Abstract

Background:

Using digital technology to deliver mental health care can possibly serve as a viable adjunct or alternative to mainstream services in lessening the mental health gap in a large number of resource deficient and LAMI countries. Conventional models of telepsychiatric services available so far, however, have been inadequate and ineffective, as these address only a small component of care, and rely on engagement of specialists who are grossly insufficient in numbers.

Aim:

To describe an innovative digital model of mental health care, enabling and empowering the non-specialists to deliver high quality mental health care in remote areas.

Methods:

The model is powered by an online, fully automated clinical decision support system (CDSS), with interlinked modules for diagnosis, management and follow-up, usable by non-specialists after brief training and minimal supervision by psychiatrist, to deliver mental health care at remote sites.

Results:

The CDSS has been found to be highly reliable, feasible, with sufficient sensitivity and specificity. This paper describes the model and initial experience with the digital mental health care system deployed in three geographically difficult and remote areas in northern hill states in India. The online system was found to be reasonably comprehensive, brief, feasible, user-friendly, with high levels of patient satisfaction. 2594 patients assessed at the three remote sites and the nodal center represented varied diagnoses.

Conclusions:

The digital model described here has the potential to serve as an effective alternative or adjunct for delivering comprehensive and high quality mental health care in LAMI countries like India in the primary and secondary care settings.

Keywords: Digital, mental health care, tele psychiatry

INTRODUCTION

Mental health care services in the low and middle income (LAMI) countries are highly deficient due to lack of resources and workforce, leading to a significant mental health gap[1] in treatment, which together with high prevalence and consequent disability due to mental illness,[2] poses a major public health challenge. The conventional way to bridge this “mental health gap” in LAMI countries like India has been by integrating mental health care with primary-care services, educating and training primary-care physicians and health workers in identification and management of selected mental disorders. However, these efforts have been fraught with several logistical difficulties including inadequate funding, difficulties in training and motivating primary-care personnel, lack of continued support from specialists, limited coverage of mental disorders, and long gestation period before they begin to make a difference.[3] Moreover, this approach often creates social inequity, as it establishes two contrasting levels of care, i.e., a low intensity, minimalistic care delivered by nonspecialists; and a more comprehensive and better quality care by specialists.

Therefore, it has become necessary to think of alternatives such as telepsychiatry to support psychiatric care at a peripheral, distant or remote site from a central or nodal site.[4] However, such “telepsychiatric” services to have been slow to take off in LAMI countries because of problems of funding, the absence of support from the government and the industry, lack of infrastructure and the paucity of trained personnel.[5] Prompted by these challenges, a project on delivering psychiatric services to three remote sites, using digital and information communication technology, was initiated at the Department of Psychiatry at the Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research (PGIMER), Chandigarh, India.[6]

The remote sites chosen were located in the adjoining hill states of North-India, namely Himachal Pradesh (HP), Uttarakhand (UK) and Jammu and Kashmir (JK), at a distance of 180 km, 350 km, and 650 km, respectively, from Chandigarh, the nodal site. The three sites have very large, geographically difficult and inaccessible terrains and a very low number of psychiatrists. There are about 20 psychiatrists in HP for a population of 7 million; 30 in UK for a population of over 10 million; and about 30 in Kashmir for a population of 7 million. This article describes the process of deployment of the digital application and system; and assessment of its performance and potential in diagnosis and treatment of psychiatric disorders at the remote sites.

The aim of the project was to develop and implement a digitally enabled model mental healthcare system through the development of an application for comprehensive diagnosis and management (i.e., a Clinical Decision Support System; [CDSS]), for providing high quality mental health care, through nonspecialists, in the geographically difficult and unserved areas.

METHODS

The project had two components: (1) development and standardization of the diagnostic and management application or CDSS; and (2) deployment of the digitally enabled service and testing in real time.

Development and standardization of the diagnostic and management application

The process of development and standardization of the application software has been already described in detail in several publications.[7,8,9,10,11,12,13] A quick overview of the application is given here.

