Abstract

Provision of health care for refugees poses many political, economical, and ethical questions. Data on the prevalence and management of refugees with end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) are scant. Nevertheless, the impact of refugees in need for renal replacement can be as high for the patient as for the receiving centers. The International Society of Nephrology and the European Renal Association/European Dialysis and Transplant Association surveyed their membership through Survey Monkey questionnaires to obtain data on epidemiology and management practices of refugees with ESKD. Refugees represent 1.5% of the dialysis population, but their geographic distribution is very skewed: ±60% of centers treat 0, 15% treat 1, and a limited number of centers treat >20 refugees. Knowledge on financial and legal management of these patients is low. There is a lack of a structured approach by the government. Most respondents stated we have a moral duty to treat refugee patients with ESKD. Cultural rather than linguistic differences were perceived as a barrier for optimal care. Provision of dialysis for refugees with ESKD seems sustainable and logistically feasible, as they are only 1.5% of the regular dialysis population, but the skewed distribution potentially threatens optimal care. There is a need for education on financial and legal aspects of management of refugees with ESKD. Clear guidance from governing bodies should avoid unacceptable ethical dilemmas for the individual physician. Such strategies should balance access to care for all with equity and solidarity without jeopardizing the health care of the local population.

Keywords: chronic kidney disease, end-stage kidney disease, refugee, renal replacement therapy

The recent refugee crisis is considered one of the largest humanitarian and political challenges of recent decades. This crisis is a strenuous real practice test for the ethical concepts we take to be well established.1 In our globalized society with omnipresent social media, we cannot ignore the crisis and the choices it brings. How we choose to respond directly affects the destiny of other human beings. In this era of sophisticated medical technology, a special consideration should go to those depending on that technology for their health and their lives, from very basic needs such as transplant patients for availability of their medication, to patients sustained on sophisticated life support in intensive care. In this setting, the global nephrological community is challenged with providing medical care to patients in need of renal replacement, a task with substantial ethical and financial consequences.

To the best of our knowledge, reports on kidney care in refugees until now have been scarce. Already in 1993, a report on the fate of end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) patients during the war in Iraq indicated that during conditions of war, insufficient access to dialysis and substantial shortening of treatments resulted in higher than expected mortality.2 During this war, one-half of the patients fled the country as refugees. In a study on Afghan refugees in Iran, Otoukesh et al.3 pointed out that a large proportion of referrals for kidney problems were for ESKD imposing an important financial burden on the hosting country.4 Among Syrian refugees in Jordan, the prevalence of chronic disorders that are at the origin of chronic kidney disease (diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular disease) was found to be high. In addition to fleeing their country because of conditions of war, refugees also sought care for these ailments. It is also reported that poor social status and substantial changes in lifestyle predispose refugees to develop chronic conditions such as hypertension, cardiovascular disease, or diabetes,5 which are all risk factors for chronic kidney disease.

The Renal Disaster Relief Task Force (RDRTF) of the International Society of Nephrology (ISN) and the European Renal Association/European Dialysis and Transplant Association (ERA-EDTA) surveyed the nephrological community on practical aspects of renal replacement therapy and nephrological care for refugees with ESKD. Our objective was to collect information on the size of the problem and on the views of the nephrological community on this topic.

