Abstract

Objectives

We tested the hypothesis that stroke outcomes in patients with preadmission use of benzodiazepine are worse.

Method

In a prospective cohort study, we recruited patients with acute ischaemic stroke. Mortality, functional outcomes and cognition were evaluated at 8 and 90 days after stroke.

Results

370 patients were included. 62 (18.5%) of the 336 remaining patients were treated with benzodiazepines when stroke occurred, and they did not receive any other psychotropic drug. The mortality rate was higher in benzodiazepines users than non-users at day 8 (2.2% vs 8.1%, p=0.034) and day 90 (8.1% vs 25.9%, p=0.0001). After controlling for baseline differences using propensity-score matching, only the difference in mortality rate at day 90 was of borderline of significance, with a matched OR of 3.93 (95% CI, 0.91 to 16.98). In propensity-score-adjusted cohort, this difference remained significant with a similar treatment effect size (adjusted OR, 3.50; 95% CI, 1.57 to 7.76). A higher rate of poor functional outcome at day 8 and day 90 defined bymodified Rankin scale (mRS) ≥2 or by theBarthel index (BI) <95 was found in benzodiazepines users. In propensity-score-adjusted cohort, only the difference in mRS≥2 at day 90 remained significant (adjusted OR, 1.89; 95% CI, 1.02 to 3.48). In survivors at day 8 and at day 90, there was no significant difference in cognitive evaluation.

Conclusion

Our study has shown that preadmission use of benzodiazepines could be associated with increased post-stroke mortality at 90 days. These findings do not support a putative neuroprotective effect of γ-aminobutyric acidA receptors agonists and should alert clinicians of their potential risks.

Trial registration number

Keywords: stroke, mortality, benzodiazepines

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This cohort study has a great potential with regards to public health in the field of stroke outcomes, as benzodiazepines are one of the most prescribed drugs in the world.

These results are consistent with those from the literature of a non-neuroprotective effect of benzodiazepines.

These results might be confounded by indication bias (between benzodiazepines users and non-users) but the use of a propensity score matching/adjustment partially addresses this concern.

There is a lack of consistency of results for mortality and functional outcomes of stroke, suggesting new experimental approaches, to provide and appropriate mechanistic explanation.

Our results should be interpreted as hypothesis generating (without possibility of concluding that there is a causal effect) and should be replicated in further studies.

Introduction

Stroke is the second most common cause of death and the third most common cause of disability-adjusted life-years worldwide.1 Considering the long-term neurological disabilities that may result from acute stroke, and differences in the extent of recovery among stroke survivors, predicting the outcomes of stroke is a very important issue.1 A wide variety of factors influence stroke prognosis, including age, stroke severity, comorbid conditions and clinical findings.2 Knowledge of others factors such as pharmacologic and use of drugs that could influence the severity and short-term outcomes of stroke prognosis is necessary for clinicians. For example, benzodiazepines have been first considered as a type of neuroprotective agent in reducing infarct size and improving functional outcome in animal models of cerebral ischaemia.3 4 However, in humans, a recent review does not provide the evidence to support the use of benzodiazepines (γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptor agonists) for the treatment of patients with acute ischaemic stroke.5 Benzodiazepines and ethanol share several central effects, especially on activation of inhibitory GABAA receptors in the brain. We have recently shown that excessive chronic ethanol consumption is associated with higher stroke severity.6 Interestingly, the impact of preadmission use of benzodiazepine in stroke had never been evaluated as stroke is emerging as a leading cause of preventable death and disability worldwide. Benzodiazepines, because of their good efficacy and rapidity of action, are also one of the most prescribed drugs in the world, widely used for anxiety and insomnia. So, the objective of our study was to investigate the effect of preadmission use of benzodiazepine usage on stroke outcome, to clarify their role as stroke prognostic factors.

Methods

Patient and public involvement statement

Patients with ischaemic stroke admitted to our university hospital’s stroke unit (Lille, France) within 48 hours of symptom onset were recruited in the prospective ‘Biostroke’ cohort (Clinical Biological and Pharmacological Factors Influencing Stroke Outcome). The aim of the study was to understand the mechanisms of preventive neuroprotection by establishing link between biomarkers and preventive and neuroprotective measures.6 Use of benzodiazepine was one of the interests. Patients were managed according to local rules without any investigation or treatment specifically performed.

