Abstract

Recent studies have reported that metformin (Met), the first-line medication for the treatment of type 2 diabetes, exhibited anticancer and chemoprotective effects in diverse cancer cells. In this study, we investigated the effects of Met on the drug-resistance of 4T1 murine breast cancer tumorspheres (TS) and the mechanism responsible for its drug-resistance. 4T1 TS exhibited accumulations of cells at the G0/G1 phase compared with cells in monolayer culture, which suggested the majority of cells in TS were quiescent. Furthermore, it was identified that activations of the signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) and protein kinase B (AKT) signaling pathways in 4T1 TS conferred drug-resistance to doxorubicin (Dox) and lapatinib (Lapa). However, Met selectively targeted TS rather than cells in monolayer culture and increased the cytotoxic effect of Dox on TS by inhibiting activations of the STAT3 and AKT signaling pathways. These observations suggested that inhibitions of STAT3 and AKT underlie the selective cytotoxic effects of Met on TS. In addition, Met exhibited synergistic antitumor effects with Dox on 4T1 tumor-bearing BALB/c mice. Our findings suggest that combinations of Met and cytotoxic anticancer drugs may offer an advantage for treating drug-resistant breast cancer.

Keywords: drug-resistance, metformin, quiescence, tumorspheres, 4T1 breast cancer cells

Introduction

Metformin (Met) has long been used to treat type 2 diabetes; its principle activities have been characterized as the inhibition of hepatic glucose output and increased glucose uptake by muscle (1). However, Met has recently attracted attention as a potential treatment for cancer due to its strong anticancer effects (2). Evans et al found that the use of Met by type 2 diabetic patients was associated with a lower cancer incidence (3). In addition, cancer-related mortality found to be lower in patients treated with Met than in those treated with other anti-diabetic drugs (3,4). Following these impressive epidemiological studies, preclinical studies revealed Met inhibited cancer cell growth (2,5,6), and induced apoptotic cell death in diverse solid cancers, including colon (7), ovarian (8), and breast cancers (5,9). It is widely accepted that inhibition of PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway via AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) activation underlies the anticancer activities of Met (10). More recently, several studies have reported that Met selectively targets cancer stem cells (CSCs), which are responsible for tumor growth and failures to respond to chemotherapy and radiotherapy (11).

Regarding breast cancer, Hirsch et al showed that Met preferentially reduces the CSC fraction (12), as defined by CD44high/CD24low expression (12). Since CSCs have known to grow as tumorspheres (TS) when incubated under non-adherent conditions (13–15), they also showed that Met suppresses the number and sizes of TS derived from several breast cancer cell lines (12). Similarly, other studies have also reported that Met significantly reduced TS formation, and the expressions of CSC markers, such as, those of CD44high/CD24low, ALDH-1, or OCT4 in breast cancer cells (16–18). Several mechanisms have been proposed for the targeting of CSCs by Met, including the regulation of epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT) (19), the suppressions of transcription factors like TGFβ (20), and inactivation of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway (18,21). However, the mechanism responsible for the selective targeting of CSCs by Met remains to be elucidated.

Previously, we showed that TS cultures increased the quiescent nature of cells, which is a known characteristic of CSCs (22–24). After optimizing TS cultures to screen cytotoxic agents in vitro (23), we found that TS derived from breast cancer cells are resistant to drugs commonly used for chemotherapy (22–24). Thus, in this study, we utilized TS cultures to investigate whether Met has the potential to overcome the drug-resistance of TS generated from 4T1 murine breast cancer cells and to elucidate the underlying mechanism.

Materials and methods

Monolayer culture

4T1 murine breast cancer cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA) and maintained in DMEM (Welgene, Daegu, Korea) supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum (Hyclone Laboratories Inc, South Logan, UT, USA) and 1% antibiotics antimycotic solution (Welgene).

TS culture

The protocol used for TS culture was as previously described (22,24). In brief, 4T1 cells were suspended in serum-free DMEM/F12 (Welgene) supplemented with 1X B27 (Gibco BRL, Grand Island, NY, USA), 20 ng/ml recombinant human EGF (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA), 10 ng/ml recombinant human FGF (R&D Systems), 10 µg/ml insulin (Welgene), 10 mM HEPES (Welgene) and 1% antibiotics antimycotic solution (Welgene) and cultured in non-adherent plates.

Cell kinetic assay

4T1 cells were seeded into 96-well plates at a density of 1,000 to 16,000 cells per well and incubated for 4 days under monolayer or TS culture conditions. To quantify the number of cells premixed cell proliferation reagent WST-8 (Dojindo Laboratories, Kumamoto, Japan) was added to each well and the absorbance of the water-soluble formazan produced by viable cells was measured at 450 nm according to the manufacturer's protocol.

In vitro response

To compare the chemosensitivities of monolayer and TS cultured cells, cells cultured in adherent or non-adherent 96-well plates were treated with various concentrations of doxorubicin (Dox) (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany), lapatinib (Lapa) (LC Laboratories, Woburn, MA, USA), or Met (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) for 3 days. Cell viabilities were determined using reagent WST-8.

Cell cycle analysis

4T1 cells were cultured under monolayer and TS culture conditions for 4 days, and trypsinized after washing with PBS. Cells were then centrifuged at 1,000 rpm for 3 min and fixed with cold 70% ethanol. After centrifugation once again, cells were washed with PBS containing 2% FBS prior to staining with 20 µg/ml propidium iodide (PI; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) and 200 µg/ml RNase A (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) for 30 min in the dark at room temperature. Cell cycle was assessed by analyzing the DNA contents stained with PI using a FACS Calibur II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA).

