Abstract

Background:

Alopecia areata (AA) is an autoimmune-mediated hair follicle disorder. In the literature, there is no study evaluating metabolic syndrome and levels of ischemia-modified albumin (IMA) which is proposed as an oxidative stress biomarker in patients with AA.

Aims:

The aim was to investigate the presence of metabolic syndrome and the levels of IMA, small dense low-density lipoprotein (sd-LDL), and visfatin levels in AA patients.

Settings and Design:

A hospital-based cross-sectional study was undertaken among AA patients and controls.

Subjects and Methods:

Thirty-five patients with AA and 35 sex-, age-, and body mass index-matched healthy controls were enrolled. Clinical and laboratory parameters of metabolic syndrome were examined in all participants. Furthermore, IMA, sd-LDL, and visfatin levels were assessed and analyzed with regard to disease pattern, severity and extent, severity of alopecia tool score, duration, and recurrence.

Results:

The median IMA and adjusted IMA levels were significantly increased compared with controls (P<0.05 and P=0.002, respectively). Patients with pull test positivity displayed higher levels of adjusted IMA levels (P<0.05). In AA group, there was a positive correlation between adjusted IMA and waist circumference (r=0.443, P=0.008), adjusted IMA and triglyceride levels (r=0.535, P=0.001), and adjusted IMA and sd-LDL levels (r=0.46, P<0.05). We observed no statistically significant difference in fasting blood glucose and lipid profile, sd-LDL, and visfatin levels of the patients and healthy controls.

Conclusions:

AA patients and controls have similar metabolic profile. Raised levels of adjusted IMA levels may be associated with antioxidant/oxidant imbalance and with risk of cardiovascular disease.

KEY WORDS: Alopecia areata, ischemia-modified albumin, metabolic parameters, small dense low-density lipoprotein, visfatin

Introduction

Alopecia areata (AA), characterized by sudden onset of oval or round alopecic patches, is believed to be an organ-specific autoimmune disorder with a genetic background.[1] Recently, some oxidative stress molecules have been suggested as biomarkers of disease activity and prognosis.[2] Ischemia-modified albumin (IMA) is raised in higher oxidative stress condition, including type-2 diabetes, hypercholesterolemia, and obesity, and is believed to be an oxidative stress marker in many systemic inflammatory disorders.[3,4] In addition, it has been shown that metabolic processes within the cholesterol synthesis pathway may directly influence hair growth through particular signaling molecules.[5] Insulin resistance has been observed in patients with AA.[6] Recently, Lim et al. suggested possible metabolic comorbidities, including hyperlipidemia in AA.[7] Increased level of small dense low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (sd-LDL-C) is one of the main components of atherogenic dyslipidemia.[8]

There are limited data available regarding the relationship among metabolic conditions, cardiovascular diseases, and AA. In addition, recent trials have shown increased lipid peroxidation and defective antioxidant activity in patients with AA.[9] Based on these findings, we aimed to investigate few markers associated with ischemia, oxidative stress, atherogenic hyperlipidemia, and inflammation, as well as their relationship with disease characteristics in AA. To the best of our knowledge, sd-LDL, IMA, and visfatin levels of AA patients have not been studied previously. In the present research, we conducted a case–control study to evaluate the clinical and laboratory parameters of metabolic syndrome as well as sd-LDL, IMA, and visfatin levels in AA patients.

Subjects and Methods

Study population

Patients who presented with hair loss to our department and were diagnosed with AA during January 2017 to December 2017 were included in the study. Thirty-five patients (17 women and 18 men) and 35 age-, sex-, and body mass index (BMI)-matched controls (17 women and 18 men) who fulfilled the inclusion criteria were enrolled. The control group comprised of healthy volunteers who presented with cosmetic complaints.

