Abstract

ThPOK is a “master regulator” of T lymphocyte lineage choice, whose presence or absence is sufficient to dictate development to the CD4 or CD8 lineages, respectively. Induction of ThPOK is transcriptionally regulated, via a lineage-specific silencer element, SilThPOK. Here, we take advantage of the available genome sequence data as well as site-specific gene targeting technology, to evaluate the functional conservation of ThPOK regulation across mammalian evolution, and assess the importance of motif grammar (order and orientation of TF binding sites) on SilThPOK function in vivo. We make three important points: First, the SilThPOK is present in marsupial and placental mammals, but is not found in available genome assemblies of nonmammalian vertebrates, indicating that it arose after divergence of mammals from other vertebrates. Secondly, by replacing the murine SilThPOK in situ with its marsupial equivalent using a knockin approach, we demonstrate that the marsupial SilThPOK supports correct CD4 T lymphocyte lineage-specification in mice. To our knowledge, this is the first in vivo demonstration of functional equivalency for a silencer element between marsupial and placental mammals using a definitive knockin approach. Finally, we show that alteration of the position/orientation of a highly conserved region within the murine SilThPOK is sufficient to destroy silencer activity in vivo, demonstrating that motif grammar of this “solid” synteny block is critical for silencer function. Dependence of SilThPOK function on motif grammar conserved since the mid-Jurassic age, 165 Ma, suggests that the SilThPOK operates as a silenceosome, by analogy with the previously proposed enhanceosome model.

Keywords: ThPOK, CD4, marsupial, placental, silencer

Introduction

The proper execution of biological processes depends on the highly orchestrated spatial and temporal expression of genes. Although gene transcription is initiated at promoters, which recruit the basal transcription machinery, fine tuning of expression pattern, and levels depends on collective action of multiple transcriptional regulatory elements (TREs), which may be more-or-less distant from the promoter, including enhancers and silencers (Arnosti and Kulkarni 2005).

Enhancers, which represent the best-studied category of remote regulatory element (Blackwood and Kadonaga 1998; Pennacchio et al. 2013; Shlyueva et al. 2014), are often associated with key developmental genes (Nobrega et al. 2003; Sandelin et al. 2004; Siepel et al. 2005), and studies in transgenic animals suggest that many of these elements function as tissue-specific enhancers during development (Nobrega et al. 2003; de la Calle-Mustienes et al. 2005; Pennacchio et al. 2006). Based on their structure/function correlations, enhancers have been broadly classified into two functional categories, that is, enhanceosomes and billboard enhancers. Enhancers that operate according to the enhanceosome model exhibit strong conservation of motif grammar, that is, the relative order, orientation, and spacing of TF motifs, and are highly sensitive to mutations of key nucleotides. Such enhancers act as scaffolds for higher order TF complexes of precise composition and organization, whose full activity requires occupancy of most TF sites (Thanos and Maniatis 1995; Merika and Thanos 2001; Panne et al. 2007; Panne 2008). Function of enhanceosomes is driven by cooperative action of multiple TFs, as affinity of individual TF binding sites may be quite weak (Farley et al. 2016). High cooperativity in TF binding in the enhanceosome model is thought to promote rapid switch-like activation, as occurs during the antiviral response in the case of the interferon-β enhancer, the best-studied example of such an enhancer. Such enhancers exhibit strong evolutionary conservation of their motif grammar, and may belong to the class of ultraconserved noncoding elements that are almost perfectly conserved between humans and rodents (Dimitrieva and Bucher 2013). The billboard model applies to enhancers which exhibit flexibility in motif grammar and TF binding, and retain substantial activity even if some TF motifs are not occupied (Arnosti and Kulkarni 2005; Spitz and Furlong 2012). Billboard enhancers are therefore expected to show greater evolutionary divergence compared with enhanceosomes, since by definition they can sustain small changes without drastic loss of function. Indeed, it is been argued that TRE mutations play an important role in evolution, by causing changes in gene expression that drive adaptation and speciation (King and Wilson 1975; Raff and Kaufman 1983; Wray et al. 2003; Rebeiz et al. 2009). Accordingly, many enhancers show rapid evolutionary divergence and are species- or lineage-specific (Villar et al. 2015).

The extent to which such models may be applicable to silencers, a class of TREs that exert context-dependent gene repression (Ogbourne and Antalis 1998; Kolovos et al. 2012), has not so far been explored. Compared with enhancers, silencers have been relatively neglected, although recent genome-wide approaches have shown them to be widespread and functionally diverse (Ogbourne and Antalis 1998; Riethoven 2010; Kolovos et al. 2012). Indeed, mutations of transcriptional silencer elements have been linked to several human diseases including asthma, fascioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy, and Huntington’s disease (Gabellini et al. 2002, 2003; Maston et al. 2006). We and others previously highlighted critical roles of silencers in development of the functionally distinct CD4 and CD8 T lymphocyte subsets (Sawada et al. 1994; Siu et al. 1994; He et al. 2008; Setoguchi et al. 2008).

CD4 and CD8 T lymphocytes develop in the thymus via a series of intermediate stages, defined by differential expression of the CD4 and CD8 surface markers (supplementary fig. 1, Supplementary Material online). Mature CD4 and CD8 SP (single-positive) cells arise from CD4+CD8+ (double-positive or DP) precursors via an intermediate CD4+ CD8lo stage. SP CD4 and CD8 cells correspond to distinct helper and killer lineages, whose TCRs recognize class II or class I Major Histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules, respectively. There is increasing consensus that differentiation of immature DP precursors to CD4 or CD8 lineage cells is controlled by differences in signaling by the clonotypic T cell receptor (TCR) (Singer et al. 2008). We previously have shown that the transcription factor ThPOK, encoded by the Zbtb7b gene, acts as a master regulator of this process in mice, such that its presence or absence dictates development to the CD4 or CD8 lineages, respectively (He et al. 2005). Since CD4 and CD8 T cells have been identified in vertebrates as far back as teleost (bony) fish, we carried out a bioinformatics search for ThPOK homologues in available vertebrate genomes. This revealed an unambiguous homolog of the gene encoding ThPOK (Zbtb7b) even in zebrafish (located on zChr16, and exhibiting 57% and 86% amino acid identity within critical BTB and Zn finger domains, respectively). Furthermore, a zebrafish knockout line that lacks functional ThPOK shows impaired development of CD4 helper T cells, demonstrating that the requirement for ThPOK in this process has been conserved for over 400 My (Li Q, Zhang Y, Zhongping D, Cai KQ, Li Y, Nicolas E, Liu X, Basu JM, Hua X, Shinton S, Wiest DL, Rhodes J, Hardy RR, Kappes DJ, submitted).

We and others have shown that in mice ThPOK expression in thymocytes and mature T cells is regulated primarily at the transcriptional level via several stage- and lineage-specific cis elements (He et al. 2008; Setoguchi et al. 2008). Of particular importance is the ∼350-bp silencer, SilThPOK, which is located several kb upstream of the distal ThPOK promoter, and seems to act only on the ThPOK gene. We further demonstrated that, the SilThPOK selectively shuts down ThPOK expression in cells that receive CD8 lineage-specifying signals via their surface T cell receptors (TCRs), but not in those that receive CD4 lineage-specifying signals (He et al. 2008). Deletion of the endogenous SilThPOK in mice causes promiscuous expression of ThPOK and diversion of all thymocytes to the CD4 lineage, demonstrating that the SilThPOK is essential for repression of ThPOK transcription during CD8 lineage commitment (Setoguchi et al. 2008). We have evidence from reporter knockin mice lacking the SilThPOK that it also plays a role in repressing ThPOK in several non-T cell and even nonlymphoid cell types (Mookerjee-Basu J and Kappes DJ, unpublished data), indicating that the SilThPOK may encode pleiotropic functions in multiple cell types.

In the present study, we examined the organization and function of the SilThPOK across mammalian evolution. Bioinformatic analysis shows that the SilThPOK is present in all sequenced genomes of therian mammals (placental mammals and marsupials), but not in other vertebrates, indicating that it represents a regulatory innovation of early mammals. Between marsupial and placental mammals, the motif “grammar” of the SilThPOK, that is, the relative order, orientation, and spacing of TF motifs, exhibits both conserved and divergent aspects. Thus, there are blocks of synteny with perfectly conserved motif grammar, while conservation of consensus TF binding sites across the whole SilThPOK is <50%. Using a genetic approach, we have tested functional conservation of the SilThPOK across mammalian evolution. Remarkably, we find that a marsupial SilThPOK supports normal T cell development when substituted for the endogenous SilThPOK in knockin mice. Using additional knockin mice with altered SilThPOK motif grammar, we directly establish that SilThPOK function depends critically on motif grammar within one of the syntenic blocks conserved between placental and marsupial mammals. This functional dependence on motif grammar suggests a “silenceosome” mode of action, analogous to the enhanceosome model.

