Abstract

Background

Increasing use of medicinal herbs as nutritional supplements and traditional medicines for the treatment of diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and malaria fever with conventional drugs poses possibilities of herb–drug interactions (HDIs). The potential of nine selected widely used tropical medicinal herbs in inhibiting human cytochrome P450 (CYP) isoenzymes was investigated.

Materials and methods

In vitro inhibition of eight major CYP isoenzymes by aqueous extracts of Allium sativum, Gongronema latifolium, Moringa oleifera, Musa sapientum, Mangifera indica, Tetracarpidium conophorum, Alstonia boonei, Bauhinia monandra, and Picralima nitida was estimated in human liver microsomes by monitoring twelve probe metabolites of nine probe substrates with UPLC/MS‐MS using validated N‐in‐one assay method.

Results

Mangifera indica moderately inhibited CYP2C8, CYP2B6, CYP2D6, CYP1A2, and CYP2C9 with IC 50 values of 37.93, 57.83, 67.39, 54.83, and 107.48 μg/ml, respectively, and Alstonia boonei inhibited CYP2D6 (IC 50 = 77.19 μg/ml). Picralima nitida inhibited CYP3A4 (IC 50 = 45.58 μg/ml) and CYP2C19 (IC 50 = 73.06 μg/ml) moderately but strongly inhibited CYP2D6 (IC 50 = 1.19 μg/ml). Other aqueous extracts of Gongronema latifolium, Bauhinia monandra, and Moringa oleifera showed weak inhibitory activities against CYP1A2. Musa sapientum, Allium sativum, and Tetracarpidium conophorum did not inhibit the CYP isoenzymes investigated.

Conclusion

Potential for clinically important CYP‐metabolism‐mediated HDIs is possible for Alstonia boonei, Mangifera indica, and Picralima nitida with drugs metabolized by CYP 2C8, 2B6, 2D6, 1A2, 2C9, 2C19, and 3A4. Inhibition of CYP2D6 by Picralima nitida is of particular concern and needs immediate in vivo investigations.

Keywords: chronic diseases, cytochrome P450 isoenzymes, herb–drug interactions, in vitro assay, medicinal herbs, traditional medicines

1. INTRODUCTION

Management of chronic diseases is burdensome to patients (Eton et al., 2013; Ørtenblad, Meillier, & Jønsson, 2017) who tend to seek alternative remedies to conventional medications that may supposedly provide cure or offer safe use (Yarney et al., 2013; Joeliantina, Agil, Qomaruddin, Jonosewojo, & Kusnanto, 2016) This self‐medication practice is common among chronically ill patients or patients with terminal diseases (Bodenheimer, Lorig, Holman, & Grumbach, 2002; Hasan, Ahmed, Bukhari, & Loon, 2009), and the major culprit in this group of patients are dietary supplements and herbal medicines (Gardiner, Graham, Legedza, Eisenberg, & Phillips, 2006; Gardiner, Phillips, & Shaughnessy, 2008). The perceived believe of cure and safety of these agents makes ambulatory patients take them without due recourse to their physician (Mehta, Gardiner, Phillips, & McCarthy, 2008; Zhang, Onakpoya, Posadzki, & Eddouks, 2015).

In various settings, about 40%–57% of patients fail to disclose herbs used concomitantly with their medications to the physician (Robinson & McGrail, 2004; Fakeye, Tijani, & Adebisi, 2008; Kennedy, Wang, & Wu, 2008). Some of these herbs especially in sub‐Saharan Africa, India, and in some other parts of the world are consumed as seasoning agents (garlic—Allium sativum), vegetables (Gongronema latifolium and Moringa oleifera), and as edible fruits and seeds (Musa sapientum, Mangifera indica, and Tetracarpidium conophorum). Patients who are on medications and consumes these medicinal herbs may not be aware of potential herb–drug interactions (HDIs) that may occur. Others such as Alstonia boonei, Bauhinia monandra, and Picralima nitida are frequently used in sub‐Saharan Africa and India in the management of chronic diseases such as hypertension, diabetes, asthma, peptic ulcer, and cancer, as antimalarials and antimicrobials and other minor ailments (Mahomoodally, 2013; Ezuruike & Prieto, 2014; Iwu, 2014).

Sometimes, in the treatment of these diseases, herbs may be used singly or in combination and prepared as dried powder or decoction. There are many examples of such practice. For example, for rheumatism, bark of Picralima nitida, leaves of Allium ascalonicum, Calliandra portoricensis, and Xylopia aethiopica are grounded, cooked, and 15 ml of the mixture is mixed with corn pap and taken once daily (Olorunnisola, Adetutu, & Afolayan, 2015). For anemia, a mixture of the bark of Mangifera indica and fruits of Aframomum melequeta is dried and powdered with one tablespoonful administered daily (Gbadamosi, Moody, & OYekini, 2012). A decoction of dried bark of Alstonia boonei is also taken two‐ to three times daily by diabetic patients to lower blood glucose (Adotey, Adukpo, Opoku Boahen, & Armah, 2012).

Many diseases are usually managed or treated with conventional medicines which are mostly metabolized by cytochrome P450 (CYP) isoenzymes (Rendic & Guengerich, 2014). These isoenzymes are responsible for the metabolism of over 70% of prescription and over‐the‐counter medications (Rendic & Guengerich, 2014). Concomitantly administered drug may modulate these CYP isoenzymes activities leading to clinically significant drug–drug interactions. Such interaction may result in serious adverse drug reactions requiring hospitalization, especially drugs with narrow therapeutic index such as carbamazepine, theophylline, digoxin warfarin, and phenytoin (Greenblatt & von Moltke, 2005; Perucca, 2006; de Leon, 2007; Patel, Rana, Suthar, Malhotra, & Patel, 2014). It is thus rational to expect herbs to also elicit similar HDIs via modulation of cytochrome P450 isoenzymes when concomitantly administered with conventional drugs.

Herbs contain bioactive secondary metabolites such as anthocyanins, flavonoid, tannins, saponins, alkaloids, and cardenolides, some of which have been shown to inhibit the activity of CYP isoenzymes (Henderson, Miranda, Stevens, Deinzer, & Buhler, 2000; Dreiseitel et al., 2008; Kimura, Ito, Ohnishi, & Hatano, 2010; Sand et al., 2010). Several studies have documented the occurrence of serious adverse events as a result of concurrent administration of herbs and drugs. Such interactions included bleeding experienced with coadministration of Allium sativum and nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (Fugh‐Berman, 2000), manic episode with Panax ginseng and phenelzine (Fugh‐Berman, 2000), and fatal seizure with concomitant administration of Ginkgo biloba and valproate (Kupiec & Raj, 2005). Several herbs such as St. John's wort, grapefruit juice, Ginkgo biloba, black pepper, and Echinacea are known inhibitors of CYP 2C9, 2C19, 2E1, and 3A4 (Wang et al., 2001; Gorski et al., 2004; Mohutsky, Anderson, Miller, & Elmer, 2006; Sukkasem & Jarukamjorn, 2016). Little is known of the effect of most tropical medicinal herbs on the metabolic capacity of CYP isoenzymes.

The possibility of occurrence of HDIs when herbs are consumed as seasoning agents, vegetables, fruits and as herbal medicines with conventional drugs informed this study. Since inhibition of CYP isoenzymes is the first step toward elucidating potential HDIs, this study evaluated nine widely used tropical medicinal herbs with a view to identifying those with potentials for CYP‐metabolism‐mediated HDIs.