Data collection and clinical outcomes definition

All patients underwent an initial standardised evaluation, including their medical history) and vascular risk factors (using a structured questionnaire), a physical examination, a routine blood biochemistry screen and diagnostic testing. At admission patients underwent either CT or MRI scan.

Patients had a follow-up examination 8 and 90 days after admission. The modified Rankin scale (mRS), the Barthel index (BI), the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE), and all-cause mortality were recorded. Definitions used for variables included in the analysis have been previously defined.2 A National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score ≥6 was considered as a severe clinical impairment. A mRS score ≥2 (poor functional outcome), a BI score <95 (poor functional outcome) and a MMSE score <24 (cognitive impairment) were considered as the worst possible stroke outcomes.2 We also analysed the association between benzodiazepine use and respiratory failure and pneumonia at the acute phase of stroke.

Preadmission use of GABA receptors agonists

Drug exposition was defined by benzodiazepine drugs administered orally for more than 15 days before stroke regardless of length of treatment period and dosage of treatment. Hypnotic drugs were also included since they act on similar receptors to the benzodiazepines. Patients with concomitant use of other psychoactive drugs were excluded, because of their possible confounding effects.

Statistical analysis

Quantitative variables are expressed as mean (SD) in case of normal distribution or median (IQR) otherwise. Categorical variables are expressed as numbers (percentage). Normality of distributions were assessed using histograms and Shapiro-Wilk test. Bivariate comparisons between benzodiazepine users and non-users were performed using Student’s t test for quantitative variables (Mann-Whitney U test was used for non-Gaussian distribution) and Χ2 test (Fisher’s exact test was used when the expected cell frequency was <5) for categorical variables.

We assessed the effect of the benzodiazepine use on clinical outcomes at 8 and 90 days (all-cause mortality, NIHSS ≥6, mRS ≥2, BI <95 and MMSE <24) using logistic regression models and calculated the OR associated with benzodiazepine use as the treatment effect size. In order to reduce the effects of potential confounding factors in the between-group comparisons, we used propensity score methods.7 As the main analysis, propensity score was used to assemble well-balanced groups (propensity-score-matched cohort) and generalised estimating equations (GEE) models were used to take into account the matched design. As a secondary analysis, the propensity score was used as a covariate in logistic regression models to adjust the comparisons (propensity-score-adjusted cohort).

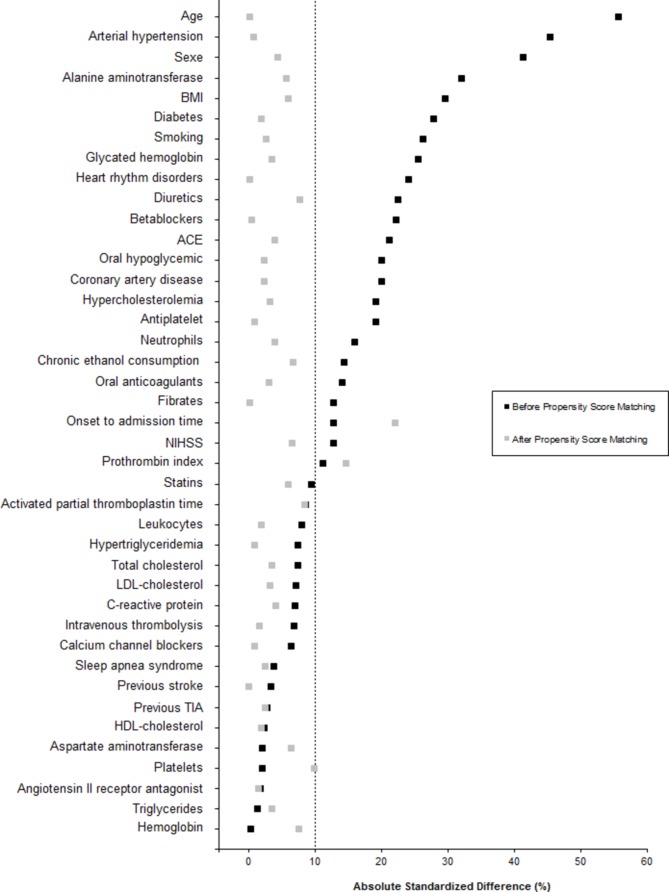

The propensity score was estimated using a non-parsimonious multivariate logistic regression model, with the benzodiazepine treatment group as the dependent variable and all of the characteristics listed in table 1 as covariates. Benzodiazepine users were matched 1:1 to patients in the non-benzodiazepine users according to propensity score using the greedy nearest neighbour matching algorithm with a calliper width of 0.2 SD of logit for propensity score.8 9 To evaluate bias reduction using the propensity score matching method, absolute standardised differences were calculated before and after propensity-score matching; an absolute standardised difference >10% indicated a meaningful imbalance in the baseline covariate.10

Table 1.

