Abstract

Vibrio vulnificus is a halophilic Vibrio found globally. They are thought to be normal microbiome in the estuaries along the coasts associated with seawater and seashells. Infection usually results from consumption of raw oysters or shellfish or exposure of broken skin or open wounds to contaminated salt or brackish water. Clinical manifestations range from gastroenteritis to skin and subcutaneous infection and primary sepsis. Pathogen has the ability to cause infections with significant mortality in high-risk populations, including patients with chronic liver disease, immunodeficiency, diabetes mellitus and iron storage disorders. There is often a lack of clinical suspicion in cases due to Vibrio vulnificus leading to delay in treatment and subsequent mortality. Herein we report a case of necrotising fasciitis in a diabetic patient with alcoholic liver disease caused by Vibrio vulnificus which ended fatally.

Keywords: alcoholic liver disease, tropical medicine (infectious disease)

Background

Vibrio vulnificus is a halophilic, motile, Gram negative bacillus that belongs to the family Vibrionaceae found worldwide in warm coastal areas. Infection usually results from consumption or handling of raw contaminated seafood especially shellfish and oysters or exposure of broken skin or open wounds to contaminated salt or brackish water. More than 70% of the patients with Vibrio vulnificus infection have medical history or immunocompromised state and mortality rate is high even with prompt diagnosis and aggressive treatment. The number of infections caused by Vibrio vulnificus is on the rise due to a change in food habits and increase in number of high-risk population. Although India has a long coastline, infections due to this organism are rarely reported, probably indicating lack of awareness among both clinicians and laboratory personnel.1–3

Case presentation

A 52-year-old man, mechanic by occupation, hailing from a suburb of Chennai, a coastal city in south India, reported to the emergency department of our hospital in July 2017 with abdominal pain and distension, yellowish discolouration of the eyes and urine, bleeding from the gums and pain and swelling of the right lower limb for the past 3 days. He was a chronic alcoholic and smoker for the past 4 years and a diabetic on regular medications. He was a known case of alcoholic liver disease diagnosed 1 month ago when he had similar symptoms and was treated in a private hospital. The present symptoms started after an episode of alcohol intake.

On examination, he was well built and nourished, restless but oriented. He was found to be afebrile, had icterus and bilateral pitting pedal oedema. His blood pressure was 90/70 mm Hg and pulse rate was 97 beats/min without any ionotropic support and an oxygen saturation of 100% on room air. Abdomen was soft and distended. No organomegaly was detected. Shifting dullness was present indicating presence of free fluid in the abdomen. There was swelling and discolouration of the right lower limb with multiple haemorrhagic bullae over the dorsum of the foot. Surgical consultation was obtained and a provisional diagnosis of necrotising fasciitis was made based on the clinical examination. Tissue bit was sent for culture and sensitivity.

Investigations

White blood cell count was 12.3×109/L (neutrophils 88%), platelet count was 97×109/L, random blood glucose was 60 mg/dL, blood urea was 48 mg/dL, creatinine was 3.5 mg/dL, serum albumin was 2.4 mg/dL, total bilirubin was 6.51 mg/dL, direct bilirubin was 2.37 mg/dL, aspartate aminotransferase was 122 IU/L, alanine aminotransferase was 39 IU/L, glutamyl transpeptidase was 199 IU/L, alkaline phosphatase was 128 IU/L, prothrombin time was 34.6 s and international normalised ratio was 2.93.

Ultrasound abdomen revealed presence of moderate ascites and mild splenomegaly. Liver showed altered echoes with surface irregularities suggestive of parenchymal liver disease. Blood culture sent before the administration of antibiotics was sterile after 48 hours of aerobic incubation. Patient was also negative for hepatitis B surface antigen and anti-hepatitis C antibody by ELISA.