Results

Epidemiology

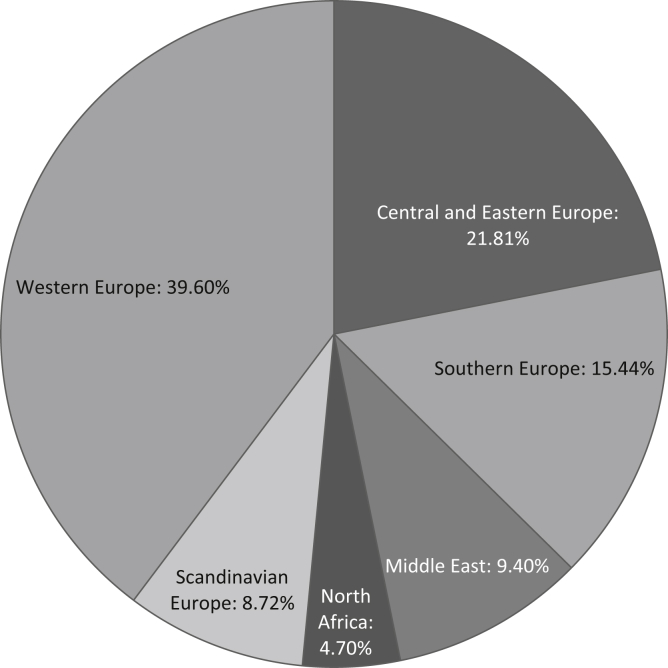

In total, 298 individual centers provided complete responses to the ISN survey (Figure 1, Table 1). Together, these centers had dialyzed 631 refugees in the 4 months before the survey. The total population of the centers who underwent regular dialysis was 40,378, so refugees represented about 1.5% of the represented dialysis population.

Figure 1.

Geographic distribution of respondents.

Table 1.

Geographic origin of respondents, with numbers of refugees on dialysis, by country

| Region | Country (centers [n], refugees on dialysis in preceding 4 months [n]) |

|---|---|

| Central and Eastern Europe | Albania (2, 2), Bulgaria (2, 0), Croatia (2, 0), Czech Republic (6, 0), Estonia (1, 0), Hungary (1, 1), Lithuania (6, 0), Macedonia (2, 2), Poland (2, 0), Romania (12, 0), Serbia (2, 8), Slovenia (4, 1), Turkey (23, 121) |

| Southern Europe | Greece (17, 22), Italy (13, 3), Portugal (1, 0), Spain (15, 3) |

| Middle East | Israel (5, 1), Iran (7, 6), Iraq (2, 30), Jordan (1, 0), Kuwait (1, 9), Lebanon (3, 31), Saudi Arabia (5, 20), United Arab Emirates (3, 1), Yemen (1, 80) |

| North Africa | Algeria (1, 2), Egypt (7, 0), Morocco (4, 0), Tunisia (3, 0) |

| North America | Canada (1, 0) |

| Scandinavian Europe | Denmark (3, 2), Finland (2, 0), Norway (1), Sweden (20, 32) |

| Western Europe | Austria (3, 3), Belgium (20, 67), France (15, 61), Germany (14, 28), Ireland (2, 0), Luxembourg (1, 0), Scotland (1, 0), Switzerland (17, 33), The Netherlands (27, 28), United Kingdom (18, 113) |

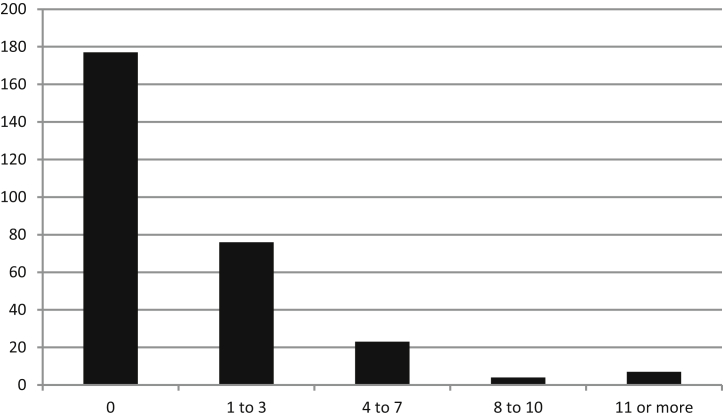

Of the responding centers, 177 (59.4%) reported that no refugees had been dialyzed in their unit over the preceding 4 months. Forty-two centers reported that they had treated 1 refugee, 21 centers had treated 2, 13 centers had treated 3, 8 centers had treated 4, 7 centers had treated 5, 5 centers had treated 6, and 3 centers had treated 7 refugee patients (Figure 2). Centers that reported to have treated >8 refugee patients had often substantially higher numbers, ranging up to 80 for a center in Yemen, where they provided once-weekly dialysis to maximize access for patients.

Figure 2.

Y-axis: number of responding dialysis centers; x-axis: number of refugee patients on dialysis treated in that dialysis center.

Thirty-three centers declared they refused dialysis to ≥1refugee. One center very close to an active war zone reported they had been obliged to refuse about 250 patients in need of dialysis because of a lack of resources. One center in Western Europe declined 25 refugee patients (but accepted 25 others) as the cost was to be supported by the nephrology department. Other centers reporting high refusal rates stated that they had requested patients to pay for their treatment.

