Abstract

Objectives

Shwachman-Diamond syndrome (SDS) is a rare autosomal recessive disorder. Its predominant manifestations include exocrine pancreatic insufficiency, bone marrow failure and skeletal abnormalities. Patients frequently present failure to thrive and susceptibility to short stature. Average birth weight is at the 25th percentile; by the first birthday, >50% of patients drop below the third percentile for height and weight.

The study aims at estimating the growth charts for patients affected by SDS in order to give a reference tool helpful for medical care and growth surveillance through the first 8 years of patient’s life.

Setting and participants

This retrospective observational study includes 106 patients (64 M) with available information from birth to 8 years, selected among the 122 patients included in the Italian National Registry of SDS and born between 1975 and 2016. Gender, birth date and auxological parameters at repeated assessment times were collected. The General Additive Model for Location Scale and Shape method was applied to build the growth charts. A set of different distributions was used, and the more appropriate were selected in accordance with the smallest Akaike information criterion.

Results

A total of 408 measurements was collected and analysed. The median number of observations per patient amounted to 3, range 1–11. In accordance with the methods described, specific SDS growth charts were built for weight, height and body mass index (BMI), separately for boys and girls.

The 50th and 3rd percentiles of weight and height of the healthy population (WHO standard references) respectively correspond to the 97th and 50th percentiles of the SDS population (SDS specific growth charts), while the difference is less evident for the BMI.

Conclusions

Specific SDS growth charts obtained through our analysis enable a more appropriate classification of patients based on auxological parameters, representing a useful reference tool for evaluating their growth during childhood.

Keywords: Shwachman–diamond syndrome, growth charts, genetics

Strengths and limitations of this study.

These growth charts represent the first set of normative curves for children with Shwachman-Diamond syndrome (SDS) 0 to 8 years old.

The 50th and 3rd percentiles of weight and height of the healthy population respectively correspond to the 97th and 50th percentiles of the SDS population.

These charts should be principally used to compare the growth between SDS subjects of the same age and sex and also to recognise patients to investigate for growth hormone deficiency.

The data used for the growth charts do not represent the natural development of the disease, but rather the growth development of SDS subjects receiving medical care.

The present growth charts should be used with caution when studying patients with SDS of other ethnic backgrounds, as they show an accurate picture of the Italian SDS population.

Introduction

Shwachman-Diamond syndrome (SDS) (OMIM 260400) is a rare autosomal recessive disorder first described in 1964,1 characterised by exocrine pancreas insufficiency, bone marrow failure and bone malformations.2–5 Failure to thrive, susceptibility to infections and short stature are frequently observed in patients with SDS as well.1–4 6

Pancreatic insufficiency early arises and is characterised by replacement of exocrine components with fatty tissue, but preserved islets of Langerhans and ductal architecture. Pancreatic function spontaneously improves over time in almost 50% of patients.2 4 7–9

Almost the totality of patients present persistent or intermittent neutropaenia.1 2 8–11 Bone marrow biopsy reveals a hypoplastic ‘marrow’ with varying degrees of fat infiltration.2 11 Up to 15%–20% of patients develop myelodysplastic syndrome, with high risk of acute myeloid leukaemia progression.12–15

In 2002, the gene (SBDS) involved in the syndrome was identified on chromosome 7q11,16 although mutations in the DNAJC21 gene have also been associated to an SDS phenotype, as well as, possibly, mutations of EFL1 and SRP54 genes.17–19 SBDS is widely expressed in mammalian tissue. In fact, other organs such as teeth and oral cavity, liver, heart, kidneys and skin may be involved.5 7 8

Currently, almost 10% of patients with SDS with clinical features of SDS have lacked SBDS mutations.16 20 However, the negative genetic test should not exclude the diagnosis. An accurate clinical evaluation is important in order to diagnose the presence of the syndrome.

Cognitive impairment has been noted in the majority of these patients, although with intragroup variability21–23; this has a serious impact on the patient, limiting independence and quality of life.23 Neuroimaging studies24–26 reported diffuse brain alterations in the brain structure and connectivity.

Several clinical studies reported failure to thrive associated with malnutrition. This is a common feature in the early stage of life, in particular prior to diagnosis. Growth failure is mainly due to inadequate nutrient intake in the presence or in the absence of feeding difficulties, pancreatic insufficiency and recurrent infections.1 2 4 8 27 The average weight at birth is at the 25th percentile, and over half of the patients drop below the 3rd percentile for both height and weight by the first birthday. After diagnosis and the start of an appropriate therapy, growth rate is restored to normal level in most of the children with SDS, even though it consistently remains below the third percentile for height and weight.2 4 9 27 These alterations are not related to a pancreatic insufficiency or an inappropriate caloric intake, but seem to be directly linked to biallelic mutations of the SBDS gene, and the growth of these patients differs from that of healthy children.

To date, there are no specific SDS growth charts available unlike other disorders with marked growth retardation such as Down syndrome, Turner syndrome, Ellis-Van Creveld syndrome and achondroplasia.28–31 Indeed, disease-specific charts are a helpful tool in medical care, monitoring growth more accurately, and for research.

The aim of this retrospective multicentre observational study is to develop the growth chart for patients affected by SDS in order to provide a reference tool to monitor the growth of children with this disease throughout childhood.