Results

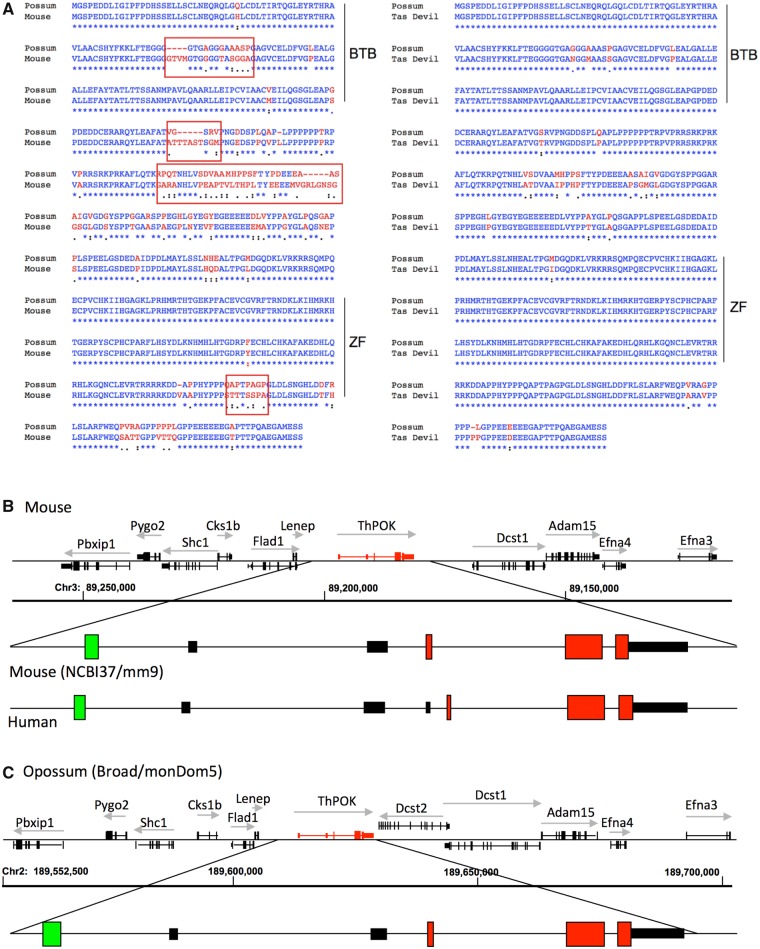

The ThPOK Silencer Is Conserved between Marsupial and Placental Mammals

BLAST analysis using the murine ThPOK cDNA as a probe identified unambiguous homologs of ThPOK in all three available marsupial genomes (gray short-tailed opossum, Monodelphis domestica; Tasmanian devil, Sarcophilus harrisii; and tammar wallaby, Macropus eugenii) (fig. 1a). Mouse and opossum ThPOK homologs exhibit 80% amino acid identity overall, and 99% identity within their DNA-binding domains. The opossum Zbtb7b gene is situated among the same neighboring genes, in the same transcriptional orientation and with the same exon/intron organization as in placental mammals (fig. 1b and c). Both placental and marsupial ThPOK genes contain alternative distal and proximal promoters, as evidenced by presence of highly homologous noncoding exons associated with these alternative start sites, suggesting shared transcriptional control mechanisms (supplementary fig. 2, Supplementary Material online).

Fig. 1.

ThPOK gene organization and sequence is highly conserved between marsupial and placental mammals. (a) Clustal alignment of ThPOK protein sequences (protein sequence deduced from nucleotide sequence in the case of marsupial ThPOK). Red boxes indicate regions of high sequence divergence between placental and marsupial sequences. BTB and ZF indicate location of functionally important POZ/BTB and Zinc finger domains, respectively. (b) Organization of mouse and human ThPOK genes (top right shows neighboring genes of mouse ThPOK locus). (c) Organization of opossum ThPOK gene. Red boxes and black boxes indicate positions of coding and noncoding exons, respectively. Green box indicates location of ThPOK silencer.

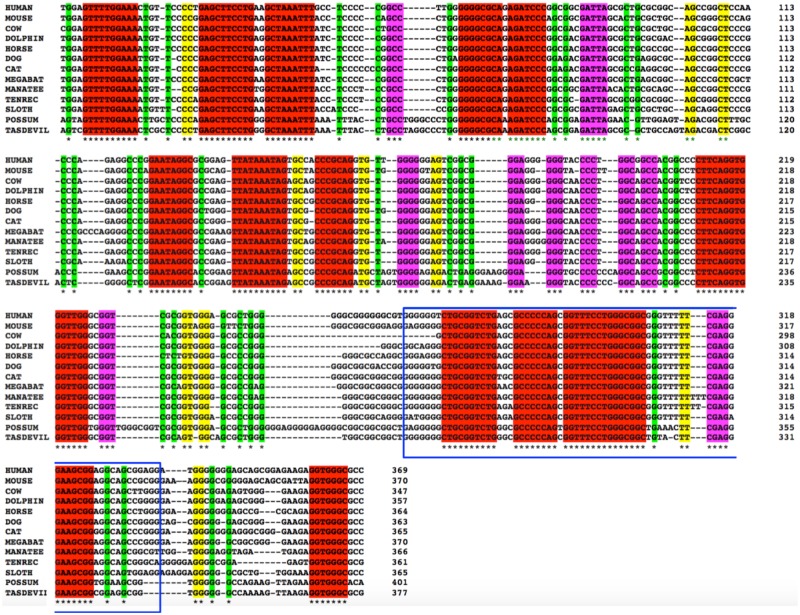

Since the SilThPOK element is critical for ThPOK developmental regulation in mice (He et al. 2008; Setoguchi et al. 2008), we used BLAST analysis to identify recognizable SilThPOK elements in other vertebrate genomes. SilThPOK homologs were found upstream of the ThPOK locus in all mammals, but not in any nonmammalian vertebrate. Among mammals, SilThPOK homologs were identified in two marsupials, opossum, and Tasmanian devil, which represent distinct American (Ameridelphia) and Australasian (Australidelphia) marsupial lineages, respectively, that diverged 70–80 Ma (Nilsson et al. 2004, 2010; Meredith et al. 2008) (the wallaby sequence has a gap in this region) (fig. 2). Human and opossum SilThPOK homologs exhibit 75% identity (vs. 89% nucleotide identity between two placental species, and 85% identity between two marsupials). SilThPOK conservation is significantly higher than for ThPOK coding exons (80% and 64% identity between mouse and human within the functionally important BTB and Zn finger domains). A 76-bp region within the silencer shows 95% identity between mouse and human, and is identified as a highly conserved noncoding element (HCNE) according to the ANCORA database (supplementary fig. 3c, Supplementary Material online) (Kikuta et al. 2007). HCNE sequence variation is likely constrained by severe selective pressure (Drake et al. 2006; Katzman et al. 2007), and ultraconserved regions can encode essential functions for normal development (Dickel et al. 2018). These results indicate that the SilThPOK arose prior to the divergence of placental and marsupial mammalian lineages (Luo et al. 2011), and that blocks of synteny within the silencer have been conserved since that time.

Fig. 2.

The ThPOK silencer is conserved between marsupial and placental mammals. Clustal alignment of ThPOK silencers from indicated species. Species were chosen from available mammalian genomes to reflect diverse lineages. Identity between all species is indicated by asterisk (bottom row). Identical residues are also color-coded according to length of contiguous homology, that is, 1 bp (green), 2 bp (yellow), 3–4 bp (purple), >5 bp (red). Blue box indicates the segment of the ThPOK silencer that corresponds to the highly conserved noncoding element according to ANCORA database (see supplementary fig. 3c, Supplementary Material online).

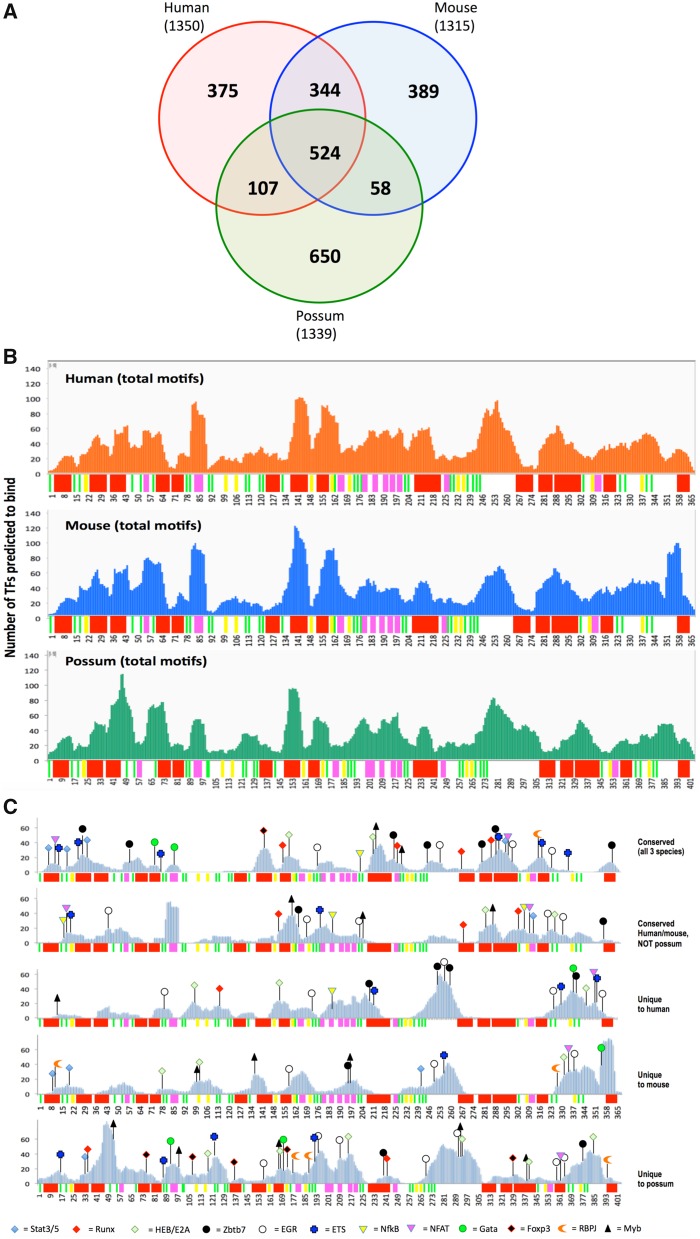

Bioinformatic Comparison of Transcription Factor Binding Profiles of Marsupial and Placental ThPOK Silencers

