Abstract

Context:

Androgenic alopecia (AGA) is a hereditary androgen-dependent disorder, characterized by gradual conversion of terminal hair into miniaturized hair and defined by various patterns. Common age group affected is between 30 and 50 years. Metabolic syndrome (MetS) is a cluster of cardiovascular risk factors that include diabetes and prediabetes, abdominal obesity, dyslipidemia, and hypertension. The relationship between androgenic alopecia and MetS is still poorly understood.

Aim:

The aim was to study the clinical profile of androgenic alopecia and its association with cardiovascular risk factors.

Materials and Methods:

This was a hospital-based cross-sectional study done on men in the age group of 25–40 years. Fifty clinically diagnosed cases with early-onset androgenic alopecia of Norwood Grade III or above and fifty controls without androgenic alopecia were included in the study. Data collected included anthropometric measurements, blood pressure, family history of androgenic alopecia, history of alcohol, smoking; fasting blood sugar, and lipid profile were done. MetS was diagnosed as per the new International Diabetes Federation criteria. Chi-square and Student's t-test were used for statistical analysis.

Results:

MetS was seen in 5 (10%) cases and 1 (2%) control (P=0.092). Abdominal obesity, hypertension, and lowered high-density lipoprotein were significantly higher in patients with androgenic alopecia when compared to that of the controls.

Conclusion:

A higher prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors was seen in men with early-onset androgenic alopecia. Early screening for MetS and its components may be beneficial in patients with early-onset androgenic alopecia.

KEY WORDS: Androgenic alopecia, cardiovascular disease, metabolic syndrome

Introduction

Androgenic alopecia (AGA) is an emotionally distressing and therapeutically frustrating dermatological problem characterized by frontal and vertex thinning with receding anterior hairline or loss of all hairs. Hamilton proposed a mutual interplay of genetic factors, androgens, and age factor as the cause of AGA. It is a genetically determined disorder in which there is gradual conversion of terminal hair into intermediate hair and finally into vellus hair.[1]

The mode of inheritance is polygenic and occurs under the influence of androgens in genetically predisposed individuals. Metabolic syndrome (MetS) is a cluster of inter-related risk factors that increase the risk of coronary artery disease (CAD) and includes central obesity, hypertension, hyperglycemia, and dyslipidemia. Other newer risk factors include serum lipoprotein-a, serum homocysteine, and serum adiponectin.[2] Several recent studies have shown that AGA is associated with increased risk of CAD, but pathophysiology has been poorly understood. To establish a better relation between AGA and CAD, we have studied the association of AGA with MetS among patients of central Gujarat through a case–control study.

Materials and Methods

This was a hospital-based case–control study of 50 male patients and 50 age-matched controls attending the skin outpatient department between June 2014 and May 2016 in the age group of 25–40 years with clinically diagnosed androgenic alopecia with Norwood Type III or above. AGA developing before 36 year of age and reaching at least Stage III of Hamilton–Norwood classification is termed as early-onset AGA.[3] Age-matched healthy individuals with normal hair status who were having other minor skin problems were taken as control. The study was limited to men because of the possible differences in pathogenesis and the controversial role of androgens in female pattern hair loss.

Ethical approval for the study was taken from the Institutional Ethics Committee. After obtaining written informed consent from each subject, detailed history and clinical examination were conducted and the details were entered in a predesigned proforma. The history included age, occupation, duration of alopecia (based on patient history), family history of androgenic alopecia, hypertension, diabetes mellitus and dyslipidemia, history of smoking and alcohol consumption and treatment details for alopecia. The degree of androgenic alopecia was based on the Norwood scale (III–VII). Weight, height, and waist circumference were recorded. Waist circumference was measured at the midpoint between the lower margin of the last palpable rib and the top of the iliac crest at the end of a normal expiration. Blood pressure (BP) was measured using a sphygmomanometer on the right arm in a sitting position and after a 20-min rest. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated by dividing weight (in kg) by height2 (in m2). Diabetes, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia were evaluated according to the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, Joint National Committee-7, and National Cholesterol Education Program guidelines. The MetS was diagnosed according to the new International Diabetes Federation definition as: central obesity (defined as waist circumference with ethnicity-specific value ≥90 cm for Indian men) plus any two of the following four factors: (1) raised triglycerides (TGs) ≥150 mg/dL (1.7 mmol/L) or specific treatment for this lipid abnormality, (2) reduced high-density lipoprotein (HDL)-cholesterol <40 mg/dL (1.03 mmol/L), (3) raised BP: systolic BP ≥130 or diastolic BP ≥85 mm Hg or treatment of previously diagnosed hypertension, and (4) raised fasting plasma glucose ≥100 mg/dL (5.6 mmol/L) or previously diagnosed type II diabetes.

Plan of statistical analysis: Logistic/multinomial regression, ANOVA/Chi-square test for univariate analysis and descriptive statistics were used.