Method

This study includes patients who are part of the Italian National Registry of SDS whose height, weight and main demographic characteristic were available in their first 8 years of life. In the Registry, all 122 patients have an SDS diagnosis confirmed by genetic analysis. For each subject, the following characteristics were collected: gender, birth date, height, weight, assessment date and available clinic information. Measurements were recorded in accordance with the standard criteria by age period. A total of 645 observations on 122 patients was recorded, but data beyond 8 years of age was not included in the analysis owing to its being available for only 16 patients and at limited data points; thus, 408 observations on 106 patients with assessments in their first 8 years of life were analysed.

The primary endpoint was to estimate percentiles for height, weight and body mass index (BMI) for boys and girls.

The protocol was approved. All patients signed an informed consent to be included in the Registry.

Patient and public involvement

Patients were not involved in the design, recruitment and conduct of this study.

Data were initially prepared using the statistical software SAS and then analysed by the software R for growth curve estimation.32 A 3-month window was used for each of the three anthropomorphic measures; in case of multiple assessments, the average of the values available inside the window was considered. Growth curves for weight, height and BMI from birth to 8 years were constructed, each with 3rd, 25th, 50th, 75th and 97th centiles for age. Data from male and female individuals were analysed separately.

Normative data for growth parameters were obtained from tables published by Cacciari et al.33 The Italian normative data were limited to 2–8 years, thus WHO data were used for ages 0–2.34 To model the growth charts, the General Additive Model for Location Scale and Shape package for the R statistical programme was used. This tool enables all the parameters of the distribution of the response variable to be modelled as linear/non-linear or smooth functions of the explanatory variables.35–37

The distribution of height, weight and BMI was modelled by the use of four parameters representing location, scale, skewness and kurtosis, using cubic penalised smoothing lines. A set of different distributions was used, and the more appropriate were selected in accordance with the criterion of the smallest Akaike information criterion. Worm plots and q-q plots were used for the analysis of residuals.

With a sample size of 60 patients, the 50th, 25th/75th and 3rd/97th centiles could be estimated reaching an SE of about 0.8, 0.9 and 1.3, respectively.

Results

A total of 106 patients (64 boys and 42 girls) were considered eligible for the analysis, with a total of 408 measurements collected from 1975 to 2016, with a median number of three observations per patient, range 1–11 (table 1). All patients were Caucasian and of Italian origin, with a median age at diagnosis of 13.8 months, range 0 days–35.6 years. The median gestational age was 39 weeks, range 29–42, and the median weight at birth was 2.8 kg (0.85–4.2). Pancreatic insufficiency was observed in 91 patients (86%), all of them were on treatment with pancreatic enzymes. Six patients were treated with growth hormone (GH), five after their first 8 years of life and one at age 7.5. Twelve patients out of 106 underwent haematopoietic stem cell transplantation, 8 out of 12 under 8 years of age.

Table 1.

Number of patients and assessments

| Age (years) | F | M | Total | |

| (1) Variable | Number of patients | |||

| 0–2 | 36 | 58 | 94 | |

| 3–4 | 23 | 37 | 60 | |

| 5–6 | 20 | 27 | 47 | |

| 7–8 | 18 | 27 | 45 | |

| (2) Weight | Number of assessments | |||

| 0–2 | 91 | 141 | 232 | |

| 3–4 | 27 | 44 | 71 | |

| 5–6 | 29 | 41 | 70 | |

| 7–8 | 17 | 18 | 35 | |

| Total | 164 | 244 | 408 | |

| (3) Height | Number of assessments | |||

| 0–2 | 77 | 128 | 205 | |

| 3–4 | 27 | 42 | 69 | |

| 5–6 | 28 | 41 | 69 | |

| 7–8 | 16 | 18 | 34 | |

| Total | 148 | 229 | 377 | |

| (4) Body mass index | Number of assessments | |||

| 0–2 | 77 | 128 | 205 | |

| 3–4 | 27 | 42 | 69 | |

| 5–6 | 28 | 41 | 69 | |

| 7–8 | 16 | 18 | 34 | |

| Total | 148 | 229 | 377 | |

(1) for each age class, the number of patients with available assessments is reported, separately for boys and girls; (2), (3) and (4) for each age class, the number of assessments for weight, height and BMI, respectively, is reported for boys and girls.

F, female; M, male.

The main patient characteristics and mutations are reported in table 2 and table 3.

Table 2.

Main demographic and clinical characteristics of patients

| Variables | N (%) |

| Total | 106 |

| Gender | |

| Male | 64 (60) |

| Female | 42 (40) |

| Age at diagnosis (months) | |

| Median (range) | 13.8 months (0–35.6 years) |

| Gestational age (weeks) | |

| Median (range) | 39 (29–42) |

| Pancreatic status | |

| Pancreatic sufficiency | 15 (14) |

| Pancreatic insufficiency | 91 (86) |

| Heart problems | |

| No | 99 (93) |

| Yes | 7 (7) |

| Bone lesions at diagnosis | |

| No | 59 (56) |

| Yes | 47 (44) |

| Bone lesions during the first 8 years | |

| No | 74 (70) |

| Yes | 32 (30) |

| GH* | |

| No | 100 (94) |

| Yes | 6 (6) |

*In five cases after the first 8 years of life, in one case at 7.5 years.

GH, growth hormone.

Table 3.

