Abstract

Background.

Considerable evidence from twin and adoption studies indicates that genetic and shared environmental factors play a role in the initiation of smoking behavior. Although twin and adoption designs are powerful to detect genetic and environmental influences, they do not provide information on the processes of assortative mating and parent-offspring transmission and their contribution to the variability explained by genetic and/or environmental factors.

Methods.

We examined the role of genetic and environmental factors in individual differences for smoking initiation using an extended kinship design. This design allows the simultaneous testing of additive and non-additive genetic, shared and individual-specific environmental factors, as well as sex differences in the expression of genes and environment in the presence of assortative mating and combined genetic and cultural transmission, while also estimating the regression of the prevalence of smoking initiation on age. A dichotomous lifetime ‘ever’ smoking measure was obtained from twins and relatives in the ‘Virginia 30,000’ sample and the ‘Australian 25,000’.

Results.

Results demonstrate that both genetic and environmental factors play a significant role in the liability to smoking initiation. Major influences on individual differences appeared to be additive genetic and unique environmental effects, with smaller contributions from assortative mating, shared sibling environment, twin environment, cultural transmission and resulting genotype-environment covariance. Age regression of the prevalence of smoking initiation was significant. The finding of negative cultural transmission without dominance led us to investigate more closely two possible mechanisms for the lower parent-offspring correlations compared to the sibling and DZ twin correlations in subsets of the data: (i) age × gene interaction, and (ii) social homogamy. Neither mechanism provided a significantly better explanation of the data.

Conclusions.

This study showed significant heritability, partly due to assortment, and significant effects of primarily non-parental shared environment on liability to smoking initiation.

Keywords: smoking initiation, extended twin kinship design, genetics, assortment, cultural transmission

Introduction

Smoking remains a serious public health problem. Briefly, tobacco is the second major cause of death in the world, killing 7 million people each year (World Health Organization 2018). In the US, cigarettes are estimated to be responsible for a third of all cancer deaths (> 85% of lung cancer deaths) and a third of deaths from cardiovascular disease (CDC 2018). In Australia, tobacco smoking increases the risk of cardiovascular disease incidence by between two- and four-fold (Cancer Council Victoria 2015). Smoking harms nearly every organ in the body, causing many diseases and reducing health in general (CDC 2018). The economic costs of tobacco use are equally devastating.

Considerable evidence exists that genetic and environmental factors play a significant role in the initiation of smoking initiation (see Maes & Neale, 2009, for a review). Other reviews of this literature have been published by Sullivan and Kendler (1997), Heath et al. (1998), Li et al. (2003) and Kaprio (2009). The evidence primarily stems from twin and adoption studies. In summary, of the more than 15 published adult twin studies of lifetime or current use of tobacco products (which we will term smoking initiation or SI), originating from seven different countries, estimates of the heritability (h2) of SI were generally high, with most values falling between 40 and 70% (median=57%). The unweighted mean (±SD) estimate of h2 for the 26 adult samples (males and females considered separately) was 0.56 ±.14. Estimates of the proportion of variance in liability due to shared environmental effects (c2) were more variable, with most ranging from 0 to 50%, and the unweighted mean (±SD) estimate was 0.22 ±.18. The unweighted mean estimate for individual-specific environmental effects (e2) was 0.22 (±.13). These conclusions are also supported by studies of twins reared apart and adoption studies of smoking (Eaves & Eysenck, 1980, Kendler et al., 2000). Two studies compared heritability estimates across a range of ages/birth cohorts, gender and cultures (US and Australia, Heath et al. 1993; Australia, Sweden and Finland, Madden et al. 2004). While the early study found some significant differences in heritability across cultures, the second reported remarkable consistency of estimates. To our knowledge, no other study including twin and other relatives has undertaken a cross-cultural comparison of average smoking habits and the role of genes and environment in individual differences.

Although a number of studies have reported associations between the smoking initiation of parents and that of their children, these studies typically are not informative about the relative contributions of genes and environment. One study used a twin-parent model for smoking to estimate the degree of assortment and the role of genetic versus cultural transmission (Boomsma et al. 1994). They found that the correlation between spouses for ‘ever smoked’ was rather low (0.18) and that the parent-offspring resemblance could be accounted for completely by their genetic relatedness. Another study included correlations for twins and their parents (including a spousal correlation of 0.42) but did not model them explicitly (Kaprio et al. 1995). An earlier report on analyses of the Virginia 30,000 sample used the extended twin (ET) kinship model (Maes et al. 2006) to analyze data collected on twins, their spouses and first-degree relatives. This ET design allows the simultaneous testing of additive and non-additive genetic, shared and individual-specific environmental factors, as well as sex differences in the expression of genes and environment in the presence of assortative mating and combined genetic and cultural transmission.

In this paper, we will attempt to replicate these results using an ET design in a comparably large sample from Australia, and compare the role of genetic and environmental factors for smoking initiation with those in the Virginia sample. First, we estimated the correlations between relatives and consider their overall pattern across the different types of relative. Second, we fit a model to the data for the purpose of formal hypothesis testing. These analyses are undertaken for both the US and OZ sample separately, as well as for the combined sample to test the equality of the estimates across samples.

Materials and Methods

The data used in this study come from two large epidemiological samples: the United States sample comprises 25,861 respondents and the Australian sample comprises 24,457 respondents who completed a self-report mailed questionnaire and answered questions about smoking behavior. Both samples are based on twins, and include their spouses and their first-degree relatives (i.e. parents, siblings, and offspring). Within the ET family structure in this study there are 88 unique sex-specific biological and social relationships. Zygosity of twins was determined on the basis of responses to standard questions about similarity and the degree to which others confused them in both samples. This method has been shown to give at least 95% agreement with diagnosis based on extensive blood typing (Martin & Martin 1974, Eaves et al. 1989; Ooki et al. 1990).

The ‘Virginia 30,000’

The Virginia sample contains data from 14,763 twins, ascertained from two sources (Eaves et al. 1999; Truett et al. 1994). Public birth records and other public records in the Commonwealth of Virginia were used to obtain current address information for twins born in Virginia between 1915 and 1971, with questionnaires mailed to twins who had returned at least one questionnaire in previous surveys. A second group of twins was identified through their response to a letter published in the newsletter of the American Association of Retired Persons (AARP, 9476 individuals). Twins participating in the study were mailed a 16 page “Health and Lifestyles” questionnaire, and were asked to supply the names and addresses of their spouses, siblings, parents and children for the follow-up study of relatives of twins. Completed questionnaires were obtained from 69.8% of twins invited to participate in the study, which was carried out between 1986 and 1989. The original twin questionnaire was modified slightly to provide two additional forms, one appropriate for the parents of twins and another for the spouses, children and siblings of twins. Modifications affected only those aspects of the questionnaire related to twinning. The response rate from relatives (44.7%) was much lower than that from the twins. Of the complete sample of 28,492 individuals (from 8567 extended kinships), 58% were female, with 50% of respondents under 50 years of age.

