Abstract

Purpose

This study aimed to estimate the prevalence, prescription pattern and burden of pediatric asthma in Korea by analyzing the National Health Insurance (NHI) claims data.

Methods

We retrospectively analyzed the insurance claim records from the Korean NHI claims database from January 2010 to December 2014. Asthmatic patients were defined as children younger than 18 years, with appropriate 10th Revision of the International Classification of Diseases codes (J45 or J46) and a prescription for 1 or more asthma maintenance medications at the same date. Hospitalization and emergency department visits for asthma were defined as use of short-acting beta2-agonists during hospital visits among asthmatic patients.

Results

There were 1,172,807 asthmatic children in 2010, which increased steadily to 1,590,228 in 2014 in Korea. The prevalence showed an increasing trend annually for all ages. The mean prevalence by age in those older than 2 years decreased during the study period (from 39.4% in the 2–3 year age group to 2.6% in the 15–18 year age group). In an outpatient prescription, leukotriene receptor antagonists were the most commonly prescribed medication for all ages. Patients older than 6 years for whom inhaled corticosteroids were prescribed comprised less than 15% of asthmatic patients. The total direct medical cost for asthma between 2010 and 2014 ranged from $376 to $483 million. Asthma-related medical cost per person reached its peak in $366 in 2011 and decreased to $275 in 2014.

Conclusions

The prevalence of pediatric asthma increased annually and decreased with age. Individual cost of asthma showed a decreasing trend in Korean children.

Keywords: Asthma, illness burden, child, insurance claims analysis, prescription, prevalence

INTRODUCTION

Asthma is one of the most common chronic diseases in childhood. Pediatric asthma is a major concern because it increases the number of hospital visits and economic burden more than asthma in adults.1,2 In the 2000s, many studies have shown that asthma prevalence is increasing globally over a short period, due to the impact of environmental risk factors in addition to genetic factors.3,4 Some recent reports have suggested that the prevalence of pediatric asthma may have plateaued or declined in some developed countries.5,6,7,8 Asthma prevalence is changing over time and varies among countries and regions. The prevalence of adult asthma in Korea has been increasing in recent decades.9 It is important to estimate the prevalence of asthma as time changes in an area because appropriate treatment and prevention strategies for pediatric asthma should be based on accurate assessment of prevalence and risk factors for the pediatric population.10

The National Health Insurance (NHI) claims database could provide epidemiological data and information for studies on health care utilization and medical expenditure. The major mechanism for health care financing in Korea is the NHI, which covers the entire population, because enrollment in the NHI is compulsory.11 The Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service receives the claims data of 97% of the Korean population.12 The NHI service database represents the entire population and can, therefore, be used as a population-based database.13 Therefore, the NHI enabled us to estimate the nationwide prevalence and financial burden of pediatric asthma.11

The purpose of this study was to retrospectively analyze the NHI claims database to estimate the prevalence of childhood asthma in Korea, prescription patterns and its economic burden. Furthermore, compliance with the guidelines for the treatment and prevention of pediatric asthma can be assessed by analyzing treatment patterns in the NHI data.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data source and study population

We analyzed the insurance claims records of the Korean NHI claims database from January 2010 to December 2014. Through this retrospective population-based study, we estimated the prevalence of asthma in children in Korea and investigated their asthma-related health care utilization, prescription and test patterns. Asthmatic patients in this study were defined as children who were younger than 18 years who visited hospital with an asthma code of J45 or J46 for the principal or within 5 additional diagnoses based on the 10th Revision of the International Classification of Diseases. Additionally, they required a prescription for asthma maintenance medication such as inhaled corticosteroid (ICS), ICS/long-acting beta2-agonist (LABA) combination inhaler or leukotriene receptor antagonist (LTRA) on the same date. Population data by age with health insurance were used to estimate the prevalence of asthma by age. In terms of hospitalization and emergency department (ED) visits for asthma, asthmatic patients were defined as the use of short-acting beta2-agonist (SABA) during the hospital visit under the asthma definition in the current study. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Severance Hospital (protocol no. 4-2015-0891). The requirement for informed consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the study.