Results

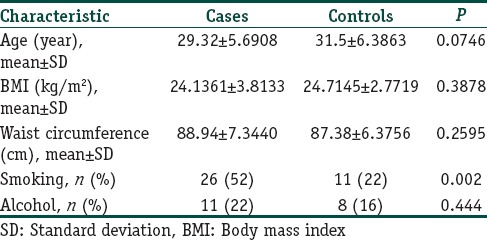

The study included 50 cases and 50 controls. The mean age, anthropometric measurements, and history of addictions are given in Table 1. The mean age of onset of alopecia in our study was 27.08 year. Family history of AGA and hypertension was found significantly higher in 26 (52%) and 29 (58%) cases as compared to 15 (30%) and 18 (36%) controls (P=0.025 and 0.028, respectively). Family history of diabetes and dyslipidemia was found in more number of cases (P=0.130 and 0.695 respectively).

Table 1.

Mean age, anthropometric measurements, and history of addiction of cases and controls

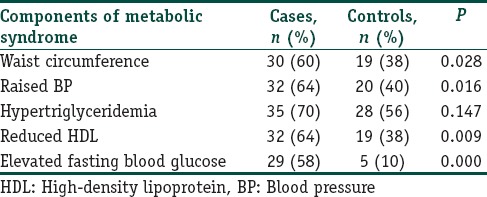

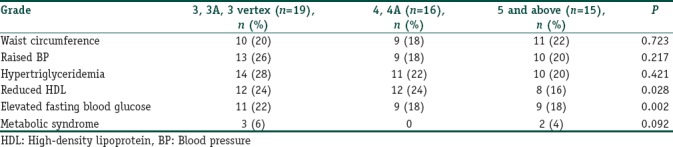

Grade III AGA was found to be most common and was seen in 19 (38%) patients followed by Grade IV in 16 (32%), Grade V in 13 (26%), and Grade VI in 2 (4%). MetS was seen in 5 (10%) cases and 1 (2%) control (P=0.092). Components of MetS among cases and controls have been described in Table 2. Significant differences were present in central obesity, BP, HDL, and fasting blood sugar (FBS) between cases and controls (P=0.028, 0.016, 0.009, and 0.001, respectively). Association of grades of alopecia with MetS and its components has been described in Table 3.

Table 2.

Distribution of components of metabolic syndrome among cases and controls

Table 3.

Association of grades of alopecia with metabolic syndrome and its components

Discussion

Androgenic alopecia (AGA) is an androgen-induced disorder that is characterized by hair loss in genetically predisposed persons. AGA is the most common type of alopecia. AGA as a risk factor for coronary artery disease (CAD) was first suggested by Cotton et al.[4] AGA is manifested by androgen-dependent miniaturization of dermal papillae, a process regulated by complex hormonal mechanisms controlled by local genetic codes. It is not clear whether androgenetic alopecia is genetically homogeneous, and some authorities have suggested that the early onset of alopecia before the age of 36 year is genetically different from the late onset alopecia.[5]

When compared with other studies, we found that the mean age of onset was 28.61 years in Sharma et al.,[6] 26.44 years in Chakrabarty et al.,[7] 27.03 years in Banger et al.,[8] and 40.81 years in Gopinath and Upadya[9] as compared to 29.3 years in our study. Family history of AGA and cardiovascular risk factors was positive in other studies also.[6,7,8,9] Grade III AGA was found to be most common in other studies also like 44% in Chakrabarty et al.,[7] 29% in Banger et al.,[8] and 38% in Gopinath and Upadya.[9]

A few studies have been done on the association of MetS with androgenic alopecia. Arias-Santiago et al. demonstrated MetS in 60% of men with androgenic alopecia (P<0.0001).[10] Other studies[6,7,8,9] showed MetS in approximately 22% of cases as compared to 10% in our study.

Our study found a significant association between elevated plasma glucose and androgenic alopecia (P=0.001). Similar finding was found in Banger et al.[8] and Matilainen et al.,[11] but some other studies[6,7,9] did not find any significant association.

Several studies had indicated that androgenetic alopecia had a higher than normal risk for CAD, but few studies focused specifically on lipid profiles[12] which were important in the pathogenesis of CAD such as total cholesterol, triglyceride, HDL-cholesterol, and low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol in patients with androgenetic alopecia. Many studies had shown a strong association between HDL levels and AGA.[6,7,8,9] Sadighha and Zahed demonstrated lower HDL-cholesterol and higher TG levels in men with vertex-type androgenic alopecia than in controls.[13]

Mineralocorticoid receptors have been found in the skin and hair follicles.[14] However, the role of mineralocorticoids in the skin remained unknown. The role of mineralocorticoid pathways might be a factor in the development of androgenetic alopecia. Essential hypertension is now considered to be associated with primary hyperaldosteronism. It was recently demonstrated that increased aldosterone level within the physiological range predisposed people to the development of hypertension.[15] Many studies had shown a significant association between hypertension and androgenic alopecia.[6,7,9,14,16] Androgenetic alopecia could be considered as a clinical marker of a risk for hypertension.

