. SVV antigens can be detected in skin, lymph nodes, type II alveolar cells in lungs, and in ganglia.

DISCUSSION

VZV-specific cell-mediated immunity is important in maintaining latency in ganglia, and its decline with age is a key factor in reactivation. VZV-specific CD4 T cells decrease significantly with age (33). We previously showed that immunosuppression of SVV latently infected rhesus macaques using a combination of radiation, tacrolimus, and prednisone results in virus reactivation and that virus antigen is detectable in skin, lymph nodes, lungs, and ganglia (28, 30, 34). Here, we tested whether depletion of CD4 T cells using an anti-CD4 antibody in rhesus macaques latently infected with SVV would result in clinical zoster. We established latent SVV infection in five rhesus macaques and treated four of them once with anti-CD4 antibody. SVV reactivated in all four monkeys to produce zoster, with virus antigens found in skin, lymph nodes, lungs, and ganglia.

In all four monkeys, low-level viremia was seen intermittently after CD4 depletion, possibly reflecting the predominantly axonal rather than hematogenous spread of reactivated SVV into the skin to produce zoster. SVV reactivated first in monkey JF07, which had the highest level of viremia during primary infection (Table 3), maximum depletion in CD4 T cells, and low-level viremia prior to CD4 T cell depletion (Table 5), raising the possibility that low-level persistence of SVV, along with CD4 depletion, facilitated reactivation to produce zoster. At necropsy 1 week after zoster, the SVV DNA levels were higher in more ganglia of this monkey than in others necropsied at longer times after zoster (Table 6). Higher viremia during primary infection in monkey JF07 compared to that in other monkeys could have led to seeding of multiple ganglia, with high virus load facilitating reactivation. Like monkey JF07, monkey IE31 had extensive rash and high viremia during primary infection. After CD4 depletion, monkey IE31 had low levels of SVV DNA in blood samples taken at multiple times. Zoster was recurrent in this monkey, similar to that seen in humans with zoster (35). In both acute SVV infection and reactivation, higher levels of virus DNA were detectable in blood from monkeys JF07 and IE31. In addition, multiple ganglia were seeded in these two monkeys (Tables 3, 5, and 6). As mentioned earlier, both monkeys JF07 and IE31 were males, suggesting a sex-specific influence in virus reactivation, as has been reported in mouse model of HSV-1 infection (36). The absence of viremia in monkey JF03 after CD4 T cell depletion despite the induction of zoster was surprising. Monkey IT37, which was not treated with anti-CD4 antibody, was one of the last monkeys to develop zoster, possibly due to low SVV-specific antibody levels (Table 4) and likely also to low virus-specific cell-mediated immunity. SVV antigens were detected in biopsied zoster skin from all monkeys, mostly in sweat glands (Fig. 4). SVV antigens were also found in hair follicles and epidermis and colocalized with nerve endings in zoster skin (data not shown).

Not surprisingly, SVV DNA was detected in multiple ganglia from monkey JF07 upon necropsy. The higher prevalence of SVV DNA in ganglia of this monkey than in the others might reflect the time of euthanasia after zoster. The higher virus load seen in the cervical ganglia of monkey IE31, which contained 119 copies/µg of SVV DNA (Table 6), correlated with the location of recurrent zoster in the right forearm, upper thorax, and right neck. Similarly, the locations of zoster rash on the left upper arm in monkey JF07 and on the right upper arm and abdomen in monkey JF03 correlated with the detection of SVV DNA in cervical ganglia and in thoracic and lumbar ganglia, respectively. The absence of detectable SVV DNA in any of the ganglia from monkeys IT30 and IT37 was unexpected, however; since ganglia were harvested from one side of the neuraxis for DNA extraction, ganglia from the other side of the neuraxis that were used for immunofluorescence might have contained virus DNA.

SVV DNA was detected in lung samples from monkeys JF07 (376 copies/500 ng) and JF03 (26 copies/500 ng). The higher copy numbers of SVV DNA in lungs from monkey JF07 might be due to the higher viremia during primary infection and higher virus load in the ganglia. Lack of detection of SVV DNA in lungs of other monkeys might be due to sampling. SVV antigens were detected in AECII, which proliferate to restore the epithelium after lung injury and participate in the innate immune response to inhaled materials and organisms (37), in the lungs after zoster in most of the monkeys (Fig. 4 and 6). In some instances, SVV antigen was also detected in other cells. The presence of SVV antigens associated with AECII raises the possibility of their cellular role in clearing SVV infection after reactivation.