Asthma-related medications and tests

Asthma-related medications included SABA, ICS, ICS/LABA combination inhaler, LTRA, aminophylline/theophylline and systemic steroids (Supplementary Table S1). Analysis of drug prescribing frequency in asthmatic patients only included outpatient prescriptions. Asthma-related tests included spirometry with/without bronchodilator and allergy tests such as multiple-allergen simultaneous test, serum total or allergen-specific Immunoglobulin E levels and skin prick test.

Asthma-related costs

In a prevalence and cost-of-illness study, the cost of an illness in a population is measured over a defined period, usually a year.14 The economic costs of a disease can be classified as direct, indirect or intangible costs. Direct costs comprise all direct medical cost, of which include expenditures for diagnosis, treatment, continuing care, rehabilitation, terminal care for an illness15 and direct non-medical costs. Direct medical costs are defined as formal expenses for the diagnosis and treatment of asthma within the official health care system and consist of inpatient and outpatient care costs. In the current study, asthma-related cost was defined as the sum of the direct medical costs, which consisted of asthma-related hospitalizations, outpatient visits, ED visits and the costs of prescribed medications. The outpatient visits were divided into primary hospital, secondary hospital and tertiary hospital visits. Expenses not covered by insurance were excluded in the calculation. All costs were calculated in KRW then converted into USD using the exchange rate of 1 USD at 1,107 KRW, which is the average exchange rate between 2010 and 2014.

RESULTS

Asthma prevalence, asthma-related hospital visits and tests

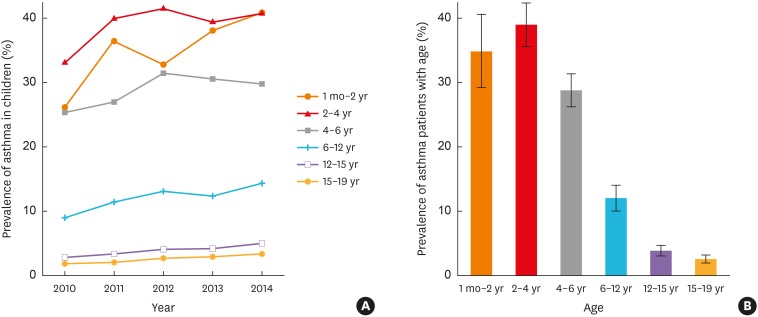

The number of asthmatic children (from 1 month to 18 years old) on record was 1,172,807 in 2010 and increased steadily to 1,590,228 in 2014 in Korea (Table 1). In 2014, 16,110 (male 16,720; female 15,010) patients per 100,000 children had asthma compared to 10,780 (male 11,370; female 9,930) patients per 100,000 in 2010 (Table 1, Supplementary Table S2). The annual trend of increasing prevalence was noted for all ages (Fig. 1A). Asthma prevalence decreased with increasing age and the peak prevalence was mostly noted in the age group 2–4 years (33.1%–41.5%) (Fig. 1B, Table 1).

Table 1. Prevalence of asthma according to age.

| 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population* | ||||||

| Total | 10,476,414 (100.00) | 10,266,580 (100.00) | 10,085,908 (100.00) | 9,853,821 (100.00) | 9,618,446 (100.00) | |

| 1 mon–2 yr | 880,973 (100.00) | 912,069 (100.00) | 926,206 (100.00) | 899,343 (100.00) | 854,183 (100.00) | |

| 2–4 yr | 946,479 (100.00) | 901,069 (100.00) | 907,557 (100.00) | 936,832 (100.00) | 955,750 (100.00) | |

| 4–6 yr | 867,117 (100.00) | 927,946 (100.00) | 948,938 (100.00) | 903,870 (100.00) | 909,869 (100.00) | |

| 6–12 yr | 3,178,694 (100.00) | 3,008,608 (100.00) | 2,833,814 (100.00) | 2,779,081 (100.00) | 2,759,627 (100.00) | |

| 12–15 yr | 1,905,874 (100.00) | 1,847,888 (100.00) | 1,825,170 (100.00) | 1,753,637 (100.00) | 1,637,202 (100.00) | |

| 15–19 yr | 2,697,277 (100.00) | 2,668,277 (100.00) | 2,644,223 (100.00) | 2,581,058 (100.00) | 2,501,815 (100.00) | |

| Subjects | ||||||

| Total | 1,172,807 (11.19) | 1,428,081 (13.91) | 1,518,842 (15.06) | 1,499,803 (15.22) | 1,590,228 (16.53) | |

