Abstract

The objectives of this retrospective case series study were to describe a group of 66 dogs with lung lobe torsion (LLT) and to investigate the incidence of complications and risk factors for mortality and overall outcome in this population. Sixty-six dogs with LLT from 3 independent academic institutions were investigated. Information on signalment, history, clinical findings, and interventions was obtained. Associations with mortality outcome were examined via logistic regression. Dogs with a depressed mentation at presentation were 21 times more likely to die than dogs with normal mentation [P = 0.008, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 1.949 to 579.904]. The overall odds of mortality were increased by 18% for each unit change in Acute Patient Physiologic and Laboratory Evaluation (APPLEfast) score (P = 0.04, 95% CI = 0.998 to 1.44). No other clinical abnormalities correlated with outcome.

Résumé

Évaluation des facteurs de risque pour la mortalité chez les chiens souffrant d’une torsion du lobe pulmonaire : étude rétrospective de 66 chiens (2000–2015). Les objectifs de cette étude rétrospective d’une série de cas consistaient à décrire un groupe de 66 chiens ayant une torsion du lobe pulmonaire (TLP) et d’investiguer l’incidence de complications et les facteurs de risque pour la mortalité et les résultats généraux chez cette population. Soixante-six chiens atteints de TLP provenant de trois établissements universitaires indépendants ont été étudiés. Des données ont été obtenues sur le signalement, les résultats cliniques et les interventions. Les associations avec les résultats de mortalité ont été examinées via la régression logistique. Il était 21 fois plus probable que les chiens ayant un état mental déprimé à la présentation meurent que les chiens ayant un état mental normal (P = 0,008, intervalle de confiance [IC] de 95 % = de 1,949 à 579,904). Les probabilités globales de mortalité augmentaient de 18 % pour chaque unité de changement selon la note Acute Patient Physiologic and Laboratory Evaluation (APPLEfast) (P = 0,04, IC de 95 % = de 0,998 à 1,44). Aucune autre anomalie clinique n’offrait de corrélation avec les résultats.

(Traduit par Isabelle Vallières)

Introduction

Lung lobe torsion (LLT) is a rare life-threatening condition that results from the rotation of a lung lobe along its longitudinal axis with twisting of the bronchovascular pedicle at the hilus, causing pulmonary arterial and venous obstruction, thrombosis, and necrosis of the lung lobe (1). Lung lobe torsion is typically an acute condition of dogs that can be fatal without surgical intervention. Pathophysiology is typically described as spontaneous or secondary to underlying thoracic disease or trauma. Diagnosis is most commonly made based on the detection of dyspnea or tachypnea and evidence of pleural effusion with pulmonary consolidation and twisted/truncated bronchi on radiographs. In many cases a more definitive diagnosis can be made based on the results of a thoracic ultrasound examination, computed tomography (CT), or bronchoscopy (2–5), but some cases cannot be confirmed without surgery or necropsy.

Various large and small breed dogs have been reported to develop LLT. Previous studies have found Afghan hounds and pug breeds overrepresented (2,6,7), with Afghan hounds being 133 times more likely to develop LLT than other large breed dogs (6), and male pugs being prone to spontaneous torsion of the left cranial lung lobe (7). Few studies have reported on LLT and the largest study to date included only 22 dogs (6). This study found an overall fair to guarded prognosis with only 68% (n = 15) of dogs surviving to discharge and 33% (n = 5) of these 15 dogs dying of thoracic-related disease within the study period (6). This study was mostly descriptive and to the authors’ knowledge, no risk factors other than breed predisposition were studied or identified against patient outcome. More recent studies found the overall prognosis for LLT to be good to excellent with survival rates to discharge ranging from 86% to 100%; however, these studies included small numbers of dogs and focused on 1 specific breed: notably pugs (7,8). This discrepancy in patient outcome and lack in information on predisposing patient factors prompted this study.

The Acute Patient Physiologic and Laboratory Evaluation (APPLEfast) model is a scoring system for illness severity based on several clinical variables that predict mortality risk and help to provide an objective basis for risk stratification (9–11). Lung lobe torsion does not currently have a diagnosis-specific scoring system and so this diagnosis-independent model was chosen to provide a level of objective standardization among patients’ groups and to determine if the APPLEfast model could be applied to a group of patients with LLT to predict probability of death.