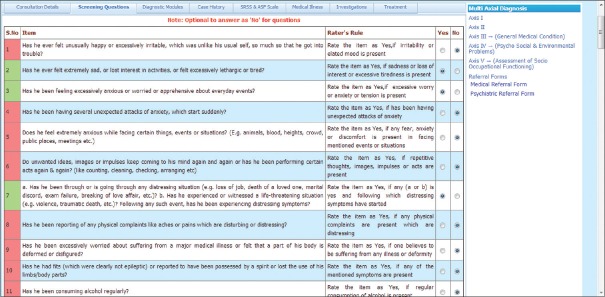

A fully automated, internet-based, computerized, CDSS was developed with three interlinked modules for diagnosis, management, and follow-up,[7,8,9,10,11] based on clinical knowledge and conditional logic to generate specific diagnosis, and intelligently filter patient data and guide appropriate, patient-specific recommendations for patient care.[14] Separate versions of the CDSS based application were developed for 18 common psychiatric disorders among adults[7,8,9] and 18 such disorders among children and adolescents[10,11] in a bilingual (English and Hindi) format. The diagnostic module comprised of the “core” section with two submodules, i.e., screening and specific disorders wise diagnosis; and “additional history” section comprising submodules to tap detailed history, stress factors, family and personal history, premorbid personality, physical illness, and physical and mental state examination. While the “core” section is essential for diagnosis and management, the “additional history” section adds useful information for management decisions. The “core” diagnostic module consists of a screening sub-module with 18 questions for all disorders and detailed diagnostic sub-modules for assessment of specific disorders included in the application, based on the International Statistical Classification of Disease -10 and Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders -IV criteria.[15,16,17] Equal stress was placed on a comprehensive and objective criteria-based interview as well as a semi-structured format of questioning in the diagnostic module guided by the question item, the “Rater's rules” and the “Decision Rules.” Each question-item was based on the official criteria-sets, but was more descriptive and used culturally relevant idioms. “Raters” rules’ specified how the interviewer should rate an item as present or absent, based on the intent of the question, the duration, and persistence of symptoms, and distress or dysfunction caused by symptoms. This allowed the diagnostic assessment to be conducted in a conversational style using simple language easily understood by both patients and interviewers. The aim was to replicate a routine clinical situation with considerable emphasis on allying with patients and caregivers right from the onset. The “screening module” acted as the first gateway and depending on the responses to screening questions the relevant disorder-specific detailed diagnostic assessments opened automatically based on an inbuilt hierarchy. Each disorder-specific diagnostic assessment had a second-level enquiry about the primary or typical symptoms of the disorder, which proceeded to a third-level enquiry employing other criteria only if the specified threshold were met at the second level. If the threshold was not met the remaining part of that sub-module was skipped and the application moved to the next disorder derived from screening. The diagnostic algorithm of the CDSS consisted of ‘decision rules,’ i.e., automated rules, by defining how particular responses influenced the diagnostic decision-making tree. “Decision rules” were built based on the diagnostic thresholds set by official classifications as well as socio-cultural norms and symptom-characteristics including the level of dysfunction. Screenshot of screening module is given in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Screenshot of the screening Module of the clinical decision support system

At the end of the diagnostic interview, an automated diagnosis emerges and a summary profile is generated that shows the positive findings in one glance. In addition, modules for assessments of symptom-severity (on a five-point scale) and socio-occupational functioning (on a visual analog scale) were also included to complete the diagnostic assessment.

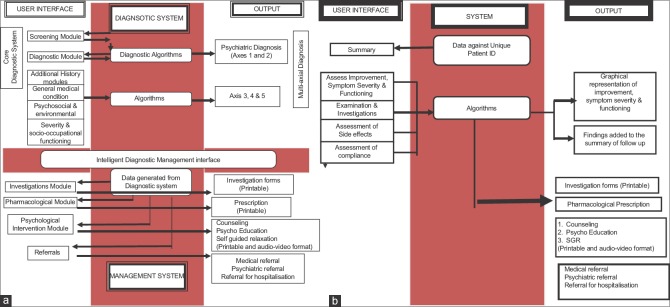

Diagnostic module can be used by a general physician, a psychologist or a healthcare worker with 1 week training in interviewing skills and rating of items. The generation of diagnosis is done by the system through inbuilt rules [Figure 2a].

Figure 2.