Some of the herbs considered in this study have also been shown to inhibit CYP isoenzymes. Allium sativum inhibits CYP 2C9, 2C19, 2D6, 3A4/5, and 3A7 (Foster et al., 2001; Greenblatt, Leigh‐Pemberton, & von Moltke, 2006; Engdal & Nilsen, 2009); Moringa oleifera—CYP 1A2, 3A4, and 2D6 (Monera, Wolfe, Maponga, Benet, & Guglielmo, 2008; Taesotikul, Navinpipatana, & Tassaneeyakul, 2010; Ahmmed et al., 2015; Awortwe, 2015); Musa sapientum—CYP 1A2 and 3A11 (Chatuphonprasert & Jarukamjorn, 2012) while Mangifera indica has been shown to inhibit CYP 1A2, 2C9, 2C19, 2D6, 3A4, and 3A11 (Chatuphonprasert & Jarukamjorn, 2012). In the above studies, different enzyme sources, probe substrates, and extraction methods were employed in evaluating one to five CYP isoenzyme inhibition profiles of the stated herbs which do not represent the full complement of major human CYP isoenzymes. The present study improved on this by mimicking local methods of preparation of plant extracts, used pooled human liver microsomes containing eight major CYP isoenzymes responsible for over 70% metabolism of drugs (Rendic & Guengerich, 2014), and nine probe substrates with N‐in‐one cocktail method to profile the inhibitory potentials of the herbs on CYP isoenzymes.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Preparation of aqueous extracts of plant parts

Nine medicinal herbs widely used in the tropics for the management of chronic diseases such as hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, chronic kidney disease were selected for this study with the plant parts used and listed in Table 1. Plant parts used were sourced from open market and herb vendors. Some were identified and authenticated at the Department of Pharmacognosy, University of Ibadan with voucher numbers DPHUI 1385, DPHUI 1386, DPHUI 1387, DPHUI 1388, and DPHUI 1624 for Alstonia boonei, Mangifera indica, Musa sapientum, Bauhinia monandra, and Moringa oleifera leaves, respectively. Other plants parts such as Tetracarpidium conophorum seeds, Picralima nitida seed, Allium sativum bulb, and Gongronema latifolium leaves were collected and identified at Forestery Research Institute of Nigeria with voucher numbers No. FHI110276, FHI210232, FHI210233, and FHI210234, respectively. Plant parts were chopped into smaller bits and dried in the oven (Gallenhamp oven, Cat number GVH 500.010 G. Germany) separately at 40°C for 24–48 hr until a constant weight was obtained. Thereafter, each plant part was blended with Kenwood blender (model number: OWBL436003, China) for 3 min.

Table 1.

Detail of medicinal herbs used in the screening of potential inhibition of cytochrome P450 isoenzymes

| Name of herb | Family name | Part used | Local name | Common name | Usesa | Usual human dosage of dried powdered material |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alstonia boonei De Wild | Apocynaceae | Stem bark |

Ahun (Y) Egbu (I) |

Stoolwood Devil tree |

Antimalarial, Aphrodisiac, Antidiabetic, Antimicrobial, and Antipyretic | 1.5–3 gb |

| Bauhinia monandra Kurz | Leguminosae | Leaves | Abefe (Y) |

Pink orchid Napoleon's plume |

Pesticidal, Antimicrobial, Laxative, Antidiabetic | 3–6 gc |

| Musa sapientum Linn | Musaceae | Unripe fruits |

Ogede (Y) Abrika (I), Ayaba (H) |

Banana | Antidiabetic, Anemia, Hypertension, Ulcers | 1–4 gc |

| Tetracarpidium conophorum (Mull.‐Arg.) Hutch. & Dalz. | Euphorbiaceae | Seeds | Asala (I) | Walnut | Antidiabetic, Anti‐ulcer, Antimicrobial, Anitihypercholesterolemia. | 5–8gd |

| Gongronema latifolium Benth. | Asclepiadaceae | Leaves |

Madunmaro (Y) Utazi (I) Arokeke (Y), |

Amaranth globe. | Antidiabetic, Antimicrobial, Antiparasitic, Hypertension, Laxative, Analgesic, Fevers | 2–4 ge |

| Picralima nitida (Stapf) T. Durand and H. Durand | Apocynaceae | Seeds |

Mkpokiri or Otosu (I) Abere (Y) |

Akuamma plant | Antidiabetic, Jaundice, Pneumonia, Malaria, Hypertension | 3–4 ge |

| Mangifera indica Linn | Anacardiaceae | Stem bark | Mangoro (Y) | Mango | Antidiabetic, Malaria, Analgesic, Diarrhea, Menorrhagia, Hypertension, Anemia, | 1–3 gc |

| Moringa oleifera Lam. | Moringaceae | Leaves |

Ewe igbale (Y), Zogale (H), Okwe‐oyibo (I), |

Drumstick or Horse radish tree, Moringa | Antidiabetic, Anti‐cancer, Anemia, Hypertension, Aphrodisiac. | 1–3 gc |

| Allium sativum L. | Amaryllidaceae | Bulb |

Aayu (Y), Ayo‐ishi (I), Tafarunua (H) |

Garlic | Antidiabetic, Hypertension, Hemorrhoids, Tumors | 0.4–1.2 gf or 3–5 gc |

Three hundred gram each of dried and powdered Alstonia boonei stem bark, Mangifera indica stem bark, Musa sapientum unriped fruits, Bauhinia monandra leaves, Tetracarpidium conophorum seeds, Allium sativum bulb, and Gongronema latifolium leaves were macerated in 1.5 L of distilled water for 24 hr according to extraction procedure practiced locally by users of these herbs. Dry powdered Moringa oleifera leaves (50 g) and powdered dry Picralima nitida seeds (70 g) were each macerated in 300 ml of distilled water. Each mixture was filtered, concentrated, and freeze‐dried. The freeze‐dried extracts were stored at −20°C until needed for in vitro analysis.

2.2. Chemicals

Acetic acid and HPLC‐grade acetonitrile were purchased from Merck (LiChrosolv GG, Darmstadt, Germany). Hydroxydiclofenac, desmethylomeprazole, 3‐hydroxyomeprazole, and hydroxycoumarin were obtained from Sigma‐Aldrich, St Louis, USA; 6‐hydroxytestosterone, dextrorphan, and desethylamodiaquine form BD Biosciences Discovery Labware, Bedford, USA; 5‐hydroxyomeprazole and omeprazole sulfone from Astra Zeneca, M¨olndal, Sweden; 1‐hydroxymidazolam from F. Hoffmann‐La Roche, Basel, Switzerland; phenacetin from ICN Biomedicals, Costa Mesa, USA. Hydroxybupropion was a free gift from Glaxo SmithKline Research Triangle, NC. Water used was purified by Simplicity 185 water purifier (Millipore, Molsheim, France). All other chemicals and reagents were of analytical grade.