| 1 mon–2 yr | 233,405 (26.49) | 336,236 (36.87) | 307,247 (33.17) | 345,706 (38.44) | 351,302 (41.13) | |

| 2–4 yr | 317,577 (33.55) | 365,229 (40.51) | 380,955 (41.98) | 373,378 (39.86) | 391,773 (40.99) | |

| 4–6 yr | 223,874 (25.82) | 254,485 (27.42) | 302,400 (31.87) | 279,654 (30.94) | 273,866 (30.10) | |

| 6–12 yr | 293,444 (9.23) | 352,732 (11.72) | 378,990 (13.37) | 349,145 (12.56) | 403,312 (14.61) | |

| 12–15 yr | 54,907 (2.88) | 64,217 (3.48) | 76,293 (4.18) | 75,049 (4.28) | 83,807 (5.12) | |

| 15–19 yr | 49,600 (1.84) | 55,182 (2.07) | 72,957 (2.76) | 76,871 (2.98) | 86,168 (3.44) | |

Values are presented as number (%).

*Number of population with health insurance by age.

Fig. 1. Prevalence of asthma in children according to year (A) and age (B). The prevalence showed an increasing trend annually and decreased with age.

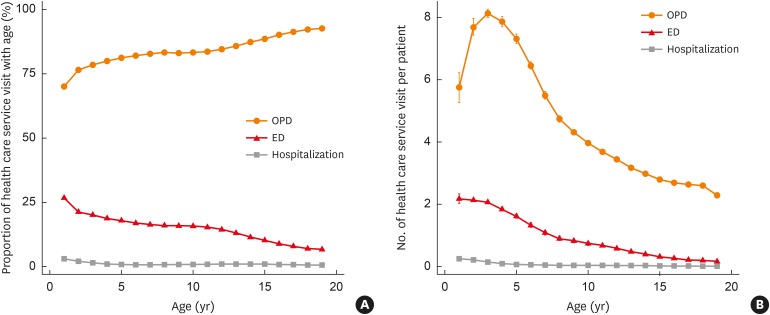

The distribution of asthma-related health service use according to age during the study period was investigated (Fig. 2, Supplementary Table S3). The proportions of outpatient clinic visit among the types of healthcare facilities increased with age (Fig. 2A, Supplementary Table S3). The frequency of outpatient clinic visits among children with asthma was highest in the 2–4 years age group, and decreased with age (Fig. 2B, Supplementary Table S3). The proportion and frequency of ED visits decreased with age (Fig. 2, Supplementary Table S3). Annually, approximately 68% of children younger than 2 years visited the ED and about 18% of them were hospitalized at least once due to asthma (Supplementary Table S3). While both proportions decreased with increasing age, the proportion of outpatient clinic visits remained steady in the range 95%–99%, through all age groups (Supplementary Table S3).

Fig. 2. The patterns of health care service use with age. The graphs show the mean proportion (A) and numbers (B) of visits by health care service type between 2010 and 2014. Error bars show the minimum and maximum values.

OPD, outpatient department; ED, emergency department.

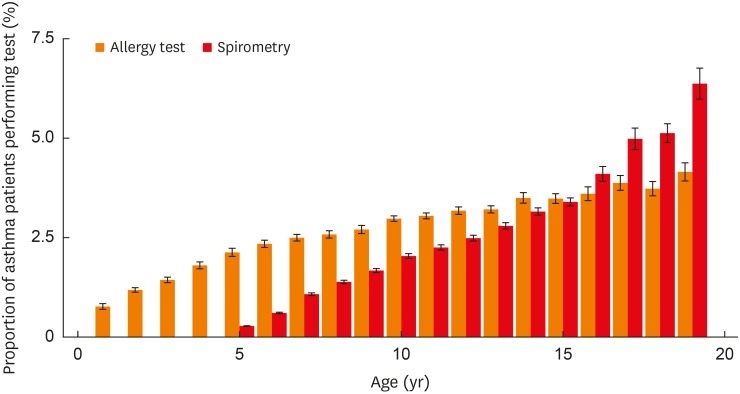

Spirometry for pulmonary function test (PFT) was performed in 0.4%–5.7% of asthmatic patients older than 4 years and allergy test was performed in 0.9%–4.4% of them. A higher proportion of those for whom asthma related tests were performed were older children (Fig. 3, Supplementary Table S4).