(a): First consultation. (b) Follow-up consultation

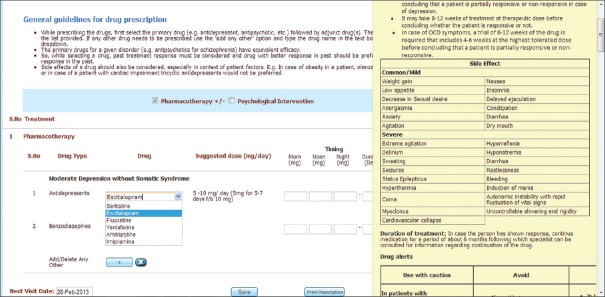

The management module [Figure 2b] is logically linked to the diagnostic module and comprises of submodules for pharmacological and nonpharmacological intervention, investigations, medical or psychiatric referral, and hospitalization.[12,13] Investigations include the necessary and other investigations as indicated. The pharmacological sub-module provides the prescriber with options for pharmacological treatment depending on availability, safety, tolerability and evidence-based, and a printable prescription.[12] Brief drug information, dosing schedules and alerts for medical comorbities and special situations such as pregnancy were incorporated for proper prescribing. Screenshot of pharmacological treatment module is given in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Screenshot of pharmacological module of clinical decision support system

The nonpharmacological sub-module consists of 30 information/guidance/counseling leaflets, about mental illness in general and specific disorders. These could be used for educating patients and caregivers and handed over to them after the counseling sessions.[6] Furthermore included is a simple autogenic-training based relaxation exercise, with printed and audio/video instructions for users.[13] Finally, the follow-up module contains instructions on assessing improvement, making changes to the treatment, recording side effects, new symptoms if any, compliance and referring the patient for specialist care when required.[6] Figure 2 shows the work-flow of the CDSS.

At various stages of development and functioning of the application, its performance on various aspects of the accuracy of diagnostic and management modules, the usefulness of the relaxation exercise and the feasibility of use of application were examined separately among subsamples of 418 adults and 188 children/adolescents.

Deployment of digital mental healthcare service and testing in real time

Predeployment online training and validity/reliability checks

The service was set up at the psychiatry department at the PGIMER Chandigarh as the nodal center and three remote sites as described above with basic infrastructure comprising of a basic telephone connection, a broadband connection, one desktop computer, one lap top, and one printer, set up in a secure and designated physical space, at each of the participating sites. The programme was run mainly by psychologists supervised by psychiatrists at the nodal center, while psychologists, social workers, general practitioners, and psychiatrists (where available) formed the teams at peripheral sites. Training of the teams at remote sites was done initially by two sessions of the face-to-face interaction at the nodal site, and later on, through video-conferencing using Skype software in about 15 h, spread over 4–5 sessions of 3–4 h each.[18] The effectiveness of training of the remote site teams was rigorously tested through reliability and validity studies.[19,20]

Deployment and use in real time

The psychologist or the social worker at the remote site, after due training, independently interviewed the patients and key informants using the application software. Once the automated diagnosis was generated, the general physician in the remote site team looked at the patient data, summary profile, and the patient for a quick look and reconfirmation of positive findings if necessary. The GP then moved on to the management protocol in the application, assisted in the choice of medication, prescribing information and guidelines and a printable prescription. The prescription is handed over to the patient/relative. The GP is also assisted to prescribe psychological intervention in the form of psychoeducation, counseling, guidance, self-guided relaxation which is carried out by the psychologist or the social worker as per the modules provided in the CDSS. The GP can order physical investigations as required or alerted by the application in a given patient.

The patient comes for follow-up on recommended date and is assessed using the follow-up module that included rating of patient's symptoms in comparison to what were present at first assessment, general condition, new symptoms if any, side effects if any, and compliance. Investigation results are reviewed by the GP and prescription is renewed. The Application provides inbuilt guidance for the GP to deal with side effects or lack of improvement in the patient, in the form of changes in drug dosing, scheduling, or adding or removing any drug and so on. There are automated charts generated for symptom severity ratings, psychosocial functioning or of medical investigation results.

The remote site teams were supervised by the team of psychiatrists at the nodal site for reliability and validity checks and also for assistance in difficult cases through store forward data consultation as well as real-time video conferencing with the patient or the team members as necessary.