The main objectives of this study were to describe a large group of dogs with LLT and to investigate the incidence of complications and risk factors for mortality and overall outcome in this population.

Materials and methods

Inclusion criteria

Medical records of all dogs with LLT examined at the Ontario Veterinary College (OVC), Western College of Veterinary Medicine (WCVM), and Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine from January 2000 to 2015 were reviewed. Cases were included if a complete medical record (history, clinical signs, imaging, and surgical report, including outcome) was available and if LLT was confirmed at the time of surgery, or necropsy for dogs that were euthanized. Long-term follow-up was obtained when recorded in the medical record.

Data collection

Data retrieved from medical records included age, gender, breed, history, clinical signs, complete blood (cell) count (CBC) and serum biochemistry, pleural fluid cytology, APPLEfast parameters if available (mentation at admission, lactate, glucose, platelets, albumin), diagnostic modalities and results, surgical procedures performed, lung lobe(s) affected, histopathology results, necropsy reports, pleural fluid and/or lung bacterial culture and susceptibility, duration of hospitalization, anesthesia and surgery times, intra- and post-operative complications, and outcome (euthanasia, death, or discharge).

Mentation

Medical records were evaluated and patient mentation at admission was ranked as bright, alert, responsive (BAR), quiet, alert, and responsive (QAR), and depressed (dull, depressed, laterally recumbent, or non-responsive).

APPLEfast score calculation

The APPLEfast score is used to stratify illness severity and risk of mortality in hospitalized animals (8). A number is assigned to each parameter collected from the medical record (mentation at admission, lactate, glucose, platelets, albumin) based on the degree of abnormality, previously established by logistic regression model construction of 598 critically ill dogs, and the sum of these numbers is referred to as the APPLEfast score. For this purpose, separate mentation scores were assigned using the previously published scoring system: 0 = normal; 1 = able to stand unassisted, responsive but dull; 2 = can stand when assisted, responsive but dull; 3 = unable to stand, responsive; and 4 = unable to stand, unresponsive (9). Mentation status was collected at admission before sedation or administration of analgesic, while the lowest abnormal parameter within 24 h of admission and before surgery was collected for all values other than lactate. When available, the highest abnormal parameter within 24 h of admission and prior to surgery was collected for lactate. Each numerical increment or reduction in APPLEfast score is referred to as a unit. Total scores were calculated based on procedures described by Hayes et al (9) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Canine Acute Patient Physiologic and Laboratory Evaluation (APPLEfast) score. The score was calculated by summing the value in the upper left corner of the appropriate cell for each of the 5 parameters listed, with a maximum potential score of 50.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analysis was done using a commercial software (SAS/STAT 9.4; SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA) and descriptive statistics were calculated for many data. Data were assessed for normality and means +/− SD were reported where data were normal, and medians (range) were reported where data were not normal. Differences between means were assessed using Student’s t-test. Fischer’s exact Chi-squared test was used to compare breed prevalence in the study to hospital populations. Differences between medians were assessed using the Mann-Whitney test. Survival data were calculated on dogs that underwent surgery. Dogs euthanized prior to planned surgery were not included in the outcome analysis as a clear reason for euthanasia could not be determined from the records. This was done to prevent confounding variables affecting the statistical analysis since it was unclear whether this decision was due to patient variables (poor condition or prognosis) or non-patient variables (financial, not wanting surgery). Dogs euthanized during or after surgery were included in outcome analyses as euthanasia was elected due to poor clinical progression in all cases. Survival was related to the APPLEfast score via logistic regression. Odds ratios and 95% CIs were calculated for prevalence data. A P-value ≤ 0.05 was considered significant.

Outcome

Outcome was divided into death or discharge. Death was classified as preoperative, intraoperative, or postoperative and cause of death (cardiopulmonary arrest or euthanasia) was recorded. Reason for euthanasia was recorded when possible. Dogs discharged were further categorized as being alive or dead at the time of follow-up. If dogs had died, further classification into disease and non-disease related death was made. All postoperative complications were recorded. If the complication developed post-discharge, it was considered a long-term complication.

