Abstract

Acetylcholine binds to muscarinic receptors to play a key role in the pathophysiology of asthma, leading to bronchoconstriction, increased mucus secretion, inflammation and airway remodelling. Anticholinergics are muscarinic receptor antagonists that are used in the treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma. Recent in vivo and in vitro data have increased our understanding of how acetylcholine contributes to the disease manifestations of asthma, as well as elucidating the mechanism of action of anticholinergics. This review assesses the latest literature on acetylcholine in asthma pathophysiology, with a closer look at its role in airway inflammation and remodelling. New insights into the mechanism of action of anticholinergics, their effects on airway remodelling, and a review of the efficacy and safety of long-acting anticholinergics in asthma treatment will also be covered, including a summary of the latest clinical trial data.

Short abstract

Pre-clinical data suggest that anticholinergics can reduce acetylcholine-induced airway inflammation and remodelling http://ow.ly/xqAQ30loP8F

Introduction

Acetylcholine is the predominant parasympathetic neurotransmitter in the airways [1], and plays a key role in the pathophysiology of obstructive airway diseases, such as asthma, through bronchial smooth muscle contraction and mucus secretion [2]. Pre-clinical evidence supports an additional role in airway inflammation and remodelling [3]. Acetylcholine binds to muscarinic receptors [2, 3], making these receptors an attractive target for respiratory disease therapy, such as in asthma.

Anticholinergics are muscarinic receptor antagonists that have been used to treat chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) for several years and are now used as add-on treatment in asthma. In this review, we assess the latest literature on acetylcholine in asthma pathophysiology, including its role in airway inflammation and remodelling. We also review new insights into the mechanism of action of anticholinergics and their effects on airway remodelling. A comparison of the efficacy and safety of long-acting anticholinergics in asthma treatment will also be covered, with a summary of the latest clinical trial data.

The role of acetylcholine in asthma pathophysiology

Increased acetylcholine signalling in asthma

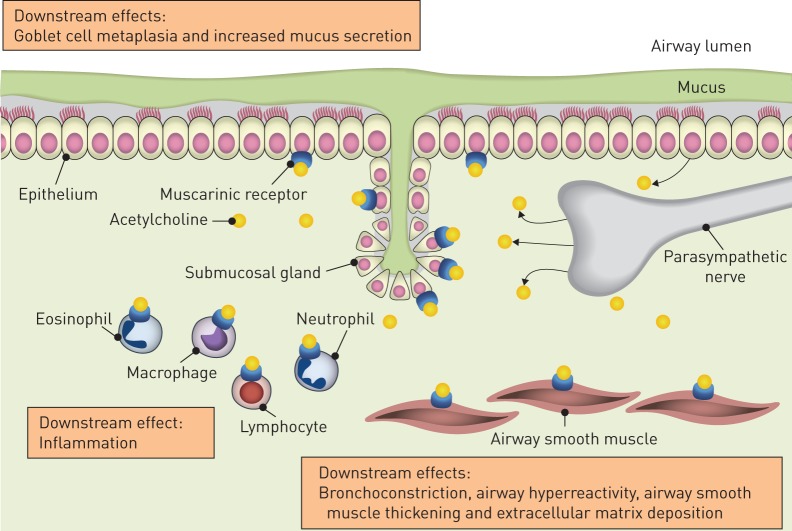

Research has shown that parasympathetic neuronal activity, through acetylcholine signalling, is increased in the pathophysiology of asthma [2, 3]. Acetylcholine is released from airway neurons and non-neuronal cells such as airway epithelial cells [4]. Other non-neuronal sources include inflammatory cells [2]. Acetylcholine binds to airway muscarinic receptors to trigger smooth muscle contraction and mucus secretion (figure 1) [2, 3]. There are five identified muscarinic receptors that belong to the G-protein-coupled receptor family [5]; however, only M1, M2 and M3 receptors have been shown to play major roles in airway physiology, and in diseases such as asthma and COPD [5]. M1 receptors are expressed by epithelial cells and in the ganglia; they regulate electrolyte and water secretion, and aid parasympathetic neurotransmission, respectively [6]. M2 receptors are expressed in airway smooth muscle and on parasympathetic neurons; they have a very limited role in contraction on airway smooth muscle. However, M2 receptors act as autoreceptors on parasympathetic neurons to limit acetylcholine release, thus limiting vagal reflex-induced bronchoconstriction and mucus secretion [2, 7]. M3 receptors are the primary receptor subtype for bronchial smooth muscle contraction, and are found in airway smooth muscle and submucosal glands [2, 5, 8].

FIGURE 1.

A summary of the role of acetylcholine in asthma pathophysiology. Acetylcholine is the predominant parasympathetic neurotransmitter in the airways. It is released from airway neurons and non-neuronal cells, such as airway epithelial cells, and binds to muscarinic M1, M2 and M3 receptors. These receptors are found on airway epithelial cells, smooth muscle cells and submucosal glands. Binding of acetylcholine to the muscarinic receptors triggers a host of downstream effects associated with the pathophysiology of asthma.

Several mechanisms account for increased neural activity in asthmatic airways [2]. Established mechanisms include loss of epithelial barrier function due to an inflammatory local tissue microenvironment, which exposes the neurons to the airway lumen [2]. Inflammatory mediators and even direct contact of airway nerves with eosinophils can then activate the exposed neurons to trigger vagal reflex-mediated bronchoconstriction [9]. This bronchoconstriction is compounded by the dysfunction of M2 autoreceptors; this results in increased acetylcholine release, leading to airway hyperreactivity [5]. M2 receptor dysfunction has been shown in animal model studies of airway disease following exposure to allergens, ozone and viral infections [10]. In support of a role in asthma, the M2 agonist pilocarpine protects from reflex bronchoconstriction in normal subjects, but not in those with asthma [11]. M2 receptor dysfunction is thought to be driven by eosinophils and the secretion of major basic protein [10, 12]. In addition, tumour necrosis factor-α appears to play a key role in driving M2 autoreceptor dysfunction in animal models of ozone- and virus-induced airway hyperreactivity [13, 14]. The increase in acetylcholine signalling on M1 and M3 receptors, and the M2 receptor dysfunction, may all contribute to the increased bronchoconstriction, mucus secretion, inflammation and airway remodelling, as discussed in the following sections.