RESULTS

Development and standardization of the diagnostic and management application

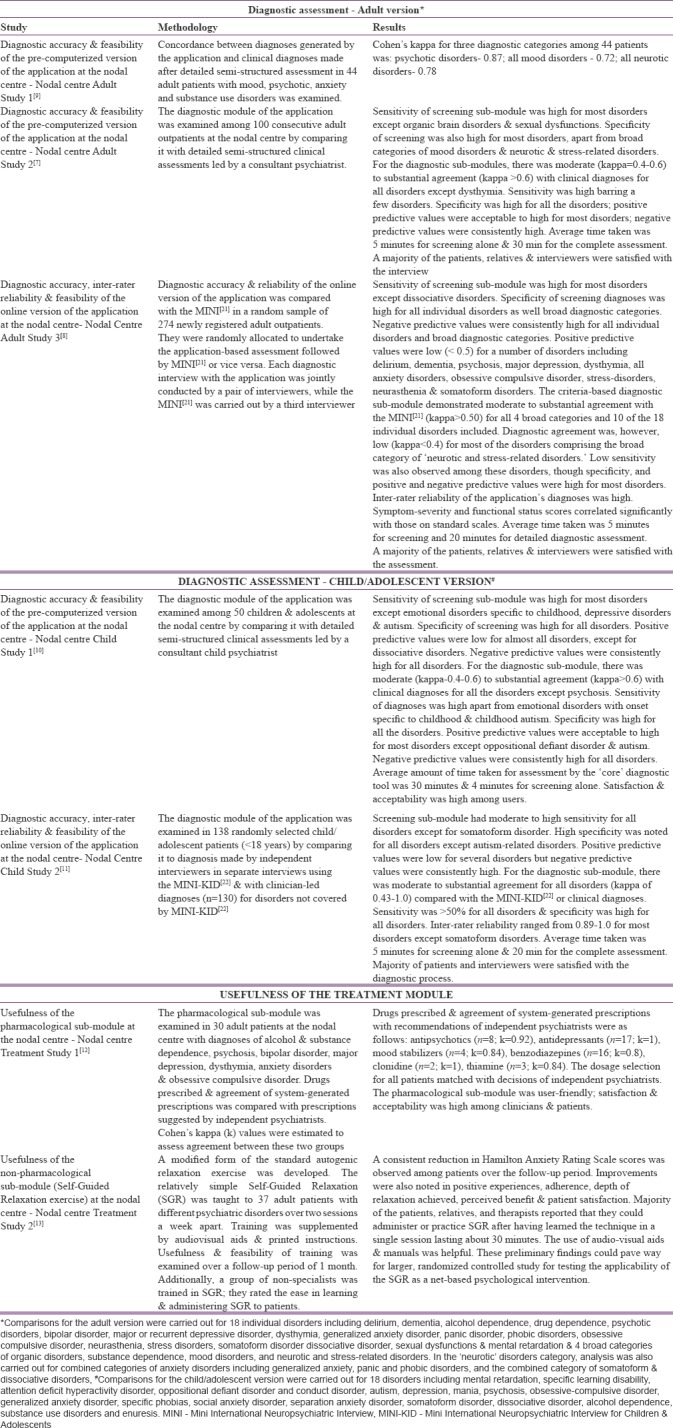

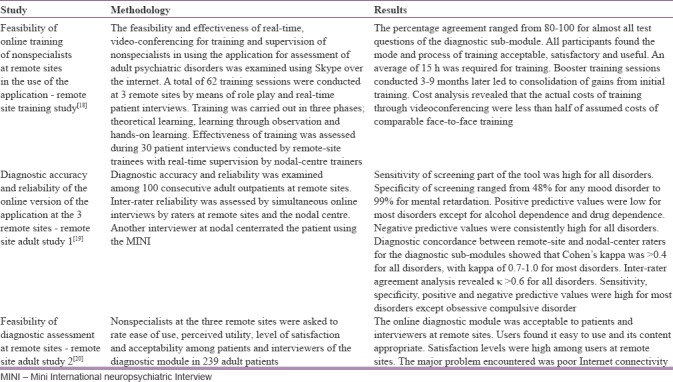

Brief description and summary of the results of the studies examining the validity, reliability, and feasibility of the diagnostic and management modules of the application are given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Performance of the diagnostic and treatment modules of the telepsychiatric application

Two standards were used for the reliability and accuracy of the CDSS generated diagnoses. Clinical diagnoses obtained from detailed semi-structured criteria-based assessments led by experienced consultant psychiatrists; and the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI)[21] for adults; and MINI-KID for children/adolescents.[22]

