Abstract

This study aimed to explore novel long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) and the underlying mechanisms involved in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia (cALL). The GSE67684 dataset was downloaded from the Gene Expression Omnibus. Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) and lncRNAs (DELs) between Days 0, 8, 15 and 33 were isolated using random variance model corrective analysis of variance. Overlapping DEGs and DELs were clustered using Cluster 3.0. Bio-functional enrichment analysis was performed using Gene Ontology (GO) and the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG). Interactions between lncRNAs and mRNAs were calculated using dynamic simulations, and interactions among mRNAs were predicted using the STRING database. lncRNA-mRNA and protein-protein interaction (PPI) networks were visualized using Cytoscape. Subsequently, the expression levels of lncRNAs in biological samples from children with or without cALL were validated using reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR). A total of 593 overlapping DEGs and 21 DELs were identified. After clustering, Profile 26 exhibited a continuously increasing temporal trend, whereas Profile 1 exhibited a continuous decreasing trend. Upregulated DEGs were significantly enriched in 1,825 GO terms and 166 KEGG pathways, whereas downregulated DEGs were significantly enriched in 196 GO terms and 90 KEGG pathways. The lncRNAs NONHSAT027612.2 and NONHSAT134556.2 were the top two regulators in the lncRNA-mRNA network. Toll-like receptor 4, cathepsin G, nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain containing 2 and cathepsin S may be considered the hub genes of the PPI network. RT-qPCR results indicated that the expression levels of the lncRNAs NONHSAT027612.2 and NONHSAT134556.2 were significantly elevated in the blood and bone marrow of patients with cALL compared with the controls. In conclusion, the lncRNAs NONHSAT027612.2 and NONHSAT134556.2 may serve important roles in the pathogenesis of cALL via regulating immune response-associated pathways.

Keywords: childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia, differentially expressed genes, long non-coding RNA

Introduction

Childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia (cALL) arises more often from B-cell lineages than from T-cell lineages (1). The survival rate of cALL is significantly superior in children compared with in adolescents and adults, partly due to the higher prevalence of favorable genetic variations in children, including myeloid/lymphoid leukemia (MLL), cytokine receptor-like factor 2, ETS variant gene 6-runt-related transcription factor 1 and hyperdiploidy (2). After 40 years of research, the cure rate for cALL has significantly improved, and the overall 5-year event-free survival rate has reached ~90% (3). Despite this progress, 10–20% of patients experience relapses, and their prognoses are poor, even after receiving allogeneic stem cell transplantation (4,5). Therefore, it is crucial to further explore the pathogenesis of cALL, particularly its recurrence, and to develop novel treatment strategies. Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) belong to a class of transcripts with no protein-coding capacity, which are >200 bp long (6). Previous studies have demonstrated that lncRNAs have a wide range of regulatory effects on tumorigenesis, including proliferation (7), migration (8), invasion (9), apoptosis (10) and recurrence (11). In addition, mechanisms underlying the involvement of lncRNAs in cALL have previously been explored. Fang et al reported that a set of lncRNAs affects proliferation and apoptosis in MLL-rearranged-cALL via co-expression with the homeobox A gene cluster (12). Trimarchi et al also demonstrated that the lncRNA LUNAR1 is essential for the growth of T-cell ALL (T-ALL) and maintains high expression levels of insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor via a cis-activation mechanism (13). In addition, Trimarchi et al documented that several lncRNAs can be regulated by Notch activity in T-ALL (13). Wang et al demonstrated that the lncRNA NALT interacts with Notch homolog 1, translocation-associated to promote cell proliferation in T-ALL (14). These findings indicated that lncRNAs may serve essential roles in ALL, including cALL.

In 2016, Yeoh et al (15) previously constructed an RNA-seq dataset of the time-dependent gene expression profiles of patients with cALL (GSE67684; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE67684) and revealed that effective response metric was a prognostic factor. This dataset was then analyzed by another research group, which revealed that microRNA-590 promotes cell proliferation and invasion in T-ALL via suppression of RB transcriptional corepressor 1 (16). To further explore the mechanism underlying the involvement of lncRNAs in cALL, this RNA-seq dataset was re-analyzed in the current study using bioinformatics methods to provide novel insights into the ontogeny and treatment of cALL.

Materials and methods

Data source

A time-series gene expression profiling dataset, GSE67684, was downloaded from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE67684). A total of 495 cALL blood samples from 210 children (111 males, 90 females and 9 unknown with 160 patients between 1–10 years and 50 patients <1 or >10 years) were used in this study, including 194 at Day 0, 193 at Day 8, 49 at Day 15 and 59 at Day 33 post-diagnosis. In this time series dataset, expression levels of lncRNAs and mRNAs were detected using the GPL570 [HG-U133 Plus 2] Affymetrix Human Genome U133 Plus 2.0 Array and GPL96 [HG-U133A] Affymetrix Human Genome U133A Array, respectively platforms, respectively (Affymetrix; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA).

Identification of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) and lncRNAs (DELs)

According to the annotation profiles provided by the GPL570 [HG-U133 Plus 2] Affymetrix Human Genome U133 Plus 2.0 Array, expression information of lncRNA-associated probes was analyzed using ExpressionConsole (version 1.1; Affymetrix; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) to evaluate the gene expression levels. BLAST (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) was used to annotate the probes matched to lncRNAs. Additionally, expression information of mRNA-associated probes was analyzed using ExpressionConsole based on the information provided by GPL96 [HG-U133A] Affymetrix Human Genome U133A Array. Subsequently, DEGs and DELs between Day 0, 8, 15 and 33 were screened using random variance model corrective analysis of variance in R 3.5.1 software (https://cran.r-project.org/). Thresholds of DEGs and DELs were set as follows: P≤0.001, false discovery rate (FDR) ≤0.01, and fold change ≥2. Numbers of screened DEGs and DELs were illustrated using Venn diagrams.

Clustering analysis of overlapping DEGs and DELs

Using Venn diagrams, overlapping DEGs and DELs were clustered using Cluster 3.0 (http://bonsai.hgc.jp/~mdehoon/software/cluster/software.htm). Based on these results, significantly different DEG and DEL profiles (clusters) over time were selected using a series test of cluster approach, as previously described (17,18), with P<0.05.