Binding of TFs to their corresponding targets defines the gene regulatory networks (GRNs) that control gene expression (Davidson et al. 2002; Walhout 2006). Accordingly, evolutionary changes in the TF repertoire and/or in their sequence binding preferences can induce large scale alterations in the gene expression program, thus representing a primary potential source of phenotypic variation and evolution. Therefore, we compared transcription factor binding profiles of marsupial and placental SilThPOK homologs. The fact that the marsupial SilThPOK element is 79% identical between human and opossum is not predictive of functional conservation (Cooper and Brown 2008; Weirauch and Hughes 2010). Even altering just a few bases within a TRE can cause marked phenotypic defects (Goode et al. 2011; Glassford and Rebeiz 2013; Rogers et al. 2013). Similarly, the python and coelacanth homologs of the mouse Shh ZRS enhancer show different capacities to substitute for the mouse Shh ZRS enhancer, despite similar nucleotide homology (73% vs. 75% identity to mouse enhancer, respectively) (Kvon et al. 2016). To evaluate conservation in TF binding, we first used a bioinformatics approach (http://jaspar.genereg.net) to identify locations of predicted TF consensus motifs within the human, mouse, and opossum elements. Using a relative profile score threshold of 80%, ∼1300 predicted TF binding sites are identified within each SilThPOK element, of which 524 are conserved in terms of relative position and orientation between all three species (40% of total predicted sites for mouse SilThPOK) (fig. 3a). Interestingly, TF consensus sites are distributed unevenly, with alternating peaks and troughs of TF site density. We speculate that peaks may represent important functional units, while troughs may act as “spacers” that ensure appropriate spacing/orientation between the former. Of note, while peaks often coincide with regions of high conservation between all three species (red regions, indicating sequence identity across a contiguous stretch of >7 bp), they also occur in nonconserved (white) regions (fig. 3b). Unsurprisingly, the 524 TF consensus sites that are precisely conserved in their relative position and orientation between species map predominantly to regions of high sequence conservation. Interestingly, they include a significant proportion of binding sites for TFs that have been implicated in lymphoid development, and/or control of the SilThPOK (Muroi et al. 2008; Setoguchi et al. 2008), for example, Egr, Runx, Gata, and ThPOK consensus sites (36, or 54% of these sites in the mouse SilThPOK are conserved in all three species) (fig. 3c, top row). An additional 23 sites of “lymphoid relevance” are conserved between mouse and human, but not opossum (fig. 3c, 2nd row). About 375, 389, and 650 TF consensus sites are unique to human, mouse, and opossum, that is, NOT conserved between any two species in terms of position and orientation. Of these species-specific sites, 20, 18, and 41 belong to the “lymphoid-relevant” category, as defined above, in human, mouse, and opossum, respectively (fig. 3c, rows 3–5). Some nonconserved “lymphoid-relevant” TF sites recur multiple times in the SilThPOK of all species (e.g., each species contains 3–7 Egr sites at different positions). There are also marked differences between nonconserved sites among mouse, opossum, and human silencer elements: 1) There are five Foxp3 sites unique to the opossum silencer, versus none in human or opossum (fig. 3c, bottom row). 2) The human SilThPOK elements contains a cluster of eight lymphoid-relevant consensus motifs (between 330 and 360 bp) that are absent in both mouse and opossum, which may represent a regulatory specialization unique to humans/primates (fig. 3c, 3rd row). Overall, the above analysis indicates that the ThPOK silencer exhibits features indicative of both long-term functional conservation, as indicated by 524 TF consensus motifs that are conserved between mouse, human, and opossum, as well as evolutionary divergence, as indicated by certain TF signatures unique to each species, particularly in the case of the opossum.

Fig. 3.

Transcription factor site organization for human, mouse and opossum ThPOK silencers. (a) TF consensus binding sites (as predicted by JASPAR algorithm) were mapped to ThPOK silencers for indicated species (total number of predicted consensus sites is indicated in brackets for each species). Using interspecies alignment shown in figure 2, each consensus site was classified as conserved or nonconserved (in position and orientation), relative to the other species. About 524 sites were found to be conserved between all three species. (b) Distribution of consensus site sequences from JASPAR for human, mouse and opossum ThPOK silencers were mapped onto silencer sequences for their respective genomes. Mapping was done using string mapping using a string search method. Resulting mapping sites were visualized in Integrative Genome Browser as coverage track. Note uneven distribution of consensus motifs across each element. Bars under each plot depict stretches of identical residues, color-coded as in figure 2. Note, however, that the sequence gaps inserted in figure 2 for alignment purposes have been removed, so that spacing of conserved elements differs slightly between species. (c) Sequence consensus sites from JASPAR for human, mouse and opossum, sorted into indicated categories according to conservation between different species, that is, sites conserved (in position and orientation) in all species (top row), conserved between human and mouse, but not opossum (2nd row), or unique to each species (rows 3–5). Sites of potential relevance to silencer regulation in lymphoid lineages are marked (see legend at bottom). Bars under each plot depict stretches of identical residues, color-coded as in figure 2.

Direct Assays of Transcription Factor Binding to ThPOK Silencer

To directly assess TF binding capacity of the mouse and opossum SilThPOK elements, we used a yeast-1-hybrid (Y1H) approach, a powerful tool for mapping GRNs (Reece-Hoyes, Barutcu, et al. 2011; Reece-Hoyes, Diallo, et al. 2011; Fuxman Bass et al. 2015). Y1H screening of full-length mouse and opossum SilThPOK elements against 1,086 different mammalian TFs, identified 45 and 34 interacting TFs, respectively, of which 26 were shared (table 1; indicated in red). Of note, these “shared” TFs are not necessarily conserved in position or number of sites between different species. RT-PCR analysis and on-line expression databases (Immgen), indicate that 19 of the 26 shared factors are expressed in murine T cell lymphocytes (table 1; underlined), supporting the functional relevance of these results. Given that detection of TF binding in Y1H may depend on precise nucleosome positioning and/or distance of the TF binding site to the yeast promoter (Sparks et al. 2016), we carried out a second Y1H analysis using 12 different subfragments of the mouse SilThPOK (covering the central, 115–329 bp, portion of the silencer) (supplementary fig. 4a, Supplementary Material online). This revealed an additional 20 binding factors, increasing the total obtained by this method to 65. In comparison, JASPAR analysis predicts that this region of the mouse SilThPOK element can bind 229 different factors. In addition, several lymphoid-relevant TFs identified as binding to the mouse and opossum SilThPOK by JASPAR prediction and/or based on published results (e.g., Gata3) were not identified by the Y1H analysis, together suggesting that the Y1H analysis may not yield a comprehensive list of binding factors. Possible reasons for this include that not all factors are present in our Y1H library, and that some TFs require secondary modification or complex formation with other factors to bind, as well as aforementioned issues related to nucleosome and promoter positioning. To further evaluate binding of factors predicted by JASPAR but not detected by Y1H, we used publicly available ChIP data for selected TFs, which showed binding by nine additional factors predicted by JASPAR, but not detected by Y1H (supplementary fig. 4b, Supplementary Material online). Finally, some TFs that are shown to bind to the SilThPOK by Y1H or ChIP are not detected by JASPAR analysis, which may reflect gaps in the JASPAR TF consensus site database, the level of stringency used in the JASPAR analysis, and/or the methodology by which JASPAR data was obtained (EMSA vs. ChIP).

Table 1.

Transcription factors that directly bind to the mouse and opossum SilThPOK elements by yeast-1-hybrid analysis. TFs expressed in murine T lymphocytes are underlined.

| Cis Element | Factors Bound in Y1H Assay |

|---|---|

| ThPOK Silencer (mouse) | E2f1, Ebf3, Egr1, Gcm1, Glis2, Gmeb1, Hes5, Hey2, Irf9, Klf3/4/15, Maz, Myocd, Mxd1, Nr1l2, Plag1/L1, Rel, Rfx2, Runx1, Smad4, Sox14, Sp4, Tal2, Tfap2A/2B/2E, Tgif2lx, Wt1, Znf281, Zbtb7a (Lrf), Zbtb7b (ThPOK), Zbtb10, Zdhhc5/7/9/11/15/17/20/22, Zic1/3, Znf622/740 |

| ThPOK Silencer (possum) | Ebf1/3, Gcm1, Glis1/2, Hey2, Klf3/4/15, Patz1, Plag1/L1, Rel, Rfx4, Runx1/3, Satb2, Smad4, Sp4, Tfap2a/2B/2E, Wt1, Znf281, Zbtb7a (Lrf), Zbtb7b (ThPOK), Zbtb10, Zdhhc7/9/11, Zic1/3, Znf398/581/740/746 |

