Abstract

Objective

We present 11 patients with distant metastases to the head and neck from an infraclavicularly located primary tumor and discuss the management strategies including the clinical presentation, treatment modalities, and prognosis.

Methods

The retrospective data of the pathology reports and operation notes of 1239 patients who had undergone any kind of oncological surgical intervention between 2005 and 2017 were analyzed. All of the 11 patients included in the study were evaluated in our department’s tumor board, and all patients with an operable lesion had undergone surgery. Inoperable patients were treated with chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy.

Results

The average age of the patients was 64.3 (48–88) years. Primary tumors were located in the lung (2), breast (2), ovary (2), prostate (2), kidney (1), and colon (1) and the primary lesion could not be determined in one patient. The most common symptom was newly occurred painless swelling (9/11, 81.8%) at the metastatic site. Four patients without any other distant metastases were operated. Of these four patients, two died during follow-up due to systemic disease, and the other two are alive and disease-free. Three of the seven inoperable patients were treated with chemotherapy and the other four with radiotherapy. The prognosis of this group was worse.

Conclusion

Although metastasis to the head and neck is not common, it is vital to keep in mind while approaching a patient with a lesion at the head and neck region especially if there is a history of lung, breast, and genitourinary cancers. Despite the poor prognosis, diminishing the tumor burden would increase the treatment success.

Keywords: Atypical metastasis, head and neck malignancies, surgical oncology, distant metastasis

Introduction

Malignancies of the head and neck region are the most common primary tumors of the local anatomical structures. These tumors generally present with cervical lymphadenopathies before the primary tumor is symptomatic. The metastasis pattern of head and neck malignancies is usually predictable. When the primary tumor cannot be clearly identified, cervical lymphadenopathy may create a diagnostic dilemma. If malignancy suspicion is present pan-endoscopy, fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC), and imaging modalities are necessary for the detection of the primary tumor localization. If the primary lesion cannot be determined and histopathological evaluation of the lymph node does not yield any result, the investigation should be expanded beyond the head and neck (1).

Metastases to the head and neck region from any organ below the inferior border of the neck are not frequently seen and are generally associated with progressive primary disease. Primary tumors that metastasize to a supraclavicular location generally originate from the breast, lung, kidney, prostate, uterus, stomach, and colon (2). Furthermore, these tumors may occasionally present as supraclavicular metastases at an early stage without showing any other signs and symptoms of the primary disease. In approximately 25%–30% of the patients, metastases to the head and neck region can be the first presentation of an occult cancer (3). This condition depends on the biological behavior of the tumor rather than its incidence (2–4). Metastatic disease of the head and neck may cause confusion among physicians and should be considered in the differential diagnosis of primary malignancies of the head and neck region. At this point, the definitive diagnosis can be achieved by simultaneous biopsies from both the mass and the primary tumor (2, 4).

In the present study, we present 11 patients with distant metastases to the head and neck from an infraclavicularly located primary tumor and discuss the management strategies including the clinical presentation, treatment modalities, and prognosis.

Methods

Ethical approval was obtained from the Istanbul School of Medicine Ethics Committee for Scientific Research (No. 2018/363). A total of 1239 retrospective case records and pathology reports of the patients who were treated at our tertiary clinic between January 2005 and March 2017 were revieved. Inclusion criteria of the study were determined as histopathologically proven distant metastases to the head and neck region from an infraclavicularly located primary tumor. Eleven patients who were diagnosed with metastatic disease of the head and neck that originated from an infraclavicular region were enrolled in the study. Patients with a diagnosis of lymphoma or any other hematological malignancies and a history of primary head and neck cancer treatment were excluded from the study. Patients who had metastatic diseases that cannot be histopathologically verified and patients with supraclavicular fossa metastases were also excluded.