All the participants were ≥18 year old and were made to undergo systemic and dermatological examinations. Patients with spontaneous hair regrowth at the initial presentation were not included in the study. The exclusion criteria were pregnancy, lactation, history of active or chronic infection, malignancy, ischemic cardiovascular diseases, and hypertension. Factors, such as history of diabetes and thyroid disorders, were matched between the two groups. A family history of AA, premature (≤49 years) cardiovascular diseases, and autoimmune disorders, including atopic dermatitis, allergic rhinitis, asthma, thyroid disease, vitiligo, and diabetes were recorded. Participants with a family history of AA were not included as healthy controls. The demographic characteristics as well as the physical exercise habits and attitudes of the participants in the two groups were noted.

Patients were categorized into subclasses as per the Severity of Alopecia Tool (SALT) scores (S0, no hair loss; S1, <25% hair loss; S2, 25%–49% hair loss; S3, 50%–74% hair loss; S4, 75%–99% hair loss; and S5, 100% hair loss) defined by Olsen et al.[10] Disease characteristics, including the duration of current disease episode, total number of episodes, age at disease onset, pattern of scalp hair loss, presence of positive pull test, AA severity, SALT subclasses, eyebrow involvement, beard involvement, body hair loss, nail involvement, as well as previous and current treatment modalities were noted. Severity of AA was determined as described by Kavak et al.[11] Duration of the current episode was defined as the time from disease onset to the time of first admission of the patient in the study.

Measurements and sample collection

Waist circumference (WC, cm), height (m), weight (kg), systolic blood pressure (normal: 90–120 mmHg), and diastolic blood pressure (normal: 60–80 mmHg) were measured. The BMI (kg/m2) was calculated using the Quetelet index for each participant.[12] All the blood samples (10 ml of peripheral venous blood) from all participants were collected using biochemistry tubes (BD Vacutainer® SST™ II Advance serum tube, 367955 - 13×100 mm×5 ml, BD-Belliver Industrial Estate, Plymouth PL6 7BP, UK) in the morning after an overnight fast. Fasting blood glucose (FBG), total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), and triglycerides (TG) were measured using the enzymatic method. Serum albumin levels were analyzed using the nephelometric method. Levels of LDL-C were determined using Friedewald formula (LDL=total cholesterol – HDL − TG/5.0 [mg/dl]).

For the analyses of visfatin, sd-LDL, and IMA, blood samples were immediately centrifuged (Electromag M815, 1200 g-relative centrifugal force, for 10 min); thereafter, the sera were separated. Samples were stored at −80°C. Serum visfatin levels were quantified using the sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay method (Elabscience Biotechnology Co. Ltd. WuHan, P.R.C., Catalog No: E-EL-H1763, LOT: AK0017NOV20092). Sd-LDL-C levels were measured using the technique previously described by Hirano et al.[13] As defined by Bar-Or et al., rapid colorimetric assay that quantitatively measures unbound cobalt was used for calculating the IMA. The results are expressed in absorbance units. Adjusted IMA levels were calculated using the following formula: Individual albumin/median albumin concentration of the population×IMA.

The accepted normal ranges of the laboratory parameters in this study were as follows: FBG: 74–109 mg/dl; TG: 0–200 mg/dl; LDL-C: 0–100 mg/dl; HDL-C: 40–60 mg/dl; and Very LDL-C: 0–40 mg/dl. For each parameter, a value higher than the upper limit was categorized as “elevated.”

Ethics

Written consent was obtained from all the studied patients and controls before data collection. The study protocol was approved by the Ankara Numune Training and Research Hospital Ethics Committee of Clinical Studies, code: E-16-1149. The study protocol was in accordance with the principles of the Helsinki Declaration of 1975.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software (version 21.0 for Windows; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Parametric variables are presented as means and standard deviations and nonparametric variables are presented as medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs). Frequencies and percentages were calculated for the categorical variables. Chi-square or Fischer's exact test was used for analyzing the categorical variables. Kolmogorov–Smirnov and histogram analyses were used for determining whether the continuous variables were normally distributed. Normally distributed numeric variables were analyzed using Student's t-test and analysis of variance. Mann–Whitney U and Kruskal–Wallis tests were used for comparing the non-normally distributed numeric variables. Correlations of numeric variables were assessed using Spearman and Pearson tests. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