Bronchial lymph nodes from IE31 had SVV DNA (Table 7), correlating with the location of zoster rash in the upper parts of the body. Analysis of lymph nodes for SVV antigens revealed SVV ORF63 protein and SVV glycoproteins gH and gL in localized areas in a small number of cells within each section of multiple lymph nodes from all monkeys (Fig. 4 and 5), an observation consistent with our previous findings (30). SVV antigens were found to be localized in macrophages, dendritic cells, and CD4 T cells (Fig. 5). It is unclear whether the macrophages and dendritic cells containing SVV antigens were infected or merely serving as antigen-presenting cells. Finding SVV antigens in CD4 T cells was not surprising since SVV has been shown to be T cell-tropic (38). The lack of detection of SVV DNA in light of the presence virus antigen was not surprising since the antigens were found in isolated areas of lymph nodes.

Our detection of clinical zoster in CD4 T cell-depleted monkeys contrasts with the subclinical reactivation reported by Arnold et al. (31). The different findings might rest in the different procedures used. We treated all but one of the monkeys with anti-CD4 T cell antibody and euthanized the animals after induction of skin rash; the control monkey was among the last to develop zoster. In the studies by Arnold et al. (31), all monkeys, including the controls, were moved to another location, but subclinical reactivation was observed only in thymectomized, CD4- or CD8-depleted animals, demonstrating that subclinical reactivation results in long-lasting subtle changes in SVV transcriptional patterns in ganglia. CD4/CD8 double-positive cells may also be important in reactivation in primates since 5 to 25% of lymphocytes belong to this population (39). Furthermore, CD8+ T cells, as well as CD8+ dendritic cells, have also been shown to be important for controlling HSV-1 reactivation in mice (40, 41). Therefore, our future studies will be designed to determine whether CD8 T cell depletion in rhesus macaques latently infected with SVV would lead to zoster rash and virus spread to multiple organs. Overall, our results show that CD4 T cell immunity appears to be very important in maintaining the latent state of varicella virus, and its depletion is a useful approach to studying the mechanisms of reactivation and multisystem diseases induced in elderly humans.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Monkeys.

Three male (JF07, JF03, and E31) and two female (IT30 and IT37) SVV-seronegative rhesus macaques were used for these studies (Table 1). All monkeys were housed at the Tulane National Primate Research Center in Covington, LA. All procedures were performed according to the guidelines approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. During acute infection and reactivation, the four treated monkeys (JF07, JF03, IE31, and IT30) and one untreated monkey (IT37) were in the same room, either in single or dual cages, and separated from the larger colony. Following resolution of acute infection, each of the four animals were taken for CD4 depletion. Due to behavioral compatibility found during acute infection, IT37 and IT30 were housed together. During reactivation, the control monkey, IT37, was not treated but housed with the treated monkey IT30.

Establishment of latent SVV infection.

The deltaherpesvirus strain of SVV was propagated in rhesus fibroblasts and stock was prepared (42). All five monkeys were inoculated intratracheally with 104 PFU of wild-type SVV, as described previously (30). All five monkeys developed varicella rash at 7 to 28 dpi. Viremia was determined by qPCR on DNA extracted from sequential blood samples. The absence of SVV DNA in blood mononuclear cells after 183 dpi confirmed the establishment of latent SVV infection.

Anti-CD4 antibody treatment.

At 8 months (day 245) postinfection, four monkeys (JF07, JF03, IE31, and IT30) were treated once with a rhesus depleting anti-CD4 antibody (clone CD4R1; Keith Reimann, NIH Nonhuman Primate Reagent Resource) intravenously (50 mg/kg) (43). Monkey IT37 was left untreated. The extent of depletion of CD4 lymphocytes in blood was determined by flow cytometric analysis of CD4 and CD8 lymphocytes and complete blood cell counts to assess total CD4 cell counts per μl of whole blood at multiple time points after administration of the depleting reagent.