Mutations of patients with Shwachman-Diamond syndrome

| Mutations | N | % | |

| 258+2T>C | 183-184TA>CT | 61 | 57.5 |

| 258+2T>C | 183-184TA>CT+258+2T>C | 16 | 15.1 |

| 258+2T>C | 258+2T>C | 9 | 8.5 |

| 258+2T>C | c.258+533_459+403del | 4 | 3.8 |

| 258+2T>C | 101A>T | 1 | 0.9 |

| 258+2T>C | 107delT | 1 | 0.9 |

| 258+2T>C | 187G>T | 1 | 0.9 |

| 258+2T>C | 212C>T | 1 | 0.9 |

| 258+2T>C | 289-292del | 1 | 0.9 |

| 258+2T>C | 300delAC | 1 | 0.9 |

| 258+2T>C | 307-308delCA | 1 | 0.9 |

| 258+2T>C | 352A>G | 1 | 0.9 |

| 258+2T>C | 356G>A | 1 | 0.9 |

| 258+2T>C | 624+1G>C | 1 | 0.9 |

| 258+2T>C | 92-93GC>AG | 1 | 0.9 |

| 258+2T>C | G63C | 1 | 0.9 |

| 258+2T>C | IVS1-71del83bp | 1 | 0.9 |

| 258+2T>C | R218X | 1 | 0.9 |

| 258+2T>C | Y32C | 1 | 0.9 |

| 523C>T | 523C>T | 1 | 0.9 |

In accordance with the methods described, specific SDS growth charts were built for weight, height and BMI, separately for boys and girls. Each subject had the same number of observations for each growth parameter included in the database.

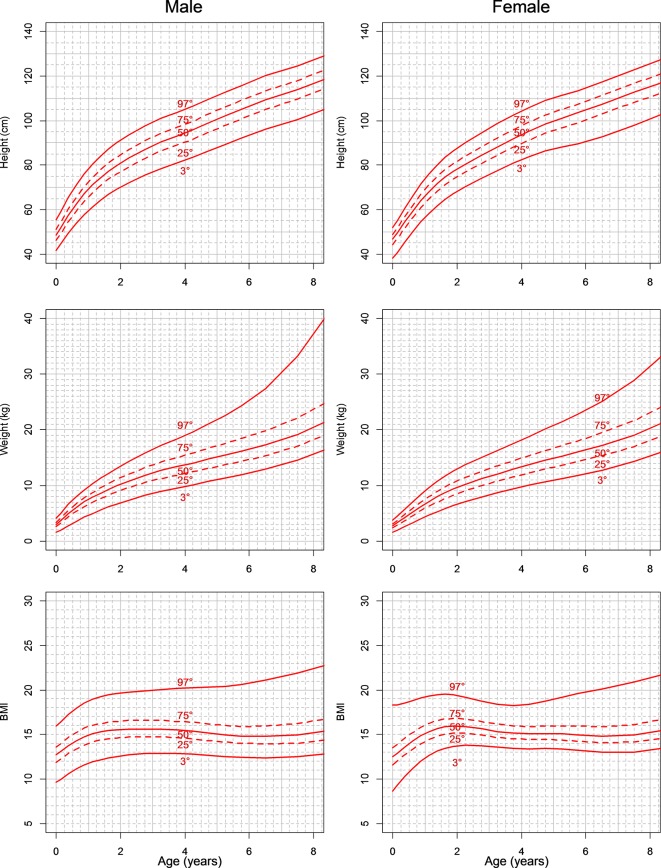

Figure 1 shows a growth chart for height (A and B), weight (C and D) and BMI (E and F) for boys and girls. Table 4 shows the 3rd, 25th, 50th, 75th and 97th centiles: the centiles are estimated every 3 months from birth to 2 years, every 6 months from 2 to 6 years and once a year from 6 to 8 years.

Figure 1.

Growth chart for height (A and B), weight (C and D) and body mass index (BMI) (E and F) for boys and girls (patients with Shwachman-Diamond syndrome). Curves for 3rd, 25th, 50th, 75th and 97th are reported in each graph.

Table 4.

Third, 25th, 50th, 75th and 97th are reported for patients with SDS from birth to 8 years