Abdominal fat tissue is associated with serious metabolic disorders such as hyperinsulinemia, hypertension, increased TG, glucose intolerance, and diabetes mellitus. Some studies had pointed to abdominal fat tissue, calculated by measuring the waist–hip proportion as an independent risk factor for CAD. We did not find a significant association of waist circumference and BMI with AGA. Hirsso et al.[17] and Gopinath and Upadya[9] demonstrated higher BMI and waist circumference in young men with moderate-to-extensive alopecia compared to men with little or no alopecia.

Most studies uniformly concluded that there was definitely certain evidence associating AGA with MetS. However, no evidence in any study so far has linked the severity of AGA and the presence of MetS. Proper large sample studies need to be further conducted for a causal relationship to be established. Moreover, cross-sectional studies such as ours cannot establish a temporal relationship between AGA and MetS.

Conclusion

Higher prevalence of obesity, hypertension, diabetes, and dyslipidemia had been found in patients of early-onset AGA. An association between MetS and early-onset androgenic alopecia was seen which might contribute to the predisposition of patients with androgenic alopecia to develop cardiovascular disease. Early screening and intervention for MetS and its components in patients with early-onset androgenic alopecia may prevent the development of cardiovascular disease.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Thomas J. Androgenetic alopecia – Current status. Indian J Dermatol. 2005;50:179–90. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kamstrup PR, Tybjaerg-Hansen A, Steffensen R, Nordestgaard BG. Genetically elevated lipoprotein(a) and increased risk of myocardial infarction. JAMA. 2009;301:2331–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sinclair RD, Dawber RP. Androgenetic alopecia in men and women. Clin Dermatol. 2001;19:167–78. doi: 10.1016/s0738-081x(00)00128-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cotton SG, Nixon JM, Carpenter RG, Evans DW. Factors discriminating men with coronary heart disease from healthy controls. Br Heart J. 1972;34:458–64. doi: 10.1136/hrt.34.5.458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Matilainen VA, Mäkinen PK, Keinänen-Kiukaanniemi SM. Early onset of androgenetic alopecia associated with early severe coronary heart disease: A population-based, case-control study. J Cardiovasc Risk. 2001;8:147–51. doi: 10.1177/174182670100800305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sharma L, Dubey A, Gupta PR, Agrawal A. Androgenetic alopecia and risk of coronary artery disease. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2013;4:283–7. doi: 10.4103/2229-5178.120638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chakrabarty S, Hariharan R, Gowda D, Suresh H. Association of premature androgenetic alopecia and metabolic syndrome in a young Indian population. Int J Trichology. 2014;6:50–3. doi: 10.4103/0974-7753.138586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Banger HS, Malhotra SK, Singh S, Mahajan M. Is early onset androgenic alopecia a marker of metabolic syndrome and carotid artery atherosclerosis in young Indian male patients? Int J Trichology. 2015;7:141–7. doi: 10.4103/0974-7753.171566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gopinath H, Upadya GM. Metabolic syndrome in androgenic alopecia. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2016;82:404–8. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.174421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arias-Santiago S, Gutiérrez-Salmerón MT, Castellote-Caballero L, Buendía-Eisman A, Naranjo-Sintes R. Androgenetic alopecia and cardiovascular risk factors in men and women: A comparative study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:420–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2009.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matilainen V, Koskela P, Keinänen-Kiukaanniemi S. Early androgenetic alopecia as a marker of insulin resistance. Lancet. 2000;356:1165–6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02763-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arias-Santiago S, Gutiérrez-Salmerón MT, Buendía-Eisman A, Girón-Prieto MS, Naranjo-Sintes R. A comparative study of dyslipidaemia in men and woman with androgenic alopecia. Acta Derm Venereol. 2010;90:485–7. doi: 10.2340/00015555-0926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sadighha A, Zahed GM. Evaluation of lipid levels in androgenetic alopecia in comparison with control group. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23:80–1. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2008.02704.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ahouansou S, Le Toumelin P, Crickx B, Descamps V. Association of androgenetic alopecia and hypertension. Eur J Dermatol. 2007;17:220–2. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2007.0152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vasan RS, Evans JC, Larson MG, Wilson PW, Meigs JB, Rifai N, et al. Serum aldosterone and the incidence of hypertension in nonhypertensive persons. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:33–41. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa033263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arias-Santiago S, Gutiérrez-Salmerón MT, Buendía-Eisman A, Girón-Prieto MS, Naranjo-Sintes R. Hypertension and aldosterone levels in women with early-onset androgenetic alopecia. Br J Dermatol. 2010;162:786–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09588.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hirsso P, Rajala U, Hiltunen L, Jokelainen J, Keinänen-Kiukaanniemi S, Näyhä S, et al. Obesity and low-grade inflammation among young Finnish men with early-onset alopecia. Dermatology. 2007;214:125–9. doi: 10.1159/000098570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]