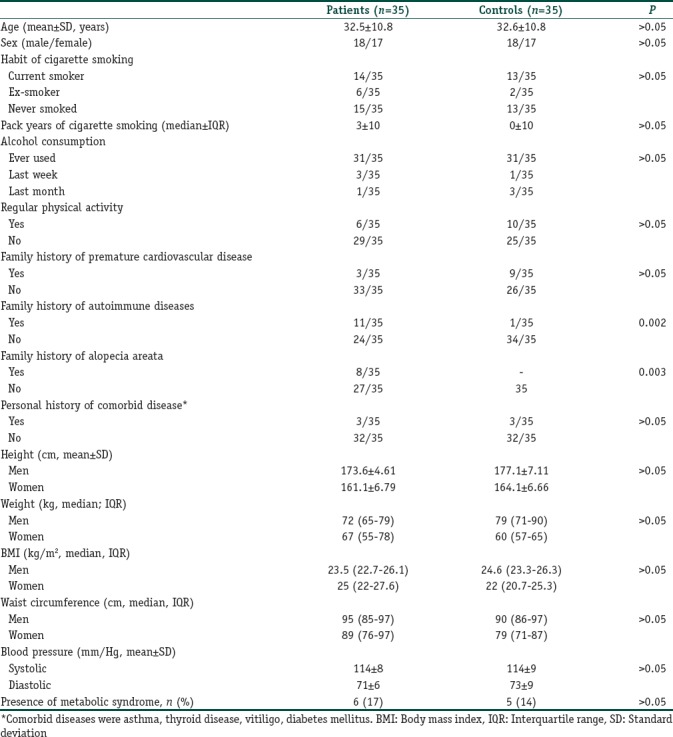

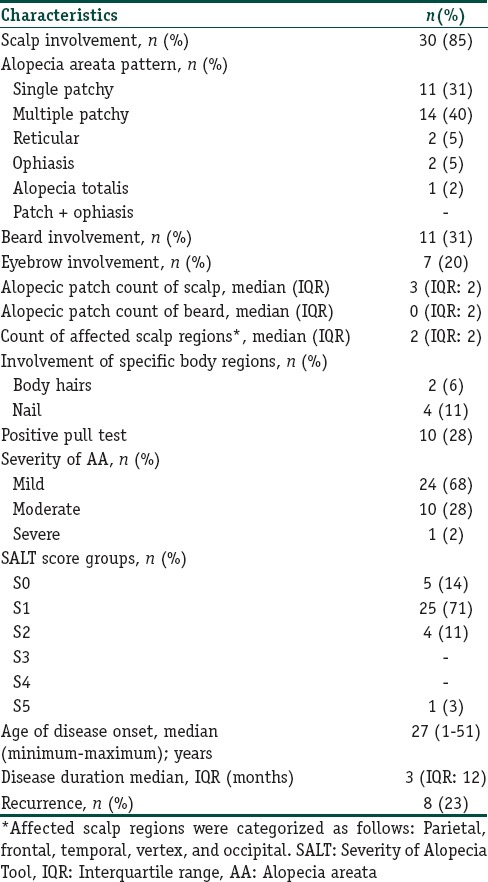

Thirty-five AA patients, including 17 women (48.6%) and 18 men (51.4%) with a mean age ± standard deviation of 32.5±10.8 years, were included in the study. The median BMI values of the AA patients were 23.5 kg/m2 (men) and 25 kg/m2 (women). The controls were matched for age, sex, and BMI. Demographic, physical, and habitual characteristics as well as blood pressure values of both the groups are summarized in Table 1. Both groups exhibited similar physical activity attitude. The prevalence of a family history of premature cardiovascular disease and personal history of comorbid diseases (asthma, thyroid disease, vitiligo, and diabetes mellitus) were similar. However, family history of AA and autoimmune diseases was observed more frequently in the AA group than in the healthy controls (P=0.003 and 0.002, respectively) [Table 1]. No statistically significant difference was present in the prevalence of metabolic syndrome between the patients and healthy controls. The disease characteristics of the patients are presented in Table 2.