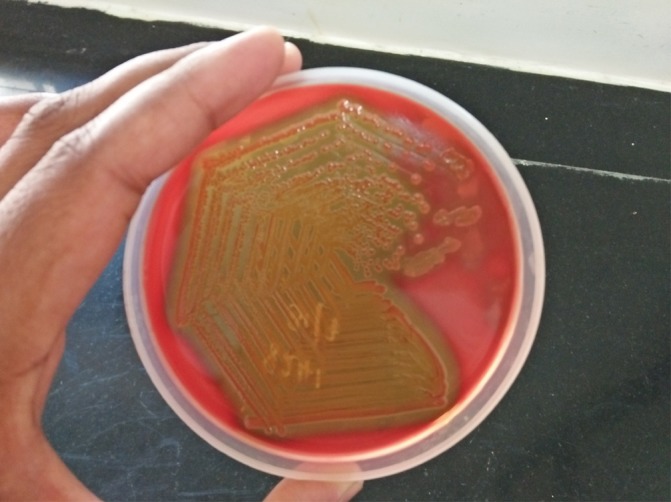

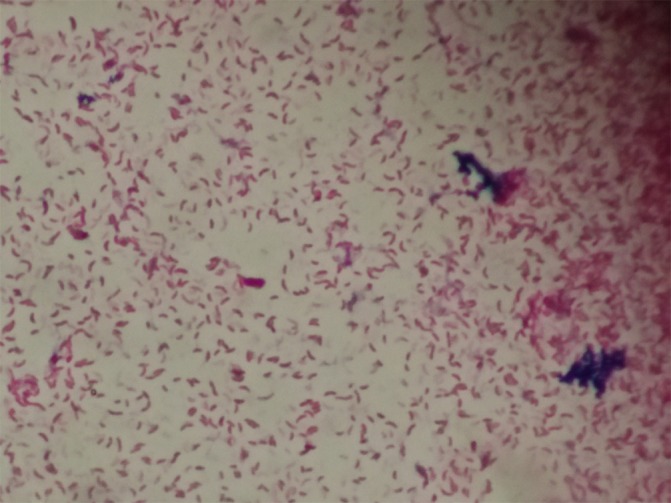

Gram stain from tissue bit did not reveal any organisms. After 24 hours of aerobic incubation at 37°C, there were grey moist colonies on 5% sheep blood agar with haemodigestion (figure 1) and lactose fermenting colonies on MacConkey agar. Gram stain from culture showed curved Gram negative bacilli (figure 2). The organism demonstrated darting motility. The colonies were oxidase and indole test positive, citrate was utilized, urea was not hydrolysed and kligler iron agar showed alkaline slant/acid butt reaction without production of gas and hydrogen sulphide. Acid was produced from glucose, lactose, salicin, maltose and cellobiose. It was negative for the utilisation of malonate, sucrose, mannitol, dulcitol, inositol, sorbitol, arabinose, raffinose, rhamnose and xylose. The organism was also found to be positive for orthonitrophenyl–D-galactopyranoside, lysine decarboxylase and ornithine decarboxylase and negative for arginine dihydrolase. The isolate did not grow in the absence of NaCl, however growth was observed in 6% NaCl but not in 10% NaCl. It was identified as Vibrio vulnificus based on the above characteristics. The isolate was sensitive to amikacin (30 µg), ceftazidime (30 µg), ceftriaxone(30 µg), ciprofloxacin (5 µg), gentamicin (10 µg), piperacillin tazobactam(100/10 µg), tetracycline (30 µg) and was resistant to ampicillin (10 µg).

Figure 1.

Growth on 5% sheep blood agar demonstrating haemodigestion.

Figure 2.

Gram stain showing curved Gram negative bacilli.

Treatment

The patient was started on broad spectrum antibiotics viz. injection piperacillin tazobactam 2.25 g at six-hourly intervals, injection amikacin 750 mg at 36-hourly intervals and injection vancomycin 1 g at 12-hourly intervals. Patient was also given injection thiamine, injection vitamin K, injection lactulose and injection pantoprazole. At 24 hours after admission, patient condition suddenly worsened and developed bradycardia. Injection norepinephrine was given and cardiopulmonary resuscitation was done.

Outcome and follow-up

Despite this, he continued to deteriorate and expired due to septic shock.

Discussion

Vibrio vulnificus infection has been reported in diverse climate zones throughout the world. Environmental studies have shown that Vibrio vulnificus is part of the normal bacterial flora in the estuaries along the coasts and is associated with seawater and seashells. It is usually seen in water where the temperatures are above 20°C and salinity is between 5 and 25 parts per thousand (ppt). However salinities greater than 30 ppt will substantially reduce the concentration of Vibrio vulnificus. As a result most of the cases can be traced to tropical and subtropical areas.4The present case was admitted in the emergency department during the month of mid-July when the water temperatures and Vibrio vulnificus colony count is typically high.