Fig. 3. The mean proportions of asthma patients who underwent spirometry and allergy test at least once each year during the study period (2010-2014). Error bars show the standard error.

Patterns of asthma medication prescriptions

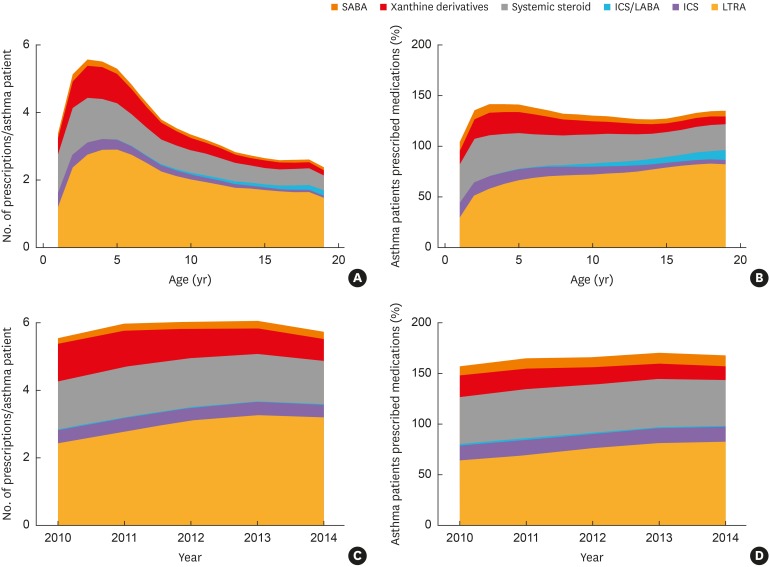

Fig. 4 shows the prescription patterns of asthma medication according to age in outpatients. LTRAs were the most commonly prescribed asthma medications for all ages (Fig. 4A). After 2 years of age, the majority of asthmatic patients received prescriptions for LTRAs, and this proportion of patients increased with increasing age (Fig. 4B). The overall proportion of patients who were prescribed ICS or ICS/LABA combination inhalers was less than 15%. While the proportion of asthmatic children prescribed ICS decreased by age and fell to 4.2% in the 15–19 year age group, the proportion of patients prescribed ICS/LABA combination inhalers increased to 10% among those aged 18 years (Fig. 4B, Supplementary Table S5). The number of systemic steroid prescriptions declined with age (Fig. 4A, Supplementary Table S6). Systemic steroids were prescribed at least once in 25%-42% of the asthmatic patients and the proportion of patients for whom it was prescribed slightly decreased with age (Fig. 4B, Supplementary Table S5). The proportion of patients for whom xanthine derivatives were prescribed at least once and declined with age (Fig. 4B, Supplementary Table S5). Between 2010 and 2014, the proportion of patients for whom LTRAs were prescribed and the number of LTRA prescriptions per person increased over time for all the ages, while the proportion of patients for whom ICS or ICS/LABA combination inhalers were prescribed decreased (Fig. 4C and D, Supplementary Tables S5 and S6). The proportions of patients for whom xanthine derivatives were prescribed and the number of prescriptions per person decreased gradually during the study period (Fig. 4C and D, Supplementary Tables S5 and S6). There was no significant change in the number of prescribed systemic corticosteroids.

Fig. 4. The patterns of asthma-related medication prescription by age. (A) The number of prescription per person by age. (B) Percentage of asthmatic patients with prescribed asthma medications by age. (C) The number of prescription per person per year. (D) Percentage of asthmatic patients with prescribed asthma medications per year.

SABA, short-acting beta2-agonist; ICS, inhaled corticosteroid; LABA, long-acting beta2-agonist; LTRA, leukotriene receptor antagonist.