Comparison of baseline characteristics between benzodiazepine users and non-users

| Benzodiazepine non-users (n=274) |

Benzodiazepine users (n=62) |

P value (ASD, %) | |

| Demographic characteristics | |||

| Age (years), mean±SD | 65.4±15.0 | 73.1±12.6 | 0.0002 (55.7) |

| Men | 157 (57.3) | 23 (37.1) | 0.004 (41.3) |

| Medical history | |||

| Previous stroke | 28 (10.3) | 7 (11.3) | 0.81 (3.3) |

| Previous TIA | 20 (7.3) | 5 (8.1) | 0.79 (2.9) |

| Coronary artery disease | 52 (19.0) | 17 (27.4) | 0.14 (20.1) |

| Sleep apnoea syndrome | 7 (2.6) | 2 (3.2) | 0.68 (3.8) |

| Heart rhythm disorders | 59 (21.6) | 20 (32.3) | 0.075 (24.2) |

| Vascular risk factors | |||

| Arterial hypertension | 155 (56.6) | 48 (77.4) | 0.002 (45.5) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 59 (21.5) | 7 (11.3) | 0.067 (27.9) |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 124 (45.3) | 34 (54.8) | 0.17 (19.3) |

| Hypertriglyceridemia | 41 (15.0) | 11 (17.7) | 0.58 (7.5) |

| Smoking | 89 (32.5) | 13 (21.0) | 0.075 (26.2) |

| Chronic ethanol consumption | 45 (16.5) | 7 (11.5) | 0.33 (14.5) |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean±SD | 27.0±4.9 | 25.6±4.8 | 0.042 (29.6) |

| Routine drugs | |||

| Fibrates | 17 (6.2) | 6 (9.7) | 0.40 (12.9) |

| Statins | 85 (31.0) | 22 (35.5) | 0.50 (9.5) |

| Oral anticoagulants | 17 (6.2) | 2 (3.2) | 0.54 (14.1) |

| Antiplatelet | 98 (35.8) | 28 (45.2) | 0.17 (19.2) |

| ACE | 47 (17.1) | 16 (25.8) | 0.12 (21.2) |

| Angiotensin II receptor antagonist | 46 (16.8) | 10 (16.1) | 0.90 (1.8) |

| Diuretics | 65 (23.7) | 21 (33.9) | 0.098 (22.6) |

| Calcium channel blockers | 42 (15.3) | 11 (17.7) | 0.64 (6.5) |

| Betablockers | 98 (35.9) | 29 (46.8) | 0.11 (22.2) |

| Oral hypoglycemic | 45 (16.4) | 6 (9.7) | 0.18 (20.1) |

| Intravenous thrombolysis | 78 (28.9) | 16 (25.8) | 0.63 (6.9) |

| Onset to admission time (hours), median (IQR) | 2 (1 to 7) | 2 (1 to 4) | 0.36 (12.8) |

| NIHSS, median (IQR) | 6 (2–13) | 7 (2–18) | 0.42 (12.8) |

| Biological characteristics | |||

| Triglycerides (g/L), median (IQR) | 1.06 (0.81–1.56) | 1.01 (0.84–1.56) | 0.93 (1.3) |

| Total cholesterol (g/L), mean±SD | 1.96±0.49 | 1.92±0.52 | 0.60 (7.4) |

| HDL cholesterol (g/L), mean±SD | 0.53±0.17 | 0.54±0.13 | 0.86 (2.4) |

| LDL cholesterol (g/L), mean±SD | 1.17±0.41 | 1.14±0.44 | 0.61 (7.2) |

| Glycated haemoglobin (%), median (IQR) | 5.9 (5.6–6.5) | 5.9 (5.7–6.3) | 0.98 (0.4) |

| Haemoglobin (g/dL), median (IQR) | 13.8 (12.9–14.9) | 13.5 (12.5–14.2) | 0.077 (25.5) |

| Leucocytes (109/L), median (IQR) | 8.32 (6.75-9.87) | 8335 (6700–10680) 8.34 (6.70-10.68) |