The ‘Australian 25,000’

The Australian sample was ascertained through two cohorts of twins. The first cohort was recruited in 1980–82 from a sampling frame which comprised 5,967 twin pairs aged 18 years or older (born 1893 to 1964) then enrolled in the Australian NHMRC Twin Registry (ATR). Responses were obtained from 3,808 complete pairs (64%; Jardine et al., 1984) and these were followed up with a second mailed questionnaire in 1988–90 with responses from 2,708 complete pairs (Heath et al., 1994) and 337 incomplete pairs (81% of those still contactable). In this follow-up questionnaire, twins were asked to provide the names of parents, siblings, spouses, and children who would be prepared to answer similar mailed questionnaires. The second cohort of twins, born 1964–71, was recruited from the ATR in 1989 and were mailed similar questionnaires in 1989–91 with responses from 3,769 individuals from 4,269 eligible pairs. This cohort was also asked to provide names of relatives who were prepared to fill in questionnaires. In total, names of 14,421 relatives were provided for Cohort 1, and 4,999 names for Cohort 2. A suitably modified version of the questionnaire was prepared for parents, and another version for siblings, spouses and children of twins. These were mailed out during the period 1989–91 and respectively 8601 (60%) and 2799 (56%) of relatives from Cohorts 1 and 2 returned questionnaires (response rates varied with type of relative, from 65% for mothers to 56% for siblings). There was vigorous follow-up of non-responding twins (up to 5 phone calls) but somewhat less assiduous follow-up of relatives (up to two phone calls).

Table 1 breaks down the sample sizes for SI by type of relative and sex, as well as by zygosity for the twins only. There are some differences in the breakdown between the two samples. The United States sample has proportionally fewer parents and siblings and more spouses and offspring than the Australian sample, probably reflecting the older age of the US sample.

Table 1:

Age-adjusted prevalence rates for smoking initiation and sample sizes by sex and type of relative

| Males | Twins | Husbands | Fathers | Brothers | Sons | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MZ | DZ | DZO | MZ | DZ | DZO | ||||

| US | 0.52 | 0.52 | 0.58 | 0.56 | 0.6 | 0.53 | 0.72 | 0.55 | 0.5 |

| N | 1593 | 1189 | 1370 | 2076 | 1343 | 376 | 781 | 1021 | 1607 |

| OZ | 0.50 | 0.54 | 0.52 | 0.62 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.71 | 0.6 | 0.44 |

| N | 1671 | 1188 | 1298 | 1979 | 1282 | 230 | 1417 | 1479 | 643 |

| Females | Twins | Wives | Mothers | Sisters | Daughters | ||||

| MZ | DZ | DZO | MZ | DZ | DZO | ||||

| US | 0.423 | 0.45 | 0.44 | 0.38 | 0.43 | 0.53 | 0.47 | 0.47 | 0.51 |

| N | 3801 | 2433 | 1350 | 635 | 718 | 469 | 1182 | 1527 | 2390 |

| OZ | 0.45 | 0.5 | 0.59 | 0.43 | 0.39 | 0.47 | 0.37 | 0.45 | 0.46 |

| N | 3176 | 2080 | 1247 | 1094 | 732 | 254 | 1893 | 1909 | 885 |

Measures

Participants in both studies completed a questionnaire covering a range of health and lifestyle issues and including almost identical questions about their smoking behavior. Self-report data on smoking were obtained from three items. Respondents were asked to indicate the number corresponding to the frequency which best described their smoking habits during their lifetime. The four possible response values were: ‘never smoked’, ‘used to smoke but gave it up’, ‘smoked on and off’, ‘smoked most of your life’. Smoking quantity was measured as the number which expressed their best estimate of the DAILY cigarette consumption (or equivalent in pipefuls or cigars) during their lifetime, with six response categories: ‘never’, ‘1–5 per day’, ‘5–10 per day’, ‘11–20 per day’, ‘21–40 per day’, ‘>40 per day’. Age of onset was recorded as the age at which they started smoking. Based on these three variables, we created a dichotomous variable, ‘smoking initiation’, reflecting whether they had ever smoked or not. If they responded “never smoked” to the smoking frequency question and “never” to the smoking quantity question and did not report an age of onset for smoking, they were coded zero on the dichotomous smoking variable. If on the other hand, they reported any of the other three response categories for smoking frequency OR any of the other five categories for smoking quantity OR an age of onset, they were coded one. Responses were consistent across the three variables for >85% of the sample. About 10% of the sample was coded a smoker based on two out of three variables. In less than 1% of the sample was someone coded a smoker on the basis of only one of these three variables. Another ~1% were assigned missing values for the dichotomous smoking variable.