Epidemiological information, locations of both the primary tumors and the metastases, symptoms, treatment modalities, and follow-up data were acquired from the patients’ charts. All of the patients were evaluated by otolaryngologists, oncologists, pathologists, and radiologists, and the treatment modalities were selected by considering stage and prognosis of primary tumor, patients’ general health status, operability of head and neck metastases, and patient consent. If applicable, excision of the metastasis with adjuvant radiotherapy was the first choice of treatment except metastasis to the nasopharynx. When the surgical excision was not suitable, primary radiotherapy with or without chemotherapy was the choice of treatment for head and neck metastases. Patients who were not suitable for radiotherapy or surgery and who have sufficient general health conditions were treated with chemotherapy protocols appropriate for the pathological diagnosis of the primary tumor.

Results

There were four female and seven male patients. The mean age of the patients was 64.3±12.1 (range, 48–88) years at the time of presentation. Table 1 shows the history, physical examination findings, locations of both the primary tumors and the metastases, treatment modalities, and prognosis of each patient.

Table 1.

Detailed data of the patients in the study

| No. | Age (years) | Sex | History | Physical examination | Primary disease | H&N metastasis region | Systemic metastases | Treatment modality | Prognosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 61 | M | Nephrectomy and retroperitoneal lymph node dissection 20 years ago | Tender and hemorrhagic mass on the free end of the tongue for 2 months | Renal cell carcinoma (clear cell variant) PAX-8 (+) |

Tongue | No | Partial glossectomy + radiotherapy | Patient died 8 months after surgery due to systemic disease |

| 2 | 58 | M | Hemicolectomy+ partial liver resection 9 months before | Newly formed hemorrhagic mass on the lateral side of the tongue | Colon adenocarcinoma p-ANCA and CDX2 (+) |

Tongue | Lungs, neck, intra-abdominal lymph nodes | Palliative chemotherapy | Patient is alive at 3 months after diagnosis |

| 3 | 48 | F | Left-sided modified radical mastectomy and axillary node clearance for breast cancer 14 years ago. Presented with hoarseness, cough, and swelling on the neck for several months | A 25×20 mm solid, non-tender mass at the level 4 of the left neck Left vocal fold paralysis MRI showed a dense homogeneous mass that surrounded the common carotid artery 360° |

Breast ductal carcinoma metastases ER 80% PR 90% Cerb-B2 positivity in 20% HER-2 (+) |

Left neck, level 4 | Left subpectoral area | Radiotherapy to the neck and systemic Trastuzumab therapy | Patient was alive, and the disease was under control at 18 months of follow-up* |

| 4 | 64 | F | Bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy +total abdominal hysterectomy 2 years ago | Solid, immobile and painless mass at the level 3 of the right neck for 2 months | Ovarian serous adenocarcinoma PAX-8 (+) Wt 1 (+) |

Right neck, level 3 | No | Functional neck dissection+ adjuvant radiotherapy | Patient was alive and free of disease at 2 years of control |

| 5 | 72 | F | Patient, receiving chemotherapy for an inoperable ovarian carcinoma | A firm, painless and immobile solid mass was palpated at the level 4 of the left neck | Ovarian serous adenocarcinoma (FNAB) PAX-8 (+) Wt 1 (+) |

Left neck, level 4 | Diffuse metastases to intraperitoneal lymph nodes, peritoneum, bowels, and neck | Palliative chemotherapy | Patient died 1 month after diagnosis |

| 6 | 52 | F | Modified radical mastectomy and axillary node clearance 2 years ago. Presented with lesion and skin retraction on the right cheek | A deep retraction was present on the right cheek. The lesion was extending to the oral mucosa and invading the base of the right maxillary sinus | Lobular breast cancer ER 90% PR 90% Cerb-B2 positivity in 10% HER-2 (+) |

Right cheek, buccal mucosa, and maxillary sinus | No | En-bloc tumor resection with radical neck dissection+ trastuzumab therapy | Patient was alive and free of disease at 18 months of control |

| 7 | 88 | M | No known history of any other malignant diseases. Presented with hoarseness for 1 month | A subglottic, polypoid mass and erythroplakia on the right vocal cord was observed | Undifferentiated carcinoma** Focal PAP (+) |