Enrichment analysis of DEGs

To explore the biological functions of DEGs and the pathways in which they are involved, function and pathway enrichments of DEG profiles were conducted using the Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integration Discovery (DAVID; http://david.abcc.ncifcrf.gov/) based on the Gene Ontology (GO; http://www.geneontology.org/) and the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG; http://www.genome.jp/kegg/pathway.html) databases. GO terms and KEGG pathways were considered significantly enriched when the following criteria were met: P≤0.05 and FDR <0.05.

Construction of the lncRNA-mRNA network

According to the significantly enriched GO terms and KEGG pathways, overlapping mRNAs were selected. Using the overlapping mRNA (obtained based on the enrichment of GO terms and KEGG pathways) and overlapping lncRNAs, the interactions between lncRNAs and mRNAs were evaluated using dynamic simulations based on gene-sample matrices, and the Pearson correlation coefficient of each lncRNA-mRNA pair was calculated using the function cor.test (X, Y, method = ‘Pearson’) of R software (19). The pairs with Pearson correlation coefficients >0.8 and P<0.05 were selected; subsequently, the lncRNA-mRNA network was constructed using Cytoscape version 3.0.2 (http://chianti.ucsd.edu/cytoscape-3.0.2/).

Construction of protein-protein interaction network (PPI)

Based on the lncRNA-mRNA network, co-expressed DEGs involved in this network were selected, and the interactions among them were predicted using the Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes (STRING; version 10.0; http://www.string-db.org/) database (functional protein interaction networks). Interactions among proteins were visualized using Cytoscape version 3.0.2 based on these predicted relationship pairs.

Validation of DEL expression

This study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University (Nanjing, China). From March 2016 to July 2017, 44 subjects (23 males, 21 females, with mean age of 7.5 years) were recruited including 14 controls and 30 with cALL. Informed consent was obtained from the subjects' parents prior to participation. A total of 14 blood samples (four without cALL and 10 with cALL) were analyzed using RT-qPCR to verify the expression of DELs identified in this study. In addition, 30 bone marrow samples, including 10 controls and 20 with cALL, were collected to confirm the findings using reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR). The samples in the cALL group were collected from patients with recurrent cALL who were receiving methotrexate chemotherapy and the samples in the control group were collected from healthy individuals. Total RNA was isolated using TRIzol® reagent (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and was quantified using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (NanoDrop; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Wilmington, DE, USA). Subsequently, 1 µg total RNA was reverse transcribed to cDNA using a SuperScript III transcript kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA), according to the manufacturer's protocol. Amplification was performed using SYBR reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) on a Thermo 7500 PCR thermocycler (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) with the following reaction conditions: 95°C for 20 sec, followed by 40 cycles at 95°C for 3 sec and 60°C for 30 sec. GAPDH was used as the internal control for quantitative analysis with the 2−ΔΔCq method (20). Primers of lncRNAs and GAPDH were designed as follows: NONHSAT027612.2, forward, 5′-GAGTGCAGTGGCGTGATCTT-3′ and reverse, 5′-GTGGTGGTGCATGCCTGTAGT-3′; NONHSAT134556.2; forward, 5′-GATCATGCGGTTAAGGAGTGTG-3′ and reverse, 5′-TCATCCTGCTAAGCGCTGAG-3′; GAPDH, forward, 5′-GTGGAGTCCACTGGCGTCTT-3′ and reverse 5′-GTGCAGGAGGCATTGCTGAT-3′. Data are presented as the means ± standard deviation. Comparisons between groups were performed using Student's t-test in SPSS version 15.0 software (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Identification of DEGs and DELs

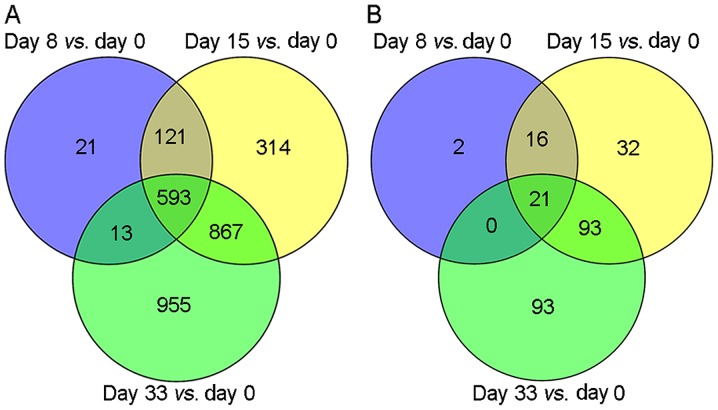

According to the selected thresholds, a total of 748, 1,895 and 2,428 DEGs were identified in the comparisons of Day 0 with Day 8, Day 0 with Day 15, and Day 0 with Day 33, respectively (Fig. 1A). Among these, 593 overlapping DEGs were identified. In addition, a total of 39, 162 and 207 DELs were identified when Day 0 results were compared with results from Day 8, 15 and 33, respectively (Fig. 1B). Among these, 21 overlapping DELs were identified.

Figure 1.

Venn diagrams of (A) differentially expressed genes and (B) long non-coding RNAs at Day 8, 15 and 33 vs. Day 0 post-diagnosis.