0.55 (8.0) |

| Neutrophils (10 9/L), median (IQR) | 5.40 (4.20-7.40) | 5.85 (4.50-8.15) | 0.26 (16.0) |

| Platelets (10 9/L), median (IQR) | 235 (197–271) | 234.5 (192–274) | 0.88 (2.1) |

| Prothrombin index (%), median (IQR) | 96 (88–100) | 94 (86–100) | 0.42 (11.3) |

| Activated partial thromboplastin time (s), median (IQR) | 32 (29–35) | 32 (28–37) | 0.52 (8.6) |

| C-reactive protein (mg/L), median (IQR) | 4.7 (2.0–9.7) | 5.5 (2.5–9.7) | 0.65 (7.1) |

| Aspartate aminotransferase (U/L), median (IQR) | 23 (19–29) | 23 (20–27) | 0.88 (2.2) |

| Alanine aminotransferase (U/L), median (IQR) | 21 (15–29) | 18 (14–23) | 0.029 (32.2) |

Data are expressed as number (%) unless otherwise indicated.

ASD, absolute standardised difference; BMI, body mass index; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; NIHSS, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; TIA, transient ischaemic attack.

Because of missing baseline data (see online supplemental table 1), the propensity score could not be computed in 54.5% (n=183) of the study sample (61.3% in benzodiazepine users and 52.9% in non-benzodiazepine users). We therefore estimated the treatment effect size in propensity-score-matched and -adjusted cohorts after handling missing covariate values by multiple imputation11 using a regression switching approach (chained equations with m=20 imputations obtained using the R statistical software V.3.03).12 Imputation procedure was performed under the missing at random assumption using all variables listed in table 1 (ie, baseline characteristics and treatment group) with a predictive mean matching method for continuous variables and logistic regression model for categorical (all binary) variables. In each imputed data set, we calculated the propensity score and assembled a matched cohort to provide both adjusted and matched ORs. We therefore combined the ORs from each imputed data set using Rubin’s rules.13

bmjopen-2018-022720supp001.pdf (220.1KB, pdf)

Since, among alive patients, the rate of missing data was high for 8- and 90-day MMSE (27% and 24%, respectively), we also used multiple imputation approach to handle these missing values as a sensitivity analysis. Statistical testing was done at the two-tailed α level of 0.05. Data were analysed using SAS software (V.9.3, SAS Institute).

Results

Among the 370 patients included in the Biostroke study, 34 patients (mean age, 69.0±13.7; 14 men) were excluded because of concomitant use of other psychoactive drugs. In the 336 remaining patients, 62 (18.5%) were under benzodiazepines when stroke occurred.

Benzodiazepine and baseline characteristics

The baseline characteristics of the study population according to benzodiazepine treatment are described in table 1. Before matching, several meaningful differences (absolute standardised difference >10%) were found. In particular, benzodiazepine users were older (73.1±12.6 vs 65.4±15.0, p=0.0002), more likely to be women (62.9 vs 42.7%, p=0.004) and to have arterial hypertension (77.4% vs 56.6%, p=0.002), lower body mass index (25.6±4.8 vs 27.0±4.9, p=0.042) and lower levels of alanine aminotransferase (18 (14–23) vs 21 (15–29), p=0.029) than benzodiazepine users. These differences were reduced after propensity score-matching (figure 1 and online supplemental table 2) with an absolute standardised difference >10% only for onset to admission time (22.0%), and prothrombin index (14.8%) suggesting that the two study groups were well balanced after matching.

Figure 1.

Absolute standardised differences between benzodiazepine users and non-users before and after propensity score matching. BMI, body mass index; NIHSS, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; TIA, transient ischaemic attack.

Benzodiazepine and outcomes

Of the 336 study patients, 20 patients were lost to follow-up between day 8 and day 90 (see online supplemental table 3 for their main characteristics). Death occurred in 11 patients (3.3%) at day 8 and 36 (11.4%) at day 90 (see online supplemental table 4 for main individual characteristics of mortality cases). Of the surviving patients, 57.9% of them taking benzodiazepines at admission continued to take them after stroke at day 8 and 46.5% at day 90.

In unadjusted analysis, the mortality rate was higher in benzodiazepines users than non-users at day 8 (2.2% vs 8.1%, p=0.034) and day 90 (8.1% vs 25.9%, p=0.0001). However, after controlling for baseline differences using propensity-score matching, only the difference in mortality rate at day 90 was of borderline of significance, with a matched OR of 3.93 (95% CI, 0.91 to 16.98; table 2). In propensity-score-adjusted cohort, this difference remained significant with a similar treatment effect size (adjusted OR, 3.50; 95% CI, 1.57 to 7.76; table 3).