An exciting, novel development in this area of research is neuronal plasticity and remodelling, which may underpin persistent changes in cholinergic signalling in asthma. Airway neurons have received little attention in studies into mechanisms of tissue remodelling in asthma, yet seem to switch to a cholinergic isotype and branch more excessively in response to inflammatory insults, including allergens and eosinophilic inflammation [15, 16]. Intriguingly, a recent study showed that such neuronal plasticity may be a feature of early-life exposure to allergens, following which the neurotrophin NT-4 mediates neuronal remodelling and persistent airway hyperresponsiveness beyond the immediate period of allergen exposure [17]. In light of the observation that single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in genes that encode neurotrophic factors, such as brain-derived neurotrophic factor, may be associated with asthma and allergic rhinitis [18], pre-clinical studies that investigate the molecular control of this response and studies that characterise the pathological features of neuronal remodelling in patients with asthma are clearly needed.

Downstream effects of increased acetylcholine signalling: mechanisms and therapeutic implications

Bronchoconstriction

The increased vagal activity brought on by increased acetylcholine signalling contributes to bronchoconstriction; in fact, the improvement in forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) in response to tiotropium is fairly similar to that induced by the β2-agonist salmeterol in mild-to-moderate asthma patients [19]. This is intriguing, as the long-acting anticholinergic blocks a single mediator only, whereas the β2-agonist is a functional antagonist of contraction, irrespective of the mediator that caused the effect. Observations from pre-clinical studies in animals show that this may be explained by the use of the cholinergic system by inflammatory mediators and bronchoconstrictors even if these do not directly act on muscarinic receptors. For example, results from an in vivo study of allergen-induced bronchial hyperreactivity in sensitised guinea pigs show that vagally derived acetylcholine contributes to histamine-induced bronchoconstriction in allergen-challenged animals on a selective basis [20]. Thromboxane A2, a potent mediator of airway constriction, is dependent on parasympathetic signalling in both healthy and inflamed airways [21]. Binding of thromboxane A2 to its receptors is thought to substantially increase the release of acetylcholine [21]. Increased vagal activity is also thought to contribute to the early asthmatic reaction and late asthmatic reaction (LAR). Data from pre-clinical in vivo models suggest allergens activate airway sensory nerves, at least in part via transient receptor potential ankyrin-1 channels [22]. This initiates a central reflex event leading to acetylcholine-induced bronchoconstriction, which may be responsible for the LAR [22]. As such, the cholinergic reflex arc promotes bronchoconstriction to histamine, inflammatory mediators and allergens.

In a guinea pig model of acute allergic asthma, tiotropium even reverses and protects against allergen-induced airway hyperresponsiveness [23]. A clinical study comparing the effectiveness of indacaterol/tiotropium and indacaterol (both in combination with inhaled corticosteroids (ICSs)) on mannitol-induced airway responsiveness found no additional effect of tiotropium on top of indacaterol on mannitol median effective dose (ED50) [24], whereas sulfur dioxide-induced airway hyperresponsiveness in asthmatic subjects is subject to cholinergic control [11]. Thus, whereas it is clear that acetylcholine contributes to bronchoconstriction in asthma, the contribution of the cholinergic reflex arc to (the development of) airway hyperresponsiveness in asthma is not extensively reported and needs further study.

Increased mucus secretion

Acetylcholine-induced mucus secretion is also a key feature of asthma. Mucus glands are innervated by parasympathetic nerves and release mucus in response to electrical field stimulation [25]. Goblet cells do express muscarinic receptors, but require relatively high concentrations of muscarinic agonist to promote secretory activity [26]. An interesting novel finding is that, independent of any effects on airway inflammation, muscarinic receptors may also control goblet cell differentiation. Repeated methacholine challenges promote the presence of mucus-positive cells in the airway epithelium of patients with mild asthma [27]. In a study of human airway epithelial cells cultured on an air–liquid interface, tiotropium was shown to attenuate goblet cell metaplasia induced by interleukin (IL)-13 [28]. In addition, tiotropium reversed established goblet cell hyperplasia [28]; interestingly, no exogenous muscarinic receptor agonist was added to the system, indicating non-neuronal acetylcholine produced by the epithelial cells themselves contributes to goblet cell differentiation. Mechanistically, this was dependent on the regulation of the FoxA2 and FoxA3 transcription factors that regulate mucus cell differentiation by IL-13, which was prevented by tiotropium. Komiya et al. [29] found that the anticholinergic tiotropium had no effect on goblet cell metaplasia or mucin secretion induced by IL-13, but decreased mucin secretion stimulated by neutrophil elastase. IL-17-induced acetylcholine production promoted mucus secretion for the bronchial epithelial cell line 16-HBE [30].

In vivo data have shown that when sensitised M3 receptor-deficient mice were exposed to allergen challenge, they had a 30% lower increase in goblet cells compared with wild-type mice (p<0.05) [31]. They also showed a significantly lower increase in the mucus-producing gene MUC5AC compared with wild-type mice (35%; p<0.05) [31]. Treatment with tiotropium in sensitised guinea pigs also completely prevented allergen-induced mucus gland hypertrophy [32], a finding that was also reported for house dust mite-induced responses in mice [33]. Repeated exposure of mice to cholinergic agonists also promoted goblet cell presence in the airway epithelium [34].

Thus, whereas it appears that goblet cell differentiation of airway epithelium is indeed subject to cholinergic control, the underlying mechanisms are not yet fully established. Cholinergic receptors are Gq-coupled receptors and therefore not presumed to directly couple to STAT (signal transducer and activator of transcription) pathway activation, so the impact on IL-13, IL-17 and neutrophil elastase signalling is unlikely to be through direct modulation of that activity [2]. An additional area that remains unexplored is whether goblet cell hyperplasia in asthmatic patients is sensitive to anticholinergic treatment.