Statistical methods

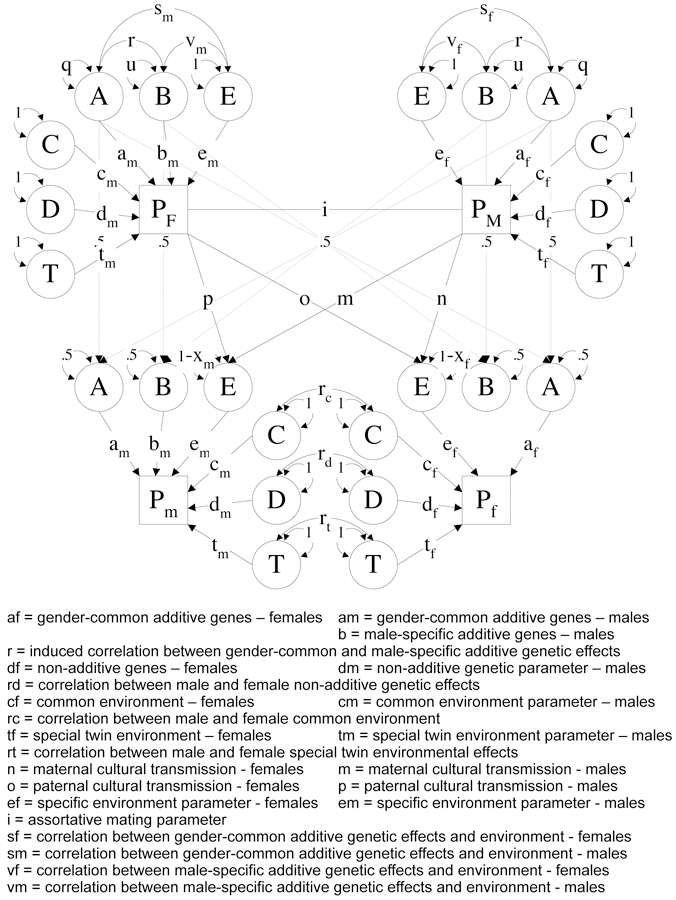

Structural modeling of the data was undertaken using methods described in Eaves et al. (1999), Truett et al. (1994) and Lake et al. (2000), which assess the contributions of genetic and environmental effects in the presence of assortative mating. The ET model, which is an extension of the ACE model (Neale and Cardon 1992) is described in more detail in Maes et al. (2006). Briefly, genetic effects can be either i) additive or ii) dominant. Besides unique environmental factors, three sources of shared environmental influences can be distinguished : i) shared (sibling) environment, ii) twin environment, and iii) cultural transmission. The latter is modeled as vertical cultural transmission from parent to child, and reflects the non-genetic impact of the parent’s phenotype on the environment of their children. The correlation between spouses is assumed to result from phenotypic assortment which occurs when mate selection is based at least partly on the trait being studied. The contribution of the genetic and environmental factors may be dependent upon sex, both in their magnitude and nature. Figure I presents a path diagram of the ET model. Note that only two generations are shown as all the model parameters can be depicted with drawing just an opposite-sex pair of twins and their parents. The model was implemented in the statistical modeling package Mx (Neale et al. 2006) and OpenMx (Boker et al. 2010, Neale et al. 2017) and fit to the raw ordinal data to obtain maximum likelihood estimates of the model parameters, allowing the inclusion of covariates such as age to the model. We included age regression on the thresholds by sex based on results from prior analyses of the US sample (Maes et al. 2006). As a result of the additional complexity of the model, we opted to include a maximum of two siblings and children of twins, leading to a minor reduction of the total sample size by about 1%. A detailed description of the Mx specification of the ET model is given in Maes et al. (1999).

Figure I:

Full extended family resemblance model for opposite-sex DZ twins and their parents. Path coefficients are the same in both generations, and gene-gene and gene-environment correlations occur in both generations (dominance, shared environment and twin environment not shown for the parental generation)

Prior to the fitting the ET model to the data of the two samples, the thresholds for each of the relatives and the correlations for the 88 sex-specific relationships were estimated in OpenMx by maximum likelihood. Using this approach, we obtain unbiased estimates of the parameters if missing observations are missing at random (Little & Rubin 1978). We evaluated whether the thresholds could be equated across twin order, generation and gender. Furthermore, we tested gender heterogeneity of the correlations within each category of social and biological relatedness, both separately and combined. OpenMx scripts are available upon request.

Results

Response frequencies

Prevalence rates for smoking initiation are presented in Table 1, by sex, country and type of relative. We systematically tested the equality of thresholds across twin order, zygosity, generation, sex and country, while allowing age as a covariate. Prevalence rates for the two members of twin pairs, for the spouses of the two twins and the children of twins could be equated within each sample, as could rates for first-degree relatives (i.e. fathers, brothers , etc.) across zygosity. However, rates could not be equated for twins and spouses across zygosity, or for relatives within generations (twins, spouses, siblings) or across generations (parents, twins, children of twins) without significant loss of fit (results not shown). Furthermore, prevalence rates were significantly different between the two samples, but not consistently in one direction. This might be due to the relatively large sample sizes to test for threshold (mean) differences. However, the marked difference between smoking initiation of men and women was consistent with higher prevalence rates in men for all types of relative except the children of twins. Finally, a decrease in prevalence of smoking initiation over three generations (fathers versus twins/ husbands/brothers versus sons) was apparent for males, but not females, consistent with reported epidemiological trends for smoking initiation in males and females.

Maximum likelihood estimation of thresholds and correlations

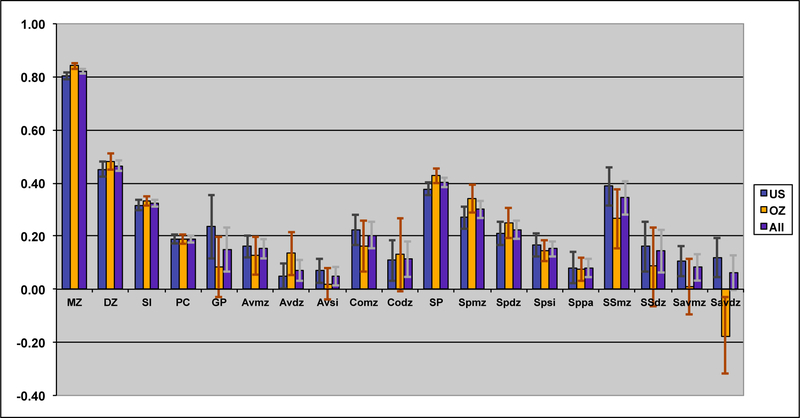

Tetrachoric correlations for all the 88 sex-specific relationships were estimated by maximum likelihood, properly accounting for the dependency of the observations of relatives. Figure II shows the maximum likelihood estimates of the tetrachoric correlations separately for each sample as well as a combined estimate by equating the correlations within category of biological/social relationship across sample. Confidence intervals were obtained by calculating the standard errors of the z-transformed values. The respective 88 correlations could be constrained across the two samples (−2LL for US=30022.48; for OZ=26997.31; and US=OZ=57090.71) without loss of fit (χ288=70.92, p=.91), when allowing the thresholds to differ by sample, which is remarkable given the power associated with the large sample sizes. In the combined analyses, 4 out of 18 gender heterogeneity tests were significant, including the parent-offspring pairs, siblings and DZ twins (see Table 2). This appeared to be primarily driven by lower correlations between opposite sex pairings than between same sex pairings, which could be indicative of sex limitation. Note that these were the categories with the largest number of pairs of relative.