2.3. CYP inhibition experiments

Human liver microsomes were obtained from a pool of liver samples from 25 male and female donors and contain 20 mg protein/ ml (Lot No: 99268 from BD Biosciences Labware, Bedford, MA). This was used for the metabolite profiling and CYP inhibition study. N‐in‐one approach (cocktail‐approach) for elucidating inhibition toward CYP‐specific model reactions was conducted with minor changes as described in earlier studies (Turpeinen, Jouko, Jorma, & Olavi, 2005; Tolonen, Petsalo, Turpeinen, Uusitalo, & Pelkonen, 2007; Showande, Fakeye, Ari, & Hokkanen, 2013). Briefly, the incubation mixture was made up of 0.3 mg microsomal protein/ml, 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.4), 1 mM NADPH, and nine probe substrates representing the major drug‐metabolizing CYPs. The specific probe substrate used for each CYP isoenzymes studied and the respective final concentration in the incubation mixture were as follows: acetaminophen (CYP1A2, 10 μM), coumarin (CYP2A6, 2 μM), bupropion (CYP2B6, 2 μM), repaglinide (CYP2C8, 5 μM), diclofenac (CYP2C9, 5 μM), omeprazole (CYP2C19 and CYP3A4, 5 μM), dextromethorphan (CYP2D6, 1 μM), midazolam (CYP3A4, 1 μM), and testosterone (CYP3A4, 5 μM). Each freeze‐dried aqueous herb extract was dissolved into methanol and added to the incubation mixture to obtain final concentrations of 0.001, 0.01, 0.1, 1, 10, 100, and 1000 μg/ml. The resulting reaction mixture (200 μl) contains 1% (v/v) methanol. This was preincubated in a shaking incubator block (Eppendorf Thermomixer 5436, Hamburg, Germany) for 6 min at 37°C prior to the initiation of the reaction with the addition of NADPH. Each reaction mixture containing different herb extracts or solvent control and other components was stopped after a period of 15 min by adding 200 μl of ice‐cold acetonitrile. Proteins were precipitated from the sample by cooling it in an ice bath. Supernatants collected from the samples were then stored at −20°C until analyzed. Prior to analysis, all incubation samples were thawed at room temperature, votex‐mixed, and centrifuged for 10 min at 10000 g. The experiments were performed in duplicate. The validated parameters for the methods were adequate for quantification ranges < 1%–300% of the forming metabolite concentrations with LOD 0.2–10 nM, accuracies 85%–115%, and precisions <15% at all concentrations, and with good autosampler stability (>95%) up to 48 hr. Positive controls (see Supporting Information data, Table S1), CYP isoenzymes inhibited, and concentration used in the N‐in‐one assay are as reported in the validated methods (Turpeinen et al., 2005; Tolonen et al., 2007; Showande et al., 2013). Spiked standard samples were not used for quantification of probe metabolites, but quantification based on relative peak areas was used (solvent control = 100%).

2.4. Liquid chromatography‐mass spectrometry conditions

The analysis of probe metabolites from CYP‐specific marker reactions was conducted with a LC/MS/MS method modified from earlier works (Turpeinen et al., 2005; Tolonen et al., 2007) and also reported by (Showande et al., 2013). Briefly, a Waters Acquity UPLC system (Waters Corp., Milford, MA) was used together with a Waters HSS C18 column (2.1 mm × 50 mm; 1.8 μm particle size) and an online filter at 35°C. The injection volume was 4 μl, and UPLC eluents were aqueous 0.1% acetic acid (pH 3.2, A) and acetonitrile (B). The gradient elution from 2%–65%–95% B was applied in 0–2.5–3.5 min, followed by column equilibration, giving a total time of 4.5 min/injection. The eluent flow rate was 0.5 ml/min. Data were acquired using a Thermo TSQ Endura triple quadrupole MS. Multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) mode using positive ion mode. For all compounds, the spray voltage was 4500 V, vaporizer temperature and transfer tube temperature were 400°C and 350°C, respectively. The CID argon pressure was set to 2.0 mTorr. The MRM transitions were as previously described (Tolonen et al., 2007; Turpeinen et al., 2005). For acetaminophen, hydroxyrepaglinide and 4‐hydroxydiclofenac MRM's were m/z 152 > m/z 110, m/z 469 > m/z 246, m/z 312 > m/z 231, respectively. The instruments were controlled using Thermo Xcalibur 3.0.63 software.

2.5. Data analysis

2.5.1. Determination of IC50

Fifty percent inhibitory concentration (IC50) values were determined graphically from the logarithmic plot of inhibitor concentration (concentrations of the aqueous extract of each herb) versus percentage of enzyme activity remaining after inhibition using GraphPad Prism 5.40 software (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA). The model equation (1) for the plot was.

| (1) |

where A = log of concentration of aqueous extract of herb in the incubations.

2.5.2. Classification of inhibitory potential of herb extract

The herb extracts were classified as potent, moderate, or weak inhibitor depending on the IC50 obtained (Gwaza et al., 2009; Sevior et al., 2010; Kong et al., 2011). Potent inhibitors have IC50 ≤ 10 μg/ml, moderate inhibitors have IC50 >10 μg/ml ‐ ≤100 μg/ml, and weak inhibitors have IC50 > 100 μg/ml. In this study, significant in vitro inhibition is considered as IC50 < 100 μg/ml (Sevior et al., 2010).

2.5.3. Prediction of possibility of in vivo herb–drug interactions from in vitro data

Determination of molar IC50 values in herbal extracts is challenging thus representing the in vitro IC50 values in Liter/dose as described by Strandell, Neil, and Carlin (2004) gives insight into possibility of in vivo inhibition. The volume to which an estimated human unit dose of the aqueous extract of each herb should be diluted in vivo to give similar in vitro inhibitory concentration for each CYP isoenzymes was calculated using the equation (2)

| (2) |

3. RESULTS

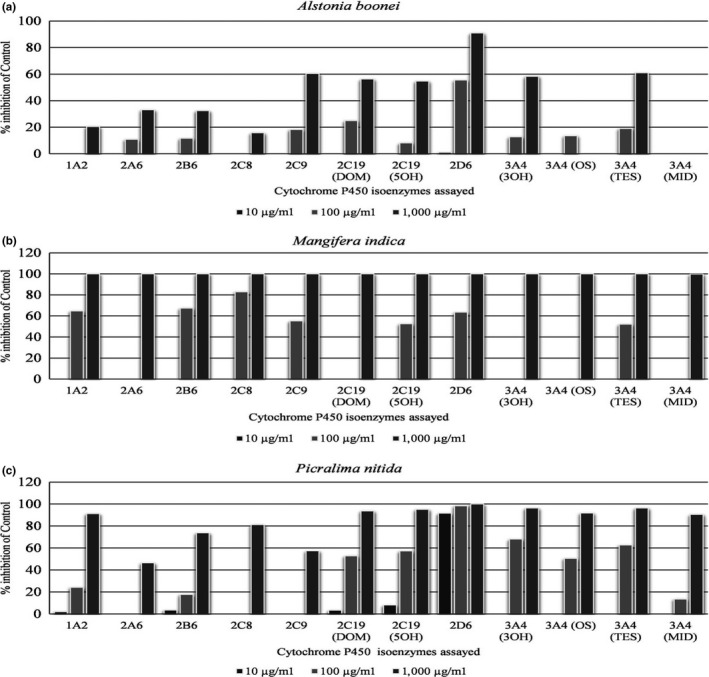

Aqueous extracts of Musa sapientum unripe fruits, Tetracarpidium conophorum seeds, and Allium sativum bulbs did not produce significant inhibition of the CYP isoenzymes investigated at any of the concentrations used, IC50 > 1000 μg/ml. But Gongronema latifolium, Bauhinia monandra, and Moringa oleifera leave extracts showed weak inhibition of CYP1A2 with IC50 > 100 μg/ml (Table 2). Alstonia boonei stem bark aqueous extract also weakly inhibited CYP2C9, CYP2C19, and CYP3A4 but moderately inhibited CYP2D6 (Table 2). The inhibition of CYP2D6 was dose‐dependent inhibition (Figure 1a).

Table 2.

