Abstract

Objective

Few studies with large sample populations concerning renal anaemia and IgA nephropathy have been reported worldwide. The purpose of this cross-sectional study was to examine the clinical and pathological characteristics and influencing factors associated with renal anaemia in patients with IgA nephropathy, which is the most common aetiology of chronic kidney disease.

Methods

A total of 462 hospitalised patients with IgA nephropathy confirmed by renal biopsy who met the inclusion criteria were consecutively recruited from January 2014 to January 2016. Their general information, routine blood test results, blood chemistries, estimated glomerular filtration rates (eGFRs) and renal pathologies were collected. The Oxford classification was used to characterise the renal pathologies. Univariable and multivariate logistic regression models were used to analyse the influencing factors of anaemia associated with IgA nephropathy.

Results

The incidence of renal anaemia was 28.5% (132/462 patients) in our study (21.3% in males and 38.9% in females). The anaemia type was primarily normocytic and normochromic. The rate of anaemia in patients with eGFR values of 30–59 mL/min/1.73 m2 was higher than that in patients with an eGFR >60 mL/min/1.73 m2 (42.9% vs 17.8%, p<0.001). Notably, in the group with eGFR values <15 mL/min/1.73 m2, the anaemia rate was 100%. Logistic regression analysis showed that factors affecting anaemia in patients with IgA nephropathy included being female (OR 3.02, 95% CI 1.76 to 5.17), low albumin levels (OR 0.87, 95% CI 0.82 to 0.93), reduced eGFR values (OR 0.98, 95% CI 0.97 to 0.99) and renal tubulointerstitial lesions >50% (OR 2.57, 95% CI 1.22 to 5.40).

Conclusions

The female sex, hypoalbuminaemia, reduced eGFR levels and severe renal tubulointerstitial lesions were correlated with renal anaemia in patients with IgA nephropathy. These results provide new insight into our understanding of anaemia in IgA nephropathy and may improve the management and treatment of clinical renal anaemia.

Keywords: renal anaemia, iga nephropathy, renal tubulointerstitial lesions

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first cross-sectional study on morbidity, types of anaemia classification and influence factors of renal anaemia among patients with IgA nephropathy who were diagnosed by renal biopsy with a large-scale population.

This study is a cross-sectional design with the limitation of failure to determine the causal relationship between the influencing factors and anaemia.

We only analysed those patients who underwent renal biopsy, but some of patients with IgA nephropathy did not receive renal biopsy for various reasons, so there was a selection bias in this study.

The erythropoietin data were not obtained since these are not a route examination item in daily clinical work.

Introduction

Renal anaemia is one of the most common complications of chronic kidney disease (CKD). This condition can accelerate the progression of renal function injury, induce cardiovascular events, reduce the quality of life of patients and is associated with a poor prognosis.1–4 Different types of CKD have shown different prevalences of renal anaemia with different prognoses.5–7

IgA nephropathy is currently the major aetiology of the progression of CKD into end-stage renal disease.8 Especially in Asian-Pacific regions, this condition primarily occurs in young adult men. If not well controlled, approximately 25%–45% of patients will progress to chronic renal failure within 20 years; this condition requires replacement therapies, such as blood purification and poses considerable threats to public health.9–11 Therefore, we choose IgA nephropathy as the research subject. Aruga et al 12 reported that the levels of haemoglobin (Hb), haematocrit and red blood cells of 62 patients with IgA nephropathy gradually decreased according to the progression of renal injuries, and the fibrosis and/or inflammatory cell infiltration in the tubulointerstitial region was more marked in patients with a poor prognosis.

However, there remains a lack of large-scale population studies regarding the morbidity, types of anaemia classification and influencing factors of renal anaemia among patients with IgA nephropathy. To gain a better understanding of anaemia in patients with IgA nephropathy and improve the efficacy of renal anaemia therapy, a total of 658 patients diagnosed with IgA nephropathy by kidney biopsy at the centre of kidney diseases between January 2014 and January 2016 were enrolled in this study. Ultimately, 462 patients with IgA nephropathy who met the study inclusion and exclusion criteria were included in the final analysis.