Airway inflammation

In addition to bronchoconstriction and mucus secretion, acetylcholine also contributes to airway inflammation, although at present this has only been reported in pre-clinical models and is yet to be confirmed in asthmatic subjects. In vitro, acetylcholine signalling leads to the release of eosinophil chemotactic activity from bovine bronchial epithelial cells (BECs) in a dose- and time-dependent manner [35]. Of interest, eosinophils have been shown to gather around the nerves in airways of sensitised guinea pigs and humans who have died of fatal asthma [36]. Other data suggest that acetylcholine signalling polarises dendritic cells towards a T-helper cell type 2 (Th2) profile [37]. Incubation of dendritic cells with acetylcholine stimulated production of two chemokines that recruit Th2 cells to allergic inflammation sites (macrophage-derived chemokine, and thymus and activation-regulated chemokine) [37]. Mechanistically, the effect is not fully clear at this stage, but regulation of the pro-inflammatory transcription factor NF-κB and of protein kinase C (PKC) by muscarinic receptors may play a role [38].

In vivo, anticholinergics can reduce the acetylcholine-induced inflammatory response by inhibiting the release of chemokines and recruitment of inflammatory cells [39]. Aclidinium, a long-acting anticholinergic, has been shown to reduce both allergen-induced and methacholine-induced airway hyperresponsiveness in both naive and sensitised mice [40]. There was also a substantial decrease (56±4%) in allergen-induced eosinophilia with aclidinium treatment, suggesting an anti-inflammatory role [40]. Similarly, tiotropium has shown anti-inflammatory properties: in a rat model of resistive breathing, tiotropium was shown to attenuate the increase in bronchoalveolar lavage neutrophil number, IL-1β and IL-6 levels, and lung injury score [41]. Tiotropium was also shown to reduce inflammation in a dose-dependent manner in sensitised mice [33]. Another study of sensitised mice showed a significant reduction in airway inflammation with tiotropium [42]. Furthermore, tiotropium reduces eosinophilic inflammation in chronically challenged guinea pigs to a similar extent as budesonide [32] and tiotropium synergises with ciclesonide in reducing allergen-induced inflammation in the same model [43].

An intriguing, novel finding is that cholinergic nerves may release the recently identified neuromedin U, which participates in Th2-type inflammation by directly activating eosinophils and potentially type 2 innate lymphoid cells [44–46]. In light of the aforementioned regulation of neuronal plasticity in asthma, this is an exciting new development linking cholinergic regulation to airway inflammation that needs to be followed up to establish its importance in asthma. Immunomodulatory effects of anticholinergics could prevent asthma exacerbations by reducing inflammation and mucus production in the airways, and indeed tiotropium was reported to reduce exacerbations clinically [33]. Whether this is truly due to anti-inflammatory activity by anticholinergics is a major open question that remains unanswered.

Airway remodelling

Airway remodelling involves structural changes to the airways, such as goblet cell metaplasia, airway smooth muscle thickening and extracellular matrix deposition [28, 47]. Several pathways contribute to remodelling, including growth factors, mediators and extracellular matrix proteins present in the airway wall [48]. In addition, there is some evidence indicating cholinergic control of airway remodelling in asthma patients. For example, tiotropium reduces airway wall dimensions in combination with long-acting β2-agonist (LABA) and ICS therapy in patients with asthma, as assessed by quantitative computed tomography [49]. Furthermore, repeated bronchoconstriction with either dust mite or methacholine challenge in patients with asthma increased the percentage of epithelium staining for mucus-producing cells and subepithelial markers for airway remodelling. The fact that this change was not seen in the control group, and was reversible with albuterol treatment, suggests that bronchoconstriction can trigger excess mucus production, leading to further airway obstruction [27]. Interestingly, eosinophilic inflammation was only seen in patients who received the dust mite allergen. This supports the idea that acetylcholine-induced bronchoconstriction alone can induce airway remodelling [27].

In vitro and animal model studies indicate that these changes are mediated mostly by M3 receptors, which in turn are activated by acetylcholine. In vitro data have shown that downstream signalling from muscarinic receptors triggers glycogen synthase kinase (GSK)-3 inhibition, which, in its active state, acts to repress airway smooth muscle proliferation. This suggests a possible mechanism for the accumulation of smooth muscle in airway remodelling [50]. Muscarinic receptors control contractile protein accumulation in combination with transforming growth factor (TGF)-β as well via such a GSK-3-dependent mechanism [51], whereas the cooperative regulation of extracellular matrix protein production by muscarinic receptors and TGF-β appears to involve M2 receptors [52]. An in vitro model of guinea pig lung slices found that methacholine-induced bronchoconstriction leads to contractile protein expression, such as smooth muscle myosin. This was mediated by the release of bioactive TGF-β [53], thought to be responsible for several features of airway remodelling, such as myofibroblast transformation, enhanced collagen synthesis and deposition in the sub-basement membrane, and increased expression of smooth muscle contractile protein [47, 54]. The release of bioactive TGF-β in response to methacholine [55] supports these findings. Further evidence suggests that it is the mechanical effects of acetylcholine-mediated bronchoconstriction that causes airway remodelling [3, 56, 57]. BECs obtained from volunteers with asthma showed increased secretion of TGF-β and granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor when subjected to compressive forces when compared with BECs from volunteers without asthma [47].

In vivo data showed that wild-type mice had a 1.7-fold increase in staining for α-smooth muscle actin following allergen challenge; this increase was completely absent in mice deficient in M3 receptors [31]. This study did not find any stimulatory role for M3 receptors in allergic inflammation, thus suggesting that acetylcholine-induced remodelling can be independent of inflammation [31].

Use of tiotropium in sensitised mice resulted in reductions in goblet cell metaplasia, airway smooth muscle thickness and levels of TGF-β, suggesting a role for tiotropium in reduction of airway remodelling and hyperresponsiveness [42]. This is further supported by a study of tiotropium in sensitised guinea pigs, which resulted in ≤75% inhibition in airway smooth muscle mass [32]. Combination therapy of tiotropium with ciclesonide in a guinea pig model of chronic asthma also significantly reduced allergen-induced airway smooth muscle mass by 81% (p<0.05) [43].

These data add insight into the role of bronchoconstriction in airway remodelling. However, a recent study indicates that repeated exposure of mice to methacholine induces changes in goblet cell hyperplasia and macrophage presence, but does not impact airway responsiveness [34]. Clearly, further studies are needed to investigate in more detail the hypothesis that bronchoconstriction can drive airway remodelling independently from inflammation. In particular, the underlying mechanisms need further clarification to explain the relatively diverse functional and pathological outcomes in the aforementioned different experimental models.