Estimated in vitro IC50 values (μg/ml) for commonly used tropical medicinal herbs

| CYP isoenzyme, metabolite monitored | Alstonia boonei | Mangifera indica | Musa sapientum | Allium sativum | Tetracarpidium conophorum | Gongronema latifolium | Bauhinia monandra | Moringa oleifera | Picralima nitida |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CYP1A2, ACET | 1104.95 | 54.83 | 1877.67 | 1431.57 | 1885.55 | 612.73 | 342.23 | 320.44 | 242.17 |

| CYP2A6, 7‐OH‐COU | 1916.01 | 222.72 | ND | ND | 4454.91 | 1103.52 | 1155.57 | 1343.99 | 862.60 |

| CYP2B6, OH‐BUP | 1213.23 | 57.83 | 1599.17 | 2318.16 | 3490.68 | 1096.56 | 1124.28 | 2280.15 | 469.00 |

| CYP2C8, OH‐REPA | 3209.33 | 37.93 | 27700.95 | 18745.49 | ND | 1255.15 | 389.37 | 1505.32 | 482.77 |

| CYP2C9, OH‐DICL | 507.96 | 107.48 | 48418.95 | 11285.64 | ND | 61940.47 | 1636.28 | 698.93 | 814.10 |

| CYP2C19, DeM‐OME | 356.20 | 115.48 | 4564.07 | 11897.19 | 12435.72 | 985.15 | 1329.80 | 1018.33 | 84.90 |

| CYP2C19, 5‐OH‐OME | 604.11 | 88.03 | 7129.64 | 7388.26 | 4683.85 | 700.66 | 1075.17 | 1108.75 | 73.06 |

| CYP2D6, OdeM‐DEX | 77.19 | 67.39 | 5783.82 | 12064.57 | 14054.21 | 1831.03 | 845.45 | 1929.26 | 1.19 |

| CYP3A4, 3‐OH‐OME | 460.99 | 104.56 | 8329.64 | ND | 5221.69 | 782.51 | 1441.96 | 3421.92 | 45.58 |

| CYP3A4, SO2‐OME | 973.88 | 125.79 | 17804.40 | 41358.77 | 8768.02 | 968.97 | 2291.01 | 7129.55 | 74.68 |

| CYP3A4, 6β‐OH‐TES | 529.63 | 90.89 | 10572.55 | ND | 5841.71 | 489.35 | 1030.02 | 2084.59 | 57.39 |

| CYP3A4, 1‐OH‐MDZ | 4411.11 | 203.63 | ND | ND | 82787.13 | 3384.92 | 10694.17 | ND | 222.64 |

IC50 value in bold represent significant inhibition of CYP isoenzymes with IC50 < 100 μg/ml, (ND) Not determined. Metabolites monitored the following: acetaminophen (ACET), 7‐hydroxycoumarin (7‐OH‐COU), hydroxybupropion (OH‐BUP), hydroxyrepaglinide (OH‐REPA), 4‐hydroxydiclofenac (OH‐DICL), 5‐hydroxyomeprazole (5‐OH‐OME), desmethylomeprazole (DeM‐OME), Dextrorphan (OdeM‐DEX), 3‐hydroxyomeprazole (3‐OH‐OME), omeprazole sulfone (SO2‐OME), 6β‐hydroxytestosterone (6β‐OH‐TES), 1‐hydroxymidazolam (1‐OH‐MDZ).

Figure 1.

Percentage inhibition of the control by herbs with IC50 < 100 µg/ml–aqueous extracts of Alstonia boonei (a), Mangifera indica (b), and Picralima nitida (c). Each bar represents average of duplicate incubations performed at two separate experiments. DOM, desmethylomeprazole; 5OH, 5‐hydroxyomeprazole; 3OH, 3‐hydroxyomeprazole; OS, omeprazole sulphone; TES, 6β‐hydroxytestosterone; MID, 1‐hydroxymidazolam

Aqueous extract of Mangifera indica stem bark showed weak inhibitory activities on CYP2A6, CYP2C19 and CYP3A4 but exhibited moderate inhibition of CYP1A2, CYP2B6, CYP2C8, CYP2C9, and CYP2D6 (Table 2). The plant extract displayed 100% inhibition of all the CYP isoenzymes investigated at a dose of 1000 μg/ml (Figure 1b).

Picralima nitida seeds aqueous extract demonstrated potent inhibitory activity on CYP2D6, with IC50 of 1.19 μg/ml, but moderately inhibited CYP2C19 and CYP3A4 (Table 2). These inhibitory activities were dose‐dependent (Figure 1c).

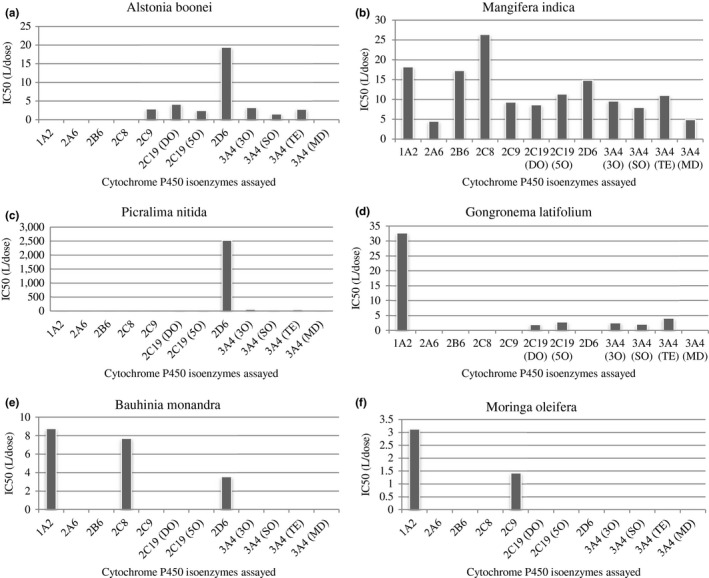

In order to estimate the possibility of in vivo inhibitory potential from the in vitro data, IC50 in L/dose was calculated according to the method described by Strandell et al. (2004). The IC50 values in L/dose are shown in Figure 2 for the herbs with IC50 < 100 μg/ml. Picralima nitida had an exceptionally high value of IC50 value of 2521.01 L/dose for CYP2D6 (Figure 2c). Alstonia boonei had IC50 of 19.43 L/dose for CYP2D6 (Figure 2a), Mangifera indica had IC50 > 14.00 L/dose for CYP1A2, CYP2B6, CYP2C8 and CYP2D6 (Figure 2b). Values of IC50 in L/dose unit for aqueous extracts of Gongronema latifolium, Bauhinia monandra, and Moringa oleifera aqueous extracts are shown in Figure 2d,e,f, respectively.

Figure 2.

Inhibition of cytochrome P450 isoezymes by herbs with IC50 < 1,000 µg/ml–aqueous extracts of Alstonia boonei (a), Mangifera indica (b), Picralima nitida (c), Gongronema latifolium (d), Bauhinia monandra (e), and Moringa oleifera (f). Data represents IC50 in L/dose and each bar is an average of duplicate experiments performed on two different occasions. DOM–desmethylomeprazole, 5OH, 5‐hydroxyomeprazole; 3OH, 3‐hydroxyomeprazole; OS, omeprazole sulphone; TES, 6β‐hydroxytestosterone; MID, 1‐hydroxymidazolam

4. DISCUSSION

Drug–drug interaction or herb–drug interaction studies could be conducted as in vitro or in vivo studies, case reports, and human studies using human subjects. In vitro herb–drug interactions studies are mostly conducted for commonly used herbs to evaluate and predict potentially significant in vivo herb–drug interactions and to help design appropriate in vivo herb–drug interaction studies (Fasinu, Bouic, & Rosenkranz, 2012; Awortwe, Bouic, Masimirembwa, & Rosenkranz, 2013). According to Food and Drug Administration, 2017, in vitro drug–drug interaction (DDI) studies are designed to determine if a drug is a substrate, inhibitor, or inducer of metabolizing enzymes (Phase I or Phase II enzymes), transporter proteins (P‐gp, BCRP, OATP1B1, OATP1B3, OAT, OCT, and MATE) and also to evaluate whether the metabolite of a drug is a substrate or inhibitor of metabolizing enzymes or transporter proteins. These are referred to as metabolism‐based or transporter‐based drug interaction studies. Preclinical methods for predicting drug interactions use enzyme sources such as purified CYP450 isoenzymes, immortalized cell lines, recombinant P450 isoenzymes, liver slices, human microsomes, and hepatocyte cultures. Microsomes isolated from human hepatocytes have become the “gold standard” of in vitro experimentation for drug interactions and contain the CYPs in proportion to their in vivo representation. Pooled human liver microsomes were employed in this study to circumvent the large interindividual variability in CYP expression when microsomes from a single individual are used which may produce biased results. The N‐in‐one assay method employed in this study allows for rapid screening of many herbs or herbal products for inhibitory potential of major human CYP isoenzymes. This may help clinicians and patients to avoid concomitant use of herbs and drugs that may lead to potential or actual HDIs.