Marsupial Homolog of SilThPOK Supports Normal CD4–CD8 Development in Mice

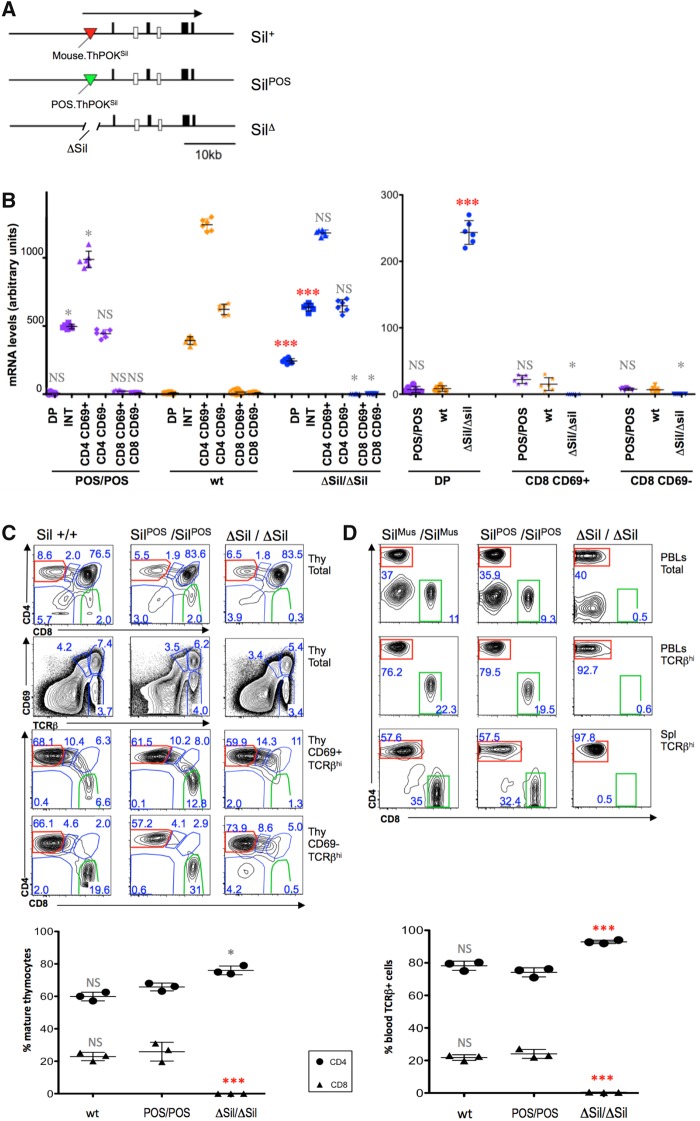

The above analysis indicates both substantial overlap and significant divergence in TF binding profiles between marsupial and placental SilThPOK elements, making it difficult to predict to what extent their functions have been preserved. Even very similar cis elements may not work the same when interchanged across species (Kvon et al. 2016). To test functional conservation directly, we used a ZFN-mediated approach to generate knockin mice in which the endogenous murine SilThPOK is precisely replaced by its opossum homolog (ThPOK-SilPOS mice) (supplementary figs. 5 and 6, Supplementary Material online). We first generated knockout mice lacking the SilThPOK on the C57BL/6 background (ThPOK-ΔSil mice), to abolish silencer function, and then knocked the opossum SilThPOK homolog back into the ThPOK-ΔSil background, to assess whether it can restore function (fig. 4a).

Fig. 4.

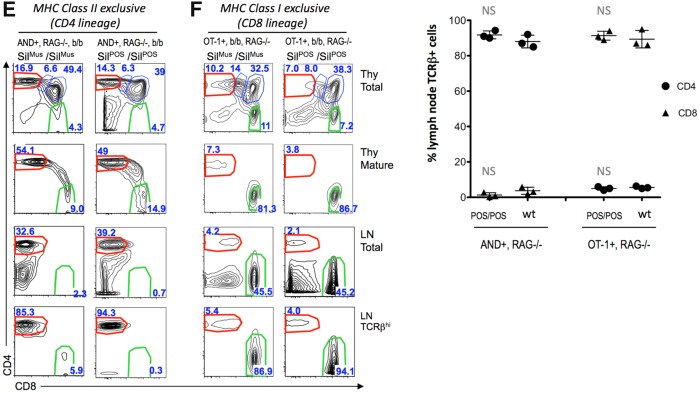

Marsupial SilThPOK supports normal ThPOK regulation in developing thymocytes. (a) Schematic of ThPOK gene organization in wt (top), SilPOS knockin (middle), and SilΔ knockin mice. Black boxes indicate exons. Enhancers are shown as white boxes, and the silencer as a triangle (red and green for mouse and opossum, respectively). Thick black arrow at top indicates transcriptional orientation. (b) RT-PCR analysis, showing relative expression of ThPOK mRNA in indicated sorted thymocyte subsets of wt, homozygous ThPOK-SilPOS, and homozygous ThPOK-SilΔ mice. Results are a combination of six biological replicates per strain. Right-hand panel shows ThPOK expression for DP and SP CD8 subsets at a larger scale, to allow small expression differences to be more readily discerned. (INT = “intermediate” CD4+8lo subset). (c) FACS analysis of CD4, CD8a, TCRβ and CD69 expression in indicated electronically gated thymocyte subsets of wt (ThPOK-Sil +/+), ThPOK-SilPOS/SilPOS, and ThPOK- SilΔ/SilΔ, mice. Plot at bottom shows % of SP CD4 and CD8 cells within gated mature (CD69-, TCRβ+) fraction (n = 3, for each strain). (d) FACS analysis of CD4, and CD8a expression in indicated peripheral lymphocyte populations of wt, ThPOK-SilPOS, and ThPOK- SilΔ mice (PBLs = peripheral blood lymphocytes; Spl = spleen). Cells gated for high TCRβ expression (TCRβ +) consist exclusively of T cells, in contrast to total PBLs and splenocytes (which also contain other white blood cell types). Plot at bottom shows % of SP CD4 and CD8 cells within gated TCRβ+ PBLs (n = 3, for each strain). (e) FACS analysis of CD4, and CD8a, expression in indicated thymocyte and lymph node subsets from mice expressing the MHC class II-restricted TCR transgene, AND. (f) FACS analysis of CD4, and CD8a expression in indicated peripheral lymphocyte populations, from mice expressing the MHC class I-restricted TCR transgene, OT-1. Plot at right shows % of SP CD4 and CD8 cells within gated TCRβ+ fraction (n = 3, for each strain). Error bars in (b), (c), (d) and (f) represent standard deviations. Significant differences between mutant and wt mice were determined by paired T test, and indicated by asterisks (*P>0.01; **P> 0.005; ***P> 0.001).

We employed three distinct and unambiguous criteria to assess in vivo function of the ThPOK-SilPOS in the context of these knockin mice: 1) The first employs RT-PCR to detect changes in ThPOK mRNA expression in sorted thymocyte and mature T cell subsets. ThPOK expression in wt mice is precisely regulated and narrowly restricted to cells developing to the CD4 lineage (supplementary fig. 1, Supplementary Material online). 2) The second is based on the ratio of mature CD4 to CD8 T cells, which is genetically determined and in healthy C57BL/6 mice tightly maintained ∼2:1. 3) The third is based on the ability of TCR transgenes to restrict development to a particular T cell lineage. In C57BL/6 mice, the AND and OT-1 TCR transgenes, restrict development of all T cells to the CD4 or CD8 lineages, respectively.

In wt mice, ThPOK is expressed in thymocytes developing to the CD4 lineage beginning at the CD4 + 8lo stage, but not in thymocytes developing to the CD8 lineage, and is specifically absent in DP and SP CD8 thymocytes and SP CD8 T cells. We show that deletion of the silencer leads to significant ThPOK expression in DP thymocytes (and abolishes CD8 development). Strikingly, insertion of the marsupial SilThPOK into ThPOK-SilΔ mice restored normal stage-specific transcription of ThPOK, including silencing in DP and SP CD8 cells (fig. 4b).

Given the critical role of ThPOK in control of CD4/CD8 lineage commitment, misregulation of ThPOK results in altered proportions of SP CD4 and CD8 T lymphocytes. Accordingly, ThPOK-ΔSil mice, which exhibit aberrant ThPOK expression starting at the DP thymocyte stage, show almost exclusive development of CD4 T cells and an extremely high CD4: CD8 ratio (fig. 4b and c). Strikingly, insertion of the marsupial SilThPOK restored normal T cell development, even in homozygous ThPOK-SilPOS mice, as evidenced by restoration of normal proportions of SP CD8 thymocytes and mature CD8 T cells (fig. 4c and d). Note that there is some individual variation in SP CD8 proportions among ThPOK-SilPOS mice, as for wt mice, but the range of variation is similar in both cases (fig. 4c).

A critical feature of normal T cell development is that MHC class I-specific thymocytes develop toward the CD8 lineage, whereas MHC class II-specific thymocytes develop toward the CD4 lineage (supplementary fig. 1b, Supplementary Material online). It was possible that this specificity was disrupted in ThPOK-SilPOS mice, despite the superficially normal CD4: CD8 T cell ratio. To test this, we limited T lymphocyte development to either MHC class I or class II specific thymocytes by crossing ThPOK-SilPOS mice to TCR transgenic mice that express exclusively MHC class I (OT1) or class II-specific (AND) TCRs, respectively. Importantly, ThPOK-SilPOS/POS mice supported accurate MHC class-specific T cell development in the presence of TCR transgenes (fig. 4e and f). This result was confirmed by crossing ThPOK-SilPOS mice with either MHC class II knockout or class I knockout mice. In C57BL/6 mice, ablation of MHC class II or class I restricts development of all T cells to the CD8 or CD4 lineages, respectively. The same effect was observed for ThPOK-SilPOS/POS mice (supplementary fig. 7, Supplementary Material online, and data not shown). Collectively, these data indicate that SilThPOK function has been evolutionarily conserved between marsupial and placental mammals, at least with regard to its role in T cell development.