Larynx, subglottis, and right vocal fold | No | Total laryngectomy was not planned due to advanced age. Patient was referred to the oncology clinic for palliative chemotherapy | Patient was still alive at 20 months of follow-up. Disease was at remission. Subglottic lesion regressed with chemotherapy |

| 8 | 77 | M | Chemotherapy for lung adenocarcinoma 6 months prior to parotid gland swelling | Painless swelling at the right parotid gland | Lung adenocarcinoma TTF-1 (+) |

Parotid gland | No | Radiotherapy for the primary tumor and chemoradiotherapy for parotid metastases | Patient died 4 months after biopsy was performed from the parotid gland |

| 9 | 72 | M | Radical prostatectomy 3 years ago, under hormonotherapy | PET-CT scan revealed high 18-FDG uptake at the nasopharynx. Endoscopic examination revealed a solid mass at the right Rosenmuller fossa | Prostatic adenocarcinoma PAP (+) PAS (+) |

Nasopharynx | Multiple bone metastases | Palliative chemotherapy | Patient was alive at 1 month of control |

| 10 | 64 | M | Radical prostatectomy 8 years ago + chemotherapy | A solid, immobile and painless mass at the level 3 of the right neck was present | Prostatic adenocarcinoma PAP (+) PAS (+) |

Right neck, level 3 | No | Right radical neck dissection + chemotherapy | Patient died 2 years after surgery |

| 11 | 79 | M | Presented with a solid mass at the thyroid gland. No known history of any other malignant disease | A 4×3.7 cm solid mass was present at the inferior part of the right thyroid lobe | Lung adenocarcinoma TTF-1 (+) Cytokeratin-7 (+) |

Thyroid gland | Bilateral neck, axilla, intra-abdominal, iliac lymph chains | Referred to the Thorax Surgery department for primary disease. Radiotherapy for the neck | No follow-up data are present |

PAX-8: paired box gene-8; p-ANCA: Perinuclear Anti-Neutrophil Cytoplasmic Antibodies; ER: estrogen receptor; PR: progesteron receptor; HER-2: human epidermal growth factor receptor-2; Wt-1: Wilms tumor-1; PAP: prostatic acid prostatic acid phosphatase; TTF-1: thyroid transcription factor-1; PAS: periodic acid-schiff

Primary tumors were located in the lung (n=2), breast (n=2), ovary (n=2), prostate (n=2), kidney (n=1), and colon (n=1). In one patient with an undifferentiated carcinoma in the larynx, despite all examination, primary tumor localization could not be determined. This case was considered as a metastatic tumor of unknown primary lesion because of its immunohistochemical characteristics. The histological types of other tumors were adenocarcinoma of the lung, adenocarcinoma and undifferentiated carcinoma of the prostate, clear cell carcinoma of the kidney, ductal and cylindroid type adenocarcinoma of the breast, serous adenocarcinoma of the ovary, and adenocarcinoma of the colon. Five patients had also distant metastasis other than the head and neck area, but in the other six patients, the head and neck region was the lone metastasis location.

The most common symptom was newly onset painless swelling at the metastatic site, which was present in 9 (81.8%) out of 11 patients. Of these nine patients, four had metastatic disease in the lymph nodes in the neck, two in the tongue (Figure 1), one in the parotid gland (Figure 2), and one in the thyroid gland. One patient had subglottic larynx metastasis (Figure 3) causing hoarseness, one patient had painless skin retraction due to buccal mucosa metastasis (Figure 4), and one patient had asymptomatic nasopharynx metastases determined during positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) scanning. Metastatic disease was verified histopathologically in all of the patients included in the study. The metastatic tumor was located on the right and left sides of the body in seven and three patients, respectively. In one patient, the metastatic lesion was on the free edge of the tongue that was accepted as a midline disease.

Figure 1.