Three of the plants studied did not exhibit inhibitory potential on any of the eight major human CYP isoenzymes used even at the highest dose of the extract, that is, aqueous extracts of Musa sapientum unripe fruits, Tetracarpidium conophorum seeds, and Allium sativum bulbs. There are conflicting reports on the inhibitory potential of Allium sativum extracts on CYP isoenzymes. This herb was classified by Engdal and Nilsen (2009) as a noninhibitor of CYP3A4 using human c‐DNA baculovirus expressed CYP3A4. Using similar methods, Foster et al. (2001) reported in vitro inhibition of CYP 2C9, 2C19, 2D6, 3A4/5, and 3A7 by different types of Allium sativum. In another study, only two water‐soluble components of aged garlic were able to moderately inhibit CYP3A4 (Greenblatt et al., 2006). Also, aged garlic extract produced no significant inhibition of CYP isoenzymes in humans (Markowitz, 2003). Though we did not report any inhibition of CYP isoenzymes by Allium sativum, the discrepancies in these reports and ours may be due to the extraction procedure, assay method, concentration and type of the extract used and enzyme sources. In this study, aqueous extract of oven‐dried Allium sativum bulbs was used. There is no conclusive report of a significant in vitro inhibition of CYP isoforms by Allium sativum both from this study and others. Thus, the possibility of Allium sativum aqueous extract in vivo HDIs mediated by CYP isoenzymes may be remote as supported by our study and that of Markowitz (2003).

Aqueous extract of Moringa oleifera leaves showed weak inhibition of CYP1A2 and CYP2C9. This result is similar to the inhibition of CYP1A2 by ethanolic and aqueous extracts of Moringa oleifera leaves reported earlier (Taesotikul et al., 2010). Other studies reported inhibition of CYP3A4 (Ahmmed et al., 2015; Awortwe, 2015; Monera et al., 2008) and CYP2D6 by aqueous and/or ethanolic extract(s) of M. oleifera leaves (Ahmmed et al., 2015) which were not observed in this study. The possibility of in vivo inhibition of CYPs 1A2 and 2C9 by aqueous extract of M. oleifera is likely since the IC50 values in L/dose converted from μg/mL for CYP1A2 and CYP2C9 were 3.12 L/dose and 1.43 L/dose, respectively. These are higher than 0.88 L/dose estimated by Strandell et al. (2004) as the minimum required to elicit further investigation of in vivo inhibitory activity of the plant extract on CYP isoenzyme. However, in vivo study in human showed that M. oleifera did not affect the pharmacokinetic parameters of Nevirapine, a substrate of CYP2C9, CYP2D6, and CYP3A5 (Monera‐Penduka et al., 2017). Nonetheless, couse of Moringa oleifera leave extract with substrates of CYP1A2 and CYP2C9 should be further investigated for possibility of in vivo inhibition of these isoenzymes which may affect therapeutic outcome of coadministered medication.

Stem bark aqueous extract of Mangifera indica moderately inhibited CYP1A2, CYP2B6, CYP2C8, CYP2C9, and CYP2D6 (IC50 < 100 μg/ml) while others CYPs such as 2A6, 2C19, and 3A4 were weakly inhibited (IC50 > 100 μg/ml) by the extract. These results are similar to the inhibition of CYP1A2, CYP2C9, CYP2D6, and CYP3A4 by aqueous extract of Mangifera indica stem bark using human liver microsomes and primary hepatocytes reported by Rodeiro et al. (2008, 2013). Mangifera indica fruit and stem bark extract are commonly used by patients because of the folkloric claims and documented pharmacological activities in ameliorating the signs and symptoms of diabetes, treatment of malaria fever, menorrhagia, hypertension, and hypercholesterolemia (Ezuruike & Prieto, 2014; Awortwe, 2015; Gururaja et al., 2017). Most of the drugs used in the treatment and management of these diseases are metabolized by the major CYP isoenzymes, namely CYP1A2, CYP2C9, CYP2C19, CYP2D6, and CYP3A4 (Ogu & Maxa, 2000; Lynch & Price, 2007). Concomitant use of aqueous extract of Mangifera indica stem bark with substrates of these CYP isoenzymes especially CYP2C8, CYP2C9, and CYP3A4 may predispose the patient to clinically significant HDIs. Coadministration of Mangifera indica fruit with warfarin was found to increase the international normalize ratio (INR) significantly by 38% in thirteen male patients after 2–30 days of consumption (Monterrey‐Rodríguez, Feliú, & Rivera‐Miranda, 2002). This interaction was suggested to be due to the inhibitory effect of Vitamin A, contained in the fruit, on CYP2C19—an enzyme responsible for the metabolism (7‐hydroxylation) of the warfarin R‐isomer (Yamazaki, 1999). Aqueous extract of Mangifera indica bark also showed a weak inhibitory effect on CYP2C19 in the present study.

The potential for Mangifera indica stem bark aqueous extract to cause in vivo HDIs specifically with drugs with narrow therapeutic index is supported by the estimated IC50 values in L/dose which are higher than 5 L. As reported by Strandell et al. (2004), herb extracts with IC50 in L/dose greater than 0.88 L may cause in vivo inhibition of same CYP isoenzymes similar to the observed in vitro inhibitory potential of the herb on the same CYP isoenzymes.

Several studies have used Strandell et al. (2004) methods to predict possibilities of in vivo inhibition of CYP isoenzymes from in vitro data. For example, in vitro study by Sevior et al. (2010) predicted the possible absence of in vivo inhibition of CYP 2D6 and 3A4 by black cohosh and aqueous extract of valerian and inhibition of CYP2D6 by goldenseal. Earlier studies by Gurley et al. (2005, 2006, 2008) confirmed these predictions. Strandell et al. (2004) predicted the likelihood of potent in vivo inhibition of CYP3A4 by hypericum (St John's Wort) preparations; this also confirmed the report of Markowitz et al. (2000).

Currently, no study seems to be available on the in vitro or in vivo inhibitory activity of six of the herbs studied—aqueous extracts of Picralima nitida seeds, Gongronema latifolium leaves, Tetracarpidium conophorum seeds, Musa sapientum unripe fruits, Bauhinia monandra leaves, and Alstonia boonei stem bark. Our study may be the first report of the in vitro inhibitory potential of these herb extracts. Gongronema latifolium and Alstonia boonei may produce in vivo inhibitory activity on CYP1A2, CYP2C19 and CYP3A4 since the converted in vitro IC50 values are greater than 0.88 L/dose despite the weak in vitro inhibitory potential on these isoenzymes. Aside from its medicinal properties, Gongronema latifolium is a popular delicacy in African cuisine (Akinsanmi & Nwanna, 2015; Nwanna et al., 2016). This may increase the possibility of HDIs if drugs are taken after the consumption of a meal containing Gongronema latifolium vegetable. Aqueous extract of Bauhinia monandra leaves is likely to exhibit in vivo inhibition on CYP1A2, CYP2C8, and 3A4 with converted IC50 > 3.0 L/dose unit.