Figure II:

Maximum likelihood correlations for smoking behavior in the VA30,000 and OZ25k, grouped by degree of genetic and environmental similarity, constrained to be equal across sex.

Table 2:

Comparison of FIML correlations for smoking initiation in the VA& OZ sample

| US | OZ | All | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| df | χ2 | p | χ2 | p | χ2 | p | |

| equate parent-offspring | 3 | 19.13 | 0 | 51.11 | 0 | 17.2 | 0 |

| equate twin-parent in law | 3 | 1.92 | 0.59 | 50.44 | 0 | 4.24 | 0.24 |

| equate siblings | 2 | 28.69 | 0 | 40.08 | 0 | 89.63 | 0 |

| equate sibs and spouse of twin | 3 | 1.54 | 0.67 | 4.02 | 0.26 | 4.85 | 0.18 |

| equate grandparents-children | 7 | 1.83 | 0.97 | 6.4 | 0.49 | 6.59 | 0.47 |

| equate avuncular through MZ twins | 3 | 4.81 | 0.19 | 53.63 | 0 | 3.99 | 0.26 |

| equate avuncular through DZ twins | 7 | 49.27 | 0 | 3.73 | 0.81 | 8.4 | 0.3 |

| equate avuncular through sibs | 7 | 6.27 | 0.51 | 10.15 | 0.18 | 12.6 | 0.08 |

| equate avuncular inlaws through MZ twins | 3 | 3.19 | 0.36 | −5.22 | 1.69 | 0.64 | |

| equate avuncular inlaws through DZ twins | 7 | 3.82 | 0.8 | 4.6 | 0.71 | 2.82 | 0.9 |

| equate cousins through MZ twins | 5 | 1.25 | 0.94 | 7.85 | 0.17 | 3.47 | 0.63 |

| equate cousins through DZ twins | 9 | 7.48 | 0.59 | 7.1 | 0.63 | 10.47 | 0.31 |

| equate spouse w MZ co-twin | 1 | 2.07 | 0.15 | −0.09 | 1.45 | 0.23 | |

| equate spouse w DZ co-twin | 3 | 0.78 | 0.86 | 3.51 | 0.32 | 2.24 | 0.52 |

| equate spouse w spouse MZ twin | 1 | 2.85 | 0.09 | 1.84 | 0.17 | 5.87 | 0.02 |

| equate spouse w spouse DZ twin | 2 | 2.61 | 0.27 | 0.34 | 0.85 | 2.73 | 0.26 |

| equate MZ twins | 1 | 1.16 | 0.28 | 2 | 0.16 | 0.12 | 0.73 |

| equate DZ twins | 2 | 16.48 | 0 | 11.57 | 0 | 27.65 | 0 |

| equate all correlations by sex | 69 | 107.13 | 0 | 97.48 | 0.01 | 151.38 | 0 |

bold indicates significant difference in correlations by sex

The observed pattern of correlations for smoking initiation was consistent with additive genetic influences, with no evidence for dominance effects. The correlations further suggested small contributions of non-parental shared environmental factors and, possibly, special twin environment, due to the elevated DZ correlation compared to the sibling correlation. There was no evidence for cultural transmission; on the contrary, the pattern of correlations might be more consistent with negative cultural transmission because parent-offspring correlations were smaller (rather than greater) than might be expected from genetic factors alone. The spousal correlation for SI was highly significant, suggesting some form of assortment. The pattern of correlations through marriage observed for smoking initiation was consistent with both a genetic contribution to smoking initiation and assortative mating.

Maximum likelihood estimation of genetic and environmental contributions

We fitted the full ET model first, separately to each of the samples (US, OZ) and then to both samples simultaneously, constraining the genetic and environmental parameters across the samples while allowing the thresholds to differ between the samples. The minus twice the log-likelihood of the data was 30107.73 for the US sample, 27072.37 for the OZ sample and 57195.25 for the combined analyses, indicating a non-significant result for the cross-cultural comparison (χ229=15.15, p=.98).

The full ET model allows for both qualitative (different factors in males and females, also referred to as non-scalar sex limitation) and quantitative (different magnitude of effects in males and females, also referred to as scalar sex limitation) sex differences of all the sources of variance. Although separately, none of the individual tests for qualitative sex differences in variance components was significant (additive genetic, dominance genetic, shared environment, twin environment, cultural transmission between opposite sexes from father or mother) the combined test was just significant (χ26=13.4, p=.04). Similarly, none of the individual tests for quantitative sex differences was significant, nor was the combined test for all the genetic parameters or all the environmental parameters when allowing qualitative sex differences. However, some of these tests became significant after eliminating all qualitative sex differences, except cultural transmission sex differences). The overall test for sex differences in genetic and environmental parameters was highly significant (χ212=80.6, p=.00).

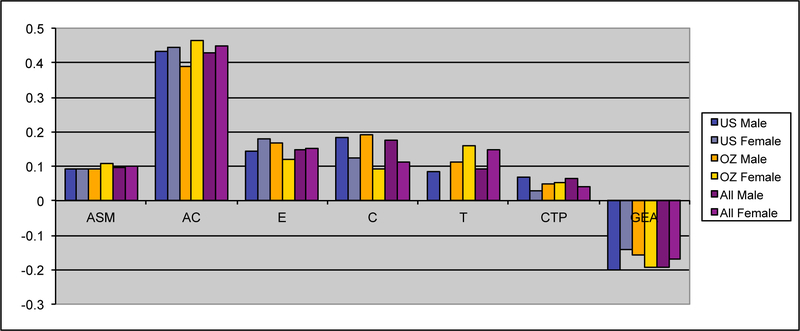

This set of results suggested that the model might be overparameterized with highly correlated parameters. Eliminating whole sets of parameters, (i.e. male and female non-parental shared environmental parameters and male-female shared environmental correlation) resulted in very comparable results across samples (see Table 3). Non-parental shared environment, special twin environment, and assortment could not be dropped without significant loss of fit. On the other hand, cultural transmission, additive genetic factors or dominance factors by themselves could be dropped. However, test for overall genetic effects (additive and dominance; χ26=85.6, p=.00) or overall shared environmental effects (non-parental shared environment, special twin environment and cultural transmission; χ210=69.8, p=.00) were highly significant, as was the test for familial resemblance (χ216=1654.9, p=.00). When dominance parameters were constrained to zero, and the male-female genetic (rd and rg) correlations were fixed to one (the latter by dropping the male-specific additive genetic parameters), results for the two samples were remarkably close. Furthermore, additive genetic factors and cultural transmission were then significant (see also Table 3).