Results

Sixty-six cases of LLT met the criteria for inclusion in the study (OVC = 33, WCVM = 22, and Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine = 11). Mean age was 5.85 y +/− 3.239 (range: 0.25 to 12.6 y). Fifty-five dogs were purebred, representing 28 breeds, the major ones being 21 pugs, 3 Afghan hounds, 3 Labrador retrievers, 2 borzois, 2 golden retrievers, 2 shih-tzus. The remaining 11 (17%) were mixed-breed. Median weight was 13 kg (range: 1.13 to 60 kg, mean = 19.57 kg). Thirty-five (53%) dogs were small breed (< 15 kg). Twenty-one (60%) small breed dogs were pugs, which were significantly overrepresented (P = 0.001) compared with the hospital population. There was no significant difference in outcome based on breed or dog weight in this study (P = 0.31).

Clinical abnormalities

Clinical signs at presentation included dyspnea (n = 28, 42%), anorexia (n = 53, 80%), cough (n = 28, 42%), lethargy (n = 57, 86%), and vomiting (n = 6, 9%). Median duration of clinical signs before presentation at the teaching hospital was 5 d (range: 1 to 22 d, mean = 7.7 d). Four dogs (6%) had a reported history of trauma. Abnormal physical examination findings included dull cardiopulmonary auscultation (n = 60, 91%), tachypnea (n = 40, 61%), pyrexia (n = 19, 29%) and a depressed mentation (n = 11, 17%). One dog with depressed mentation was euthanized before planned surgery (no clear reason was noted in the medical record) and was therefore omitted from analysis. Of the remaining 10 dogs, 3 died before surgery or immediately after surgery from cardiopulmonary arrest and 5 were successfully discharged. The remaining 2 dogs were euthanized after surgery and before discharge due to clinical deterioration associated with a chylothorax (n = 1) and pneumothorax (1). There was an association between abnormal mentation (depressed versus normal) and disease-related euthanasia or death (Figure 2). Dogs with a depressed mentation were 21 times more likely to die than dogs with a normal mentation (P = 0.008; 95% CI = 1.95 to 579.90). No other clinical abnormalities were associated with outcome.

Figure 2.

Outcome of dogs (n = 60) based on mentation at time of presentation.

Clinicopathologic findings

A CBC and biochemistry profile performed within 24 h of admission was available for 59 of 66 dogs. Abnormalities included neutrophilia (n = 50), anemia (n = 30), hypoalbuminemia (n = 28), elevated alkaline phosphatase (n = 22), bilirubinemia (n = 16), hyperglycemia (n = 10), hypercholesterolemia (10), elevated alanine aminotransferase (n = 7), thrombocytopenia (n = 4), and hemorrhage (n = 1). Hyperlactatemia was not evaluated in previous studies and lactate concentration was found to be elevated (> 2 mmol/L) in 35% of cases before surgery. High lactate was not associated with death (P = 0.06; OR = 8.34; 95% CI = 0.92 to 229.59).

Pleural fluid was obtained before surgery by thoracocentesis in 37 dogs. Examination of the pleural fluid revealed non-degenerate neutrophils, mild to moderate hemorrhage with macrophages, lymphocytes, and small reactive mesothelial cells in 36 dogs. Chylothorax was diagnosed in 6 dogs based on triglyceride levels. Cytology inconsistent with a LLT was noted in 1 dog in which coccoid bacteria and large hyperplastic mesothelial cells were identified. Pleural fluid and/or lung samples from 31 dogs were submitted for culture, and 2 had bacterial growth; organisms identified were Streptococcus canis and Staphylococcus pseudintermedius.