Cluster analysis of overlapping DEGs and DELs

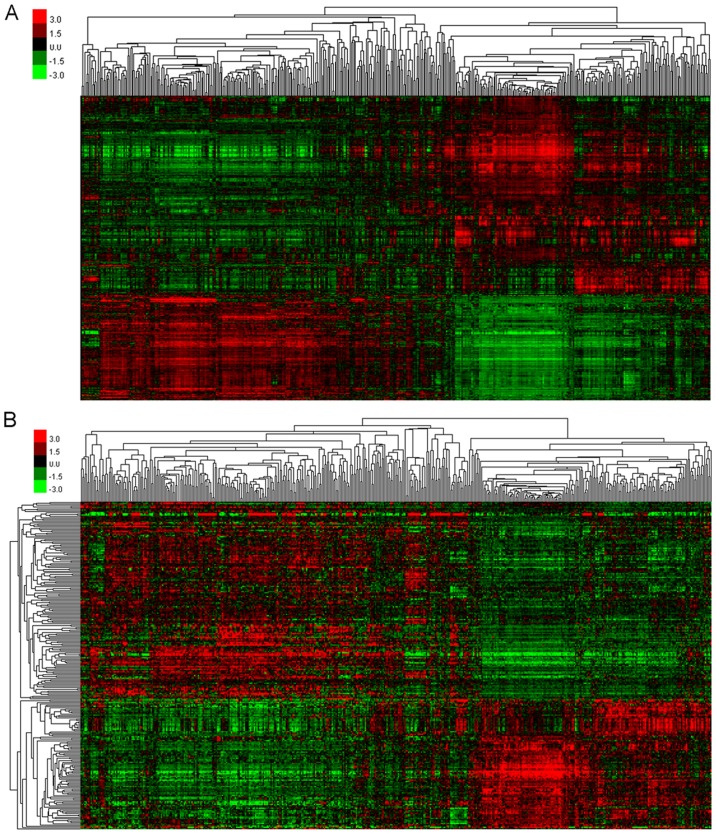

According to the Venn diagram, the overlapping DEGs were clustered (Fig. 2A) to screen for gene profiles with significant variations. A total of eight significantly different profiles were identified, including five upregulated (Profiles 17, 23, 24, 25 and 26) and three downregulated (Profiles 1, 2 and 10) profiles. DEGs included in each of these profiles exhibited a similar tendency to change compared with other DEGs. Furthermore, overlapping DELs were similarly clustered (Fig. 2B) to select those that showed significant variation, and a total of eight profiles were identified, including four upregulated profiles (Profiles 23, 24, 25 and 26) and four downregulated profiles (Profiles 1, 2, 3 and 10). In addition, DELs included in each profile exhibited a similar tendency to change compared with other DELs. Among these profiles, Profile 26 exhibited a continuous increase over time, whereas Profile 1 exhibited a continuous decrease.

Figure 2.

Clustering results of (A) overlapping differentially expressed genes and (B) long non-coding RNAs.

Enrichment analyses of DEGs

Upregulated DEG profiles were significantly enriched in 1,825 GO terms, such as small molecule metabolic process (P=4.64×10−67), signal transduction (P=7.44×10−65), innate immune response (P=1.95×10−63), blood coagulation (P=3.41×10−62) and immune response (P=9.61×10−59). Downregulated DEG profiles were enriched in 196 GO terms, such as transcription DNA-dependent (P=2.32×10−49), regulation of transcription, DNA-dependent (P=1.36×10−43), negative regulation of transcription from RNA polymerase II promoter (P=3.65×10−25), positive regulation of transcription from RNA polymerase II promoter (P=2.48×10−22) and positive regulation of transcription, DNA-dependent (P=1.54×10−19; Table I).

Table I.

The top 10 enriched GO terms of upregulated and downregulated DEG profiles.

| A, Upregulated DEGs | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| GO term | Gene count | P-value | Genes |

| Small molecule metabolic process | 171 | 4.64×10−67 | SAR1B, MARCKS, MGST1, PAPSS2, NMNAT3 … |

| Signal transduction | 147 | 7.44×10−65 | TNFSF14, INPP4B, TNFRSF10C, TNFSF13B, CSF3R … |

| Innate immune response | 110 | 1.95×10−63 | CTSS, FGR, KIR2DS5, CLEC7A, CFP … |

| Blood coagulation | 101 | 3.41×10−62 | TUBA4A, CFL1, ABCC4, ATP2B1, THBS1 … |

| Immune response | 87 | 9.61×10−59 | GZMA, IL18, FCAR, SLC11A1, CEBPB … |

| Inflammatory response | 75 | 1.46×10−51 | SELP, IL18, ANXA1, F2RL1, AOAH … |

| Platelet activation | 57 | 7.95×10−42 | PLA2G4A, COL3A1, TIMP1, MAPK14, ITGB3 … |

| Cell adhesion | 75 | 1.60×10−37 | MPZL3, CX3CR1, FPR2, CD300A, GPNMB … |

| Platelet degranulation | 34 | 3.64×10−32 | PPBP, CFL1, CD36, FN1, TUBA4A … |

| Negative regulation of apoptotic process | 71 | 3.83×10−32 | ITGAV, SFRP1, MPO, CD59, TIMP1 … |

| B, Downregulated DEGs | |||

| GO term | Gene count | P-value | Genes |

| Transcription, DNA-dependent | 121 | 2.32×10−49 | FHIT, TCEA2, KANK2, CHD6, ZNF165 … |

| Regulation of transcription, | 97 | 1.36×10−43 | PHB, ZNF610, PDE8B, BMP2, KLF8 … |

| DNA-dependent | |||

| Negative regulation of transcription from | 47 | 3.65×10−25 | HEY2, CRY1, WT1, LPIN1, BMP2 … |

| RNA polymerase II promoter | |||

| Positive regulation of transcription from | 51 | 2.48×10−22 | CIITA, FOXO1, TP53BP1, DDX5, HEY2 … |

| RNA polymerase II promoter | |||

| Positive regulation of transcription, | 40 | 1.54×10−19 | EBF1, MED17, SOX7, IRF7, SOX4 … |

| DNA-dependent | |||

| Negative regulation of transcription, | 35 | 1.12×10−16 | PTPRK, ZNF423, SMARCA4, FOXO1, IFI16 … |

| DNA-dependent | |||

| Cell adhesion | 31 | 3.18×10−13 | PRKD2, ADA, NID2, PNN, FAT1 … |

| Apoptotic process | 35 | 9.38×10−12 | TIAM1, CASP7, CASP7, BMF, KANK2 … |

| Nervous system development | 23 | 1.54×10−11 | NRN1, ARHGEF7, SEMA6A, NOG, DPYSL2 … |

| Antigen processing and presentation of peptide or polysaccharide antigen via MHC class II | 7 | 2.61×10−11 | HLA-DMB, HLA-DPA1, HLA-DQB1, HLA-DPB1, HLA-DMA … |

GO, Gene Ontology; DEGs, differentially expressed genes.