Table 3:

Model fitting results for fitting the extended twin (ET) model and submodels to smoking initiation in the VA & OZ sample

| US | OZ | All | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| df | χ2 | p | χ2 | p | χ2 | p | |

| full ET model | |||||||

| no assortment | 1 | 249.1 | 0 | 368 | 0 | 506 | 0 |

| no non-parental shared environment | 3 | 25.5 | 0 | 29.4 | 0 | 53.7 | 0 |

| no special twin environment | 3 | 19 | 0 | 21.8 | 0 | 38.9 | 0 |

| no cultural transmission | 4 | 5.1 | 0.27 | 0.8 | 0.94 | 2.6 | 0.62 |

| no additive genetic effects | 3 | 6.2 | 0.1 | 1.8 | 0.61 | 7.5 | 0.06 |

| no dominance effects | 3 | 0.2 | 0.98 | 2.4 | 0.5 | 1.9 | 0.6 |

| no shared environment (cult tr + np env) | 10 | 69.8 | 0 | 63.5 | 0 | 126.3 | 0 |

| no genetic effects | 6 | 85.6 | 0 | 82.5 | 0 | 165.7 | 0 |

| no familial resemblance | 16 | 1654.9 | 0 | 1599.7 | 0 | 3240.8 | 0 |

| ET without dominance and male-specific genetic factors (rg correlation) | |||||||

| no assortment | 1 | 247.6 | 0 | 257.3 | 0 | 504.1 | 0 |

| no non-parental shared environment | 3 | 25.3 | 0 | 28.6 | 0 | 52.7 | 0 |

| no special twin environment | 3 | 19.4 | 0 | 23.4 | 0 | 40.8 | 0 |

| no cultural transmission | 4 | 13 | 0.011 | 6 | 0.2 | 14.1 | 0.01 |

| no shared environment (cult tr + np env) | 10 | 183 | 0 | 206.9 | 0 | 380.9 | 0 |

| no additive genetic effects | 3 | 85.4 | 0 | 80.2 | 0 | 163.8 | 0 |

| no familial resemblance | 14 | 1654.7 | 0 | 1597.3 | 0 | 3238.9 | 0 |

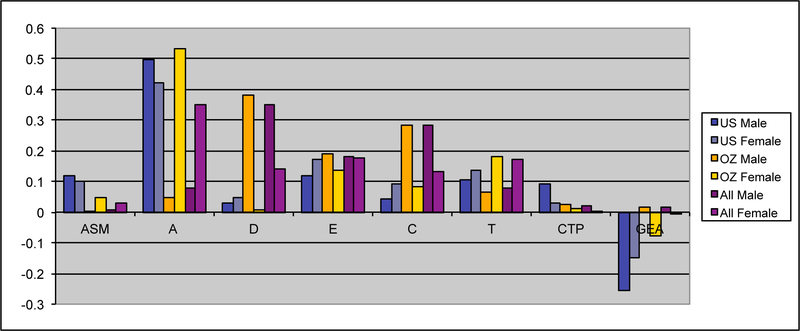

Maximum likelihood estimates of the genetic and environmental parameters under the ET model and the derived proportions of variance for the genetic and environmental effects on smoking initiation from the analysis of individual observations of both samples combined are shown in Table 4. Additive genetic effects accounted for 53% of the variance in smoking in males and 55% in females. These proportions included the effects due to assortative mating (about 10%), consistent with the highly significant spousal correlation r=.40. The contribution of genetic dominance was negligible. The shared environmental effects on smoking arose from non-parental sources, special twin environment and cultural transmission. In males, these sources explained 17, 9 and 6% of the variance, respectively. The corresponding proportions for females were 11, 15 and 4%. Genotype-environment covariance was estimated to be negative for males and females, which would result in negative contribution of this source of variance, if included in the calculation of variance components. Individual specific environmental factors made up the remainder of the variance (15% in males and females). The correlations between the non-parental and twin shared environments in males and females were estimated at .20 and .74 respectively, suggesting that partly different shared environmental factors account for similarity in smoking initiation in males and females. This is not surprising, since the opposite-sex twin and sibling correlations are considerably lower than their respective same-sex correlations. Given the large number of estimated parameters and the ordinal data input, estimating confidence intervals in OpenMx using the method of Neale and Miller (1997) would require an impractical amount of computer time. Therefore, we opted to fit a range of submodels which allows us to test the significance of individual parameters or a group of parameters simultaneously (see Table 3 above).

Table 4:

Parameter estimates and variance components from the ET model for smoking initiation

| Full ET | No dominance | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Variance | Parameter | Variance | |||||||

| Estimates | Components | Estimates | Components | |||||||

| male | female | mf | male | female | male | female | mf | male | female | |

| Assortative mating | 0.40 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.40 | 0.10 | 0.10 | ||||

| Common additive genetic | 0.26 | 0.73 | 0.06 | 0.50 | 0.73 | 0.74 | 0.43 | 0.45 | ||

| Male-specific genetic | 0.69 | 0.47 | . | - | - | |||||

| Dominance | 0.15 | −0.12 | 1 | 0.02 | 0.01 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Unique environment | 0.45 | 0.44 | 0.17 | 0.17 | 0.51 | 0.48 | 0.15 | 0.15 | ||

| Shared environment | 0.43 | 0.33 | 1 | 0.17 | 0.10 | 0.47 | 0.37 | 0.20 | 0.18 | 0.11 |

| Twin environment | 0.28 | 0.41 | 0.99 | 0.07 | 0.16 | 0.33 | 0.42 | 0.74 | 0.09 | 0.15 |

| Cultural transmission father | −0.18 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 | −0.13 | −0.32 | 0.06 | 0.04 | ||

| Cultural transmission mother | −0.18 | −0.24 | −0.48 | −0.23 | ||||||

| GE covariance | −0.14 | −0.10 | −0.32 | −0.29 | ||||||

| GE covariance male-specific | −0.10 | −0.04 | - | - | ||||||

mf: male-female; genotype-environment correlation a: between common additive genetic factors and environment; genotype-environment correlation b: between male-specific genetic factors and environment

Discussion

To our knowledge, the combined US and Australian (OZ) samples comprising 50,318 adult individuals from 88 distinct biological and social relationships constitute the largest and most informative study of the inheritance of smoking initiation to date. Our results add considerable weight to previous findings that genetic factors contribute significantly to family resemblance in smoking initiation. The overall contribution of genetic factors to individual differences was similar for females and males (broad heritability 55%), consistent with previous large twin and family studies (Madden et al. 2004). However, in contrast with these previous studies we have explicitly modeled the effects of assortative mating and environmental transmission, as both the design and the power allow us to detect more complex patterns of causation, if they exist (Eaves et al., 1977; Martin et al., 1978; Heath and Eaves, 1985; Heath et al., 1985; Fulker 1988, Eaves et al., 1989). As such, the analyses of the Australian sample constitutes a replication of the results of the US sample alone (Maes et al. 2006), which was formally tested by analyzing both samples simultaneously and testing the equality of the familial parameters. Most remarkably, the estimates of the 88 unique correlations in the OZ sample were very close to those in the US sample, and consequently the estimates of the genetic and environmental parameters were extremely close.

Results for the extended twin kinship analyses demonstrated not only that genetic factors play a significant role in the liability to smoking initiation, they also confirmed the role of assortative mating, shared sibling environment, twin environment (which could mask gene × age interaction), cultural transmission and resulting genotype-environment covariance on individual differences in smoking initiation. The overall heritability in the combined data was estimated to be 55% in males and females. Note that this estimate of heritability is lower than in Maes et al. (2006), as it is calculated here as the proportion of variance, not including the (negative) genotype-environment (GE) covariance, such that all the variance components except for GE covariance add up to one. This provides a better comparison with other twin studies which cannot distinguish GE covariance. The combined US-OZ heritability estimate was very close to the unweighted mean (56% for males, 50% for females) calculated from published reports on adult Scandinavian, Australian and US samples (Prescott et al. 2005). Note that the US samples are mostly overlapping with the Virginia 30,000. The estimates of the specific environmental variance, including measurement error, were consistent across the current analyses (15%) and published reports (18%).

If substantial assortment exists for the phenotype of interest, the estimates of the genetic and environmental parameters from twin studies will be biased if assortment is not taken into account. The spousal correlation was estimated at .38 in the US sample and .42 in the OZ sample, both of which are in line with published spousal correlations for smoking initiation which range mostly from .18 to .43 based on US, Swedish, Dutch and Finnish samples (Price and Vandenberg 1980; Boomsma et al. 1994; Kaprio et al. 1995). Thus, results from the OZ sample confirmed that about 10% of the total variance in smoking initiation was due to the genetic consequences of assortative mating.

Twin studies have consistently reported significant contributions of the shared environment to the liability to smoking initiation, the unweighted mean from published reports of adult samples being 24–28%. The US and OZ samples both suggested that 30–35% of the variance can be accounted for by the combined effects of all sources of shared environment (sibling, twin & cultural transmission), which is not far from previous estimates. The advantage of the extended kinship design is that it allows us to distinguish between the environmental effects shared with co-twins, siblings, and peers versus those shared with their parents. The results from the analysis of the OZ data confirmed significant contributions of non-parental shared environment (factors shared with siblings, and possibly additional factors shared with co-twins) and of cultural transmission observed in the US sample, with similar proportions of variance accounted for by each source. The additional similarity in twins could be due to lingering effects of the intrauterine environment or greater socialization with people of similar age. In both samples, the shared environmental variance component was greater in males, and the special twin environmental component slightly greater in females. Furthermore, it appeared that the shared environmental factors were different in males and females in both samples, indicated by the significantly lower opposite sex versus same sex correlations. This observation is in line with previously reported correlations between the shared environmental factors of males and females (rc) less than one for smoking initiation (Boomsma et al. 1994; Heath et al. 1993). However, it is also consistent with different sets of genes expressed in males and females, supported by the significant estimate of the male-specific genetic effects.

The finding of borderline significant contributions of parental shared environmental factors (or cultural transmission) was replicated in the OZ data, and they accounted for a similarly small proportion of the total variance (around 5%) as in the US data. Furthermore, the paths from parents to children’s environment were also estimated to be negative, suggesting that parents have inhibiting or promoting effects on their children’s smoking initiation. These results are consistent with the only other available twin-parent data which also showed negative, but non-significant cultural transmission (Boomsma et al. 1994). In fact, these results are also consistent with the vast epidemiological literature on parental smoking as a risk factor for adolescent smoking (Li et al. 2002; Peterson et al 2005; Shakib et al. 2003; Vitaro et al. 2004) and parental non-smoking or smoking cessation as a protective factor (Andersen 2004, Bricker 2005, den Exter Blokland et al. 2004), derived from the moderate phenotypic correlations between parents and children/adolescents. Based on the heritability estimates from twin studies, parent-offspring correlations would be expected to be larger than they are. A possible explanation is that the environmental transmission is negative while the genetic transmission is positive. Thus the availability of a genetically informative design, with different types of relative is more informative than a nuclear family design which does not allow for the separation of the genetic effects of parents on their children from the environmental influences. Furthermore, the marginal significance of cultural transmission compared to the non-parental shared environmental sources of variance corresponds to the finding that adolescent smoking is more strongly associated with friends’ and siblings’ smoking than parents’ smoking (de Vries et al. 2003; Rose et al. 2003; Simons-Morton et al. 2004, Vink et al. (2003a, Vink et al. 2003b). Thus it appears that the environmental impact on smoking initiation is age dependent such that the influence of the parents on their offspring smoking initiation is limited and that the observed parent-child association is primarily accounted for by shared genes.

Other possible genetic explanations for the lower than expected parent-offspring than sibling correlations are genetic dominance or gene × age interaction. Unlike the classical twin study, the extended twin kinship design allows us to disentangle the combined effects of additive genetic, dominance and shared environmental factors. The results from fitting the full model showed no evidence for dominance. In effect, the dominance variance was estimated very close to zero in both samples. The alternative explanation of gene × age interaction implies that the genetic variance changes as a function of age and/or that different genes account for variability at different ages (Eaves et al. 1978), sometimes called reduced genetic transmission. Although the study was cross-sectional, we previously examined the change in genetic variance with age in two ways in the Virginia sample and concluded that the impact of age on the genetic architecture of smoking initiation is limited (Maes et al. 2006). Madden et al. (2004) also reported no change in additive genetic variance across three age groups between age 18 and 46, as well as three countries (Australia, Sweden & Finland), in women and in men. The issue of gene × age interaction could be further explored by moderating the correlation between relatives of different ages by their age difference (Verhulst et al. 2014).

On the other hand, age significantly influenced the prevalence of smoking initiation in males in the US sample, but the effect was not significant for females or for either sex in the OZ sample. Given the estimates of genetic and environmental parameters would be slightly biased if ignored, age regression on the prevalence was modeled. However, cohort and age effects may be confounded. Although prevalence of tobacco use has decreased in both males and females since the data were collected, the estimates of the contribution of genetic and environmental factors are consistent with estimates from more recently collected samples. Given the prevalence of smoking decreased more rapidly with age in the cohorts captured in the Virginia 30,000 and the Australian 25,000 sample than data collected since then, results are expected to be influenced only to a limited extent.

In summary, the data on a wide range of biological and social relationships from two large samples on different continents confirmed that genetic factors accounted for the majority of individual differences in liability to smoking initiation, with a small proportion resulting from the consequences of assortative mating. Shared environmental factors do played a significant role, but were primarily due to within-generational influences, e.g. siblings and co-twins. The association between smoking initiation in parents and their children could be most likely accounted for by their genetic relatedness with limited negative environmental influence. It is important to note that the estimates obtained here were not just based on twin data, but on a wide range of relatives with different degrees of genetic similarity and shared environments. Furthermore, our estimates were obtained from taking the effects of sex, assortment, genotype × environment covariance and age regression of the prevalence into account.

Limitations

Given the complexity of the model and the large number of estimated parameters, caution is needed in the interpretation of the results. Even with two large samples, information may be limited to estimate some parameters, especially those that are highly correlated or only identified by one or a few relationships. Second, the sample was entirely Caucasian, and we do not know whether the pattern of results holds for other ethnic groups. Third, the sample of twins and relatives is a volunteer sample, thus the possibility of response bias exists. Response bias is principally a concern if missingness is related to the response variable (Little and Rubin, 1987) and with relatives we are in the fortunate situation that we have information about non-responding relatives through the relatives who did respond (Neale and Eaves, 1993). The fortunate consequence of maximum likelihood estimation with single relatives jointly with complete pairs is to correct the bias in mean and variance of the former towards their true population values (Little and Rubin, 1987; Muthén et al., 1987).

Figure IIIa:

Maximum likelihood estimates of parameters for the full extended family resemblance model for smoking behavior in the VA30,000 and OZ25k

Figure IIIb:

Maximum likelihood estimates of parameters for the extended family resemblance model for smoking initiation in the VA30,000 and OZ25k, not estimating dominance variance

Acknowledgments

This research has been supported by grants AG04954, GM30250, GM32732, AA06781, AA07728, AA07535 and MH40828 from NIH, grant 941177 and 971232 from the NH&MRC, a gift from R.J.R. Nabisco and grants from the JM Templeton Foundation. The authors would also like to thank the twins and their families on both continents for their participation in this project. The first author is supported by grants HL60688, MH45268, DA016977, MH068521, DA018673, DA025109 and the Virginia Tobacco Youth Project.

References

- Andersen MR, Leroux BG, Bricker JB, Rajan KB, and Peterson AV Jr. (2004). Antismoking parenting practices are associated with reduced rates of adolescent smoking. Arch. Pediat. Adol. Med 158:348–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boker S, Neale MC, Maes HH, Wilde M, Spiegel M, Brick T, Spies J, Estabrook R, Kenny S, Bates T, Mehta P, Fox J (2010). OpenMx: An Open Source Extended Structural Equation Modeling Framework. Psychometrika 76(2):306–317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boomsma DI, Koopmans JR, Van Doornen LJ & Orlebeke JF (1994). Genetic and social influences of starting to smoke: a study of Dutch adolescent twins and their parents. Addiction 89:219–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bricker JB, Rajan KB, Andersen MR, and Peterson AV Jr (2005). Does parental smoking cessation encourage their young adult children to quit smoking? A prospective study. Addiction 100:379–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US); National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (US); Office on Smoking and Health (US). How Tobacco Smoke Causes Disease: The Biology and Behavioral Basis for Smoking-Attributable Disease: A Report of the Surgeon General Atlanta (GA: ): Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US); 2010. 6, Cardiovascular Diseases; Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK53012/, accessed April 2018 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- den Exter Blokland EA, Engels RC, Hale WW 3rd, Meeus W, and Willemsen MC (2004). Lifetime parental smoking history and cessation and early adolescent smoking behavior. Prev. Med 38:359–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Vries H, Engels R, Kremers S, Wetzels J, and Mudde A (2003). Parents’ and friends’ smoking status as predictors of smoking onset: findings from six European countries. Health Educ. Res 18:627–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaves LJ, Last K, Martin NG, Jinks JL (1977). A progressive approach to non-additivity and genotype-environmental covariance in the analysis of human differences. Br. J. Math. Stat. Psychol 30:1–42. [Google Scholar]

- Eaves LJ, Last KA, Young PA, and Martin NG (1978). Model-fitting approaches to the analysis of human behaviour.” Heredity (Edinb) 41: 249–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaves LJ, and Eysenck HJ (1980). The Causes and Effects of Smoking London: Maurice Temple Smith, Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Eaves LJ, Eysenck HJ, and Martin NG (1989). Genes, Culture and Personality: An empirical approach London: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Eaves LJ, Heath AC, Martin NG, Neale MC, Meyer JM, Silberg JL, Corey LA, Truett K, and Walters E (1999). Comparing the biological and cultural inheritance of stature and conservatism in the kinships of monozygotic and dizygotic twins. In: Cloninger CR (Ed) Proceedings of 1994 APPA Conference p. 269–308. [Google Scholar]

- Fulker DW (1988). Genetic and cultural transmission in human behavior. In: Weir SB, Eisen EJ, Goodman MM, Namkoong G (Eds) Proceedings of the Second International Conference on Quantitative Genetics p. 318–340. [Google Scholar]