APPLEfast

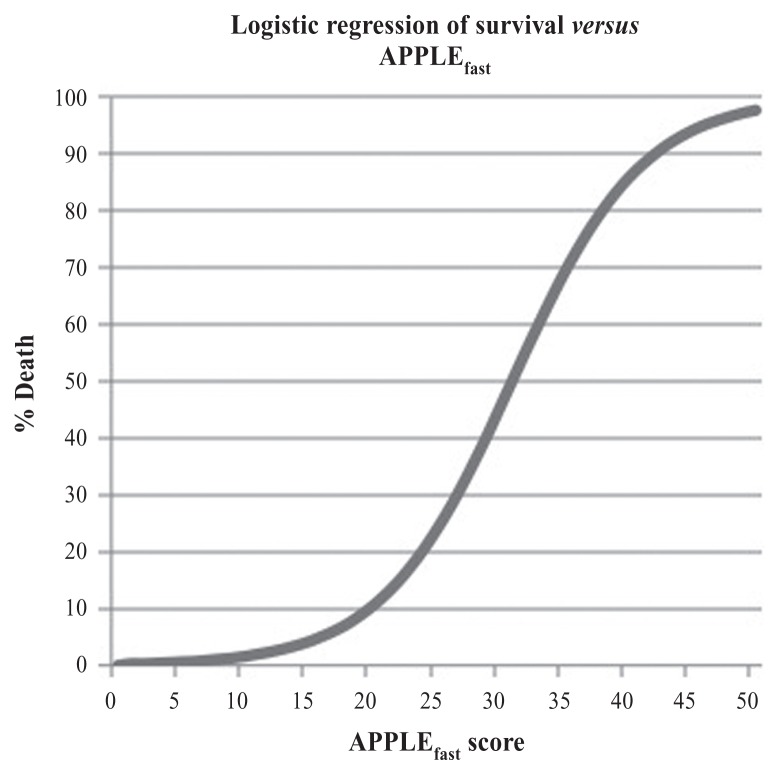

APPLEfast was performed for all dogs for which required data were available, but several patients did not have a recorded lactate value. Mentation was available in 66 of 66 dogs, while lactate was available in only 37 of 66 dogs. As such, a total of 37 APPLEfast scores were calculated in this study (Table 1). Three cases were excluded from analysis as cause for euthanasia could not be determined, resulting in a total of 34 APPLEfast scores. Median APPLEfast score was 20 (range = 12 to 34; mean = 21.5). Overall, the odds of disease related death increased by 18% for each unit increase in APPLEfast score (P = 0.04; 95% CI = 1.03 to 1.44) (Figure 3).

Table 1.

Data retrieved for calculation of APPLEfast scores.

| Case number | Mentation score | Lactate (mmol/L) | Lactate score | Glucose (mmol/L) | Glucose score | Platelet (×109/L) | Platelet score | Albumin (g/L) | Albumin score | APPLEfast (max = 50) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 6 | 9.6 | 8 | 6.5 | 9 | 446 | 1 | 23 | 8 | 32 |

