Abstract

Background:

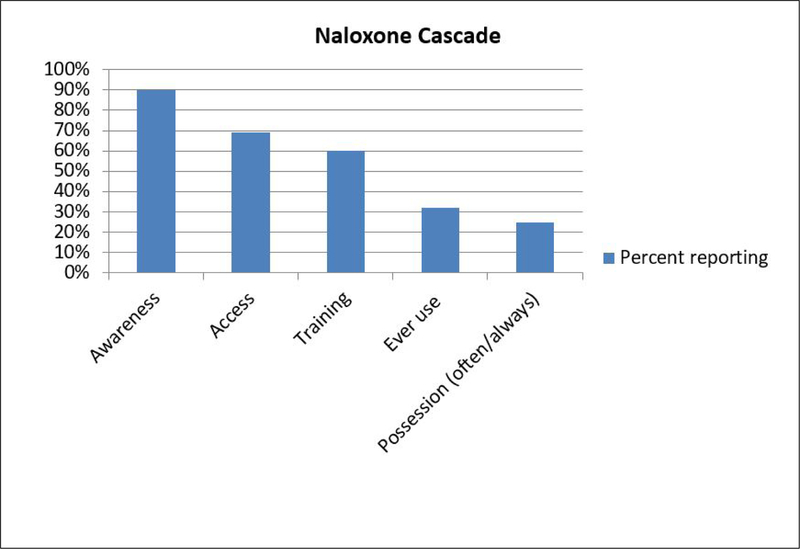

Research demonstrates the positive impact of opioid overdose education and community naloxone distribution (OEND) programs in reducing opioid related overdose deaths. Despite these promising findings opiate overdose continues to be a major cause of mortality. The “cascade of care” is a useful tool for identifying specific steps involved in achieving optimal health outcomes. We applied the cascade concept to identify gaps uptake and use of naloxone: awareness, access, training, possession and use.

Methods:

Data came from a cross-sectional survey of 353 individuals aged 18 and older who self-reported lifetime history of heroin use who were recruited using street-based outreach methods.

Results:

The sample was majority male (65%) and reported use of crack (64%), heroin (74%) and injection (57%) in the past 6 months. Ninety percent had ever witnessed an overdose and of these 59% were in the prior year. Awareness of naloxone (90%) was high. Over two-thirds reported having ever received (e.g. access) (69%) and/or been trained to use naloxone (60%). Over one-third of the sample reported never (37%) or rarely/sometimes carrying naloxone (38%), while 25% reported always carrying. One-third had ever used it (33%). Possession of naloxone often/always compared to never was associated with increased relative odds of being female (RRR=2.77, 95%CI=1.28) and ever use Naloxone (RRR=4.33, 95%CI=1.88–9.99) controlling for other variables.

Conclusions:

This study identifies that consistent possession is a gap in the naloxone cascade. Future research is needed to understand reasons for not always carrying naloxone.

Keywords: naloxone, Narcan, opiate overdose, cascade

1.0. Introduction

Naloxone (Narcan®) is a medication that reverses opiate induced overdoses and does not have any addictive properties or negative effects on non-opiate related overdoses.1,2 Naloxone access has been highlighted as one of the US Department of Health and Human Services’ top three priority areas in response to the country’s ongoing opioid epidemic.3,4 Since the late 1990s, opioid overdose education and community naloxone distribution (OEND) programs have been implemented in 30 states and emerging research shows the positive impact of these programs in reducing opioid related overdose deaths.5 A 2015 systemic review of opioid overdose prevention and naloxone prescribing programs found OEND improves knowledge of opioid overdose and provides participants with the necessary skills and resources to safely administer naloxone to prevent death.6

The Baltimore City Health Department has implemented an overdose prevention and response program since 2004.7 The program has trained and dispensed naloxone to over 18,000 individuals through the city’s needle exchange sites, drug treatment centers, correctional facilities and through on-line trainings. Those trained include substance users, third parties at risk of witnessing an overdose, treatment providers, and correctional staff. Since its inception, the reach of the program has grown substantially, from a total of 7,183 individuals trained in the five-year period from 2004 to 2009, to a total of 10,241 trained in the single year of 2016.7 This has occurred within a context of evolving laws on the prescribing and dispensing of naloxone. In 2015, a statewide standing order allowed for the creation of a “blanket prescription” of naloxone to all Baltimore City residents who held a training certificate.8 In June 2017, a second standing order removed the training requirement and essentially made naloxone available over-the-counter.8,9 According to the Maryland Department of Health, more than 40 pharmacies across Baltimore City stock naloxone, and the medication is covered by the state’s Medicaid plans.9,10