Necrotising fasciitis due to Vibrio vulnificus has been increasingly reported from the eastern countries like Taiwan and Hong Kong.5–8 Cheung et al 8 reported a series of necrotising fasciitis (NF) cases, where 83% were caused by Vibrio species. Fishermen were recognised to be the susceptible individuals. He reported that up to 50% and 11% of the shellfish and crabs, respectively, were culture positive for Vibrio species during the months of summer. In India, studies have indicated presence of Vibrio vulnificus in the oysters and clams ranging from 16.6% to 56.6%.9–11 Though India has a long coastline and many people depend on fishing for their livelihood, not many cases of Vibrio vulnificus infection have been reported in the country probably due to lack of awareness among the clinicians and laboratory personnel, or proper cooking of seafood before consumption.

As few as five cases of Vibrio vulnificus infection have been reported from the country, two cases of gastroenteritis, two cases of wound infection and one case of necrotising fasciitis, all from the west coast of India.2 12–14 The necrotising fasciitis case reported by Madiyal et al, involved a 52-year-old man with alcoholic liver disease, who presented with sepsis and ulceration and haemorrhagic bullae over both lower limbs. The patient was started on piperacillin-tazobactam and teicoplanin which was changed to ceftazidime and doxycycline when suspected Vibrio was isolated from blood culture. The patient recovered with treatment.

Infections associated with Vibrio vulnificus were first reported in 1979 by Blake et al, of the USA Centres for Disease Control who reviewed 15 cases of wound infection due to Vibrio vulnificus. At that time, it was described as ‘rare, unnamed halophilic lactose fermenting Vibrio species’. Infection is usually acquired by consumption or handling of contaminated seafood such as shellfish.15 We could not elicit any history of raw shellfish intake though the practice of eating raw oyster/shellfish is not common in this part of the country. There were no obvious cuts or injury in the lower limb which could have acted as the portal of entry. However, possibility of minor abrasions/wounds could not be ruled out considering the profession of the patient. Cases of spontaneous cellulitis due to Vibrio vulnificus also have occurred in the limbs without an obvious portal of entry. This postulates that visible skin breaks or wounds are not absolutely necessary for cases of soft tissue infection of limbs exposed to contaminated seafood or water.16–19

Rare and atypical presentations include pneumonia, meningitis, endometritis, septic arthritis, endophthalmitis and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis.1 16 20–24 Most of the cases occur in patients with some underlying disease condition which is either immunocompromising or lead to elevated serum iron levels eg, chronic hepatitis especially cirrhosis due to alcohol intake or chronic hepatitis B or C infection, cirrhosis, diabetes mellitus, steroid medication, multiple myeloma, haemochromatosis, end stage renal disease and so on. Several reports on animal studies suggest that the bacterial load required to cause a fatal disease decreases considerably in mice with experimentally increased iron levels. This has been correlated in human cases where a severe, highly fatal disease is observed in patients of haemochromatosis or in patients with iron saturation of transferrin raised ≥50%.25–27The iron is found to enhance the growth of the organism and decrease the function of the neutrophils.1 Unfortunately, the iron concentration in our patient was not determined.

Treatment of infection with Vibrio vulnificus should be aggressive because of the rapid onset and high mortality associated with it. Vibrio vulnificus is usually susceptible in vitro to multiple antimicrobial agents. A regimen of ceftazidime and doxycycline for 7–14 days is recommended by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for wound infections.1 Early and aggressive surgical exploration is required for the treatment of necrotising fasciitis and gangrene to remove the necrotic debris that will further help in the spread of infection. Antibiotics alone without surgical intervention is usually ineffective due to the thrombosis of the blood vessels supplying the affected area. Mortality is said to be low in case of necrotising fasciitis if adequate debridement and fasciotomy has been performed early.3 28–32 In the present case, piperacillin-tazobactam, amikacin and vancomycin were administered empirically and surgical debridement was done the next day. Unfortunately, the patient succumbed to the disease on the same day.