| 2 | 7 | 8.5 | 8 | 2.6 | 7 | 271 | 0 | 33 | 0 | 22 |

| 3 | 4 | 4.4 | 4 | 3.9 | 7 | 658 | 1 | 20 | 8 | 24 |

| 4 | 4 | 4.1 | 4 | 7.1 | 9 | 428 | 1 | 26 | 7 | 25 |

| 5 | 6 | 3.9 | 4 | 8.8 | 9 | 223 | 3 | 32 | 6 | 28 |

| 6 | 4 | 3.2 | 4 | 9.2 | 10 | 5 | 5 | 25 | 8 | 31 |

| 7 | 4 | 3.2 | 4 | 4.7 | 8 | 282 | 0 | 29 | 7 | 23 |

| 8 | 14 | 2.6 | 4 | 5.7 | 9 | 167 | 6 | 33 | 0 | 33 |

| 9 | 0 | 2.56 | 4 | 5.3 | 8 | 112 | 5 | 31 | 6 | 23 |

| 10 | 7 | 2.4 | 4 | 5.8 | 9 | 198 | 6 | 21 | 8 | 34 |

| 11 | 0 | 2.3 | 4 | 6.8 | 9 | 299 | 0 | 33 | 0 | 13 |

| 12 | 4 | 2.2 | 4 | 5.6 | 8 | 130 | 5 | 23 | 8 | 29 |

| 13 | 0 | 2.2 | 4 | 9.1 | 10 | 291 | 0 | 25 | 8 | 22 |

| 14 | 7 | 1.9 | 0 | 5.1 | 8 | 427 | 1 | 24 | 8 | 24 |

| 15 | 0 | 1.8 | 0 | 5.2 | 8 | 472 | 1 | 29 | 7 | 16 |

| 16 | 4 | 1.8 | 0 | 6.5 | 9 | 260 | 3 | 32 | 6 | 22 |

| 17 | 4 | 1.7 | 0 | 4.5 | 7 | 298 | 0 | 28 | 7 | 18 |

| 18 | 4 | 1.64 | 0 | 4.5 | 7 | 151 | 6 | 27 | 7 | 24 |

| 19 | 0 | 1.5 | 0 | 5.4 | 8 | 437 | 1 | 30 | 7 | 16 |

| 20 | 4 | 1.5 | 0 | 6.8 | 9 | 271 | 0 | 31 | 6 | 19 |

| 21 | 4 | 1.4 | 0 | 5.1 | 8 | 470 | 1 | 28 | 7 | 20 |

| 22 | 0 | 1.3 | 0 | 7 | 9 | 93 | 5 | 18 | 8 | 22 |

| 23 | 4 | 1.2 | 0 | 5.1 | 8 | 356 | 0 | 24 | 8 | 20 |

| 24 | 0 | 1.2 | 0 | 8.3 | 9 | 381 | 0 | 27 | 7 | 16 |

| 25 | 4 | 1.15 | 0 | 4.3 | 7 | 299 | 0 | 20 | 8 | 19 |

| 26 | 0 | 1.1 | 0 | 5.7 | 8 | 794 | 1 | 31 | 6 | 15 |

| 27 | 4 | 1.05 | 0 | 4.8 | 8 | 368 | 0 | WNL | 0 | 12 |

| 28 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 5 | 8 | 362 | 0 | 25 | 8 | 20 |

| 29 | 4 | 0.95 | 0 | 6.6 | 9 | WNL | 0 | 36 | 2 | 15 |

| 30 | 4 | 0.9 | 0 | 5.7 | 9 | 269 | 0 | 32 | 6 | 19 |

| 31 | 4 | 0.62 | 0 | 4.9 | 8 | 236 | 3 | 33 | 0 | 15 |

| 32 | 0 | 0.6 | 4 | 5 | 8 | 376 | 0 | 30 | 7 | 19 |

| 33 | 4 | 0.57 | 0 | 6.1 | 9 | 191 | 6 | 27 | 7 | 26 |

| 34 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6.8 | 9 | 351 | 0 | 32 | 6 | 15 |

WNL — within normal limits.

Figure 3.

Logistic regression of survival versus APPLEfast.

Diagnostic imaging

Thoracic radiographs were taken in all dogs. Radiographs revealed pleural effusion in 54 dogs and were considered diagnostic for LLT according to the imaging reports in 16 (24%) dogs. Ultrasound was performed in 28 dogs and was considered diagnostic for LLT in 5 (18%) dogs. Computed tomography (CT) scan was performed in 17 dogs and was considered diagnostic for LLT in 13 (76%) dogs. Six dogs had all 3 imaging modalities performed prior to surgery. Bronchoscopy was performed in 12 dogs and was considered diagnostic in 6 (50%).

Treatment

Seven (10.6%) dogs died (n = 2) or were euthanized (n = 5) before surgery due to poor prognosis, poor condition, and/or financial reasons. The remaining 59 (89.4%) dogs were treated surgically. Surgical approach for these dogs included an intercostal thoracotomy (n = 56, 84.9%) or median sternotomy (n = 3, 4.5%). Lung lobectomy was performed with a thoracoabdominal (TA) stapler (n = 44), ligatures (n = 4), hand sewn (n = 4), TA stapler and ligatures (n = 5), and TA stapler and hand sewn (n = 2). The lobes affected and removed at the time of surgery included the left cranial lung lobe (n = 30), the right middle lung lobe (n = 22), the right cranial lung lobe (n = 4), and the left caudal lung lobe (n = 3). Pugs more frequently had the left cranial lung lobe affected (n = 18, 90%) compared to the right middle lung lobe (n = 2, 10%). Median anesthesia time for diagnostic and surgical procedures, including other surgical procedures such as thoracic duct ligation and diaphragmatic hernia repair where required, was 180 min (range: 75 to 570 min) and median surgery time was 90 min (range: 45 to 480 min).

Histology

Lung lobes from 57 dogs were submitted for histopathology. Findings, including hemorrhage, thrombosis, and necrosis, were consistent with LLT in 56 dogs. No histological diagnosis was recorded in the remaining report, but medical records including the surgery report and discharge statement confirmed the diagnosis of LLT.

Outcome

Of the 59 (89.4%) dogs that underwent treatment following diagnosis, 8 (13.6%) died during surgery (n = 3) or after surgery (5). Of these, 3 dogs suffered cardiopulmonary arrest and 5 were euthanized at the owner’s request due to complications or secondary to other thoracic disease (chylothorax = 2, pneumothorax = 1, bronchoalveolar carcinoma = 1, sepsis due to pyothorax = 1) resulting in a perceived poor prognosis.