| Age | Male | Female | ||||||||

| C3 | C25 | C50 | C75 | C97 | C3 | C25 | C50 | C75 | C97 | |

| (1) Centiles for height | ||||||||||

| 0.00 | 41.8 | 46.2 | 48.6 | 51.1 | 55.5 | 38.1 | 44.3 | 46.8 | 48.8 | 51.8 |

| 0.25 | 47.0 | 51.9 | 54.7 | 57.4 | 62.3 | 43.0 | 49.3 | 52.0 | 54.3 | 57.7 |

| 0.50 | 51.7 | 57.2 | 60.2 | 63.1 | 68.4 | 47.8 | 54.2 | 57.0 | 59.5 | 63.4 |

| 0.75 | 55.9 | 61.8 | 65.0 | 68.1 | 73.7 | 52.3 | 58.7 | 61.8 | 64.5 | 68.8 |

| 1.00 | 59.6 | 65.8 | 69.2 | 72.5 | 78.4 | 56.5 | 62.9 | 66.1 | 69.0 | 73.8 |

| 1.25 | 62.8 | 69.3 | 72.8 | 76.3 | 82.3 | 60.2 | 66.6 | 69.9 | 73.0 | 78.2 |

| 1.50 | 65.5 | 72.3 | 75.9 | 79.5 | 85.7 | 63.3 | 69.8 | 73.2 | 76.5 | 81.9 |

| 1.75 | 68.0 | 74.9 | 78.7 | 82.3 | 88.7 | 66.0 | 72.5 | 76.0 | 79.3 | 85.1 |

| 2.00 | 70.1 | 77.2 | 81.0 | 84.8 | 91.2 | 68.3 | 74.8 | 78.4 | 81.8 | 87.8 |

| 2.50 | 73.8 | 81.2 | 85.2 | 89.0 | 95.6 | 72.2 | 78.8 | 82.4 | 86.0 | 92.4 |

| 3.00 | 77.1 | 84.8 | 88.8 | 92.7 | 99.4 | 75.8 | 82.6 | 86.3 | 90.0 | 96.6 |

| 3.50 | 79.7 | 87.6 | 91.7 | 95.6 | 102.3 | 79.2 | 86.2 | 90.1 | 93.9 | 100.6 |

| 4.00 | 82.1 | 90.1 | 94.3 | 98.2 | 104.9 | 82.3 | 89.7 | 93.7 | 97.5 | 104.3 |

| 4.50 | 84.9 | 93.1 | 97.3 | 101.3 | 108.0 | 85.1 | 92.9 | 97.0 | 100.9 | 107.6 |

| 5.00 | 87.9 | 96.3 | 100.5 | 104.6 | 111.2 | 87.2 | 95.7 | 99.9 | 103.8 | 110.2 |

| 5.50 | 90.6 | 99.2 | 103.5 | 107.6 | 114.2 | 88.8 | 98.0 | 102.3 | 106.2 | 112.4 |

| 6.00 | 93.4 | 102.1 | 106.5 | 110.6 | 117.3 | 90.5 | 100.4 | 104.8 | 108.7 | 114.7 |

| 7.00 | 98.3 | 107.3 | 111.7 | 115.8 | 122.4 | 95.1 | 105.6 | 110.1 | 114.1 | 120.1 |

| 8.00 | 103.0 | 112.2 | 116.6 | 120.7 | 127.3 | 100.7 | 110.6 | 115.1 | 119.1 | 125.5 |

