Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) infects the majority of the world’s population, and although it typically establishes a quiescent infection with little to no disease in most individuals, the virus is responsible for a variety of devastating sequelae in immunocompromised adults and in developing fetuses. Therefore, identifying the viral properties essential for replication, spread, and horizontal transmission is an important area of medical science. Our studies use novel human salivary gland-derived cellular models to investigate the molecular details by which HCMV replicates in salivary epithelial cells and provide insight into the mechanisms by which the virus persists in the salivary epithelium, where it gains access to fluids centrally important for horizontal transmission.

KEYWORDS: HCMV, cytomegalovirus, horizontal dissemination, latency, lytic replication, organoid, salisphere, salivary gland

ABSTRACT

Various aspects of human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) pathogenesis, including its ability to replicate in specific cells and tissues and the mechanism(s) of horizontal transmission, are not well understood, predominantly because of the strict species specificity exhibited by HCMV. Murine CMV (MCMV), which contains numerous gene segments highly similar to those of HCMV, has been useful for modeling some aspects of CMV pathogenesis; however, it remains essential to build relevant human cell-based systems to investigate how the HCMV counterparts function. The salivary gland epithelium is a site of persistence for both human and murine cytomegaloviruses, and salivary secretions appear to play an important role in horizontal transmission. Therefore, it is important to understand how HCMV is replicating within the glandular epithelial cells so that it might be possible to therapeutically prevent transmission. In the present study, we describe the development of a salivary epithelial model derived from primary human “salispheres.” Initial infection of these primary salivary cells with HCMV occurs in a manner similar to that reported for established epithelial lines, in that gH/gL/UL128/UL130/UL131A (pentamer)-positive strains can infect and replicate, while laboratory-adapted pentamer-null strains do not. However, while HCMV enters the lytic phase and produces virus in salivary epithelial cells, it fails to exhibit robust spread throughout the culture and persists in a low percentage of salivary cells. The present study demonstrates the utility of these primary tissue-derived cells for studying HCMV replication in salivary epithelial cells in vitro.

IMPORTANCE Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) infects the majority of the world’s population, and although it typically establishes a quiescent infection with little to no disease in most individuals, the virus is responsible for a variety of devastating sequelae in immunocompromised adults and in developing fetuses. Therefore, identifying the viral properties essential for replication, spread, and horizontal transmission is an important area of medical science. Our studies use novel human salivary gland-derived cellular models to investigate the molecular details by which HCMV replicates in salivary epithelial cells and provide insight into the mechanisms by which the virus persists in the salivary epithelium, where it gains access to fluids centrally important for horizontal transmission.

INTRODUCTION

Seroepidemiological studies demonstrate that human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) infection is a worldwide medical threat, which is influenced by geography, age, and socioeconomic status (1, 2). Most healthy individuals harboring HCMV are asymptomatic; however, the virus is the leading infectious cause of birth defects, causes significant morbidity in immunocompromised patients, and has been implicated as a cofactor in the progression of cardiovascular disease and malignancies such as glioblastoma multiforme (3–6). During an initial infection, viral replication at the portal of entry is disseminated via a low-level primary viremia to multiple internal organs, including the spleen and liver (1). Robust replication in these organs and a secondary viremic phase disseminate virus throughout the host to distal tissues, including the salivary glands (7). Following primary infection, HCMV can persist in the salivary glands for several months, allowing for horizontal transmission to naive, uninfected individuals. Epidemiological studies have estimated that 20% of healthy children under the age of 5 years who attend day care are shedding HCMV in their saliva and may do so for up to 2 years (8, 9). It has also been reported that the rate of transmission from an HCMV-infected child to a susceptible mother is approximately 50% (10). Furthermore, as many mothers with young children will bear additional children, preventing HCMV transmission to expectant mothers remains a critical research goal. Defining the molecular mechanisms underlying HCMV infection and replication in human salivary cells and tissues will be crucial for future development of novel viral therapeutics that could be used to inhibit or reduce horizontal transmission, thereby lowering the incidence of disease.

The strict species specificity of HCMV and its inability to replicate in mouse models have severely restricted in vivo studies aimed at probing aspects of HCMV pathogenesis and spread within tissues important for transmission. However, murine cytomegalovirus (MCMV) infection of the mouse recapitulates some of the clinical and pathological features of HCMV infection (11, 12) and therefore has been viewed as a useful alternative for modeling general aspects of CMV pathogenesis. The MCMV model has generated insight into mechanisms of viral dissemination, persistence, and immune modulation and has provided an essential basis upon which to build hypotheses for subsequent testing in the context of HCMV (13–17).

The salivary glands of MCMV-infected mice, in particular, have been frequently used to model CMV persistence (1, 7, 18). Just as in humans, primary infection of MCMV is disseminated by blood monocytes to the salivary glands as a consequence of secondary viremia (19). Furthermore, Jonjic et al. reported that persistent MCMV was found specifically within the vacuoles of glandular acinar cells in the salivary gland (20). MCMV replication in glandular acinar cells leads to virus being shed into the acinar lumen, where it then spreads throughout the intricate ductal system connecting each acinus before eventually being shed into the saliva (7, 14).

The MCMV genome encodes several proteins that are not essential for replication in vitro but play important roles in viral replication and trafficking in vivo, including Sgg-1, MCK-2, M38.5, M45, and M33 (21–25). M33 is a member of the G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) superfamily and has been shown to have significant signaling activity in a number of cellular systems. M33 is not essential for replication in fibroblasts in tissue culture (13, 24, 26, 27) or in acute sites of infection in vivo, such as the spleen. However, M33 is essential for viral growth within the salivary gland in vivo (13, 24, 26–29). It remains unclear how M33 mechanistically facilitates MCMV growth in mouse salivary glands and whether HCMV-encoded viral GPCRs, such as UL33, UL78, or US28, are similarly required for HCMV growth in human salivary gland tissue. In vitro models of HCMV replication within salivary epithelial cells would prove invaluable in the identification of HCMV genes required for viral replication within the salivary gland.

MCMV infection and spread within the salivary gland have been examined at the anatomic and cellular levels by confocal microscopy using MCMVs expressing green fluorescent protein (GFP) (13). Interestingly, these microscopic studies indicated that MCMV fails to exhibit intra-acinar spread to adjacent cells, in contrast to what one observes in vitro with fibroblast cell monolayers. Rarely, can one detect more than one infected cell within each acinus, suggesting that the viruses do not spread across the epithelial tight junctions to adjacent cells as the infection proceeds. Interestingly, in a recent report by Mayer et al., human samples were used to demonstrate that HCMV infection of the oral epithelium results in inefficient spread of virus to adjacent cells, with each infected cell giving rise to <1.5 additional infected cells (30). Thus, in both the murine and human salivary glands, it appears that CMV exhibits limited spread, which may function to dampen extensive cytopathology and subsequent destruction of the salivary gland. Collectively, these data suggest that the cytomegaloviruses replicate and spread in the salivary/oral epithelium using a unique set of mechanisms, highlighting the need for a better understanding of the mechanisms and viral gene products used by HCMV to replicate within human cells and tissues such as those present in the salivary glands.

There are three major salivary glands in humans: parotid, submandibular, and sublingual. All three glands have the same basic architecture, including an arboreal ductal system that leads to the oral cavity and secretory bud-like acini that are responsible for producing various salivary components. The acini are surrounded by an elaborate network of extracellular matrix (ECM), myoepithelial cells, various immune cells, and endothelial cells. Studies aimed at developing human model systems, such as “salisphere”-derived primary salivary epithelial cells and salivary gland “organoids,” are of high interest to the medical research community. First, they would provide important insight into the physiology of this complex secretory tissue and allow for the development and testing of novel therapeutics that could be used to improve salivary flow in patients with salivary deficiencies such as Sjögren’s syndrome. Second, these cells could be organized into higher-order glandular structures and subsequently used for regenerative medical approaches aimed at restoring salivary gland function in patients. For example, standard treatment for head and neck cancers includes high-dose irradiation, which subsequently induces irreversible damage to the surrounding salivary glands. Thus, the potential of using salivary salispheres to restore salivary function in irradiated cancer patients is of particular interest. Tran et al. were among the first to develop a method to obtain primary salivary cells from human submandibular glands (31). They reported methodologies for culturing and expanding human salivary cells and demonstrated that they can form polarized tight epithelial barriers exhibited by the expression of genes such as the amylase, occludin, and claudin-1 genes (31). Others have used similar methodologies to culture primary salivary cells on Matrigel or other basement membrane extracts (BMEs) and successfully obtained cells that retained the necessary acinar phenotype (31–36).

The recent technical advances in tissue and cell engineering have presented new opportunities for investigating HCMV pathogenesis in vitro in cells and/or organoids derived from the salivary gland. In particular, the development of human primary salivary models could be used to facilitate our understanding of the mechanisms underlying HCMV entry, replication, and spread within the salivary gland. While murine models of MCMV infection have provided important insight into the mechanisms of cytomegalovirus replication in the salivary epithelium, it is critical to generate data in human systems to determine whether HCMV may use similar mechanisms. Our goal is to take advantage of the tissue engineering strategies currently in development to build a human model system appropriate for the investigation of the mechanisms underlying the replication and spread of HCMV in the salivary gland. In this study, we present data describing the development of such a system and demonstrate the utility of the system for assessing HCMV entry, replication, spread, and persistence.

RESULTS

Generation of human primary salivary explant cultures from fresh salivary tissue.