Table 1.

Demographic data and characteristics of participants

Table 2.

Disease characteristics of the patients with alopecia areata (n=35)

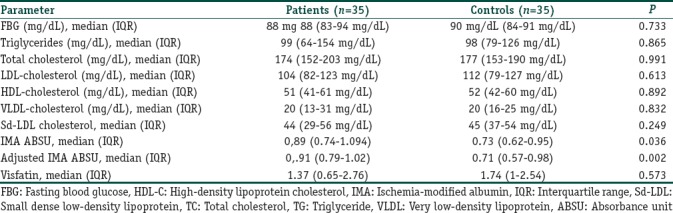

Among all the parameters, the median values of the IMA and adjusted IMA of the patients were significantly different from those of the healthy controls (P<0.05 and P=0.002, respectively) [Table 3]. The adjusted IMA levels did not correlate with disease duration (r=0.17, P=0.33), age at disease onset (r=0.05, P=0.75), number of alopecic patches (r=0.05, P=0.97), total episodes (r=0.12, P=0.47), AA severity (r=0.98, P=0.57), and SALT score (r=0.19, P=0.16). However, we found a significant positive correlation among the adjusted IMA levels, WCs (r=0.443, P=0.008), and TG levels (r=0.535, P=0.001) of the AA patients. Pull test positivity was associated with higher levels of adjusted IMA (P<0.05), while recurrence and presence of beard, eyebrow, body, or nail involvement showed no association. The IMA and adjusted IMA levels were similar between the male and female AA patients.

Table 3.

Results of the metabolic parameters, small dense low density lipoprotein, ischemia modified albumin and visfatin levels

There was no significant difference in the median sd-LDL levels between the AA patients and healthy controls (P>0.05); however, we found a significant positive correlation between sd-LDL and adjusted IMA levels in AA patients (r=0.46, P<0.05). In AA patients, there was a significant difference in the sd-LDL levels of male (45 mg/dl IQR: 26) and female (36 mg/dl, IQR: 19) patients (P<0.05). The metabolic parameters of AA patients and healthy controls are summarized in Table 3.

Discussion

The underlying causal mechanisms of AA remain unclear. The upregulation of immune mechanisms and disruption of the immune privilege of the hair follicle are believed to be the main causative pathogenetic mechanisms. The hair follicles that express low levels of major histocompatibility complex are attacked by autoreactive CD8+ T-lymphocytes. Peribulbar lymphocytic infiltration induces apoptosis of the keratinocytes of the follicle. Consequently, cell cycle inhibition within the hair matrix results in hair loss.[14] In addition, currently, oxidative stress is clearly implicated in AA pathogenesis based on genetic and molecular studies.[15,16] The authors have also demonstrated increased levels of reactive oxygen species and increased oxidative stress in patients with AA.[17,18] Increase in free-radical production may be a probable causative factor.

It is noteworthy that the association of AA with other immune disorders, such as systemic lupus erythematosus, celiac disease, thyroid disease, atopy, and vitiligo, supports the potential role of systemic inflammation in AA pathogenesis.[19] There are conflicting results in the literature regarding the metabolic profile and cardiovascular risk of AA patients. An association between AA and metabolic syndrome has been reported in a recent study.[20] Lim et al. found that the LDL levels of women with AA were higher than those of healthy women.[7] The authors clearly suggested a link among lipid metabolism, cholesterol biosynthesis, and hair disorders in this report. In contrast, the present study revealed that the lipid profiles of the AA patients and healthy controls were comparable. We also observed higher sd-LDL levels in male patients compared to those in female patients, indicating that sex influenced the serum sd-LDL levels. However, the present study did not find similar elevations in healthy men.