Despite these promising findings opiate overdose continues to be a major cause of mortality. In Baltimore City, from 2015–2016 the death rate due to heroin overdose increased 75% (260 deaths to 454) and 250% from fentanyl (120 deaths to 419).11 Awareness, access and skills to use naloxone are requisite for optimal impact of OENDs. In a sample from a treatment center in New York, 65% were aware about naloxone, yet only 33% knew where they could access it and only 12% had ever witnessed naloxone being used.12 Identifying gaps can enable targeted interventions to increase saturation of naloxone in communities affected by opioid overdoses.

The “cascade of care” has been a useful tool for identifying specific steps involved in achieving optimal health outcomes. The “cascade” concept originated with HIV but has been applied to other health conditions such as diabetes and hepatitis C.13,14 Overdose prevention involves multiple steps. With regards to naloxone distribution programs first individuals must be aware that naloxone is an effective opiate overdose intervention. Then they must have access and training to use. However, in order to be effective in saving lives individuals must have possession during drug use episodes and use it with a victim. The purpose of this study was to identify gaps in uptake and use of naloxone.

2.0. Materials and Methods

A cross-sectional survey was conducted from December 2016 to September 2017 as part of a larger randomized controlled trial for people living with hepatitis C. Participants were recruited by posting flyers at drug treatment centers, medical clinics and other community-based organizations that serve individuals who use drugs and by word-of-mouth. Eligibility criteria were for the study were: aged 18 and older and self-report lifetime history of injection drug use. After providing informed consent participants were interviewed by trained research assistants in a private office. The current analysis was restricted to individuals who reported lifetime use of heroin (n=353). All study procedures were approved by the Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health Institutional Review Board.

2.1. Measures

Naloxone cascade:

Five pillars of the cascade were assessed.

Awareness:

Participants were asked if they had ever heard about Narcan or naloxone (yes/no)

Access:

Participants who were aware about naloxone were asked if they had ever received naloxone (yes/no).”

Training:

Participants who were aware about naloxone were asked if they had ever been trained to use naloxone (yes/no).

Use:

All participants who had heard about naloxone (n=316) were asked if they had ever used naloxone during an overdose (yes/no).

Possession:

Among those who had ever been trained and/or received naloxone were asked how often they carried naloxone with them (never, rarely, sometimes, often, always)

Witnessing overdose experience:

Participants indicated the number of overdoses they had witnessed in their lifetime and when the most recent witnessed overdose occurred. We categorized their responses as never, more than 1 year ago and in the past year.

Personal overdose history:

Participants reported the number of lifetime overdoses they had experienced and when their most recent overdose occurred. We categorized their responses as never, more than 1 year ago, and in the past year.

Drug use characteristics:

Participants self-reported use of heroin, prescription opiates, cocaine, crack and any injection drug use in the prior 6 months (yes/no).

Demographics:

Self-reported sex, age, highest education and homelessness in the prior 6 month were recorded.

2.2. Analysis:

Univariate statistics were used to summarize variables. Comparisons between frequency of carrying naloxone were made using ANOVA for continuous variables and chi square statistics. In instances where the cell size was less than 10 the Fishers exact statistic was applied. The mlogit statistical procedure was used to identify variables independently associated with carrying naloxone. Variables that were statistically significant <0.10 were selected for entry into the mlogit model. We report the relative risk ratios and 95% confidence intervals which are estimations of the Odds Ratio.

3.0. Results

The sample (n=353) was majority male (65%) and mean age was 46.5 years (SD=10.7). Two-thirds had 12th grade education or higher (60%) and 43% reported being homeless in the past 6 months.

More than half reported use of crack (64%), heroin (74%) and injection (57%) in the past 6 months. One-third reported cocaine use and 24% prescription opiate use in the prior 6 months. Two-thirds reported lifetime personal overdose experience and 30% had overdosed in the prior year. Witnessing an overdose was common (90%) and of these 59% had witnessed an overdose in the prior year.