Table 2.

Outcomes at day 8 and day 90 after stroke according to prior benzodiazepine use in propensity-score-matched cohort

| Benzodiazepine users | Propensity-score-matched* | |||

| No (n=56) | Yes (n=56)† | OR (95% CI) | P value | |

| Outcome at day 8 | ||||

| All-cause death | 2/56 (4.3) | 4/56 (6.8) | 1.81 (0.23 to 13.90) | 0.56 |

| NIHSS ≥6 | 19/51 (37.3) | 20/51 (39.4) | 1.10 (0.46 to 2.60) | 0.83 |

| Poor outcome (mRS ≥2) | 33/54 (60.3) | 34/54 (63.2) | 1.13 (0.48 to 2.66) | 0.78 |

| Poor outcome (Barthel <95) | 29/52 (55.3) | 32/52 (61.2) | 1.28 (0.51 to 3.15) | 0.59 |

| Cognitive impairment (MMSE <24) | 13/37 (34.4) | 10/35 (28.0) | 0.75 (0.24 to 2.34) | 0.62 |

| Outcome at day 90 | ||||

| All-cause death | 4/53 (7.6) | 12/52 (23.5) | 3.93 (0.91 to 16.98) | 0.067 |

| Poor outcome (mRS ≥2) | 25/53 (46.4) | 31/52 (59.7) | 1.72 (0.75 to 3.91) | 0.19 |

| Poor outcome (Barthel <95) | 18/49 (36.0) | 16/40 (39.6) | 1.18 (0.47 to 2.94) | 0.72 |

| Cognitive impairment (MMSE <24) | 6/37 (14.9) | 5/33 (15.0) | 1.04 (0.23 to 4.51) | 0.96 |

Values are n/N (%) unless otherwise indicated, calculated after handling missing baseline data including in propensity-score calculation by multiple imputation procedure (m=20 imputed data sets; n were estimated using the combined rates and the mean number of patients without missing outcome values).

*Calculated using a generalised estimating equations (GEE) model (binomial distribution, logit function) take into account the propensity-score matched design.

†Mean numbers of matched pairs among the 20-imputed datasets.

MMSE, Mini Mental State Examination; mRS, modified Rankin score; NIHSS, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale.

Table 3.

Outcomes at day 8 and day 90 after stroke according to prior benzodiazepine use In propensity-score-adjusted cohorts

| Benzodiazepine users | P value | Propensity-score –adjusted* | P value | ||

| No | Yes | OR (95% CI) | |||

| Outcome at day 8 | (n=274) | (n=62) | |||

| All-cause death | 6/274 (2.2) | 5/62 (8.1) | 0.034 | 2.53 (0.68 to 9.27) | 0.16 |

| NIHSS ≥6 | 86/264 (32.58) | 22/55 (40) | 0.29 | 1.46 (0.77 to 2.75) | 0.24 |

| Poor outcome (mRS ≥2) | 137/270 (50.7) | 39/60 (65.0) | 0.045 | 1.56 (0.84 to 2.88) | 0.15 |

| Poor outcome (Barthel <95) | 119/265 (44.9) | 35/56 (62.5) | 0.017 | 1.68 (0.90 to 3.14) | 0.10 |

| Cognitive impairment (MMSE <24) | 52/196 (26.5) | 11/40 (27.5) | 0.90 | 0.72 (0.31 to 1.62) | 0.42 |

| Outcome at day 90 day | (n=258) | (n=58) | |||

| All-cause death | 21/258 (8.1) | 15/58 (25.9) | 0.0001 | 3.50 (1.57 to 7.76) | 0.002 |

| Poor outcome (mRS ≥2) | 110/258 (42.6) | 35/58 (60.3) | 0.014 | 1.89 (1.02 to 3.48) | 0.042 |

| Poor outcome (Barthel <95) | 72/235 (30.6) | 16/43 (37.2) | 0.39 | 1.31 (0.64 to 2.65) | 0.45 |

| Cognitive impairment (MMSE <24) | 26/194 (13.4) | 5/35 (14.3) | 0.79 | 0.87 (0.29 to 2.55) | 0.80 |

Values are n/N (%) unless otherwise indicated.

* Logistic regression models adjusted on propensity score.

MMSE, Mini Mental State Examination; mRS, modified Rankin score; NIHSS, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale.

In unadjusted analysis, a higher rate of poor functional outcome at day 8 defined by mRS≥2 or by the Barthel index (BI) <95 was found in benzodiazepines users (table 3). A similar between-group difference was found for mRS≥2 at day 90. However, none of the differences were found in propensity-score matched (table 2). In propensity-score-adjusted cohort, only the difference in mRS≥2 at 90 day remained significant (adjusted OR, 1.89; 95% CI, 1.02 to 3.48).

In survivors at day 8 or at day 90, there was no significant difference in MMSE, in unadjusted, propensity-score-matched and -adjusted analyses. When the analyses were repeated after handling the missing data on MMSE by using multiple imputation approach (see online supplemental table 5 for main baseline characteristics in patients with and without missing values), similar non-significant differences were found. In propensity-score-matched cohort, the OR (95% CI) were 0.82 (0.30 to 2.19) for day 8 MMSE <24 and 1.04 (0.23 to 4.51) for day 90 MMSE <24. In propensity-score-adjusted cohort, the OR (95% CI) were 0.89 (0.43 to 1.83) for day 8 MMSE <24 and 1.04 (0.34 to 3.16) for day 90 MMSE <24.

Regarding respiratory failure or pneumonia at day 8, benzodiazepines users have a similar early respiratory complications risk than non-users (13.8% (n=8) vs 15.6% (n=48), unadjusted p=0.73).

Discussion

Preadmission use of benzodiazepines could not be considered as neuroprotective, as users of benzodiazepines could have a higher risk of death at 90 days after stroke.

Mortality and benzodiazepines

A recent review does not provide the evidence to support the use of GABA receptor agonists for the treatment of patients with acute ischaemic stroke.5Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) investigating GABA receptor agonists versus placebo for patients with acute stroke with the outcomes of death or dependency and functional independence were included. These RCTs measured death and dependency at 3 months in clomethiazole versus placebo or between diazepam and placebo without significant difference. In a recent non-randomised comparison, treatment with benzodiazepines after ischaemic stroke had no independent impact on stroke outcomes and mortality at day 90.14 However, these data were registered in a trials archive and were not derived from prospective trials, with indication bias and many confounders. In our prospective study, current users of benzodiazepines could have a higher rate of post-stroke mortality at day 90. The effect of benzodiazepine drugs on mortality is still debated, but these results are consistent with those from the literature. In a large cohort of patients attending primary care, GABAA receptors agonists were associated with significantly increased risk of mortality.15 In two other representative databases, a significant while moderate increase in all-cause mortality in relation to benzodiazepines was found, in a population of incident and mostly occasional users.16 A recent population-wide register-based study identified that benzodiazepines are more frequently used in patients with strokes than in controls and are associated with greater all-cause mortality in patients with stroke and matched controls.17 The use of anti-anxiety medication and mortality risk in patients following myocardial infarction has also been studied in a sampling database.18 Sudden death was significantly associated with increased benzodiazepam dosage during approximately 5 years. For patients receiving higher doses of daily benzodiazepines, protective effects for cardiac mortality and heart failure hospitalisation decreased and a J-curve dose–response relationship was seen, without providing an adequate mechanistic explanation. Benzodiazepines have been shown to increase the occurrence of community-acquired pneumonia,19 due to their pharmacodynamic properties. In our cohort, prior use of benzodiazepines didn’t increase the incidence of respiratory depression and cannot explain mortality in these patients.

Cognition and benzodiazepines

Benzodiazepine use was neither associated with cognitive impairment at day 8 or day 90. However, the short-term effects of benzodiazepines on impairment of cognition are well known and use of benzodiazepines is also associated with increased risk of dementia, even if the nature of the link between benzodiazepines and Alzheimer’s disease remains unclear.20 In our cohort, GABA receptor agonists treatment before stroke didn’t show cognitive impairment as assessed by MMSE, in these elderly patients without dementia, but a longer follow-up period may be useful. Further, although we use methods to impute for missing data, data are missing on follow-up—loss to follow-up in a set, and then lack of doing MMSE on follow-up in another set (post-stroke aphasia)—which are likely not missing at random.

Comorbid alcohol use disorder

Prior benzodiazepine use (regardless the dosage of treatment) was not associated with higher baseline stroke severity, as excessive chronic ethanol consumption was.6 Benzodiazepine users were also less likely to be alcohol drinkers in our study, although the difference did not reach the significance level. So, the relationship between stroke severity and alcohol consumption could not be necessarily due to a link between GABA receptors and alcohol, but due to chronic effects of ethanol consumption on other organ systems.

Strengths and limitations

Our stroke data base was prospectively collected, and the study was carried out in a representative cohort of routine clinical stroke patients with an exhaustive drug history analysis. Dosage and compliance rate were not controlled for. More data on the length of time patients had been using the drug were not available, but it is reasonable to think that they had an inadequate situation with excessive duration of prescription (demographic characteristics).21 Further research should definitely explore correlations between dosage or cumulative length of exposure and post-stroke mortality. Also, potentially multi-site studies need acknowledgement, as does the need for replication in countries where there may be different practice in the prescribing of benzodiazepines. In our study, there was no clear association between mortality and poor functional outcome. For the deaths, information about the underlying cause was not obtained, but was not associated with stroke severity. It is important to acknowledge that this study is also limited to stroke outcomes in patients admitted to hospital after stroke. Unfortunately, we don’t have information on premorbid functional status.

The present findings are derived from observational analyses, which are subject to well-known limitations. The first is the potential for confounding by measured or unmeasured variables, which cannot be ruled out, even after propensity score matching/adjustment. It’s also possible that the indication for benzodiazepines may be a causative variable, as mood (depression or anxiety) increases mortality in stroke.22 Our results should be interpreted as hypothesis generating (without possibility of concluding that there is a causal effect).

Another limitation was the presence of missing data in some covariates, including in the propensity score calculation, as well as in MMSE outcome. Although we used multiple imputations to handle missing data as appropriate, we could not exclude that missing data could introduce a bias in estimates. Since no formal study sample size was calculated, we could not exclude that some differences may have been overlooked due to the lack of adequate statistical power. In a posterior power calculation, we calculated the smallest significant between-group difference (expressed as effect size using odd ratio) that our study sample size allowed us to detect with a 80% power. Assuming an incidence of outcome of 10% and 50% in non-benzodiazepine users, we could detect an OR of 4.0 and 3.1 in the propensity-score-matched cohort and 2.8 and 2.3 in propensity-score-adjusted cohort.

Unanswered questions and implication for clinical practice

The lack of consistency of results for moderate increase in mortality and functional outcomes make this less likely to explain a physiologic effect. Anyway, the possible increased rate of mortality after stroke found in the benzodiazepines users group add to the increasing body of evidence concerning a non-neuroprotective effect of GABA receptors agonists. Benzodiazepines reduce the cerebral metabolic rate of oxygen and cerebral blood flow and can induce post-hypoxic leukoencephalopathy.23 24 As lack of blood flow leads to cerebral hypoxia, it results in a cascade of biological events, which facilitates glutamate release. Based on these data, we hypothesised that chronic cerebral hypoxia could thus be induced by benzodiazepine use, especially with inadequate situation with excessive duration of treatment. Long-term modulation of GABAA receptors by benzodiazepines could modulate ischaemia-induced glutamate release. Our findings generate a hypothesis that needs confirmation. As an interventional study would not be feasible, this question can be answered though experimental approaches in animals to provide and appropriate mechanistic explanation.

This research should also not be used to condemn GABA receptors agonist drugs since their short-term use can have an important role in the management of anxiety. This study should, however, alert clinicians to a possible increased post-stroke mortality in benzodiazepine users. As patients could also be at high risk of recurrence after stroke, use of benzodiazepines should be cautioned against.

Conclusion

Our findings do not support a putative neuroprotective effect of benzodiazepines. Further larger studies are warranted to confirm the association between benzodiazepine use and early post-stroke mortality.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

Contributors: OC wrote the manuscript and contributed to the analysis. JL performed statistical analysis and contributed to drafting the manuscript. JD contributed to drafting the manuscript. A-MM contributed to study design and data collection. VD contributed to statistical analysis and contributed to drafting the manuscript. CC contributed to study design and data collection. DD contributed to study design, data collection and analysis. DL contributed to study design, data collection and analysis. RB contributed to study design, data collection and analysis, and drafting the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This study was funded by the French Ministry of Health (as part of the PHRC programme).

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Comité de Protection des Personnes Nord-Ouest IV.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1. Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K, et al. Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2010. Lancet 2012;380:2095–128. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Deplanque D, Masse I, Lefebvre C, et al. Prior TIA, lipid-lowering drug use, and physical activity decrease ischemic stroke severity. Neurology 2006;67:1403–10. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000240057.71766.71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Marshall JW, Green AR, Ridley RM. Comparison of the neuroprotective effect of clomethiazole, AR-R15896AR and NXY-059 in a primate model of stroke using histological and behavioural measures. Brain Res 2003;972:119–26. 10.1016/S0006-8993(03)02511-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nelson RM, Green AR, Lambert DG, et al. On the regulation of ischaemia-induced glutamate efflux from rat cortex by GABA; in vitro studies with GABA, clomethiazole and pentobarbitone. Br J Pharmacol 2000;130:1124–30. 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Liu J, Wang LN. Gamma aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptor agonists for acute stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;2:CD009622 10.1002/14651858.CD009622.pub2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ducroquet A, Leys D, Al Saabi A, et al. Influence of chronic ethanol consumption on the neurological severity in patients with acute cerebral ischemia. Stroke 2013;44:2324–6. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.001355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Austin PC. An introduction to propensity score methods for reducing the effects of confounding in observational studies. Multivariate Behav Res 2011;46:399–424. 10.1080/00273171.2011.568786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Austin PC. A comparison of 12 algorithms for matching on the propensity score. Stat Med 2014;33:1057–69. 10.1002/sim.6004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Austin PC. Optimal caliper widths for propensity-score matching when estimating differences in means and differences in proportions in observational studies. Pharm Stat 2011;10:150–61. 10.1002/pst.433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Austin PC. Balance diagnostics for comparing the distribution of baseline covariates between treatment groups in propensity-score matched samples. Stat Med 2009;28:3083–107. 10.1002/sim.3697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mattei A. Estimating and using propensity score in presence of missing background data: an application to assess the impact of childbearing on wellbeing. Statistical Methods and Applications 2009;18:257–73. 10.1007/s10260-007-0086-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Buuren S, Groothuis-Oudshoorn K. mice : multivariate imputation by chained equations in R . J Stat Softw 2011;45. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rubin DB. Multiple imputation for nonresponse in surveys. New York: Wiley, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Frank B, Fulton RL, Lees KR, et al. Impact of benzodiazepines on functional outcome and occurrence of pneumonia in stroke: evidence from VISTA. Int J Stroke 2014;9:890–4. 10.1111/ijs.12148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Weich S, Pearce HL, Croft P, et al. Effect of anxiolytic and hypnotic drug prescriptions on mortality hazards: retrospective cohort study. BMJ 2014;348:g1996 10.1136/bmj.g1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Palmaro A, Dupouy J, Lapeyre-Mestre M. Benzodiazepines and risk of death: Results from two large cohort studies in France and UK. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2015;25:1566–77. 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2015.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jennum P, Baandrup L, Iversen HK, et al. Mortality and use of psychotropic medication in patients with stroke: a population-wide, register-based study. BMJ Open 2016;6:e010662 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wu CK, Huang YT, Lee JK, et al. Anti-anxiety drugs use and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with myocardial infarction: a national wide assessment. Atherosclerosis 2014;235:496–502. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2014.05.918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Obiora E, Hubbard R, Sanders RD, et al. The impact of benzodiazepines on occurrence of pneumonia and mortality from pneumonia: a nested case-control and survival analysis in a population-based cohort. Thorax 2013;68:163–70. 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2012-202374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Billioti de Gage S, Bégaud B, Bazin F, et al. Benzodiazepine use and risk of dementia: prospective population based study. BMJ 2012;345:e6231 10.1136/bmj.e6231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Airagnes G, Pelissolo A, Lavallée M, et al. Benzodiazepine misuse in the elderly: risk factors, consequences, and management. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2016;18:89 10.1007/s11920-016-0727-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. House A, Knapp P, Bamford J, et al. Mortality at 12 and 24 months after stroke may be associated with depressive symptoms at 1 month. Stroke 2001;32:696–701. 10.1161/01.STR.32.3.696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Forster A, Juge O, Morel D. Effects of midazolam on cerebral blood flow in human volunteers. Anesthesiology 1982;56:453–5. 10.1097/00000542-198206000-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bartlett E, Mikulis DJ. Chasing "chasing the dragon" with MRI: leukoencephalopathy in drug abuse. Br J Radiol 2005;78:997–1004. 10.1259/bjr/61535842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-022720supp001.pdf (220.1KB, pdf)