The adipose tissue serves as a dynamic endocrine tissue and performs functions beyond simple energy storage. It is involved in the production of several bioactive compounds called adipocytokines that regulate metabolic pathways. These adipocytokines are involved in metabolic disorders, such as insulin resistance and obesity as well as pro-inflammatory and autoimmune processes.[21]

IMA is a modified form of human albumin that increases as a result of hypoxic and free-radical injury.[4] It is recommended to study the IMA results adjusted for albumin levels owing to the influence of albumin concentration on the IMA levels.[22,23] It has been proposed as a marker of oxidative stress and the early diagnosis of acute coronary syndrome. With respect to systemic oxidative injury, the relationship between IMA and few inflammatory dermatologic conditions has been previously reported.[24,25] To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first one to demonstrate a greater increase in the levels of IMA and adjusted IMA in AA patients than in age-, sex-, and BMI-matched healthy controls. It is noteworthy that the study groups in our series were comparable in terms of blood pressure, smoking and drinking habits, as well as the laboratory parameters of metabolic syndrome. Thus, we can hypothesize that these results may support the role of oxidative status in AA pathogenesis. In addition, the adjusted IMA levels were higher in patients with pull test positivity that might represent disease activity. There was no evidence of its relationship with the SALT score, disease severity, pattern, and disease duration. The relatively small sample size may be one of the reasons for these results.

Recently, few studies have addressed the risk of acute myocardial infarction and stroke in AA with conflicting results.[26,27] Kang et al. detected an increased risk of stroke in AA patients.[27] Moreover, Wang et al. demonstrated increased expression of cardiac biomarker troponin in AA patients in a recent report.[28] In a recent study, hypertension and diabetes were more common in late-onset alopecia.[29] Sd-LDL is known to have atherogenic potential.[30] It is noteworthy that we detected a positive correlation between sd-LDL levels and adjusted IMA levels in AA patients. Personal history, family history, smoking and exercise-related attitudes, FBG, and lipid profile were similar to those in the age-, sex- and BMI-matched study groups of the present study; therefore, our findings might support the hypothesis that AA patients were predisposed to have atherogenic dyslipidemia and consequently ischemic complications.

The adipose tissue serves as a dynamic endocrine tissue and performs functions beyond simple energy storage. It is involved in the production of several bioactive compounds called adipocytokines that regulate metabolic pathways. These adipocytokines are involved in metabolic disorders, such as insulin resistance and obesity as well as pro-inflammatory and autoimmune processes.[21] Visfatin, a novel adipocytokine, has proinflammatory effects.[31] Recent studies have demonstrated that serum visfatin levels are increased in both T-helper (Th1) and Th2-mediated inflammatory disorders, including Behçet's disease, psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, and cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.[32,33,34,35] On the contrary, in the current study, we did not find a significant difference in visfatin levels between the groups.

The main limitation of our single-center study is the relatively small sample size. The disease severity was mild to moderate in most patients; therefore, the disease subgroups were too small to allow statistical evaluation. Moreover, some metabolic parameters associated with insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome, including insulin levels, high-sensitive C-reactive protein, and glycosylated hemoglobin were not included.