The case presented earlier describes a patient with necrotising soft tissue infection. History of contact of open wounds to contaminated salt water or handling contaminated seafood especially shellfish and oysters could not be obtained due to the lack of clinical suspicion of Vibrio vulnificus causing necrotising fasciitis in this case. The patient had alcoholic liver disease and diabetes mellitus which are well-recognised risk factors for Vibrio vulnificus infection. Considering the above findings, it is difficult to tell whether it is a case of primary sepsis with metastatic skin lesions or wound infection due to Vibrio vulnificus. Absence of fever, gastrointestinal symptoms and negative blood culture report points more towards the diagnosis of wound infection due to Vibrio vulnificus rather than primary sepsis.

Learning points.

Vibrio vulnificus is a halophilic marine Vibrio implicated in causing infections in high-risk groups which are often fatal if diagnosis and management are delayed. Clinicians and laboratory personnel should have a high index of suspicion, thereby helping in early and accurate diagnosis for the prompt initiation of therapy considering the high mortality associated with Vibrio vulnificus infections. As definitive diagnosis may take 48 hours, it may be prudent to start empirical therapy directed against Vibrio vulnificus in patients with underlying liver disease specially from coastal areas and a positive exposure history.

Footnotes

Contributors: PB: preparation of manuscript, laboratory workup. MB: preparation of the manuscript. SS: critical revision of the manuscript and final approval. TK: treating physician and critical revision of the manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Next of kin consent obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Horseman MA, Surani S. A comprehensive review of Vibrio vulnificus: an important cause of severe sepsis and skin and soft-tissue infection. Int J Infect Dis 2011;15:e157–e166. 10.1016/j.ijid.2010.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Madiyal M, Eshwara VK, Halim I, et al. A rare glimpse into the morbid world of necrotising fasciitis: Flesh-eating bacteria Vibrio vulnificus. Indian J Med Microbiol 2016;34:384 10.4103/0255-0857.188361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Linkous DA, Oliver JD. Pathogenesis of Vibrio vulnificus . FEMS Microbiol Lett 1999;174:207–14. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1999.tb13570.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Oliver JD. Wound infections caused by Vibrio vulnificus and other marine bacteria. Epidemiol Infect 2005;133:383–91. 10.1017/S0950268805003894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tsai YH, Huang KC, Shen SH, et al. Microbiology and surgical indicators of necrotizing fasciitis in a tertiary hospital of southwest Taiwan. Int J Infect Dis 2012;16:e159–e165. 10.1016/j.ijid.2011.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hsu JC, Shen SH, Yang TY, et al. Necrotizing fasciitis and sepsis caused by Vibrio vulnificus and Klebsiella pneumoniae in diabetic patients. Biomed J 2015;38:136 10.4103/2319-4170.137767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lee YC, Hor LI, Chiu HY, et al. Prognostic factor of mortality and its clinical implications in patients with necrotizing fasciitis caused by Vibrio vulnificus. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2014;33:1011–8. 10.1007/s10096-013-2039-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cheung JP, Fung B, Tang WM, et al. A review of necrotising fasciitis in the extremities. Hong Kong Med J 2009;15:44-5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sangeetha MS, Shekar M, Venugopal MN. Occurrence of clinical genotype Vibrio vulnificus in clam samples in Mangalore, Southwest coast of India. J Food Sci Technol 2017;54:786–91. 10.1007/s13197-017-2522-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Parvathi A, Kumar HS, Karunasagar I, et al. Detection and enumeration of Vibrio vulnificus in oysters from two estuaries along the southwest coast of India, using molecular methods. Appl Environ Microbiol 2004;70:6909–13. 10.1128/AEM.70.11.6909-6913.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mookerjee S, Batabyal P, Sarkar MH, et al. Seasonal prevalence of enteropathogenic vibrio and their phages in the riverine estuarine ecosystem of south bengal. PLoS One 2015;10:e0137338 10.1371/journal.pone.0137338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Saraswathi K, Barve SM, Deodhar LP. Septicaemia due to Vibrio vulnificus. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 1989;83:714 10.1016/0035-9203(89)90406-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. De A, Mathur M. Vibrio vulnificus diarrhea in a child with respiratory infection. J Glob Infect Dis 2011;3:310 10.4103/0974-777X.83544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. D’Souza C, Kumar BK, Kapinakadu S, et al. PCR-based evidence showing the presence of Vibrio vulnificus in wound infection cases in Mangaluru, India. Int J Infect Dis 2018;68:74–6. 10.1016/j.ijid.2018.01.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Blake PA, Weaver RE, Hollis DG. Diseases of humans (other than cholera) caused by vibrios. Annu Rev Microbiol 1980;34:341–67. 10.1146/annurev.mi.34.100180.002013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tacket CO, Brenner F, Blake PA. Clinical features and an epidemiological study of Vibrio vulnificus infections. J Infect Dis 1984;149:558–61. 10.1093/infdis/149.4.558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kuo YL, Shieh SJ, Chiu HY, et al. Necrotizing fasciitis caused by Vibrio vulnificus: epidemiology, clinical findings, treatment and prevention. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2007;26:785–92. 10.1007/s10096-007-0358-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hsueh PR, Lin CY, Tang HJ, et al. Vibrio vulnificus in Taiwan. Emerg Infect Dis 2004;10:1363–8. 10.3201/eid1008.040047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tacket CO, Barrett TJ, Mann JM, et al. Wound infections caused by Vibrio vulnificus, a marine vibrio, in inland areas of the United States. J Clin Microbiol 1984;19:197–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kumamoto KS, Vukich DJ. Clinical infections of Vibrio vulnificus: a case report and review of the literature. J Emerg Med 1998;16:61–6. 10.1016/S0736-4679(97)00230-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Emamifar A, Asmussen Andreasen R, Skaarup Andersen N, et al. Septic arthritis and subsequent fatal septic shock caused by Vibrio vulnificus infection. BMJ Case Rep 2015;2015(bcr2015212014). 10.1136/bcr-2015-212014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kim CS, Bae EH, Ma SK, et al. Severe septicemia, necrotizing fasciitis, and peritonitis due to Vibrio vulnificus in a patient undergoing continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis: a case report. BMC Infect Dis 2015;15:422 10.1186/s12879-015-1163-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ulusarac O, Carter E. Varied clinical presentations of Vibrio vulnificus infections: a report of four unusual cases and review of the literature. South Med J 2004;97:163–8. 10.1097/01.SMJ.0000100119.18936.95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chuang YC, Yuan CY, Liu CY, et al. Vibrio vulnificus infection in Taiwan: report of 28 cases and review of clinical manifestations and treatment. Clin Infect Dis 1992;15:271–6. 10.1093/clinids/15.2.271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wright AC, Simpson LM, Oliver JD. Role of iron in the pathogenesis of Vibrio vulnificus infections. Infect Immun 1981;34:503–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Starks AM, Schoeb TR, Tamplin ML, et al. Pathogenesis of infection by clinical and environmental strains of Vibrio vulnificus in iron-dextran-treated mice. Infect Immun 2000;68:5785–93. 10.1128/IAI.68.10.5785-5793.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hor LI, Chang YK, Chang CC, et al. Mechanism of high susceptibility of iron-overloaded mouse to Vibrio vulnificus infection. Microbiol Immunol 2000;44:871–8. 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2000.tb02577.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Singh G, Sinha SK, Adhikary S, et al. Necrotising infections of soft tissues--a clinical profile. Eur J Surg 2002;168:366–71. 10.1080/11024150260284897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Fujisawa N, Yamada H, Kohda H, et al. Necrotizing fasciitis caused by Vibrio vulnificus differs from that caused by streptococcal infection. J Infect 1998;36:313–6. 10.1016/S0163-4453(98)94387-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Muldrew KL, Miller RR, Kressin M, et al. Necrotizing fasciitis from Vibrio vulnificus in a patient with undiagnosed hepatitis and cirrhosis. J Clin Microbiol 2007;45:1058–62. 10.1128/JCM.00979-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Akhondi H, Lopez AG. Necrotizing Fasciitis Secondary to Vibrio vulnificus. J Med Cases 2014;5:650–2. 10.14740/jmc2026e [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Joynt GM, Gomersall CD, Lyon DJ. Severe necrotising fasciitis of the extremities caused by Vibrionaceae: experience of a Hong Kong tertiary hospital. Hong Kong Med J 1999;5:63–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]