Anticholinergics in asthma

There is extensive experience of anticholinergic use in obstructive respiratory diseases, as they have been approved for use in COPD for many years [58]. There are five anticholinergics currently licensed for use in COPD: ipratropium [59], aclidinium [60], glycopyrronium (also known as glycopyrrolate) [61], umeclidinium [62] and tiotropium [63]. However, only two anticholinergics have been approved for use in asthma: ipratropium and tiotropium. Ipratropium is a short-acting anticholinergic approved for use in the treatment of reversible airways obstruction in acute and chronic asthma in combination with β2-agonists [5, 59], whereas tiotropium is the only long-acting anticholinergic approved for use in asthma as add-on therapy to ICS and a LABA [63].

Properties of anticholinergics

Anticholinergics are reversible competitive inhibitors of M1, M2 and M3 receptors [6], and have been shown to have similar binding affinity for all five muscarinic receptor subtypes [64]. The time spent at the muscarinic receptors determines the duration of action of each drug. For example, the long-acting anticholinergics show kinetic selectivity for M3 receptors over M2 receptors (table 1), as they dissociate more slowly from M3 receptors than M2 receptors [6, 65, 66]. In vitro data have shown that aclidinium dissociates slightly faster from M2 and M3 receptors than tiotropium, but more slowly than ipratropium and glycopyrronium (residence half-lives at M3 receptors are shown in table 1) [65]. In a separate set of experiments conducted by Salmon et al. [67], binding studies conducted using Chinese hamster ovary cells expressing human M1−M5 receptor subtypes showed that the pKi for umeclidinium was 9.8 (M1), 9.8 (M2), 10.2 (M3), 10.3 (M4) and 9.9 (M5). Dissociation of umeclidinium from the M3 receptor was slower than that for the M2 receptor. The half-life of tiotropium in this study was longer than that of umeclidinium for both the M2 receptor (39.2 versus 9.4 min, tiotropium and umeclidinium, respectively) and M3 receptor (272.8 versus 82.2 min, tiotropium and umeclidinium, respectively) [67]. Casarosa et al. [65] also reported that tiotropium dissociates more slowly from the M3 than the M2 receptor; however, the half-lives were 27 and 2.6 h, respectively. The differences in half-lives observed in these two studies may have been due to methodological differences employed in the two studies.

TABLE 1.

Binding affinities (pKi) and dissociation half-lives (t1/2) of anticholinergics against muscarinic M1, M2 and M3 receptor subtypes

| pKi | t1/2 h | |||||

| M1 | M2 | M3 | M1 | M2 | M3 | |

| Ipratropium | 9.40 | 9.53 | 9.58 | 0.1 | 0.03 | 0.22 |

| Aclidinium | 10.78 | 10.68 | 10.74 | 6.4 | 1.8 | 10.7 |

| Glycopyrronium | 10.09 | 9.67 | 10.04 | 2.0 | 0.37 | 6.1 |

| Tiotropium | 10.80 | 10.69 | 11.02 | 10.5 | 2.6 | 27 |

Dissociation constants determined by analysing competition kinetics curves in the presence of [N-methyl-3H]scopolamine and different concentrations of unlabelled antagonist. Data from [65].

Clinical data of anticholinergics in airway inflammation and remodelling

There are limited clinical data to explain the role of anticholinergics in airway inflammation and remodelling in patients with asthma. A clinical study in patients with symptomatic asthma receiving ICS and LABA assessed the effect of tiotropium on airway geometry and inflammation. Tiotropium significantly decreased airway wall area and thickness, corrected for body surface area (p<0.05 for both), and improved airflow obstruction. These data suggest a potential protective effect of tiotropium against bronchoconstriction and airway remodelling [49]. Patients with severe asthma have shown improved symptoms and lung function with tiotropium add-on to ICS, which suggests a role in reducing airway inflammation [68]. The clinical data of anticholinergics in asthma are summarised later in this review.

Comparison of mechanism of action: anticholinergics, short-acting β2-agonists and long-acting β2-agonists

Anticholinergics have a different mechanism of action compared with short-acting β2-agonists (SABAs) and LABAs, which bind to airway β2-receptors to trigger smooth muscle relaxation [69, 70]. However, data suggest concomitant use of anticholinergics with β2-agonists can enhance the β2-agonist-induced bronchodilation via intracellular processes [71]. Glycopyrronium was shown to enhance muscarinic contraction with SABAs by decreasing Ca2+ sensitisation and dynamics through PKC and calcium-activated potassium (KCa) channels [71]. This suggests that PKC and KCa channels may be involved in the cross-talk between anticholinergics and β2-agonists. Studies assessing aclidinium and formoterol fumarate, and glycopyrronium and indacaterol fumarate, have shown enhanced benefits on airway smooth muscle relaxation in human isolated bronchi [72, 73]. LABA and anticholinergic combination therapy may also mitigate daily variations in sympathetic and parasympathetic activity. A clinical study in patients with COPD showed that tiotropium was associated with sustained improvements in lung function throughout 24 h, without affecting circadian variability [74]. These data show that dual bronchodilation with anticholinergic add-on therapy and β2-agonism has a greater benefit than single bronchodilation. Furthermore, combination therapy of ipratropium on top of salbutamol prolongs the duration of action of the bronchodilator effect [75]. These and other considerations, such as the frequent use of ipratropium (4 puffs per day), have triggered studies into the role of long-acting anticholinergics in COPD and, more recently, in asthma.

Use of short-acting anticholinergics in asthma

Ipratropium is a non-selective antagonist of muscarinic receptors [76], approved for use in acute and chronic asthma in combination with β2-agonists [5, 59]. It can be used as an alternative reliever agent for patients with asthma who are refractory to β2-agonists [77]. However, data suggest that it is not as effective as SABAs; a study of 188 patients with chronic bronchitis (n=113) or asthma (n=75) found that asthma patients were more likely to respond better to salbutamol than to ipratropium [78].

Use of long-acting anticholinergics in asthma

Aclidinium

Aclidinium is licensed for use in COPD only [60]. At the time of writing, there were no registered clinical trials for aclidinium in asthma and so this anticholinergic will not be discussed further in this review.