Conclusions

Increasing evidences suggest the potential role of oxidant-antioxidant imbalance in AA. There are conflicting results in the literature regarding metabolic profiles and cardiovascular risk in AA patients. This study evaluated the prevalence of metabolic syndrome and demonstrated an increase in IMA and adjusted IMA levels in AA patients. We hypothesized that the oxidative process might be associated with disease activity in AA patients. Furthermore, increased IMA levels in these patients might reflect an increased risk of atherosclerosis and cardiovascular diseases. Future, large-scale prospective studies that eliminate the confounding factors are required for determining the exact relationship between AA and the ischemic process.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Ito T, Tokura Y. The role of cytokines and chemokines in the T-cell-mediated autoimmune process in alopecia areata. Exp Dermatol. 2014;23:787–91. doi: 10.1111/exd.12489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jabbari A, Cerise JE, Chen JC, Mackay-Wiggan J, Duvic M, Price V, et al. Molecular signatures define alopecia areata subtypes and transcriptional biomarkers. EBioMedicine. 2016;7:240–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2016.03.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Piva SJ, Duarte MM, Da Cruz IB, Coelho AC, Moreira AP, Tonello R, et al. Ischemia-modified albumin as an oxidative stress biomarker in obesity. Clin Biochem. 2011;44:345–7. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2010.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Duarte MM, Rocha JB, Moresco RN, Duarte T, Da Cruz IB, Loro VL, et al. Association between ischemia-modified albumin, lipids and inflammation biomarkers in patients with hypercholesterolemia. Clin Biochem. 2009;42:666–71. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2009.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davies JT, Delfino SF, Feinberg CE, Johnson MF, Nappi VL, Olinger JT, et al. Current and emerging uses of statins in clinical therapeutics: A review. Lipid Insights. 2016;9:13–29. doi: 10.4137/LPI.S37450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Karadag AS, Ertugrul DT, Bilgili SG, Takci Z, Tutal E, Yilmaz H, et al. Insulin resistance is increased in alopecia areata patients. Cutan Ocul Toxicol. 2013;32:102–6. doi: 10.3109/15569527.2012.713418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lim CP, Severin RK, Petukhova L. Big data reveal insights into alopecia areata comorbidities. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2018;19:S57–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jisp.2017.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brunzell JD, Ayyobi AF. Dyslipidemia in the metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Am J Med. 2003;115(Suppl 8A):24S–28S. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2003.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abdel Fattah NS, Ebrahim AA, El Okda ES. Lipid peroxidation/antioxidant activity in patients with alopecia areata. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:403–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2010.03799.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Olsen EA, Hordinsky MK, Price VH, Roberts JL, Shapiro J, Canfield D, et al. Alopecia areata investigational assessment guidelines – Part II. National alopecia areata foundation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:440–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2003.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kavak A, Baykal C, Ozarmağan G, Akar U. HLA in alopecia areata. Int J Dermatol. 2000;39:589–92. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.2000.00921.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eknoyan G. Adolphe quetelet (1796-1874) – The average man and indices of obesity. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008;23:47–51. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfm517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hirano T, Ito Y, Koba S, Toyoda M, Ikejiri A, Saegusa H, et al. Clinical significance of small dense low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels determined by the simple precipitation method. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:558–63. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000117179.92263.08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Trüeb RM, Dias M. Alopecia areata: A comprehensive review of pathogenesis and management. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2018;54:68–87. doi: 10.1007/s12016-017-8620-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yenin JZ, Serarslan G, Yönden Z, Uluta KT. Investigation of oxidative stress in patients with alopecia areata and its relationship with disease severity, duration, recurrence and pattern. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2015;40:617–21. doi: 10.1111/ced.12556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Strazzulla LC, Wang EH, Avila L, Lo Sicco K, Brinster N, Christiano AM, et al. Alopecia areata: Disease characteristics, clinical evaluation, and new perspectives on pathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:1–2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.04.1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koca R, Armutcu F, Altinyazar C, Gürel A. Evaluation of lipid peroxidation, oxidant/antioxidant status, and serum nitric oxide levels in alopecia areata. Med Sci Monit. 