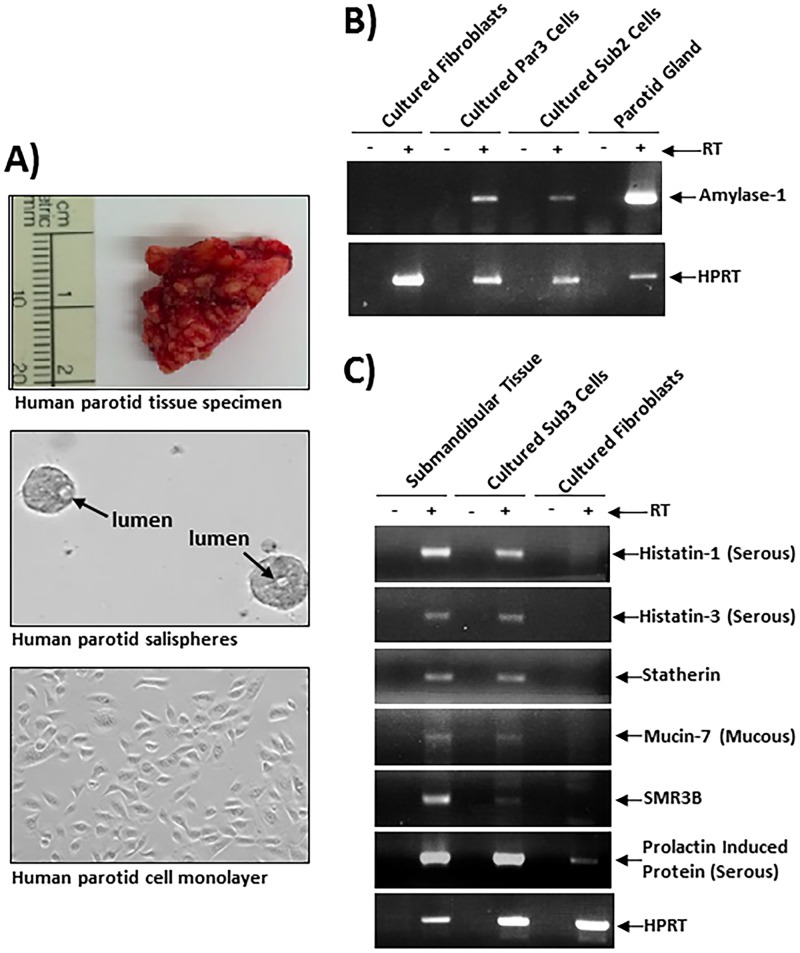

Parotid or submandibular salivary gland tissues from deidentified human subjects were delivered fresh to the laboratory following surgery for a variety of different head and neck cancers (Fig. 1A, top, depicts an image of a typical gland). In all cases, salivary tissue was derived from noncancerous tissue adjacent to the excised tumors. These samples varied in size and fat content, and when possible, one half of each sample was processed for the generation of a primary cell culture, while the other half was snap-frozen and saved for subsequent reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) analyses. To generate primary cell cultures, glandular tissue was mechanically sheared, digested enzymatically, and cultured on Cultrex PathClear BME gels (R&D Systems) supplemented with bronchial epithelial cell growth medium (BEGM; Lonza). After 2 to 3 days of growth, the isolated salivary cells readily formed round globules of cells, termed “salispheres,” that contained primitive glandular structures similar to those of an acinar lumen (Fig. 1A, middle). After 5 to 8 days of growth on BME gels, the salispheres were dissociated from the BME substrate and either replated onto freshly prepared BME gels and proliferated as salispheres or plated onto tissue culture-treated plates and proliferated as a monolayer. When grown on tissue culture-treated plastic, the cells exhibited a cuboidal phenotype typical of epithelial cells (Fig. 1A, bottom), in contrast to the rounded clumps of salispheres that can be readily observed on the BME gels (Fig. 1A, middle). The number of cell divisions that these primary gland-derived cells could successfully undergo varied from specimen to specimen and appeared to be dependent on the initial viability of the tissue and the subsequent efficiency of salisphere formation on BME gels. Typically, we were able to passage these salispheres 3 to 6 times on either fresh BME gels or plastic.

FIG 1.

Establishment of salispheres and primary epithelial lines from human salivary gland. (A) Freshly isolated salivary gland tissues (top) were digested with collagenase-dispase, and single-cell suspensions were then cultured on Cultrex PathClear basement membrane extract (BME) gels, where multicellular salispheres developed within 72 to 96 h (middle). Salispheres were then dissociated, counted, and replated onto Cultrex PathClear BME gels as in the middle panel or plated onto plastic culture dishes to facilitate HCMV infection experiments (bottom). (B) Salispheres were used for mRNA preparation and amylase 1 and hypoxanthine-guanine phosphotransferase (HPRT) expression. (C) Salispheres were then used for more-detailed analyses of salivary gland-specific gene expression. Taken together, the results indicate that the salispheres grown in vitro exhibit gene expression profiles similar to those of salivary tissue in vivo.

To confirm that the cultured primary salispheres were indeed derived from the salivary epithelium and not from contaminating cells such as fibroblasts or endothelial cells, we examined the expression of the salivary gland-specific α-amylase mRNAs in two independently derived salisphere lines, one derived from a parotid gland and one derived from a submandibular gland (Par3 and Sub2). α-Amylase is highly expressed in salivary acinar epithelial cells and is a major constituent of human saliva due to its secretion from these cells (37, 38). The expression of α-amylase mRNA could be seen clearly in freshly isolated glandular tissue and in salisphere cells grown on BME gels (Fig. 1B). We were unable to detect any amylase expression in primary human fibroblasts, confirming the specificity of the amylase expression assays. We then performed additional RT-PCR analyses on a third salisphere line derived from a submandibular gland (Sub3), and the analyses indicated that other salivary gland-specific genes, such as Statherin, Histatin-1 and -3, Mucin-7, and prolactin-induced protein (PIP), were expressed in the salivary gland-derived salispheres but not in normal human foreskin fibroblasts (Fig. 1C). It is interesting to note that the fresh parotid gland tissue appeared to express more α-amylase than did the salivary cells grown ex vivo (Fig. 1B). Perhaps this is due to the fact that the salivary gland tissue is exposed to the full cytokine/growth factor network present within the gland, while the salispheres represent a much more simplified in vitro system. Nevertheless, the ability of these primary epithelial cells to express α-amylase and other salivary gland-specific genes suggests that the primary cells in our model maintain a phenotype similar to that of acinar epithelial cells. Additional approaches, such as transcriptome sequencing (RNA-seq), will be necessary to further characterize these cells and determine how different growth conditions, such as basement membrane composition and the cytokine milieu, affect the cellular phenotype. Moreover, RNA-seq-type experiments would reveal if these cells exhibit more of a mucous or serous phenotype and if they exhibit any characteristics of the closely related ductal epithelial cells.

A low-passage-number clinical HCMV isolate and HCMV-TB40E efficiently infect human primary salivary cells, while HCMV-FIX and HCMV-AD169 infect with a much-reduced efficiency.

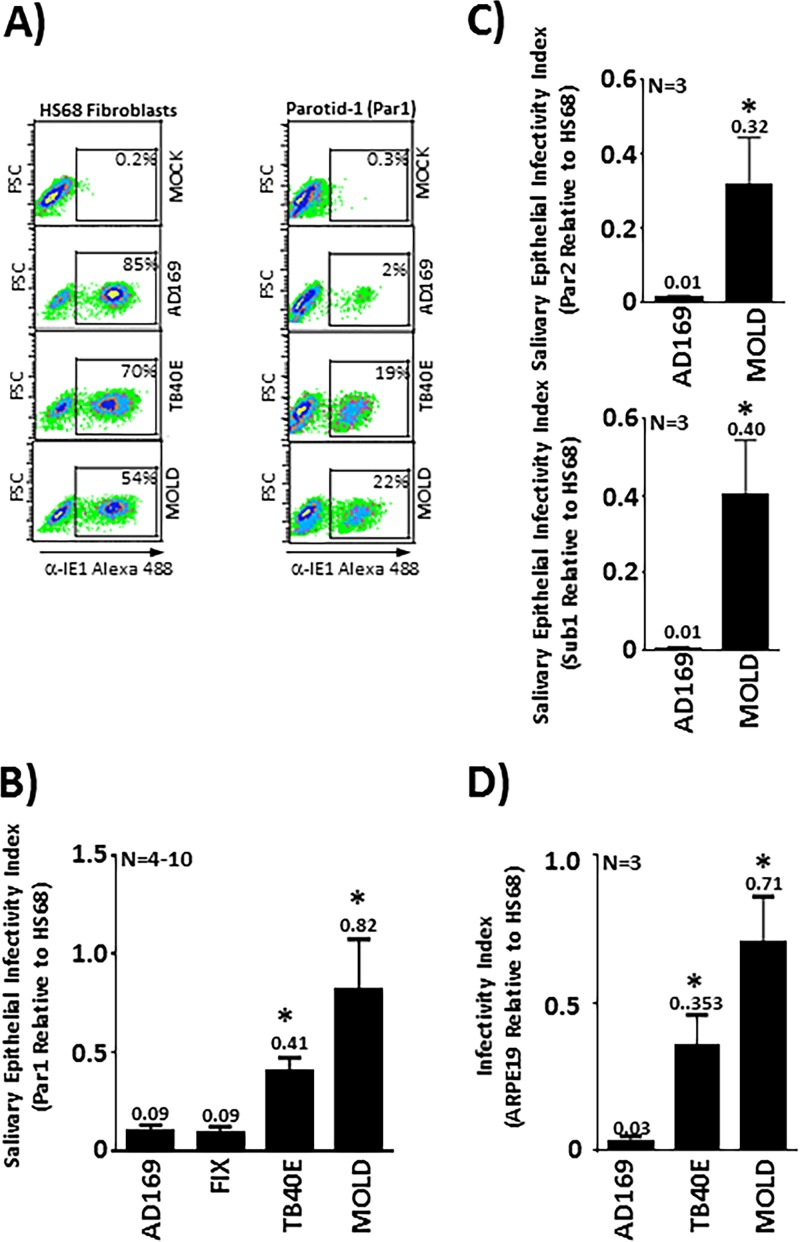

We next explored the ability of a panel of HCMV strains to infect human primary salivary cells and used flow cytometric detection of immediate early (IE) gene expression at 48 h postinfection as our measure of infection. This quantitative methodology enabled us to assess the relative ability of each of the different virus strains to enter and initiate viral gene expression in salivary cells and to compare this to their ability to enter and initiate IE expression in HS68 fibroblasts. Strains included a primary low-passage-number HCMV isolate, MOLD, and the widely utilized HCMV strains TB40E, FIX, and AD169. Of the widely utilized strains, only TB40E is known to retain expression levels of the gH/gL/UL128/UL130/UL131A (pentamer) glycoprotein complex adequate for efficient epithelial cell entry (39–42). Fibroblasts (HS68) or salivary epithelial cells (Par1) grown as monolayers in 12-well plates (100,000 cells per well) were infected with each virus strain at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 1. This MOI was based on virus titers obtained from plaque assays in HS68 fibroblasts. These virus strains exhibited the expected infectious capacities in fibroblasts, ranging from 54% for the MOLD clinical strain to 85% for the laboratory-adapted AD169 strain (Fig. 2A, left). Interestingly, in the primary parotid line Par1, the pentamer-positive TB40E strain and the low-passage-number MOLD strain retained the ability to enter cells and initiate replication, while the high-passage-number laboratory-adapted strain AD169 infected cells very poorly (Fig. 2A, right). We calculated the relative ability of each virus strain to enter and initiate replication in Par1 parotid cells relative to HS68 fibroblasts and report this as a “salivary epithelial infectivity index” in Fig. 2B. These analyses revealed that the AD169 and FIX strains infected Par1 cells with low efficiency, each exhibiting Par1/HS68 ratios of 0.09. The TB40E and MOLD viruses infected Par1 cells more efficiently, with Par1/HS68 ratios of 0.41 and 0.82, respectively. To determine if other salivary gland-derived cell lines responded similarly, we chose two others from our collection, including another parotid line (Par2) and a submandibular line (Sub1). Both of these lines produced results similar to those obtained in Par1 cells, with AD169 exhibiting Par2/HS68 and Sub1/HS68 ratios of 0.01 in both lines and MOLD exhibiting a Par2/HS68 ratio of 0.32 and a Sub1/HS68 ratio of 0.40. (Fig. 2C). Finally, we performed a similar experiment with the APRE19 epithelial cell line, which is frequently used as a model for HCMV infection of epithelial cells. The ARPE19 cells exhibited infectivity indices similar to those of the salivary lines in that AD169 exhibited an ARPE19/HS68 ratio of 0.03, and TB40E exhibited an ARPE19/HS68 ratio of 0.35, while MOLD maintained the highest index, exhibiting an ARPE19/HS68 index of 0.71. These data indicate that primary salivary cells are infected by HCMV using a mechanism(s) that would be expected for a primary epithelial line in that they require the pentamer complex and late-passage laboratory strains like AD169 fail to infect these primary lines and initiate IE gene expression.