The results of the examination of diagnostic accuracy, reliability, and feasibility across all versions and sites demonstrated certain common trends. The screening sub-module of the application was brief (<5 min), included a broad range of commonly prevalent disorders, had high sensitivity for most disorders; high specificity in detecting these disorders; and consistently high negative predictive values for all disorders; and positive predictive values <50% for some disorders including psychotic disorders. This was not unusual as instruments with high sensitivity, high specificity, and high-negative predictive values can function as satisfactory screens for psychiatric disorders despite having low-positive predictive values.[23,24,25] The criteria-based diagnostic sub-module demonstrated moderate to substantial agreement (kappa >0.50) for all broad categories and most of the 18 individual disorders.[7,8,9] Inter-rater reliability was also high.[8] Specificity and positive and negative predictive values were high for most disorders.[7,8] Ratings of symptom-severity and functional status were adequate. The average time of <20 min for diagnostic assessments compared well with the MINI as did the high patient and interviewer acceptability rates.[7,8] However, diagnostic agreement and sensitivity rates were low for most “neurotic and stress-related disorders” among adults as well as children/adolescents, a finding that was similar to that observed in studies comparing the MINI with other structured interviews.[21] Poor performance was also observed for certain childhood disorders such as autism-related conditions.[10,11] However, since the application has the facility for continuous up gradation, it is expected that these aspects of diagnostic performance can be improved upon. Initial examination of treatment modules, both the pharmacological and nonpharmacological modules as well as of the follow-up module, gave satisfactory and encouraging results.[12,13]

Deployment of digital mental healthcare service and testing in real time

Predeployment online training and validity/reliability checks

Online training was highly cost-effective, convenient, and acceptable to the trainees at remote sites, and resulted in a high degree of reliability of assessment.[18] Table 2 shows the results of reliability, feasibility and preliminary cost analysis of the online training.

Table 2.

Predeployment feasibility of online training and performance of clinical decision support system when used by nonspecialists

Results of the validity, reliability, and feasibility studies[19,20] of the CDSS conducted at the remote sites after completion of the online training are depicted in Table 2. The diagnostic concordance between remote-site and nodal-center raters for the diagnostic sub-modules showed that Cohen's kappa was 0.7–1.0 for most disorders and >0.4 for all disorders.[19] Inter-rater agreement analysis revealed kappa >0.6 for all disorders.[19] The online diagnostic module was acceptable to patients and interviewers at remote sites.[20]

Deployment and use in real time

A total of 2594 patients were assessed using the CDSS at the nodal and the three remote sites cumulatively. Out of these, 310 patients were seen at HP site, 370 at JK site, 643 at UK site, and 1271 patients at the nodal center using the CDSS. The interim analysis showed that the most common diagnosis made at all the remote sites combined was that of mood disorders (49%), closely followed by substance and alcohol use disorders (44%).[26] Around 33% had anxiety and stress-related disorders while about 23% had psychotic disorders. Individually, at HP, more than half of the patients (about 53%) received a substance and alcohol use related diagnosis, whereas about 47% received a diagnosis of a mood disorder. About a quarter (about 27%) had neurotic and stress-related disorders and 12% had a psychotic disorder. The mean total number of diagnosis per patient at HP site was 1.83 (standard deviation (SD)– 0.90) while the median number of diagnosis was 2. On the other hand, the profile of patients in the UK was somewhat different. Only around 18% had substance or alcohol-related disorders, while about 32% had a psychotic disorder, whereas 40% had anxiety and stress-related disorders. However, at the UK too, like in HP about half (49%) had a mood disorder diagnosis. In JK center, a majority received mood disorder diagnosis (76%), whereas 32% had substance or alcohol related disorder, 23% had a neurotic and stress-related disorder and 13% had a psychotic disorder. The mean total number of diagnosis at UK and JK were 1.45 (SD– 0.63) and 2.32 (SD– 1.70), respectively, but the median was 1 at both the sites.

A majority of the patients and interviewers at the three remote sites reported an overall satisfaction to a large extent or to a full extent and found the use of online application acceptable. Over 90% of the interviewers considered that the online diagnostic and management application was easy to use. More than 80%–90% of the participating interviewers and patients/their caregivers were satisfied with the interviewing style, language used, coverage of presenting complaints and coverage of psycho-social issues, and found the length of the application-based interview adequate. Most of the interviewers were satisfied with the coverage of psychiatric disorders and the depth to which these were covered. All the physicians and psychiatrists at the remote sites were satisfied with the choice of drugs and suggested dosing, and found the drug information, particularly useful especially in the initial prescriptions. Psycho-education and counseling modules were found to be useful and easy to understand by patients/their caregivers and the treating healthcare workers. The relaxation training module and its audio-video aid were particularly helpful both to trainers and patients and the training was considered useful by patients. Moreover, during the open feedback all the teams expressed that they considered using the tool as a self-educating measure, it sensitized them to elicitation of psychiatric signs and symptoms, and psychosocial stressors, aided them in improving their interviewing skills, increased their self-confidence and were satisfied with the quality of care they were able to provide following comprehensive assessment.