One of the problems of studying herb–drug interactions is the difficulty in identifying or quantifying the inhibiting components of the complex mixtures of phytochemicals in the herb. Because of this, it is difficult to quantify the molar IC50 value of these herbs; thus, the manufacturer recommended dose or the local or traditional dose is used to quantify the possibility of in vivo inhibition from in vitro IC50 values using the method described by Strandell et al. (2004). Though, it was concluded by Strandell et al. (2004) that herbs with converted IC50 > 0.88 L/dose unit should be investigated further for in vivo HDI. However, herbs with IC50 > 5 L/dose unit, the average human blood volume, are more likely to produce significant in vivo HDIs (Strandell et al., 2004).

Picralima nitida seem to be the most potent of the nine herbs studied with IC50 < 100 μg/ml for CYP2C19 and CYP3A4 and IC50 < 10 μg/ml for CYP2D6. The IC50 value converted into L/dose for CYP2C19, CYP3A4, and CYP2D6 far exceeded the 0.88 L/dose unit cutoff point by Strandell et al. (2004). With these values, this herb possesses the ability to elicit clinically significant in vivo HDIs, if used concomitantly with substrates of CYP2D6 such as amitriptyline, metoprolol, clozapine, flucainide, and retonavir (Lynch & Price, 2007). This isoenzyme is phenotypically expressed and the effect of HDIs may vary from one person to another. Thus, it is important to counsel patients not to coadminister this herb with any substrates of CYP2D6 until conclusive clinical data are available.

It should be borne in mind that the IC50 values are apparent values because of the complex mixture of herbs. The preparation of the herb extracts and the dose used also vary between localities. These may affect the computation of the IC50 values in L/dose unit and should be considered when interpreting these results. Also, despite the use of human liver microsomes in the in vitro study, extrapolation of the in vitro findings to in vivo may be limited by the in vivo bioavailability of the phytochemicals in the herbs. In spite of these result limitations, this study assisted in rapidly identifying herb extracts with potential for in vivo HDIs and those requiring further clinical studies.

5. CONCLUSION

Of the nine aqueous herb extracts evaluated in this study, Picralima nitida, Alstonia boonei, and Mangifera indica showed significant in vitro inhibition of several cytochrome P450 isoenzymes including CYP1A2, CYP2B6, CYP2C8, CYP2C9, CYP2C19, CYP2D6, and CYP3A4 with potential for significant clinical herb–drug interactions. The potent in vitro inhibitory effect of aqueous extract of Picralima nitida on CYP2D6 makes it a candidate for immediate further clinical investigations. However, before this is done, caution should be exercised by clinician and patients alike in recommending or coadministering aqueous extracts of Picralima nitida seeds with substrates of CYP2D6.

DISCLOSURE

Authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

ETHICAL STATEMENT

This study does not involve any human or animal testing.

Supporting information

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Authors would like to appreciate the kind gift of Picralima nitida seeds by Dr James Adetunji Bello, The Chief Medical Director, Oyo state Hospital, Ogbomoso.

Showande SJ, Fakeye TO, Kajula M, Hokkanen J, Tolonen A. Potential inhibition of major human cytochrome P450 isoenzymes by selected tropical medicinal herbs—Implication for herb–drug interactions. Food Sci Nutr. 2019;7:44–55. 10.1002/fsn3.789

Funding information

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not‐for‐profit sectors

REFERENCES

- Adotey, J. P. K. , Adukpo, G. E. , Opoku Boahen, Y. , & Armah, F. A. (2012). A review of the ethnobotany and pharmacological importance of alstonia boonei de wild (Apocynaceae). ISRN Pharmacology, 2012, 1–9. 10.5402/2012/587160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmmed, S. K. , Mukherjee, P. K. , Bahadur, S. , Kar, A. , Al‐Dhabi, N. A. , & Duraipandiyan, V. (2015). Inhibition potential of Moringa oleifera Lam. on drug metabolizing enzymes. India J Tradit Knowle, 14, 614–619. Retrieved from http://nopr.niscair.res.in/handle/123456789/33027 [Google Scholar]

- Akinsanmi, A. O. , & Nwanna, E. E. (2015). In vitro comparative studies on antioxidant capacities of Gnetum africanum (“Afang”) and Gongronema latifolium (“Utazi”) leafy vegetables. Journal of Pharmacy & Bioresources, 12, 172–178. 10.4314/jpb.v12i2.13 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Awortwe, C. (2015). Pharmacokinetic herb‐drug interaction study of selected traditional medicines used as complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) for HIV/AIDS. Stellenboschm, South Africa: Stellenbosch University; Retrieved from http://scholar.sun.ac.za/handle/10019.1/96796 [Google Scholar]

- Awortwe, C. , Bouic, P. , Masimirembwa, C. , & Rosenkranz, B. (2013). Inhibition of major drug metabolizing CYPs by common herbal medicines used by HIV/AIDS patients in Africa–implications for herb‐drug interactions. Drug Metabolism Letters, 7, 83–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodenheimer, T. , Lorig, K. , Holman, H. , & Grumbach, K. (2002). Patient Self‐management of Chronic Disease in Primary Care. JAMA, 288, 2469–2475. 10.1001/jama.288.19.2469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatuphonprasert, W. , & Jarukamjorn, K. (2012). Impact of six fruits—banana, guava, mangosteen, pineapple, ripe mango and ripe papaya—on murine hepatic cytochrome P450 activities. Journal of Applied Toxicology, 32, 994–1001. 10.1002/jat.2740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dreiseitel, A. , Schreier, P. , Oehme, A. , Locher, S. , Hajak, G. , & Sand, P. G. (2008). Anthocyanins and their metabolites are weak inhibitors of cytochrome P450 3A4. Molecular Nutrition & Food Research, 52, 1428–1433. 10.1002/mnfr.200800043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engdal, S. , & Nilsen, O. G. (2009). In vitro inhibition of CYP3A4 by herbal remedies frequently used by cancer patients. Phytotherapy Research, 23, 906–912. 10.1002/ptr.2750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eton, D. T. , Elraiyah, T. A. , Yost, K. J. , Ridgeway, J. L. , Johnson, A. , Egginton, J. S. , … Montori, V. M. (2013). A systematic review of patient‐reported measures of burden of treatment in three chronic diseases. Patient Related Outcome Measures, 4, 7–20. 10.2147/PROM.S44694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezuruike, U. F. , & Prieto, J. M. (2014). The use of plants in the traditional management of diabetes in Nigeria: Pharmacological and toxicological considerations. Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 155, 857–924. 10.1016/j.jep.2014.05.055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fakeye, T. O. , Tijani, A. , & Adebisi, O. (2008). A survey of the use of herbs among patients attending secondary‐level health care facilities in Southwestern Nigeria. Journal of Herbal Pharmacotherapy, 7, 213–227. 10.1080/15228940802152901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fasinu, P. S. , Bouic, P. J. , & Rosenkranz, B. (2012). An overview of the evidence and mechanisms of herb‐drug interactions. Frontiers in Pharmacology, 3, 1–19. 10.3389/fphar.2012.00069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Federal Ministry of Health and World Health Organization . (2008, pp7). Nigerian Herbal Pharmacopoiea. Federal Ministry of Health.

- Food and Drug Administration . (2017). Clinical Drug Interaction Studies — Study Design, Data Analysis, and Clinical Implications Guidance for Industry. Clinical Pharmacology.