Tender and hemorrhagic mass on the right side of the tongue due to colon adenocarcinoma metastasis

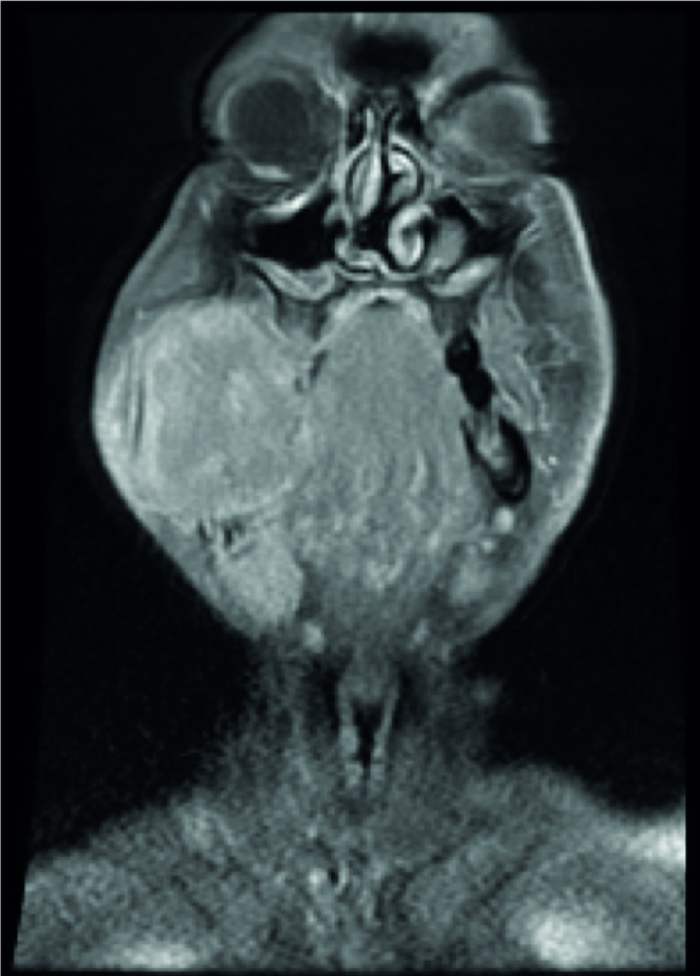

Figure 2.

T2-weighted coronal section MRI scans of a solid metastatic mass on the right parotid gland due to a lung adenocarcinoma

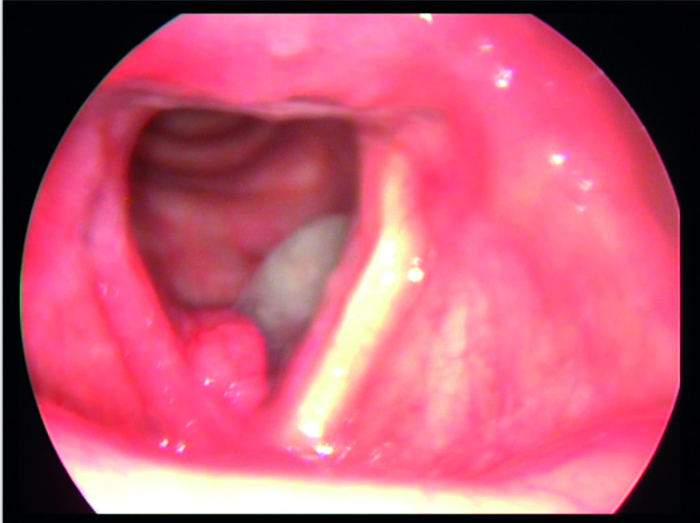

Figure 3.

Figure shows the laryngoscopic examination (via a 90° rigid endoscope) of the right subglottic mass

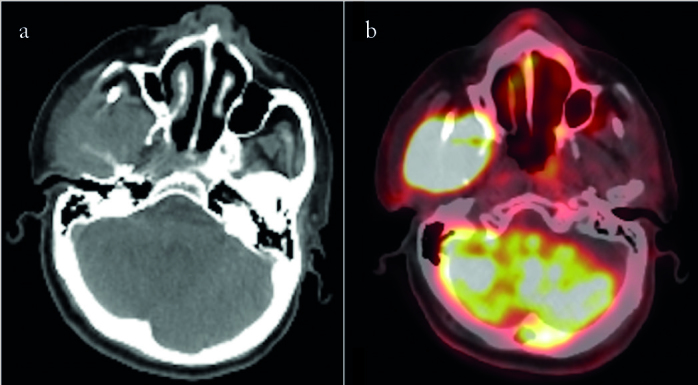

Figure 4.