KEGG enrichment analysis revealed that upregulated DEG profiles were significantly enriched in 166 KEGG pathways, including metabolic pathways (P=1.10×10−43), cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction (P=5.71×10−31), osteoclast differentiation (P=4.96×10−30), phagosome (P=1.69×10−29) and lysosome (P=1.72×10−27). Downregulated DEGs were significantly enriched in 90 KEGG terms, such as pathways in cancer (P=2.33×10−12), systemic lupus erythematous (P=8.32×10−12), cell adhesion molecules (CAMs) (P=2.29×10−10), aldosterone synthesis and secretion (P=2.34×10−9) and HTLV-1 infection (P=5.94×10−9; Table II). Profile 26, which exhibited continuous increase, was significantly enriched in the following GO terms: Signal transduction (P=9.64×10−25), small molecule metabolic process (P=2.58×10−22), blood coagulation (P=2.73×10-21), etc.; and the following KEGG pathways: Metabolic pathways (P=3.33×10−18), lysosome (P=6.37×10−17), TNF signaling pathway (P=3.27×10−11), etc. (Table III). The continuously decreasing Profile 1 was significantly enriched in the following GO terms: Transcription DNA-dependent (P=1.74×10−28), regulation of transcription, DNA-dependent (P=8.48×10−20), negative regulation of transcription from RNA polymerase II promoter (P=1.34×10−17), etc.; and the following KEGG pathways: cGMP-PKG signaling pathway (P=1.88×10−7), Rap1 signaling pathway (P=1.65×10−6), glutamatergic synapse (P=1.69×10−5), etc. (Table III).

Table II.

The top 10 enriched KEGG pathways of upregulated and downregulated DEG profiles.

| A, Upregulated DEGs | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| KEGG pathway | Gene count | P-value | Genes |

| Metabolic pathways | 132 | 1.10×10−43 | CES1, B3GALNT1, NMNAT3, NNMT, GALNT6 … |

| Cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction | 53 | 5.71×10−31 | CCR1, XCL1, CXCL10, PF4, IL15 … |

| Osteoclast differentiation | 39 | 4.96×10−30 | NCF2, FCGR1A, SIRPB1, FCGR2A, MAP2K6 … |

| Phagosome | 41 | 1.69×10−29 | CYBB, ACTB, ITGB5, FCAR, FCGR1A … |

| Lysosome | 36 | 1.72×10−27 | ARSB, PPT1, CTSC, CD63, CLTCL1 … |

| Hematopoietic cell lineage | 29 | 3.94×10−24 | GP1BB, ITGA2B, CD3E, IL1R1, CD33 … |

| TNF signaling pathway | 31 | 3.10×10−23 | CEBPB, JAG1, VCAM1, NOD2, CREB5 … |

| Natural killer cell mediated cytotoxicity | 33 | 1.26×10−22 | PRF1, KIR2DS5, FCGR3B, TYROBP, CD244 … |

| Chemokine signaling pathway | 37 | 1.08×10−21 | PIK3CB, PAK1, PRKCD, STAT3, CXCL10 … |

| Tuberculosis | 35 | 1.47×10−20 | VDR, TLR2, FCGR2B, MAPK1, CD14 … |

| B, Downregulated DEGs | |||

| KEGG pathway | Gene count | P-value | Genes |

| Pathways in cancer | 28 | 2.33×10−12 | ADCY9, GNA11, FZD8, GNAI1, GNAS … |

| Systemic lupus erythematous | 17 | 8.32×10−12 | HIST1H2AD, HIST1H2BG, HIST1H2AE, HIST1H2BF, HIST2H4A … |

| Cell adhesion molecules (CAMs) | 16 | 2.29×10−10 | SDC2, CD22, HLA-DMB, MPZL1, HLA-DPA1 … |

| Aldosterone synthesis and secretion | 12 | 2.34×10−09 | CAMK1D, KCNK3, PRKCE, GNAS, ADCY6 … |

| HTLV-I infection | 19 | 5.94×10−09 | HLA-DRB1, TCF3, HLA-DOA, HLA-DQB1, HLA-DPB1 … |

| Transcriptional misregulation in cancer | 16 | 7.25×10−09 | FOXO1, MEF2C, WT1, SUPT3H, MDM2 … |

| Asthma | 8 | 1.31×10−08 | HLA-DQA1, HLA-DPB1, HLA-DPA1, HLA-DMB, HLA-DRB1 … |

| Toxoplasmosis | 13 | 1.90×10−08 | HLA-DMB, HLA-DPB1, HLA-DRB1, PIK3R3, HLA-DMA … |

| cGMP-PKG signaling pathway | 15 | 2.17×10−08 | ADCY6, KCNMB4, GNAI1, MEF2C, MEF2D … |

| Intestinal immune network for IgA production | 9 | 3.21×10−08 | HLA-DQA1, HLA-DMA, HLA-DMB, HLA-DQB1, HLA-DPB1 … |

KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; DEGs, differentially expressed genes.

Table III.

Top 5 GO and KEGG enrichment analyses results of Profile 26 and Profile 1.

| A, GO term | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Profile | Gene count | P-value | Genes |

| Profile 26 | |||

| Signal transduction | 52 | 9.64×10−25 | ALCAM, CAP1, C5AR1, TANK, CXCL1 … |

| Small molecule metabolic process | 56 | 2.58×10−22 | NAMPT, PDK3, HAL, GPI, ARSG … |

| Blood coagulation | 34 | 2.73×10−21 | ITPR2, JAK2, ACTN1, VEGFA, P2RY1 … |

| Inflammatory response | 25 | 2.41×10−17 | TLR8, TNFAIP6, CXCR2, IL18, KIT … |

| Innate immune response | 31 | 3.59×10−16 | KIT, CLEC7A, EREG, DEFA4, CAPZA2 … |

| Profile 1 | |||

| Transcription, DNA-dependent | 61 | 1.74×10−28 | KANK2, DIDO1, ZNF251, ZBTB10, PATZ1 … |

| Regulation of transcription, DNA-dependent | 43 | 8.48×10−20 | ZNF555, ZIK1, PATZ1, ZBTB10, ZNF514 … |

| Negative regulation of transcription from | 27 | 1.34×10−17 | SORBS3, ZNF8, YBX3, KDM2B, ID3 … |

| RNA Polymerase II promoter | |||

| Positive regulation of transcription, | 23 | 6.16×10−14 | GLI3, ZNF423, KAT6B, IRF, PHB … |

| DNA-dependent | |||

| Negative regulation of transcription, | 21 | 7.95×10−13 | HIC2, MAGED1, BRD7, KAT6B, RASD1 … |