FIG 2.

Low-passage-number clinical HCMV isolates and TB40E efficiently infect primary salivary cells and initiate IE gene expression. (A) Primary salivary epithelial cells (Par1) or HS68 fibroblasts were infected at an MOI of 1 with various HCMV strains, including the low-passage-number clinical isolate MOLD and the laboratory strains TB40E and AD169. Cells were analyzed for IE expression by flow cytometry to determine the percentage of cells that become infected and enter the immediate early phase. FSC, forward scatter. (B) Experiments performed as described above for panel A are presented quantitatively as the relative ability of each strain to infect parotid gland-derived salivary cells compared to its ability to infect HS68 fibroblasts. (C) Comparison of AD169 and MOLD infections in two additional salivary lines (one parotid and one submandibular) demonstrates that similar results are obtained in multiple lines. (D) Determination of relative infectivity, calculated as described above for panel B, was repeated using the ARPE19 epithelial line to allow comparisons between primary salivary lines and an immortalized epithelial line often used in HCMV studies. Values above the error bars in panels B to D represent the ability of each strain to infect epithelial cells relative to fibroblasts. *, P < 0.05 compared to AD169, as determined by unpaired Student’s t tests.

Infection of primary human salivary epithelial cells proceeds through all three phases of the lytic cycle and results in de novo release of virus into the culture medium.

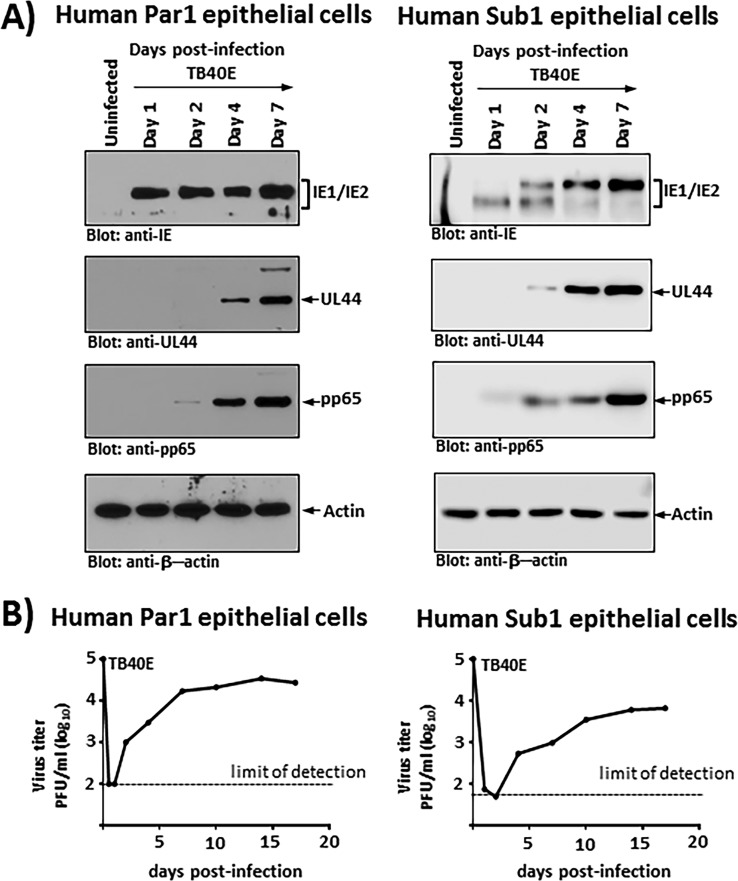

To analyze the temporal nature of HCMV infection in salivary cells in vitro and determine how far the infection proceeds into the lytic phase in this cellular context, we used Western blotting to examine the expression of HCMV gene products representative of each of the three lytic phases. We examined the expression of HCMV proteins typical of the immediate early (IE72), delayed early (UL44), and late (pp65) stages. IE72 plays a major role in the activation of early viral gene expression and has been suggested to bind to a variety of cellular proteins to mediate its effect. UL44 is a phosphoprotein that is essential for HCMV DNA replication and serves as a processivity subunit of the viral DNA polymerase (43). pp65 is a tegument protein that functions to downregulate interferon responsiveness and impair immune cell recognition of infected cells (44, 45).

Figure 3A illustrates viral gene expression profiles over a 7-day time course in two different salisphere lines (one parotid and one submandibular) infected with TB40E at an MOI of approximately 1.0 (based on HS68 fibroblast titers). These profiles demonstrated a typical onset of HCMV lytic infection, with IE gene expression appearing by 24 h postinfection and delayed early and late gene expression initiating approximately 48 to 96 h after infection. Moreover, similar results were obtained in the parotid gland-derived line Par1 (Fig. 3A, left) and in the submandibular gland-derived line Sub1 (Fig. 3A, right). Importantly, these data confirm that the salivary cells are indeed infected with HCMV and indicate that the infection can proceed through all three phases of the lytic cascade.

FIG 3.

Human salivary cells infected with HCMV-TB40E are able to support all phases of HCMV lytic gene expression and release nascent virus into the culture medium. (A) Human parotid gland-derived (left) or submandibular gland-derived (right) salivary epithelial cells were infected with TB40E at an MOI of 1, and cell extracts were prepared at the indicated time points. Replicate Western blots prepared with these infected cell extracts were then probed with anti-CMV IE1/IE2 (Chemicon), anti-UL44 (12G5), anti-pp65 (Virusys), and β-actin antibody (Bethyl Laboratories). (B) Human parotid gland-derived (left) or submandibular gland-derived (right) salivary epithelial cells were infected with TB40E at an MOI of 0.1, the culture supernatant was isolated at the indicated times postinfection, and the titers were subsequently determined on HS68 fibroblasts. The growth curves depicted in panel B are representative of data from multiple independent experiments, each performed in duplicate.

Next, we examined virus growth in a multistep growth assay following infection of Par1 and Sub1 cells at an MOI of 0.1. At 24 h postinfection, the initial inoculum was removed, and cell monolayers were washed vigorously to remove unbound input virus. The cellular supernatant was then harvested at time points out to 17 days postinfection and examined for nascent virus particles by assays on HS68 fibroblast monolayers. Figure 3B, left, depicts a growth curve for the TB40E virus in Par1 parotid primary epithelial cells, while Fig. 3B, right, depicts a growth curve for the TB40E virus in Sub1 submandibular epithelial cells. It is clear from the data that (i) the infected salivary cells produce nascent infectious virus, (ii) the concentration of virus in the culture plateaus at a relatively low level of approximately 104 PFU/ml by about 7 days postinfection, and (iii) once the virus plateaus, it persists at that level for the remainder of the experiment. Visual inspection of the cell monolayers indicated that there is some cytopathic effect (CPE), but it is evident that the infection did not spread or lead to complete destruction of the monolayer, as it did in fibroblasts, where the virus titers in the supernatant typically reach levels of 106 PFU/ml or higher (data not shown). Thus, while HCMV enters the lytic phase and produces nascent viral particles following infection of salivary epithelial cells, the outcome and underlying properties of the virus interaction with the salivary cells are quite distinct from those observed in fibroblasts.

Primary human salivary epithelial cells do not support efficient HCMV spread.

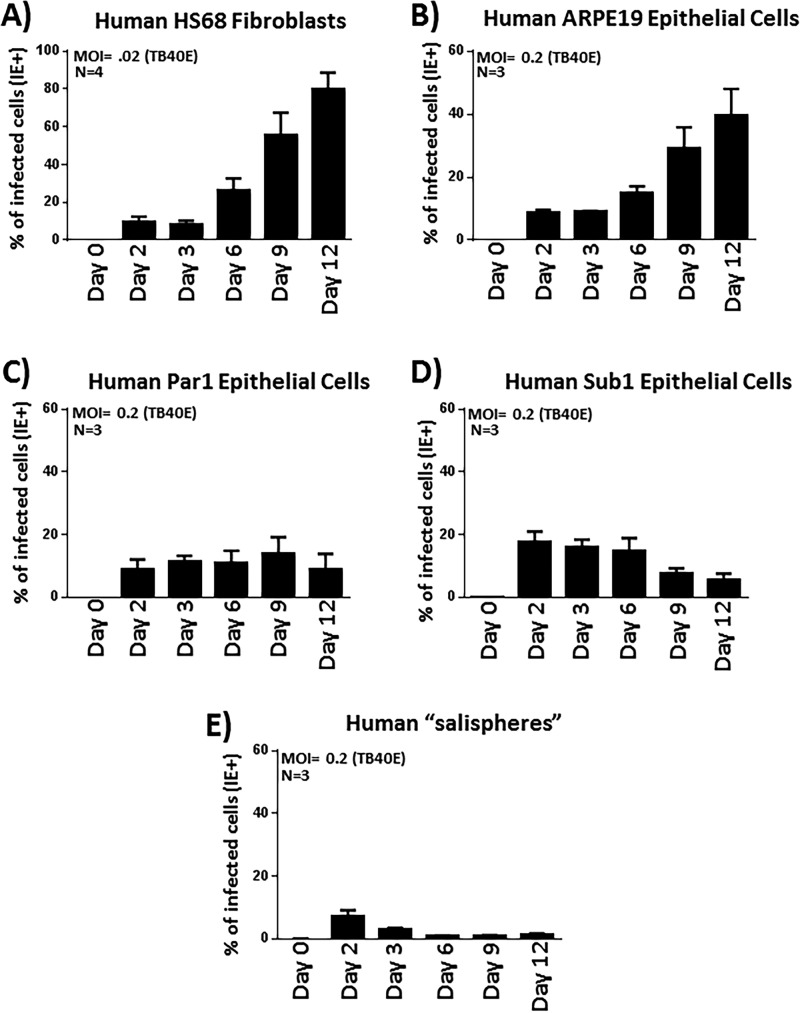

Based on our observations regarding viral gene expression (Fig. 3A) and the early plateauing of virus titers in the culture media (Fig. 3B), it appeared that HCMV does not spread efficiently throughout these salivary epithelial cultures. Instead, it appeared to undergo a restricted or delimited type of infection, possibly persisting for an extended period of time in a small subset of cells. To investigate HCMV spread in salivary cells and to compare this level of spread to that typically observed in fibroblasts and ARPE19 epithelial cells in vitro, a flow cytometric approach was undertaken, in which we examined the fraction of each cell type infected with HCMV over a 12-day time course. This quantitative approach allowed us to assess the percentage of cells infected at specific times postinfection and to deduce how the virus spreads. Following infection of HS68 fibroblasts and examination of HCMV IE gene expression at the indicated time points (days 2, 3, 6, 9, and 12), we observed time-dependent increases in the frequencies of HCMV-positive cells from 5% to 90% (Fig. 4A). From these data, we confirmed that HS68 fibroblasts produce nascent virus that efficiently spreads to other cells within the culture vessel. Previous reports indicate that this spread would presumably occur via cell-to-cell contacts and also through the release and spread of virus via an extracellular route (46, 47). Viral spread occurred quickly in fibroblasts, and by the last time point (day 12), the monolayer was essentially destroyed, indicative of complete CPE in the culture (data not shown). We also performed experiments in the established epithelial cell line ARPE19, and similar to what we observed in HS68 fibroblasts, we found that TB40E efficiently spread throughout the ARPE19 monolayer, culminating in 50% of the cells exhibiting IE gene expression by day 12 postinfection (Fig. 4B). O’Connor and Shenk reported that TB40E spread in ARPE19 cells occurs exclusively via a cell-to-cell route due to low levels of virus released into the culture supernatant (47).