Postoperative complications occurred before discharge in 14/59 (24%) dogs. These included chylothorax (n = 3, 21%), pneumothorax (n = 6, 43%), and non-chylous pleural effusion (n = 4, 29%). Chylous effusion was diagnosed based on a high triglyceride ratio between the thoracic effusion and serum. One dog with persistent severe hypotension presumably caused by a septic pyothorax failed to recover from anesthesia and was euthanized at the owner’s request due to a poor prognosis. Patients were excluded from outcome calculations if any complications were identified before surgery or if complications developed after discharge.

Of the 6 dogs with preoperative chylothorax, 1 was euthanized before planned surgery and 2 were euthanized after surgery because of a perceived poor prognosis. One dog that had persistent chylothorax after surgery underwent thoracic duct ligation 8 d later and was successfully discharged. One dog had no evidence of persistent chylothorax immediately after surgery, but it recurred 2 wk later. This dog was not treated and was clinically normal at the time of follow-up 3 mo later. One dog underwent thoracic duct ligation at the time of surgery and was discharged without recurrence.

Three dogs without a previous diagnosis of chylothorax developed it after surgery. Two developed chylothorax immediately after surgery and were euthanized without treatment and the third was euthanized 1 month after due to congestive heart failure and renal failure.

Pneumothorax was identified in 6 dogs after surgery with no confirmed cause noted in the medical record. Five of these dogs were successfully discharged following management in hospital with a chest tube for 3 to 6 d before discharge from hospital. The 6th dog was euthanized after surgery due to persistent pneumothorax and a perceived poor prognosis.

Four dogs developed non-chylous pleural effusion after surgery. One resolved 10 d after diagnosis without further treatment. Two dogs were euthanized due to failure to respond to treatment and 1 was managed for 2 mo until it was lost to follow-up. One dog underwent cardiac arrest 1 mo after surgery and was diagnosed on postmortem histopathology with granulomatous blastomycosis.

Long-term complications developed in 5 dogs following discharge from the hospital and included chylothorax (n = 2) and LLT recurrence (n = 3). One dog developed chylothorax 5 mo after surgery, underwent no further treatment, and was doing well at follow-up 2 y later. The other dog was diagnosed with chylothorax by thoracocentesis 3 y after LLT and was discharged without any report of recurrence in 10 y after thoracocentesis. One dog underwent thoracotomy for a second lung lobe torsion (left cranial) 6 mo following right cranial lung lobectomy. Two dogs had radiographs suspicious for recurrent LLT 8 wk and 6 mo after surgery, but were euthanized due to a perceived poor prognosis associated with the need for a second surgery. A postmortem examination was not permitted in either case. Both dogs were suspected to have had a right middle lung lobe torsion following a previous left cranial lung lobectomy.

Fifty-one of the 59 dogs (86%) dogs survived until discharge, 10 of which were alive at the time of data collection and 15 of which had died from causes unrelated to LLT. Of the 8 dogs that did not survive to discharge, 5 were euthanized for reasons that could have been addressed medically or surgically. The remaining cases (n = 26) were lost to follow-up.

Discussion

Overall outcome of LLT with timely and appropriate surgical treatment was found to be very good in this study. Eighty-six percent of dogs that underwent treatment in this study were discharged. Clinicopathologic findings reported herein were consistent with previous reports (6–8,12–14,17), none of which individually were associated with patient outcome. Mentation status was found to have a significant association with outcome in this study, whereby dogs with a depressed mentation were 21 times more likely to die or be euthanized for poor doing than dogs that had normal mentation (P = 0.004; 95% CI = 1.95 to 579.90) (Figure 2). Although mentation is a subjective measure in veterinary medicine, the APPLEfast model provided more objective criteria, including ability to ambulate and respond to the surrounding environment, to help eliminate clinician variability in assessment of this non-numerical parameter.

The APPLEfast model is a scoring system that predicts the probability of death based on a combination of clinical findings that have been previously identified as factors associated with survival prediction index (9–12). The APPLEfast can provide the researcher with an objective illness severity measure (9). Only 37 APPLEfast scores were obtained for dogs in this study because several dogs did not have a recorded lactate level. Most of the missing lactate data was from one institution in which lactate levels were unfortunately not included in the paper record during the study period. The absence of this data is therefore less likely to have been related to the severity of illness and is less likely to have biased the results.