| DNA-dependent | |||

| B, KEGG pathways | |||

| Profile | Gene count | P-value | Genes |

| Profile 26 | |||

| Metabolic pathways | 48 | 3.33×10−18 | AGL, GALNT3, B3GNT5, ALDH2, SCP2 … |

| Lysosome | 18 | 6.37×10−17 | CTSG, PPT1, CD164, CTSS, IGF2R … |

| TNF signaling pathway | 13 | 3.27×10−11 | PTGS2, CREB5, MAP3K5, CXCL5, MLKL … |

| Phagosome | 14 | 1.72×10−10 | CTSS, FCAR, CLEC7A, MPO, TUBA4A … |

| Cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction | 17 | 4.12×10−10 | IL17RA, CSF2RA, CSF3R, CXCL3, TNFSF13B … |

| Profile 1 | |||

| cGMP-PKG signaling pathway | 10 | 1.88×10−07 | MEF2D, MEF2C, GNA12, ADCY9, PIK3R3 … |

| Rap1 signaling pathway | 10 | 1.65×10−06 | PARD3, PIK3R3, FLT4, MLLT4, MAGI2 … |

| Glutamatergic synapse | 7 | 1.69×10−05 | GNG7, CACNA1A, ADCY9, SHANK3, PPP3CC … |

| Purine metabolism | 8 | 3.25×10−05 | ADCY6, NPR1, ADPRM, NUDT5, PDE8B … |

| Pathways in cancer | 11 | 7.73×10−05 | LAMC1, PIK3R3, GLI3, BCR, ADCY6 … |

DEG, differentially expressed genes; GO, Gene Ontology; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes.

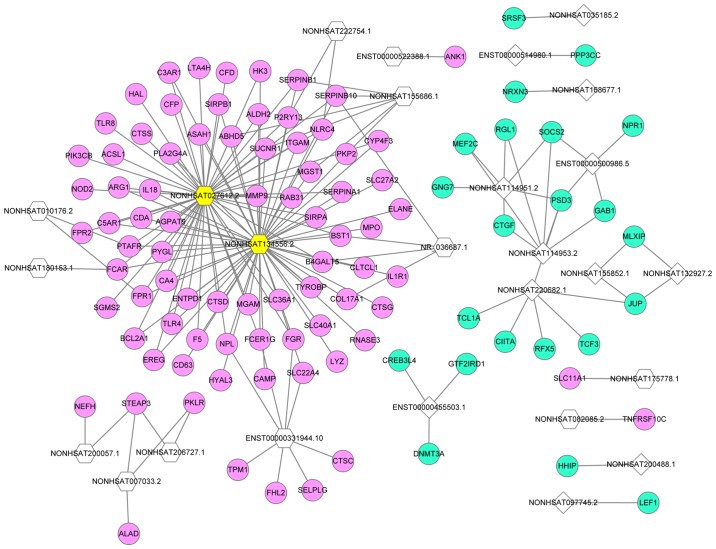

LncRNA-mRNA network

A lncRNA-mRNA network of overlapping lncRNAs and mRNAs was constructed based on the calculation of dynamic simulations (Fig. 3). This network comprised 26 lncRNAs and 103 mRNAs with 179 interaction pairs. NONHSAT134556.2 was the lncRNA with the highest regulatory capability (degree=58), followed by NONHSAT027612.2 (degree=54). The top five target DEGs of lncRNAs were pleckstrin and Sec7 domain containing 3 (degree=4), serpin family B member 10 (degree=4), STEAP3 metalloreductase (degree=3), succinate receptor 1 (degree=3) and microsomal glutathione S-transferase 1 (degree=3).

Figure 3.

LncRNA-mRNA network. Pink circles represent upregulated DEGs, blue circles represent downregulated DEGs and yellow hexagons represent the top two lncRNAs. Hexagons represent upregulated lncRNAs, and quadrangles represent downregulated lncRNAs. lncRNAs, long non-coding RNA; DEG, differentially expressed gene.

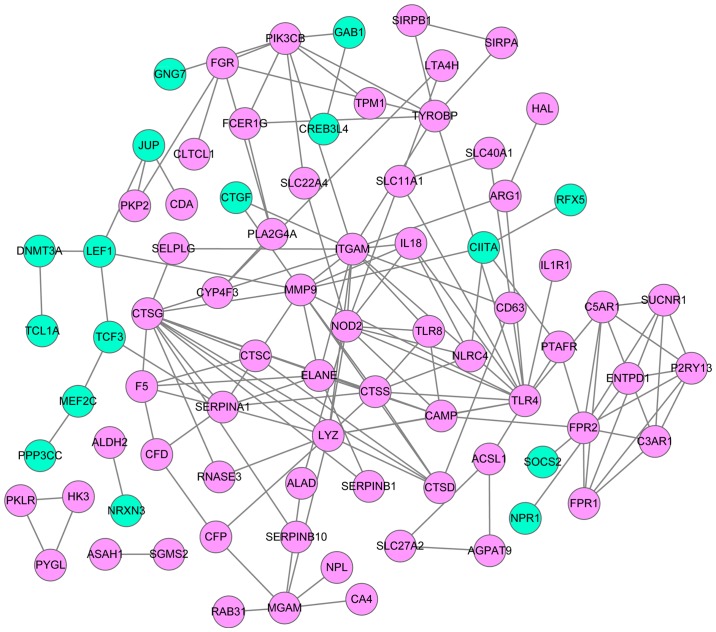

PPI network

Based on the lncRNA-mRNA network, mRNAs were selected to construct a PPI network using the STRING database (Fig. 4). This network comprised 80 mRNA-coded proteins and 147 interaction pairs. The top 10 hub nodes of this network were Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) (degree=15), integrin subunit αM (degree=14), cathepsin G (CTSG) (degree=13), lysozyme (degree=11), matrix metallopeptidase 9 (MMP9) (degree=11), nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-containing 2 (NOD2) (degree=10), cathepsin S (CTSS) (degree=8), formyl peptide receptor 1 (FPR1) (degree=8), phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit β (degree=8) and serpin family A member 1 (degree=8).

Figure 4.

Protein-protein interaction network. Red circles represent upregulated DEGs, and green circles represent downregulated DEGs. DEGs, differentially expressed genes.