2005;11:CR296–299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bakry OA, Elshazly RM, Shoeib MA, Gooda A. Oxidative stress in alopecia areata: A case-control study. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2014;15:57–64. doi: 10.1007/s40257-013-0036-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chu SY, Chen YJ, Tseng WC, Lin MW, Chen TJ, Hwang CY, et al. Comorbidity profiles among patients with alopecia areata: The importance of onset age, a nationwide population-based study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:949–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2010.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ishak RS, Piliang MP. Association between alopecia areata, psoriasis vulgaris, thyroid disease, and metabolic syndrome. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2013;16:S56–7. doi: 10.1038/jidsymp.2013.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tilg H, Moschen AR. Adipocytokines: Mediators linking adipose tissue, inflammation and immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:772–83. doi: 10.1038/nri1937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hakligör A, Kösem A, Seneş M, Yücel D. Effect of albumin concentration and serum matrix on ischemia-modified albumin. Clin Biochem. 2010;43:345–8. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2009.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ahn JH, Choi SC, Lee WG, Jung YS. The usefulness of albumin-adjusted ischemia-modified albumin index as early detecting marker for ischemic stroke. Neurol Sci. 2011;32:133–8. doi: 10.1007/s10072-010-0457-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ozdemir M, Kiyici A, Balevi A, Mevlitoğlu I, Peru C. Assessment of ischaemia-modified albumin level in patients with psoriasis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2012;37:610–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2012.04384.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Capkin E, Karkucak M, Kola M, Karaca A, Aydin Capkin A, Caner Karahan S, et al. Ischemia-modified albumin (IMA): A novel marker of vascular involvement in Behçet's disease? Joint Bone Spine. 2015;82:68–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2014.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang KP, Joyce CJ, Topaz M, Guo Y, Mostaghimi A. Cardiovascular risk in patients with alopecia areata (AA): A propensity-matched retrospective analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:151–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.02.1234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kang JH, Lin HC, Kao S, Tsai MC, Chung SD. Alopecia areata increases the risk of stroke: A 3-year follow-up study. Sci Rep. 2015;5:11718. doi: 10.1038/srep11718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang EH, Santos L, Li XY, Tran A, Kim SS, Woo K, et al. Alopecia areata is associated with increased expression of heart disease biomarker cardiac troponin I. Acta Derm Venereol. 2018;98:776–82. doi: 10.2340/00015555-2964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee NR, Kim BK, Yoon NY, Lee SY, Ahn SY, Lee WS. Differences in comorbidity profiles between early-onset and late-onset alopecia areata patients: A retrospective study of 871 Korean patients. Ann Dermatol. 2014;26:722–6. doi: 10.5021/ad.2014.26.6.722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ivanova EA, Myasoedova VA, Melnichenko AA, Grechko AV, Orekhov AN. Small dense low-density lipoprotein as biomarker for atherosclerotic diseases. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2017;2017:1273042. doi: 10.1155/2017/1273042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Luk T, Malam Z, Marshall JC. Pre-B cell colony-enhancing factor (PBEF)/visfatin: A novel mediator of innate immunity. J Leukoc Biol. 2008;83:804–16. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0807581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ozgen M, Koca SS, Aksoy K, Dagli N, Ustundag B, Isik A. Visfatin levels and intima-media thicknesses in rheumatic diseases. Clin Rheumatol. 2011;30:757–63. doi: 10.1007/s10067-010-1649-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gerdes S, Osadtschy S, Rostami-Yazdi M, Buhles N, Weichenthal M, Mrowietz U. Leptin, adiponectin, visfatin and retinol-binding protein-4 – Mediators of comorbidities in patients with psoriasis? Exp Dermatol. 2012;21:43–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2011.01402.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ismail SA, Mohamed SA. Serum levels of visfatin and omentin-1 in patients with psoriasis and their relation to disease severity. Br J Dermatol. 2012;167:436–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2012.10980.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Suga H, Sugaya M, Miyagaki T, Kawaguchi M, Morimura S, Kai H, et al. Serum visfatin levels in patients with atopic dermatitis and cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Eur J Dermatol. 2013;23:629–35. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2013.2107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]