DISCUSSION

Service development in LAMI countries has been particularly disheartening, and it is in these countries that mental health services are required the most.[5,27,28] Inadequate development of telepsychiatric services in LAMI countries is often attributed to deficiencies in funding and support from governments and industries, infrastructure problems leading to poor Internet penetration and connectivity, shortage of skilled personnel, a weak evidence base for effectiveness and socio-cultural differences hampering acceptability.[5]

The current effort set out to address some of these problems by trying to develop a workable digital mental healthcare model providing high-quality service to three remote sites in North-India. Several innovations proved necessary on the way to achieving this goal, the principal ones being the adoption of a different model of telepsychiatric care and the development of a new digital application which could support this model. In developed countries delivery of telepsychiatric services have usually followed the models of either direct management, or consultation-liaison approaches, or collaborative care or asynchronous telepsychiatry models.[29,30,31] However, given the dearth of manpower and other resources in LAMI countries like India, difficulties in implementing even these relatively simple models of care were likely.[27] Therefore, the present program adopted a model of care, which allowed nonspecialists at remote sites to diagnose and treat common psychiatric disorders relatively independently with minimal training and supervision, with constant ongoingsupport from the nodal center. The CDSS or the application software that was developed provided effective support for this “tele-enabling” model of care that was followed. So far, there are a few CDSS presently in psychiatry such as CIDI-Auto,[32] CompTMAP,[33,34] that are built primarily for only diagnosis or only drug treatment and are exclusive of the other area. Computerized diagnostic algorithms (e.g., CID1-Auto) are used mainly for epidemiological research and not for clinical purposes, are too long and do not cover disorders such as dissociative disorders seen in our setting.[32] The existing treatment algorithms, on the other hand, are not linked to any diagnostic decision support system and are developed in a stand-alone fashion. Furthermore, these have been developed for single disorders (mainly depression) and a single form of management for a specific disorder (e.g., pharmacological management for depression).[33,34,35] It has been also suggested that clinicians find such algorithms extremely restrictive.[33,35] As the newly developed CDSS allows the clinician to decide from a wide variety of treatment options and does not supersede, rather empowers the clinician, its acceptability is expected to be greater.[12] Similar to existing pharmacological treatment algorithms, previously developed online or computerized psychological treatments have largely been restricted to one type and one disorder. As against these, the application, which was also built from scratch, and used a CDSS to effectively and logically, link the diagnostic, treatment and follow-up modules that it was comprised as depicted in Figure 2. It was comprehensive in its coverage of psychiatric disorders, culturally sensitive and based on evidence and expertise.

The CDSS was extensively modified, enhanced, expanded, and tested during the entire process of its development and use in remote sites. The results of its diagnostic and treatment performance[7,8,9,10,11] indicated that barring a few limitations the diagnoses generated were reasonably accurate and reliable, while initial trials suggested that the treatments delivered appeared to be useful.[12,13] Additional advantages of the application included its brevity, flexibility because of the several versions available, local adaptability and user-friendliness. The application was password protected and hence secure. It generated electronic medical records (EMR) with a unique identification number for each patient. The EMR containing consultation, management and follow-up details for each visit for every patient are linked and compiled together through the built-in interface. It was hosted on developer-owned servers on a dynamic platform. It had both synchronous video conferencing and asynchronous, store and forward facilities. This CDSS, named as “psychiatristonweb,”[36] supports a multilingual format and has full scope for further improvement, customization and up-gradation, as and when necessary, based on further experience or advancement in knowledge. The diagnostic process is in the process of further refinements, the treatment modules are to be tested more exhaustively. Nevertheless, it is apparent the system can be used as an adjunct to support existing services or an alternative for nonexistent services, particularly in resource-constrained environments of LAMI countries. This model of digital mental health care can be easily deployed and integrated with the existing health care system in India utilizing the available infrastructure and workforce and has the potential to make mental health care accessible to most patients even in remotest of places. This digital mental healthcare system can also be used by psychiatrists to expand his/her area of operation for patients living at a distance, especially for follow-up visits, and to make more efficient use of his/her time as time per patient will be reduced significantly.

Ours is the first such system that comes closest to the practice of clinical psychiatry for patients seen in the primary or secondary healthcare setting, combining benefits of both digital technology and information communication technology. Moreover, this is also the first such system that empowers nonspecialists such as GP, psychologists, social workers or psychiatric nurse to provide high quality and minimum error mental health care at their level with minimal support or supervision of psychiatrists. Repeated use of the software application will have the advantage of self-learning and continuous upgradation of the knowledge and skills of the user.