Our results revealed that the odds of mortality were increased by 18% for each unit change in APPLEfast score (P = 0.04, 95%; CI = 1.03 to 1.44) (Figure 2). Dogs with an elevated lactate concentration (> 2 mmol/L) tended to die more frequently (Table 1); however, this difference was not significant (P = 0.06), likely due to lack of power resulting in a type II error. None of the other variables studied were associated with outcome.

Thoracic radiographs revealed pleural effusion in most of the dogs (83%) but were only considered to be diagnostic for LLT in 30%. Thoracic CT resulted in the greatest frequency of a positive diagnosis for LLT (76%) but was not used as much as ultrasound due to its less frequent availability, relatively higher cost, and need for sedation or general anesthesia. Compared to previous studies (6), ultrasound was not often considered diagnostic for LLT in this study (5/28 cases). This can be attributed to selection criteria whereby a definitive diagnosis of LLT recorded in the radiology report was required in this study to confirm an LLT. Despite the lack of formal diagnosis obtained using these imaging modalities, many dogs had surgery following radiographs and ultrasound with a suspicion for LTT. Therefore, although CT was more useful in obtaining a definitive diagnosis of lung lobe torsion in this study (13/17 cases), combined thoracic radiographs and ultrasound provided sufficient information to warrant thoracic exploration with definitive diagnosis obtained at the time of surgery.

Pleural fluid or samples from the affected lung lobes were obtained and submitted for culture in 31 dogs. Only 6% of the submitted cultures were positive for bacterial growth. This is markedly different from a previous study in which 60% of cultures submitted yielded bacterial growth (6). These differences may be attributed to a different study population, differences in duration of torsion, or variation in sample collection or culture techniques. Although the exact pathophysiology of LLT is not understood, this study supports that underlying infection is not a common risk factor for the development of LLT.

Pugs, which have been previously identified as a predisposed breed (7,8,15), were significantly overrepresented as a small breed in this study. Previous studies have identified an association between breed and the torsed lobe, with the right middle lung lobe most commonly affected in large breed dogs (16), and the left cranial lung lobe more commonly affected in pugs (7,8,15). This was also true in the current study. However, breed or dog size (large versus small) had no association with outcome in this study (P = 0.31).

Four dogs (6%) in this study had a history of thoracic trauma and 14 had identified concurrent thoracic disease (chylothorax = 6, spontaneous pneumothorax, and aspiration pneumonia = 2 each, traumatic pneumothorax bronchoalveolar carcinoma, pyothorax, and smoke inhalation = 1 each). The remaining 47 (71%) cases were classified as spontaneous LLT because no histologic evidence of underlying disease was present. These percentages are similar to previously reported cases of spontaneous lung lobe torsion (6,7).

Acute or persistent chylothorax has been identified as a common concurrent thoracic condition with LLT (6,14). Although several causes have been identified including neoplasia, trauma, and heart disease, in many cases chylothorax is considered idiopathic (18). In the present study, 3 cases not documented to have chylothorax before surgery developed chylothorax after surgery. In these cases, it is possible that the pleural effusion was not consistent with chylous effusion pre-surgery and led to an incorrect diagnosis due to the LLT confounding the cytologic characteristics of the pleural effusion. It is difficult to assess whether LLT caused disruption to the thoracic duct resulting in chylothorax, or vice versa without knowing whether chylothorax was in fact present pre-surgery. Of 9 cases with chylothorax in this study, 8 had surgery for lung lobectomy. Chylothorax resolved in 75% of dogs and thoracic duct ligation was only performed in 25% (2 of 8 dogs). The remaining 4 dog owners elected no further treatment and no recurrence of chylothorax was reported. Previous literature found an association between chylothorax and outcome; however, more recent studies, including the present study, have found this not to be true (6). One must, however, consider that some dogs with chylothorax were euthanized due to non-patient factors (financial, emotional) and therefore an actual overall outcome is unknown. No significant correlation was found between trauma, previous thoracic surgery, concurrent thoracic conditions, and overall patient outcome in this study.

Limitations of this study are related to its retrospective nature in that clinical data collected (specifically lactate levels), imaging interpretation, surgeon technique, postoperative management, and follow-up were not uniform among institutions. Multiple institutions were involved in this study in order to obtain a larger sample size, which resulted in greater variability in methods of diagnosis, treatment, and management of cases. Despite including 3 times more cases than the largest previously published report, lack of power to detect associations between other risk factors and outcome was likely a limitation given so few dogs had a negative (death or complication) outcome after surgery in this study which limits the precision of estimation of effect and could be misleading. This is supported by the wide confidence intervals reported for the odds ratios in this study.