Methods

Study design and subjects

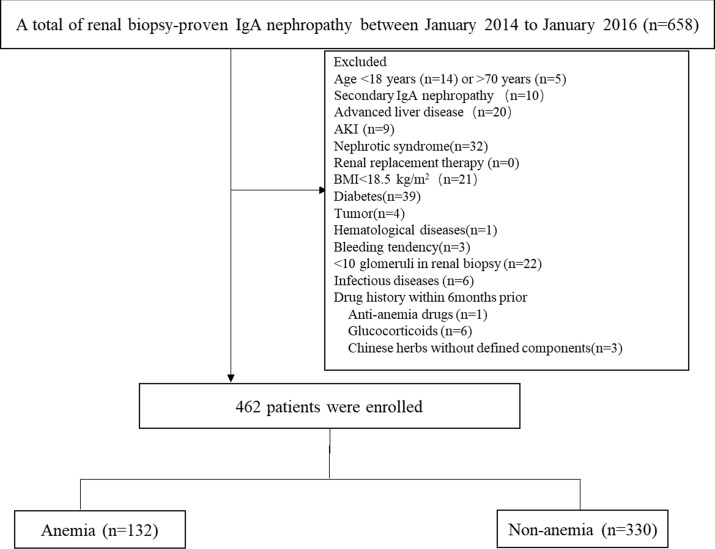

This cross-sectional study was performed at the Department of Nephrology of the Chinese PLA General Hospital. Consecutive inpatients aged 18–70 years who were diagnosed with IgA nephropathy by renal biopsy (renal biopsy criteria was shown in online supplementary tables S1 and S2) from January 2014 to January 2016 were enrolled. The exclusion criteria for enrolment were as follows: (1) secondary IgA nephropathy, such as Henoch-Schonlein purpura nephritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, hepatitis B virus (HBV)-related glomerulonephritis or diabetic nephropathy; (2) <10 glomeruli in the renal biopsy; (3) acute kidney injury, nephrotic syndrome or renal replacement therapy; (4) malnutrition, body mass index (BMI) <18.5 kg/m2; (5) acute infection, patients with liver cirrhosis, cancer, gastrointestinal bleeding, female menstrual period or systemic blood disease; (6) patients currently being treated with anaemia drugs, glucocorticoids, immunosuppressive medication or Chinese herbs without defined components within the past 6 months. Ultimately, 462 eligible patients were analysed, including 132 in the anaemic group and 330 in the non-anaemic group. All patients with renal biopsies signed the research protocol of the Renal Clinical Database Establishment when hospitalised, allowing their clinical data to be used for scientific purposes (see figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart showing the study design. AKI, acute kidney injury; BMI, body mass index.

bmjopen-2018-023479supp002.pdf (155.5KB, pdf)

Data collection

We collected physical and clinical information, including patient sex, age, BMI, blood pressure, Hb, erythrocyte mean corpuscular volume (MCV), erythrocyte mean corpuscular haemoglobin concentration (MCHC), levels of C reactive protein (CRP), serum creatinine, blood urea nitrogen, serum uric acid, serum albumin (ALB), serum prealbumin, total cholesterol (TC), triglyceride (TG) and total urinary protein (UPr) within 24 hours from 462 patients with IgA nephropathy.

Patients were classified by the CKD diagnostic criteria from the Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative guidelines of 2006. They were stratified into five stages according to estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) value: stage 1 (≥90 mL/min/1.73 m2), stage 2 (60–89 mL/min/1.73 m2), stage 3 (30–59 mL/min/1.73 m2), stage 4 (15–29 mL/min/1.73 m2) and stage 5 (<15 mL/min/1.73 m2). The eGFR was calculated using the CKD-Epidemiology Collaboration formula.13

BMI was calculated using the standard formula of weight (kg)/height (m2).

Anaemia was defined as Hb <130 g/L in males and <120 g/L in females.

If patients had an MCV of 80–100 fl and an MCHC of 320–350 g/L simultaneously, the anaemia was diagnosed as normocytic, normochromic anaemia.

Pathology of renal injury was estimated independently by X-MC and Xue-guang Zhang according to the Oxford classification of IgA nephropathy as follows14: mesangial score <0.5 (M0) or >0.5 (M1); endocapillary hypercellularity (absent (E0) or present (E1)); segmental glomerulosclerosis (absent (S0) or present (S1)); presence or absence of podocyte hypertrophy/tip lesions in biopsy specimens with S1; tubular atrophy/interstitial fibrosis <25% (T0), 26%–50% (T1) or >50% (T2) and cellular/fibrocellular crescents absent (C0), present in at least one glomerulus (C1) or in >25% of glomeruli (C2).

Statistical analyses

SPSS V.22.0 was used for all statistical analyses. The clinical and demographic data were compared between anaemic and non-anaemic subjects using the Student’s t-test or χ2 test as appropriate. Normally distributed variables were expressed as the mean±SD, whereas non-normally distributed variables were expressed as the median (minimum–maximum). Univariate logistic regression and multivariate logistic regression were used to analyse the influencing factors of anaemia in IgA nephropathy. For all analyses, p values<0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and public were not involved in the design and planning of the study.