FIG 4.

Primary salivary epithelial cells do not facilitate efficient HCMV-TB40E spread. (A) HS68 fibroblasts were infected with TB40E at an MOI of 0.02, and the percentages of IE+ cells were quantified at the indicated time points postinfection by IE staining and flow cytometry. (B) ARPE19 cells were similarly infected but at an MOI of 0.2 and analyzed as described above for panel A. (C) Parotid gland-derived epithelial cells were infected as described above for panel A with TB40E at an MOI of 0.2 and similarly analyzed by flow cytometry for IE expression at various times postinfection. (D) Submandibular gland-derived epithelial cells were infected as described above for panel A with TB40E at an MOI of 0.2 and similarly analyzed by flow cytometry for IE expression at various times postinfection. (E) Salivary cell salispheres grown as clusters on BME gels were infected as described above for panel A with TB40E at an MOI of 0.2 and similarly analyzed by flow cytometry for IE expression at various times postinfection.

Next, we wanted to examine HCMV spread in primary salivary epithelial cells. Par1 parotid salivary cells (Fig. 4C) or Sub1 submandibular salivary cells (Fig. 4D) were infected with HCMV-TB40E at an MOI of 0.2 and assayed by flow cytometry at days 2, 3, 6, 9, and 12 postinfection. Using TB40E, we observed that approximately 10 to 20% of the salivary cells were infected by day 2 postinfection, as evidenced by them expressing IE proteins. In sharp contrast to what we observed in HS68 fibroblasts and ARPE19 cells, we found that the virus failed to spread throughout the salivary epithelial monolayer. At between 2 and 12 days postinfection, the percentage of infected cells either remained relatively constant or decreased somewhat (Fig. 4C and D). Increasing the MOI to promote initial infections of approximately 40 to 50% of cells did not increase the likelihood of spread throughout the culture, as the percentage of infected cells at the day 12 time point remained roughly the same as that observed at days 2 to 3 postinfection (data not shown). While the relatively low titers of virus released into the supernatant (Fig. 3B) could severely limit the spread of virus via an extracellular route, the results are interesting and distinct from those observed in ARPE19 cells, as it is also clear that the virus fails to spread in salivary cells via a route involving cell-to-cell contact.

We then sought to examine HCMV spread in salivary cells maintained as salisphere clusters on PathClear BME gels (Fig. 4E). Similar to what we observed in salivary cells grown as monolayers, while the virus was able to infect and initiate viral gene expression in the salispheres, the virus fails to spread throughout the clusters, and the percentage of infected cells in fact declined throughout the time course studied. This experiment further supports the conclusion that the virus fails to spread in a cell-to-cell fashion in these cells, as the salispheres contain 10 to 20 cells each and provide numerous contact points that would allow direct cell-to-cell spread.

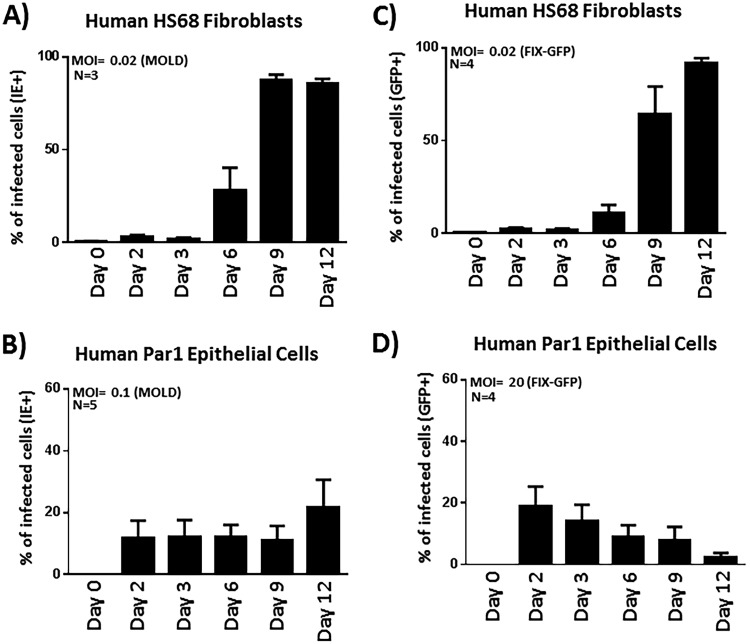

We tried a similar experiment using two additional HCMV strains: MOLD, which exhibits a fairly high salivary epithelial cell infectivity rate, and FIX, which exhibits a reduced salivary epithelial infectivity rate. Importantly, we found that while HCMV-MOLD and HCMV-FIX-GFP efficiently spread in HS68 fibroblasts (Fig. 5A and C), both strains failed to spread in salivary epithelial cells (Fig. 5B and D). We used a much larger amount of input FIX virus (MOI = 20) in this experiment, as HCMV-FIX has a relatively poor ability to infect salivary epithelial cells via the extracellular route (Fig. 2B). Moreover, in the HCMV-FIX experiments, we used an alternate detection method in that we tracked the expression of GFP, which is expressed following infection irrespective of whether or not the virus enters the lytic phase. Taken together, the data from salivary epithelial cells indicate that HCMV fails to exhibit cell-to-cell or extracellular spread and that the failure to spread is independent of the virus strain used.

FIG 5.

HCMV-MOLD and HCMV-FIX similarly fail to spread throughout salivary epithelial cells. (A and C) The MOLD (A) or FIX (C) strain of HCMV was used to infect HS68 fibroblasts, and spread was measured by flow cytometry using IE expression (MOLD) or GFP expression (FIX) as a marker. Using a starting MOI of 0.02, the virus quickly and efficiently spreads throughout the culture, reaching a CPE level of close to 100% by day 12 postinfection. (B and D) Human parotid salivary epithelial cells were similarly infected with HCMV-MOLD at an MOI of 0.1 or HCMV-FIX-GFP at an MOI of 20. A high MOI for FIX was used as this strain infects Par1 cells relatively poorly. Spread was measured by flow cytometric analyses of IE or GFP expression as described above for panels A and C.

The failure to spread rapidly throughout the culture leads to the development of a low-level “persistent” infection in human salivary cells.

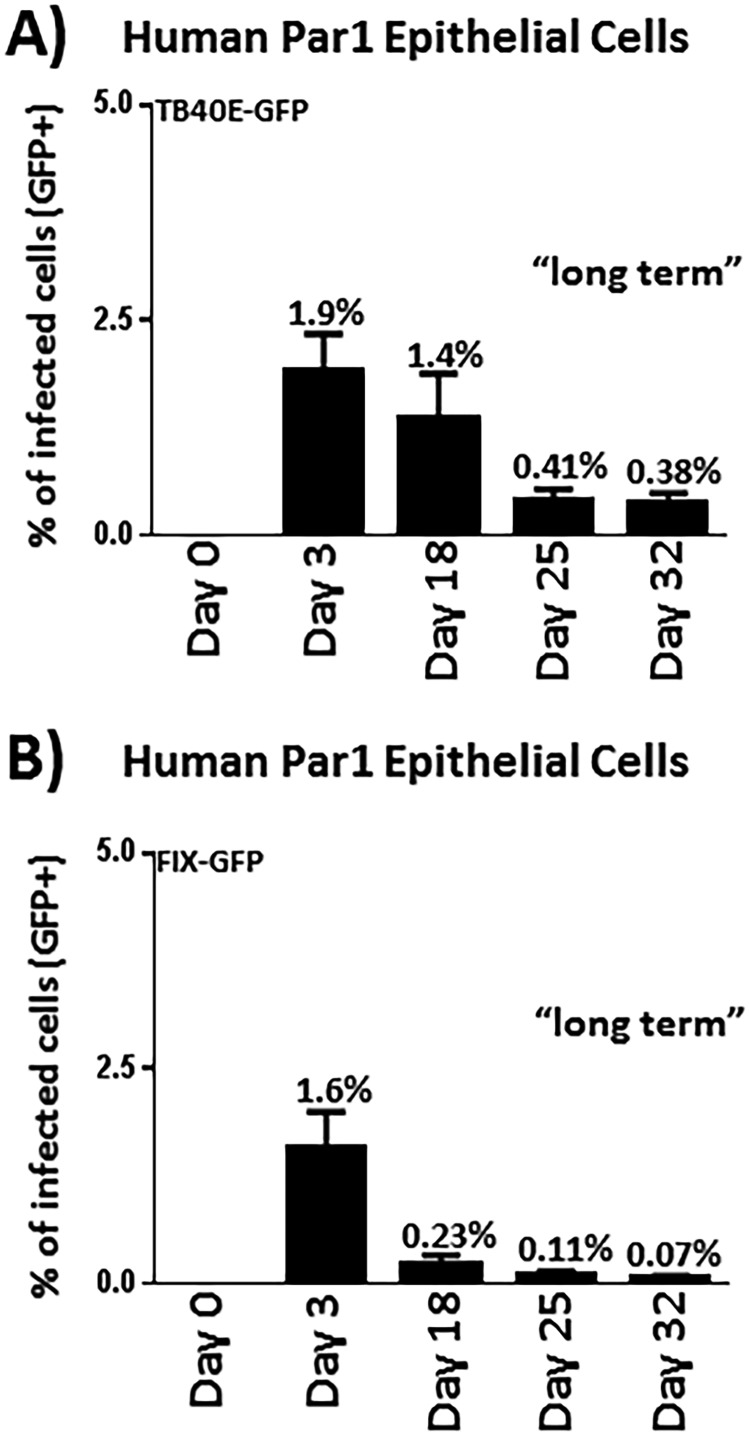

While HCMV did not appear to spread efficiently in salivary epithelial cells, the cultures maintained a low percentage of infected cells, even after 12 days postinfection (Fig. 4C to E and Fig. 5B to D). Thus, we pursued a long-term experiment using the TB40E-GFP and FIX-GFP virus strains (Fig. 6A and B). The TB40E-GFP virus expresses GFP as a pp150-GFP fusion protein, and the FIX-GFP virus constitutively expresses GFP from a simian virus 40 (SV40) cassette (47, 48). These viruses provide useful tools that enable us to ascertain the fate of the virus-infected cells over the long term and determine if the infection persisted for an extended period of time in a small percentage of cells. Par1 parotid epithelial cells were infected with TB40E-GFP (Fig. 6A) or FIX-GFP (Fig. 6B), and cells were analyzed for GFP expression by flow cytometry out to 32 days postinfection. Interestingly, we were able to detect HCMV-infected cells out to at least 32 days postinfection. At 25 and 32 days postinfection, we were able to detect HCMV-positive cells at frequencies of approximately 0.4% (1:250) with TB40E-GFP and at frequencies of approximately 0.1% (1:1,000) with FIX-GFP. It remains unclear why the virus would persist in a small percentage of cells but fail to spread within the population. We hypothesize that once infected, the parotid gland cells die and detach from the monolayer before the virus is able to efficiently infect adjacent cells. The consequence of rapid cell death could prevent the infection from spreading efficiently throughout the culture, leading to an effective decline in the percentage of detectable infected cells over the time course studied. In such a scenario, the virus would be able to maintain a low-level persistent infection in roughly 1:1,000 cells before eventually being lost from the system or becoming stabilized in an extremely low percentage of cells.

FIG 6.

The failure of HCMV to robustly and efficiently spread in salivary epithelial cell cultures results in a low-level persistent infection. Parotid primary epithelial cells were infected with the TB40E-GFP virus at an MOI of 0.1 to 0.5 (A) or with the FIX-GFP virus at an MOI of 1 to 5 (B) and harvested at the indicated time points. At each time point, the percentage of infected cells was tabulated by calculating the percentage of cells expressing GFP. Analysis of GFP expression enables the determination of the number of infected cells remaining in this “persistent” state. Cells were fed with fresh medium every 3 to 4 days. The overall viability of the cultures remained high based on basic analyses of flow cytometric analysis of forward scatter (FSC) and side scatter (SSC). The data depicted in panels A and B were derived from 4 or more independent experiments.

Parotid cells infected with HCMV undergo extensive cellular death, providing a potential explanation for the failure of HCMV to spread efficiently throughout the parotid cultures.

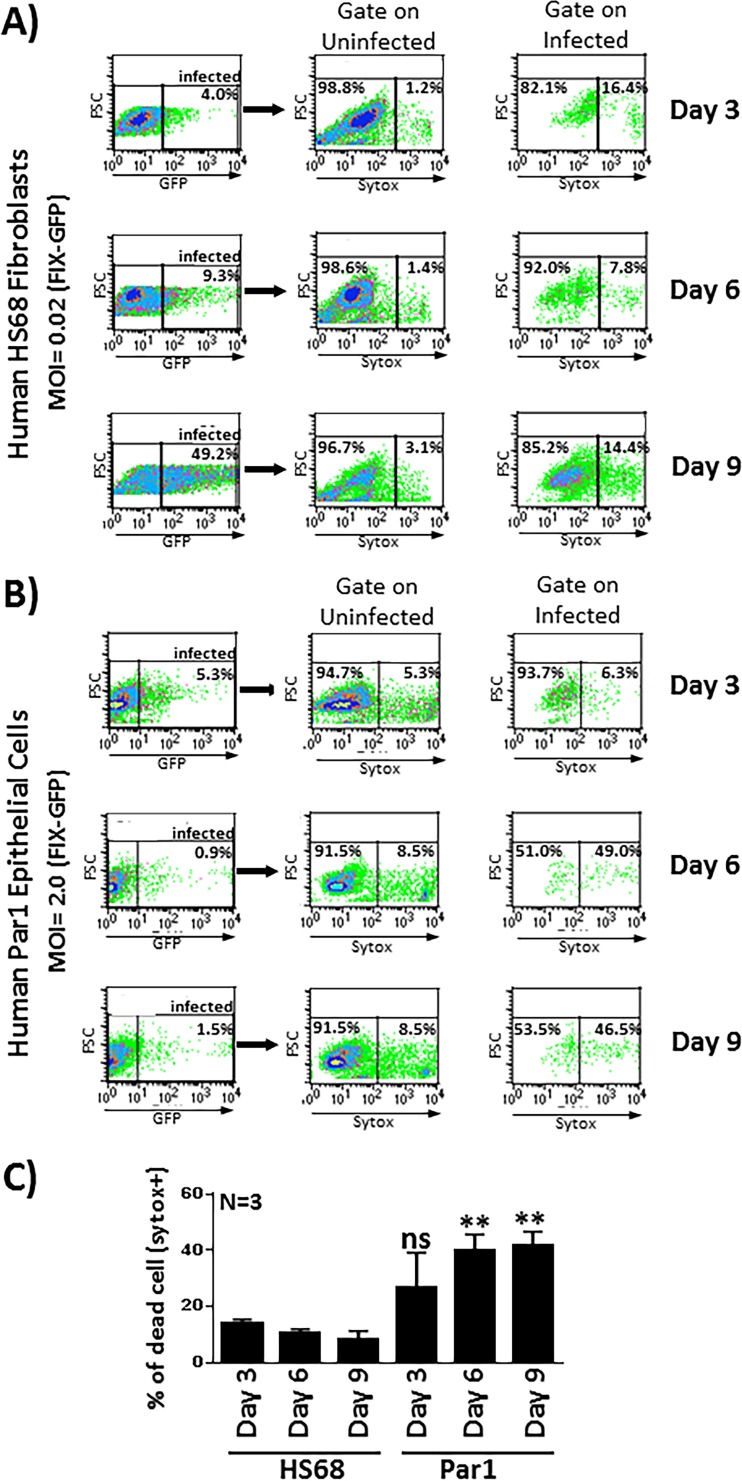

To investigate the health of salivary epithelial cells following HCMV infection and potentially gain insight into the subsequent failure of HCMV to spread efficiently throughout the salivary cultures, we investigated the viability of HS68 fibroblasts and parotid salivary epithelial cells out to 9 days postinfection. Cells were infected with FIX-GFP (to facilitate gating on GFP-positive [GFP+] infected cells) and then stained with a cell viability stain, SYTOX orange, which enabled quantitative analyses of cellular viability in flow cytometry assays. The ability to gate specifically on GFP+ infected cells enabled us to compare the viabilities of noninfected and HCMV-infected cells side by side within the same culture vessel.

We initially performed experiments in HS68 fibroblasts to establish the parameters necessary for flow cytometric analyses of cell death in uninfected and infected cells. As we observed previously, the percentage of FIX-GFP-infected HS68 fibroblast cells increased with time between days 3 and 9 postinfection, reflecting the efficient spread of the virus through the culture (Fig. 7A, left). When gating on uninfected HS68 fibroblasts, the percentage of cell death as revealed by SYTOX staining remained low, in the range of 1.2% to 3.1%, indicating that the uninfected cells remained healthy, as expected (Fig. 7, middle). When gating on infected cells, the percentage of cell death remained relatively low, in the range of 7.8% to 16.4%, indicating that the infected HS68 fibroblasts maintained high viability out to day 9 postinfection despite harboring actively replicating virus (Fig. 7A, right, and Fig. 7C). This was to be expected, as it is well known that infected fibroblasts remain tightly adhered to the culture vessel for a significant period of time before eventually detaching and succumbing to the infection. Analyses of SYTOX staining at later time points supported this notion, as the cells became highly SYTOX positive after detachment (data not shown).

FIG 7.

HCMV-infected primary salivary cells exhibit extensive cell death following infection. (A) HS68 fibroblasts were infected with the FIX-GFP virus at an MOI of 0.02, and the percentage of infected cells was tracked by flow cytometry using GFP expression as a marker of infected cells (left). At each time point, cells were then stained with SYTOX orange for analyses of cell viability. Cells from each time point were gated such that cellular viability could be examined in both uninfected (middle) and infected (right) cell populations. For example, at the day 9 time point, when gating on uninfected GFP-negative cells, 96.7% of the cells were viable and SYTOX negative, while 3.1% of the cells were dead and SYTOX positive. At the day 9 time point, when gating on infected GFP+ cells, 85.2% of the cells were viable and SYTOX negative, while 14.4% of the cells were dead and SYTOX positive. (B) Primary salivary epithelial cells were infected with the FIX-GFP virus at an MOI of 2.0, and the percentage of infected cells and viability of uninfected and infected cell populations were assessed as described above for panel A. (C) Data from three independent experiments performed in duplicate are shown in graphical form. Cell death in Par7 cells was compared to cell death in HS68 cells at each time point for statistical analyses. **, P < 0.01 for comparison of Par7 cells to HS68 cells, as determined by unpaired Student’s t tests. ns, nonsignificant.

Next, we used this experimental paradigm and performed a similar analysis in primary Par1 parotid salivary cells. Cells were infected with FIX-GFP at an MOI of 2.0, and, as expected from previous experiments, the percentage of infected salivary cells dropped from an initial 5.3% infected at day 3 postinfection to 1.5% at day 9 postinfection (Fig. 7B, left). When gating on uninfected salivary cells, the percentage of cell death remained relatively low, in the range of 5.3% to 8.5%, throughout the time course. Although this percentage was somewhat higher than that observed in HS68 fibroblasts, it indicated that the uninfected cells remained healthy, as expected (Fig. 7B, middle). Analyses of the viability of the infected salivary cells revealed a stark contrast to that of the HS68 fibroblasts. By day 6 postinfection, the percentage of SYTOX-positive cells was 49.0%, remaining high at 46.5% at day 9 postinfection (Fig. 7B, right, and Fig. 7C). Thus, while the infected HS68 fibroblasts retained a high level of viability out to day 9 postinfection, the salivary cells exhibited extensive cell death. These data suggest that the failure of the virus to spread within the salivary cell cultures could be due in part to the failure of the infected cells to maintain a level of cellular metabolic health necessary to facilitate appropriate levels of virus production. It will be interesting to evaluate salivary cell viability at very late time points (32 days postinfection or later) to determine if the small number of infected cells continue to demonstrate hallmarks of low viability. Such a finding could suggest that newly infected cells are consistently arising in the population. Alternatively, it could suggest that a small percentage of cells adapt to retain high levels of viability, thereby allowing the virus to persist in a small percentage of cells. Either or both scenarios would result in a very small number of infected cells being retained in the cultures.

DISCUSSION

Building on the work of several groups whose studies were aimed at developing salivary cell systems for restoration of glandular function in cancer or Sjögren’s syndrome patients (34–36, 49–51), we developed an analogous system that can be used to systematically analyze HCMV replication and spread within salivary cells in vitro. We found that primary salispheres readily formed when fresh salivary gland tissue (parotid or submandibular) was viably dissociated into single cells and subsequently cultured on Cultrex PathClear BME gels. We subsequently determined that the cells contained within these salispheres exhibit gene expression profiles very similar to those of salivary glands in vivo. This methodology has enabled us to generate more than 40 primary salisphere-derived cell lines from a variety of glands.

Once these salisphere cell lines were established, we initiated experiments aimed at evaluating HCMV infection/replication to determine if they exhibited infection parameters similar to or distinct from those observed in established epithelial lines such as ARPE19 or RPE-1. Initially, we tested the abilities of various HCMV strains to enter cells and initiate replication. Our data indicated that the TB40E laboratory strain and the low-passage-number clinical isolate MOLD infected the parotid cells much more efficiently than did the AD169 or FIX strain. The TB40E and MOLD strains retain the pentamer-encoding region of the genome, whereas the laboratory-adapted AD169 strain of HCMV does not, findings which are consistent with the requirement of the UL128, UL130, and UL131A pentamer proteins for salivary epithelial cell entry (39, 40, 52, 53). FIX poorly infected primary salivary epithelial cells in our studies, likely due to a single nucleotide substitution in the UL130 gene, which concomitantly reduces the levels of UL128 in the virion (42). There are multiple interesting facets to our findings. The first is that the HCMV entry data confirm the epithelial nature of the salivary salisphere-derived cells, and the second is that the data indicate that the conclusions drawn from established epithelial cell lines, such as ARPE19 and RPE-1, regarding viral entry and pentamer dependence appear to correlate well with the mechanism(s) involved in HCMV entry into primary salivary cells. Our model system provides a biologically relevant system in which to further explore the molecular mechanisms underlying pentamer-mediated entry into and infection of primary salivary epithelial cells.

Following deposition of the HCMV genome into the salivary cells and initiation of the immediate early phase, the initially infected cells proceed through the latter phases of lytic gene expression, and low levels of newly synthesized virus particles are released into the culture medium. However, HCMV did not readily spread and disseminate throughout the monolayer of primary salivary gland cells. This is in sharp contrast to what is observed in HS68 fibroblasts or in ARPE19 and RPE-1 cells (Fig. 4 to 6) (42, 47). In ARPE19 cells, HCMV reportedly spreads predominantly via a cell-to-cell route. In contrast, in primary salivary cells, we observe a static percentage of infected cells over the time course of infection, and the virus is incapable of overwhelming the cells and generating a high level of CPE, even out to 30 days postinfection. Our analyses of cell viability following HCMV infection provide a possible explanation regarding the failure of the virus to efficiently spread from cell to cell as it does in ARPE19 cells. In HS68 fibroblasts, cell viability remained high (>85% viable) out to 9 days postinfection as the infection progressed through the culture. In contrast, in primary salivary epithelial cells, viability quickly deteriorated (<50% viable) by day 9 postinfection, and the infection failed to progress through the culture. Taken together, the results of these studies indicate that infection of primary salivary epithelial cells proceeds in a self-limiting fashion and that the virus does not readily spread to adjacent cells in the culture as it does in lytically infected fibroblast or ARPE19 lines. It is possible that once the salivary gland cells become infected, they rapidly begin to apoptose, thereby preventing the high titers of virus necessary to infect the surrounding uninfected cells in the culture. Moreover, it should be noted that the frequently used ARPE19 epithelial cell line exhibits a phenotype more closely related to that of HS68 fibroblasts than that observed in primary salivary epithelial cells. Thus, while ARPE19 cells exhibit the necessary dependence on pentamer-containing virions for entry and establishment of infection, care should be taken when interpreting additional infection parameters. Using ARPE19 cells to study aspects of HCMV spread or mechanisms of virus production may not provide a clean glimpse into the biology underlying HCMV-epithelial cell interactions due to their long-term extended growth in culture or other contributing factors.

The failure of HCMV to spread to adjacent cells, even in a direct cell-to-cell manner, within primary salivary cultures is reminiscent of data reported by Bittencourt et al., who noted that MCMV spread within the murine submandibular gland also occurred in a restricted, more limited fashion (13). In the MCMV studies, rarely can one find a salivary acinus in which more than one cell is infected. Since the individual acinar units are typically comprised of >20 cells, it appears that MCMV does not spread from cell to cell within each acinus but perhaps spreads in an interacinar fashion (one acinus to another) after virus is secreted into the acinar lumen and then into the salivary ductal system. It remains to be determined in the MCMV system whether there is a preference for the virus to be secreted at the apical membrane, but if such a preference exists, this would provide an explanation for the apparent failure of the virus to spread across the tight junctions and infect adjacent cells within an infected acinus. Perhaps this is a unique strategy utilized by the cytomegaloviruses to facilitate persistent low-level replication and shedding of virus from the salivary epithelium into the saliva without causing a fully mounted inflammatory response by the immune system, which could eliminate virus more efficiently. The establishment of the primary salisphere-derived systems described in the present study may enable subsequent studies using polarized cells or more fully matured salivary organoids to model apical/basolateral preferences or subcellular compartment preferences for CMV maturation and release.

In a recent study by Mayer and colleagues, the authors built computational models based on observations of infants infected with HCMV. Their data indicated that oral HCMV infection begins with a single virus that spreads inefficiently to neighboring cells within the oral epithelium (30). Their modeling studies identified two mathematical parameters: the first is that a very small number of oral epithelial cells initially are infected (1 to 4 cells), and the second is that fewer than 1.5 new cells became infected from each initially infected cell. While innate immunity and interferon production could explain this tight control of HCMV replication and spread, our current results with primary salivary cells indicate that an additional parameter should be considered for the inefficient spread of virus in the oral epithelium of HCMV-infected infants. Namely, the epithelial cells in the oral cavity and salivary gland may exhibit a more rapid onset of cell death after HCMV infection, limiting the magnitude and robustness of virus spread. Primary salivary cell systems developed using the methodologies described in our study will enable systematic analyses of the mechanisms involved in cell death as well the identification of the HCMV genes required for efficient replication in the salivary epithelium.

The development and improvement of “humanized” mouse models have begun to allow investigations of HCMV pathogenesis in vivo. Mice containing a humanized immune system have been developed by engrafting human tissue, mostly progenitor cells from human bone marrow, into immunodeficient mice (54). In particular, several studies have used SCID mice that were engrafted with human fetal thymic and liver tissues, which led to an evaluation of the differences in the relative abilities of various HCMV strains to infect and replicate in the implanted tissues (55, 56). The development of immunodeficient mice containing a mutation in the interleukin 2 receptor γ chain locus was a major success, as these mice retained human progenitor cell allografts much more readily (57). Given the importance of oral and salivary HCMV replication for HCMV pathogenesis and transmission, the development of murine systems with humanized salivary glands could provide a novel model to study aspects of HCMV interactions with the oral epithelium. Recent studies from the Coppes laboratory have demonstrated success in reconstituting salivary function in mice previously subjected to irreversible radiation damage (32, 58–61). Murine salispheres grown on Matrigel basement membranes exhibit stemlike qualities, and when injected into the salivary glands of irradiated mice, they are capable of forming functional salivary acini that restore saliva production (59, 61). It remains to be determined if human salispheres grown on basement membranes may be capable of restoring salivary function when implanted into immunocompromised mice. Such a model would facilitate in vivo studies in which HCMV replication could be studied in a three-dimensional epithelial environment and in a tissue that is critical for HCMV spread. Moreover, simultaneous reconstitution of immune system function with human bone marrow-derived progenitor cells may enable investigations regarding how the immune system regulates HCMV replication and spread within the oral and salivary epithelia.

In summary, we have established a human salivary cell system that can easily be adapted by other laboratories interested in studying HCMV interactions with a host epithelial cell type that is important for pathogenesis. These cells are readily infected by epitheliotropic HCMV strains containing UL128-UL130 pentamer proteins and support lytic replication. Interestingly, virus-infected salivary epithelial cells undergo a relatively extensive level of cell death, which may lead to a failure of the virus to efficiently spread throughout the cultures, as might be expected based on studies in other in vitro cellular models, such as fibroblasts or ARPE19 epithelial cells. The properties that we observe in these salivary epithelial cells are, however, very reminiscent of observations made in the MCMV model and in human epidemiological studies, which indicate that CMV replication and spread in the salivary and oral epithelium may occur in a much more restricted fashion. The development of this system provides the necessary tools to continue to pursue mechanistic studies aimed at understanding the molecular events leading to restricted virus spread and may provide important clues underpinning the mechanism(s) by which cytomegaloviruses persist for extended periods of time in the salivary epithelium, where they can be readily shed to nearby uninfected individuals.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Isolation and cultivation of salivary gland salispheres and salisphere-derived epithelial cells.

Submandibular or parotid salivary glands from human patients were kindly provided by the Department of Otolaryngology at the University of Cincinnati. Salivary tissue is commonly resected in many head and neck surgical procedures and is usually uninvolved in the malignant process. This study has been reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at the University of Cincinnati (Federal-Wide Assurance number 00003152; IRB protocol 2016-4183). Fresh salivary gland tissues were digested with dispase (1 U/ml) and collagenase type III (0.15%) and mechanically minced using scissors. Following digestion and lysis of red blood cells, the salivary cells were plated on Cultrex PathClear basement membrane extract (BME) gels (R&D Systems) and cultured in BEGM growth medium (containing the BEGM bullet kit and 4% charcoal-stripped fetal bovine serum [FBS]), provided by Lonza. Tissue treated in this manner typically results in the outgrowth of numerous salivary clusters (salispheres) growing on the surface of the BME. Once the salisphere morphology becomes apparent (5 to 8 days), the salispheres are again digested with dispase-collagenase and subjected to trypsinization to generate single-cell suspensions. The resulting cell suspensions were either replated onto BME gels or plated as monolayers on cell culture-treated plates. Cellular senescence typically occurs within 3 to 8 passages depending on the efficiency of the outgrowth of salispheres from the tissue samples. Three human parotid gland-derived primary cell cultures (Par1, Par2, and Par3) and three human submandibular gland-derived primary cell cultures (Sub1, Sub 2, and Sub3) were used in the present study.

HS68 fibroblasts and ARPE19 cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). HS68 fibroblasts are normal human foreskin fibroblasts derived from a Caucasian infant at the time of circumcision. HS68 fibroblasts were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. ARPE19 cells are epithelial cells derived from the retina of an individual who died from injuries related to a car accident. ARPE19 cells were maintained in DMEM–F-12 medium supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin.

Virus strains and preparation of virus stocks.