Function of the SilThPOK Is Orientation-Independent

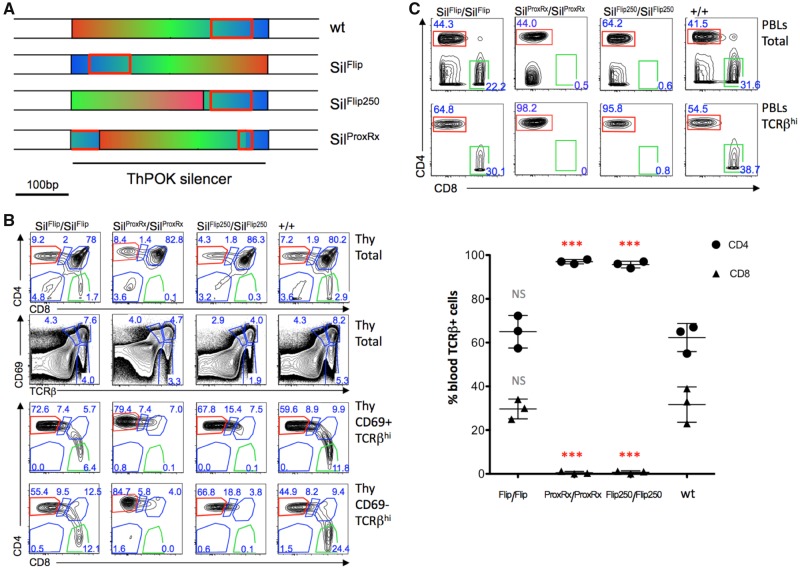

Examination of mouse gene expression databases (USCS genome browser) and our own RT-PCR analysis indicate that the SilThPOK can be transcribed in some cell types, as part of an independent mRNA that is transcribed in reverse orientation to the ThPOK gene, and that the resulting transcript includes several potential translational open-reading frames (supplementary fig. 8, Supplementary Material online; data not shown). RNAs or proteins resulting from SilThPOK transcription might mediate important transacting functions, as has been reported for other cis elements (Mousavi et al. 2014). To test this possibility, we generated knockin mice in which the whole SilThPOK was inverted (ThPOK-SilFlip mice), which should block any orientation-dependent transacting functions of the SilThPOK, while preserving cis-acting functions, that are generally considered orientation-independent (Maston et al. 2006) (fig. 5a). Significantly, CD4 T cell development and peripheral T cell subset distribution is unaltered in homozygous ThPOK-SilFlip mice, indicating that control of ThPOK expression in the thymus is unaffected (fig. 5b and c). Hence, the SilThPOK exhibits classical orientation-independence and does not encode a transcript important for CD4/CD8 lineage choice.

Fig. 5.

ThPOK silencer functions in an orientation-independent manner. (a) Schematic of SilFlip, SilFlip250 and SilProxRx alleles. Color patterns serve to indicate organization/orientation of variant silencers (bottom bars) compared with wt silencer (top bar). (b) FACS analysis of CD4, and CD8 expression on indicated thymocyte subsets from +/+, SilFlip/SilFlip, SilFlip250/SilFlip250 and SilProxRx/SilProxRx mice. (c) FACS analysis of CD4, CD8, TCRβ and CD69 expression on indicated peripheral blood subsets from same mice as in panel (b). Plot at bottom shows % of SP CD4 and CD8 cells within gated TCRβ+ PBL fraction (n = 3, for each strain). Note almost complete loss of SP CD8 cells in SilFlip250/SilFlip250 and SilProxRx/SilProxRx mice. Error bars represent standard deviations. Significant differences between mutant and wt mice were determined by paired T test, and indicated by asterisks (*P>0.01; **P> 0.005; ***P> 0.001).

Motif Grammar Dependence of SilThPOK Function

Evolutionary conservation of 524 TF consensus sites between marsupial and placental silencer homologs is consistent with a “silenceosome”-like mode of function, that depends on rigid motif grammar. We tested this hypothesis directly by altering position/orientation of the HCNE located within the silencer (supplementary fig. 3c, Supplementary Material online). First, we generated ThPOKSilProxRx knockin mice in which 40 bp of this element containing two conserved Runx binding motifs are moved to the 5′ end of the SilThPOK (fig. 5a). These conserved Runx sites have previously been shown to be important for silencing activity of the SilThPOK (Setoguchi et al. 2008). Strikingly, ThPOKSilProxRx mice showed loss of silencing function in developing thymocytes, as indicated by failure of CD8 commitment (fig. 5b and c; note absence of CD8 T cells), similar to ThPOKSilΔ control mice (fig. 4c and d). To selectively assess effect of ThPOKSilProxRx on development of MHC class I-specific thymocytes, we crossed ThPOKSilProxRx mice to MHC class II knockout background in which only class I-specific thymocytes can develop. This demonstrated that the ThPOKSilProxRx mutation caused almost complete redirection of MHC class I-specific T cells to the CD4 lineage, indicating abolition of silencer function (supplementary fig. 9, Supplementary Material online). Importantly, the variant ThPOKSilProxRx could still bind Runx factors (supplementary fig. 3d, Supplementary Material online). Thus, central positioning or structural integrity of the HCNE is critical for proper function of the SilThPOK, rather than simply reflecting a requirement for Runx binding.

Next we asked whether position/orientation of other transcription factor binding sites with respect to the HCNE was important for SilThPOK function, by generating knockin mice in which the distal 250 bp of the SilThPOK was inverted. In resulting ThPOKSilFlip250 mice, the position/orientation of the HCNE is unaltered, while the sequences immediately 5′ to the HCNE are moved 250 bp away. Homozygous ThPOKSilFlip250 mice exhibited a block of silencing function, as evidenced by absence of CD8 T cells (fig. 5b and c). We specifically tested the fate of MHC class I-restricted thymocytes by backcrossing ThPOKSilFlip250 mice to MHC class II knockout mice, which showed that MHC class I-specific T cells underwent almost complete redirection of to the CD4 lineage (data not shown). Collectively, these data indicate that relative spacing and/or orientation of TF binding sites within the ThPOK silencer is critical for function, consistent with a silenceososome rather than billboard model of silencer function. The variant ThPOKSilFlip250 could still bind Runx factors (supplementary fig. 3d, Supplementary Material online).

Discussion

Although evolution of immune genes has been extensively studied at the DNA/protein sequence level, only few studies have addressed evolution of immune gene regulation at the functional level. Here, we have used a genetic strategy to track evolution of gene regulation of the transcription factor ThPOK, the master regulator of CD4–CD8 lineage choice. We demonstrate that motif grammar and function of the SilThPOK have been highly conserved since divergence of marsupial and placental mammals, and that SilThPOK function is highly dependent on motif grammar, indicating that specific combinatorial TF binding is essential for silencer function. Thus, the SilThPOK appears to operate as a “silenceosome,” analogous to the previously described enhanceosome model.

TRE (transcriptional regulatory element) swap experiments that involve substituting homologous cis elements of the same gene from a different species are critical to define evolutionary origins of transcriptional regulatory networks, but are rarely performed in vivo. Most prior experiments of this nature have utilized a transgenic approach, whose physiological relevance is limited due to integration site and copy-number dependence of transgene regulation, and absence of normal chromatin and regulatory context (Ludwig et al. 2005; Gordon and Ruvinsky 2012). Furthermore, almost all such studies have been carried out in experimentally more tractable invertebrate models. In vertebrates, only two interclass cis element swap studies employing a knockin strategy have been reported (Cretekos et al. 2008; Kvon et al. 2016). In one study, deletion of the Shh ZRS enhancer was found to cause severe limb malformation in mice, which could be corrected by swapping in the homologous coelacanth element, demonstrating conserved function since divergence of fish from other vertebrate lineages (Kvon et al. 2016). Of note, the functional requirement for the Shh ZRS enhancer in coelacanth was not explicitly verified in this study, as it is not currently feasible to generate knockouts in most nonrodents. The other study, involving replacement of the limb-specific Prx1 enhancer in mice by its bat homolog proved uninformative for testing conserved function, since the mouse element was functionally redundant (i.e., knockout caused no phenotype) (Cretekos et al. 2008).

As far as we know, our study is the first to use a knockin approach to demonstrate functional equivalency of a silencer across evolution. The only prior study touching on this topic, used a transgenic reporter approach to show that a mouse element involved in imprinting of the H19/Igf2 genes could function as a silencer in transgenic reporter assays in Drosophila (Brenton et al. 1999; Drewell et al. 2000). Apart from limitations of the transgenic approach, this interpretation has been questioned, because the mouse element contains CTCF sites more typical of insulators, and because its activity in Drosophila is regulated by a factor not found in mammals (Schoenfelder and Paro 2004). Hence, our infraclass swap of SilThPOK elements represents a significant addition to the functional evaluation of conserved cis-regulatory elements, particularly silencers.