Finally, much like the other budding telepsychiatric programs in India sustaining the current service has proved to be challenging. Though the project received funding from the government and the software was developed in collaboration with an industry partner (the Tata Consulting Services), on-going support has been limited. A permanent telepsychiatric unit has, however, been recently set up at the nodal center and initial links with other sites have been established. It is hoped that this will enable the implementation of the digital mental healthcare service on a larger scale and its eventual integration into the mainstream mental health services employing currently recommended hybrid models of improving patient care through telepsychiatry and digital technology.[28,37]

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

The authors are grateful to the Department of Science and Technology, Ministry of Science and Technology, Government of India for funding support; the Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh for logistic support; and the teams of doctors at the remote sites for their participation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Demyttenaere K, Bruffaerts R, Posada-Villa J, Gasquet I, Kovess V, Lepine JP, et al. Prevalence, severity, and unmet need for treatment of mental disorders in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. JAMA. 2004;291:2581–90. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.21.2581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kessler RC, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alonso J, Chatterji S, Lee S, Ormel J, et al. The global burden of mental disorders: An update from the WHO world mental health (WMH) surveys. Epidemiol Psichiatr Soc. 2009;18:23–33. doi: 10.1017/s1121189x00001421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murthy RS. Mental health initiatives in India (1947-2010) Natl Med J India. 2011;24:98–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Psychiatric Association. Telepsychiatry via Videoconferencing. Washington, D.C: The American Psychiatric Association; 1998. [Last accessed on 2016 May]. pp. 2–9. Available from: http://www.psychiatry.org/FileLibrary/Learn/Archives/199821.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chakrabarti S, Shah R. Telepsychiatry in the developing world: Whither promised joy? Indian J Soc Psychiatry. 2016;32:273–80. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Malhotra S, Chakrabarti S. Development and Implementation of a Model Telepsychiatry Application for Delivering Mental Healthcare in Remote Areas. (Using a Medical Knowledge-Based Decision Support System). Project Report August 2010 – June 2014. Department of Psychiatry, Post Graduate Institute of Medical Education & Research, Chandigarh & Department of Science and Technology, Government of India. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Malhotra S, Chakrabarti S, Shah R, Gupta A, Mehta A, Nithya B, et al. Development of a novel diagnostic system for a telepsychiatric application: A pilot validation study. BMC Res Notes. 2014;7:508. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-7-508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Malhotra S, Chakrabarti S, Shah R, Sharma M, Sharma K, Singh H, et al. Diagnostic accuracy and feasibility of a net-based application for diagnosing common psychiatric disorders. Psychiatry Res. 2015;230:369–76. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2015.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Malhotra S, Chakrabarti S, Gupta A, Mehta A, Nithya B, Shah R. Development of a semi-structured diagnostic tool for adult psychiatric disorders for use in primary care: Preliminary results. Indian J Psychiatry. 2012;54:S74. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Malhotra S, Chakrabarti S, Shah R, Mehta A, Gupta A, Sharma M, et al. Anovel screening and diagnostic tool for child and adolescent psychiatric disorders for telepsychiatry. Indian J Psychol Med. 2015;37:288–98. doi: 10.4103/0253-7176.162921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Malhotra S, Chakrabarti S, Shah R, Sharma M, Sharma KP. An online clinical decision support system for child and adolescent psychiatric disorders: validity, reliability, and feasibility of the diagnostic sub-system. Presented at the 62nd Annual meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. San Antonio; 26-31 October. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Malhotra S, Chakrabarti S, Shah R, Kumar V, Nithya B, Gupta A, et al. Computerised system of diagnosis and treatment in telepsychiatry: Development and feasibility of the pharmacological treatment module. Indian J Psychiatry. 2013;55:S129–30. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Malhotra S, Chakrabarti S, Gupta A, Mehta A, Shah R, Kumar V, et al. A self-guided relaxation module for telepsychiatric services: Development, usefulness, and feasibility. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2013;46:325–37. doi: 10.2190/PM.46.4.a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cresswell K, Majeed A, Bates DW, Sheikh A. Computerised decision support systems for healthcare professionals: An interpretative review. Inform Prim Care. 2012;20:115–28. doi: 10.14236/jhi.v20i2.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Health Organization. The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders. Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 16.World Health Organization. The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders. Diagnostic Criteria for Research. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 17.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Health Disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Malhotra S, Chakrabarti S, Gupta A, Mehta A, Sharma M, Kumar V, et al. Training non-specialists in clinical evaluation using video conferencing: Feasibility and effectiveness. 8th International Telemedicine Conference. Coimbatore, India; 29 November – 1 December. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Malhotra S, Chakrabarti S, Shah R, Sharma M, Sharma KP, Malhotra A, et al. Telepsychiatry clinical decision support system used by non-psychiatrists in remote areas: Validity & reliabilityof diagnostic module. Indian J Med Res. 2017;146:196–204. doi: 10.4103/ijmr.IJMR_757_15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Malhotra S, Chakrabarti S, Shah R, Gupta A, Jassal GD, Upadhyaya SK, et al. Computerised system of diagnosis and treatment in telepsychiatry: Experience and feasibility study of diagnostic module. Indian J Psychiatry. 2013;55:S47. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, et al. The mini-international neuropsychiatric interview (M.I.N.I.): The development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(Suppl 20):22–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sheehan DV, Sheehan KH, Shytle RD, Janavs J, Bannon Y, Rogers JE, et al. Reliability and validity of the mini international neuropsychiatric interview for children and adolescents (MINI-KID) J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71:313–26. doi: 10.4088/JCP.09m05305whi. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leon AC, Portera L, Olfson M, Weissman MM, Kathol RG, Farber L, et al. False positive results: A challenge for psychiatric screening in primary care. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154:1462–4. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.10.1462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nease DE, Jr, Maloin JM. Depression screening: A practical strategy. J Fam Pract. 2003;52:118–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zimmerman M, Sheeran T, Chelminski I, Young D. Screening for psychiatric disorders in outpatients with DSM-IV substance use disorders. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2004;26:181–8. doi: 10.1016/S0740-5472(03)00207-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Malhotra S, Chakrabarti S. Development and Implementation of a Model Telepsychiatry Application for Delivering Mental Healthcare in Remote Areas (Using a Medical Knowledge-Based Decision Support System) Project Report August 2010 – June 2013 Department of Psychiatry, Post Graduate Institute of Medical Education & Research, Chandigarh & Department of Science and Technology, Government of India. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Malhotra S, Chakrabarti S, Shah R. Telepsychiatry: Promise, potential, and challenges. Indian J Psychiatry. 2013;55:3–11. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.105499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chakrabarti S. Usefulness of telepsychiatry: A critical evaluation of videoconferencing-based approaches. World J Psychiatry. 2015;5:286–304. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v5.i3.286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hilty DM, Ferrer DC, Parish MB, Johnston B, Callahan EJ, Yellowlees PM, et al. The effectiveness of telemental health: A 2013 review. Telemed J E Health. 2013;19:444–54. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2013.0075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hilty D, Yellowlees PM, Parrish MB, Chan S. Telepsychiatry: Effective, evidence-based, and at a tipping point in health care delivery? Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2015;38:559–92. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2015.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fortney JC, Pyne JM, Turner EE, Farris KM, Normoyle TM, Avery MD, et al. Telepsychiatry integration of mental health services into rural primary care settings. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2015;27:525–39. doi: 10.3109/09540261.2015.1085838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Peters L, Andrews G. Procedural validity of the computerized version of the composite international diagnostic interview (CIDI-auto) in the anxiety disorders. Psychol Med. 1995;25:1269–80. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700033237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Trivedi MH, Kern JK, Grannemann BD, Altshuler KZ, Sunderajan P. A computerized clinical decision support system as a means of implementing depression guidelines. Psychiatr Serv. 2004;55:879–85. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.55.8.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kurian BT, Trivedi MH, Grannemann BD, Claassen CA, Daly EJ, Sunderajan P, et al. A computerized decision support system for depression in primary care. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;11:140–6. doi: 10.4088/PCC.08m00687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Trivedi MH, Claassen CA, Grannemann BD, Kashner TM, Carmody TJ, Daly E, et al. Assessing physicians’ use of treatment algorithms: Project IMPACTS study design and rationale. Contemp Clin Trials. 2007;28:192–212. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2006.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. [Last accessed on 2018 Apr 03]. Available from: http//www.psychiatristonweb.com .

- 37.Yellowlees P, Richard Chan S, Burke Parish M. The hybrid doctor-patient relationship in the age of technology – Telepsychiatry consultations and the use of virtual space. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2015;27:476–89. doi: 10.3109/09540261.2015.1082987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]