Glycopyrronium

Glycopyrronium is also licensed for use in COPD only [61], but there have been studies assessing its use in asthma. In patients with mild-to-moderate asthma, glycopyrronium provided significantly more protection against methacholine-induced bronchoconstriction than placebo (p<0.002) [79]. Glycopyrronium also provided bronchodilation for up to 30 h after each inhalation [79]. There are currently two clinical trials assessing glycopyrronium use in patients with asthma: one study is assessing the bronchodilator effects and safety of two doses of glycopyrronium (25 µg and 50 µg) in adults with asthma receiving ICS/LABA (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT03137784; completion date: December 2017); the other study is assessing triple therapy of glycopyrronium, indacaterol and mometasone furoate in patients with uncontrolled asthma despite ICS/LABA treatment (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT03158311; estimated completion date: June 2019).

Umeclidinium

Umeclidinium is licensed for use in COPD, but is not approved for use in asthma [62, 80]. A phase II study found a modest improvement in trough FEV1 with umeclidinium monotherapy in patients with asthma not receiving ICS [81]. However, these improvements were not dose-related or consistent in magnitude, meaning that these data do not conclusively show a therapeutic benefit with umeclidinium monotherapy. Another phase II study evaluated the dose response, efficacy and safety of several doses of umeclidinium in combination with fluticasone furoate in patients with symptomatic asthma despite ICS therapy [82]. There was a significant improvement in trough FEV1 with the combination therapy (highest doses of umeclidinium bromide) compared with fluticasone furoate alone (p=0.018) [82]. There are currently two ongoing clinical trials assessing fixed-dose combination of umeclidinium, fluticasone furoate and vilanterol in patients with asthma (ClinicalTrials.gov identifiers NCT03184987 and NCT02924688; estimated completion dates: June 2019 and February 2019, respectively).

Tiotropium

Tiotropium is licensed for use in COPD as maintenance therapy, and in asthma as add-on therapy to ICS/LABA in adults, adolescents and children aged ≥6 years [63, 83]. In February 2017, the US Food and Drug Administration approved tiotropium Respimat for use in children with asthma aged ≥6 years [83]. There is an extensive clinical trial programme assessing the use of tiotropium in adults, adolescents and children with asthma. Tiotropium 5 µg added on to at least ICS and LABA therapy in adult patients with poorly controlled symptomatic asthma resulted in an improvement of up to 154 mL in peak FEV1 (p<0.001), with a 21% risk reduction for severe asthma exacerbation (p=0.03) [84]. A subgroup analysis also reported a reduced risk of severe asthma exacerbations, asthma worsening and improved asthma control responder rate regardless of baseline clinical features (sex, age, body mass index, disease duration, age of onset and smoking status) [85]. A pooled safety analysis of seven randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies (both phase II and III) found that both 2.5 and 5 µg doses of tiotropium had comparable safety and tolerability with placebo; the frequencies of patients reporting any type of adverse effect were 57.1% versus 55.1% and 60.8% versus 62.5%, respectively [86]. Several studies in adolescents and children have also shown significant improvements in lung function, with a comparable safety profile to placebo [87–91]. Overall, these data show that tiotropium is efficacious and has a favourable safety profile across a range of asthma severities in adults, adolescents and children [19, 84–89, 92, 93].

Who can benefit from long-acting anticholinergics?

There are limited step-up treatment options for patients who continue to have frequent symptoms and exacerbations while taking combination ICS/LABA treatment [94]. In addition, there are safety concerns for regular use of β2-agonists in some patients, particularly those with the SNP in the β2-adrenergic receptor gene ADRB2 genotype [76, 95]. Some patients may associate ICSs with systemic side-effects, particularly in children, such as reduced bone density and growth [96]. Long-acting anticholinergics can be a suitable add-on therapy for patients who remain symptomatic despite ICS and LABA therapy or who are unable to receive conventional therapies. The benefits seen with tiotropium add-on therapy in the subgroup analysis in patients with poorly controlled symptomatic asthma also suggest that a broad range of patients can benefit from anticholinergics, irrespective of baseline characteristics [85].

Conclusions

Acetylcholine plays an important role in the pathophysiology of asthma via binding to airway muscarinic receptors to trigger bronchoconstriction, mucus secretion and inflammation, while pre-clinical data have highlighted the importance of cholinergic-mediated bronchoconstriction in airway remodelling. Anticholinergics antagonise the parasympathetic effects of acetylcholine, thus providing therapeutic benefit via a supplementary mechanism to ICS and LABA effects in asthma. Clinical data have shown that long-acting anticholinergics are well tolerated, with infrequent and mild side-effects. The extensive clinical trial data of tiotropium, particularly in asthma studies, demonstrate clinical efficacy and treatment benefit as an add-on therapy in symptomatic asthma across a range of age groups and asthma severities.

Future studies are needed, however, to clarify the cholinergic control of asthma pathophysiology in more detail. In particular, areas that require further investigation are neuronal plasticity in asthma and its contribution to airway hyperresponsiveness and remodelling; the anti-inflammatory effects of anticholinergics in asthma patients; and the mechanisms that underpin the cholinergic control of airway inflammation and remodelling, in particular Th2-type inflammation and bronchoconstriction-induced remodelling.

Acknowledgements

Some of the items in this review are due to the generous support of Johan Karlberg (Humanity and Health Research Centre, Hong Kong) via his e-publication, Clinical Trials Magnifier Weekly (www.clinicaltrialmagnifier.org). Editorial support (in the form of writing assistance, assembling tables and figures, collating author comments, grammatical editing and referencing) was provided by Parveena Laskar at SciMentum (a Nucleus Global company, Manchester, UK), funded by Boehringer Ingelheim.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: R. Gosens reports grants from Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, Aquilo and Novartis, and editorial support (in the form of writing assistance, assembling tables and figures, collating author comments, grammatical editing and referencing) from Boehringer Ingelheim, during the conduct of the study.

Conflict of interest: N. Gross reports editorial support (in the form of writing assistance, assembling tables and figures, collating author comments, grammatical editing and referencing) from Boehringer Ingelheim, during the conduct of the study.