Aliquots from weekly blood samples (100 μl) were mixed with appropriate concentrations of commercial monoclonal antibodies and incubated for 30 min at 4°C. These whole-blood/antibody samples were lysed and washed using a whole-blood lysis protocol as previously described (44, 45). The T cell immunophenotyping antibodies used were antiCD3-V450 (SP34-2), CD4-APC (L200), and CD8-PE (RPA-T8); all were obtained from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA). Cells were fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde solution (Sigma). Acquisition of data was performed using a FACSCalibur flow cytometer using CellQuest software (BD Biosciences). Cells were gated through CD3+ “bright” T lymphocytes, at least 20,000 events were assessed by gating on lymphocytes, and the data were analyzed using FlowJo software (v9.1; TreeStar, Inc., Ashland, OR). Depletion efficiency in longitudinal samples following depletion was determined from the fraction of total CD4 T cells at each sample time point per predepletion CD4 counts.

Anti-SVV antibody titers.

SVV-specific antibody titers in sera obtained from monkeys were determined using a plaque reduction assay as described earlier (46).

DNA extraction and real-time PCR.

DNA was extracted from blood mononuclear cells and tissue specimens and analyzed by real-time qPCR using primers specific for SVV ORF61 as described previously (32). Each sample was analyzed in triplicate and scored positive only if at least two of three PCRs were positive for SVV DNA.

Immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence.

Sections of skin (5 μm; frozen in OCT) or lung, lymph node, and ganglia (paraformaldehyde fixed, paraffin embedded) were analyzed using rabbit polyclonal antibodies raised against peptides specific for either SVV ORF63 protein or SVV glycoproteins gH and gL and mouse monoclonal antibodies specific for human macrophages as described earlier (30). The antibodies used for these studies were as follows: normal rabbit serum (1:2,000 to 15,000), a mixture of polyclonal antipeptide rabbit antibodies against SVV gH and gL (1:2,000), polyclonal antipeptide rabbit antibodies against the SVV IE63 protein (1:15,000), mouse anti-human CD163 (catalog no. MCA1853 [AbD Serotec]; 1:100), mouse anti-HCD123 (BD Pharmingen, catalog no. 554527; 1:50), and the isotype antibodies mouse IgG1 (catalog no. X0931; Dako), IgG2a (catalog no. 554527; BD Pharmingen), and mouse IgG2a κ isotype (BD Pharmingen, catalog no. 555571). Additional antibodies used were as follows: donkey Alexa Fluor 488-tagged anti-rabbit IgG (catalog no. A21206 [Invitrogen]; 1:1,000) and goat Alexa Fluor 594-tagged anti-mouse IgG (catalog no. A11005 [Invitrogen]; 1:1,000).

Alveolar type II proteins were detected using a 1:500 dilution of mouse monoclonal antibody (anti-ABCA3-mouse 17-H5-24; Seven Hills Bioreagents, Cincinnati, OH) and secondary antibody (1:1,000 dilution of donkey Alexa Fluor 488-tagged anti-rabbit IgG; catalog no. A21206; Invitrogen) with or without a 1:1,000 dilution of goat Alexa Fluor 594-tagged anti-mouse IgG (catalog no. A11005; Invitrogen).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The manuscript is dedicated to the memory of our mentor Don Gilden.

We thank Werner Ouwendijk and Georges Verjans for reviewing the manuscript, Wayne Gray for providing the SVV gH and gL antibodies, Michael Koval (Emory University School of Medicine) and Dallas Jones (University of Colorado School of Medicine) for useful discussions, Brittany Feia for technical assistance, and the Tulane National Primate Research Center Veterinary Medicine staff for excellent animal care. We are grateful to Cathy Allen for preparing the manuscript and Marina Hoffman for editorial assistance.

This study was supported in part by Public Health Service grant AG032958 (to R.M., V.T.-D., and M.A.N.) from the National Institutes of Health (NIH). This study was also supported in part with federal funds from the National Center for Research Resources and the Office of Research Infrastructure Programs (ORIP) of the NIH through grant P51 RR00164 to the Tulane National Primate Research Center (V.T-D. and L.D-M.). We thank Keith A. Reimann for the anti-CD4 antibody used in these studies which was provided by the NIH Nonhuman Primate Reagent Resource supported by NIH grants OD010976 and AI126683.