The laboratory HCMV strains AD169 (ATCC), TB40E (TB40E-mCherry-3×FLAGUS28), RV-FIX (FIX-GFP) (kind gift of Christine O’Connor, Cleveland Clinic), and TB40E-GFP (kind gift of Andrew Yurochko, LSU Health Sciences Center in Shreveport) and the human primary clinical isolate MOLD (kind gift of Chris Benedict, LAIA) were used in these experiments. To generate virus stocks, HS68 cells were plated into T-150 flasks and infected at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.01. The infected cells were fed every 3 days until the percentage of cells exhibiting an obvious cytopathic effect (CPE) reached 100%. Cell culture supernatants containing virus were typically harvested at days 9, 11, and 13 postinfection, snap-frozen, and stored at −80°C until use.

RT-PCR analysis of salivary cell gene expression.

RNA from human salivary gland tissue samples and cultured salisphere cells was isolated using a GeneJET purification kit (Thermo Scientific) and subsequently treated with DNase using the Turbo DNA-free kit (Invitrogen) to remove contaminating genomic DNA. First-strand cDNA was synthesized from the DNase-treated RNA using an iScript cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories). PCR amplification of cDNA was performed in an Eppendorf Mastercycler. Primers used to perform RT-PCR are listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Sequences of primers used for RT-PCR in this study

| Primer sequence | Genea | Direction |

|---|---|---|

| 5′-GGTCTGTCAGGGTTGGAAAGT-3′ | Amylase-1 | Forward |

| 5′-CCTGCACTCACAGCATTACC-3′ | Amylase-1 | Reverse |

| 5′-TCGAGAATTTCCATTTTATGGGGAC-3′ | Histatin-1 | Forward |

| 5′-CTCAGAAACAGCAGTGAAAACAG-3′ | Histatin-1 | Reverse |

| 5′-TGAGACTTCACTTCAGCTTCACT-3′ | Histatin-3 | Forward |

| 5′-ACACGAGTCCAAAGCGAATTT-3′ | Histatin-3 | Reverse |

| 5′-CATTGGCCCTCTAGGGTAGC-3′ | Statherin | Forward |

| 5′-AACCGAATCTTCCAATTCTACGC-3′ | Statherin | Reverse |

| 5′-CCAAAAAGCTCGACTGGAGTGT-3′ | Mucin-7 | Forward |

| 5′-TAGGCCTACAGCGTTTGTGC-3′ | Mucin-7 | Reverse |

| 5′-GCAAGAGTCATTTTGACCAGCA-3′ | SMR3B | Forward |

| 5′-AATCCTGGGCCAAAAGGTTGA-3′ | SMR3B | Reverse |

| 5′-GCTCAGGACAACACTCGGAA-3′ | PIP | Forward |

| 5′-AATCACCTGGGTGTGGCAAA-3′ | PIP | Reverse |

| 5′-AGGACTGAACGTCTTGCTCG-3′ | HPRT | Forward |

| 5′-ATCCAACACTTCGTGGGGTC-3′ | HPRT | Reverse |

Abbreviations: HPRT, hypoxanthine-guanine phosphotransferase; PIP, prolactin-induced protein; SMR3B, submaxillary gland androgen-regulated protein 3B.

Western blot analyses of HCMV protein expression in infected cells.

Parotid epithelial, submandibular epithelial, and HS68 fibroblast cells were seeded into 6-well cell culture plates at a density of 3.0 × 105 cells per well and either mock infected or infected with HCMV-TB40E at an MOI of 1.0. Whole-cell lysates were collected at various time points postinfection, separated by SDS-PAGE, and transferred to nitrocellulose for Western blot analysis. Western blots were probed with the following primary antibodies: anti-IE1/IE2 (Chemicon), anti-UL44 (kind gift of John Shanley), anti-pp65 (Virusys Corporation), and cellular β-actin antibody (Bethyl Laboratories). Next, each blot was incubated with appropriate horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit or anti-mouse IgG secondary antibodies. Chemiluminescence was detected and quantified using a C-DiGit blot scanner from Li-Cor.

Flow cytometric analysis of viral entry and spread using GFP expression or IE staining.

Parotid and HS68 cells were seeded into 12-well plates at 1.0 × 105 cells per well and either mock infected or infected at various MOIs the same day. Cells were trypsinized at appropriate time points and then neutralized with complete medium. Cell suspensions were spun down at 500 to 800 relative centrifugal force (rcf) for 5 min, and the cell pellet was fixed in 70% ethanol for 30 min. Following fixation, cells were permeabilized in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 0.5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) and 0.5% Tween 20 for 10 min at 4°C, pelleted, and then stained with IE1/IE2 antibody (mAb810-Alexa Fluor 488) diluted in PBS supplemented with 0.5% BSA for 2 h. Cells were washed with PBS supplemented with 0.5% BSA–0.5% Tween 20 and then resuspended in PBS. Cells were analyzed using the FL1 channel on a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). Cells infected with FIX-GFP were also trypsinized at appropriate time points, neutralized in the appropriate media, and directly analyzed for GFP positivity using the FL1 channel on the FACSCalibur instrument. The salivary epithelial infectivity index was calculated as follows. The titers of HCMV strains were first determined on HS68 fibroblasts. HS68 or salivary cell lines were then infected at an MOI of 1 based on the titers determined in HS68 fibroblasts. Forty-eight hours after infection, the percentage of infected salivary cells and the percentage of HS68 fibroblasts were determined. The infectivity index is calculated based on the ratio of infected salivary cells over infected HS68 fibroblasts. For example, if, under these conditions, 30% of the epithelial cells became infected, while 60% of the fibroblasts became infected, the salivary infectivity index would be 30%/60%, or 0.5.

Analysis of cell death using SYTOX orange.

Parotid and HS68 cells were seeded into 12-well plates at 2.0 × 105 cells per well and either mock infected or infected with FIX-GFP at various MOIs the same day. At various time points, cells were trypsinized and neutralized in the appropriate media. The cell suspensions were incubated with SYTOX orange (Invitrogen) for 30 min at room temperature in the dark. The cells were analyzed using both the FL1 (GFP) and FL2 (SYTOX orange) channels on the FACSCalibur instrument (BD Biosciences).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Christine O’Connor for providing the recombinant TB40E and FIX-GFP viruses, Chris Benedict for providing the MOLD clinical isolate of HCMV, Andrew Yurochko for providing the TB40E-GFP virus, and John Shanley for providing the UL44 antibody. James P. Bridges provided significant guidance on the methodologies involved in culturing primary salispheres, and Jeanette L. C. Miller assisted by critically reading the manuscript.

Matthew J. Beucler was supported by National Institutes of Health training grant T32-ES007250. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants R56-AI121028 and R21-DE026267 awarded to William E. Miller.

REFERENCES

- 1.Roy CR, Mocarski ES. 2007. Pathogen subversion of cell-intrinsic innate immunity. Nat Immunol 8:1179–1187. doi: 10.1038/ni1528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mocarski ES, Shenk T, Pass RF. 2007. Cytomegaloviruses, p 2702–2772. In Knipe DM, Howley PM, Griffin DE, Lamb RA, Martin MA, Roizman B, Straus SE (ed), Fields virology, 5th ed, vol2 Lippincott Williams & Williams, Philadelphia, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stagno S, Pass RF, Dworsky ME, Henderson RE, Moore EG, Walton PD, Alford CA. 1982. Congenital cytomegalovirus infection: the relative importance of primary and recurrent maternal infection. N Engl J Med 306:945–949. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198204223061601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boppana SB, Pass RF, Britt WJ, Stagno S, Alford CA. 1992. Symptomatic congenital cytomegalovirus infection: neonatal morbidity and mortality. Pediatr Infect Dis J 11:93–99. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199202000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ljungman P, Griffiths P, Paya C. 2002. Definitions of cytomegalovirus infection and disease in transplant recipients. Clin Infect Dis 34:1094–1097. doi: 10.1086/339329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hebart H, Einsele H. 1998. Diagnosis and treatment of cytomegalovirus infection. Curr Opin Hematol 5:483–487. doi: 10.1097/00062752-199811000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Campbell AE, Cavanaugh VJ, Slater JS. 2008. The salivary glands as a privileged site of cytomegalovirus immune evasion and persistence. Med Microbiol Immunol 197:205–213. doi: 10.1007/s00430-008-0077-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cannon MJ, Schmid DS, Hyde TB. 2010. Review of cytomegalovirus seroprevalence and demographic characteristics associated with infection. Rev Med Virol 20:202–213. doi: 10.1002/rmv.655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wagner RP, Tian H, McPherson MJ, Latham PS, Orenstein JM. 1996. AIDS-associated infections in salivary glands: autopsy survey of 60 cases. Clin Infect Dis 22:369–371. doi: 10.1093/clinids/22.2.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adler SP. 1991. Cytomegalovirus and child day care: risk factors for maternal infection. Pediatr Infect Dis J 10:590–594. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199108000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fitzgerald NA, Papadimitriou JM, Shellam GR. 1990. Cytomegalovirus-induced pneumonitis and myocarditis in newborn mice. A model for perinatal human cytomegalovirus infection. Arch Virol 115:75–88. doi: 10.1007/BF01310624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krmpotic A, Bubic I, Polic B, Lucin P, Jonjic S. 2003. Pathogenesis of murine cytomegalovirus infection. Microbes Infect 5:1263–1277. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2003.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bittencourt FM, Wu SE, Bridges JP, Miller WE. 2014. The M33 G protein-coupled receptor encoded by murine cytomegalovirus is dispensable for hematogenous dissemination but is required for growth within the salivary gland. J Virol 88:11811–11824. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01006-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Humphreys IR, de Trez C, Kinkade A, Benedict CA, Croft M, Ware CF. 2007. Cytomegalovirus exploits IL-10-mediated immune regulation in the salivary glands. J Exp Med 204:1217–1225. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lindenberg M, Solmaz G, Puttur F, Sparwasser T. 2014. Mouse cytomegalovirus infection overrules T regulatory cell suppression on natural killer cells. Virol J 11:145. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-11-145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Puttur F, Arnold-Schrauf C, Lahl K, Solmaz G, Lindenberg M, Mayer CT, Gohmert M, Swallow M, van Helt C, Schmitt H, Nitschke L, Lambrecht BN, Lang R, Messerle M, Sparwasser T. 2013. Absence of Siglec-H in MCMV infection elevates interferon alpha production but does not enhance viral clearance. PLoS Pathog 9:e1003648. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tomas MI, Kucic N, Mahmutefendic H, Blagojevic G, Lucin P. 2010. Murine cytomegalovirus perturbs endosomal trafficking of major histocompatibility complex class I molecules in the early phase of infection. J Virol 84:11101–11112. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00988-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cannon MJ, Hyde TB, Schmid DS. 2011. Review of cytomegalovirus shedding in bodily fluids and relevance to congenital cytomegalovirus infection. Rev Med Virol 21:240–255. doi: 10.1002/rmv.695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stoddart CA, Cardin RD, Boname JM, Manning WC, Abenes GB, Mocarski ES. 1994. Peripheral blood mononuclear phagocytes mediate dissemination of murine cytomegalovirus. J Virol 68:6243–6253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jonjic S, Mutter W, Weiland F, Reddehase MJ, Koszinowski UH. 1989. Site-restricted persistent cytomegalovirus infection after selective long-term depletion of CD4+ T lymphocytes. J Exp Med 169:1199–1212. doi: 10.1084/jem.169.4.1199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Upton JW, Kaiser WJ, Mocarski ES. 2010. Virus inhibition of RIP3-dependent necrosis. Cell Host Microbe 7:302–313. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2010.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saederup N, Lin YC, Dairaghi DJ, Schall TJ, Mocarski ES. 1999. Cytomegalovirus-encoded beta chemokine promotes monocyte-associated viremia in the host. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 96:10881–10886. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.19.10881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Manzur M, Fleming P, Huang DC, Degli-Esposti MA, Andoniou CE. 2009. Virally mediated inhibition of Bax in leukocytes promotes dissemination of murine cytomegalovirus. Cell Death Differ 16:312–320. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2008.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Davis-Poynter NJ, Lynch DM, Vally H, Shellam GR, Rawlinson WD, Barrell BG, Farrell HE. 1997. Identification and characterization of a G protein-coupled receptor homolog encoded by murine cytomegalovirus. J Virol 71:1521–1529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lagenaur LA, Manning WC, Vieira J, Martens CL, Mocarski ES. 1994. Structure and function of the murine cytomegalovirus sgg1 gene: a determinant of viral growth in salivary gland acinar cells. J Virol 68:7717–7727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sherrill JD, Stropes MP, Schneider OD, Koch DE, Bittencourt FM, Miller JL, Miller WE. 2009. Activation of intracellular signaling pathways by the murine cytomegalovirus G protein-coupled receptor M33 occurs via PLC-β/PKC-dependent and -independent mechanisms. J Virol 83:8141–8152. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02116-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cardin RD, Schaefer GC, Allen JR, Davis-Poynter NJ, Farrell HE. 2009. The M33 chemokine receptor homolog of murine cytomegalovirus exhibits a differential tissue-specific role during in vivo replication and latency. J Virol 83:7590–7601. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00386-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Farrell HE, Abraham AM, Cardin RD, Molleskov-Jensen AS, Rosenkilde MM, Davis-Poynter N. 2013. Identification of common mechanisms by which human and mouse cytomegalovirus seven-transmembrane receptor homologues contribute to in vivo phenotypes in a mouse model. J Virol 87:4112–4117. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03406-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Farrell HE, Abraham AM, Cardin RD, Sparre-Ulrich AH, Rosenkilde MM, Spiess K, Jensen TH, Kledal TN, Davis-Poynter N. 2011. Partial functional complementation between human and mouse cytomegalovirus chemokine receptor homologues. J Virol 85:6091–6095. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02113-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mayer BT, Krantz EM, Swan D, Ferrenberg J, Simmons K, Selke S, Huang ML, Casper C, Corey L, Wald A, Schiffer JT, Gantt S. 26 May 2017. Transient oral human cytomegalovirus infections indicate inefficient viral spread from very few initially infected cells. J Virol doi: 10.1128/JVI.00380-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tran SD, Wang J, Bandyopadhyay BC, Redman RS, Dutra A, Pak E, Swaim WD, Gerstenhaber JA, Bryant JM, Zheng C, Goldsmith CM, Kok MR, Wellner RB, Baum BJ. 2005. Primary culture of polarized human salivary epithelial cells for use in developing an artificial salivary gland. Tissue Eng 11:172–181. doi: 10.1089/ten.2005.11.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pringle S, Van Os R, Coppes RP. 2013. Concise review: adult salivary gland stem cells and a potential therapy for xerostomia. Stem Cells 31:613–619. doi: 10.1002/stem.1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Samuni Y, Baum BJ. 2011. Gene delivery in salivary glands: from the bench to the clinic. Biochim Biophys Acta 1812:1515–1521. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2011.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Coppes RP, Stokman MA. 2011. Stem cells and the repair of radiation-induced salivary gland damage. Oral Dis 17:143–153. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2010.01723.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Feng J, van der Zwaag M, Stokman MA, van Os R, Coppes RP. 2009. Isolation and characterization of human salivary gland cells for stem cell transplantation to reduce radiation-induced hyposalivation. Radiother Oncol 92:466–471. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2009.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baek H, Noh YH, Lee JH, Yeon SI, Jeong J, Kwon H. 2014. Autonomous isolation, long-term culture and differentiation potential of adult salivary gland-derived stem/progenitor cells. J Tissue Eng Regen Med 8:717–727. doi: 10.1002/term.1572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chopra DP, Xue-Hu IC. 1993. Secretion of alpha-amylase in human parotid gland epithelial cell culture. J Cell Physiol 155:223–233. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041550202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chopra DP, Xue-Hu IC, Reddy LV. 1995. Growth and gene expression in diploid epithelial cell lines derived from normal human parotid gland. Differentiation 58:241–251. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-0436.1995.5830241.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhou M, Lanchy JM, Ryckman BJ. 2015. Human cytomegalovirus gH/gL/gO promotes the fusion step of entry into all cell types, whereas gH/gL/UL128-131 broadens virus tropism through a distinct mechanism. J Virol 89:8999–9009. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01325-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhou M, Yu Q, Wechsler A, Ryckman BJ. 2013. Comparative analysis of gO isoforms reveals that strains of human cytomegalovirus differ in the ratio of gH/gL/gO and gH/gL/UL128-131 in the virion envelope. J Virol 87:9680–9690. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01167-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ryckman BJ, Rainish BL, Chase MC, Borton JA, Nelson JA, Jarvis MA, Johnson DC. 2008. Characterization of the human cytomegalovirus gH/gL/UL128-131 complex that mediates entry into epithelial and endothelial cells. J Virol 82:60–70. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01910-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Murrell I, Tomasec P, Wilkie GS, Dargan DJ, Davison AJ, Stanton RJ. 2013. Impact of sequence variation in the UL128 locus on production of human cytomegalovirus in fibroblast and epithelial cells. J Virol 87:10489–10500. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01546-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Krosky PM, Baek MC, Jahng WJ, Barrera I, Harvey RJ, Biron KK, Coen DM, Sethna PB. 2003. The human cytomegalovirus UL44 protein is a substrate for the UL97 protein kinase. J Virol 77:7720–7727. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.14.7720-7727.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Biolatti M, Dell’Oste V, De Andrea M, Landolfo S. 2018. The human cytomegalovirus tegument protein pp65 (pUL83): a key player in innate immune evasion. New Microbiol 41:87–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Biolatti M, Dell’Oste V, Pautasso S, Gugliesi F, von Einem J, Krapp C, Jakobsen MR, Borgogna C, Gariglio M, De Andrea M, Landolfo S. 2018. Human cytomegalovirus tegument protein pp65 (pUL83) dampens type I interferon production by inactivating the DNA sensor cGAS without affecting STING. J Virol 92:e01774-17. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01774-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Silva MC, Schroer J, Shenk T. 2005. Human cytomegalovirus cell-to-cell spread in the absence of an essential assembly protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102:2081–2086. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409597102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.O’Connor CM, Shenk T. 2011. Human cytomegalovirus pUS27 G protein-coupled receptor homologue is required for efficient spread by the extracellular route but not for direct cell-to-cell spread. J Virol 85:3700–3707. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02442-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bentz GL, Jarquin-Pardo M, Chan G, Smith MS, Sinzger C, Yurochko AD. 2006. Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) infection of endothelial cells promotes naive monocyte extravasation and transfer of productive virus to enhance hematogenous dissemination of HCMV. J Virol 80:11539–11555. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01016-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cotrim AP, Mineshiba F, Sugito T, Samuni Y, Baum BJ. 2006. Salivary gland gene therapy. Dent Clin North Am 50:157–173. doi: 10.1016/j.cden.2005.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Feng J, Coppes RP. 2008. Can we rescue salivary gland function after irradiation? ScientificWorldJournal 8:959–962. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2008.132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jeong J, Baek H, Kim YJ, Choi Y, Lee H, Lee E, Kim ES, Hah JH, Kwon TK, Choi IJ, Kwon H. 2013. Human salivary gland stem cells ameliorate hyposalivation of radiation-damaged rat salivary glands. Exp Mol Med 45:e58. doi: 10.1038/emm.2013.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Murphy E, Yu D, Grimwood J, Schmutz J, Dickson M, Jarvis MA, Hahn G, Nelson JA, Myers RM, Shenk TE. 2003. Coding potential of laboratory and clinical strains of human cytomegalovirus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100:14976–14981. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2136652100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ryckman BJ, Jarvis MA, Drummond DD, Nelson JA, Johnson DC. 2006. Human cytomegalovirus entry into epithelial and endothelial cells depends on genes UL128 to UL150 and occurs by endocytosis and low-pH fusion. J Virol 80:710–722. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.2.710-722.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Crawford LB, Streblow DN, Hakki M, Nelson JA, Caposio P. 2015. Humanized mouse models of human cytomegalovirus infection. Curr Opin Virol 13:86–92. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2015.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Brown JM, Kaneshima H, Mocarski ES. 1995. Dramatic interstrain differences in the replication of human cytomegalovirus in SCID-hu mice. J Infect Dis 171:1599–1603. doi: 10.1093/infdis/171.6.1599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mocarski ES, Bonyhadi M, Salimi S, McCune JM, Kaneshima H. 1993. Human cytomegalovirus in a SCID-hu mouse: thymic epithelial cells are prominent targets of viral replication. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 90:104–108. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.1.104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Brehm MA, Wiles MV, Greiner DL, Shultz LD. 2014. Generation of improved humanized mouse models for human infectious diseases. J Immunol Methods 410:3–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2014.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nanduri LS, Maimets M, Pringle SA, van der Zwaag M, van Os RP, Coppes RP. 2011. Regeneration of irradiated salivary glands with stem cell marker expressing cells. Radiother Oncol 99:367–372. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2011.05.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nanduri LS, Lombaert IM, van der Zwaag M, Faber H, Brunsting JF, van Os RP, Coppes RP. 2013. Salisphere derived c-Kit+ cell transplantation restores tissue homeostasis in irradiated salivary gland. Radiother Oncol 108:458–463. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2013.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lombaert IM, Brunsting JF, Wierenga PK, Faber H, Stokman MA, Kok T, Visser WH, Kampinga HH, de Haan G, Coppes RP. 2008. Rescue of salivary gland function after stem cell transplantation in irradiated glands. PLoS One 3:e2063. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nanduri LS, Baanstra M, Faber H, Rocchi C, Zwart E, de Haan G, van Os R, Coppes RP. 2014. Purification and ex vivo expansion of fully functional salivary gland stem cells. Stem Cell Rep 3:957–964. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2014.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]