Validation of DELs

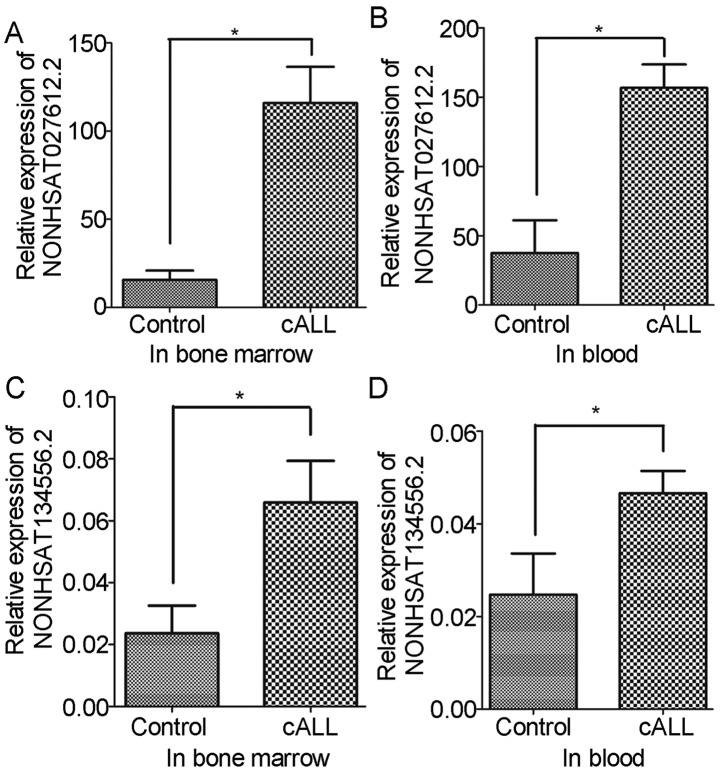

To confirm the present findings, variations in the expression levels of NONHSAT027612.2 and NONHSAT134556.2 were verified in the blood and bone marrow of patients with cALL. The results revealed that the expression levels of NONHSAT027612.2 and NONHSAT134556.2 were significantly increased in blood and bone marrow samples of patients with cALL compared with in the control samples (Fig. 5). These verifications were consistent with the results obtained from bioinformatics analysis.

Figure 5.

Validation of long non-coding RNAs expression using reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction. (A) Expression of NONHSAT027612.2 in bone marrow samples; (B) expression of NONHSAT027612.2 in blood samples; (C) expression of NONHSAT134556.2 in bone marrow samples; and (D) expression of NONHSAT134556.2 in blood samples. cALL, childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. *P<0.05 (compared with the control group).

Discussion

In the current study, the gene dataset GSE67684 was re-analyzed, and 593 DEGs and 21 DELs were identified that varied over time post-diagnosis of cALL. Among the clustered DEGs, Profile 26 presented a tendency to increase across all time points, whereas Profile 1 tended to decrease over the same interval. GO enrichment analysis revealed that Profiles 26 and 1 were significantly enriched in immune response (GO:0006955, immune response; GO:0045087, innate immune response) and proliferation-associated biological (GO:0050680, negative regulation of epithelial cell proliferation) processes, respectively. In addition, the lncRNAs NONHSAT027612.2 and NONHSAT134556.2 were revealed to be significantly upregulated in cALL and could regulate most upregulated DEGs identified in this study.

Previous studies have reported that lncRNAs exhibit a wide array of regulatory effects on gene expression (21,22). The lncRNAs NONHSAT027612.2 and NONHSAT134556.2, which are newly identified lncRNAs, are located on chromosomes 12 and 9, respectively. At present, to the best of our knowledge, only sequencing of their expression levels in tissues has been reported (http://www.noncode.org/). In the present study, the lncRNAs NONHSAT027612.2 and NONHSAT134556.2 were significantly elevated in cALL samples compared with in control blood and bone marrow samples. Further analysis demonstrated that NONHSAT027612.2 directly upregulated the expression levels of TLR4 and its regulator, NOD2. In addition, NONHSAT134556.2 directly upregulated the expression of TLR4. TLR4 and NOD2 are key genes involved in innate immunity (23); they were both identified in this study and are expected to interact with each other. Previous studies have demonstrated that TLR4 promotes B-cell maturation (24), and that TLR4 polymorphisms are associated with neutropenia development in cALL (25). He et al also reported that TLR4 signaling promotes immune-escape evasion in human pulmonary cancer cells by inducing apoptosis resistance and immunosuppressive cytokine expression (26). Furthermore, TLR4 stimulation induces delayed activation of the nuclear factor-κB subunit Rel A (27), which is reported to serve a crucial role in in vitro survival and clinical progression of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (28). Chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells are unresponsive to TLR4 and TLR8 stimulation (29), which may explain the upregulation of TLR4 and TLR8 in cALL observed in the present study. Whether a feedback mechanism exists between TLR4 and the response of chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells requires further investigation. As important regulators of TLRs, NOD2 polymorphisms are also associated with increased relapse and mortality rates in patients with ALL who have undergone hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation (30). NOD2 is an intracellular protein that recognizes bacterial peptidoglycans. This protein is widely expressed in cells, including B cells, in which interaction among TLRs occurs (31). In the current study, NOD2 was revealed to interact with TLR4 and TLR8, and its expression was significantly enriched in the innate immune response and TLR signaling pathways. Muzio et al demonstrated that NOD2 and other TLR ligands, particularly TLR1/2 and TLR6/2, induce the activation of chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells via induction of IκB kinase phosphorylation and elevation of the expression of cluster of differentiation (CD) 25 and CD86 (32). Furthermore, NOD2 is functionally relevant in regulatory T cells and inhibits Fas-mediated apoptosis in T cells (33). However, a deeper understanding of the signal transduction and interaction between TLR4 and NOD2 in cALL remains to be established.

CTSG and CTSS are genes coding for the proteins cathepsin G and cathepsin S, which belong to the cathepsin family (34), and are involved in the immune response. CTSG and CTSS were revealed to be upregulated by lncRNAs NONHSAT134556.2 and NONHSAT027612.2, respectively. Chang et al reported that the expression of CTSG is significantly downregulated, alongside interleukin-6 (IL-6), IL-8, IL-12 and B-cell lymphoma 2 in HT1080 cells via tilapia hepcidin 1–5, which is an antimicrobial peptide that possesses potential anticancer activity (35). Zöller (36) suggested out that CTSG and MMP9-activated transforming growth factor-β contribute to bone resorption and niche preparation for cancer-initiating cells. Other studies have suggested that CTSG is activated by various classes of proteinases, such as MMPs or serine/cysteine proteinases, during the development of human disease (37). These observations indicated that CTSG serves a positive role in carcinogenesis. In agreement with the present observations, CTSS expression is elevated in pancreatic cancer and results in the production of γ2 peptide, which is an important molecule involved in cell adhesion, migration and metastasis during carcinogenesis (38,39). CTSS is also involved in protumorigenic activities during intestinal carcinogenesis (40). Other studies have documented that CTSS has an important role in the migration and invasion of gastric cancer cells via a network of metastasis-associated proteins (41). Taken together, these findings indicated that CTSG and CTSS may have important roles in tumorigenesis and could serve as potential targets for tumor treatment. However, the underlying mechanisms of CTSG and CTSS in cALL remain unknown and warrant further analysis.

