Abstract

The APC/C E3 ligase controls mitosis and non-mitotic pathways through interactions with proteins that coordinate ubiquitylation. Since the discovery that the catalytic subunits of APC/C are conformationally-dynamic “cullin” and “RING” proteins, many unexpected, intricate regulatory mechanisms have emerged. Here we review structural knowledge of this regulation, focusing on: (1) coactivators, E2 ubiquitin conjugating enzymes, and inhibitors engage or influence multiple sites on APC/C including the cullin-RING catalytic core; and (2) the outcomes of these interactions rely on mobility of coactivators and cullin-RING domains, which permits distinct conformations specifying different functions. Thus, APC/C is not simply an interaction hub, but is instead a dynamic, multifunctional molecular machine whose structure is remodeled by binding partners to achieve temporal ubiquitylation regulating cell division.

Keywords: Anaphase Promoting Complex/Cyclosome, ubiquitin, E3 ligase, cryo EM, mitosis, cell division

Introduction

Progression through the cell cycle has captivated cell biologists for more than a century. The discrete steps involving biosynthesis of cellular macromolecules, chromosome and organelle duplication, and subsequent mitosis rely on biochemical reactions occurring in proper sequence. In the mid-1990s, numerous discoveries converged on a new paradigm that these events are ordered in part by the timely ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis of cell cycle proteins [1, 2]. Indeed, it is now widely appreciated that cell cycle transitions are temporally controlled when crucial regulatory enzymes are activated through ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis of their inhibitors. As examples, anaphase is initiated when the cohesin complex that binds sister chromosomes is cleaved by separase upon ubiquitin-mediated degradation of the inhibitor securin, and the G1-S transition is regulated by activation of cyclin-dependent kinases upon degradation of inhibitors p21 and p27. Another role of ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis is the termination of proteins, including cyclins, when their tasks in the cell cycle are completed. This is crucial for preventing errant recurrence of processes such as DNA replication or cytokinesis.

The two major families of E3 ubiquitin ligases that coordinate cell division are SCFs (SKP1-CUL1-Fbox proteins), which were initially recognized for regulating interphase and are now known to control many stages of the cell cycle, and Anaphase-Promoting Complex/Cyclosome (APC/C), which regulates mitosis, the exit from mitosis, and G1 (reviewed in [1–6]). APC/C also regulates progression through other sequential processes, including meiosis, differentiation, morphogenesis, and migration of various post-mitotic neuronal cell types (reviewed in [7–10]).

To understand mechanisms orchestrating temporal regulation of biological processes such as cell division, it is important to understand how E3 ligases ubiquitylate their substrates. Both SCFs and APC/C belong to the so-called “CRL” superfamily, due to their catalytic cores containing both “Cullin” and “RING ligase” subunits. Common features of CRLs include: (1) substrate “degron” sequences are recruited to variable substrate-receptor subunits that associate interchangeably with a dynamic cullin-RING catalytic core; and (2) a specific cullin-RING core recruits and activates a transient complex between Ub (Ub) and another enzyme (typically an E2), from which Ub is transferred to the remotely bound substrate (typically forming an isopeptide bond between Ub’s C-terminus and a substrate lysine) [11, 12].

While SCF E3 ligase activity was reconstituted with recombinant proteins two decades ago, the ability to probe APC/C was limited until recently because of its behemoth size. Human APC/C is a 1.2 MDa assembly comprised of 19 core subunits (one each of nine different APC subunits, and two each of five), which catalyzes ubiquitylation in collaboration with an additional coactivator protein and a Ub-linked E2 conjugating enzyme (Fig. 1A, Box 1) (reviewed in [13–15]). The variable substrate receptors are CDC20 and CDH1, which are termed “coactivators” due to their successively activating APC/C during mitosis by both recruiting substrates [16–18] and conformationally activating the catalytic core [19–21] (Fig. 1). The catalytic core consists of the cullin and RING subunits APC2 and APC11 [22–24]. The APC2-APC11 cullin-RING assembly directs Ub transfer from an assortment of E2 enzymes with different specificities [25–27]. Repeated cycles of Ub transfer lead to polyubiquitylation, wherein multiple individual Ubs become linked to the substrate and to each other to form Ub “chains”. There is enormous diversity in the architecture of potential Ub chains produced by APC/C, with the number of Ubs, and the sites of their chain linkages, thought to influence the rates of substrate degradation by the proteasome. The E2 enzyme UBE2C/UBCH10 (or in some circumstances the E2 UBE2D/UBCH5 [28]) directly modifies substrates with one or more Ubs or short Ub chains (reviewed in [13–15]), which are sufficient to target some human APC/C substrates for degradation [29]. However, many substrates are degraded after a different E2 enzyme, UBE2S in humans [30–32], extends a polyUb chain. Ub is transferred from UBE2S’s catalytic cysteine to Lys11 on an Ub that is already attached to a substrate. Often “branched” chains are formed when UBE2C first modifies a substrate with Lys48-liked Ub chains, and then UBE2S further extends these chains with additional Ubs connected via Lys11. These Lys48/Lys11 branched chains are particularly potent at directing substrates for proteasomal degradation [33].

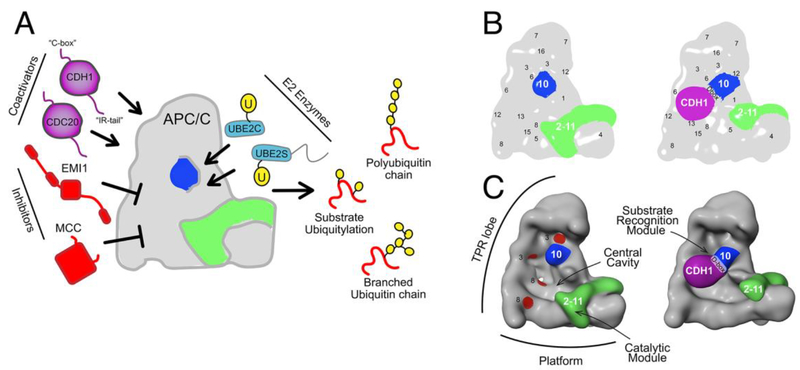

Figure 1: Overall assembly of APC/C from cartoon-like views of APC/C from cryo EM maps low-pass filtered to 30 Å resolution to provide general topological insights.

A, Schematic of APC/C binding partners and regulators. Coactivators CDC20 and CDH1 (purple) bind substrates and conformationally activate the APC2-APC11 catalytic core; inhibitors EMI1 and MCC block activity in interphase and prior to anaphase, respectively; when liberated from inhibitors, the E2 enzymes UBE2C and UBE2S link Ub to substrates or substrate-linked Ubs, respectively, to generate products with various numbers and topologies of Ub modifications.

B, 2D view of apo APC/C and APC/CCDH1 bound to a substrate peptide, showing positions of coactivator (CDH1, purple), a D-box motif sandwiched between the CDH1 β-propeller and APC10 (blue), and repositioning of APC2-APC11 (green) upon coactivator binding. Locations of other subunits are indicated by numbers, e.g. 1 refers to APC1.

C, 3D views of structures in A, highlighting the TPR lobe, Platform, Catalytic module, central cavity, and four TPR grooves (red) that can bind coactivator, APC10, and MCC IR-tails and C-boxes.

Box I: Arrangement of APC/C modules, their constituent APC subunits, and cellular APC/C inhibitors.

A, The TPR lobe is shown within EM map of apo APC/C (low-pass filtered to 30 Å resolution), with its constituent APC subunits indicated [53].

B, The Platform is shown within EM map of apo APC/C (low-pass filtered to 30 Å resolution), with its constituent APC subunits indicated [53].

C, The Catalytic Module is shown within EM map of apo APC/C (low-pass filtered to 30 Å resolution), with its constituent APC subunits indicated [53].

D, The MCC is shown with its constituent subunits indicated bound to CDC20A, within EM map of APC/CCDC20-MCC (low-pass filtered to 30 Å resolution) [48, 51].

E, The 16 kDa inhibitory domain of EMI1 is shown with its distinct inhibitory elements indicated bound to CDH1, within EM map of APC/CCDH1-EMI1 (low-pass filtered to 30 Å resolution) [47, 59].

How does APC/C recognize its substrates and catalyze their ubiquitylation? And how are the outcomes and timing of these activities regulated? These questions have driven a decade of structural studies that begin to explain how APC/C interacts with coactivators, substrates, and E2s, and how these interactions are tightly controlled by phosphorylation and inhibitory proteins to prevent premature cell division and collateral catastrophic consequences like aneuploidy (reviewed in [13, 14]). Detailed insights into the stepwise regulation of APC/C throughout the cell cycle have come in the last few years from advances in generating recombinant multiprotein complexes and cryo electron microscopy (cryo EM). Structural details provided by cryo EM reconstructions of APC/C complexes, and X-ray crystallography and NMR data on subcomplexes, as well as enzymology of ubiquitylation by wild-type and mutant versions of recombinant APC/C, have been described in recent excellent reviews [15, 34]. However, we now understand that APC/C undergoes striking conformational changes accompanying its assembly into distinct complexes, as many recent structural studies have also shown that APC/C’s ability to perform different activities depends on rotation of coactivators and on cullin and RING subunits transitioning from an intertwined inactive unit into conformationally mobile appendages [19–21, 24] that bind and are harnessed by different substrates, E2s, and inhibitors into distinct conformations specifying particular functions. Here, we summarize overall structural features of human APC/C, focusing on the emerging understanding of how its different conformations are achieved to establish regulation.