Results

Patient characteristics

In total, 462 patients with IgA nephropathy qualified for analysis; of them, 272 were male, the mean age of all patients was 36.6±11.3 years, and the mean Hb level was 133±19 g/L. The diagnostic criteria for anaemia were met by 28.5% of the patients (132/462). The anaemia rate was 21.3% (58/272) in the male patients and 38.9% (74/190) in the female patients. The majority (125/132) of patients with IgA nephropathy had normocytic, normochromic anaemia. The clinical and demographic characteristics of patients are shown in table 1. Compared with the non-anaemic group, renal anaemia was more likely to occur in older, female patients with IgA nephropathy. The anaemic group had lower eGFR and ALB levels and higher 24 hours UPr levels than the non-anaemic group (p<0.05). Blood pressure, TC, TG and CRP levels were not significantly different between anaemic and non-anaemic patients (p>0.05). The serum prealbumin level, an indicator of nutritional status, did not show any significant difference between the anaemic and non-anaemic group (p>0.05). In addition, we analysed the data of 258 subjects with available measurements of total iron binding capacity (Tibc), Fe and transferrin saturation (TS) (the results was shown in online supplementary table S3).

Table 1.

Comparison of the characteristics of anaemic and non-anaemic patients with IgA nephropathy

| Characteristic | Anaemic n=132 |

Non-anaemic n=330 |

P value |

| Age (years) | 39.1±12.4 | 35.6±10.6 | 0.002 |

| Sex (male/female) | 58/74 | 214/116 | 0.000 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.2±3.1 | 25.0±3.5 | 0.013 |

| Blood pressure (mm Hg) | |||

| Systolic | 131.3±21.3 | 129.7±17.1 | 0.439 |

| Diastolic | 83.2±13.4 | 85.0±12.2 | 0.169 |

| Laboratory results | |||

| Hb, female (g/L) | 106.7±11.0 | 129.6±8.6 | 0.000 |

| Hb, male (g/L) | 116.0±10.2 | 149.2±11.0 | 0.000 |

| MCV (fL) | 87.3±5.4 | 87.7±3.8 | 0.353 |

| MCH (pg) | 29.5±2.3 | 30.4±1.4 | 0.000 |

| MCHC (g/L) | 337.8±12.0 | 347.0±10.4 | 0.000 |

| CRP (mg/dL) | 0.3 (0.0–2.1) | 0.3 (0.0–5.0) | 0.361 |

| Serum albumin (g/L) | 37.3±3.9 | 40.6±4.0 | 0.000 |

| BUN (mmol/L) | 6.9 (1.3–31.8) | 5.3 (2.2–19.5) | 0.000 |

| SCr (μmol/L) | 128.2 (48.3–729.3) | 91.8 (45.9–321.3) | 0.000 |

| UA (μmol/L) | 398.8±121.7 | 378.4±103.7 | 0.091 |

| TC (mmol/L) | 4.4 (2.3–7.1) | 4.5 (2.7–8.6) | 0.787 |

| TG (mmol/L) | 1.8 (0.3–6.2) | 1.9 (0.4–8.8) | 0.055 |

| Prealbumin (g/L) | 28.9 (10.5–52.2) | 28.9 (11.8–56.2) | 0.440 |

| 24 hours UPr (g/day) | 1.7 (0.1–7.9) | 1.7 (0.4–8.8) | 0.000 |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 58.8±33.4 | 28.7 (11.8–56.2) | 0.000 |

BMI, body mass index; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; CRP, C reactive protein; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; Hb, haemoglobin; MCH, mean corpuscular haemoglobin; MCHC, mean corpuscular haemoglobin concentration; MCV, mean corpuscular volume; SCr, serum creatinine; SUA, serum uric acid; TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglyceride; UA, uric acid; UPr, urinary protein.

Data are expressed as the means±SD or medians (minimum–maximum). eGFR was estimated using the CKD-epidemiology standard. Anaemia was defined as a Hb value of <130 g/L for males and <120 g/L for females.