References

- 1.Kolahian S, Gosens R. Cholinergic regulation of airway inflammation and remodelling. J Allergy 2012; 2012: 681258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gosens R, Zaagsma J, Meurs H, et al. Muscarinic receptor signaling in the pathophysiology of asthma and COPD. Respir Res 2006; 7: 73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kistemaker LE, Gosens R. Acetylcholine beyond bronchoconstriction: roles in inflammation and remodeling. Trends Pharmacol Sci 2015; 36: 164–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scott GD, Fryer AD. Role of parasympathetic nerves and muscarinic receptors in allergy and asthma. Chem Immunol Allergy 2012; 98: 48–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buels KS, Fryer AD. Muscarinic receptor antagonists: effects on pulmonary function. Handb Exp Pharmacol 2012; 208: 317–341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Quirce S, Dominguez-Ortega J, Barranco P. Anticholinergics for treatment of asthma. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol 2015; 25: 84–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xue A, Wang J, Sieck GC, et al. Distribution of major basic protein on human airway following in vitro eosinophil incubation. Mediators Inflamm 2010; 2010: 824362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barnes P. Muscarinic receptor subtypes in airways. Eur Respir J 1993; 6: 328–331. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sawatzky DA, Kingham PJ, Court E, et al. Eosinophil adhesion to cholinergic nerves via ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 and associated eosinophil degranulation. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2002; 282: L1279–L1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coulson FR, Fryer AD. Muscarinic acetylcholine receptors and airway diseases. Pharmacol Ther 2003; 98: 59–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Minette PA, Lammers JW, Dixon CM, et al. A muscarinic agonist inhibits reflex bronchoconstriction in normal but not in asthmatic subjects. J Appl Physiol 1989; 67: 2461–2465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jacoby DB, Gleich GJ, Fryer AD. Human eosinophil major basic protein is an endogenous allosteric antagonist at the inhibitory muscarinic M2 receptor. J Clin Invest 1993; 91: 1314–1318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nie Z, Scott GD, Weis PD, et al. Role of TNF-alpha in virus-induced airway hyperresponsiveness and neuronal M2 muscarinic receptor dysfunction. Br J Pharmacol 2011; 164: 444–452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wicher SA, Lawson KL, Jacoby DB, et al. Ozone-induced eosinophil recruitment to airways is altered by antigen sensitization and tumor necrosis factor-alpha blockade. Physiol Rep 2017; 5: e13538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pan J, Rhode HK, Undem BJ, et al. Neurotransmitters in airway parasympathetic neurons altered by neurotrophin-3 and repeated allergen challenge. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2010; 43: 452–457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Foster EL, Simpson EL, Fredrikson LJ, et al. Eosinophils increase neuron branching in human and murine skin and in vitro. PLoS One 2011; 6: e22029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aven L, Paez-Cortez J, Achey R, et al. An NT4/TrkB-dependent increase in innervation links early-life allergen exposure to persistent airway hyperreactivity. FASEB J 2014; 28: 897–907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Andiappan AK, Parate PN, Anantharaman R, et al. Genetic variation in BDNF is associated with allergic asthma and allergic rhinitis in an ethnic Chinese population in Singapore. Cytokine 2011; 56: 218–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kerstjens HA, Casale TB, Bleecker ER, et al. Tiotropium or salmeterol as add-on therapy to inhaled corticosteroids for patients with moderate symptomatic asthma: two replicate, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, active-comparator, randomised trials. Lancet Respir Med 2015; 3: 367–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Santing RE, Pasman Y, Olymulder CG, et al. Contribution of a cholinergic reflex mechanism to allergen-induced bronchial hyperreactivity in permanently instrumented, unrestrained guinea-pigs. Br J Pharmacol 1995; 114: 414–418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Allen IC, Hartney JM, Coffman TM, et al. Thromboxane A2 induces airway constriction through an M3 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor-dependent mechanism. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2006; 290: L526–L533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Raemdonck K, de Alba J, Birrell MA, et al. A role for sensory nerves in the late asthmatic response. Thorax 2012; 67: 19–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smit M, Zuidhof AB, Bos SI, et al. Bronchoprotection by olodaterol is synergistically enhanced by tiotropium in a guinea pig model of allergic asthma. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2014; 348: 303–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jabbal S, Manoharan A, Lipworth BJ. Bronchoprotective tolerance with indacaterol is not modified by concomitant tiotropium in persistent asthma. Clin Exp Allergy 2017; 47: 1239–1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ramnarine SI, Haddad EB, Khawaja AM, et al. On muscarinic control of neurogenic mucus secretion in ferret trachea. J Physiol 1996; 494: 577–586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rogers DF. Motor control of airway goblet cells and glands. Respir Physiol 2001; 125: 129–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grainge CL, Lau LC, Ward JA, et al. Effect of bronchoconstriction on airway remodeling in asthma. N Engl J Med 2011; 364: 2006–2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kistemaker LE, Hiemstra PS, Bos IS, et al. Tiotropium attenuates IL-13-induced goblet cell metaplasia of human airway epithelial cells. Thorax 2015; 70: 668–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Komiya K, Kawano S, Suzaki I, et al. Tiotropium inhibits mucin production stimulated by neutrophil elastase but not by IL-13. Pulm Pharmacol Ther 2018; 48: 161–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Montalbano AM, Albano GD, Bonanno A, et al. Autocrine acetylcholine, induced by IL-17A via NFkappaB and ERK1/2 pathway activation, promotes MUC5AC and IL-8 synthesis in bronchial epithelial cells. Mediators Inflamm 2016; 2016: 9063842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kistemaker LE, Bos ST, Mudde WM, et al. Muscarinic M3 receptors contribute to allergen-induced airway remodeling in mice. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2014; 50: 690–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bos IS, Gosens R, Zuidhof AB, et al. Inhibition of allergen-induced airway remodelling by tiotropium and budesonide: a comparison. Eur Respir J 2007; 30: 653–661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.John-Schuster G, de Kleijn S, van Wijck Y, et al. The effect of tiotropium in combination with olodaterol on house dust mite-induced allergic airway disease. Pulm Pharmacol Ther 2017; 45: 210–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mailhot-Larouche S, Deschenes L, Gazzola M, et al. Repeated airway constrictions in mice do not alter respiratory function. J Appl Physiol 2018; 124: 1483–1490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Koyama S, Sato E, Nomura H, et al. Acetylcholine and substance P stimulate bronchial epithelial cells to release eosinophil chemotactic activity. J Appl Physiol 1998; 84: 1528–1534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Costello RW, Schofield BH, Kephart GM, et al. Localization of eosinophils to airway nerves and effect on neuronal M2 muscarinic receptor function. Am J Physiol 1997; 273: L93–L103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gori S, Vermeulen M, Remes-Lenicov F, et al. Acetylcholine polarizes dendritic cells toward a Th2-promoting profile. Allergy 2017; 72: 221–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Oenema TA, Kolahian S, Nanninga JE, et al. Pro-inflammatory mechanisms of muscarinic receptor stimulation in airway smooth muscle. Respir Res 2010; 11: 130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bühling F, Lieder N, Kuhlmann UC, et al. Tiotropium suppresses acetylcholine-induced release of chemotactic mediators in vitro. Respir Med 2007; 101: 2386–2394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Damera G, Jiang M, Zhao H, et al. Aclidinium bromide abrogates allergen-induced hyperresponsiveness and reduces eosinophilia in murine model of airway inflammation. Eur J Pharmacol 2010; 649: 349–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Toumpanakis D, Loverdos K, Tzouda V, et al. Tiotropium bromide exerts anti-inflammatory effects during resistive breathing, an experimental model of severe airway obstruction. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2017; 12: 2207–2220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ohta S, Oda N, Yokoe T, et al. Effect of tiotropium bromide on airway inflammation and remodelling in a mouse model of asthma. Clin Exp Allergy 2010; 40: 1266–1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kistemaker LE, Bos IS, Menzen MH, et al. Combination therapy of tiotropium and ciclesonide attenuates airway inflammation and remodeling in a guinea pig model of chronic asthma. Respir Res 2016; 17: 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Moriyama M, Fukuyama S, Inoue H, et al. The neuropeptide neuromedin U activates eosinophils and is involved in allergen-induced eosinophilia. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2006; 290: L971–L977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wallrapp A, Riesenfeld SJ, Burkett PR, et al. The neuropeptide NMU amplifies ILC2-driven allergic lung inflammation. Nature 2017; 549: 351–356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Klose CSN, Mahlakoiv T, Moeller JB, et al. The neuropeptide neuromedin U stimulates innate lymphoid cells and type 2 inflammation. Nature 2017; 549: 282–286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Grainge C, Dennison P, Lau L, et al. Asthmatic and normal respiratory epithelial cells respond differently to mechanical apical stress. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2014; 190: 477–480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dekkers BG, Maarsingh H, Meurs H, et al. Airway structural components drive airway smooth muscle remodeling in asthma. Proc Am Thorac Soc 2009; 6: 683–692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hoshino M, Ohtawa J, Akitsu K. Effects of the addition of tiotropium on airway dimensions in symptomatic asthma. Allergy Asthma Proc 2016; 37: 147–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gosens R, Dueck G, Rector E, et al. Cooperative regulation of GSK-3 by muscarinic and PDGF receptors is associated with airway myocyte proliferation. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2007; 293: L1348–L1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Oenema TA, Smit M, Smedinga L, et al. Muscarinic receptor stimulation augments TGF-beta1-induced contractile protein expression by airway smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2012; 303: L589–L597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Oenema TA, Mensink G, Smedinga L, et al. Cross-talk between transforming growth factor-beta1 and muscarinic M2 receptors augments airway smooth muscle proliferation. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2013; 49: 18–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Oenema TA, Maarsingh H, Smit M, et al. Bronchoconstriction induces TGF-beta release and airway remodelling in guinea pig lung slices. PLoS One 2013; 8: e65580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Aschner Y, Downey GP. Transforming growth factor-beta: master regulator of the respiratory system in health and disease. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2016; 54: 647–655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tatler AL, John AE, Jolly L, et al. Integrin alphavbeta5-mediated TGF-beta activation by airway smooth muscle cells in asthma. J Immunol 2011; 187: 6094–6107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Noble PB, Pascoe CD, Lan B, et al. Airway smooth muscle in asthma: linking contraction and mechanotransduction to disease pathogenesis and remodelling. Pulm Pharmacol Ther 2014; 29: 96–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gosens R, Grainge C. Bronchoconstriction and airway biology: potential impact and therapeutic opportunities. Chest 2015; 147: 798–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Busse WW, Dahl R, Jenkins C, et al. Long-acting muscarinic antagonists: a potential add-on therapy in the treatment of asthma? Eur Respir Rev 2016; 25: 54–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Accord UK. Ipratropium Bromide 250 micrograms/1ml and 500 micrograms/2ml Nebuliser Solution. Summary of Product Characteristics 2010. www.medicines.org.uk/emc/medicine/27927 Date last updated: June 22, 2015. Date last accessed: November 16, 2017.