Economic burden of pediatric asthma

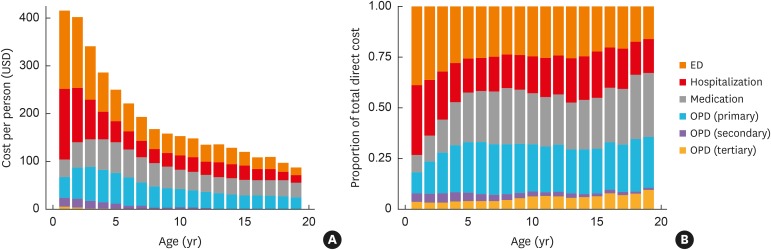

The direct medical costs of asthma during the years 2010–2014 are presented in Supplementary Table S7 and Fig. 5. While there was an increase of 35.6% (from 1,172,807 to 1,590,228) in the number of children with asthma between 2010 and 2014, there was no significant increase in the annual total direct medical costs for asthma or the annual direct medical expenses per person decreased. The total age- and year-specific asthma-related costs ranged from 109 USD (120,747 KRW) in the 15–19 years age group in 2013 to 508 USD (562,747 KRW) in those aged 1 month–2 years in 2010. Over the entire 5 years, the mean direct medical cost per patient decreased with increasing age, from 447 USD (495,173 KRW) in the age group of less-than-2-year-olds to 121 USD (134,040 KRW) in the 15-19 years age group.

Fig. 5. Asthma-related direct costs by age. (A) Cost per patient. (B) The proportion of cost in each subgroup.

ED, emergency department; OPD, outpatient department.

The total cost of medications prescribed for patients with asthma younger than 18 years amounted to 105 million USD in 2011, but declined to 70 million USD in 2014. The cost of asthma medication per person each year also decreased from 87 USD in 2011 to 53 USD in 2014. The total direct medical cost for the treatment of pediatric asthma showed a declining trend during the recent 5 years.

In terms of the proportion of composition in total direct medical costs, hospitalizations and ED visits made up more than half of the total cost in the age group younger than 4 years, while medications and hospital outpatient visits constituted the most costs in those older than 12 years (Fig. 5B). The total cost per person in each subcategory showed a decreasing trend with age and the number of ED visits and hospital admissions showed the greatest difference with increasing age (Supplementary Fig. S1).

DISCUSSION

We analyzed the NHI claims database to investigate the incidence, prescribing patterns and economic burden of pediatric asthma in Korea between 2010 and 2014. The estimation of the prevalence and economic burden, and analysis of prescription patterns in pediatric asthma are essential for evaluating the current treatment trend for pediatric asthma control.

In this study, the overall prevalence of asthma in all children younger than 18 years was 14.3%. Previous epidemiological studies reported a lower or similar prevalence of asthma in Korea compared to our study.16,17

According to age, the prevalence of asthma was slightly different for each age group, but increased over the study period. The incidence of asthma decreased after the age of 2 years and was more than 20% until school age. Asthma in children younger than 2 years can be overdiagnosed because it is difficult to distinguish between asthma and bronchiolitis or other respiratory diseases presenting with wheezing other than asthma. The diagnosis of asthma in children younger than 5 years is predominantly clinical, since there is currently no satisfactory means of making an accurate diagnosis. Therefore, the diagnosis of pediatric asthma among children younger than 5 years can be overestimated.

The Asthma Insights and Reality surveys revealed that spirometry is rarely performed in children with asthma in Asia; 75% of children in Asia-Pacific countries had never undergone PFT.18 This study also showed a low PFT performance rate because it is difficult to perform spirometric measurements in the primary care settings at most of the asthmatic children visits. Furthermore, children younger than 6 years who have difficulty with forced inspiration and expiration may require encouragement from a respiratory technician or physician.

The mainstay of asthma pharmacotherapy has been the use of ICS as the first-line therapy in all asthmatic patients including younger children.19 In the current study, the most frequently prescribed asthma maintenance medication was LTRA in all age groups, even for the 15–19 year age group. Patients older than 6 years for whom ICS-based inhalers were prescribed comprised less than 15% of asthma patients, which is lower than the 30% found in a population-based cohort study in a Dutch primary care database.20 It was thought that oral LTRAs were more often prescribed than ICS-based inhalers because asthmatic children and parents have a higher preference for oral medications. Furthermore, there are restrictions on ICS prescription in outpatient clinics in Korea because it takes much time and practice to educate the patient about the use of the inhaler.