3.1. Naloxone Cascade

Figure 1 displays the naloxone cascade. A majority of the sample were Aware of naloxone (90%), had Access to naloxone (69%) and received Training (60%). One-third of those aware about naloxone had ever used it during an overdose (32%). Over one-third never (37%) or rarely/sometimes carried naloxone (38%), while 25% reported always/often carrying.

Figure 1.

Naloxone cascade among 353 study participants who reported a lifetime history of injection drug use, Baltimore, MD.

Table 1 presents results of bivariate analysis of variables associated with frequency of carrying Narcan. Variables associated with possessing naloxone often/always compared to rarely/sometimes and never were female sex (p=0.06) reported, witnessing an overdose in the prior year (p=0.02), injection in the prior year (p=0.04) and having ever used naloxone (p<0.001) carried naloxone.

Table 1.

Bivariate associations of demographic, drug use and overdose experience with carrying Narcan among 224 study participants who reported having ever received Narcan and/or training to use Narcan, Baltimore, Maryland.

| Never Carry N=83 (37%) |

Rarely/Sometimes carry N=84 (38%) |

Often/Always carry 57 (25%) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | p-value |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 58 (70) | 55 (65) | 29 (51) | |

| Female | 25 (30) | 29 (35) | 28 (49) | 0.06 |

| Mean age (SD) | 47 (11) | 45 (11) | 44 (10) | 0.15 |

| Highest Education | ||||

| <High School | 32 (39) | 27 (32) | 21 (37) | |

| HS/GED | 33 (40) | 39 (46) | 25 (44) | |

| More than 12 years | 18 (22) | 18 (21) | 11 (19) | 0.90 |

| Homeless in the past 6 months | ||||

| No | 51 (61) | 46 (55) | 25 (44) | |

| Yes | 32 (39) | 38 (45) | 32 (56) | 0.12 |

| Inject drugs | ||||

| Never | 2 (2) | 7 (8) | 1 (2) | |

| More than 1 year ago | 31 (37) | 24 (29) | 11 (19) | |

| Within the past year | 50 (60) | 53 (63) | 45 (80) | 0.04 |

| Ever witness overdose | ||||

| Never | 7 (8) | 8 (10) | 0 (0) | |

| More than 1 year ago | 28 (34) | 26 (31) | 11 (20) | |

| Within the past year | 48 (58) | 50 (60) | 46 (81) | 0.02 |

| Ever experience overdose | ||||

| Never | 28 (34) | 24 (29) | 14 (25) | |

| More than 1 year ago | 28 (34) | 33 (39) | 20 (35) | |

| Within the past year | 27 (33) | 27 (32) | 23 (40) | 0.72 |

| Ever use Narcan (n=325) | ||||

| No | 60 (72) | 47 (56) | 17 (30) | |

| Yes | 23 (28) | 37 (44) | 40 (70) | <0.001 |

Results from the multivariate modeling (not shown) indicate that having ever used naloxone was associated with over a two-fold increased relative odds of carrying naloxone rarely/sometimes compared to never (RRR=2.47, 95%CI=1.20–5.10), controlling for sex, ever witnessing an overdose, and injection behavior. Possession of naloxone often/always compared to never was associated with increased relative odds of being female (RRR=2.77, 95%CI=1.28) and ever using naloxone (RRR=4.33, 95%CI=1.88–9.99), controlling for other variables.

4.0. Discussion

While overdose education and naloxone distribution programs nationally and in Baltimore have been successful in training thousands of individuals, opiate overdose remains a significant public health problem. The purpose of this study was to use a cascade approach to identify gaps in naloxone distribution in a sample of individuals who have a history of heroin use. Results indicate high levels of Awareness, Access and Training. However, we observed a substantial gap in Possession and Use. These gaps suggest important targets for public health intervention: namely to increase possession of naloxone. Individuals may be reluctant to carry naloxone to avoid harassment from police due to the association between naloxone and opioid use. Drug use stigma may be a barrier to obtaining refills at pharmacies. Educating law enforcement and pharmacy staff about policy changes that have legitimized possession of naloxone in order to address an opiate epidemic may address individuals’ reluctance to possess naloxone. Another approach is to conduct community-based trainings in neighborhoods in which a high number of overdoses occur open to all residents, regardless of whether they use opiates, with the aim of saturating the households with naloxone and reducing stigma.