The fact that the opossum SilThPOK can substitute functionally for the mouse SilThPOK in CD4 development implies that the opossum SilThPOK is interacting with key mouse TFs that normally control the mouse SilThPOK during this process. The alternative interpretation that the opossum SilThPOK can mediate the same functional outcome by a nonconserved mechanism, that is, by interacting with a different set of TFs in the mouse than in the opossum, seems unlikely. Of note, although the role of ThPOK in CD4 commitment has not been formally proven for marsupials (i.e., by gene targeting, which is currently not feasible for marsupials), we have obtained evidence for such a role in much more primitive zebrafish, implying that it is common to all vertebrates (Li Q, Zhang Y, Zhongping D, Cai KQ, Li Y, Nicolas E, Liu X, Basu JM, Hua X, Shinton S, Wiest DL, Rhodes J, Hardy RR, Kappes DJ, submitted). Hence, we would suggest that the marsupial SilThPOK also controls ThPOK expression during thymocyte development in marsupials. Furthermore, we would predict that key TFs that interact with the SilThPOK during thymic development would also be evolutionarily conserved between marsupial and placental mammals. Indeed, the most important known regulator of SilThPOK function, Runx3, shows 82% identity at the amino acid level between opossum and humans (data not shown). Further, altering the organization/position of the most highly conserved syntenic block within the mouse SilThPOK disrupts its function.

Our analysis reveals recognizable SilThPOK elements only in mammals. Given that the ancestors of modern mammals (synapsids) diverged from those of modern reptiles and birds ∼320 Ma (Carrroll 1964), this shows that the SilThPOK element arose in its present form after that time, but before divergence of marsupial and placental mammals 160 Ma. Despite the likely absence of a bona fide silencer element in nonmammalian vertebrates, it is well-established that functionally divergent CD4 and CD8 T cell subsets exist in nonmammalian vertebrates, as far back as teleost fish (Toda et al., 2011; Somamoto et al. 2014; Yoon et al. 2015; Dee et al. 2016). Furthermore, amphibians display characteristic CD8 T cell-mediated MHC I-restricted cytotoxicity and CD4 T cell-mediated MHC II-restricted help of B cell responses (Robert 2016). Although lower vertebrates lack a true SilThPOK homolog, examination of the Xenopus laevis genome reveals presence of seven perfect Runx consensus sites (TGTGGT) within a 750-bp region of the first ThPOK intron, which might represent a primordial Runx-dependent silencing element (data not shown).

Our study is the first to examine function of a TRE associated with a marsupial immune gene, and to suggest that it is functionally equivalent to its placental homolog. This seems to reflect particularly strong conservation of the CD4/CD8 commitment process in mammals, as also evidenced by similar distribution of CD4 and CD8 T cells in thymus and other lymphoid organs of marsupials and placental mammals (Howson et al. 2014). In contrast, some other aspects of T cell development are quite divergent between marsupial and placental mammals, that is, 1) Delayed T cell production in newborn marsupials versus placentals (Baker et al. 1999; Old and Deane 2000, 2003). 2) Unusual anatomical locations and numbers of thymi (Yadav 1973; Deane and Cooper 1988; Hubbard et al. 1991; Haynes 2001). 3) Different programs of TCR rearrangement and usage, including reversal of γδ and αβ T cell appearance in thymic ontogeny, and expression of a “primitive” TCRμ chain (Parra et al. 2007, 2008, 2009; Wong et al. 2011). 4) Strong sequence divergence of many key immune genes (e.g., very weak similarity between marsupial and placental CD4 coding exons) (Belov et al. 2007; Duncan et al. 2007; Wong et al. 2011). Apart from providing comparative insights into the evolution of the adaptive immune system of placental mammals, study of the marsupial immune system may have practical significance, for instance in developing strategies to combat contagious facial cancer in Tasmanian devils (Pearse and Swift 2006). Opossums represent an excellent model organism for this purpose, because they are small, can be housed in mouse cages, and are almost as fecund as mice (average litter size is eight) (Keyte and Smith 2008). Moreover, experimental manipulation of developing marsupials does not require invasive procedures on the mother.

The most important implication of our study is that SilThPOK function is highly dependent on motif grammar, suggesting a “silenceosome”-like mode of function, whereby even small changes in TF binding would severely impact its function. In particular, we uncovered the critical importance of position and orientation of the HCNE region within the SilThPOK. Our results indicate that specific position of the HCNE within the SilThPOK is critical for its lineage specific activity, as evidenced by near complete abolition CD8 lineage in ThPOKSilProxRx mice. Moreover, we found that local orientation and spacing of TF sites near the HCNE are essential for lineage specific SilThPOK activity in thymocyte development, as indicated by similar abrogation of CD8 development in ThPOKSilFlip250 mice. Importantly, inversion of the whole SilThPOK (ThPOKSilFlip mice) does not impair CD8 development, supporting that motif grammar rather than overall orientation of the SilThPOK is critical for its function. Given the key roles of CD4 and CD8 T cells for effective immunity against foreign pathogens, altering their numbers and/or proportions would have direct harmful consequences on fitness of the organism. In addition, ThPOK is expressed in diverse tissues, both immunological and nonimmunological, and analysis of reporter knockin mice reveals that deletion of the SilThPOK leads to derepression of ThPOK in several of these tissues (Mookerjee-Basu J and Kappes DJ, unpublished data). Interestingly, 75% of ThPOK knockout embryos die in utero for unknown reasons (Lee H-O and Kappes DJ, unpublished data). This suggests pleiotropic developmental functions of ThPOK and of the SilThPOK in diverse tissues, which are important for viability.

In summary, this is the first in vivo study to identify a putative silenceosome. In the extensively studied IFN-β enhanceosome, high evolutionary conservation is imposed by a requirement for binding of eight different TFs simultaneously (Panne 2008). Our bioinformatics and Y1H analyses have revealed numerous TFs that could potentially participate in the formation of this proposed silenceosome. Future work will reveal how assembly of these factors at the SilThPOK regulates its activity, and how TCR signals may perturb this assembly in order to turn off SilThPOK activity at precise developmental stages.

Materials and Methods

Mice

All experimentation involving animals was approved by Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC), Fox Chase Cancer Center. OT-1-TCR (Hogquist et al. 1994) and AND TCR transgenic lines, MHC class II -/- as well as β2m-/- have been procured from Jackson Laboratory. All other mouse lines described in this paper have been generated by the FCCC Transgenic Facility. Animal care was in accordance with NIH guidelines.

ZFN-Mediated Gene Targeting in Mouse Embryos

A site-specific pair of ZFN RNAs that recognizes a target site 70-bp upstream of the ThPOK silencer was designed and generated by Millipore-Sigma (Genome Editing division). mRNAs encoding the two site-specific ZFNs (50 ng/μl) were introduced into 1-cell mouse oocytes by pronuclear injection, and injected oocytes were transferred to a pseudopregnant surrogate mother. Positive founder pups were identified using mutation-specific primers, and mated to C57BL/6 mice to generate stable heritable knockin lines. In pilot experiments, in which embryos were injected only with ZFN mRNAs, ∼70% of founders showed small deletions or insertions at the ZFN target site, resulting from NHEJ-mediated repair of double-stranded DNA breaks caused by site-specific ZFNs (supplementary fig. 7a and b, Supplementary Material online). To introduce specific mutations, oocytes were coinjected with ZFN mRNAs as well as a homologous donor construct (2 ng/ml) containing the desired alteration. In our hands, 2–10% of founders exhibited site-specific introduction of the desired mutation by homologous recombination (supplementary fig. 4c–f, Supplementary Material online). Constructs consisted of 1.5-kb 5′ and 0.8-kb 3′ arms of homology flanking the mutant ThPOK silencer sequence. The SilΔ construct lacks the entire 418-bp silencer sequence, and so contains no sequence between the homology arms (see fig. 1d for mouse silencer sequences). In the case of the SilPOS construct, the 418-bp mouse silencer is replaced by the 464-bp opossum silencer in the same orientation (see fig. 1d for opossum silencer sequences). In the case of the SilFlip and SilFlip250 constructs, either the entire mouse silencer or the most distal 250 bp of the silencer are inverted. The ZFN target sequence is ACCGCTACCCTAACCcataaCTGGAAGGGGTTTAG (capital letters denotes nucleotides actually bound by right and left ZFN proteins). The PCR primers used to type for replacement of the mouse ThPOK silencer by the opossum silencer are: Opossum F: 5′-AGAACGTTGGAGTAGACGGCTTTGCA; Mouse R (external to the HR construct): 5′-ACGCCCTAGGTCAAGTCTGA.

Antibodies

All fluorescently labeled antibodies used were obtained from commercial sources (ebioscience), including anti-Thy1, TCRβ, γδTCR, CD4, CD8, CD69, HSA, CD62l.

RT PCR

Cellular subsets were stained with antibodies described earlier, FACS sorted and RNA was generated according to standards protocols. RT PCR for quantitation of ThPOK mRNA was carried out as described previously (He et al. 2008).