- Foster, B. C. , Foster, M. S. , Vandenhoek, S. , Krantis, A. , Budzinski, J. W. , Arnason, J. T. , … Choudri, S. (2001). An in vitro evaluation of human cytochrome P450 3A4 and P‐glycoprotein inhibition by garlic. Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, 4, 176–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fugh‐Berman, A. (2000). Herb‐drug interactions. The Lancet, 355, 134–138. 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)06457-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardiner, P. , Graham, R. E. , Legedza, A. T. , Eisenberg, D. M. , & Phillips, R. S. (2006). Factors associated with dietary supplement use among prescription medication users. Archives of Internal Medicine, 166, 1968–1974. 10.1001/archinte.166.18.1968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardiner, P. , Phillips, R. , & Shaughnessy, A. F. (2008). Herbal and dietary supplement–drug interactions in patients with chronic illnesses. American Family Physician, 77, 73–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gbadamosi, I. T. , Moody, J. O. , & OYekini, A. (2012). Nutritional composition of ten ethnobotanicals used for the treatment of anaemia in Southwest Nigeria. European Journal of Medicinal Plants, 2, 140–150. 10.9734/EJMP [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gorski, J. C. , Huang, S. M. , Pinto, A. , Hamman, M. A. , Hilligoss, J. K. , Zaheer, N. A. , … Hall, S. D. (2004). The effect of echinacea (Echinacea purpurea Root) on cytochrome P450 activity in vivo&ast. Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 75, 89–100. 10.1016/j.clpt.2003.09.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenblatt, D. J. , Leigh‐Pemberton, R. A. , & von Moltke, L. L. (2006). In vitro interactions of water‐soluble garlic components with human cytochromes p450. The Journal of Nutrition, 136, 806S–809S. 10.1093/jn/136.3.806S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenblatt, D. J. , & von Moltke, L. L. (2005). Interaction of warfarin with drugs, natural substances, and foods. The Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 45, 127–132. 10.1177/0091270004271404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurley, B. J. , Gardner, S. F. , Hubbard, M. A. , Williams, D. K. , Gentry, W. B. , Khan, I. A. , & Shah, A. (2005). In vivo effects of goldenseal, kava kava, black cohosh, and valerian on human cytochrome P450 1A2, 2D6, 2E1, and 3A4/5 phenotypes&ast. Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 77, 415–426. 10.1016/j.clpt.2005.01.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurley, B. , Hubbard, M. A. , Williams, D. K. , Thaden, J. , Tong, Y. , Gentry, W. B. , & Cheboyina, S. (2006). Assessing the clinical significance of botanical supplementation on human cytochrome P450 3A activity: comparison of a milk thistle and black cohosh product to rifampin and clarithromycin. The Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 46, 201–213. 10.1177/0091270005284854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurley, Bill J. , Swain, A. , Hubbard, M. A. , Williams, D. K. , Barone, G. , Hartsfield, F. , & Battu, S. K. (2008). Clinical assessment of CYP2D6‐mediated herb‐drug interactions in humans: Effects of milk thistle, black cohosh, goldenseal, kava kava, St. John's wort, and Echinacea. Molecular Nutrition & Food Research, 52, 755–763. 10.1002/mnfr.200600300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gururaja, G. M. , Mundkinajeddu, D. , Kumar, A. S. , Dethe, S. M. , Allan, J. J. , & Agarwal, A. (2017). Evaluation of Cholesterol‐lowering Activity of Standardized Extract of Mangifera indica in Albino Wistar Rats. Pharmacognosy Research, 9, 21–26. 10.4103/0974-8490.199770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwaza, L. , Wolfe, A. R. , Benet, L. Z. , Guglielmo, B. J. , Chagwedera, T. E. , Maponga, C. C. , & Masimirembwa, C. M. (2009). In vitro inhibitory effects of Hypoxis obtusa and Dicoma anomala on cyp450 enzymes and p‐glycoprotein. African Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology, 3, 539–546. [Google Scholar]

- Hasan, S. S. , Ahmed, S. I. , Bukhari, N. I. , & Loon, W. C. W. (2009). Use of complementary and alternative medicine among patients with chronic diseases at outpatient clinics. Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice, 15, 152–157. 10.1016/j.ctcp.2009.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson, M. C. , Miranda, C. L. , Stevens, J. F. , Deinzer, M. L. , & Buhler, D. R. (2000). In vitro inhibition of human P450 enzymes by prenylated flavonoids from hops, Humulus lupulus. Xenobiotica, 30, 235–251. 10.1080/004982500237631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwu, M. M. (2014). Handbook of African medicinal plants (2nd edn). Boca Raton, FL: Taylor and Francis, CRC Press; Retrieved from https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=GictAgAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PP1&dq=herbal+medicines+used+for+chronic+diseases+in+africa&ots=3R0_Nnbaw6&sig=oU3mZz-wZYgb9_55fw_0_j0p9N0 [Google Scholar]

- Joeliantina, A. , Agil, M. , Qomaruddin, M. B. , Jonosewojo, A. , & Kusnanto, K. (2016). Responses of diabetes mellitus patients who used complementary medicine. International Journal of Public Health Science (IJPHS), 5, 367–374. 10.11591/.v5i4.4831 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy, J. , Wang, C.‐C. , & Wu, C.‐H. (2008). Patient Disclosure about Herb and Supplement Use among Adults in the US. Evidence‐Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 5, 451–456. 10.1093/ecam/nem045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khare, C. P. (2011). Indian Herbal Remedies: Rational Western Therapy, Ayurvedic and Other Traditional Usage, Botany. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer; Retrieved from https://books.google.com.ng/books?id=njLtCAAAQBAJ [Google Scholar]