Overall APC/C organization

Early EM and other studies of APC/C from several organisms revealed that APC/C is formed from modules that together adopt an overall curved structure around a central cavity displaying flexibly tethered protein binding domains [24, 35–43]. These flexible domains both recruit and are by APC/C’s many binding partners, including substrates and the E2 enzymes that modify them (Figure 1, Box 1). This architecture both juxtaposes APC/C’s binding partners, and enables a remarkable spectrum of conformations establishing the functions of this E3 ligase.

The majority of APC/C subunits form a giant scaffold, which was originally named “the arc lamp” based on its shape when viewing APC/C from one side (Figure 1, Box 1) [24]. The scaffold consists of two modules: the “TPR lobe” resembles the curved post and lamp, and the “platform” resembles the base supporting the arched lamppost. Although this visual analogy lacked functional relevance, it did reveal the organization that enables concentrating the two functional modules – the “substrate recognition module” (either CDC20 or CDH1 coactivator and in many cases also the core subunit APC10) and a “catalytic module” (i.e., the cullin-RING catalytic core consisting of the cullin subunit APC2 and its associated RING partner APC11) – within the central cavity through their respective interactions inside the TPR lobe and platform ([24]; reviewed in [15]).

The termini of the substrate recognition and catalytic modules are anchored to opposite sides of the scaffold so that they face each other. Within the substrate recognition module, the coactivators CDC20 and CDH1 have three domains: intrinsically disordered N- and C-terminal regions containing so-called “C-boxes” and “IR-tails”, respectively, and a central β-propeller that binds to D-box, KEN-box, and ABBA-motif sequences found in substrates and APC/C regulators (reviewed in [15, 44]). The APC/C core subunit APC10 has two domains, an N-terminal jellyroll that along with a coactivator co-binds to D-box sequences, and a C-terminal IR-tail [39, 41, 45]. The IR tails from a coactivator and APC10 engage the TPR lobe through grooves at the C-termini of the two APC3 protomers, while the coactivator C-box docks in a homologous groove in one APC8 [21, 36, 46, 47]. This arrangement flexibly projects the coactivator’s β-propeller toward APC10 and the APC2-APC11 catalytic module, with its position determined by its binding partners.

Across the scaffold, the platform anchors the N-terminus of APC2’s elongated cullin structure [21]. This connects to the flexible cullin-RING catalytic core consisting of APC2’s C-terminal region and the associated APC11 [11, 12, 21]. The flexibility and positions of the catalytic core are controlled by the orientation of the platform, and by proteins interacting directly with APC2-APC11 to regulate ubiquitylation [21, 24, 47–52].

As briefly summarized below, although the scaffold is stable, its assembly from helical repeat and multidomain subunits accommodates subtle twists and turns in response to regulation, including phosphorylation and binding of partner proteins. The substrate binding and catalytic modules are positioned inside the central cavity upon interacting with substrates, E2~Ub intermediates, and inhibitors. Thus, the capacity of APC/C to conformationally respond to different regulators underlies an extraordinary array of functions.

Visualizing APC/C interactions and functions around the cell cycle

Throughout the cell cycle, APC/C undergoes a series of transformations between assemblies for which cryo EM data revealed that functions are dictated in part by conformations of the coactivator and the cullin-RING catalytic core. By the end of interphase, APC/C is hypophosphorylated, coactivator-free, and inactive, in part due to autoinhibition, whereby intramolecular interactions block access of CDC20 and restrain the cullin-RING catalytic core [21, 24, 53–55] (Figure 2A, conformation I). In prophase, phosphorylation conformationally activates APC/C binding to the coactivator CDC20, which in turn conformationally activates the catalytic core (Movie 1) [21, 24, 53–55]. APC/CCDC20 is, in principle, competent to recruit substrates for ubiquitylation [21, 24] (Figure 2A`, conformation IIA). However the timing of substrate binding is regulated by the Mitotic Checkpoint Complex (MCC), which serves as a brake during the spindle assembly checkpoint when APC/C has been activated by CDC20 but cells are not yet prepared for division [48, 51] (Figure 2B, conformation III). When all chromosomes are properly bi-oriented on the mitotic spindle, both MCC and the catalytic core are reoriented (Figure 2B, conformation IV) so MCC can itself be ubiquitylated as a prelude to liberating APC/C for substrate ubiquitylation that triggers anaphase [48, 51, 56, 57] (Figure 2B, conformation V).

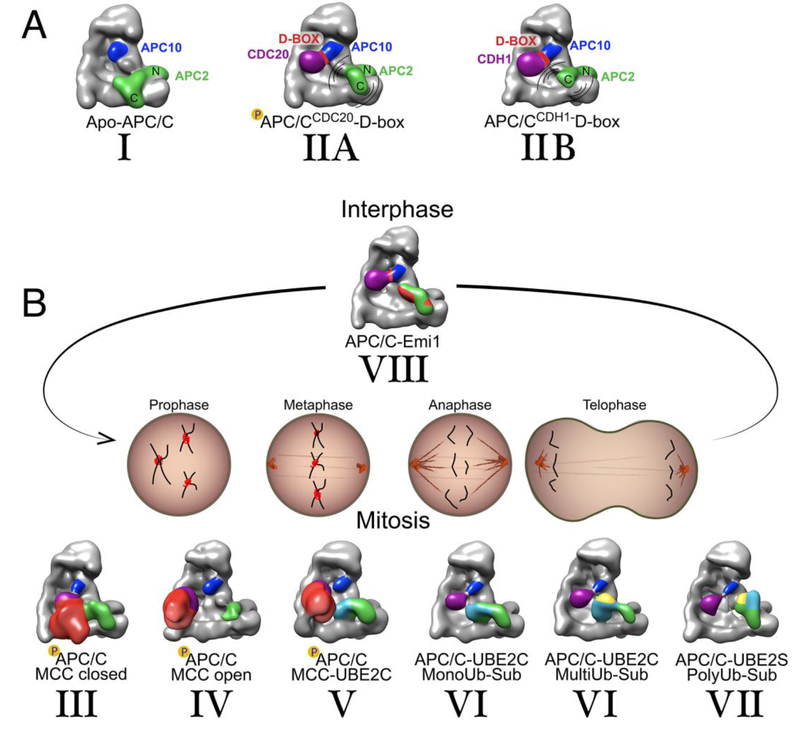

Figure 2: Coactivator and catalytic core conformations in APC/C assemblies across the cell cycle from cartoon-like views cryo EM maps low-pass filtered to 30 Å resolution to provide general topological insights.

A, Apo and coactivator bound APC/C, which are the platforms for complexes formed throughout the cell cycle. From left to right, Conformation I observed in apo APC/C, with APC2-APC11 (green) catalytic core “down” and the C-terminal catalytic domain (C) autoinhibited through interactions with the platform. Conformation II, coactivator (purple) recruits a D-box substrate along with APC10 (navy), and results in shift of the catalytic core into an active, mobile “up” position. Presumably due to mobility, the catalytic core is lower resolution in EM maps of coactivator-bound APC/C, but is relatively higher occupancy for the complex of phosphorylated APC/CCDC20 bound to a D-box peptide (IIA) than for the corresponding complex with APC/CCDH1 (IIB).

B, APC/C complexes with coactivators, inhibitors and E2s across the cell cycle. Prior to correct chromosome alignment on the mitotic spindle, MCC inhibits APC/CCDC20 in a closed configuration (Conformation III), where MCC (red) captures both CDC20A (purple) and the catalytic core (green) and fills the central cavity, and in an open conformation with MCC swung out of the central cavity and the catalytic core free to bind UBE2C (Conformation IV). When chromosomes are properly aligned on the spindle and cells are prepared for anaphase, MCC is ubiquitylated as a prelude to its dissociation from APC/CCDC20, by APC2-APC11 recruiting, activating, and positioning the E2 enzyme UBE2C (cyan) adjacent to MCC (Conformation V). Subsequently, during mitosis, coactivator bound APC/C recruits a variety of substrates -including a ubiquitylated (yellow) substrate - for UBE2C to place additional Ubs to be placed onto the substrate (Conformation VI). In Conformation VII, APC2 coordinates with UBE2S (cyan) at a site distal from the catalytic core, the RING domain of APC11 harbors an acceptor Ub for Lys-11 polyubiquitination (yellow). Conformation VIII, during interphase substrate recognition module and the catalytic core are blocked by multiple domains of EMI1 (red), which allows accumulation of cyclins to ultimately result in CDH1 phosphorylation, and resetting APC/C for interphase and another cell cycle.

In anaphase, APC/CCDC20 recruits substrates, while the APC2-APC11 cullin-RING catalytic core engages, positions, and activates transient E2~Ub intermediates from which Ub is transferred to a coactivator-bound substrate (Figure 2B, cullin-RING conformation VI) or to a substrate-linked Ub molecule during polyubiquitylation (Figure 2B, cullin-RING conformation VII) [47, 49, 50, 53]. Following anaphase, CDC20 itself undergoes APC/C-mediated ubiquitylation and subsequent degradation, but is replaced by the homologous but distinct coactivator CDH1 that recruits other substrates for ubiquitylation (Figure 2A, cullin-RING conformation IIB) [47, 49, 51]. After substrates are degraded, then EMI1 inhibits APC/CCDH1 [47, 58–60] (Figure 2B, cullin-RING conformation VIII) to enable accumulation of G1 cyclins and cdk-dependent inactivation of CDH1.

Conformational activation of APC/C enables binding to the coactivator CDC20

APC/C comes to life by binding a coactivator. This is controlled in part by phosphorylation and APC/C conformational changes that expose the binding sites for the coactivator’s C-box and IR-tail. Briefly, in interphase when mitotic kinase activity is low, CDC20 binding is blocked [61–63]. A recent cryo EM structure indicated that in the absence of phosphorylation, an APC1 loop occupies the C-box-binding site of APC8 [53] (Figure 3A). Contemporaneous biochemical studies using recombinant APC/C showed the mechanism by which mitotic phosphorylation relieves this inhibition to permit CDC20-binding: whereas unphosphorylated serines in the APC1 loop engage the CDC20-binding site by binding proximal to acidic surfaces, their phosphorylation during the cell cycle – or substitution with phosphomimicking glutamate mutations or deletion in recombinant APC/C – prevents the autoinhibitory interaction and frees the APC8 groove to bind CDC20’s C-box [53–55].

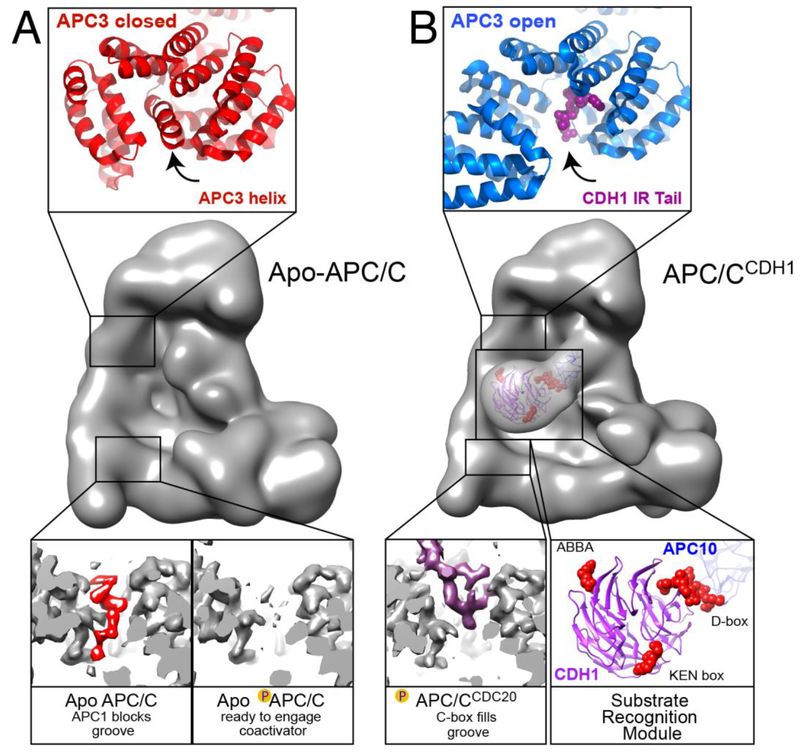

Figure 3: Conformational activation of APC/C for coactivator and associated substrate binding.

A, Conformations of TPR subunits restricting coactivator binding. Middle, high resolution EM map of apo-APC/C, low-pass filtered to 30 Å to provide a global view of the IR-tail and C-box binding sites within APC/C. Top, crystal structure showing that in the absence of a coactivator’s IR tail peptide, APC3’s C-terminal domain (red) adopts a “closed” conformation where C-terminal helices of APC3 itself (indicated with arrow) are rearranged to occupy the IR tail-binding groove. Bottom, high resolution EM density of apo-APC/C. Left, the C-terminal TPR groove of one APC8 protomer (grey EM map) houses an autoinhibitory element from APC1 (red) that blocks CDC20 recruitment to unphosphorylated APC/C. Upon phosphorylation of this APC1 loop prevents its binding to APC8, freeing the APC8 groove (right), thereby allowing binding of CDC20 and cell cycle progression.

B, Coactivator-bound conformations of TPR subunits and substrate-binding to coactivator. Middle, EM map of APC/CCDH1-substrate peptide complex, low-pass filtered to 30 Å to provide a global view of coactivator interactions, highlighting the location of the substrate-binding CDH1 α-propeller, and the IR-tail and C-box binding sites within APC/C. Top, “open”, active conformation of APC3’s C-terminal domain (blue) bound to the IR-tail from the C-terminus of CDH1 (magenta, indicated with arrow in same relative location as in panel A), visualized within high resolution EM density of an APC/CCDH1-EMI1 complex. Bottom, left, C-box binding as visualized in high-resolution EM map. When APC/C is phosphorylated, the APC8 pocket (grey EM density) can bind an N-terminal C-box, as shown from CDC20 (purple EM density). Right, model of substrate recognition module (APC10, navy and CDH1 β-propeller domain, purple) bound to peptides with ABBA, D-box, and KEN-box motifs (red) based on superimposing structures harboring these motifs on EM data showing the relative positions of substrate-bound CDH1 and APC10.

Structural studies of the other coactivator-binding site – the APC3 groove recruiting CDC20’s or CDH1’s IR-tail – also raise the possibility of conformational control (Figure 3A). Two conformations have been characterized, an “open” form with the C-terminal TPR superhelical groove exposed to engage an IR-tail (Figure 3A), and a “closed” form in which APC3’s own C-terminal helices are dramatically rearranged to pack in the groove (Figure 3B) [21, 47, 64]. Both conformations were observed in apo-APC/C [53]. Although it remains unknown if the APC3 conformations are simply in equilibrium or if APC3 binding to a coactivator’s IR-tail is regulated, it is conceivable that docking of a coactivator’s C-box in the APC8 groove could potentially trigger conformational changes throughout the TPR lobe that influence opening of the APC3 groove.

Coactivator binding sets APC/C catalytic core in motion

A coactivator not only recruits substrates to APC/C [18] (Figure 3B), but also stimulates repositioning of the catalytic core [19, 24]. High resolution cryo EM maps of apo forms of APC/C without a coactivator show the catalytic core and platform rigidified from the APC2-APC11 α/β-domain and RING domain straddling the APC4 helical domain [53] (Figure 1C, 2A, 4A, Box 1, Movie 1). This “down” conformation blocks the canonical E2-binding site on APC11’s RING domain, and renders the central cavity wide open presumably for access to activating kinases and coactivators.

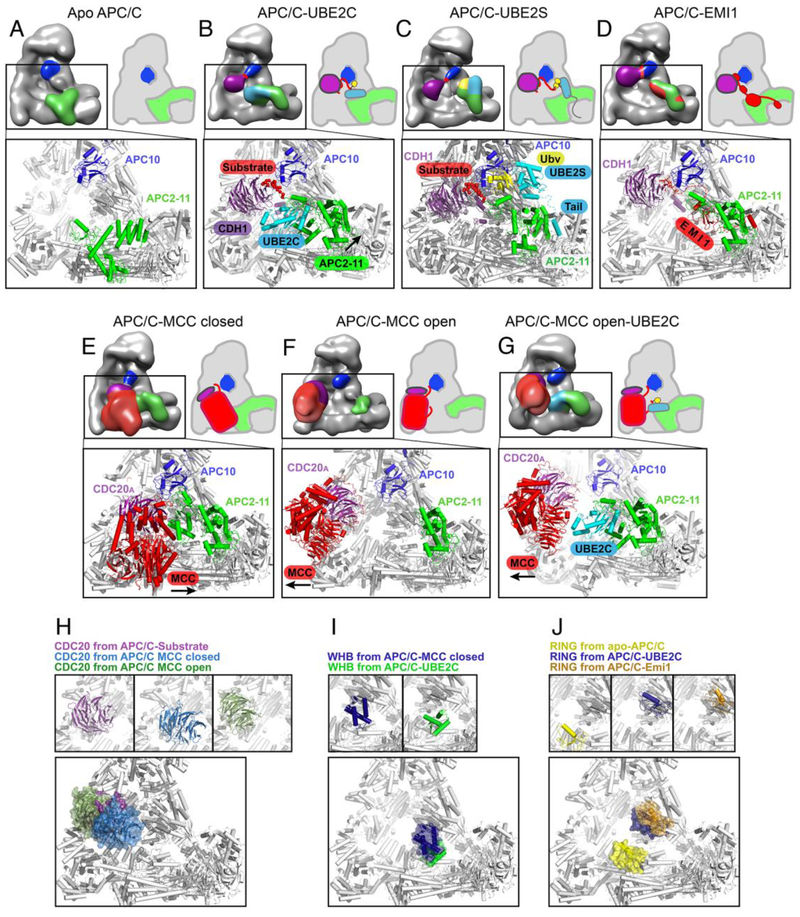

Figure 4: Molecular insights into conformational changes in the APC/C substrate recognition module and catalytic core acros the cell cycle.

Cartoon-like representations of APC/C are complemented with similarly colored high-resolution models.

A, Without a coactivator bound in apo-APC/C, the catalytic core (green) is in an inactive “down” conformation and APC10 (navy) does not recruit substrates.

B, In structures representing substrate ubiquitylation, with APC/C-coactivator (here CDH1, purple) complexes bound to substrate (red) and UBE2C (cyan), the catalytic conformation is established by cullin-RING domains (green, specifically the RING domain of APC11 and the extreme C-terminal WHB domain of APC2) grasping discrete surfaces from the UBE2C~Ub (yellow in cartoon) intermediate. This places the active site proximal to substrate lysines.

C, In a model for polyubiquitylation, from APC/C-coactivator (here CDH1, purple) complexes with a substrate model (substrate peptide in red, a Ub variant mimicking its linked Ub in yellow) and UBE2S (cyan), the acceptor Ub (yellow) whose Lys11 will become linked to the C-terminus of another Ub is recruited by an unprecedented surface from the APC11 RING domain in the catalytic core (green) and positioned adjacent to the active site in UBE2S. In a unique E2–E3 interaction, the C-terminal helices of UBE2S’s catalytic domain are recruited via helices in APC2’s helical bundle and α/β-domain, and a C-terminal tail unique to UBE2S among the E2s is recruited to a pocket between APC2 and APC4. The location of UBE2S at the periphery of the APC/C central cavity may accommodate extension of long polyUb chains.

D, High resolution cryo EM data showed multiple elements from EMI1 (red) block substrate binding and ubiquitylation by APC/CCDH1 during interphase. EMI1 occupies the substrate recognition module, and the catalytic module by wrapping around the APC11 RING domain, and inserting its own tail sequence in the same groove that would otherwise bind the tail from UBE2S.

E, In near atomic resolution cryo EM data for a “closed” configuration, association of the MCC (red) is seen inhibiting substrate binding and ubiquitylation by UBE2C by reorienting and enwrapping the APC/C-bound CDC20 molecule (CDC20A, purple), capturing the UBE2C-binding APC2 WHB domain (green), and filling the central cavity.

F, In “open” configurations represented by EM data that were lower resolution presumably due to mobility, the CDC20A (purple)-MCC (red) subcomplex is rotated out of the APC/C central cavity, and the catalytic module is liberated and available to bind E2s.

G, In a structural model of MCC ubiquitylation based on low resolution EM data and high resolution structures of the individual components, the CDC20A (purple)-MCC (red) subcomplex is in an “open” configuration, while the APC11 RING domain and APC2 WHB domain grasp UBE2C as in panel B, except to place the active site adjacent to CDC20-bound MCC rather than to a coactivator-bound substrate.

H, Close-up views of different functional positions of the CDC20 substrate receptor, from complex with substrate as represented by a D-box peptide (purple), with MCC in the closed configuration (slate), and with MCC in the open configuration (olive), individually on top and superimposed below.

I, Close-ups of different functional positions of APC2 cullin WHB domain, as bound to MCC in the closed configuration (navy) and to UBE2C (green), individually on top and superimposed below.

J, Close-ups of different functional positions of APC11 RING domain, as autoinhibited in apo APC/C (yellow), when poised to ubiquitylate substrates by activating the UBE2C~Ub intermediate (blue), and inhibited by EMI1 (orange) individually on top and superimposed below.

Coactivator binding induces substantial APC/C conformational changes that globally shift the platform and catalytic core into proximity of the substrate-binding module and increase the mobility of domains contributing to catalysis [21, 24] (Figure 2A, 4). Most strikingly, repositioning of APC4 eliminates contacts with the catalytic core observed in apo-APC/C [47]. The liberated C-terminal domain of APC2 and the associated APC11 RING domain become mobile in an activated “up” location as indicated by their relatively low resolution in EM maps of APC/C-coactivator-substrate complexes (Figure 2A) [21, 24, 39, 41, 53]. Indeed, much regulation of APC/CCDC20 and APC/CCDH1 depends on various partner proteins harnessing different binding sites on the flexibly tethered coactivator and cullin and RING portions of the catalytic core.

Harnessing the mobile APC/C for initial Ub transfer directly onto substrates

For ubiquitiylation to occur, substrates and Ub carrying enzymes must be juxtaposed. Furthermore, RING E3s typically activate the ligation reaction, i.e. ubiquitin transfer, by the RING domain binding both the E2 catalytic domain and its thioester-bonded Ub. This stabilizes weak interactions between the E2 and Ub in a “closed conformation” [65–67] that strains and stimulates reactivity of the thioester bond between them [68]. Positioning substrate lysines proximal to an activated E2~Ub intermediate is therefore crucial for ubiquitylation.

The best-characterized APC/C substrates are recruited via various linear motifs (e.g. D-boxes, KEN-boxes, and ABBA motifs) that serve as degrons, binding to distinct regions of a coactivator’s β- propeller domain (Figures 1, 3B) (reviewed in [44]). In addition, D-boxes co-bind the APC/C core subunit APC10, thereby fastening the coactivator propeller adjacent to APC10 (Figure 2A, 3B) [39, 41, 45, 47]. The positions of potential target lysines within substrates are thus determined by their locations relative to degrons bound to an APC/C-coactivator complex, and the location of the coactivator propeller determined by the presence or absence of a D-box.

The E2 UBE2C (aka UBCH10) is recruited to APC/C by a specialized mechanism that places the active site proximal to substrates (Figure 4B). One side of the UBE2C~Ub intermediate engages APC11’s RING domain through canonical RING-E2~b interactions [47, 49]. However, as in other cullin-RING ligases [12], APC11’s RING domain is loosely tethered to the cullin-binding region by a flexible linker that rotates (Figure 4). How then, does the RING-bound UBE2C~Ub intermediate achieve a position with the active site facing substrates? Unexpectedly, the flexibly tethered cullin element at the C-terminus of APC2 – the “WHB” subdomain – binds UBE2C’s so-called “E2 backside” distal from the active site (Figure 2B) [49]. Thus, the two flexibly tethered domains of APC11 and APC2 together grasp opposite sides of UBE2C, acting like a clamp to direct the catalytic center toward substrates [49]. This structural arrangement provides a potential rationale for why many APC/C substrates are ubiquitylated in intrinsically disordered regions: flexible polypeptides bound to a coactivator can access the relatively proximal but immobilized UBE2C active site [47, 49, 50, 69]. Indeed, the disordered N-terminal domain of Cyclin B can receive enough individual Ubs from UBE2C for proteasomal targeting even without generation of polyubiquitin chains [29]. The confined space between UBE2C’s active site and a coactivator-bound degron may also explain why UBE2C preferentially modifies substrates with individual Ubs and short chains rather than long polyubiquitin chains [70].

Ubiquitin capture by the mobile APC11 RING domain contributes to processive substrate ubiquitylation

Although the rules of Ub-mediated proteolysis are only beginning to emerge, the rate and order in which different APC/C substrates are degraded during the cell cycle correlates with processivity of their ubiquitylation. Highly processive substrates receive enough Ubs in a single binding event to enable proteasome binding, and are apparently degraded earlier during the cell cycle than non-processive substrates that must cycle on and off APC/C numerous times to receive enough Ubs for proteasomal targeting [71]. Degradation of less processive substrates can be further slowed by competition with other substrates preventing their re-binding to APC/C, and deubiquitylation removing the few initially-linked Ubs [72].

Processivity is determined in part by the rate of a substrate’s dissociation from APC/C, which depends on the affinities and arrangement of degron sequences. In addition, a substrate evolves during ubiquitylation, which affects processivity as revealed by recent single molecule experiments. In a process called “Processive Affinity Amplification”, ubiquitylation increases a substrate’s duration on APC/C and propensity for further ubiquitylation [73]. Processive Affinity Amplification is determined in part by mobile elements within the APC/C catalytic core, whereby a substrate-linked Ub binds an unprecedented ubiquitin-binding site that is distinct from the UBE2C~Ub binding site on APC11’s RING domain [74]. The RING domain simultaneously captures a Ub linked to a substrate and places UBE2C to ubiquitylate another site on a substrate [50]. Accordingly, mutationally eliminating the secondary RING-ubiquitin interaction decreased processivity in vitro, reducing the number of Ubs received by a given substrate molecule, while increasing the number of substrates receiving at least one Ub [50], although other Ub binding sites within APC/C that contribute to Processive Affinity Amplification or other functions remain to be described.

APC/C uses a dynamic cullin-RING mechanism to elongate polyubiquitin chains

Human APC/C generates Lys11-linked polyubiquitin chains through an entirely different mechanism, via the distinctive E2 enzyme, UBE2S [30–32]. Although APC2 and APC11 were shown to be necessary and sufficient to activate UBE2S, the mechanism was unclear because UBE2S lacks the hallmark E2 residues known to engage RING domains [31]. Indeed, mutation of the APC11 residues binding UBE2C did not impair UBE2S-mediated polyubiquitination [74]. Furthermore, unlike the reaction with UBE2C that is stimulated by coactivator, the intrinsic Ub chain building activity of UBE2S (i.e. transfer of a “donor” Ub onto a free “acceptor” ubiquitin) is activated by recombinant APC/C that can be prepared independently of coactivator [21, 74]. Instead, a primary function of APC/C is recruiting and positioning the acceptor Ub for its Lys11 to accept another Ub from UBE2S [74, 75].

A structural model for the unprecedented interactions between UBE2S, its target (i.e., a Ub that has been linked already to an APC/C substrate), and APC/C was generated by hybrid structural studies merging information from NMR, crosslinking, and mutational data with a low-resolution cryo EM map of APC/CCDH1 complexed with a proxy for the Ub chain elongation intermediate (Figure 4C) [50]. Although the details of these interactions await high resolution studies, it is clear that APC/C engages UBE2S in a bipartite manner, but this differs completely from interactions with UBE2C. UBE2S is anchored to APC/C by a flexibly tethered extension C-terminal of UBE2S’s catalytic domain [30–32]. Here, UBE2S’s extreme C-terminal residues pack into a pocket between the APC2 N-terminal domain and APC4 β-propeller [47, 50]. Additionally, the UBE2S catalytic domain interacts with an APC2 surface that differs completely from previously described E3–E2 interactions [50, 74, 75]. The RING is also crucial, as it posesses a distinctive binding site recruiting Ub for modification by UBE2S [74]. Apparently, the catalytic geometry whereby APC11’s RING domain can present Ub for modification by UBE2S is attainable even with APC2-APC11 in the “down position”, which accounts for APC/C activating UBE2S-dependent generation of unanchored polyubiquitin chains even in the absence of a coactivator and a substrate [21, 52, 74, 75]. Overall, the data suggest that UBE2S can be activated by various positions of the APC2-APC11 cullin-RING catalytic core, although at this point, it remains unknown whether the position of the APC11 RING domain required to engage UBE2C allows simultaneous positioning of Ub for modification by UBE2S, or how UBE2C and UBE2S might co-function with APC/C to generate branched Ub chains.

Inhibiting APC/C during interphase and prior to anaphase

Because ubiquitylation by APC/C triggers cell division, it is essential that APC/C is restrained until cells are prepared for its substrates to be degraded. In addition to regulation by phosphorylation, an additional layer of control comes from cellular inhibitors also restricting ubiquitylation until needed. This is best understood for APC/CCDH1 inhibition by Early Mitotic Inhibitor 1 (EMI1) in interphase [58], and APC/CCDC20 inhibition by the Mitotic Checkpoint Complex (MCC) prior to anaphase [76–80]. EMI1 and MCC may also play roles in localizing APC/C to specific subcellular structures or substrates [14], although the structural basis for this regulation remains unknown.

Both EMI1 and MCC hijack the mobile substrate recognition and catalytic modules by binding multiple sites on APC/CCDH1 and APC/CCDC20, respectively (Box 1). However, they achieve these functions through completely different routes. In addition, MCC does not block UBE2S-dependent polyubiquitination and even binds APC/C in distinct configurations that differentially modulate ubiquitylation, while EMI1 apparently inhibits all APC/C ubiquitylation.

EMI1 regulates the coupling of mitosis and DNA replication [81]. Briefly, after cells divide, APC/CCDH1 activity must be restrained. Although this is ultimately achieved by CDH1 phosphorylation, the required cdk activity is too low in G1 due to APC/CCDH1-dependent degradation of cyclins. Thus, accumulation of cyclins during G1 depends on EMI1 inhibiting APC/CCDH1. The best characterized portion of the 50 kDa EMI1 protein is its 16 kDa C-terminal domain, which consists of four inhibitory elements: a D-box, linker, zinc binding region (ZBR), and C-terminal tail [47, 58–60]. Each individual EMI1 element only weakly interacts with APC/CCDH1, but together they synergistically bind numerous APC/CCDH1 domains to avidly inhibit (Figure 4D, Box 1) [47, 58–60]. The EMI1 D-box co-binds CDH1 and APC10 to block substrate access [47, 58–60]. The linker and ZBR together act like a wedge to simultaneously capture the UBE2C-binding surface of the APC11 RING domain and elements of APC2 and APC1 [47, 59]. This has several effects including seizing the RING domain away from a catalytic conformation, while also walling off a portion of the central cavity. Finally, EMI1’s C-terminal tail shares sequence homology with UBE2S’s C-terminal tail, docks in the same groove between APC4 and APC2, and prevents UBE2S binding [47, 59, 60]. Although EMI1 locks the APC/C structure in a relatively rigid conformation, the intrinsic flexibility of the APC11 RING domain would enable its initial capture by EMI1.

It is also critical that APC/CCDC20 is inhibited by MCC during the Spindle Assembly Checkpoint, prior to correct chromosome alignment on the mitotic spindle (Box 1, reviewed in [13, 34]). As proposed in [13] and demonstrated in [82], human MCC is a heterotatrameric complex consisting of its own molecule of CDC20, along with three other proteins associated with regulating the Spindle Assembly Checkpoint (MAD2, BUBR1, and BUB3) (reviewed in [34]). The APC-bound CDC20 is denoted as CDC20A (i.e., in APC/CCDC20), and that in MCC as CDC20M. To date, BUB3 has not been visualized in cryo EM maps despite its presence in the complexes, leaving open the structure and role(s) of the BUB3 subunit. Nonetheless, the core of MCC - the CDC20M-MAD2-BUBR1 subcomplex, which corresponds to the entire MCC in some organisms, and is sufficient to recapitulate many biochemical properties of full human MCC in vitro (reviewed in [34]) - has been visualized bound to APC/CCDC20 by cryo EM (Figure 2B, 4E–G) [48, 51].

APC/CCDC20-MCC is conformationally dynamic, with different architectures specifying distinct activities. The different configurations are achieved in part by tilting and rotation of the CDC20A propeller domain, and by variation in conformation of the APC2-APC11 cullin-RING subcomplex.

One architecture, termed “closed”, has been visualized at near atomic resolution in cryo EM maps of recombinant complexes that superimpose with earlier lower resolution EM data obtained for APC/CCDC20-MCC purified from HeLa cells arrested during the mitotic checkpoint (Figure 4E) [38, 48, 51]. Here, MCC essentially fills the entire central cavity, and blocks substrate-binding sites by enwrapping CDC20A through multiple elements, including a D-box, an ABBA-motif, a KEN-box [48, 51, 82, 83]. In addition, residues proximal to the CDC20M propeller interact with CDC20A adjacent to its D-box binding site.

The closed configuration is secured by interactions involving multiple distal MCC elements [48, 51]. First, the IR-tail from MCC’s CDC20M docks in the vacant TPR groove from the second APC8 molecule in APC/C. Second, the BUBR1 subunit of MCC hijacks the UBE2C-binding surface on the WHB subdomain of APC2. As with the APC/C conformations that mediate ubiquitylation, this inhibited architecture depends on mobility of the WHB domain, which enable its capture in different orientations by MCC and UBE2C. Because there is no sequence or structural homology between BUBR1 and UBE2C, this interaction was unexpected and demonstrated multifunctionality of a cullin’s WHB domain.

Interestingly, unlike EMI1, MCC does not hijack any known elements for UBE2S-dependent Ub chain elongation, explaining how APC/CCDC20-MCC complexes remain competent for UBE2S-dependent free Ub chain elongation [48, 51, 75]. Nonetheless, it remains unknown whether this UBE2C activity is irrelevant due to the absence of UBE2C-dependent substrate ubiquitylation, or whether there is functional importance for MCC-bound APC/CCDC20 in extending polyubiquitin chains.

Freeing APC/C from inhibitors for ubiquitin-dependent cell division

In order for cell division to proceed, APC/C must be liberated from inhibitors to catalyze ubiquitin-dependent turnover of its substrates. EMI1 is removed and degraded by several phosphorylation and ubiquitylation-dependent mechanisms [84, 85] that may vary in detail among organisms [86] and that remain mechanistically perplexing [87] in part due to lack of structural details. However, structural mechanisms contributing to liberation of APC/CCDC20 from MCC have recently been elucidated. When the spindle assembly checkpoint is satisfied, chromosomes are correctly aligned on the mitotic spindle, and cells are prepared for anaphase, MCC dissociates from APC/CCDC20 in a manner that involves UBE2C-dependent ubiquitylation of the CDC20M subunit within MCC [56, 57]. Structural reconstitution of this reaction revealed massive conformational changes [48, 51]. In addition to the closed conformation of APC/CCDC20-MCC described above that excludes UBE2C, cryo EM structures also revealed more “open” configurations (Figure 4F) [48, 51]. Here, MCC still blocks canonical substrate binding sites on CDC20A, but the CDC20A-MCC portion of the complex is rotated out of the APC/C central cavity. Concomitantly, the APC2-APC11 cullin-RING catalytic core is free of MCC, conformationally activated, and available (Figure 2B, 4F). Indeed, additional low resolution EM structures showed that within an open configuration of APC/CCDC20-MCC, UBE2C is placed by both the APC2 WHB domain and APC11 RING domain adjacent to the MCC target lysines (Figure 2B, 4G) [48, 51, 88], which would drive Ub-dependent regulation of APC/CCDC20-MCC dissociation.

The question arises as to how the massive conformational changes determining whether APC/CCDC20-MCC is inhibited or able to catalyze MCC ubiquitylation are naturally controlled? This transition likely involves APC/C regions near the subunit APC15, because reducing cellular APC15 levels stabilizes MCC on APC/C [88–90]. Indeed, recombinant APC/CCDC20-MCC complexes lacking APC15 preferentially adopt the closed conformation which inhibits UBE2C-dependent ubiquitylation [48, 51], although APC15 is not required for APC/CCDC20-MCC to swing away from the APC2-APC11 catalytic core [48, 51], nor is there evidence that APC15 ever cycles on and off APC/C. It is possible that all APC/CCDC20-MCC complexes continually cycle between the closed and open states. However, differences between the structural studies might indicate a role for phosphoregulation: different ratios of open versus closed configurations of recombinant APC/CCDC20-MCC were observed [48, 51] depending on whether the APC/CCDC20 accumulated phosphorylation during expression in insect cells [53] or whether every potential phosphorylation was mimicked by glutamate replacements for all 100 possible mitotic phosphorylation sites [54]. The two preparations likely differed in terms of where negative charges were placed, raising the possibility that certain negatively charged phosphorylation sites may modulate the conformation of APC/CCDC20-MCC in vivo to regulate termination of the spindle assembly checkpoint.

Concluding remarks

Recent studies have provided unprecedented details of APC/C structure and enzymology, which explain how the activity of this massive E3 ligase is controlled, and how ubiquitylation is achieved to temporally regulate cell division. Although one pervasive question has been why the APC/C has such an enormous molecular mass, it seems that the large size enables both nuanced and extreme conformational changes - and their coupling to phosphorylation and the binding of many partner proteins. Step-by-step regulation is achieved through each complex allowing precisely the needed APC/C functions while excluding others (Figure 4). For example, apo, unphosphorylated APC/C excludes coactivator and UBE2C, while phosphorylated APC/C allows CDC20 binding. APC/CCDC20’s many activities are further tuned, including MCC in a closed and inactive state, an open configuration that excludes APC/C substrates but allows UBE2C-catalyzed ubiquitylation of MCC, and substrate bound in a manner that excludes MCC and allows UBE2C for its direct modification. Ubiquitylated substrates and UBE2S capture yet alternative locations on the cullin-RING core for polyubiquitylation to drive progression through mitosis, while EMI1 subsequently prevents substrate and E2 binding to allow cyclin accumulation and another cell cycle.