The leading contributors to the direct medical expenses for asthmatic children in Korea were hospitalization and ED visits in children younger than 4 years, accounting for more than half of the total direct costs. Asthmatic children younger than 2 years were more likely to visit the hospital and ED due to the use of asthma-related health care services. On the other hand, medications and primary outpatient visits accounted for about a quarter of the total direct costs of children older than 4 years.

The decrease in annual asthma-related costs per person was in line with decreases in drug prescriptions, outpatient department (OPD) visits, particularly visits to tertiary hospitals, and in turn, ED visits. LTRA and ICS-based inhalers prescriptions for asthma maintenance therapy have increased. This seems to be due to the early diagnosis and treatment of pediatric asthma and an increase in the incidence of mild asthma. Proper maintenance therapy for asthma can reduce the risk of asthmatic attacks, total drug treatment costs, and OPD or ED visits.21,22

The strength of the current study compared to other similar prior studies is that the data base obtained from the Korean NHI provides a unique and comprehensive opportunity to evaluate the prevalence of pediatric asthma because Korean NHI include most people in Korea. Therefore, this study is clinically relevant and significant for improved management of pediatric asthma based on the prior clinical services provided.

This study has several limitations. The prevalence of asthma in young children might be overestimated, although maintenance therapy was included for asthma diagnosis. Recent studies have shown that about half of children with asthma were diagnosed excessively without PFTs because of symptoms such as dyspnea, coughing and wheezing.23,24 On the other hand, the number of asthmatic patients, especially those with mild asthma not receiving maintenance therapy, could have been underestimated because patients with asthma included those who were symptomatic and for whom asthma medications were prescribed. Drug prescriptions for asthma guidelines could not be accurately assessed because asthmatic patients were not classified according to asthma severity. Finally, the medical costs can be affected by the Drug Use Review (DUR) system. DUR is a systematic review program for patient safety that begins in 2011 in Korea, which determines whether or not patients receive or prescribe appropriate medications.25

The prevalence of asthma in children younger than 18 years increased annually and decreased with age. PFTs were performed in less than 5% of asthmatic patients older than 4 years. LTRA was the most frequently prescribed medication in all age groups. During the study period, the total direct medical costs for the treatment and prevention of asthma in children have not significantly changed, but the average cost per person has decreased.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by a grant of the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI), funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (HI17C0104), by Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT & Future Planning (NRF-2017R1A2B2004043 and NRF-2018R1A5A2025079), and by Institute for Information & communications Technology Promotion (IITP) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (No. 2017-0-00599, Development of Big Data Analytics Platform for Military Health Information).

Footnotes

Disclosure: There are no financial or other issues that might lead to conflict of interest.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Drug substance code related to asthma

Prevalence of asthma according to age and sex

Visiting patterns of asthmatic children by the type of health service

Performance of asthma-related tests

The proportion of patients who received asthma-related medications in outpatient settings among asthmatic patients

The number of asthma-related medications prescribed in outpatient settings per asthma patient every year

Asthma-related direct medical costs (USD)

Asthma-related direct costs according to health care service and medication by age.