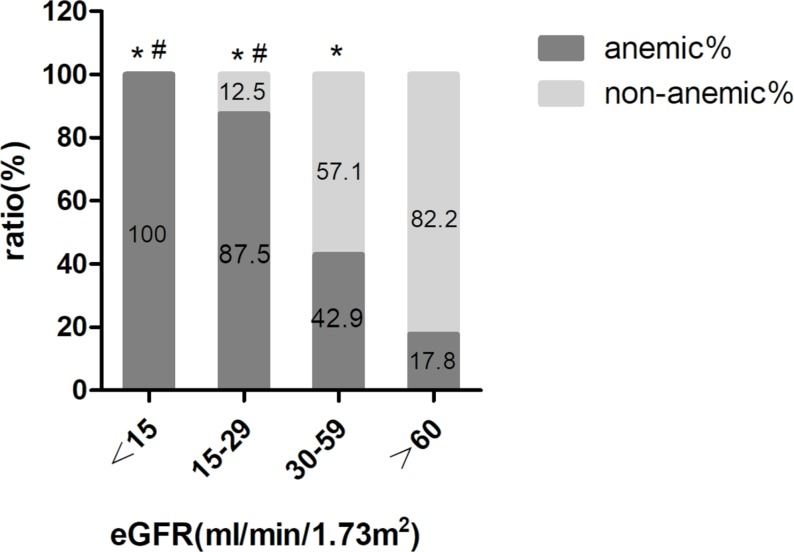

Anaemia rate in patients with various eGFR levels

As shown in figure 2, the rate of anaemia increased with a decrease in eGFR level. The ratios of anaemia in patients with an eGFR of 30–59 mL/min/1.73 m2 (42.9%, p<0.001), an eGFR of 15–29 mL/min/1.73 m2 (87.5%, p<0.001) and an eGFR <15 mL/min/1.73 m2 (100%, p<0.001) were higher than in patients with an eGFR >60 mL/min/1.73 m2 (17.8%). Compared with patients with an eGFR of 30–59 mL/min/1.73 m2, the ratios of anaemia in patients with an eGFR of 15–29 mL/min/1.73 m2 (87.5%, P<0.001) and an eGFR <15 mL/min/1.73 m2 (100%, p=0.008) were higher, and there was no significant difference between the rate of anaemia in patients with an eGFR of 15–29 mL/min/1.73 m2 and patients with an eGFR <15 mL/min/1.73 m2 (p=0.499).

Figure 2.

The rate of anaemia and non-anaemia in patients with different eGFR levels. Comparison of the rate of anaemia at different eGFR levels: *P<0.05 compared with anaemic patients with an eGFR >60 mL/min/1.73 m2; #P<0.05 compared with anaemic patients with an eGFR of 30–59 mL/min/1.73 m2. eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate.

Kidney pathological characteristics of anaemic and non-anaemic patients

Table 2 shows the kidney pathological characteristics of anaemic and non-anaemic patients. M (M0/1), E (E0/1), S (S0/1), T (T0/1/2) and C (C0/1/2) were used to characterise the IgA nephropathy pathological injury score. χ2 testing showed that the ratios of M1, T2 and C2 were higher in the anaemic group than in the non-anaemic group (anaemics vs non-anaemics: M1, 56.8% vs 38.5%, p<0.001; T2, 52.3% vs 14.8%, p<0.001; C2, 7.6% vs 2.4%, p=0.009, respectively), while the ratios of E1 and S1 were not significantly different (anaemics vs non-anaemics: E1, 11.4% vs 16.1%, p=0.198; S1, 75.8% vs 66.7%, p=0.056, respectively) between the anaemic and non-anaemic patients.

Table 2.

Renal pathological injury score comparison between anaemic and non-anaemic patients

| Renal pathology* | Score | Anaemic, n (%) | Non-anaemic, n (%) | P value |

| M | M0 | 57 (43.2) | 203 (61.5) | |

| M1 | 75 (56.8) | 127 (38.5) | 0.000 | |

| E | E0 | 117 (88.6) | 277 (83.9) | |

| E1 | 15 (11.4) | 53 (16.1) | 0.198 | |

| S | S0 | 32 (24.2) | 110 (33.3) | |

| S1 | 100 (75.8) | 220 (66.7) | 0.056 | |

| T | T0 | 35 (26.5) | 185 (56.1) | |

| T1 | 28 (21.2) | 96 (29.1) | ||

| T2 | 69 (52.3) | 49 (14.8) | 0.000 | |

| C | C0 | 72 (54.5) | 197 (59.7) | |

| C1 | 50 (37.9) | 125 (37.9) | ||

| C2 | 10 (7.6) | 8 (2.4) | 0.009 |

Variables were divided into subcategories as follows: Mesangial score <0.5 (M0) or >0.5 (M1); endocapillary hypercellularity absent (E0) or present (E1); segmental glomerulosclerosis absent (S0) or present (S1); presence or absence of podocyte hypertrophy/tip lesions in biopsy specimens with S1; tubular atrophy/interstitial fibrosis <25% (T0), 26%–50% (T1), or >50% (T2); cellular/fibrocellular crescents absent (C0), present in at least one glomerulus (C1) or present in >25% of glomeruli (C2).