a, b. The axial CT section (a) and PET/CT scan (b) of a mass invading the right buccal mucosa and right maxillary sinus

Metastatic diseases of four patients underwent surgical excision. These patients had no other distant metastasis, their primary diseases were under control, and head and neck metastases were surgically resectable. Two patients had adjuvant radiotherapy, and the other two cases had adjuvant chemotherapy. One patient with solitary subglottic larynx metastasis was treated with radiotherapy due to advanced age and medical inoperability. Two patients in the surgery group died due to systemic disease, and the other two are still alive and free of disease at 18 and 20 months of follow-up. Patients who were not convenient for surgical excision were treated with radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy depending on the prognosis of the primary disease and the degree of systemic metastatic disease. Four inoperable patients were treated with primary radiotherapy, and three patients with disseminated systemic disease were treated with palliative chemotherapy. Their prognoses were worse than the operated group.

Discussion

Metastatic malignancies from distant organs and tissues to the head and neck region are rarely seen. Only 1% of all oral and maxillofacial region malignancies are metastases of tumors that are primarily located from an infraclavicular area (5–7). However, this percentage may show variations. Shen et al. (2) reported this incidence as 0.21% (19/9239), which is much lower than the literature, and Stypulkowska et al. (8) reported a very high incidence of 3.2% in 1979. In the current study, we found the frequency of distant metastasis to the head and neck as 0.8% (11/1239) similar to the literature.

Although the main route of distant metastases to the head and neck is still not yet clear, metastases using hematogenous pathways are more common than those using lymphatic pathways (2, 5, 9). When only hematogenous metastases are taken into account, the most common way is the portal venous system. However, if this was the principal way of the entire metastases, the incidence of accompanying lung metastases would be higher. Furthermore, it was reported that metastases of the primary tumors originating from the lower parts of the body can be seen independent from the lung metastases (10). In order to clarify this situation, the valveless vertebral venous plexus (Batson’s plexus) is thought to be an alternative pathway. By using this route, tumor can metastasize to the head and neck without metastasizing to the lungs (5, 11, 12). In the present study, lung metastasis was present simultaneously in only one out of 11 patients with tumors that metastasized to the head and neck when primary lung carcinomas were excluded. Therefore, we can speculate that distant metastasis to the head and neck occurred via Batson’s plexus in the majority of our patients.

Almost all types of malignant neoplasms may metastasize to the head and neck. Histopathological subtype and frequency of metastatic tumors may show different variations according to geographic distribution and usually associate with the prevalence of malignant tumors in the host country. In the Western literature, it is reported that the most common primary tumor is lung in men and breast in women (2, 12, 13). On the other hand, in the Eastern literature, while the most common primary tumor is lung in men similar to the Western literature, breast is not the most common primary localization in women (2). In our study, we determined that the most common tumor location is the genitourinary system prostate (n=2) and kidney (n=1)) and lung in men and breast (n=2) and ovary (n=2) in women. When all of the cancer types are evaluated separately in men, an equal incidence for the localization of all three tumors is noteworthy. These findings can be explained by the lower number of patients when compared with other studies in the literature.

Symptomatology and clinical findings of metastatic neoplasms are similar to those of primary malignancies. Depending on the region where the metastases occurred, symptoms may show variations (3). It is stated in the literature that the most common symptom is asymptomatic swelling (14, 15). Most of the metastatic deposits on the head and neck can be recognized easily by physical examination. On the other hand, metastases to deeper localizations, such as the nasopharynx and larynx, can only be detected via endoscopic examination after clinical suspicion (3). In the present study, the first symptom observed in most of our patients is painless swelling that developed recently. A mass/swelling that newly developed can be determined easily by the patient, which facilitates early diagnosis. In two patients with tongue metastasis, the lesions started as painless swellings but growing rapidly into painful, ulcerated masses. One patient in our series had hoarseness that prompted us to perform a laryngoscopic evaluation with a diagnosis of subglottic tumor. Interestingly, in this patient, there was no history of any malignancy, and there was no uptake in the PET/CT scan except the larynx.