References

- 1.Lee-Sarwar KA, Bacharier LB, Litonjua AA. Strategies to alter the natural history of childhood asthma. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;17:139–145. doi: 10.1097/ACI.0000000000000340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bahadori K, Doyle-Waters MM, Marra C, Lynd L, Alasaly K, Swiston J, et al. Economic burden of asthma: a systematic review. BMC Pulm Med. 2009;9:24. doi: 10.1186/1471-2466-9-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nunes C, Pereira AM, Morais-Almeida M. Asthma costs and social impact. Asthma Res Pract. 2017;3:1. doi: 10.1186/s40733-016-0029-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chung F, Barnes N, Allen M, Angus R, Corris P, Knox A, et al. Assessing the burden of respiratory disease in the UK. Respir Med. 2002;96:963–975. doi: 10.1053/rmed.2002.1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pearce N, Aït-Khaled N, Beasley R, Mallol J, Keil U, Mitchell E, et al. Worldwide trends in the prevalence of asthma symptoms: phase III of the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) Thorax. 2007;62:758–766. doi: 10.1136/thx.2006.070169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kälvesten L, Bråbäck L. Time trend for the prevalence of asthma among school children in a Swedish district in 1985–2005. Acta Paediatr. 2008;97:454–458. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2008.00698.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee YL, Hwang BF, Lin YC, Guo YL Taiwan Childhood Allergy Survey Group. Time trend of asthma prevalence among school children in Taiwan. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2007;18:188–195. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.2006.00504.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schröder PC, Li J, Wong GW, Schaub B. The rural-urban enigma of allergy: what can we learn from studies around the world? Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2015;26:95–102. doi: 10.1111/pai.12341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Park SY, Kim JH, Kim HJ, Seo B, Kwon OY, Chang HS, et al. High prevalence of asthma in elderly women: findings from a Korean national health database and adult asthma cohort. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2018;10:387–396. doi: 10.4168/aair.2018.10.4.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee SI. Prevalence of childhood asthma in Korea: International Study of Asthma and Allergies in childhood. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2010;2:61–64. doi: 10.4168/aair.2010.2.2.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kwon S. Payment system reform for health care providers in Korea. Health Policy Plan. 2003;18:84–92. doi: 10.1093/heapol/18.1.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koo BK, Lee JH, Kim J, Jang EJ, Lee CH. Prevalence of gestational diabetes mellitus in Korea: a National Health Insurance database study. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0153107. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0153107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Song SO, Jung CH, Song YD, Park CY, Kwon HS, Cha BS, et al. Background and data configuration process of a nationwide population-based study using the Korean national health insurance system. Diabetes Metab J. 2014;38:395–403. doi: 10.4093/dmj.2014.38.5.395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gergen PJ. Understanding the economic burden of asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;107(Suppl):S445–S448. doi: 10.1067/mai.2001.114992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saha S, Gerdtham UG. Cost of illness studies on reproductive, maternal, newborn, and child health: a systematic literature review. Health Econ Rev. 2013;3:24. doi: 10.1186/2191-1991-3-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jang Y, Shin A. Sex-based differences in asthma among preschool and school-aged children in Korea. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0140057. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0140057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim BK, Kim JY, Kang MK, Yang MS, Park HW, Min KU, et al. Allergies are still on the rise? A 6-year nationwide population-based study in Korea. Allergol Int. 2016;65:186–191. doi: 10.1016/j.alit.2015.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rabe KF, Adachi M, Lai CK, Soriano JB, Vermeire PA, Weiss KB, et al. Worldwide severity and control of asthma in children and adults: the global asthma insights and reality surveys. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;114:40–47. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.04.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) Diagnosis and management of asthma in children 5 years and younger 2015 [Internet] place unknown: Global Initiative for Asthma; 2015. [cited 2017 Jan 30]. Available from: http://ginasthma.org. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Engelkes M, Janssens HM, de Jongste JC, Sturkenboom MC, Verhamme KM. Prescription patterns, adherence and characteristics of non-adherence in children with asthma in primary care. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2016;27:201–208. doi: 10.1111/pai.12507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moorman JE, Akinbami LJ, Bailey CM, Zahran HS, King ME, Johnson CA, et al. National surveillance of asthma: United States, 2001–2010. Vital Health Stat 3. 2012:1–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Klok T, Kaptein AA, Duiverman EJ, Brand PL. High inhaled corticosteroids adherence in childhood asthma: the role of medication beliefs. Eur Respir J. 2012;40:1149–1155. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00191511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang CL, Simons E, Foty RG, Subbarao P, To T, Dell SD. Misdiagnosis of asthma in schoolchildren. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2017;52:293–302. doi: 10.1002/ppul.23541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Looijmans-van den Akker I, van Luijn K, Verheij T. Overdiagnosis of asthma in children in primary care: a retrospective analysis. Br J Gen Pract. 2016;66:e152–e157. doi: 10.3399/bjgp16X683965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang JH, Kim M, Park YT, Lee EK, Jung CY, Kim S. The effect of the introduction of a nationwide DUR system where local DUR systems are operating--the Korean experience. Int J Med Inform. 2015;84:912–919. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2015.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Drug substance code related to asthma

Prevalence of asthma according to age and sex

Visiting patterns of asthmatic children by the type of health service

Performance of asthma-related tests

The proportion of patients who received asthma-related medications in outpatient settings among asthmatic patients

The number of asthma-related medications prescribed in outpatient settings per asthma patient every year

Asthma-related direct medical costs (USD)

Asthma-related direct costs according to health care service and medication by age.