Abstract

The ability to alter gene expression directly in T lymphocytes has provided a powerful tool for understanding T cell biology, signaling and function. Manipulation of T cell clones and primary T cells has been accomplished primarily through overexpression or gene-silencing studies using cDNAs or shRNAs, respectively, which are often delivered by retroviral or lentiviral transduction or direct transfection methods. The recent development of CRISPR/Cas9-based mutagenesis has revolutionized genomic editing, allowing unprecedented genetic manipulation on many cell types with greater precision and ease. In this chapter, we outline a protocol for CRISPR/Cas9-mediated mutagenesis in primary T lymphocytes from Cas9 transgenic mice using retroviral delivery of guide RNAs.

Keywords: CRISPR, Cas9, murine T cells, gene knockout, retroviral vector

INTRODUCTION

The CRISPR (clustered regularly interspersed short palindromic repeats) Cas (CRISPR associated) system is a genome-editing mechanism that was first discovered in bacteria and archaea as an RNA-mediated adaptive immune defense mechanism against viruses and plasmids (Horvath & Barrangou, 2010). The development of CRISPR into a powerful genome engineering tool was made possible by the discovery that the minimum system components are a Cas9 nuclease, a CRISPR RNA (crRNA, that targets complementary DNA), and an invariant scaffold trans-activating crRNA (tracrRNA). The crRNA and tracrRNA can be artificially linked into a single guide RNA (sgRNA), thereby reducing the number of components that must be introduced into the target cell to two (Cong et al., 2013; Jinek et al., 2013; Mali, Yang, et al., 2013; T. Wang, Wei, Sabatini, & Lander, 2014).

The majority of studies have focused on the Streptococcus pyogenes CRISPR (spCas9) system, in which the Cas9 endonuclease uses a 17–20 nucleotide guide RNA to find the corresponding genomic DNA sequence upstream of a protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) sequence, NGG. It then makes a blunt double-strand break in the genomic DNA 3 base pairs upstream of the PAM, i.e. between the 17th and 18th nucleotides of the 20 nucleotide guide sequence. In mammalian cells, the double-strand breaks caused by Cas9 are repaired via the error-prone mechanisms of non-homologous end joining (NHEJ), which generates both insertion and deletion mutations that can interrupt coding sequences of genes, as well as non-coding and regulatory regions of the genome. Genetically engineered transgenic spCas9-expressing mice (Chu, Weber, et al., 2016; Platt et al., 2014) can provide primary cells that already express the nuclease, and therefore require only the introduction of the sgRNA. This last approach is the protocol we will describe in this unit. Alternative techniques, including the use of a short homologous sequence to guide homology-directed repair (HDR) and new base-editing technologies, allow specific tailored modifications to the genome, but will not be the subject of this protocol (see discussion below).

Primary mouse T cells provide an excellent experimental system to dissect T cell signaling and function, both in reductionist in vitro systems, and within the physiological in vivo context after the genetically manipulated T cells are transferred back into animal models. Mouse T cells are very amenable to genetic manipulation, including gene overexpression and gene knockdown by shRNA. However, in contrast to shRNA, CRISPR is capable of complete expression knockout, and for proteins with residual activity at low levels of expression, complete knockout may be required to observe a phenotype. While CRISPR off-targeting remains a concern and an active area of research, studies directly comparing CRISPR and shRNA knockdown of genes suggest that the efficacy and specificity of CRISPR is higher than that of shRNA (Koike-Yusa, Li, Tan, Velasco-Herrera, & Yusa, 2014; Shalem, Sanjana, & Zhang, 2015). Thus, although shRNA is still a very useful tool, particularly when reduction in gene-expression may be desired (versus complete knockout), CRISPR-mediated mutagenesis is now recognized as a powerful tool for evaluating gene function.

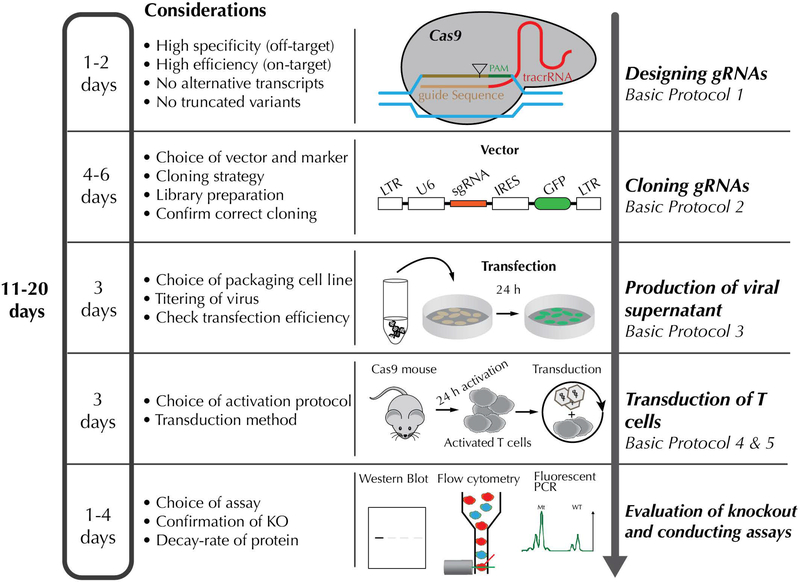

This unit describes protocols to knockout genes in primary transgenic Cas9-expressing murine T cells, using retroviral transduction of a guide RNA (gRNA) construct. We first describe the selection of guide sequences with predicted high activity and low off-targeting (Basic Protocol 1), then subcloning of these sequences into a retroviral vector (Basic Protocol 2), transfection of these constructs into 293T cells to produce high-titer retroviral stocks (Basic Protocol 3), activation of primary murine T cells (Basic Protocol 4, and Alternate Protocol 1), and transduction of the T cells with retrovirus for downstream assays and characterization (Basic Protocol 5) (Fig 1). While this approach has high transduction (70–90%) and mutagenesis efficiencies (70–98% of transduced cells), it requires activation of the T cells, which may be avoided by transducing naïve T cells with lentivirus. Transient introduction of CRISPR components can also be achieved by electroporation of ribonucleoproteins (RNP) consisting of Cas9 protein complexed with in vitro transcribed sgRNA (Schumann et al., 2015; Seki & Rutz, 2018). Our approach takes advantage of transgenic Cas9 expression in the T cells, but we have also mutagenized wild-type T cells with an “all-in-one” Cas9-sgRNA retroviral vector, albeit achieving a lower efficiency of transduction (30–60%) and mutagenesis (15–50% of transduced cells). This is likely due to the large size of the Cas9 nuclease, and the size limit of sequences that can be efficiently packaged into retroviruses. However, all-in-one constructs including lentiviral vectors (which have a larger packaging limit) or RNP approaches, are useful for manipulation of T cells lacking Cas9, including primary human T cells.

Figure 1. Experimental timeline.

Note: All experiments were performed in accordance with the guidelines of the NHGRI Animal Care and Use Committee at the National Institutes of Health under protocol number NHGRI G98–3. Mice were maintained under specific pathogen-free (SPF) conditions.

STRATEGIC PLANNING

A key part of experimental design is when and how targeted cells will be assayed. Our kinetics studies for several model proteins show complete loss 4 days after T cell activation, but this will depend on the half-life of targeted proteins. We therefore typically use cells for downstream assays 5–7 days post-activation. If cells are used at earlier timepoints, protein loss may not be maximal. This workflow also may preclude the analysis of early events in naïve T cell signaling and activation, which would require either lentiviral transduction of naïve T cells, or prolonged culture of the T cells according to our protocol to reach a state of quiescence, followed by restimulation.

Depending on the number of T cells needed for downstream assays, the protocol can be scaled according to tissue culture well area, e.g. the following protocol is for 1 × 106 CD4 T cells in 24-well plates, but reagent volumes and well size can be increased for greater numbers of cells. See Tables 1 and 2 for details.

Table 1.

Reagent amounts and cell numbers for transfection in various sized plate formats.

| Wells | 6w | 12w | 24w | 48w | 96w |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surface area, cm2 | 9.5 | 3.8 | 1.9 | 0.95 | 0.32 |

| #293T | 800K | 350K | 175K | 80K | 25K |

| % confluency | 60–80% | 60–80% | 60–80% | 60–80% | 60–80% |

| EMEM, μl | 2.5 ml | 1.2 ml | 600 μl | 300 μl | 100 μl |

| OPTIMEM, μl | 300 | 120 | 60 | 30 | 10 |

| Plasmid, μg | 2 | 0.8 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.07 |

| pCL-Eco, μg | 1 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.035 |

| Mirus, μL | 9 | 3.6 | 1.8 | 0.9 | 0.3 |

Table 2.

Appropriate T cell numbers for different well sizes.

| Wells | 6w | 12w | 24w | 48w | 96w |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surface area, cm2 | 9.5 | 3.8 | 1.9 | 0.95 | 0.32 |

| #T cells, 106 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.1 |

BASIC PROTOCOL 1

SELECTION OF GUIDE RNA SEQUENCES

For efficient CRISPR/Cas9-mediated mutagenesis resulting in knockout of the targeted protein, it is necessary to design gRNAs that efficiently and specifically mutate the target gene of interest. Design criteria for selecting gRNAs have been described in depth on several occasions before (Doench et al., 2016, 2014; Hsu et al., 2013), and several tools are available online to assist with the design (see Internet Resources section). For more information, see Critical Parameters.

Below is a suggested workflow for designing gRNAs using the Benchling software, however other softwares such as Deskgen, Synthego, and MIT CRISPR Design can be used just as well, and it can be useful to double-check that the same gRNAs are recommended with different tools. Different tools can incorporate different algorithms for gRNA off- and on-target prediction, and the scoring cut-off should take that into consideration.

To begin, we suggest choosing 3–4 gRNAs per target gene, as well as 2 gRNAs against an easily assayable gene such as CD4, CD8, LFA1, or Thy1. The latter will help to establish optimal T cell activation, transduction, culture, and mutagenesis assay conditions before investigating knockout of genes of unknown function. We provide a validated sequence for Thy1.2 below.

Designing gRNAs with Benchling

On your Benchling homepage click “Create” (+ symbol) → “CRISPR” → “CRISPR Guides”

-

Search for your target gene of interest

It can be useful to find the ENSEMBL Gene ID to avoid confusion in gene names.

Choose your genome of interest, and make sure that Benchling located the correct gene.

Press “Next”.

-

For Gene disruption with conventional WT Cas9 choose “Single guide”, your desired gRNA length (in most cases 20 bp), and the PAM sequence required for your Cas9 variant. Click “Finish”.

When using spCas9, the optimal gRNA length is 20 bp, and the PAM sequence required is NGG. The PAM sequence will NOT be part of your guide RNA. If you want to further specify the gRNA design parameters, press “Advanced Settings”, this allows for restricting gRNAs presented to gRNAs above a specific on-target or off-target threshold.

Mark the first exon of interest (either in the “Sequence Map” or the “Linear Map”), and under the fan “Design CRISPR”, press “Create” (+ symbol).

In many cases, the Benchling software will not automatically select a “Genome Region”. If it states “No region set” under the “Genome Region”, click “No region set” and then click “Find Genomic Matches”. Choose the target genome region for your gene.

-

Repeat step 6–7 for all target exons of interest.

Preferably target exons that are in the first 2/3 of the gene. This will decrease the risk of creating functional truncated variants of the protein. It is also advisable to target regions downstream of alternative start codons.

-

Arrange suggested gRNAs based on “On-target scores”, and pick 3–5 gRNAs with high “On-target scores” (>50–60) and high “Off-target scores” (>60).

It is recommended to design the 3–5 gRNAs targeting different exons of the gene of interest to ensure that different splice variants are disrupted. Further, make sure that the gRNA does not contain any restriction enzyme sites used in the cloning procedure.

For Thy1.2, we use the guide sequence CGTGTGCTCGGGTATCCCAA, which has an on-target score of 84.6 and an off-target score of 93.5. See Fig 2 for an example of experimental data generated using this guide sequence.

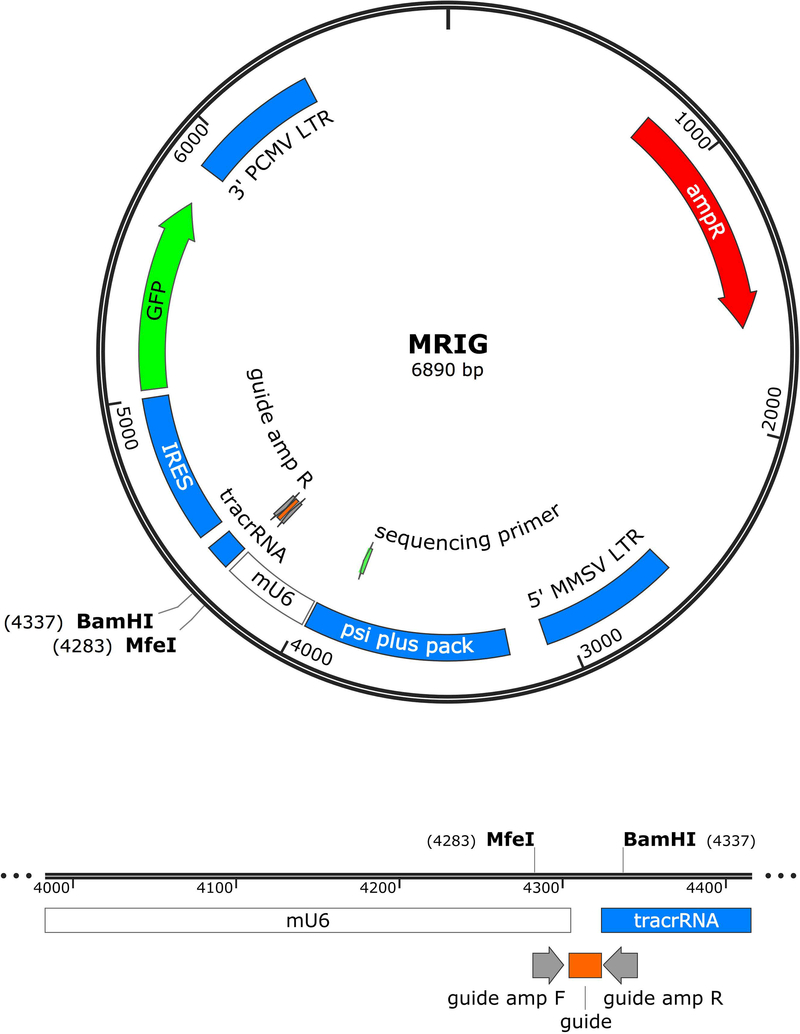

Figure 2. Map of retroviral vector for sgRNA expression.

BASIC PROTOCOL 2

SUBCLONE GUIDE RNA CONSTRUCT

In this protocol, the gRNA sequence chosen in Basic Protocol 1 is subcloned into a retroviral vector. We use a custom retroviral vector based on pQCIG2 (Malina et al., 2014), which contains the U6 promoter to drive the expression of the sgRNA (guide RNA and the invariant tracrRNA). In its original state, the vector was in a self-inactivating backbone and led to low transduction efficiencies in murine T cells (<2% GFP+). We moved the U6-sgRNA construct into MIGR1 (Addgene #27490), a non-inactivating viral backbone, to improve transduction efficiency. The final vector contains the U6 promoter to drive the transcription of the sgRNA, followed by an IRES and GFP reporter (Figure 2). For a discussion of other vectors see Critical Parameters.

The gRNA sequences (for the vector we use) are ordered as part of a single strand DNA oligo, containing the gRNA sequence in the middle, flanked on the 5’ end by part of the U6 promoter sequence, and on the 3’ end by part of the tracrRNA sequence. The oligo is then PCR amplified with a forward primer that contains the 3’ end sequence of the U6 promoter, and a reverse primer that contains the 5’ beginning sequence of the tracrRNA. The retroviral vector and the gRNA PCR product are digested with restriction enzymes, purified, ligated, and transformed into chemically competent bacteria. Clones are selected for plasmid preparation and Sanger sequencing to confirm correct insertion of the gRNA sequence.

The cloning protocol is also adaptable for pooled oligo libraries, by PCR amplification of an oligo pool using extended primers (with homology to the U6 and tracrRNA regions), followed by Gibson assembly and transformation into electrocompetent cells (Shalem et al., 2014)(Huang et al, in preparation).

Materials

Phusion polymerase (New England Biolabs, Cat# M0530) or other high-fidelity DNA polymerase

dNTP mix

Nuclease-free water

BamHI-HF (New England Biolabs, Cat# R3136)

MfeI-HF (New England Biolabs, Cat# R3589)

T4 DNA ligase (Thermo Fisher, Cat# 15224017)

QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen, Cat# 28104) or other column-based DNA purification kit

QIAquick Gel extraction kit (Qiagen, Cat# 28704) or other column-based DNA purification kit

Qiaprep Spin Miniprep kit (Qiagen, Cat# 27104) or other column-based plasmid purification kit

Competent cells such as HB101 (Zymo, Cat# T3011) or other low-recombination strain

SOC medium

Luria broth medium

Ampicillin (or appropriate antibiotic)

Thermocycler

Gel electrophoresis equipment and voltage source

Nanodrop or other spectrophotometer

Order DNA oligomer containing the gRNA sequence as follows.

5’-GGAGAAAAGCCTTGTTTG – 20 bp gRNA – GTTTTAGAGCTAGGATCCTAGC-3’

The 5’ sequence is part of the U6 promoter. The 3’ sequence is part of the tracrRNA.

Do not include the PAM as part of the gRNA sequence.

-

2.

PCR amplify DNA oligo using the amplification primers as follows.

Forward: GTATCGCAATTGGAGAAAAGCCTTG

Reverse: GTATCGGCTAGGATCCTAGCTCTAAAA

| Phusion HF buffer, 5× | 5 μl |

| dNTPs, 10 mM | 0.5 μl |

| Oligo, 1 μM | 2.5 μl |

| Forward primer, 10 μM | 1.25 μl |

| Reverse primer, 10 μM | 1.25 μl |

| Phusion, 2 U/μl | 0.25 μl |

| Nuclease-free water | to 25 μl |

| Total | 25 μl |

-

3.

Purify the amplified oligo using a PCR purification kit, according to manufacturer’s instructions, eluting in 30 μl of nuclease-free water.

-

4.

Set up the restriction digest reaction of the PCR amplified oligo as follows.

| Amplified gRNA | 25 μl of elution from previous step |

| CutSmart 10X restriction buffer | 3 μl |

| BamHI-HF 1 | μl |

| MfeI-HF 1 | μl |

| Total | 30 μl |

The CutSmart buffer is included with NEB restriction enzymes.

-

5.

Simultaneously set up the restriction digest reaction of the retroviral vector as follows.

| Vector | 2 μg |

| CutSmart buffer | 3 μl |

| BamHI-HF | 1 μl |

| MfeI-HF | 1 μl |

| Nuclease-free water | to 30 μl |

| Total | 30 μl |

-

6.

Digest both reactions for 2 h at 37 °C.

-

7.

Run the vector digest reaction on a 0.7% agarose gel.

-

8.

Cut the digested linear vector band and purify the DNA using the gel extraction kit according to manufacturer’s instructions. Elute in 30 μl nuclease-free water.

-

9.

Purify the amplified guide digest reaction using the PCR purification kit according to manufacturer instructions. Elute in 30 μl nuclease-free water or 10 mM Tris pH 8.

-

10.

Measure concentrations of the digested vector and the amplified guide PCR product by Nanodrop. Refer to UNIT A.3D (Gallagher, 2011) for details.

-

11.

Set up the ligation reaction as follows.

| Digested vector | |

| gRNA PCR product | 5× molar ratio to vector |

| T4 ligase buffer | 5 μl |

| T4 ligase | 1 μl |

| Nuclease-free water | to 20 μl |

| Total | 20 μl |

Use a total of 3–30 fmol or 3–30 ng DNA.

-

12.

Incubate at room temperature for 2 h or overnight at 14 °C.

-

13.

Thaw competent cells on ice for 5 min.

-

14.

Heat water bath or heat block to 42 °C.

-

15.

Add 1 μl of ligation reaction to 20 μl of competent cells, tap gently to mix, incubate for 5 min on ice.

-

16.

Heat shock competent cells for 30 sec at 42 °C, place back on ice.

-

17.

Add 200 μl SOC medium (room temperature), shake tubes at 37 °C for 5 min for cells to recover.

-

18.

Plate cells on LB agar ampicillin plate. Incubate overnight at 37 °C.

-

19.

Pick 2–4 colonies and inoculate each in 5 ml LB with 100 μg/ml ampicillin.

-

20.

Shake overnight at 37 °C.

-

21.

Purify plasmid DNA using miniprep kit according to manufacturer instructions, eluting in 50 μl nuclease-free water.

-

22.

Sanger sequence an aliquot (1–2 μg; usually 10 %) of sample using the primer AGCCCTTTGTACACCCTAAGC, which is about 400 bp upstream of the gRNA sequence. Sequencing primers could also be designed within the U6 promoter or other regions of the vector used, as long as it is >70–100 bp upstream of the gRNA sequence.

BASIC PROTOCOL 3

GENERATION OF HIGH TITER RETROVIRUSES

For efficient transduction of primary cells with retrovirus it is crucial to generate viral supernatants with high titers of retrovirus. For production of such supernatants the highly transfectable cell line, HEK293T, was used. We produce the viral supernatants by transient transfection using lipid-based transfection reagents, but this can also be done using other transfection protocols that have been optimized for transfection of HEK293T cells. Cells were grown to 60–80 % confluence followed by transfection with the gRNA-containing retroviral plasmid (from Basic Protocol 1 and 2), as well as a pCL-Eeco retroviral packaging plasmid with Mirus transfection reagents. For alternative methods for production of high titer virus see UNIT 9.11 (Pear, 2001).

For maximal transduction and mutagenesis efficiency, we recommend doing Basic Protocols 3–5 sequentially and without pausing between the Protocols. We will refer to the day of T cell activation as day 0. The following protocols will start with 1×106 T cells per guide as an example, but amounts can be scaled according to Tables 1 and 2.

Materials

Reagents and solutions

HEK293T cells (ATCC Cat# CRL-3216, RRID:CVCL_0063)

Complete EMEM (See recipe)

Opti-MEM (Thermo Fisher, Cat# 31985062)

Retroviral plasmid containing gRNA targeting gene of interest and GFP marker (see Basic Protocol 1–2)

pCL-Eco packaging plasmid (Addgene, Cat# 12371)

TransIT®−293 Transfection Reagent (Mirus, Cat# MIR2700)

Equipment

Tissue culture-hood

Incubator

Vortex

Cell culture wells

Day −2:

-

24 hours before transfection, plate 3.5×105 HEK293T cells per well of a 12-well plate in 1.2 ml Complete EMEM to reach a confluence of 60–80 % at the time of transfection.

See Table 1 for recommended HEK293T cell numbers 24 hours before transfection. It is recommended to plate 1–2 densities (close to those recommended in Table 1), e.g. 3×105 and 4×105 cells per well, and on the day of transfection use plates with the optimal confluency (60–80%). Depending on the state of the HEK293T cells, they will grow faster or slower resulting in higher or lower confluency.

It is important that the HEK293T cells used are in good conditions to produce high titer virus. The cells should never have reached 100 % confluency, and should be used at a relatively low passage. Therefore to keep the cells in a good state for transfection, keep the cells at a low passage number (preferably below passage 15–20). We generally passage these cells ~1:10 every 3 days.

Day −1:

-

2.

Warm up OPTIMEM and Mirus TransIT-293 reagents to room temperature before mixing the reagents.

-

3.

Mix OPTIMEM, Mirus TransIT-293 reagent, plasmid of interest, pCL-Eco packaging plasmid according to table 1. Vortex or mix solution briefly.

-

4.

Incubate at room temperature for 30 min.

Do not incubate for more than 45 minutes.

-

5.

Add solution dropwise to HEK293T cells and gently shake wells to disperse the drops in the wells. Place the transfected HEK293T cells back into the incubator.

The media will turn pink after addition of the transfection solution. It is important to add the transfection mix gently to not pipet off the HEK293T cells. Further, do not keep the cells out of the incubator for too long as the cells will release from the plastic if not kept warm.

Day 0: 24 hours post transfection

-

6.

Carefully collect the supernatant from the transfected HEK293T cells and store at 4 °C.

It is best to use fresh viral supernatents. Viral supernatants can be stored at 4 °C for a few days, but this will result in reduced titers. If storing supernatants for extended periods of time, one can store them at −80 °C, however this will also reduce titers.

Before collecting supernatant, it is useful to evaluate the transfection efficiency by inspecting expression of a fluorescent protein expressed by the gRNA-containing plasmid. If the transfection is efficient, by microscopy, most cells (50–80%) will be positive for the expressed fluorescent protein after 18–24 hours, and will include some cells with very high fluorescence.

-

7.

Gently add back 1.2 ml per well of Complete EMEM (as indicated in table 1) and return the HEK293T cells to the incubator. 293T cells are poorly adherent, particularly at room temperature.

Day 1: 48 hours post transfection

-

8.

Carefully collect supernatant and mix with supernatant collected in step 6. The total volume should be ~2 ml if transfecting in a 12 well.

BASIC PROTOCOL 4

ACTIVATION OF CAS9+ T CELLS

In this protocol, splenocytes are isolated from transgenic Cas9-expressing mice, enriched for naïve CD4+CD25-CD44-CD62L+ T cells by magnetic selection, and activated with plate-bound anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 for 24 hours. The cells are then spinoculated with viral supernatant generated from a retroviral construct encoding a gRNA and a GFP reporter. Following an additional 3–5 days of in vitro culture, the T cells can be used in downstream assays. The following protocol can also be used for purified naïve CD8+ T cells. Cell purification can be achieved using any magnetic separation kit, as well as by flow cytometric sorting.

Materials

Reagents and solutions:

PBS

Anti-CD3 (Bio X Cell Cat# BE0001–1, RRID:AB_1107634)

Anti-CD28 (Bio X Cell Cat# BE0015–1, RRID:AB_1107624)

R10 medium (see Reagents and Solutions)

70 μm cell strainer (Thermo Fisher, Cat# 22–363-548)

ACK lysis buffer (Thermo Fisher, Cat# A10492–01)

MACS buffer (see recipe)

MACS Naive CD4+ T Cell Isolation Kit, mouse (Miltenyi Biotec, Cat# 130–104-453)

MACS Naive CD8a+ T Cell Isolation Kit, mouse (Miltenyi Biotec, Cat# 130–096-543)

MACS LS columns (Miltenyi, Cat# 130–042-401)

MACS separation stand and magnets (Miltenyi)

Cas9-expressing mice (IMSR Cat# JAX:026179, RRID:IMSR_JAX:026179)

Equipment and consumables:

Dissection tools: fine forceps, scissors

15 ml conical tubes

Pre-cooled centrifuge (4 °C)

70 μm cell strainer (Thermo Fisher, Cat# 22–363-548)

Tissue culture-hood

Incubator

Cell culture plates

Day 0

-

Coat tissue culture plate with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 solution, 8 μg/ml of each, in PBS. Use 300 μl per well for a 24-well plate. Incubate at 37 °C for 1 h (day 0), or at 4 °C overnight (day −1).

Use azide-free, sterile stocks of anti-CD3 and anti-CD28. Concentrations of anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 can be varied depending on application. See UNIT 3.12 (Kruisbeek, Shevach, & Thornton, 2004), Alternate Protocol 1: Activation of Unprimed T Cells with Plate-Bound Antibodies, for details.

Isolate spleen (UNIT 3.1;(Kruisbeek, 2001)), and prepare single cell suspension by mashing spleen through a nylon filter cell strainer with the back end of a syringe plunger, and rinsing the filter with R10 medium (~20 ml per spleen).

Centrifuge cells, 1600 rpm, 5 min, 4 °C.

Lyse red blood cells with 1 ml ACK lysis buffer per spleen for 30 seconds at room temperature. Quench reaction by adding 5 ml R10 medium.

Centrifuge cells, 1600 rpm, 5 min, 4 °C.

-

Resuspend cells in MACS buffer and count cells. Adjust concentration to 250×106 cells/ml.

Expect around 50–100×106 cells/spleen. Lymph node cells can also be used.

-

Purify desired number of naïve CD4 (or CD8) T cells using the MACS kit according to manufacturer’s instructions.

Naïve wild-type CD4 T and CD8 T cells are present at ~10–20% and 8–15% frequencies in the spleen (of 60–100×106 cells), respectively. Frequencies are higher (~20 and 60% respectively) in the lymph nodes (of 15×106 cells). TCR transgenic T cells are present at 20–30% in the spleen (of 80–120×106 cells).

Centrifuge eluted cells, 1600 rpm, 5 min, 4 °C.

-

Resuspend cells in R10 medium at 1×106 cells/ml.

When purifying T cells by the MACS Naive CD4+ T Cell Isolation Kit, the yield depends on the amount of cells loaded onto the column; if loading a large amount of cells (~100×106 cells) the yield will be close to 100% of the T cells (i.e. assuming 20% CD4+ T cells, the final cell number will be ~20×106 CD4+ T cells), if loading a smaller amount of cells (~50×106 cells) the yield will be ~50% of the T cells (i.e. the final cell number will be ~5×106 CD4+ T cells).

Discard anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 coating solution from wells, wash wells once with R10 medium.

Plate 1 ml of T cells per well, centrifuge cells, 1600 rpm, 1 min, 4 °C.

-

Incubate at 37 °C for 24 h.

Cells should adhere to the plate and have increased in size compared to naïve cells.

Day 1

-

Proceed to retroviral transduction.

Further details and guidelines in other units may be useful for preparing single cell suspensions from mouse spleens and red blood cell lysis (UNIT 3.1;(Kruisbeek, 2001)), counting cells using a hemocytometer (APPENDIX 3A; (Strober, 2001)), and T cell purification using magnetic beads (UNIT 3.5A; (Thornton, 2003)).

ALTERNATE PROTOCOL 1

ACTIVATION OF TCR-TRANSGENIC T CELLS

For activation of primary mouse T cells, a useful tool widely used in the literature is T cell receptor transgenic T cells. For example, the OT-I TCR transgenic mouse model possesses clonal T cell receptors that recognize the specific chicken ovalbumin peptide, SIINFEKL, presented in the context of H-2Kb on target cells (Hogquist et al., 1994). For activation and transduction of antigen-specific primary CD8+ T cells, these cells may be used. Similar protocols can be used for antigen-specific CD4 T cells with MHCII-restricted transgenic TCRs such as OT-II (Barnden, Allison, Heath, & Carbone, 1998).

Materials

Reagents and solutions:

OT-I transgenic (IMSR Cat# JAX:003831, RRID:IMSR_JAX:003831) crossed to Cas9-expressing mice (IMSR Cat# JAX:026179, RRID:IMSR_JAX:026179)

ACK Lysis Buffer (Thermo Fisher, Cat# A10492–01)

R10 medium (See recipe)

OVA257–264 (SIINFEKL) (1 mM stock; Anaspec, Cat# AS-60193)

Recombinant human IL2 (stock at 106 IU/ml; R&D, Cat# 202-IL)

Equipment and consumables:

Dissection tools: fine forceps, scissors

15 ml conical tubes

Pre-cooled centrifuge (4 °C)

70 μm cell strainer (Thermo Fisher, Cat# 22–363-548)

Tissue culture-hood

Incubator

Cell culture plates

Day 0

Do step 1–5 from Basic Protocol 4

-

Resuspend cells in R10 medium and count.

Expect around 50–100×106 cells/spleen.

-

Plate 1×106 cells/ml in R10 medium + 10 nM OVA257–264 SIINFEKL peptide in individual wells of a 24-well plate, 6-well plate or a flask to activate cells.

Usually during the first 24 hours, the cell numbers will decrease by 25%, calculate cell numbers needed for experiment accordingly.

-

After 24 hours, the cells will be ready for the first spinoculation. See Basic Protocol 5 for description of the transduction.

Do not transduce cells earlier than 24 hours, as the cells will not be stimulated fully.

BASIC PROTOCOL 5

RETROVIRAL TRANSDUCTION

Efficient transduction of T cells with retrovirus requires cells in a proliferative state. After optimization of the transduction protocols, we found that double transductions 24 h and 36–40 h after activation of T cells gave maximal transduction efficiencies in ours and others’ experience (Metes, 2016). Several techniques exist for transduction of cells with virus in vitro, In our lab we have found spinoculations effective. During spinoculation, cells and viral supernatant are centrifugated to increase local interactions, enabling efficient transduction of T cells. To further facilitate the transduction, the interaction between virons and the cell surface is increased by blocking charge repulsion through the addition of polybrene to the media—this is important for retroviral transduction of cells. An alternative protocol for transduction of T cells using retroviron-coated plates can be found in UNIT 7.21C (Martínez-Barricarte et al., 2016).

Materials

Reagents and solutions:

Hexadimethrine Bromide ([Polybrene], Sigma-Aldrich Cat# H9268)

Recombinant human IL2 (rhIL-2, stock at 106 IU/ml; R&D, Cat# 202-IL)

Complete T cell media (See recipes)

Recombinant murine IL7 (Peprotech, Cat# 217–17) (optional)

Following cloning, production of retrovirus, and activation of T cells as described in Basic Protocol 1–4 (and alternative protocol 1) the cells are ready to be transduced with the gRNA-expressing retrovirus.

Day 1: 24 hours after initial activation of T cells

-

Warm up centrifuge to 30–37 °C.

Only some centrifuges allow this. If the centrifuge used does not allow heated centrifugations, room temperature will also work.

-

Prepare >500 μl viral supernatant per 1 mil T cells to be transduced by adding polybrene (hexadimethrine bromide) at 8 μg/ml and rhIL-2 at 10 IU/ml to viral supernatant prepared in Basic Protocol 3.

Using higher volumes of supernatant (1 ml per 1×106 cells) may result in a higher transduction efficiency.

-

If T cells are adherent (Basic Protocol 4), carefully remove medium from activated T cells and add viral supernatant containing polybrene and rhIL2 prepared in step 2. If T cells are nonadherent (Alternative Protocol 1), the activated cells will have to be counted and plated in wells for transduction. Plate cells according to table 2 and centrifugate at 1600 RPM, 5 min, 4 °C before removing medium and adding prepared viral supernatant.

With non-adherent cells it is also possible to resuspend the cells in viral supernatant before plating the cells in appropriate wells.

Centrifugate T cells and viral supernatants in prewarmed centrifuge >30 °C, 2000–2500 rpm for 1.5–2 h.

Carefully remove and discard viral supernatant.

Add fresh medium + 10 IU/ml rhIL-2 to T cells to a concentration of 1×106 cells/ml.

-

Incubate cells at 37 °C in a CO2 tissue culture incubator.

Day 2: 36–40 hours post activation of T cells (optional)

Spin down, remove media, add fresh viral supernatants, and re-infect as in steps 1–7 to conduct a second transduction for increased transduction efficiency.

The first transduction should result in transduction efficiencies of 50–80%. The second transduction is optional and increases transduction efficiency by ~10–15% (to 60–95% depending on plasmid, transfection and cells used).

From day 2 to day 6–7 following activation, keep T cells at a density of 0.5–1×106 cells/ml media containing 10 IU/ml rhIL2. Supply the cells with fresh media and rhIL2 every 1–2 days to keep the cells in a proliferative and active state until the assay of interest is conducted. Loss of protein varies from protein to protein, but most proteins will be lost 3 days post transduction and it therefore possible to assay the cells from day 4–6 and onwards.

Following culture, T cells can also be adoptively transferred for downstream in vivo experiments. To promote the survival of the cultured T cells in vivo post-transfer, the day before the transfer, the T cells are pelleted to remove the rhIL-2-containing R10, washed once with plain R10, then replated in fresh R10 with 2 ng/ml IL-7 overnight. On the day of transfer, cells are washed three times with plain serum-free RPMI-1640, and injected immediately. In general, the transferred cells are allowed to equilibrate in vivo for 1–3 days post injection before the recipient mice are challenged with infection or immunization (Chen et al., 2014).

Starting at day 4 post-activation, the T cells can be analyzed for protein loss, such as by flow cytometry. In general, flow cytometry analysis of the transduction efficiency (e.g. %GFP+) should be performed prior to any other assays, to determine whether it is necessary to enrich for the GFP+ cells by cell sorting. Gating on live T cells (stained with a viability dye and CD4 or CD8 antibody), we reproducibly find that 60–95% are GFP+. See UNIT 5.4 for details on performing flow cytometry analysis (Maciorowski, Chattopadhyay, & Jain, 2017).

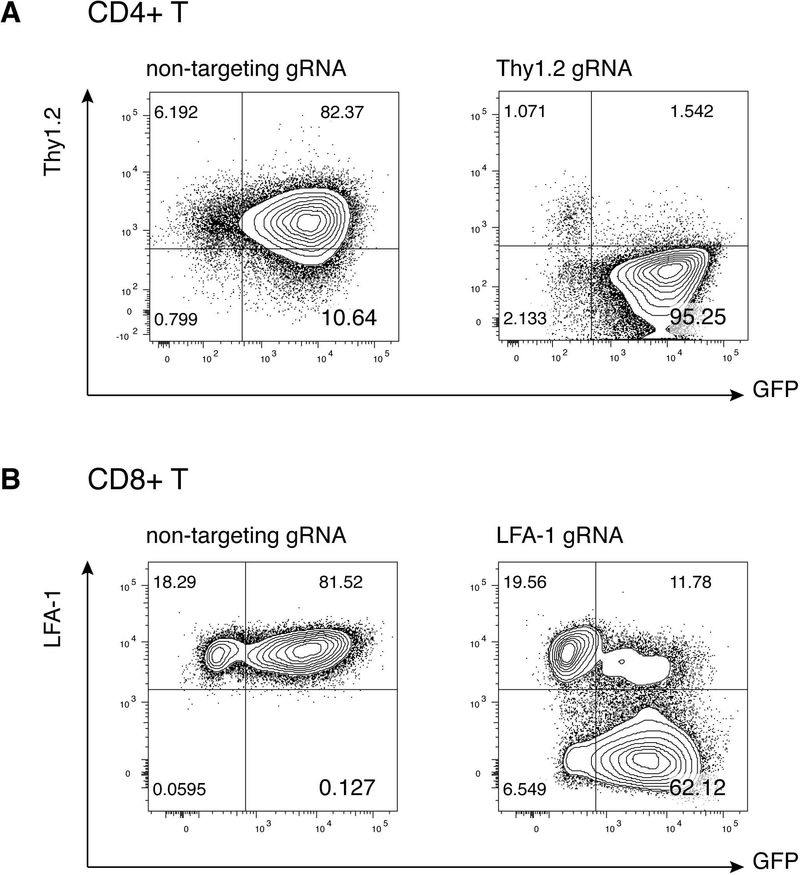

For a target protein that is measurable by flow cytometry, within the GFP+ population, nearly all of the cells should have lost the protein of interest (Figure 3). We have also analyzed knockout efficiencies by Western blot of the targeted protein, with similar results.

Figure 3. Anticipated results.

(A) Cas9+ CD4 T cells were activated and transduced with vectors encoding a control non-targeting or Thy1.2 guide RNA. On day 6 post-activation, cells were stained with Fixable Live/Dead Aqua and antibodies for CD4 and Thy1.2. Live T cells were gated as Aqua-CD4+.

(B) Cas9+ OT-I CD8+ T cells were activated and transduced with vectors encoding a control non-targeting or LFA-1 guide RNA. On day 6 post-activation, cells were stained with Fixable Live/Dead Near-IR and antibodies for CD8 and LFA-1. Live T cells were gated as Near-IR-CD8+. Cells were stained with Thy1.1 antibody (BioLegend Cat# 140308, RRID:AB_10641145) or CD11a antibody (BioLegend Cat# 101114, RRID:AB_2128744) for 25 minutes in FACS buffer at 4 °C.

REAGENTS AND SOLUTIONS

MACS Buffer

500 ml PBS

2 ml 500 mM EDTA

2.5 g BSA

Sterile filter

Store at 4 °C

R10 medium

500 ml RPMI-1640 (Thermo Fisher, Cat# 21870–076)

50 ml fetal bovine serum (Seradigm, Cat# 1500–500)

5 ml penicillin/streptomycin (Thermo Fisher, Cat# 15140–122)

5 ml L-glutamine (200 mM stock) (if not already included in RPMI) (Thermo Fisher, Cat# 25030–081)

0.5 ml 2-mercaptoethanol (Thermo Fisher, Cat# 21985–023)

Store at 4 °C

Complete EMEM medium

EMEM media (ATCC, Cat# 30–2003)

50 ml fetal bovine serum (Seradigm, Cat# 1500–500)

5 ml L-glutamine (200 mM stock, Thermo Fisher, Cat# 25030081)

5 ml penicillin/streptomycin (Thermo Fisher, Cat# 15140–122)

Store at 4 °C

COMMENTARY

Background Information

To date, the most widely used CRISPR system is the one we have described in this protocol: derived from Streptococcus pyogenes, which uses a Cas9 endonuclease and a 17–20 nucleotide gRNA sequence to make double-stranded breaks in the target genomic DNA. Fortuituously, this system is highly applicable across cell types and species, due to the minimal components of Cas9 and sgRNA, and is extremely efficient in knocking out genes, due to the error-prone nature of NHEJ DNA repair after CRISPR cutting. Correspondingly, the bulk of early CRISPR studies applied this knockout technology to basic research questions in model organisms and systems, including immune cell lines such as K562, Jurkat, and EL-4. However, its versatility and ease have allowed its rapid spread to primary immunological cell types such as myeloid cells (Jaitin et al., 2016; Parnas et al., 2015), B cells (Chu, Graf, et al., 2016), and T cells (Singer et al., 2016). As a complementary tool, human Jurkat T cells lines that stably express Cas9 and its variants have been created, allowing genetic perturbation in biochemical and imaging studies (Chi, Weiss, & Wang, 2016). CRISPR has also greatly accelerated the process of making transgenic mouse models (H. Wang et al., 2013; Yang et al., 2013), and opened the door to engineering organisms previously intractable to transgenics technology.

Additionally, CRISPR can be used for precise genomic engineering, by simultaneously adding an exogenous DNA template with the desired “cargo” flanked by homology arms that correspond to the genomic sequences around the Cas9 cut site (Cong et al., 2013; Mali, Yang, et al., 2013). This strategy takes advantage of homology-directed repair, an alternative DNA repair pathway, which aligns the template with the genomic DNA using the homologous arms, and then replaces the endogenous genomic DNA with the template in an error-free manner. This “knock-in” approach allows the introduction of novel sequences into an exact genomic location, such as point mutations. Currently, genetic knock-in at a specific genomic site is less efficient compared to knock-outs. Ongoing research into the molecular mechanisms of DNA repair after Cas9 cutting have led to improved cargo design rules to increase knock-in efficiency (Richardson, Ray, DeWitt, Curie, & Corn, 2016), and in the future may reveal strategies to preferentially bias the cell towards homologous recombination as opposed to NHEJ. More recently, base-editing using a conjugate of nuclease-dead spCas9 and base conversion enzymes, such as cytidine deaminase, has emerged as an alternative strategy to engineer small mutations (see further discussion below).

Conceptually, the Cas9-sgRNA complex can be considered a highly specific search tool for DNA sequences, and by coupling this modality to other functional domains, a wide range of powerful research tools have been developed. There are scenarios in which genetic control at the transcriptional level is preferred over a complete genetic knockout. A “nuclease-dead” point mutant of spCas9 was engineered to lack endonuclease activity and fused to transcriptional repressor or activator elements, allowing the Cas9-sgRNA complex to bind the target gene’s promoter and silence (CRISPRi) or boost (CRISPRa) its transcriptional levels, respectively (L. A. Gilbert et al., 2014; L. a Gilbert et al., 2013; Konermann et al., 2014). Dead Cas9 has also been conjugated to chromatin modifying enzymes to tune target gene transcription by epigenetic modifications such as methylation and acetylation (Hilton et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2016).

CRISPR holds great promise for therapeutic applications, and there is currently significant interest in the design and clinical testing of genetically-edited T cells for adoptive cell therapy, mostly for the treatment of cancer, but also for autoimmune diseases and infectious diseases. For cancer applications, current efforts are focused on CRISPR-mediated knock-in of exogenous tumor-specific T cell receptors or chimeric antigen receptors into the endogenous T cell receptor loci, to drive physiological expression and signaling of these receptors. In parallel, CRISPR is also being used to knock out inhibitory molecules such as PD-1, in order to boost the function and persistence of the engineered T cells post-adoptive transfer.

Two ongoing challenges in CRISPR technology development are to reduce off-targeting and to increase the editable space within the genome. These two parameters are particularly important for precision gene editing for therapeutic purposes. Potential off-targeting in oncogenic regions is a concern for cell therapies with long in vivo persistence, such as HSC transplantation or CAR T cell therapy. Off-targeting of CRISPR has been a concern since the development of this technology, and the assays and algorithms to characterize and predict off-targeting continue to be refined (Listgarten et al., 2018). Some previous studies have suggested that truncating the gRNA to 17–18 nucleotides can improve specificity (Fu, Sander, Reyon, Cascio, & Joung, 2014), and that targeting known functional domains of proteins yield higher knockout efficiencies than non-selectively targeting exons (Shi et al., 2015). To increase the specificity of wild-type spCas9, one strategy is to couple nuclease-dead spCas9 to FokI nuclease, which requires dimerization for DNA cleavage, thus requiring two gRNAs within ~20 base pairs proximity for DNA cleavage (Aouida et al., 2015; Guilinger, Thompson, & Liu, 2014; Tsai et al., 2014). A similar strategy is to use the Cas9 D10A mutant, which makes single-stranded nicks instead of double-stranded breaks (Mali, Aach, et al., 2013; Ran et al., 2013). This allows the use of gRNA pairs that will only lead to editing when the two nicks are in proximity.

CRISPR knock-in studies have shown that HDR efficiency drops off sharply as a function of the distance between the targeted mutation and the gRNA cleavage site (Paquet et al., 2016). In the cases where the disease-causing mutation is a single base pair, having a broad spectrum of PAM sequences increases the probability that a suitable gRNA can be found in the proximity of the target base. With SpCas9 and its PAM NGG, it is estimated that there is a gRNA sequence every 8–12 base pairs in the human genome (Cong et al., 2013; Hsu et al., 2013). While this frequency is certainly high enough for gene knockouts, it may be limiting for gene editing to correct mutated alleles at specific locations, such as SNPs.

Bioinformatics mining of bacterial and archaea genomes has extended the toolbox of nucleases beyond S. pyogenes spCas9 and its PAM NGG. For example, S. aureus Cas9 recognizes the PAM sequence NNGRRT (Ran et al., 2015), while Cpf1 recognizes a short T-rich PAM sequence (Zetsche et al., 2015). These alternative nucleases could allow editing in genomic regions where there is no suitable PAM for spCas9. Structural and protein engineering studies have also generated new variants of Cas9 with improved specificity (Kleinstiver et al., 2016; Slaymaker et al., 2016) and/or expanded PAM sequences (Hu et al., 2018; Kleinstiver et al., 2015). As an alternate strategy, nuclease-dead Cas9 has been coupled to base-editing nucleases such as cytidine deaminase (Hess et al., 2016; Kim et al., 2017; Komor, Kim, Packer, Zuris, & Liu, 2016; Matsoukas, 2018). This approach may circumvent the challenges of knock-ins, and allow editing of small mutations that do not require replacement by a large cargo.

Finally, in contrast to Cas9, which targets genomic DNA, a number of CRISPR Cas13 systems have now been found to allow RNA editing without the constraints of PAM sequences (Abudayyeh et al., 2017, 2016; Cox et al., 2017; Konermann et al., 2018; Yan et al., 2018). These systems would allow broad, reversible control of gene expression while avoiding the safety concerns of genomic editing.

Critical Parameters

Guide RNA Design

For Cas9 to bind to the target site, it is essential to have a Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) sequence (which for the common spCas9 is NGG) immediately following the target site. However, not all gRNAs with a following PAM-sequence will result in efficient mutagenesis.

Several other factors determine the efficiency of mutagenesis. For disruption of protein coding sequences, the location of the target site should be in an exon that is shared between isoforms of the protein of interest to ensure disruption of all isoforms of the protein, and should be located downstream of potential alternative start codons to reduce the risk of producing truncated proteins. However, avoid choosing a target sequence that is close to the C-terminus, as this increases the chance of producing truncated proteins with residual function.

To increase specificity and efficiency, algorithms predicting off-targets (Hsu et al., 2013) and on-target efficiencies (Doench et al., 2016, 2014) of a specific gRNA have been developed. A recommended high off-target score of 50 (out of 100) or greater indicates that there are few predicted off targets (when using algorithms based on Hsu et al., 2013). Computed potential off-target sites are more likely to be problematic when they fall in coding gene regions.

Similarly, algorithms can predict the on-target activity; a high on-target score indicates that the gRNA is predicted to initiate high activity cutting of the target site. Thus, it is preferred to choose gRNAs with both a high off-target and on-target score. The first version of the on-target scoring algorithm predicted that about two-thirds of the most active experimentally-validated gRNA sequences have scores of 60 (out of 100) or above (Doench et al., 2014). However, gRNAs are not equally distributed across the 1–100 score range, and gRNAs with scores above 60 may not be present in the region of interest.

Finally, when designing gRNAs, be sure to choose the appropriate reference genome, particularly for non-C57BL/6 mouse strains that have SNPs. gRNA activity is sensitive to mismatches near the PAM sequence, and off-targeting scores may also be inaccurate if searching the wrong strain’s genome. If using restriction enzymes for cloning, as described in Basic Protocol 2, avoid gRNA sequences that contain the same restriction enzyme sequences.

Guide RNA Construct Cloning

Although we use a construct containing a U6 promoter, other small RNA promoters such as H1 (Ranganathan, Wahlin, Maruotti, & Zack, 2014) have also been used to drive gRNA transcription, and therefore, many vectors for shRNA expression should be adaptable for CRISPR. Many gRNA vectors are also available from Addgene, such as lentiGuide-Puro (Addgene #52963) (Sanjana, Shalem, & Zhang, 2014), which uses a type II restriction enzyme site to leave distinct 4 bp overhangs at the gRNA insert site. The gRNA sequence is ordered as two 24 bp complementary oligos, which after annealing and phosphorylating forms a duplex with the corresponding 4 bp overhangs. This duplex is directly ligated into the digested vector. Each system uses a different cloning strategy for the insertion of the gRNA sequence, but have similar workflows as the protocol provided, starting from the ligation step.

Transfection and Transduction

For optimal transfection efficiency, the HEK 293T cells should be passaged regularly, discarded after ~20 passages, and prevented from reaching 100% confluence during culture, as this reduces the transfection efficiency. For a gRNA construct expressing a fluorescent reporter such as GFP, approximately 24 hours following transfection, a good transfection will result in GFP expression in the majority of the 293T cells, although the brightness will vary between cells. Uniformly dim or sparse GFP expression in the 293T cells almost always results in poor transduction efficiencies.

To achieve high transduction efficiencies, T cells should be healthy and robustly activated at the time of transduction. T cells should have >80% viability (by exclusion of Trypan Blue or fixable viability dye staining), and >90% expression of the activation markers CD44 and/or CD25. Strong stimulation through the T cell receptors, such as with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 (Basic Protocol 4), or with cognate peptide for transgenic TCRs (Alternate Protocol 1), result in an optimal transduction time window around 24 hours post-activation.

If culturing T cells with IL-2 for in vitro expansion, observe T cell viability and numbers carefully, as they will proliferate very rapidly after recovering from transduction, and may deplete the media in a day. Daily replating into successively larger volumes of fresh media with IL-2, or splitting the T cells into fresh media, is recommended.

When comparing phenotypes of the functional knock-out, the best comparison is between GFP+ T cells transduced with the test gRNA, versus GFP+ T cells transduced with a control gRNA. This is a better comparison than against GFP- T cells or untransduced T cells, as the transduced GFP+ cells are likely to be in a more activated state or cell cycle phase compared to cells that were not infected.

Troubleshooting

Choosing a gRNA sequence with good on-target and off-target scores should give high knockout rates. However, computational algorithms for gRNA activity and specificity are continuously being improved, and high-scoring gRNAs may occasionally fail experimentally. Trying 3–4 gRNAs per gene should yield at least 2 with high activity.

Anticipated Results

To confirm that the target genomic DNA sequence has been mutagenized, GFP+ cells can be sorted and the genomic DNA can be isolated for analysis. We use a fluorescent PCR-based technique that amplifies the region around the target site and sensitively measures the amplicon size on a capillary sequencer (Carrington, Varshney, Burgess, & Sood, 2015). The error-prone NHEJ repair mechanism should introduce a spectrum of small (1–20 bp) insertions or deletions, which show up as shifted peaks in the chromatogram (see Fig 1 bottom) relative to amplicons from T cells transduced with a control non-targeting gRNA or untransduced T cells. While this technique does not tell us the sequence of the mutated gDNA, we find it to be a rapid screen that is more sensitive and informative than the SURVEYOR assay. An alternative is to PCR amplify around the target sequence and Sanger sequence. Usually, multiple mutations will result, and can be deconvoluted using the TIDE algorithm (Brinkman, Chen, Amendola, & Van Steensel, 2014), which is available through Desktop Genetics (see Internet Resources).

Time Considerations

The gRNAs can be designed in 1 day. Subcloning of the retroviral construct requires up to 1 week. Plasmid transfection requires 3 days, and can be done immediately prior to T cell culture or in advance (see Basic Protocol 3). T cell culturing will require at 4–6 days to acquire full knockout cells, depending on the needs of the downstream assays. Flow cytometry or Western blot analysis of gene knockout can be completed in less than a day. See Figure 1 for overview.

Significance Statement.

The CRISPR/Cas9 mutagenesis has emerged as a powerful genomic editing tool. Here we described the use CRISPR/Cas9 to mutagenize primary mouse T cells, allowing new advances in the genetic dissection of T cell function that can advance our understanding of T cell biology, signaling and function.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Funding was provided in part by the intramural programs of NHGRI and NIAID. KHJ is in the Wellcome Trust-NIH Graduate Student Program.

Footnotes

INTERNET RESOURCES

Two useful websites for gRNA design are Benchling (www.benchling.com, RRID:SCR_013955) and Desktop Genetics (www.deskgen.com). Both are free for academic researchers.

LITERATURE CITED

- Abudayyeh OO, Gootenberg JS, Essletzbichler P, Han S, Joung J, Belanto JJ, … Zhang F (2017). RNA targeting with CRISPR–Cas13. Nature, 550(7675), 280–284. 10.1038/nature24049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abudayyeh OO, Gootenberg JS, Konermann S, Joung J, Slaymaker IM, Cox DBT, … Zhang F (2016). C2c2 is a single-component programmable RNA-guided RNA-targeting CRISPR effector. Science, 353(6299), aaf5573 10.1126/science.aaf5573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aouida M, Eid A, Ali Z, Cradick T, Lee C, Deshmukh H, … Mahfouz M (2015). Efficient fdCas9 Synthetic Endonuclease with Improved Specificity for Precise Genome Engineering. PLOS ONE, 10(7), e0133373 10.1371/journal.pone.0133373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnden MJ, Allison J, Heath WR, & Carbone FR (1998). Defective TCR expression in transgenic mice constructed using cDNA-based α- and β-chain genes under the control of heterologous regulatory elements. Immunology and Cell Biology, 76(1), 34–40. 10.1046/j.1440-1711.1998.00709.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinkman EK, Chen T, Amendola M, & Van Steensel B (2014). Easy quantitative assessment of genome editing by sequence trace decomposition. Nucleic Acids Research, 42(22), e168–e168. 10.1093/nar/gku936 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrington B, Varshney GK, Burgess SM, & Sood R (2015). CRISPR-STAT: An easy and reliable PCR-based method to evaluate target-specific sgRNA activity. Nucleic Acids Research, 43(22), 1–8. 10.1093/nar/gkv802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen R, Bélanger S, Frederick MA, Li B, Johnston RJ, Xiao N, … Pipkin ME (2014). In vivo RNA interference screens identify regulators of antiviral CD4+ and CD8+ T cell differentiation. Immunity, 41(2), 325–338. 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.08.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi S, Weiss A, & Wang H (2016). A CRISPR-Based Toolbox for Studying T Cell Signal Transduction. BioMed Research International, 2016, 1–10. 10.1155/2016/5052369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu VT, Graf R, Wirtz T, Weber T, Favret J, Li X, … Rajewsky K (2016). Efficient CRISPR-mediated mutagenesis in primary immune cells using CrispRGold and a C57BL/6 Cas9 transgenic mouse line. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 113(44), 12514–12519. 10.1073/pnas.1613884113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu VT, Weber T, Graf R, Sommermann T, Petsch K, Sack U, … Kühn R (2016). Efficient generation of Rosa26 knock-in mice using CRISPR/Cas9 in C57BL/6 zygotes. BMC Biotechnology, 16(1), 4 10.1186/s12896-016-0234-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cong L, Ran FA, Cox D, Lin S, Barretto R, Habib N, … Zhang F (2013). Multiplex genome engineering using CRISPR/Cas systems. Science, 339(6121), 819–823. 10.1126/science.1231143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox DBT, Gootenberg JS, Abudayyeh OO, Franklin B, Kellner MJ, Joung J, & Zhang F (2017). RNA editing with CRISPR-Cas13. Science, 358(6366), 1019–1027. 10.1126/science.aaq0180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doench JG, Fusi N, Sullender M, Hegde M, Vaimberg EW, Donovan KF, … Root DE (2016). Optimized sgRNA design to maximize activity and minimize off-target effects of CRISPR-Cas9. Nature Biotechnology, 34(November 2015), 1–12. 10.1038/nbt.3437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doench JG, Hartenian E, Graham DB, Tothova Z, Hegde M, Smith I, … Root DE (2014). Rational design of highly active sgRNAs for CRISPR-Cas9–mediated gene inactivation. Nature Biotechnology, 32(12), 1262–1267. 10.1038/nbt.3026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Y, Sander JD, Reyon D, Cascio VM, & Joung JK (2014). Improving CRISPR-Cas nuclease specificity using truncated guide RNAs. Nature Biotechnology, 32(3), 279–284. 10.1038/nbt.2808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher SR (2011). Quantitation of DNA and RNA with absorption and fluorescence spectroscopy In Current Protocols in Molecular Biology. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 10.1002/0471142727.mba03ds93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert LA, Horlbeck MA, Adamson B, Villalta JE, Chen Y, Whitehead EH, … Weissman JS (2014). Genome-Scale CRISPR-Mediated Control of Gene Repression and Activation. Cell, 159(3), 647–661. 10.1016/j.cell.2014.09.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert L. a, Larson MH, Morsut L, Liu Z, Brar G. a, Torres SE, … Qi LS (2013). CRISPR-mediated modular RNA-guided regulation of transcription in eukaryotes. Cell, 154(2), 442–451. 10.1016/j.cell.2013.06.044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guilinger JP, Thompson DB, & Liu DR (2014). Fusion of catalytically inactive Cas9 to FokI nuclease improves the specificity of genome modification. Nature Biotechnology, 32(6), 577–582. 10.1038/nbt.2909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess GT, Frésard L, Han K, Lee CH, Li A, Cimprich KA, … Bassik MC (2016). Directed evolution using dCas9-targeted somatic hypermutation in mammalian cells. Nature Methods, 13(12), 1036–1042. 10.1038/nmeth.4038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilton IB, D’Ippolito AM, Vockley CM, Thakore PI, Crawford GE, Reddy TE, & Gersbach CA (2015). Epigenome editing by a CRISPR-Cas9-based acetyltransferase activates genes from promoters and enhancers. Nature Biotechnology, 33(5), 510–517. 10.1038/nbt.3199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogquist KA, Jameson SC, Heath WR, Howard JL, Bevan MJ, & Carbone FR (1994). T cell receptor antagonist peptides induce positive selection. Cell, 76(1), 17–27. 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90169-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvath P, & Barrangou R (2010). CRISPR/Cas, the Immune System of Bacteria and Archaea. Science, 327(5962), 167–170. 10.1126/science.1179555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu PD, Scott DA, Weinstein JA, Ran FA, Konermann S, Agarwala V, … Zhang F (2013). DNA targeting specificity of RNA-guided Cas9 nucleases. Nature Biotechnology, 31(9), 827–832. 10.1038/nbt.2647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu JH, Miller SM, Geurts MH, Tang W, Chen L, Sun N, … Liu DR (2018). Evolved Cas9 variants with broad PAM compatibility and high DNA specificity. Nature, 556(7699), 57–63. 10.1038/nature26155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaitin DA, Weiner A, Yofe I, Lara-Astiaso D, Keren-Shaul H, David E, … Amit I (2016). Dissecting Immune Circuits by Linking CRISPR-Pooled Screens with Single-Cell RNA-Seq. Cell, 167(7), 1883–1896.e15. 10.1016/j.cell.2016.11.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jinek M, East A, Cheng A, Lin S, Ma E, & Doudna J (2013). RNA-programmed genome editing in human cells. ELife, 2013(2), e00471 10.7554/eLife.00471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim YB, Komor AC, Levy JM, Packer MS, Zhao KT, & Liu DR (2017). Increasing the genome-targeting scope and precision of base editing with engineered Cas9-cytidine deaminase fusions. Nature Biotechnology, 35(4), 371–376. 10.1038/nbt.3803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinstiver BP, Pattanayak V, Prew MS, Tsai SQ, Nguyen NT, Zheng Z, & Joung JK (2016). High-fidelity CRISPR–Cas9 nucleases with no detectable genome-wide off-target effects. Nature, 529(7587), 490–495. 10.1038/nature16526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinstiver BP, Prew MS, Tsai SQ, Topkar VV, Nguyen NT, Zheng Z, … Joung JK (2015). Engineered CRISPR-Cas9 nucleases with altered PAM specificities. Nature, 523(7561), 481–485. 10.1038/nature14592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koike-Yusa H, Li Y, Tan E-P, Velasco-Herrera MDC, & Yusa K (2014). Genome-wide recessive genetic screening in mammalian cells with a lentiviral CRISPR-guide RNA library. Nature Biotechnology, 32(3), 267–273. 10.1038/nbt.2800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komor AC, Kim YB, Packer MS, Zuris JA, & Liu DR (2016). Programmable editing of a target base in genomic DNA without double-stranded DNA cleavage. Nature, 533(7603), 420–424. 10.1038/nature17946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konermann S, Brigham MD, Trevino AE, Joung J, Abudayyeh OO, Barcena C, … Zhang F (2014). Genome-scale transcriptional activation by an engineered CRISPR-Cas9 complex. Nature, 517(7536), 583–588. 10.1038/nature14136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konermann S, Lotfy P, Brideau NJ, Oki J, Shokhirev MN, & Hsu PD (2018). Transcriptome Engineering with RNA-Targeting Type VI-D CRISPR Effectors. Cell, 173(3), 665–676.e14. 10.1016/j.cell.2018.02.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruisbeek AM (2001). Isolation of Mouse Mononuclear Cells In Current Protocols in Immunology. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 10.1002/0471142735.im0301s39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruisbeek AM, Shevach E, & Thornton AM (2004). Proliferative Assays for T Cell Function In Current Protocols in Immunology. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 10.1002/0471142735.im0312s60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Listgarten J, Weinstein M, Kleinstiver BP, Sousa AA, Joung JK, Crawford J, … Fusi N (2018). Prediction of off-target activities for the end-to-end design of CRISPR guide RNAs. Nature Biomedical Engineering, 2(1), 38–47. 10.1038/s41551-017-0178-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu XS, Wu H, Ji X, Stelzer Y, Wu X, Czauderna S, … Jaenisch R (2016). Editing DNA Methylation in the Mammalian Genome. Cell, 167(1), 233–247.e17. 10.1016/j.cell.2016.08.056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maciorowski Z, Chattopadhyay PK, & Jain P (2017). Basic multicolor flow cytometry In Current Protocols in Immunology (Vol. 2017, p. 5.4.1–5.4.38). Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 10.1002/cpim.26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mali P, Aach J, Stranges PB, Esvelt KM, Moosburner M, Kosuri S, … Church GM (2013). CAS9 transcriptional activators for target specificity screening and paired nickases for cooperative genome engineering. Nature Biotechnology, 31(9), 833–838. 10.1038/nbt.2675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mali P, Yang L, Esvelt KM, Aach J, Guell M, DiCarlo JE, … Church GM (2013). RNA-guided human genome engineering via Cas9. Science, 339(6121), 823–826. 10.1126/science.1232033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malina A, Katigbak A, Cencic R, Maïga RI, Robert F, Miura H, & Pelletier J (2014). Adapting CRISPR/Cas9 for functional genomics screens. Methods in Enzymology, 546(C), 193–213. 10.1016/B978-0-12-801185-0.00010-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Barricarte R, de Jong SJ, Markle J, de Paus R, Boisson-Dupuis S, Bustamante J, … Casanova J-L (2016). Transduction of Herpesvirus saimiri -Transformed T Cells with Exogenous Genes of Interest In Current Protocols in Immunology (p. 7.21C.1–7.21C.12). Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 10.1002/cpim.15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsoukas IG (2018). Commentary: Programmable base editing of A·T to G·C in genomic DNA without DNA cleavage. Frontiers in Genetics, 9(FEB), 464–471. 10.3389/fgene.2018.00021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metes DM (2016). T follicular helper cells in transplantation: Specialized helpers turned rogue In Espeli M & Linterman M (Eds.), Transplantation (Vol. 100, pp. 1603–1604). Humana Press, New York, NY: 10.1097/TP.0000000000001218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paquet D, Kwart D, Chen A, Sproul A, Jacob S, Teo S, … Tessier-Lavigne M (2016). Efficient introduction of specific homozygous and heterozygous mutations using CRISPR/Cas9. Nature, 533(7601), 125–129. 10.1038/nature17664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parnas O, Jovanovic M, Eisenhaure TM, Herbst RH, Dixit A, Ye CJ, … Regev A (2015). A Genome-wide CRISPR Screen in Primary Immune Cells to Dissect Regulatory Networks. Cell, 162(3), 675–686. 10.1016/j.cell.2015.06.059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pear W (2001). T ransient Transfection Methods for Preparation of High-Titer Retroviral Supernatants In Current Protocols in Molecular Biology. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 10.1002/0471142727.mb0911s36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Platt RJ, Chen S, Zhou Y, Yim MJ, Swiech L, Kempton HR, … Zhang F (2014). CRISPR-Cas9 Knockin Mice for Genome Editing and Cancer Modeling. Cell, 159(2), 440–455. 10.1016/j.cell.2014.09.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ran FA, Cong L, Yan WX, Scott DA, Gootenberg JS, Kriz AJ, … Zhang F (2015). In vivo genome editing using Staphylococcus aureus Cas9. Nature, 520(7546), 186–191. 10.1038/nature14299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ran FA, Hsu PD, Lin C-Y, Gootenberg JS, Konermann S, Trevino AE, … Zhang F (2013). Double Nicking by RNA-Guided CRISPR Cas9 for Enhanced Genome Editing Specificity. Cell, 154(6), 1380–1389. 10.1016/j.cell.2013.08.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranganathan V, Wahlin K, Maruotti J, & Zack DJ (2014). Expansion of the CRISPR–Cas9 genome targeting space through the use of H1 promoter-expressed guide RNAs. Nature Communications, 5 10.1038/ncomms5516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson CD, Ray GJ, DeWitt MA, Curie GL, & Corn JE (2016). Enhancing homology-directed genome editing by catalytically active and inactive CRISPR-Cas9 using asymmetric donor DNA. Nature Biotechnology, 34(3), 339–344. 10.1038/nbt.3481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanjana NE, Shalem O, & Zhang F (2014). Improved vectors and genome-wide libraries for CRISPR screening. Nature Methods, 11(8), 783–784. 10.1038/nmeth.3047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumann K, Lin S, Boyer E, Simeonov DR, Subramaniam M, Gate RE, … Marson A (2015). Generation of knock-in primary human T cells using Cas9 ribonucleoproteins. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112(33), 201512503 10.1073/pnas.1512503112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seki A, & Rutz S (2018). Optimized RNP transfection for highly efficient CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene knockout in primary T cells. The Journal of Experimental Medicine, jem.20171626. 10.1084/jem.20171626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shalem O, Sanjana NE, Hartenian E, Shi X, Scott DA, Mikkelsen TS, … Zhang F (2014). Genome-scale CRISPR-Cas9 knockout screening in human cells. Science, 343(6166), 84–87. 10.1126/science.1247005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shalem O, Sanjana NE, & Zhang F (2015). High-throughput functional genomics using CRISPR-Cas9. Nature Reviews Genetics, 16(5), 299–311. 10.1038/nrg3899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi J, Wang E, Milazzo JP, Wang Z, Kinney JB, & Vakoc CR (2015). Discovery of cancer drug targets by CRISPR-Cas9 screening of protein domains. Nature Biotechnology. 10.1038/nbt.3235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer M, Wang C, Cong L, Marjanovic ND, Kowalczyk MS, Zhang H, … Anderson AC (2016). A Distinct Gene Module for Dysfunction Uncoupled from Activation in Tumor-Infiltrating T Cells. Cell, 166(6), 1500–1511.e9. 10.1016/j.cell.2016.08.052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slaymaker IM, Gao L, Zetsche B, Scott DA, Yan WX, & Zhang F (2016). Rationally engineered Cas9 nucleases with improved specificity. Science, 351(6268), 84–88. 10.1126/science.aad5227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strober W (2001). Monitoring Cell Growth In Current Protocols in Immunology. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 10.1002/0471142735.ima03as21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornton AM (2003). Fractionation of T and B Cells Using Magnetic Beads In Current Protocols in Immunology. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 10.1002/0471142735.im0305as57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai SQ, Wyvekens N, Khayter C, Foden JA, Thapar V, Reyon D, … Joung JK (2014). Dimeric CRISPR RNA-guided FokI nucleases for highly specific genome editing. Nature Biotechnology, 32(6), 569–576. 10.1038/nbt.2908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Yang H, Shivalila CS, Dawlaty MM, Cheng AW, Zhang F, & Jaenisch R (2013). One-Step Generation of Mice Carrying Mutations in Multiple Genes by CRISPR/Cas-Mediated Genome Engineering. Cell, 153(4), 910–918. 10.1016/j.cell.2013.04.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang T, Wei JJ, Sabatini DM, & Lander ES (2014). Genetic screens in human cells using the CRISPR-Cas9 system. Science, 343(6166), 80–84. 10.1126/science.1246981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan WX, Chong S, Zhang H, Makarova KS, Koonin EV, Cheng DR, & Scott DA (2018). Cas13d Is a Compact RNA-Targeting Type VI CRISPR Effector Positively Modulated by a WYL-Domain-Containing Accessory Protein. Molecular Cell, 70(2), 327–339.e5. 10.1016/j.molcel.2018.02.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H, Wang H, Shivalila CS, Cheng AW, Shi L, & Jaenisch R (2013). One-step generation of mice carrying reporter and conditional alleles by CRISPR/Cas-mediated genome engineering. Cell, 154(6), 1370–1379. 10.1016/j.cell.2013.08.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zetsche B, Gootenberg JS, Abudayyeh OO, Slaymaker IM, Makarova KS, Essletzbichler P, … Zhang F (2015). Cpf1 Is a Single RNA-Guided Endonuclease of a Class 2 CRISPR-Cas System. Cell, 163(3), 759–771. 10.1016/j.cell.2015.09.038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]