The most important factors in diagnosing a metastasis to the head and neck are clinical suspicion and complete physical examination. Most of the lesions can be visualized simply via inspection or by endoscopic evaluation. In addition, palpation of the neck, salivary glands, tongue, and base of the tongue must be performed to avoid overlooking any submucosal lesions (1). In the head and neck region, only imaging modalities can determine lesions that are not easily visualized or palpated. PET/CT scan is a valuable imaging method for systemic metastasis. Once a high uptake is observed in the PET/CT scan, further imaging modalities must be done. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with contrast is the preferred modality for soft tissue metastases including the salivary glands, orbits, nasopharynx, and larynx, and so on. For patients in whom MRI cannot be used, CT should be performed. Once the lesion is visualized, and if there is a suspicion, biopsy should be performed (16). Fine needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB), tru-cut, and incisional biopsy with frozen section can be applied depending on the region of the lesion. Simultaneously, locoregional recurrence of the primary tumor must be controlled.

Generally, metastases to the head and neck are correlated with advanced systemic disease and that indicate a worse prognosis (3, 17, 18). If the total body scanning shows that there is a systemic disease, the overall prognosis is poor, and treatment is mostly palliative (19, 20). On the other hand, solitary metastasis to the head and neck may show better prognosis (20). In these conditions, surgery and radiotherapy are the primary treatment modalities and can increase the prognosis significantly, but still, the overall prognosis is not favorable (21, 22). In the present study, the patients’ prognosis was detected as better in the surgery and/or radiotherapy group compared with the palliative chemotherapy group. Therefore, maximum treatment should be given to patients with good general condition and suitable for surgery and/or radiotherapy.

The major limitations of our study are its retrospective nature, lack of control group for both surgery and radiotherapy, and a small number of patients.

Conclusion

Primary tumors arising from any kind of tissue may metastasize in different frequencies to the head and neck. Although metastases to the head and neck are uncommon, it is crucial to remember while approaching a patient with a lesion at the head and neck location especially if there is a history of lung, breast, and genitourinary cancers. Patients should be evaluated thoroughly, and the treatment modality should be determined in multidisciplinary tumor boards. Despite the poor prognosis, reducing the tumor burden might increase the treatment success.

Footnotes

This study was presented at the 14th Turkish Rinology Congress, 6th National Neurootology Congress, 2nd Head and Neck Congress, April 28 – May 1 2018, Antalya, Turkey

Ethics Committee Approval: Ethics committee approval was received for this study from the Ethics Committee of İstanbul University School of Medicine (No. 2018/363).

Informed Consent: Informed consent was not received due to the retrospective nature of the study.

Peer-review: Externally peer-reviewed.

Author Contributions: Concept - B.Ş., C.D., M.Ç., E.Ö., S.G., Ö.E.K.; Design - B.Ş., C.D., M.Ç., E.Ö., S.G., Ö.E.K.; Supervision -B.Ş., C.D., M.Ç., E.Ö., S.G., Ö.E.K.; Resource - E.K., E.Ö., S.G.;Data Collection and/or Processing - C.D., B.Ş.; Analysis and/or Interpretation - E.Ö., M.Ç.; Literature Search - C.D., B.Ş., E.Ö.; Writing-B.Ş., C.D., M.Ç., E.Ö., S.G., Ö.E.K.; Critical Reviews - B.Ş., C.D., M.Ç., E.Ö., S.G., Ö.E.K.

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Financial Disclosure: The authors declared that this study has received no financial support.