Although this study revealed some interesting results, it also presented some limitations. Firstly, the majority of results were identified in silico; therefore, further experimental validation is required. Secondly, the parameters used were set manually; therefore, some genes may have been ignored due to thresholds. Thirdly, although the study validated the findings, the expression levels of NONHSAT134556.2 and NONHSAT134556.2 were not consistent with their degree in the regulatory network; therefore, a larger sample size will be required in further studies. Finally, due to limited resources, not enough cALL samples at Day 0 were collected; therefore blood samples from healthy subjects were collected instead and used as controls in the present study, which could induce a bias. Considering these limitations, we aim to further confirm these findings using cALL samples collected from patients at Day 0 as controls as soon as enough samples are collected.

In conclusion, the expression levels of the lncRNAs NONHSAT027612.2 and NONHSAT134556.2 were significantly increased in patients with cALL, and may serve as potential regulators for the pathogenesis of cALL. From these two lncRNAs, TLR4, NOD2, CTSG and CTSS may be potential gene targets, and may promote development of cALL via immune response-associated biological processes.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 30872804, 81170661 and 31640048 to GPZ) and Jiangsu Province Science and Education Enhancing Health Project Innovation Team (Leading Talent) Program (no. CXTDA2017018 to GPZ).

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Authors' contributions

GZ and YF conceived and designed the study. SL and HB performed the data analysis and wrote the manuscript. YC identified the DEGs and DELs. CJ performed the GO analysis, KEGG pathway analysis and PPI analysis. QC performed the RT-qPCR. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the First Hospital of Nanjing Medical University approved this study. Informed consent was obtained from the subjects' parents.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Roberts KG, Li Y, Payne-Turner D, Harvey RC, Yang YL, Pei D, McCastlain K, Ding L, Lu C, Song G, et al. Targetable kinase-activating lesions in Ph-like acute lymphoblastic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:1005–1015. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1403088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stock W. Adolescents and young adults with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2010;2010:21–29. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2010.1.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hunger SP, Lu X, Devidas M, Camitta BM, Gaynon PS, Winick NJ, Reaman GH, Carroll WL. Improved survival for children and adolescents with acute lymphoblastic leukemia between 1990 and 2005: A report from the children's oncology group. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1663–1669. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.37.8018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hoelzer D. Treatment of acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Semin Hematol. 1994;31:1–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eapen M, Zhang MJ, Devidas M, Raetz E, Barredo JC, Ritchey AK, Godder K, Grupp S, Lewis VA, Malloy K, et al. Outcomes after HLA-matched sibling transplantation or chemotherapy in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia in a second remission after an isolated central nervous system relapse: A collaborative study of the Children's Oncology Group and the center for international blood and marrow transplant research. Leukemia. 2008;22:281–286. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2405037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liz J, Esteller M. lncRNAs and microRNAs with a role in cancer development. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2016;1859:169–176. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2015.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhou X, Ye F, Yin C, Zhuang Y, Yue G, Zhang G. The Interaction between MiR-141 and lncRNA-H19 in regulating cell proliferation and migration in gastric cancer. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2015;36:1440–1452. doi: 10.1159/000430309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fang Z, Wu L, Wang L, Yang Y, Meng Y, Yang H. Increased expression of the long non-coding RNA UCA1 in tongue squamous cell carcinomas: A possible correlation with cancer metastasis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2014;117:89–95. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2013.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shi SJ, Wang LJ, Yu B, Li YH, Jin Y, Bai XZ. LncRNA-ATB promotes trastuzumab resistance and invasion-metastasis cascade in breast cancer. Oncotarget. 2015;6:11652–11663. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang K, Long B, Zhou LY, Liu F, Zhou QY, Liu CY, Fan YY, Li PF. CARL lncRNA inhibits anoxia-induced mitochondrial fission and apoptosis in cardiomyocytes by impairing miR-539-dependent PHB2 downregulation. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3596. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ding C, Yang Z, Lv Z, DU C, Xiao H, Peng C, Cheng S, Xie H, Zhou L, Wu J, Zheng S. Long non-coding RNA PVT1 Is associated with tumor progression and predicts recurrence in hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Oncol Lett. 2015;9:955–963. doi: 10.3892/ol.2014.2730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fang K, Han BW, Chen ZH, Lin KY, Zeng CW, Li XJ, Li JH, Luo XQ, Chen YQ. A distinct set of long non-coding RNAs in childhood MLL-rearranged acute lymphoblastic leukemia: Biology and epigenetic target. Hum Mol Genet. 2014;23:3278–3288. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddu040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Trimarchi T, Bilal E, Ntziachristos P, Fabbri G, Dalla-Favera R, Tsirigos A, Aifantis I. Genome-wide mapping and characterization of Notch-regulated long noncoding RNAs in acute leukemia. Cell. 2014;158:593–606. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.05.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang Y, Wu P, Lin R, Rong L, Xue Y, Fang Y. LncRNA NALT interaction with NOTCH1 promoted cell proliferation in pediatric T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Sci Rep. 2015;5:13749. doi: 10.1038/srep13749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yeoh A, Li ZH, Dong DF, Lu Y, Jiang N, Trka J, Tan AM, Lin HP, Quah TC, Ariffin H, Wong L. Effective response metric: A novel tool to predict relapse in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia using time-series gene expression profiling. Br J Haematol. 2018;181:653–663. doi: 10.1111/bjh.15252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miao MH, Ji XQ, Zhang H, Xu J, Zhu H, Shao XJ. miR-590 promotes cell proliferation and invasion in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia by inhibiting RB1. Oncotarget. 2016;7:39527–39534. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.8414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miller LD, Long PM, Wong L, Mukherjee S, Mcshane LM, Liu ET. Optimal gene expression analysis by microarrays. Cancer Cell. 2002;2:353–361. doi: 10.1016/S1535-6108(02)00181-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ramoni MF, Sebastiani P, Kohane IS. Cluster analysis of gene expression dynamics. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:9121–9126. doi: 10.1073/pnas.132656399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang CF, Zhao CC, Weng WJ, Lei J, Lin Y, Mao Q, Gao GY, Feng JF, Jiang JY. Alteration in long non-coding RNA expression after traumatic brain injury in rats. J Neurotrauma. 2017;34:2100–2108. doi: 10.1089/neu.2016.4642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Monnier P, Martinet C, Pontis J, Stancheva I, Ait-Si-Ali S, Dandolo L. H19 lncRNA controls gene expression of the Imprinted Gene Network by recruiting MBD1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:20693–20698. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1310201110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nie L, Wu HJ, Hsu JM, Chang SS, Labaff AM, Li CW, Wang Y, Hsu JL, Hung MC. Long non-coding RNAs: Versatile master regulators of gene expression and crucial players in cancer. Am J Transl Res. 2012;4:127–150. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mrózek K, Radmacher MD, Bloomfield CD, Marcucci G. Molecular signatures in acute myeloid leukemia. Curr Opin Hematol. 2009;16:64–69. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0b013e3283257b42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hayashi EA, Akira S, Nobrega A. Role of TLR in B cell development: Signaling through TLR4 promotes B cell maturation and is inhibited by TLR2. J Immunol. 2005;174:6639–6647. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.11.6639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miedema KG, te Poele EM, Tissing WJ, Postma DS, Koppelman GH, de Pagter AP, Kamps WA, Alizadeh BZ, Boezen HM, de Bont ES. Association of polymorphisms in the TLR4 gene with the risk of developing neutropenia in children with leukemia. Leukemia. 2011;25:995–1000. doi: 10.1038/leu.2011.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.He W, Liu Q, Wang L, Chen W, Li N, Cao X. TLR4 signaling promotes immune escape of human lung cancer cells by inducing immunosuppressive cytokines and apoptosis resistance. Mol Immunol. 2007;44:2850–2859. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2007.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McGettrick AF, O'Neill LA. Toll-like receptors: Key activators of leucocytes and regulator of haematopoiesis. Br J Haematol. 2007;139:185–193. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2007.06802.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hewamana S, Alghazal S, Lin TT, Clement M, Jenkins C, Guzman ML, Jordan CT, Neelakantan S, Crooks PA, Burnett AK, et al. The NF-kappaB subunit Rel A is associated with in vitro survival and clinical disease progression in chronic lymphocytic leukemia and represents a promising therapeutic target. Blood. 2008;111:4681–4689. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-11-125278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ntoufa S, Vardi A, Papakonstantinou N, Anagnostopoulos A, Aleporou-Marinou V, Belessi C, Ghia P, Caligaris-Cappio F, Muzio M, Stamatopoulos K. Distinct innate immunity pathways to activation and tolerance in subgroups of chronic lymphocytic leukemia with distinct immunoglobulin receptors. Mol Med. 2012;18:1281–1291. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2011.00480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mayor NP, Shaw BE, Hughes DA, Maldonado-Torres H, Madrigal JA, Keshav S, Marsh SG. Single nucleotide polymorphisms in the NOD2/CARD15 gene are associated with an increased risk of relapse and death for patients with acute leukemia after hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation with unrelated donors. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:4262–4269. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.1897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Muzio M, Fonte E, Caligaris-Cappio F. Toll-like receptors in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis. 2012;4:e2012055. doi: 10.4084/mjhid.2012.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Muzio M, Scielzo C, Bertilaccio MT, Frenquelli M, Ghia P, Caligaris-Cappio F. Expression and function of toll like receptors in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia cells. Br J Haematol. 2009;144:507–516. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07475.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rahman MK, Midtling EH, Svingen PA, Xiong Y, Bell MP, Tung J, Smyrk T, Egan LJ, Faubion WA., Jr The pathogen recognition receptor NOD2 regulates human FOXP3+ T cell survival. J Immunol. 2010;184:7247–7256. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gomes S, Marques PI, Matthiesen R, Seixas S. Adaptive evolution and divergence of SERPINB3: A young duplicate in great Apes. PLoS One. 2014;9:e104935. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0104935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chang WT, Pan CY, Rajanbabu V, Cheng CW, Chen JY. Tilapia (Oreochromis mossambicus) antimicrobial peptide, hepcidin 1–5, shows antitumor activity in cancer cells. Peptides. 2011;32:342–352. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2010.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zöller M. CD44: Can a cancer-initiating cell profit from an abundantly expressed molecule? Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11:254–267. doi: 10.1038/nrc3023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Korkmaz B, Horwitz MS, Jenne DE, Gauthier F. Neutrophil elastase, proteinase 3 and cathepsin G as therapeutic targets in human diseases. Pharmacol Rev. 2010;62:726–759. doi: 10.1124/pr.110.002733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gocheva V, Zeng W, Ke D, Klimstra D, Reinheckel T, Peters C, Hanahan D, Joyce JA. Distinct roles for cysteine cathepsin genes in multistage tumorigenesis. Genes Dev. 2006;20:543–556. doi: 10.1101/gad.1407406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang B, Sun J, Kitamoto S, Yang M, Grubb A, Chapman HA, Kalluri R, Shi GP. Cathepsin S controls angiogenesis and tumor growth via matrix-derived angiogenic factors. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:6020–6029. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509134200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gounaris E, Tung CH, Restaino C, Maehr R, Kohler R, Joyce JA, Ploegh HL, Barrett TA, Weissleder R, Khazaie K. Live imaging of cysteine-cathepsin activity reveals dynamics of focal inflammation, angiogenesis and polyp growth. PLoS One. 2008;3:e2916. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yang Y, Lim SK, Choong LY, Lee H, Chen Y, Chong PK, Ashktorab H, Wang TT, Salto-Tellez M, Yeoh KG, Lim YP. Cathepsin S mediates gastric cancer cell migration and invasion via a putative network of metastasis-associated proteins. J Proteome Res. 2010;9:4767–4778. doi: 10.1021/pr101027g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.