We found that having ever used naloxone was associated with often/always possession of naloxone. It may be that individuals who have lived experience of the lifesaving effects of naloxone have greater confidence in the value of possessing the medication. Identifying individuals who have ever used naloxone and training them to be peer-educators and promote naloxone possession to individuals in their social networks is an evidence-based approach to changing social norms and behaviors.15,16

There are a number of limitations to this study. First, the data come from a convenience sample and may not represent people who use drugs who are younger (<30 years old), live in non-urban settings or in locations where the naloxone policies are not as progressive. Data were also self-report and subject to reporting bias.

5.0. Conclusion

These limitations notwithstanding, results of this study indicate that in a context in which structural barriers to naloxone access have been reduced, possession is a critical step in the cascade to impact overdose mortality. While raising awareness and conducting trainings are necessary they are not sufficient. Changing norms about possession and using with individuals who have Naloxone is an important component to overdose prevention and naloxone programs especially as we are experiencing an increase in fentanyl and other synthetic opiates in the illicit drug market.

References

- 1.Boyer EW. Management of opioid analgesic overdose. N Engl J Med 2012;367(2):146–155. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1202561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wermeling DP. Review of naloxone safety for opioid overdose: Practical considerations for new technology and expanded public access. Therapeutic advances in drug safety 2015;6(1):20–31. doi: 10.1177/2042098614564776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kerensky T, Walley AY. Opioid overdose prevention and naloxone rescue kits: What we know and what we don’t know. Addiction Science & Clinical Practice 2017;12(1):4. doi: 10.1186/s13722-016-0068-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wheeler E, Davidson PJ, Jones TS, Irwin KS. Community-based opioid overdose prevention programs providing naloxone-United States, 2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2012;61(6):101–105. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Doe-Simkins M, Quinn E, Xuan Z, et al. Overdose rescues by trained and untrained participants and change in opioid use among substance-using participants in overdose education and naloxone distribution programs: A retrospective cohort study. BMC Public Health 2014;14(1):297. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mueller SR, Walley AY, Calcaterra SL, Glanz JM, Binswanger IA. A review of opioid overdose prevention and naloxone prescribing: Implications for translating community programming into clinical practice. Substance abuse 2015;36(2):240–253. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2015.1010032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baltimore City Health Department. Substance use and misuse http://health.baltimorecity.gov/programs/substance-abuse. Updated 2017.

- 8.Baltimore City Health Department. Baltimore city health commissioner signs new standing order for opioid overdose reversal medication https://health.baltimorecity.gov/news/press-releases/2017-06-01-baltimore-city-health-commissioner-signs-new-standing-order-opioid. Updated 2017.

- 9.Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. Naloxone and the statewide standing order: What you need to know https://bha.health.maryland.gov/NALOXONE/Documents/FINAL%20Naloxone%20Stand.Order%20Ino%20one%20pager%20.pdf Updated 2017.

- 10.Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. Pharmacies that stock naloxone https://bha.health.maryland.gov/NALOXONE/Pages/Pharmacies-that-stock-naloxone-aspxhttps://bha.health.maryland.gov/NALOXONE/Pages/Pharmacies-that-stock-naloxone-aspx Updated 2017.

- 11.Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. Drug- and alcohol-related intoxication deaths in Maryland, 2016 2017.

- 12.Kirane H, Ketteringham M, Bereket S, et al. Awareness and attitudes toward intranasal naloxone rescue for opioid overdose prevention. J Subst Abuse Treat 2016;69:44–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2016.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ali MK, Bullard KM, Gregg EW, del Rio C. A cascade of care for diabetes in the United States: Visualizing the Gaps. Ann Intern Med 2014;161(10):681–689. doi: 10.7326/M14-0019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Linas BP, Barter DM, Leff JA, et al. The hepatitis C cascade of care: Identifying priorities to improve clinical outcomes. PloS one 2014;9(5):e97317. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0097317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tobin KE, Kuramoto SJ, Davey-Rothwell MA, Latkin CA. The STEP into action study: A peer-based, personal risk network-focused HIV prevention intervention with injection drug users in Baltimore, Maryland. Addiction 2011;106(2):366–375. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03146.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marshall C, Perreault M, Archambault L, Milton D. Experiences of peer-trainers in a take-home naloxone program: Results from a qualitative study. International Journal of Drug Policy 2017;41:19–28. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2016.11.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]