Enhanced Yeast One-Hybrid Assays

Protein–DNA interactions with the mouse ThPOK silencer, and opossum ThPOK silencer were determined using enhanced yeast one-hybrid assays as described (Reece-Hoyes, Diallo, et al. 2011; Fuxman Bass et al. 2015). Briefly, each DNA sequence was cloned upstream the HIS3 and LACZ reporter genes and integrated into the yeast genome to generate yeast DNA-bait strains. These DNA-bait strains were then screened against an arrayed collection of 1,086 human TFs (Fuxman Bass et al. 2015). Human TFs can be used as a proxy for mouse and opossum TFs given the high sequence and specificity conservation between TF orthologs in mammals (Jolma et al. 2013). Interactions were tested in quadruplicate using both reporters, detected using the web tool Mybrid (Reece-Hoyes et al. 2013) and manually curated. Only the interactions detected in at least two colonies were considered positive. For each DNA sequence, two independent yeast DNA-bait strains were tested. Interactions that do not replicate in one test, usually replicate if more strains are tested, and thus the union of the protein–DNA interactions is reported.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary data are available at Molecular Biology and Evolution online.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants R01 AI068907 (D.J.K.), R01 GM107179 (D.J.K.), R01 GM082971 (JFB and A.J.M.W.), and P30 CA006927 (FCCC Comprehensive Cancer Center Core Grant). We gratefully acknowledge Gregory Davis (Head of Genome Engineering R&D, Millipore-Sigma) for advice on ZFN-mediated genome engineering. We acknowledge the assistance of the following core facilities of the Fox Chase Cancer Center: Flow Cytometry, Cell Culture, DNA Sequencing, and Laboratory Animal.

References

- Arnosti DN, Kulkarni MM.. 2005. Transcriptional enhancers: intelligent enhanceosomes or flexible billboards? J Cell Biochem. 94(5):890–898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker ML, Gemmell E, Gemmell RT.. 1999. Ontogeny of the immune system of the brushtail possum, Trichosurus vulpecula. Anat Rec. 256(4):354–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belov K, Sanderson CE, Deakin JE, Wong ES, Assange D, McColl KA, Gout A, de Bono B, Barrow AD, Speed TP.. 2007. Characterization of the opossum immune genome provides insights into the evolution of the mammalian immune system. Genome Res. 17(7):982–991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackwood EM, Kadonaga JT.. 1998. Going the distance: a current view of enhancer action. Science 281(5373):60–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenton JD, Drewell RA, Viville S, Hilton KJ, Barton SC, Ainscough JF, Surani MA.. 1999. A silencer element identified in Drosophila is required for imprinting of H19 reporter transgenes in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 96(16):9242–9247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrroll RL. 1964. The earliest reptiles. Zool J Linn Soc. 45:61–83. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper GM, Brown CD.. 2008. Qualifying the relationship between sequence conservation and molecular function. Genome Res. 18(2):201–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cretekos CJ, Wang Y, Green ED, Program NCS, Martin JF, Rasweiler JJt, Behringer RR.. 2008. Regulatory divergence modifies limb length between mammals. Genes Dev. 22(2):141–151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson EH, Rast JP, Oliveri P, Ransick A, Calestani C, Yuh CH, Minokawa T, Amore G, Hinman V, Arenas-Mena C, et al. 2002. A genomic regulatory network for development. Science 295(5560):1669–1678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Calle-Mustienes E, Feijoo CG, Manzanares M, Tena JJ, Rodriguez-Seguel E, Letizia A, Allende ML, Gomez-Skarmeta JL.. 2005. A functional survey of the enhancer activity of conserved non-coding sequences from vertebrate Iroquois cluster gene deserts. Genome Res. 15(8):1061–1072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deane EM, Cooper DW.. 1988. Immunological development in pouch young marsupials In: Tyndale-Biscoe CH, Janssens PA, editors. The developing marsupial. Berlin: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Dee CT, Nagaraju RT, Athanasiadis EI, Gray C, Fernandez del Ama L, Johnston SA, Secombes CJ, Cvejic A, Hurlstone AFL.. 2016. CD4-transgenic zebrafish reveal tissue-resident Th2- and regulatory T cell− like populations and diverse mononuclear phagocytes. J Immunol. 197(9):3520–3530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickel DE, Ypsilanti AR, Pla R, Zhu Y, Barozzi I, Mannion BJ, Khin YS, Fukuda-Yuzawa Y, Plajzer-Frick I, Pickle CS, et al. 2018. Ultraconserved enhancers are required for normal development. Cell 172(3):491–499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimitrieva S, Bucher P.. 2013. UCNEbase–a database of ultraconserved non-coding elements and genomic regulatory blocks. Nucleic Acids Res. 41(D1):D101–D109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake JA, Bird C, Nemesh J, Thomas DJ, Newton-Cheh C, Reymond A, Excoffier L, Attar H, Antonarakis SE, Dermitzakis ET, et al. 2006. Conserved noncoding sequences are selectively constrained and not mutation cold spots. Nat Genet. 38(2):223–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drewell RA, Brenton JD, Ainscough JF, Barton SC, Hilton KJ, Arney KL, Dandolo L, Surani MA.. 2000. Deletion of a silencer element disrupts H19 imprinting independently of a DNA methylation epigenetic switch. Development 127(16):3419–3428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan LG, Nair SV, Deane EM.. 2007. Molecular characterisation and expression of CD4 in two distantly related marsupials: the gray short-tailed opossum (Monodelphis domestica) and tammar wallaby (Macropus eugenii). Mol Immunol. 44(15):3641–3652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farley EK, Olson KM, Zhang W, Rokhsar DS, Levine MS.. 2016. Syntax compensates for poor binding sites to encode tissue specificity of developmental enhancers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 113(23):6508–1653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuxman Bass JI, Sahni N, Shrestha S, Garcia-Gonzalez A, Mori A, Bhat N, Yi S, Hill DE, Vidal M, Walhout AJM.. 2015. Human gene-centered transcription factor networks for enhancers and disease variants. Cell 161(3):661–673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabellini D, Green MR, Tupler R.. 2002. Inappropriate gene activation in FSHD: a repressor complex binds a chromosomal repeat deleted in dystrophic muscle. Cell 110(3):339–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabellini D, Tupler R, Green MR.. 2003. Transcriptional derepression as a cause of genetic diseases. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 13(3):239–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glassford WJ, Rebeiz M.. 2013. Assessing constraints on the path of regulatory sequence evolution. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 368(1632):20130026.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goode DK, Callaway HA, Cerda GA, Lewis KE, Elgar G.. 2011. Minor change, major difference: divergent functions of highly conserved cis-regulatory elements subsequent to whole genome duplication events. Development 138(5):879–884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon KL, Ruvinsky I.. 2012. Tempo and mode in evolution of transcriptional regulation. PLoS Genet. 8(1):e1002432.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haynes JI. 2001. The marsupial and monotreme thymus, revisited. J Zool Lond. 253(2):167–173. [Google Scholar]