REFERENCES

- 1.Levin MJ, Smith JG, Kaufhold RM, Barber D, Hayward AR, Chan CY, Chan IS, Li DJ, Wang W, Keller PM, Shaw A, Silber JL, Schlienger K, Chalikonda I, Vessey SJ, Caulfield MJ. 2003. Decline in varicella-zoster virus (VZV)-specific cell-mediated immunity with increasing age and boosting with a high-dose VZV vaccine. J Infect Dis 188:1336–1344. doi: 10.1086/379048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hess TM, Lutz LJ, Nauss LA, Lamer TJ. 1990. Treatment of acute herpetic neuralgia: a case report and review of the literature. Minn Med 73:37–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nagel MA. 2014. Varicella zoster virus vasculopathy: clinical features and pathogenesis. J Neurovirol 20:157–163. doi: 10.1007/s13365-013-0183-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Matoba AY, Meghpara B, Chevez-Barrios P. 2014. Varicella-zoster virus detection in varicella-associated stromal keratitis. JAMA Ophthalmol 132:505–506. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2013.8254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gilden D, Nagel MA. 2016. Varicella zoster virus triggers the immunopathology of giant cell arteritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol 28:376–382. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0000000000000292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gilden D, Nagel MA. 2016. Varicella zoster virus and giant cell arteritis. Curr Opin Infect Dis 29:275–279. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0000000000000258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nagel MA, Jones D, Wyborny A. 2017. Varicella zoster virus vasculopathy: the expanding clinical spectrum and pathogenesis. J Neuroimmunol 308:112–117. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2017.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carrascosa MF, Salcines-Caviedes JR, Roman JG, Cano-Hoz M, Fernandez-Ayala M, Casuso-Saenz E, Bascal-Carrera I, Campo-Ruiz A, Martin MC, Az-Perez A, Gonzalez-Gutierrez P, Aguado JM. 2014. Varicella-zoster virus (VZV) infection as a possible cause of Ogilvie’s syndrome in an immunocompromised host. J Clin Microbiol 52:2718–2721. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00379-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ioachim HL, Medeiros LJ. (ed). 2009. Varicella-herpes zoster lymphadenitis, p 92–94. In Lymph node pathology, 4th ed Lippincott/Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rifkind D. 1966. The activation of varicella-zoster virus infections by immunosuppressive therapy. J Lab Clin Med 68:463–474. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fehr T, Bossart W, Wahl C, Binswanger U. 2002. Disseminated varicella infection in adult renal allograft recipients: four cases and a review of the literature. Transplantation 73:608–611. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200202270-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Buchbinder SP, Katz MH, Hessol NA, Liu JY, O’Malley PM, Underwood R, Holmberg SD. 1992. Herpes zoster and human immunodeficiency virus infection. J Infect Dis 166:1153–1156. doi: 10.1093/infdis/166.5.1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Veenstra J, Krol A, van Praag RM, Frissen PH, Schellekens PT, Lange JM, Coutinho RA, van der Meer JT. 1995. Herpes zoster, immunological deterioration and disease progression in HIV-1 infection. AIDS 9:1153–1158. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199510000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Castro N, Carmagnat M, Kerneis S, Scieux C, Rabian C, Molina JM. 2011. Varicella-zoster virus-specific cell-mediated immune responses in HIV-infected adults. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 27:1089–1097. doi: 10.1089/AID.2010.0340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wroblewska Z, Valyi-Nagy T, Otte J, Dillner A, Jackson A, Sole DP, Fraser NW. 1993. A mouse model for varicella-zoster virus latency. Microb Pathog 15:141–151. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1993.1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tenser RB, Hyman RW. 1987. Latent herpesvirus infections of neurons in guinea pigs and humans. Yale J Biol Med 60:159–167. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sadzot-Delvaux C, Merville-Louis MP, Delree P, Marc P, Piette J, Moonen G, Rentier B. 1990. An in vivo model of varicella-zoster virus latent infection of dorsal root ganglia. J Neurosci Res 26:83–89. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490260110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lowry PW, Sabella C, Koropchak CM, Watson BN, Thackray HM, Abbruzzi GM, Arvin AM. 1993. Investigation of the pathogenesis of varicella-zoster virus infection in guinea pigs by using polymerase chain reaction. J Infect Dis 167:78–83. doi: 10.1093/infdis/167.1.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen JJ, Gershon AA, Li ZS, Lungu O, Gershon MD. 2003. Latent and lytic infection of isolated guinea pig enteric ganglia by varicella-zoster virus. J Med Virol 70(Suppl 1):S71–S78. doi: 10.1002/jmv.10325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Debrus S, Sadzot-Delvaux C, Nikkels AF, Piette J, Rentier B. 1995. Varicella-zoster virus gene 63 encodes an immediate-early protein that is abundantly expressed during latency. J Virol 69:3240–3245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kennedy PG, Grinfeld E, Bontems S, Sadzot-Delvaux C. 2001. Varicella-zoster virus gene expression in latently infected rat dorsal root ganglia. Virology 289:218–223. doi: 10.1006/viro.2001.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Willer DO, Ambagala AP, Pilon R, Chan JK, Fournier J, Brooks J, Sandstrom P, Macdonald DS. 2012. Experimental infection of cynomolgus macaques (Macaca fascicularis) with human varicella-zoster virus. J Virol 86:3626–3634. doi: 10.1128/JVI.06264-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meyer C, Engelmann F, Arnold N, Krah DL, ter Meulen J, Haberthur K, Dewane J, Messaoudi I. 2015. Abortive intrabronchial infection of rhesus macaques with varicella-zoster virus provides partial protection against simian varicella virus challenge. J Virol 89:1781–1793. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03124-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gray WL. 2004. Simian varicella: a model for human varicella-zoster virus infections. Rev Med Virol 14:363–381. doi: 10.1002/rmv.437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mahalingam R, Gilden DH. 2007. Simian varicella virus, p 1043–1050. In Arvin A, Campadelli-Fume G, Mocarski E, Moore PS, Roizman B, Whitley R, Yamanishi K (ed), Human herpesviruses: biology, therapy and immunoprophylaxis. Cambridge University Press, New York, NY. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Messaoudi I, Barron A, Wellish M, Engelmann F, Legasse A, Planer S, Gilden D, Nikolich-Zugich J, Mahalingam R. 2009. Simian varicella virus infection of rhesus macaques recapitulates essential features of varicella-zoster virus infection in humans. PLoS Pathog 5:e1000657. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Haberthur K, Engelmann F, Park B, Barron A, Legasse A, Dewane J, Fischer M, Kerns A, Brown M, Messaoudi I. 2011. CD4 T cell immunity is critical for the control of simian varicella virus infection in a nonhuman primate model of VZV infection. PLoS Pathog 7:e1002367. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mahalingam R, Traina-Dorge V, Wellish M, Lorino R, Sanford R, Ribka EP, Alleman SJ, Brazeau E, Gilden DH. 2007. Simian varicella virus reactivation in cynomolgus monkeys. Virology 368:50–59. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2007.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Traina-Dorge V, Sanford R, James S, Doyle-Meyers LA, de Haro E, Wellish M, Gilden D, Mahalingam R. 2014. Robust proinflammatory and lesser anti-inflammatory immune responses during primary simian varicella virus infection and reactivation in rhesus macaques. J Neurovirol 20:526–530. doi: 10.1007/s13365-014-0274-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Traina-Dorge V, Doyle-Meyers LA, Sanford R, Manfredo J, Blackmon A, Wellish M, James S, Alvarez X, Midkiff C, Palmer BE, Deharo E, Gilden D, Mahalingam R. 2015. Simian varicella virus is present in macrophages, dendritic cells, and T cells in lymph nodes of rhesus macaques after experimental reactivation. J Virol 89:9817–9824. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01324-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arnold NC, Meyer F, Engelmann F, Messaoudi I. 2017. Robust gene expression changes in the ganglia following subclinical reactivation in rhesus macaques infected with simian varicella virus. J Neurovirol 23:520–538. doi: 10.1007/s13365-017-0522-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mahalingam R, Kaufer BB, Ouwendijk WJD, Verjans GMGM, Coleman C, Hunter M, Palmer BE, Clambey E, Nagel MA, Traina-Dorge V. 2018. Attenuation of simian varicella virus infection by enhanced green fluorescent protein in rhesus macaques. J Virol 92:e02253-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Asanuma H, Sharp M, Maecker HT, Maino VC, Arvin AM. 2000. Frequencies of memory T cells specific for varicella-zoster virus, herpes simplex virus, and cytomegalovirus by intracellular detection of cytokine expression. J Infect Dis 181:859–866. doi: 10.1086/315347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mahalingam R, Traina-Dorge V, Wellish M, Deharo E, Singletary ML, Ribka EP, Sanford R, Gilden D. 2010. Latent simian varicella virus reactivates in monkeys treated with tacrolimus with or without exposure to irradiation. J Neurovirol 16:342–354. doi: 10.3109/13550284.2010.513031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yawn BP, Wollan PC, Kurland MJ, St Sauver JL, Saddier P. 2011. Herpes zoster recurrences more frequent than previously reported. Mayo Clin Proc 86:88–93. doi: 10.4065/mcp.2010.0618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Han X, Lundberg P, Tanamachi B, Openshaw H, Longmate J, Cantin E. 2001. Gender influences herpes simplex virus type 1 infection in normal and gamma interferon-mutant mice. J Virol 75:3048–3052. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.6.3048-3052.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mason RJ. 2006. Biology of alveolar type II cells. Respirology 11:S12–S15. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2006.00800.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ouwendijk WJ, Abendroth A, Traina-Dorge V, Getu S, Steain M, Wellish M, Andeweg AC, Osterhaus AD, Gilden D, Verjans GM, Mahalingam R. 2013. T-cell infiltration correlates with CXCL10 expression in ganglia of cynomolgus macaques with reactivated simian varicella virus. J Virol 87:2979–2982. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03181-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zukermann FA. 1999. Extrathymic CD4/CD8 double positive T cells. Vet Immunol Immunopathol 72:55–66. doi: 10.1016/S0165-2427(99)00118-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu T, Khanna KM, Chen XP, Fink DJ, Hendricks RL. 2000. CD8+ T cells can block herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV-1) reactivation from latency in sensory neurons. J Exp Med 191:1459–1466. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.9.1459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mott KR, Gate D, Matundan HH, Ghiasi YN, Town T, Ghiasi H. 2016. CD8 T cells play a bystander role in mice latently infected with herpes simplex virus 1. J Virol 90:5059–5067. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00255-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mahalingam R, Clarke P, Wellish M, Dueland AN, Soike KF, Gilden DH, Cohrs R. 1992. Prevalence and distribution of latent simian varicella virus DNA in monkey ganglia. Virology 188:193–197. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)90749-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mudd PA, Ericsen AJ, Price AA, Wilson NA, Reimann KA, Watkins DI. 2011. Reduction of CD4+ T cells in vivo does not affect virus load in macaque elite controllers. J Virol 85:7454–7459. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00738-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pahar B, Cantu MA, Zhao W, Kuroda MJ, Veazey RS, Montefiori DC, Clements JD, Aye PP, Lackner AA, Lovgren-Bengtsson K, Sestak K. 2006. Single epitope mucosal vaccine delivered via immunostimulating complexes induces low level of immunity against simian-HIV. Vaccine 24:6839–6849. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.06.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Traina-Dorge V, Pahar B, Marx P, Kissinger P, Montefiori D, Ou Y, Gray WL. 2010. Recombinant varicella vaccines induce neutralizing antibodies and cellular immune responses to SIV and reduce viral loads in immunized rhesus macaques. Vaccine 28:6483–6490. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.07.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Soike KF, Huang JL, Zhang JY, Bohm R, Hitchcock MJ, Martin JC. 1991. Evaluation of infrequent dosing regimens with (S)-1-[3-hydroxy-2-(phosphonylmethoxy) propyl]-cytosine (S-HPMPC) on simian varicella infection in monkeys. Antiviral Res 16:17–28. doi: 10.1016/0166-3542(91)90055-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]