| (2) Centiles for weight | ||||||||||

| 0.00 | 1.5 | 2.6 | 2.9 | 3.3 | 4.0 | 1.6 | 2.3 | 2.7 | 3.1 | 3.7 |

| 0.25 | 2.4 | 3.8 | 4.3 | 4.8 | 5.8 | 2.2 | 3.2 | 3.7 | 4.2 | 5.1 |

| 0.50 | 3.2 | 4.9 | 5.5 | 6.1 | 7.3 | 2.9 | 4.1 | 4.7 | 5.4 | 6.4 |

| 0.75 | 3.9 | 5.8 | 6.6 | 7.3 | 8.6 | 3.6 | 5.0 | 5.7 | 6.5 | 7.7 |

| 1.00 | 4.6 | 6.6 | 7.5 | 8.3 | 9.7 | 4.3 | 5.8 | 6.7 | 7.5 | 9.0 |

| 1.25 | 5.2 | 7.3 | 8.3 | 9.2 | 10.8 | 5.0 | 6.6 | 7.6 | 8.5 | 10.2 |

| 1.50 | 5.8 | 7.9 | 9.0 | 10.0 | 11.7 | 5.6 | 7.3 | 8.3 | 9.4 | 11.2 |

| 1.75 | 6.4 | 8.5 | 9.6 | 10.7 | 12.6 | 6.1 | 8.0 | 9.0 | 10.1 | 12.1 |

| 2.00 | 6.9 | 9.0 | 10.2 | 11.4 | 13.5 | 6.6 | 8.6 | 9.7 | 10.8 | 13.0 |

| 2.50 | 7.8 | 10.0 | 11.3 | 12.6 | 15.1 | 7.5 | 9.5 | 10.7 | 12.0 | 14.4 |

| 3.00 | 8.6 | 10.9 | 12.3 | 13.7 | 16.5 | 8.3 | 10.4 | 11.6 | 13.0 | 15.6 |

| 3.50 | 9.2 | 11.5 | 13.0 | 14.6 | 17.8 | 9.0 | 11.1 | 12.5 | 13.9 | 16.9 |

| 4.00 | 9.8 | 12.1 | 13.7 | 15.4 | 19.0 | 9.7 | 11.9 | 13.3 | 14.9 | 18.1 |

| 4.50 | 10.4 | 12.8 | 14.4 | 16.2 | 20.3 | 10.3 | 12.6 | 14.1 | 15.8 | 19.5 |

| 5.00 | 11.0 | 13.4 | 15.1 | 17.1 | 21.8 | 10.9 | 13.3 | 14.9 | 16.7 | 20.8 |

| 5.50 | 11.6 | 14.0 | 15.8 | 17.9 | 23.4 | 11.5 | 13.9 | 15.6 | 17.6 | 22.1 |

| 6.00 | 12.3 | 14.7 | 16.5 | 18.8 | 25.2 | 12.1 | 14.6 | 16.4 | 18.5 | 23.5 |

| 7.00 | 13.6 | 16.1 | 18.1 | 20.9 | 30.0 | 13.4 | 16.1 | 18.0 | 20.5 | 26.8 |

| 8.00 | 15.5 | 18.1 | 20.3 | 23.6 | 37.2 | 15.2 | 18.0 | 20.2 | 23.0 | 31.2 |

| (3) Centiles for body mass index (BMI) | ||||||||||

| 0.00 | 9.6 | 11.9 | 12.7 | 13.6 | 16.0 | 8.7 | 11.6 | 12.5 | 13.5 | 18.3 |

| 0.25 | 10.3 | 12.5 | 13.4 | 14.3 | 16.9 | 9.8 | 12.3 | 13.3 | 14.2 | 18.4 |

| 0.50 | 10.9 | 13.1 | 14.0 | 15.0 | 17.6 | 10.8 | 13.1 | 14.0 | 14.9 | 18.7 |

| 0.75 | 11.3 | 13.6 | 14.5 | 15.5 | 18.3 | 11.6 | 13.7 | 14.6 | 15.6 | 19.0 |

| 1.00 | 11.7 | 14.0 | 14.9 | 15.9 | 18.8 | 12.3 | 14.2 | 15.1 | 16.1 | 19.2 |

| 1.25 | 12.0 | 14.3 | 15.2 | 16.2 | 19.1 | 12.9 | 14.6 | 15.5 | 16.4 | 19.4 |

| 1.50 | 12.3 | 14.4 | 15.4 | 16.3 | 19.4 | 13.3 | 14.9 | 15.8 | 16.7 | 19.5 |

| 1.75 | 12.4 | 14.6 | 15.5 | 16.4 | 19.5 | 13.6 | 15.1 | 15.9 | 16.8 | 19.5 |

| 2.00 | 12.6 | 14.6 | 15.5 | 16.5 | 19.7 | 13.8 | 15.2 | 16.0 | 16.8 | 19.4 |

| 2.50 | 12.8 | 14.7 | 15.6 | 16.6 | 19.9 | 13.8 | 15.1 | 15.8 | 16.6 | 19.0 |

| 3.00 | 12.9 | 14.8 | 15.6 | 16.6 | 20.0 | 13.6 | 14.8 | 15.5 | 16.3 | 18.5 |

| 3.50 | 12.9 | 14.7 | 15.6 | 16.5 | 20.1 | 13.5 | 14.6 | 15.2 | 16.0 | 18.3 |

| 4.00 | 12.8 | 14.6 | 15.4 | 16.4 | 20.2 | 13.4 | 14.4 | 15.1 | 15.9 | 18.3 |

| 4.50 | 12.7 | 14.4 | 15.3 | 16.3 | 20.3 | 13.4 | 14.4 | 15.1 | 15.9 | 18.5 |

| 5.00 | 12.6 | 14.2 | 15.1 | 16.1 | 20.4 | 13.4 | 14.4 | 15.1 | 16.0 | 19.0 |

| 5.50 | 12.5 | 14.0 | 14.9 | 16.0 | 20.5 | 13.3 | 14.3 | 15.0 | 16.0 | 19.4 |

| 6.00 | 12.4 | 14.0 | 14.8 | 15.9 | 20.7 | 13.1 | 14.2 | 14.9 | 15.9 | 19.8 |

| 7.00 | 12.4 | 14.0 | 14.9 | 16.1 | 21.5 | 13.0 | 14.0 | 14.8 | 15.9 | 20.5 |

| 8.00 | 12.7 | 14.2 | 15.2 | 16.5 | 22.4 | 13.2 | 14.4 | 15.2 | 16.4 | 21.3 |

The estimates are reported every 3 months from birth to 2 years, every 6 months from 2 to 6 years and once a year from 6 to 8 years.

SDS, Shwachman-Diamond syndrome.

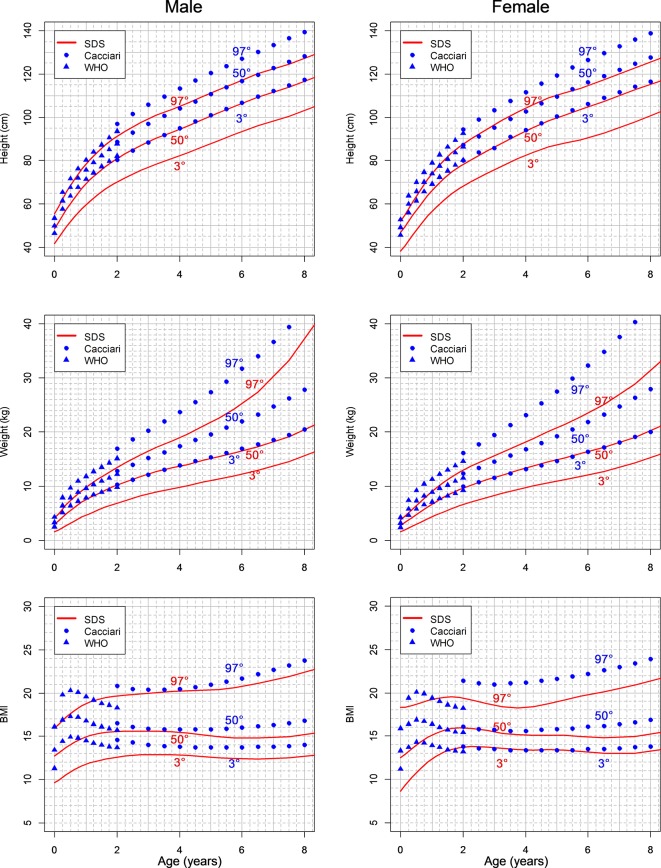

In figure 2, the estimated SDS growth charts are shown together with Italian reference curves.

Figure 2.

Estimated Shwachman-Diamond syndrome (SDS) growth charts compared with reference Italian curves. The values of 97th and 50th centiles for height and weight of patients with SDS are located on the 50th and 3rd centiles of the reference population. The difference is less evident for the body mass index (BMI) centiles.