Financial and legal regulations and policies

Reimbursement for dialysis for officially registered refugees with legal permission to stay in the country was covered by a national government in less than one-half of cases, and regional or local governments covered costs in about 25% of cases (Table 2). In a minority of cases, hospitals or nephrology units had to support the treatment themselves, or patients had to pay out of pocket.

Table 2.

Reimbursement of financial costs related to dialysis according to respondents

| Payment source (%) | Status of refugee |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Awaiting official registration or illegal | Registered, awaiting decision | Registered, permitted to stay | |

| National government | 30.9 | 40.9 | 38.9 |

| Regional government | 8.4 | 10.7 | 13.1 |

| Local government/social service | 4.7 | 9.1 | 12.1 |

| Hospital | 14.4 | 8.1 | 4.0 |

| Nephrology department | 1.3 | 1.0 | 2.0 |

| Patient | 7.0 | 3.0 | 2.4 |

| Unknown | 27.9 | 21.1 | 17.5 |

| Other | 5.4 | 6.0 | 10.1 |

There was a great deal of inconsistency in responses within the same country and even within the same region, where it was likely that legal regulations were similar. The cost of dialysis for refugees without official status was claimed to be covered by a government body by 40% of respondents. Up to 27.9% of the respondents admitted that they did not know who should pay for the dialysis of nonregistered refugee patients.

In many centers there was uncertainty and a lack of clear direction on how refugees with ESKD should be managed. Only about one-quarter of centers (24.5%) received clear instructions from their government that refugees who needed dialysis should receive it. About one-half the centers (46%) did not receive instructions from their government, but did obtain approval from their hospital administration to dialyze refugee patients if needed. Only one center stated that they received orders from the government not to treat refugee patients, and for 3.7% of centers, this order not to treat was issued by the hospital administration. One-quarter of centers reported that they were not aware of any instruction from their government or from the hospital administration, and of these, a large majority treated 0, 1, or 2 refugees (60, 8, and 2 centers of 74, respectively).

Attitudes toward transplantation for refugees

A small majority of centers (57.5%) listed refugees on their waiting list for renal (cadaveric) transplantation once they had obtained legal permission to remain in the country on a permanent basis. A substantial number (17.4%) declared that refugees were wait-listed irrespective of their official status, and one-quarter of centers never wait-listed refugee patients (15.7%), or only accepted them for a living donation transplantation if they provided a live donor and paid for the procedure themselves (9.1%).

How refugee status affects medical management

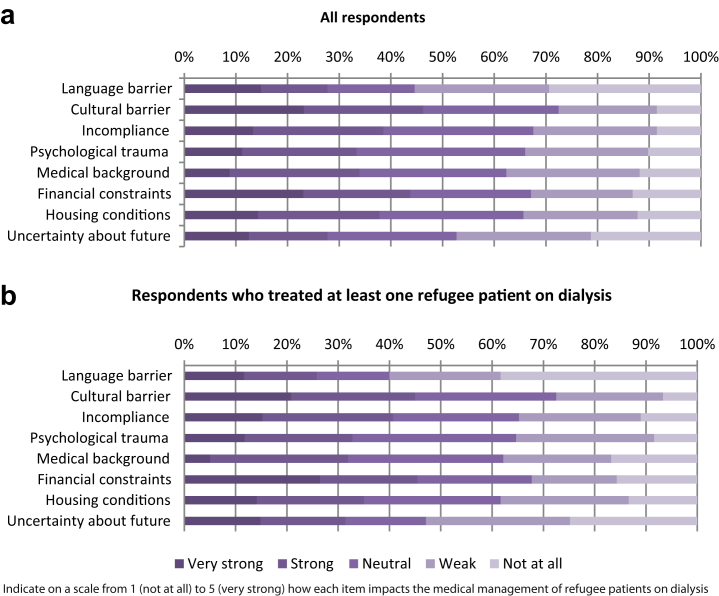

Financial constraints and cultural barriers seemed to have the greatest impact on the perceived adequacy of medical management of refugee patients, followed by concerns about housing. Responses were similar between centers that treated refugees and those which did not. Remarkably, language was only reported as having an impact on care by 25% of respondents (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Factors affecting medical care of refugees. (a) All respondents; (b) respondents treating more than 1 refugee patient.