- 60.AstraZeneca UK. Eklira Genuair 322 micrograms Inhalation Powder. Summary of Product Characteristics 2012. www.medicines.org.uk/emc/medicine/27001 Date last updated: April 20, 2017. Date last accessed: May 2, 2017.

- 61.Novartis Pharmaceuticals UK. Seebri Breezhaler Inhalation Powder, Hard Capsules 44mcg. Summary of Product Characteristics 2012. www.medicines.org.uk/emc/medicine/27138 Date last updated: July 19, 2017. Date last accessed: August 8, 2017.

- 62.GlaxoSmithKline UK. Incruse Ellipta 55 micrograms Inhalation Powder, Pre-dispensed. Summary of Product Characteristics 2014. www.medicines.org.uk/emc/medicine/29394 Date last accessed: July 20, 2017.

- 63.Boehringer Ingelheim Ltd. Spiriva Respimat 2.5 microgram, Inhalation Solution. Summary of Product Characteristics 2017. www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/407/smpc Date last accessed: April 30, 2018.

- 64.Gavalda A, Miralpeix M, Ramos I, et al. Characterization of aclidinium bromide, a novel inhaled muscarinic antagonist, with long duration of action and a favorable pharmacological profile. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2009; 331: 740–751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Casarosa P, Bouyssou T, Germeyer S, et al. Preclinical evaluation of long-acting muscarinic antagonists: comparison of tiotropium and investigational drugs. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2009; 330: 660–668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bulkhi A, Tabatabaian F, Casale TB. Long-acting muscarinic antagonists for difficult-to-treat asthma: emerging evidence and future directions. Drugs 2016; 76: 999–1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Salmon M, Luttmann MA, Foley JJ, et al. Pharmacological characterization of GSK573719 (umeclidinium): a novel, long-acting, inhaled antagonist of the muscarinic cholinergic receptors for treatment of pulmonary diseases. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2013; 345: 260–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Peters SP, Kunselman SJ, Icitovic N, et al. Tiotropium bromide step-up therapy for adults with uncontrolled asthma. N Engl J Med 2010; 363: 1715–1726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Price D, Fromer L, Kaplan A, et al. Is there a rationale and role for long-acting anticholinergic bronchodilators in asthma? NPJ Prim Care Respir Med 2014; 24: 14023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Calzetta L, Matera MG, Cazzola M. Pharmacological interaction between LABAs and LAMAs in the airways: optimizing synergy. Eur J Pharmacol 2015; 761: 168–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Fukunaga K, Kume H, Oguma T, et al. Involvement of Ca2+ signaling in the synergistic effects between muscarinic receptor antagonists and beta2-adrenoceptor agonists in airway smooth muscle. Int J Mol Sci 2016; 17: e1590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cazzola M, Calzetta L, Page CP, et al. Pharmacological characterization of the interaction between aclidinium bromide and formoterol fumarate on human isolated bronchi. Eur J Pharmacol 2014; 745: 135–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Cazzola M, Calzetta L, Segreti A, et al. Translational study searching for synergy between glycopyrronium and indacaterol. COPD 2015; 12: 175–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Calverley PM, Lee A, Towse L, et al. Effect of tiotropium bromide on circadian variation in airflow limitation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax 2003; 58: 855–860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Levin DC, Little KS, Laughlin KR, et al. Addition of anticholinergic solution prolongs bronchodilator effect of beta 2 agonists in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Med 1996; 100: 40S–48S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Restrepo RD. Use of inhaled anticholinergic agents in obstructive airway disease. Respir Care 2007; 52: 833–851. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.British Thoracic Society, Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. British Guideline on the Management of Asthma. A National Clinical Guideline. London, British Thoracic Society, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 78.van Schayck CP, Folgering H, Harbers H, et al. Effects of allergy and age on responses to salbutamol and ipratropium bromide in moderate asthma and chronic bronchitis. Thorax 1991; 46: 355–359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hansel TT, Neighbour H, Erin EM, et al. Glycopyrrolate causes prolonged bronchoprotection and bronchodilatation in patients with asthma. Chest 2005; 128: 1974–1979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ferrando M, Bagnasco D, Braido F, et al. Umeclidinium for the treatment of uncontrolled asthma. Expert Opin Investig Drugs 2017; 26: 761–766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lee LA, Briggs A, Edwards LD, et al. A randomized, three-period crossover study of umeclidinium as monotherapy in adult patients with asthma. Respir Med 2015; 109: 63–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lee LA, Yang S, Kerwin E, et al. The effect of fluticasone furoate/umeclidinium in adult patients with asthma: a randomized, dose-ranging study. Respir Med 2015; 109: 54–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.US Food and Drug Administration. Spiriva Respimat Prescribing Information, Revised 2017 2017. http://docs.boehringer-ingelheim.com/Prescribing%20Information/PIs/Spiriva%20Respimat/spirivarespimat.pdf Date last accessed: October 30, 2017.

- 84.Kerstjens HA, Engel M, Dahl R, et al. Tiotropium in asthma poorly controlled with standard combination therapy. N Engl J Med 2012; 367: 1198–1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kerstjens HA, Moroni-Zentgraf P, Tashkin DP, et al. Tiotropium improves lung function, exacerbation rate, and asthma control, independent of baseline characteristics including age, degree of airway obstruction, and allergic status. Respir Med 2016; 117: 198–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Dahl R, Kaplan A. A systematic review of comparative studies of tiotropium Respimat and tiotropium HandiHaler in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: does inhaler choice matter? BMC Pulm Med 2016; 16: 135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hamelmann E, Bernstein JA, Vandewalker M, et al. A randomised controlled trial of tiotropium in adolescents with severe symptomatic asthma. Eur Respir J 2017; 49: 1601100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Hamelmann E, Bateman ED, Vogelberg C, et al. Tiotropium add-on therapy in adolescents with moderate asthma: a 1-year randomized controlled trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2016; 138: 441–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Szefler SJ, Murphy K, Harper T III, et al. A phase III randomized controlled trial of tiotropium add-on therapy in children with severe symptomatic asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2017; 140: 1277–1287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Vogelberg C, Engel M, Laki I, et al. Tiotropium add-on therapy improves lung function in children with symptomatic moderate asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2018; in press [ 10.1016/j.jaip.2018.04.032]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Vrijlandt E, El Azzi G, Vandewalker M, et al. Safety and efficacy of tiotropium in 1–5-year-old children with persistent asthmatic symptoms: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Respir Med 2018; 6: 127–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Paggiaro P, Halpin DM, Buhl R, et al. The effect of tiotropium in symptomatic asthma despite low- to medium-dose inhaled corticosteroids: a randomized controlled trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2016; 4: 104–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Ohta K, Ichinose M, Tohda Y, et al. Long-term once-daily tiotropium Respimat® is well tolerated and maintains efficacy over 52 weeks in patients with symptomatic asthma in Japan: a randomised, placebo-controlled study. PLoS One 2015; 10: e0124109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA). Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention 2017. Available from: http://ginasthma.org/

- 95.Ortega VE, Hawkins GA, Moore WC, et al. Effect of rare variants in ADRB2 on risk of severe exacerbations and symptom control during longacting beta agonist treatment in a multiethnic asthma population: a genetic study. Lancet Respir Med 2014; 2: 204–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Pandya D, Puttanna A, Balagopal V. Systemic effects of inhaled corticosteroids: an overview. Open Respir Med J 2014; 8: 59–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]