Despite the wealth of structural data, many open questions remain (see Outstanding Questions), especially relating to how these discrete APC/C complexes transition from one state – or binding partner and activity – to another. It seems likely that the multisite, avid nature of APC/C’s interactions could contribute to this regulation, as all elements within most APC/C partners are required for their high affinity binding. It seems likely that the dismantling of one interaction, for example through a post-translational modification or the binding of another protein, could precipitate disassembly through a domino-like effect. Future studies will also be required to visualize emerging APC/C regulation, including by phosphorylation, SUMOylation, association with enigmatic binding partners [91–94], and localization of APC/C to its different regulators and substrates within cells.

In addition to APC/C, humans are estimated to express more than 500 different E3 ligases, roughly half of which are cullin-RING ligases (CRLs) whose catalytic core becomes mobile upon activation [12]. However, because few activity states have been structurally visualized for most E3 ligases, the studies on APC/C described herein provide paradigmatic molecular principles determining distinct E3 ligase activities across a biological pathway. Although the structural details will differ between ligases, it seems that much like APC/C, E3s will generally be found to be restrained in inactive conformations until needed, conformationally flexible when activated, and harnessed into distinct conformations for different functions.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

The Anaphase Promoting Complex/Cyclosome (APC/C) is a massive, 1.2 MDa multiprotein E3 ligase comprised of scaffolding and substrate-binding modules, and a cullin-RING catalytic core.

Recent technical advances have enabled reconstituting, assaying and visualizing molecular mechanisms of recombinant APC/C E3 by cryo EM in numerous states: before and after phosphorylation and in complexes with substrate-bound coactivators, E2s, and inhibitors.

The data collectively show remarkable conformational changes correlating with distinct mechanisms of activation, ubiquitylation, and inhibition.

In particular, the mobility of the cullin and RING catalytic domains, taken together with multisite binding by APC/C partners, enables their differential capture and positioning to temporally control ubiquitylation-dependent steps in cell division.

Box I: APC/C Modules and Inhibitors

The TPR lobe:

The TPR lobe is so-named because it primarily consists of homodimers of TPR proteins, APC8, APC6, APC3, and in some organisms (including humans) APC7, stacking on top of each other, from the platform to the tip of the TPR lobe to form the arched lamppost-like structure (Figure IA) [42, 95]. APC8, APC6, APC3 and APC7 each consist of 13–14 TPRs that form an extended superhelical structure with roughly two superhelical turns ([3, 5, 6, 96]; reviewed in [15]). Their N-terminal domains each adopt nearly one superhelix that homodimerizes by wrapping around its partner protomer in a head-to-tail arrangement, while their C-terminal domains also adopt a superhelix that radiates outward with concave and convex curvatures in opposite orientations [97]. Despite potential for each TPR subunit to adopt a symmetric homodimer on its own, their asymmetric arrangement in APC/C is established by their stacking with convex ridges from the C-terminal domain packing in a concave surface from the adjacent subunit in the stack (Figure IA). The stack of homodimeric TPR subunits is further stabilized by three small but elongated non-TPR subunits. APC13 and APC16 extend through a central groove, spanning the APC8-APC6 and APC3-APC7 subunit interfaces, respectively, while the C-terminal domains from both molecules of APC6 are stabilized by wrapping around APC12 (aka CDC26) (Figure IA) [21, 98].

The TPR lobe displays four crucial binding sites, in grooves near the C-terminus of each protomer of APC3 and APC8 that can bind hydrophobic-basic or basic-hydrophobic dipeptide sequences known as “IR-tails” or “C-boxes” [36]. The grooves in the two protomers of APC3 bind C-terminal Ile-Arg sequences (i.e. IR-tails) from the APC/C core subunit, APC10, and from coactivators. Coactivators also display an N-terminal C-box that binds the groove in one protomer of APC8. CDC20 binding to APC8 is determined by APC/C phosphorylation as described in the main text, while binding of the other coactivator, CDH1, is prevented until its own phosphorylation is reversed [62, 99–101]. The other APC8 groove can be engaged by other APC/C-interacting proteins and complexes, for example the Mitotic Checkpoint Complex during the Spindle Assembly Checkpoint [48, 51].

The Platform:

The platform, which consists of APC1, APC4, APC5, and APC15, makes numerous connections with the TPR lobe (Figure IB) [24, 35, 42]. APC5 contains two domains, an N-terminal helical domain and a TPR domain that wraps around the N-terminal half of the small, extended APC15 [21, 47]. The APC5-APC15 subcomplex primarily contacts the APC8 homodimer, with APC15 and APC5 helical domain contacting one protomer of APC8, and APC5’s TPR domain binding the other [21, 47]. This latter protomer of APC8 also binds a coactivator C-box, and the massive multidomain protein APC1, which in turn connects additional portions of the APC/C TPR lobe to the substrate recognition and catalytic modules [21, 47]. APC4 has two domains, a β-propeller and an intervening, elongated helical bundle [21, 47].

The Catalytic Module:

The catalytic core of APC/C is comprised of the APC2-APC11 subcomplex, which is related to canonical cullin-RING E3 ligases [11, 22, 23, 102]. Like other cullins, APC2 is an elongated multidomain protein, with an N-terminal helical domain, and a C-terminal cullin-RING assembly composed of multiple subdomains: a helical bundle, an α/β-subdomain that contains an intermolecular β-sheet incorporating the N-terminal strand from APC11, the flexibly tethered C-terminal “WHB” subdomain from APC2, and the likewise flexibly tethered C-terminal RING domain from APC11 (Figure IC). The elongated APC2 is co-recruited by a helical domain of APC1 and the APC4 β-propeller [21, 47]. The position of the catalytic module is modulated by the position of the platform [24], particularly APC4, which acts like a lever [21]. APC/C is inactive with the E2 UBE2C when the catalytic core is “down” and autoinhibited in the absence of coactivator, but is stimulated when the catalytic core “up” and conformationally dynamic in coactivator-bound APC/C complexes. Flexible regions of the APC2-APC11 catalytic core interact differentially with the two E2s, UBE2C and UBE2S, and also with the inhibitors EMI1 and MCC, to achieve discrete conformations mediating regulation.

MCC:

The Spindle Assembly Checkpoint (SAC) is a signaling pathway safeguarding proper chromosome segregation, which coordinates correct and complete chromosome bi-orientation on the mitotic spindle with cell division (reviewed in [13, 34]). The SAC senses unattached kinetochores, which through intricate mechanisms results in assembly of a multiprotein complex, called “Mitotic Checkpoint Complex” (MCC), which is composed of three core proteins (CDC20M, BUBR1, and MAD2) and another in some organisms including humans (BUB3) that each function in multiple diverse complexes regulating several steps involved in chromosome segregation (reviewed in [13, 34]). Once chromosomes are properly aligned on the spindle, the SAC pathway, and therefore the production of MCC, is inactivated (reviewed in [13, 34]). A crystal structure showed MCC from S. pombe [103], while recently reported cryo EM maps showed the corresponding regions of human MCC bound to the CDC20 molecule (CDC20A) associated with APC/C (Figure ID) [48, 51].

EMI1:

EMI1 is a 50 kDa multidomain protein. The N-terminal region mediates regulatory interactions, and includes a degron sequence that when phosphorylated targets EMI1 degradation by SCFβTRCP [84, 85, 104]. EMI displays its own central F-box, but to date its roles remain elusive. The APC/C inhibitory elements - a D-box, linker, zinc binding region (ZBR), and C-terminal tail - are concentrated in EMI1’s 16 kDa C-terminal domain (Figure IE). Using these distinct elements, EMI1 simultaneously binds CDH1, APC10, the APC11 RING domain, the APC2 WHB subdomain, and the groove between APC2 and APC4 to inhibit all known catalytic activities [47, 58–60].

Although how EMI1 dissociates from APC/CCDH1 during the cell cycle remains poorly understood, in vitro the disruption of even a single element greatly impairs the interaction [58–60]. This raises the possibility that perturbation of a single EMI1 inhibitory element may be sufficient to regulate dissociation. Thus, it is noteworthy that in some organisms, mitotic phosphorylation sites [86] mapping to the D-box and linker/ZBR region are poised to disrupt interactions with APC/CCDH1’s substrate-binding module and RING domain. Also, a recent study reported that high concentrations switch EMI1 from an inhibitor to a substrate, although the mechanistic basis remains perplexing [87].

Outstanding Questions.

How does APC/C coordinate the activity of the two E2s UBE2C (aka UBCH10) and UBE2S? Do they function simultaneously, or, if substrate ubiquitylation by UBE2C and chain elongation are strictly separate reactions, what determines which reaction dominates and what regulates the transition between them? What are the determinants of branched ubiquitin chain formation?

How are inhibitors EMI1 and MCC removed from APC/C? Is there regulation of the structural transition between APC/CCDC20-MCC adopting the closed, inhibited configuration and the open conformation enabling MCC ubiquitylation as a prelude for its removal? Or are the APC/CCDC20-MCC conformations in equilibrium, with continuous cycles of MCC binding to APC/CCDC20, MCC ubiquitylation, and subsequent dissociation from APC/C and disassembly, determined exclusively by the levels of MCC produced during the Spindle Assembly Checkpoint?

Although rules for how APC/C is regulated in time is emerging, less is known about how APC/C is regulated in space. How is APC/C localized to specific substrates in different subcellular locations?

Acknowledgements

We thank our wonderful colleagues who have contributed to our understanding of the cell cycle and the structure and function of APC/C, and apologize to those whose work we were unable to cite herein. We thank J. Rajan Prabu for making the movies showing APC/C conformational changes. Our work on APC/C is funded by NIH R35GM128855 and UCRF (NGB),Boehringer Ingelheim, Austrian Science Fund, Austrian Research Promotion Agency, and the European Community (JMP); the Max Planck Society (HS and BAS); and ALSAC, NIH R37GM065930 and P30CA021765 (BAS).

Glossary

- APC subunit

Human APC/C consists of 19 polypeptides and 13 subunits, one each of APC1, APC2, APC4, APC5, APC10, APC11, APC13, APC15, and APC16, and two each of APC3, APC6, APC7, APC8, and APC12. There are variations in subunits across eukaryotes, for example S. cerevisiae lacks subunits corresponding to APC7 and APC16, and has an additional subunit (APC9) not yet discovered in human APC/C.

- Cullin-RING

Catalytic core of many E3 ligases, formed by a complex between a cullin protein and a specific RING partner. The cullin fold consists of two domains, an N-terminal domain composed of helical “cullin repeats”, and a C-terminal domain composed of several subdomains: a helical bundle that connects to the N-terminal domain, an α/β domain that incorporates a β-strand from the RING protein partner to form the cullin-RING complex, and a C-terminal WHB domain. The C-terminal RING domain of the RING protein typically extends from the cullin-RING α/β domain to play roles in catalyzing ubiquitylation.

- Degron

Consensus motif sequence within proteins subject to Ub-mediated degradation that mediates binding to and ubiquitylation by an E3 ligase.

- E2 catalytic domain

Roughly 17 kDa domain homologous amongst E2 enzymes that is typically responsible for catalysis. Some E2 enzymes consist solely of a catalytic domain while others like UBE2C and UBE2S that collaborate with APC/C have additional sequences at the N- and C-terminus of their core domains, respectively

- E2 Ub conjugating enzyme

Central enzyme in E1–E2–E3 Ub conjugation cascades, receives Ub from E1 to form a thioester-linked E2~Ub intermediate (“~” refers to covalent, thioester bond)

- E3 Ub ligase

Terminal factor in E1–E2–E3 Ub conjugation cascades that recruits specific substrates and collaborates with an E2 enzyme to promote Ub transfer to substrates

- RING domains

Stands for Really Interesting New Gene domains, which bind at least two Zn2+ ions through a conserved constellation of Cys and His residues, and along with SP-RING domains that bind one Zn2+ ion and U-box domains that do not bind zinc, adopt a conserved fold found in many E3 ligases. RING and RING-like domains are thought to typically bind an E2~Ub (or E2~Ub-like protein) intermediate and activate Ub transfer from the E2 active site

- TPR

A structural motif based on particular “tetratricopeptide” or ≈34-residue repeats that form antiparallel helices packing in tandem to generate superhelical turns

- Ub chain

Repeated Ub transfers can lead to generation of a polymeric Ub chain, with the C-terminus of one Ub linked to a residue in the preceding Ub molecule in the chain. Ub chains are typically linked via isopeptide bonds to one of Ub’s seven Lys side-chains, or via a peptide bond to Ub’s N-terminal a-amino group. Although the best studied Ub chains are “homotypic”, i.e. repeatedly linked to the same Ub site, it is now recognized that “branched” chains can form when Ubs that are already linked in a chain are further modified on additional sites

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Yamano H et al. (1996) The role of proteolysis in cell cycle progression in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. EMBO J 15 (19), 5268–79. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.King RW et al. (1996) How proteolysis drives the cell cycle. Science 274 (5293), 1652–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.King RW et al. (1995) A 20S complex containing CDC27 and CDC16 catalyzes the mitosis-specific conjugation of ubiquitin to cyclin B. Cell 81 (2), 279–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sudakin V et al. (1995) The cyclosome, a large complex containing cyclin-selective ubiquitin ligase activity, targets cyclins for destruction at the end of mitosis. Mol Biol Cell 6 (2), 185–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Irniger S et al. (1995) Genes involved in sister chromatid separation are needed for B-type cyclin proteolysis in budding yeast. Cell 81 (2), 269–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tugendreich S et al. (1995) CDC27Hs colocalizes with CDC16Hs to the centrosome and mitotic spindle and is essential for the metaphase to anaphase transition. Cell 81 (2), 261–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harper JW et al. (2002) The anaphase-promoting complex: it’s not just for mitosis any more. Genes Dev 16 (17), 2179–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang J and Bonni A (2016) A decade of the anaphase-promoting complex in the nervous system. Genes Dev 30 (6), 622–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eguren M et al. (2011) Non-mitotic functions of the Anaphase-Promoting Complex. Semin Cell Dev Biol 22 (6), 572–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang J et al. (2014) Functional characterization of Anaphase Promoting Complex/Cyclosome (APC/C) E3 ubiquitin ligases in tumorigenesis. Biochim Biophys Acta 1845 (2), 277–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zheng N et al. (2002) Structure of the Cul1-Rbx1-Skp1-F boxSkp2 SCF ubiquitin ligase complex. Nature 416 (6882), 703–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duda DM et al. (2008) Structural insights into NEDD8 activation of cullin-RING ligases: conformational control of conjugation. Cell 134 (6), 995–1006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Primorac I and Musacchio A (2013) Panta rhei: the APC/C at steady state. J Cell Biol 201 (2), 177–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sivakumar S and Gorbsky GJ (2015) Spatiotemporal regulation of the anaphase-promoting complex in mitosis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 16 (2), 82–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alfieri C et al. (2017) Visualizing the complex functions and mechanisms of the anaphase promoting complex/cyclosome (APC/C). Open Biol 7 (11). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schwab M et al. (1997) Yeast Hct1 is a regulator of Clb2 cyclin proteolysis. Cell 90 (4), 683–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Visintin R et al. (1997) CDC20 and CDH1: a family of substrate-specific activators of APC-dependent proteolysis. Science 278 (5337), 460–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kraft C et al. (2005) The WD40 propeller domain of Cdh1 functions as a destruction box receptor for APC/C substrates. Mol Cell 18 (5), 543–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kimata Y et al. (2008) A role for the Fizzy/Cdc20 family of proteins in activation of the APC/C distinct from substrate recruitment. Mol Cell 32 (4), 576–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Van Voorhis VA and Morgan DO (2014) Activation of the APC/C ubiquitin ligase by enhanced E2 efficiency. Curr Biol 24 (13), 1556–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chang LF et al. (2014) Molecular architecture and mechanism of the anaphase-promoting complex. Nature 513 (7518), 388–393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zachariae W et al. (1998) Mass spectrometric analysis of the anaphase-promoting complex from yeast: identification of a subunit related to cullins. Science 279 (5354), 1216–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yu H et al. (1998) Identification of a cullin homology region in a subunit of the anaphase-promoting complex. Science 279 (5354), 1219–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dube P et al. (2005) Localization of the coactivator Cdh1 and the cullin subunit Apc2 in a cryo-electron microscopy model of vertebrate APC/C. Mol Cell 20 (6), 867–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leverson JD et al. (2000) The APC11 RING-H2 finger mediates E2-dependent ubiquitination. Mol Biol Cell 11 (7), 2315–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tang Z et al. (2001) APC2 Cullin protein and APC11 RING protein comprise the minimal ubiquitin ligase module of the anaphase-promoting complex. Mol Biol Cell 12 (12), 3839–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gmachl M et al. (2000) The RING-H2 finger protein APC11 and the E2 enzyme UBC4 are sufficient to ubiquitinate substrates of the anaphase-promoting complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97 (16), 8973–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wild T et al. (2016) The Spindle Assembly Checkpoint Is Not Essential for Viability of Human Cells with Genetically Lowered APC/C Activity. Cell Rep 14 (8), 1829–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dimova NV et al. (2012) APC/C-mediated multiple monoubiquitylation provides an alternative degradation signal for cyclin B1. Nat Cell Biol 14 (2), 168–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Garnett MJ et al. (2009) UBE2S elongates ubiquitin chains on APC/C substrates to promote mitotic exit. Nat Cell Biol 11 (11), 1363–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Williamson A et al. (2009) Identification of a physiological E2 module for the human anaphase-promoting complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106 (43), 18213–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wu T et al. (2010) UBE2S drives elongation of K11-linked ubiquitin chains by the anaphase-promoting complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107 (4), 1355–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Meyer HJ and Rape M (2014) Enhanced protein degradation by branched ubiquitin chains. Cell 157 (4), 910–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kapanidou M et al. (2017) Cdc20: At the Crossroads between Chromosome Segregation and Mitotic Exit. Trends Biochem Sci 42 (3), 193–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thornton BR et al. (2006) An architectural map of the anaphase-promoting complex. Genes Dev 20 (4), 449–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vodermaier HC et al. (2003) TPR subunits of the anaphase-promoting complex mediate binding to the activator protein CDH1. Curr Biol 13 (17), 1459–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gieffers C et al. (2001) Three-dimensional structure of the anaphase-promoting complex. Mol Cell 7 (4), 907–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Herzog F et al. (2009) Structure of the anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome interacting with a mitotic checkpoint complex. Science 323 (5920), 1477–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Buschhorn BA et al. (2011) Substrate binding on the APC/C occurs between the coactivator Cdh1 and the processivity factor Doc1. Nat Struct Mol Biol 18 (1), 6–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Passmore LA et al. (2005) Structural analysis of the anaphase-promoting complex reveals multiple active sites and insights into polyubiquitylation. Mol Cell 20 (6), 855–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.da Fonseca PC et al. (2011) Structures of APC/C(Cdh1) with substrates identify Cdh1 and Apc10 as the D-box co-receptor. Nature 470 (7333), 274–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schreiber A et al. (2011) Structural basis for the subunit assembly of the anaphase-promoting complex. Nature 470 (7333), 227–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ohi MD et al. (2007) Structural organization of the anaphase-promoting complex bound to the mitotic activator Slp1. Mol Cell 28 (5), 871–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Davey NE and Morgan DO (2016) Building a Regulatory Network with Short Linear Sequence Motifs: Lessons from the Degrons of the Anaphase-Promoting Complex. Mol Cell 64 (1), 12–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Carroll CW et al. (2005) The APC subunit Doc1 promotes recognition of the substrate destruction box. Curr Biol 15 (1), 11–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Matyskiela ME and Morgan DO (2009) Analysis of activator-binding sites on the APC/C supports a cooperative substrate-binding mechanism. Mol Cell 34 (1), 68–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chang L et al. (2015) Atomic structure of the APC/C and its mechanism of protein ubiquitination. Nature 522 (7557), 450–454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Alfieri C et al. (2016) Molecular basis of APC/C regulation by the spindle assembly checkpoint. Nature 536 (7617), 431–436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brown NG et al. (2015) RING E3 mechanism for ubiquitin ligation to a disordered substrate visualized for human anaphase-promoting complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112 (17), 5272–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Brown NG et al. (2016) Dual RING E3 Architectures Regulate Multiubiquitination and Ubiquitin Chain Elongation by APC/C. Cell 165 (6), 1440–1453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yamaguchi M et al. (2016) Cryo-EM of Mitotic Checkpoint Complex-Bound APC/C Reveals Reciprocal and Conformational Regulation of Ubiquitin Ligation. Mol Cell 63 (4), 593–607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Li Q et al. (2016) WD40 domain of Apc1 is critical for the coactivator-induced allosteric transition that stimulates APC/C catalytic activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113 (38), 10547–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhang S et al. (2016) Molecular mechanism of APC/C activation by mitotic phosphorylation. Nature 533 (7602), 260–264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Qiao R et al. (2016) Mechanism of APC/CCDC20 activation by mitotic phosphorylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113 (19), E2570–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fujimitsu K et al. (2016) Cyclin-dependent kinase 1-dependent activation of APC/C ubiquitin ligase. Science 352 (6289), 1121–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Reddy SK et al. (2007) Ubiquitination by the anaphase-promoting complex drives spindle checkpoint inactivation. Nature 446 (7138), 921–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Stegmeier F et al. (2007) Anaphase initiation is regulated by antagonistic ubiquitination and deubiquitination activities. Nature 446 (7138), 876–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Miller JJ et al. (2006) Emi1 stably binds and inhibits the anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome as a pseudosubstrate inhibitor. Genes Dev 20 (17), 2410–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Frye JJ et al. (2013) Electron microscopy structure of human APC/C(CDH1)-EMI1 reveals multimodal mechanism of E3 ligase shutdown. Nat Struct Mol Biol 20 (7), 827–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang W and Kirschner MW (2013) Emi1 preferentially inhibits ubiquitin chain elongation by the anaphase-promoting complex. Nat Cell Biol 15 (7), 797–806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shteinberg M et al. (1999) Phosphorylation of the cyclosome is required for its stimulation by Fizzy/cdc20. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 260 (1), 193–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kramer ER et al. (2000) Mitotic regulation of the APC activator proteins CDC20 and CDH1. Mol Biol Cell 11 (5), 1555–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rudner AD and Murray AW (2000) Phosphorylation by Cdc28 activates the Cdc20-dependent activity of the anaphase-promoting complex. J Cell Biol 149 (7), 1377–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yamaguchi M et al. (2015) Structure of an APC3-APC16 complex: insights into assembly of the anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome. J Mol Biol 427 (8), 1748–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dou H et al. (2012) BIRC7-E2 ubiquitin conjugate structure reveals the mechanism of ubiquitin transfer by a RING dimer. Nat Struct Mol Biol 19 (9), 876–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pruneda JN et al. (2012) Structure of an E3:E2~Ub complex reveals an allosteric mechanism shared among RING/U-box ligases. Mol Cell 47 (6), 933–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Plechanovova A et al. (2012) Structure of a RING E3 ligase and ubiquitin-loaded E2 primed for catalysis. Nature 489 (7414), 115–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Reverter D and Lima CD (2005) Insights into E3 ligase activity revealed by a SUMO-RanGAP1-Ubc9-Nup358 complex. Nature 435 (7042), 687–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Min M et al. (2013) Ubiquitination site preferences in anaphase promoting complex/cyclosome (APC/C) substrates. Open Biol 3 (9), 130097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yu H et al. (1996) Identification of a novel ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme involved in mitotic cyclin degradation. Curr Biol 6 (4), 455–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Rape M et al. (2006) The processivity of multiubiquitination by the APC determines the order of substrate degradation. Cell 124 (1), 89–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kamenz J et al. (2015) Robust Ordering of Anaphase Events by Adaptive Thresholds and Competing Degradation Pathways. Mol Cell 60 (3), 446–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lu Y et al. (2015) Specificity of the anaphase-promoting complex: a single-molecule study. Science 348 (6231), 1248737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Brown NG et al. (2014) Mechanism of polyubiquitination by human anaphase-promoting complex: RING repurposing for ubiquitin chain assembly. Mol Cell 56 (2), 246–260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kelly A et al. (2014) Ubiquitin chain elongation requires E3-dependent tracking of the emerging conjugate. Mol Cell 56 (2), 232–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hoyt MA et al. (1991) S. cerevisiae genes required for cell cycle arrest in response to loss of microtubule function. Cell 66 (3), 507–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Li R and Murray AW (1991) Feedback control of mitosis in budding yeast. Cell 66 (3), 519–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Fang G (2002) Checkpoint protein BubR1 acts synergistically with Mad2 to inhibit anaphase-promoting complex. Mol Biol Cell 13 (3), 755–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Davenport J et al. (2006) Spindle checkpoint function requires Mad2-dependent Cdc20 binding to the Mad3 homology domain of BubR1. Exp Cell Res 312 (10), 1831–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Burton JL and Solomon MJ (2007) Mad3p, a pseudosubstrate inhibitor of APCCdc20 in the spindle assembly checkpoint. Genes Dev 21 (6), 655–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Di Fiore B and Pines J (2008) Defining the role of Emi1 in the DNA replication-segregation cycle. Chromosoma 117 (4), 333–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Izawa D and Pines J (2015) The mitotic checkpoint complex binds a second CDC20 to inhibit active APC/C. Nature 517 (7536), 631–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Di Fiore B et al. (2016) The Mitotic Checkpoint Complex Requires an Evolutionary Conserved Cassette to Bind and Inhibit Active APC/C. Mol Cell 64 (6), 1144–1153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Guardavaccaro D et al. (2003) Control of meiotic and mitotic progression by the F box protein beta-Trcp1 in vivo. Dev Cell 4 (6), 799–812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Margottin-Goguet F et al. (2003) Prophase destruction of Emi1 by the SCF(betaTrCP/Slimb) ubiquitin ligase activates the anaphase promoting complex to allow progression beyond prometaphase. Dev Cell 4 (6), 813–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Moshe Y et al. (2011) Regulation of the action of early mitotic inhibitor 1 on the anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome by cyclin-dependent kinases. J Biol Chem 286 (19), 16647–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Cappell SD et al. (2018) EMI1 switches from being a substrate to an inhibitor of APC/C(CDH1) to start the cell cycle. Nature 558 (7709), 313–317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Mansfeld J et al. (2011) APC15 drives the turnover of MCC-CDC20 to make the spindle assembly checkpoint responsive to kinetochore attachment. Nat Cell Biol 13 (10), 1234–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Foster SA and Morgan DO (2012) The APC/C subunit Mnd2/Apc15 promotes Cdc20 autoubiquitination and spindle assembly checkpoint inactivation. Mol Cell 47 (6), 921–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Uzunova K et al. (2012) APC15 mediates CDC20 autoubiquitylation by APC/C(MCC) and disassembly of the mitotic checkpoint complex. Nat Struct Mol Biol 19 (11), 1116–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Eifler K et al. (2018) SUMO targets the APC/C to regulate transition from metaphase to anaphase. Nat Commun 9 (1), 1119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Lee CC et al. (2018) Sumoylation promotes optimal APC/C Activation and Timely Anaphase. Elife 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Craney A et al. (2016) Control of APC/C-dependent ubiquitin chain elongation by reversible phosphorylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113 (6), 1540–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Hein MY et al. (2015) A human interactome in three quantitative dimensions organized by stoichiometries and abundances. Cell 163 (3), 712–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Zhang Z et al. (2013) The four canonical tpr subunits of human APC/C form related homo-dimeric structures and stack in parallel to form a TPR suprahelix. J Mol Biol 425 (22), 4236–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Zachariae W and Nasmyth K (1996) TPR proteins required for anaphase progression mediate ubiquitination of mitotic B-type cyclins in yeast. Mol Biol Cell 7 (5), 791–801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Zhang Z et al. (2010) The APC/C subunit Cdc16/Cut9 is a contiguous tetratricopeptide repeat superhelix with a homo-dimer interface similar to Cdc27. EMBO J 29 (21), 3733–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Wang J et al. (2009) Insights into anaphase promoting complex TPR subdomain assembly from a CDC26-APC6 structure. Nat Struct Mol Biol 16 (9), 987–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Zachariae W et al. (1998) Control of cyclin ubiquitination by CDK-regulated binding of Hct1 to the anaphase promoting complex. Science 282 (5394), 1721–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Jaspersen SL et al. (1999) Inhibitory phosphorylation of the APC regulator Hct1 is controlled by the kinase Cdc28 and the phosphatase Cdc14. Curr Biol 9 (5), 227–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Visintin R et al. (1998) The phosphatase Cdc14 triggers mitotic exit by reversal of Cdk-dependent phosphorylation. Mol Cell 2 (6), 709–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]