- He X, He X, Dave VP, Zhang Y, Hua X, Nicolas E, Xu W, Roe BA, Kappes DJ.. 2005. The zinc finger transcription factor Th-POK regulates CD4 versus CD8 T-cell lineage commitment. Nature 433(7028):826–833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He X, Park K, Wang H, He X, Zhang Y, Hua X, Li Y, Kappes DJ.. 2008. CD4-CD8 lineage commitment is regulated by a silencer element at the ThPOK transcription-factor locus. Immunity 28(3):346–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogquist KA, Jameson SC, Heath WR, Howard JL, Bevan MJ, Carbone FR.. 1994. T cell receptor antagonist peptides induce positive selection. Cell 76(1):17–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howson LJ, Morris KM, Kobayashi T, Tovar C, Kreiss A, Papenfuss AT, Corcoran L, Belov K, Woods GM.. 2014. Identification of dendritic cells, B cell and T cell subsets in Tasmanian devil lymphoid tissue; evidence for poor immune cell infiltration into devil facial tumors. Anat Rec. 297(5):925–938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard GB, Saphire DG, Hackleman SM, Silva MV, Vandeberg JL, Stone WH.. 1991. Ontogeny of the thymus gland of a marsupial (Monodelphis domestica). Lab Anim Sci. 41(3):227–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jolma A, Yan J, Whitington T, Toivonen J, Nitta KR, Rastas P, Morgunova E, Enge M, Taipale M, Wei G, et al. 2013. DNA binding specificities of human transcription factors. Cell 152(1–2):327–339., [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katzman S, Kern AD, Bejerano G, Fewell G, Fulton L, Wilson RK, Salama SR, Haussler D.. 2007. Human genome ultraconserved elements are ultraselected. Science 317(5840):915.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyte AL, Smith KK.. 2008. Basic maintenance and breeding of the Opossum Monodelphis domestica. CSH Protoc. 2008:pdb prot5073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikuta H, Laplante M, Navratilova P, Komisarczuk AZ, Engström PG, Fredman D, Akalin A, Caccamo M, Sealy I, Howe K, et al. 2007. Genomic regulatory blocks encompass multiple neighboring genes and maintain conserved synteny in vertebrates. Genome Res. 17(5):545–555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King MC, Wilson AC.. 1975. Evolution at two levels in humans and chimpanzees. Science 188(4184):107–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolovos P, Knoch TA, Grosveld FG, Cook PR, Papantonis A.. 2012. Enhancers and silencers: an integrated and simple model for their function. Epigenet Chromatin 5(1):1.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kvon EZ, Kamneva OK, Melo US, Barozzi I, Osterwalder M, Mannion BJ, Tissieres V, Pickle CS, Plajzer-Frick I, Lee EA, et al. 2016. Progressive loss of function in a limb enhancer during snake evolution. Cell 167(3):633–642 e611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig MZ, Palsson A, Alekseeva E, Bergman CM, Nathan J, Kreitman M.. 2005. Functional evolution of a cis-regulatory module. PLoS Biol. 3(4):e93.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo ZX, Yuan CX, Meng QJ, Ji Q.. 2011. A Jurassic eutherian mammal and divergence of marsupials and placentals. Nature 476(7361):442–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maston GA, Evans SK, Green MR.. 2006. Transcriptional regulatory elements in the human genome. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 7:29–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meredith RW, Westerman M, Case JA, Springer M.. 2008. A phylogeny and timescale for marsupial evolution based on sequences for five nuclear genes. J Mammal Evol. 15(1):1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Merika M, Thanos D.. 2001. Enhanceosomes. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 11(2):205–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mousavi K, Zare H, Koulnis M, Sartorelli V.. 2014. The emerging roles of eRNAs in transcriptional regulatory networks. RNA Biol. 11(2):106–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muroi S, Naoe Y, Miyamoto C, Akiyama K, Ikawa T, Masuda K, Kawamoto H, Taniuchi I.. 2008. Cascading suppression of transcriptional silencers by ThPOK seals helper T cell fate. Nat Immunol. 9(10):1113–1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson MA, Arnason U, Spencer PB, Janke A.. 2004. Marsupial relationships and a timeline for marsupial radiation in South Gondwana. Gene 340(2):189–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson MA, Churakov G, Sommer M, Tran NV, Zemann A, Brosius J, Schmitz J.. 2010. Tracking marsupial evolution using archaic genomic retroposon insertions. PLoS Biol. 8(7):e1000436.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nobrega MA, Ovcharenko I, Afzal V, Rubin EM.. 2003. Scanning human gene deserts for long-range enhancers. Science 302(5644):413.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogbourne S, Antalis TM.. 1998. Transcriptional control and the role of silencers in transcriptional regulation in eukaryotes. Biochem J. 331(1):1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Old JM, Deane EM.. 2000. Development of the immune system and immunological protection in marsupial pouch young. Dev Comp Immunol. 24(5):445–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Old JM, Deane EM.. 2003. The detection of mature T- and B-cells during development of the lymphoid tissues of the tammar wallaby (Macropus eugenii). J Anat. 203(1):123–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panne D. 2008. The enhanceosome. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 18(2):236–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panne D, Maniatis T, Harrison SC.. 2007. An atomic model of the interferon-beta enhanceosome. Cell 129(6):1111–1123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parra ZE, Baker ML, Hathaway J, Lopez AM, Trujillo J, Sharp A, Miller RD.. 2008. Comparative genomic analysis and evolution of the T cell receptor loci in the opossum Monodelphis domestica. BMC Genomics 9:111.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parra ZE, Baker ML, Lopez AM, Trujillo J, Volpe JM, Miller RD.. 2009. TCR mu recombination and transcription relative to the conventional TCR during postnatal development in opossums. J Immunol. 182(1):154–163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parra ZE, Baker ML, Schwarz RS, Deakin JE, Lindblad-Toh K, Miller RD.. 2007. A unique T cell receptor discovered in marsupials. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 104(23):9776–9781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearse AM, Swift K.. 2006. Allograft theory: transmission of devil facial-tumour disease. Nature 439(7076):549.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennacchio LA, Ahituv N, Moses AM, Prabhakar S, Nobrega MA, Shoukry M, Minovitsky S, Dubchak I, Holt A, Lewis KD, et al. 2006. In vivo enhancer analysis of human conserved non-coding sequences. Nature 444(7118):499–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennacchio LA, Bickmore W, Dean A, Nobrega MA, Bejerano G.. 2013. Enhancers: five essential questions. Nat Rev Genet. 14(4):288–295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raff RA, Kaufman TC.. 1983. Embryos, genes, and evolution: the developmental-genetic basis of evolutionary change. New York: Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Rebeiz M, Pool JE, Kassner VA, Aquadro CF, Carroll SB.. 2009. Stepwise modification of a modular enhancer underlies adaptation in a Drosophila population. Science 326(5960):1663–1667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reece-Hoyes JS, Barutcu AR, McCord RP, Jeong JS, Jiang L, MacWilliams A, Yang X, Salehi-Ashtiani K, Hill DE, Blackshaw S, et al. 2011. Yeast one-hybrid assays for gene-centered human gene regulatory network mapping. Nat Methods 8(12):1050–1052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reece-Hoyes JS, Diallo A, Lajoie B, Kent A, Shrestha S, Kadreppa S, Pesyna C, Dekker J, Myers CL, Walhout AJ.. 2011. Enhanced yeast one-hybrid assays for high-throughput gene-centered regulatory network mapping. Nat Methods 8(12):1059–1064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reece-Hoyes JS, Pons C, Diallo A, Mori A, Shrestha S, Kadreppa S, Nelson J, Diprima S, Dricot A, Lajoie BR, et al. 2013. Extensive rewiring and complex evolutionary dynamics in a C. elegans multiparameter transcription factor network. Mol Cell 51(1):116–127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riethoven JJ. 2010. Regulatory regions in DNA: promoters, enhancers, silencers, and insulators. Methods Mol Biol. 674:33–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robert J. 2016. The immune system of amphibians In: Ratcliffe MJH, editor. Encyclopedia of immunobiology. Vol. 1 Oxford: Academic Press; p. 486–492. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers WA, Salomone JR, Tacy DJ, Camino EM, Davis KA, Rebeiz M, Williams TM.. 2013. Recurrent modification of a conserved cis-regulatory element underlies fruit fly pigmentation diversity. PLoS Genet. 9(8):e1003740.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandelin A, Bailey P, Bruce S, Engstrom PG, Klos JM, Wasserman WW, Ericson J, Lenhard B.. 2004. Arrays of ultraconserved non-coding regions span the loci of key developmental genes in vertebrate genomes. BMC Genomics 5(1):99.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawada S, Scarborough JD, Killeen N, Littman DR.. 1994. A lineage-specific transcriptional silencer regulates CD4 gene expression during T lymphocyte development. Cell 77(6):917–929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenfelder S, Paro R.. 2004. Drosophila Su(Hw) regulates an evolutionarily conserved silencer from the mouse H19 imprinting control region. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 69:47–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Setoguchi R, Tachibana M, Naoe Y, Muroi S, Akiyama K, Tezuka C, Okuda T, Taniuchi I.. 2008. Repression of the transcription factor Th-POK by Runx complexes in cytotoxic T cell development. Science 319(5864):822–825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shlyueva D, Stampfel G, Stark A.. 2014. Transcriptional enhancers: from properties to genome-wide predictions. Nat Rev Genet. 15(4):272–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siepel A, Bejerano G, Pedersen JS, Hinrichs AS, Hou M, Rosenbloom K, Clawson H, Spieth J, Hillier LW, Richards S, et al. 2005. Evolutionarily conserved elements in vertebrate, insect, worm, and yeast genomes. Genome Res. 15(8):1034–1050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer A, Adoro S, Park JH.. 2008. Lineage fate and intense debate: myths, models and mechanisms of CD4- versus CD8-lineage choice. Nat Rev Immunol. 8(10):788–801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siu G, Wurster AL, Duncan DD, Soliman TM, Hedrick SM.. 1994. A transcriptional silencer controls the developmental expression of the CD4 gene. EMBO J. 13(15):3570–3579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somamoto T, Koppang EO, Fischer U.. 2014. Antiviral functions of CD8(+) cytotoxic T cells in teleost fish. Dev Comp Immunol. 43(2):197–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sparks EE, Drapek C, Gaudinier A, Li S, Ansariola M, Shen N, Hennacy JH, Zhang J, Turco G, Petricka JJ, et al. 2016. Establishment of expression in the SHORTROOT-SCARECROW transcriptional cascade through opposing activities of both activators and repressors. Dev Cell 39(5):585–596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitz F, Furlong EE.. 2012. Transcription factors: from enhancer binding to developmental control. Nat Rev Genet. 13(9):613–626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thanos D, Maniatis T.. 1995. Virus induction of human IFN beta gene expression requires the assembly of an enhanceosome. Cell 83(7):1091–1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toda H, Saito Y, Koike T, Takizawa F, Araki K, Yabu T, Somamoto T, Suetake H, Suzuki Y, Ototake M, et al. 2011. Conservation of characteristics and functions of CD4 positive lymphocytes in a teleost fish. Dev Comp Immunol. 35(6):650–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villar D, Berthelot C, Aldridge S, Rayner TF, Lukk M, Pignatelli M, Park TJ, Deaville R, Erichsen JT, Jasinska AJ, et al. 2015. Enhancer evolution across 20 mammalian species. Cell 160(3):554–566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walhout AJ. 2006. Unraveling transcription regulatory networks by protein-DNA and protein-protein interaction mapping. Genome Res. 16(12):1445–1454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weirauch MT, Hughes TR.. 2010. Conserved expression without conserved regulatory sequence: the more things change, the more they stay the same. Trends Genet. 26(2):66–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong ES, Papenfuss AT, Belov K.. 2011. Immunome database for marsupials and monotremes. BMC Immunol. 12:48.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wray GA, Hahn MW, Abouheif E, Balhoff JP, Pizer M, Rockman MV, Romano LA.. 2003. The evolution of transcriptional regulation in eukaryotes. Mol Biol Evol. 20(9):1377–1419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yadav M. 1973. The presence of the cervical and thoracic thymus lobes in marsupials. Aust J Zool. 21(3):285–301. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon S, Mitra S, Wyse C, Alnabulsi A, Zou J, Weerdenburg EM, van der Sar AM, Wang D, Secombes CJ, Bird S.. 2015. First demonstration of antigen induced cytokine expression by CD4-1+ lymphocytes in a Poikilotherm: studies in Zebrafish (Danio rerio). PLoS One 10(6):e0126378.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.