- Kimura, Y. , Ito, H. , Ohnishi, R. , & Hatano, T. (2010). Inhibitory effects of polyphenols on human cytochrome P450 3A4 and 2C9 activity. Food and Chemical Toxicology, 48(1), 429–435. 10.1016/j.fct.2009.10.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong, W. M. , Chik, Z. , Ramachandra, M. , Subramaniam, U. , Aziddin, R. E. R. , & Mohamed, Z. (2011). Evaluation of the effects of Mitragyna speciosa alkaloid extract on cytochrome P450 enzymes using a high throughput assay. Molecules, 16, 7344–7356. 10.3390/molecules16097344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kupiec, T. , & Raj, V. (2005). Fatal Seizures Due to Potential Herb‐Drug Interactions with Ginkgo Biloba. Journal of Analytical Toxicology, 29, 755–758. 10.1093/jat/29.7.755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Leon, J. (2007). The crucial role of the therapeutic window in understanding the clinical relevance of the poor versus the ultrarapid metabolizer phenotypes in subjects taking drugs metabolized by CYP2D6 or CYP2C19. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology, 27, 241–245. 10.1097/JCP.0b013e318058244d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch, T. , & Price, A. L. (2007). The Effect of Cytochrome P450 Metabolism on Drug Response, Interactions, and Adverse Effects. American Family Physician, 76, 391–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahomoodally, M. F. (2013). Traditional medicines in Africa: an appraisal of ten potent African medicinal plants. Evidence‐Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 2013. Retrieved from https://www.hindawi.com/journals/ecam/2013/617459/abs/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Markowitz, J. (2003). Effects of garlic (Allium sativum L.) supplementation on cytochrome P450 2D6 and 3A4 activity in healthy volunteers. Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 74, 170–177. 10.1016/S0009-9236(03)00148-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markowitz, J. S. , DeVane, C. L. , Boulton, D. W. , Carson, S. W. , Nahas, Z. , & Risch, S. C. (2000). Effect of St. John’s wort (Hypericum perforatum) on cytochrome P‐450 2D6 and 3A4 activity in healthy volunteers. Life Sciences, 66(9), PL133–PL139. 10.1016/S0024-3205(99)00659-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta, D. H. , Gardiner, P. M. , Phillips, R. S. , & McCarthy, E. P. (2008). Herbal and dietary supplement disclosure to health care providers by individuals with chronic conditions. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 14, 1263–1269. 10.1089/acm.2008.0290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohutsky, M. A. , Anderson, G. D. , Miller, J. W. , & Elmer, G. W. (2006). Ginkgo biloba: Evaluation of CYP2C9 drug interactions in vitro and in vivo. American Journal of Therapeutics, 13, 24–31. 10.1097/01.mjt.0000143695.68285.31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monera, T. G. , Wolfe, A. R. , Maponga, C. C. , Benet, L. Z. , & Guglielmo, J. (2008). Moringa oleifera leaf extracts inhibit 6β‐hydroxylation of testosterone by CYP3A4. The Journal of Infection in Developing Countries, 2, 379–383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monera‐Penduka, T. G. , Maponga, C. C. , Wolfe, A. R. , Wiesner, L. , Morse, G. D. , & Nhachi, C. F. (2017). Effect of Moringa oleifera Lam. leaf powder on the pharmacokinetics of nevirapine in HIV‐infected adults: A one sequence cross‐over study. AIDS Research and Therapy, 14, 12 10.1186/s12981-017-0140-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monterrey‐Rodríguez, J. , Feliú, J. F. , & Rivera‐Miranda, G. C. (2002). Interaction between warfarin and mango fruit. Annals of Pharmacotherapy, 36, 940–941. 10.1177/106002800203600504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuwinger, H. D. (1996). African Ethnobotany: Poisons and Drugs : Chemistry, Pharmacology, Toxicology. Weinheim, Germany: Chapman and Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Nnorom, I. C. , Enenwa, N. E. , & Ewuzie, U. (2013). Mineral composition of ready‐to‐eat walnut kernel (Tetracarpidium conophorum) from southeast Nigeria. Der Chemica Sinica, 4, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Nwanna, E. E. , Oyeleye, S. I. , Ogunsuyi, O. B. , Oboh, G. , Boligon, A. A. , & Athayde, M. L. (2016). In vitro neuroprotective properties of some commonly consumed green leafy vegetables in Southern Nigeria. NFS Journal, 2, 19–24. 10.1016/j.nfs.2015.12.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ogu, C. C. , & Maxa, J. L. (2000). Drug interactions due to cytochrome P450. Proceedings (Baylor University. Medical Center), 13, 421–423. 10.1080/08998280.2000.11927719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olorunnisola, O. S. , Adetutu, A. , & Afolayan, A. J. (2015). An inventory of plants commonly used in the treatment of some disease conditions in Ogbomoso, South West, Nigeria. Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 161, 60–68. 10.1016/j.jep.2014.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ørtenblad, L. , Meillier, L. , & Jønsson, A. R. (2017). Multi‐morbidity: A patient perspective on navigating the health care system and everyday life. Chronic Illness, 1–12. 10.1177/1742395317731607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel, P. S. , Rana, D. A. , Suthar, J. V. , Malhotra, S. D. , & Patel, V. J. (2014). A study of potential adverse drug‐drug interactions among prescribed drugs in medicine outpatient department of a tertiary care teaching hospital. Journal of Basic and Clinical Pharmacy, 5, 44–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perucca, E. (2006). Clinically relevant drug interactions with antiepileptic drugs. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 61, 246–255. 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2005.02529.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pharmasearch . (2006). Pharmaceutical Association of Nigerian Students (PANS), University of Jos.

- Rendic, S. , & Guengerich, F. P. (2014). Survey of human oxidoreductases and cytochrome P450 enzymes involved in the metabolism of xenobiotic and natural chemicals. Chemical Research in Toxicology, 28, 38–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, A. , & McGrail, M. R. (2004). Disclosure of CAM use to medical practitioners: A review of qualitative and quantitative studies. Complementary Therapies in Medicine, 12, 90–98. 10.1016/j.ctim.2004.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodeiro, I. , Donato, M. T. , Lahoz, A. , González‐Lavaut, J. A. , Laguna, A. , Castell, J. V. , … Gómez‐Lechón, M. J. (2008). Modulation of P450 enzymes by Cuban natural products rich in polyphenolic compounds in rat hepatocytes. Chemico‐Biological Interactions, 172, 1–10. 10.1016/j.cbi.2007.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodeiro, I. , José Gómez‐Lechón, M. , Perez, G. , Hernandez, I. , Herrera, J. A. , Delgado, R. , … Teresa Donato, M. (2013). Mangifera indica L. Extract and mangiferin modulate cytochrome P450 and UDP‐glucuronosyltransferase enzymes in primary cultures of human hepatocytes. Phytotherapy Research, 27, 745–752. 10.1002/ptr.4782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sand, P. G. , Dreiseitel, A. , Stang, M. , Schreier, P. , Oehme, A. , Locher, S. , & Hajak, G. (2010). Cytochrome P450 2C19 inhibitory activity of common berry constituents. Phytotherapy Research, 24, 304–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sevior, D. K. , Hokkanen, J. , Tolonen, A. , Abass, K. , Tursas, L. , Pelkonen, O. , & Ahokas, J. T. (2010). Rapid screening of commercially available herbal products for the inhibition of major human hepatic cytochrome P450 enzymes using the N‐in‐one cocktail. Xenobiotica, 40, 245–254. 10.3109/00498251003592683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Showande, S. J. , Fakeye, T. O. , Ari, T. , & Hokkanen, J. (2013). In vitro inhibitory activities of the extract of Hibiscus abdariffa l. (family malvaceae) on selected cytochrome p450 isoforms. African Journal of Traditional, Complementary and Alternative Medicines, 10, 533–540. 10.4314/ajtcam.v10i3.22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strandell, J. , Neil, A. , & Carlin, G. (2004). An approach to the in vitro evaluation of potential for cytochrome P450 enzyme inhibition from herbals and other natural remedies. Phytomedicine: International Journal of Phytotherapy and Phytopharmacology, 11, 98–104. 10.1078/0944-7113-00379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sukkasem, N. , & Jarukamjorn, K. (2016). Herb‐drug interactions via modulations of cytochrome P450 enzymes. วารสารเภสัชศาสตร์อีสาน (Isan Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences, IJPS), 12, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Taesotikul, T. , Navinpipatana, V. , & Tassaneeyakul, W. (2010). Selective inhibition of human cytochrome P450 1A2 by Moringa oleifera. วารสาร เภสัชวิทยา (Thai Journal of Pharmacology), 32, 256–258. [Google Scholar]

- Tolonen, A. , Petsalo, A. , Turpeinen, M. , Uusitalo, J. , & Pelkonen, O. (2007). In vitro interaction cocktail assay for nine major cytochrome P450 enzymes with 13 probe reactions and a single LC/MSMS run: Analytical validation and testing with monoclonal anti‐CYP antibodies. Journal of Mass Spectrometry, 42, 960–966. 10.1002/(ISSN)1096-9888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turpeinen, M. , Jouko, U. , Jorma, J. , & Olavi, P. (2005). Multiple P450 substrates in a single run: Rapid and comprehensive in vitro interaction assay. European Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences, 24, 123–132. 10.1016/j.ejps.2004.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z. , Gorski, J. C. , Hamman, M. A. , Huang, S.‐M. , Lesko, L. J. , & Hall, S. D. (2001). The effects of St John's wort (Hypericum perforatum) on human cytochrome P450 activity. Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 70, 317–326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamazaki, H. (1999). Effects of arachidonic acid, prostaglandins, retinol, retinoic acid and cholecalciferol on xenobiotic oxidations catalysed by human cytochrome P450 enzymes. Xenobiotica, 29, 231–241. 10.1080/004982599238632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yarney, J. , Donkor, A. , Opoku, S. Y. , Yarney, L. , Agyeman‐Duah, I. , Abakah, A. C. , & Asampong, E. (2013). Characteristics of users and implications for the use of complementary and alternative medicine in Ghanaian cancer patients undergoing radiotherapy and chemotherapy: A cross‐ sectional study. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 13, 16 10.1186/1472-6882-13-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J. , Onakpoya, I. J. , Posadzki, P. , & Eddouks, M. (2015). The safety of herbal medicine: From prejudice to evidence. Evidence‐Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 2015(00), 1–3. Retrieved from https://www.hindawi.com/journals/ecam/aa/316706/abs/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials