Abstract

The pharmacological properties and physiological roles of the type I receptor sortilin, also called neurotensin receptor-3, are various and complex. Sortilin is involved in important biological functions from neurotensin and pro-Nerve Growth Factor signaling in the central nervous system to regulation of glucose and lipid homeostasis in the periphery. The peripheral functions of sortilin being less extensively addressed, the focus of the current review is to discuss recent works describing sortilin-induced molecular mechanisms regulating blood glucose homeostasis and insulin signaling. Thus, an overview of several roles ascribed to sortilin in diabetes and other metabolic diseases are presented. Investigations on crucial cellular pathways involved in the protective effect of sortilin receptor on beta cells, including recent discoveries about regulation of cell fate, are also detailed. In addition, we provide a special focus on insulin secretion regulation involving complexes between sortilin and neurotensin receptors. The last section comments on the future research areas which should be developed to address the function of new effectors of the sortilin system in the endocrine apparatus.

Keywords: diabetes, receptor, pharmacology, signaling, physiology

Sortilin Receptor

The protein sortilin, composed of 833 amino acids in human, is a high affinity receptor (Kd ≈ 0.3 nM) for NT (Mazella et al., 1989, 1998). It was first identified in 1997 as a receptor-associated protein (RAP) (Petersen et al., 1997). Sortilin belongs to the Vps10p family of type I receptors, with SorLA and SorCS1-3 receptors (Jacobsen et al., 1996; Hermey et al., 1999). The members of this family are characterized by a single transmembrane domain framed by an extracellular domain rich in cysteines (comparable to that of the Vps10p trivalent vacuolar protein of yeast), and a short intracellular end (C-terminal domain) involved in its internalization (Petersen et al., 1996, 1997; Mazella et al., 1998). Sortilin is widely expressed in the central nervous system, particularly in the hippocampus, dentate gyrus and cerebral cortex (Hermans-Borgmeyer et al., 1999). It is also present in the spinal cord, skeletal muscle, testes, heart, placenta, pancreas, prostate, and small intestine (Petersen et al., 1997). Sortilin distribution in the cell is highly regulated. While it is very poorly present at the PM (5–10%), the bulk of the protein localizes in intracellular compartments (vesicles and trans-golgi network) (Morris et al., 1998). If three NT receptors (NTSRs) NTSR1, NTSR2 and NTSR3 (or sortilin) mediate the effects of NT, the NTSR1 and NTSR2 receptors belong to the large GPCR (G Protein-Coupled Receptor) family in contrast to sortilin that is a sorting receptor with a single transmembrane domain (Mazella et al., 1989, 1998).

Sortilin is synthesized in an immature form, prosortilin. Prosortilin convertion to its mature receptor occurs in the Golgi apparatus through removal of its N terminal domain by the pro-convertase furin. This leads to the release of a peptide of 44 amino acids (SDP for sortilin derived propeptide: Gln1-Arg44, also known as PE). While such maturation process is a general mechanism to control receptor or enzyme activation, in the present case, the canonical furin cleavage leads also to the release of a new active peptide. Indeed, SDP binds to mature sortilin and TREK-1 channel with a high affinity (Kd∼5nM) (Munck Petersen et al., 1999; Mazella et al., 2010). Several groups have also largely documented that sortilin is a co-receptor of the prodomain of proNGF and proBDNF (Nykjaer et al., 2004; Teng et al., 2005; Arnett et al., 2007).

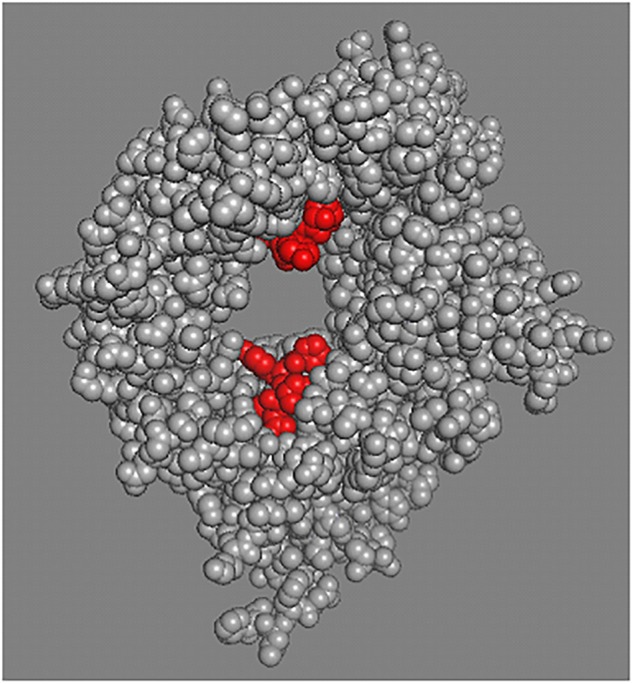

Even though the binding properties of each sortilin ligand have not been clearly unraveled, data suggest that binding sites are similar for most of them (Quistgaard et al., 2009). As illustrated by Figure 1, NT (in red) binds to sortilin (in gray) in a tunnel of a ten-bladed β-propeller domain. The structural properties of sortilin suggests that NT is completely contained inside the tunnel of the β-propeller, firmly bound by its C-terminus and further attached by its N-terminal part at a low affinity site on the opposite side of the tunnel (PDB: 3F6K).

FIGURE 1.

Sortilin structural model. Sortilin complexed with NT structural model PDB 3F6K. The extracellular domain of sortilin, receptor for NT was crystallized and the tridimensional structure at 2A resolution was determined. Peptides binding (two sites) relates to the restricted space inside the tunnel of the b-propeller (Quistgaard et al., 2009, 2014). Sortilin is shown in gray and NT in red.

Sortilin is Associated to Distincts NTSRs to Modulate NT-Mediated Endocrine Cell Functions

Physiological studies performed during the first years following the discovery of NT in 1973, revealed some interesting results concerning the potential involvement of the peptide in glucose homeostasis and lipid absorption. Indeed in human, NT is released in the blood circulation after a meal, and lipid absorption stimulates NT release from the rat small intestine (Leeman and Carraway, 1982). In addition, NT is released from pancreas in STZ-diabetic rats (Berelowitz and Frohman, 1982) and is co-localized with glucagon in the endocrine human fetal pancreas (Portela-Gomes et al., 1999). Interestingly, NT exerts a dual effect on the rat endocrine pancreas: at low glucose concentration, the peptide stimulates insulin and glucagon release whereas at high glucose concentration, it has the opposite effect (Dolais-Kitabgi et al., 1979). Furthermore, NT administration increases pancreatic weight and DNA content indicating a prominent proliferative effect of the peptide on pancreatic cells (Feurle et al., 1987; Wood et al., 1988).

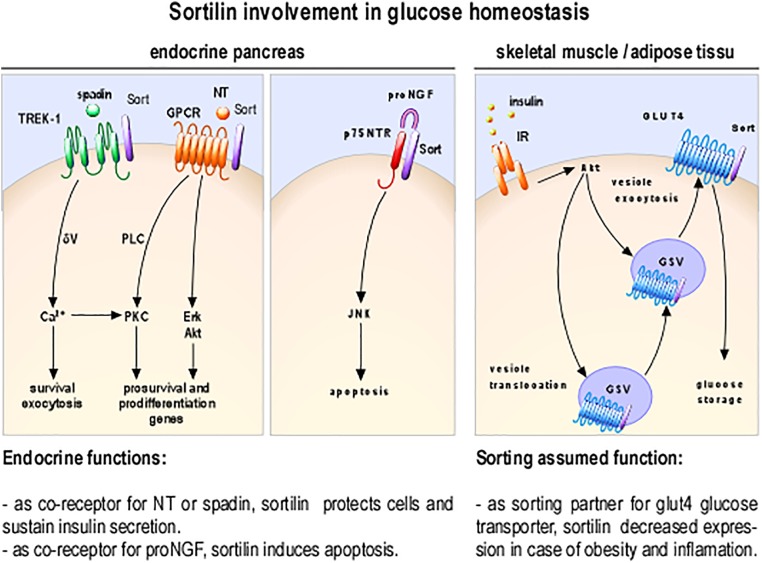

As involvement of NT in glucose homeostasis become clearer, understanding the mechanisms of its action on insulin-secreting cells is crucial, especially because RT-PCR and Western blot analyses have demonstrated that all NTSRs are expressed in rat and mouse islets and in insulin-secreting beta cell lines (Coppola et al., 2008; Beraud-Dufour et al., 2009). Functionally, NT can modulate various biological responses both in insulinoma derived cell lines and in isolated pancreatic islets (Khan et al., 2017; Figure 2) suggesting the possibility of differential activation pathways by NT. In this area, some studies indicated that the PKC proteins play a key role in the direct effect of NT on insulin secretion from beta cells (Beraud-Dufour et al., 2010; Khan et al., 2017).

FIGURE 2.

Cellular and molecular processes involving sortilin as receptor or co-receptor. Sortilin (in purple) as NT regulation via the complex of GPCR/sortilin; the complex p75NTR/sortilin promotes apoptosis inducing JNK dependent pathway, spadin inhibition of TREK-1 K+ currents potentiate insulin secretion and as sorting partner is a part of the machinery necessary for insulin dependent translocation of GLUT4 storage vesicles (GSV); insulin receptor (IR).

Clinical data, by showing that circulating NT levels are increased in human diabetes and obesity (Melander et al., 2012; Chowdhury et al., 2016) identified NT regulation as a promising therapeutic target in these most prevalent and challenging health conditions. This was correlated by in vivo studies showing that NT (NT-/-) and sortilin KO mice (Sort1-/-) share some common phenotypes, especially by protecting from obesity, hepatic steatosis, and metabolic disorders. Indeed, sortilin deficiency induces a beneficial metabolic phenotype in liver and adipose tissue against high fat diet (Rabinowich et al., 2015).

Furthermore, studies on double knockout mice for the low-density lipoprotein receptor (Ldlr-/-, an atherosclerosis model) and sortilin (Sort1-/-) have confirmed the previous observations showing that sortilin is crucial for lipid homeostasis by suppressing intestinal cholesterol absorption mostly in female mice (Hagita et al., 2018). It is important to note that some contradictory results were obtained using another so-called sort1-/- model (Li et al., 2017a). It was observed that suppression of sortilin gene does not affect diet-induced obesity and glucose uptake from adipose tissue and skeletal muscle. A closer look of both Sort1-/- model mice used showed that the first studies were performed using a mouse in which the exon 14th of the sortilin gene was deleted, leading to the expression of a soluble sortilin receptor (Rabinowich et al., 2015; Hagita et al., 2018).

The other deletion was done on the second exon deleting almost all of the sortilin protein (Li et al., 2017a). Similarly to the first Sort1-/- model described (Rabinowich et al., 2015; Hagita et al., 2018), NT-deficient mice are resistant to DIO, hepatic steatosis and insulin resistance (Li et al., 2016). In order to explain such differences between sortilin deficient mice models, it is possible to argue that the expression of a circulating soluble form of the receptor, is able to buffer the NT in the blood stream and also potentially the other sortilin-interacting peptides (Quistgaard et al., 2014). Thus, we can postulate that the truncated receptor depletes circulating NT, similarly to a NT KO- phenotype. In addition, the metabolic improved phenotype (protection from obesity, hepatic steatosis, and insulin resistance) observed in NT-deficiency suggests an involvement of sortilin in NT-regulation of glucose homeostasis.

In correlation with this postulate, it has been shown that NT has a potent anti-apoptotic effect against IL-1bβ or staurosporine (Coppola et al., 2008). This protective effect of NT is mediated by sortilin in combination with NTSR2 (Beraud-Dufour et al., 2009). Sortilin as a co-receptor with NTSR2 is necessary for the anti-apoptotic NT function and also for the peptide modulation of insulin secretion (Beraud-Dufour et al., 2010). This receptor heterodimer exerts a protective effect against apoptosis by stimulating PI-3 kinase activity which in turn phosphorylates Akt (Coppola et al., 2008). Importantly, recent works performed in rodent and human beta cells, showed that NT was also produced inside the islets and regulates adaptation to environmental stress (Khan et al., 2017).

These results, all together, underline that sortilin, as receptor or co-receptor for NT, may have a dual and beneficial role: protecting endocrine cells from stress induced apoptosis and/or controlling lipid absorption from the intestine.

Sortilin, a Sorting Protein for Glucose Transporter GLUT4, is a Key Modulator of Metabolism

As largely documented, sortilin and the glucose transporter GLUT4 are co-expressed in differentiated adipocytes and myotubes (Figure 1; Bogan and Kandror, 2010), and are necessary for glucose storage. Fine-tuning of the expression level of both proteins is crucial in order to maintain insulin mediated glucose transport inside the cells (Figure 2). For example, formation of Glut4 storage vesicles in adipocytes and skeletal muscle cells correlates with the expression of sortilin (Ariga et al., 2008; Shi et al., 2008; Ariga et al., 2017). In addition, insulin dependent translocation of Glut4 is clearly correlated with the presence of sortilin in adipocytes (Huang et al., 2013). It has been hypothesized that defect in peripheral glucose transport, related to insulin resistance observed in obesity and diabetes, could be correlated in vivo, with modification of the expression level of sortilin (Kaddai et al., 2009).

In addition, sortilin expression is decreased in several physiopathological conditions such as obesity and this repression is TNF-alpha dependent. Interestingly, a link between chronic low-grade inflammation, sortilin expression and insulin resistance has been postulated (Kaddai et al., 2009). Indeed, sortilin expression is differently altered in insulin resistance models induced by TNF-alpha or dexamethasone treatments. In presence of TNF-alpha the expression of sortilin is drastically decreased and can be associated with insulin resistance; on the opposite dexamethasone dependent insulin resistance is not accompanied by sortilin downregulation (Hivelin et al., 2017; Li et al., 2017b). TNF-alpha combined with hypoxia was most able to mimic in vivo DIO-induced adipose insulin resistance (Lo et al., 2013). Also, sortilin gene expression is decreased in white adipose tissue of obese mice when PI3K/AKT signaling is inhibited (Li et al., 2017b).

TNF-alpha and dexamethasone are inducers of insulin resistance, respectively inhibiting insulin receptor tyrosine kinase activity (Hotamisligil et al., 1996; Rui et al., 2001) or inducing whole body insulin resistance without affecting GLUT4 translocation machinery (Qi et al., 2004). All together these results show that down regulation of sortilin expression may be one of the events leading to insulin resistance.

Sortilin, Acting on TREK-1 Channel, Regulates Cell Excitability

With respect to insulin resistance and secretion, potassium permeability by controlling the beta cell membrane potential regulates insulin secretion. Indeed, insulin granule exocytosis is induced by membrane depolarization that is a direct consequence of the inhibition of ATP dependent potassium channels by the increased ATP production from glucose metabolism. Other types of K+ channels including TREK-1, a two-pore-domain (K2P) background potassium channel are known to be involved in the control of the resting membrane potential and the regulation of depolarizing stimulus (Kim and Kang, 2015).

This is part of the K2P(s) general properties. Background K+ outward currents could adjust the membrane potential, low hyperpolarization or depolarization (Kim, 2005). Therefore, interfering with TREK-1 plasma conductance could play an important role in the electrophysiology of insulin secretion. TREK-1 channel could be thereby, a potential target for pharmacological agents designed to modulate this secretion. This has to be underlined, as we have recently reported that the TREK-1 channel is inhibited by SDP (propeptide: Gln1-Arg44), as well as by its shorter analog spadin (Mazella et al., 2010).

Since structure function studies determined that SDP region Gln17-Arg28 was as efficient in binding affinity (Kd∼5nM) than the entire peptide, we generated a TREK-1 inhibitory peptide called spadin (Sortilin Peptide AntiDepressive in) which has amino acids 17–28 preceded by sequence 12–16 (APLRP) to maintain conformational stress (Mazella et al., 2010). Results clearly demonstrated the capacity of spadin and SDP for blocking TREK-1 currents (Mazella et al., 2010). The bioactivity of SDP is of interest as a specific SDP dosing assay revealed that its circulating level is of significant concentrations (10 nM) in the mouse serum (Mazella et al., 2010). In addition, TREK-1 and sortilin are co-expressed in pancreatic islets, only in aα and β cells. At a cellular level TREK-1 and sortilin co-localize in intracellular compartments (Hivelin et al., 2016). Therefore we explored the inhibitory effects of spadin on endogenous TREK-1 current in β pancreatic cells (Hivelin et al., 2016). We could observe changes in resting membrane potential in MIN6B1 pancreatic beta cell line incubated in the presence of 10nM spadin. The mild depolarization observed (delta = 12.84 mV), although not sufficient to induce insulin secretion by itself, potentiates the effect of secretagogues such as 16.7 mM glucose or 30 mM KCl (Hivelin et al., 2016). This PM depolarization likely facilitates the exocytosis process through the enhancement of intracellular calcium concentration. Moreover, we reported that during in vivo IPGTT experiments, glucose level is always lower in mice treated with spadin, suggesting a direct action of spadin on glycaemia (Hivelin et al., 2016).

Interestingly most of the consequences of spadin inhibitory action on TREK-1 channel were primarily documented in neurons, and among them some interesting features could be relevant for beta cell mass retention. Spadin as specific inhibitor for TREK-1 channel currents induces survival pathways, such as Akt and Erk pathways in primary cultured neurons (Devader et al., 2015). Accordingly, this was associated with an anti-apoptotic effect, associated with an increase of the phosphorylation of CREB. In vivo, spadin induces a rapid onset of neurogenesis (Mazella et al., 2010). Therefore, it is tempting to postulate that such protective and modulation of the proliferation pathways (Abdelli et al., 2009; Beeler et al., 2009), could be observed in endocrine pancreatic cells that shear common traits with neurons. These traits are required for insulin secretion (Abderrahmani et al., 2004a,b).

Sortilin and proNGF Partners in Death Fate: Sortilin Dependent Apoptosis

Since several years, a link between NGF and diabetes has been showed. For example, the NGF/proNGF expression ratio is decreased in the brain of diabetic rats (Soligo et al., 2015) and in STZ-induced diabetic rats (Sposato et al., 2007). Furthermore, these rats present an up-regulation of the p75NTR expression in the pancreas (Sposato et al., 2007), suggesting a role of this receptor in the higher apoptosis rate observed in the endocrine pancreas of these animals. The role of the sortilin/p75NTR receptor complex in the induction of death described in neurons (Nykjaer et al., 2004) has also been identified in lymphocytes (Rogers et al., 2010). It has been demonstrated that proNGF, when TrkA expression decreases, switches PC12 cells from growth to apoptosis (Ioannou and Fahnestock, 2017). Interestingly, NGF receptors (p75NTR and TrkA) are expressed in human and rodent pancreatic islets (Miralles et al., 1998; Rosenbaum et al., 1998; Pingitore et al., 2016) and NGF is expressed and secreted by adult beta cells, suggesting an autocrine effect (Rosenbaum et al., 1998).Thus, it is tempting to postulate that a decreased maturation of proNGF, as observed in the brain of diabetic rat (Soligo et al., 2015), could represent a major cause of beta cell apoptosis. In that perspective, it would be of great importance to carefully analyze the role of sortilin, TrkA, p75NTR, and NGF as pro- or anti-apoptotic promoters in beta cells.

Conclusion/Perspectives

The reviewing of the literature undoubtedly identifies the high affinity NT receptor, sortilin, as involved in key regulatory mechanisms of glucose homeostasis. Although it is generally accepted that the results obtained on cells from Langerhans islets are preferable to any other, most of the data showing a specific role of sortilin in beta cell comes from tumor-derived cell lines Nevertheless, work on tumor lines, that retain much of the properties of differentiated cells (Merglen et al., 2004) is useful in understanding the role of sortilin. We cannot, at this stage, give a complete and perfectly defined role for sortilin in beta cell. However, it is possible to say, with caution, that sortilin could play a role in survival and function maintenance of beta cell, when associated with an NT receptor, or pro-apoptotic role when associated with p75NTR (Figure 2). These seemingly contradictory functions are not informed so far by in vivo studies emphasizing the usefulness of work on the endocrine pancreas of sort-/- mice.

In addition to the various drugs interfering with insulin secretion, design of new drugs targeting sortilin should be considered. Antagonism against proneurotrophin action, for example, could represent a possible pharmacological approach for beta cell mass preservation, which is regarded as crucial in the prevention and treatment of type 2 diabetes. Demonstration of the implication of K+ outward currents as target for insulin exocytosis potentiation by spadin is crucial for new pharmacological perspectives. However, the “druggability” of the sortilin-underlying pathways is complicated because of multiplicity of sortilin intricated functions and its large-scale inhibition could have deleterious effects on general metabolism. Further research is then required to provide evidence of the effectiveness and feasibility of sortilin pathways targeting for therapeutic intervention in obesity and type 2 diabetes.

Author Contributions

NB and SB-D shared first co-authorship. All authors participated in writing the article.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Franck Aguila for art work. We thank all their past and present team members and collaborators who have contributed to the data discussed in the review. We are grateful to Dr. Catherine Heurteaux and Dr. Romain Gautier for helpful discussions. We also thank the French Government for the “Investments for the Future” LABEX ICST # ANR-11 LABX 0015.

Abbreviations

- AKT

RAC-alpha serine/threonine-protein kinase

- BDNF

brain derived neurotrophic factor

- DIO

diet induced obesity

- ERK

extracellular signal-regulated kinases

- GPCR

G protein coupled receptor

- IPGTT

intra peritoneal glucose tolerance test

- K2P

two-pore-domain background potassium channel

- Ldlr

low-density lipoprotein receptor

- NGF

nerve growth factor

- NT

neurotensin

- NTSR2

neurotensin receptor-2

- NTSR3

neurotensin receptor-3

- p75NTR

neurotrophin receptor of 75 kDa

- PKC

protein kinase C

- PM

plasma membrane

- STZ

streptozotocin

Footnotes

Funding. This work was supported by the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, a grant from the Société Francophone du Diabète (SFD 2011) to TC.

References

- Abdelli S., Puyal J., Bielmann C., Buchillier V., Abderrahmani A., Clarke P. G., et al. (2009). JNK3 is abundant in insulin-secreting cells and protects against cytokine-induced apoptosis. Diabetologia 52 1871–1880. 10.1007/s00125-009-1431-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abderrahmani A., Niederhauser G., Plaisance V., Haefliger J. A., Regazzi R., Waeber G. (2004a). Neuronal traits are required for glucose-induced insulin secretion. FEBS Lett. 565 133–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abderrahmani A., Niederhauser G., Plaisance V., Roehrich M. E., Lenain V., Coppola T., et al. (2004b). Complexin I regulates glucose-induced secretion in pancreatic beta-cells. J. Cell Sci. 117 2239–2247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ariga M., Nedachi T., Katagiri H., Kanzaki M. (2008). Functional role of sortilin in myogenesis and development of insulin-responsive glucose transport system in C2C12 myocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 283 10208–10220. 10.1074/jbc.M710604200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ariga M., Yoneyama Y., Fukushima T., Ishiuchi Y., Ishii T., Sato H., et al. (2017). Glucose deprivation attenuates sortilin levels in skeletal muscle cells. Endocr. J. 64 255–268. 10.1507/endocrj.EJ16-0319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett M. G., Ryals J. M., Wright D. E. (2007). Pro-NGF, sortilin, and p75NTR: potential mediators of injury-induced apoptosis in the mouse dorsal root ganglion. Brain Res. 1183 32–42. 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.09.051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beeler N., Riederer B. M., Waeber G., Abderrahmani A. (2009). Role of the JNK-interacting protein 1/islet brain 1 in cell degeneration in Alzheimer disease and diabetes. Brain Res. Bull. 80 274–281. 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2009.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beraud-Dufour S., Abderrahmani A., Noel J., Brau F., Waeber G., Mazella J., et al. (2010). Neurotensin is a regulator of insulin secretion in pancreatic beta-cells. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 42 1681–1688. 10.1016/j.biocel.2010.06.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beraud-Dufour S., Coppola T., Massa F., Mazella J. (2009). Neurotensin receptor-2 and -3 are crucial for the anti-apoptotic effect of neurotensin on pancreatic beta-TC3 cells. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 41 2398–2402. 10.1016/j.biocel.2009.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berelowitz M., Frohman L. A. (1982). The role of neurotensin in the regulation of carbohydrate metabolism and in diabetes. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 400 150–159. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1982.tb31566.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogan J. S., Kandror K. V. (2010). Biogenesis and regulation of insulin-responsive vesicles containing GLUT4. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 22 506–512. 10.1016/j.ceb.2010.03.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury S., Wang S., Dunai J., Kilpatrick R., Oestricker L. Z., Wallendorf M. J., et al. (2016). Hormonal responses to cholinergic input are different in humans with and without type 2 diabetes mellitus. PLoS One 11:e0156852. 10.1371/journal.pone.0156852 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coppola T., Beraud-Dufour S., Antoine A., Vincent J. P., Mazella J. (2008). Neurotensin protects pancreatic beta cells from apoptosis. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 40 2296–2302. 10.1016/j.biocel.2008.03.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devader C., Khayachi A., Veyssiere J., Moha Ou Maati H., Roulot M., Moreno S., et al. (2015). In vitro and in vivo regulation of synaptogenesis by the novel antidepressant spadin. Br. J. Pharmacol. 172 2604–2617. 10.1111/bph.13083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolais-Kitabgi J., Kitabgi P., Brazeau P., Freychet P. (1979). Effect of neurotensin on insulin, glucagon, and somatostatin release from isolated pancreatic islets. Endocrinology 105 256–260. 10.1210/endo-105-1-256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feurle G. E., Muller B., Rix E. (1987). Neurotensin induces hyperplasia of the pancreas and growth of the gastric antrum in rats. Gut 28(Suppl.) 19–23. 10.1136/gut.28.Suppl.19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagita S., Rogers M. A., Pham T., Wen J. R., Mlynarchik A. K., Aikawa M., et al. (2018). Transcriptional control of intestinal cholesterol absorption, adipose energy expenditure and lipid handling by sortilin. Sci. Rep. 8:9006. 10.1038/s41598-018-27416-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermans-Borgmeyer I., Hermey G., Nykjaer A., Schaller C. (1999). Expression of the 100-kDa neurotensin receptor sortilin during mouse embryonal development. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 65 216–219. 10.1016/S0169-328X(99)00022-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermey G., Riedel I. B., Hampe W., Schaller H. C., Hermans-Borgmeyer I. (1999). Identification and characterization of SorCS, a third member of a novel receptor family. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 266 347–351. 10.1006/bbrc.1999.1822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hivelin C., Beraud-Dufour S., Devader C., Abderrahmani A., Moreno S., Moha Ou Maati H., et al. (2016). Potentiation of calcium influx and insulin secretion in pancreatic beta cell by the specific TREK-1 blocker spadin. J. Diabetes Res. 2016 1–9. 10.1155/2016/3142175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hivelin C., Mazella J., Coppola T. (2017). Sortilin derived propeptide regulation during adipocyte differentiation and inflammation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 482 87–92. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.10.139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotamisligil G. S., Johnson R. S., Distel R. J., Ellis R., Papaioannou V. E., Spiegelman B. M. (1996). Uncoupling of obesity from insulin resistance through a targeted mutation in aP2, the adipocyte fatty acid binding protein. Science 274 1377–1379. 10.1126/science.274.5291.1377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang G., Buckler-Pena D., Nauta T., Singh M., Asmar A., Shi J., et al. (2013). Insulin responsiveness of glucose transporter 4 in 3T3-L1 cells depends on the presence of sortilin. Mol. Biol. Cell 24 3115–3122. 10.1091/mbc.E12-10-0765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ioannou M. S., Fahnestock M. (2017). ProNGF, but Not NGF, switches from neurotrophic to apoptotic activity in response to reductions in TrkA receptor levels. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 18:E599. 10.3390/ijms18030599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen L., Madsen P., Moestrup S. K., Lund A. H., Tommerup N., Nykjaer A., et al. (1996). Molecular characterization of a novel human hybrid-type receptor that binds the alpha2-macroglobulin receptor-associated protein. J. Biol. Chem. 271 31379–31383. 10.1074/jbc.271.49.31379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaddai V., Jager J., Gonzalez T., Najem-Lendom R., Bonnafous S., Tran A., et al. (2009). Involvement of TNF-alpha in abnormal adipocyte and muscle sortilin expression in obese mice and humans. Diabetologia 52 932–940. 10.1007/s00125-009-1273-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan D., Vasu S., Moffett R. C., Gault V. A., Flatt P. R., Irwin N. (2017). Locally produced xenin and the neurotensinergic system in pancreatic islet function and beta-cell survival. Biol. Chem. 399 79–92. 10.1515/hsz-2017-0136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D. (2005). Physiology and pharmacology of two-pore domain potassium channels. Curr. Pharm. Des. 11 2717–2736. 10.2174/1381612054546824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D., Kang D. (2015). Role of K2p channels in stimulus-secretion coupling. Pflugers Arch. 467 1001–1011. 10.1007/s00424-014-1663-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leeman S. E., Carraway R. E. (1982). Neurotensin: discovery, isolation, characterization, synthesis and possible physiological roles. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 400 1–16. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1982.tb31557.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Matye D. J., Wang Y., Li T. (2017a). Sortilin 1 knockout alters basal adipose glucose metabolism but not diet-induced obesity in mice. FEBS Lett. 591 1018–1028. 10.1002/1873-3468.12610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Wang Y., Matye D. J., Chavan H., Krishnamurthy P., Li F., et al. (2017b). Sortilin 1 modulates hepatic cholesterol lipotoxicity in mice via functional interaction with liver carboxylesterase 1. J. Biol. Chem. 292 146–160. 10.1074/jbc.M116.762005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Song J., Zaytseva Y. Y., Liu Y., Rychahou P., Jiang K., et al. (2016). An obligatory role for neurotensin in high-fat-diet-induced obesity. Nature 533 411–415. 10.1038/nature17662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo K. A., Labadorf A., Kennedy N. J., Han M. S., Yap Y. S., Matthews B., et al. (2013). Analysis of in vitro insulin-resistance models and their physiological relevance to in vivo diet-induced adipose insulin resistance. Cell Rep. 5 259–270. 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.08.039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazella J., Chabry J., Zsurger N., Vincent J. P. (1989). Purification of the neurotensin receptor from mouse brain by affinity chromatography. J. Biol. Chem. 264 5559–5563. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazella J., Petrault O., Lucas G., Deval E., Beraud-Dufour S., Gandin C., et al. (2010). Spadin, a sortilin-derived peptide, targeting rodent TREK-1 channels: a new concept in the antidepressant drug design. PLoS Biol. 8:e1000355. 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazella J., Zsurger N., Navarro V., Chabry J., Kaghad M., Caput D., et al. (1998). The 100-kDa neurotensin receptor is gp95/sortilin, a non-G-protein-coupled receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 273 26273–26276. 10.1074/jbc.273.41.26273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melander O., Maisel A. S., Almgren P., Manjer J., Belting M., Hedblad B., et al. (2012). Plasma proneurotensin and incidence of diabetes, cardiovascular disease, breast cancer, and mortality. JAMA 308 1469–1475. 10.1001/jama.2012.12998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merglen A., Theander S., Rubi B., Chaffard G., Wollheim C. B., Maechler P. (2004). Glucose sensitivity and metabolism-secretion coupling studied during two-year continuous culture in INS-1E insulinoma cells. Endocrinology 145 667–678. 10.1210/en.2003-1099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miralles F., Philippe P., Czernichow P., Scharfmann R. (1998). Expression of nerve growth factor and its high-affinity receptor Trk-A in the rat pancreas during embryonic and fetal life. J. Endocrinol. 156 431–439. 10.1677/joe.0.1560431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris N. J., Ross S. A., Lane W. S., Moestrup S. K., Petersen C. M., Keller S. R., et al. (1998). Sortilin is the major 110-kDa protein in GLUT4 vesicles from adipocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 273 3582–3587. 10.1074/jbc.273.6.3582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munck Petersen C., Nielsen M. S., Jacobsen C., Tauris J., Jacobsen L., Gliemann J., et al. (1999). Propeptide cleavage conditions sortilin/neurotensin receptor-3 for ligand binding. EMBO J. 18 595–604. 10.1093/emboj/18.3.595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nykjaer A., Lee R., Teng K. K., Jansen P., Madsen P., Nielsen M. S., et al. (2004). Sortilin is essential for proNGF-induced neuronal cell death. Nature 427 843–848. 10.1038/nature02319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen C. M., Ellgaard L., Nykjaer A., Vilhardt F., Vorum H., Thogersen H. C., et al. (1996). The receptor-associated protein (RAP) binds calmodulin and is phosphorylated by calmodulin-dependent kinase II. EMBO J. 15 4165–4173. 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1996.tb00791.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen C. M., Nielsen M. S., Nykjaer A., Jacobsen L., Tommerup N., Rasmussen H. H., et al. (1997). Molecular identification of a novel candidate sorting receptor purified from human brain by receptor-associated protein affinity chromatography. J. Biol. Chem. 272 3599–3605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pingitore A., Caroleo M. C., Cione E., Castanera Gonzalez R., Huang G. C., Persaud S. J. (2016). Fine tuning of insulin secretion by release of nerve growth factor from mouse and human islet beta-cells. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 436 23–32. 10.1016/j.mce.2016.07.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portela-Gomes G. M., Johansson H., Olding L., Grimelius L. (1999). Co-localization of neuroendocrine hormones in the human fetal pancreas. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 141 526–533. 10.1530/eje.0.1410526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi D., Pulinilkunnil T., An D., Ghosh S., Abrahani A., Pospisilik J. A., et al. (2004). Single-dose dexamethasone induces whole-body insulin resistance and alters both cardiac fatty acid and carbohydrate metabolism. Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 53 1790–1797. 10.2337/diabetes.53.7.1790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quistgaard E. M., Groftehauge M. K., Madsen P., Pallesen L. T., Christensen B., Sorensen E. S., et al. (2014). Revisiting the structure of the Vps10 domain of human sortilin and its interaction with neurotensin. Protein Sci. 23 1291–1300. 10.1002/pro.2512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quistgaard E. M., Madsen P., Groftehauge M. K., Nissen P., Petersen C. M., Thirup S. S. (2009). Ligands bind to sortilin in the tunnel of a ten-bladed beta-propeller domain. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 16 96–98. 10.1038/nsmb.1543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabinowich L., Fishman S., Hubel E., Thurm T., Park W. J., Pewzner-Jung Y., et al. (2015). Sortilin deficiency improves the metabolic phenotype and reduces hepatic steatosis of mice subjected to diet-induced obesity. J. Hepatol. 62 175–181. 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.08.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers M. L., Bailey S., Matusica D., Nicholson I., Muyderman H., Pagadala P. C., et al. (2010). ProNGF mediates death of natural killer cells through activation of the p75NTR-sortilin complex. J. Neuroimmunol. 226 93–103. 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2010.05.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum T., Vidaltamayo R., Sanchez-Soto M. C., Zentella A., Hiriart M. (1998). Pancreatic beta cells synthesize and secrete nerve growth factor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95 7784–7788. 10.1073/pnas.95.13.7784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rui L., Aguirre V., Kim J. K., Shulman G. I., Lee A., Corbould A., et al. (2001). Insulin/IGF-1 and TNF-alpha stimulate phosphorylation of IRS-1 at inhibitory Ser307 via distinct pathways. J. Clin. Invest. 107 181–189. 10.1172/JCI10934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi J., Huang G., Kandror K. V. (2008). Self-assembly of Glut4 storage vesicles during differentiation of 3T3-L1 adipocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 283 30311–30321. 10.1074/jbc.M805182200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soligo M., Protto V., Florenzano F., Bracci-Laudiero L., De Benedetti F., Chiaretti A., et al. (2015). The mature/pro nerve growth factor ratio is decreased in the brain of diabetic rats: analysis by ELISA methods. Brain Res. 1624 455–468. 10.1016/j.brainres.2015.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sposato V., Manni L., Chaldakov G. N., Aloe L. (2007). Streptozotocin-induced diabetes is associated with changes in NGF levels in pancreas and brain. Arch. Ital. Biol. 145 87–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teng H. K., Teng K. K., Lee R., Wright S., Tevar S., Almeida R. D., et al. (2005). ProBDNF induces neuronal apoptosis via activation of a receptor complex of p75NTR and sortilin. J. Neurosci. 25 5455–5463. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5123-04.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood J. G., Hoang H. D., Bussjaeger L. J., Solomon T. E. (1988). Effect of neurotensin on pancreatic and gastric secretion and growth in rats. Pancreas 3 332–339. 10.1097/00006676-198805000-00015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]