Compared with typically developing individuals (standard population), the values of the 97th and 50th centiles for height and weight of patients with SDS are located on the 50th and third centiles, respectively. At 8 years, the 50th centile for height in patients with SDS corresponds to the 3rd centile and to the −2 SD value in the healthy population. The difference is less evident for the BMI centiles, meaning that the growth retardation is harmonic.

Discussion

SDS is a rare disease without a well-defined prevalence. Severe growth retardation (particularly in length/height) is one of its typical features, which can be alleged to be linked to the genetic cause of the disease.

At present, no growth charts have been validated for SDS; the charts we show here represent the first set of normative curves for children with SDS 0–8 years. As in healthy children, specific charts for SDS are important tools in monitoring treatment efficacy and for routine medical follow-up.

In this study, we used data from all children included in the Italian SDS registry with available assessments from birth to 8 years. All patients had SDS diagnosis confirmed by genetic mutations on both alleles, although up to 10% of subjects with SDS diagnosis described in the literature do not present mutations of the SBDS gene. In this way, we tried to reduce bias in our data set.

In spite of the rarity of the disease, we had the possibility to generate separate charts for boys and girls until the age of 8. When compared with normal (regular) growth charts, the SDS charts do not differ in form for this period of age. The 50th percentile of SDS charts for weight and height is positioned on the 3rd percentile of regular charts, both for boys and girls. The low percentile at birth for length and weight indicates that prenatal retardation occurs, then continuing in the postnatal period.

BMI curves are similar both for normal and SDS population, indicating that the weight and height trend is harmonic also in SDS. These results as a whole suggest these growth curves are influenced by the genetic defect rather than malabsorption/malnutrition or inherited factors.

The SDS-specific growth charts can be used in managing problems related to growth, and may be useful to recognise patients who need investigations for GH deficiency and for the possibility of specific treatment. These specific growth charts are also extremely useful to address nutritional counselling. The parents of patients with SDS regularly ask for the best diet to increase the growth of their children. Sometimes, an overfeeding behaviour has been reported with the aim of influencing height. This erroneous interpretation of growth problems in SDS may cause obesity and negative consequences on the skeletal apparatus.

Moreover, since there has been no growth chart available for patients with SDS until now, the growth charts developed in this study provide a significant impact in understanding physical trends in these subjects.

Given the small number of observations beyond 8 years, the growth charts were curtailed at age 8.

Several associated manifestations of the syndrome, such as heart, renal or skeletal alteration, could theoretically influence the growth of the patients. In our set, comorbidity risk factors able to influence growth retardation were not identified. In any case, given the rarity of the disease and the consequent small sample size, children with medical problems were not excluded, as already done in other similar works.38 39

It is also well known that SDS subjects may be recognised by the presence of typical clinical features, but variable penetrance and expressivity are common, which, together with the rarity of these patients, makes a correlation genotype-phenotype difficult.

A few limitations in our study are to be taken into account; one is that the data used for the growth charts do not represent the natural development of the disease, but rather the growth development of SDS subjects receiving medical care. We are aware that the data used in constructing growth charts should ideally come from prospective longitudinal studies on large groups; however, when considering rare syndromes, this approach cannot be used.

In Italy, as well as in many Northern European countries, the secular trend has slowed down or even reached a plateau since the 1980s/1990s. Since only less than 3% of measurements included in this study were collected before 1980, no correction for the secular trend was considered.40 41

Furthermore, the present curves do not quite grasp the age of puberty, and definitive information on what affects the final height could not be obtained. In any case, the literature includes some patients with SDS older than 18 with percentiles remaining in the low average or below the third percentile for both weight and height,3 4 indicating that the growth spurt does not lead to a substantial change in the trend of growth.

The number of older patients at the moment is small; therefore, the charts may not be sufficiently reliable at the ages over 8 years. This is a typical limitation in presence of small numbers of patients, and is shared by other reference charts for rare diseases.

The present growth charts can be used to compare the growth of SDS individual (height, weight, BMI) and the general population, and also to compare the growth of an individual child with that of peers of the same age and sex with the syndrome.

SDS is a worldwide disease with patients diagnosed in every part of the world; the present growth charts should be used with caution when studying individuals with SDS of other ethnic backgrounds; as presented, the curves show an accurate picture of the Italian SDS population.

Future efforts will aim at collecting more data to improve knowledge on the syndrome and construct growth charts until 18 years of age. These tools would enable the gathering of more information on SDS, especially the influence of pubertal development on growth, as only sporadic data on this point are currently available.

Finally, when clinical trials aimed at assessing therapies for SDS basic defect are possible, similarly to other rare diseases,42 growth chart comparison in treated versus untreated SDS populations could be a relevant endpoint.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Contributors: Conception and design: MC, SP, GT. Provision of study materials or patients: MC, SP, EP, SC, EM, EN, CD. Collection and assembly of data: MC, EP. Data analysis: GT, AM. Manuscript writing and final approval of manuscript: All authors.

Funding: The study was partially supported by a grant from the Italian Association for Shwachman Syndrome (AISS).

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Local Ethics Committee (CE n 1944).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: All the available data were included in the analysis. The data may be available by contacting the authors.