- Jardine R, Martin NG, and Henderson AS (1984). Genetic covariation between neuroticism and the symptoms of anxiety and depression. Genet Epidemiol 1: 89–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heath AC, and Eaves LJ (1985). Resolving the effects of phenotype and social background on mate selection. Behav. Genet 15:15–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heath AC, Kendler KS, Eaves LJ, and Markell D (1985). The resolution of cultural and biological inheritance: informativeness of different relationships. Behav Genet 15: 439–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heath AC, Cates R, Martin NG, Meyer J, Hewitt JK, Neale MC, and Eaves LJ (1993). Genetic contribution to risk of smoking initiation: comparisons across birth cohorts and across cultures. J. Subst. Abuse 5:221–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heath AC, Madden PA, and Martin NG (1998). Statistical methods in genetic research on smoking. Stat. Methods Med. Res 7:165–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaprio J, Boomsma DI, Heikkilä K, Koskenvuo M, Romanov K, Rose RJ, Viken RJ, Winter T (1995). Genetic variation in behavioral risk factors for atherosclerosis: twin-family study of smoking and cynical hostility. In: Woodford FP, Davignon J, Sniderman A (Eds) Artherosclerosis X p. 634–637. [Google Scholar]

- Kaprio J (2009). Genetic Epidemiology of Smoking Behavior and Nicotine Dependence. Journal of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease 6:304–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Karkowski LM, and Pedersen NC (2000). Tobacco consumption in Swedish twins reared-apart and reared-together. Arch. Gen. Psychiat 57:886–892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lake RIE, Eaves LJ, Maes HHM, Heath AC, Martin NG (2000). Further evidence against the environmental transmission of individual differences in Neuroticism from a collaborative study of 45,850 twins and relatives on two continents. Behav Genet 30:223–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C, Pentz MA, and Chou CP (2002). Parental substance use as a modifier of adolescent substance use risk. Addiction 97:1537–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li MD (2003). The genetics of smoking related behavior: a brief review. Am. J. Med. Sci 326:168–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little RJA, and Rubin DB (1987). Statistical analysis with missing data New York: John Wiley & Sons, xiv + 278 pp. [Google Scholar]

- Madden PA, Pedersen NL, Kaprio J, Koskenvuo MJ, and Martin NG (2004). The epidemiology and genetics of smoking initiation and persistence: cross-cultural comparisons of twin study results. Twin Res 7:82–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin NG, Eaves LJ, Kearsey MJ, and Davies P (1978). The power of the classical twin study. Heredity (Edinb) 40: 97–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maes HH, Neale MC, Martin NG, Heath AC, and Eaves LJ. (1999). Religious attendance and frequency of alcohol use: same genes or same environments: a bivariate extended twin kinship model. Twin Res 2:169–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maes HH, Neale MC, Kendler KS, Martin NG, Heath AC, Eaves LJ (2006). Genetic and cultural transmission of smoking initiation. An extended twin kinship model. Behav Genet 36:795–808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maes HH, Neale MC (2009). Genetic modeling of tobacco use behavior and trajectories. In: Swan GE, Baker TB, Chassin L, et al. , eds. NCI Tobacco Control Monograph Series 20: Phenotypes and Endophenotypes: Foundations for Genetic Studies of Nicotine Use and Dependence: US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health [Google Scholar]

- Muthén B, Kaplan D, and Hollis M (1987). On structural equation modeling with data that are not missing completely at random. Psychometrika 52: 431–462. [Google Scholar]

- Neale MC, and Eaves LJ (1993). Estimating and controlling for the effects of volunteer bias with pairs of relatives. Behav Genet 23: 271–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neale MC, Boker SM, Xie G, and Maes HH (2006). Mx: Statistical Modeling Department of Psychiatry, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond Virginia: 7th Edition. [Google Scholar]

- Neale MC, and Cardon LR (1992). Methodology for genetic studies of twins and families Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dortrecht. [Google Scholar]

- Neale MC, Hunter MD, Pritikin JN, Zahery M, Brick TR, Kirkpatrick RM, Estabrook R, Bates TC, Maes HH, Boker SM (2017). OpenMx 2.0: Extended Structural Equation and Statistical Modeling. Psychometrika 81(2):535–549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neale MC, and Miller MB (1997). The use of likelihood-based confidence intervals in genetic models. Behav. Genet 27:113–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ooki S, Yamada K, Asaka A, and Hayakawa K (1990). Zygosity diagnosis of twins by questionnaire. Acta Genet. Med. Gemel. (Roma) 39:109–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson AV Jr, Leroux BG, Bricker J, Kealey KA, Marek PM, Sarason IG, and Andersen MR (2005). Nine-year prediction of adolescent smoking by number of smoking parents. Addict. Behav [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prescott CA, Maes HH, and Kendler KS (2005). Genetics of Substance Use Disorders, in Psychiatric Genetics (Review of Psychiatry Vol 24), Kendler KS, and Eaves LJ (Eds). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Price RA, and Vandenberg SG (1980). Spouse similarity in American and Swedish couples. Behav. Genet 10:59–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose RJ, Viken RJ, Dick DM, Bates JE, Pulkkinen L, and Kaprio J (2003). It does take a village: Nonfamilial environments and children’s behavior. Psychol. Sci 14:273–277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scollo MM and Winstanley MH. Tobacco in Australia: Facts and issues Melbourne: Cancer Council Victoria; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Shakib S, Mouttapa M, Johnson CA, Ritt-Olson A, Trinidad DR, Gallaher PE, and Unger JB (2003). Ethnic variation in parenting characteristics and adolescent smoking. J. Adol. Health 33:88–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons-Morton B, Chen R, Abroms L, and Haynie DL (2004). Latent Growth Curve Analyses of Peer and Parent Influences on Smoking Progression Among Early Adolescents. Health Psychol 23:612–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan PF, and Kendler KS (1997). The genetic epidemiology of smoking. Nicotine Tob. Res 1:S51–S57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truett KR, Eaves LJ, Walters EE, Heath AC, Hewitt JK, Meyer JM, Silberg J, Neale MC, Martin NG, and Kendler KS (1994). A model system for analysis of family resemblance in extended kinships of twins. Behav. Genet 24:35–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhulst B, Eaves LJ, Neale MC (2014). Moderating the covariance between family member’s substance use behavior. Behav. Genet 44:337–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vink JM, Willemsen G, and Boomsma DI (2003). The association of current smoking behavior with the smoking behavior of parents, siblings, friends and spouses. Addiction 98:923–931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vink JM, Willemsen G, Engels RC, and Boomsma DI (2003). Smoking status of parents, siblings and friends: predictors of regular smoking? Findings from a longitudinal twin-family study. Twin Res 6:209–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitaro F, Wannera B, Brendgena M, Gosselinb C, and Gendreaua PL (2004). Differential contribution of parents and friends to smoking trajectories during adolescence. Addict. Behav 29:831–835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization, http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs339/en/, accessed April 2018. [DOI] [PubMed]