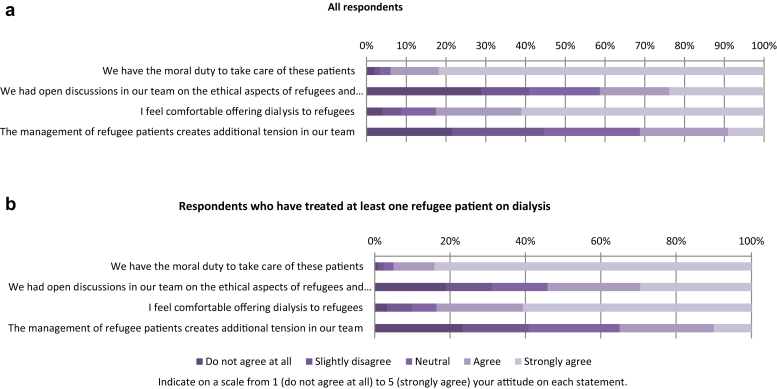

Attitudes of nephrologists to refugee patients on dialysis

Most respondents agreed that we have a moral duty to provide dialysis to refugee patients who need it (Figure 4). About 30% of respondents agreed that the ethical consequences of whether or not we should take care of these patients were openly discussed in their team. A comparable number indicated that managing these patients created some tension in the team. These opinions were not strikingly different between centers that treated refugee patients and centers that did not. Interestingly, in centers that had treated ≥1 refugee, tension was lower in teams where the ethical consequences were openly discussed (25%) compared with teams where they were not openly discussed (50%).

Figure 4.

Personal opinions on the following statements. (a) All respondents; (b) respondents treating more than 1 refugee patient.

Organizational aspects

Of the 49 invited ERA-EDTA national societies, 19 responded to the survey (the nephrological societies of Albania, Austria, Belgium [Flemish- and French-speaking], Bosnia–Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, the Czech Republic, Israel, Kosovo, Lithuania, Macedonia, Montenegro, Poland, Serbia, Slovenia, Spain, and Switzerland). National presidents reported that refugees were officially accepted for dialysis (n = 8) or accepted in restricted numbers for dialysis (n = 7) by their country. The remainder stated that “no official requests to accept refugees” had been made (n = 2), or that “refugees were only passing through” (n = 2). Only 5 countries initiated specific actions related to the management of refugees with ESKD. These actions focused on the special needs of children (n = 1), the options of living donation (n = 1), and establishing the diagnosis of the underlying renal disease (n = 3). Only 12 national societies considered there was a role for ERA-EDTA to set up a program to help deal with the problem of refugees in need for renal replacement therapy, and only 2 actually had an ongoing collaboration in this regard with other societies. Some national societies took initiatives of their own: communication to nephrological services in the country (n = 2), or initiatives for patients who had undergone a transplantation (n = 1). Most national presidents indicated that initiatives by international nephrological societies through special communications would be welcome, but no further suggestions were made in the open-text response field.

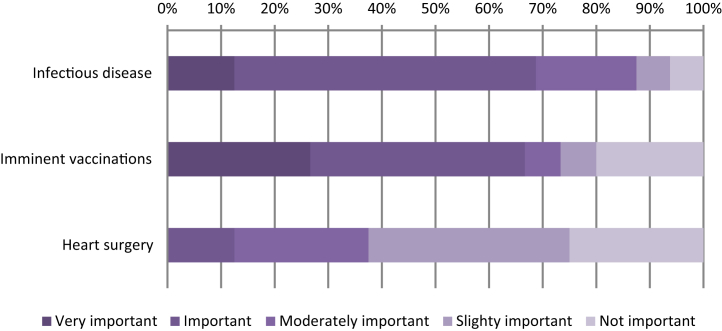

Risks of infectious disease, need for vaccination, and need for cardiovascular interventions were reported to be general priorities in the medical management of refugees (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

What are the potential concerns for the medical management of refugee patients on dialysis?

Discussion

Our results show that refugee patients represent about 1.5% of the dialysis population. However, distribution is skewed and some centers have been confronted with a substantial number of patients. There is a lack of information and policies on how to handle refugee patients. One-quarter of respondents did not know how dialysis for refugees was paid for. Most respondents considered that we have a moral duty to take care of these patients. This topic seems not to have been discussed openly in all teams involved, and this may create tensions within teams.