*Renal injury was estimated by the Oxford classification of IgA nephropathy.

Analysis of the influencing factors associated with renal anaemia in patients with IgA nephropathy

The correlative factors for renal anaemia in patients with IgA nephropathy were determined using univariable and multivariable logistic regression as shown in table 3. Age, sex, BMI, ALB, eGFR, M, T and C were used as independent variables, and anaemia and non-anaemia were used as the dependent variable for all analyses. After the variables were screened, the major influencing factors identified included: sex (OR 3.02, 95% CI 1.76 to 5.17), albumin (OR 0.87, 95% CI 0.82 to 0.93), eGFR (OR 0.98, 95% CI 0.97 to 0.99) and T2 (OR 2.57, 95% CI 1.22 to 5.40). According to the logistic regression results, we used eGFR and Hb as well as albumin and Hb for correlation analysis. Besides, we compared the Hb concentrations of the T0, T1 and T2 groups (as shown in online supplementary figure S1).

Table 3.

Analysis of the influencing factors associated with renal anaemia in patients with IgA nephropathy (logistic regression)

| Univariable logistic | Multivariable logistic | |||

| OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | |

| Age | 1.03 (1.01 to 1.05) | 0.002 | 0.99 (0.97 to 1.02) | 0.510 |

| Sex | 2.35 (1.56 to 3.55) | 0.000 | 3.02 (1.76 to 5.17) | 0.000 |

| BMI | 0.92 (0.87 to 0.98) | 0.013 | 0.95 (0.88 to 1.03) | 0.203 |

| ALB | 0.82 (0.78 to 0.87) | 0.000 | 0.87 (0.82 to 0.93) | 0.000 |

| eGFR | 0.97 (0.96 to 0.98) | 0.000 | 0.98 (0.97 to 0.99) | 0.000 |

| Mesangial hypercellularity | ||||

| M0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| M1 | 2.10 (1.40 to 3.19) | 0.000 | 1.22 (0.72 to 2.06) | 0.468 |

| Tubular atrophy/interstitial fibrosis | ||||

| T0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| T1 | 1.54 (0.89 to 2.69) | 0.126 | 0.81 (0.42 to 1.57) | 0.541 |

| T2 | 7.44 (4.45 to 12.45) | 0.000 | 2.57 (1.22 to 5.40) | 0.013 |

| Cellular/fibrocellular crescents absent | ||||

| C0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| C1 | 1.09 (0.72 to 1.67) | 0.677 | 0.81 (0.48 to 1.37) | 0.440 |

| C2 | 3.42 (1.30 to 9.01) | 0.013 | 1.81 (0.56 to 5.83) | 0.321 |

ALB, serum albumin; BMI, body mass index; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate.

bmjopen-2018-023479supp001.jpg (411.7KB, jpg)

Discussion

IgA nephropathy can lead to several complications, including anaemia, renal hypertension, vascular disease, renal osteopathy and hyperuricaemia. Anaemia is one of the primary risks factors for kidney disease progression and is associated with a poor prognosis.15–17 When renal lesions are progressing, the prognosis is poor. The incidence of intrarenal arteriole lesions in patients with IgA nephropathy is reportedly higher than that in patients with non-IgA nephropathy and membranous nephropathy18 19; however, there have been few clinical and pathological studies of renal anaemia with large-scale populations conducted. In this study, we enrolled 462 patients for analysis. We found that the mean patient age was 36.6±11.3 years, and the male to female ratio was 272:190. These patients showed characteristics of the disease types of patients with IgA nephropathy, which primarily occurs in young men. In addition, 28.5% of patients met the diagnostic criteria for anaemia, and the rate of anaemia in males (21.3%) was lower than that in females (38.9%), making this the first study to report a higher incidence of renal anaemia in female patients with IgA nephropathy than in male patients with IgA nephropathy. The results of the regression analysis also suggested that the incidence of renal anaemia among female patients was higher than that in male patients. The specific reasons for this difference are still unknown; although androgen levels may play a role,20 21 additional studies are needed in the future. Therefore, clinicians should pay attention to female patients as renal anaemia rates clearly differ by sex. Clinical observations and interventions for renal anaemia should also differ by sex.