Collaborators: Maura Ambroni (Ospedale M. Bufalini, Cesena, Italy); Maurizio Caniglia (Ospedale Santa Maria della Misericordia, Perugia, Italy); Maria Elena Cantarini (Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria Sant’Orsola-Malpighi, Bologna, Italy); Paola Corti (San Gerardo Hospital, Monza, Italy); P Farrugia (A.R.N.A.S. Civico Hospital, Palermo, Italy); Maria Rita Frau (Azienda Sanitaria ASL Nuoro, Nuoro, Italy); Maurizio Fuoti (Spedali Civili Brescia, Italy); Giuseppe Indolfi (Meyer Children’s University Hospital, Firenze, Italy); Saverio Ladogana ("Casa Sollievo della Sofferenza" Hospital, IRCCS, San Giovanni Rotondo, Italy); V Lucidi ("Bambino Gesù" Children’s Hospital, IRCCS, Roma, Italy); Sofia Maria Rosaria Matarese (Università degli Studi della Campania "Luigi Vanvitelli", Napoli, Italy); Giuseppe Menna (Santobono-Pausilipon Hospital, Napoli, Italy); E Montemitro ("Bambino Gesù" Children’s Hospital, IRCCS, Roma, Italy); Margherita Nardi (University Hospital of Pisa, Italy); C Nasi (Azienda Sanitaria ASL 17, Savigliano, Italy); Agostino Nocerino (Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria "Santa Maria della Misericordia," Udine, Italy); Roberta Pericoli (Ospedale Infermi - Azienda USL Rimini, Italy); V Raia, U Ramenghi (University of Torino, Italy); L Sainati (Department of Women’s and Children’s Health, University of Padova, Italy); Fabio Tucci (Ospedale Pediatrico Meyer, Firenze, Italy); Federico Verzegnassi ("Burlo Garofolo" Hospital, Trieste, Italy); Marco Zecca (Fondazione IRCCS Policlinico San Matteo, Pavia, Italy); Andrea Zucchini (Santa Maria delle Croci Hospital, Ravenna, Italy).

Contributor Information

Collaborators: Maura Ambroni, Maurizio Caniglia, Maria Elena Cantarini, Paola Corti, P Farrugia, Maria Rita Frau, Maurizio Fuoti, Giuseppe Indolfi, Saverio Ladogana, V Lucidi, Sofia Maria Rosaria matarese, Giuseppe Menna, E Montemitro, Margherita Nardi, C Nasi, Agostino Nocerino, Roberta Pericoli, V Raia, U Ramenghi, L Sainati, Fabio Tucci, Federico Verzegnassi, Marco Zecca, and Andrea Zucchini

References

- 1. Shwachman H, Diamond LK, Oski FA, et al. The syndrome of pancreatic insufficiency and bone marrow dysfunction. J Pediatr 1964;65:645–63. 10.1016/S0022-3476(64)80150-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Aggett PJ, Cavanagh NP, Matthew DJ, et al. Shwachman’s syndrome. A review of 21 cases. Arch Dis Child 1980;55:331–47. 10.1136/adc.55.5.331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mack DR, Forstner GG, Wilschanski M, et al. Shwachman syndrome: exocrine pancreatic dysfunction and variable phenotypic expression. Gastroenterology 1996;111:1593–602. 10.1016/S0016-5085(96)70022-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cipolli M, D’Orazio C, Delmarco A, et al. Shwachman’s syndrome: pathomorphosis and long-term outcome. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 1999;29:265–72. 10.1097/00005176-199909000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mäkitie O, Ellis L, Durie PR, et al. Skeletal phenotype in patients with Shwachman-Diamond syndrome and mutations in SBDS. Clin Genet 2004;65:101–12. 10.1111/j.0009-9163.2004.00198.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dall’oca C, Bondi M, Merlini M, et al. Shwachman-Diamond syndrome. Musculoskelet Surg 2012;96:81–8. 10.1007/s12306-011-0174-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mack DR. Shwachman-Diamond syndrome. J Pediatr 2002;141:164–5. 10.1067/mpd.2002.126918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cipolli M. Shwachman-Diamond syndrome: clinical phenotypes. Pancreatology 2001;1:543–8. 10.1159/000055858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rothbaum R, Perrault J, Vlachos A, et al. Shwachman-Diamond syndrome: report from an international conference. J Pediatr 2002;141:266–70. 10.1067/mpd.2002.125850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Burroughs L, Woolfrey A, Shimamura A. Shwachman-Diamond syndrome: a review of the clinical presentation, molecular pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am 2009;23:233–48. 10.1016/j.hoc.2009.01.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dror Y. Impaired ability of bone marrow stroma from patients with Shwachman–Diamond syndrome to support hematopoiesis. Brit J Haematol 1998;102:161 Abs P-0638. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dror Y, Squire J, Durie P, et al. Malignant myeloid transformation with isochromosome 7q in Shwachman-Diamond syndrome. Leukemia 1998;12:1591–5. 10.1038/sj.leu.2401147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Maserati E, Minelli A, Pressato B, et al. Shwachman syndrome as mutator phenotype responsible for myeloid dysplasia/neoplasia through karyotype instability and chromosomes 7 and 20 anomalies. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2006;45:375–82. 10.1002/gcc.20301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dror Y, Freedman MH. Shwachman-Diamond syndrome: An inherited preleukemic bone marrow failure disorder with aberrant hematopoietic progenitors and faulty marrow microenvironment. Blood 1999;94:3048–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cesaro S, Oneto R, Messina C, et al. Haematopoietic stem cell transplantation for Shwachman-Diamond disease: a study from the European Group for blood and marrow transplantation. Br J Haematol 2005;131:231–6. 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2005.05758.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Boocock GR, Morrison JA, Popovic M, et al. Mutations in SBDS are associated with Shwachman-Diamond syndrome. Nat Genet 2003;33:97–101. 10.1038/ng1062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Dhanraj S, Matveev A, Li H, et al. Biallelic mutations in DNAJC21 cause Shwachman-Diamond syndrome. Blood 2017;129:1557–62. 10.1182/blood-2016-08-735431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Stepensky P, Chacón-Flores M, Kim KH, et al. Mutations in EFL1, an SBDS partner, are associated with infantile pancytopenia, exocrine pancreatic insufficiency and skeletal anomalies in aShwachman-Diamond like syndrome. J Med Genet 2017;54:558–66. 10.1136/jmedgenet-2016-104366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Carapito R, Konantz M, Paillard C, et al. Mutations in signal recognition particle SRP54 cause syndromic neutropenia with Shwachman-Diamond-like features. J Clin Invest 2017;127:4090–103. 10.1172/JCI92876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Nicolis E, Bonizzato A, Assael BM, et al. Identification of novel mutations in patients with Shwachman-Diamond syndrome. Hum Mutat 2005;25:410 10.1002/humu.9324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kent A, Murphy GH, Milla P. Psychological characteristics of children with Shwachman syndrome. Arch Dis Child 1990;65:1349–52. 10.1136/adc.65.12.1349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kerr EN, Ellis L, Dupuis A, et al. The behavioral phenotype of school-age children with shwachman diamond syndrome indicates neurocognitive dysfunction with loss of Shwachman-Bodian-Diamond syndrome gene function. J Pediatr 2010;156:433–8. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.09.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Perobelli S, Nicolis E, Assael BM, et al. Further characterization of Shwachman-Diamond syndrome: psychological functioning and quality of life in adult and young patients. Am J Med Genet A 2012;158A:567–73. 10.1002/ajmg.a.35211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Toiviainen-Salo S, Mäkitie O, Mannerkoski M, et al. Shwachman-Diamond syndrome is associated with structural brain alterations on MRI. Am J Med Genet A 2008;146A:1558–64. 10.1002/ajmg.a.32354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Booij J, Reneman L, Alders M, et al. Increase in central striatal dopamine transporters in patients with Shwachman-Diamond syndrome: additional evidence of a brain phenotype. Am J Med Genet A 2013;161A:102–7. 10.1002/ajmg.a.35687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Perobelli S, Alessandrini F, Zoccatelli G, et al. Diffuse alterations in grey and white matter associated with cognitive impairment in Shwachman-Diamond syndrome: evidence from a multimodal approach. Neuroimage Clin 2015;7:721–31. 10.1016/j.nicl.2015.02.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Dror Y, Donadieu J, Koglmeier J, et al. Draft consensus guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of Shwachman-Diamond syndrome. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2011;1242:40–55. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06349.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zemel BS, Pipan M, Stallings VA, et al. Growth charts for children with down syndrome in the United States. Pediatrics 2015;136:e1204–11. 10.1542/peds.2015-1652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Verbeek S, Eilers PH, Lawrence K, et al. Growth charts for children with Ellis-van Creveld syndrome. Eur J Pediatr 2011;170:207–11. 10.1007/s00431-010-1287-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gawlik A, Gawlik T, Augustyn M, et al. Validation of growth charts for girls with Turner syndrome. Int J Clin Pract 2006;60:150–5. 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2005.00633.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Tofts L, Das S, Collins F, et al. Growth charts for Australian children with achondroplasia. Am J Med Genet A 2017;173:2189–200. 10.1002/ajmg.a.38312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. The R Foundation for Statistical Computing. R version 3.3.3 (2017-03-06). [Google Scholar]

- 33. Cacciari E, Milani S, Balsamo A, et al. Italian cross-sectional growth charts for height, weight and BMI (2 to 20 yr). J Endocrinol Invest 2006;29:581–93. 10.1007/BF03344156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. de Onis M, Garza C, Victora CG, et al. The WHO Multicentre Growth Reference Study: planning, study design, and methodology. Food Nutr Bull 2004;25:S15–26. 10.1177/15648265040251S104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Cole TJ. The LMS method for constructing normalized growth standards. Eur J Clin Nutr 1990;44:45–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Cole TJ, Green PJ. Smoothing reference centile curves: the LMS method and penalized likelihood. Stat Med 1992;11:1305–19. 10.1002/sim.4780111005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Rigby RA, Stasinopoulus DM. Generalized Additive Models for Location Scale and Shape (GAMLSS) in R. J Stat Softw 2007;23:1–46. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Beets L, Rodríguez-Fonseca C, Hennekam RC. Growth charts for individuals with Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome. Am J Med Genet A 2014;164A:2300–9. 10.1002/ajmg.a.36654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Su X, Lau JT, Yu CM, et al. Growth charts for Chinese Down syndrome children from birth to 14 years. Arch Dis Child 2014;99:824–9. 10.1136/archdischild-2013-304494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Larnkaer A, Attrup Schrøder S, Schmidt IM, et al. Secular change in adult stature has come to a halt in northern Europe and Italy. Acta Paediatr 2006;95:754–5. 10.1080/08035250500527323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Bonthuis M, van Stralen KJ, Verrina E, et al. Use of national and international growth charts for studying height in European children: development of up-to-date European height-for-age charts. PLoS One 2012;7:e42506 10.1371/journal.pone.0042506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Harman K, Dobra R, Davies JC. Disease-modifying drug therapy in cystic fibrosis. Paediatr Respir Rev 2017:30031–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.