To date, no study has reported on a large number of dogs with LLT. This study confirmed the ability of the APPLEfast score, which is a diagnosis-independent illness severity score, to predict outcome in this population when required data were available in the medical record. The APPLEfast score is currently meant for assessment of populations and is not considered an accurate predictor of individual cases. This study also identified depressed mentation as a risk factor for poor outcome in dogs with LLT; however, caution should be exercised regarding the use of this parameter to guide prognosis and client decision-making in clinical practice since depression can be subjective, and may be affected by factors other than LLT itself. CVJ

Footnotes

Use of this article is limited to a single copy for personal study. Anyone interested in obtaining reprints should contact the CVMA office (hbroughton@cvma-acmv.org) for additional copies or permission to use this material elsewhere.

References

- 1.Moon M, Fossum TW. Lung lobe torsion. In: Bonagura JD, editor. Kirk’s Current Veterinary Therapy XII: Small Animal Practice. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: WB Saunders; 1995. pp. 919–921. [Google Scholar]

- 2.D’Anjou A, Tidwell AS, Hecht S. Radiographic diagnosis of lung lobe torsion. Vet Radiol Ultrasound. 2005;46:478–484. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-8261.2005.00087.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Seiler G, Schwarz T, Vignoli M, Rodriguez D. Computed tomographic features of lung lobe torsion. Vet Radiol Ultrasound. 2008;49:504–508. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-8261.2008.00435.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shultz RM, Peters J, Zwingenberger A. Radiography, computed tomography and virtual bronchoscopy in four dogs and cats with lung lobe torsion. J Small Anim Pract. 2009;50:360–363. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-5827.2009.00728.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moses BL. Fiberoptic bronschoscopy for diagnosis of lung lobe torsion in a dog. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1980;176:44–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Neath PJ, Brockman DJ, King LG. Lung lobe torsion in dogs: 22 cases (1981–1999) J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2000;217:1041–1044. doi: 10.2460/javma.2000.217.1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murphy KA, Brisson BA. Evaluation of lung lobe torsion in Pugs: 7 cases (1991–2004) J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2006;228:86–90. doi: 10.2460/javma.228.1.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rooney MB, Lanz O, Monnet E. Spontaneous lung lobe torsion in two pugs. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 2001;37:128–130. doi: 10.5326/15473317-37-2-128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hayes G, Mathews K, Doig G, et al. The acute patient physiologic and laboratory evaluation (APPLE) score: A severity of illness stratification system for hospitalized dogs. J Vet Intern Med. 2010;24:1034–1047. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-1676.2010.0552.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.King LG, Stevens MT, Ostro EN. A model for prediction of survival in critically ill dogs. J Vet Emerg Crit Care. 1994;4:85–99. [Google Scholar]

- 11.King LG, Wohl JS, Manning AM, Hackner SG, Raffe MR, Maislin G. Evaluation of the survival prediction index as a model of risk stratification for clinical research in dogs admitted to intensive care units at 4 locations. Am J Vet Res. 2001;62:948–954. doi: 10.2460/ajvr.2001.62.948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lord PF, Greiner TP, Greene RW, DeHoff WD. Lung lobe torsion in the dog. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 1973;9:473–482. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Williams JH, Duncan NM. Chylothorax with concurrent right cardiac lung lobe torsion in an Afghan Hound. J S Afr Vet Assoc. 1986;57:35–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnston GR, Feeney DA, O’Brien TD, et al. Recurring lung lobe torsion in three Afghan Hounds. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1984;184:842–845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gelzer AR, Downs MO, Newell SM, Mahaffey MB, Fletcher J, Latimer KS. Accessory lung lobe torsion and chylothorax in an Afghan hound. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 1997;33:171–176. doi: 10.5326/15473317-33-2-171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Spranklin DB, Gulikers KP, Lanz OI. Recurrence of spontaneous lung lobe torsion in a pug. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 2003;39:446–451. doi: 10.5326/0390446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gallanger LA. Lung lobe torsion. In: Bojrab MJ, editor. Disease Mechanisms in Small Animal Surgery. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Lea & Febiger; 1993. pp. 386–387. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Birchard SJ, McLoughlin MA, Smeak DD. Chylothorax in the dog and cat: A review. Lymphology. 1995;28:64–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]