RNA isolation and reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (PCR)

Total RNA was extracted using the easy-BLUE™ Total RNA Extraction kit (iNtRON Biotechnology Inc., Sungnam, Korea). cDNA was synthesized using GoScript™ reverse transcriptase (Promega Corporation, Madison, WI, USA) and PCR was performed using Taq DNA polymerase (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA). The used primer sequences for PCR were as follows: Cyclin D1 (forward) 5′-CTGTGCGCCCTCCGTATCTTA-3′ and cyclin D1 (reverse) 5′-GGCGGCCAGGTTCCACTTGAG-3′; GAPDH (forward) 5′-ACCACAGTCCATGCCATCAC-3′ and GAPDH (reverse) 5′-TCCACCACCCTGTTGCTGTA-3′.

Western blotting

Cells grown as monolayers or TS were harvested and lysed with RIPA buffer (150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5 and 2 mM EDTA) supplemented with phosphatase and protease inhibitor cocktails (GenDepot, Barker, TX, USA). Lysates were centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 10 min to remove cell debris, and protein concentrations were determined using bicinchoninic acid reagent (Sigma). Same amounts of protein were separated by SDS-PAGE and then transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes, which were then blocked with 5% non-fat skim milk in 1X TBS-0.1% Tween-20 (TTBS) for 2 h and incubated with primary antibodies [protein kinase B (AKT), p-AKT, activator of transcription 3 (STAT3), p-STAT3, GAPDH (Cell Signaling, Beverly, MA, USA] or β-actin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Dallas, TX, USA). Blots were then incubated for 1 h at room temperature with HRP-conjugated secondary anti-rabbit antibody (Thermo Fisher Scientific) or anti-mouse antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc.) at 1:5,000 in TTBS, and developed using a Luminescent Image Analyzer LAS-4000 (Fujifilm, Tokyo, Japan).

In vivo responses

Four-week-old female BALB/c mice were purchased from Orient Bio Inc. (Sungnam, Korea) and allowed to acclimatize under a 12-h light/dark cycle at 25±2°C/RH 50±5% for two weeks before inoculation. 4T1 cells (1×105) were implanted into mammary fat pads and when tumor volumes reached ~100 mm3, mice were randomly allocated to one of the following four groups: a) Control, b) Dox, c) Met, d) Dox plus Met groups. Mice were intraperitoneally injected with Dox (5 mg/kg, once a week), Met (200 mg/kg, once a day), or both. Tumor sizes were measured every on alternate days with a digital caliper and volumes were calculated using the following formula; tumor volume (mm3)=(longest length + shortest length2)/2. To quantify tumor growth rate, we determined relative tumor volume to the averaged volume of starting tumor (0 day) for each group. Animal experimentation was performed after obtaining approval from the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Dongguk University (IACUC-2016-003).

Statistical analysis

Statistical significance was determined using the Student's t-test or one-way analysis of variance with Fisher's least significant difference as the post hoc test. All experiments were conducted in triplicates, and results are presented as the mean ± standard deviation.

Results

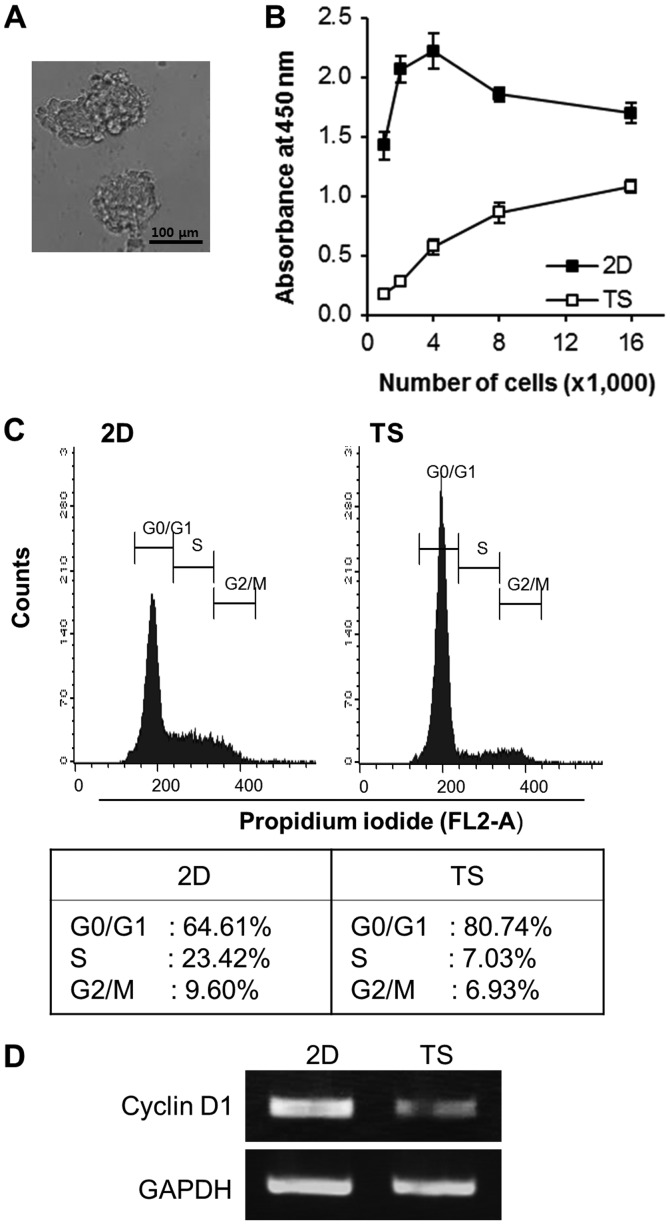

Quiescence in TS generated from 4T1 cells

We first tested the ability of 4T1 breast cancer cells to form TS by culturing them in non-adherent culture condition for 4 days. The cells successfully formed spheres of different sizes with a grape-like appearance (Fig. 1A). To compare cell growth rates in TS and monolayer cultures, various concentrations of cells (1,000-16,000 cells/well) were plated into 96-well non-adherent or regular tissue culture plates. After 4 days of culture, the premixed cell proliferation reagent, WST-8, was added to each plate and WST-8 absorbance at 450 nm was measured. As shown in Fig. 1B, overall WST-8 absorbance of TS was almost a forth of that of monolayer cultured cells, indicating the cell growth rate of TS was slower than that of monolayer cultured cells. Interestingly, over 80% of the cells in TS accumulated in the G0/G1 phase, whereas ~65% of monolayer cultured cells did so (Fig. 1C). Consistent with our cell cycle analysis results, the mRNA expression of cyclin D1 (an important regulator of G1 to S phase progression) was also decreased in TS (Fig. 1D). Taken together, these results suggest that TS culture conditions increase the proportion of cells in the quiescent state.

Figure 1.

Majority of cells in 4T1 TS are quiescent. (A) Images of TS generated from 4T1 cells. TS were cultured in non-adherent culture plates for 4 days. Scale bar, 100 µm. (B) TS exhibited slower cell proliferation rates than cells grown in monolayers (2D). Cell absorbances measured using WST-8 reagent after incubation for 4 days. (C) Cell cycle analysis of cells grown as 2D cultures or as TS showed accumulations of cells in the G0/G1 phase in TS. (D) mRNA expression of cyclin D1 was diminished in cells grown in TS. TS, tumorspheres.

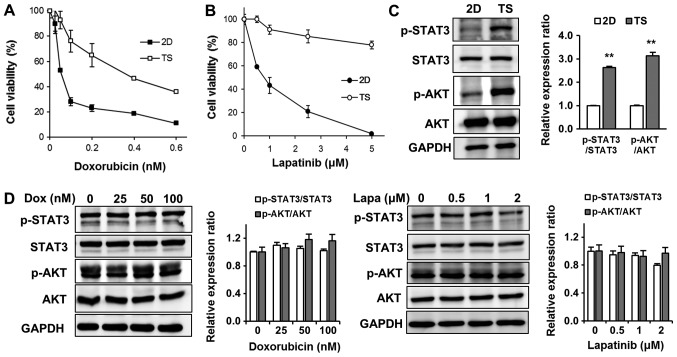

4T1 TS exhibited chemoresistance by upregulating the STAT3 and AKT signaling pathways

To determine whether TS quiescence was associated with chemoresistance, we tested cytotoxic effects of Dox on TS. We treated cells cultured as monolayers or TS with various concentrations of Dox (0.025–0.6 µM) for 3 days, and determined cell viabilities using WST-8. As shown in Fig. 2A, 4T1 cells cultured as monolayers were highly sensitive to Dox (IC50 0.05 µM), whereas most cells in TS survived at the same concentration (0.05 µM) and notably the IC50 for Dox was more than ten times higher (0.6 µM). Since 4T1 breast cancer cells are considered a triple negative breast cancer model and express epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), we also examined the effects of Lapa (a dual EGFR/HER2 inhibitor) on TS (Fig. 2B). Similar to effects of Dox, cells cultured as monolayers were highly sensitive to Lapa (IC50 1 µM), but over 80% of cells in TS survived at the highest concentrations tested (5 µM) (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

Resistances of 4T1 TS to Dox and Lapa are due to upregulation of the STAT3 and AKT signaling pathways. Chemotherapeutic responses to (A) Dox or (B) Lapa in 2D or TS cultured cells. After treatment with (A) Dox or (B) Lapa for 3 days, cell viabilities were assessed using WST-8 reagent. Results are the means of three independent experiments performed in triplicate. Error bars indicate the standard deviations of the mean. (C) Comparison of p-STAT3 and p-AKT expression levels in 2D or TS cultured cells as determined by western blot analysis. **P<0.01 vs. 2D. (D) Dox and Lapa had no inhibitory effects of p-STAT3 and p-AKT expression levels in TS cultured cells. Lapa, lapatinib; Dox, doxorubicin; STAT3, signal transducer and activator of transcription 3; AKT, protein kinase B; TS, tumorspheres; p, phosphorylated.

To elucidate the molecular mechanism responsible for the chemoresistance of TS, we first analyzed upregulated signaling pathways in the TS as compared with monolayer cultured cells. After checking several main signaling pathways known to regulate cell survival, proliferation, apoptosis, and chemoresistance, including the PI3K/AKT, MAPK/extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK), Bcl-2, and STAT3 pathways, we found the signal transducer and STAT3 and AKT signaling pathways were significantly more upregulated in TS than in monolayer cultured cells (Fig. 2C). However, interestingly, treatment with Dox or Lapa failed to inhibit enhanced STAT3 and AKT signaling observed in TS (Fig. 2D), indicating that these signaling pathways might play important roles in mediating TS chemoresistance.

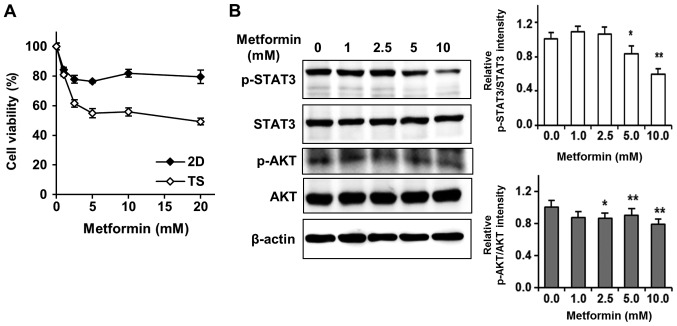

Met selectively targets TS rather than monolayer-cultured cells by inhibiting the STAT3 and AKT signaling pathways. Several studies have reported that Met dramatically reduces the sizes and numbers of TS in diverse cancer cell lines, including breast cancer, thyroid cancer, and hepatocellular carcinoma cells (16–18). Notably, Liu et al showed Met induced the death of triple-negative breast cancer cells in vitro and in vivo (9). Thus, we tested effects of Met on 4T1 TS to find out a new approach to overcome chemoresistance of TS. Surprisingly, we found that Met selectively targeted TS rather than monolayer-cultured cells (Fig. 3A). In stark contrast to effects of Dox or Lapa on TS, cell viability in TS treated with 5 mM Met was about 50%, whereas over 80% of cells cultured as monolayers survived treatment with 20 mM Met (Fig. 3A).

Figure 3.

Metformin selectively targets TS rather than 2D cultured cells. (A) Chemotherapeutic responses of 2D and TS cultured cells to metformin. After treatment with metformin for 3 days, cell viabilities were assessed using WST-8 reagent. Results represent three independent experiments performed in triplicate. Error bars indicate the standard deviations of the means. (B) Whole cell lysates of TS treated with metformin were analyzed by western blotting for p-STAT3 and p-AKT. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 vs. control (0 mM metformin). TS, tumorspheres; p, phosphorylated; STAT3, signal transducer and activator of transcription 3; AKT, protein kinase.

After finding STAT3 and AKT signaling pathway enhancements were responsible for the chemoresistance of TS, we tested whether Met affected the phosphorylation of STAT3 and AKT signaling pathways. As shown in Fig. 3B, Met efficiently and dose-dependently inhibited the phosphorylations of STAT3 and AKT, suggesting that Met selectively targeted TS by inhibiting the STAT3 and AKT signaling pathways.

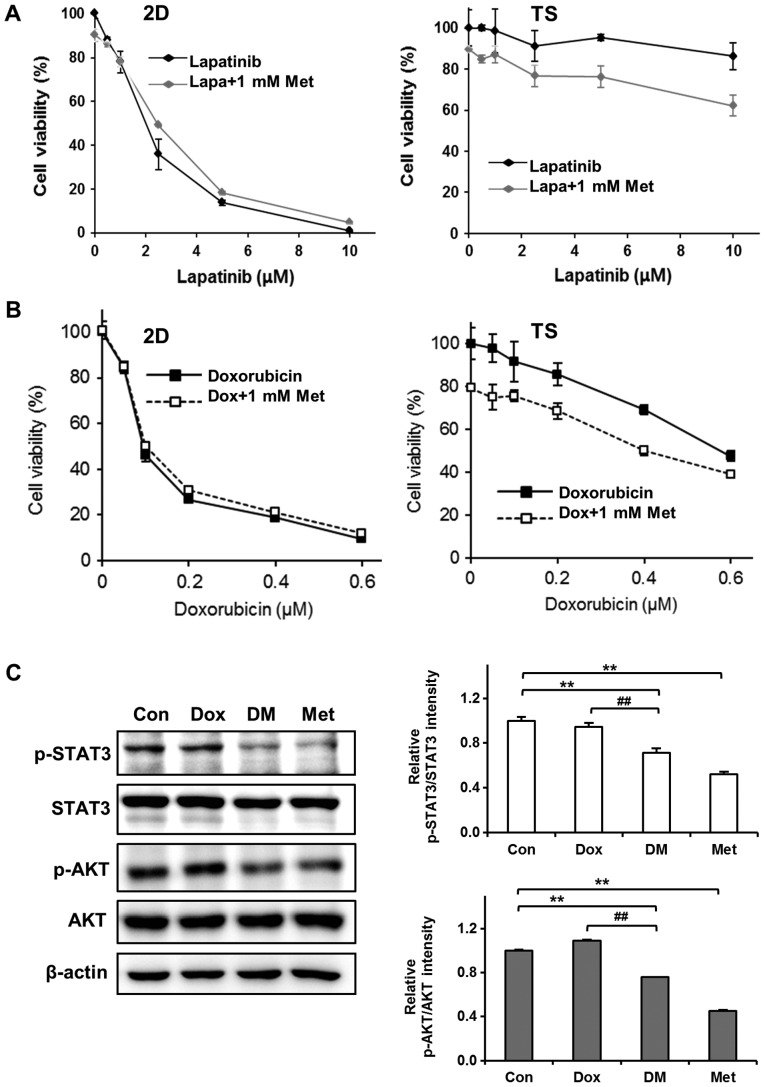

Met sensitizes 4T1 TS to Dox by inhibiting the STAT3 and AKT signaling pathways

Encouraged by the observation that Met selectively killed cells in 4T1 TS, we next examined the combined effects of Met and chemotherapeutic agents on 4T1 TS chemoresistance. Cells were treated with different concentrations of Lapa or Dox in presence of 1 mM Met for 3 days and cell viabilities was determined. Interestingly, Met exhibited synergistic effects with Lapa or Dox on TS but not on cells cultured as monolayers. As shown in Fig. 4A, treatment with Lapa and Met did not enhance the cytotoxicity of Lapa in monolayer cultured cells but significantly enhanced cytotoxicity in TS; for example, >90% cell viability observed after treating TS with 10 µM Lapa for 3 days, but this was reduced to almost 60% when cells were treated with 10 µM Lapa in the presence of 1 mM Met. Similarly, Met increased the cytotoxic effects of Dox by almost 20% in TS but no synergistic effect was observed in monolayer cultured cells (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4.

Met increases the cytotoxicity of Dox to TS by inhibiting the STAT3 and AKT signaling pathways. Synergistic cytotoxic effects of Met on (A) Lapa-treated TS cultured cells and (B) Dox-treated TS cultured cells. 4T1 cells were treated with various concentrations of Lapa or Dox in the presence of 1 mM Met for 3 days and viabilities were assessed using WST-8 reagent. Results represent three independent experiments performed in triplicate. Error bars represent the standard deviations of the means. (C) Inhibitory effect of Met on the expressions of p-STAT3 and p-AKT in Dox-treated TS. TS were treated with 0.5 µM Dox and/or 1 mM Met for 3 days and then western blotted. **P<0.01 vs. Con; ##P<0.01 vs. Dox group. STAT3, signal transducer and activator of transcription 3; AKT, protein kinase; TS, tumorspheres; Lapa, lapatinib; Dox, doxorubicin; Met, metformin; DM, doxorubicin+metformin; p, phosphorylated; Con, control.

To understand the mechanisms responsible for overcoming chemoresistance of TS by Met, we performed western blotting to investigate the effect of Dox plus Met on the phosphorylations of STAT3 and AKT in TS. As mentioned above (Fig. 2D), the phosphorylations of STAT3 and AKT in TS were not inhibited by Dox. However, co-treatment with Dox plus Met inhibited the phosphorylations of STAT3 and of AKT (Fig. 4C). These observations suggest that Met sensitizes TS to Dox by inhibiting the STAT3 and AKT signaling pathways.

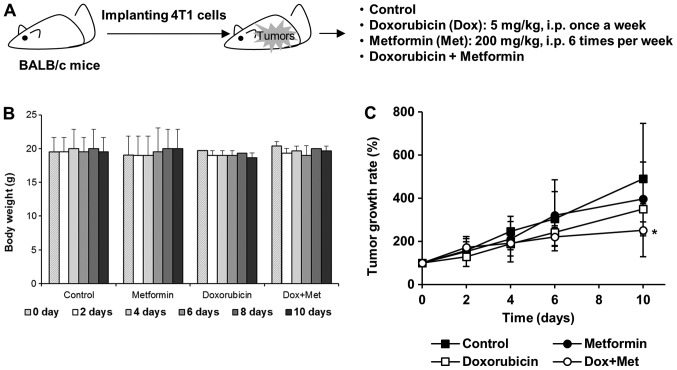

Met exhibited synergistic antitumor effects with Dox in 4T1 tumor-bearing mice

We further evaluated the antitumor effects of Met on 4T1 tumor-bearing BALB/c mice. 4T1 cells were implanted into the mammary gland fat pads of BALB/c female mice and when mice had developed about 100 mm3 tumors (measured with calipers), they were injected intraperitoneally with Dox (5 mg/kg, once a week), Met (200 mg/kg, once a day), or both (Fig. 5A). Mouse body weights were unaffected by these treatment schedules (Fig. 5B). Tumor growth was mildly suppressed in mice treated with 200 mg/kg Met alone, and mice treated with Dox alone exhibited a tumor growth reduction of ~30% vs. untreated mice. However, this antitumor effect of Dox was significantly enhanced when mice were treated with Dox plus Met (Fig. 5C), suggesting that synergism between Met and Dox accelerated tumor regression.

Figure 5.

Met enhances the ability of Dox to suppress tumor growth. (A) Experimental scheme for testing the antitumor effects of Dox and Met in vivo. (B) No loss of body weight occurred in mice treated with Dox or Met alone or in combination. (C) Synergistic antitumor effects of Met and Dox in 4T1 tumor-bearing BALB/c mice. *P<0.05 vs. control at day 10. Dox, doxorubicin; Met, metformin; i.p. intraperitoneal injection.

Discussion

Initially, TS culture was proposed to detect and propagate CSCs in the stem cell biology (13–15). Although there is ongoing debate regarding the enrichment of CSCs in TS (25,26), the generation of TS confers interesting and unique features on cells, such as, quiescence (27–29). We previously observed that sphere cultures exhibited higher proportions of quiescent cells (22–24), and in the present, we also observed that the majority of cells in 4T1 TS are quiescent, showing the accumulations of cells in the G0/G1 phase in TS as compared to cells in monolayer culture. This increased quiescent nature of cells in 4T1 TS confers chemoresistance to Dox and Lapa.

Recently, it was demonstrated that CSCs are resistant to chemotherapeutics and served as the root cause of disease recurrence and metastasis (30–32). Thus, the elimination of CSCs is considered an effective strategy to improve clinical response in breast cancer. Interestingly, Met has been shown to selectively target CSCs, showing the decrease in the CD44high/CD24low or ALDH-1 CSC fractions and the suppression of the number and size of TS (12,17,18). However, the mechanisms underlying the selective targeting of CSCs by Met have not been fully elucidated. In the present study, we also observed that Met preferentially targeted 4T1 TS rather than cells in monolayer culture, and that it enhanced the sensitivity of TS to Dox and Lapa. In addition, it was found this enhancement of the antitumor effects of chemotherapeutics by Met appeared to be mediated by downregulations of the STAT3 and AKT signaling pathways.

PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway is a well-known intracellular pathway, and its activation leads to the survival and proliferation of cancer cells. Recently published evidences suggest that activation of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway is required for the viability and maintenance of breast CSCs (21,33,34). Zhou et al reported that CSC fractions were significantly reduced after silencing the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway using a lentivirus-based short-hairpin RNA (shRNA) (21). In another study, suppression of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway was found to be preferentially toxic to CSCs (33). Met has been shown to inactivate the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway through AMPK activation and that this inactivation results in cell cycle arrest, apoptosis, and inhibits tumorigenesis. Met can also directly target mTOR independently of AMPK (2,35). In the present study, we were unable to detect AMPK activation by Met because endogenous AMPK expression was undetectable in 4T1 TS (data not shown). However, Met efficiently and dose-dependently inhibited the phosphorylation of AKT, which implies that Met directly targets the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway in 4T1 TS without activating AMPK.

Like the role played by the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway, the STAT3 signaling pathway has been associated with the generation and maintenance CSCs in breast cancer (21,36,37). STAT3 is an important transcription factor that maintains embryonic stem cells (ESCs) in an undifferentiated state (38,39). When STAT proteins are fully activated, they dimerize and translocate into nucleus to regulate gene expression. Regarding the role of STAT3 in CSCs, it has been shown STAT3 is preferentially active in CD44high/CD24low human breast cancer cells (36), and that STAT3 agonist expands the proportion of CD44high/CD24low CSCs fraction (40). Wei et al used a lentiviral fluorescent STAT3 signaling reporter system to identify STAT3-mediated transcriptional activity, and found that cells displaying highly activated STAT3 signaling are enriched for in vitro TS formation potential and tumorigenic potential in an in vivo transplantation assay (37). Although STAT3 is not a well-known target of Met, in the present study, Met efficiently suppressed STAT3 phosphorylation in 4T1 TS. Similarly, Deng et al reported that Met targets STAT3 to inhibit cell growth and induce apoptosis in triple negative breast cancer (41). Beside the STAT3, we also checked other transcription factors including NF-κB and c-fos. However, c-fos was not detected in Met-treated 4T1 TS, and the expression of NF-κB was not affected by Met (data not shown), implying that STAT3 is a major transcription factor targeted by Met in 4T1 TS.

Considering the vital roles of AKT and STAT3 in CSCs, it might be that the selective cytotoxic effect of Met on 4T1 TS was derived from its inhibitory effects on the AKT and STAT3 signaling pathways. The link between the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway and the STAT3 signaling pathway within 4T1 TS was not elucidated in the present study, but we consider that inhibition of AKT phosphorylation by Met probably leads to the inactivation of STAT3 signaling in 4T1 TS, because it has been proposed that the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway is a positive regulator of STAT3 signaling (21).

In the present study, we found that 4T1 TS were resistant to Dox or Lapa because of upregulations of the STAT3 and AKT signaling pathways, and that Met overcame chemoresistance by inhibiting the phosphorylations of AKT and STAT3 in Dox-treated TS. Furthermore, Met exhibited synergistic antitumor effects with Dox in 4T1 tumor-bearing BALB/c mice. Accordingly, our findings suggest that Met and cytotoxic anticancer drugs when used in combination offer benefits for the treatment of drug-resistant breast cancer. But these findings have limitations to elucidate full mechanisms on synergistic antitumor effect of Met and anticancer drugs, so further study is needed.

In summary, we show that the inhibitions of AKT and STAT3 activation underlies the selective cytotoxic effects of Met on TS. We hope that these results provide clues regarding the mechanism responsible for the targeting of CSCs by Met and a basis for the use of combinations of Met and chemotherapeutics to improve clinical response in breast cancer patients.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- AKT

protein kinase B

- AMPK

AMP-activated protein kinase

- CSC

cancer stem cells

- Dox

doxorubicin

- ERK

extracellular signal-regulated kinase

- Lapa

lapatinib

- Met

metformin

- STAT3

signal transducer and activator of transcription 3

- TS

tumorspheres

Funding

The present study was supported by a grant from the National R&D Program for Cancer Control, the Korean Ministry of Health & Welfare (grant no. 1320060) and by a grant from the Basic Science Research Program, Korean National Research Foundation (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology, Republic of Korea (grant no. NRF-2015R1D1A1A01059738).

Availability of data and materials

All data generated during this study are included in this published article.

Authors' contributions

YSK contributed to the conception and design of the study, and the acquisition of data, and wrote the manuscript. SYC performed experiments to acquire the data and analyzed data. HYN analyzed and interpreted the data. KSN contributed to the conception and design of the study. CL contributed to the conception and design of the manuscript, and was involved in drafting and revising the manuscript. SK contributed to the conception and design of the manuscript, drafted and wrote the manuscript, and gave final approval of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Animal experimentation was performed after obtaining approval from the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Dongguk University (approval no. IACUC-2016-003; Gyeongju-si, Korea).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Hundal HS, Ramlal T, Reyes R, Leiter LA, Klip A. Cellular mechanism of metformin action involves glucose transporter translocation from an intracellular pool to the plasma membrane in L6 muscle cells. Endocrinology. 1992;131:1165–1173. doi: 10.1210/endo.131.3.1505458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dowling RJ, Goodwin PJ, Stambolic V. Understanding the benefit of metformin use in cancer treatment. BMC Med. 2011;9:33. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-9-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Evans JM, Donnelly LA, Emslie-Smith AM, Alessi DR, Morris AD. Metformin and reduced risk of cancer in diabetic patients. BMJ. 2005;330:1304–1305. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38415.708634.F7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bowker SL, Majumdar SR, Veugelers P, Johnson JA. Increased cancer-related mortality for patients with type 2 diabetes who use sulfonylureas or insulin. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:254–258. doi: 10.2337/dc06-0997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dowling RJ, Zakikhani M, Fantus IG, Pollak M, Sonenberg N. Metformin inhibits mammalian target of rapamycin-dependent translation initiation in breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2007;67:10804–10812. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iliopoulos D, Hirsch HA, Struhl K. Metformin decreases the dose of chemotherapy for prolonging tumor remission in mouse xenografts involving multiple cancer cell types. Cancer Res. 2011;71:3196–3201. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-3471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buzzai M, Jones RG, Amaravadi RK, Lum JJ, DeBerardinis RJ, Zhao F, Viollet B, Thompson CB. Systemic treatment with the antidiabetic drug metformin selectively impairs p53-deficient tumor cell growth. Cancer Res. 2007;67:6745–6752. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shank JJ, Yang K, Ghannam J, Cabrera L, Johnston CJ, Reynolds RK, Buckanovich RJ. Metformin targets ovarian cancer stem cells in vitro and in vivo. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;127:390–397. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2012.07.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu B, Fan Z, Edgerton SM, Deng XS, Alimova IN, Lind SE, Thor AD. Metformin induces unique biological and molecular responses in triple negative breast cancer cells. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:2031–2040. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.13.8814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zakikhani M, Dowling R, Fantus IG, Sonenberg N, Pollak M. Metformin is an AMP kinase-dependent growth inhibitor for breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2006;66:10269–10273. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rattan R, Ali Fehmi R, Munkarah A. Metformin: An emerging new therapeutic option for targeting cancer stem cells and metastasis. J Oncol. 2012;2012:928127. doi: 10.1155/2012/928127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hirsch HA, Iliopoulos D, Tsichlis PN, Struhl K. Metformin selectively targets cancer stem cells, and acts together with chemotherapy to block tumor growth and prolong remission. Cancer Res. 2009;69:7507–7511. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-2994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dontu G, Abdallah WM, Foley JM, Jackson KW, Clarke MF, Kawamura MJ, Wicha MS. In vitro propagation and transcriptional profiling of human mammary stem/progenitor cells. Genes Dev. 2003;17:1253–1270. doi: 10.1101/gad.1061803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ponti D, Costa A, Zaffaroni N, Pratesi G, Petrangolini G, Coradini D, Pilotti S, Pierotti MA, Daidone MG. Isolation and in vitro propagation of tumorigenic breast cancer cells with stem/progenitor cell properties. Cancer Res. 2005;65:5506–5511. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang L, Jiao M, Li L, Wu D, Wu K, Li X, Zhu G, Dang Q, Wang X, Hsieh JT, He D. Tumorspheres derived from prostate cancer cells possess chemoresistant and cancer stem cell properties. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2012;138:675–686. doi: 10.1007/s00432-011-1146-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen G, Xu S, Renko K, Derwahl M. Metformin inhibits growth of thyroid carcinoma cells, suppresses self-renewal of derived cancer stem cells, and potentiates the effect of chemotherapeutic agents. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:E510–E520. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-1754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jung JW, Park SB, Lee SJ, Seo MS, Trosko JE, Kang KS. Metformin represses self-renewal of the human breast carcinoma stem cells via inhibition of estrogen receptor-mediated OCT4 expression. PLoS One. 2011;6:e28068. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Song CW, Lee H, Dings RP, Williams B, Powers J, Santos TD, Choi BH, Park HJ. Metformin kills and radiosensitizes cancer cells and preferentially kills cancer stem cells. Sci Rep. 2012;2:362. doi: 10.1038/srep00362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vazquez-Martin A, Oliveras-Ferraros C, Cufi S, Del Barco S, Martin-Castillo B, Menendez JA. Metformin regulates breast cancer stem cell ontogeny by transcriptional regulation of the epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) status. Cell Cycle. 2010;9:3807–3814. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.18.13131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cufí S, Vazquez-Martin A, Oliveras-Ferraros C, Martin-Castillo B, Joven J, Menendez JA. Metformin against TGFβ-induced epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT): From cancer stem cells to aging-associated fibrosis. Cell Cycle. 2010;9:4461–4468. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.22.14048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhou J, Wulfkuhle J, Zhang H, Gu P, Yang Y, Deng J, Margolick JB, Liotta LA, Petricoin E III, Zhang Y. Activation of the PTEN/mTOR/STAT3 pathway in breast cancer stem-like cells is required for viability and maintenance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:16158–16163. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702596104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chun SY, Kwon YS, Nam KS, Kim S. Lapatinib enhances the cytotoxic effects of doxorubicin in MCF-7 tumorspheres by inhibiting the drug efflux function of ABC transporters. Biomed Pharmacother. 2015;72:37–43. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2015.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim S, Alexander CM. Tumorsphere assay provides more accurate prediction of in vivo responses to chemotherapeutics. Biotechnol Lett. 2014;36:481–488. doi: 10.1007/s10529-013-1393-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kwon YS, Chun SY, Nam KS, Kim S. Lapatinib sensitizes quiescent MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells to doxorubicin by inhibiting the expression of multidrug resistance-associated protein-1. Oncol Rep. 2015;34:884–890. doi: 10.3892/or.2015.4047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Calvet CY, André FM, Mir LM. The culture of cancer cell lines as tumorspheres does not systematically result in cancer stem cell enrichment. PLoS One. 2014;9:e89644. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0089644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pastrana E, Silva-Vargas V, Doetsch F. Eyes wide open: A critical review of sphere-formation as an assay for stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;8:486–498. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2011.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guttilla IK, Phoenix KN, Hong X, Tirnauer JS, Claffey KP, White BA. Prolonged mammosphere culture of MCF-7 cells induces an EMT and repression of the estrogen receptor by microRNAs. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;132:75–85. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1534-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Manuel Iglesias J, Beloqui I, Garcia-Garcia F, Leis O, Vazquez-Martin A, Eguiara A, Cufi S, Pavon A, Menendez JA, Dopazo J, Martin AG. Mammosphere formation in breast carcinoma cell lines depends upon expression of E-cadherin. PLoS One. 2013;8:e77281. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Uchida Y, Tanaka S, Aihara A, Adikrisna R, Yoshitake K, Matsumura S, Mitsunori Y, Murakata A, Noguchi N, Irie T, et al. Analogy between sphere forming ability and stemness of human hepatoma cells. Oncol Rep. 2010;24:1147–1151. doi: 10.3892/or_00000966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li L, Bhatia R. Stem cell quiescence. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:4936–4941. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-1499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moore N, Lyle S. Quiescent, slow-cycling stem cell populations in cancer: A review of the evidence and discussion of significance. J Oncol. 2011;2011:396076. doi: 10.1155/2011/396076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tirino V, Desiderio V, Paino F, De Rosa A, Papaccio F, La Noce M, Laino L, De Francesco F, Papaccio G. Cancer stem cells in solid tumors: An overview and new approaches for their isolation and characterization. FASEB J. 2013;27:13–24. doi: 10.1096/fj.12-218222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eyler CE, Foo WC, LaFiura KM, McLendon RE, Hjelmeland AB, Rich JN. Brain cancer stem cells display preferential sensitivity to Akt inhibition. Stem Cells. 2008;26:3027–3036. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-1073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Korkaya H, Paulson A, Charafe-Jauffret E, Ginestier C, Brown M, Dutcher J, Clouthier SG, Wicha MS. Regulation of mammary stem/progenitor cells by PTEN/Akt/beta-catenin signaling. PLoS Biol. 2009;7:e1000121. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kalender A, Selvaraj A, Kim SY, Gulati P, Brûlé S, Viollet B, Kemp BE, Bardeesy N, Dennis P, Schlager JJ, et al. Metformin, independent of AMPK, inhibits mTORC1 in a rag GTPase-dependent manner. Cell Metab. 2010;11:390–401. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2010.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marotta LL, Almendro V, Marusyk A, Shipitsin M, Schemme J, Walker SR, Bloushtain-Qimron N, Kim JJ, Choudhury SA, Maruyama R, et al. The JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathway is required for growth of CD44+CD24+ stem cell-like breast cancer cells in human tumors. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:2723–2735. doi: 10.1172/JCI44745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wei W, Tweardy DJ, Zhang M, Zhang X, Landua J, Petrovic I, Bu W, Roarty K, Hilsenbeck SG, Rosen JM, Lewis MT. STAT3 signaling is activated preferentially in tumor-initiating cells in claudin-low models of human breast cancer. Stem Cells. 2014;32:2571–2582. doi: 10.1002/stem.1752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Matsuda T, Nakamura T, Nakao K, Arai T, Katsuki M, Heike T, Yokota T. STAT3 activation is sufficient to maintain an undifferentiated state of mouse embryonic stem cells. EMBO J. 1999;18:4261–4269. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.15.4261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Raz R, Lee CK, Cannizzaro LA, d'Eustachio P, Levy DE. Essential role of STAT3 for embryonic stem cell pluripotency. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:2846–2851. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.6.2846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Iliopoulos D, Hirsch HA, Wang G, Struhl K. Inducible formation of breast cancer stem cells and their dynamic equilibrium with non-stem cancer cells via IL6 secretion. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:1397–1402. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1018898108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Deng XS, Wang S, Deng A, Liu B, Edgerton SM, Lind SE, Wahdan-Alaswad R, Thor AD. Metformin targets Stat3 to inhibit cell growth and induce apoptosis in triple-negative breast cancers. Cell Cycle. 2012;11:367–376. doi: 10.4161/cc.11.2.18813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated during this study are included in this published article.