The surveys show that refugees trying to reach Europe include patients who have ESKD and a need for long-term dialysis. The humanitarian and ethical consequences of such a situation are underestimated. Patients on dialysis who decide to flee their country are at high risk of medical complications and death if they are not offered dialysis support. Up to one-quarter of nephrologists are not aware of reimbursement rules. This lack of knowledge might affect acceptance or refusal of individual patients for treatment and might endanger the vulnerable medical, social, and financial status of the refugees.6

Governments should develop policies and regulations on management of refugee patients on dialysis. This would avoid governments declaring they accept refugees but not funding their treatment, putting health care workers in ethically difficult positions. Nephrological societies should provide official information to members about rules on reimbursement for this treatment in their region.

Clear political decisions avoid individual nephrologists having to decide whether to accept an individual refugee patient for dialysis, a situation that is ethically not acceptable. Nephrologists have a responsibility toward individual patients but the political community at national, regional, as well as European Community level has a responsibility toward its population. Open and transparent debate should lead them to provide guidance and the financial and logistical means to act accordingly.7 According to the United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) Universal Declaration on Bioethics and Human Rights,8 refugees should be provided medical assistance, and countries that have signed this convention should act accordingly or openly declare that they dismiss this convention.7

The number of refugees varies considerably among countries and regions. Our data show that refugees represent about 1.5% of the dialysis population within wider Europe.

Dialysis centers near refugee camps might become overwhelmed by the number of refugees, and some regions or cities might be more popular destinations than others. We found indeed that the distribution of patients was strongly skewed. A uniform Europe-wide strategy on relocation of these patients would help to ensure an equitable burden of sustainable nephrology care.6, 9 Such a strategy should be based on objective information including data on patients on dialysis traveling to other countries, and dialysis capacity within affected countries. In war zones, local dialysis as well a medical infrastructure at large might have become unavailable,10 forcing patients on dialysis to seek refuge elsewhere; this creates a refugee status because of dialysis need. Alternatively, even in nonwar zones, some patients might flee their region because of restricted medical options. The ethical approaches to these distinct situations are different. Relevant epidemiologic data are therefore crucial for fair distribution of resources, and the nephrological community must organize registration of refugees in need of nephrological care. This need for research, necessary to accurately inform the public and the political world, is on the European Union’s political agenda.11

The need to support refugees with chronic diseases challenges the medical community,12 but health is only one of the many problems facing refugees.9 In Yemen, where according to our survey, there is a huge influx of refugee patients on dialysis, the United Nations International Children's Emergency Fund (UNICEF) estimates that 1.3 million children younger than 5 years have acute malnutrition, the supply of water and fuel is problematic, and electricity is often not available.13 Chronic diseases such as kidney disease impose substantial financial pressure, but are only part of the health problems of refugees. Poor hygiene, lack of sanitation, and exposure to disease vectors make fertile ground for epidemics. Measles for example has been a particular concern in Yemen, with a vaccination coverage for measles this year at about only 54% (compared with 75% last year).13, 14

There is little disagreement that we should take responsibility for managing acute illnesses affecting refugees. Most of these illnesses are managed by non-governmental organizations (NGOs), which have better trained workers and more expertise for managing acute, disaster-type situations. NGOs are self-funded, so their medical work with refugees does not interfere with funding of medical care for domestic residents. The close collaboration between RDRTF/ISN and Médicins Sans Frontières for the management of crush victims after earthquakes is a good example of NGO functionality in acute disaster setting.15

When specific and expensive technical expertise is mandatory, such as for ESKD, the financial and technical resources of NGOs are insufficient, and for these ailments, refugees depend on the existing health care structures. Some of this high-level care is not freely available in the country of origin, whereas in the receiving country, it already causes a disproportionate burden on the health care budget. A large influx of refugees may jeopardize access to optimal care for local people (who fund the health system), contravening the solidarity principle. However, in our survey, the burden of refugees was limited to only 1.5% of the existing dialysis population, an increase that should be logistically and financially manageable. A “generous” approach might attract people in need of dialysis from places where it is not sufficiently available. In this era of social media it might attract those with questionable refugee status from countries without fair solidarity based access to health care (medical restriction refugee). Import of nonlocal microorganisms16 and the observed increased risk of a disadvantaged refugee population to develop noncommunicable diseases can further increase demand on health care systems in host countries. Transparent political decisions will assist the medical community by defining who should or should not be offered dialysis in these circumstances.

Half the responding centers (57.5%) wait-listed refugees for renal (cadaveric) transplantation when they could legally stay in the country. A minority (16%) of centers never wait-list refugee patients, or only accept them for living donation when they bring a live donor and pay for the procedure (9.1%). Both policies pose ethical problems. There is currently a donor shortage, so although transplantation is financially the cheapest solution, it is at the expense of transplantation opportunities for the local population. Countries of origin almost never contribute to the donor pool, again violating the solidarity principle. However, not accepting these patients to a wait-list would be a signal they are considered “second class” citizens. Accepting living donations risks inadvertent encouragement of organ trafficking unless proper processes are in place to ensure proof of a familial tie between donor and recipient.

Cultural, rather than linguistic, differences were considered to be problematic in the medical management of refugee patients. Translation helps to overcome language differences, but poses financial and logistical problems.12 Even more importantly, a treating team may be unaware of cultural differences (e.g., different beliefs about health and disease, altered perceptions and priorities after displacement, and distrust of strangers), creating substantial misunderstandings that can jeopardize treatment and frustrate health workers.6

Strengths and limitations

Limitations of our survey include that it was a voluntary online survey, with invitations sent by e-mail. It is likely that some e-mail addresses in our database are invalid, so we could not accurately assess response rates. Voluntary surveys risk selection bias, with only people with experiences at the extremes of the spectrum replying. A strength is that the survey has tried to involve nephrologists from 2 nephrology societies with a large membership in Europe.

This survey is the first to focus on a population of refugees with ESKD. Although ESKD is a specific chronic condition, it is representative for many other chronic conditions for which treatment imposes a high financial burden on societies. Therefore, the results and considerations of this paper can maybe not be generalized to many other comparable chronic conditions present in refugee patients.

In conclusion, the ever-shifting nature of international politics means that the nephrological community must anticipate global crises. The Ebola crisis has shown that infectious diseases can pose huge challenges to the international nephrological community. Already in 1993, it was predicted that refugee crises larger than the current one are likely to occur with increasing frequency in the future because of the growing world population, political frictions, and the increasing impact of wars and disasters, especially on destitute populations.17 Such crises pose ethical and health care–related problems.

The international nephrological community must now decide how it can provide care for patients with kidney disease in conditions currently unfamiliar to us. It is clear that in our increasingly connected world, every problem can have a butterfly effect and substantially affect nephrology patients on the other side of the globe.

Materials and Methods

We conducted 2 surveys, using the United Nations definition of a refugee as “a person who, due to well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion is outside the country of his nationality, and is unable to, or owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country irrespective of being legally or not in that country and irrespective of his/her social security or financial status.”18

We used a web-based tool (SurveyMonkey) to invite all ISN members to participate in an anonymous survey (see Supplementary Appendix S1). This survey focused on individual experiences of individual centers and nephrologists in the preceding 4 months. The survey was translated into local languages to enhance acceptance. Internet protocol addresses were monitored to ensure that each center contributed only once to the survey. We explored the management of refugees with ESKD using closed questions for quantitative and descriptive data and explored qualitative opinions using a 5-point Likert scale. Responses were automatically retrieved into an Excel spreadsheet (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA), and we performed statistical analysis using SPSS (version 22; IBM, Armonk, NY) and show results as percentages or absolute numbers.

Another SurveyMonkey survey was sent to the presidents of the 49 national societies of ERA-EDTA (see Supplementary Appendix S2). The format was quantitative questions with open-text fields for additional information. Answers were collected in an Excel spreadsheet and descriptive statistics were produced.

Disclosure

WVB declared lecture fees from Fresenius MC, Baxter Healthcare SA, Gambro, and Leo Pharma. AW declared speakers fees from Fresenius, Pharmacosmos, Amgen, and Roche. RK declared lecture fees from Baxter Healthcare SA. ER declared speakers fees from Alexion. DH declared lecture fees from Roche Myanmar. All the other authors declared no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

The authors and their respective societies are very grateful for the indispensable managerial assistance of Arianne Brusselmans (ISN) and Monica Fontana (ERA-EDTA) in setting up the surveys, and Olivia Wroth (olivia@surperscriptwriting.com.au), for script-editing the paper.

This paper was produced through a collaboration of ISN and ERA-EDTA. No additional funding was obtained.

The corresponding author had full access to the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Footnotes

Appendix S1. Survey of the International Society of Nephrology (ISN).

Appendix S2. Open questions to the presidents of the national societies of European Renal Association/European Dialysis and Transplant Association (ERA-EDTA).

Supplementary material is linked to the online version of the paper at www.kisupplements.org.

Supplementary Material

Survey of the International Society of Nephrology (ISN).

Open questions to the presidents of the national societies of European Renal Association/European Dialysis and Transplant Association (ERA-EDTA).

References

- 1.Alisic E., Letschert R.M. Fresh eyes on the European refugee crisis. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2016;7:31847. doi: 10.3402/ejpt.v7.31847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.el-Reshaid K., Johny K.V., Georgous M. The impact of Iraqi occupation on end-stage renal disease patients in Kuwait, 1990–1991. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1993;8:7–10. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.ndt.a092276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Otoukesh S., Mojtahedzadeh M., Cooper C.J. Lessons from the profile of kidney diseases among Afghan refugees. Med Sci Monit. 2014;20:1621–1627. doi: 10.12659/MSM.890958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Doocy S., Lyles E., Roberton T. Prevalence and care-seeking for chronic diseases among Syrian refugees in Jordan. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:1097. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-2429-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.White J.S., Hamad R., Li X. Long-term effects of neighbourhood deprivation on diabetes risk: quasi-experimental evidence from a refugee dispersal policy in Sweden. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2016;4:517–524. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(16)30009-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Byrd B. High-quality health care for resettled refugees: a sustainable model. Available at: http://healthaffairs.org/blog/2016/05/04/high-quality-health-care-for-resettled-refugees-a-sustainable-model/. Accessed October 10, 2016.

- 7.Oberoi P, Sotomayor J, Pace P, et al. International migration, health and human rights. Available at: http://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Issues/Migration/WHO_IOM_UNOHCHRPublication.pdf. Accessed October 10, 2016.

- 8.UNESCO. Universal declaration on bioethics and human rights. Available at: http://www.unesco.org/new/en/social-and-human-sciences/themes/bioethics/bioethics-and-human-rights/. Accessed October 10, 2016.

- 9.Brannan S., Campbell R., Davies M. The Mediterranean refugee crisis: ethics, international law and migrant health. J Med Ethics. 2016;42:269–270. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Devi S. Syria's health crisis: 5 years on. Lancet. 2016;387:1042–1043. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00690-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boswell C. Understanding and tackling the migration challenge: the role of research. Available at: http://ec.europa.eu/research/social-sciences/pdf/other_pubs/migration_conference_report_2016.pdf. Accessed October 10, 2016.

- 12.Hunter P. The refugee crisis challenges national health care systems: countries accepting large numbers of refugees are struggling to meet their health care needs, which range from infectious to chronic diseases to mental illnesses. EMBO Rep. 2016;17:492–495. doi: 10.15252/embr.201642171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burki T. Yemen health situation “moving from a crisis to a disaster.”. Lancet. 2015;385:1609. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60779-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burki T. Yemen’s neglected health and humanitarian crisis. Lancet. 2016;387:734–735. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(16)00389-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vanholder R., Gibney N., Luyckx V.A., for the Renal Disaster Relief Task Force Renal Disaster Relief Task Force in Haiti earthquake. Lancet. 2010;375:1162–1163. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60513-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kupferschmidt K. Infectious diseases: refugee crisis brings new health challenges. Science. 2016;352:391–392. doi: 10.1126/science.352.6284.391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cameron J.S. The effect of armed conflict on dialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1993;8:6. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.ndt.a092273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.UNHCR. Who is a refugee? Available at: http://www.unrefugees.org/what-is-a-refugee/. Accessed May 30, 2016.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Survey of the International Society of Nephrology (ISN).

Open questions to the presidents of the national societies of European Renal Association/European Dialysis and Transplant Association (ERA-EDTA).