References

- 1.Aldridge T, Kusanale A, Colbert S, Brennan PA. Supraclavicularmetastases from distant primaries: What is the role of the headand neck surgeon? Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2013;51:288–93. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2012.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shen ML, Kang J, Wen YL, Ying WM, Yi J, Hua CG, et al. Met-astatic tumors to the oral and maxillofacial region: A retrospec-tive study of 19 cases in West China and review of the Chinese and English literature. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009;67:718–37. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2008.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barnes L. Metastases to the head and neck: An overview. Head Neck Pathol. 2009;3:217–24. doi: 10.1007/s12105-009-0123-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sagheb K, Manz A, Albrich SB, Taylor KJ, Hess G, Walter C. Supraclavicular metastases from distant primary solid tumours: A retrospective study of 41 years. J Maxillofac Oral Surg. 2017;16:152–7. doi: 10.1007/s12663-016-0910-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meyer I, Shklar G. Malignant tumors metastatic to mouth and jaws. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1965;20:350–62. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(65)90167-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van der Waal RI, Buter J, van der Waal I. Oral metastases: Report of 24 cases. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;41:3–6. doi: 10.1016/S0266-4356(02)00301-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fukuda M, Miyata M, Okabe K, Sakashita H. A case series of 9 tumors metastatic to the oral and maxillofacial region. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2002;60:942–4. doi: 10.1053/joms.2002.33868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stypulkowska J, Bartkowski S, Pana’s M, Zaleska M. Metastatic tumors to the jaws and oral cavity. J Oral Surg. 1979;37:805–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sanchez Aniceto G, Garcia Penin A, de la Mata Pages R, Montal-vo Moreno JJ. Tumors metastatic to the mandible: Analysis of nine cases and review of the literature. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1990;48:246–51. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(90)90388-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Okada H, Kamino Y, Shimo M, Kitamura E, Katoh T, Nishimura H, et al. Metastatic hepatocellular carcinoma of the maxillary si-nus: A rare autopsy case without lung metastasis and a review. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;32:97–100. doi: 10.1054/ijom.2002.0242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Simo R, Sykes AJ, Hargreaves SP, Axon PR, Birzgalis AR, Slevin NJ, et al. Metastatic renal cell carcinoma to the nose and paranasal sinuses. Head Neck. 2000;22:722–7. doi: 10.1002/1097-0347(200010)22:7<722::aid-hed13>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hirshberg A, Leibovich P, Buchner A. Metastases to the oral mu-cosa: Analysis of 157 cases. J Oral Pathol Med. 1993;22:385–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1993.tb00128.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zachariades N. Neoplasms metastatic to the mouth, jaws and surrounding tissues. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 1989;17:283–90. doi: 10.1016/S1010-5182(89)80098-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baum SH, Mohr C. Metastases from distant primary tumours on the head and neck: clinical manifestation and diagnostics of 91 cases. Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2018;22:119–28. doi: 10.1007/s10006-018-0677-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Friedrich RE, Abadi M. Distant metastases and malignant cellular neoplasms encountered in the oral and maxillofacial region: Anal-ysis of 92 patients treated at a single institution. Anticancer Res. 2010;30:1843–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hirshberg A, Shnaiderman Shapiro A, Kaplan I, Berger R. Meta-static tumours to the oral cavity pathogenesis and analysis of 673 cases. Oral Oncol. 2008;44:743–52. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2007.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gupta K, Miller JD, Li JZ, Russell MW, Charbonneau C. Epide-miologic and socioeconomic burden of metastatic renal cell carci-noma (mRCC): A literature review. Cancer Treat Rev. 2008;34:193–205. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2007.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Spreafico R, Nicoletti G, Ferrario F, Scanziani R, Grasso M. Pa-rotid metastasis from renal cell carcinoma: A case report and re-view of the literature. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2008;28:266–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jatti D, Puri G, Aravinda K, Dheer DS. An atypical metastasis of renal clear cell carcinoma to the upper lip: a case report. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2015;73:371–6. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2014.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gottlieb MD, Roland JT., Jr Paradoxical spread of renal cell car-cinoma to the head and neck. Laryngoscope. 1998;108:1301–5. doi: 10.1097/00005537-199809000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dineen MK, Pastore RD, Emrich LJ, Huben RP. Results of surgical treatment of renal cell carcinoma with solitary metastasis. J Urol. 1988;140:277–9. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(17)41582-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Franzen AM, Günzel T, Lieder A. Parotid gland metastases of distant primary tumours: A diagnostic challenge. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2016;43:187–91. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2015.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]