Our study showed that renal anaemia caused by IgA nephropathy had normocytic normochromic anaemia as the most common type of presentation, which was consistent with a previous study.22 The prevalence of anaemia increased with a reduction in eGFR levels in all age groups.23 24 Our findings support the hypothesis that as the eGFR is gradually reduced, the incidence of anaemia gradually increases, and there was a positive correlation between severity of anaemia and albumin. In patients with CKD stage 3 disease, the incidence of renal anaemia reaches 42.9%, which suggests that clinicians must consider the development of renal anaemia in these patients and that clinical intervention should be provided as necessary. All patients with CKD stage 5 disease show combined anaemia, and active treatment is required to delay the progression of renal function injury and increase patient quality of life.

IgA nephropathy refers to a group of diseases characterised by renal pathological damage, especially glomerular mesangial cell proliferation/immune complex deposition.25 The pathological characteristics of IgA nephropathy in this study showed that, compared with the non-anaemic group, the rate of mesangial proliferation (M1), interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy (T2) as well as the incidence of crescent lesion scores (C2), were higher in the anaemic group. These results suggest that pathological damage is associated with renal anaemia. The results of multivariable logistic regression analysis showed that having renal tubulointerstitial lesions ˃50% (T2) was associated with renal anaemia in patients with IgA nephropathy, and the degree of anaemia was most severe compared with T0 and T1. Mesangial proliferation, endocapillary proliferative lesions, segmental sclerosis or adhesion and the disease severity of crescent formation were not significantly associated with renal anaemia. This finding is important and consistent with our previous results, suggesting that severe renal tubulointerstitial lesions are an independent risk factor for IgA nephropathy.26 These results suggest that patients with IgA nephropathy combined with renal anaemia should be suspected of having renal tubulointerstitial lesions. Renal tubulointerstitial lesions lead to a reduction of erythropoietin (EPO), which is a hormone-like substance primarily secreted by renal tubulointerstitial cells that can regulate the proliferation and differentiation rates of erythrocyte precursors in the bone marrow to promote erythrocyte production.27 Maxwell et al 28 showed that the ability of interstitial fibroblasts to produce EPO decreased in an interstitial nephropathy experimental model. Fibroblasts are interstitial mesenchymal cells that structurally support epithelia by producing extracellular matrix. In chronic kidney injury, sustained inflammation accompanies the proliferation of interstitial fibroblasts and myofibroblasts,29 leading to renal fibrosis, which is the final common pathway for all CKD and eventually leads to renal failure.30 More importantly, the restoration of EPO production in the fibrotic kidney raises the possibility of a potential therapeutic approach towards treating renal anaemia.31 Our study confirmed that renal anaemia is associated with the severity of renal tubulointerstitial injury, which further suggests that the major cause of renal anaemia is the reduction in EPO production caused by renal tubulointerstitial injury. These results are also consistent with our clinical observations that renal anaemia occurs earlier and is more severe in patients with chronic interstitial tubulointerstitial injuries. This phenomenon might be associated with the early destruction of the interstitial cells that produce EPO.

The results of the logistic regression analysis showed that low ALB was a correlative factor for renal anaemia in patients with IgA nephropathy. At the same time, there was a positive correlation between severity of anaemia and albumin. The patients selected for this study had IgA nephropathy and were first diagnosed at our centre (diagnosis confirmed via renal biopsy); in other words, the enrolment had strict inclusion and exclusion criteria. Patients with a BMI <18.5 kg/m2 or malnutrition were excluded. In addition, the results suggested that prealbumin levels, an important indicator used to indicate nutritional status, did not significantly differ between the anaemic and non-anaemic groups. Therefore, although this study showed that the renal anaemia in patients with IgA nephropathy was associated with hypoproteinemia, the reasons for and mechanisms underlying this result remain unclear and require further exploration.

The main mechanism of renal anaemia is related to the reduction of EPO production after kidney injury. But Coulon et al 32 reported that polymeric IgA1 (pIgA1) positively regulates erythropoiesis through binding to transferrin receptor 1 (TfR1) and accelerates erythropoiesis recovery in anaemia. Under steady-state conditions, low concentrations of pIgA1 are produced by plasma cells, and most TfR1 combined with Fe-Tf, with little stimulation of downstream extracelluar regulated protein kinases( ERK) and Akt signalling pathways. Stress conditions such as hypoxia can lead to increase the pIgA1 production, allowing erythroid development to be boosted via ERK and Akt signalling.33 Elevated serum pIgA1 levels were often observed in patients with IgA nephropathy,34 based on the above research results, we speculate that the occurrence of renal anaemia in IgA nephropathy will be different from that of other causes of CKD, and it needs further research.

There are several important limitations to this study. As the study is cross-sectional, a causal relationship between influencing factors and anaemia cannot be determined. In future studies, renal anaemia and patient prognosis will be further evaluated to provide a reliable basis for improving patient quality of life and survival time as well as stronger evidence for renal anaemia management and treatment for clinicians. In addition, since our data were all from patients who underwent renal biopsy, some of the clinical patients initially identified did not undergo renal biopsy for various reasons; therefore, selection bias was present in our study. Data missing is another limitation of our study, such as Tibc, Fe and TS. There are more than 40% patients without these data (Tibc, Fe and TS) which are important indicators for distinguish iron deficiency anaemia (IDA) from non-IDA. But fortunately, the routine blood test indicated the IgA nephropathy anaemia is normocytic normochromic anaemia. That means IDA is not the reason for IgA nephropathy anaemia. At the same time, the reduction of EPO production is the major cause of renal anaemia, but EPO test was not available in daily clinical work in this retrospective study. In future prospective studies, we need to take EPO into observation and the design should be more scientific and stricter.

Conclusions

In summary, using a large study population, we identified that renal anaemia is a common complication in patients with IgA nephropathy. The anaemia type was primarily normocytic and normochromic. With the aggravation of renal dysfunction, the incidence of renal anaemia increased. Patients with CKD stage 3 disease and above should be monitored for renal anaemia development and possible intervention. The female sex, hypoalbuminaemia, eGFR reductions and severe renal tubulointerstitial lesions were identified as influencing factors for renal anaemia development in patients with IgA nephropathy. These findings provide new insight into our understanding of anaemia in IgA nephropathy and may improve the management and treatment of clinical renal anaemia.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Patient consent for publication: Next of kin consent obtained.

Contributors: YW, R-BW and X-MC contributed to design this study. YW, T-YS, M-JH and PL collected and analysed the data. YW, R-BW, T-YS and M-JH contributed to the preparation and editing of the manuscript. All authors agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work to ensure that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by grants from the National Sciences Foundation of China (grant numbers 81471027, 81273968, 81072914 and 81401160), Ministerial projects of the National Working Commission on Ageing (grant number QLB2014W002) and The Four hundred project of 301 (grant number YS201408), Beijing Nova Program (grant number Z161100004916129).

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Chinese PLA General Hospital.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

References

- 1. Eriksson D, Goldsmith D, Teitsson S, et al. Cross-sectional survey in CKD patients across Europe describing the association between quality of life and anaemia. BMC Nephrol 2016;17:97 10.1186/s12882-016-0312-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Portolés J, Gorriz JL, Rubio E, et al. The development of anemia is associated to poor prognosis in NKF/KDOQI stage 3 chronic kidney disease. BMC Nephrol 2013;14:2 10.1186/1471-2369-14-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Weiner DE, Tighiouart H, Vlagopoulos PT, et al. Effects of anemia and left ventricular hypertrophy on cardiovascular disease in patients with chronic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 2005;16:1803–10. 10.1681/ASN.2004070597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zoppini G, Targher G, Chonchol M, et al. Anaemia, independent of chronic kidney disease, predicts all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in type 2 diabetic patients. Atherosclerosis 2010;210:575–80. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2009.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Abramson JL, Jurkovitz CT, Vaccarino V, et al. Chronic kidney disease, anemia, and incident stroke in a middle-aged, community-based population: The ARIC Study. Kidney Int 2003;64:610–5. 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00109.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jurkovitz CT, Abramson JL, Vaccarino LV, et al. Association of high serum creatinine and anemia increases the risk of coronary events: results from the prospective community-based atherosclerosis risk in communities (ARIC) study. J Am Soc Nephrol 2003;14:2919–25. 10.1097/01.ASN.0000092138.65211.71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Vlagopoulos PT, Tighiouart H, Weiner DE, et al. Anemia as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality in diabetes: the impact of chronic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 2005;16:3403–10. 10.1681/ASN.2005030226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wyatt RJ, Julian BA. IgA Nephropathy. N Engl J Med Overseas Ed 2013;368:2402–14. 10.1056/NEJMra1206793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Julian BA, Novak J. IgA nephropathy: an update. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 2004;13:171–9. 10.1097/00041552-200403000-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. D’Amico G. Natural history of idiopathic IgA nephropathy: role of clinical and histological prognostic factors. Am J Kidney Dis 2000;36:227–37. 10.1053/ajkd.2000.8966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Philibert D, Cattran D, Cook T. Clinicopathologic correlation in IgA nephropathy. Semin Nephrol 2008;28:10–17. 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2007.10.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Aruga S, Horiuchi T, Shou I, et al. Relationship between renal anemia and prognostic stages of IgA nephropathy. J Clin Lab Anal 2005;19:80–3. 10.1002/jcla.20056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med 2009;150:604–12. 10.7326/0003-4819-150-9-200905050-00006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Trimarchi H, Barratt J, Cattran DC, et al. Oxford Classification of IgA nephropathy 2016: an update from the IgA Nephropathy Classification Working Group. Kidney Int 2017;91:1014–21. 10.1016/j.kint.2017.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Shu D, Xu F, Su Z, et al. Risk factors of progressive IgA nephropathy which progress to end stage renal disease within ten years: a case-control study. BMC Nephrol 2017;18:11 10.1186/s12882-016-0429-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Horwich TB, Fonarow GC, Hamilton MA, et al. Anemia is associated with worse symptoms, greater impairment in functional capacity and a significant increase in mortality in patients with advanced heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 2002;39:1780–6. 10.1016/S0735-1097(02)01854-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hörl WH. Anaemia management and mortality risk in chronic kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol 2013;9:291–301. 10.1038/nrneph.2013.21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wu J, Chen X, Xie Y, et al. Characteristics and risk factors of intrarenal arterial lesions in patients with IgA nephropathy. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2005;20:719–27. 10.1093/ndt/gfh716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zhuang Y, Chen X, Zhang Y. Multivariate analysis of influencing factors for hypertension in patients with IgA nephropathy. Chinese Journal of Internal Medicine 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Brockenbrough AT, Dittrich MO, Page ST, et al. Transdermal androgen therapy to augment EPO in the treatment of anemia of chronic renal disease. Am J Kidney Dis 2006;47:251–62. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2005.10.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Moriyama Y, Fisher JW. Effects of testosterone and erythropoietin on erythroid colony formation in human bone marrow cultures. Blood 1975;45:665–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Dmitrieva O, de Lusignan S, Macdougall IC, et al. Association of anaemia in primary care patients with chronic kidney disease: cross sectional study of quality improvement in chronic kidney disease (QICKD) trial data. BMC Nephrol 2013;14:24 10.1186/1471-2369-14-24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Astor BC, Muntner P, Levin A, et al. Association of kidney function with anemia: the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (1988-1994). Arch Intern Med 2002;162:1401–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Levin A, Thompson CR, Ethier J, et al. Left ventricular mass index increase in early renal disease: impact of decline in hemoglobin. Am J Kidney Dis 1999;34:125–34. 10.1016/S0272-6386(99)70118-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cattran DC, Coppo R, Cook HT, et al. The Oxford classification of IgA nephropathy: rationale, clinicopathological correlations, and classification. Kidney Int 2009;76:534–45. 10.1038/ki.2009.243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zhang Y, Chen X, Zhuang Y. [Clinical analysis of tubulointerstitial lesions in IgA nephropathy]. Zhonghua Nei Ke Za Zhi 2001;40:613–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Spivak JL. The mechanism of action of erythropoietin. The International Journal of Cell Cloning 1986;4:139–66. 10.1002/stem.5530040302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Maxwell PH, Ferguson DJ, Nicholls LG, et al. The interstitial response to renal injury: fibroblast-like cells show phenotypic changes and have reduced potential for erythropoietin gene expression. Kidney Int 1997;52:715–24. 10.1038/ki.1997.387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kriz W, Kaissling B, Le Hir M. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) in kidney fibrosis: fact or fantasy? J Clin Invest 2011;121:468–74. 10.1172/JCI44595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kaissling B, Le Hir M, Hm L. The renal cortical interstitium: morphological and functional aspects. Histochem Cell Biol 2008;130:247–62. 10.1007/s00418-008-0452-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Asada N, Takase M, Nakamura J, et al. Dysfunction of fibroblasts of extrarenal origin underlies renal fibrosis and renal anemia in mice. J Clin Invest 2011;121:3981–90. 10.1172/JCI57301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Coulon S, Dussiot M, Grapton D, et al. Polymeric IgA1 controls erythroblast proliferation and accelerates erythropoiesis recovery in anemia. Nat Med 2011;17:1456–65. 10.1038/nm.2462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Paulson RF. Erythropoiesis lagging? pIgA1 steps in to assist Epo. Nat Med 2011;17:1346–8. 10.1038/nm.2501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Valentijn RM, Radl J, Haaijman JJ, et al. Circulating and mesangial secretory component-binding IgA-1 in primary IgA nephropathy. Kidney Int 1984;26:760–6. 10.1038/ki.1984.213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-023479supp002.pdf (155.5KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-023479supp001.jpg (411.7KB, jpg)